Oral Microbiota Alterations and Potential Salivary Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Next-Generation Sequencing Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Participants aged over 18 years.

- Non-pregnant individuals.

- No antibiotic use in the past three months.

- No recent surgical interventions.

- Absence of chronic diseases or active infections.

2.1. Microbiota Analysis

2.1.1. Sample Collection and Storage

2.1.2. DNA Isolation from Saliva Samples

2.1.3. Amplification of 16S Hypervariable Regions

2.1.4. Library Preparation and Sequencing

2.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Findings

3.2. The Results of Oral Microbiota Analysis

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity

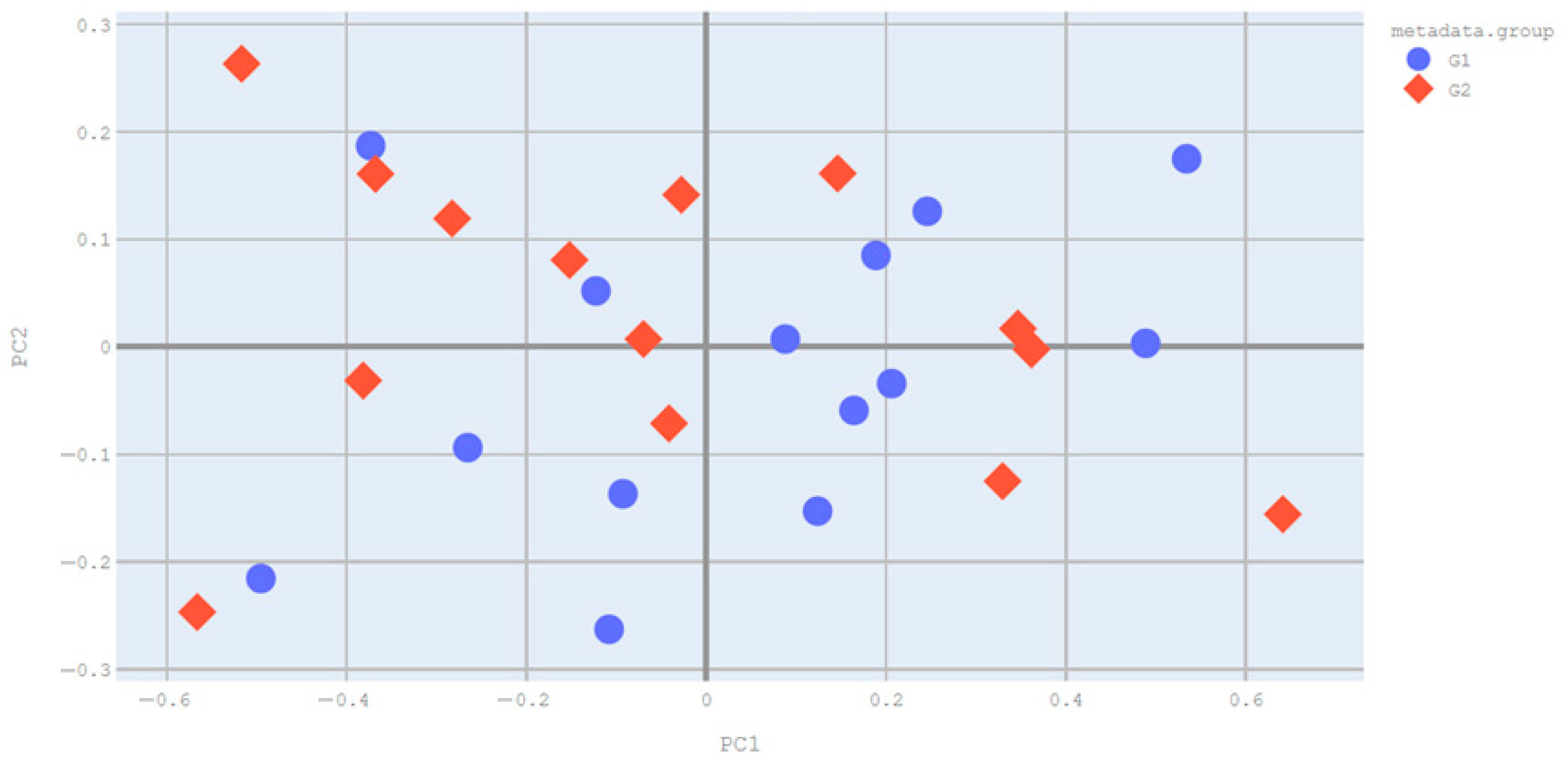

3.2.2. Beta Diversity

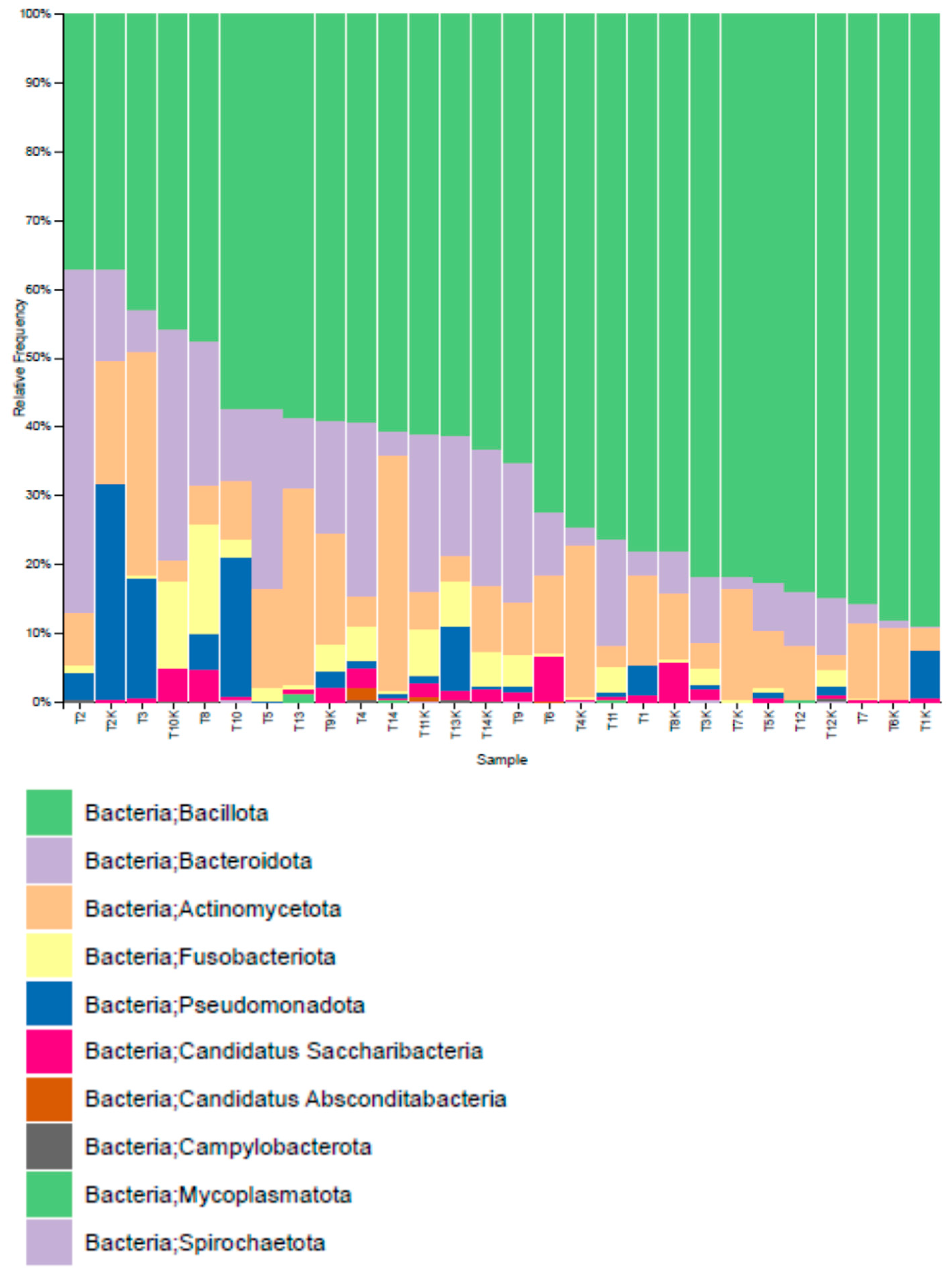

3.2.3. Distribution of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs)

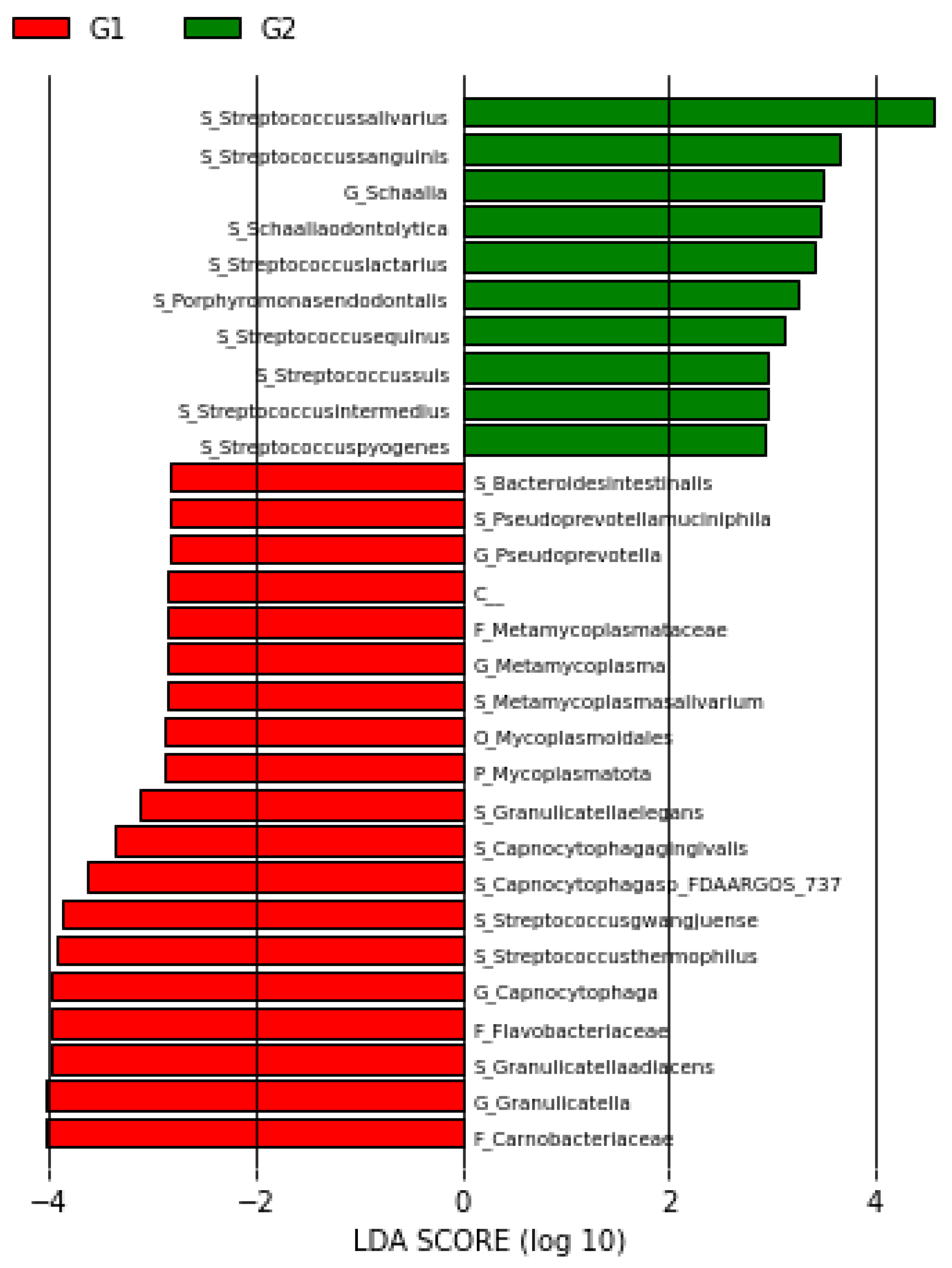

3.3. LEFse Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaz, A.M.; Brentnall, T.A. Genetic testing for colon cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 3, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, N.L. Cancer, aging and the optimal tissue design. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005, 5, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.G.; Karlitz, J.J.; Yen, T.; Lieu, C.H.; Boland, C.R. The rising tide of early-onset colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical features, biology, risk factors, prevention, and early detection. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, E.; Carrillo, M.; Leoz, M.L.; Cubiella, J.; Gargallo, C.; Lanas, A.; Bujanda, L.; Gimeno-García, A.Z.; Hernández-Guerra, M.; Nicolás-Pérez, D.; et al. Risk of advanced neoplasia in first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer: A large multicenter cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.L.; Garrett, W.S. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.; Miller, K.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sirsat, A.; Singh, H.; Cash, P. Microbiota and cancer: Current understanding and mechanistic implications. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koliarakis, I.; Messaritakis, I.; Nikolouzakis, T.K.; Hamilos, G.; Souglakos, J.; Tsiaoussis, J. Oral bacteria and intestinal dysbiosis in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiya, Y.; Shimomura, Y.; Higurashi, T.; Sugi, Y.; Arimoto, J.; Umezaw, S.; Uchiyama, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakajima, A. Patients with colorectal cancer have identical strains of fusobacterium nucleatum in their colorectal cancer and oral cavity. Gut 2019, 68, 1335–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda-Olmedo, I.; Rubio, L. Dietary legumes, intestinal microbiota, inflammation and colorectal cancer. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araos, R.; D’Agata, E. The human microbiota and infection prevention. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, G.; Tap, J.; Voigt, A.Y.; Sunagawa, S.; Kultima, J.R.; Costea, P.I.; Amiot, A.; Böhm, J.; Brunetti, F.; Habermann, N.; et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014, 10, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, R.; Shu, R.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Long, H.; Jin, S.; Li, S.; Hu, Q.; Yao, F.; et al. Study of the relationship between microbiome and colorectal cancer susceptibility using 16SrRNA sequencing. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 30, 7828392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezasoltani, S.; Aghdaei, H.A.; Jasemi, S.; Gazouli, M.; Dovrolis, N.; Sadeghi, A.; Schlüter, H.; Zali, M.R.; Sechi, L.A.; Feizabadi, M.M. Oral Microbiota as Novel Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer Screening. Cancers 2022, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.J.; Sanders, J.G.; Delsuc, F.; Metcalf, J.; Amato, K.; Taylor, M.W.; Mazel, F.; Lutz, H.L.; Winker, K.; Graves, G.R.; et al. Comparative analyses of vertebrate gut microbiomes reveal convergence between birds and bats. mBio 2020, 7, e02901-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, C.O.; Matsen, I.V.F.A. Abundance-weighted phylogenetic diversity measures distinguish microbial community states and are robust to sampling depth. PeerJ 2013, 1, e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Waste not, want not: Why rarefying microbiome data is inadmissible. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, Y. The composition alteration of respiratory microbiota in lung cancer. Cancer Investig. 2020, 38, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, O.J.; Varela-Calviño, R.; Graña-Suárez, B. Immunology and Immunotherapy of Colorectal Cancer. In Cancer Immunology: Cancer Immunotherapy for Organ-Specific Tumors; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 261–289. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.P.; Zhou, H.L.; Chen, H.B.; Zheng, M.Y.; Liang, Y.W.; Gu, Y.T.; Li, W.-T.; Qiu, W.-L.; Zhou, H.-G. Gut microbiota interactions with antitumor immunity in colorectal cancer: From understanding to application. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jin, K.; Xiong, K.; Jing, W.; Pang, Z.; Feng, M.; Cheng, X. Disease-associated gut microbiome and critical metabolomic alterations in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 15720–15735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.H.; Parsonnet, J. Role of bacteria in oncogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Cocchi, F.; Latinovic, O.S.; Curreli, S.; Krishnan, S.; Munawwar, A.; Gallo, R.C.; Zella, D. Role of Mycoplasma Chaperone DnaK in Cellular Transformation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Shu, X.O.; Steinwandel, M.D.; Blot, W.J.; Zheng, W.; Long, J. Prospective study of oral microbiome and colorectal cancer risk in low-income and african american populations. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemer, B.; Warren, R.D.; Barrett, M.P.; Cisek, K.; Das, A.; Jeffery, I.A.; Hurley, E.; O‘Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The oral microbiota in colorectal cancer is distinctive and predictive. Gut 2018, 67, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göktürk, K.; Tülek, B.; Kanat, F.; Maçin, S.; Arslan, U.; Shahbazov, M.; Göktürk, Ö. Gut microbiota profiles of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Exp. Lung Res. 2024, 50, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemer, B.; Herlihy, M.; O’Riordain, M.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. Tumour-associated and non-tumour-associated microbiota: Addendum. Gut Microbes 2018, 9, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, S.; Fang, L.; Lee, M.H. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in promoting the development of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Wear, D.J.; Shih, J.; Lo, S.C. Mycoplasmas and oncogenesis: Persistent infection and multistage malignant transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 10197–10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimolai, N. Do mycoplasmas cause human cancer? Can. J. Microbiol. 2001, 47, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarovits, J. Anaerobic bacterial communities associated with oral carcinoma: Intratumoral, surface-biofilm and salivary microbiota. Anaerobe 2021, 68, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhang, C.P. The oral microbiota may have influence on oral cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 9, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Nakatsu, G.; Han, J.; Xu, W. Gavage of fecal samples from patients with colorectal cancer promotes intestinal carcinogenesis in germ-free and conventional mice. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, O.L.; Vodnar, D.C.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Istrati, M.; Bințințan, A.; Bințințan, V.V. An overview of gut microbiota and colon diseases with a focus on adenomatous colon polyps. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saylam, E.; Özden, Ö.; Yerlikaya, F.H.; Sivrikaya, A.; Yormaz, S.; Arslan, U.; Topkafa, M.; Maçin, S. Investigation of intestinal microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in colorectal cancer and detection of biomarkers. Pathogens 2025, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, Z.; Li, Y.; Lv, C.; Li, C.; Hu, Y.; Fu, M.; Song, L. Salivary and fecal microbiota: Potential new biomarkers for early screening of colorectal polyps. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1182346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phylum (Relative Abundance %) | Study Groups | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 14) | CRC (n = 14) | ||

| Bacillota (Firmicutes) | 70.84 ± 16.19 | 63.25 ± 14.85 | 0.125 |

| Bacteroidota | 11.38 ± 9.72 | 15.12 ± 12.78 | 0.352 |

| Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria) | 4.08 ± 8.42 | 4.04 ± 6.63 | 0.982 |

| Fusobacteriota | 2.80 ± 3.65 | 2.48 ± 4.15 | 0.982 |

| Actinomycetota | 9.33 ± 6.40 | 13.53 ± 10.35 | 0.306 |

| Candidatus saccharibacteria | 1.38 ± 1.71 | 1.20 ± 1.91 | 0.462 |

| Candidatus absconditabacteria | 0.08 ± 0.20 | 0.16 ± 0.54 | 0.705 |

| Campylobacterota | 0.04 ± 0.08 | 0.05 ± 0.09 | 0.931 |

| Mycoplasmatota | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.30 | <0.05 |

| Spirochaetota | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.04 ± 0.11 | 0.388 |

| Family (Relative Abundance %) | Study Groups | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 14) | CRC (n = 14) | ||

| Carnobacteriaceae | 2.47 ± 1.85 | 5.10 ± 4.01 | 0.021 |

| Mycoplasmoidales | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.3 | <0.05 |

| Flavobacteriaceae | 0.43 ± 0.5 | 2.47 ± 2.97 | 0.007 |

| Metamycoplasmataceae | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.3 | <0.05 |

| Genus (Relative Abundance %) | Study Groups | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 14) | CRC (n = 14) | ||

| Granulicatella | 2.47 ± 1.85 | 5.09 ± 3.99 | 0.021 |

| Streptococcus | 57.49 ± 18.11 | 49.55 ± 15.02 | 0.194 |

| Fusobacterium | 0.44 ± 0.61 | 0.35 ± 0.54 | 0.539 |

| Pseudoprevotella | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.23 | <0.05 |

| Capnocytophaga | 0.43 ± 0.50 | 2.47 ± 2.97 | 0.007 |

| Porphyromonas | 2.78 ± 4.77 | 1.65 ± 2.93 | 0.836 |

| Veillonella | 2.61 ± 2.73 | 2.76 ± 2.78 | 0.571 |

| Megasphaera | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 0.19 ± 0.54 | 0.353 |

| Haemophilus | 0.38 ± 0.53 | 2.10 ± 4.74 | 0.452 |

| Species (Relative Abundance %) | Study Groups | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 14) | CRC (n = 14) | ||

| Granulicatella adiacens | 2.16 ± 1.8 | 4.44 ± 3.68 | 0.021 |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | 1.85 ± 1.26 | 2.84 ± 6.55 | 0.050 |

| Streptococcus gwangjuense | 0.46 ± 0.43 | 2.26 ± 2.26 | <0.05 |

| Capnocytophaga sp.

FDAARGOS_737 | 0.10 ± 0.24 | 0.96 ± 1.43 | <0.001 |

| Capnocytophaga gingivalis | 0.16 ± 0.20 | 0.57 ± 0.61 | 0.030 |

| Granulicatella elegans | 0.31 ± 0.36 | 0.65 ± 0.59 | 0.029 |

| Metamycoplasma salivarium | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.3 | <0.05 |

| Bacteroides intestinalis | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.23 | <0.05 |

| Pseudoprevotella muciniphila | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.1 ± 0.23 | <0.05 |

| Prevotella denticola | 0.04 ± 0.11 | 0.11 ± 0.25 | 0.405 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 0.02 ± 0.08 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.638 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 0.12 ± 0.23 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | 0.353 |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | 0.34 ± 0.43 | 2.08 ± 4.73 | 0.397 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maçin, S.; Özden, Ö.; Samadzade, R.; Saylam, E.; Çiftçi, N.; Arslan, U.; Yormaz, S. Oral Microbiota Alterations and Potential Salivary Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Next-Generation Sequencing Study. Pathogens 2026, 15, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010043

Maçin S, Özden Ö, Samadzade R, Saylam E, Çiftçi N, Arslan U, Yormaz S. Oral Microbiota Alterations and Potential Salivary Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Next-Generation Sequencing Study. Pathogens. 2026; 15(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaçin, Salih, Özben Özden, Rugıyya Samadzade, Esra Saylam, Nurullah Çiftçi, Uğur Arslan, and Serdar Yormaz. 2026. "Oral Microbiota Alterations and Potential Salivary Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Next-Generation Sequencing Study" Pathogens 15, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010043

APA StyleMaçin, S., Özden, Ö., Samadzade, R., Saylam, E., Çiftçi, N., Arslan, U., & Yormaz, S. (2026). Oral Microbiota Alterations and Potential Salivary Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer: A Next-Generation Sequencing Study. Pathogens, 15(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens15010043