Abstract

Rachel Lichtenstein’s books, along with her multimedia art, represent her explorations of her British Jewish identity and her place in British Jewish culture as an imaginative odyssey. Her work represents research, stories, and traces from London’s Jewish past and multicultural present as well as from Poland and Israel, her family’s accounts, and the testimony of recent immigrants and long-time residents. Lichtenstein is a place writer whose artistic projects subject her relationship to the Jewish past and East End to critical interrogation through a metaphorical method composed of fragments that represent varied segments of Jewish history and memory as well as wandering as a narrative of personal exploration.

1. Introduction

British Jewish cultural life appears to be thriving. According to scholars in the field, because British Jewish artists and writers are no longer afflicted with “reticence and self-censorship born of anxiety and embarrassment”, there is no longer a “need to justify […] the focus on a relatively small minority group in a society and culture still coping with ethnic pluralism” (Kushner and Ewence 2012, p. 6; Gilbert 2012, p. 275). British Jewish culture is no longer invisible, marginalized, or a sub-category in mainstream British cultural production1. Instead, the creative and critical work of British Jews is now a continual presence in various media, reviewed and studied for its illuminating contributions to the nation’s art and entertainment. Nonetheless, public enthusiasm, critical acclaim, new forms of Jewish affiliation, and even “the pleasures and possibilities of diverse and diffuse forms of identification” have not resolved debates about defining British Jewish identity and cultural politics (Gilbert 2012, p. 277).

The vicissitudes of belonging, of being integral to British culture and society while retaining a sense of Jewish difference, remains a subject of compelling interest to scholars of British Jewish history, experience, and artistic representation. With heterodox perspectives, contemporary artists and intellectuals express and study the development of a multifaceted range of British Jewish identities and forms of cultural expression. At the same time, as Hannah Ewence and Tony Kushner proffer, the study of British Jewish history and culture has also moved beyond the nation, directing attention to “global influences in national Jewish cultural production” (Kushner and Ewence 2012, p. 6). In effect, such transnational movement complicates interpretive relationships among British and Jewish and British Jewish identities and cultures. Ruth Gilbert posits that “Where once British Jews articulated anxieties about how they belonged in relation to their Britishness, now they are equally, or even more, likely to express uncertainty about how they belong in relation to Jewishness” (Gilbert 2015, p. 210). Gilbert is optimistic in constructing a flexible and performative concept of “Jewishness” that coincides with “the progressively decentered conditions of twenty-first-century Britain” (Gilbert 2015, p. 210). And yet the fluidity of British Jewish life and identity is also shadowed by a disquieting new take on an ancient Jewish revenant. Susan Shapiro notes the troubling way that “postmodern critics […] perpetuate the Christian tradition of viewing the Wandering Jew as a positive figure of dislocation, thus erasing the real suffering of the Jews” (Shapiro 1994, p. 11). With no irony intended, such postmodern rendering of Jewish displacement recasts an older form of Jewish punishment and suffering: redemption in the form of transcending exile through conversion to Christianity. Buttressed by British Jews’ historical and contemporary experiences of expulsion and migration and expanded meanings of diaspora, recent British Jewish art and writing counterpoise such theological and theoretical mythologizing.

A multimedia example of reconfiguring British Jewish wandering in relation to contemporary British Jewish identity is the art and writing of Rachel Lichtenstein. Considered together, her books, Rodinsky’s Room (co-authored with Iain Sinclair, 1999), On Brick Lane (2007), and Diamond Street (2012), along with her multimedia art, represent her explorations of her British Jewish identity and her place in British Jewish culture as an imaginative odyssey2. She depicts herself as researching and salvaging stories and traces from London’s Jewish past and multicultural present as well as from Poland and Israel, her family’s accounts, and the testimony of recent immigrants and long-time residents. Lichtenstein’s writing falls within the genre of creative non-fiction while she identifies as a place writer. She explains her combination of imaginative and investigative narratives on the first page of On Brick Lane by declaring that she translated her grandparents’ histories of migration and “rich cultural and intellectual life” into a “mythical landscape” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 1). Recalling that her first explorations were driven by a “romantic” search for “the Yiddish-speaking world of my grandparents”, she acknowledges that her “own fantasies and visual projections on to the streets and buildings around me were feeding into this constructed mythology of the place” and that she was both “fascinated and repelled” by the disorientation sometimes induced by an inexorably changing cultural landscape (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 12). Instead, however, of creating a synthesis to resolve her ambivalent responses, each of Lichtenstein’s artistic projects subjects her relationship to the Jewish past and East End to critical interrogation.

As this essay will explore, Lichtenstein’s method of interrogation is metaphorical. Her mosaics, sculptures, and writing are composed of fragments that represent varied segments of Jewish history and memory as well as fluctuating narratives of personal exploration. Ruth Gilbert notes a metaphorical trend in Lichtenstein’s work: “Palimpsestic figurations, in which the traces of previous inscriptions linger within the surface of the present, are an important trope” (Gilbert 2019, p. 215). With various iterations of wandering, Lichtenstein’s artistry charts her evolving British Jewish identity. Susan Fischer’s observation about British women writers as flaneurs lends insight to the relationship between Lichtenstein’s explorations and her art: “London figures as a place to journey towards. For others, discovering different parts of the city becomes a metaphor for finding themselves and a connection with community or for trying on multiple selves” (Fischer 2001, p. 60). The multiple, self-reflexive meanings Lichtenstein assigns her art and writing derive from an indeterminate search and construction of the Jewish legacy she will claim as the pathway to her British Jewish identity. Her multidirectional itineraries explore the unsettled past and present to build a multifocal narrative that expresses her British Jewish identity as an autobiogeographical chronicle.

2. Lichtenstein’s Autobiogeography

Lichtenstein’s work extends and enriches that of British writers who are exploring the byways and undergrounds of the nation’s regions and cities and who have established a genre Christopher Gregory-Guider identifies as autobiogeography, “characterized by viewing the city both as spectacle and as site of spectres from the past [….] All of these works pay tribute to the densely-layered heterogeneity of the city’s history [and] the myriad ways in which the metropolis has been conceived and imagined over time, bear[ing] on private memory and memorialisation, something that is not usually addressed by psychogeographers’ more socio-economic agenda” (Gregory-Guider 2005).

Lichtenstein’s creations illuminate London’s polysemous character by enfolding her sojourns and those of other witnesses into the multicultural history and present of the East End and Hatton Garden3. Considering her writing and multimedia art as intertwined also locates her aesthetics as part of “the ‘spatial turn’ in twentieth-century art” in which, as Neal Alexander observes, “the Cubist technique of collage or montage suggests new forms of correspondence and coincidence, ‘new types of conjunctions and disjunctions’ between objects and ideas” (Alexander 2010). In its temporal and transnational oscillations and variegated forms of cultural expression, Lichtenstein’s work expands the range of interpretive approaches to British Jewish culture by interweaving culturally diverse voices with echoes and material traces of Jewish life and work in London.

Lichtenstein anchors her passion for constructing stories in her childhood, when her father and grandfather, who were antique dealers, would bring home odd pieces that she would imaginatively bind together:

I have always been a storyteller fascinated by the traces of the past that get left behind, whether they are salvaged mementoes from an abandoned building, the fading memories of a rapidly disappearing landscape, or the hidden narrative within a single photograph. […] They rarely had much monitory value but to me they were magical. I remember examining a broken Victorian brass microscope with glass slides filled with pressed butterflies’ wings, a memorial death ring with a lock of braided human hair, tinted postcards from all over the world written in the same slopping hand and an inlaid wooden musical box with ivory keys. My favorite childhood game was to hold these belongings in my hands with my eyes closed and try and imagine who had owned them and where they had come from.(Lichtenstein 2020)

Lichtenstein’s first book, Rodinsky’s Room, is a narrative mosaic composed of remnants of the British Jewish past she discovered in her wanderings through London’s East End. Its catalyst is the story of David Rodinsky, a reclusive Orthodox Jew, who suddenly abandoned his attic room in the Princelet Street synagogue and disappeared. Intrigued by the room’s dismantled state, its shadowy atmosphere, musty objects, and Rodinsky’s esoteric jottings, Lichtenstein becomes obsessed with solving what appears to be the mystery of an obscure life and fate. She consults archives and Rodinsky’s few remaining relatives only to discover that his fate was sad but unexceptional and his character remains inscrutable, like his Cabbalistic diagrams. As though compelled to discover a narrative form to represent Rodinsky’s opaque character, Lichtenstein has a dream in which she conjures Rodinsky as a character in a dark folktale, “a wandering dybbuk”, who “could not shake the bondage of his past” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 219)4. Although this representation of Rodinsky’s character suggests an uncanny determinism, the interpretation does not remain unquestioned. Instead, in all of Lichtenstein’s art and writing, the speculative, “fanciful fictions” of dreams and folktales are set in critical contrast with the testimonies of those who have witnessed the persistent changes that characterize the East End (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 224).

Ultimately, the room, the leftovers of Rodinsky’s life, and their elusive meanings only become intelligible as Lichtenstein translates them into a textual equivalent to her sculptures. That this construction is analogous to Lichtenstein’s search for her family’s past and her evolving British Jewish identity is affirmed by several commentators. Iain Sinclair proposes that Lichtenstein “nominated the story of David Rodinsky as a way of discovering (or creating) her own past” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 85)5. Susan Fischer posits that Lichtenstein’s “passion is necessarily autobiographical, not only to learn what became of David Rodinsky, but to find herself and her creative vision” (Fischer 2001, p. 128)6. Countering criticism of Lichtenstein’s mission, Brian Baker argues, “Not that Lichtenstein uses the figure of Rodinsky in a cynical or selfish way, but that the narrative of ‘discovery’ [is] necessarily a kind of self-examination and self-fashioning” (Baker 2007, p. 111). Lichtenstein’s self-reflexive narrative leaves Rodinsky’s character and her self-fashioning unsettled, as though to complete them even imaginatively would deny the integrity of his elusiveness and the fluidity of her explorations.

3. Traces of the Past

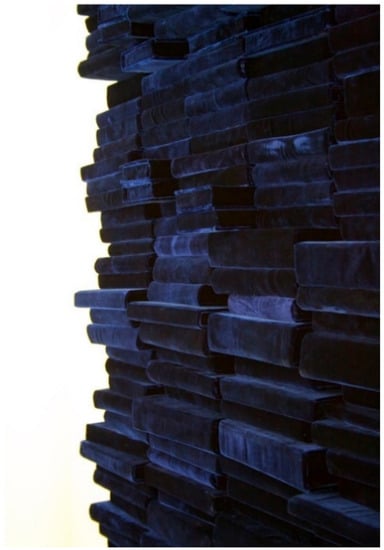

Commingling postmodern and traditional frames of reference, Lichtenstein narrates her journey as crisscrossing time and space, inspired by her grandfather’s history and including Holocaust sites, Israel’s manifold cultures, and the stories relayed by the East End’s multivocal residents. Her identification with the Jewish past and Judaism’s formal structures is aspirational. She immerses herself in Jewish mysticism but opts out of converting to Orthodoxy to be free to wander among and draw upon a range of Jewish traditions and histories. Instead, however, of reaching an endpoint or ultimate choice, Lichtenstein’s Jewish pilgrimage enacts but also revises an old story, summarized by Rabbi Lea Mühlstein: “a desire to emphasize the Jews’ historical fate of being a wandering people” (Mühlstein 2020, p. 29). Lichtenstein’s art expresses and relieves the double bind of fated wandering by deconstructing and reconstructing it, as she describes her sculpture Velvet Books: (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Velvet Books.

Velvet Books is a sculptured amalgam representing memories that shape Lichtenstein’s British Jewish identity and art: synagogues and her grandfather’s workshop where the same royal blue fabric lined the boxes displaying diamonds. Envisioning “stacks of such cases” as “books on a shelf” links her memories to another “treasure”, that of “the word and language” (email 21-7-20).Velvet Books are certainly a multilayered piece, with that particular royal blue velvet being a material I have returned to many times in my sculptural work. The colour and fabric is often used for parochets (curtains covering the Torah ark), which are the focal point of the synagogue as well as being the protective fabric covering that conceals the ark. This same fabric is also often used for the Torah scroll mantles themselves […]”.(email 21-7-20)

Lichtenstein’s reflection suggests that like their diasporic languages and wanderings, the Jews experience their continuity as a people through the books that constitute their culture and history. The inaccessibility of Jewish religious learning also evokes memories of its precarity and the ongoing need to protect it. As Alon Confino has researched, Jewish books, especially the Hebrew Bible, were the primary objects of Nazi book burning to ensure the erasure of Jewish culture and primacy of Nazism as the true religion (Confino 2014).The original idea was conceived […] after going into my grandfather’s study after he died and realising there were books written in: Russian, Polish, Yiddish, Hebrew, German and Aramaic, none of which I could read. A wealth of language and knowledge that I could not access. So there is something again about recognising the preciousness of this whilst being unable to unlock the stories/text within. I think more than any other artwork this piece also relates directly to the lack of full access/understanding I had to my Jewish heritage for multiple reasons.(email 21-7-20)

Although London’s Jewish culture thrives in its migrations from the East End, in the 1990s, when Lichtenstein traverses the streets of Whitechapel, Spitalfields, and Hatton Garden, only faded outlines remain. As artist-in-residence at the Princelet Street Synagogue, she discovers a disintegrated past. Yet the building is also redolent with the past and identity she seeks, as though it “had been transported direct from Eastern Europe” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 22). In all its neglect and decay, the synagogue becomes the epistemic foundation which supports her explorations and interviews with former Jewish residents of the places where her grandparents lived and worked.

That the past is never frozen in its own time but intervenes in interpretations of the present is evident in Diamond Street, her study of Hatton Garden, where antiquity and the present intersect. Learning about the ancient, now subterranean Fleet River, Lichtenstein relishes “the idea that the site now being developed as one of the most advanced new railway terminuses in the world had once been a wharf where warrior monks and other passengers alighted […] hundreds of years ago, from all over the world” (Lichtenstein 2012a, p. 265). In a similar juxtaposition of past and present, generations of Jewish diamond merchants trading their treasures “on the pavement”, in kosher restaurants, and in convoluted, “Dickensian” spaces are still present in the skills practiced in sleek, security bound workshops (Lichtenstein 2012a, pp. 11, xvi). Detailed accounts of transforming gold dust into jewelry narrated alongside “quintessentially British—sausage and mash, roast dinners with over-boiled cabbage, crumble and custard”, metaphorically alloy coexisting cultural histories (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 136). In a critical turn, her narrative mosaic performs an intergenerational continuity composed of fragmented and discontinuous stories (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 136).

Although Lichtenstein parses the remnants of the past for visual information and narrative possibilities, any forensic value can only be suggestive. Incomplete and therefore inconclusive, dismantled, and indecipherable scraps do not transmute into biographical or historical evidence. Instead, Lichtenstein’s narrative mosaics develop from reading objects such as a jeweler’s thermometer, faded photographs, and even a “‘buncha bananas’” as interlocutors that mirror the partial memories recounted by her interview subjects (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 138). This epistemic relationship does not mean that objects merely illustrate the stories Lichtenstein constructs from them or hears from others. Instead, her fragments and testimonies are set into critical relationships. The significance of this reading is that Lichtenstein’s art and writing represent multiple layers and interactions between contemporary and historical interpretations of the places she seeks. In so doing, she creates a hybrid narrative aesthetic that is committed to history as a process that will be reinterpreted and even revised over time and that invigorates and enhances the historical imagination7.

4. Whispered Memory Maps

Objective analysis is not Lichtenstein’s remit. Her writing is infused with “the authorial I”, identifying her own narrative constructions and those of her subjects as partial, that is both fractional and subjective as they interpret the past through the lens of their present lives (Lichtenstein 2019, p. 10). As Ruth Gilbert maintains, Lichtenstein “acknowledges her own compromised position within [the East End’s] shifting imaginary” (Gilbert 2015, p. 214). Even Lichtenstein’s studies of maps, from medieval through contemporary periods, interlace a site’s “natural topography” with her theme of “whispered memories” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 224). In Krakow, exploring her grandparents’ history, she builds “up a mental map of the old Jewish quarter” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 224). Her hand drawn sketch of Brick Lane superimposes the street as she walked it onto an impressionistic, imaginative rendering, suggesting the challenges of representing that which is already faded in time and subject to her own mission. That mapping for Lichtenstein is a work of imaginative reconstruction is apparent in her description of Brick Lane:

Beginning with Rodinsky’s Room, Lichtenstein’s writing anatomizes place as a subjective mystery story that resists resolution. In Diamond Street, Iain Sinclair recalls the area of Holborn as enigmatic, as an imaginative construct, with its ancient hospitals, “prisons and other enclosures where you get burned, and the mysteries of Hatton Garden, which is a place I never had access to, and remains strange and intriguing” (Lichtenstein 2012a, p. 145). Walking with cultural critic Sukhdev Sandhu (Sandhu 2012) on Brick Lane, Lichtenstein notes that he “seems to be tuned into the weird reverberations of these sites and the residues and resonances of past lives in old buildings [...] a romantic place of literature, poetry and successive layers of history […]” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 250).So many memories of this street have already been erased or forgotten: hidden behind newly erected buildings, buried under recently paved streets like unexcavated archaeological treasures. I have tried to extract them through a series of walks, conversations, archival research, sound recordings and photographic outings.(Lichtenstein 2007, pp. 14–15)

Lichtenstein’s art and writing are not interested in resolving the mysteries or contested histories of the East End’s social geography. Instead, she represents missing pieces of the area’s Jewish memory as expressionist invitations to interpretive possibilities: “Brick Lane was the perfect hunting ground for me as a sculptor. I’d spend my time searching through the lost biographies of thousands, seeking objects loaded with personal memory” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 313). Every step forward, backward, and sideways, through side streets, alleyways, and abandoned or reclaimed buildings produces the shards to form a narrative mosaic of Jewish memory that commingles with memories of the lives and work of other residents who identify differently. To make this point, Lichtenstein quotes Philip Sheldrake:

Neither mythical nor mystical, the many personal stories and clues Lichtenstein gathers are transformed by her creative imagination into an expressionist forensic art. Her trips to Poland, recounted in Rodinsky’s Room, “had been intensely personal, and the images and scraps of abstract information gathered were translated into art work on my return” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 205). With their partial recall and multitudinous references, Lichtenstein’s witnesses become her collaborators. Together, however, they defy the sense that past and present could be interwoven to create a unified expression of cultural nostalgia.Memory embedded in place involves more than simply any one personal story. There are the wider and deeper narrative currents that gather together all those who have ever lived there. Each person effectively reshapes the place by making his or her story a threat in the meaning of the place and also has to come to terms with the many layers of the story that already exist in a given location.(Lichtenstein 2007, p. 189)

Historically, the lack of cohesion and linearity between past and present is explained by the Jewish East End having almost completely faded away by the time of Lichtenstein’s explorations. The first generation of immigrants and their children had moved on to prosper in middle class climes, escaping the poverty that dominated so many experiences and memories of Spitalfield’s and Whitechapel’s crowded streets and tenements. Current East Enders testify that they remain tied to its neighborhoods through ethnic bonds, economic necessity, the desire to help others, or for their attraction to its atmosphere of edgy otherness8. Life on Brick Lane in the 1990s bears no resemblance and offers few clues to that of Jewish immigrants from 1880 through various periods of their moving on. To chart this faded history and the area’s cultural and economic discontinuities, Lichtenstein superimposes faint whispers from the past onto the cultural cacophony of the present. In these terms, when Lichtenstein visits the crypt of the restored Christ Church in Spitalfields, she envisions its “long history” as “different stories echoing around the vaults, becoming a part of the fabric of that place” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 266). The evocation of spectral images and resonances does not, however, signal nostalgic longing for a mythic golden age. Referring to Brick Lane, Lichtenstein and Sandhu concur: “it’s a place of echoes of the past but not in a sentimental way […]” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 255). Instead, Lichtenstein’s expressionist representations can be viewed as her itinerary for traveling through the remembered and imagined past of the East End and Hatton Garden in order to interpret the present.

Ner Htamid

Lichtenstein’s forensic expressionism is evident in her sculpture, Ner Htamid [Eternal Light, 1994], which is composed of twelve small objects gleaned from her grandfather’s watchmaking tools and family tokens. Welded steel frames filled, like ancient amber, with objects sealed in resin, both invite and preclude investigation and interpretation. Recalling her fascination with Rodinsky’s unreadable items, Lichtenstein’s collection consists of apparently unrelated and uninterpretable remnants, including a watch face, a pickle fork on a bed of lace, and an unnamed portrait of a mother with two infants taken outside a wooden home somewhere in the Polish countryside. The position of each object in its own frame preserves its integrity while the lack of identifying labels or guiding narrative represents the challenges of constructing an interpretive approach. Like her writing about Rodinsky’s room, Lichtenstein’s sculpture rejects the imposition of a preconceived or completed narrative in favor of “a work whose essence” according to Iain Sinclair’s’ assessment, “is to remain unfinished, incomplete, abandoned”, and I would add, rescued with self-questioning meaning (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 72) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ner Htamid.

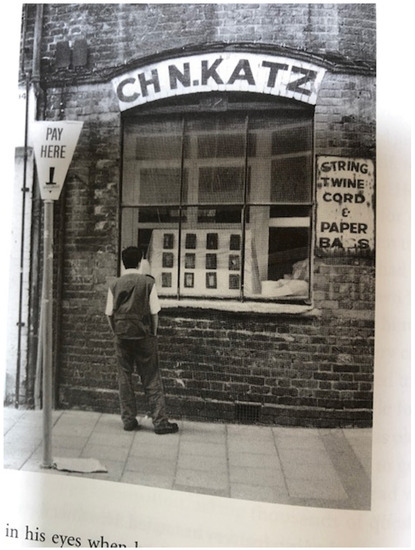

As Ner Htamid demonstrates, Lichtenstein’s imaginative reconfigurations are composed of materials that do not quite fit together. Viewed as a visual metaphor, the assemblage suggests issues about British Jewish belonging that accord with Ruth Gilbert’s position that “there is a kind of pleasure to be found in the friction that is generated by not quite fitting in” (Gilbert 2012, p. 283). The display of Lichtenstein’s sculpture in the window of Mr. C.H.N. Katz’s ancient shop in Brick Lane illustrates this “friction” by confirming the irretrievably receding presence of London’s Jewish past as well as the social and cultural migrations of British Jews, and Lichtenstein’s not quite cohesive memorialization. Instead of a sentimental or elegiac rendering of loss, Lichtenstein’s installation suggests an exegetical bridge between Jewish tradition and the contingent possibilities for its continuity. Referring to the permanently lighted Torah Ark, the Hebrew title Ner Htamid, implies that regardless of historical trauma and the discontinuities of Jewish identities, the transmission of Jewish culture from generation to generation, from place to place, will prevail. In its multivalent forms, Jewish culture encapsulates the history of its displacement and migration as critical to the construction of an ongoing present.

The historical provenance of Ner Htamid reaches back to the Princelet Street workshop of her grandfather Gedaliah Lichtenstein, whose death when Lichtenstein was seventeen prompted her feeling that “with him was buried the key to my heritage. I became determined not to let it die with him” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 19). The urge to commemorate her heritage in artistic form and to claim her Jewish birthright instigated Lichtenstein’s investigations of Jewish life and persecution in Poland and her grandparents’ “process of assimilation and integration in the new country” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 20). A defining result of this investigation was her decision to assimilate, but to Jewish culture as she adapted it on her winding journey from her grandparents’ European history to Orthodox and mystical Judaism in Israel, and then to its remapping in London. In a mutable definition, she fashions her British Jewish identity by reconfiguring assimilation as a revisionary journey of self-discovery. Instead of identifying with her non-Jewish mother’s lineage or viewing it, according to Jewish law, as an obstacle to embracing a Jewish identity, she reclaims Lichtenstein, the Jewish family’s European name and forsakes Laurence, her assimilated paternal surname9. She then embarks on her expansive yet circular journey that begins and culminates in the same Princelet Street Synagogue where David Rodinsky lived. Like her conjuring of his spectral character, the destination feels fated, as though she “was meant to be there”, especially when she discovers that her grandparents were married at this synagogue and that their first home and shop were located on Princelet Street (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 22). Instead, however, of supporting her initial “romantic” vision of the Jewish East End, Lichtenstein’s art and writing express her persistent re-visioning, impelled by “the residues of past lives still present” as recounted by resident historians of Brick Lane like the poet Stephen Watt (Lichtenstein 2007, pp. 12, 123, 2012b, p. 98).

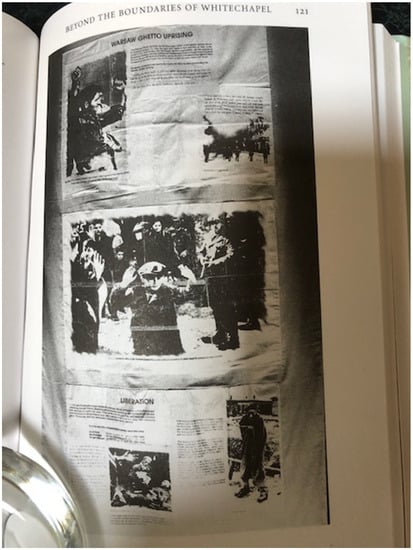

5. Memorializing a Fragmented Jewish History

The European and East End Jewish past of her grandparents is evident in Lichtenstein’s intergenerational work. Upon her return from Poland, Lichtenstein memorializes her family’s fragmented history by incorporating the Holocaust into her art (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 205). Shoah, an installation she constructed in 1993 for display at a London synagogue, consists of written fragments and children’s faded photo images from various Holocaust sites that are reproduced on torn strips of linen (Figure 3). Its unsentimental, disparate perspectives imprint the impossibility of retrieving or narrating the horrific past as a comprehensive history while commemorating the victims’ silenced voices and fragmented lives. As Lichtenstein attests, the exhibition was both inspired and haunted by the “hushed whisperings of my ancestors” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 120).

Figure 3.

Shoah.

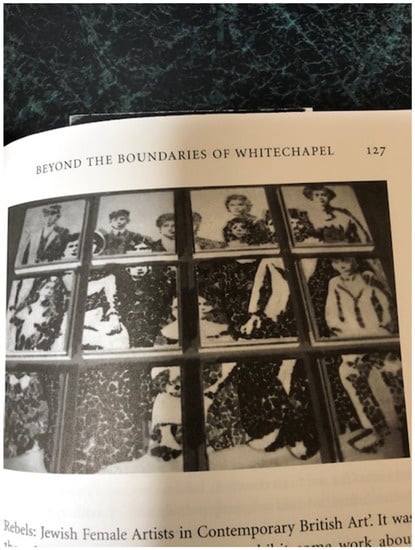

Memorializing her Jewish family a moment before their decimation, Lichtenstein created a large-scale three-dimensional mosaic, Kirsch Family, while she was an artist in residence in Arad, Israel, in 1995 (Figure 4). The mosaic is reconfigured from the only remaining photograph of her paternal grandmother’s family, taken in Poland around 1915. Like the images in Shoah, this one “haunted [her] day and night […] Of the twelve family members […] there were only four survivors. One of them was my grandmother” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 123). Copies of the original photograph had been taken by surviving family members when they emigrated to Argentina, New York, or remained in Poland. The fate of these copies and the fragments comprising Kirsch Family metonymically suggest an itinerary of Jewish loss and the search for renewal. Composed of Byzantine and Roman pottery shards found in Israel, the fragmented construction draws attention to the historical precarity of Jewish settlement as well as to restored Jewish life and culture in Israel and elsewhere. A critically reflexive work, Kirsch Family evokes Lichtenstein’s family’s history through its “complex layering of historical experience and memory” while reminding viewers of “the impossible task of presenting a complete picture of the past” and its losses (Bohm-Duchen and Godzinski 199 (Bohm-Duchen and Godzinski 1996, p. 48; Lichtenstein 1996, p. 91). The mosaic blends Lichtenstein’s search for her Polish Jewish family and heritage while verifying its untraversable autobiogeographical distance as an opportunity for creative self-examination.

Figure 4.

Kirsch Family Mosaic.

Lichtenstein’s artistic practice is shaped by a sense of urgency to examine her own role in commemorating what is lost as its memory is transformed over time and in relation to place. Objects like those composing Ner Htamid lead her to East End streets and buildings and to witnesses to London’s changing faces, such as historian and guide Bill Fishman; Reverend Kenneth Leech, a socialist Anglican priest “who fought the fascists in Brick Lane in the 1970s”; and Bengali artist Sanchita Islam, who explored her own identity journey in Brick Lane (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 41). Hatton Garden diamond merchant Harold Karton attests to the “very international but still predominantly Jewish” diamond community (Lichtenstein 2012a, p. 220). Lichtenstein finds her subjects as each one leads to another, and the missing pieces of one story are sought but not always found in another’s account. Like her sculptures, individual narratives become interlaced with others, forming a chain of cultural signification by piecing them together with her own emerging Jewish story. In constructing her personal quest as interwoven with complex interplays of interviews, Lichtenstein re-visions the city’s British Jewish immigrant past by configuring it in relation to the struggles of contemporary immigrant groups. The result is a multivocal narrative performance that serves as a proxy for readers by inviting a variety of cultural responses as we roam the East End and Hatton Garden with her.

As with all her work, these stories retain a sense of barely discernable reality. Yet like the streets and buildings Lichtenstein explores and Sandhu reflects on, “It is suggestive and haunting in terms of what you can learn from a place” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 255). Lichtenstein translates these shadows into tactile writing that uses textured and sensual detail to represent the merging of past and present, “stuff” she “picked up off the street: fabric remnants, wicker baskets covered in pink Arabic text, scraps of leather” and the smell of “a salt-beef sandwich with mustard on rye” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 8). Lichtenstein then edits these narrative materials as she “walks around to see the other side”, creating a “sculptural perspective and understanding” (27/5/20 conversation). Along with the memory fragments of her interlocutors, her constructions represent the historical and aesthetic challenges of coaxing them into a Jewish chronicle composed of cultural differences that frustrate efforts to find unidimensional answers or linear historical progression. As Iain Sinclair avers, “Like the best detective stories, her narrative is broken into not-quite-resolved episodes” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 4). Lichtenstein’s narratives remain in flux, to be interrogated but resolved only as continuing investigations.

6. Intersecting Narratives

When she is not deciphering and transfiguring echoes and the realia of everyday life, Lichtenstein is in motion, walking and talking with the few remaining Jews in London’s East End and with those who make its neighborhoods their habitat today. The “physical act of walking” is her entryway to Jewish stories, places, and identities, but not as though they are already established, clearly marked, and waiting to be discovered (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 17). Instead, her pattern of walking is circuitous but indeterminate, a physical analogue to the shape of her artistic chronicle. This autobiogeographical pattern is evident in the structure of her books, as evinced in Diamond Street, which begins with recounting a childhood memory of accompanying her father on buying trips in Hatton Garden. From her “sculptural perspective”, she constructs a narrative in which her father’s carefully orchestrated movements find their meaning in his meticulous work as a social and economic “ritual” that has signified the history of Hatton Garden “for over a century” (Lichtenstein 2012a, pp. xv, xvi). Lichtenstein identifies with her father and grandfather by embracing yet reconfiguring this defining ritual in her book’s intense attention to the objects of their trade. Although this attention recalls her captivation with Rodinsky’s room and the objects she collects and assembles into sculptures, she also acknowledges that her art can only represent ruptures between knowledge that she seeks, that which remains elusive, and “knowledge [that] will be lost” (Lichtenstein 2012a, p. xvii).

Like her art, Lichtenstein’s Jewish identity is tethered to her family’s migratory history but contingently, encouraging critical reflections that integrate the history of more recent immigrant groups into her family’s story. For example, in On Brick Lane, conversations with Bengalis Raju and Nur provide both a corrective and transcultural continuity to the story of her grandfather’s shop on Brick Lane. Raju reveals that the current curry restaurant is not the original building but that Gedaliah’s “small and modest” shop was torn down and rebuilt in 1934. Nur outlines his family’s history as participating in Brick Lane’s cultural and economic chronicle, beginning with his father’s arrival in 1962 and the subsequent development of various businesses that employed Bengali immigrants (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 257). Lichtenstein’s inclusion of these stories suggests that the British Bengali experience as well as stories recounted by “born-and-bred East Ender” Alan Gilbey are crucial to understanding the trajectory of British Jewish history and culture (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 136). Like the shards in Israel that evoke the discontinuities of Jewish history, “a piece of my own family history fell into place”, becoming an integral part of her narrative mosaic (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 257). John Kirk’s concept of “time-space compression” provides a useful heuristic to Lichtenstein’s constructed relationship between Jewish history, her family’s stories, and those of more recent London immigrants as marking “the shrinkage of space through time: the confluence of diverse yet separated communities, more often than not in some form of competition with each other, thus suggesting a condition of both fragmentation and homogenization” (Kirk 2001, p. 354).

Lichtenstein also views Jewish history and experience through the prism of contemporary upheavals in other communities. A story of National Front neo-fascists attacking the East End Bengali community in 1978 recalls Kristallnacht (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 44). Visiting a mosque conjures the historical memory of “Jewish anarchists clashing with Orthodox leaders” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 83). She creates fragmented Jewish stories by using “abandoned things” now sold by Bangladeshis (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 8). As a result of learning from her Muslim husband about his religion and culture, she reads Brick Lane “in a different way” (Lichtenstein 2007, p. 6). Her voyage of discovery proceeds as both coterminous and discontinuous with those of her subjects.

7. Salvaged and Uncharted Stories

Lichtenstein’s narrative mosaic begins with a violent end10. Early in the first chapter of Rodinsky’s Room, Lichtenstein’s journey of discovery appears stalled when she witnesses artefacts from London’s Jewish past being destroyed. The “story of the disappearing Jewish East End” explodes in neo-Nazi vandalism at the Kosher Luncheon Club and “a racist arson attack” on the holiday of Shavuot, when prayer books from the adjacent Great Garden Street synagogue are used as an accelerant (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 37). The mimetic detail with which the final cataclysm is narrated creates an expressionist “image of hell” as it might have been painted by Hieronymus Bosch, a bad “acid” trip that transfigures the postmodern violence into a hallucinatory medieval morality tale (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 38). Lichtenstein understands that synagogues are deconsecrated as congregations move on, but the sight of “Black-clad artists”, a “zombified crowd” of “Spaced-out ravers”, desecrating the bimah and “a smoke machine” blowing “obnoxious air to the revelers below” reminds her of scenes from “Nazi Germany” (Lichtenstein and Sinclair 1999, p. 40). In contrast with the veneration of Jewish culture depicted in Velvet Books, the desecration of ancient prayer books spells disaster.

This portentous scene does not, however, lead inexorably to tragedy, like an ancient myth. Instead, Lichtenstein positions British Jewish culture in relation to the Jewish historical memory that is a defining metaphor of her art and writing. Wandering, in terms of her sojourns through London’s streets and undergrounds, through transcultural journeys, and inclusive of multivocal oral histories, intersect with wandering in a metonymical sense.

Her work conjoins objects and images that represent fragmented memories reflecting the disorientations of Jewish persecution, loss, and the challenges of recreating Jewish culture in unfamiliar languages. In Lichtenstein’s art and writing, wandering suggests a multidirectional diaspora in which British Jewish culture, its identities, beliefs, and practices, are open to exploration, myriad forms of expression, and interrogation. In contrast to the cataclysmic ending with which her chronicle begins, Lichtenstein’s conclusion to Diamond Street is characterized as an open ticket to undeterred explorations:

Standing at the bottom of the River Fleet, liquid history, I thought back up, above ground, to Hatton Garden and the stories I had uncovered. After years of researching, crossing the same territory repeatedly, listening and gathering memories, whispers, shards, weaving together fragmentary histories, trying to understand the multiple transitions of the area, I felt that with Hatton Garden, a place so rich in memory-traces, lost landscapes and sacred architecture, I had only just begun to scratch the surface.(Lichtenstein 2012a, p. 331)

Instead of arriving at a conclusive portrait of British Jewish culture and identity or of London’s migrant past and present, Lichtenstein’s artistry envisions an unfolding chronicle in which the transmission of intergenerational and transcultural memory coalesces in an unstoppable stream of interactive stories. The only fixed and determined phenomenon will be the ongoing work to intertwine stories that enfold London’s British Jewish culture and the British Jewish identity Rachel Lichtenstein will continue to create, question, and reconfigure as artistic expression.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrams, Nathan. 2016. Hidden in Plain Sight: Jews and Jewishness in British Film, Television, and Popular Culture. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Neal. 2010. Imaginative Geographies: The Politics and Poetics of Space. In Ciaran Carson: Space, Place, Writing. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vjcgf.6 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Baker, Brian. 2007. Iain Sinclair. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Devorah. 2015. Life Writing and the East End. Edited by David Brauner and Axel Stahler. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 221–36. [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher, Hannah. 2013. London’s (Migrant) Villages Within the Metropolis. Limina 19: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm-Duchen, Monica, and Vera Godzinski. 1996. Rubies and Rebels: Jewish Female Identity in Contemporary British Art. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Brauner, David, and Axel Stähler, eds. 2015. The Edinburgh Companion to Modern Jewish Fiction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette, Sarah. 2009. Literature and Gentrification on Brick Lane. Criticism 51: 425–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confino, Alon. 2014. A World Without Jews: The Nazi Imagination from Persecution to Genocide. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Susan Alice. 2001. A Room of Our Own: Rodinsky, Street Haunting and the Creative Mind. Changing English. 8: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, Rachel. 2006. Towards a Re-articulation of Cultural Identity. Third Text 20: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Ruth. 2007. The Golem in the Attic: Rodinsky’s Room and Jewish Memory. Jewish Culture and History 9: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Ruth. 2012. Displaced, Dysfunctional and Divided: British-Jewish Writing Today. Whatever Happened to British Jewish Studies 12: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Ruth. 2015. Jewish: Negotiating Identities in Contemporary British Jewish Literature. Edited by David Brauner and Axel Stahler. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 210–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Ruth. 2019. Metaphors of Migration in the East End Imaginary. Jewish Culture and History 20: 204–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory-Guider, Christopher C. 2005. Sinclair’s Rodinsky’s Room and the Art of Autobiogeography. Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London, 3.2. Available online: http://www.literarylondon.org/londonjournal/september2005/guider.html (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Kirk, John. 2001. Urban Narratives: Contesting Place and Space in Some British Cinema from the 1980s. Journal of Narrative Theory 31: 353–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, Tony. 2018. Doing the Lambeth walk, Oi! Heritage, Ownership and Belonging. In An East End Legacy: Essays in Memory of William J. Fishman. Edited by Colin Holmes and Anne J. Kershen. London: Routledge, pp. 211–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kushner, Tony, and Hannah Ewence, eds. 2012. Introduction. In Whatever Happened to British Jewish Studies? London: Valentine Mitchell, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 1996. Artist Biography and Statement. Edited by Bohm-Duchen and Vera Grodzinski. London: Lund Humphries, pp. 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2007. On Brick Lane. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2012a. Diamond Street: The Hidden World of Hatton Garden. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2012b. Simon Blumenfield, ‘Jew Boy’. London Fictions. Edited by Andrew Whitehead and Jerry White. Nottingham: Five Leaves Press, pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2016. Estuary: Out from London to the Sea. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2019. Contemporary British Place Writing: Origins, Definitions, New Directions. Ph.D. dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, Rachel. 2020. The Stories We Tell. Available online: https://www.arvon.org/rachel-lichtenstein-the-stories-we-tell/__;!!Dq0X2DkFhyF93HkjWTBQKhk!D7AFdNvMJBQq0iJNc5FElnQxZqxo9pfGzwfVt8WKM83z9bxxdf_YQS50MHn5GR11Y5pJc2I$ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Lichtenstein, Rachel, and Iain Sinclair. 1999. Rodinsky’s Room. London: Granta. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlstein, Lea. 2020. Migration—A New Normal. European Judaism 53: 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, Sukhdev. 2012. Review Diamond Street. The Guardian, June 15. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Susan E. 1994. Ecriture judaique: Where Are the Jews in Western Discourse? In Displacements: Cultural Identities in Question. Edited by Angelika Bammer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 182–203. [Google Scholar]

- Sicher, Efraim, and Linda Weinhouse. 2012. Under Postcolonial Eyes: Figuring the "Jew" in Contemporary British Writing. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See (Brauner and Stähler 2015) and (Abrams 2016). |

| 2 | Full discussion of Lichtenstein’s most recent book, Estuary, her autobiogeograhical exploration of the working cultures of the Thames River’s outlets to the North Sea, is beyond the scope of this essay. |

| 3 | Kushner examines the “flux, conflict, solidarity, ethnic succession and persistence” of the East End’s history, “a complex mix of roots and routes” (Kushner 2018, p. 224). |

| 4 | The Dybbuk was created by the Russian Jewish folklorist S-Ansky and concerns the deadly possession of a woman by the spirit of the man who expected to marry her. Devorah Baum offers a dual perspective: “Lichtenstein, notwithstanding her occasional concession to the ‘grim and lonely’ fact, prefers to trust in the fantasy life of her imagination when pursuing her subject,” (Baum 2015, p. 233). As I argue, Lichtenstein’s art and writing interrogate this “trust” critically. |

| 5 | Ruth Garfield criticizes Lichtenstein’s search for the past as “conservative, an anchor for one’s identity” and a “romance with a world that no longer exists” rather than an open-ended journey (Garfield 2006, pp. 99, 100). |

| 6 | Gilbert’s close reading of Rodinsky’s Room concludes that “the text acknowledges the perils of dwelling in dusty attics in order to construct a coherent and grounded identity as a postmodern Jew” (Gilbert 2007, p. 68). |

| 7 | Sicher and Weinhouse claim that Lichtenstein’s East End is “a simulacrum”, a “virtual Jewish space of invented memory”, without considering her self-questioning methods (Sicher and Weinhouse 2012, p. 163). Boettcher affirms Lichtenstein’s “literary rendering of what people remember and what they are willing to reveal” (Boettcher 2013, p. 5). |

| 8 | Brouillette argues that On Brick Lane and other recent novels featuring the street “avoid [how] they participate in its remaking, at once overseeing and servicing the culturalization of gentrification” (Brouillette 2009, p. 436). |

| 9 | Baum notes that “Jews are partly at risk of disappearing from public records because they are constantly changing their names” (Baum 2015, p. 223). |

| 10 | Estuary also begins with a British Jewish tragedy, a legend about Jews escaping the Plague who were abandoned on a Thames sandbank by a boatman who demanded more money than they had: “The white water that swirls around this sandbank is said to be caused by those lost Jewish souls kicking up in torment”. (Lichtenstein 2016, p. 5) |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).