This article aims to define the role the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana played in the process of dismantling the dominant bilateral split of cultural power between the so-called Superpowers. Following the methodology provided by Anthony Gardner and Charles Green, it considers the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana as one of the so-called biennials of the south, which sprung to life between the mid-1950s and the 1980s (

Gardner and Green 2013, p. 444). These biennials emphasised regionalism and attempted to bring the local artistic endeavours to international attention to redefine cultural networks across geopolitical divides. This so-called second wave of biennialisation dismantled the existing artistic focal points located in the northern hemisphere, mostly in the US and the USSR. Events such as the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, the Biennale de la Méditerranée in Cairo and the Biennale of Arab Arts in Baghdad offered a third way for the existing power split, shifting the balance in international cultural relations towards the southern hemisphere. The Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, therefore, closely followed the political strivings of the socialist Yugoslavia towards creating an alternative to the bilateral Cold War reality. This article explores the curatorial strategies devised by the organisers of Ljubljana’s biennial to mediate between the expectations of promoting socialist ideology demanded by the hegemonic state authorities and the aspiration to modernise and westernise the local art scene, in particular to support the members of the Ljubljana Graphic Art School, which emerged along with the development of the Biennial (

Teržan 2010, pp. 30–31). It focuses on curatorial strategies developed by Zoran Kržišnik for this exhibition and demonstrates how the printmakers and curators took advantage of the power they had gained from the authorities to comment on the political situation and, at the same time, to develop an international network of printmaking exhibitions for their own benefit. It therefore highlights the emergence of an alternative cultural space, which was built upon the international circulation of prints. This article uses the existing up to date research, mostly collected in jubilee publications and catalogues accompanying the Biennial, as well as the archival photographs and documents collected in the archives of the International Centre of Graphic Arts and Moderna galerija in Ljubljana.

By the early 17th century soft ground was the prevailing technique used by etchers. This method used an application of an acid resistant coating made of bitumen, resin, beeswax, and tallow onto a metal plate. The tallow moisturises the ground, making it waxy and malleable, allowing the artist to draw a line like the one produced with a pencil or crayon. This effect is often altered by the structure of the paper, which tends to produce granular broken lines, especially when the plate is covered with a fine- or coarse-grained sandpaper. The artist renders an image on the paper with a hard pencil, which makes the paper stick to the greasy ground. When the paper is removed, the varnish sticks to it and pulls off, leaving the lines on the plate that are then bitten into by the etching solution (

Leaf 1974, pp. 81–82). A small revolution came when Jacques Callot (1592–1635), a printmaker from Nancy in Lorraine, invented a harder recipe for the etching ground (

Platzker and Wyckoff 2000, p. 21). The use of a soft ground did not offer the possibility to produce hard-etched lines, making the drawings always appear blurry. Callot decided to progress from the soft ground and used lute-makers’ varnish rather than a wax-based formula, which helped the etched lines to be more deeply bitten. This invention allowed etchers to produce highly detailed work that was previously the monopoly of engravers.

Three-hundred years later, printmakers again developed a need to find a method that would allow them to produce much ‘sharper’ images. This time, progress was not made by means of technical solutions, but rather, in the field of cultural politics. The Cold War divided the world by the Iron Curtain and made it problematic for printmakers to communicate internationally.

1 Behind the Iron Curtain, cultural exchange was often channelled and scrutinised by state authorities; however, the level of oppression was not homogenous and varied from one country to another. Despite the political differences, cultural isolation was a common characteristic that mobilised artists working in countries ruled by authoritarian powers to self-organise in a shared effort to overturn the dominant power divide between East and West. The opportunity to negotiate this power split emerged neither on the western nor on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, but rather southwards from the transatlantic split. Yugoslavia in 1948 broke off from the USSR and departed from the Eastern Bloc in the event known as the Tito-Stalin split (

Perović 2007, p. 40).

2The Biennial was meant therefore to culturally mediate between the West and East and mark Yugoslavia on the map of international cultural affairs. Yugoslav printmakers and curators of the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana became an avant-garde of the cultural process that aimed to overturn the Cold War bilateral split. Metaphorically speaking, The Biennial in Ljubljana offered to printmakers an opportunity to etch into the hard political coating and bite at the Iron Curtain. Importantly, this process was not carried out with aggressive solutions, such as open protest actions, but rather with the help of softer cultural diplomacy. Significantly, this biting action of the Iron Curtain was in large part facilitated thanks to the selection of graphic art as the medium that was shown during the exhibition. The Iron Curtain was slowly corroded by the curators who managed to establish a periodic exhibition of graphic art in Ljubljana and the printmakers who submitted their prints to the competition.

This penetration of the Iron Curtain started in 1955, when a dialogue between strict diplomatic policies and efforts towards artistic emancipation gave birth to the Biennial of Graphic Arts, which was founded in Ljubljana in the former Yugoslavia. It was the first large-scale curatorial initiative in that country with the aim to link printmakers working behind the Iron Curtain with their Western counterparts and help them to make their mark on the emerging global art map (

Grafenauer 2014, p. 28). It was also one of the first such initiatives in the entire region. The Biennial of Graphic Arts offered an unparalleled opportunity for artists such as Bogdan Borčić, Andrzej Lachowicz, Mauricio Leib Lasansky, Adolfo Quinteros and Aleš Veselý to exhibit their works along with the key protagonists of the Western contemporary graphic art circuit such as Robert Rauschenberg, Antonio Segui, Yozo Hamaguchi, Max Bill, and Frank Stella. The Biennial of Graphic Arts became a major success and its model quickly spread across the world, inspiring curators to set up similar exhibitions in several locations across Eastern Europe (

Grafenauer 2014, p. 25). The network of dedicated international exhibitions of graphic art, which drew inspiration from the model established in Ljubljana, became a window into the world not only for printmakers, but also for artists who were affected by censorship or otherwise marginalised in their country of origin, making the Biennial of Graphic Arts a cultural cornerstone for the Non-Aligned geopolitical order.

3 The expansion of graphic art exhibitions that followed the example set by the Ljubljana’s Graphic Art Biennial and the emergence of a global space for circulation of artistic concepts epitomised what Edward Soja called in 1996 the ‘third space’ (

Soja 1996, p. 260). The notion is derived from the Foucauldian concept of heterotopy, and it proposes an alternative way of thinking about space as a spatial and social construct (

Foucault 1984, pp. 46–49). Third spaces are the in-between, or hybrid spaces, where the first and second spaces interact to generate a new third space. In the case of the Biennial, the hybridity of the space was derived from the apparent conflict of the official and the non-vocal interests. The political game between the official and the non-official interests that balanced Cold War international cultural relations created a third space for more independent artistic and curatorial expression.

Considering the modest beginnings of the Biennial, it is surprising how extensive this periodic exhibition became and how much significance it gained over the course of time. While the first exhibition in 1955 attracted 146 printmakers, the exhibition of 1969 had to exclude a number of prints due to a lack of exhibiting space (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 9,

Figure 1). The Biennial kept growing and in the early 1960s reached its peak of development. Its artistic, but also political significance, grew over time so much that the 11th edition of 1975 received the official patronage of Josip Broz Tito (

Grafenauer 2014, p. 25). Such rapid growth was possible thanks to a peculiar symbiosis between political and artistic interests, but more importantly because of the skilful cultural management. The Biennial with its program oriented primarily towards promoting arts rather than politics quickly became an event with a hidden curatorial agenda. A closer investigation of these curatorial assumptions and the conditions that forged the curatorial agenda casts light on the role the post-war large-scale art exhibitions played in the process of spreading soft power patterns of communication, so crucial for the international political contacts, which were torn apart by the World War II.

The shape the Biennial took in the early years of its existence was related to the international plans of Josip Broz Tito, who planned to improve the image of Yugoslavia on the international arena by means of cultural policies. In the early 1950s, Tito was travelling around the world in pursuit of friendly relations with as many countries as possible to strengthen his position within the future Non-Aligned Movement, and to strengthen Yugoslavia’s position vis-à-vis the so-called Superpowers.

4 The Non-Aligned aspirations were the main political driving force that brought the Biennial to life. Although the Non-Aligned Movement was set up in 1961 at a conference in Belgrade, the Yugoslav efforts to organise a platform of cooperation for the Third World countries can be tracked back to December 1954 when Tito travelled around Asia to build a coalition of heads of Asian states (

Willetts 1978, p. 10).

What characterised the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), was its potential to eschew the hard power politics of the Cold War (

Mukherjee 2014, p. 52). Whilst the Great Powers established their world domination through amassing military and economic power, NAM did not contribute to the arms race and did not directly oppose the hegemonic powers of the US and the USSR instead proposing multilateralism as an alternative to bilateralism (

Kullaa 2015, pp. 33–34). Josip Broz Tito, the President of Yugoslavia and one of the founding fathers of NAM, described non-alignment not as a ‘southern policy’ or a ‘dual policy’, but as a ‘world policy’ that belonged to ‘the universal interests of the world’ (

Stavrou 1985, pp. 38–39). NAM’s approach towards international policymaking can be synthesised by reiterating its three basic pillars: the right of independent judgement; the struggle against imperialism and neo-colonialism; and the use of moderation in relations with all large powers (

Mišković 2014, p. 7). The retreat from the confrontational path in foreign policy-making exhorted NAM to seek alternative methods for pursuing foreign policy that could create an opportunity for participating countries to enter the international discourse on par with the Bloc Countries.

One of the strategies undertaken by NAM was to promote the idea of the non-violent coexistence of states as an expansion in the field of cultural diplomacy, which resembles soft power method (

Farah 1982, pp. 34–35). Although the term ‘soft power’ emerged much later than the founding of NAM, and may appear to be an anachronist notion, its character and main properties resemble the nature of the cultural policy forged in the early years of NAM’s existence. The term was coined by Joseph Nye in the late 1980s, who defined this type of power as the ability of a country to persuade others to do what it wants without force or coercion (

Nye 1990, pp. 167–68). Soft power stands for the ability to shape the preferences of others, through appeal and attraction (

Nye 1990, pp. 11–12). Additionally, it stands in opposition to the hard or command power that forces one party to follow the orders of the other (

Nye 1990, pp. 25–26). Often called the ‘second face of power’, soft power acts indirectly through production of attraction aimed at acquiescence (

Nye 2011, p. 82). Nye pointed out that seduction is ‘always more effective than coercion, and many values like democracy, human rights, and individual opportunities are deeply seductive’ (

Nye 2011, p. 88).

It is rather complex to place the concept of soft power within one political context. As Yasushi Watanabe and David McConnell argue in their book titled

Soft Power Superpowers the confusion over soft power ‘stems from misunderstanding, impressions, distortion, misuse, or in extreme cases, abuse of the concept.’ (

Watanabe and McConnell 2008, p. XVII). A similar degree of confusion exists in regard to the complexity of power relationships towards resources used in constructing soft power policies. According to Craig Hayden, soft power strategies are converted into power as represented in specific policy outcomes, which can be observed in the eliciting behaviour of the opponent (

Hayden 2011, p. 42). Janice Bially Mattern remarked: ‘for actors who aim to deploy soft power, successes will ultimately depend on knowing how exactly to make their ideas and themselves attractive to a target population.’ (

Mattern 2005, p. 584). In the case of the Ljubljana’s Graphic Arts Biennial, it is somewhat difficult to measure how far the cultural policy behind the Biennial helped to achieve the desired effect and what exactly this intended effect was. The authorities never officially expressed what tasks the Biennial should achieve. However, the large number of participants from across the world, as well as the impact this exhibition had on the formation of a network of graphic art exhibitions and the number of countries participating in the Biennial, makes the use of the term ‘soft power’ partially justifiable, as the Biennial in large part managed to promote a positive image of socialist Yugoslavia.

From the early stages of its existence, NAM was devised as a political theatre aimed at wielding soft power through accentuating the movement’s positive public image (

Shimazu 2016, pp. 59–58). In particular, large conferences and symposia served as effective seductive apparatuses for exercising softer patterns of power. The Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana was designed according to similar political foundations, as, for example, the 1955 conference in Bandung, which laid the theoretical foundations for the establishment of NAM. The Bandung Conference, which was the first post-war large-scale Afro–Asian Conference, can itself be compared to a symbolic theatrical performance, where heads of state meticulously performed their stage roles in front of the audience, which was granted the public maximum possible access to the politicians and events on the agenda (

Shimazu 2016, p. 65). The subsequent summit that took place in Belgrade (1–6 September 1961), and which finalised the efforts towards setting up the NAM, had to restrain the performance element due to security measures introduced to protect politicians from potential threats (

Shimazu 2011, p. 12).

Even though these large conferences succeeded in promoting their ideology amongst the NAM’s participatory states, they did not attract large numbers of participants from the Bloc Countries, and therefore did not provide the non-aligned ideology with sufficient exposure to the international community at large (

Arnold 2010, p. 38). Cultural events, such as Ljubljana’s Biennial of Graphic Arts, were meant to become much more efficient tools for the external promotion of the ideology of non-alignment. The most important characteristic of the venture such as the Biennial was that it could potentially become a meeting place with an international and inclusive scope, allowing it to bring to one table participants from the NAM’s member states, the Soviet Union, and its satellite states, and also participants from Western countries. Amongst the plethora of cultural events inspired by the policy of non-alignment, the Ljubljana Graphic Art Biennial serves as a flagship example.

The Ljubljana Graphic Art Biennial, in a similar way to the Egyptian Biennale de la Mediterranée that came to life in Alexandria also in 1955, was fuelled by the search for a soft power strategy that could place a peripheral country on the map of international relations (

Teržan 2010, pp. 18–19). These cultural events supported a shift in Cold War cultural policy-making and aimed to redefine the cultural relations that were first broken by the World War II and then further disturbed by the hostile competition between the Superpowers (

Gardner and Green 2016, p. 50). It was founded in large part by the efforts of the Slovene curator Zoran Kržišnik (1920–2008), who in 1947 became the first administrator of the Moderna galerija in Ljubljana (The Museum of Modern Art) and later in 1957 became its director. He held this position for nearly forty years, until 1986, after which he became a doyen of the Yugoslav cultural scene (

Žerovc 2008, p. 36). Kržišnik saw the Biennial as a possibility for a projection of values such as the presence of freedom, modernity, democracy, openness in society. He pointed out in one of his interviews that he demonstrated to President Tito that the Biennial could become a materialisation of openness and non-alignment (

Žerovc 2008, pp. 46–47,

Figure 2). Tito publicly praised the Biennial by saying: ‘It is marvellous that we have this gathering of artists from all over the world. New currents are being established, though I don’t completely understand them. I feel closer to the kind of thing Jakac paints.’

5 Kržišnik was well-aware of how to dominate the political as well as cultural circles in Ljubljana. His intention to set up an international graphic art exhibition stood therefore at the forefront of a major shift in Yugoslav cultural policymaking, which had been heralded by a series of progressive art exhibitions staged at Ljubljana’s Moderna galerija in the early 1950s.

The Moderna galerija was an optimal place for organising the Biennial. It was founded in late 1947 by a decree of the government of the People’s Republic of Slovenia as a result of thorough consideration of the needs of a contemporary art museum at the time. During the socialist times, the Moderna galerija did not entirely follow a Western paradigm of a museum of modern art, although it offered similar exhibiting possibilities. The new museum building was designed in the 1930s by Edvard Ravnikar, who designed a formally neutral building in which exhibition spaces were hierarchically equal and located around the central hall. Such a layout provided a convenient space for presenting large quantities of works, without setting apart any of the prints. Until the collapse of the former Yugoslavia, the Moderna galerija focused its efforts on collecting Slovenian art, which was also reflected by the exhibition policy directed primarily at presenting Slovenian artworks (

Jagodzińska 2015). The most prominent exception, however, was the International Biennial of Graphic Arts. What is significant in the context of choosing a space for establishing the Biennial, the Moderna galerija followed the canons of Modernism in terms of the architectural layout and the modes of presentation of art and it also used them as a means for evading ideological pressure (

Zabel 2012b, pp. 149–50). Interestingly, it was the formalism of Modernism with its apparent neutrality and lack of interest in current social problems that ultimately best suited the then authorities. In the early 1950s, Yugoslavia was still governed by ideological dogmatism, which favoured conservative figuration over abstract art (

Koščević 1955). The first permanent exhibition at the Moderna galerija opened in 1951 and presented Slovenian art from Impressionism until 1950. A year earlier, the Moderna galerija presented a temporary exhibition showcasing Slovene Impressionism, which is often considered as an important victory over extreme ideological dogma (

Zabel 2012a, pp. 63–64). It was followed by another temporary exhibition of works by Slovene Riko Debenjak and Stane Kregar in 1953, which opened up the question of Abstract art in Yugoslavia (

Zabel 2012a, pp. 63–64). In 1955, an important Henry Moore exhibition took place, which gave a powerful stimulus to Modernist tendencies in Yugoslavia and which was an important step towards bringing the Biennial to life (

Koščević 1955).

A project of a larger scale than the monographic exhibitions, that necessitated convincing the socialist authorities of the potential of Kržišnik’s avant-garde Biennial, in itself proved to be a difficult project. In the early 1950s, after the Third Plenum of the Communist Party in December of 1949, convincing the political establishment was much easier to achieve (

Rajak 2010, pp. 28–29). The plenum made a public departure from Stalinist ideology and sanctioned a completely different approach to socialist education and culture (

Rajak 2010, pp. 28–29). It endorsed and encouraged free exchange of ideas and acknowledged that Yugoslavia, as an intellectually and culturally underdeveloped country, should turn towards the outside world. The plenum proposed that, as a prerequisite for its cultural progress, the country should expose its intellectual potential to the scrutiny and influence of the outside world and compete with it (

Rajak 2010, pp. 28–29). Even though the moment was politically favourable, proposing a new cultural venture in Yugoslavia at that time still required strong negotiation skills. More importantly, it needed profound awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of Tito’s circles of power. What made this task even more difficult was the fact that establishing a new periodic art exhibition was not a common practice between 1945 and 1955, especially an exhibition that would promote openness and admiration of the newest Western artistic developments. Such an approach did not fully correspond with the ideology of self-management, which emphasised the independence and superiority of Yugoslav cultural developments over admiration directed towards foreign cultures (

Jakopovich 2010, p. 61).

In order to establish the Biennial, Kržišnik had to find a strategy to approach the upper echelons of Tito’s administration responsible for the Yugoslav cultural policy. The dominant attitude towards modern art among the political establishment of that time is described in a speech delivered by President Tito on 23 January 1963 during the 7th Congress of the People’s Youth Organization of Yugoslavia that took place in Belgrade:

I am not against the artistic search for the new, for example, in painting, sculpting and other fields of art, because that is needed and good. But I am against giving the community’s money to some so-called modernist works that have nothing to do with artistic creativity let alone our reality. (…) Who is responsible that such quasi-art has become so prevalent? Naturally, those who buy this quasi-art and spent state’s money on it, sometimes even giving awards and such. If someone wants to engage in such painting or sculpting, let them do that at their own expense, together with those who represent the ultramodern, abstract art. Could it be that our reality does not offer a material that is rich enough for creative artistic work? And the large part of our young artists dedicates the least attention to it… It is clear that here we cannot speak of some sort of administrative intervention. Nevertheless, the public should not be passive about such problems.

Kržišnik developed thorough knowledge of internal alliances and tensions to neutralise the reluctance towards modern art, in particular abstract art. To convince politicians sceptical about modern art that the Biennial deserved their support, he went so far as to host the Yugoslav vice-president and minister of culture in Ljubljana and even took them to Paris and Venice (

Žerovc 2008, p. 46). In one of his last interviews, Kržišnik recalled:

Thankfully, Krste Crvenkovski came to Ljubljana upon Tito’s order, an open-minded, literary man and a Slavic studies specialist, while also the vice-president of the Yugoslav government and minister for culture. After seeing the biennial, he supported us and after that things began to run their course fairly smoothly. In order to convince him even further, I accompanied him to Paris and Venice. It was a funny situation. He never said where he was going and they were looking for him all over Ljubljana. In short, I think that at least the basic origins of what is now termed curatorship were already established then.

On top of these obstacles, Zoran Kržišnik planned to use graphic art to promote Yugoslav culture, which was not a widely appreciated artistic medium at the time (

Wye 1996, p. 11). While Yugoslavia had a strong sentiment for prints, especially partisan linocuts produced during World War II, in the early 1950s graphic art still did not get as much attention as it was about to get in the 1960s, neither in the countries behind the Iron Curtain nor on a larger, global scale (

Wye 2004, p. 23). In the 1950s, prints were often disregarded because they could be easily multiplied in large quantities and their production was cheap (

Teržan 2010, p. 19). The boom for graphic art, especially using unconventional techniques, and the internationalisation of the graphic art scene came about in the 1960s and 1970s along with the crisis of traditional media, but in the mid-1950s, printmakers still operated in small closed circles of reciprocal or generational influence, often exhibiting mostly in a local context, while maintaining a close association with a local academy of fine art (

Wye 2004, p. 22).

Exhibitions dedicated only to graphic art with a global outreach were therefore not a frequent phenomenon, making it difficult for Kržišnik to attract participants from abroad. From dozens of such cultural ventures organised in different parts of the world, only a few could boast of international character. For example, biennials, such as Bianco e Nero founded in 1950 in Lugano or the Biennial of Colour Lithograph established in the same year in Cincinnati, won high esteem among printmakers and regularly attracted the most prominent graphic artists from around the world, but rarely for printmakers from behind the Iron Curtain (

Cochran 1989, p. 8). It can be argued that the graphic art sections at the biggest periodic exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale were important melting pots for graphic art trends, but the mid-1950s saw only a small number of such large-scale exhibitions taking place. An optimal opportunity for expanding the network of contacts were professional printmakers’ associations, such as the International Society of Wood Engravers XYLON, which was founded on 26 September 1953 in Zurich and which from 1957 onwards held its own periodic exhibition of woodcuts (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 7).

Kržišnik therefore had to rely on his personal contacts but also on the vast network of local affiliations. The idea to initiate a biennial in Ljubljana was originally conceived by Božidar Jakac, a Slovene printmaker and former Partisan artist, who proposed to Kržišnik the organisation of a review of world graphic arts in Ljubljana after visiting the Mostra Internazionale di Bianco e Nero in Lugano (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 7). The key opportunity for expanding his network came in 1952 when Kržišnik acted as the assistant to the cultural commissar Šegedin at the Venice Biennial. There, he met Zoran Mušič, a Slovenian artist, who between 1950 and 1951 received many awards including a special prize from the Biennale in Venice (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 8). These successes brought Mušič a contract with the Galerie de France, signed in 1952, which also granted him a rare opportunity to live and work in Paris, although he kept his studio in Venice (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 8). Kržišnik went to Paris for consultations with artists where he collected 144 graphic works, practically the entire collection of the École de Paris, and brought them to Ljubljana (

Škrjanec 1993, p. 8). These works became the foundation of the Biennial. Subsequently, various curators came to Ljubljana to visit the Biennial, among them Gustave von Groschwitz, the director of the Biennial of Color Lithography in Cincinnati, and Arnold Bode, the organiser of

documenta in Kassel. Kržišnik dominated the political game and learned how to use these cultural obstacles to his advantage. His concept for a periodic exhibition was based on the conviction that graphic art can appear to correspond with socialist ideology, and at the same time herald progress in the field of arts (

Žerovc 2008, p. 39).

Kržišnik’s pursuit to establish an international print exhibition in Yugoslavia could be considered an innovative, but rather preposterous, concept. From a local perspective, it certainly appeared to be an extravagant plan, but Kržišnik knew how to manage the risks, mostly thanks to of his international contacts. His aspiration to bring the Ljubljana Biennial to life was also supported by his strong personal motivation and belief in the potential of such a venture. In one of his last interviews he gave before his death in 2008, when asked about the role of the curators in negotiating the cultural change in Yugoslavia, he recollected that:

It was us who were using politics through persuasion, not the other way around. (…) I managed to convince a few people in politics that this was their future. I proved to these people that we could be a source of liberalisation, which is not brutal in the sense of socially tense situations, but that fine art can be an instrument of a slight liberal opening. That’s how it was. You know, through establishing ourselves in art, the world wrote about us favourably, proclaiming that we were an open society.

Such confidence was supported by several years of experience working on smaller curatorial projects at the Moderna galerija in Ljubljana. This work encompassed engagement with local artists but, most of all, was focused on learning the rules that governed socialist Yugoslavia. His labour at the grassroots of artistic circles and a vast portfolio of personal contacts spanning the world of politics resulted in the legitimisation of Kržišnik’s decisions and allowed him to successfully execute his avant-garde Biennial.

Even though in 1955 Yugoslavia was an authoritarian country, the organisers of the Biennial managed to win a significant degree of freedom from the authorities. The curators could invite any artist who in their opinion produced graphic art of the highest quality and could design the layout of the exhibition according to their will, providing that their ideas did not openly interfere with the political line of the authorities (

Grafenauer 2014, pp. 19–20). Initially, invitations were sent through the Yugoslav artists’ union, but many were passed by the organisers directly to the artists. Additionally, some countries received special invitations to present whatever they wanted without interference (

Teržan 2010, pp. 21–22). This was possible due to the policy of self-censorship extended by the Yugoslav cultural authorities. Since the Tito-Soviet split in 1952, Yugoslavia did not support overt censorship and preferred to rely on the work of politically responsible editors who were tasked to ensure artistic endeavours complied with the officially approved political narration (

Green and Karolides 2014, pp. 662–63). Self-censorship was in place, which was most visible in the selection of the Biennial’s curators, who in fact acted as censors, making the Biennial free from political controversy. Only the works selected by an international jury were presented at the Moderna galerija, with the aim to exhibit the most notable representatives of current trends in international printmaking. It also aimed to provide an opportunity for artists from the Third World to exhibit their works, many of whom had international reputations, to enter the competition on par with artists from Western countries.

Even though the event had a strong political undercurrent and was influenced by the third world, the actual content of the exhibition was more oriented towards promoting arts rather than politics. If we look closer at the visual evidence gathered in the catalogues of Ljubljana’s graphic exhibitions, we might be surprised by the scarcity of works that make a direct reference to NAM’s policies. The majority of the works seemed to be selected due to their technical, or broadly speaking, artistic quality, rather than due to their political significance. In fact, neither Tito nor the upper echelons of the Party’s establishment responsible for cultural affairs seemed to be interested in the actual content of the exhibition. The entries one will find in the catalogues of the show very rarely directly refer to non-aligned discourse. Here, it is worth mentioning some apparent exceptions such as Pavel Nesleha’s

History of a Hand in 1970, which seems to make a reference to John Heartfield’s 1930s anti-fascist

Hand has Five Fingers, with Five Fingers we can Grasp the Enemy. In Nesleha’s version the worker’s ageing hand has been cut from its life blood and appears to be in the process of withering, alluding to the Czechoslovak disillusionment with Communism.

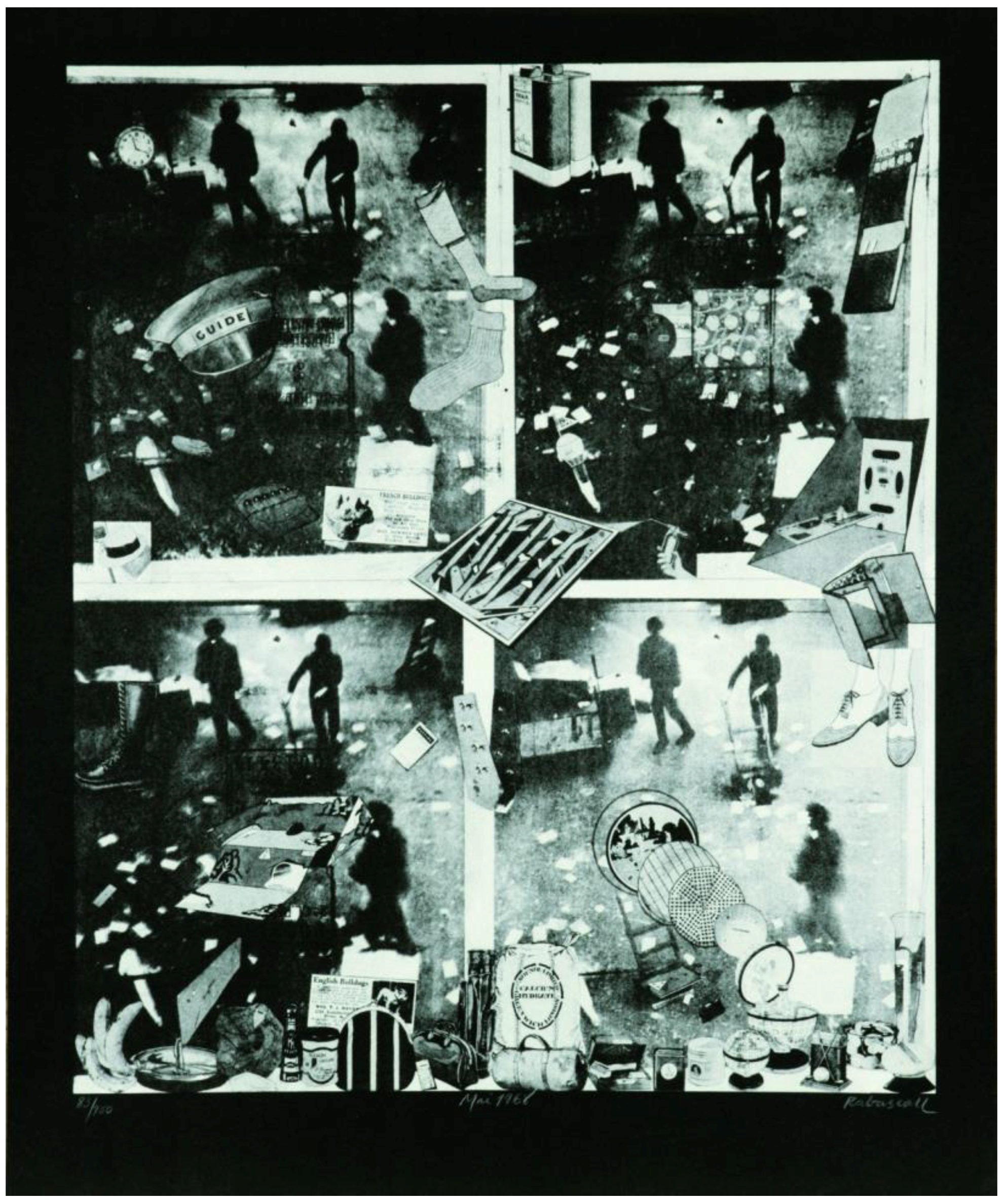

Moratorium II, 1970 by the Puerto Rican, Carlos Irizarry, refers to the protracted US engagement in Vietnam, drawing inspiration from a piece by Jasper Johns and Picasso’s Guernica. Joan Rabascall, from Spain, contributed the lithograph

May 1968, which depicts student protests in Paris (

Figure 3). The lithograph was combined with an offset technique, which rejects the status of the work of art as merchandise. Students protested against the illusion of freedom produced by culture and Joan Rabascall took part in this political agitation (

Cirici 2009, pp. 90–91). There is also Aleksander Sitnikov’s lithograph,

Women of the World, Keep the Peace on Planet Earth! 1974, a propaganda piece referring to the USSR as the world-guarantor of peace.

Kržišnik took full advantage of the quiescence of the authorities and designed the biennial to appear as an international meeting space aimed at bringing to Ljubljana the best representatives of current trends in printmaking, rather than turning it into a mere festival of non-aligned propaganda. Unofficially, therefore, the Biennial was organised to introduce abstraction to the Yugoslav art world (

Jemec 2010, pp. 186–87). At the same time, the Biennial was used to promote the local artistic scene and build its connections with the global art world. The Biennial became an opportunity for artists from the Third World to enter the competition on par with artists from Bloc countries, who in many cases were widely recognised artists. The effect of inclusivity was reinforced by inputs from the most competent jurists possible, which included directors of museums such as the Guggenheim, the Tate, and curators such as Pierre Restany, Harald Szeemann, William Lieberman and Jorge Glusberg (

Škrjanec 1993, pp. 120–21). Introducing a competition format to the Biennial was particularly important not only because an open call could potentially attract more artists, but also because a competition based on artistic merit could turn the public attention away from hard-edged politics.

Another important factor behind the decision to build the Biennial around graphic art was the fact that many leading artists, apart from specialising in one artistic medium, often experimented with printmaking. This is in particular the case when artists educated at Fine Arts Academies are considered, where printmaking is part of the curriculum. This fact gave the Biennial a projection on the entire international artistic scene, since many painters and sculptors also produced prints. The strategy focused on tightening the Yugoslav art dimension with the Western world, rather than concentrating on promoting art from Third World countries, is best reflected in the selections made by the panel boards, who awarded the grand prizes of the first editions of the Biennial mostly to North American, Western European and Japanese artists. For example, in 1955, Armin Landeck was awarded the Grand Prize for his cityscapes. In 1957, France’s Henri Georges Adam received the prize for his tapestry-inspired etchings. The 1959 prize went to Pierre Soulages for his scumbling, moody stains. In 1961, the prize was awarded to Japanese Yozo Hamaguchi for his synthetic still-life, executed in mezzotint rather than in the traditional Japanese woodcut, in 1963 to Robert Rauschenberg and in 1965 to

Joan Miró. What is significant is that artists from the United States won the highest award nine times, French artists received the highest recognition three times, Japanese artists were awarded the Grand Prize five times, and Eastern European artists received the highest accolade only four times (

Zrinski 2010, p. 208).

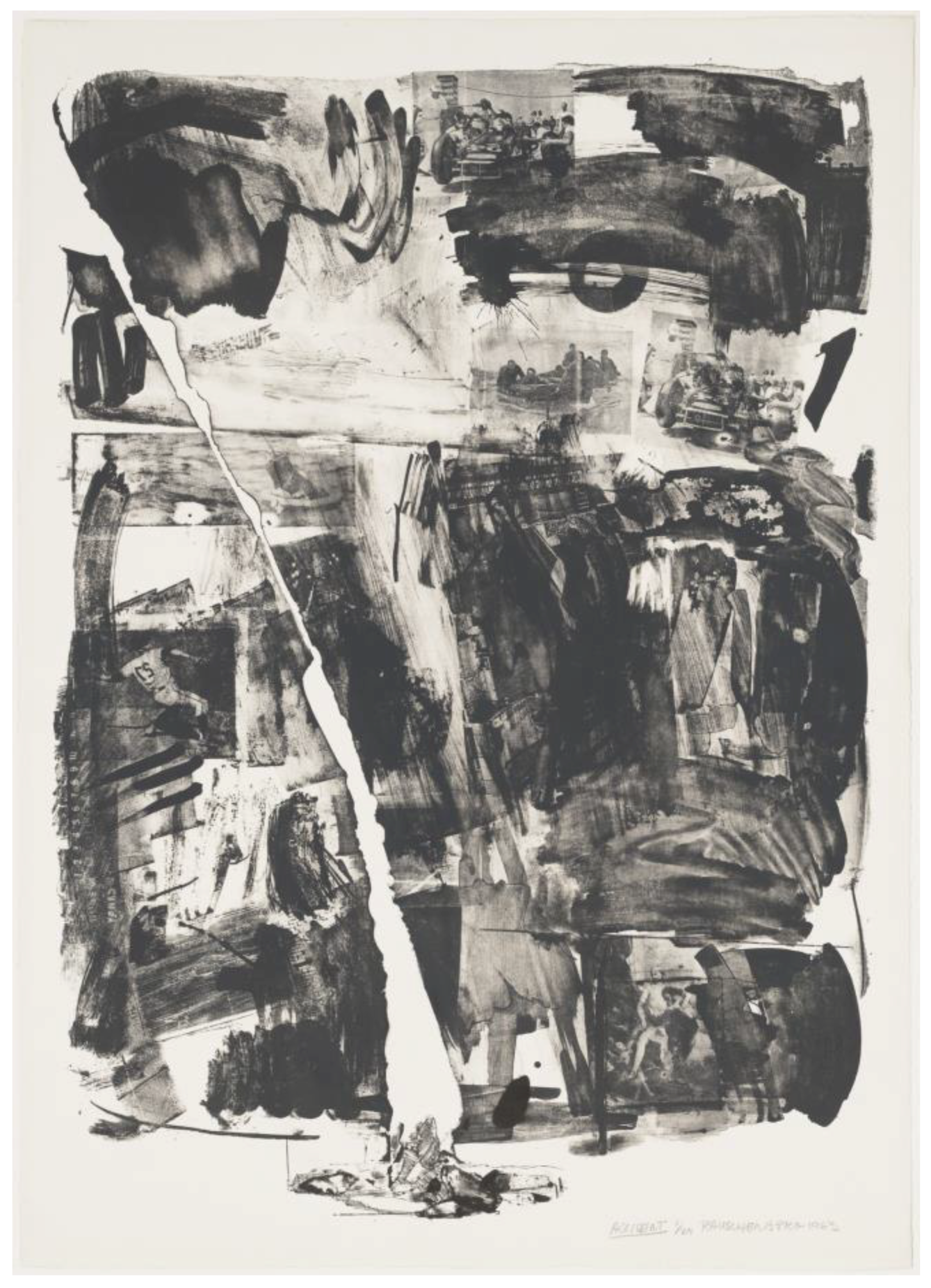

Sending prints allowed artists coming from the West to engage with the artistic reality behind the Iron Curtain, but more importantly placed Eastern European artists alongside the most recent printmaking developments. The most notable example of such an exchange was Robert Rauschenberg’s lithograph titled

Accident, winning the Grand Prix during Ljubljana’s Fifth International Exhibition of Graphic Arts in 1963 (

Teržan 2010, p. 23,

Figure 4). The lithographic stone for

Accident broke in two whilst Rauschenberg was working on it (

Castleman 1973, p. 122). He then tried another stone and when it also broke, he decided to retain the diagonal white gash through the composition, recording this event and metaphorically linking art with the unpredictability of everyday life (

Castleman 1973, p. 122). The first prize at the, by then, prestigious Biennial brought Rauschenberg and American printmaking to the attention of the European art critique. It was an important event in Rauschenberg’s career, as his success in Ljubljana had come a year before he was famously awarded the Grand Prize at the Venice Biennial; the event that later opened the doors to international fame for him (

Brooks 1991, p. 174). Thus, Ljubljana was linked to the most recent and important events in the art world and connected the Balkan region to the international art world (

Castleman 1973, p. 165).

The most profound impact of the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana was not the cultural and political emancipation of the several generations of printmakers these exhibitions empowered, it was the resulting onslaught on the Iron Curtain. Through the Ljubljana’s Biennial of Graphic Arts, the NAM ideology was supposed to have an indirect influence not only on the European but also Latin American printmakers and their struggles against the cultural policies of the authoritarian states. In this respect, it is worth mentioning exhibitions such as the San Juan Biennial of Latin American Graphic Art founded in 1970 in Puerto Rico and the Graphic Arts Biennial in Cali, Colombia established in 1971. The success of the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana also resulted in a rapid proliferation of periodic graphic art exhibitions, not only in countries suffering from authoritarian rule but on a much larger, global scale (

Gardner and Green 2016, p. 87). Similar cultural ventures were established in Tokyo (1957), Grenchen (1958), Krakow (1966), Florence (1968), Bradford (1970), Fredrikstad (1972), as well as Santiago de Chile, Zagreb, Bitola, Belgrade, Tallinn, Riga, Cairo, Bucharest and Sofia (

Teržan 2010, p. 29). The inspiration to follow the format of the exhibition established in Ljubljana came through establishing personal contacts with the organisers such as Zoran Kržišnik who, for example, maintained contacts with the director of the National Museum in Tokyo, and Walther Koschatzky, the director of Albertina, who planned to establish a similar periodic exhibition in Vienna (

Žerovc 2010, p. 44). Additionally, by the mid-1960s, Ljubljana was already an event with a well-established reputation among printmakers across the world. This fact was reflected in the way Ljubljana acted as a platform, which played a key opinion-making role for establishing a canon of contemporary graphic art. Artists whose works were exhibited in Ljubljana also received recognition at other periodic exhibitions of graphic art.

In fact, the policies of non-alignment were only a background for the curatorial effort of the organisers to elevate graphic art and make Ljubljana the world’s capital of printmaking. During the Cold War, artistic print culture had, therefore, a significant input in the process of re-building cultural networks broken by censorship and authoritarian governments. Repressive measures had often been introduced in the aftermath of events, such as the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the student and intellectual protest action in the Polish People’s Republic in March 1968. In this respect, it is important to underline that the biggest tragedy of censorship was not the atmosphere of schizophrenia created by constant surveillance, or even the breach of the freedom of expression, but the destruction of the internal cultural fabric caused by disseminating distrust and alienation amongst artists (

Gömöri 1986, p. 506). Censorship forced artists to work in closed circles of reciprocal artistic influence, while access to the international art world was rationed to only to those in good grace with the state. Cultural isolation resulted in a common artistic aspiration to westernise and modernise art produced behind the curtain of censorship, and Ljubljana’s Graphic Arts Biennial gave such a chance to a several generations of Yugoslav artists. For example, Janez Bernik, one of the members of the unofficial Ljubljana Graphic Art School, had been awarded the Grand Prize at the 3rd International Biennale in Tokyo and the 8th Art Biennial in São Paulo in 1965 (

Zrinski 2010, pp. 206–7).

Importantly, the conflicting interests between the expectations of the members of the local artistic circles and the state authorities only appeared to be oppositional. The Yugoslavian politicians saw the periodic graphic exhibition as a useful tool to promote a positive image of socialism and promote the country on the international arena, giving the local society a sense of pride. Any explicit criticism of the authoritarian power and its ideology was not possible, even in a country characterised by a significant level of freedom such as Yugoslavia. Non-conformist discourse operated by means of softer, often non-vocal implications, and with the quiet consent of the authorities. This phenomenon recalls a tacit acceptance procedure, which is a method of policymaking common in the international relations environment, best described by the Latin aphorism: qui tacet consentire videtur— ‘he who is silent is taken to agree’. The silent acquiescence on the part of seemingly entirely hegemonic centres of power raises the question of who, in fact, had the power in these exhibitions.

The Graphic Arts Biennial in Ljubljana was meant to serve as a model example of the application of soft power that significantly helped reconnect disjointed societies and establish a ‘contact zone’ for the non-aligned geopolitical order. In fact, the soft power strategy quickly became a background to the curatorial campaign oriented towards promoting artists. This cultural event created an unparalleled opportunity for printmakers working behind the Iron Curtain to enter into a dialogue with the global art world. However, the dialogue between the artists was rarely held in person. Artists could only exchange ideas by proxy through transferring prints, which silently represented their ideas on the walls of the Moderna galerija. Artists did not travel as much as their prints, making the concept of networks of artists to appear to be a highly problematic idea. On the other hand, curators travelled much more extensively than the artists, creating a network of cultural managers. The exhibitions of graphic art and the contacts between curators that followed their emergence facilitated cultural exchange within a European cultural context and instigated an expansion of the network of exhibitions that spread across the globe from Ljubljana to Tokyo. The indirect impact NAM had through the Ljubljana’s Biennial on the entire network of exhibitions helped to widen participation because a number of artists from the Third World countries could join the international print circuit, disestablishing the existing bilateral division of cultural hegemony in the Cold War.

My inquiry, therefore, leads to a three-fold conclusion. First, it demonstrates that the Cold War socialist world cannot be seen only in black and white. Contrary to the images of the Cold War shown in film, photography, and often graphic art, the actual image of the world was far from a monochrome uniformity. Even though the Ljubljana’s Graphic Arts Biennial was officially organised in compliance with the dogmas of the Yugoslav political establishment, their organisers managed to take advantage of the authorities’ inertia and smuggle in and out a nonconformist discourse that was oriented towards benefiting arts more than politics. Secondly, the example of the curatorial management of the exhibition proves that cultural diplomacy really abhors a vacuum. The informal patterns that governed Ljubljana’s Biennial left a fertile middle ground for curators to step into the political game and take over the political no man’s land.

Finally, the emergence of the third space during Ljubljana’s graphic art biennials would not be possible if not for the idiosyncrasy of the graphic art and the hermetic construction of the national school of printmakers, which fuelled these shows with their artworks. Knowledge about graphic art is generally acquired through study in a master-apprentice system, which makes the peculiarities of this art particularly difficult for a third party to intellectually dominate. Additionally, printmaking has often been underappreciated, mostly because it produces multiples of the original design, which leads to an assumption that an artistic print is merely an outcome of mass production that has very little to do with high art. Considering print to be a mere craft dulled the vigilance of Yugoslav censorship and the political establishment, and if graphic art was perceived more as a craft and closer to the ideal of the working classes. In addition, Yugoslavia had a strong tradition of wartime partisan graphics.

6 Many of the partisans became key figures in Yugoslavia’s public life after World War II ended.

Another important factor that allowed printmaking to win a significant degree of independence in Ljubljana was the fact that socialist realism in Yugoslavia took a much more progressive form than in the Soviet Union (

Matvejević 2001, p. 13). After the Tito-Stalin split, Yugoslavia was also seeking its independence in the field of arts. Socialist realism in Yugoslavia lost on its validity in 1952, four years after the split with Stalin. In that year, Miroslav Krleža, the famous writer and communist, delivered a critical speech at the Third Congress of Yugoslav Writers, titled “On Cultural Freedom” in which he condemned socialist realism. At the same time, he defended the “modernist” and autonomist right of individual writers, which then became an official aesthetic doctrine of Yugoslav socialism, which was meant to correspond with the model of workers’ self-management (

Šuvaković 2006, p. 101). Printmaking, since the medium offering a broad range of possibilities for experimentation, could therefore epitomise progress and modernity, and so it could support the ideas of independence and socialist progress so crucial for the development of Yugoslavia self-management. The tightly-knit circle of Yugoslav printmakers therefore won a significant level of independence, which translated into the pluralistic shape of the early editions of the Biennial. These reasons allowed artistic printmaking in Ljubljana to achieve a much stronger position than other artistic media. Graphic art can be therefore seen as a refuge of the arts and, at the same time, a medium of freedom, which played a key role in the process of removing the Iron Curtain.