Documentary Photography from the German Democratic Republic as a Substitute Public

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Öffentlichkeit Versus Ersatzöffentlichkeit in the GDR

“organise the debates among its members about the policies of the state bureaucracy, but also the debates among the citizens at large about their political interests as well as their social and economic needs. This public sphere of the Party had two typical features: first, it was hierarchically structured in accordance with the hierarchy of the party organization; second, it left no room for competing public spheres. The Party was expected to lead and by extension to control the public space; by that I do not mean only the administration of the state but also the public communication among the citizens.”

3. GDR Documentary Photography as a Substitute Public Sphere

4. Summary and Outlook

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahrmann, Hannes. 2017. The Fall of the Wall: The Path to German Reunification/Hannes Bahrmann, Christoph Links. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:101:1-201704203328 (accessed on 12 April 2018).

- Barron, Stephanie, Sabine Eckmann, and Eckhart Gillen. 2009. Art of Two Germanys-Cold War Cultures. New York and London: Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1984. Image, Music, Text/Roland Barthes; Essays Selected and Translated by Stephen Heath. London: Flamingo. [Google Scholar]

- Bathrick, David. 1995. The Powers of Speech: The Politics of Culture in the GDR. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beiler, Berthold. 1959. Parteilichkeit Im Foto. (Probleme d. Fotografie; 3). Halle: Fotokinoverl. [Google Scholar]

- Beiler, Berthold. 1977. Denken Über Fotografie. Leipzig: Fotokinoverl. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, Michael, ed. 2007. Die Unerträgliche Leichtigkeit Der Kunst: Ästhetisches Und Politisches Handeln in Der DDR. KlangZeiten: Musik, Politik Und Gesellschaft; ZDB-ID: 21851724 2. Köln: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Bessel, Richard, and Ralph Jessen. 1996. Die Grenzen der Diktatur: Staat und Gesellschaft in der DDR/herausgegeben von Richard Bessel und Ralph Jessen. Sammlung Vandenhoeck. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, Paul. 2010. Within Walls: Private Life in the German Democratic Republic. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2017. Image Acts: A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Rob, Keith Bullivant, and Godfrey Carr, eds. 1995. German Cultural Studies: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Craig J. 1992. Habermas and the Public Sphere/Edited by Craig Calhoun. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Akademie der Künste zu Berlin. 1979. Sinn und Form. Heft 2. Berlin: Rütten & Loening. [Google Scholar]

- Domröse, Ulrich. 2012. Geschlossene Gesellschaft: Künstlerische Fotografie in Der DDR 1949–1989 = The Shuttered Society: Art Photography in the GDR 1949–1989. Bielefeld: Kerber. [Google Scholar]

- Domröse, Ulrich, and Berlinische Galerie, eds. 1992. Nichts ist so einfach wie es scheint: Ostdeutsche Photographie; 1945–1989 [Ausstellung vom 4. Juni 1992 bis 19. Juli 1992]. Gegenwart Museum. Berlin: Berlinische Galerie. [Google Scholar]

- Simon During. 1999. The Cultural Studies Reader/Edited by Simon During, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Emden, Christian, and David R. Midgley. 2012. Changing Perceptions of the Public Sphere. Edited by Christian J. Emden and David Midgley. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich, Wolfgang. 1994. Die Andere Deutsche Literatur: Aufsätze Zur Literatur Aus Der DDR/Wolfgang Emmerich. Opladen: Westdt. Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Forst, Rainer. 2001. The Rule of Reasons. Three Models of Deliberative Democracy. Ratio Juris 14: 345–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulbrook, Mary. 2005. The People’s State: East German Society from Hitler to Honecker/Mary Fulbrook. Vol. 253, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaus, Günter. 1983. Wo Deutschland liegt: Eine Ortsbestimmung/Günter Gaus. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards, Jürgen, and Friedhelm Neidhardt. 1990. Strukturen und Funktionen moderner Öffentlichkeit: Fragestellungen und Ansätze. Veröffentlichungsreihe der Abteilung Öffentlichkeit und Soziale Bewegungen des Forschungsschwerpunkts Sozialer Wandel, Institutionen und Vermittlungsprozesse des Wissenschaftszentrums Berlin für Sozialforschung, 90,101. Berlin: WZB, Abt. Öffentlichkeit und Soziale Bewegung. [Google Scholar]

- Gripsrud, Jostein. 2011. The Public Sphere. 4 vols. London: SAGE, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 2008. Art Power. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 2014. The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and beyond; Translated by Charles Rougle. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society/Jürgen Habermas; Translated by Thomas Burger with the Assistance of Frederick Lawrence. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen, Nick Crossley, and John Michael Roberts. 2004. After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. Edited by Nick Crossley and John Michael Roberts. Sociological Review Monograph. Oxford and Malden: Blackwell Publishing/Sociological Review. [Google Scholar]

- Hartewig, Karin, and Alf Lüdtke. 2004. Die DDR Im Bild: Zum Gebrauch Der Fotografie Im Anderen Deutschen Staat. Göttingen: Wallstein. [Google Scholar]

- Hauswald, Harald. 2013. Ferner Osten: Die Letzten Jahre Der DDR; Fotografien 1986–1990/Harald Hauswald. Hrsg. von Mathias Bertram. Leipzig: Lehmstedt. [Google Scholar]

- Herminghouse, Patricia A. 1994. Literature as “Ersatzöffentlichkeit”? Censorship and the Displacement of Public Discourse in the GDR. German Studies Review 17: 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Herzogenrath, Wulf. 1992. ‘Zustandsberichte’. Deutsche Fotografie Der 50er Bis 80er Jahre in Ost Und West: [Eine Ausstellung Des Instituts Für Auslandsbeziehungen, Ausstellungsdienst Berlin]. Stuttgart: Inst. für Auslandsbeziehungen. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst Leipzig, and Joachim Jansong. 1993. Fotografie. Leipzig: Hochsch. für Grafik und Buchkunst. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Heinz, and Rainer Knapp. 1987. Fotografie in Der DDR: Ein Beitrag Zur Bildgeschichte. Leipzig: Fotokinoverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hohendahl, Peter Uwe. 1995. Recasting the Public Sphere. October 73: 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohendahl, Peter Uwe, and Patricia Herminghouse. 1983. Literatur der DDR in den siebziger Jahren/herausgegeben von P.U. Hohendahl und P. Herminghouse. Edition Suhrkamp; n.F., Bd. 174. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Honnef, Klaus, Johannes Bönsel, and Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn. 1979. In Deutschland: Aspekte Gegenwärtiger Dokumentarfotografie; Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, 23.6. Bis 29.7.1979. Köln: Rheinland-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- James, Sarah E. 2013. Common Ground: German Photographic Cultures across the Iron Curtain. New Haven and Conn: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jarausch, Konrad H. 1999. Dictatorship as Experience: Towards a Socio-Cultural History of the GDR. Edited by Konrad H. Jarausch. Translated by Eve Duffy. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kempcke, Günter. 1984. Handwörterbuch der deutschen Gegenwartssprache/von einem Autorenkollektiv unter der Leitung von Günter Kempcke. Berlin: Akademie. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn, Karl Gernot. 1997. Caught: The Art of Photography in the German Democratic Republic/Karl Gernot Kuehn. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laberenz, Lennart, ed. 2003. Schöne neue Öffentlichkeit: Beiträge zu Jürgen Habermas’ ‘Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit’. Hamburg: VSA-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Leeder, Karen J. 2015. Rereading East Germany: The Literature and Film of the GDR/Edited by Karen Leeder. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liebscher, Thomas. 2011. Leipzig-Fotografie Seit 1839: ... Aus Anlass Der Ausstellung ‘Leipzig. Fotografie Seit 1839’ [27. Februar Bis 15. Mai 2011 Im Grassi-Museum Für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig, Im Stadtgeschichtlichen Museum Leipzig Und Im Museum Der Bildenden Künste Leipzig]. Leipzig: Passage-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Anne. 2001. Foto-Anschlag: Vier Generationen Ostdeutscher Fotografen, 1st ed. Leipzig: Seemann. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Gerd, and Jürgen Schröder, eds. 1988. DDR Heute: Wandlungstendenzen Und Widersprüche Einer Sozialistischen Industriegesellschaft. Tübingen: G. Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Mittman, Elizabeth. 1994. Locating a Public Sphere: Some Reflections on Writers and Öffentlichkeit in the GDR. Women in German Yearbook 10: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, Norbert, ed. 2004. Utopie Und Wirklichkeit: Ostdeutsche Fotografie 1956–1989. Bönen: Kettler. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Beate. 2006. Stasi-Zensur-Machtdiskurse: Publikationsgeschichten und Materialien zu Jurek Beckers Werk. Studien und Texte zur Sozialgeschichte der Literatur, Bd. 110. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Römer, Dietrich. 1968. Ulbrichts Grundgesetz, die sozialistische Verfassung der DDR/mit einem einleitenden Kommentar von Dietrich Müller-Römer. Köln: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik. [Google Scholar]

- Negt, Oskar, and Alexander Kluge. 1993. Public Sphere and Experience: Toward an Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. Theory and History of Literature, v. 85. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Outhwaite, William. 2009. Habermas: A Critical Introduction, 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Bernhard, and Hartmut Wessler. 2008. Public Deliberation and Public Culture: The Writings of Bernhard Peters, 1993–2005. Edited by Hartmut Wessler. Translated by Keith Tribe. Foreword by Jürgen Habermas. Transformations of the State. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Plenzdorf, Ulrich, and Romy Fursland. 2015. The New Sorrows of Young W. Pushkin Collection. London: Pushkin. [Google Scholar]

- Raupp, Juliana. 2001. Kunstöffentlichkeit im Systemvergleich: Selbstdarstellung und Publikum der Nationalgalerien im geteilten Berlin/Juliana Raupp. Publizistik (Münster in Westfalen, Germany). Münster: Lit, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Rehberg, Karl-Siegbert, Wolfgang Holler, Paul Kaiser, Neues Museum Weimar, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, and Ausstellung Abschied von Ikarus, eds. 2012. Abschied von Ikarus. Bildwelten in der DDR-neu gesehen: Begleitend zur Ausstellung im Neuen Museum Weimar, 19. Oktober 2012 bis 3. Februar 2013; Verbundprojekt Bildatlas: Kunst in der DDR. Köln: König. [Google Scholar]

- Reifarth, Gert. 2003. Die Macht der Märchen: Zur Darstellung von Repression und Unterwerfung in der DDR in märchenhafter Prosa (1976–1985). Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann. [Google Scholar]

- Reimann, Brigitte. 1998. Franziska Linkerhand: Roman. Ungekürzte Neuausg., 1. Aufl. Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Von Richthofen, Esther. 2009. Bringing Culture to the Masses: Control, Compromise and Participation in the GDR. New York: Berghahn Books, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Rittersporn, Gábor Tamás, Malte Rolf, and Jan C. Behrends, eds. 2003. Sphären von Öffentlichkeit in Gesellschaften Sowjetischen Typs: Zwischen Partei-Staatlicher Selbstinszenierung und Kirchlichen Gegenwelten = Public Spheres in Soviet-Type Societies: Between the Great Show of the Party-State and Religious Counter-Cultures. Komparatistische Bibliothek, Comparative studies series, Bd. 11; Frankfurt am Main and New York: P. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, Thomas, Frank Wolfgang Sonntag, and Peter Grimm. 2015. Weg in den Aufstand: Band 2, 01.12.1988-7.10.1989. Leipzig: Araki Verlag, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rühle, Ray. 2003. Entstehung von Politischer Öffentlichkeit in Der DDR in Den 1980er Jahren Am Beispiel von Leipzig. Münster and London: Lit. [Google Scholar]

- Rüther, Günther, ed. 1997. Literatur in Der Diktatur: Schreiben Im Nationalsozialismus Und DDR-Sozialismus. Paderborn: Schöningh. [Google Scholar]

- Schiermeyer, Regine. 2015. Greif zur Kamera, Kumpel!: Die Geschichte der Betriebsfotogruppen in der DDR/Regine Schiermeyer. Edited by Forschungen zur DDR-Gesellschaft. Berlin: ChLinks Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Sabine. 2014. Fotografie zwischen Politik und Bild: Entwicklungen der Fotografie in der DDR. Kunstgeschichte, Bd. 84. München: Utz. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, James C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Segert, Dieter. 2002. Die Grenzen Osteuropas: 1918, 1945, 1989-Drei Versuche, Im Westen Anzukommen. Edited by Dieter Segert. Frankfurt/Main: Campus-Verl. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman, Marc. 1997. What Remains? East German Culture and the Postwar Public. Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series; Washington, DC: American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Susen. 2016. Critical Notes on Habermas’s Theory of the Public Sphere. SA 5: 37–62. Available online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/1101/1/Simon%20Susen%20’Critical%20Notes%20on%20Habermass%20Theory%20of%20the%20Public%20Sphere’%20SA%205(1)%20pp%20%2037-62.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2016).

- Thümmler, Marc. 2009. Radfahrer. Documentary. Available online: http://www.bpb.de/mediathek/125419/radfahrer (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Wallenburg, Ullrich, and Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Cottbus, eds. 1990. ‘Zeitbilder: Wegbereiter der Fotographie in der DDR’. In Fotoedition. Fotoedition, Nr. 11. Cottbus: Kunstsammlungen. [Google Scholar]

- Wolle, Stefan. 1998. Die heile Welt der Diktatur: Alltag und Herrschaft in der DDR 1971–1989/Stefan Wolle. Schriftenreihe (Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung); Bd. 349. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. [Google Scholar]

- Zentrale Kommission Fotografie der DDR. 1947–1991. Fotografie: Zeitschrift für kulturpolitische, ästhetische und technische Probleme der Fotografie. Heft 7, 1954; Heft 8/9 1960. Leipzig: Fotokinoverlag. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Quoted from Karl Gernot Kuehn (Kuehn 1997, p. 50). |

| 2 | Wulf Herzogenrath for example stresses a pre-eminence of social documentary photography as it stands in solidarity with the people. (Herzogenrath 1992, p. 30) Cf. (Domröse 2012, p. 21). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Juliana Raupp, ‘Kunstöffentlichkeit in der DDR als Gegenöffentlichkeit’, in (Rittersporn et al. 2003, p. 235). Cf. (Raupp 2001). |

| 6 | Axel Goodbody, Dennis Tate, Ian Wallace, ‘The Failed Socialist Experiment: Culture in the GDR’ (Burns et al. 1995, p. 180). |

| 7 | „Wenn man von der festen Position des Sozialismus ausgeht, kann es meines Erachtens auf dem Gebiet von Kunst und Literatur keine Tabus geben. Das betrifft sowohl die Fragen der inhaltlichen Gestaltung als auch des Stils–kurz gesagt, die Fragen dessen, was man die künstlerische Meisterschaft nennt.“ Erich Honecker at the fourth meeting of the central committee of the SED, December 1971. (Schiermeyer 2015, p. 238) |

| 8 | Cf. (Schmid 2014, pp. 201–9). |

| 9 | Harald Hauswald in email correspondence with the author, 9 June 2018. |

| 10 | Cf. Christoph Diekmann, Preface, in (Hauswald 2013) |

| 11 | Interview with Harald Hauswald, 29 December 2017. |

| 12 | I follow the accruement and transformation of public sphere in Germany, as I view Jürgen Habermas’ The structural transformation of the public sphere as the starting point of an analysis of public sphere, which does include European semantics of the word ‘public’, but is specifically rooted in the German language area. |

| 13 | The church assumed the role of an alternative public sphere in the GDR. It undermined the monopoly on truth of the SED state by inviting ideologically non-conform artists and writers as well as discussing controversial topics. Cf. e.g. (Wolle 1998, pp. 247–55). |

| 14 | Schröder, Jürgen, ‘Literatur als Ersatzöffentlichkeit? Gesellschaftliche Probleme im Spiegel der Literatur’, in (Meyer and Schröder 1988, p. 111). |

| 15 | Quoted in (Gripsrud 2011). Cf. (Forst 2001). |

| 16 | Simone Barck, Christoph Classen and Thomas Heimann, ‘The Fettered Media. Controlling Public Debate’, in (Jarausch 1999, p. 224). |

| 17 | Robert Weimann, ‘Kunst und Öffentlichkeit in der Sozialistischen Gesellschaft. Zum Stand der Vergesellschaftung künstlerischer Verkehrsformen’, in (Deutsche Akademie der Künste 1979, p. 221). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | „Die Konzentration der öffentlichen Debatte auf die Stasi darf nicht den Blick dafür verstellen, daß sie lediglich einen Teil der perfektionierten Sicherheits-, Disziplinierungs- und Überwachungsstruktur bildete. […] Die gezielte Denunziation von Kollegen, Nachbarn, Mitschülern und Kommilitonen prägte ebenso den Alltag wie das ständige Verfassen breit angelegter Berichte.“ (Wolle 1998, p. 153) |

| 20 | The Stasi, short for Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (Ministry for State Security) was the GDR’s secret police founded in the 1950s. Its main objective was the Socialist Unity Party’s preservation of power by means of spying and intimidation of GDR citizens. Cf. http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/deutsche-geschichte/stasi/218372/definition (7 June 2018). |

| 21 | Interview with Werner Mahler, 11 October 2017. |

| 22 | Interview with Harald Hauswald, 29 December 2017. |

| 23 | Öffentlichkeit, die; 1. Die Bevölkerung außerhalb ihrer persönlichen, privaten Sphäre […]. (Kempcke 1984, p. 839). Cf. (Müller-Römer 1968) |

| 24 | Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and beyond/by Boris Groys; Translated by Charles Rougle., [New] ed. (London: Verso, 2014), 9. Cf. (Groys 2008). |

| 25 | The term was originally coined by art historian Klaus Honnef but is a widely known concept in German photo theory. (Honnef et al. 1979, pp. 8–32)//Cf. (Barron et al. 2009, p. 198; Domröse 2012, p. 174). |

| 26 | Muschter quoted in (Schmid 2014, p. 241). |

| 27 | Interview with Harald Hauswald, 29 December 2017. |

| 28 | Literary critic Roland Barthes coined the term photographic message, which is composed of a denoted and a connoted message. The former is described as “pure and simple denotation of reality” whilst the latter refers to social and cultural manners. Cf. (Barthes 1984, p. 28). |

| 29 | Stuart Hall, ‘Encoding, Decoding’, in (During 1999, pp. 507–17). |

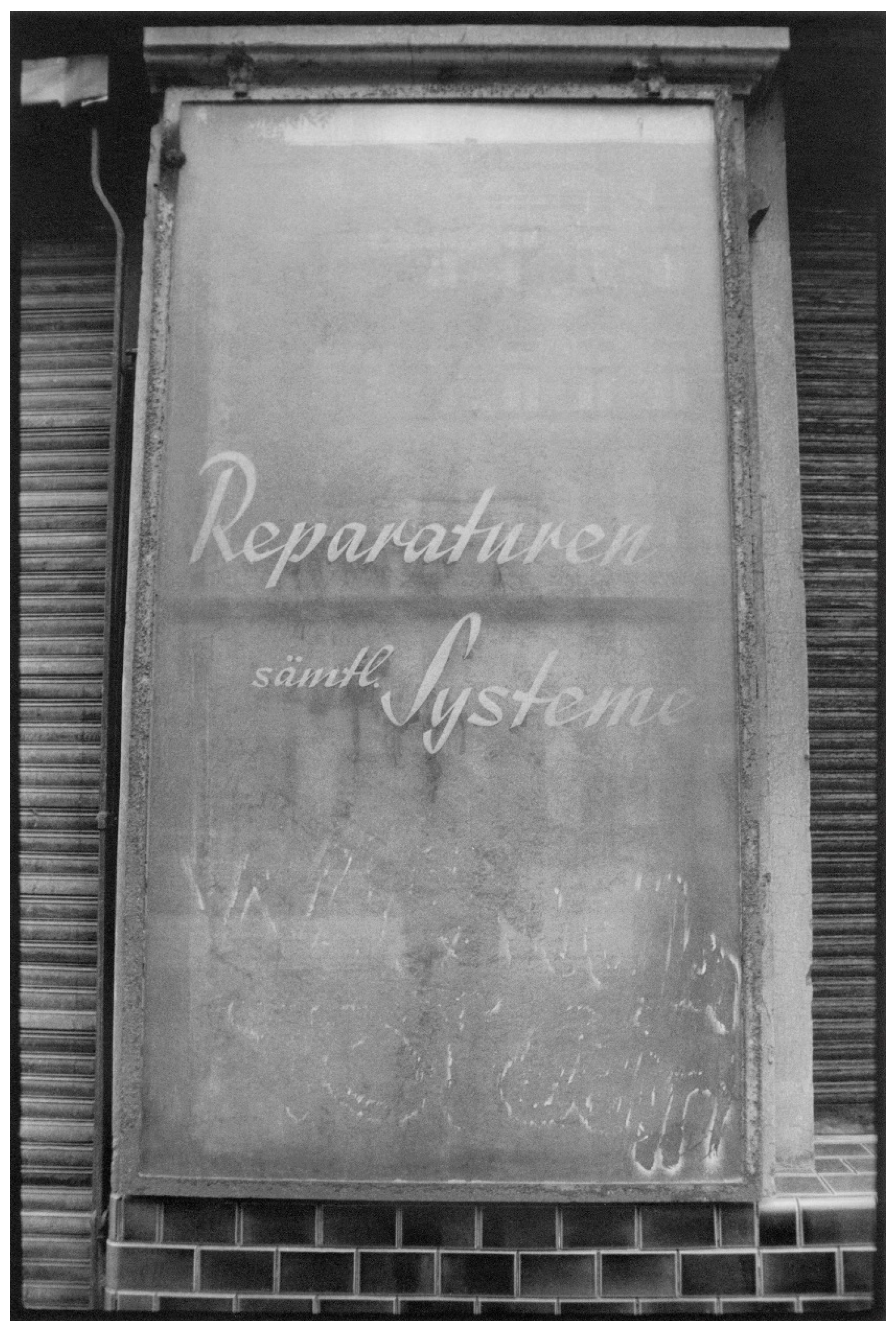

| 30 | ‘Sämtl.’ (abbreviation for ‘sämtliche’ in German, having a strong connotation of ‘comprehensively’ or ‘each and every’ does not translate well into English in this case). |

| 31 | Quoted after Alf Lüdtke, ‘Kein Entkommen? Bilder-Codes und eigen-sinniges Fotografieren; eine Nachlese.‘ in (Hartewig and Lüdtke 2004, p. 235). |

| 32 | I investigate this question in depth in my ongoing doctoral thesis ‘Ostkreuz–Agency of Photographers. Tracing the Influence of GDR Social Documentary Photography in Contemporary Practice’. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pfautsch, A. Documentary Photography from the German Democratic Republic as a Substitute Public. Humanities 2018, 7, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030088

Pfautsch A. Documentary Photography from the German Democratic Republic as a Substitute Public. Humanities. 2018; 7(3):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030088

Chicago/Turabian StylePfautsch, Anne. 2018. "Documentary Photography from the German Democratic Republic as a Substitute Public" Humanities 7, no. 3: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030088

APA StylePfautsch, A. (2018). Documentary Photography from the German Democratic Republic as a Substitute Public. Humanities, 7(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030088