1. Introduction

This quote is taken from a book about the Malay Sultanate of Perak in present-day Malaysia, written by a nineteenth-century British colonial official, John McNair. To be fair, McNair—who served seventeen years in the British colony of the Straits Settlements and other locations in the Malay peninsula and took great interest in the history and culture of the region—tried to nuance the image of the Malay as an inveterate pirate. The quote nonetheless illustrates the dominant perception among Europeans in the nineteenth century about the Malays, who were widely seen as a ferocious, treacherous, and uncivilized “race” with a strong and natural addiction to piracy. Similar assessments can be found in many nineteenth-century accounts of the Malays (e.g.,

Downes [1837] 1924;

Crawfurd 1856, pp. 353−55).

The long history of the idea of the “Malay” as a geographic, ethnic, linguistic, political, and racial category is complex, contradictory, and multifaceted. Ethnicity in pre-colonial Southeast Asia was never static but characterized by fluidity, porosity, and flexibility (e.g.,

Andaya 2008;

Warren 2002). These circumstances often caused considerable confusion to European visitors to the region, and the term Malay, in particular, has been used and defined in numerous and often ambiguous ways by European (and other) observers since the beginning of the sixteenth century. Historians have in recent years explored this complex history of the notion of the “Malay” and have, in doing so, made several important contributions to understanding its longer conceptual history (

Shamsul 1999;

Reid 2001;

Kahn 2005;

Goh 2007;

Andaya 2008;

Tagliacozzo 2009;

Skott 2014;

Skott 2017).

Some of these studies note, in passing, the tendency among nineteenth-century Europeans to describe the Malays as piratical (e.g.,

Goh 2007, p. 327;

Skott 2014, p. 133; see also

Alatas 1977, p. 130), but the longer history of the association, in the eyes of European observers, between piracy and the Malay has hitherto not been explored in depth (see (

Reber 1966;

Amirell 2018) for studies focusing mainly on the nineteenth century). Against this background, the present article sets out to sketch how Europeans in the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries moved from understanding “Malay” as a rather precise and limited term used to denote a specific ethnic and linguistic group to instead defining it as a broad ethnic category, which, after the middle of the eighteenth century, became strongly associated with piratical inclinations and activities as well as a generally treacherous and violent disposition. This development preceded the notion, originally proposed by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in 1781, that the Malay constituted one of five supposed principle races (or varieties) of mankind (

Blumenbach 1781).

In the following, the early modern European perceptions of the Malay are traced through some of the most influential texts written by early modern Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, British, and French observers. In particular, the changes in European perceptions of the Malay in the course of the eighteenth century are outlined. It is argued that the broadening of the understanding of the term Malay went hand in hand with a more negative view of their character, particularly with regard to their alleged inclination to piracy. The concluding discussion analyzes the changes in the European perceptions of the Malays during the eighteenth century and highlights how the increasingly broad and negative European view of the Malays laid the foundations for the persistent nineteenth-century European image of the Malay as an inherently piratical, treacherous, and rapacious “race”.

2. Early European Perceptions of the Malay

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European descriptions of maritime Southeast Asia—that is, the region that later, particularly after the mid-nineteenth century, came to be called the Malay Archipelago—generally emphasized the cultural heterogeneity of the area. European visitors tended to see a mosaic of ethnic and linguistic groups with different languages, habits, and cultures. With regard to religion, for example, most inhabitants of the archipelago were found to be Muslims, but the forms of Islam that were practiced in Southeast Asian archipelago seemed to vary greatly and often appeared to be very different from the religion as it was practiced in the Middle East and North Africa. There were also sizeable populations of Jews and groups of people whom Europeans called “pagans” among the islanders, and a rich and mysterious legacy of Hinduism and Buddhism, particularly on Java and Bali (

Skott 2014, p. 131; cf.

Reid 1988).

The Portuguese, who besides the Spanish were the dominating group of Europeans in the archipelago for most of the sixteenth century, used the term

malayo (from the Malay word

Malayu) in a limited sense. Above all, it was used to refer to the dominant seafaring indigenous nation or group of people in the western part of the archipelago. The Portuguese also, like other inhabitants of the region, used the term to refer to the language of the Malays, which was used as lingua franca for communication between different ethnic groups and merchants throughout maritime Southeast Asia. For the early Portuguese observers,

malayo was thus understood as the name of the indigenous population and language of the Sultanate of Melaka (Malacca) and neighboring countries on what is today known as the Malay Peninsula (

Figure 1). Before the Portuguese conquered Melaka in 1511, the Sultanate was the main hub of the region’s trade and attracted merchants from all over the region, as well as from China, India, Persia, and Arabia (

Skott 2014, pp. 131−32;

Reid 2001, pp. 298−301).

As indicated by the seemingly peaceful couple in

Figure 1, there is no indication that Malays were particularly associated with piracy or other forms of maritime violence in the eyes of the Portuguese during the sixteenth century. The Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires, who wrote one of the most detailed and valuable early European accounts of Southeast Asia, makes no mention of Malays in connection with piracy, although he does describe several other peoples of the region, such as the inhabitants of Sumatra, Sunda, Java, and Eastern Indonesia, as engaging in piracy (

Pires 1944, pp. 139, 173, 228). Pires also identifies the so-called

Celates—an ethnically somewhat unclear term derived from the Malay word

selat, strait, and associated mainly with the Bajau, a group of sea nomads—as “corsairs” and “robbers” (

Pires 1944, pp. 227, 233, 262; cf.

Gaynor 2016, pp. 40−42).

Celates, writes Pires, “are thieving corsairs who go to sea in small paraos [sailing boats] robbing where they can” (

Pires 1944, p. 264). He identifies several places in the southern parts of the Strait of Malacca and on the east coast of Sumatra where the

Celates had settled. He also notes that they were obedient to the king of Melaka and served as rowers when the king so required (

Pires 1944, p. 264).

As indicated by Pires’s account, piracy and other forms of maritime raiding were common throughout Southeast Asia well before the arrival of the first Europeans in the region (

Gibson 1990;

Junker 1999). In times of political decentralization, raiding activities tended to surge and to be used by local chiefs and aristocrats, both for economic gain and for strengthening their political power and prestige. In times of political centralization, such as when Melaka was the dominant power in the Strait of Malacca in the fifteenth and early sixteenth century, maritime raiding tended to be brought under control and be used primarily at the behest of the ruler, both as a tactic of war and in order to project his or her power at sea. To early European observers, such use of maritime raiding to enforce a ruler’s naval capacity probably seemed familiar, given the widespread use of privateers in intra-European warfare at the time (

Amirell 2019, p. 44; cf.

Starkey 2011).

Spanish accounts from the Philippine Islands during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries also frequently mention piracy and other forms of maritime raiding conducted by various peoples of the southern Philippines, although the term “piracy” seems to have been used mainly to denote European or Chinese marauders (

Tremml-Werner Forthcoming). To the extent that local raiders or warriors, particularly from the southern Philippines or adjacent parts of the Indonesian archipelago, were labelled pirates, they were generally identified by the different islands or parts of the archipelago that they inhabited, such as Borneo, Sulu, Mindanao, or Ternate. They were also frequently described collectively as “Moros” (e.g.,

Combés 1667;

Blair 1906), a term taken by the Spanish from the Mediterranean, where it had been used in the context of the

reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula to denote the Muslim adversaries of the Christian Iberian kingdoms (

Hawkley 2014). In the course of the so-called Moro Wars in the Philippines, a series of wars and hostilities during the Spanish colonial period in the archipelago from the end of the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, maritime raiding was frequently used by both Spanish and Moros, both as a tactic of war and for the sake of plunder and the capture of slaves. In that context, the term Moro—rather than Malay—eventually, particularly during the nineteenth century, came to be closely associated with piracy in the eyes of Spanish officials and other observers in the region (

Frake 1980, pp. 314−15; cf.

Warren 2002, p. 23).

Seventeenth-century accounts of maritime Southeast Asia by other Europeans, such as Dutch and English travelers, also make little mention of piracy in relation to the Malays. Isaac Commelin’s illustrated collection of accounts of the early voyages of the Dutch East India Company, published in 1645, for example, mainly mentions piracy and accusations of piracy in relation to European navigators in Asian waters. The English historian

Thomas Herbert (

1638, pp. 314−33), meanwhile, makes no mention of piracy or other forms of maritime violence in his account of the Malay Archipelago, and the same is true for the Dutch traveler

Johannes Nieuhof (

1670).

The English merchant Thomas Bowrey, in his account of the countries around the Bay of Bengal (including the Strait of Malacca) from 1669 to 1679, mentions piracy in connection with some of the peoples he describes, such as the Arakaners (on the north coast of the Bay of Bengal) and the Celates (

Saleeters) in the Strait of Malacca. He also accuses the Malays (

Malayers) of the Mergui Archipelago (in present-day southern Burma) of piracies and describes them as a “very roguish Sullen ill natured people” (

Bowrey 1905, p. 237). This negative characterization, however, seems only to apply to the Malays of the Mergui Archipelago and, like other seventeenth-century observers, Bowrey does not use the term Malay to describe the majority of the population of maritime Southeast Asia. He did, however, understand that the Malay language was spoken and understood throughout the archipelago and published a pioneering Dictionary of English and Malay (

Bowrey 1701). Bowrey also identified Kedah in the northern part of the Strait of Malacca as a region with many “rogues” who commit piracies and other villainies, which he explains by the previously too merciful and lenient government of the king. These rogues seem to have been derived both from the indigenous population of Kedah and from

Celates (

Bowrey 1905, pp. 261−62).

William Dampier—an English explorer and navigator who himself had a well-honed reputation for piracy—also discusses the subject of piracy at some length in his account of his visit to the Strait of Malacca in 1689. He acknowledged that there were Malays in the Strait of Malacca who engaged in piracy, but he did not think that it was part of their culture or character but rather due to the monopolistic trading practices of the Dutch East India Company:

The Malayans, who inhabit on both sides the Streights of Malacca, are in general a bold People, and yet I do not find any of them addicted to Robbery, but only the pilfering poorer Sort, and even these severely punished among the trading Malayans, who love Trade and Property. But being thus provoked by the Dutch, and hindred of a free Trade by their Guard-ships, it is probable, they therefore commit Piracies themselves, or connive at and incourage those who do. So that the Pirates who lurk on this Coast, seem to do it as much to revenge themselves on the Dutch, for restraining their Trade, as to gain this way what they cannot obtain in way of Traffick.

Finally, François Valentijn, a Dutch East India Company official and naturalist who spent sixteen years in Southeast Asia and wrote a five-volume illustrated work about the East Indies in the 1720s, mentions pirates (

Zee-roovers) on several occasions. Like in Commelin’s earlier account, however, many of these refer to allegations of piracy made by Europeans against other Europeans (e.g.,

Valentijn 1724–1726, vol. 1, p. 211). He also describes certain indigenous, non-Malay communities as pirates—even “naughty” (

stoutte) or “great” (

grote) pirates—but generally without providing any further evidence or details (e.g.,

Valentijn 1724–1726, vol. 2, pp. 34, 42, 83).

Such invectives, however, need to be read source critically and in their historical context. Dutch allegations of piracy against indigenous communities were part of a discourse, according to which officials of the Dutch East India Company, in various terms, denounced those who were seen as disregarding the Company’s treaty-based trading regulations or in other ways opposed the Dutch (

Rubin 1988, pp. 220−21). Other common terms used by the Dutch were

zeeschuymers (sea rovers),

loerendreijers (cheats) and

schelmen (rascals) (Hans Hägerdal, personal conversation).

Importantly in the present context, however, like other seventeenth-century observers, Valentijn does not associate the Malays with piratical activities. Tellingly, he is more concerned about the threat from wild animals, such as tigers and elephants, in his description of Melaka and its hinterland than with any threat of piracy along the coast (

Valentijn 1724–1726, vol 5:1, p. 310). Far from describing the Malays as piratical, Valentijn describes them as the “most sensible, shrewd and well-mannered people of the entire East” (ibid). He does, however, describe the people of the Perak—an offshoot of the Malay nation, according to Valentijn—on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula as “nasty and murderous”, although he does not explicitly link Perak or any of the other Sultanates in the Strait of Malacca to piracy or other forms of maritime violence and robbery (

Valentijn 1724–1726, vol 5:1, pp. 311, 317−18).

In sum, European observers in general did not associate the Malays with piracy during the first two centuries of European expansion in the region. Above all, European observers tended to accuse navigators from other European nations in the region of being pirates. Several observers also noted that piratical activity occurred in the region but linked it for the most part to other ethnic groups than the Malays, particularly several ethnic groups in the southern Philippines, the Bugis and the so-called Celates, in the Strait of Malacca. The Malays, understood in principle as the people of Melaka and the diaspora that spread across the archipelago following the Portuguese conquest of the city in 1511, by contrast, were generally not associated with piracy, but rather with commerce, refinement, and cultural achievement. Moreover, to the extent that some Malays were described as engaging in piratical activities, as observed by Thomas Bowrey and William Dampier toward the end of the seventeenth century, their behaviour was not seen as part of any inherent national trait or flaw of character, but rather as either a local phenomenon or a justified response to the exploitation and coercion of the Dutch.

3. Changing Perceptions in the Eighteenth Century

In the course of the eighteenth century, European perceptions of the Malays changed significantly and became both broader and more negative. The process accelerated during the second half of the century, when the foundations were laid for the European notion, or trope, of the Malay pirate. However, it was not a uniform process, and there were considerable differences of opinion between observers and visitors to the archipelago.

The first part of the changing European perception of the Malay in the eighteenth century was the extension of the scope of the term Malay, which now came to be understood as encompassing all or most of the indigenous population of maritime Southeast Asia with the exception of some inland, mainly hillside, groups whose language, culture, and physical appearance seemed very different from those of the majority of the population in the lowlands and coastal areas. The publication in 1736 of a Malay grammar, written by the Swiss pastor George Hendrik Werndlij, was crucial in this development (

Werndlij 1736). Werndlij described Malay not only as the vernacular language of the Malays proper (i.e., the people of Melaka and its diaspora), but also as a learned language that was not tied to a specific ethnic group or geographic area in the region. Consequently, during the eighteenth century the ubiquity of the Malay language and the visibility of a specifically Malay culture in the port cities created, as put by

Christine Skott (

2014, p. 132; cf.

Reid 2001), “an ambivalent but persistent European perception that all the inhabitants of the archipelago were Malay”.

This perception stimulated European observers to describe the Malays as a more or less homogenous ethnic group that inhabited the coastal areas of the archipelago stretching from the Philippines in the east to Sumatra in the west. One of the most influential travelers in the eighteenth century to do so was Pierre Poivre, a French missionary-turned-entrepreneur and naturalist, who first visited Southeast Asia in the 1740s, when his markedly negative views of the indigenous population of the region seem to have been formed. In his journal from that voyage—which remained unpublished until 1968 and thus probably had little influence on European perceptions of the Malays in his own time—Poivre described the Malay nation as mean (

méchante) and treacherous (

perfide) (

Poivre 1968 [c. 1745], p. 41). He also, in contrast to most earlier European observers discussed above, linked the Malays to piratical activities and emphasized their alleged bloodthirst and hatred of Europeans:

[T]hey are lazy, and consequently poor, the majority [being] thieves and pirates; one can not believe the extent to which they make themselves feared on all the coasts neighbouring their country. Every year they take to the sea on a great number of well-armed barques and disperse in all directions to go and seek fortune, above all they carry away all they can find, even the men and the women, whom they take along and sell as slaves in their country, except for the Europeans, whose throats they slit without mercy whenever they are able to catch them.

Poivre became a widely read authority on the Malays some twenty years later, with the publication in 1768 of his book

Voyages d’un philosophe. The short (140 small pages) book was widely read throughout Europe and was translated to English the following year (

Poivre 1769). Although Poivre only spent eight pages of the book describing the society and culture of the Malays (under the somewhat misleading heading “State of the agriculture among the Malays”, a topic that he dealt with rather summarily on the final three pages of the chapter), he temporarily became the most quoted European commentator on the Malays (

Skott 2014, p. 133).

In comparison with several of the earlier European observers of the Malays, such as Pires and Valentijn, both of whom spent several years in Southeast Asia and wrote extensively about the history, religion, culture, and society of the region, Poivre had little in-depth knowledge of the Malays. His influence was probably due primarily to the fact that there was very little up-to-date knowledge about the Malays and of most of maritime Southeast Asia in Europe at the time. To the extent that Europeans in the second half of the eighteenth century took any interest in the maze of islands to the east of the Malay peninsula, it formed a “world of mystery and complexity”, as put by

C. Northcote Parkinson (

[1937] 1966, p. 347).

The lack of knowledge about the Malays in Europe is attested to by the ninth volume of the Encyclopédie, edited by Denis Diderot and published three years before the first edition of Poivre’s Voyages appeared. There is no entry for Malays (Malais in French) in the Encyclopédie, although there is one for the Malay Peninsula (Malacca, Péninsule de), in which its inhabitants are described briefly with regard to their physical appearance and customs. They are not identified as Malays, however:

The inhabitants of this peninsula are black, small, well proportioned in their small size, and dangerous when they have consumed opium, which causes in them a kind of furious exaltation. They are all nude from the waist upward, with the exception of a small scarf which they carry over one shoulder or the other. They are very lively, very sensual, and the blacken their teeth through the frequent use that they make of betel nut.

In introducing his reader to the Malays, Poivre expressed his surprise that the Malay nation, which, according to him, occupied such a considerable part of the earth, was scarcely known at all in Europe. Europe’s ignorance of the Malays was all the more puzzling, according to Poivre, in view of their having once been one of the greatest powers in Asia, covering the sea with their ships and presiding over an immense commerce. From the Malay Peninsula they colonized Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Celebes, the Moluccas, and the Philippines, Poivre claimed, in addition to numerous islands further to the east. Consequently, all of the inhabitants of these islands, at least those on the coasts, were the same people, speaking more or less the same language and having the same laws and customs, Poivre argued (

Poivre 1768, pp. 51−52).

Having thus established that the Malays populated all of the coasts and islands of maritime Southeast Asia, Poivre went on to discuss their laws and social and political organization. In contrast to his earlier view in the 1740s—when he, possibly under the influence of Dampier’s account, had speculated that Dutch oppression might be to blame for the allegedly bad character of the Malays—he now argued that it was a result of their laws. The laws were “feudal” and “bizarre”, according to Poivre, as they pretended to protect a minority of prominent people against the power of the ruler, while delivering the majority of the population to slavery:

With such laws the Malays are a restless people, preferring seafaring, war, pillage, emigrations, colonies, adventures, galanterie. They talk endlessly about honour and bravery, and actually they are seen by those who visit them as the most treacherous and ferocious people on earth.

He continued to elaborate on their piratical inclinations:

This ferocity, which the Malays see as bravery, is so well-known among the European companies in the Indies that all of them have agreed to issue a regulation which prohibits the captains of their vessels sailing in the Malay islands to take on board any seaman of this nation or at most, in case of extreme need, not to take more than 2 or 3.

One has seen from time to time some of these atrocious men, having embarked recklessly in very small numbers, attack a vessel when least expected, dagger in hand, and kill many men before being overmanned. One has seen Malay boats armed by 25 to 30 men, boldly board European vessels with 40 cannons in order to seize the vessel and massacre a part of the crew with their daggers. Malay history is full of similar features, all of which testify to the most audacious ferocity.

The Malays’ addiction to piracy and plunder, according to Poivre, was linked to their mobility and their restless (

inquiet) nature, which he in turn, as we have seen, explained with reference to their laws. Moreover, with an implicit reference to Montesquieu’s theory about the impact of the climate on the nature of man and his society, outlined twenty years earlier in

De l’Esprit des loix (

Montesquieu 1748), Poivre held that the Malay case proved that despite the greatest difference in climate, their laws were in fact similar to those of northern Europe long ago (presumably a reference to the Vikings) and consequently produced similar habits, customs, and tendencies (

Poivre 1768, pp. 53, 56).

Poivre’s book was widely read across Europe, but his views of the Malays were not immediately accepted by all Europeans. In particular, several British observers—some of whom spent several years as traders in Southeast Asia and gained a more intimate knowledge of the languages and cultures of the region than brief visitors such as Poivre—continued to describe the Malays in largely positive terms. This circumstance was linked to the increased British commercial interest in maritime Southeast Asia, particularly from the 1760s onward, as the region was drawn into the maritime trade network between India, China, and Europe.

One of the staunchest proponents of British expansion in Southeast Asia was Alexander Dalrymple, a Scottish geographer and East India Company official who spent most of the time between 1757 and 1764 in the region trying to further the company’s trade (

Fry [1970] 2006). Like in most earlier European descriptions of the Malay Archipelago, there was little mention of piracy in Dalrymple’s accounts, although he, like earlier European observers, did identify certain ethnic groups who were not identified as Malays as piratical. For example, in a pamphlet entitled

A plan for Extending the Commerce of this Kingdom: and of the East-India-Company, published in 1769, Dalrymple described a group of Iranun who had settled on the coast of north Borneo as pirates. Originally from Mindanao, Dalrymple writes, around 500 of these pirates had settled in Tampasuk (in present-day Sabah, Malaysia) after having caused much mischief and carried off many inhabitants of the Philippines (

Dalrymple 1769, pp. 57–58). Thomas Forrest, another Scottish East India Company official who spent several years in the eastern part of the Malay Archipelago a few years after Dalrymple, also described the Iranun as “very piratically inclined”, along with the Tidong, whom he described as “a savage piratical people” (

Forrest 1779, pp. 318, 396).

Neither Dalrymple or Forrest, however, described the Malays in general, nor the so-called Moros of the southern Philippines, as addicted to piracy. Not even the Sulu Sultanate—which from the early years of the nineteenth century came to be seen by most Europeans in the region as an essentially piratical state—was implied in piracy (cf.

Reber 1966, pp. 33−65). Forrest even claimed that the Sulunese discountenanced the piracies of the Tidong and denied them to use any of the ports on Jolo, the main island of the Sultanate (

Forrest 1779, p. 17).

Dalrymple also took a favorable view of the indigenous inhabitants of Sulawesi, including the Bugis, who otherwise often were accused of piracy by European observers. He denounced the tendency to ascribe to the Bugis and other inhabitants of the region treachery of character and to treat them with “that odious superiority, which too much prevails with Europeans over the natives in all parts of India” (

Dalrymple 1769, pp. 101−02).

Given that Dalrymple’s purpose was to argue for greater involvement of the East India Company in Southeast Asia, he could be expected to try to downplay any problem of piracy in the region and instead advertise its virtues (

Reber 1966, p. 64). However, the accounts from James Cook’s first voyage, which sailed through Southeast Asia in 1770 on its voyage back to England from the Pacific, corroborate the impression that piracy was not widely seen as typical trait of character of the Malays around that time. For example, Cook himself, in his diary, makes no mention of piratical activities among the indigenous inhabitants of the Malay Archipelago, even though he explicitly focused his account of Batavia (present-day Jakarta on Java) on things that he thought were necessary for seamen to know (

Cook 1893, p. 363). Neither is there any mention of piracy in the region in the published account of the voyage compiled by

John Hawkesworth (

1773), nor in the journal of the

Endeavour’s chief naturalist

Joseph Banks (

1896), nor in that of his artist,

Sydney Parkinson (

1784). The Scottish-German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster, who accompanied Cook on his second voyage (1772−75), meanwhile, described the Malays in positive terms and called them, among other things, “polished” and “civilized” and described their government as being of a “mild and humane kind” (

Forster 1778, p. 359).

Piracy and maritime raiding did occur in the archipelago, however, both, as we have seen, in Dalrymple’s time and earlier. Such activities increased sharply from the second half of the 1760s. In 1765, a devastating volcano eruption in Mindanao triggered the migration of the Iranun from the Lake Lanao district in the Mindanao highlands to what came to be known as Illana Bay off the south-west coast of Mindanao. Over the following years, Iranun raiders in particular began to assemble large fleets of raiding vessels that spread out over the Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia in quest for booty and, above all, captives that could be used or sold as slaves (

Warren 2002). The Iranun thus quickly gained a reputation for piracy and maritime raiding, both in the eyes of European observers and indigenous peoples in the region. By 1811, the British Lieutenant-Governor of Java, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (

Raffles 1830, p. 45), noted that the word

lanun (derived from Illanun, a variation of Iranun) was commonly used throughout the archipelago to denote almost all sea-rovers in the region, regardless of their ethnicity.

For the most part the attacks by the Iranun and other maritime raiders targeted local coastal communities and vessels, but European shipping was also affected. An English ship laden with opium was for example pirated off the southern coast of Borneo in 1766 and the crew was murdered (

Noorlander 1935, p. 50). In December the following year, the Royal Navy’s ship

Swallow fended off a piratical attack in the Strait of Makassar. Since the attack happened at night and none of the attackers were captured, the nationality of the pirates remained unknown to the English, although the commander of the

Swallow, Philip Carteret, seemed to suspect that they were from Makassar (

Carteret 1965, p. 213). Around the same time, the French circumnavigator Louis Antoine de Bougainville passed through the region, and even though his two ships were not attacked, he reported that almost all of the people on the South Sulawesi coast—that is, in the vicinity of Makassar—were pirates (

Bougainville 1771, p. 338).

Neither the Iranun or the Makassarese were in fact Malays in the strict sense of the word or spoke Malay as their native tongue. Such nuances, however, were lost due to the extended meaning that the word Malay came to take on in the eighteenth century. Moreover, the increase in maritime raiding and piratical attacks against European ships in the region after 1770 contributed to establish an impression in the eyes of European observers of the Malay Archipelago as one of the most pirate-infested regions in the world (cf.

Layton 2011).

4. The Rise of the Notion of the “Malay Pirate”

The surge in piratical activity in Southeast Asia toward the end of the eighteenth century combined with the onset of what

Jürgen Osterhammel (

2018, p. 230; cf.

Buchan and Andersson Burnett 2019a) has called an “unparalleled offensive on the part of the settled ‘civilizations’ against mobile ‘savages’ or ‘barbarians’” to create an image of the Malays as inveterate pirates. This tendency is obvious in one of the most influential accounts of the Malay Archipelago from the end of the eighteenth century,

The History of Sumatra, first published in 1783 by the British historian and linguist William Marsden. The work, even more than Poivre’s book, inaugurated a scholarly discourse in Europe, particularly in Great Britain, under the influence of the Scottish Enlightenment (

Knapman 2016), on the Malay Archipelago and its people.

The History of Sumatra quickly came to be seen as an authoritative account and continued to be regarded as such throughout the nineteenth century. Marsden thus exercised great influence on subsequent British scholars and colonial officials in the region, including Raffles and John Crawfurd. Marsden’s account was thus not only of scholarly importance; it also played a significant role in shaping British policies in the region and British understandings of the Malays (

Carroll 2002,

2018).

Like Poivre, Marsden was overwhelmingly negative in his description of the Malays and ascribed to them a “natural bent for” and an “invariable attachment to” trade and piracy (

Marsden 1783, pp. 36, 282):

… the Malay inhabitants have an appearance of degeneracy, and this renders their character totally different from that which we conceive of a savage, however justly their ferocious spirit of plunder on the eastern coasts, may have drawn upon them that name […] They retain a strong share of pride, but not of that laudable kind which restrains men from the commission of mean and fraudulent actions. They possess much low cunning and plausible duplicity, and know how to dissemble the strongest passions and most inveterate antipathy, beneath the utmost composure of features, till the opportunity of gratifying their resentment offers. Veracity, gratitude, and integrity are not to be found in the list of their virtues, and their minds are almost totally strangers to the sentiments of honour and infamy. They are jealous and vindictive. […] The Malay may be compared to the buffaloe and the tiger. In his domestic state, he is indolent, stubborn, and voluptuous as the former, and in his adventurous life, he is insidious, blood-thirsty and rapacious as the latter.

Marsden thus concurs with Poivre with regard to the purported treacherous and ferocious character of the Malays, but his account is more explicitly influenced by the theories of race that were becoming increasingly influential in Europe toward the end of the eighteenth century. Marsden’s use of the word “degeneracy” to describe the Malays is significant in this respect. The word did not have the connotations as it does today and should in its eighteenth-century context above all be understood in relation to the theory of human monogenism, which held that all human races or varieties shared a common origin. The theory was highly influential in Marsden’s time and was advocated by influential scientists such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, as well as earlier by Carl Linnaeus (e.g.,

Broberg 1975;

Junker 2019). Degeneracy, in the context of monogenism, did not primarily mean deterioration—although the word had such connotations too—but rather “departure from an initial form of humanity at the creation” (

Gould 1994, p. 5); from the Latin

de, meaning “from” and

genus, referring to the original, unitary variety of the human species).

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, two concurrent developments with regard to the European understanding of the concept of the Malay thus came together. The first was the widening of the term to include not only the descendants of the old Sultanate of Melaka, but most of the population of maritime Southeast Asia. This development, as we have seen, was due to an increased appreciation among eighteenth-century Europeans of the importance of Malay as a lingua franca throughout much of Southeast Asia. The tendency was reinforced, following the voyages of James Cook between 1768 and 1779, which led to the discovery of further linguistic similarities across the Austronesian-speaking world and to the identification by Blumenbach of the “Malay” as one of five principal races of mankind (

Bendyshe 1865, p. 275).

The second development was the increasingly negative views of the Malays among European observers, many of whom from around the middle of the eighteenth century began increasingly to link them to treachery, rapaciousness, and a natural inclination to piracy. In part such descriptions were based on the increase in maritime raiding in maritime Southeast Asia—most of which emanated from the southern Philippines, although raiders were also based in other parts of the archipelago, including in the Strait of Malacca (

Warren 2002;

Tarling 1978)—but it was also linked to the more assertive European commercial interests in the region, particularly on the part of the British. In a global perspective, moreover, the more negative assessment of the Malays was part of an increasingly negative European view of unsettled, non-agricultural peoples, including both nomads and costal populations.

These two developments became entangled in the second half of the eighteenth century, and were subsequently, during the following century, combined with notions of race to create a persistent European image of the Malays as natural and inveterate pirates. This notion, in turn, served as a convenient pretext for European colonial and commercial expansion in Southeast Asia during the nineteenth century and purportedly justified large-scale brutal anti-piracy operations, in which whole villages were attacked and burnt to the ground, often resulting in hundreds of casualties and including women, children, and slaves (

Amirell 2019).

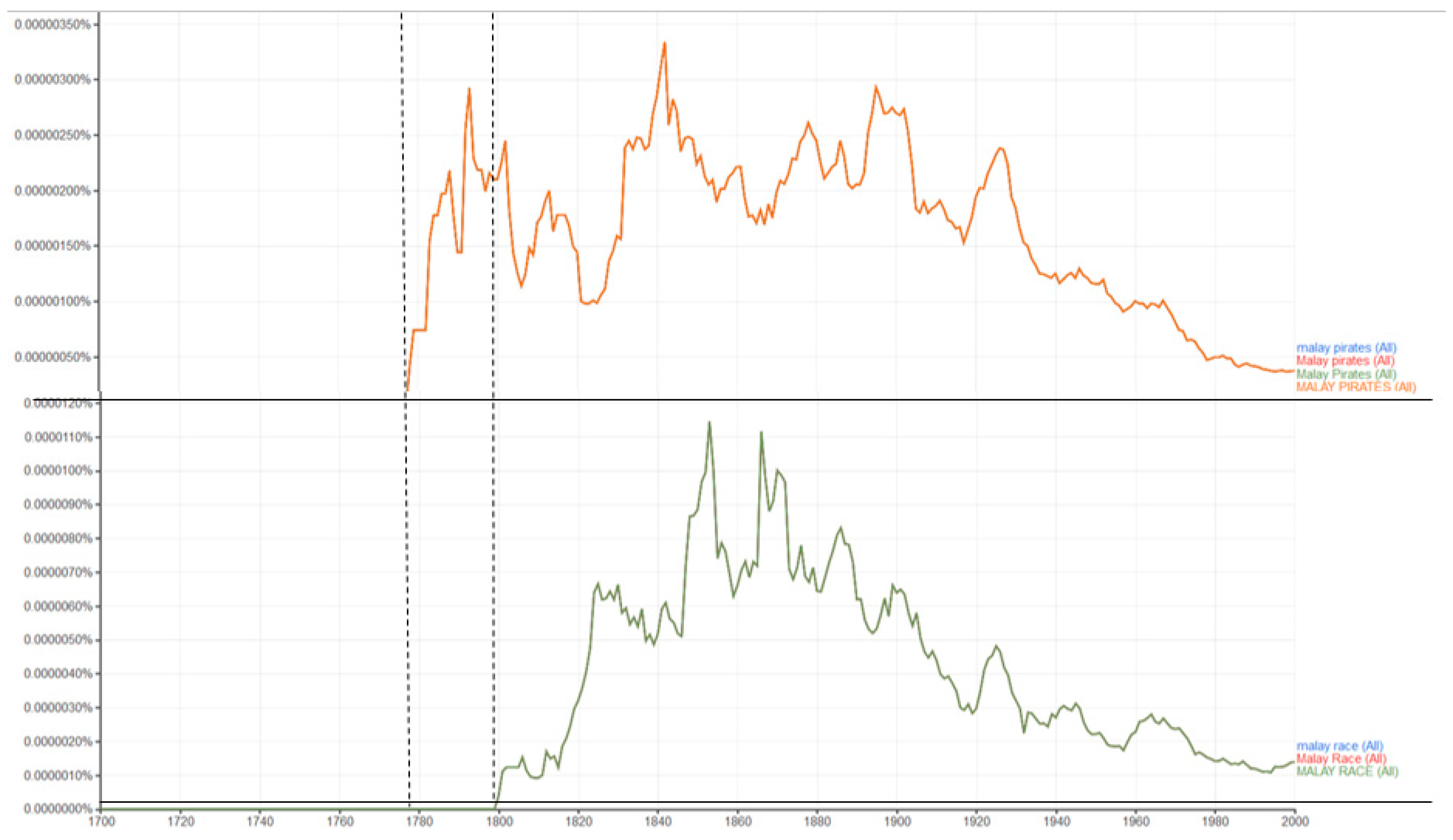

Such atrocities are sometimes seen as a consequence of the racism that accompanied nineteenth-century European imperialism. However, although there is no denying that racism and colonial violence were closely associated, the casual connection is less clear. The trope of the Malays as inherently piratical preceded the notion that the Malays constituted a race or variety of mankind. The chronological sequence of the appearance of the terms “Malay pirate” and “Malay race” is illustrated by a simple text mining search based on the English corpus available on Google (

Figure 2), which corroborates the result from the investigation in general.

European, purportedly scientific, racism as it developed from the mid-eighteenth century onward did not initiate the process by which the scope of the term Malay was first extended and then increasingly associated with piracy and other forms of rapacious behaviour. The negative stereotypes rather preceded and probably influenced European theories and notions of race with regard to the Malays. The process is similar to that described by

Buchan and Andersson Burnett (

2019b) in relation to European perceptions of the indigenous population of Southern Australia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. In their study, Buchan and Andersson Burnett demonstrate how the long-standing notion of savagery among European observers was re-inscribed by race and, as such, was increasingly linked to physical properties and the idea that humanity could be classified in different races or varieties. This study shows that a similar process occurred around the same time with regard to the notion of piracy and rapaciousness, which became closely associated with the Malays, who now were understood by Europeans as comprising most major ethnic groups in maritime Southeast Asia.

5. Conclusions

This present study has demonstrated how the term Malay originally was understood by European visitors to Southeast Asia in a limited and, for the most part, positive way and was used in principle to refer to the people and language of Melaka. For around two centuries, from the early sixteenth until the early eighteenth century, Europeans tended to describe the Malays in mostly favorable terms, and they were generally not associated with piracy or violence, treachery, rapaciousness, or the like. To the extent that such claims occasionally were voiced, they were for the most part downplayed or explained with reference to exploitation or oppression by other Europeans, such as by the Dutch in the Dampier’s account, or limited to certain specific ethnic groups in maritime Southeast Asia. Early European observers thus recognized that maritime raiding was a common practice in the region. Such activities, however, were generally associated either with the activities of other European navigators in the region or with other indigenous ethnic groups than the Malays, such as the Celates, Bajau, or Makassarese.

This largely favorable European image of the Malays changed in the course of the eighteenth century. First, the understanding of the Malay nation was extended and came to be understood as comprising most of the indigenous population of maritime Southeast Asia, particularly the large groups of people who inhabited the agricultural lowlands and the coastal regions. Second, markedly more negative views of those who were accordingly defined as Malays gained influence from around the middle of the eighteenth century. The French naturalist Pierre Poivre’s description of the Malays as possessing a mean and treacherous character and being addicted to piracy, first published in 1768, was widely read throughout Europe, and became influential, despite his obvious lack of in-depth knowledge of Southeast Asia or of Malay culture and society. Fifteen years later, the British historian William Marsden published his, in the long run even more influential, History of Sumatra. Marsden largely concurred with Poivre’s negative views of the Malays as addicted to piracy and ferociousness.

The late eighteenth to early nineteenth century was in many ways a transitional period, during which competing theories and arguments with regard to the variety of mankind were presented, stimulated by the increasing amount of observations of non-European peoples and their cultures by naturalists, explorers, travelers, merchants, missionaries, and others. More positive descriptions of the Malays were still published during the last decades of the eighteenth century (and later), particularly by British country traders in the region. However, the analyses of respected scholars, such as Poivre and Marsden—and subsequently, in the nineteenth century, Raffles and Crawfurd—were more influential in the long run.

The consequence was that image of the Malay as an inveterate pirate was cemented in the decades around the turn of the nineteenth century. Particularly during the nineteenth century, the alleged Malay addiction to piracy came to be understood as a racially defined characteristic, shaped by structural factors such as climate, geography, history, culture, and religion. Such explanations for piratical behaviour stand in sharp contrast to the actor-driven and individualistic explanations of the European pirates who ravaged in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean during the so-called Golden Age of Piracy a hundred years earlier, as well as to the generally positive image of the Malays in the writing of earlier European observers.