1. Islands, Peoples and Whales

“Um rugido constante e fragoroso/Vem das praias e espalha-se no ar…/São as ondas do mar a soluçar/Um cântico magoado e misterioso”

“As Ondas” (The Waves), poem by Jorge Barbosa 1929.

The historical understanding of the ocean, the coastal waters and the open seas is a context-based one; it is grounded, simultaneously, on ecological and cultural realities. Civilisations think about the ocean and the interface between sea and land in very different ways, and the same happens with the limits or boundaries of continents and islands. For islanders, islands were connected to the sea around them, and were not perceived as small or insular; they were/are the centre of the world. For instance, to Pacific worldviews, islands were firm ground and the ocean the corridors that connected them. On the contrary, for societies living on landmasses, the sea was a void rather than a place, and what they perceived from their continental perspectives as islands in the far sea appeared small, remote and isolated whatever their size or proximity (

Gillis 2007;

Gillis and Torma 2015). These contrasting understandings of islands should not obscure the degree to which something like a sea of islands once existed in the Atlantic itself. And when historicising the Atlantic one can also discuss if islanders viewed it as a large sea full of places to explore and to inhabit, connected rather than divided by water (

Hau’ofa 1994;

Gillis 2007).

During the early modern period Atlantic islands were closely connected with one another and constituted a world of their own, supporting maritime imperial developments at the leading edge. For the first Iberian explorers of the open ocean in the early 15th century, as a network of islands and archipelagos started to emerge in the Atlantic and to be culturally constructed, these places started to be perceived as small hotspots in the middle of a blank ocean (

Santana-Pérez 2018). From an environmental history perspective, in the context of the European expansion, islands can be reflected as laboratories where pilot-programs of labour, plantation and domestication of natural products were tested and developed (

Crosby 1993). Atlantic islands were crucial points of support of the Iberian empires, becoming activity centres of complex commercial networks that connected Europe with Africa and the Americas, through the circulation of people, plants, animals, techniques, cultures and ideas, depending on decision centres very distant from the islands which conditioned the histories of these islands (

Flores 2015;

Santana-Pérez 2018).

The historical foundations and development of a settlement—either a coastal village and a seaport, or a maritime society—shape cultural scenarios and the local and regional relationships of individuals and communities with the ocean and marine animals. Native people, colonisers, continental or insular societies with more or less relation with the sea were, however, shaped by its own nature. This is because the ocean is not a mere space of navigation or the scenario of history but instead a dynamic element with its own life from which humans had been extracting and using resources and services and that has, simultaneously, shaped human cultures as an agent of historical change (

Mack 2001;

Bolster 2008).

Here, we are addressing the whales-humans relationships to deepen the construction of a shared history in Cape Verde. The historical foundations and development of the Cape Verde Islands, in the Eastern Atlantic, from a former Portuguese Atlantic colony to a recent independent country since 1975, are intrinsically connected with the sea. The ocean, the shores and the connection to the hinterland has shaped the archipelago’s own social and cultural scenarios as well as the local relationships with the marine environment and its animals.

Whales—sometimes also in ‘representation’ of other large marine animals—are paradigmatic to the understanding of the connection of peoples to the ocean, and they are embodied in the history, folklore, literature and poetry, and the material and immaterial heritage of different coast-dwelling societies across time. Historically, as whales inhabit—or share, during the course of their long-distance oceanic pilgrimages—the same coastal regions inhabited by humans, they have always been sources of food and fuel, mythological and literary figures and, finally, symbols of human ruthlessness and ecological endangerment (

Richter 2015). Exploring the shared coexistence of people and whales allows us to discuss and reformulate oceanic histories and transforms our views of events, reshaping traditional geographies and unraveling non-human historical actors (

Jones 2013). Amongst the animals better known across human cultures and times, there is the whale. Even if the animal itself was not clearly recognised at each time and by each society, one can find the large fish and the sea monster represented in multiple forms of art and science—painting, sculpture, poetry, literature, music, cinema as well as in natural history and philosophy, zoology and anatomy, history and archaeology, conservation and genetics (

Richter 2015;

Brito 2019;

Brito et al. 2019).

The whale, the large marine mammal, still attracts crowds of people when it strands nowadays on nearby shores or when spotted on the horizon. As recent investigations has brought to light, the whale allows for a close connection of people with the strange, enormous, ambivalent, still much unknown, ocean (

Brito et al. 2019).

Thinking seascapes as confluences of land and sea, of the tangible and the intangible, and as the framework to investigate maritime peoples, environments and dynamics (

Bentley et al. 2007), in this paper we will address historical and recent encounters with whales, and how those encounters influenced different versions or perceptions of the Cape Verdean sea. We will base our analysis in historical documents, artistic pieces, literature excerpts and animal bones. We will try to understand the whale as an element that connects the sea to the land, and as a ‘place’ of convergence of multiple perspectives and interpretations—the whale as a target, as a subject and as an actor in the building of a common story. In short, we expect to understand the value of the whale in the construction and perception of the archipelago’s maritime history and heritage.

2. The Whale in the History and Literature of Cape Verde

Cape Verde is an Atlantic archipelago (

Figure 1) composed of 10 islands and 5 islets of volcanic origin with steep shores, an ocean floor more than 3000 meters deep, and in their surrounding waters occur deep diving cetaceans, such as sperm whales (

Physeter macrocephalus), blackfish (pilot whales, orcas, and other species) and many other different species of delphinids. Plus, baleen whales such as the humpback whale (

Megaptera novaeangliae) migrate annually between high-latitude feeding areas in the North Atlantic to low-latitude breeding areas which include the waters of Cape Verde, totalling 24 species occurring in the region (

Reiner et al. 1996;

Brito and Carvalho 2013;

Berrow et al. 2019;

Wenzel et al. 2020).

In the shared history of people and whales, whaling has been an impactive activity with consequences for both humans and animals. As Michael

Dyer (

2009) wrote, islands loom large in whaling history, and to this the Cape Verdean Islands are no exception.

Despite some studies that have pointed out the existence of local whaling in the 16th century (

Ellis 1969;

Hazevoet and Wenzel 2000), it has been hard to track the evidence of such activity in the region during the early modern period. The coeval travel literature confirms the occurrence and abundance of whales of

“incredible magnitude”, on one occasion most probably a humpback whale due to its description of a

“large back and superior body that was greatly curved and prominent” (

Figueroa 1624). It was possible that such large animals, when stranded on the coast, were used by local people and their meat was included into their diet as a rich source of animal protein (

Brito et al. 2016).

It seems that, as early as 1732, the production of whale oil and the payment of associated taxes were already legislated in the islands of Boavista, São Nicolau and Santo Antão, and English whaling vessels were permitted to anchor in the harbour of Tarrafal (São Nicolau) (

Carreira 1983; see also

Cabral and Hazevoet 2011). In 1761, the General Ombudsman of Cape Verde wrote to the Portuguese king, D. José I, regretting that in front of such abundance of whales in the waters around the island of Santiago, the exploitation of these animals was left to foreigners. In the same year, another letter was sent pointing to the abundance of fishes in the island of Boavista, and particularly of whales, that should justify the establishment of the whaling activity and a factory to produce oil much needed in difficult times of lack of resources (

Matos 1761). In 1771, other communication of the Governor of the islands highlighted the advantages that could be taken with the establishment of whaling in the canal between Santiago and Fogo (

Lobo 1771).

While the abundance of whales—and their potential exploitation—triggered the intention of establishing a whaling activity in Cape Verde as a profitable business for the Portuguese Crown, this economic enterprise was almost exclusively pursued by English and American whalers. In 1787, the Governor of Cape Verde stated:

“(…) through this Islands many whales are going South. I have seen them many times inside this Port (…). The Foreign Vessels, that go to the Cape Horn, and the Cape of Good Hope, first rehearse in this vicinities; and I who do not dismiss every news knew that last year they caught up to 50 in the islands of Sal and São Vicente”.

The potential development of this business by the Portuguese Crown, supported by a marine living resource, was instigated by officers and by naturalists. Throughout the second half of the 18th century, a new scientific worldview and intellectual movement was evolving in Europe; one that promoted scientific voyages that crisscrossed the oceans, collecting specimens of fauna and flora that also served as valuable commodities, gathering collections of naturalia and ethnographic materials, descriptions an drawings (

De Vos 2007;

Bleichmar 2009; see also

Delbourgo and Dew 2008). Within this Enlightenment context, natural resources with economic potential also caught the attention of scholars keen to promote Portuguese expansion and economic profit.

Very well prepared expeditions with a naturalistic character, called philosophical voyages, were promoted in Africa and American regions in the late 18th century with the goal of assessing the richness, usefulness and value of natural resources of the Portuguese Empire and to record and collect samples of fauna and flora (

Simon 1983;

Domingues 2012). The expedition led by the naturalist João da Silva Feijó to Cape Verde lasted from 1783 to 1796 (

Roque 2013). In his written documents the author noted the abundance of whales, sperm whales and dolphins of which “

English, Americans and French whalers ordinarily take advantage, fishing them in sight, and inside our ports, where they come to prepare our, or rather their, whale oil” (

Carreira 1986). In the

Economic Memories of the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon, the Italian Domenico Vandelli (professor at the University of Coimbra between 1772 and 1791 and promoter and later director of the Royal Botanical Garden of Ajuda in Lisbon) wrote about the under-exploitation of whales in the Portuguese territories of America and Africa, urging to expand this business to Cape Verde (

Vandelli 1789; see also

Vieira et al. 2020). Also, the Brazilian naturalist and politician José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva reflected about this issue, writing:

“In the Islands of Cape Verde, where a large number of whales beach, the [whaling] Contract should establish whaling stations that could be well supported, and with few expenses, by the locals who are rather smart and skillful at maritime labours: even more so if they could at the same time take advantage of other types of fish that are in abundance there”.

However, in the second half of the 18th century, the Portuguese Crown’s whaling monopoly only extended to Brazil where, in four main areas along the coast, whaling stations had been established, whales were hunted and their products were valued, such as whale oil and baleen (

Vieira 2018). And apparently, no other region of the Portuguese Empire had the chance to establish an organised whaling business, at least until 1801. By the mid- and late 19

th century a local shore-based industry was promoted on some islands, with the focus on the island of São Nicolau, through the creation of whaling companies and the establishment of whaling stations on the shore, an operation that continued well into the 20th century (

Hazevoet and Wenzel 2000;

Cabral and Hazevoet 2011). Nevertheless, the history of local whaling in Cape Verde is still to be unravelled in depth.

Even so, it is clear that whales became part of an early story. The islands of Cape Verde were, since the first half of the 18th century, a strategic stopping point for whaling crews, facilitating the navigation of whaling vessels between the north of America, other Atlantic islands and whaling and sealing grounds in the South Atlantic. The significance of these islands in the whaling history was illustrated in the phenomenal panorama

Grand Panorama of a Whaling Voyage Round the World, executed by the painter Caleb Purrington and the artist and whaler Benjamín Russell in 1847–1848 (see

Dyer 2016). Through this itinerary of American Whaling one can find global maritime scenarios and notable scenes of places and activities. On the

Panorama the seascape of São Nicolau, Sal, Santiago (

Figure 2), Fogo—in its all severity when in 1847 the volcano erupted (

Figure 3)—and Brava (

Figure 4), were depicted. The visual impressions of these coastal landscapes leave no doubt about the significance of the islands in the route of the vessels on whaling voyages and, consequently of their primary importance to whalers.

1 Whaling brought a vast number of American vessels to the islands that served as supply points for fresh water and food and promoted an opportunity for the crew of those ships to interact with the islands’ inhabitants. The anchorage in the Cape Verde ports allowed the crews to rest, to store supplies and to recruit new whalers (

Reeves et al. 2002;

Dyer 2009). Cape Verdean men started to be hired to work aboard the ships, they became experienced and competent whalers and soon earned a reputation of being good at what they were doing. The first ones to be employed came from the islands of Fogo, S. Nicolau and Brava. About the men from this later island it was written that

“beside good workers of the land a lot are very gifted to life at sea, and become excellent sailors, and a lot are in the fishing of the whale with the Americans and the English who pay them well, and are esteemed by them” (

Lima 1884).

The islanders shipped in search of adventure but mostly pursuing an idea of a better life thus providing hope, a way to surmount the daily adversities (of life on the islands), although without knowing exactly what a whaler’s life was all about (

Carreira 1983). This started with the punctual recruitment of a few men and then developed into quite a number of people departing from the islands, living and working on whaling vessels and later establishing themselves and their families in the United States of America. From the 18th century onwards, but largely during the following century, the recruiting of Cape Verdeans to work in the whaling industry resulted in the exodus of a great number of Cape Verdeans seeking better conditions and subsequent upward social mobility (

Luz 2013).

This social dynamic induced by whaling is reflected in Cape Verdean literature. In the novel

Chiquinho, Baltasar Lopes da Silva (1907–1989) bears witness to the frenzy caused by the arrival of a whaler, an event that denoted abundance, the manifestation of the residents’ desire to be recruited, and the disembarkation of some locals who took advantage to visit their relatives:

“The whaling ships arrived. The news spread immediately. Whaling vessels meant abundance for the island. The boys (of the island) got excited because they all wanted to be recruited […]. Those in charge of recruiting were inundated with petitions, for the number of crew members that the ships needed was inferior to that of the applicants. Many boys who were part of the crew disembarked to see their families”.

The author Jorge Barbosa (1902–1971) also gives attention to this subject, speaking of these “Americans” returned whooping, which brought tears of happiness to their relatives and friends, who received them with fireworks. However, this joy was short-lived because they would leave again, in search of economic prosperity. This time, they left tears of sadness in the people who had received them with joy, and they left with different yearnings, especially of the

mornas2 of Eugénio Tavares (1867–1930), as illustrated in the following passage of the poem “

Ilhas”:

“–Seló… Seló! …/Americanos arrive …/In the clamour of the dock/there are tears of joy, elusive crystals/illuminating the eyes of the women …//fireworks/exploding in the air all over Brava/infecting the harmony/of the colours/and flowers/of the delicate gracílima landscape.//And then … they leave/again,/woefully, the emigrants …//: America!! Vast sea!/Distant loves,/Creole yearnings/for the mornas of Eugénio!”.

Although the crew of those whaling ships had more economic power than the locals, they were not admired as much as the “Americans” who worked in the factories and plantations. In the local imaginary, the latter earned good wages, a fact that gave them, upon their return, some economic clout, and they were admired by everyone. Those hired by the whalers worked many months in the South Seas in spite of a low salary (

Silva 1993).

Despite the economic differences that existed in certain situations, work on those ships was of fundamental importance for improving the lives of many Cape Verdeans. The migratory flow generated a process of family reunification that was re-established in different American cities, especially in New Bedford, where Cape Verdeans also found opportunities to work in rope factories, in agriculture, as well as being hired as coastal labour and in textiles. In his description of the recruitment of workers for the ships

Wanderer and

Morgan, Baltasar Lopes da Silva mentions the character Antoninho de nh`Ana Lanta, who was downcast when he couldn’t get a job:

“We went to cajole the recruitment, which was done in the Council Administration. The person in charge was assisted by two crew members, one of them with very white eyes. He distributed the boys among the ships:—This one is for the Wanderer boat. You go to the Morgan. I also remember the sad face of Antoninho de nh`Ana Lanta when he didn’t get a job. He was condemned to spend his life at the handle of a hoe. I felt sorry for his tattered trousers that had no place for more patches. Antoninho and those who had been rejected would continue to earn a few pennies a day, toiling in the vegetable patches”.

The sea was responsible for the realisation of these goals, since it was the route used by the “little boats” in their itinerary towards the United States. However, ships did not always reach their destination. Hence, when a traveller departed from the islands, he left longing and “prayers on the lips” of family and friends, since many were the “brothers” that never returned as a result of the adversities they encountered, both hunting wales and during the transnational voyage. We detect, therefore, a sea-challenge, as noted in the poem “

Irmão” (Brother) by Jorge Barbosa, where he refers to the lives of some of those who emigrated and worked in whaling, which calloused their hands and exposed them to the danger of the sea (

Luz 2013). There were also those who worked in the furnaces of the ships, feeding them with coal:

“You crossed Seas/in the adventure of hunting whales,/in these voyages to America/from where sometimes ships never return.//Your hands calloused from pulling/the rigging of the little boats in the open sea;/you lived hours of cruel anticipation/in the struggle against storms;/you endured the tediousness of the sea/the long interminable lulls”.

The author shows an ambivalence in Cape Verdean society and its state of mind, a result of the departure of part of the population to the United States pursuing the idea of a better life in contrast with the hard work and living conditions.

Whaling compelled the departure, required ability and courage and provided a consequent improvement in the standard of living of whalers and their relatives who remained in Cape Verde, due to the remittances they received. We can conclude that the whaling activity had a decisive impact on the constitution of the Cape Verdean diaspora, evident in the Cape Verdean-American community and immortalised in the pages of Cape Verdean literature.

What we came to understand is that the whale, the animal itself, leaves few traces of its history but can be spotted by the human eyes in the multiple surfaces and interfaces of nature and culture.

3. The Whale in the Cape Verdean Local Art and Heritage

Together with the construction of narratives about whales, it will be around the seascape and the littoral space that material and cultural traces of the connection of people with the sea are revealed. Places names like “

Porto”, “

Baía” or “

Angra” (respectively, the Portuguese words for harbour and bay) evidence the long time usage of sandy or pebble beaches where traditional small boats are, still nowadays, laying, in front of the urban areas usually parallel to the sea. Communities that live by the sea use these sheltered bays for their fishing activities, as has been the case for the development of portuary activities since the island was first settled (

Garcia 2017). During a walk by the seashore in Porto Rincão (Island of Santiago), one can find the inscription “

Anca Baleia” in a street wall, referring to a rock formation resembling the back of a whale (

Figure 5).

Whales inhabit exclusively the ocean and when they are hunted and brought ashore their meat and blubber are consumed or entirely decomposed, leaving few but remarkable evidence of their history, both in the physical and cultural landscape. This transformation of the material space in Cape Verde is worth mentioning in a particular place, nested in the North of the island. It is called Rabelados.

Until very recently, in the small village of

Rabelados—a somewhat closed, traditional community—it was still possible to buy whale-bones handicrafts made by local artists. This community, evolving from a former ‘

quilombo’ (a place of past refuge of African slaves) still inhabit traditional homes, made of stone and thatch. More importantly, they are mostly isolated and apart from the current way of living in Cape Verde, and they manage to live from agriculture, fishing and, more recently, from handicraft as a practice that resulted from an encounter with an artist living abroad (

Hilton 2016). It is said that these local artisans used to gather whale bones by the nearby beach and use them as raw material, making use of what nature was providing and making sure that the connection with this same nature prevailed in their works. The traces of the relationship with whales arise through art, both in the form of sculptures and paintings, showing the

Rabelados’ daily life and ways of being. Art pieces are produced by the community artisans and sold in a cooperative artistic collectivity called

Rabelarte,

3 which is nowadays more open to outsiders—both Cape Verdean and international tourists. Here, we will find a social universe that moves in between past and present and tries to integrate the members of this community in a more inclusive future (

Hilton 2016). The production and sale of these artefacts is entirely local, and the products are not exported, even though some pieces do travel far and wide by the hands of tourists. These craft objects are desirable not because they are a memento of an endangered species or charismatic megafauna such as whales—more so because today the raw material is essentially cow bones—but due to its intrinsic artistic value and connection to this small community. All the revenue reverts to the

Rabelados community, who are looking at sustainable tourism as a path of change from their past very traditional and closed ways of living. Art and the sea might very well be the way to do it.

For its beauty and singular features, one cetacean vertebrae entirely painted by the local people was modelled by photogrammetry in a 3D representation (

Figure 6), as a case for the study of the tangible maritime culture of Cape Verde.

Whale remains can also be found as decorative elements in other houses across the islands of Cape Verde and bones of stranded, captured or by-caught cetaceans are used as forms of local art and handicrafts (

Brito and Carvalho 2013). Several bones of whales and other marine megafauna can be found in the facade of buildings or inside different rooms as decoration. One other example is the ornamental carved piece of bone in the shape of a moray (

Figure 7), exhibited in the Museum of the Sea in Mindelo. Currently this bone is a museum piece, but prior to that it might have had its own purpose, either an object of use, decoration or an artistic one.

This museum also displays in its collection one whale mandible, one remain of the animal that is often used as a lintel in traditional houses of fishing villages. The utilisation of whales’ bones for practical and prosaic purposes was and still is a common transversal practice in different times and geographies around the globe including several regions in Africa (

Redman 2014,

2019). Back in the 18th century, the naturalist João da Silva Feijó left in the Island of May a pile of shells collected in the beach together with “some skeletons, and skulls of large marine animals” (

Feijó 1783). Actually, the remains of stranded whales and other cetaceans are incorporated in the Cape Verdean daily life, and their transformation and adaptation into useful or artistic pieces reinforce the connection of people to the sea and the multitude of uses for marine life, from food to tools.

Cape Verdean museums are trustees of the whaling legacy, keeping memories and objects in their collections by showing and disseminating this closeness between people and whales, whaling legacy and the associated material and immaterial culture. As spaces of promotion and protection of the Cape Verdean maritime cultural heritage, the Museu do Mar (Museum of the Sea), the Museu da Pesca (Museum of Fisheries) and the Museu de Arqueologia (Museum of Archaeology) have at their core the importance of the sea as a structural element in the development of the archipelago. The Museum of the Sea inaugurated in 2014 in Mindelo (island of São Vicente) has in its core the maritime vocation of the city and its relevance in the structural basis of the local culture. A myriad of themes are patent in museum exhibitions, guided tours, dissemination and educational activities such as the discoveries of the islands; the geography and its influence on the European settlement; the creation and importance of Porto Grande in the city formation; marine biodiversity and the sea as the support for maritime professions; cultural manifestations related with the sea in music, literature, religious celebrations and other festivities; and the whaling activity and the emigration of Cape Verdeans.

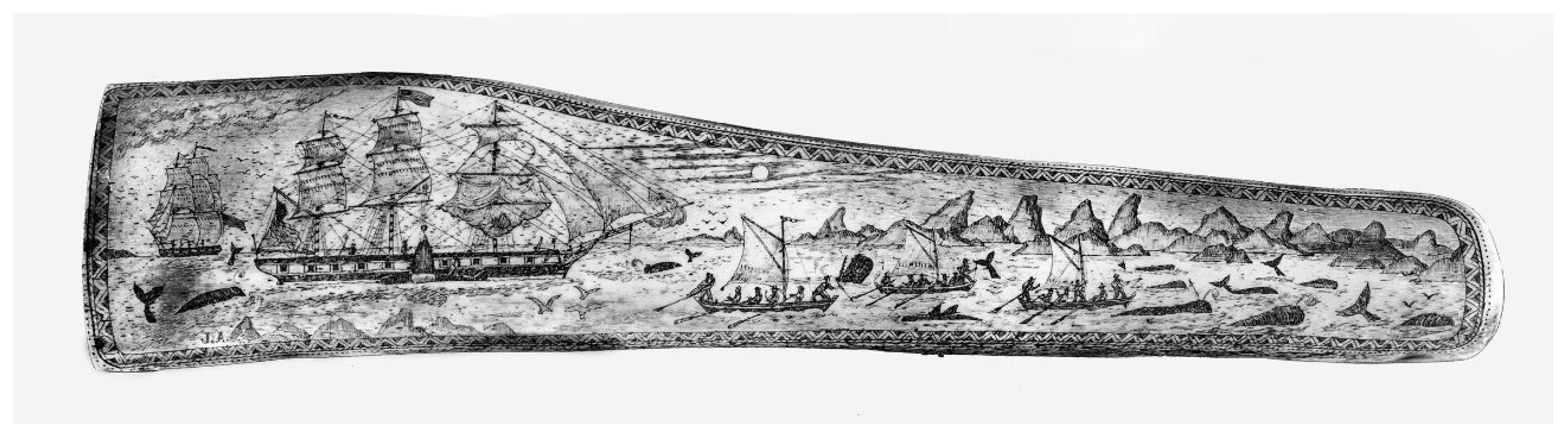

A temporary exhibition was held in the Museum of the Sea, between 2014 and 2019, with pieces and content displayed in partnership with the New Bedford Whaling Museum. A scrimshaw art piece

4 was offered by the American museum in celebration of the Cape Verdean emigration to the U.S.A. related to the whaling industry and the shared maritime cultural heritage (

Figure 8).

At the Museum of the Fisheries, the exhibition

“A caça à baleia nas águas de Cabo Verde” (Whaling in waters of Cape Verde) was launched in 2019 with a joint curatorship of the Museum and the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Here, whales’ bones, hunting harpoons and several other objects related to whaling practices, enriched by photographs of former Cape Verdean whalers, used to be on display. The abovementioned American museum also provided informative panels and a replica of the whaling ship

Ernestina, the last sailing ship to carry immigrants, in regular service, across the Atlantic to the United States (

Miscellaneous Parks and Bureau of Land Management Measures 1995). Simultaneously, the New Bedford Whaling Museum hosts the permanent “Cape Verdean Maritime Exhibit”,

5 highlighting this long and strong relationship sparked by the whaling activity and the close connection between Cape Verde and the U.S.A. that is patent in both countries’ museums, memories and heritage.

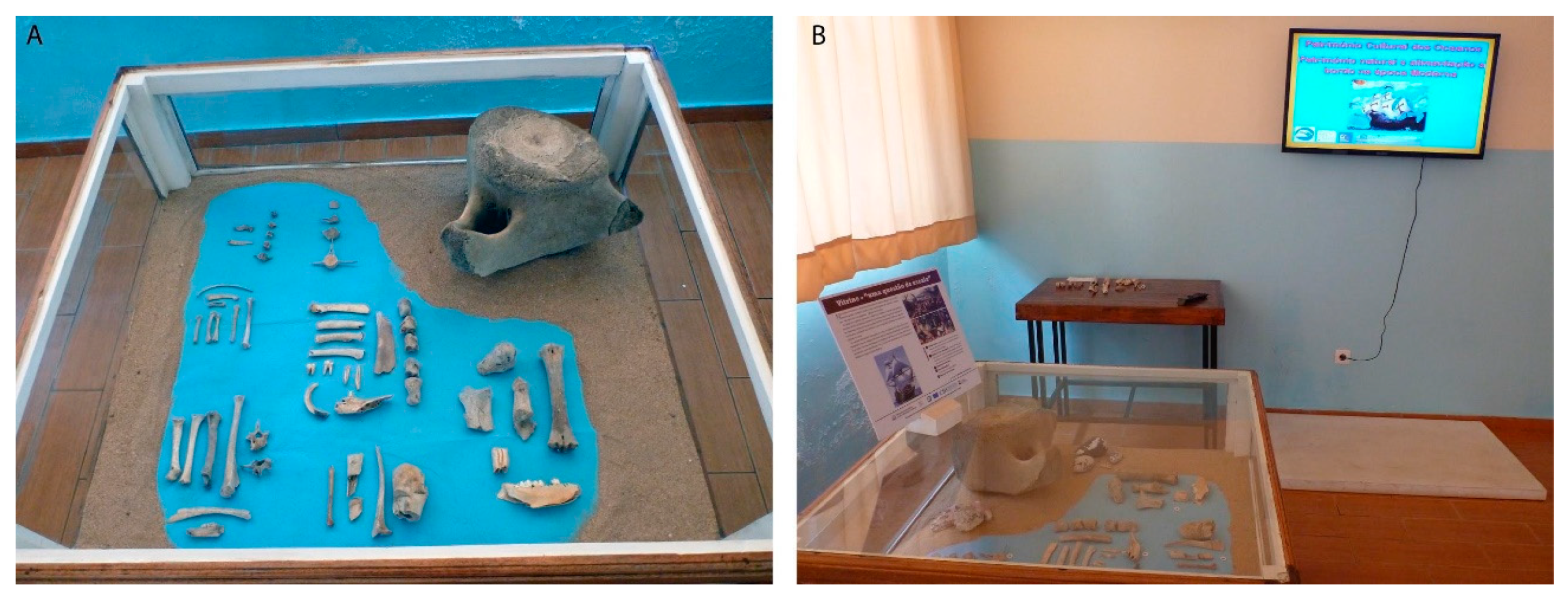

In 2018, during our survey at the Museum of Archaeology (island of Santiago) we identified a collection of bones where, among terrestrial mammal bones, there were also identified dolphin vertebrae and a whale vertebra. All these bones were assembled to integrate a showcase “

Uma questão de escala” that was set in the Museum (

Figure 9). The purpose was to present part of the osteological collection of the museum related to the natural and archaeological heritage, revealing information about the life habits of former seafarers, including the feeding habits onboard, and unravelling several stories from the past that were also shaped by marine animals. This initiative has since then been accompanied by educational service activities where children could be involved with these natural archaeological and heritage materials, being introduced to maritime history and life on board through the remains of marine animals that were deposited in the archaeology museum.

Other representations of whales and whaling instigate a future and deeper analysis and understanding of the collective memory of the Cape Verdean society regarding these animals, such as the collection Cycle of the Whale (

Ciclo da Baleia). Produced in 2006 and 2007 by the Post Office of the country, this is a two-series stamp collection including a total of eight stamps dedicated to whaling. As can be seen in

Figure 10, four stamps illustrate whales’ species, whaling scenes and methods, constituting a materialisation of the intangible cultural heritage and its valorisation in the collective memory.

An artistic approach is also ongoing in close contact with the population towards its iconographic record through individuals’ portraits and the photographic record of maritime landscapes, evocative evidence of sea life and related activities.

6 These themes of study are now being addressed, aiming to provide new perspectives of historical enquiry with interest at national and international levels, and these can be used in further, comparative approaches to insular phenomena (e.g.,

Nolasco (

2019) concerning artistic representations of islandscapes in Azores). Plus, museums are better showcasing the objects in their permanent exhibitions, diversifying the approaches in their temporary exhibitions, and extending their activities to the public in ways that prove the importance of the maritime cultural heritage and its safeguarding.

It is expected that further work can be done in the next few years within the ongoing European project CONCHA—The construction of early modern global Cities and oceanic networks in the Atlantic: An approach via Ocean’s Cultural Heritage.

7 The project aims to contribute to the study of different ways of port cities development around the Atlantic (15th–18th centuries) in relation to differing global, regional, and local ecological and economic environments. In this sense, national and international networking and research projects are paying attention to the importance of Atlantic islands in a global maritime history approach, and Cape Verde has a great potential as an interesting and rich case of analysis. Moreover, marine environmental history, the blue humanities and the intertwining of different fields of the humanities and social and natural sciences will be central in future studies, as will the relationships between humans and the rest of nature.

4. The Construction of the Seascapes of Cape Verde

The sensations of the ocean touching the shoreline is a vibrant echo of eternity. Every thinkable connection between land and sea is a condition and opportunity to be explored and explained in time and space.

Bo Poulsen, Environmental Historian, on Twitter

In this study, we are arguing that the whale, as a symbolic and real ‘place’ of existence, might be a central element in the construction of seascapes in the Cape Verde Islands, should be recovered from collective memory and used as a symbol of nature conservation and of cultural heritage preservation.

Most human encounters with whales and other marine mammals have been mediated by the sea-land interface. When stranded, dead or alive, sea animals are outside of their natural environment but, at the same time, the shores of the world are the place where humans better meet and see these animals. Even when persecuting and hunting whales in the open sea, people needed a place on the coast to get access to energy, supplies or new workforce. These coastal areas became an extension of the sea and of maritime activity, and the consequent transformation of those littoral spaces, either continental or insular, made them true sea places and left a permanent mark in local maritime cultures and heritage. On the contrary, both in the past and in current days, when sighting whales alive at sea—where we can better learn and understand their aquatic ways of living—it is us who are outside of the comfort of firm land.

Whales have a long history of interactions with human coast-dwelling communities and they have been—either real or conceptualised—an element of human fascination (

Richter 2015;

Brito et al. 2019). However, at the same time, whales and peoples’ meetings—as much as the encounter of sea with land—seem to be produced in a constant state of discomfort or displacement and this aspect is reflected in many literary, artistic and scientific productions. Activities such as active whaling, the butchering of stranded dead animals, or the public display and exhibition of bones, show the predatory side of these relationships as well as the ever-present fascination with the large animal. Humans, at the same time, turn towards and move away from the whale. It is in these multiple feelings, perceptions and attitudes towards animals, of respect and cruelty simultaneously, that a complex and dynamic relationship has been constructed between animals and humans which defined and shaped history (

Fagan 2015). The powerful Leviathan, and peoples’ ambivalent reactions of fear or amazement, are represented in Cape Verdean history, literature and memory as in artistic manifestations using (as in sculptures) or showing (as in scrimshaw and paintings) cetaceans. This relationship seems to be shifting nowadays.

Whales and dolphins are becoming a source of revenue in Cape Verde as a tourist attraction through whale-watching, like in other archipelagos where whaling was historically and culturally important (e.g., Azores and Madeira, Portugal (e.g., Azores and Madeira, Portugal) (e.g.,

Prieto 2015)). Cetaceans have been protected in Cape Verde since 1987, by national legislation, although dolphins could be regularly found on the markets and stranded animals found on the shore would be butchered by the population, until very recently (

Hazevoet and Wenzel 2000;

Cosentino and Fisher 2016). A change in practices and attitudes towards these marine animals is gradually happening worldwide, mostly as a consequence of conservation and awareness efforts (

Naylor and Parsons 2018;

Giovos et al. 2019), for which the dissemination of cultural heritage related to the ocean and the whales is also crucial. In Cape Verde, all the environmental, cultural and chronological contexts did, and still do, influence the way people perceive the littoral and seascapes, and today whales are also becoming a symbol of current-day conservation concerns. The construction of a common history of these interactions will showcase the value of the animals in the past as well as its cultural meanings and its ecological importance in the marine ecosystems.

Through our analysis of sources, literature and material culture, it became clear that whales do have a very real—historical and symbolic—meaning in the Cape Verde Islands. By reviewing whales and seascapes through a kaleidoscopic lens of scientific disciplines, backgrounds and expertise, we come to understand the existence of the stranded whale, the hunted whale, the whale in local art and literature, and the whale in culture, heritage and memory. Even if the presence and the agency of marine animals seem to be somehow silenced in some of the historical records and archaeological remains, we argue that they influenced actions and human choices, because whales and people inhabit, explore and share the same space—the Cape Verdean seascape—as prey and predators, as objects of literary production and writers, as pieces of art and as artists.

It was also our aim to highlight here the importance of the marine environment not only as a space of human action and exploitation but as cultural heritage resulting from a long coexistence between systems and species, human and non-human (

Freitas 2020). The littoral of the Cape Verde Islands is a living seascape historically constructed, and today culturally resignified, as a contact zone between the creatures of the sea and those of land, as a place mediated both by sea animals and people.

As environmental historians, maritime archaeologists and photographers, but essentially as individuals, we walked on the shores to observe the ocean and the seascapes. Whales have helped us in our search and reasoning. No doubt, we find here a seascape that—in the past as well as today—is constructed through the presence of whales and the relationships people establish with them. As a result, we came to understand seascapes as the complete environ of the marine interface with land, as a coastal landscape that can be seen and constructed from land to the sea as much as from the sea to land. If we step back from our disciplinary core, this seascape is not just a flat portrait but a space that creates multilayered feelings. It is the ocean surface and all beneath it, it is the sand, the cliffs and the dunes, the seagull, the fishers and the boats, as it is the ruins of human construction, an urban front, as much as a story, a poem, a word, a painting, a colour, a movement, a sound. Not just a geography or a place, but truly an emotional state.