Abstract

This study explores a stochastic guarantee cost control (GCC) for time-varying systems with random parameters and asymmetric saturation actuators by employing the integral reinforcement learning (IRL) method in the dynamic event-triggered (DET) mode. Firstly, a modified Hamilton–Jacobi–Isaac (HJI) equation is formulated, and then the worst-case disturbance policy and the asymmetric saturation optimal control signal can be obtained. Secondly, the multivariate probabilistic collocation method (MPCM) is used to evaluate the value function at designated sampling points. The purpose of introducing the MPCM is to simplify the computational complexity of stochastic dynamic programming (SDP) methods. Furthermore, the DET mode is utilized to solve the SDP problem to reduce the computational burden on communication resources. Finally, the Lyapunov stability theorem is applied to analyze the stability of time-varying systems, and the simulation shows the feasibility of the designed method.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, stochastic control has been extensively studied across numerous practical domains, including robotic systems [1], microgrid setups [2], intelligent transportation networks [3], and other practical control fields. Compared with deterministic system control, stochastic system control has problems such as computational complexity and model mismatch, which makes its design challenging [4]. In [5], the stochastic control problem was studied in data-driven model predictive control by using neural networks (NNs) or establishing a stochastic sampling model. A stochastic control approach applicable to discrete-time nonlinear systems was put forward in [6]. The security issues of stochastic systems were also addressed in [7]. A novel stochastic control method was designed for a linear system with multiplicative noise and input constraints in [8]. Regarding stochastic discrete-time linear systems under bounded input constraints, a receding horizon control technique was formulated in [9]. However, none of the studies mentioned above considered optimal control under asymmetric saturation actuators (ASAs).

Actuator saturation is a common nonlinear problem that can affect system stability and performance and also pose significant challenges to controller design. In [10], a robust adaptive fuzzy fault-tolerant path planning control method was proposed to solve the actuator saturation problem. In [11], an adaptive compensation technique integrated into the backstepping framework was proposed for controlled systems with actuator saturation. In [12], an adaptive NN control method was proposed for systems with input saturation nonlinearities. These methods have symmetric saturation actuators, and in order to optimize control strategies, researchers have proposed ASA control strategies to ensure the safety and stability of the controlled system. In [13], a composite adaptive control method was proposed for tethered aircraft systems with ASAs. Ref. [14] proposed a sliding mode control method with ASAs for vehicle systems. In [15], an asymptotic stabilization method was proposed for unmanned surface vessels with actuator dead zones and bow constraints. However, the methods mentioned above do not consider the optimal performance of the controlled system. The adaptive dynamic programming (ADP) algorithm, which is a method that combines dynamic programming (DP) and integral reinforcement learning (RL) ideas, addresses the “curse of dimensionality” issue in conventional DP [16,17,18,19]. For the Itô-type stochastic systems, the authors employed the ADP method to address the tracking control issue in [20]. In [21], a self-learning optimal operation control method based on a compensator and RL was proposed for input-constrained dual-time scale systems. A Q-learning-based fault-tolerant control method was designed without using the knowledge of system function in [22]. In [23], an RL-based optimal control (OC) method was devised for linear stochastic systems, with the least squares approach adopted to derive approximate optimal solutions. Further, an integral RL-based model-free tracking approach was developed for linear stochastic systems in [24]. In [25], an ADP-based GCC method was presented for nonlinear systems. By introducing the GCC approach, one can ensure that the control performance index is below a certain bound. The above methods may cause unnecessary waste of communication resources because these approaches are designed based on time-triggered control mechanisms.

Event-triggered control (ETC) is a non-periodic control strategy based on triggering conditions; the core idea of ETC is to determine when to update control signals or communicate through preset event-triggered conditions, rather than traditional periodic sampling or time triggering [26,27]. In [28], for Itô-type time-delayed stochastic systems subject to uncertainties, an OC strategy under the ETC mechanism was designed by using the ADP method and constructing an actor–critic architecture. Moreover, an optimal consensus control (OCC) strategy was proposed by using fuzzy technology for stochastic MASs with time delays in [29]. To further decrease control input update frequency and increase communication resource utilization, the dynamic event-triggered control (DETC) mechanism serves as an upgraded version of the conventional ETC approach. It is a dynamically adjustable mechanism that further optimizes resource usage, system performance, and adaptability [30]. In [31], under the DETC mechanism, the H2/H∞ problem was explored for partially unknown nonlinear stochastic systems by employing the ADP algorithm. In [32], focusing on uncertain microgrids, control inputs and external disturbances were treated as two participants in zero-sum differential game scenarios. Under the DETC mechanism, the authors put forward a frequency recovery control approach based on integral reinforcement learning (IRL). In [33], a dynamically adjustable triggering condition was designed based on the OC method for stochastic nonlinear systems by using backstepping technology and the RL algorithm in the DETC mode.

In addition, it is difficult to obtain accurate mathematical models for actual control systems, and estimating system dynamics through extended simulation experiments is a conventional method [34,35]. If random time-varying parameters exist in actual nonlinear controlled system dynamics, the expected control performance function is always estimated by using uncertainty evaluation methods [36], such as the Monte Carlo (MC) approach and its extensive version, which are implemented based on simulation experiments [37]. However, approximating the expected control performance index requires a large number of simulation experiments when using the MC method and its extensive version [38]. In [39], to simplify the computational complexity, the MPCM method, which is an effective technology for estimating uncertainties, was used to estimate the expected value of the cost function by taking values at certain specific sampling points. Stochastic GCC approaches have been put forward by using RL (or IRL) and MPCM methods in [36,40]. However, the issue of ASAs remains unaddressed. In our design, we put forward a GCC approach in DETC mode for stochastic systems subject to ASAs by employing the the MPCM integrated with IRL algorithms. The main contributions are as follows:

- 1.

- This study develops an innovative DETC-based GCC approach for stochastic systems by using IRL algorithms with the MPCM. This approach can ensure that the system performance index is less than a certain upper bound.

- 2.

- By solving an improved HJI equation by designing a modified long-term performance cost function, the control inputs under ASAs can be obtained via an actor–critic–disturbance NN structure.

- 3.

- Through the introduction of dynamic parameters into triggering conditions in the DETC mechanism, the update rule for control inputs can be adjusted dynamically, which can reduce the computational complexity of sampling data.

This paper’s structure is arranged as follows. Section 2 presents the issue description. Section 3 develops stochastic systems’ optimal GCC design via a modified HJI equation. A stochastic GCC method is designed by using the MPCM and IRL in Section 4. Section 5 presents the event-triggered structure for optimal GCC. A simulation example is shown to verify the feasibility of the strategy in Section 6. The conclusion is shown in Section 7.

2. Problem Statement

Consider the following stochastic system [36,41]:

where represents a time-varying matrix related to the stochastic vector . Matrices and are the system functions. The disturbance policy, control input, and system state are , and , respectively. The control signal satisfies , , for . and stand for the smallest and largest constraint limits of control inputs . is the sample function of the pth element in the random vector , and the dynamics of the sample system (1) are ordinary differential equations; exhibits good behavior.

Assumption 1.

The system (1) satisfies Lipschitz continuity over the compact set [36,42,43]. In addition, , where is a positive constant.

Remark 1.

Unlike general stochastic models with drift and diffusion terms, Ref. [41] focused on zero-sum game studies of time-varying stochastic systems (1) with environment-influenced random variables. The system model (1) is applicable to practical scenarios. For example, aircraft systems have been modeled as , where K is a weather-dependent random variable, refers to regulated thrust, and is the interference force. Other fields also explore such system dynamics [44].

Assumption 2.

Let denote a positive constant; the disturbance approach is such that , with .

The system (1) with nominal form becomes

The positive definite matrix is represented as , and the long-term control performance function is

with

where . For , .

By calculation, we have

where and .

Remark 2.

Ref. [36] studied the GCC problem of stochastic systems under an event-triggered mechanism. However, some practical systems face the nonlinear control problem of ASAs [13,14,15], which limits the application of the method in [36]. Therefore, this paper proposes a GCC strategy for stochastic systems under the ASA condition with . By introducing a non-quadratic function related to the control input ρ to relax the asymmetric constraints and incorporating dynamic parameters into the triggering condition, the number of communications can be effectively reduced, and the utilization rate of communication resources can be further improved.

Within our design framework, the primary objective is to establish a GCC strategy for systems with ASAs by solving the HJI equation, which can ensure that the cost function is less than a certain upper bound and guarantee the stability and optimal control performance of stochastic systems under the DETC mechanism.

3. Stochastic Optimal GCC Design

In our design, an auxiliary policy is designed as ð, and the auxiliary system is established as

Let , where represents a pre-specified disturbance attenuation level.

The modified cost function is

The value function is

The derivative value of is

Let , inspired by [36,41], the Hamiltonian function is designed in the form of a mean, which is given by

Bellman’s equation refers to the principle of optimization in DP problems. In light of Bellman’s optimality principle, the following holds:

with , , and being the worst-case disturbance policy, optimal control signal, and optimal value function, respectively. By calculation, we have

where .

Based on (8), (12) and (13), the HJI equation is restructured as

where is an identity matrix, which satisfies and .

Assumption 3.

and are denoted as positive numbers. is continuously differentiable, which satisfies .

Remark 3.

Due to the existence of uncertainty and random parameters, the OC problem of system (1) is difficult to solve. The GCC problem can obtain the upper bound of the cost function of system (1), which is the basic idea of the GCC problem. This article constructs an auxiliary system, and by solving the optimal value function of the auxiliary system, the guaranteed cost (GC) function of the original system (1) can be obtained; that is, the value function of the auxiliary system is the optimal GC function of the original system. A related theorem is given as follows.

Theorem 1.

Considering system (1), define the cost function of auxiliary system (4) as (5); the asymptotic stability characteristic in the mean of stochastic system (1) can be guaranteed if a differentiable value function satisfies the HJI equation in (14) and the asymmetric cost control signal in (10) and the auxiliary policy in (11) are utilized.

Proof.

Choose the candidate Lyapunov function as

Through the addition and substitution of , we derive

Using Assumption 2 and the inequality , one obtains

Integrating Equation (18) over the interval , we have

4. Stochastic GCC Method Design via MPCM and IRL Algorithm

In this section, a novel stochastic GCC method is proposed for the controlled system with asymmetric constrained inputs by using the MPCM and IRL algorithms.

Using (7), we derive the integral Bellman equation based on the optimality principle as with . For any admissible control policies , the value function satisfies the condition that

Accordingly, one obtains

where is the Bellman error.

Remark 4.

Equation (21) will be employed in the subsequent on-policy IRL design procedure. In our framework, the IRL algorithm serves to drive the Bellman error in (21) toward zero.

As , converges to after several iterations in the learning process, and concurrently, approaches .

4.1. On-Policy GCC Design

By designing an NN that includes the activation function, the expected weight vector and the approximation error are denoted as , , and , respectively. We approximate the value function as

Let denote the estimated value for . At time step , the estimate value of is

Based on [40] (Th.2), we adopt the MPCM to reduce the number of simulations from to , which enables the prediction of the output mean of the system mapping . In this part, the GCC algorithm for random systems with stochastic uncertainty is presented in Algorithm 1.

The specific steps of Algorithm 1 include the following.

(1) Select a set of sampling points for the uncertain variable based on the MPCM and calculate the cumulative cost function for the future time period at each sampling point. This function is composed of the output estimate of the next evaluation critic NN and the integral term containing control energy consumption and state cost in the current time period. (2) Calculate the mathematical expectation of the function values at all sampling points to obtain the updated value function estimate for this iteration, denoted as . With this estimated value as the objective, update the weight vector of the evaluation NN by solving the HJI equation so that its output accurately matches the value function estimate. (3) Using the gradient information of the updated value function, design control strategy and disturbance strategy , respectively.

| Algorithm 1 Model-based GCC algorithm for stochastic uncertain system (1). |

| Initialization Set initial admissible policies and . Step 1: A set of sampling points for the uncertain variable is selected on the basis of the MPCM ([40], Section II). Compute the value of at each sampling point: Step 2: Compute by computing the mean value of . Step 3: Update on the basis of solving the HJI equation: Step 4: Design the control pairs via Let s be updated as . If where is a small positive number and stops at step 4; Otherwise, please return to step 1. |

Here, we define a new system function involving the uncertain parameter as . From (20), it follows that . Specifically, select a set of samples according to the probability density functions (pdfs) of the uncertain parameters , and then compute the value of via simulating at these chosen samples. Suppose the degree of each uncertain variable is updated to ; can be expressed as

Using the MPCM, a low-order mapping is used to approximate as follows:

On the basis of [40] (Th.2), one obtains .

Lemma 1.

Proof.

Using [40] (Th.2) and the relation , the control pairs can be derived from (10) and (11). To establish this theorem, we need to show that the optimal solution obtained by evaluating is identical to that derived from computing the reduced-order mapping . The equivalence of these two optimal solutions are proven via a contradiction method, as detailed in [39] (Th.1). □

4.2. IRL-Based GCC Design with Asymmetric Constrained Inputs

Unlike Algorithm 1, an IRL-based GCC method is developed for the system (1) without relying on the knowledge of function B and C. Based on [45], two exploration signals and are, respectively, added to the control policies and . Consequently, the system (4) becomes

The specific steps of Algorithm 2 include the following.

| Algorithm 2 IRL-based GCC algorithm for system (1) with asymmetric constrained control. |

| Initialization Set the initial admissible policies and .

Step 1: Choose a set of sampling points for the uncertain variable based on MPCM ([40], Section II). For each sampling point, compute the value of Step 2: Compute by calculating the mean of . Step 3: Update , and through solving the HJI equation: Set s to . If , where is a chosen positive number, end at step 3; otherwise, return to step 1. |

(1) Based on the MPCM, select a set of sampling points for the uncertain variable and calculate the cumulative cost function for the future time period at each sampling point. This function consists of the integral term containing the state penalty and control cost in the current time period, as well as the output estimate of the evaluation NN at the next time. (2) By calculating the mathematical expectation of the function values at all sampling points, the updated value function estimate for this iteration, , is obtained. (3) Solve an HJI equation embedded with exploration signals , , while updating the value function , control strategy , and disturbance strategy .

Based on (34), one obtains

Algorithm 2 presents the GCC approach via the MPCM and IRL algorithm, where the target control policies can be approximated through

where the activation functions are denoted as and , the expected weight vectors are denoted as and , and approximation errors are denoted as and . The subscripts and ð represent the actor NN and disturbance NN, respectively.

The control pairs in actual situations are

Theorem 2.

The auxiliary system of controlled system (1) is given as (4). The value function and control pairs are approximated via (23), (38) and (39), respectively. Assume Algorithm 2 converges. At each iteration, the MPCM is used to sample from the uncertain parameters; , and given by (33) will ultimately converge to the optimal values , , and .

Proof.

The solution obtained using the GCC algorithm based on IRL has been proven to be the same as the solution obtained using the GCC algorithm with asymmetric constraint control based on IRL in [46] (Th. 3). The prior conclusion derived via the MPCM for each sample point holds valid as well. Therefore, the two approaches achieve identical optimal value functions. □

5. Event-Triggered Construction of Optimal GCC

Time-triggered control strategies involve substantial data transmission, which causes computational overload. In contrast to time-triggered methods, this section presents a GCC approach in the DETC mode for the stochastic system (1) based on Theorems 1–2 and Lemma 1, aiming to decrease the unnecessary consumption of communication resources.

5.1. Event-Triggered GCC Design

The control pairs will update when the triggering condition is violated with the DETC strategy. At each triggering instant, , where stands for the j th sampling moment. The event-triggered error is

For , holds when . Based on (40), at triggering instants, the ETC policies become

By applying (41) and (42), and considering system (4) for all , the Hamiltonian function in (8) becomes

where and .

Substituting (44) and (45) into (43), the result is

Assumption 4.

The control pairs are Lipschitz-continuous, satisfying

where and are positive constants, and .

Lemma 2.

Given that Assumption 4 is valid, the following inequality holds:

where is given in (52).

Proof.

Subtracting (14) from (43), we have

Based on (47), we can get

where with . Using Young’s inequality, we get .

Based on (50), we have

where . □

Theorem 3.

Assuming that is a continuous function satisfying the improved HJI Equation (14) and the OC pairs are given as (44) and (45), then system (1) is mean asymptotically stable if the following condition holds:

where α is the designed parameter, , , and is the trigger threshold. is given in (52). The internal dynamic signal is

Proof.

The Lyapunov function is , where and .

In light of (43), the following holds:

By substituting from (44) and from (45) into (1), and relying on (55) and Lemma 2, one obtains

where denotes the smallest eigenvalue of Q.

According to (54), we obtain

Taking (56) and (57) into account together, if the condition (53) holds, we derive , for any . According to [36] (Lemma 1) and Assumption 3, the system (1) achieves mean asymptotic stability. □

Theorem 4.

Consider system (2); when adopting the optimal ETC policy from (44) and employing the OC signal , the following result is obtained:

Proof.

With respect to any admissible control function , by referring to (4), (6), and (7) and calculating the system dynamics in (1), one obtains

On the basis of (8), one obtains

Based on (60), we have

According to (61), Assumption 2, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, and , we obtain

Applying to (62), one obtains the result (58). □

5.2. NN-Based Control Design

Based on Theorem 4, we have , and the GCC algorithm using IRL is used to achieve an approximation of . In the proposed method, is approximated by (22). Based on the work in [47], the optimal GCC pairs are given as

where and denote the event-sampled approximation errors.

Based on (14), (63) and (64), the HJI equation takes the form

where . , and .

Assumption 5.

The actor, critic, and disturbance NNs, the NN weight vectors, activation function, reconstruction errors, and gradient of relevant parameters are bounded, which satisfy ; , , , , , , and , respectively, where , , , , , , , , , , , and are positive constants.

The estimates for , and ð are expressed as

where , and stand for the estimates of , and , respectively.

Using (23) and (31)–(33), the residual error can be given as

where and . Design a new augmented weight vector as and the target weight vector . Denote

Then, we have

with .

Let , denote an adaptive gain parameter; the weight adjustment rule is developed as

Assumption 6.

is continuously excited within the interval of , and one obtains

where , , , and and are constants.

Considering and , we define the augmented system state as , we have

Furthermore, one obtains

Here, , where .

Remark 5.

The residual error , which requires minimization in (67), is derived from the expectation of the function . Detailed procedures for calculating this expectation are provided in [40].

5.3. Stability Analysis

Theorem 5.

The ETC policies are given as (66b) and (66c) for the dynamical system (4), and the weight adjustment law is designed as (70). The system states and NN weight estimation errors are uniformly bounded (UB) in the mean. The triggering condition is designed as

where and are defined in (81), . The internal dynamic signal is given by

Proof.

A Lyapunov function is chosen as

with , , and .

Case 1: When ,, based on (4), (66b) and (66c), one obtains

Based on (22), we can obtain

According to and Assumption 5, we get

Substituting (77) into (10), one obtains

where and with , . , is selected between and and is an approximate value of .

According to , (79a) and (79b), we get

As proved in [48], , and one has

where and .

According to (12), we get

By calculating Formula (69), the residual error is re-expressed as follows:

Based on (65), one obtains

where

where , with being a positive number.

Denote , and , where T is a small positive number. Then, we have , and . Based on Assumption 5, we have with .

Then, we have

where .

Based on (70) and (83), we have

where , and .

Using Equations (81) and (91), becomes

If the triggering conditions (74) and (75) hold, one obtains

where .

We select the interval T and the parameter , under the condition that . Let parameter T be set such that ; then given that

Case 2: For any , the derivation of is given by

Considering Case 1, decreases strictly monotonically over the interval . This implies for all . Then, we have when calculating the limits on both sides of this inequality. Given this result, it follows that

Furthermore, for , , according to Case 1, constitutes a continuous difference function, so it follows that . Based on (94) and (95), we derive .

Based on the above analysis, the proof is completed. □

6. Simulation

Consider the following stochastic system [36]:

with the system states and control policy being denoted as and , respectively. d is the disturbance policy. The control policy satisfies . The uncertain term is with , and . , is a random variable that satisfies a uniform distribution, and its pdfs are the same as example 1 in the simulation in [36].

Through calculation, one obtains . Set the following auxiliary system as

where denotes the auxiliary disturbance policy. The original state is and . The activation function is defined as follows: , ; the weight vectors are , , and . The sample size used by the MPCM is 16. Table 1 shows the simulation parameters.

Table 1.

Parameter settings.

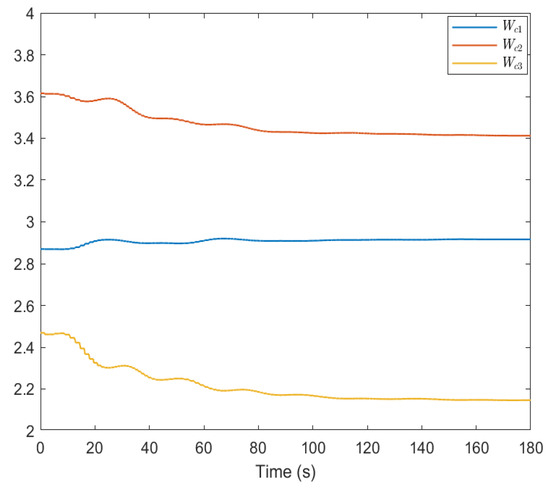

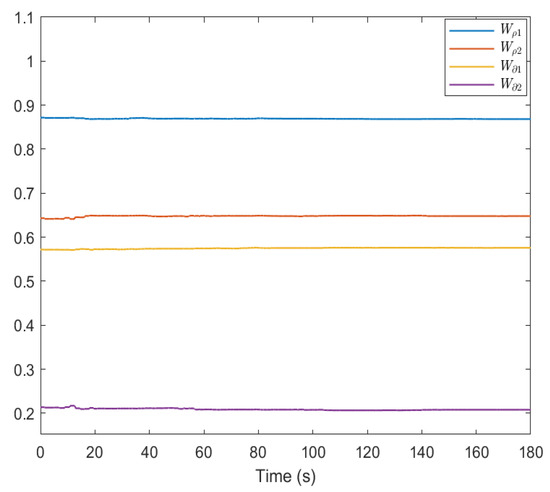

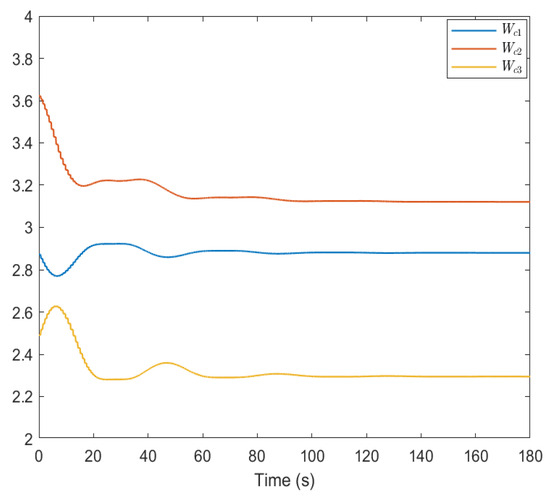

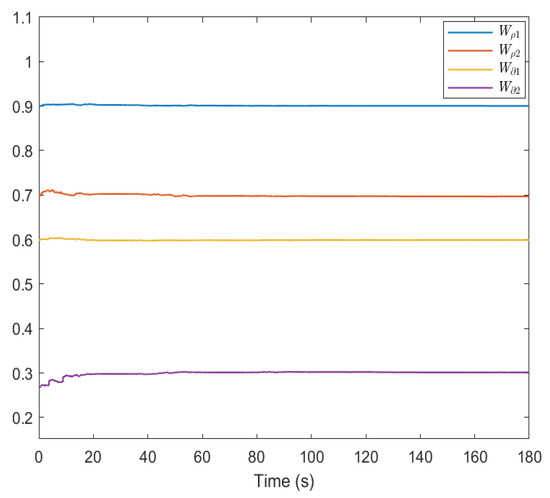

The weight curves of NNs are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The weight updates of the critic, actor, and disturbance NNs gradually approach , , and , respectively. Based on this weight convergence value of the critic NN, we can obtain that the GC of the original system is 17.86.

Figure 1.

Weight trajectories of the critic NN in our design.

Figure 2.

Weight curves of actor and disturbance NNs in our design.

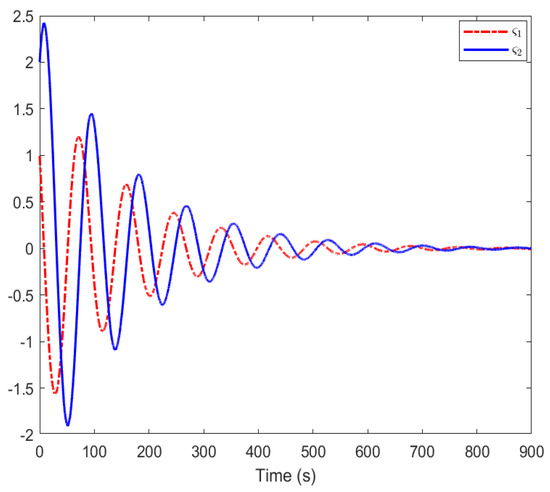

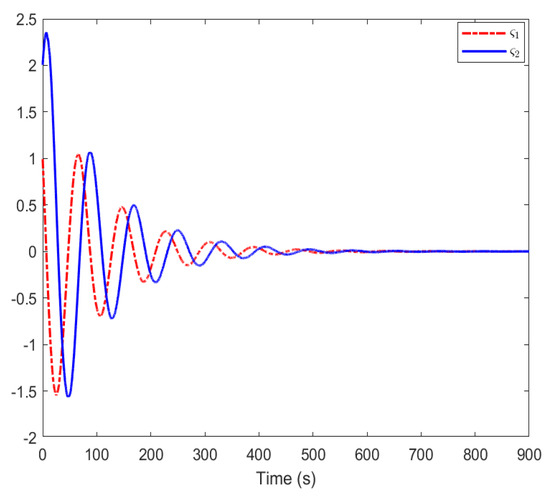

Figure 3 shows the system state curves. Evidently, all state trajectories are capable of eventually converging to the equilibrium point.

Figure 3.

System state curves in our design.

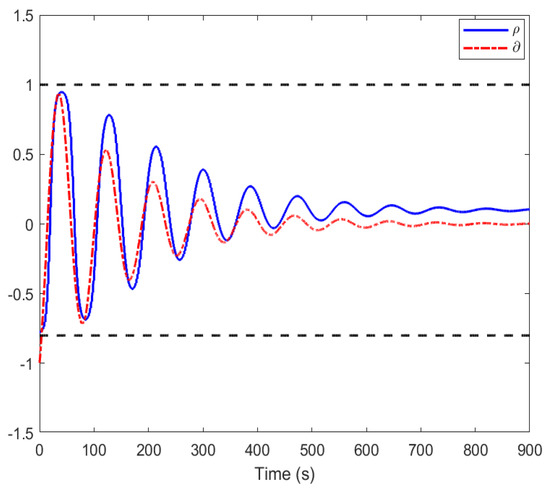

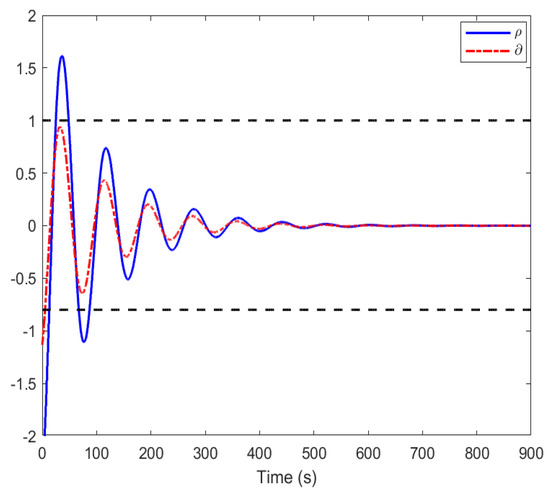

Figure 4 gives the variation curves of control pairs according to the DETC mode. It is shown that, compared with the baseline, the curve of the control policy obtained by our designed method stays within the range of −0.8 to 1, which proves the effectiveness of the designed method with ASAs.

Figure 4.

The change curves of the event-triggered optimization control strategy and worst-case disturbance strategy in our design.

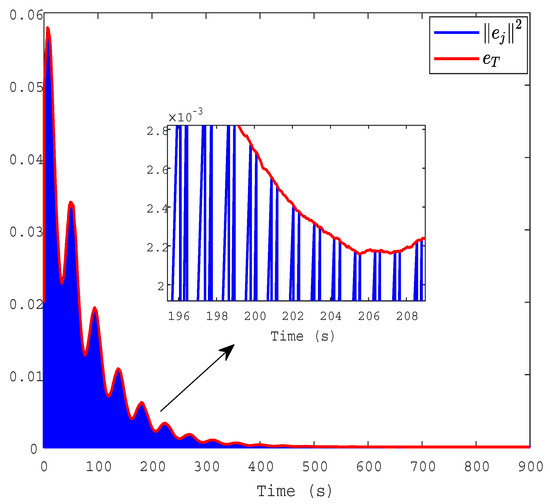

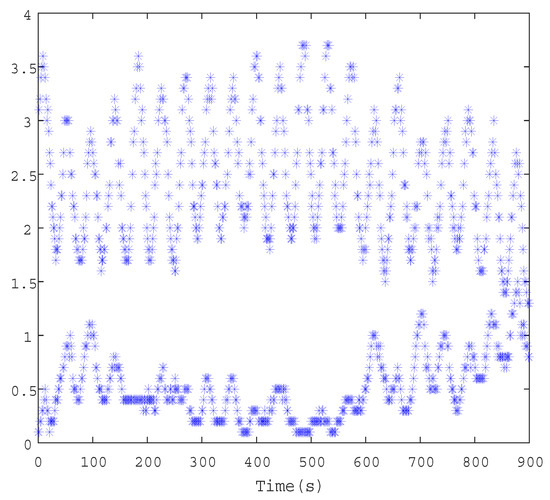

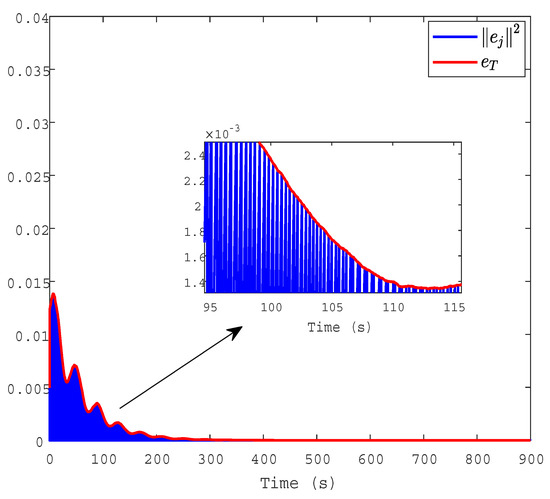

Figure 5 shows the trajectories of and . By using the DETC method, the number of controller updates can be greatly reduced. The sampling period of ETC is given in Figure 6. It displays the time interval between the previous and the current triggering moment. The triggering frequency is dynamically adjusted according to the triggering condition.

Figure 5.

The triggering condition of and in our design.

Figure 6.

Sampling period of the learning stage in our design.

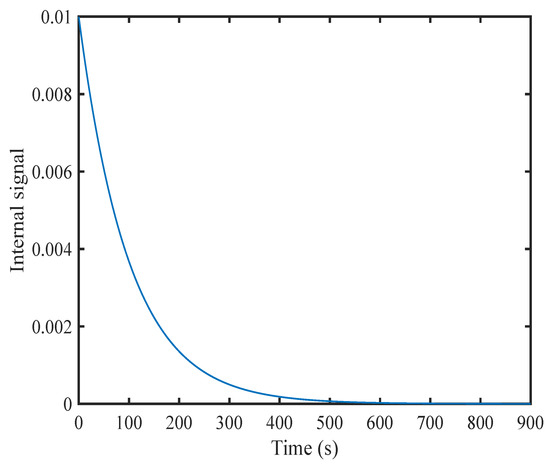

Figure 7 illustrates the dynamic evolution process of internal signals within the DETC framework. It is clear that the trajectory of internal parameter changes is always greater than 0 and decreasing.

Figure 7.

The change curve of the dynamic signal in the triggering condition in our design.

To demonstrate the control performance of the approach proposed in our design, a comparative simulation is given as follows by using the method proposed in [36].

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the convergence of the NN weight vectors. The weight updates of the critic, actor and disturbance NNs gradually approach , and , respectively.

Figure 8.

Weight trajectories of the critic NN by using the method in [36].

Figure 9.

Weight curves of actor and disturbance NNs by using method in [36].

Figure 10 shows the system state curves obtained by using the method in [36].

Figure 10.

System state curves by using method in [36].

Figure 11 shows the variation curves of control pairs based on the ETC mode obtained by using the method in [36]. The blue line denotes the variation curve of the control input, indicating that it exceeds the range of −0.8 to 1. Figure 4 is within the range of −0.8 to 1. By comparing Figure 4 and Figure 11, it is clear that the control strategy in our design exhibits excellent performance.

Figure 11.

The change curves of the event-triggered optimization control signal and worst-case disturbance signal by using the method in [36].

Figure 12 shows the triggering conditions of and under event-triggering mode. It is obvious that the ETC signal requires 2574 state samples, while the DETC strategy proposed in this paper only uses 2028 state samples. It is evident that the DETC proposed in this article can improve controller updates by up to 21.2%.

Figure 12.

The triggering condition of and by using the method in [36].

7. Conclusions

In our design, we have proposed dynamic event-triggered IRL-based control approach for a stochastic system with random parameters and ASAs. Firstly, a modified HJI equation has been formulated. Applying the actor–critic–disturbance NN architecture, both the OC signal under ASAs and the worst-case disturbance strategy have been derived by solving an improved HJI equation. Secondly, the MPCM has been employed to estimate the value function at specific sampling points. The utilization of the MPCM can reduce the computational complexity of sampling data in simulation experiments. Thirdly, through the introduction of dynamic parameters into the triggering conditions, the control input has been adjusted dynamically. Moreover, when the triggering condition is met, the weight values of NNs can be tuned in a synchronous manner, which has significantly enhanced the efficiency of communication resource usage. Furthermore, the Lyapunov stability theorem has been employed to analyze and verify the time-varying system’s stability. Finally, simulation results have confirmed the efficacy of the developed approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, M.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.X. and Y.L.; rigorous analysis, J.Z.; supervision, Z.G.; data curation, J.Z. and Z.M.; writing—review and editing, M.X.; funding acquisition, Y.L.; visualization, J.Z. All authors have reviewed and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62403329).

Data Availability Statement

In terms of the data availability, if a researcher requires data from this article, the corresponding author can provide the simulation data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xie, M.; Shakoor, A.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, B. Optical manipulation of biological cells with a robot-tweezers system: A stochastic control approach. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2020, 67, 3232–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazmohammadi, N.; Tahsiri, A.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Stochastic predictive control of multi-microgrid systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5311–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Wu, C.; Wen, J. Vehicle longitudinal stochastic control for connected and automated vehicle platooning in highway systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 9563–9578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Fu, M. Stochastic LQ optimal control with initial and terminal constraints. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 69, 6261–6268. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.Y.; Mu, H.R.; Fu, S.J.; Han, H.G. Data-driven model predictive control for unknown nonlinear NCSs with stochastic sampling intervals and successive packet dropouts. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 2899–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhang, H. Solution to discrete-time linear FBSDEs with application to stochastic control problem. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 6602–6607. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Voos, H.; Darouach, M.; Hua, C. An application of linear algebra theory in networked control systems: Stochastic cyber-attacks detection approach. IMA J. Math. Control Inf. 2016, 33, 1081–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, A.; Kishida, M. Instabilizability conditions for continuous-time stochastic systems under control input constraints. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2021, 6, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Hokayem, P.; Lygeros, J. Stochastic receding horizon control with bounded control inputs: A vector space approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 56, 2704–2710. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Dang, X.K.; Do, V.D.; Corchado, J.M.; Truong, H.N. Robust adaptive fuzzy-free fault-tolerant path planning control for a semi-submersible platform dynamic positioning system with actuator constraints. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 12701–12715. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xie, X.; Zhou, C. Locally expanded constraint-boundary-based adaptive composite control of a constrained nonlinear system with time-varying actuator fault. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 4121–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Diao, S.; Su, S.F.; Sun, Z.Y. Fixed-time adaptive neural network control for nonlinear systems with input saturation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Song, M.; Huang, B.; Huang, P. Adaptive tracking control for tethered aircraft systems with actuator nonlinearities and output constraints. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 3582–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, G. Adaptive fixed-time sliding mode control of vehicular platoons with asymmetric actuator saturation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8409–8423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Zhang, P. Asymptotic stabilization of USVs with actuator dead-zones and yaw constraints based on fixed-time disturbance observer. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 69, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gao, N.; Liu, D.; Li, J.; Lewis, F.L. Recent progress in reinforcement learning and adaptive dynamic programming for advanced control applications. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 11, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y. Value iteration-based distributed adaptive dynamic programming for multi-player differential game with incomplete information. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2025, 12, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Yang, Z.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Online adaptive dynamic programming for optimal self-learning control of VTOL aircraft systems with disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 21, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Chen, W.; Tan, X.; Xiao, J.; Dong, Q. Observer-based optimal Backstepping security control for nonlinear systems using reinforcement learning strategy. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 7011–7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Luo, Y. Neurodynamic programming and tracking control for nonlinear stochastic systems by PI algorithm. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2892–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, M.; Lewis, F.L.; Zheng, M. Compensator-based self-learning: Optimal operational control for two-time-scale systems with input constraints. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 9465–9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Gao, W.; Jiang, X.; Su, C.; Li, P. Two-dimensional model-free Q-learning-based output feedback fault-tolerant control for batch processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 182, 108583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Jiang, Z.P. Reinforcement learning for adaptive optimal stationary control of linear stochastic systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2022, 68, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Peng, Y. Model-free tracking control for linear stochastic systems via integral reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 10835–10844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qu, Q.; Xiao, G.; Cui, Y. Optimal guaranteed cost sliding mode control for constrained-input nonlinear systems with matched and unmatched disturbances. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 2112–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jiang, Z.P. Event-based control of nonlinear systems with partial state and output feedback. Automatica 2015, 53, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Han, L.; Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Dai, X.; Wang, F.Y. Event-triggered deep reinforcement learning using parallel control: A case study in autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 2821–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhu, Q. Event-triggered optimized control for nonlinear delayed stochastic systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2021, 68, 3808–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liang, C.; Zhu, Q. Adaptive fuzzy event-triggered optimized consensus control for delayed unknown stochastic nonlinear multi-agent systems using simplified ADP. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 11780–11793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zhang, W.; Luo, B.; Liu, D. Integral reinforcement learning-based dynamic event-triggered nonzero-sum games of USVs. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 1706–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Z.g.; Zhang, H.; Tong, X.; Yan, Y. Mixed H2/H∞ control with dynamic event-triggered mechanism for partially unknown nonlinear stochastic systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 20, 1934–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.; Ma, D.; Wang, R.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H. Dynamic event-triggered-based integral reinforcement learning algorithm for frequency control of microgrid with stochastic uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 69, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Li, Y.X.; Tong, S. Dynamic event-triggered reinforcement learning control of stochastic nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 2917–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wan, Y.; Lewis, F.L. Adaptive optimal decision in multi-agent random switching systems. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2019, 4, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Qin, Z.; Hong, Y.; Jiang, Z.P. Distributed optimization of nonlinear multiagent systems: A small-gain approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2021, 67, 676–691. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Ming, Z. Event-triggered guarantee cost control for partially unknown stochastic systems via explorized integral reinforcement learning strategy. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 7830–7844. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R.; Ma, J.; Su, P.; Dong, Y.; Cheng, J. Monte-Carlo integration models for multiple scattering based optical wireless communication. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2019, 68, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Cao, R.; Sun, Z. A multilevel Monte Carlo method for performing time-variant reliability analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 31773–31781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wan, Y.; Mills, K.; Filliben, J.J.; Lewis, F.L. A scalable sampling method to high-dimensional uncertainties for optimal and reinforcement learning-based controls. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2017, 1, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Wan, Y.; Roy, S.; Taylor, C.; Wanke, C.; Ramamurthy, D.; Xie, J. Multivariate probabilistic collocation method for effective uncertainty evaluation with application to air traffic flow management. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2014, 44, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Wan, Y.; Lewis, F.L.; Lopez, V.G. Adaptive optimal control for stochastic multiplayer differential games using on-policy and off-policy reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 5522–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z. Global asymptotic stability analysis for autonomous optimization. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2025, 70, 6953–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Li, H.; Qin, Z.; Wang, Z. Gradient-free cooperative source-seeking of quadrotor under disturbances and communication constraints. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 1969–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Tang, Y.; Zhong, S.; Yin, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, W. Nonfragile asynchronous control for uncertain chaotic lurie network systems with bernoulli stochastic process. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2018, 28, 1693–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, H. Adaptive dynamic programming for H∞ tracking design of uncertain nonlinear systems with disturbances and input constraints. Int. J. Adapt. Control Signal Process. 2017, 31, 1567–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cui, X.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, H. Finite-horizon H∞ tracking control for unknown nonlinear systems with saturating actuators. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 29, 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, A.; Jagannathan, S. Stochastic optimal regulation of nonlinear networked control systems by using event-driven adaptive dynamic programming. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasini, S.; Naghibi Sitani, M.B.; Kirampor, A. Reinforcement learning and neural networks for multi-agent nonzero-sum games of nonlinear constrained-input systems. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2016, 7, 967–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).