Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamental Terminologies

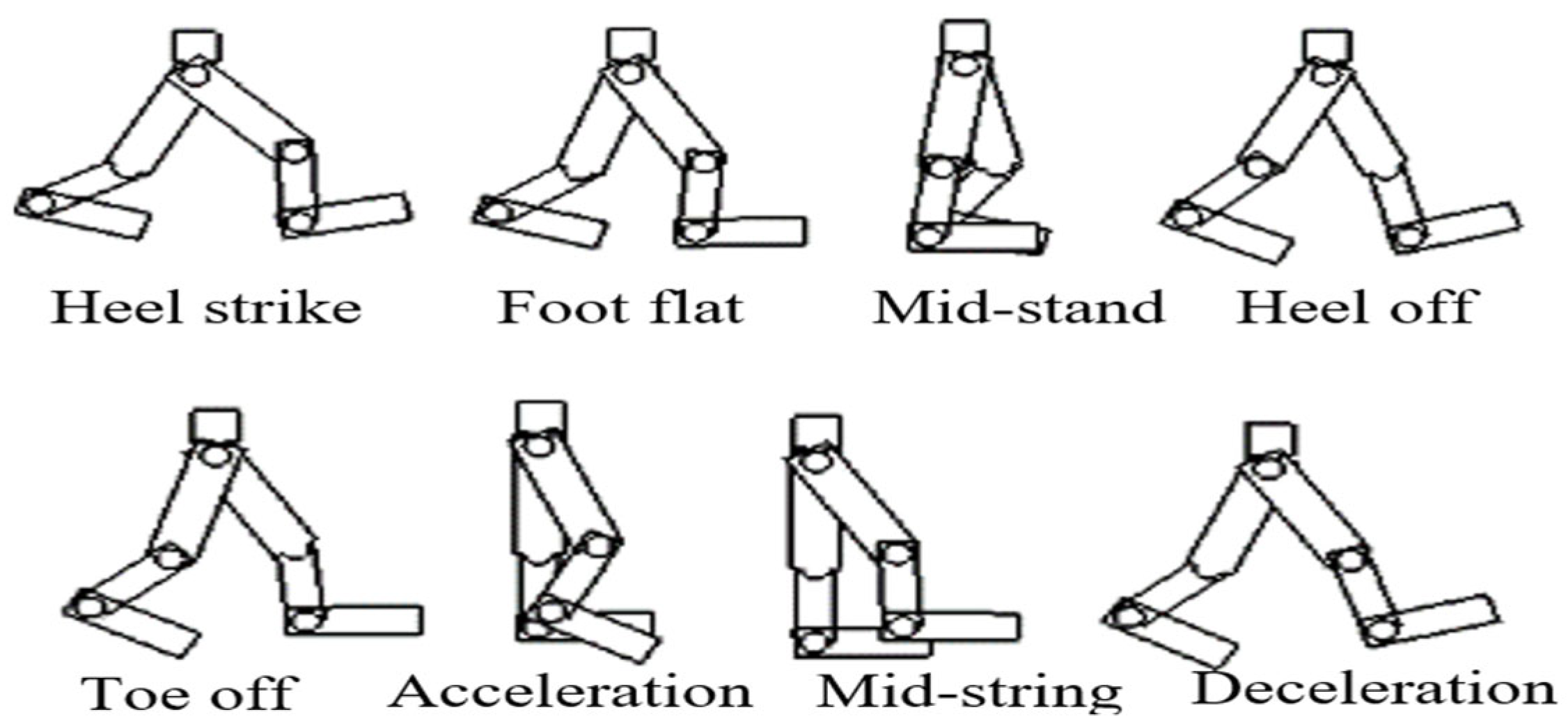

2.2. Simulation of a Gait Cycle

- a.

- Plantar flexion begins at initial contact as the anterior tibialis and posterior tibialis muscles contract eccentrically to slow the foot’s movement. This phase develops when the foot moves in a range of 0–55 degrees, preventing a sudden foot slap. As the body moves forward into mid-stance, the plantar flexor muscles contract eccentrically to provide front-to-back (anterior–posterior) stability. As the body continues forward, these muscles shift to concentric contraction to help accelerate the body. At this phase, the dorsiflexors continue to provide support through eccentric contraction.

- b.

- Dorsiflexion usually happens after the toe-off and during the swing phase which in a range of 0–25 degrees. At this point, the anterior tibialis and posterior tibialis muscles contract concentrically to lift the foot and prevent footdrop and drag toes. At the same time, hip and knee flexion increase foot clearance during the swing.

- c.

- Inversion and Eversion occur during walking when the foot moves approximately 20 degrees and 10 degrees, respectively. From initial contact to loading response, a few degrees of eversion allow the foot to fully contact the ground. The posterior tibialis contracts eccentrically to stabilize the foot during mid-stance and terminal stance. The peroneal muscles drive heel movement during eversion, with their distinct nerve supply causing the motion to start slowly and then speed up, which usually completes in about one second. Inversion, controlled mainly by the posterior tibialis, may happen more quickly, in about 0.2 s. As the foot prepares for terminal swing, it increases stability and begins acceleration for the next step.

2.3. Foot–Ankle Model

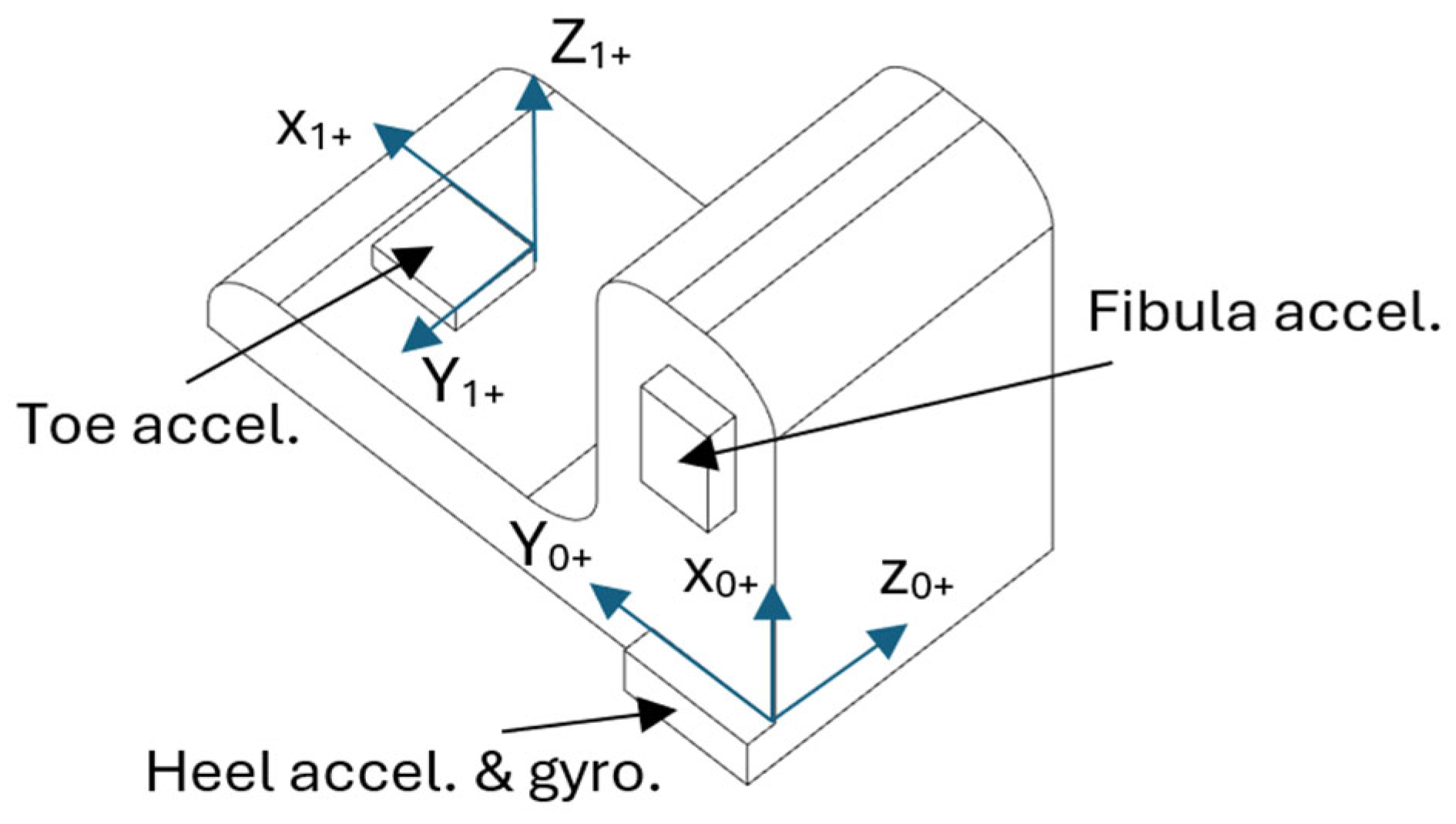

2.4. Monitoring Sole Deformation

3. Experimental Works

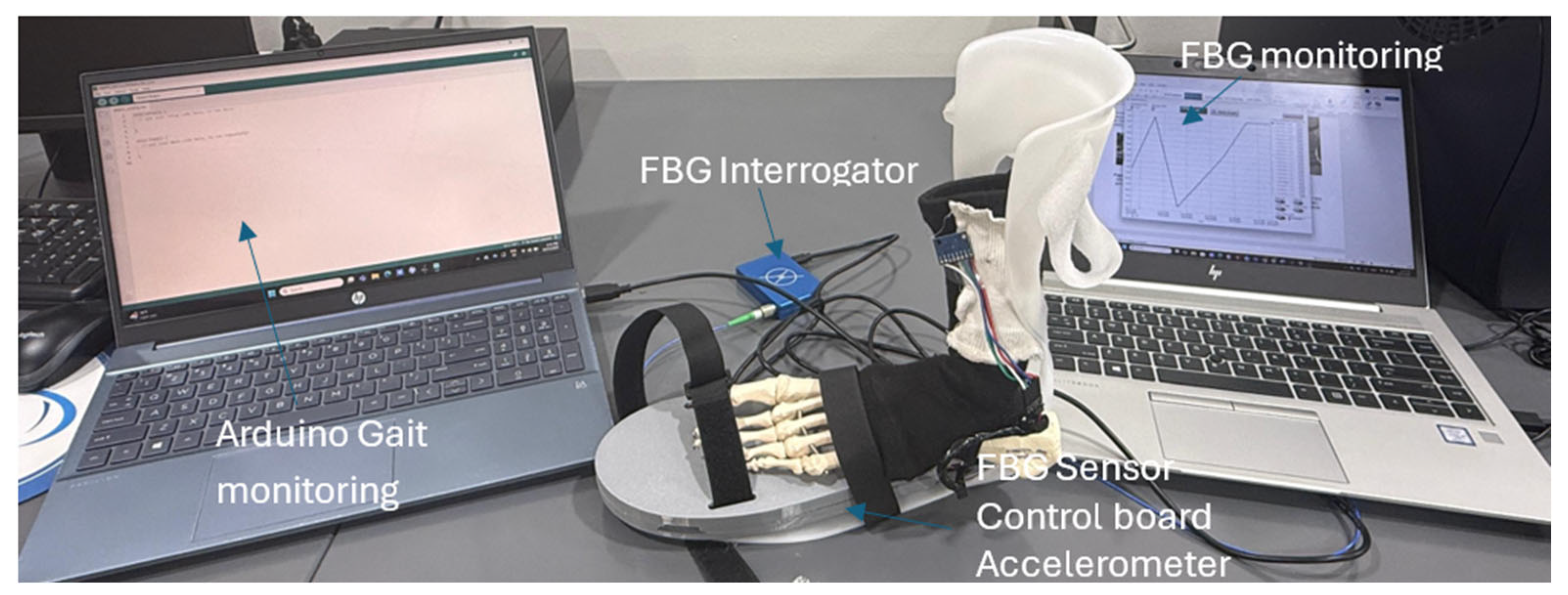

3.1. Validation Experimental Tests

3.2. Experimental Testing

Simulation

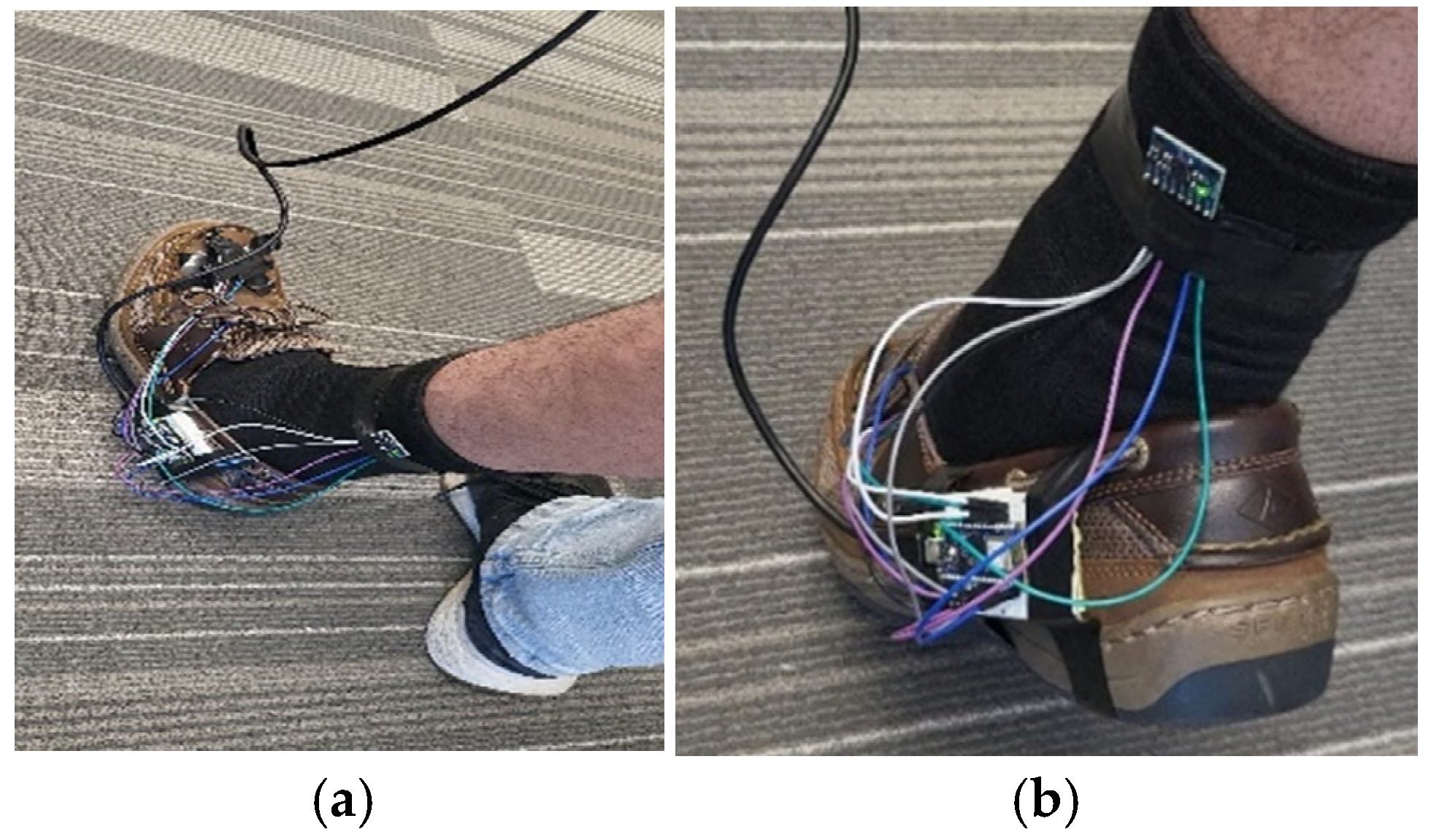

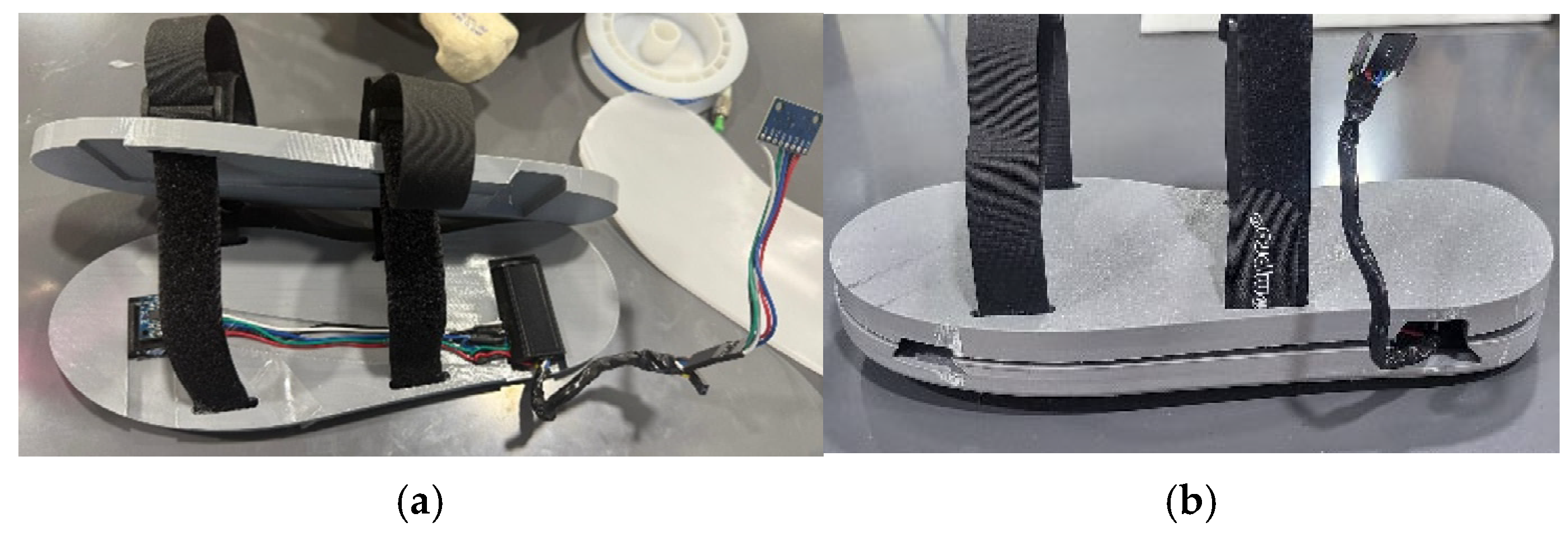

3.3. Prototype of the Smart Foot–Ankle Brace

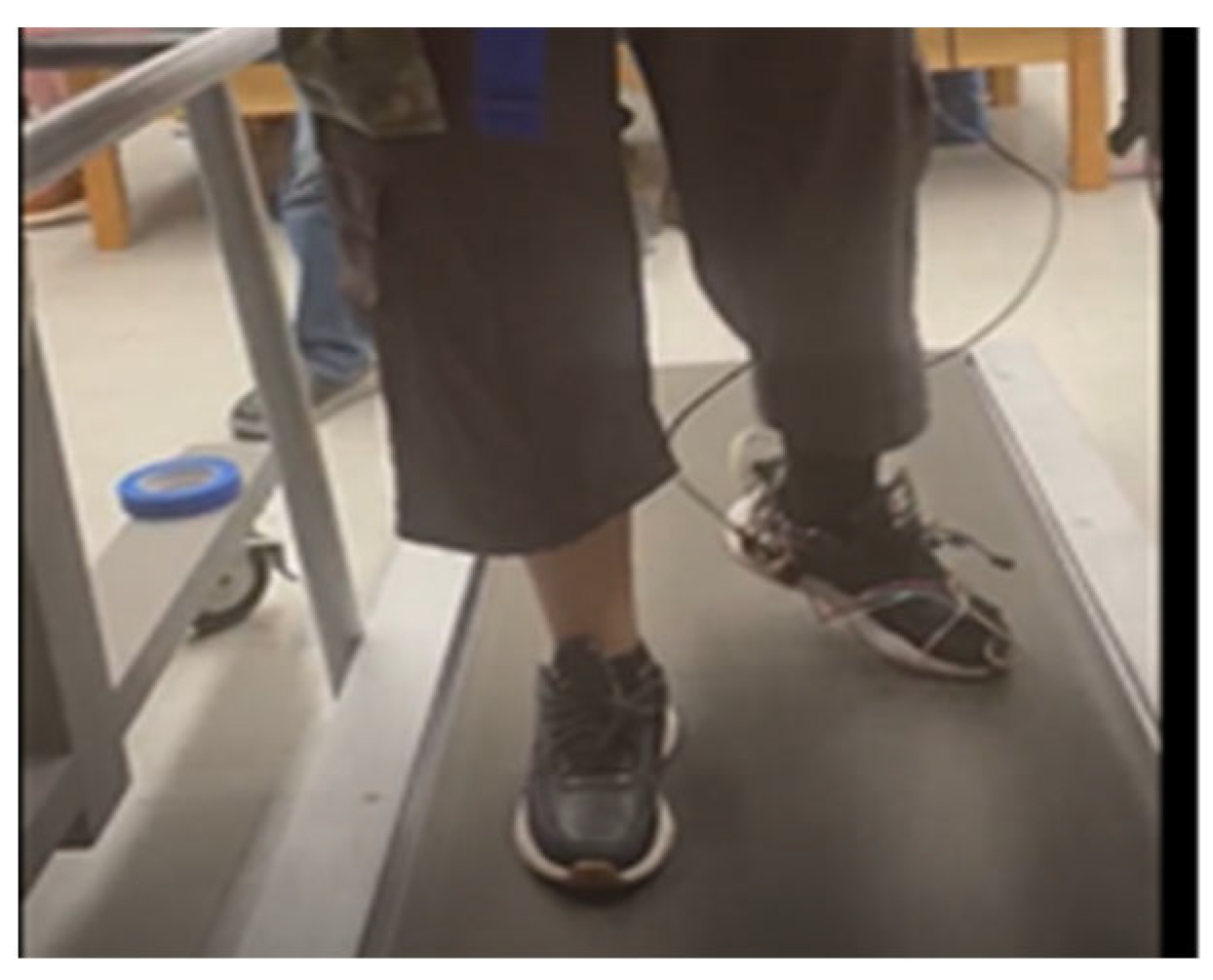

3.4. Practical Demonstration

4. Results and Discussions

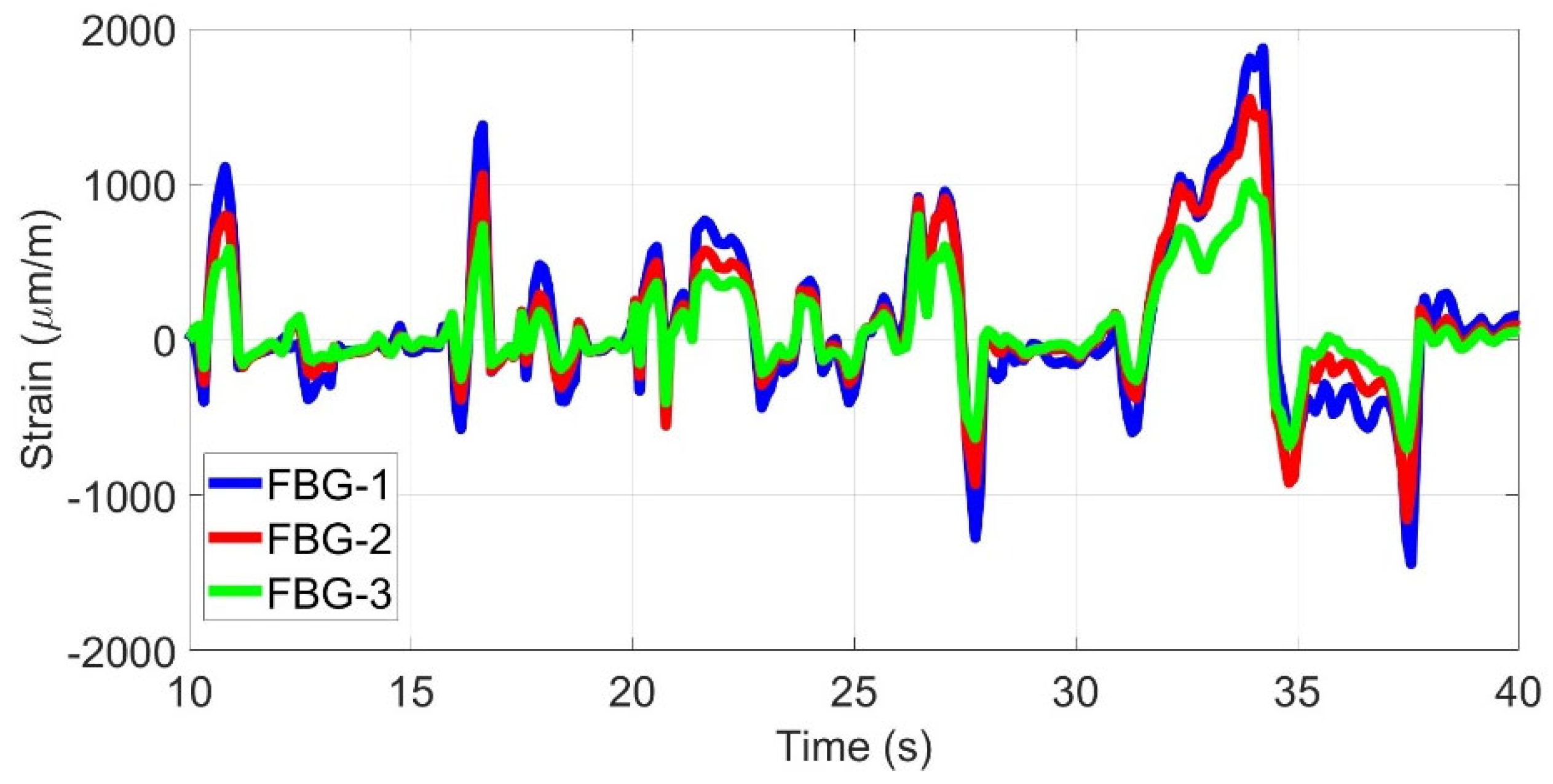

4.1. Foot Deformation Detection

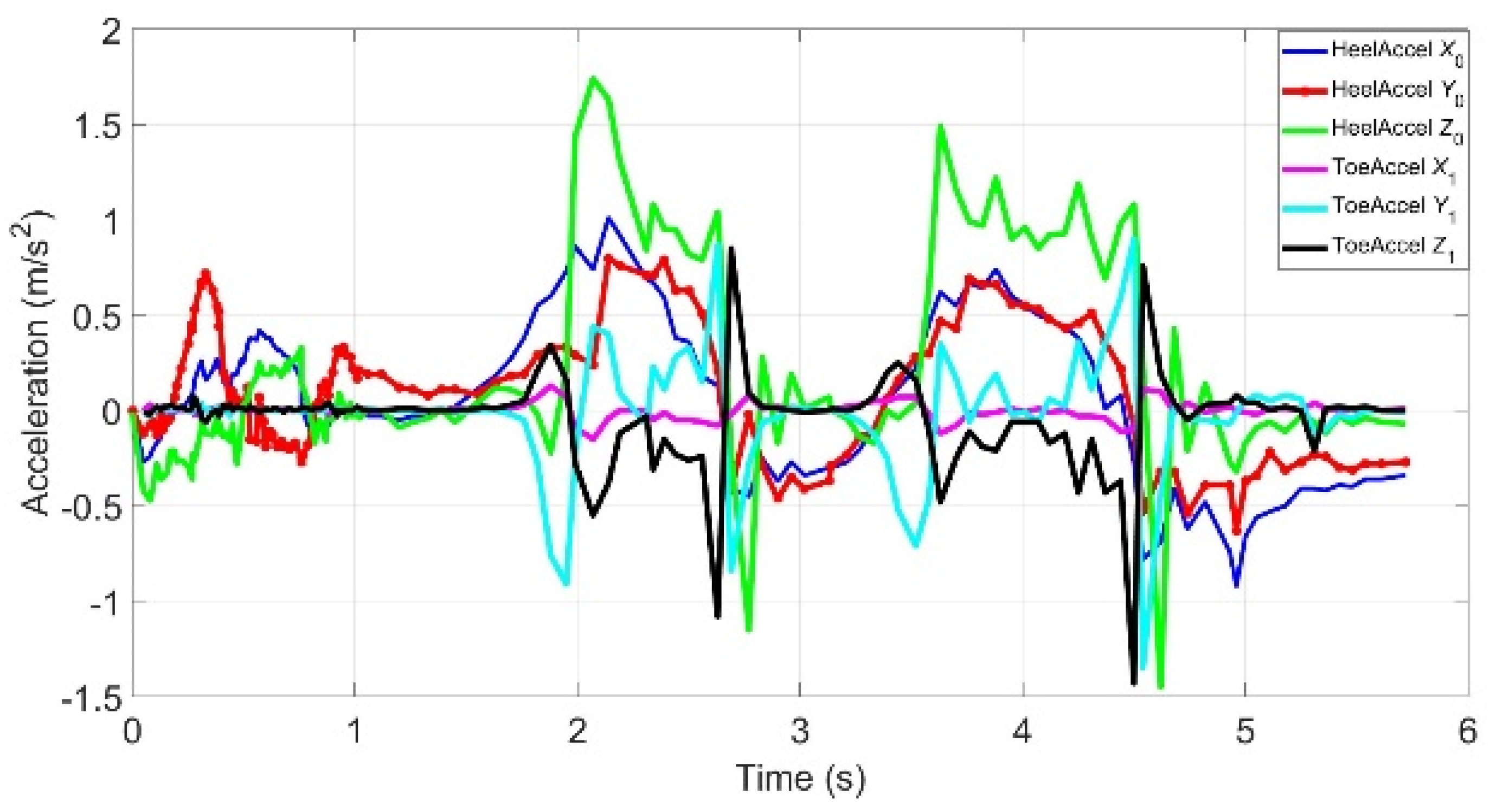

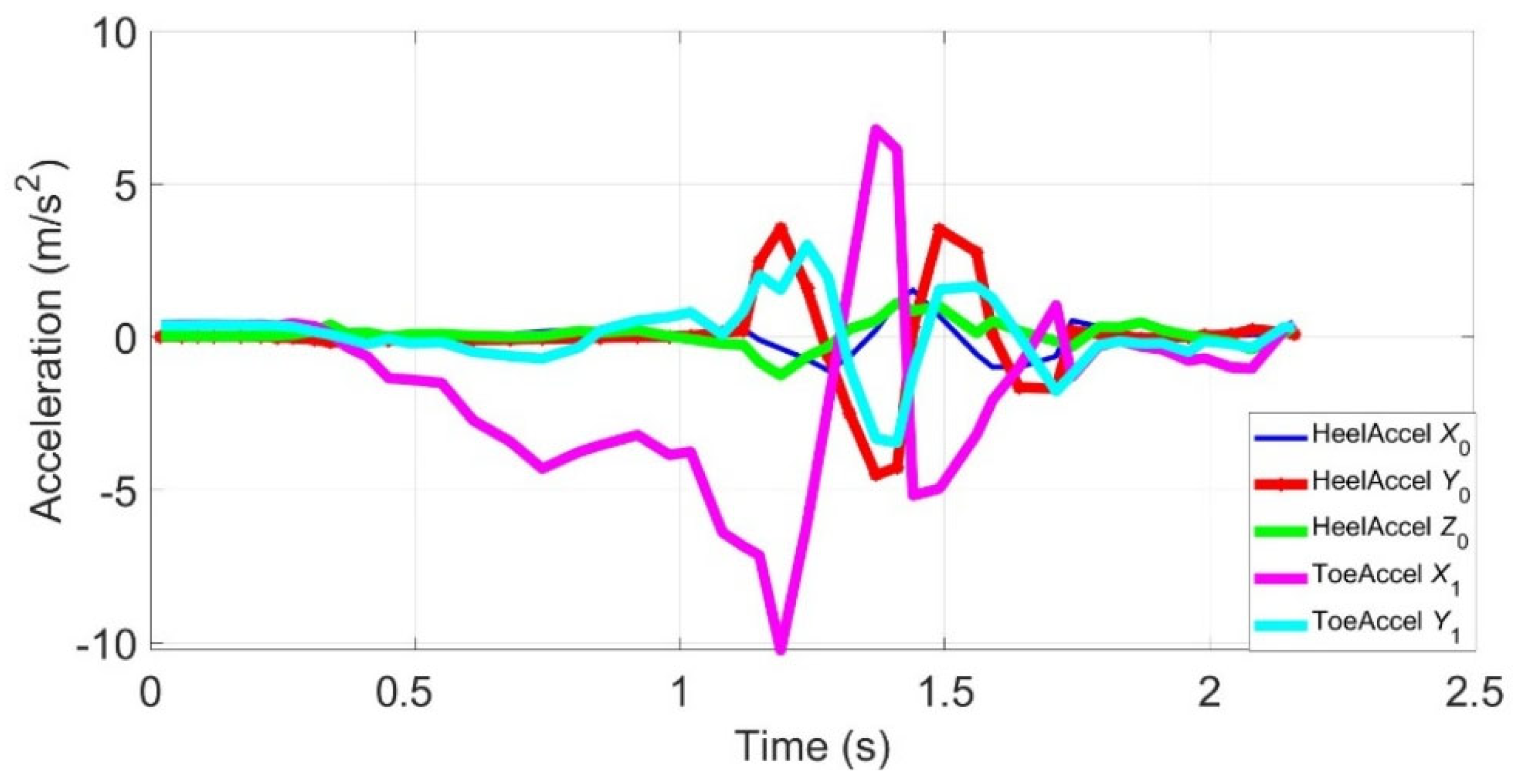

4.2. Monitoring Normal Walking

4.3. Detecting Inversion and Eversion Cycles

4.4. Foot Drop Monitoring

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pitchai, B.; Khin, M.; Gowraganahalli, J. Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 113, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Nam, D.; Ahn, B.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, D.Y.; Kwon, S.; Kim, J. Ankle dorsiflexion assistance of patients with foot drop using a powered ankle-foot orthosis to improve gait asymmetry. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeki, Y.; Yukihiko, A.; Masatsune, I.; Makoto, Y.; Kazuo, Y.; Kazuhiko, N. Gait Assessment Using Three-Dimensional Acceleration of the Trunk in Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 653964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massimiliano, P.; Alessio, M.; Brent, B.; Rajasumi, R.; Alfonso, F. Gait Analysis in Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: A Meta-Analysis. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2023, 10, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I.; Schmitz, G.; Effenberg, A.O. Effect of rhythmic auditory cueing on parkinsonian gait: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mold, J.W.; Vesley, S.K.; Keyl, B.A.; Schenk, J.B.; Roberts, M. The prevalence, predictors, and consequences of peripheral sensory neuropathy in older patients. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2004, 17, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, D.; Wagatsuma, K.; Shimada, T.; Ikushima, K.; Fujisawa, H. Reliability and Validity of Observational Gait Analysis by Physical Therapists: Possibility of Verifying Accuracy and Improving Technology in Visual Measurement of Joint Angles. Phys. Ther. Res. 2025, 28, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Shin, J.H.; Park, S.; Park, B.; Lee, W.H. Exploring the Reliability and Validity of Smart Insoles in Gait Assessment. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2025, 14, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.M.; Gomes, B.B.; Neto, M.A.; Amaro, A.M. A Systematic Review of Insole Sensor Technology. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, L.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H. Integration of Smart Insoles for Gait Assessment in Wearable Systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, K.; Ye, X. Research and Development of Ankle–Foot Orthoses: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I.; Narciss, S. Influence of taping on joint proprioception: A systematic review with between and within group meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I.; Narciss, S. Influence of taping on force sense accuracy: A systematic review with between and within group meta-analysis. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakho, R.A.; Abro, Z.A.; Chen, J.; Min, R. Smart Insole Based on Flexi Force and Flex Sensor for Monitoring Different Body Postures. Sensors 2022, 22, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Becsek, B.; Schaer, A.; Maurenbrecher, H.; Chatzipirpiridis, G.; Ergeneman, O.; Pané, S.; Torun, H.; Nelson, B.J. Real-Time Gait Phase Detection on Wearable Devices for Real-World Free-Living Gait. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riglet, L.; Nicol, F.; Leonard, A.; Eby, N.; Claquesin, L.; Orliac, B.; Ornetti, P.; Laroche, D.; Gueugnon, M. The Use of Embedded IMU Insoles to Assess Gait Parameters: A Validation and Test-Retest Reliability Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.; Kim, M.; Jung, D.; Kim, J.; Mun, K. Smart Insole-Based Abnormal Gait Identification Using Sequential Network Models. Digit. Health 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brognara, L.; Mazzotti, A.; Zielli, S.O.; Arceri, A.; Artioli, E.; Traina, F.; Faldini, C. Wearable Technology Applications and Methods to Assess Clinical Outcomes in Foot and Ankle Disorders. Sensors 2024, 24, 70593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, M.; Ielo, A.; De Pasquale, P.; Celesti, A.; De Nunzio, A.M.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Use of Wearable Sensors to Assess Fall Risk in Neurological Disorders. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2025, 13, e67265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Kwon, Y.; Huang, Y.; Kuczajda, M.; Soltis, I.; Yeo, W.-H. Flexible Smart Insole and Plantar Pressure Monitoring Using Screen-Printed Nanomaterials and Piezoresistive Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 7, 47153–47161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris, I.; Adam, J.M.; Calderón, P.A.; Sales, S. Fiber Optic Shape Sensors: A comprehensive review. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 139, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyetunji, O.; Rain, A.; Eckert, A.; Feris, W.; Zabihollah, A.; Priest, J.; Abu-Ghazaleh, H. A Smart Insole for Remote Gait Monitoring of Paralyzed Patients. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE MetroCon, Hurst, TX, USA, 13–14 November 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, R.; Venkadeshwaran, K.; Ranjan, P. Recent Advancements of Fiber Bragg Grating Sensors in n biomedical application: A review. J. Opt. 2024, 53, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Driller, M.; Ghai, I. Effects of joint stabilizers on proprioception and stability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. Sport. 2017, 25, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Song, G.; Conditt, M.; Noble, P.; Li, H. Fiber Bragg Grating Displacement Sensor for Movement Measurement of Tendons and Ligaments. Appl. Opt. 2007, 56, 6867–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Burnfield, J.M. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function, 2nd ed.; SLACK Incorporated: Thorofare, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Orlin, M.N.; McPoil, T.G. Plantar Pressure Assessment. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, T.F.; Gage, J.R.; Hicks, R. Gait Patterns in Spastic Hemiplegia in Children and Young Adults. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1995, 69, 437–441. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkandi, G.I.; Zabihollah, A. A Computational Model for Health Monitoring of Storage Tanks Using Fiber Bragg Grating Optical Fiber. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2011, 1, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure Parameter | Sensor/Device | Model/Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Strain/stress | FBG Sensors | FBG-MR0010, an array of 4 FBG sensors located 10 mm apart from (Micronor Sensors, Inc., Ventura, CA, USA). FBG sensors have wavelength of 850 nm and 300 nm grating period. |

| FBG Interrogator | FBGX100 with a wavelength range of 808–880 nm (FISENS®, Braunschweig, Germany) | |

| Acceleration | Accelerometer | Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense Lite, Model: Nina-B306 |

| Rotational angle | Gyroscope | Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense Lite, Model: Nina-B306 |

| Acceleration | Accelerometer | HiLetgo 3pcs GY-521, Model: MPU-6050 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oyetunji, O.; Rain, A.; Feris, W.; Eckert, A.; Zabihollah, A.; Abu Ghazaleh, H.; Priest, J. Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring. Actuators 2025, 14, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110531

Oyetunji O, Rain A, Feris W, Eckert A, Zabihollah A, Abu Ghazaleh H, Priest J. Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring. Actuators. 2025; 14(11):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110531

Chicago/Turabian StyleOyetunji, Oluwaseyi, Austin Rain, William Feris, Austin Eckert, Abolghassem Zabihollah, Haitham Abu Ghazaleh, and Joe Priest. 2025. "Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring" Actuators 14, no. 11: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110531

APA StyleOyetunji, O., Rain, A., Feris, W., Eckert, A., Zabihollah, A., Abu Ghazaleh, H., & Priest, J. (2025). Design of a Smart Foot–Ankle Brace for Tele-Rehabilitation and Foot Drop Monitoring. Actuators, 14(11), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110531