2.1. Hungry Eyes: Gaiman’s Corinthian, Queer Fear, and the History of Horror Comics

Appreciating Kiernan’s sadomodernist achievement with The Dreaming requires first understanding The Corinthian as a character, and as the occasion for Kiernan’s involvement in the series. Among The Sandman’s most popular and frightening characters, The Corinthian is a rebellious, homicidal nightmare who has attained a cult status all his own, remaining widely recognized as among the most important late twentieth century icons of supernatural horror. The Corinthian is, in part, Gaiman’s homage to two classics of nineteenth century gothic fiction. With his ocular dentata and penchant for consuming the eyes of children, he echoes the eponymous terror of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann” (1816), the tale that inspired Freud’s theory of the uncanny, to which Kiernan’s reinvention of the character forcefully returns. In his epic rebellion against his creator, he is also an echo of Shelley’s Frankenstein. His moniker itself reflects his nineteenth century roots. In a 11 June 1996 email to Kiernan, Gaiman explained: “The Corinthian—really, its an old word for one who lives very loosely, frequents brothels, has too much nasty sex. And I found it thumbing through a book of Victorian underworld slang, and thought it was pretty, and it had all these weird connotations (Corinthian leather, the letter to the Corinthians etc.) and that was what I called him”.

However, The Corinthian also reflects the moment of his creation. His predilection for killing children, tendency to escape from dreams into the waking world, and penchant for vicious witticisms echo Freddy Krueger, from the popular 1980s horror franchise, Nightmare on Elm Street. More importantly, he is Gaiman’s fond homage to the visions of queer horror created by his friend, Clive Barker. Originally drawn by Mike Dringenberg, The Corinthian first appeared in Sandman 10 (1989) as part of “The Doll’s House” storyline, and variations of the character, canonical and otherwise, appear throughout later storylines of the series.

When readers first encounter The Corinthian, it is after he has wandered the waking world for decades, existing vampirically as an ageless, itinerant serial killer who preys particularly on young men and boys, extracting and devouring their eyes, enjoying the rush of visions and memories that flood him at this consumption. Decades ago, he absconded from The Dreaming and his duties as a nightmare during Morpheus’s captivity by the occultist Roderick Burgess. After being summoned by the Dream Vortex, Rose Walker, Morpheus confronts and uncreates this iteration of the character, later recreating a supposedly perfected version of The Corinthian during the “Kindly Ones” storyline. This Corinthian, more duty-bound than his predecessor, serves his function as a nightmare until Kiernan’s work with The Dreaming, during which he goes rogue and once again begins to kill humans.

Gaiman’s Corinthian is an original, troubling expression of queer fear, a phrase that ambiguously synthesizes anxieties about nonheteronormative sexual identities with fictions, often by queer creators, that expose such anxieties. He is close kin with Barker’s queer- and kink-inspired entities, including the Cenobites from the Hellraiser franchise. He also offers an especially precise anticipation of the radically negative queerness Lee Edelman advocated in his 1998 essay “The Future Is Kid Stuff: Queer Theory, Disidentification and the Death Drive”, which later formed the core of his withering 2004 exercise in polemical Lacanian theory, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Arguing that queerness is presented in symbolic opposition to the politics of reproductive futurism that takes as its emblem the imaginary figure of the child, Edelman argued that queer theory must embrace its association with radical transgression and the death drive.

The Corinthian encapsulates “the queer,” in Edelman’s words, coming “to figure the bar to every realization of futurity, the resistance, internal to the social, to every social structure or form” (2). A relentlessly narcissistic, antisocial, and future-negating figure who rejects his Dream-imposed function, the first Corinthian is a practical prototype for Edelman’s program. Embracing negativity, irony, and a stark refusal of “the reproduction of futurity” (

Edelman 2004, pp. 16–17), The Corinthian’s compulsive pleasure in the consumption of young men’s eyes literalizes “the violent rush of a jouissance” (153) that Edelman associated with an embrace of the death drive.

Freud’s theory of the uncanny, rooted in his tendentious reading of Hoffmann’s “The Sandman,” was grounded in the assumption that Nathaniel’s terror of the eponymous character’s consumption of eyes is a manifestation of latent castration anxiety. Gaiman reworked this conception with The Corinthian by creating a wry personification of the moral panics that plagued the reception history of horror comics through the twentieth century, which often focused on the power of comics to corrupt the morals, compromise the masculinity, and damage the eyes of a largely young male readership. The psychiatrist, social activist, policy consultant, and infamously influential crusader against the supposed social ills caused by comics, Fredric Wertham, for example, claimed not only that comics tended to deprave and corrupt the minds of young readers, but also to damage their vision by enticing them to focus excessively on pulpy, low-quality, and prurient images, a tendency he saw thematized in the frequent images of damaged eyes in horror comics (

Wertham 1955, p. 623; see also

Nyberg 1998;

Tilley 2012; and

Wertham 1967).

The Corinthian’s predatory predilections reinforce his connection with Wertham’s concerns; his preferred victims are primarily male children and adolescents, and his queerness corrupts them before he destroys their eyes. The Corinthian’s compulsive pursuit of ocular aliment is also reminiscent of what art theorist

David L. Perkins (

1994) called “the hungry eye” effect, which stems from the reader’s desire for a further image to narratively supplement the first, giving rise to the impetus to “read” more that makes the sequential structure of comic art so effective (so effective, Wertham might have added, that it drives vulnerable readers to self-abuse, and drives their eyes to devour image after image until blindness results). As much as Freddy Krueger is a particularly cinematic embodiment of gothic terror, drawing on a long reception history that interprets films as techno-visually embodied dreams, The Corinthian is a particularly comic book kind of nightmare, one who reflects the history of the medium of his creation. He exemplifies Elizabeth Freeman’s Frankenstein-focused description of monstrosity perfectly: “the monster is, in many ways, a double for both the genre he inhabits and for the disaggregated sensorium of the gothic character and reader.” (

Freeman 2010 97–98) Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s classic “Monster Culture: Seven Theses” offers a caveat against attempting to extract “a transcultural, transtemporal phenomenon” (5) from the many historically and culturally specific variations of particular monsters. This caveat is doubly applicable for Frankenstein’s creature, whose monstrous lineage itself, drawing as it does on different folkloric, mythic, and literary traditions, is an open question. Shelley’s creature, an animated assemblage of heterogeneous corpora, embodies what Cohen called the “construction and reconstitution” (

Cohen 1996, p. 5) of cultural monstrosity itself.

Gaiman’s Corinthian offers a further reconstitution that is fine-tuned to the formal characteristics and historical reception of comics themselves. He is a seminal figuration of how moral panics surrounding comics implicated not just their content, but also their form, as dangerous. In a sense, then, even before Kiernan got her hands on him, the Corinthian was comics’ sadomodernism personified; her revisions effectively amplified and deepened this aspect of the character.

A second, very different,

Sandman character crucial to Kiernan’s involvement with

The Dreaming also requires some context here: Wanda Mann, from “A Game of You.” In her introduction to

The Dreaming #22, Kiernan explained to readers that “in July 1994, I was invited to write a short story for the prose anthology, THE SANDMAN: BOOK OF DREAMS; a long-time reader of the comic, I jumped at the opportunity and wrote a piece called “Escape Artist,” a sort of prequel to “A Game of You,” about Wanda Mann’s troubled childhood in Kansas.” (

Kiernan and Artists 1998–2003, #22). As a trans woman, Kiernan found Gaiman’s development of Wanda’s character inspiring; Gaiman’s brief 17 February 1997 email to her stated, “I’m pleased that Wanda gave you a role model. I always thought she was the heroine of Game of You” (

Gaiman 1997a,

1997b).

It was chiefly due to his admiration for “Escape Artist” that Gaiman invited Kiernan to write for

The Dreaming. This invitation occurred in a 7 May 1996 email that explicitly associated Kiernan’s gothic sensibility with The Corinthian’s:

Who would one get to write a mini-series about someone who still possesses inside them the soul of a gay child-abusing serial killer who still eats eyes and has a distinct fondness for knives, and is just the coolest person in the whole world, going off and getting into and out of all sorts of trouble… and I thought maybe you. It’s probably just the knives… D’you wanna follow up on this? Or are you too busy doing sensible things?

Having just completed a draft of her first novel (initially called “Webs”, it would become

Silk and finally see publication two years into

The Dreaming’s run, around the time Kiernan took over as story runner), Kiernan set aside sensible things, including novel writing, palaeontology, and singing for the band Death’s Little Sister, and devoted herself primarily to writing comics.

2.2. “It’s Probably Just the Knives”: Kiernan and the Corinthian

Turning to Kiernan’s writing for The Dreaming, a summary of Echo and The Corinthian’s intersecting storylines is in order. Their fatal intersection is signalled from the opening of “Souvenirs” (#17–19). While Echo is described in Kiernan’s notes as “gender-fluid” at this point, she uses male pronouns for the character until after Echo is “reincarnated” in The Dreaming. While I realize it presents challenges to the reader, I have elected to echo Kiernan’s use of pronouns at different points during Echo’s storyline in order to highlight the unsettling of gender norms Kiernan performed with the character, for reasons which the discussion that follows should make apparent.

Initially, Echo is the lover and partner-in-crime of Gabriel, a now-eyeless survivor of the first Corinthian’s predations. In an echo of Freud’s Hoffmann-inspired theorization of the repetition compulsion that parallels Edelman’s Lacanian formulation of queer negativity, Gabriel plays out his own trauma by preying on other young victims, taking their eyes as temporary replacements for his own, achieving both a kind of jouissance and flashes of mystical vision in the process. Gabriel is killed by the second Corinthian, who has been sent to clean up the mess created by his predecessor, with the aid of Matthew the Raven. The Corinthian takes one of Echo’s eyes, but leaves him alive, alone, and desperate for revenge.

Echo’s storyline continues in the three-part “Unkindness of One” (#22–#24). Portrayed in an open silk robe, bra, and panties, an outfit that suggests his gender fluidity is shifting toward “female” identification, Echo attempts to avenge Gabriel by conjuring Eve, the First Woman, and her raven companion (Lucien the raven, rather than Matthew). Their conflict arguably offers an indirect commentary on the attempts of a number of feminist writers of the 1970s and 1980s, including Mary Daly and Janice Raymond, to exclude trans women from their agenda, a theme that will be built upon below. With her ancient, mythic potency, Eve easily defeats Echo, but again leaves him alive, now even more broken and lost.

Echo’s storyline reconverges with that of The Corinthian in the three-part “The Gyre” (#36–#38). During this storyline, Echo, suffering from heroin withdrawal, is badly injured by would-be drug thieves. As he dies while drifting in and out of dreams, he reawakens into The Dreaming to find that he has regained his missing eye, and that moreover, his body has manifestly developed “female” sexual characteristics (#36, 21–23). This leads Echo to realize The Dreaming is not “just a dream,” but as “real” as, and in some ways more real than, waking reality. In issue #38, Dream appoints Echo to fill the office of Nightmare formerly held by the once again rebellious and homicidal Corinthian, whom he has relegated to live as one of the mortals he is so fond of preying upon.

From her earliest involvement with the series, Kiernan returned to The Corinthian’s nineteenth century gothic literary roots in formulating his future, and two of these gothic precursors are especially important for understanding the significance of Echo’s transposition with The Corinthian. In a 19 May 1996 email to Gaiman, Kiernan noted, “I’m looking at stuff in FRANKENSTEIN and Freud, Campbell and GRENDEL, and E.T.A Hoffmann’s DER SANDMANN, for further inspiration.” Both Hoffmann’s tale and Shelley’s novel prove especially important to the trajectory Kiernan conceived for The Corinthian, which the email described as:

Largely the “new” Corinthian’s search for identity and a reconciliation with his “history,” that is to say, the original Corinthian. The “new” Corinthian functions as the nightmare that Morpheus intended him to be, as a mirror into which sleepers look and see the darkness, the blackness, within themselves. It seems to me that the first Corinthian became somehow neurotic, due to the flaw/s in his creation, more than rebellious, fixating on a symbol of his purpose, the eyes of mortals, which became, for him, a fetish. And, of course, he mistook his purpose as one of demonstration, instead of reflection: he set out to show mortals something horrific (serial murders), instead of allowing them to see something much more terrible, the greater darkness hidden in their own souls.

Kiernan’s emphasis on the “flaw/s in his creation” signals her closer alignment of The Corinthian with Frankenstein’s creature. This alignment came at a time when Frankenstein’s creature was increasingly being invoked in the context of trans identities. Trans-exclusionary feminists, including Mary Daly and Janice Raymond, had described transgender women as being abominable products of medico-surgical transformation. This trope informed trans activist and artist

Susan Stryker’s (

2013) powerful piece of defiant reclamation, “My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix” in 1994. Stryker actively reclaimed her identification with Frankenstein’s creature, using it to perform her own transgender rage, transforming the broader social perception of Shelley’s novel in the process.

In displacing The Corinthian from his office as nightmare and replacing him with Echo, Kiernan suggestively associated Echo with Frankenstein’s creature, weaving the identification at the heart of Stryker’s performance into

The Dreaming’s storyline. Echo the Nightmare’s attempt to usurp control of the Dreaming from Dream echoes Milton’s Satan’s attempt to wrest control of Heaven from its Creator. Shelley’s Creature recognizes himself in Milton’s Satan, a recognition he embraces after his creator refuses to create a companion for him. In emphasizing

Frankenstein as one of Gaiman’s source texts for the Corinthian, Kiernan also emphasized how Shelley’s novel returns to

Paradise Lost. She thus shapes the Corinthian’s future by revisiting

Frankenstein’s past. At the same time, by crafting a storyline in which a character who has transitioned from male to female attempts to seize control of The Dreaming, she also arguably presents a satirical literalization of the transphobic anxieties voiced by Raymond’s

The Transsexual Empire (1979, 1994), to which Stryker’s Frankenstein performance directly responds (

Stryker 2013;

Zigarovich 2018).

While Stryker is not explicitly mentioned in

The Dreaming’s storyline or letter columns, Kiernan did recommend readers seek out Kate Bornstein’s influential fusion of theory, cultural analysis, and autobiography

Gender Outlaws, “for a wonderful elucidation of the human need to perceive gender categorically” in the letter column for issue #23 (

Kiernan and Artists 1998–2003).

Gender Outlaws expresses the social policing of gender binaries in terms strongly suggestive of Shelley’s novel: “In living along the borders of the gender frontier, I’ve come to see the gender system created by this culture as a particularly malevolent and divisive construct, made all the more dangerous by the seeming inability of the culture to question gender, its own creation.” (

Bornstein 1994, p. 12). Bornstein’s description aligns not transsexuality but cisheteronormativity with the creation of monstrosity, inverting a rhetorical trope all-too-familiar from transphobic feminists like Daly and Raymond. These associations are a crucial subtext to Kiernan’s realignment of The Corinthian with Frankenstein, and her subsequent displacement of this association onto her own hopeful monster and sadomodern personification, Echo.

Kiernan’s invocation of Bornstein also signals her use of “transgender” as a more general means of describing certain kinds of nonbinaristic sartorial and literary style. “Transgender Style,” the first chapter of

Gender Outlaws, begins “I see fashion as a proclamation or manifestation of identity, so, as long as identities are important, fashion will continue to be important” (

Bornstein 1994, p. 3), and continues, “My identity as a transsexual lesbian whose female lover is becoming a man is manifest in my fashion statement; both my identity and fashion are based on collage. You know—a little bit from here, a little bit from there? Sort of a cut-and-paste thing. And that’s the style of this book. It’s a transgendered style, I suppose.” (3). In accordance with this usage, Kiernan’s writing for

The Dreaming has a “transgendered style” inseparable from both its sadomodernist provocations and its gothic sensibility.

2.3. “Goth Nonsenses”: Queerness and Negative Aesthetics

Kiernan emphasized the close connection between goth culture and gender fluidity in both her scripts and her letter column responses, emphasizing that “goth” itself can signal a particular sort of “transgendered style.” Kiernan’s script for issue #17 describes Echo’s appearance in detail, while highlighting this intersection: “an exquisitely beautiful boy who takes great care with his appearance. Echo almost always crossdresses, but isn’t exactly a drag queen. There’s no pretension here at actually passing for female (no fake tits, for example), but he wears the clothes well. Echo is very goth and tends to wear long, black dresses, lots of lace and velvet. Especially lace. Echo looks a lot like a much paler Jaye Davidson” (

Kiernan 1999).

However, despite this detailing of Echo’s appearance, and description of his difference from forms of gender nonconformity likely to be more familiar to readers in the late 90s, his gender fluidity clearly puzzled both many of the series’ artists (as will be discussed below) and many of its readers. In response to a reader’s question about whether Echo is a “drag-queen” or “transsexual” in issue #23, Kiernan explained, “When I created Echo, I wanted to touch on the fluidity of gender that is so much a part of goth culture. But I think I originally conceived of Echo more the way he (and that’s the pronoun I feel most comfortable using with the character right now) appears in “Unkindness of One,” but he changed as I wrote the first draft of “Souvenirs” (as characters are wont to do), becoming more overtly feminine.” (

Kiernan and Artists 1998–2003, #23 26). Kiernan affirmed that Echo’s gender identity was at this stage very much an open question, even to her. Echo’s later transition arose organically, giving it a sense of both strangeness and integrity, marking Kiernan’s staunch refusal to treat identity or orientation as a plot device at a time when most LGBTQ+ representation in major studio comics (and there was little of it to begin with) tended to do just that. It also reflects Kiernan’s Lynchian (or Burroughsian) embrace of the aleatory. From her allowance of the series’ characters to develop along their own lines, to her creative responses to issues emerging from her interactions with editors, artists, and readers, Kiernan’s approach to the series incorporated contingency to powerful effect.

Kiernan’s letter column response continued,

I don’t think that I’d want to class Echo, as we’ve seen him so far, as either a drag queen or a transsexual, but as more generally transgendered (and it is his gender, not his sex, that we’re talking about.) Echo falls into a grayer area, somewhere less definite, where gender roles (choice of clothing and the sex of his lover, for example) are less rigidly delineated than we might be used to thinking of them. How he dresses, or the fact that his lover was male, does not necessarily mean that he sees himself as female. In the future, we might see Echo polarize a bit more, perhaps choosing a side, so to speak. Or we might not. (26)

An astute discussion of the complex, multiple, difficult-to-label, and historically and culturally contingent nature of gender identity and expression was not something many readers expected to find in a DC comic in 1998, clearly, and it caused a flurry of disgruntled letters. For example, a letter included in #27 sputters, “Gabriel and Echo! What in God’s green earth is this! I even just finished reading a response to a reader who sent a question about Echo asking what gender he/she is! And you respond with, and I quote, ‘I wanted to touch on the fluidity of gender that is so much a part of goth culture’ and went on to ramble about other goth nonsenses.’”

These “other goth nonsenses” include the harrowing films of David Lynch, Lars von Trier, Michael Haneke, and other filmmakers associated by Weigel with sadomodernism. The Dreaming was Kiernan’s first experience scripting comics, and she drew on her knowledge of film, rather than her more limited knowledge of comics, in developing the series. This led her to mirror the techniques of such “self-consciously sadistic films” as Lynch’s Lost Highway and Haneke’s Funny Games (both 1997) in creating a series subversive of both gender-representational and genre-imposed conventions of comics storytelling. Predictably, Kiernan’s provocative writing for the series proved as divisive amongst readers as the films she admired proved for mainstream audiences, as such disgruntled letters amply attest.

A letter printed in the column for issue #30 similarly complains about the series’ gothic sensibility, concluding, “I imagine you’re probably a big fan of dismal creations such as David Lynch’s recent pictures.” Kiernan replied:

Dreams, as this place where our deepest fears and desires are played out free from the waking inhibitions of sanity and social taboo, seem to me to be anything but reassuring. For me, the very act of dreaming is an unsettling one, calling our most basic assumptions about ourselves and our perceptions of the world into doubt on a nightly basis. And that’s how I’ve chosen to approach THE DREAMING. As for David Lynch, I’m afraid you’ve got me there.

Kiernan’s adoption of sadomodernist strategies inspired by Lynch, Haneke, and others was a natural formalist extension of her gothic sensibility, one meant to call into question the expectations and assumptions of the series’ readers, not all of whom were grateful for such provocations.

By Kiernan’s “gothic sensibility” I mean two intrinsically linked things. First, Fred Botting’s characterization of gothic texts as informed by a “negative aesthetics” (

Botting 2014 1) that operates “ambivalently: the dynamic inter-relation of limit and transgression, prohibition and desire suggests that norms, limits, boundaries and foundations are neither natural nor absolutely fixed or stable despite the fears they engender.” (9) Such “negative aesthetics” align closely with Weigel’s conception of sadomodernism, perfectly describing Kiernan’s approach to the series, marking out its difference from aspects of Gaiman’s more varied, and more often comedic, tone with

Sandman. Kathryn Hume persuasively characterized

Sandman’s overarching genre as mythic romance, and while the Miltonic conclusion of

The Dreaming marked a decisive return to this genre, Kiernan otherwise moved the series more consistently into gothic terrain than

Sandman had gone (

Hume 2013).

Second, “gothic” carries a musical and subcultural meaning that Kiernan frequently signaled both in the storyline itself and in her letter column responses. Kiernan’s run on the series, like her first novel

Silk, drew extensively on her own experience as part of the 1990s goth scene in the southern U.S., including as vocalist for the band Death’s Little Sister, the name itself a reference to the character Delirium from

Sandman. In

Goth Music: From Sound to Subculture, Isabella van Elferen and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock theorised goth music and style as “a socio-musical reality: a constantly moving set of convergences and divergences between human and non-human, musical and non-musical actors,” one involving “subcultural rituals such as dance and music exchange” (

Elferen and Weinstock 2016, p. 6). Kiernan’s fictions from this period regularly referenced their participation in this “socio-musical reality.” Both

Silk and

The Dreaming wear their cinematic and musical influences proudly, rife with Lynchian tension and ambiguity, gleaming darkly like David Bowie’s concept album

Outside (1995), and both are recognizably wound with rhythmic echoes and verbal allusions to goth rock and darkwave tracks. The letter columns for

The Dreaming even make periodic reference to Kiernan exchanging mixed tapes with readers, reinforcing the importance of such “subcultural rituals.”

While this explicitly gothic orientation delighted some of The Dreaming’s readers, it alienated others, as the letter columns attest. For example, the letter in #27 that condemns the series’ “goth nonsenses” also gripes, “I hate goths. I am so goddamn tired of reading about them seeing them and hearing about them. I have this one big problem, one of my favorite comics seems to be pro-goth.” Kiernan’s intensification of the already gothic aesthetics of Sandman with The Dreaming, her public self-identification with goth subculture, and her emphasis on Echo’s involvement in this subculture led many readers to identify her with Echo’s character, particularly since most readers of Sandman were aware that Dream (or at least, his earlier incarnation, Morpheus) was in certain respects modelled on Gaiman himself.

It should be noted that Kiernan never announced herself as a trans woman in the pages of The Dreaming, so most of the series’ readers were presumably unaware of this, meaning their association of her with Echo’s character did not stem primarily from Echo’s “gender transition,” but from their shared association with goth subculture. With its portrayal of Kiernan’s sadomodern personification, Echo, as a Satanic aspirant to Dream’s throne, the series fictionalizes the complaints of anxious readers, who were convinced she was usurping Gaiman’s auctoritas and perverting his creation. Such complaints led Gaiman to include a brilliantly tongue-in-cheek apologia as an introduction to issue #39, one that reinforces the connection between Kiernan’s authorship, The Corinthian, and the moral panics around comics’ perceived tendency to “deprave and corrupt” young minds.

“In the late 1950s and early 1960s it was customary for books containing any mention of sex to be introduced by an eminent physician,” Gaiman wrote, “whose function was simply to let the reader know” that “the book was safe and educational to read, and would not deprave the curious reader.” He recounted the tale of how Kiernan came to write for the series, explaining that she had gone on to make it into “her own, more personal book,” one “strange and personal and dark.” He added that she and “her collaborators are doing something cool and interesting,” before concluding, “I’m not a doctor. I don’t even play one on television. But I can assure you, curious reader, that the periodical you are holding will not excite your prurient interest, nor deprave you any more than you’re depraved already.” (1).

Gaiman thereby encouraged readers to recognize Kiernan’s sadomodern strategy of fusing memoir with fiction, one whose importance and originality he clearly understood. This strategy increasingly involved responding to the complaints of those readers who felt a sense of proprietary entitlement to the series not by catering to them, but by reifying their fears within The Dreaming itself. Kiernan wove the anxieties of such fans, with wicked ingenuity, into the narrative, and into nightmares, especially the nightmare now embodied by Echo. This is exemplary sadomodernism, ingeniously adapted to expose the contradictions and conventions of corporate studio comics.

2.4. Butlerian Echoes: Dreaming as Performance

In an analysis pertinent to the troubling of gender Kiernan performed with

The Dreaming, Brisbin and Booth read Gaiman’s

Sandman through Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity. They claimed that “Gaiman depicts in graphic form” the “gender-bending subversion that Butler advocates in a scholarly tone”, “casting aside the shroud of academia and making the theory accessible to a larger population.” (

Brisbin and Booth 2013, p. 21). One focal point of their discussion was Wanda Mann. As they explained,

Wanda is a pre-op male-to-female transgendered character in A Game of You who identifies and lives as a woman. She has breasts and takes hormones but has not had sexual reassignment surgery. In the book, the female characters embark on a mystical journey by harnessing the moon’s power. Wanda must stay behind while the other four female characters go to a different plane because the moon does not see Wanda as woman. (25)

They noted that while “Gaiman received some criticism for this,” he has consistently denied sharing the lunar deity’s view. They argued that rather than reifying essentialist assumptions, “Gaiman presents the conflict between socially-constructed gender and self-constructed gender as an aspect of a lived existence.” (25). While their reading of

Sandman is often insightful, Booth and Brisbin described Butler’s concept of “performance” as something staged, artificial, or immaterial. They wrote, “Gaiman renegotiates the traditional notions of gender in society and presents a practical representation of the same type of theoretical gender fluidity developed by Judith Butler in

Gender Trouble,” and that “Gaiman’s work, written around the same time as Butler published her influential treatise on gender performativity, illustrates the notion that sex and gender are social constructs which inherently lead to ideological oppression.” Their claim that “as both Gaiman and Butler argue, gender appearances are little more than artificial constructs” requires re-examination (25).

As Jack Halberstam pointed out, “Despite her rigorous critique of foundationalist notions of the gendered body, Butler has sometimes been seen as having questionable views on trans* politics” (

Halberstam 2018, np). Halberstam used the term “trans*” to refer to a wide variety of gender nonconforming behavior. He argued that the term “trans*” “holds open” meaning, “refuses to deliver certainty through the act of naming. The asterisk modifies the meaning of transitivity by refusing to situate transition in relation to a destination, a final form, a specific shape, or an established configuration of desire and identity. The asterisk holds off the certainty of diagnosis; it keeps at bay any sense of knowing in advance what the meaning of this or that gender-variant form may be, and perhaps most importantly, it makes trans* people the authors of their own categorizations” (

Halberstam 2018, np). Halberstam claimed the perception of Butler’s views as “questionable” stems from a misreading of Butlerian performativity as “’theatricality.’ This notion of a theatrical performance of self, some trans* activists felt, clashed with the sense of ‘realness’ that they struggled to achieve. Of course, these readings of performativity depended upon a prior mischaracterization of performativity as flexibility” (

Halberstam 2018, np). In order to correct this, Halberstam provided a succinct précis of the major implications of Butler’s work:

In her first two books, Gender Trouble and Bodies That Matter, Butler did the philosophical heavy lifting that allowed us to rethink bodily ontologies separate from the concept of a stable and foundational gender. Arguing that sex, the material of the body, is gender all along, she proposed that bodies are produced by discourse rather than being the sources of discourse. Once our understanding of the relationship between reality, materiality, and ideology has been remapped according to these inversions, it becomes possible to think about gender transitions in a way that doesn’t depend on a linear model of transformation, in which a female body becomes male or a male body becomes female.

Butler’s conception of bodies as “produced by discourse” is powerfully visualized in the crucial scene in

The Dreaming, in which Echo (“male,” but gender fluid) dies in the physical world, and is re-embodied within The Dreaming as “female” (

Kiernan and Artists 1998–2003, #36 19–21). This transformation can be read as The Dreaming’s reification of Echo’s subconscious awareness of her “true” gender; it makes her the woman she “really” is, and has always already been, in her dreams.

However, it can also be read as The Dreaming’s resolution of Echo’s gender trouble. Echo’s gender fluidity is now solidified by her assignation as “female”; she can be retrospectively recognized as having been so all along, in the timeless world of dreams. Either way, The Dreaming’s eponymous terrain works as a fictionalization of the preconscious discourse that shapes all thought and language (Dream is not called “The Shaper” for nothing), without which both “gender” and “sex” are equally meaningless, literally producing Echo’s new “female” body. This transition is neither Echo’s conscious choice, nor a piece of role playing. It is as “real” as everything else within The Dreaming’s visual narrative reality. This vividly encapsulates how discourse, in Butler’s sense, precedes and effectively makes the body, by “making sense of” the body, making the body matter, engendering it. Echo’s transition in The Dreaming offers a visualization of performativity as part of a “real” bodily ontology shaped by forces much deeper and less flexible than conscious choice or theatricality. Providing a fascinating counterpoint to Wanda’s rejection by a tragically TERF-y moon in “A Game of You,” it serves as a powerful visualization of Butler’s theory, while exposing the limitations of Brisbin and Booth’s earlier reading of Butler alongside Sandman.

However, despite Kiernan’s conceptual ambition and powerful, indirectly autobiographical writing, The Dreaming sometimes fails to fully realize her subversively sadomodern, gothic, and queer sensibility due to the inconsistent style and uneven quality of its illustrations. Of course, such unevenness is also an issue with Gaiman’s original Sandman series, but in The Dreaming it is more pronounced. Some of the series’ artists appear to have been as puzzled by or resistant to Kiernan’s conceptions as certain readers. Kiernan’s scripts, instructions to artists, and marginal notations on character sketches attest to the difficulties she had getting them to visualize various characters to her satisfaction. Her frustration with this becomes increasingly evident in marginal comments on draft pages during the concluding story arc, when crudely penciled disproportionate Dreams and ravens that look like taxidermized pigeons elicit red-inked declarations like “STINKY ART.”

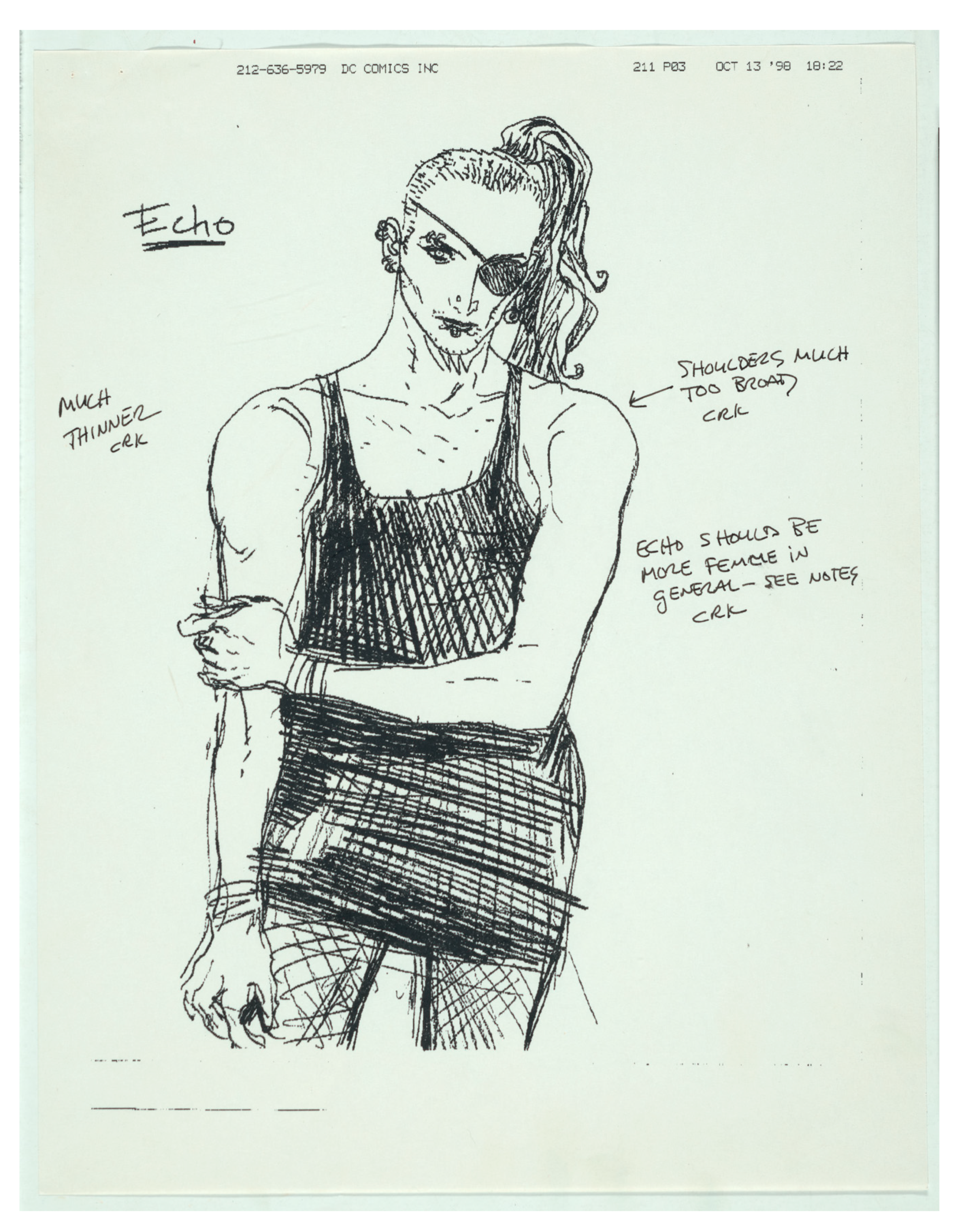

Such failures of the art to reflect Kiernan’s vision are themselves often illustrative of the way the fetishistic sexual dimorphism typical of superhero comics tends to erase nonbinaristic gender identities and expressions. Kiernan’s handwritten demands for artistic revision are at their most revealing where Echo’s character is concerned, both during his incarnation as a gender fluid human, and during her oneiric re-embodiment. Predictably enough, the initial sketches portrayed Echo, meant to be slender and androgynous, as a stereotypically bulky, bulgingly muscled figure (

Figure 1).

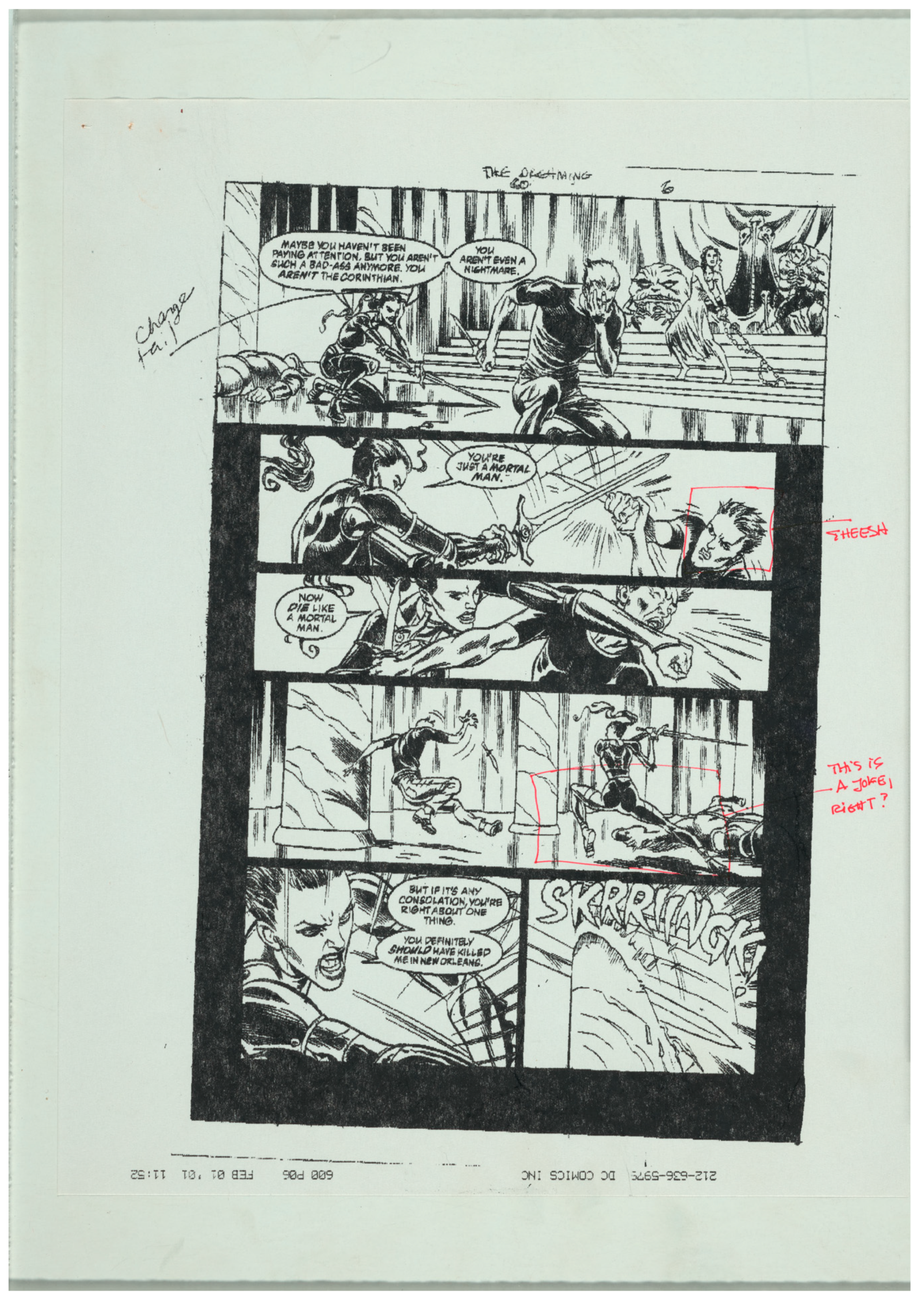

Then, after Echo’s transition, Kiernan repeatedly demanded revisions to a character now drawn as a sexual caricature, complete with tiny waist, thin limbs, and ample breasts and buttocks. This Echo is suddenly prone to bouts of brokeback posing and weirdly ballerina-esque prancing. Kiernan’s frustration with these crude, cartoonish tropes is clear from red-inked remarks including “THIS IS A JOKE, RIGHT?” (

Figure 2).

Given the ambitious sadomodernist strategy and Miltonic plot Kiernan pulled off with the series, it is telling that one of her greatest struggles involved getting the series’ artists to convey Echo’s gender fluidity. This struggle attests to the pervasive dominance of what Jose Alaniz aptly called “the super-body” over the world of American studio comics art. Such bodies are fundamentally fetishistic, founded in cisheterosexual, ableist fantasies of bodily mastery and control that effect a visual exclusion or abjection of those bodies that do not fit unambiguously within a binary paradigm. Kiernan collided head-on with the visual dominance of the super-body during her run on The Dreaming, and she continues to do so in her contemporary comics writing with Alabaster.