Analysis of Time Drift and Real-Time Challenges in Programmable Logic Controller-Based Industrial Automation Systems: Insights from 24-Hour and 14-Day Tests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

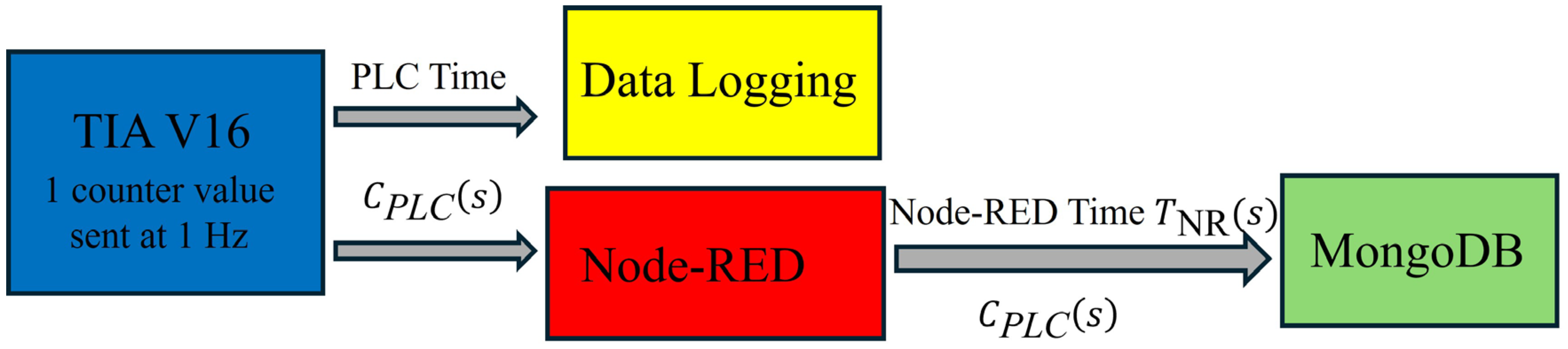

3. Methodology (Data Generation and Flow)

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. PLC and MongoDB

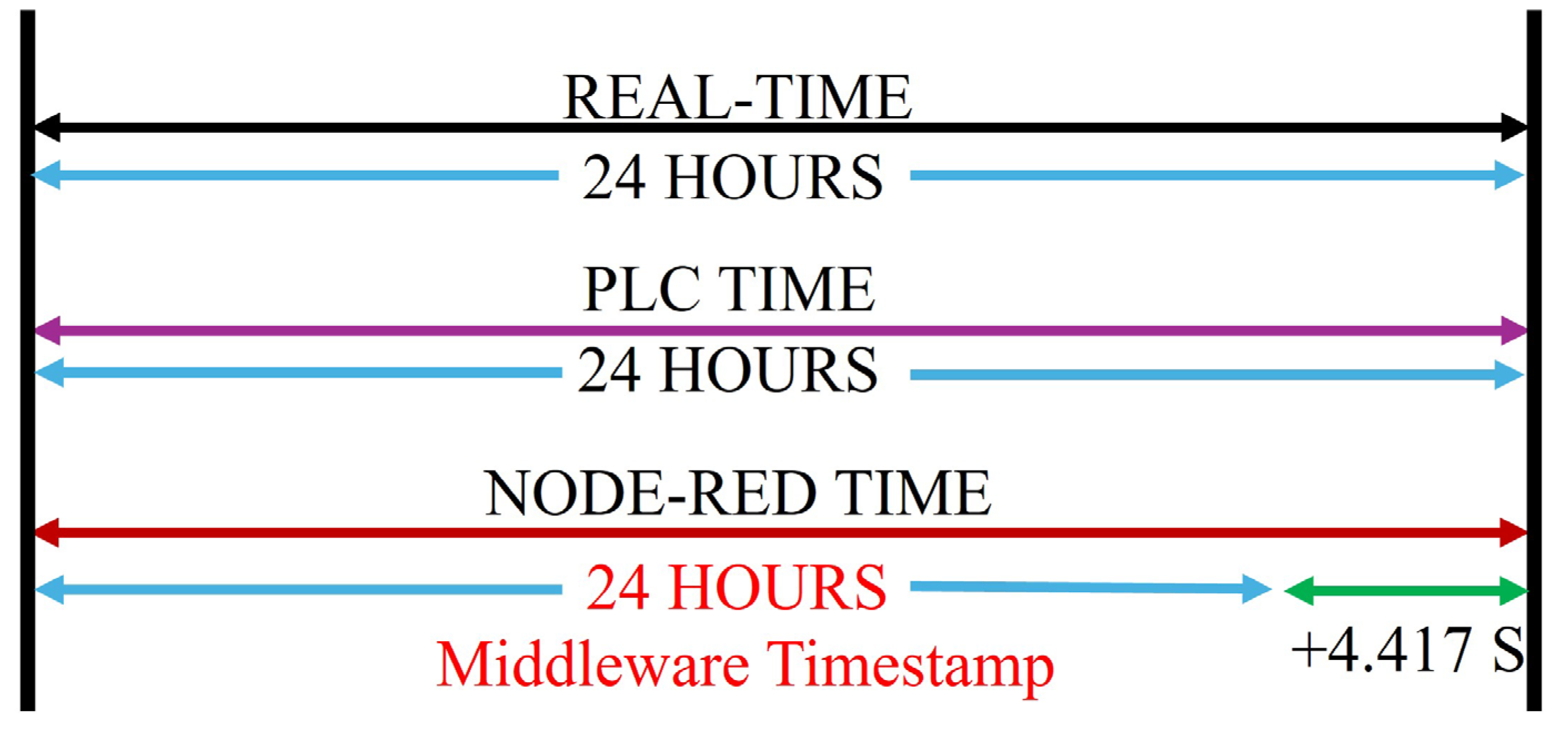

4.2. Time Drift for 24 H

4.3. Time Drift for 14-Day Test

4.3.1. Typical Operation with One Anomaly

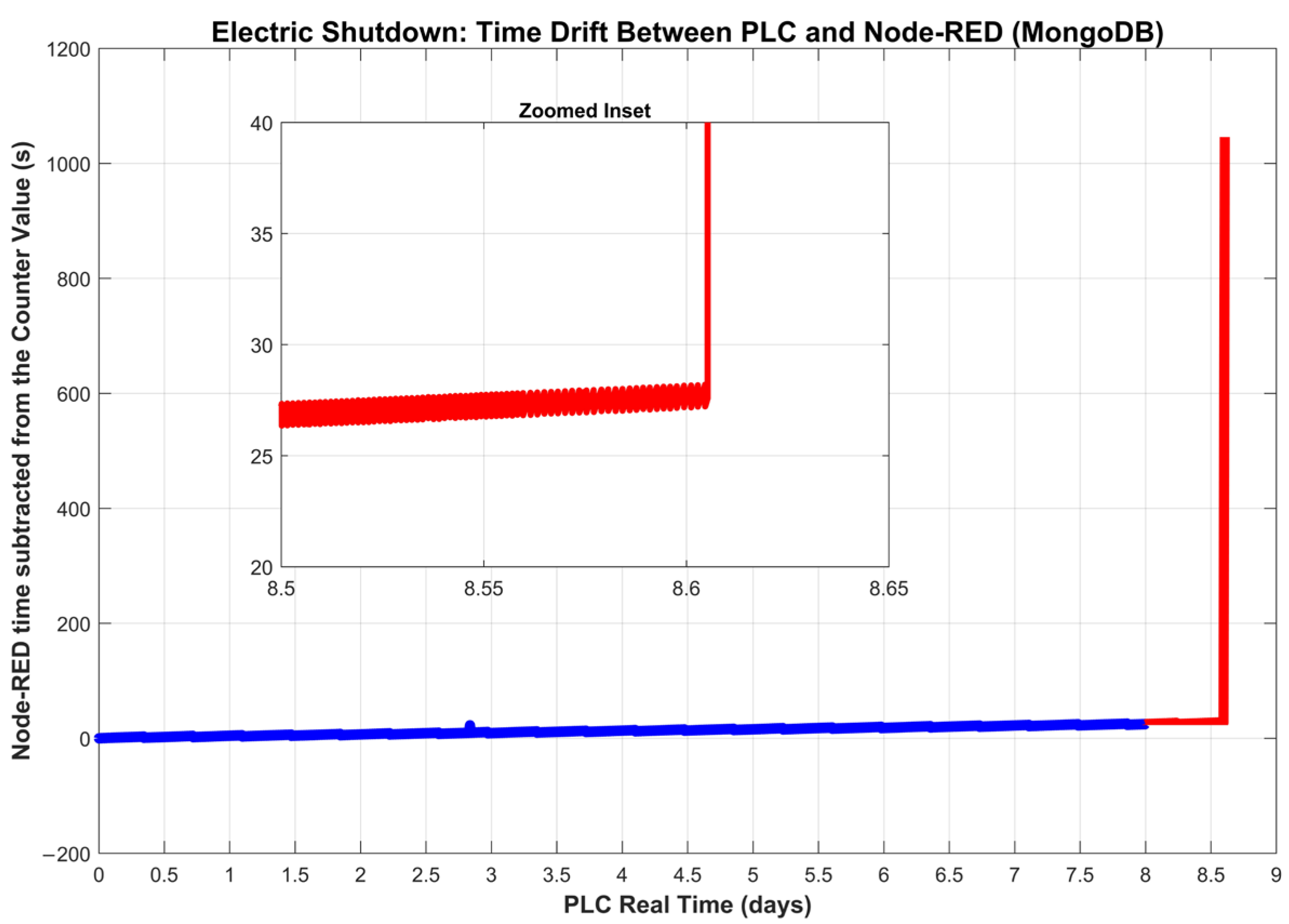

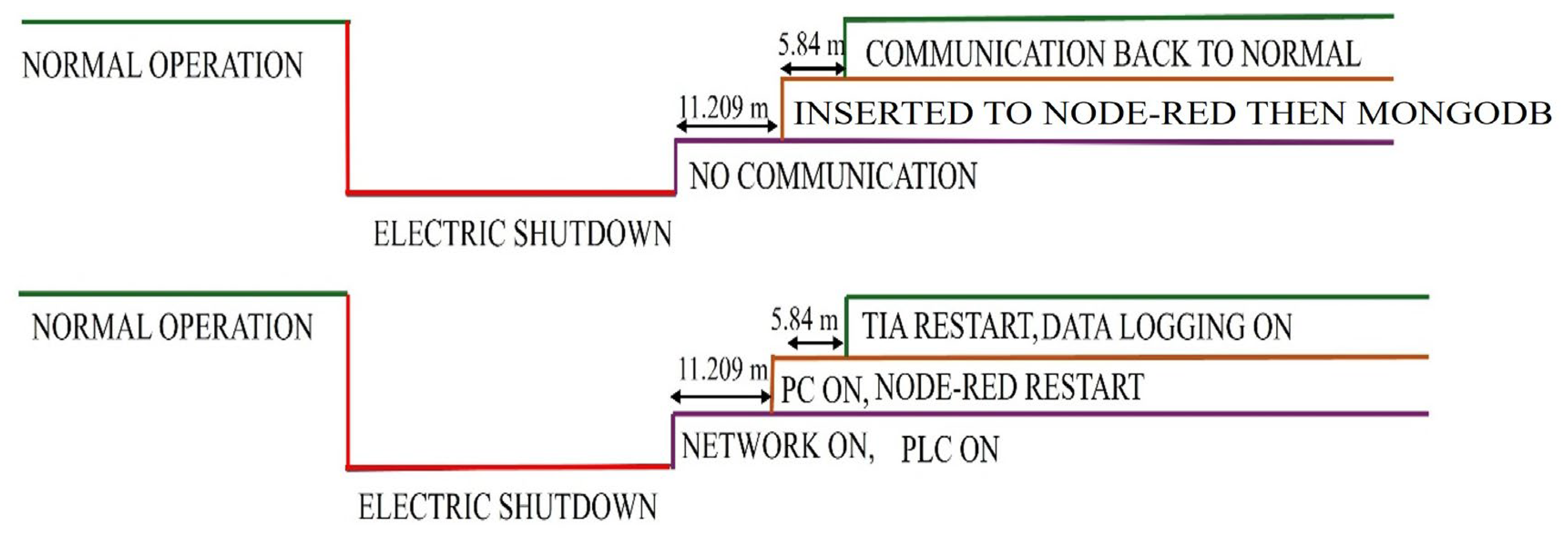

4.3.2. The Electric Shutdown

4.3.3. Time Drift of Day 12 to Day 14

4.4. PMV Calculation for the 24 H

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, Y.; Deschamps, F.; de Freitas Rocha Loures, E.; Ramos, L.F.P. Past, present and future of Industry 4.0—A systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3609–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.D.; Xu, E.L.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, M.; Lea, R. Toward a Distributed Data Flow Platform for the Web of Things (Distributed Node-RED). In Proceedings of the WoT ’14: 5th International Workshop on Web of Things, Cambridge, MA, USA, 8 October 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nițulescu, I.-V.; Korodi, A. Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition Approach in Node-RED: Application and Discussions. IoT 2020, 1, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, D.; Alonso-González, I. An Internet of Thing Architecture Based on Message Queuing Telemetry Transport Protocol and Node-RED: A Case Study for Monitoring Radon Gas. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, P.; Flammini, A.; Sisinni, E.; Rinaldi, S.; Brandão, D.; Rocha, M.S. Delay Estimation of Industrial IoT Applications Based on Messaging Protocols. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 2188–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, T.; Charbiwala, Z.; Friedman, J.; Cho, Y.H.; Srivastava, M.B. Exploiting manufacturing variations for compensating environment-induced clock drift in time synchronization. In Proceedings of the SIGMETRICS ’08: 2008 ACM SIGMETRICS international conference on Measurement and modeling of computer systems, Annapolis, MD, USA, 2–6 June 2008; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.A.; Chi, A.R.; Cutler, L.S.; Healey, D.J.; Leeson, D.B.; McGunigal, T.E.; Mullen, J.A.; Smith, W.L.; Sydnor, R.L.; Vessot, R.F.C.; et al. Characterization of Frequency Stability. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 1971, IM–20, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, D.W. Time and Frequency (Time-Domain) Characterization, Estimation, and Prediction of Precision Clocks and Oscillators. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelect. Freq. Contr. 1987, 34, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, M.; Lea, R. FRED: A Hosted Data Flow Platform for the IoT. In Proceedings of the MOTA ’16: 1st International Workshop on Mashups of Things and APIs, Trento, Italy, 12–16 December 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, C.; Bejarano, C.; Carlson, J.A. Time Drift Considerations When Using GPS and Accelerometers. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2019, 2, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baunach, M. Handling Time and Reactivity for Synchronization and Clock Drift Calculation in Wireless Sensor/Actuator Networks. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Sensor Networks, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–9 January 2014; SCITEPRESS—Science and and Technology Publications: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hauweele, D.; Quoitin, B. Toward Accurate Clock Drift Modeling in Wireless Sensor Networks Simulation. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM Conference on Modeling, Analysis and Simulation of Wireless and Mobile Systems, Miami Beach, FL, USA, 25–29 November 2019; ACM: Miami Beach, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Elsharief, M.; Abd El-Gawad, M.A.; Kim, H. FADS: Fast Scheduling and Accurate Drift Compensation for Time Synchronization of Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 65507–65520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, Q.; Gao, H. Drift Detection of Intelligent Sensor Networks Deployment Based on Graph Stream. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Han, Q.-L. Modelling and controller design for discrete-time networked control systems with limited channels and data drift. Inf. Sci. 2014, 269, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manias, D.M.; Chouman, A.; Shami, A. Model Drift in Dynamic Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žliobaitė, I.; Pechenizkiy, M.; Gama, J. An Overview of Concept Drift Applications. In Big Data Analysis: New Algorithms for a New Society; Japkowicz, N., Stefanowski, J., Eds.; Studies in Big Data; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 16, pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, I.; Austad, H. Real-time performance of industrial IoT communication technologies: A review. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 7399–7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, A.; Andó, M.; Pödör, Z. Data losses and synchronization according to delay in PLC-based industrial automation systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopetz, H.; Steiner, W. Temporal Consistency of Data and Information in Cyber-Physical Systems. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2409.19309. [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen, G.; Pautet, L. Special issue on reliable data transmission in real-time systems. Real-Time Syst. 2023, 59, 662–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, I.; Seijo, O.; Torrego, R.; Astarloa, A. IEEE 802.1 AS clock synchronization performance evaluation of an integrated wired–wireless TSN architecture. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 2986–2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenschlaeger, W.; Frick, F.; Christodoulopoulos, K.; Henke, T. A scalable factory backbone for multiple independent time-sensitive networks. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 119, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnierle, M.; Röck, S. Latency and sampling compensation in mixed-reality-in-the-loop simulations of production systems. Prod. Eng. Res. Devel. 2023, 17, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulagwu-Echefu, A.; Eneh, I.I.; Chidiebere, U. Mitigating the Effect of Latency Constraints on Industrial Process Control Monitoring Over Wireless Using Predictive Approach. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2021, 6, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Liu, W.; Jiao, X.; Haxhibeqiri, J.; Miranda, G.; Hoebeke, J.; Marquez-Barja, J.; Moerman, I. Hardware Efficient Clock Synchronization Across Wi-Fi and Ethernet-Based Network Using PTP. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 3808–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.T.; Ngo, H.Q.T. Enhancing time synchronization between host and node stations using a fuzzy proportional-integral approach for EtherCAT-based motion control systems. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamma, F.; Venmani, D.P.; Singh, K.; Jahan, B. Synchronization in Industrial IoT: Impact of propagation delay on time error. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Standards for Communications and Networking (CSCN), Munich, Germany, 6–8 November 2023; pp. 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, G.; Dittler, D.; Habiger, P.; Drath, R.; Weyrich, M. Data Integration for Digital Twins in Industrial Automation: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139129–139153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.; Hoher, S.; Huber, S. An OPC UA-based industrial Big Data architecture. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 21st International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN), Lemgo, Germany, 18–20 July 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkiva, F.; Bacher, N.; Krause, J.; van Niekerk, T.; Fernandes, J.; Notholt, A. ICT-Architecture design for a Remote Laboratory of Industrial Coupled Tanks System. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Learning Factories (CLF 2023), Reutlingen, Germany, 9–11 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patera, L.; Garbugli, A.; Bujari, A.; Scotece, D.; Corradi, A. A layered middleware for ot/it convergence to empower industry 5.0 applications. Sensors 2021, 22, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.H.; Mahdin, H.; Mohd, H.A. Latency Analysis of WebSocket and Industrial Protocols in Real-Time Digital Twin Integration. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2025, 73, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, M.; Peng, K. A missing manufacturing process data imputation framework for nonlinear dynamic soft sensor modeling and its application. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noufel, S.; Maaroufi, N.; Najib, M.; Bakhouya, M. Hinge-FM2I: An approach using image inpainting for interpolating missing data in univariate time series. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, A.A.R.; Elshennawy, N.M.; Fahmy, M. GMA: Gap Imputing Algorithm for time series missing values. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2023, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Thorburn, P.J. Handling missing data in near real-time environmental monitoring: A system and a review of selected methods. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 128, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Hu, D.; Hu, R.; Zhou, J. High-resolution electric power load data of an industrial park with multiple types of buildings in China. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zhao, C. FIGAN: A missing industrial data imputation method customized for soft sensor application. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 3712–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, L.; Ma, F.; Wu, C.; Zhang, K. Sensor Data Imputation for Industry Reactor Based on Temporal Decomposition. Processes 2025, 13, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is MongoDB?—Database Manual—MongoDB Docs. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/docs/manual/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

| Sections | Line Equation | Slope | Coefficient of Determination, R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | y = 0.000094x + 0.0000 | 0.000094 | 0.8869 |

| A2 | y = 0.000094x − 0.0005 | 0.000094 | 0.9048 |

| A3 | y = 0.000094x − 0.0010 | 0.000094 | 0.8428 |

| Counter | Node-RED Sending Time | Time Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 29,931 | 08:18:53.777 | 00:00:01.015 |

| 29,932 | 08:18:54.780 | 00:00:01.003 |

| 29,933 | 08:18:53.874 | −00:00:00906 |

| 29,934 | 08:18:54.873 | 00:00:00.999 |

| 29,935 | 08:18:55.877 | 00:00:01.004 |

| Counter | Node-RED Sending Time | Time Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 62,644 | 17:24:08.314 | 00:00:01.015 |

| 62,645 | 17:24:09.319 | 00:00:01.005 |

| 62,646 | 17:24:08.372 | −00:00:00.947 |

| 62,647 | 17:24:09.386 | 00:00:01.014 |

| 62,648 | 17:24:10.383 | 00:00:00.997 |

| Counter | PLC Time | Time Difference | Received by MongoDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 247,359 | 19:37:22.008 | 00:00:00.776 | YES |

| 247,360 | 19:37:23.224 | 00:00:01.216 | YES |

| 247,361 | 19:37:24.104 | 00:00:00.880 | NO |

| 247,362 | 19:37:25.032 | 00:00:00.928 | NO |

| 247,363 | 19:37:26.216 | 00:00:01.184 | YES, but 16.188 s later |

| 247,364 | 19:37:27.160 | 00:00:00.944 | NO |

| 247,365 | 19:37:28.120 | 00:00:00.960 | NO |

| 247,366 | 19:37:29.200 | 00:00:01.080 | NO |

| 247,367 | 19:37:30.216 | 00:00:01.016 | NO |

| 247,368 | 19:37:31.072 | 00:00:00.856 | NO |

| 247,369 | 19:37:32.008 | 00:00:00.936 | NO |

| 247,370 | 19:37:33.216 | 00:00:01.208 | NO |

| 247,371 | 19:37:34.088 | 00:00:00.872 | NO |

| 247,372 | 19:37:35.208 | 00:00:01.120 | NO |

| 247,373 | 19:37:36.056 | 00:00:00.848 | NO |

| 247,374 | 19:37:37.104 | 00:00:01.048 | NO |

| 247,375 | 19:37:38.168 | 00:00:01.064 | NO |

| 247,376 | 19:37:39.176 | 00:00:01.008 | NO |

| 247,377 | 19:37:40.136 | 00:00:00.960 | NO |

| 247,378 | 19:37:41.024 | 00:00:00.888 | YES, but 13.112 s later |

| 247,379 | 19:37:42.104 | 00:00:01.080 | NO |

| 247,380 | 19:37:43.024 | 00:00:00.920 | NO |

| 247,381 | 19:37:44.032 | 00:00:01.008 | NO |

| 247,382 | 19:37:45.152 | 00:00:01.120 | NO |

| 247,383 | 19:37:46.168 | 00:00:01.016 | NO |

| 247,384 | 19:37:47.224 | 00:00:01.056 | NO |

| 247,385 | 19:37:48.248 | 00:00:01.024 | NO |

| 247,386 | 19:37:49.120 | 00:00:00.872 | NO |

| 247,387 | 19:37:50.144 | 00:00:01.024 | NO |

| 247,388 | 19:37:51.248 | 00:00:01.104 | NO |

| 247,389 | 19:37:52.112 | 00:00:00.864 | NO |

| 247,390 | 19:37:53.032 | 00:00:00.920 | YES |

| 247,391 | 19:37:54.048 | 00:00:01.016 | YES |

| Counter | PLC Time | Time Difference | Received by MongoDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 750,067 | 15:16:02.112 | 00:00:01.088 | YES |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:01.003 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | NO |

| 750,068 | 15:16:03.115 | 00:00:00.000 | YES, but 11.209 min later |

| 750,069 | 15:33:13.048 | 00:17:08.933 | NO |

| 750,070 | 15:33:14.176 | 00:00:01.128 | YES, but 5.840 min later |

| Counter | PLC Sending Time | PLC Time Difference | Received by MongoDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,057,925 | 06:09:34.872 | 00:00:00.968 | YES |

| 1,057,926 | 06:09:35.824 | 00:00:00.952 | YES |

| 1,057,927 | 06:09:36.944 | 00:00:01.120 | YES |

| 1,057,928 | 06:09:37.856 | 00:00:00.912 | YES, but 2.011 s later |

| 1,057,929 | 06:09:38.984 | 00:00:01.128 | YES |

| 1,057,930 | 06:09:40.016 | 00:00:01.032 | YES |

| 1,057,931 | 06:09:40.928 | 00:00:00.912 | YES |

| 1,057,932 | 06:09:41.816 | 00:00:00.888 | YES |

| Counter | Node-RED Sending Time | Time Difference |

|---|---|---|

| 1,205,714 | 23:12:58.984 | 00:00:01.005 |

| 1,205,715 | 23:12:59.998 | 00:00:01.014 |

| 1,205,718 | 23:13:03.010 | 00:00:01.950 |

| 1,205,719 | 23:13:04.032 | 00:00:01.022 |

| 1,205,721 | 23:13:05.049 | 00:00:01.017 |

| 1,205,722 | 23:13:06.073 | 00:00:01.024 |

| 1,205,723 | 23:13:07.120 | 00:00:01.047 |

| Hours | Sum of the Predicted Missing Values | Absolute Differences [pc] | Relative Differences [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 7048.4 | 174.4 | 2.54% |

| 12 h | 7050.6 | 176.6 | 2.57% |

| 8 h | 7052.4 | 178.4 | 2.59% |

| 6 h | 7050.9 | 176.9 | 2.58% |

| 3 h | 7053.6 | 179.6 | 2.61% |

| 1 h | 7069.8 | 195.8 | 2.85% |

| 30 min | 7057.4 | 183.4 | 2.67% |

| 25 min | 7099.9 | 225.9 | 3.29% |

| 10 min | 7256.5 | 382.5 | 5.57% |

| 5 min | 7049.8 | 175.8 | 2.57% |

| 2 min | 7059.3 | 185.3 | 2.70% |

| 1 min | 6984.3 | 199.3 | 2.94% |

| Hours | Sum of the Predicted Missing Value | Absolute Differences [pc] | Relative Differences [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 2052.9 | 23.9 | 1.18% |

| 10 min | 2052.0 | 23.0 | 1.13% |

| 5 min | 2051.6 | 22.6 | 1.11% |

| 2 min | 2055.5 | 27.5 | 1.36% |

| 1 min | 2067.6 | 38.6 | 1.90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hijazi, A.; Andó, M.; Pödör, Z. Analysis of Time Drift and Real-Time Challenges in Programmable Logic Controller-Based Industrial Automation Systems: Insights from 24-Hour and 14-Day Tests. Actuators 2025, 14, 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110524

Hijazi A, Andó M, Pödör Z. Analysis of Time Drift and Real-Time Challenges in Programmable Logic Controller-Based Industrial Automation Systems: Insights from 24-Hour and 14-Day Tests. Actuators. 2025; 14(11):524. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110524

Chicago/Turabian StyleHijazi, Ayah, Mátyás Andó, and Zoltán Pödör. 2025. "Analysis of Time Drift and Real-Time Challenges in Programmable Logic Controller-Based Industrial Automation Systems: Insights from 24-Hour and 14-Day Tests" Actuators 14, no. 11: 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110524

APA StyleHijazi, A., Andó, M., & Pödör, Z. (2025). Analysis of Time Drift and Real-Time Challenges in Programmable Logic Controller-Based Industrial Automation Systems: Insights from 24-Hour and 14-Day Tests. Actuators, 14(11), 524. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14110524