1. Introduction

Cynewulf has received scrutiny as one of the few named poets in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular due to the existence of four poems—

Elene, Juliana, Christ II, and

The Fates of the Apostles—that contain rune signatures bearing his name. The modern expectation is for an author to sign his work, but because manuscript collections of Anglo-Saxon poetry appear to have been intended for local audiences this was not the norm in medieval England (

Bredehoft 2009, p. 45). Cynewulf signed these poems to solicit prayers on his behalf, not due to an expectation of publication (p. 46). Due to the anonymous nature of the Old English poetic corpus, unsigned poems authored by Cynewulf may exist, but because we know so little about his biography, “the whole question of Cynewulf’s authorship is intimately tied up with the issue of style” (

Orchard 2003, p. 271). Scholars have categorized various poems that may share stylistic resemblance to the signed poems into a broader “Cynewulfian group” with some claim to authorship by Cynewulf or a subsequent school of devotees. Foremost among the Cynewulfian group is

Andreas. Found in the Vercelli Book along with

Elene and immediately followed by

The Fates of the Apostles,

Andreas tells the story of God’s calling of the disciple Andrew to rescue Matthew from bloodthirsty cannibals. The poem’s mix of heroic diction (evocative of

Beowulf) and didactic sermonizing (in the style of Cynewulf) is its most striking quality.

Scholars in the early nineteenth century were inclined to attribute the poem to Cynewulf due to stylistic similarities, such as similar formulaic language (

Bjork 2001, p. xvi). Later scholars have argued against this possibility based on grammatical and metrical differences, as well as its shared diction with

Beowulf (

Fulk 2001, pp. 7–8;

Greenfield and Calder 1986, p. 165). Although, a recent study of the style of Old English verse found a strong correlation in the use of compound words between

Andreas and the signed poems, leading the authors to entertain the possibility of Cynewulfian authorship as an area warranting further exploration (

Neidorf et al. 2019, p. 564). It is worth noting that

The Fates of the Apostles was once thought to be a part of

Andreas. If both poems were authored by Cynewulf, then the rune signature of

Fates could be applied to the set (p. 565).

Stylistic data have been used to support or refute a Cynewulfian attribution for Andreas, but interrogating these data for what they might tell us about the structure and composition of the poem itself has not been of primary concern. In order to accurately assess the style of a work, the critic must demonstrate its stylistic uniformity, because it would be inappropriate to generate a single authorial profile by conflating the contributions of multiple authors; however, such a demonstration has not been made with Andreas. The new critical edition edited by North and Bintley in 2016, for instance, makes no mention of the possibility of a composite nature despite recognizing the poem’s unusual fusion of Beowulfian and Cynewulfian traits.

The practice of repurposing poetic material is not without precedent in the Old English poetic corpus. Within the Cynewulfian group, the

Christ and

Guthlac poems found in the Exeter book are considered five independent poems rather than two long works (

Fulk 2001, pp. 5–9). Several other poems have also been shown to have a composite nature. In 1875, Eduard Sievers noted a stylistic division within the poem

Genesis, applying philological principles to identify a section of lines (now called

Genesis B), which were translated from Old Saxon (

Greenfield and Calder 1986, pp. 209–10). Drout and Chauvet use lexomic techniques to show that the “Song of the Three Youths” poem embedded within

Daniel is derived from an Old English version rather than Latin as supposed by Paul Remley (pp. 298–99). Most recently, Leonard Neidorf has marshalled compelling metrical and lexical evidence to demonstrate that

The Dream of the Rood, a poem from the same manuscript as

Andreas, can be divided into two components. The author of the first 77 lines of

Dream exhibits a superior command of Old English poetics to that demonstrated in the latter half, who may have been motivated to restore a damaged copy of the poem (pp. 68–70).

This paper re-examines the distribution of stylistic features within

Andreas to determine to what extent they are uniform and employs statistical analysis to describe and explain any observed variance. Such an investigation is a prerequisite for any endeavor dependent on identifying an author’s style. The critic should consider to what extent the observed variance may indicate composite authorship rather than deliberate intent of a single author. The discovery of unusual distributions of differentiated markers of style can be a hallmark of a composite work. “If sections of a work exhibit linguistic distinctions that cannot reasonably be attributed to chance or to the deliberation of a single author, credence in a theory of composite authorship appears warranted” (

Neidorf 2017, p. 53). Identifying a poem’s composite nature may also shed new light on dating the work, locate its place of composition, provide new historical information about editorial and poetic composition practices, and recover the outline of an earlier lost work. This analysis suggests that

Andreas is a composite work that can be divided loosely into two components: a shorter, earlier version which is plot-driven and typified by heroic diction in the style of

Beowulf and a set of later expansions, which is characterized by its affinity with Cynewulf.

2. Methodology

Scholars such as George Krapp have compiled lists of similarities and differences in terms of grammar and diction between Andreas and the signed poems. More recently, Andy Orchard has identified distinctive formulaic parallels and word compounds among these, as well as between Andreas and Beowulf. However, neither Krapp nor Orchard considered whether such stylistic elements are uniformly or heterogeneously distributed within the poem, and both scholars neglected to include a visual component, which, as Franco Moretti puts it, “shows us that there is something that needs to be explained” (p. 39). By plotting such data as a function of line number, it is possible to visualize and interpret the distribution of specific elements. Having done so, the data can be further correlated with other quantitative techniques, such as rolling window analysis and hierarchical, agglomerative cluster analysis as applied to Anglo-Saxon studies by the Lexomics Research Group at Wheaton College. Moretti also notes that quantitative analysis presupposes a formalism that “makes quantification possible in the first place” (p. 25). As such, it is important that the feature selected for quantification be grounded in a solid theoretical basis. The features quantified here—oral-formulaic phrases, word choice, and orthographic preferences—have long been cited by scholars as aspects of literary style, which, for the purpose of this analysis, are limited to an author’s choice of lexemes and, to a lesser degree, the way in which they are deployed within the context of Old English poetic metrics.

Whereas the oral-formulaic analysis works on the level of phrases, cluster analysis quantifies the frequency of individual words. Cluster analysis generates a statistical profile of an author’s style by measuring the frequency with which an author uses each word in a sample. Similar techniques—such as John Burrow’s Delta procedure—have been used to investigate questions of authorship in other domains, but these methods presuppose that the critic has access to a corpus of known works from a “closed” field of possible authorial candidates (

Burrows 2003, pp. 8–10;

Hoover 2004). The Delta procedure collapses an author’s statistical profile into a single “delta-score” defined as “the mean of the absolute differences between z-scores for a set of word-variables” (

Burrows 2002, p. 271). Burrows limited his analysis to the top 150 words in order to avoid the effects of domain-specific content words (p. 469).

1 Cluster analysis replaces the delta-score calculation with dendrogramming, the visual representation of relative affinity between texts, which allows word frequency profiles to be applied more efficaciously to “open” fields of largely unknown authors (e.g., the Old English poetic corpus), as well as within a single work, to investigate questions of internal structure (

Drout et al. 2011, p. 305;

2016, pp. 7–8;). Because cluster analysis does not use z-scores, the contribution of content words to the difference calculation is attenuated naturally by the effect of Zipf’s law and the fact that every text is directly compared to every other text, rather than against an average baseline.

One limitation of cluster analysis, especially when applied to questions of internal structure, is that it requires texts to be divided into “segments” that are compared relative to each other. The size and placement of the divisions can affect outcomes of the analysis, such as muting the effect of a particular feature or creating segments that are too small to measure word frequency with sufficient resolution (

Drout et al. 2016, pp. 11–12).

2 Rolling window analysis is a complementary technique, which overcomes this problem by generating a running calculation within a continuously shifting window of fixed size (

Drout and Chauvet 2015, p. 291). The sensitivity of the indicator is adjusted by changing the size of the window used. Grammatical, stylistic, metrical, or orthographic features of a text can be analyzed in this way. Drout and Chauvet have applied this technique to Old English texts by calculating a moving ratio of þ to ð. Because the two characters were often used interchangeably, changes in the trend of this ratio can correlate with differences in source, author, or scribal hand (pp. 315–16). Because rolling window analysis can be applied to orthographic data, it can be used to extract a line of evidence independent of word choice, syntax, and morphology. Because orthography can only exist in written texts, the cause of observed changes in orthography within a text is also more likely to be due to a written source.

As each methodological approach uses a different quantitative basis—the phrase, the word, the symbol—correlation between them can be a strong indication that a finding is present in the text under scrutiny rather than an artifact of the analysis tool. Each of these methods present data in a way that allows “‘emerging’ qualities, which were not visible at the lower level” to be discovered (

Moretti 2007, p. 53). When used in conjunction with more traditional qualitative approaches, quantitative tools provide new and complementary methods of interpretation that could lead to fresh insights.

3. The Distribution of Formulaic Language in Andreas

In his summary of the state of Cynewulf criticism, Fulk notes that “parallel passages [...] carry little weight now that oral-formulaic theory has shown the pervasiveness of formulae and their public, conventional nature” (

Fulk 2001, p. 5). However, Orchard asserts that “the ‘white noise’ of traditional and inherited formulae” can be filtered out by limiting one’s scope to specific formulaic language unique to the works under inquiry (

Orchard 2003, p. 273). One must refrain from absolute pronouncements for or against the usefulness of formulaic language per se. Some formulae considered distinctive today by Orchard’s system were probably widespread at the time, while others only seem commonplace now due to selection bias—our sample size is constrained to the manuscripts that survived. Nevertheless, if certain formulae were unevenly distributed throughout a literary or oral tradition by region, time period, or “school”, then Orchard’s approach should capture these tendencies in the aggregate, despite uncertainty regarding any formula on its own. Furthermore, the efficacy of this approach can be confirmed when correlated with other independent methods.

Having quantified a large number of shared formulae between

Andreas and the signed poems, Orchard concludes that his “figures strongly suggest either unity of authorship or conscious literary borrowing”, opting for the latter on the basis of Fulk’s evidence (which extended Krapp’s original argument) of divergent diction (p. 287). However, Orchard’s data can be applied to more than just the authorship question.

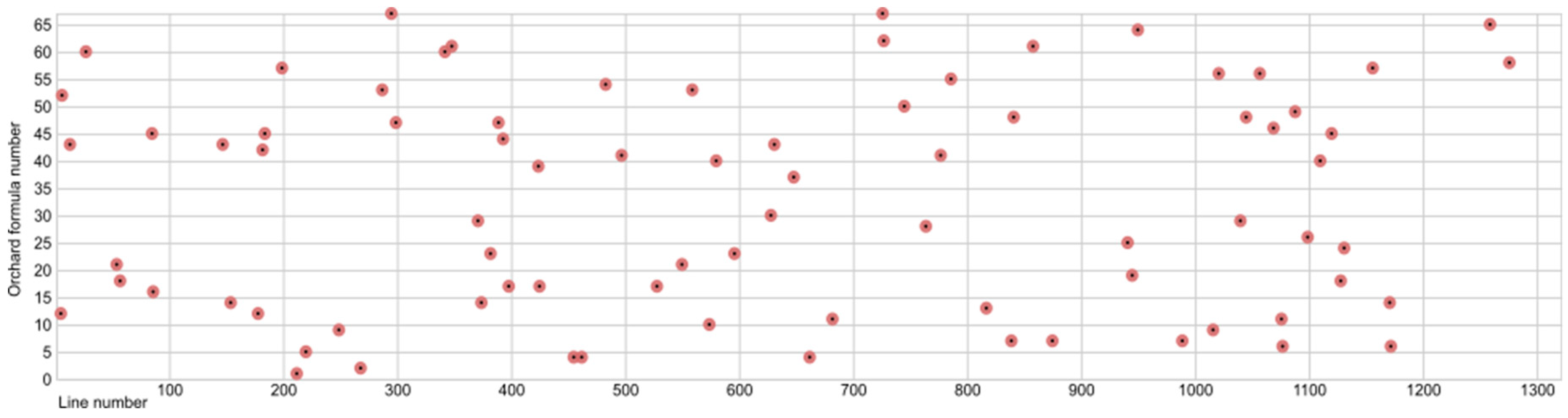

3 When plotted by line number, it becomes apparent that Cynewulfian parallels are not evenly distributed throughout the poem (

Figure 1).

Figure 1 shows four sections of

Andreas where no such parallels have been found. It is important to note that this does not mean that formulaic language is wholly absent from these sections but, rather, that distinctively Cynewulfian formulae are missing. The vertical scale represents an arbitrary identification number assigned to each formula by Orchard, so the linearly increasing pattern of the

Andreas plot is not significant. The horizontal distribution is what is of concern here.

As a comparison,

Figure 2 plots the Cynewulfian formulae from

Elene.

Elene is an ideal control for comparison, as it is signed by Cynewulf, of similar length, and from the same manuscript as

Andreas. The distribution of Cynewulfian formulae is tighter, with the largest distance between formulae being 87 lines (or 6.5% of the poem); the length in lines of three of the four

Andreas sections identified exceed this distance.

4This difference in distribution between the two poems can be quantified by comparing histograms of the distances between each formula (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In

Andreas, the average distance between formulae is 39 lines (2.2%) to

Elene’s 16 (1.2%).

Andreas’ histogram also has a distinctive “long tail”, which is absent from

Elene’s. The frequency of

Elene’s formulae does vary throughout the poem, but there are few long stretches without such language—a pattern indicative of stylistic consistency. If the bounds of the

Elene histogram are applied to

Andreas to denote sections of consistent formulaic style, then those sections that fall outside this area can be interpreted as discontinuous—the style starts and stops. In other words, in

Elene, the Cynewulfian formulaic language ebbs and flows; in

Andreas, it stutters.

Scholars generally agree that Cynewulf used a Latin prose exemplar when composing

Elene, and yet,

Elene does not exhibit a similar pattern in its formula distribution where Latin source influence is detected (

Anderson 1983, p. 103). Likewise, an analysis of where

Andreas differs from its closest Latin exemplar in the Casanatensis manuscript does not show any clear correlation with the discontinuities in Cynewulfian formulaic distribution (

Friesen 2009, pp. 301–7). This difference in distribution pattern suggests that these sections lacking Cynewulfian formulae in

Andreas have a distinctly non-Cynewulfian bias. The fact that the formulaic language is discontinuous rather than relatively less frequent suggests that the source was not merely a reference—such as a Latin prose narrative like the

Vita Cyriaci or the Casanatensis prose exemplar—but an Old English poem, which could be incorporated into a larger poem with little editorial work.

4. The Narrative Content of Andreas A and B

For the purpose of analysis, the four sections that show no distinctive Cynewulfian formulae as described above are called

Andreas B, whereas the parts in between the

B sections are called

Andreas A. This divides the poem into nine parts, as outlined in

Table 1. Six of these breaks appear in the middle of a sentence or thought, but the boundaries have not been modified to coincide with syntactical hints to preserve the quantitative basis for the divisions.

A close reading of the B sections shows that a coherent outline of Andrew’s story is described therein. Taken on its own, it tells the story of Andrew’s calling by God, the rescue of Matthew from the Mermedons, and the cleansing of the city with almost all the key plot points included. It does so using only 33% of the extant lines. However, there are two notable plot holes in Andreas B. First, the reader is unsure how Andrew finds himself amid a storm at sea without section A1. Second, the actual capture of Andrew by the Mermedons is missing without section A4. How these components of Andreas B may be recovered is discussed in the next section.

The A sections do not significantly advance the plot. These parts are preoccupied with the events of Andrew’s journey and his torture in prison. Despite the absence of major plot points, they comprise 56% of the extant lines. (As literal edge cases, the two pieces containing the introduction and epilogue are set aside for now.) Nevertheless, Andreas A has its own exclusive themes. The topic of Andrew’s skepticism is treated only in Andreas A and frames stories of unbelief in the face of miraculous signs. The explicit identification of the helmsman as God is found almost entirely in Andreas A as is Andrew’s torture in simulation of Christ’s passion.

Andreas A adds several aspects to the sea voyage passage, which change the whole character of the episode. For instance, the conflict in Andreas B’s sea voyage is the storm not the distance. There is no mention in Andreas B that a three-day voyage to Mermedonia from Achaia would require miraculous intervention; this is an Andreas A concern. Moreover, if not for the poet’s use of “ece dryhten” (eternal Lord) in reference to the captain in line 510, section B2 would read like an exchange between pious mortals, which may or may not intend to imply that the helmsman is God. A later editor wishing to make that implication explicit might include material such as that found in Andreas A.

The A sections also create problems that do not exist for Andreas B when it stands on its own. The famine and subsequent torture of Andrew make the poem less coherent. In Andreas B alone, the precise capture of Andrew is unclear—perhaps it is the result of an attempt to rescue the innocent boy—but there are no obvious inconsistencies present. Andrew “thought [the boy’s plight] miserable” (earmlic þuhte) but takes no action as the poem crosses over to Andreas A where God’s perfunctory rescue of the boy renders the whole episode rather pointless (lines 1135; 1143b–44). Furthermore, it sets off a period of famine predicated on the notion that cannibals, who have been shown to be capable of eating their own kind, no longer do so (lines 1155–62a). During this time the reader must presume that Andrew is living voluntarily in a famine-wracked city when he could have left with Matthew or any time thereafter. In addition, once captured, the starving citizens show little interest in actually eating him (lines 1249–50a). From a narrative perspective, section A4 can be interpreted as a justification to extend the story with a passion scene.

Nevertheless, these events are not the invention of the

Andreas A poet, as they also appear in the prose retelling of the Casanatensis manuscript (

Friesen 2009, pp. 301–7;

Greenfield and Calder 1986, p. 159). It is likely then that the

Andreas A poet knew or referenced a source such as Casanatensis. Likewise, the absence of these features in

Andreas B suggests that the

Andreas B poet did not learn the story from such a written source. In fact, a desire to harmonize the

Andreas B poem with a Latin prose exemplar may be the reason the project of revising

Andreas B was taken up.

Both the A and B sections are internally consistent, but several plot problems manifest when they are read together. The Andreas B material contains the core of Matthew’s rescue narrative and is characterized by an absence of distinctive Cynewulfian formulae. However, the Andreas A material constitutes asides or digressions of a homiletic or didactic nature and is highly correlated with such formulae. This dichotomy suggests that Andreas B represents a non-Cynewulfian source, which has been expanded upon.

5. Affinities with Beowulf in Andreas B

In “The Originality of

Andreas”, Orchard compiles a list of parallel passages and distinctive compound words used between

Andreas and

Beowulf. A third dataset enumerates the uniquely shared compounds between

Andreas and the signed Cynewulf poems. A fourth lists compounds unique to

Andreas alone. By close investigation of these lists, Orchard argues that the

Andreas poet innovates new compounds in dialogue with language borrowed from

Beowulf and the signed poems (

Orchard 2016, p. 333).

Table 2 tabulates these occurrences against the

A and

B sections described above. Each absolute count is corrected for the size of the section, resulting in an “occurrence per line” score.

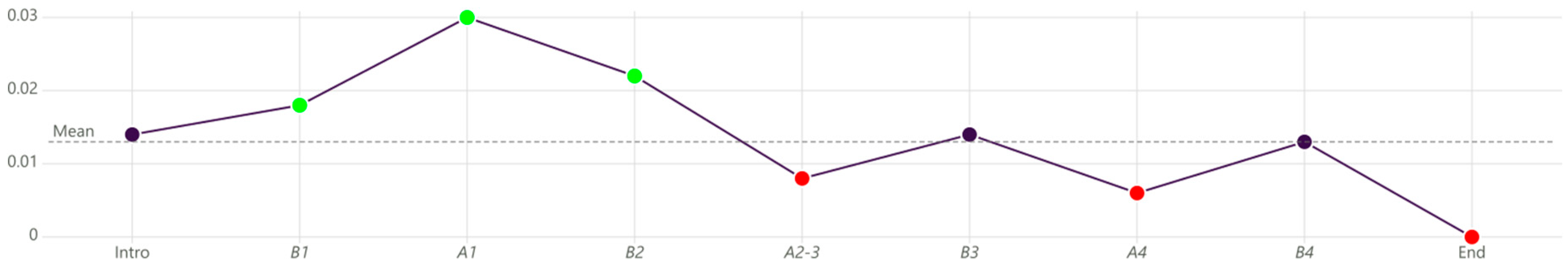

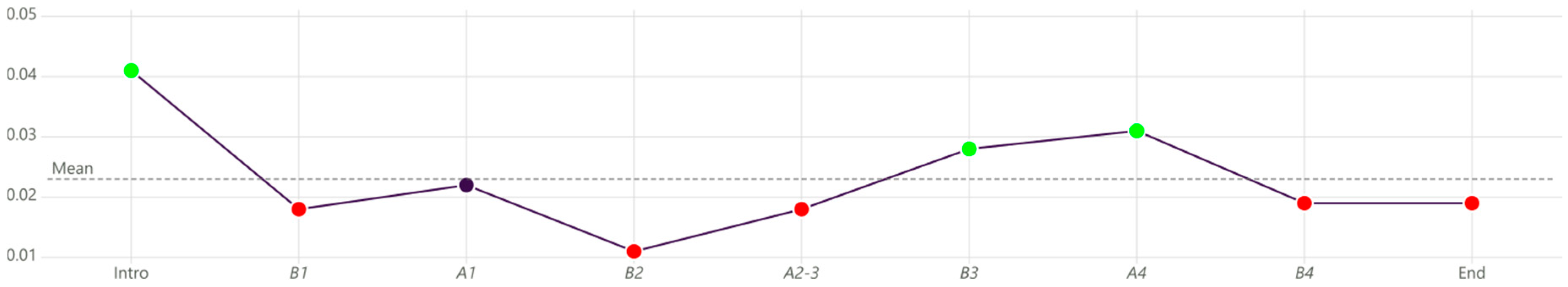

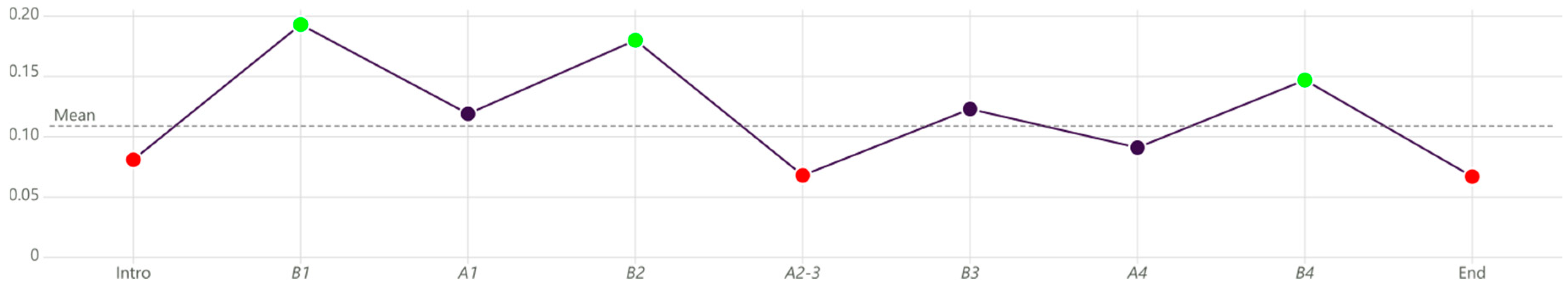

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 plot the “occurrence per line” scores from

Table 2 against the mean for each metric. Scores deviating more than 20% from the mean for their group are flagged green (if above) or red (if below).

The Beowulfian parallels and compound words are present particularly in the sea voyage episode (sections B1/A1/B2). Section B3 is also heavily weighted with Beowulfian compound words. Except for section A1, the A sections exhibit low affinity to Beowulf by this metric. Despite its high Beowulfian scores, section A1 has the highest Cynewulfian affinity as measured by word compounds among the sea voyage triad. The Cynewulfian word compounds are distributed more broadly throughout the poem, but three of the four B sections have scores below the mean—also supporting the interpretation that Andreas B has a non-Cynewulfian bias. Despite lacking distinct Cynewulfian formulae, section B3 registers high on the Cynewulfian compounds metric. This may indicate that this section has been reworked more by the Andreas A poet than the rest of the Andreas B material. The dataset was intended to capture the most innovative word compounds—those compounds unique to Andreas—which also disproportionately occur in the B sections (p. 340). Nevertheless, innovative compounds are also well attested in the A sections, which implies that these phenomena are not original to the Andreas B material. Therefore, the originality in word coinage Orchard identified as a stylistic hallmark of Andreas can be interpreted as an editorial technique used by the Andreas A poet to retouch the Beowulfian sections.

A closer look at section

A1 reveals that most of the flagged Beowulfian content is contained in fitt iv—the portion adjacent to section

B2. If section

A1 is subdivided into two parts—fitt iv and the remainder, which we will call section

A1′—then the Beowulfian occurrence per line score decreases by 30% for section

A1′, whereas fitt iv scores the highest of all the segments investigated (

Table 3).

Half of the Beowulfian markers in fitt iv are found between lines 359 and 376, which also contain no Cynewulfian compounds:

The holy one sat himself near the helmsman, noble one by noble one. I had never heard of a more beautiful ship laden with splendid treasure. The warriors sat there—lords full of glory, beautiful thanes. Then spoke the mighty king, eternal Almighty, ordering his angel—glorious young retainer—to go and give meat to comfort the poor ones over flood’s whelming, that they might more easily endure their condition over the waves’ throng. Then it became disturbed, that shaken sea. The whale frolicked, glided through the ocean, and the gray gull roamed eager to prey on the dead. The weather-candle faded, winds waxed, waves crashed, currents stirred, ropes snapped, and garments were soaked through. Dreadful waters stood, pressing with force. The thanes became terrified (lines 359–76a).

5

This particularly Beowulfian passage embedded within section A1 fills the first of the narrative gaps observed in Andreas B above—Andrew’s boarding of the boat and the beginning of the storm. Without the Andreas A context, God’s command to the attending angel in lines 364–66 need not be interpreted as a reference to the boat’s crew. This supports the hypothesis that the original poem did not include a divine helmsman, making the device a later addition by the Andreas A poet.

One might argue that the sea voyage exhibits high affinity with Beowulf, not because of divergent textual history, but because the Andreas poet intentionally referenced Beowulf during composition considering the common content. This argument does not well explain the high Beowulfian affinity in section B3, which has fewer themes and motifs in common with Beowulf, nor the extremely low scores for sections A2–4. It would be striking that so few Beowulfian parallels and formulae exist in Andreas A if the poet had access to such a resource. Such an interpretation is further weakened if the Andreas A and B types can be shown to have distinctive affinity for their own type, which would further support the hypothesis of a composite nature. This possibility is investigated below using cluster analysis.

Finally, there is the question of how Andrew was captured in the original Andreas B poem. Similar to the passage discussed above from fitt iv, one would expect Beowulfian characteristics to be correlated with those events in section A4, because they would be more likely to have been adapted from the Andreas B poem. In section A4, two short passages are correlated with both Beowulfian parallels and compounds. Beowulfian parallels are underlined and compound words are bolded. The first describes Andrew’s capture:

Drogon deormodne æfter dunscræfum,

ymb stanhleoðo, stærcedferþne,

efne swa wide swa wegas to lagon,

enta ærgeweorc, innan burgum,

stræte stanfage. (lines 1232–36a)

[The brave-minded one was dragged by the cruel-hearted along mountain caves, around rocky slopes, even so far as the sea-way, by the ancient work of the giants, within the cities with stone-cobbled streets.]

The second passage begins Andrew’s lament:

Næfre ic geferde mid frean willan

under heofonhwealfe heardran drohtnoð,

þær ic dryhtnes æ deman sceolde.

Sint me leoðu tolocen, lic sare gebrocen,

banhus blodfag, benne weallað,

seonodolg swatige. (lines 1401–6a)

[Never have I born by the Lord’s will such a sore living under the vault of heaven where I must deem life the Lord’s. My limbs are separated, my body sorely broken, bone-house blood-stained, wounds welling up, sinew-wounds sweaty.]

It is hard to say how much of the surrounding lines might go back to the earlier version of the poem, but one can see how these lines might encourage expansion into a longer passion set piece.

6. Evidence from the Moving Ratio of þ to ð

If the Andreas A/B hypothesis is accurate, then the distinction should be detectable via other methods sensitive to differences in textual history. Drout and Chauvet have shown that by calculating the moving ratio of þ to ð in Anglo-Saxon poetry and noting discrepancies in its variation—such as a change in trend direction—one can generate “evidence of differences in textual history for particular segments of Old English poems”, as the orthographic tendencies of an exemplar leak into the copied text (pp. 315–16).

By counting the number of þ characters in a segment of text and dividing the result by the combined number of þ and ð in the same segment, one can calculate the relative percentage of þ characters in the text. If one does this calculation with a segment size—called the “window”—that is a fraction of the size of the text of interest, then the window can be moved along the text, generating a value at each offset. Such a calculation is called a moving ratio and can be plotted as a graph with the offset in the X axis and the value in the Y axis. One can, in principle, calculate a moving ratio of any quantifiable feature. In the case of þ/ð, their ratio will visualize where in the poem the scribe uses more þ than ð, and vice versa. As noted above, changes in the direction of the trend of the ratio suggest that something prompted the scribe to alter the frequency with which he used one or the other symbol.

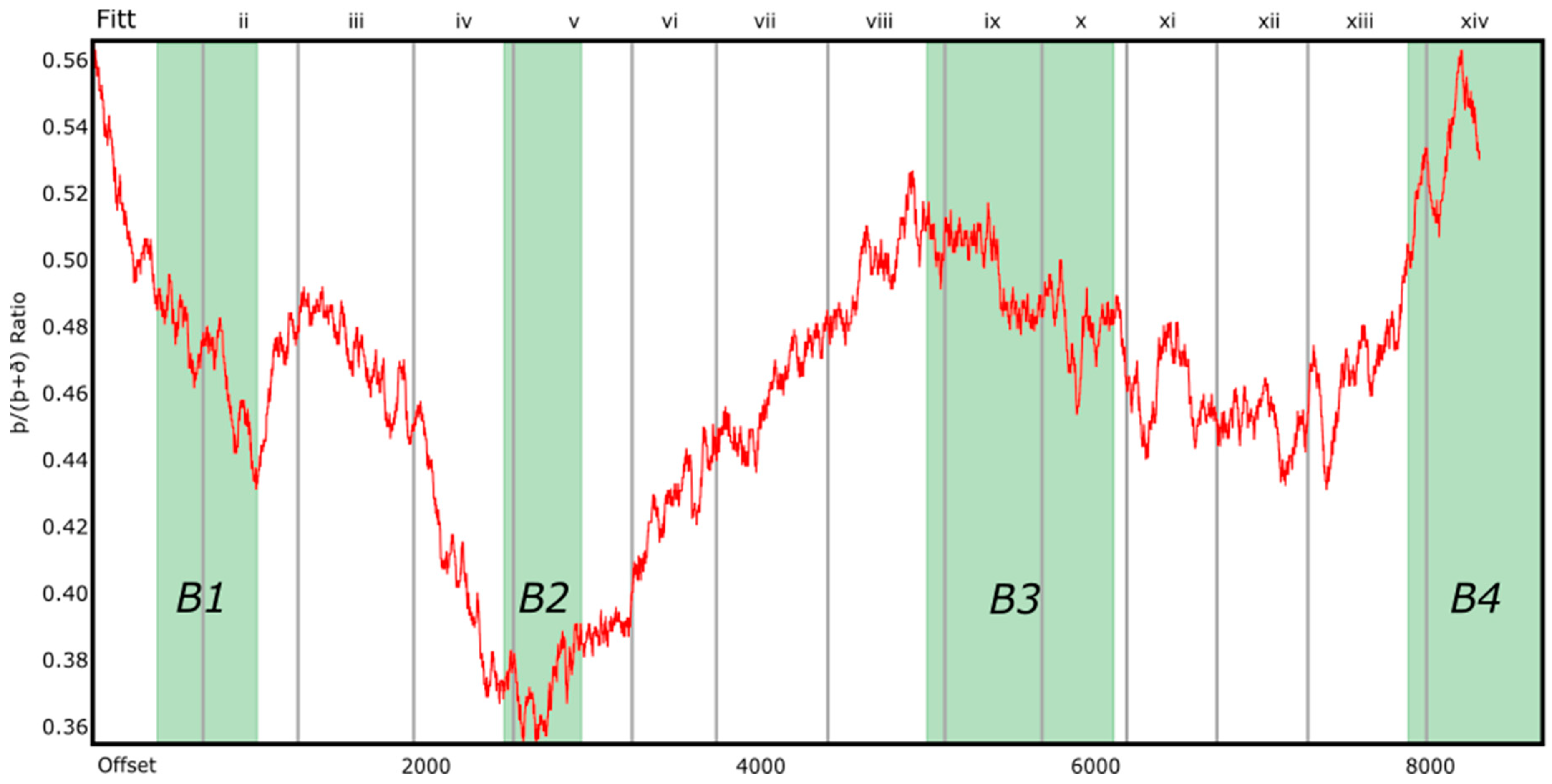

Figure 9 plots the moving ratio of þ to ð for

Andreas using a window of 1000 words, overlaid with manuscript fitt demarcations and

B section boundaries. Each

B section correlates to a change in trend of the ratio. The initial downtrend stops temporarily at the end of section

B1. The end of section

B2 begins a new uptrend that reverses with the start of section

B3. Finally, the beginning of section

B4 correlates with the last uptrend in the ratio.

The size of the rolling window used to calculate a moving ratio affects the sensitivity of the indicator. Larger windows can filter noise from the time series but can also obscure effects due to more complex textual structures (

Drout and Chauvet 2015, pp. 291–92). A smaller window can be more responsive to changes in the feature being measured and therefore be able resolve smaller features, but this comes at the expense of additional noise as each instance carries greater statistical weight in smaller windows. It is, thus, good practice to deploy larger windows for identifying major trends and then apply smaller windows to “zoom in” on areas of interest where the presence of smaller features is suspected.

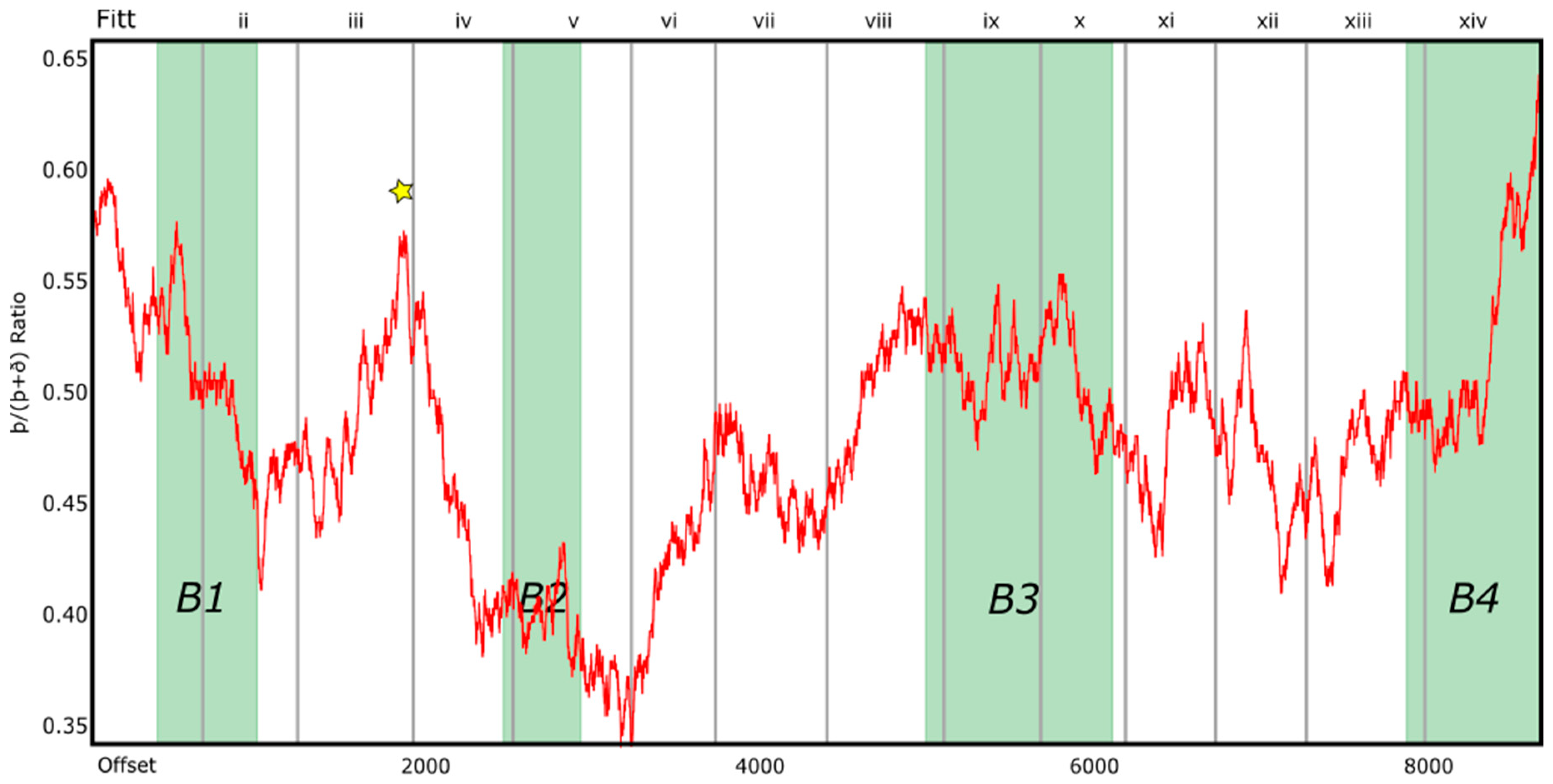

One such area is section

A1, as the analysis of oral-formulaic data above suggests that this section contains a mix of Cynewulfian and Beowulfian content. The major downtrend shown in the ratio between fitts iii and iv in

Figure 9 corresponds to this section. Calculating the ratio with a window of 500 words brings out a feature at the break between fitts iii and iv. The downward trend appears contiguous with a window of 1000 words, but at a window of 500 words, the trend of fitt iii is reversed, correlating to the anomalous Beowulfian features in fitt iv described above (

Figure 10). Likewise, the once-contiguous upward trend between fitts vi and vii with a 1000-word window is flipped to a downward trend in fitt vii with a 500-word window, which marks a possible milestone for segmenting this large

Andreas A section for cluster analysis. Fitt vii marks the beginning of the story of the stone angel come to life.

Drout and Chauvet also tentatively hypothesize that a low level of þ (or equivalently, a higher percentage of ð) could indicate older provenance, as ð may have entered Old English orthography first (p. 295). Three of the four B sections occur during downtrends in the ratio, which indicates lower þ counts. In particular, the sea voyage passage records an extremely low þ percentage. This result also holds for fitts iii and iv—fitt iv contains more Beowulfian content and exhibits lower þ counts than fitt iii.

This moving ratio quantifies orthographic tendencies, not stylistic language. Therefore, it can be considered an independent line of evidence in favor of the Andreas A/B hypothesis. Passages with Beowulf affinity are correlated with a decrease in the proportion of þ, which suggests that they may be relatively older than passages with Cynewulfian affinity.

7. Other Orthographic Evidence

Andreas A and

B can also be distinguished by their differing use of the acute accent. North and Bintley note that “the text of

Andreas is distinguished from that of all other items in the Vercelli Book by the use of an acute accent to mark stress in ten instances of the short-vowelled OE word for ‘God’, as

gód”, which they conclude is a “harbinger of later practice” (

North and Bintley 2016, p. 22). As a later practice, one should expect accented

gód to be more correlated with

Andreas A. Note that this hypothesis need not rest on the premise that the orthography itself originates with the

Andreas A poet but only that the particular use of stress in the poem, which prompted the scribe to use the accent mark, does.

Table 4 tabulates these occurrences against the

Andreas A/

B division.

The absence of accented gód prior to section A2 is a clear distinction between the sea voyage episode and the rest of the poem. In addition, over half of the occurrences are found in the A2–3 segment, which is the passage most aligned with the identified concerns of the Andreas A poet. The small amount of accented gód found in the later Andreas B segments is consonant with the earlier inference of more editorial reworking of these Andreas B sections by the Andreas A poet.

Unfortunately, North and Bintley do not apply these data to the task of stylistic analysis of Andreas. They argue that this is evidence of the production of folios 39 recto to 46 verso of the Vercelli Book by a scribe in Wilton associated with St. Edith, whose name may appear in a half-erased colophon (pp. 21–26). Perhaps it is so, although this interpretation does not explain why the half dozen instances of god (meaning ‘God’) in the first third of the poem remain unmarked.

8. Evidence for the Andreas A/B Division from Cluster Analysis

Having established a quantitative basis for the

Andreas A/B division in

Andreas, hierarchical, agglomerative cluster analysis can be used to establish whether the sections of each type show greater affinity for their own type. This technique has been used to detect internal structure in

Guthlac A and its Latin exemplar,

Genesis A and

B;

Beowulf; and the Christ poems (

Downey et al. 2012;

Drout et al. 2011,

2016). By dividing the text of

Andreas into segments and comparing their word frequency profiles with each other, cluster analysis will group more similar segments closer together on the tree diagram. If

Andreas A and

B each have a consistent word frequency profile within themselves, then their segments should cluster together.

Cluster analysis calculates the frequency of every word used for each segment. The relative “distance” between each segment can then be measured as the sum of the differences of their word frequencies. A diagram, called a dendrogram, is constructed from these data to visualize the relative affinity between segments. Each segment is a terminal “leaf”. Leaves are grouped together into clades. The relative distance is displayed at the nodes where leaves and clades meet. The size of the vertical bars are also determined by relative distance. To put it simply, the farther away two segments are from each other, the less they have in common.

Manuscript fitt and

B section boundaries were used to divide the poem into 10 segments.

Table 5 lists the segments and word count contained in each. Experimental evidence has shown that cluster analysis is efficacious when segments are between 400 and 1500 words (

Drout et al. 2011, p. 313).

A sections showing affinity to

Beowulf have been subdivided in order to facilitate the possible blending strategies described below.

Performing a basic cluster analysis, excluding the introduction and epilogue, the

B sections tend to cluster separately from the

A sections, with the shortest

A segment as the exception (

Figure 11). The shortest segment, section

B2, is least alike of all, clustering as a simplicifolious clade. In fact, the stepwise nature of the dendrogram suggests that several segments may be too small to quantify their word frequency profiles sufficiently.

In Beowulf Unlocked, Drout suggests blending as one possible strategy for dealing with subsections, which are too short or interleaved (p. 12). Blending is the act of combining two or more non-contiguous segments together to create a sufficiently large segment of uniform content. The justification for blending two segments should not be predicated on their affinity in a cluster analysis to avoid circular reasoning. Several possible blending strategies are evident from the analysis thus far:

Blend sections B1 and B2, as both are short B sections.

Blend fitt iv from section A1 with section B2 considering its Beowulf affinity.

Blend sections A2 and B2, as both contain conversations with Jesus.

Blend sections A2 and A3, because the þ/ð and Cynewulfian formulaic trends are continuous.

Blend the introduction with section B1 and section B4 with the epilogue, because formulae are sparse on the edges.

Blend the introduction and epilogue.

The techniques of incrementation and truncation

6 were used to observe how each blending strategy affected the dendrogram (p. 13). Across blending strategies, the

A sections tend to cluster together in a clade, whereas the

B sections either cluster on their own or as a stepwise pattern separate from the

A clade. When section

B2 is blended with either section

B1 or section

A2, the resulting segment will cluster within the

A clade. If section

B2 is blended with fitt iv, then it pulls section

A1′ out of the

A clade and they combine to create a clade of especially Beowulfian material (

Figure 12). Note also that the position of the Beowulfian clade shows more affinity to the

B sections than the

A sections. This result indicates that

Andreas A and

B each have a word frequency profile distinct from the other and that significant portions of section

A1—fitt iv in particular—are also likely to contain remnants of

Andreas B.

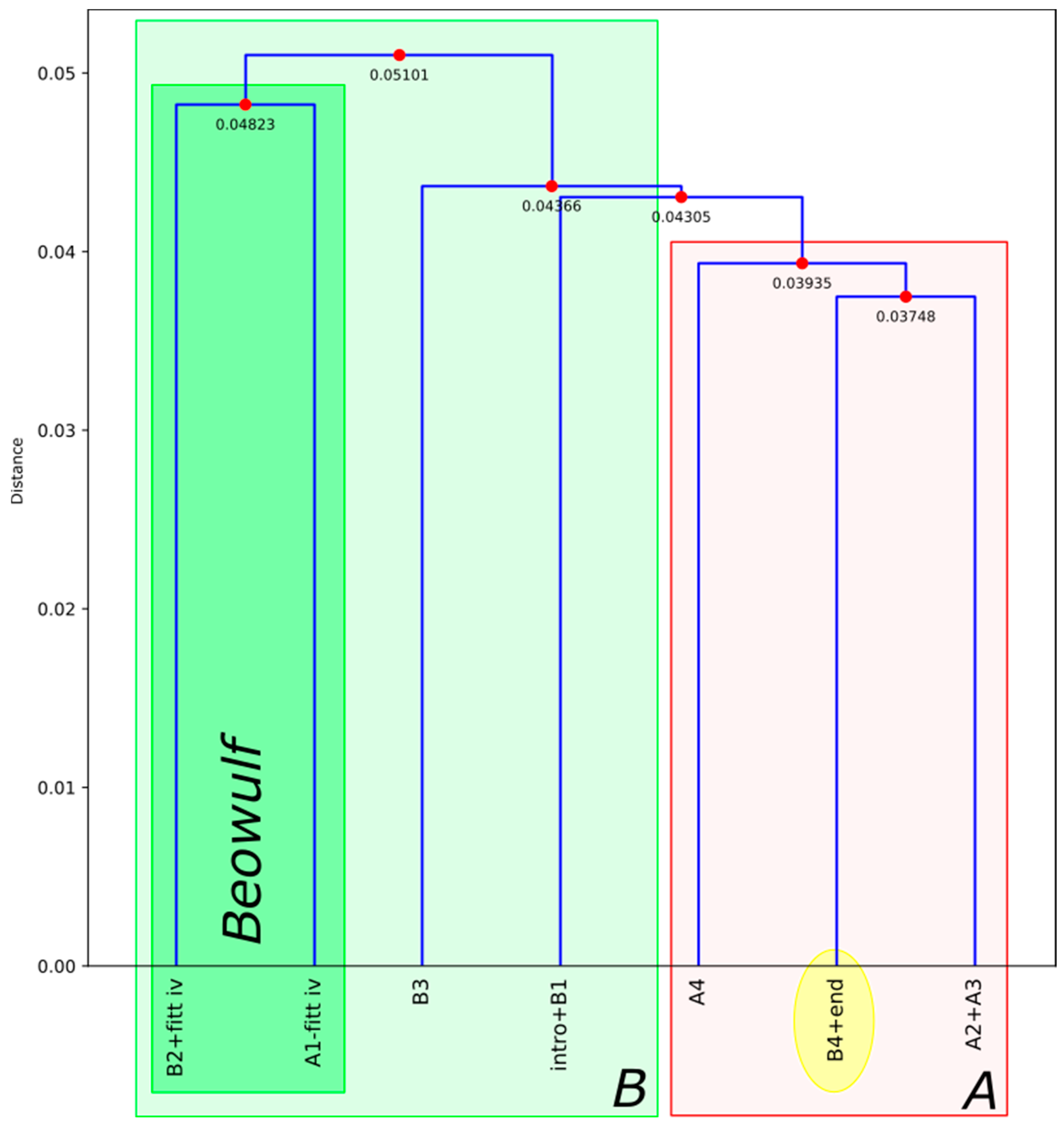

When the edge segments are introduced on their own, blended together, or blended with their adjacent

B sections, the edge segments tend to show an affinity with the

B sections. However, when the epilogue is blended with section

B4, it clusters in the

A clade, suggesting that the epilogue has more affinity with the

A sections than does the introduction (

Figure 13). It is worth noting that although the edge segments have the same number of Cynewulfian formulae, they are more evenly distributed in the epilogue; the formulae in the introduction are bunched up near the

B1 boundary.

Cluster analysis supports the view that the A and B sections have an affinity within themselves and that there exists a Beowulfian affinity between sections A1 and B2. It also shows that although the edge segments have a general affinity to the B sections, the end exhibits relatively more affinity to the A sections than the beginning.

9. Cluster Analysis within the Cynewulfian Group

Thus far, cluster analysis has been deployed for the purpose of investigating the internal structure of the poem, but it can also be used to compare relative affinity within a set of texts (

Drout et al. 2011, pp. 323–25). When doing so, one must be careful to account for possible orthographic differences, such as spelling variation or þ/ð tendencies of different scribes, which could bias the results (

Drout et al. 2016, pp. 17–18). For the following cluster analysis, common variances were consolidated, and the top 50 most frequent words were manually checked for spelling variation.

7 The

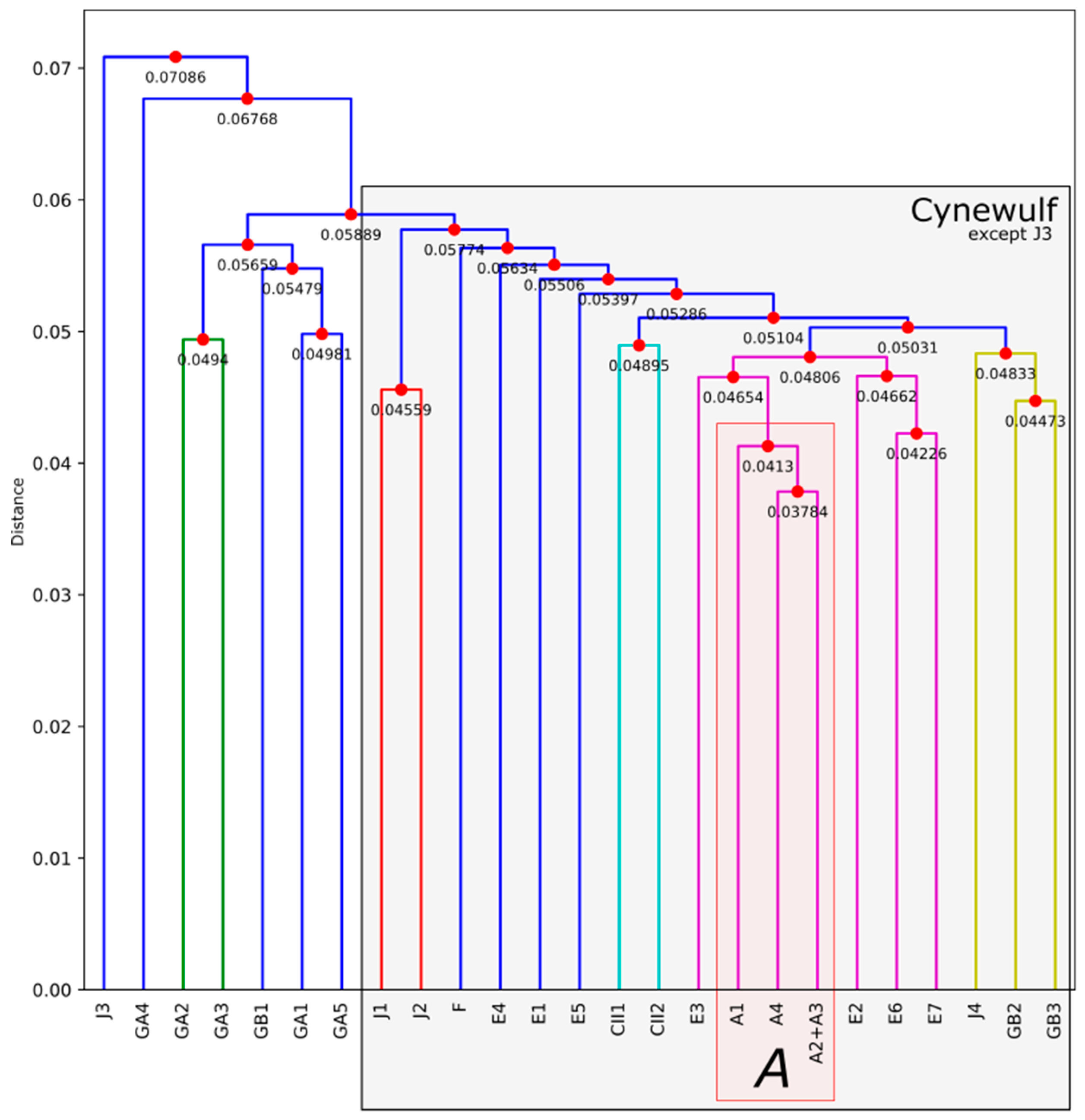

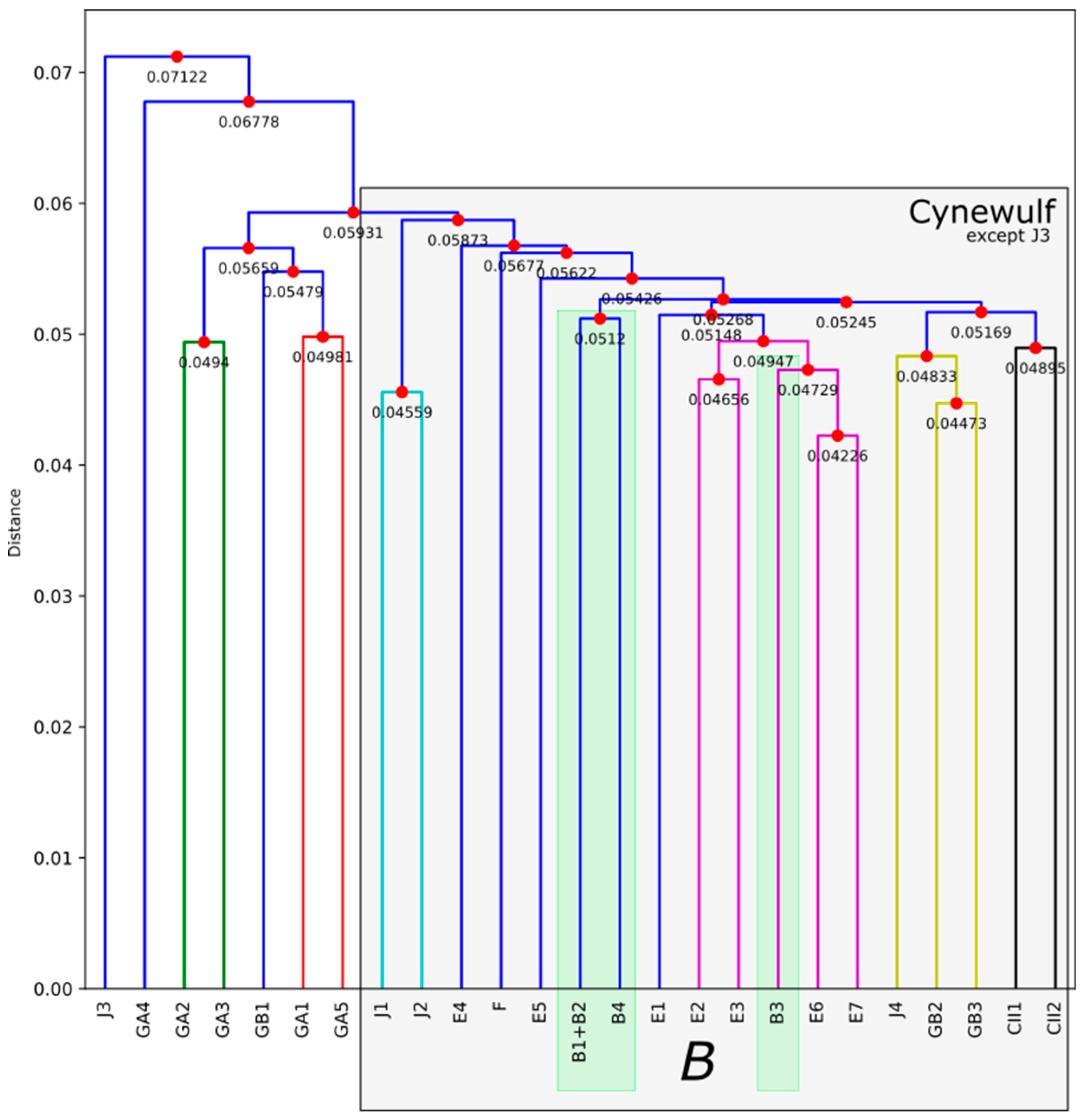

A and

B sections were injected into a dendrogram made up of the wider Cynewulfian group of poems as described by Drout et al. in “Of Dendrogrammatology” (p. 325).

8 Signed poems by Cynewulf form their own clade

9 along with

Guthlac B, which has a strong claim to Cynewulfian authorship itself (

Fulk 2001, p. 5). If both the

A and

B sections are injected at the same time, all of

Andreas will collapse into its own clade, but, taken separately, one can see how they each have a different level of affinity for the signed Cynewulf works.

Andreas A clusters within the innermost Cynewulfian clade along with the majority of

Elene, demonstrating its high Cynewulfian affinity (

Figure 14). However, when

Andreas B is injected, only section

B3 clusters within the

Elene sub-clade, whereas the rest is relegated to the fringe of the larger Cynewulfian clade (

Figure 15). This result indicates that most of

Andreas B is only minimally similar to signed Cynewulfian work, although section

B3 has a more Cynewulfian bias than the rest.

Cluster analysis across the Cynewulfian group shows that the A sections have a stronger affinity with signed Cynewulf work than the B sections. The clustering of section B3 within the Elene sub-clade accords with the evidence from the distribution of Cynewulfian word compounds. This evidence supports the view that the B sections were reworked by a later poet, who integrated them with the A sections, with section B3 being the most heavily revised.

10. Arguments against Cynewulfian Authorship of Andreas

Several critics have noted grammatical and stylistic features that distinguish

Andreas from the signed poems.

10 George Krapp outlined such a list of differences, to which R.D. Fulk added several metrical distinctions (

Krapp 1905, pp. xlviii–xlix;

Fulk 2001, pp. 7–8). These items can be divided into two types:

The latter items are not quantifiable, because they do not appear in

Andreas. However, the uncharacteristic lexemes in

Andreas can be correlated to the

Andreas A/B divisions previously described (

Table 6). Fulk cites eight such differences taken from Krapp:

ondswarode, dative

fæder,

sin,

æninga,

becweðan,

feorr,

æfter þam/þyssum wordum, and

wordum/worde cwæð. These represent 51 instances. Almost 75% of these phrases are in the

A sections even though the

A section lines constitute only 57% of the poem.

Most of the additional differences listed by Krapp also predominantly appear in the

A sections, including the phrases

ða gen/git,

sum + a genitive plural,

eft swa ær, lyt, and an overuse of

siððan. As the anomalies enumerated by Krapp and Fulk disproportionately apply to the

A sections of the poem, this line of inquiry also supports the view that

Andreas A and

B have distinct styles. However, the implication inverts expectations—content that is unlike Cynewulf should not be predominantly found in

Andreas A. One reasonable explanation is that these lexemes originated in

Andreas B. In several cases (such as the uses of

sin and

ondswarode), Fulk notes that the Andrean tendencies are the more archaic forms (

Fulk 2001, p. 7;

Fulk 1992, p. 242). Almost all types mentioned (dative

fæder is the exception) are also extant in

Andreas B. Having examples in

Andreas B, which he chooses to retain, the

Andreas A poet uses the lexemes in his expansion as well.

Finally, Krapp concludes his list of anomalies by citing Fritzsche’s observation that, unlike signed poems,

Andreas “nowhere alludes to any written sources” (p. xlix). However, in lines 1478–91 the poet breaks into the narrative by referring to himself in the first person. He expresses his humility as a poet and reminds the reader of the

fyrn-sægen (ancient sayings) about Andrew’s story. Although this passage is contained in the

B4 segment, this may be an interpolation by the

Andreas A poet referring to the original poem itself—a reference that may have been obvious to a contemporary audience familiar with the earlier

Andreas B poem. This passage has no parallels to

Beowulf, as identified by Orchard, but does contain a Cynewulfian compound word and two compounds unique to

Andreas, of which

fyrn-sægen is one example.

11 Downey et al. found a similar practice in effect in the

Guthlac poems.

Guthlac A and

B each contain references to

bec (books) correlating with detectable changes in source (p. 23). Although one may grant that

bec has a stronger implication of “written” sources than

fyrn-sægen, the passage fills the same role as those found in

Guthlac and the signed poems. Furthermore, if the

Andreas A poet saw the

Andreas B poem as divergent from his written Latin sources, then

fyrn-sægen may have been a more accurate description of the source from his point of view.

11. The Distribution of Metrical Dating Criteria within Andreas

If Andreas A and B were composed at different times, then their divisions might also be detectable via aspects of poetic meter that have been correlated with language changes over time. In A History of Old English Meter, R.D. Fulk correlates diachronic changes in Old English morphology, diction, and phonology with the rules of alliterative poetic meter in order to build a chronology of composition for the primary texts in the Old English poetic corpus. He identifies several phenomena, which have value as dating criteria, including the following:

Parasiting—the change of an earlier monosyllabic word to disyllabic through the addition of a vowel;

Contraction—disyllabic words becoming monosyllabic;

Lengthening (or shortening) of diphthongs or vowels;

Adherence to Kaluza’s Law, which pertains to the metrical treatment of vowel quantity of inflexions;

The treatment of ictus—that is, metrical stress—in relation to natural word stress.

Fulk counts passages of interest by noting where inconsistencies in the poems’ scansion can be resolved through application of the above linguistic principles. The occurrences can then be tabulated, and each poem’s score can be compared to the others to generate a relative chronology. Any criterion may hold little weight on its own, but correlation in the reconstructed chronology across criteria builds confidence in the statistical significance of the total collection of criteria observed. Fulk concludes that the metrical evidence divides the poetic corpus into three stages: an early period characterized by Beowulf and Genesis A, a Cynewulfian period including Andreas, and a later Alfredian period. Within the Cynewulfian period, metrical data show some distinctions between Andreas and the signed poems.

Table 7 summarizes Fulk’s metrical data for

Andreas. Each criterion is divided into earlier and later forms

12, and their occurrences are counted for

Andreas A and

B. The occurrence per line score is provided in parentheses.

Andreas has fewer early forms than the period typified by

Beowulf and

Genesis A. Although they are few, all instances of words without parasiting or contraction are found in

Andreas A. One might interpret this as evidence against dating

Andreas B earlier than

Andreas A; however,

Andreas B shows a greater adherence to Kaluza’s Law, which suggests the reverse. It is unclear whether the differences observed in the early criteria between

Andreas A and

B indicate different style or date of composition, or whether they are simply within the bounds of statistical variance.

14 Beyond affirming that both

Andreas A and

B post-date the Beowulfian period, the earlier metrics are inconclusive. The differences between

Andreas A and

B among later forms are similarly disappointing.

Andreas A exhibits a slightly greater preference for contracted forms, whereas

B has more instances of “analogically induced shortening” per line (

Fulk 1992, p. 141).

In sum, the metrical evidence does not show a strong distinction between Andreas A and B, although neither does it contradict the hypothesis that Andreas B was composed first. The metrics of Andreas B are similar to those of Exodus, which is commonly dated to the end of the first period (p. 348).

12. Metrical Dating Criteria in Relation to Cynewulf

Although Andreas B cannot be isolated from Andreas A solely on metrical grounds, its influence might be detected when comparing the metrics of the entirety of Andreas to the signed poems. Taken as a whole, parasited forms suggest to Fulk that “Andreas comes before Cynewulf rather than being contemporary with him” (p. 348). Likewise, contraction shows that Andreas “falls statistically between the earliest poems and Cynewulf” (p. 349). The above interpretations are complicated by the fact that all instances of non-parasited and uncontracted forms occur in the A sections. However, if the Andreas A/B hypothesis stands on other grounds, then these forms may be interpreted as influenced by Andreas B.

A more complicated matter is the treatment of the resolution of words “in which the second of the resolvable syllables is [long]”, such as

sǣcyningas (p. 238). Fulk divides the corpus into three diachronic categories: those in which the syllable is always unresolved (the earliest), those with mixed resolution (including Cynewulf), and those that always resolve (the latest, in which he includes

Andreas). Fulk’s presentation of the data on this point presupposes that

Andreas post-dates Cynewulf. In fact, two of the signed poems—

Christ II and

Juliana—always resolve and of the four signed poems, only

Elene is truly “mixed”. Furthermore, Fulk excludes four instances of

wuldorcyningas in

Andreas as ambiguous

15, making his claim that “the

Andreas poet always follows the latter pattern”—a rare overstatement (

Fulk 1992 p. 237;

2001, p. 8). Scholars are divided on the question of the chronological ordering of the signed poems, but both Ralph Elliott and Patrick Conner consider

Juliana an early poem (

Elliot 2001, p. 298;

Conner 2001, p. 23). So, it is not inconsistent to include

Andreas among the Cynewulfian corpus—including early in that period—despite the absence of non-resolution in this verse type.

In

Meter, Fulk documents a consistent pattern in the deterioration of the observance of metrical rules over time: a period of proper use, followed by occasional violation of the rule, avoidance, and finally ignorance.

Andreas exhibits an “intermediate” character in two more ways when this pattern is applied as an interpretive guide. First, it consistently follows the rule of the coda for the

sǣcyningas verse type discussed above, whereas Cynewulf occasionally violates the rule (

Fulk 1992, p. 239). Likewise, the use of

andswarian in

Andreas violates the rule of the coda while Cynewulf appears to avoid the word altogether (p. 242). In both cases,

Andreas sits between the earlier period and Cynewulfian usage.

To summarize, several metrical criteria point to an interpretation of Andreas as being earlier than the signed poems. The criterion that might suggest that Andreas is later than Cynewulf is also consistent with the interpretation that Andreas is at least contemporaneous with him. It is inconvenient that some of the metrical evidence in favor of an earlier date for Andreas is found in Andreas A rather than Andreas B, which the Andreas A/B hypothesis asserts is the older section. However, it is reasonable to expect remnants of Andreas B to be sprinkled in Andreas A due to the nature of the Andreas A poet’s editorial activities—a possibility discussed above in the context of narrative content.

13. Conclusions

Modern quantitative techniques should not be wielded uncritically or in isolation, but combined with traditional qualitative analysis, they offer a new avenue by which to approach well-known texts. Quantitative data can also serve as an arbiter between incompatible qualitative assessments. Andreas has been interpreted widely by different scholars as an early poem with Beowulf-like characteristics, an unsigned product of Cynewulf, and a post-Cynewulfian homage.

Although it may be possible to explain the evidence of the Andreas A/B division as the product of textual influence from different reference texts on a singular poet, the conclusion that Andreas consists of an earlier core represented by Andreas B, which has been expanded upon, is more parsimonious with the quantitative data. Analysis of oral-formulaic language, word frequency, and orthographic tendencies point toward a new understanding of Andreas as a composite work, which is further supported by a close reading of the text.

Ceteris paribus, this interpretation of the evidence is more coherent than the possible alternatives:

That an earlier poet composed Andreas, and Cynewulf borrowed a striking amount of distinctive formulaic language from him;

That Cynewulf composed Andreas without an early source but used a more archaic style, which he does not deploy in the signed poems;

That a post-Cynewulfian poet used pre-Cynewulfian language and metrics, which are attested nowhere else in post-Cynewulfian poems.

In

Both Style and Substance, Orchard concludes based on Fulk’s analysis that the “notion [..] that

Andreas and the four signed poems are the work of a single poet can be swiftly dismissed” due to “features of both meter and diction that clearly distinguish

Andreas from the four signed poems” (

Orchard 2003, p. 287). In his dismissal, Orchard selects option 3, saying that “the

Andreas-poet is far the more likely borrower [from Cynewulf]” (p. 289). North and Bintley concur, saying the poem is “one of a generation influenced by Cynewulf, whose metre is demonstrably older” (

North and Bintley 2016, p. 58). This conclusion minimizes the fact that the metrical evidence distinguishes

Andreas from the signed poems, because the former is more conservative linguistically. Proponents of a post-Cynewulfian date might attribute these earlier metrical features to borrowing from

Beowulf, but these features tend to be found in

Andreas A, which is not where the bulk of Beowulfian diction resides. It is far simpler to conclude that these features are a result of influence from an earlier source—that of

Andreas B—rather than the peculiar archaisms of a Cynewulf copycat.

Therefore, the textual history of Andreas can be reconstructed tentatively as follows. An early version of the poem still detectable as Andreas B was composed first, probably by a pre-Cynewulf poet. It relied heavily on heroic diction in the tradition of Beowulf and was more concerned with telling a heroic tale than teaching Christian doctrine. That certain features found in Latin sources are not present in Andreas B suggests that this poem represents an earlier form of the story or at least one with a particularly Anglo-Saxon flavor. In addition to the B sections, it likely included much of the introduction and fitt iv, especially lines 359–76. Remnants may also survive in section A4 and the ending passage.

Taking this poem as a foundation, the Andreas A poet expanded the Andreas B poem with the material identified above as Andreas A, including overtly didactic, moralizing episodes, such as the divine helmsman, the discursive stories of skeptical unbelievers, and Andrew’s imitatio Christi. Harmonizing the Andreas B poem with a known Latin source may have been a primary motivation for the Andreas A revisions. Section B3 and the ending passage appear to have been more heavily edited by the Andreas A poet than the first half of Andreas B. However, a favorite stylistic tic of the Andreas A poet was coining novel compound words, which he used throughout the B sections, even in areas where he preferred to retain Beowulfian phraseology. The Andreas A poet exhibits striking affinity with the signed poems, which suggests that he was either Cynewulf himself or someone very well acquainted with his work.

For Andreas B, much work remains to explore how it fits into the history of Old English poetry, who the author may have been, where and when it may have been written, and what new information it may provide us when considered as a newly re-discovered poem in its own right. In the case of Andreas A, the question of Cynewulfian authorship needs to be re-evaluated in light of the implications of the Andreas A/B division on the style of the Andreas A poet, both as the author of the A sections and as an editor of the B material.

Early critics of Old English poetry, and the Cynewulfian group in particular, were characterized by an eagerness to ascribe all manner of unsigned poems to a few known poets, such as Cædmon and Cynewulf. As later scholars adopted more conservative interpretations, the pendulum of scholarly consensus swung toward a minimal Cynewulfian canon. Quantitative analysis offers us a way to temper the swings and circumscribe the bounds wherein subjective interpretation applies. The composite nature of Andreas as identified above must be seen as one small nudge of the pendulum toward a more inclusive interpretation of Cynewulfian authorship.