Causal Relationships Between the Oral Microbiome and Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oral Microbiome Sample

2.2. Autoimmune Disease Samples

2.3. Selection of Instrumental Variables (IVs)

- Relevance: Genetic variants serving as IVs must exhibit strong associations with exposure.

- Independence: IVs must be independent of potential confounders.

- Exclusion restriction: IVs should affect the outcome exclusively through the target exposure, with no direct or indirect pleiotropic pathways.

- Genome-wide significance: Retained variants with p < 1 × 10−5 from exposure GWAS.

- Instrument strength: Excluded variants with F-statistic ≤ 10 to mitigate weak instrument bias.

- Minor allele frequency (MAF): Removed SNPs with MAF < 1%.

- Linkage disequilibrium (LD) pruning: Independent SNPs were selected by performing LD-based clumping through the IEUGWAS platform, using a genomic window of 10,000 kb and an r2 threshold of 0.001.

- Strand ambiguity: Excluded palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies (0.42 < MAF < 0.58).

- Allele harmonization: Effect alleles were standardized across exposure and outcome datasets to ensure consistent directional effects.

2.4. MR Analysis

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

3. Results

3.1. IVs Selection

3.2. Causal Effects of Oral Microbiota on Six Types of ADs

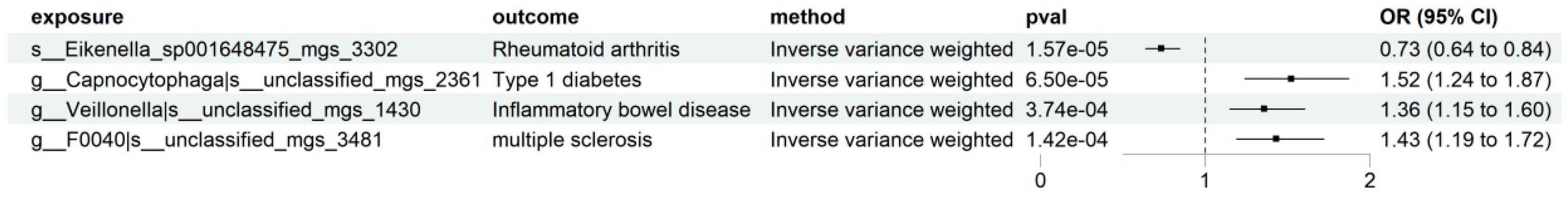

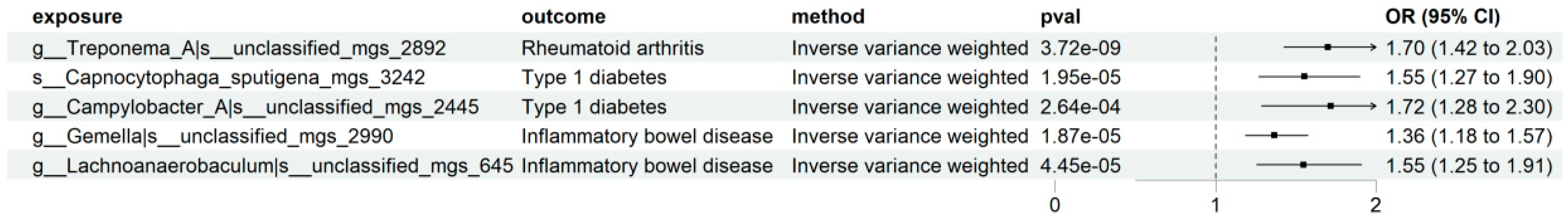

3.3. Rheumatoid Arthritis

3.4. Type 1 Diabetes

3.5. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

3.6. Multiple Sclerosis

3.7. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Sjögren’s Syndrome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guan, S.-Y.; Zheng, J.-X.; Feng, X.-Y.; Zhang, S.-X.; Xu, S.-Z.; Wang, P.; Pan, H.-F. Global Burden Due to Modifiable Risk Factors for Autoimmune Diseases, 1990–2021: Temporal Trends and Socio-Demographic Inequalities. Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, F.W. The Increasing Prevalence of Autoimmunity and Autoimmune Diseases: An Urgent Call to Action for Improved Understanding, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 80, 102266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Evolving Understanding of Autoimmune Mechanisms and New Therapeutic Strategies of Autoimmune Disorders. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, W.E.; Greiling, T.M.; Kriegel, M.A. Host-Microbiota Interactions in Immune-Mediated Diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekaran, J.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.L.; Mark Welch, J.L.; Kauffman, K.M.; McLean, J.S.; He, X. The Oral Microbiome: Diversity, Biogeography and Human Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Do, T.; Mankia, K.; Meade, J.; Hunt, L.; Clerehugh, V.; Speirs, A.; Tugnait, A.; Emery, P.; Devine, D. Dysbiosis in the Oral Microbiomes of Anti-CCP Positive Individuals at Risk of Developing Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Febles, J.; Sanz, M. Periodontitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Have We Learned about Their Connection and Their Treatment? Periodontol. 2000 2021, 87, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-Z.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Guo, B.; Chen, W.-J.; Tao, J.-H.; Cao, N.-W.; Chu, X.-J.; Meng, X. Dysbiosis of Oral Microbiota Is Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 113, 104708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiely, F.; Shea, N.O.; Murphy, E.; Eustace, J. Registry-Based Randomised Controlled Trials: Conduct, Advantages and Challenges—A Systematic Review. Trials 2024, 25, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, R.; Kim, S.J. Inferring Causality from Observational Studies: The Role of Instrumental Variable Analysis. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.D.; Ebrahim, S. “Mendelian Randomization”: Can Genetic Epidemiology Contribute to Understanding Environmental Determinants of Disease? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 32, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Ren, F.; Wang, X. Association between Oral Microbiome and Seven Types of Cancers in East Asian Population: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1327893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Ren, F.; Shang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Association between Oral Microbiome and Breast Cancer in the East Asian Population: A Mendelian Randomization and Case–Control Study. Thorac. Cancer 2024, 15, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhou, H. A Causal Association between Esophageal Cancer and the Oral Microbiome: A Mendelian Randomization Study Based on an Asian Population. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1420625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Shui, M.; Luo, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, C.; Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Tang, J.; et al. Revealing the Association between East Asian Oral Microbiome and Colorectal Cancer through Mendelian Randomization and Multi-Omics Analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1452392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Peng, Q.; Ren, Z.; Xu, X.; Jiang, X.; Yang, W.; Han, Y.; Oyang, L.; Lin, J.; Peng, M.; et al. Causal Association between Oral Microbiota and Oral Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wen, F.; Qiu, H.; Li, J. Genetic Evidence from Mendelian Randomization Strengthens the Causality between Oral Microbiome and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Medicine 2025, 104, e43347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, N.; Lyu, W.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z. Association between Oral Microbiome and Five Types of Respiratory Infections: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study in East Asian Population. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1392473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, F.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Peng, L.; Yue, C. Causal Relationship between Oral Microbiota and Epilepsy Risk: Evidence from Mendelian Randomization Analysis in East Asians. Epilepsia Open 2024, 9, 2419–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tong, X.; Zhu, J.; Tian, L.; Jie, Z.; Zou, Y.; Lin, X.; Liang, H.; Li, W.; Ju, Y.; et al. Metagenome-Genome-Wide Association Studies Reveal Human Genetic Impact on the Oral Microbiome. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, Y.; Wu, D.; Trynka, G.; Raj, T.; Terao, C.; Ikari, K.; Kochi, Y.; Ohmura, K.; Suzuki, A.; Yoshida, S.; et al. Genetics of Rheumatoid Arthritis Contributes to Biology and Drug Discovery. Nature 2014, 506, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, J.; Geusz, R.J.; Okino, M.-L.; Han, J.Y.; Miller, M.; Melton, R.; Beebe, E.; Benaglio, P.; Huang, S.; Korgaonkar, K.; et al. Interpreting Type 1 Diabetes Risk with Genetics and Single-Cell Epigenomics. Nature 2021, 594, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lange, K.M.; Moutsianas, L.; Lee, J.C.; Lamb, C.A.; Luo, Y.; Kennedy, N.A.; Jostins, L.; Rice, D.L.; Gutierrez-Achury, J.; Ji, S.-G.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Implicates Immune Activation of Multiple Integrin Genes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Multiple Sclerosis Genomic Map Implicates Peripheral Immune Cells and Microglia in Susceptibility. Science 2019, 365, eaav7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.; Davey Smith, G.; Davies, N.M.; Dudbridge, F.; Gill, D.; Glymour, M.M.; Hartwig, F.P.; Kutalik, Z.; Holmes, M.V.; Minelli, C.; et al. Guidelines for Performing Mendelian Randomization Investigations: Update for Summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res. 2023, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.; Spiller, W.; Bowden, J. Testing and Correcting for Weak and Pleiotropic Instruments in Two-Sample Multivariable Mendelian Randomization. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 5434–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium; Auton, A.; Brooks, L.D.; Durbin, R.M.; Garrison, E.P.; Kang, H.M.; Korbel, J.O.; Marchini, J.L.; McCarthy, S.; McVean, G.A.; et al. A Global Reference for Human Genetic Variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.; Foley, C.N.; Zuber, V. Inferring Causal Relationships Between Risk Factors and Outcomes from Genome-Wide Association Study Data. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2018, 19, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, S.; Thompson, S.G. Interpreting Findings from Mendelian Randomization Using the MR-Egger Method. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Haycock, P.C.; Burgess, S. Consistent Estimation in Mendelian Randomization with Some Invalid Instruments Using a Weighted Median Estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 2016, 40, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemani, G.; Zheng, J.; Elsworth, B.; Wade, K.H.; Haberland, V.; Baird, D.; Laurin, C.; Burgess, S.; Bowden, J.; Langdon, R.; et al. The MR-Base Platform Supports Systematic Causal Inference across the Human Phenome. Elife 2018, 7, e34408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavorska, O.O.; Burgess, S. MendelianRandomization: An R Package for Performing Mendelian Randomization Analyses Using Summarized Data. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1734–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbanck, M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Neale, B.; Do, R. Detection of Widespread Horizontal Pleiotropy in Causal Relationships Inferred from Mendelian Randomization between Complex Traits and Diseases. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Hu, J.; Zhi, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Peng, X. P0213 Salivary Veillonella Parvula from Crohn’s Disease Patients Exacerbates Intestinal Inflammation. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2025, 19, i621–i622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J.; Del Greco, M.F.; Minelli, C.; Zhao, Q.; Lawlor, D.A.; Sheehan, N.A.; Thompson, J.; Davey Smith, G. Improving the Accuracy of Two-Sample Summary-Data Mendelian Randomization: Moving beyond the NOME Assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caselli, E.; Fabbri, C.; D’Accolti, M.; Soffritti, I.; Bassi, C.; Mazzacane, S.; Franchi, M. Defining the Oral Microbiome by Whole-Genome Sequencing and Resistome Analysis: The Complexity of the Healthy Picture. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Romanò, C.L.; Goswami, K.; Villafañe, J.H.; Mattina, R.; Parvizi, J. Oral-Gut Microbiota and Arthritis: Is There an Evidence-Based Axis? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikenella corrodens in a Patient with Septic Arthritis: A Case Report—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40270686/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Louca, S.; Doebeli, M. Transient Dynamics of Competitive Exclusion in Microbial Communities. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.C.; Ebersole, J.L. Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: The “Red Complex”, a Prototype Polybacterial Pathogenic Consortium in Periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2005, 38, 72–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchese, A. Periodontal Bacteria and the Rheumatoid Arthritis-Related Antigen RA-A47: The Cross-Reactivity Potential. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.S.; Solon, I.G.; Branco, L.G.S. Impact of Periodontal Lipopolysaccharides on Systemic Health: Mechanisms, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 40, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, C.; Ceccarelli, F.; Matteo, S.; Di Carlo, G.; Bogdanos, D.P.; Lucchetti, R.; Pilloni, A.; Valesini, G.; Polimeni, A.; Conti, F. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2019, 31, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, C.; Cîrciumaru, A.; Mathsson-Alm, L.; Westerlind, H.; Dehara, M.; Kisten, Y.; Potempa, B.; Potempa, J.; Hensvold, A.; Lundberg, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis Associates with the Presence of Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies, but Not with the Onset of Arthritis: Studies in an at-Risk Population. RMD Open 2025, 11, e005111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilonen, J.; Lempainen, J.; Veijola, R. The Heterogeneous Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Ley, R.E.; Volchkov, P.Y.; Stranges, P.B.; Avanesyan, L.; Stonebraker, A.C.; Hu, C.; Wong, F.S.; Szot, G.L.; Bluestone, J.A.; et al. Innate Immunity and Intestinal Microbiota in the Development of Type 1 Diabetes. Nature 2008, 455, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, A.D.; Gevers, D.; Siljander, H.; Vatanen, T.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Hämäläinen, A.-M.; Peet, A.; Tillmann, V.; Pöhö, P.; Mattila, I.; et al. The Dynamics of the Human Infant Gut Microbiome in Development and in Progression toward Type 1 Diabetes. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gong, C.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. A Pilot Study on the Characterization and Correlation of Oropharyngeal and Intestinal Microbiota in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1382466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, C.; João, M.F.D.; Camargo, G.A.d.C.G.; Teixeira, G.S.; Machado, T.S.; Azevedo, R.d.S.; Mariano, F.S.; Colombo, N.H.; Vizoto, N.L.; Mattos-Graner, R.d.O. Microbiological, Lipid and Immunological Profiles in Children with Gingivitis and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2017, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciantar, M.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Hurel, S.J.; Newman, H.N.; Wilson, M.; Spratt, D.A. Capnocytophaga Spp. in Periodontitis Patients Manifesting Diabetes Mellitus. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahari, S.; Chatterjee, D.; Negi, S.; Kaur, J.; Singh, B.; Agrewala, J.N. Morbid Sequences Suggest Molecular Mimicry between Microbial Peptides and Self-Antigens: A Possibility of Inciting Autoimmunity. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latov, N. Campylobacter jejuni Infection, Anti-Ganglioside Antibodies, and Neuropathy. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyati, K.K.; Nyati, R. Role of Campylobacter jejuni Infection in the Pathogenesis of Guillain-Barré Syndrome: An Update. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 852195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunath, B.J.; De Rudder, C.; Laczny, C.C.; Letellier, E.; Wilmes, P. The Oral–Gut Microbiome Axis in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammad, M.I.; Conrads, G.; Abdelbary, M.M.H. Isolation, Identification, and Significance of Salivary Veillonella Spp., Prevotella Spp., and Prevotella salivae in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1278582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk-Sowa, M.; Medrek, A.; Madej, P.; Michlicka, W.; Dobrakowski, P. Does the Gut Microbiota Influence Immunity and Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis Pathophysiology? J Immunol Res 2017, 2017, 7904821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.K.; Ito, K.; Dhib-Jalbut, S. Interaction of the Gut Microbiome and Immunity in Multiple Sclerosis: Impact of Diet and Immune Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, W.; Huai, Y. Changes in Gut Microbiota in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Based on 16s rRNA Gene Sequencing Technology: A Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, K.; Cui, M.; Ye, W.; Zhao, G.; Jin, L.; Chen, X. The Progress of Gut Microbiome Research Related to Brain Disorders. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.M.; Yadav, M.; Ghimire, S.; Lehman, P.C.; Patel, A.J.; Woods, S.; Olalde, H.; Hoang, J.; Paullus, M.; Cherwin, C.; et al. Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Is Associated With a Dysbiotic Oral Microbiome. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Lukiw, W.J. Bacteroides fragilis Lipopolysaccharide and Inflammatory Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, S.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, J. Bacteroidetes Promotes Esophageal Squamous Carcinoma Invasion and Metastasis through LPS-Mediated TLR4/Myd88/NF-κB Pathway and Inflammatory Changes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusthen, S.; Kristoffersen, A.K.; Young, A.; Galtung, H.K.; Petrovski, B.É.; Palm, Ø.; Enersen, M.; Jensen, J.L. Dysbiotic Salivary Microbiota in Dry Mouth and Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cui, G.; Huang, W.; Zheng, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhan, Y.; Ding, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Alterations in the Human Oral Microbiota in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muszyński, D.; Kucharski, R.; Marek-Trzonkowska, N.; Kalinowska, M.; Brzóska, A.; Bolcewicz, M.; Kalinowski, L.; Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K. Treatment of Xerostomia in Sjögren’s Syndrome—What Effect Does It Have on the Oral Microbiome? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1484951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, F.; Bi, C.; Shi, Q.; Chen, X. The Oral Microbiome and Its Role in Systemic Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review of Big Data Analysis. Front. Big Data 2022, 5, 927520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Taxonomic Label | Effect Direction | Robustness Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | k__Bacteria|p__Proteobacteria|c__Gammaproteobacteria|o__Burkholderiales|f__Neisseriaceae|g__Eikenella|s__Eikenella_sp001648475_mgs_3302 | Protective | Robust |

| k__Bacteria|p__Spirochaetota|c__Spirochaetia|o__Treponematales|f__Treponemataceae|g__Treponema_A|s__unclassified_mgs_2892 | Risk | Robust | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Fusobacteriota|c__Fusobacteriia|o__Fusobacteriales|f__Leptotrichiaceae|g__Leptotrichia|s__Leptotrichia_massiliensis_mgs_3259 | Protective | Suggestive (Phenotypic screening revealed horizontal pleiotropy) | |

| Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) | k__Bacteria|p__Bacteroidota|c__Bacteroidia|o__Flavobacteriales|f__Flavobacteriaceae|g__Capnocytophaga|s__unclassified_mgs_2361 | Risk | Robust |

| k__Bacteria|p__Bacteroidota|c__Bacteroidia|o__Flavobacteriales|f__Flavobacteriaceae|g__Capnocytophaga|s__Capnocytophaga_sputigena_mgs_3242 | Risk | Robust | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Campylobacterota|c__Campylobacteria|o__Campylobacterales|f__Campylobacteraceae|g__Campylobacter_A|s__unclassified_mgs_2445 | Risk | Robust | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Fusobacteriota|c__Fusobacteriia|o__Fusobacteriales|f__Leptotrichiaceae|g__Leptotrichia|s__Leptotrichia_massiliensis_mgs_3259 | Protective | Suggestive (Phenotypic screening revealed horizontal pleiotropy) | |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | k__Bacteria|p__Firmicutes|c__Negativicutes|o__Veillonellales|f__Veillonellaceae|g__Veillonella|s__unclassified_mgs_1430 | Risk | Robust |

| k__Bacteria|p__Firmicutes|c__Bacilli|o__Staphylococcales|f__Gemellaceae|g__Gemella|s__unclassified_mgs_2990 | Risk | Robust | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Firmicutes|c__Clostridia|o__Lachnospirales|f__Lachnospiraceae|g__Lachnoanaerobaculum|s__unclassified_mgs_645 | Risk | Robust | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Firmicutes|c__Bacilli|o__Lactobacillales|f__Streptococcaceae|g__Streptococcus|s__Streptococcus_pseudopneumoniae_O_mgs_1029 | Protective | Suggestive (Phenotypic screening revealed horizontal pleiotropy) | |

| k__Bacteria|p__Firmicutes|c__Bacilli|o__Lactobacillales|f__Streptococcaceae|g__Streptococcus|s__unclassified_mgs_880 | Protective | Suggestive (Phenotypic screening revealed horizontal pleiotropy) | |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | k__Bacteria|p__Bacteroidota|c__Bacteroidia|o__Bacteroidales|f__Bacteroidaceae|g__F0040|s__unclassified_mgs_3481 | Risk | Robust |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, W. Causal Relationships Between the Oral Microbiome and Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Pathogens 2026, 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010009

Wu X, Zhang X, Liang Y, Chen X, Guo Y, Zhao W. Causal Relationships Between the Oral Microbiome and Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xinyu, Xinye Zhang, Yuee Liang, Xuan Chen, Yuang Guo, and Wanghong Zhao. 2026. "Causal Relationships Between the Oral Microbiome and Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010009

APA StyleWu, X., Zhang, X., Liang, Y., Chen, X., Guo, Y., & Zhao, W. (2026). Causal Relationships Between the Oral Microbiome and Autoimmune Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Pathogens, 15(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010009