Design and Implementation of a Quick-Change End-Effector Control System for Lightweight Robotic Arms in Workpiece Assembly Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

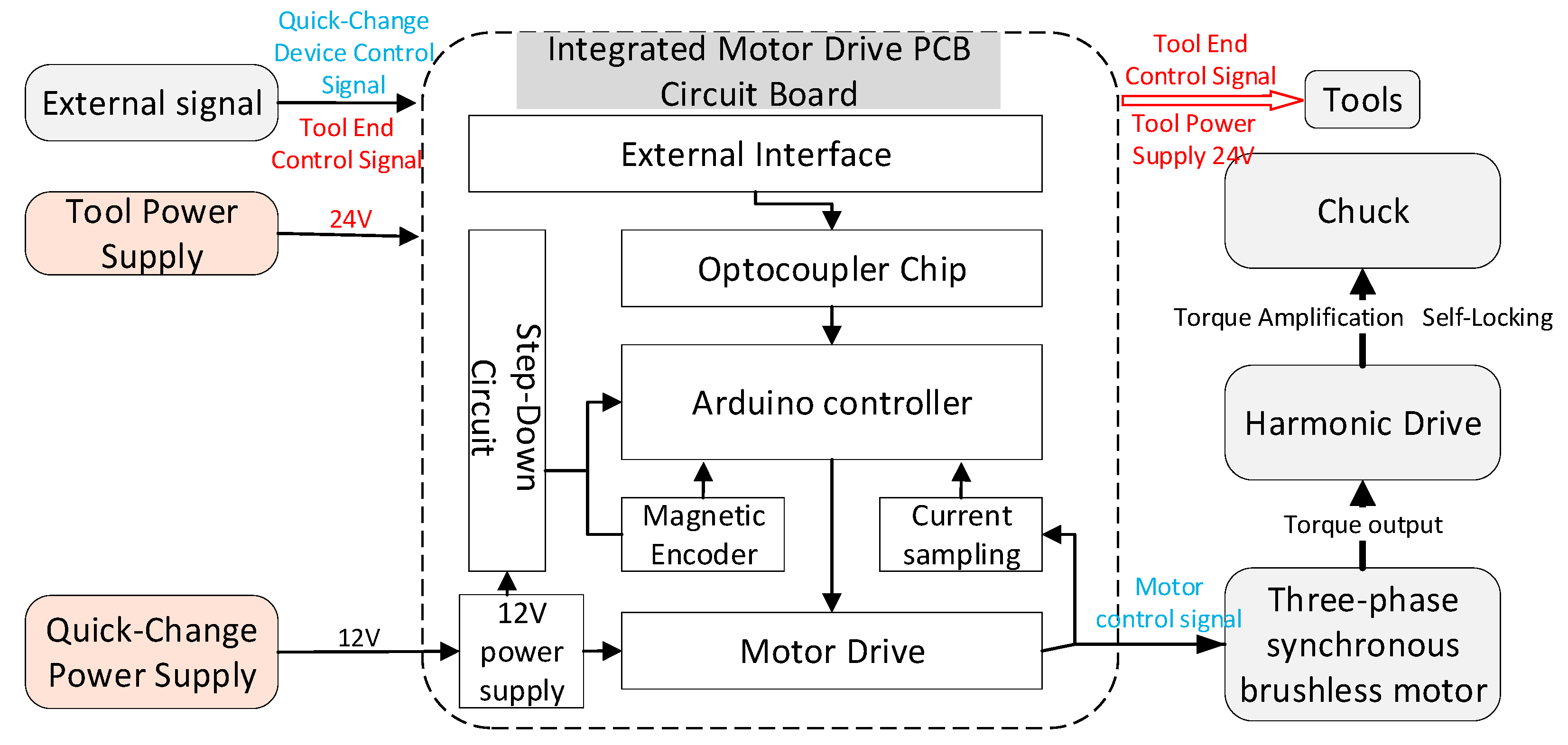

- A multi-tool quick-change control architecture for lightweight robotic arms has been proposed. An integrated control system comprising a quick-change end controller, tool-end adapter module, and host computer software has been established, enabling the robotic arm to automatically switch between various operational tools for task execution.

- (2)

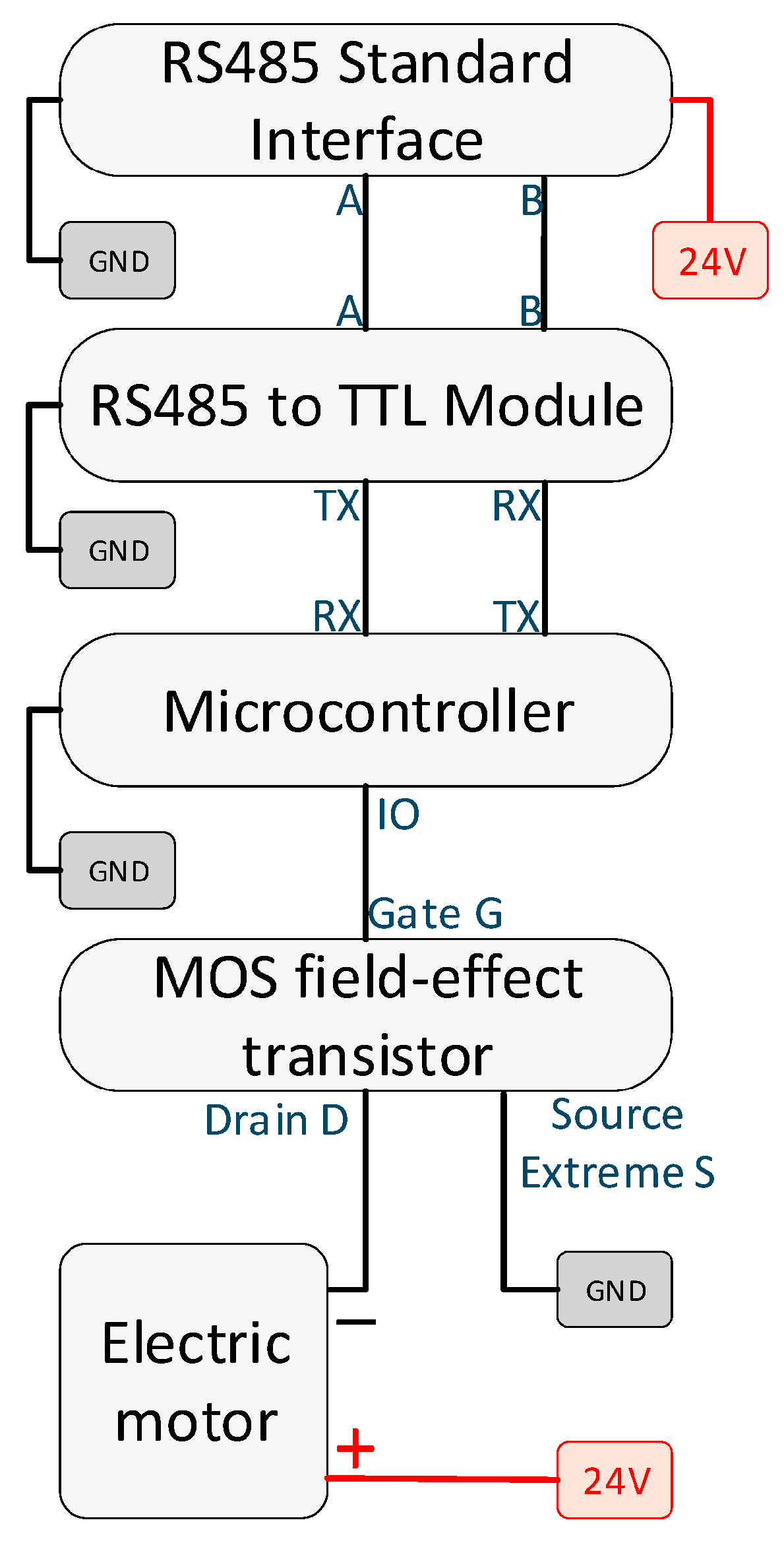

- To address inconsistent control interfaces for heterogeneous tools, a universal peripheral adapter circuit for motor-driven tools is designed. This circuit converts motor-driven tool signals into a standardized RS485 (Recommended Standard 485) communication protocol, enabling centralized control of multiple end-effectors via a single bus. Additionally, it identifies each tool’s unique ID to achieve corresponding control for tools of varying power ratings.

2. System Architecture Design

Quick-Change Hardware Platform Overview

- (1)

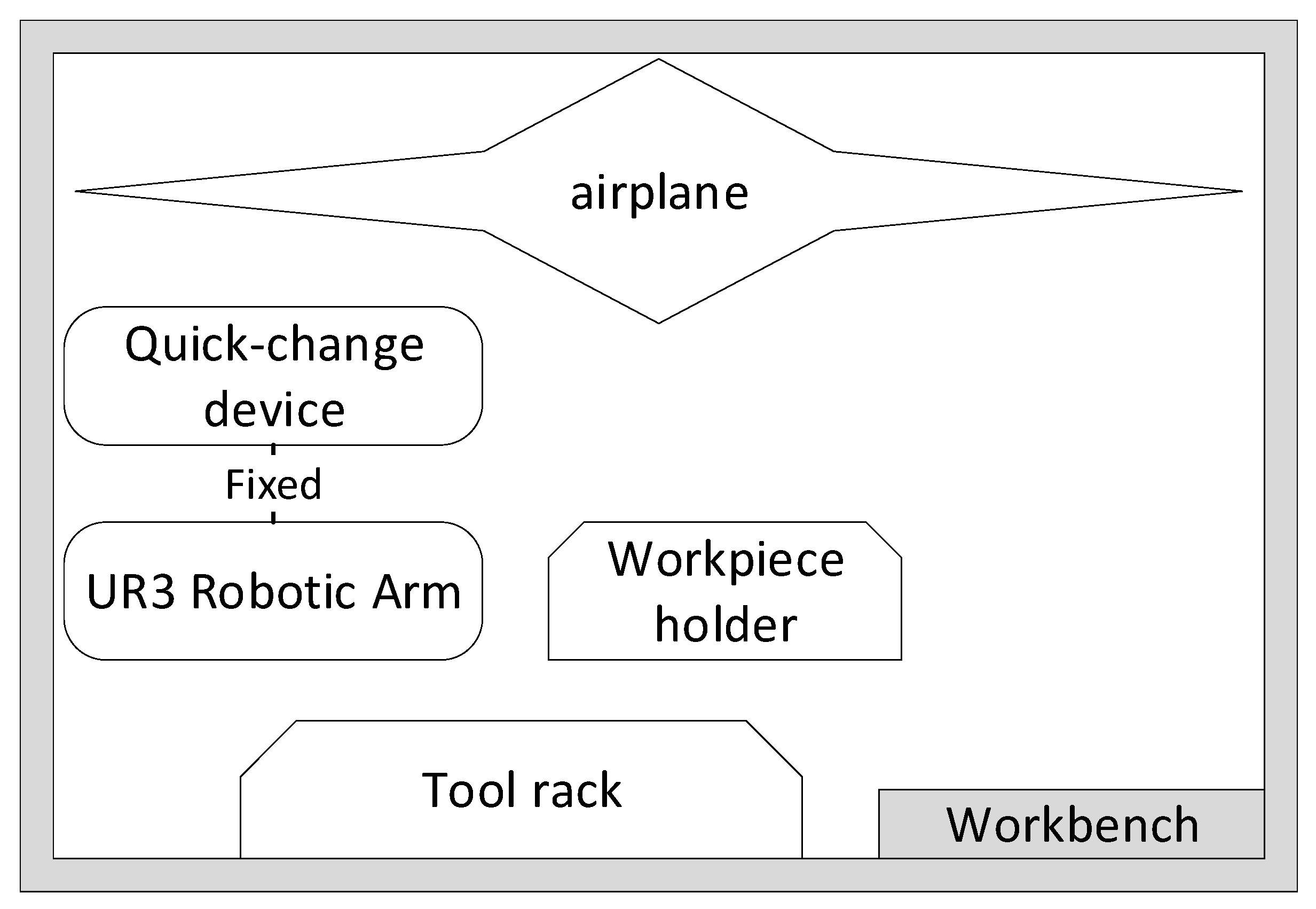

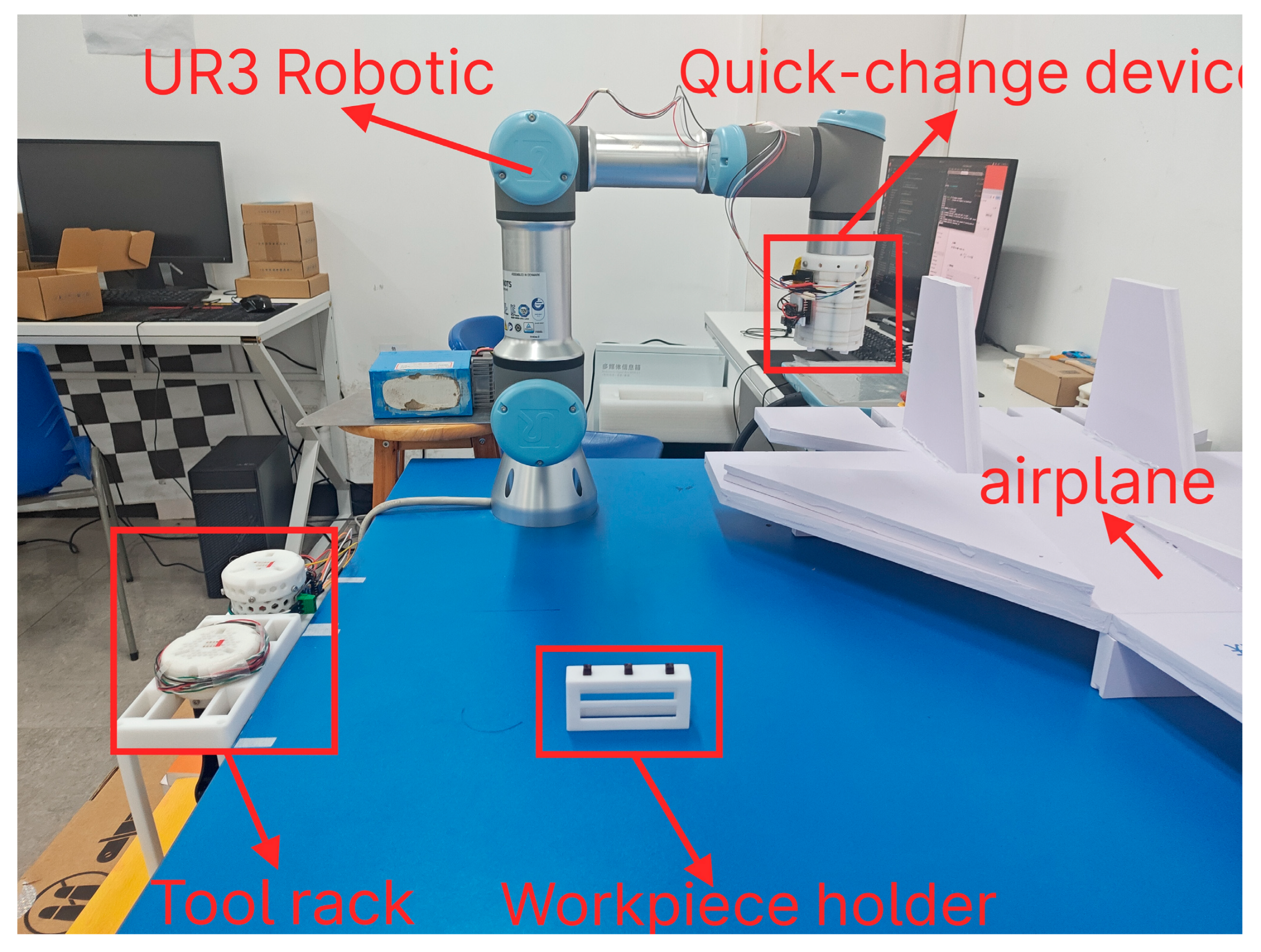

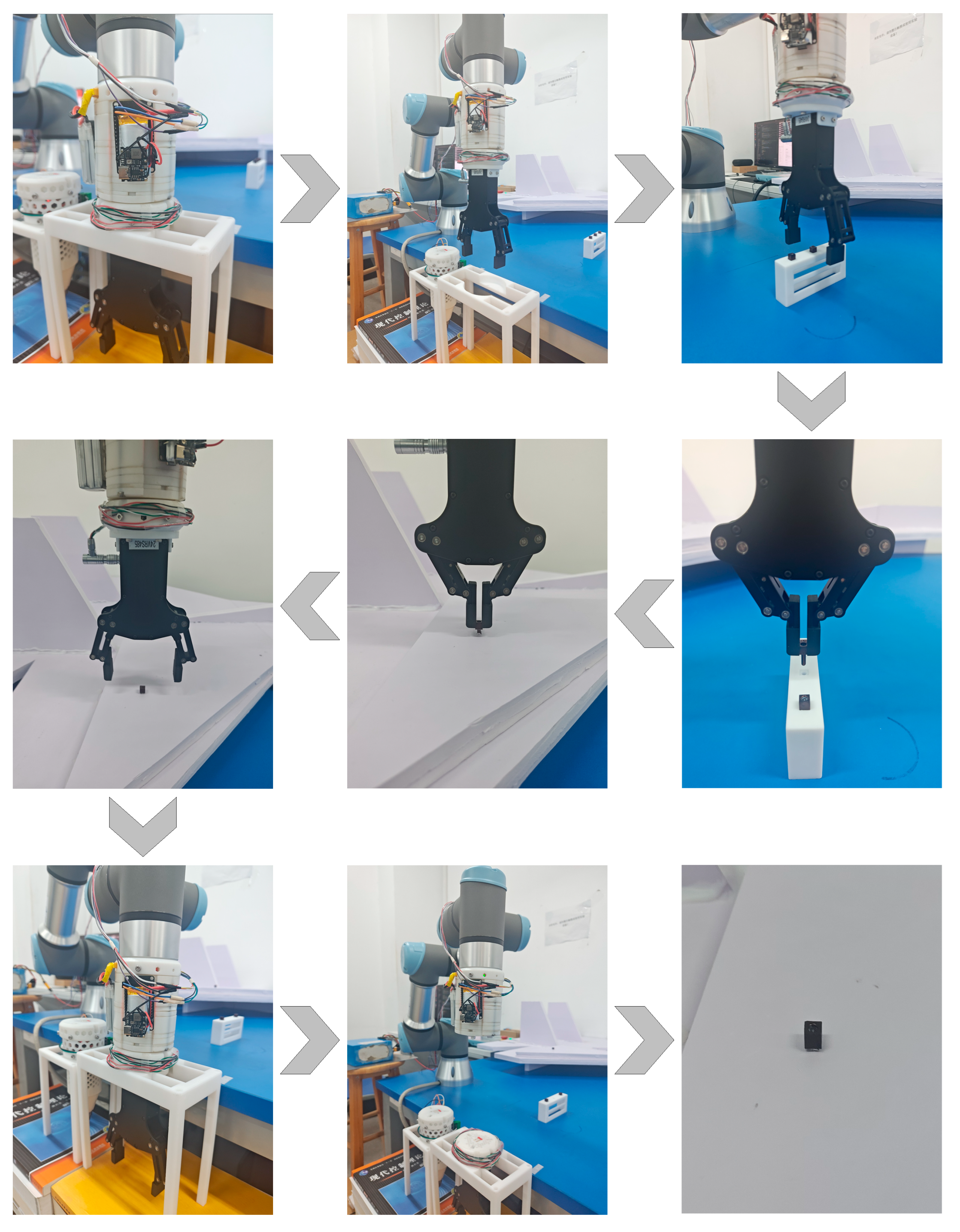

- Platform Positioning: The experimental workstation depicted in Figure 1 is designed for aircraft model assembly, aiming to validate multi-task (drilling, assembly) processes and spatial relationships. It does not represent an industrial production line for actual commercial aircraft fuselages.

- (2)

- Model Function: The integrated fuselage/wing model depicted is a fixed assembly primarily used to visualize spatial relationships in typical assembly tasks for comprehension purposes. It does not imply actual wing-to-fuselage final assembly at this workstation. The demonstrated “drilling-before-assembly” sequence holds universal applicability in industrial contexts.

- (3)

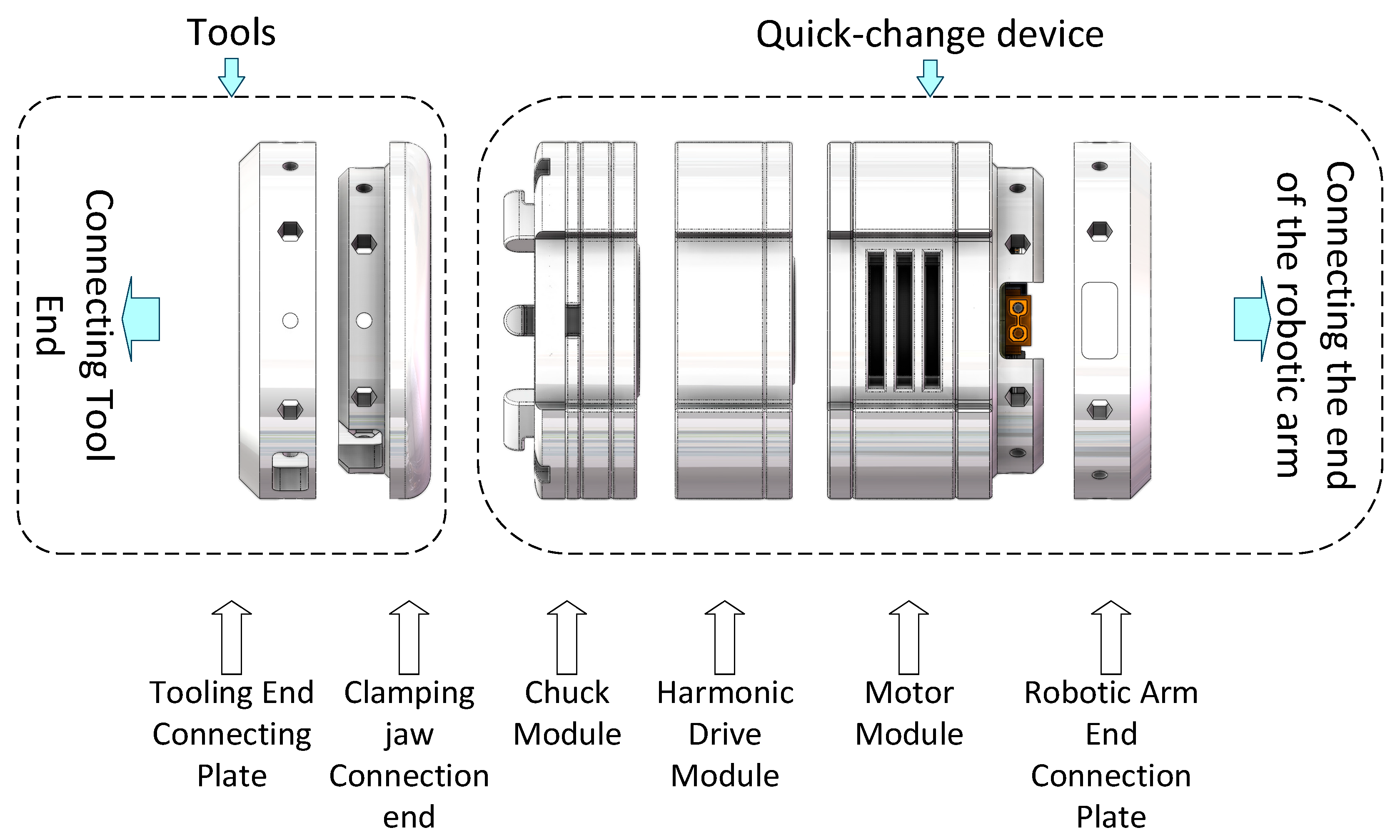

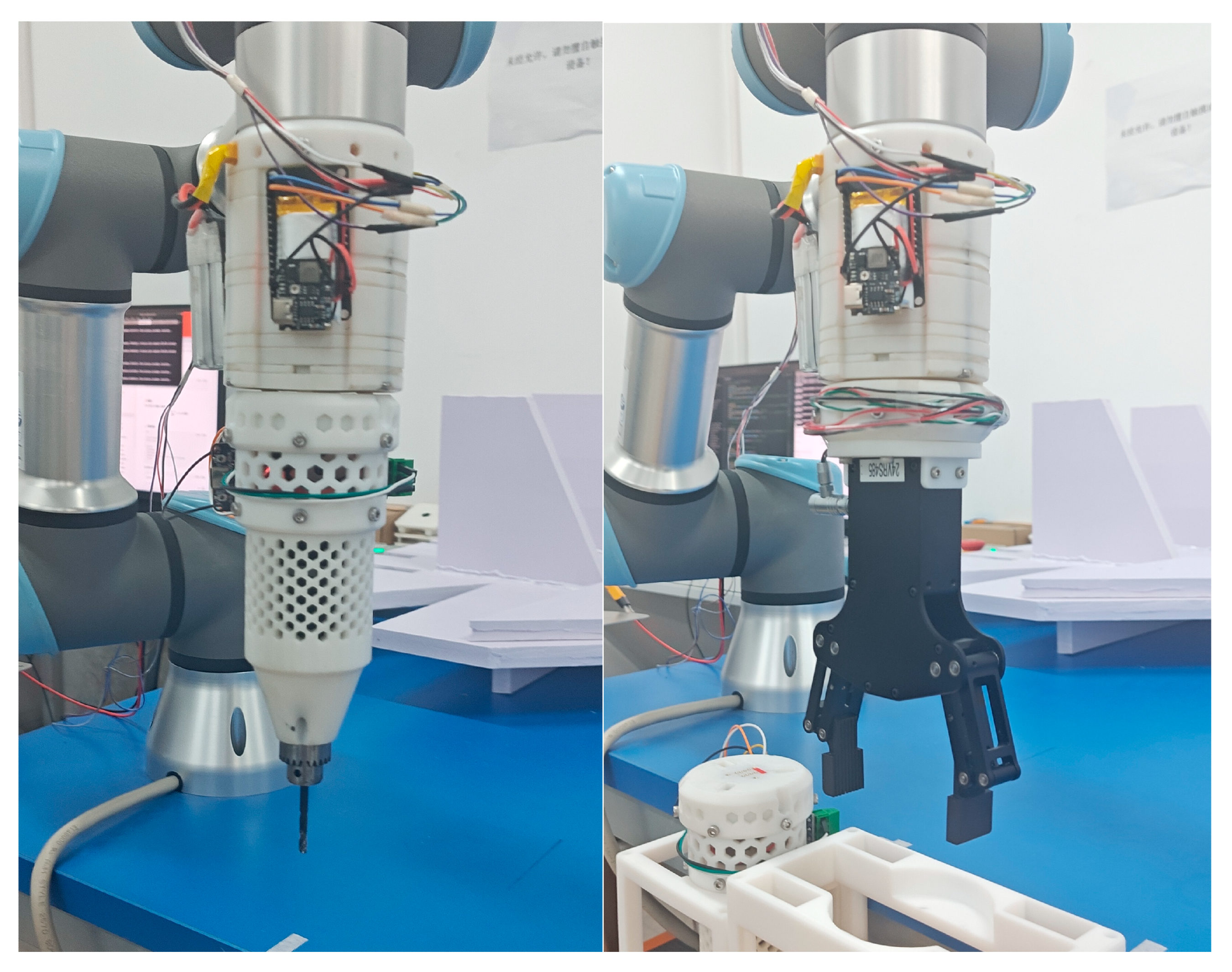

- Device Design: The self-developed quick-change device shown in Figure 2 employs photopolymerization 3D printing for rapid prototyping of most white structural components. This design prioritizes rapid construction of a lab-scale functional verification platform to enable efficient iteration and validation of the quick-change control system, interface protocols, and task workflows. It does not pursue ultimate structural strength or service life under industrial conditions.

- (4)

- Visual Value: This highly visual layout design aids readers in intuitively understanding the multi-tool collaborative assembly process and provides a clear reference for subsequent chapters analyzing the correlation between control logic and physical scenarios.

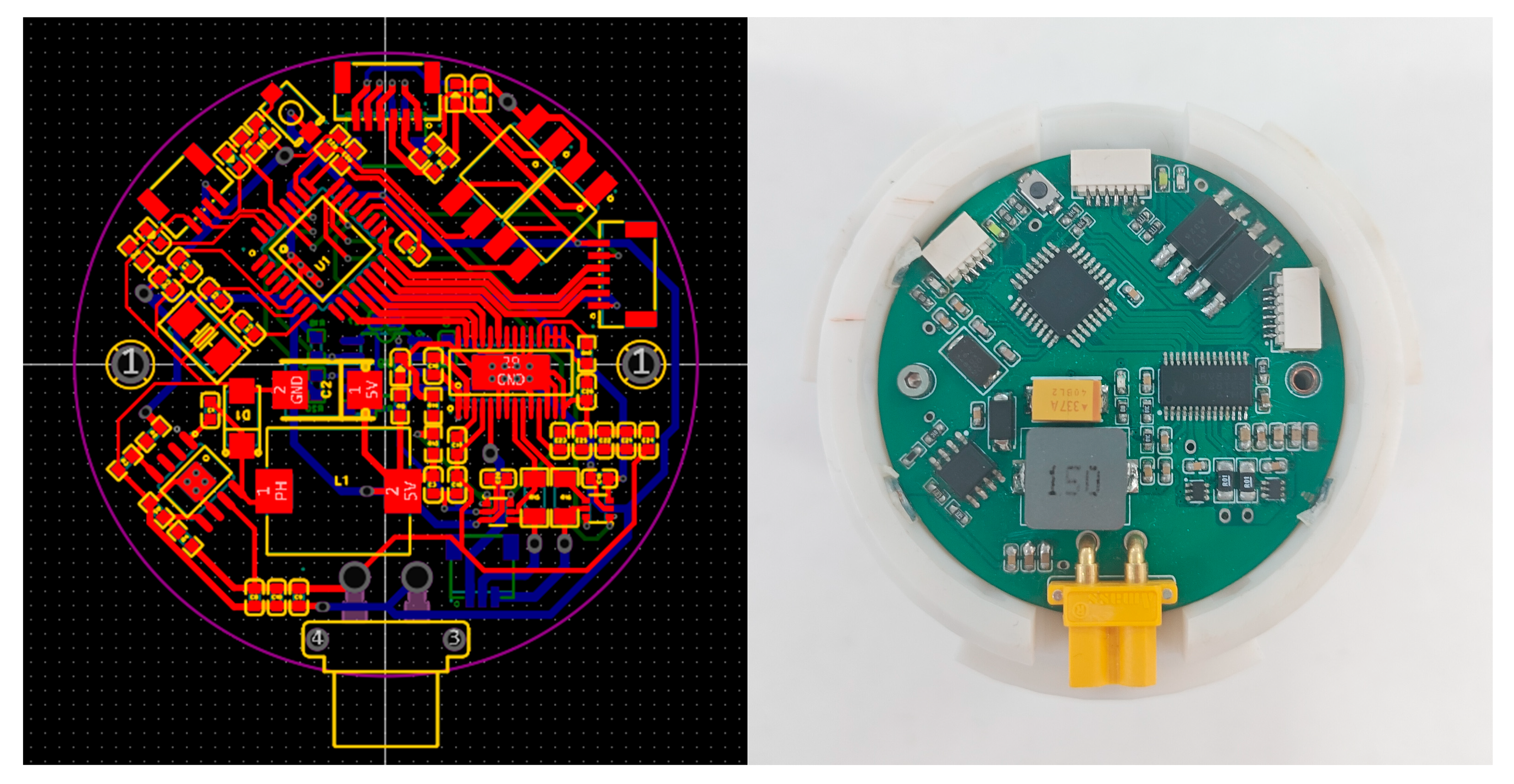

3. Circuit Design

3.1. Quick-Change Device Circuit Design

3.2. Tool-End Circuit Design

4. Program Design

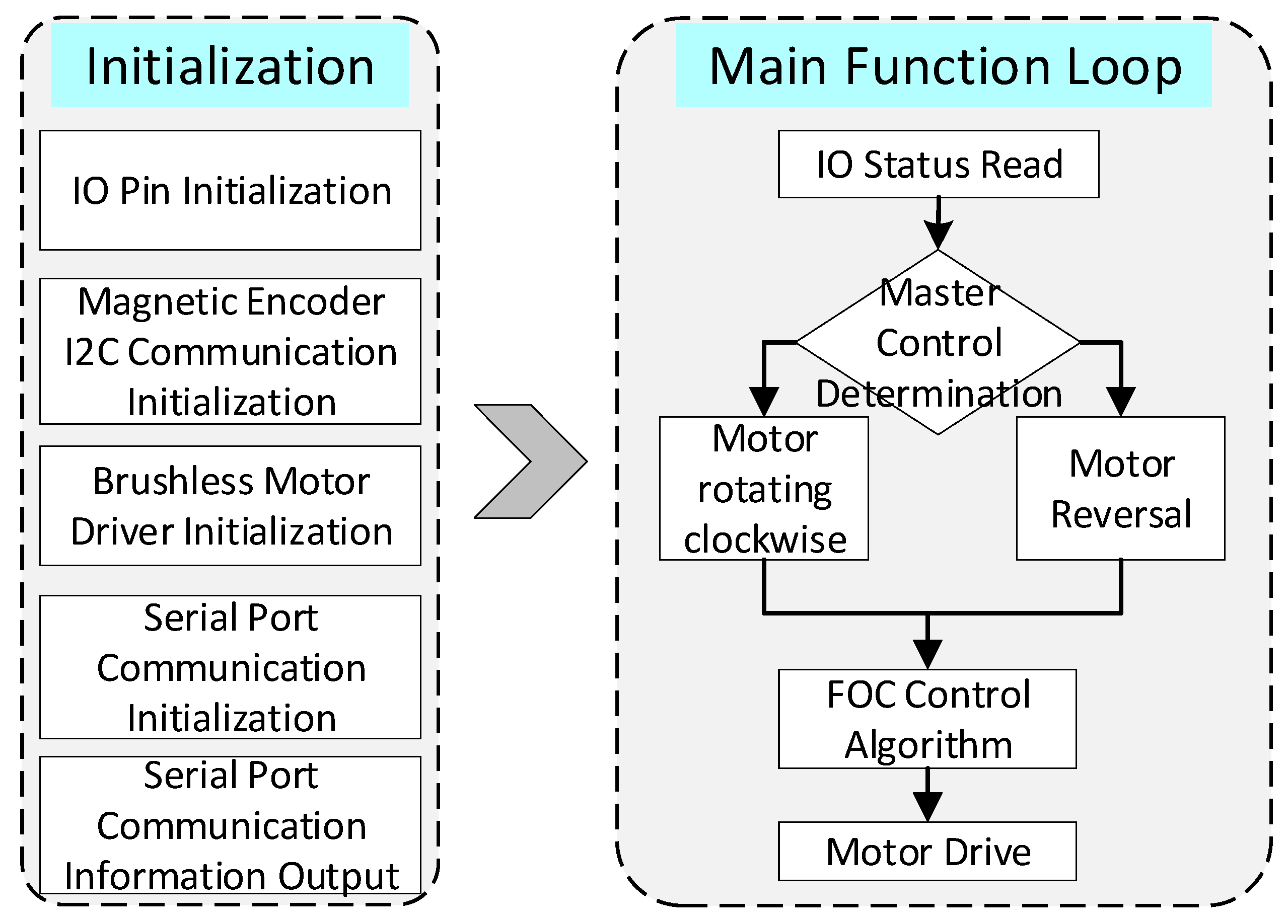

4.1. Quick-Change Device Program Design

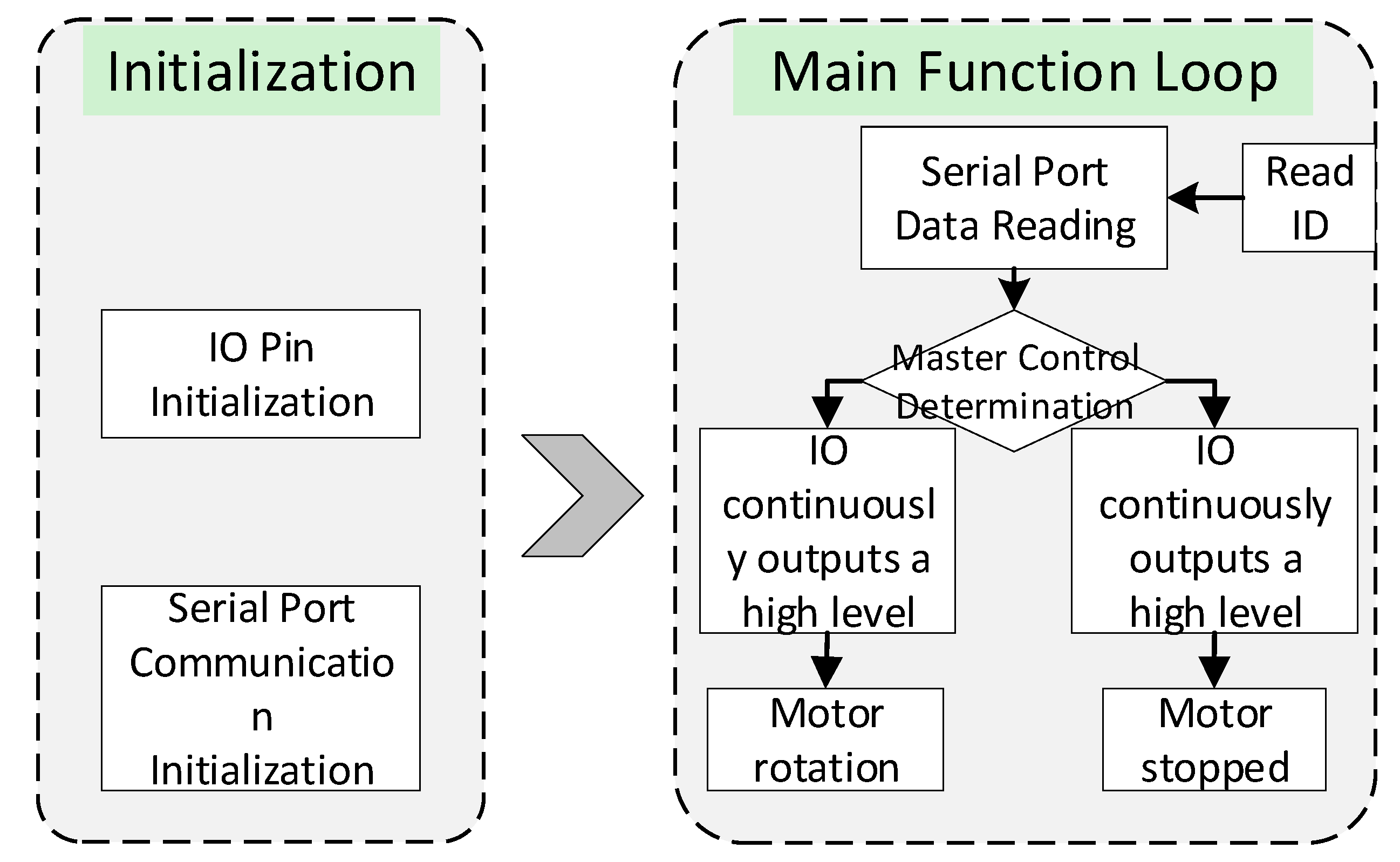

4.2. Tool-End Program Design

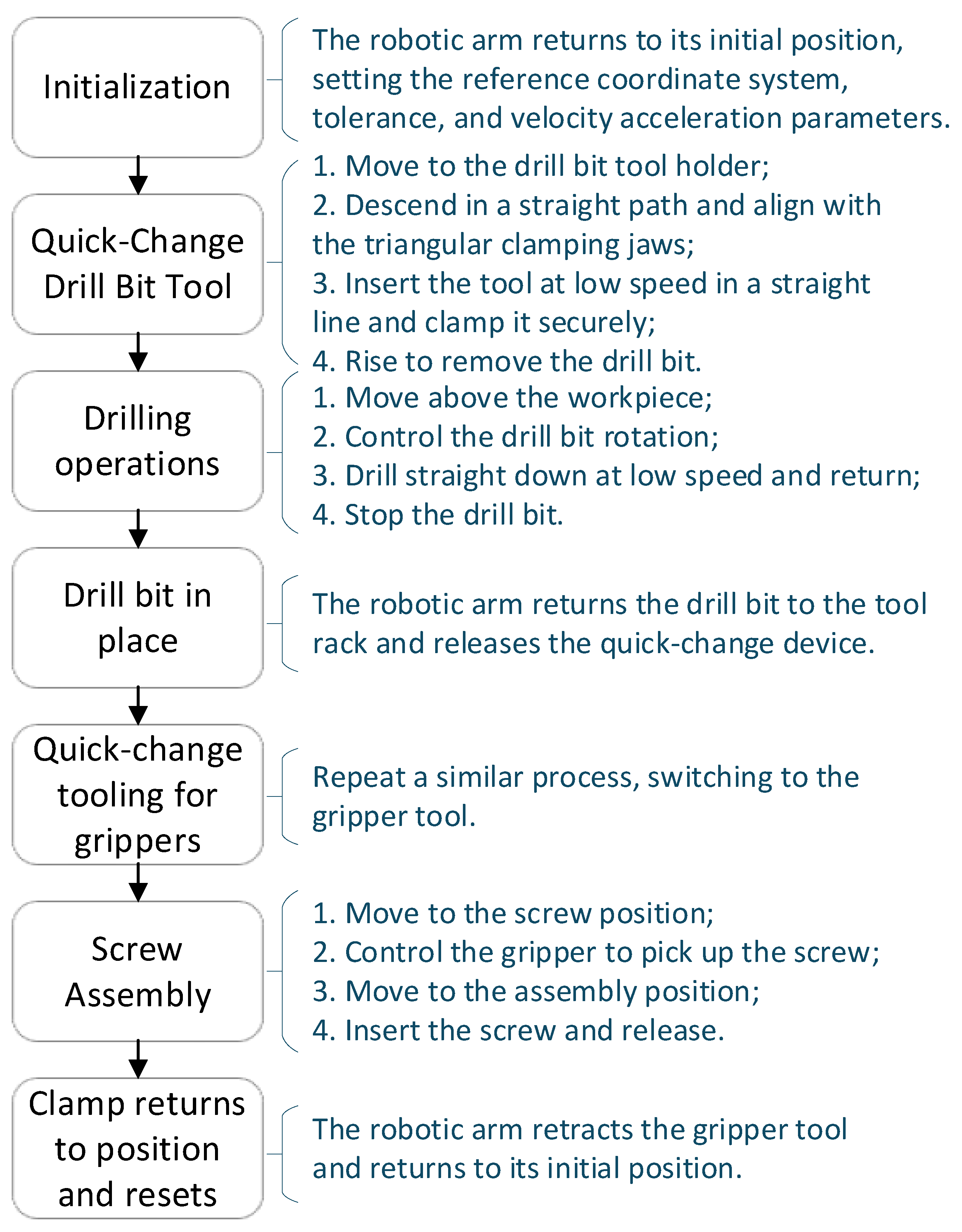

4.3. Assembly Process Program Design

5. Experimental Validation and Results

- (1)

- Verifying the feasibility of the motor drive adaptation circuit converting drive signals into the RS485 communication protocol using a drill bit tool as an example;

- (2)

- Validating the electrical and mechanical connection process between the quick-change device and various end tools;

- (3)

- Performing an integrated assembly experiment involving drilling and workpiece insertion to evaluate the system’s overall performance and stability in a simulated aircraft assembly environment.

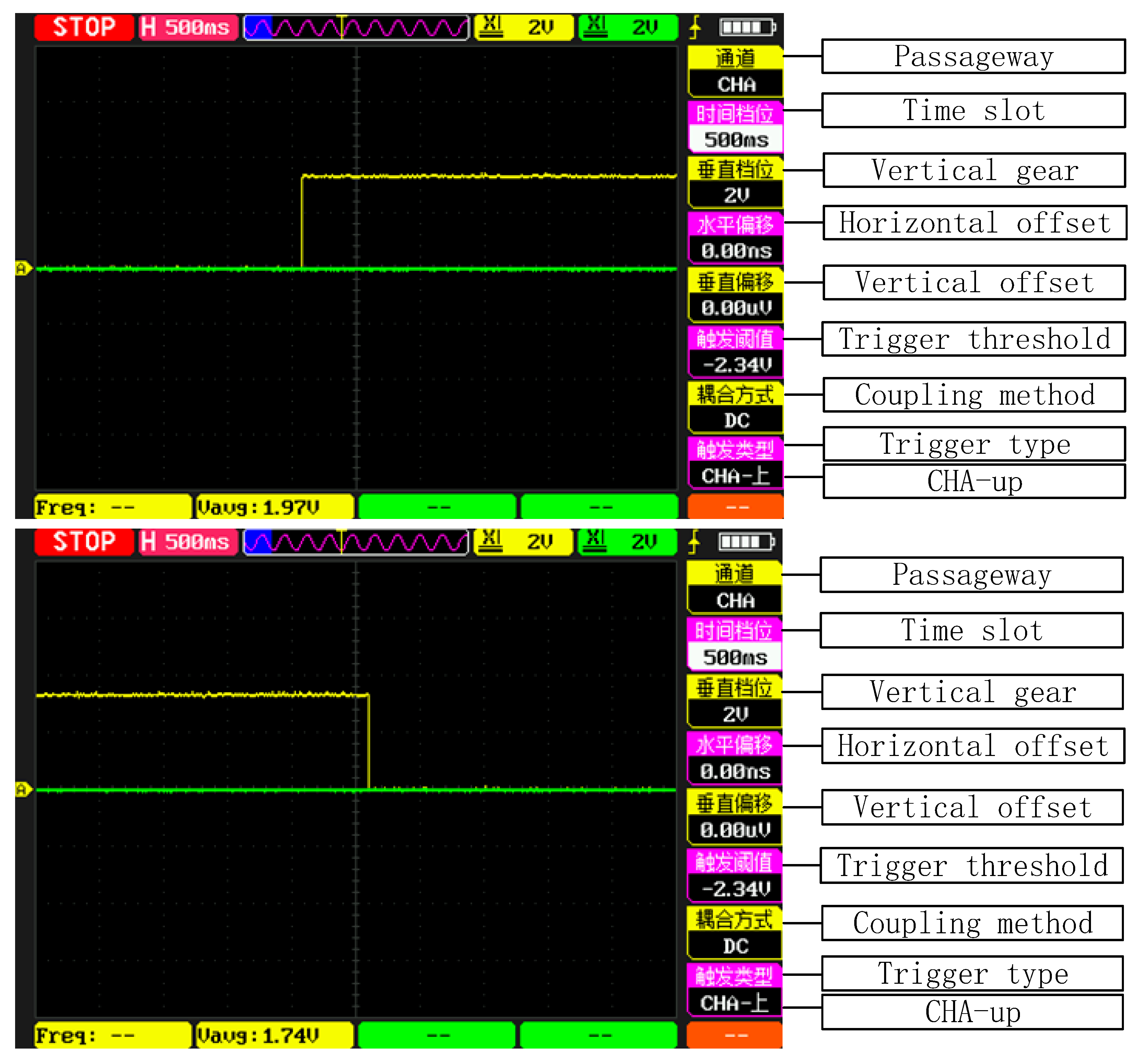

5.1. Experiment 1

5.2. Experiment 2

- (1)

- The complete quick-change device assembly, including the motor module, harmonic reducer module, chuck module, etc., is fully assembled and operational.

- (2)

- The motor drive-control integrated board is powered by a 12 V DC supply with ripple voltage below 100 mV.

- (3)

- Control signals are input at 3.3 V logic level to trigger the drive-control board to execute commands.

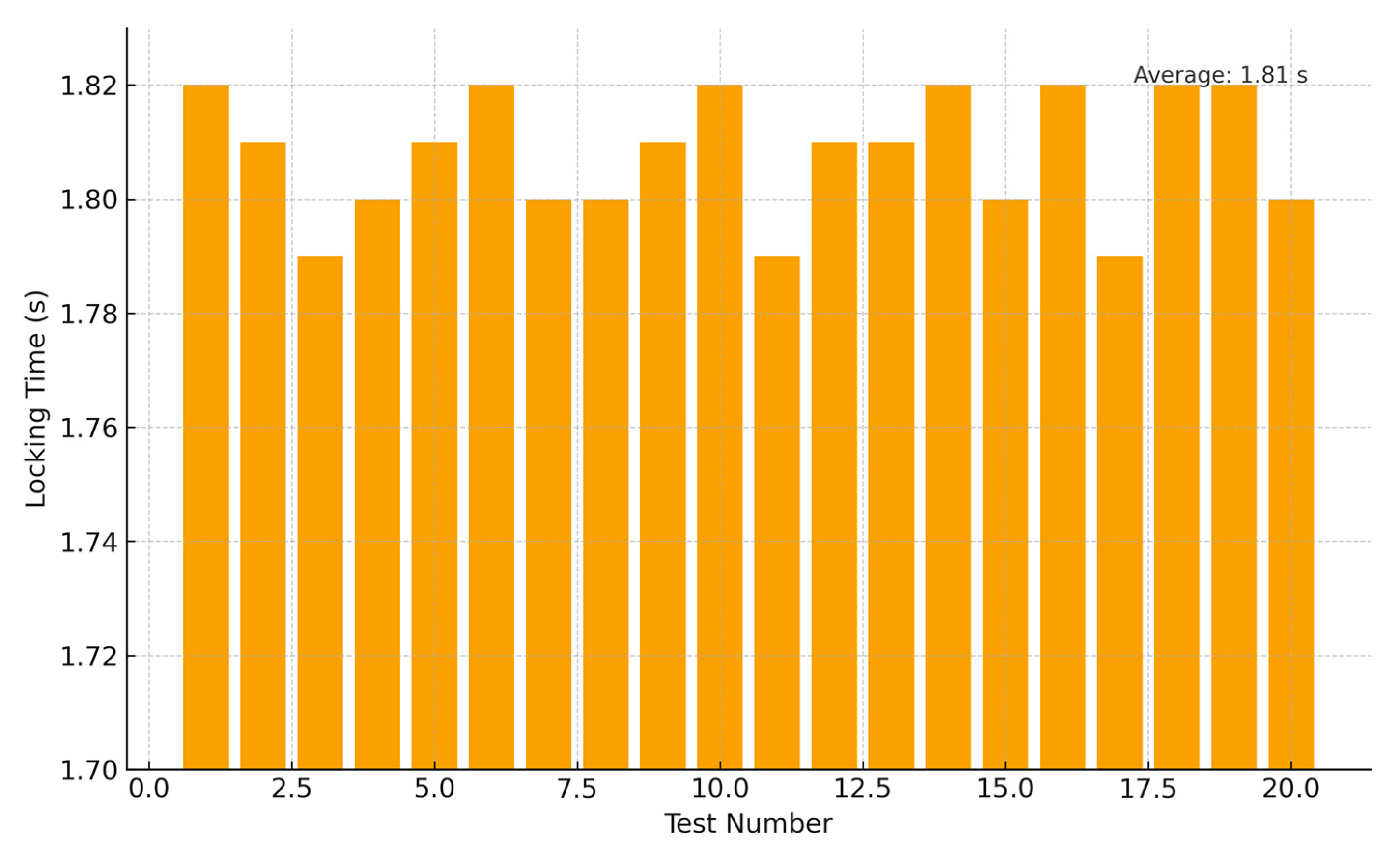

- (1)

- Locking Time Test Method

- (2)

- Communication Success Rate Test Method

5.3. Experiment 3

- (1)

- Tool ID recognition error or timeout;

- (2)

- Quick-change locking/unlocking process not completed as expected (e.g., control program aborts due to detected status anomalies);

- (3)

- Tool end fails to complete action within the specified time or returns an error flag;

- (4)

- Host computer detects communication failure or process logic anomaly, triggering emergency stop/reset.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Work

- (1)

- Supplement mechanical structure testing, including clamping force, repeatability accuracy, and durability assessment;

- (2)

- Introduce independent limit switches or redundant sensors to achieve more reliable clamping status detection;

- (3)

- Adopt industrial-grade motor drive modules and anti-interference circuits to enhance control system stability in complex environments;

- (4)

- Extend interface protocols to support a broader range of self-developed tools and further develop a task-level multi-tool collaboration framework.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UR3 | Universal Robots Model 3 |

| RS485 | Recommended Standard 485 |

References

- Zhao, J.Q.; Xu, Z.; Bian, Y.S. Development of Quick Working Condition Change Test Equipment for Joint Stiffness Using Pulley Block. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2022, 1, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Tang, L.N.; Han, F. End-Effector Design of Multi-Function Space Robot for Space on-Orbit Servicing. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 62, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q. Research Progress on Multi-Function of Robot End Tool Set. Mod. Manuf. Technol. Equip. 2023, 1, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, K. Practical Research on Industrial Robot Automation Production Technology. South. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvin, B.F. Robotic Tool Changer a Perfect Fit for Cobots: ATI Industrial Automation Booth B23036. Met. Form. 2021, 8, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Research on the Quick-Change Method and Device for Vulnerable Parts in Nuclear Industry Automation Equipment. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Science and Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Guo, S.; Zhang, J.L.; Ding, H.B.; Zhang, B.; Cao, A.; Sun, X.H.; Zhang, G.X.; Tian, S.H.; Chen, Y.X.; et al. Optimized Design and Deep Vision-Based Operation Control of a Multi-Functional Robotic Gripper for an Automatic Loading System. Actuators 2025, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.Y.; Kang, L.W.; Chiang, H.H.; Li, H.C. Integration of Robotic Vision and Automatic Tool Changer Based on Sequential Motion Primitive for Performing Assembly Tasks. IFAC PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 5320–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OnRobot. Quick Changer—Product Manual and Specifications; OnRobot A/S: Odense, Denmark, 2025. Available online: https://onrobot.com/en/products/quick-changer (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Gimatic Automation. EQC-E Electric Quick Changer—Catalogue; Gimatic S.r.l.: Brescia, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://www.gimatic.com/en/products/quick-changers/eqc-e/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Zimmer Group. HEK-E Electric Tool Changer—Product Sheet; Zimmer Group GmbH: Rheinau, Germany, 2025. Available online: https://www.zimmer-group.com (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Radcoll Robotics. RS-E Lightweight Electric Tool Changer—Product Overview; Radcoll Robotics: Shenzhen, China, 2025; Available online: https://crgeoat.com/products/automatic-tool-changer (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Robotiq. Hand-E Instruction Manual for e-Series Robots (RS-485 Communication); Robotiq Inc.: Québec, QC, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://assets.robotiq.com/website-assets/support_documents/document/Hand-E_Instruction_Manual_e-Series_PDF_20190122.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Lu, T.W.; Xia, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.S.; Zhu, J.X. Machining Micro-Error Compensation Methods for External Turning Tool Wear of CNC Machines. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Teeple, C.; Wood, R.J.; Cappelleri, D.J. Modular End-Effector System for Autonomous Robotic Maintenance & Repair. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 4510–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.S.; Cui, X.W.; Hu, Z.J.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, T. Development of an End-Toothed Disc-Based Quick-Change Fixture for Ultra-Precision Diamond Cutting. Machines 2021, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. Design of Robot End-Effector for Collaborative Robot Works. Ph.D. Thesis, École centrale de Nantes, Nantes, France, 2021. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04700359v2 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Gao, W.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Deng, J.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, Y.C. Research Status and Trends in Universal Robotic Picking End-Effectors for Various Fruits. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, M.; Blumberg, A.; Regulin, D.; Hauser, T.; Saenz, J.; Lee, D. Design of a Collaborative Modular End Effector Considering Human Values and Safety Requirements for Industrial Use Cases. In Human-Friendly Robotics 2021; Palli, G., Melchiorri, C., Meattini, R., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Advanced Robotics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 23, pp. 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.E.; Padayachee, J.; Bright, G. Development and Analysis of Reconfigurable Robotic End-Effector for Machining and Part Handling. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2021, 32, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Sun, Z.J. Design and Control of the Manipulator of Magnetic Surgical Forceps with Cable Transmission. Micromachines 2025, 16, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Robot Type | UR3 |

|---|---|

| Weight | 11 kg/24.3 lb |

| Maximum Payload | 3 kg/6.6 lb |

| Range of motion | The tool flange can rotate freely without restriction; all other joints rotate ±360° |

| degree of freedom | 6 rotating joint |

| I/O Power Supply | 24 V 2 A in Control Box |

| Communications | TCP/IP 1000 Mbit: IEEE 802.3u, 100BASE-T Ethernet interface, Modbus TCP and Ethernet/IP adapters, Profinet |

| Power supply | 100–240 VAC, 50–60 Hz |

| Company | INSPIRE-ROBOTS |

|---|---|

| Model | EG2–4C2 |

| Communication Interface | RS485 |

| Weight | 231 g |

| Clamping force | 0–20 N |

| Operating Voltage | DC24V ± 10% |

| Static current | 30 mA |

| Peak current | 0.7 A |

| Number of responses | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Response time/ms | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| Number of responses | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | average |

| Response time/ms | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.08 |

| Number of Locking Tests | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Locking time/s | 1.82 | 1.81 | 1.79 | 1.80 | 1.81 | 1.82 | 1.80 |

| Whether successful | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of Locking Tests | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Locking time/s | 1.80 | 1.81 | 1.82 | 1.79 | 1.81 | 1.81 | 1.82 |

| Whether successful | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Number of Locking Tests | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | average |

| Locking time/s | 1.80 | 1.82 | 1.79 | 1.82 | 1.82 | 1.80 | 1.81 |

| Whether successful | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 100% |

| Number of assemblies | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Success/Failure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of assemblies | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Success/Failure | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 |

| Number of assemblies | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 |

| Success/Failure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of assemblies | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | success rate | |

| Success/Failure | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 93.3% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luan, G.; Hu, L.; Wang, R. Design and Implementation of a Quick-Change End-Effector Control System for Lightweight Robotic Arms in Workpiece Assembly Applications. Actuators 2025, 14, 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120619

Luan G, Hu L, Wang R. Design and Implementation of a Quick-Change End-Effector Control System for Lightweight Robotic Arms in Workpiece Assembly Applications. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120619

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuan, Guangxin, Lingyan Hu, and Raofen Wang. 2025. "Design and Implementation of a Quick-Change End-Effector Control System for Lightweight Robotic Arms in Workpiece Assembly Applications" Actuators 14, no. 12: 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120619

APA StyleLuan, G., Hu, L., & Wang, R. (2025). Design and Implementation of a Quick-Change End-Effector Control System for Lightweight Robotic Arms in Workpiece Assembly Applications. Actuators, 14(12), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120619