Genome-Wide Association Reveals Signalling-Linked Infection Tolerance in Hibernating Bats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

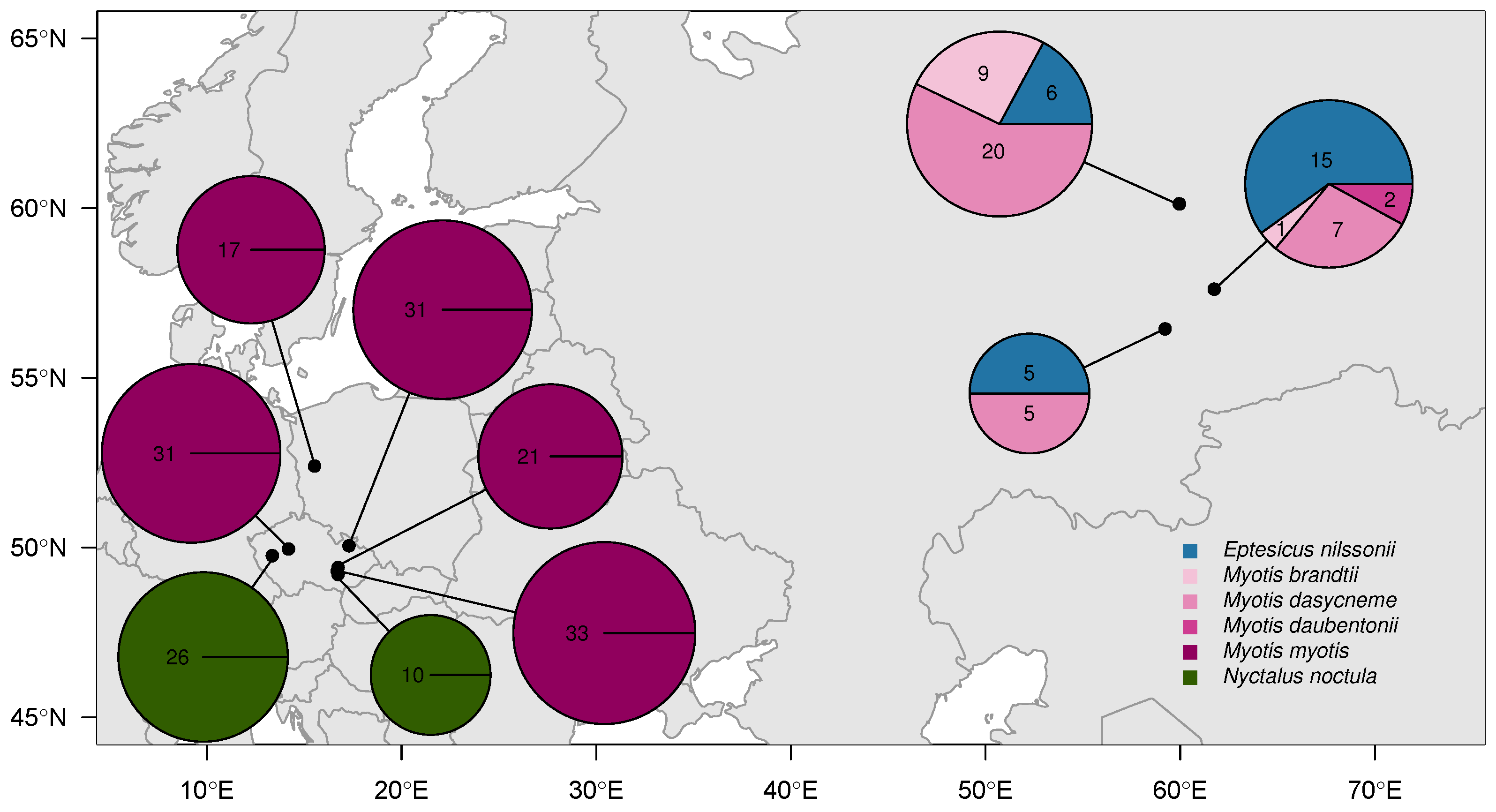

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Haematological Parameters

2.3. Identification and Quantification of Pathogens

2.4. DNA Purification and Library Preparation

2.5. Sequencing Data Processing

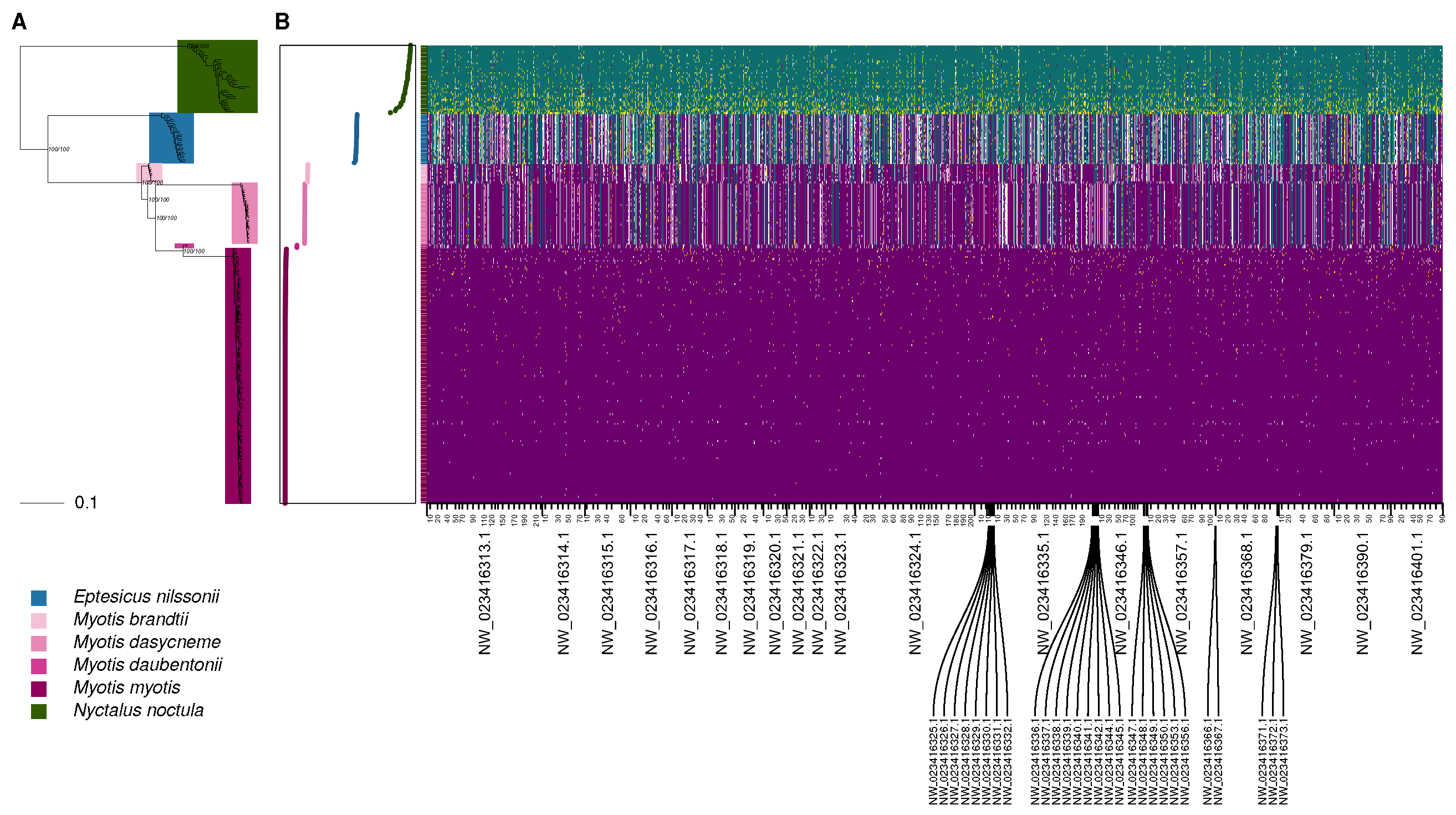

2.6. Reconstruction of Relatedness Structure

2.7. Genome-Wide Association Study

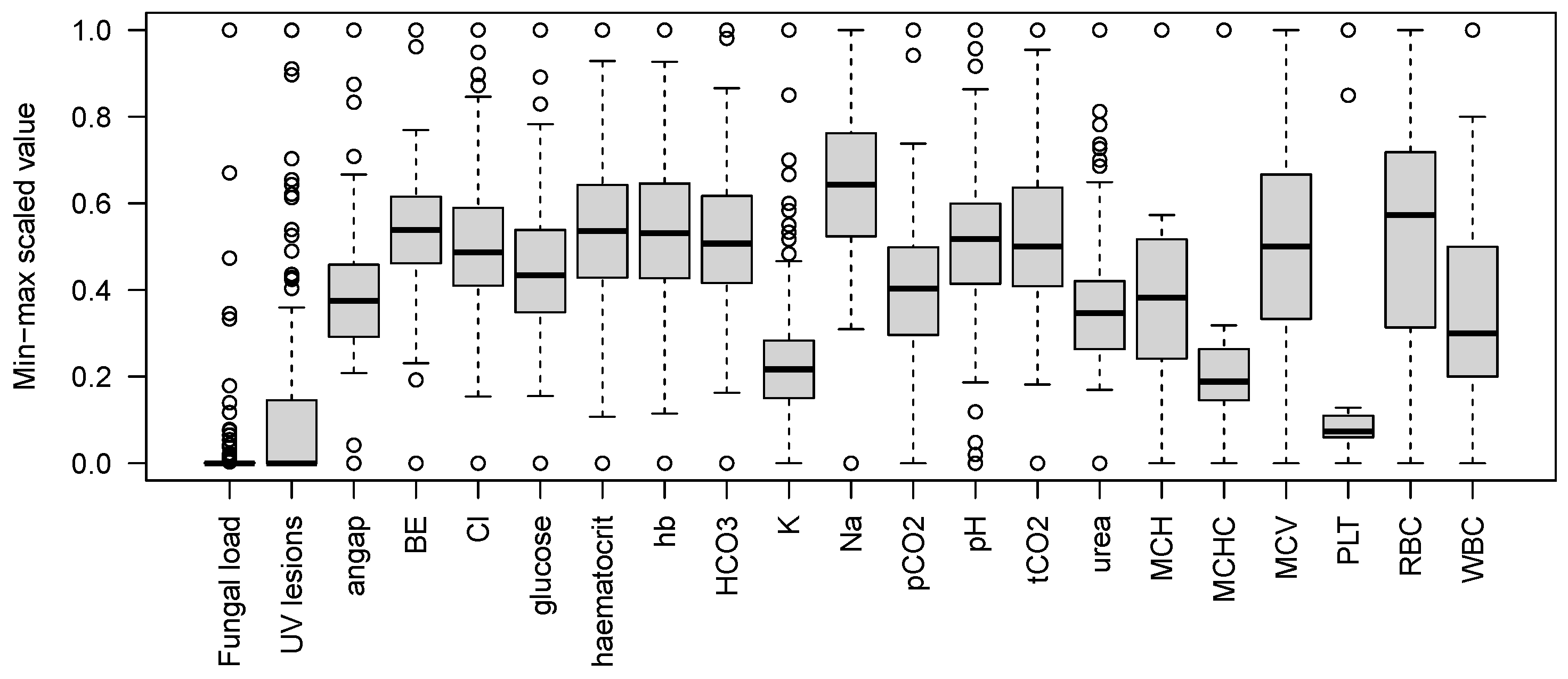

| Variable | n | Minimum | Maximum | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection markers | |||||

| Trypanosoma | 107 (19) | 0 | 1 | uninfected/infected | |

| Bartonella | 216 (200) | 0 | 1 | uninfected/infected | |

| Fungal load | 210 (124) | 0 | 0.24 | log10(1 + ng cm−2) | |

| UV lesions | 85 (33) | 0 | 0.90 | log10(1 + no. cm−2) | |

| Haematological parameters | |||||

| Trombocyte count (PLT) | 16 | 244 | 2952 | 109 L−1 | |

| Mean corpuscular haemoglobin in RBC (MCH) | 16 | 64.8 | 100.4 | pg | |

| MCH concentration (MCHC) | 15 | 1364 | 3124 | g dL−1 | |

| Mean corpuscular volume of RBC (MCV) | 16 | 168 | 192 | fl | |

| White blood cell count (WBC) | 16 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 109 L−1 | |

| Red blood cell count (RBC) | 16 | 7.08 | 11.48 | 1012 L−1 | |

| Biochemical parameters | |||||

| Sodium (Na+) | 92 | 127 | 169 | mmol L−1 | |

| Potassium (K+) | 91 | 2.8 | 8.8 | mmol L−1 | |

| Chloride (Cl−) | 89 | 97 | 136 | mmol L−1 | |

| Total CO2 (tCO2) | 91 | 14 | 36 | mmol L−1 | |

| Urea | 90 | 1 | 50 | mmol L−1 | |

| Blood pH | 91 | 7.066 | 7.462 | – | |

| Partial CO2 pressure (pCO2) | 91 | 3.63 | 12.02 | kPa | |

| Bicarbonate (HCO3) | 91 | 13.1 | 34 | mmol L−1 | |

| Base excess (BE) | 91 | –17 | 9 | mmol L−1 | |

| Anion gap (angap) | 87 | 8 | 32 | mmol L−1 | |

| Haemoglobin (hb) | 91 | 122 | 218 | g L−1 | |

| Glucose | 91 | 1.3 | 14.2 | mmol L−1 | |

| Haematocrit | 91 | 36 | 64 | % | |

3. Results

3.1. Variation in Bat Health Parameters

3.2. Reproducibility of ddRAD Libraries

3.3. Genomic Divergence

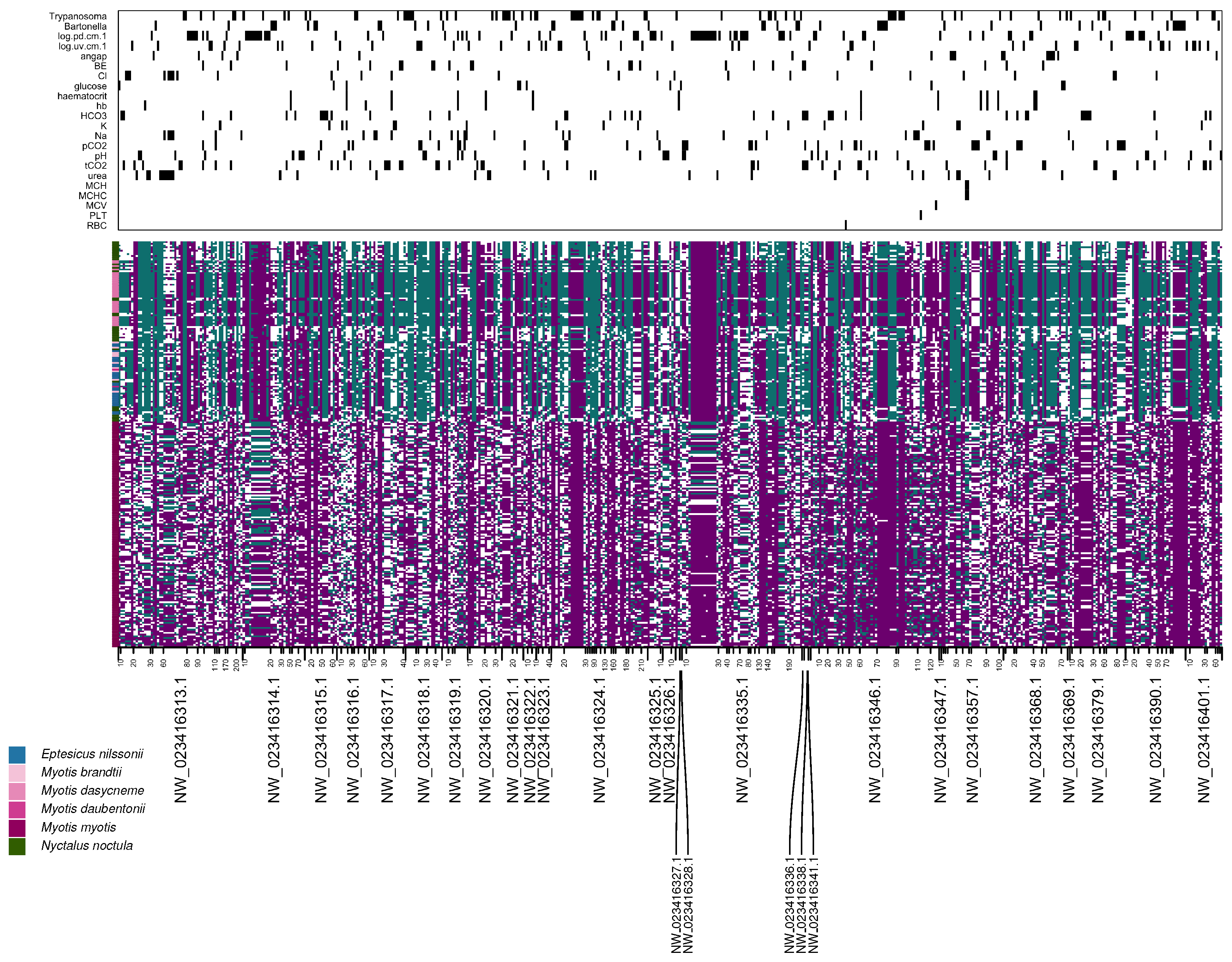

3.4. Associations Between Genomic Variation and Health-Related Variables

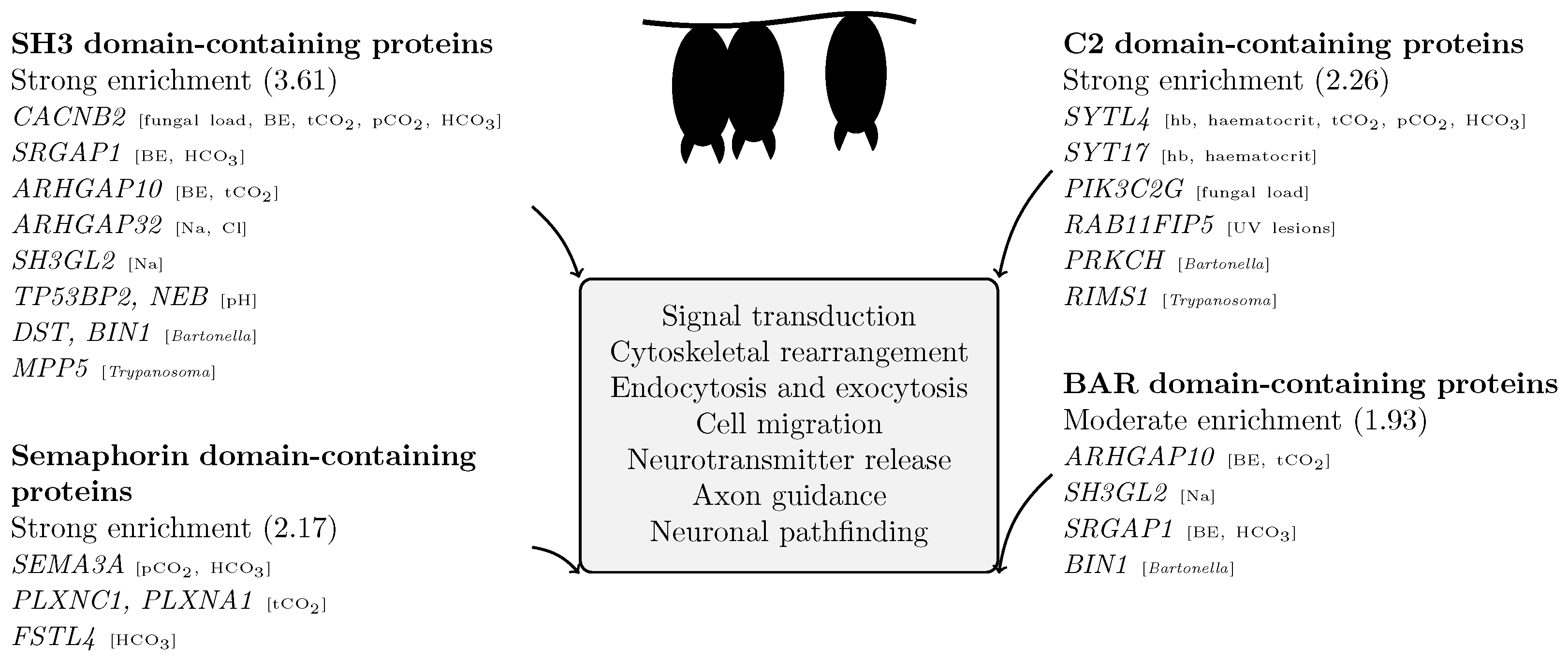

4. Discussion

4.1. Infection Tolerance and Physiological Trade-Offs in Hibernating Bats

4.2. Functional Convergence of Associated Loci

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| angap | Anion gap |

| BE | Base excess |

| DAVID | Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery |

| hb | Haemoglobin |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate |

| MCH | Mean corpuscular haemoglobin in RBC |

| MCHC | MCH concentration |

| MCV | Mean corpuscular volume |

| pCO2 | Partial CO2 pressure |

| PLT | Trombocyte count |

| RBC | Red blood cells |

| SNV | Single nucleotide variant |

| SRA | Short-read archive |

| tCO2 | Total CO2 |

| UV | Ultra-violet |

| WBC | White blood cells |

References

- Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A.; Kennedy, B.K. The World Goes Bats: Living Longer and Tolerating Viruses. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, A.T.; Ahn, M.; Goh, G.; Anderson, D.E.; Wang, L.F. Lessons from the host defences of bats, a unique viral reservoir. Nature 2021, 589, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, G.; Balkema-Buschmann, A.; Dorhoi, A. Disease tolerance as immune defense strategy in bats: One size fits all? PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luis, A.D.; Hayman, D.T.S.; O’Shea, T.J.; Cryan, P.M.; Gilbert, A.T.; Pulliam, J.R.C.; Mills, J.N.; Timonin, M.E.; Willis, C.K.R.; Cunningham, A.A.; et al. A comparison of bats and rodents as reservoirs of zoonotic viruses: Are bats special? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guth, S.; Mollentze, N.; Renault, K.; Streicker, D.G.; Visher, E.; Boots, M.; Brook, C.E. Bats host the most virulent–but not the most dangerous–zoonotic viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113628119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, T.; Cryan, P.; Cunningham, A.; Fooks, A.; Hayman, D.T.S.; Luis, A.; Peel, A.; Plowright, R.; Wood, J.L.N. Bat Flight and Zoonotic Viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 20, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, C.M.; Donaldson, M.E.; Bandouchova, H.; Breit, A.M.; Dorville, N.A.; Dzal, Y.A.; Kovacova, V.; Kunkel, E.L.; Martínková, N.; Norquay, K.J.; et al. Transcriptional host-pathogen responses of Pseudogymnoascus destructans and three species of bats with white-nose syndrome. Virulence 2020, 11, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.; Kearney, T.; Seamark, E.C.J.; Paweska, J.T.; Markotter, W. Synchronized shift of oral, faecal and urinary microbiotas in bats and natural infection dynamics during seasonal reproduction. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Wang, Y.; Lü, L.; Jiang, C.; Ahmad, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, D. Bats and birds as viral reservoirs: A physiological and ecological perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, H.V.; Andrews, M.T.; Martin, S.L. Mammalian hibernation: Cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 1153–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouma, H.R.; Carey, H.V.; Kroese, F.G.M. Hibernation: The immune system at rest? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 88, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, S.S.; Lovett, S.P.; Koroleva, G.; Guito, J.C.; Arnold, C.E.; Nagle, E.R.; Kulcsar, K.; Lee, A.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Hume, A.J.; et al. The Egyptian Rousette Genome Reveals Unexpected Features of Bat Antiviral Immunity. Cell 2018, 173, 1098–1110.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritze, M.; Costantini, D.; Fickel, J.; Wehner, D.; Czirják, G.Á.; Voigt, C.C. Immune response of hibernating European bats to a fungal challenge. Biol. Open 2019, 8, bio046078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting-Fawcett, F.; Field, K.A.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Blomberg, A.S.; Lilley, T.M. Heterothermy and antifungal responses in bats. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021, 62, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínková, N.; Pikula, J.; Zukal, J.; Kovacova, V.; Bandouchova, H.; Bartonička, T.; Botvinkin, A.D.; Brichta, J.; Dundarova, H.; Kokurewicz, T.; et al. Hibernation temperature-dependent Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection intensity in Palearctic bats. Virulence 2018, 9, 1734–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forney, R.; Rios-Sotelo, G.; Lindauer, A.; Willis, C.K.R.; Voyles, J. Temperature shifts associated with bat arousals during hibernation inhibit the growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazim, M.; Perrot, J.; Varet, H.; Bourhy, H.; Lannoy, J.; Pikula, J.; Seidlová, V.; Dacheux, L.; Martínková, N. Transcriptomic responses of bat cells to Europea bat lyssavirus 1 infection under conditions simulating euthermia and hibernation. BMC Immunol. 2023, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopes, E.R.; Broome, A.; Walsh, K.; Bennie, J.J.; McDonald, R.A. Conservation implications of hibernation in mammals. Mammal Rev. 2024, 54, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.F.; Reichard, J.D.; Coleman, J.T.H.; Blackwood, J.C.; Verant, M.L.; Segers, J.L.; Lorch, J.M.; Paul White, J.; Moore, M.S.; Russell, A.L.; et al. Identifying research needs to inform white-nose syndrome management decisions. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínková, N.; Baird, S.J.E.; Káňa, V.; Zima, J. Bat population recoveries give insight into clustering strategies during hibernation. Front. Zool. 2020, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, Q.M.R.; Willis, C.K.R. Personality affects dynamics of an experimental pathogen in little brown bats. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zukal, J.; Bandouchova, H.; Brichta, J.; Cmokova, A.; Jaron, K.S.; Kolarik, M.; Kovacova, V.; Kubátová, A.; Nováková, A.; Orlov, O.; et al. White-nose syndrome without borders: Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection tolerated in Europe and Palearctic Asia but not in North America. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting-Fawcett, F.; Blomberg, A.S.; Troitsky, T.; Meierhofer, M.B.; Field, K.A.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Lilley, T.M. A Palearctic view of a bat fungal disease. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e14265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meteyer, C.U.; Barber, D.; Mandl, J.N. Pathology in euthermic bats with white nose syndrome suggests a natural manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Virulence 2012, 3, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, L.; Turner, J.M.; Bollinger, T.K.; Misra, V.; Cryan, P.M.; Blehert, D.S.; Wibbelt, G.; Willis, C.K.R. Pathophysiology of white-nose syndrome in bats: A mechanistic model linking wing damage to mortality. Biol. Lett. 2013, 9, 20130177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flieger, M.; Bandouchova, H.; Cerny, J.; Chudíčková, M.; Kolarik, M.; Kovacova, V.; Martínková, N.; Novák, P.; Šebesta, O.; Stodůlková, E.; et al. Vitamin B2 as a virulence factor in Pseudogymnoascus destructans skin infection. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, D.; Huang, Z.; Pippel, M.; Hughes, G.M.; Lavrichenko, K.; Devanna, P.; Winkler, S.; Jermiin, L.S.; Skirmuntt, E.C.; Katzourakis, A.; et al. Six reference-quality genomes reveal evolution of bat adaptations. Nature 2020, 583, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, R.; Schmid, D.W.; Wasimuddin; Brändel, S.D.; Rasche, A.; Corman, V.M.; Drosten, C.; Tschapka, M.; Sommer, S. Interaction between MHC diversity and constitution, gut microbiota and Astrovirus infections in a neotropical bat. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 3342–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baid, K.; Irving, A.T.; Jouvenet, N.; Banerjee, A. The translational potential of studying bat immunity. Trends Immunol. 2024, 45, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazim, M.; Horáček, I.; Jakešová, L.; Luermann, K.; Moravec, J.C.; Morgan, S.; Pikula, J.; Sosík, P.; Vavrušová, Z.; Zahradníková, A., Jr.; et al. Natural selection in bats with historical exposure to white-nose syndrome. BMC Zool. 2018, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Jain, D.; Chaudhary, P.; Quintela-Tizon, R.M.; Banerjee, A.; Kesavardhana, S. Bat adaptations in inflammation and cell death regulation contribute to viral tolerance. mBio 2025, 16, e03204-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandouchova, H.; Bartonička, T.; Berkova, H.; Brichta, J.; Kokurewicz, T.; Kovacova, V.; Linhart, P.; Piacek, V.; Pikula, J.; Zahradníková, A.; et al. Alterations in the health of hibernating bats under pathogen pressure. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandouchova, H.; Zukal, J.; Linhart, P.; Berkova, H.; Brichta, J.; Kovacova, V.; Kubickova, A.; Abdelsalam, E.E.E.; Bartonička, T.; Zajíčková, R.; et al. Low seasonal variation in greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis) blood parameters. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorn, S.; Pfister, K.; Reulen, H.; Mahling, M.; Silaghi, C. Occurrence of Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Bavarian public parks, Germany. Parasites Vectors 2011, 4, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhart, P.; Bandouchova, H.; Zukal, J.; Votýpka, J.; Baláž, V.; Heger, T.; Kalocsanyiova, V.; Kubickova, A.; Nemcova, M.; Sedlackova, J.; et al. Blood Parasites and Health Status of Hibernating and Non-Hibernating Noctule Bats (Nyctalus noctula). Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piálek, L.; Burress, E.; Dragová, K.; Almirón, A.; Casciotta, J.; Říčan, O. Phylogenomics of pike cichlids (Cichlidae: Crenicichla) of the C. mandelburgeri species complex: Rapid ecological speciation in the Iguazú River and high endemism in the Middle Paraná basin. Hydrobiologia 2019, 832, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchen, J.M.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Bassham, S.; Amores, A.; Cresko, W.A. Stacks: An analysis tool set for population genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 3124–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, S.J.; Petružela, J.; Jaroň, I.; Škrabánek, P.; Martínková, N. Genome polarisation for detecting barriers to geneflow. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoš, F.; Baird, S.J.; Harazim, M.; Martínková, N. Eroding species barriers: Hybridising canids remain distinct around centromeres. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínková, N. Genome Polarisation with Diemr. Bookdown Online Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://nmartinkova.github.io/genome-polarisation/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Collins, C.; Didelot, X. A phylogenetic method to perform genome-wide association studies in microbes that accounts for population structure and recombination. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, B.J.; Grünwald, N.J. VCFR: A package to manipulate and visualize variant call format data in R. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andras, J.P.; Fields, P.D.; Du Pasquier, L.; Fredericksen, M.; Ebert, D. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies a Genetic Basis of Infectivity in a Model Bacterial Pathogen. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 3439–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, D.J.; Bergner, L.M.; Bentz, A.B.; Orton, R.J.; Altizer, S.; Streicker, D.G. Genetic diversity, infection prevalence, and possible transmission routes of Bartonella spp. in vampire bats. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Santos, A.; Lock, L.R.; Allira, M.; Dyer, K.E.; Dunsmore, A.; Tu, W.; Volokhov, D.V.; Herrera, C.; Lei, G.S.; Relich, R.F.; et al. Serum proteomics reveals a tolerant immune phenotype across multiple pathogen taxa in wild vampire bats. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1281732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austen, J.M.; Barbosa, A.D. Diversity and Epidemiology of Bat Trypanosomes: A One Health Perspective. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A.; Clément, L.; Szentiványi, T.; Théou, P.; López-Baucells, A.; Bonny, L.; Scaravelli, D.; Glaizot, O.; Christe, P. Bat phylogeny and geographic location, rather than bat individual characteristics, explains the pattern of trypanosome infection in Europe. Int. J. Parasitol. 2025, 55, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, C.D.; Bai, Y.; Webb, C.T.; Kosoy, M.Y. Bats are key hosts in the radiation of mammal-associated Bartonella bacteria. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 89, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.J.; Gao, Q.; Guo, B.Z.; Xiao, X.; Han, H.J. Genomic characterization of eight novel Bartonella species from bats and ectoparasites reveals phylogenetic diversity and host adaptation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davy, C.M.; Donaldson, M.E.; Willis, C.K.R.; Saville, B.J.; McGuire, L.P.; Mayberry, H.; Wilcox, A.; Wibbelt, G.; Misra, V.; Bollinger, T.; et al. The other white-nose syndrome transcriptome: Tolerant and susceptible hosts respond differently to the pathogen Pseudogymnoascus destructans. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 7161–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting-Fawcett, F.; Field, K.A.; Bartonička, T.; Laine, V.N.; Pikula, J.; Repke, M.E.; Talmage, S.; Turner, G.; Zukal, J.; Paterson, S.; et al. Bat species tolerant and susceptible to fungal infection show transcriptomic differences in late hibernation and healing. J. Exp. Biol. 2026, 229, jeb250903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazim, M.; Piálek, L.; Pikula, J.; Seidlová, V.; Zukal, J.; Bachorec, E.; Bartonička, T.; Kokurewicz, T.; Martínková, N. Associating physiological functions with genomic variability in hibernating bats. Evol. Ecol. 2021, 35, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, A.; Martin, S.L.; Jain, S.; Keys, D.; Edelstein, C.L. Renal adaptation during hibernation. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2013, 305, F1521–F1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczak, J.M.; Jackson, D.C. Acid-base state and intermittent breathing in the torpid bat, Eptesicus fuscus. Respir. Physiol. 1992, 88, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lack, J.B.; Van Den Bussche, R.A. Identifying the confounding factors in resolving phylogenetic relationships in Vespertilionidae. J. Mammal. 2010, 91, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruedi, M.; Castella, V. Genetic consequences of the ice ages on nurseries of the bat Myotis Myotis: A mitochondrial and nuclear survey. Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.W.; Dirksen, R.; Nikulina, E.A.; Baagøe, H.J.; Petersons, G.; Estók, P.; Orlov, O.L.; Orlova, M.V.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Göttsche, M.; et al. Conservation genetics of the pond bat (Myotis dasycneme) with special focus on the populations in northwestern Germany and in Jutland, Denmark. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 5292–5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, E.; Mayer, F. A population genetic analysis of migration: The case of the noctule bat (Nyctalus noctula). Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, A.E.; Burbrink, F.T.; Segall, M.; Meza, M.; Munegowda, C.; Webala, P.W.; Patterson, B.D.; Thong, V.D.; Ruedi, M.; Hiller, M.; et al. Distinct Genes with Similar Functions Underlie Convergent Evolution in Myotis Bat Ecomorphs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geli, M.I.; Lombardi, R.; Schmelzl, B.; Riezman, H. An intact SH3 domain is required for myosin I-induced actin polymerization. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4281–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualmann, B.; Koch, D.; Kessels, M.M. Let’s go bananas: Revisiting the endocytic BAR code. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3501–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bossé, Y.; Paré, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Harazim, M.; Piálek, L.; Bandouchova, H.; Pikula, J.; Seidlová, V.; Zukal, J.; Němcová, M.; Heger, T.; Linhart, P.; Piaček, V.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Reveals Signalling-Linked Infection Tolerance in Hibernating Bats. Pathogens 2026, 15, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15020149

Harazim M, Piálek L, Bandouchova H, Pikula J, Seidlová V, Zukal J, Němcová M, Heger T, Linhart P, Piaček V, et al. Genome-Wide Association Reveals Signalling-Linked Infection Tolerance in Hibernating Bats. Pathogens. 2026; 15(2):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15020149

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarazim, Markéta, Lubomír Piálek, Hana Bandouchova, Jiri Pikula, Veronika Seidlová, Jan Zukal, Monika Němcová, Tomas Heger, Petr Linhart, Vladimír Piaček, and et al. 2026. "Genome-Wide Association Reveals Signalling-Linked Infection Tolerance in Hibernating Bats" Pathogens 15, no. 2: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15020149

APA StyleHarazim, M., Piálek, L., Bandouchova, H., Pikula, J., Seidlová, V., Zukal, J., Němcová, M., Heger, T., Linhart, P., Piaček, V., Kokurewicz, T., Orlov, O. L., Zahradníková, A., Jr., & Martínková, N. (2026). Genome-Wide Association Reveals Signalling-Linked Infection Tolerance in Hibernating Bats. Pathogens, 15(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15020149