In his 1969 essay, Adorno famously scrutinizes the question “What is German?”, rejecting a presupposed and simplistic notion of “Germanness” (

Adorno and Levin 1985, p. 121)

1. This question, though at first glance simplistic in its formulation, encapsulates a key investigation in a contentious debate that has been raging in Germany since the end of WWII. Specifically, what does it mean to be German after Hitler and National Socialism? Being proud to be a German was deeply problematic because of the signification of Heimat, or homeland, during the Third Reich.

2 In the 19th century, Heimat developed as a strong regional identity marker. During the German Romanticist movement, Heimat became associated with typical rural life and idyllic landscapes, with an emphasis on a strong emotional investment in the places of home. As Elizabeth Boa and Rachel Palfreyman point out in

Heimat A German Dream: Regional Loyalties and National Identity in German Culture 1890–1900, the unification of Germany in 1871, as well as the Industrial Revolution, brought with it an intense paranoia and fear of a mass exodus from rural areas within Germany to more urban landscapes, dividing German identity between regional and national identity, as well as rural and urban identity (

Boa and Palfreyman 2011, p. 1). Heimat thus developed as an idea of emotional attachment to home, and grew out of this fear of abandonment. The National Socialists utilized this idea of attachment to soil to further their racist rhetoric, from

Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) to

Lebensraum (Living Space). Heimat became a call to action associated with racial ideologies of purity, and anyone who fell outside of the fascist ideal of a “racially pure” national identity was deemed as a threat to the National Socialist regime.

As a reaction to the fascist appropriation of the romanticist ideal of Heimat, national identity was reevaluated as a depoliticized marker of identity. From 1945–1965 Heimat was seen as an extension of nostalgia; a longing for a simpler time. Thus, Heimat became backwards-looking, focusing on rural life prior to both WWI and WWII. With a renewed interest in the memory of the Holocaust and WWII through widely publicized events, such as the Eichmann Trial (1960) and the NBC Holocaust miniseries (1978), as well as the Student movement of 1968, the question “What is German?” began to be investigated anew. The strangeness of being German in the postwar period led many to question their sense of home and to distance themselves from the previously racially laden or depoliticized definition of Heimat. In the decades since the war, arguments about German national identity have oscillated between vehement national identification and apathetic disavowal. Heimat evolved into a liminal space and a critical threshold for contemporary generations. As the decades passed, younger generations began to pursue the question “What is German?” by investigating silences. The National Socialist past was talked about in the public sphere, but not necessarily investigated in the private realm. What does it meant to be a German when your grandparents and parents were part of the Nazi regime? The Nachgeborenen, the postwar generation, began to grapple with their national identity. This generation felt an immense responsibility: the burden to bear witness to the crimes of the past from the vantage point of the contemporary landscape.

1. The Genealogy of Place: Founding Heimat in the Generationsroman

In my reading of

Das endlose Jahr, I analyze Heimat as more than solely an emotional experience and a backward-looking model. Instead, Heimat can be understood as an extension of nostalgia, or more specifically, nostalgia for a certain place and time, which can manifest itself as forward-looking. In

The Future of Nostalgia, Svetlana Boym emphasizes that nostalgia is longing for a home that no longer exists, or perhaps has never existed at all (

Boym 2001, p. 2). Boym continues by pointing out that we often associate nostalgia with a longing for a placem when it really also is a longing for a different time (

Boym 2001, p. 4). Nostalgia is the process of revisiting a specific time in history from the vantage point of the present. As Boym notes, nostalgia is therefore both retrospective, as well as prospective (

Boym 2001, p. 6). By searching through the palimpsestic traces that remain in our contemporary landscape, we rediscover something about the past, but we also gather information about our present and establish a framework for how a certain event from the past will be remembered in the future. In

Excavation and Memory, Walter Benjamin notes that “he who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging” (

Benjamin et al. 2005, p. 576).

3 Those who seek to shape the future, understand their present, and experience history, must dig deep within the trenches of the past. In

Das endlose Jahr the past is a buried image, a layering of multiple parts that must be excavated from the soil to create a whole.

Heidenreich’s memoir can be characterized as part of the more contemporary network of

Familien-

und Generationsromane (family and generation novels), precisely because it features multiple generations, retelling the experiences of grandparents, parents, and their children, as they dig deep into the family archives to uncover and come to terms with the Nazi past.

4 Elisabeth Krimmer characterizes family novels as a “highly popular contemporary genre that tells ‘big history’ in the form of family history” often amalgamating fact and fiction (

Krimmer 2015, p. 38). In

Geschichte im Gedächnis, Aleida Assmann makes clear that

Generationsromane seek to reassure the character’s “identity vis-à-vis her own family [as well as through] German history” (

Assmann 2007, p. 73).

Heidenreich pieces her sense of self back together through the fragmented memories of family narratives. As Susan Luhmann attests,

Generationsromane seek to “establish the extent of a family member’s guilt, but also to show the continued denial of such guilt within their families” (

Luhmann 2009, p. 176). Heidenreich struggles with her own sense of guilt, precisely because of her families’ implication with the Nazi regime, and sets out on a quest to retrace the steps of her past.

In an effort to uncover that past, Heidenreich probes family stories, as well as official history, and emphasizes the unreliable nature of memory by exploring the dichotomy between the private and the public, focusing on uncovering the past by contrasting personal memories with official collective memory. Akin to Ruth Klüger’s 1992 memoir

weiter leben: Eine Jugend (Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered),

Das endlose Jahr problematizes memory and presents it as fragmented, and at times, inaccessible. Heidenreich relies on history and family memory to reconstruct the past. However, it is only through Heidenreich’s deep longing for Heimat, her nostalgia for a place and time, that those memories are affectively made real.

5 At the same time, Heidenreich acknowledges the futile desire to capture the past by reanimating places and objects to awaken memories. Similarly, Klüger contends that the desire to memorialize the past in specific sites is generally ineffective, since the essence of timescape cannot be captured, due to the “missing ingredients [such as] the odor of fear…the concentrated aggression, the reduced minds” (

Klüger 1994, p. 67).

6 The palimpsestic traces of history are tangible only insofar as they are tied to a sense of

Örtlichkeit (place). Klüger cautions that you can never truly exhume the essence of a timescape, nor should you strive to. In fact, the essence of

Örtlichkeit may be the closest that we can come to an “authentic” memory experience. Like Klüger, Heidenreich acknowledges that these place markers are necessary bridges that connect us, however imperfectly, to times past.

Örtlichkeit and history intricately intermingle, allowing the past to intrude on the contemporary.

Zeitschaft (timescape) is something that remains sacred and inaccessible after time has passed, while

Örtlichkeit offers a window into the past.

In

Generationsromane “the discursive, social, and political frameworks of the present leave their imprint on individual recollections of the past” (

Krimmer 2015, p. 38). Thus, present discourses and institutions influence the perception of the past, resulting in a memory that is often reshaped by the sites and objects deemed to be historically relevant. In his introduction to

Between Memory and History, Pierre

Nora (

1989) discusses the importance of

lieux de mémoire, or sites of memory, which anchor the collective conscience of a social group. In the immediate post-WWII period, recollections of the war were inundated with fresh memory sites, evoking the recent past.

Das endlose Jahr problematizes space through an ultimately futile search for an originary past.

2. Mothers and Daughters: The Otherness of Being Born

“Welcome home…you look Norwegian” (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 16). The stranger warmly greets Gisela Heidenreich as she waits at a bus stop in Hønefoss, Norway, with her German mother in tow. Upon discovering that the women are in search of Gisela’s birthplace in Klekken, the Norwegian man immediately offers to help drive them to the birth site, an old Norwegian hotel that was once occupied by the Nazis.

7 Since her birth, Gisela has had a distant relationship with her mother, and felt no right to a home, proclaiming that “durch meine Geburt im mit Gewalt besetzten Land habe ich mir kein ‘Heimrecht’ erworben” [Through my birth in a land occupied by force I have not earned a right to a home] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 22). She has always yearned to feel at home, and in an attempt to reconstruct her sense of belonging, Gisela organizes a trip with her elderly mother to visit her birthplace in Klekken.

In

Generationsromane, growing up is often complicated by the outbreak of the war. In Heidenreich’s case, this is even further problematized through her birthplace. Gisela Heidenreich was born at a Lebensborn facility in 1943 in Klekken, during the German occupation of Norway. As Patrizia Albanese outlines in

Mothers of the Nation: Women, Families and Nationalism in 20th Century Europe, the Lebensborn e.V., or Lebensborn (fount of life) registered association was initiated by the SS and formed in 1935 (

Albanese 2006, pp. 37–38). The association sought to raise the birthrate of Aryan children, who were to become the future soldiers and leaders of Germany. The association accomplished this by providing welfare to unmarried, or single German women during their pregnancy. In addition to services provided to women and SS members, it was discovered at the Nuremberg Trials that these facilities often engaged in the transfer of children, mostly orphans, or children kidnapped from Eastern Europe, to families in Germany. The association encouraged and mediated the adoption of children born on site or brought to the Lebensborn facility. As the war progressed, Lebensborn expanded into several occupied European countries with Germanic populations, most prominently in Poland, Denmark, and Norway. Heidenreich’s unwed German mother was transferred to work at the Lebensborn facility from her job as a secretary for the SS-Junkerschule Bad Tölz, an officer’s training school for the Waffen-SS. After her romantic relationship with a prominent married SS officer, Heidenreich’s mother was transported to the Norwegian facility, where she gave birth to Gisela.

Akin to other Lebensborn children, such as Ann-Frid Lyngstad, Heidenreich’s origin story propels her on a quest to get to know her “real” Heimat. Gisela Heidenreich’s mother, Emilie Edelmann, a very composed, stern, and unsentimental woman, often left young Gisela in need of affection. As a child, because of her Lebensborn origin, her biological mother initially disowned her and Gisela was raised by her aunt, whom she referred to as her mother for the first formative years of her life. Later, Gisela’s mother revealed herself to be her real mother, leaving young Gisela confused and rejected. Gisela recalls how her mother would often cross the road abruptly if she saw someone on the sidewalk from the Junkerschule, or even an old neighbor, or friend. Her mother would let go of Gisela’s hand, leaving her alone on the other side of the street, so as not to rouse suspicion that Gisela was her child (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 115). Gisela was never allowed to feel at home, not even in the presence of her mother.

Deprived of both nation and maternal affection, Gisela feels

heimatlos (homeless), a condition that manifests itself as a perpetual feeling of otherness. Whenever Gisela felt secure and at home in her surroundings and in her relationship with her mother, the rug was pulled from under her. The spaces that were supposed to be familiar—the street, the school, and even the home—became spaces of otherness, ultimately becoming what Michel Foucault, in a 1967 lecture to an audience of architects titled “Of Other Spaces”, terms heterotopias. Foucault posits that spaces are formed through society, and rely on social structures of power. However, when the social order is inverted, a disturbance of place occurs (

Foucault and Rabinow 2010, p. 24). Heterotopias are parallel spaces, exemplifying otherness. They are counter-sites and places that are only able to exist in relation to other places, containing the undesirable, in order to make space for the envisioned notion of a utopia elsewhere. They exhibit many layers of meaning in relation to other places. Foucault outlines that heterotopic spaces are transitory spaces where adolescents, pregnant women, or the elderly come to live out a fleeting moment in their lives (

Foucault and Rabinow 2010, p. 5). Thus, the Lebensborn facility in Norway is a kind of crisis heterotopia, where Gisela comes into the world, but is hidden away in a parallel space. Gisela’s existence is therefore riddled with contradictions, a characteristic inherent in heterotopias of deviation. Her world is representative of many dualities, from her struggle between her home in Germany and her birthplace in Norway, to her relationship with her mother.

Heterotopias capture moments that shape how one ultimately sees oneself in relation to the other. Gisela’s mother is a disturbance to Gisela’s process of self-identification, acting as the ultimate stranger, embodying a space that should be familiar, but ultimately becomes

unheimlich (uncanny). To invoke Sigmund Freud’s

Das Unheimliche (The Uncanny), what is

heimlich becomes

unheimlich, precisely because the unfamiliar is initially domestically familiar (

Freud and Gay 1999, pp. 577–81). Simple everyday objects, and even familiar people, feelings, and experiences can suddenly become alien. Thus, the uncanny is something that is strangely familiar, as embodied by the subject’s own simultaneous attraction and repulsion towards the uncanny subject. When we look at Gisela’s relationship with her mother, she is at once the daughter and the hidden, secret Other in the family. Her fractured relationship with her family repeatedly drives her into confrontations with uncanny spaces. As someone without a home, without a mother, and someone who cannot assimilate into the spaces around her, Gisela sees herself as the other. As this other Gisela occupies a space comparable to the Foucauldian heterotopia, insofar as a heterotopic space also questions and subverts the logic governing social functions and relations. The disturbance brought on through the strained mother–daughter relationship creates parallel spaces bearing elements of the heterotopic, from which Gisela is able to reflect on the past and challenge and subvert the logic and functions of the monuments, sites, and places that she encounters.

3. Das Endlose Jahr: Searching for Home in All the Wrong Places

As she stands in a Norwegian museum, the words “welcome home” echo in Gisela’s head, leaving her riddled with guilt. The visit to Klekken was meant as a reconciliation trip between mother and daughter. Emilie’s demeanor as a mother is complicated through her role in the opening of the first Lebensborn facility in Klekken, Norway in 1941. Emilie never shared the details of her troubled past with her daughter, and Gisela learned about Lebensborn only by stumbling upon the salacious reporting of Will Berthold in his fictitious journalistic essays about the “secrets of the Lebensborn houses”, and later, in his 1958 novel,

Lebensborn e.V. Ein Tatsachenroman (Lebensborn registered association: A non-fictional novel). Even during this reconciliation trip in Norway, Emilie often conceals the truth, declining to recall and recount certain facts, locations and instances, eventually outright refusing to even visit many of the sites that hint at the Nazi past in Norway. Gisela treks through Oslo alone, visiting museums and monuments, hoping to fill the gaps in her own biography, yet again, without the help of her mother. At a museum exhibit about the Anti-Nazi resistance in Oslo, Gisela stops dead in her tracks. The sign above the exhibit reads “1943—Et Langt Ar—The Endless Year” (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 33).

8 The exhibit depicts the Nazi occupation of Norway and Hitler’s secret command to overtake the Scandinavian countries. By 9 April 1940 Norway was attacked and occupied in a

Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) action. Gisela cannot muster the courage to keep going, and is afraid of the pain that her birth year has caused for the many families and citizens of Norway. Nevertheless, she pushes on and discovers a jarring display of monuments and photographs of Norwegian citizens who suffered under the occupation of the Nazis.

At its core,

Das endlose Jahr is a memoir about the search for Heimat in all the wrong places. As Ruth Klüger recognizes in

weiter leben, “to conjure up the dead you have to dangle the bait of the present before them, the flesh of the living, [in order] to coax them out of their inertia” (

Klüger 2001, p. 69). The search for places that capture the past and “awaken the dead” are repeatedly intertwined with the task of “returning” home. Gisela must return to the place of her birth in an attempt to piece together the past. The digging up of history and excavation of memory can only be carried out in the shifting ground of the present. For Gisela, sites of memory haunt the present landscape and, through them, she is able to forge a bridge between the dead and the living.

Gisela returns again and again to her birthplace, wandering the streets of her uncanny Heimat, recognizing that we cannot evoke the physical reality of the past, and are forever bound to lose the essence of Zeitschaft. However, the Örtlichkeit can be restored through images, objects, and structures, which bring alive a synthetic Zeitschaft. In other words, though the recreation of the timescape is artificial, as the essence of time cannot be recaptured, the experience is affectively charged, so as to seem real. Gisela has no personal memories of her hometown, and must artificially reconstruct the past.

In

Berlin Childhood around 1900, Walter Benjamin comments on memory and the traces the past leaves behind, noting that photographs can awaken a strong sense of homesickness (

Benjamin et al. 2005, p. 37). Imagery, in general, holds the potential for a powerful affective recall, by introducing a longing for the past and nostalgia for Heimat through visual cues. Images provide an entry point into the past, signaling and reminding the viewer what once was. By relying on recognition through nostalgic cues, such as people and experiences, the image establishes an affective link, bridging the past and present. As David Altheide notes in his analysis of journalism and media,

how certain images and information are presented to us as a society determines

what we believe, in turn shaping our perception of our identity (

Altheide 2002, pp. 42–44).

9 Images can be geared towards an element of nostalgic voyeurism (

Altheide 2002, p. 41). According to Altheide, the viewer feels as if she is witnessing the events through the simulation of a familiar space, often relying on a physical landmark, which animates the imagery of the event in the imagination of the audience (

Altheide 2002, p. 31). Thus, memory is dependent not solely on images, but also on objects and physical sites to capture the attention of the audience and to bring alive the events of the past. These sites, which I refer to as “palimpsest markers”, bring the past alive through recycled and recognizable formats, from specific structures and buildings, to cities, countries and locations more generally. Through palimpsest markers we are able to see traces of the past in the present landscape. Similar to palimpsest manuscripts and architecture, the past has been reused and scraped off to make room for new texts, images and structures. What matters is not what form these palimpsest markers take on, rather, that they encapsulate a feeling of the past and an affective link to history through nostalgia.

When we enter a space, it conjures certain thoughts, and through these thoughts, the spaces become connected to other imagery places. This is how we form and mix memories, allowing the past and present to intersect and collide. Though initially satisfied and emotionally affected by the places, images and things that she absorbed at the Norwegian museum and at her birth site, Gisela still does not

feel at home. The burden of the past weighs heavily on her, but none of the places in and around Oslo have provided that affective bridge between the past and the present that Gisela seeks, leaving her

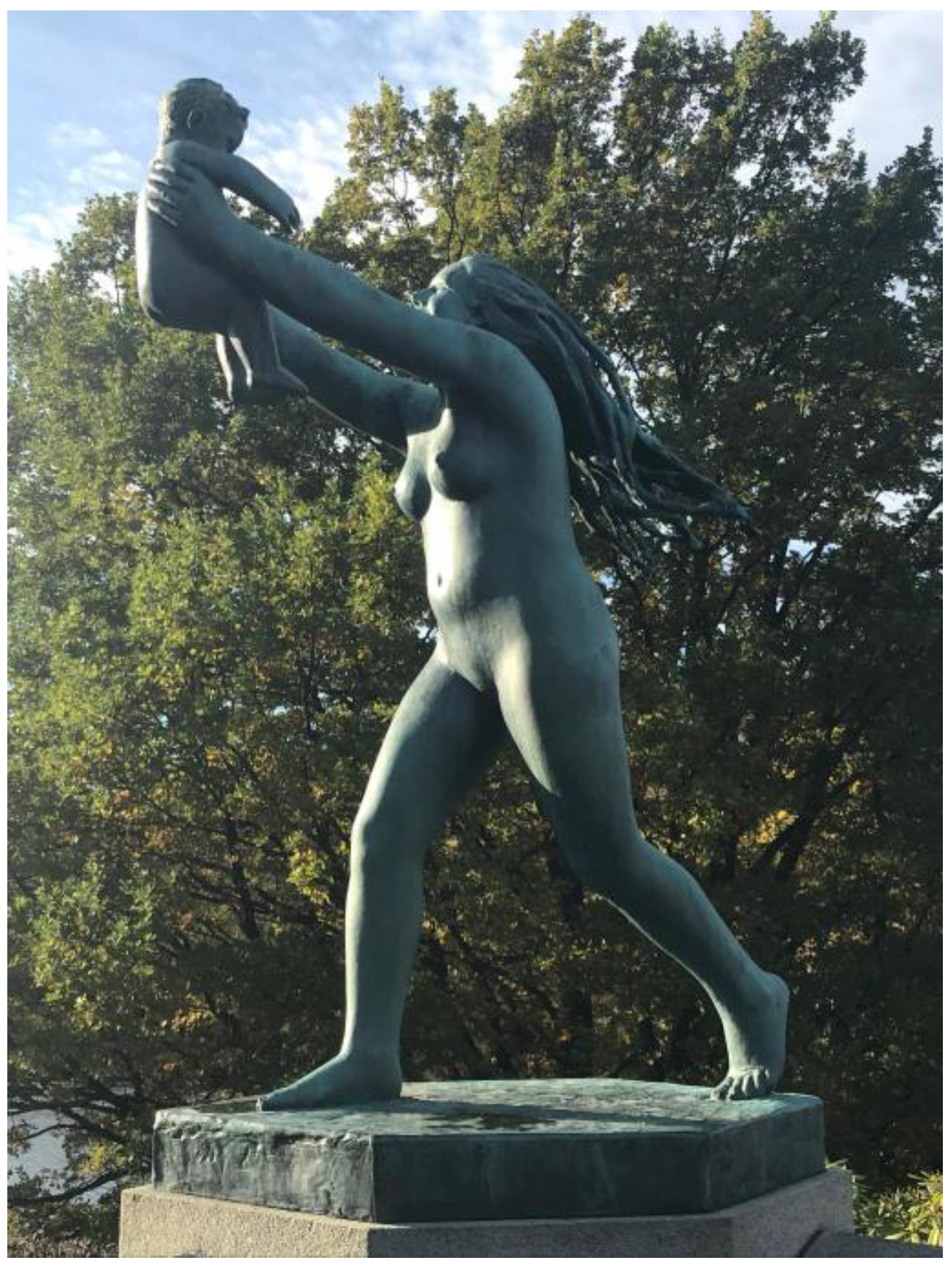

heimatlos (homeless) once again. Unable to relate to her surroundings in Germany and to her “new home” in Norway, she feels disappointed that this trip did not provide her with all of the answers that she was looking for. On her last day before returning to Germany, Gisela decides to take in one last tourist attraction, seemingly unrelated to the war. In an attempt to clear her head, she decides to visit the gigantic Frogner Park, an eighty acre park in the city center of Oslo, housing the Vigeland installation, a project of 212 bronze and granite sculptures designed by the famous Norwegian artist Gustav Vigeland. Gisela’s mother declines to come along once again, claiming that “de Nackerten muss ich mir net noch einmal anschau’n” [I don’t have to look at the naked people again] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 69).

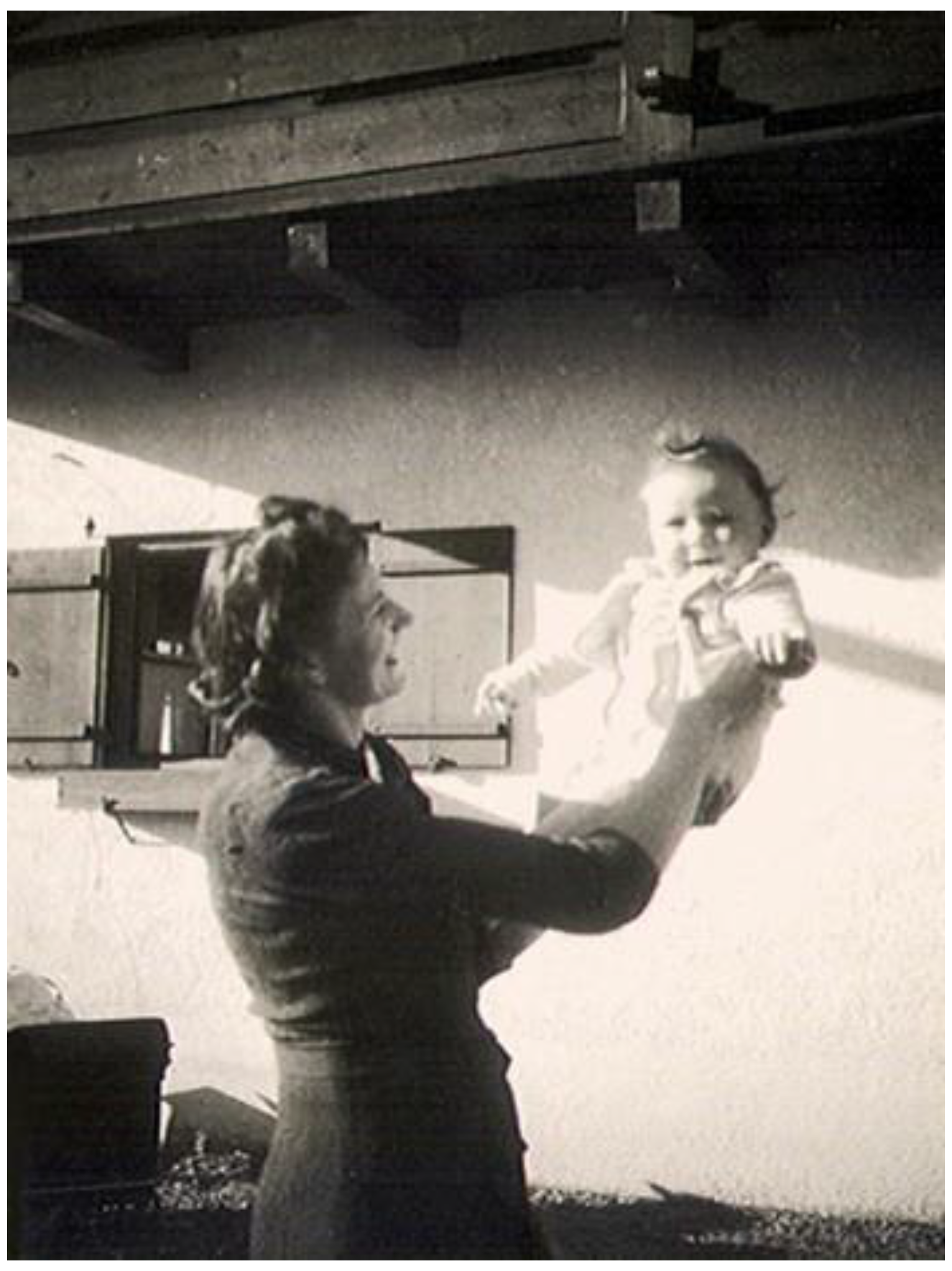

The sculptures depict naked men, women, and babies, designed to represent the evolution of human life from birth to death. As Gisela approaches Vigeland’s sculpture of a mother twirling her young child, she is reminded of a personal photograph. Emilie Edelmann proudly displayed family photos in an album. As a young child, Gisela often searched through this album, looking for photographs of herself, but she never found any. It was not until Gisela discovered a hidden box, labeled “Gisi,” tucked away in a closet, that she saw her first baby pictures (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 192).

The photographs are somber mementos, depicting a stern Emilie and a sad looking blond and blue eyed young Gisela. The only image that captures a moment of genuine happiness is a photo of Emilie proudly twirling an infant Gisela in front of her sister’s house in southern Germany.

As Roland Barthes notes in

Camera Lucida, photography is a medium uniquely in touch with loss, and captures a sentiment as certain as remembrance (

Barthes 2010, p. 70). In other words, photographs have a haunting power to involuntarily creep back up in the viewer at a later time, invoking a memory of the past and capturing a certain affective sentiment of the photographic subject for the viewer. In Barthes’s theory of photographic representation, the image retains what he calls an “umbilical” connection to its referent. The photograph attests that what one sees has indeed existed in the past (

Barthes 2010, p. 82), providing an entry point into history. It is not surprising, then, that Gisela has a strong emotional response to this particular image evoking a maternal moment between mother and child. However, Gisela only recalls this photograph in response to the Vigeland sculpture depicting a similar image of a mother twirling her infant.

Gisela’s first impulse is to recoil at the sight of the naked figures. She reflects, “ich bin nicht besonders begeistert von den naturalistischen Darstellungen fast makelloser Körper, zu sehr erinnern sie mich tatsächlich an Naziskulpturen und die Kunst des sozialistischen Realismus” [I am not thrilled with the naturalistic representations of nearly flawless bodies. They remind me too much of the Nazi sculptures and the art associated with socialist realism] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 70). The sculptures evoke various associations for Gisela, reminding her initially of the many sculptures that Hitler commissioned during the Third Reich. In his essay “Nazi Aesthetics”, Carsten Strathausen focuses on the function of Nazi art, highlighting its aim to depict a romanticized view of reality, an idealized image (

Strathausen 2004, p. 8). The real was transformed into the realm of ideas, through the elevation of one image, usually the representation of the flawless, strong, and often masculine body, as a symbol of the fascist model of nation, health and strength (

Strathausen 2004, p. 8). Here, however, the symbolic image is the antithesis of the Nazi idealized male body. The focus is instead on the mother–child relationship, as an extension of motherland/Heimat, forcing Gisela to confront her own troubled past through her relationship with her mother.

Gisela quickly moves from discomfort to being deeply moved. She notices the similarities between the Vigeland sculptures and her own experience as a mother.

Dennoch rühren sie mich an, manche Szenen wirken tatsächlich wie dem Leben nachgestellt…Eine Figur zieht mich besonders an: Eine junge Frau hebt ein Baby mit ausgestreckten Armen hoch...Ich fotografiere die Plastik von allen Seiten, die Szene ist mir vertraut: Ich erinnere mich, wie ich meine Kinder, als sie so klein waren, ähnlich glücklich durch die Luft wirbelte und wie sie glucksten vor Vergnügen. Warum denn werde ich traurig, werden meine Augen schon wieder feucht?

[Nevertheless they affect me, some scenes even appear to be lifelike…one figure in particular draws me in: A young woman lifts her baby with outstretched arms…I photograph the figure from all sides, the scene is familiar: I remember, when my children were little, how I twirled them through the air as they gurgled with joy. Why then do I become sad and why do my eyes begin to water?].

According to Barthes, a photograph “is never distinguished from its referent (

Barthes 2010, p. 5), and this moment of identification, between sculpture and real-life experience as mediated through a photograph, is integral in animating and triggering Gisela’s affective response to the image of her and her mother, moving her to tears. As Marianne

Hirsch (

1997) points out in

Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory, photographs have a strong affective power in connecting generations. Hirsch outlines the relationship that the generation after bears to the traumatic memory of those who came before. Hirsch’s term, postmemory, focuses on the power of images to signal to the viewer what the past looked like and provides an essential affective link and an edge of specificity. Postmemory can best be described as a haunting intruder, a spectral memory that unexpectedly reintroduces the past in the present. According to Hirsch, images can become historical access points that allow the second generation to understand the context of the historical events. It is precisely the connection between photograph and life that triggers Gisela’s memory of her past. Barthes notes that “a specific photograph reaches me; it animates me, and I animate it” (

Barthes 2010, p. 20). Certain photographs then possess a strong affective attraction between referent and viewer, evoking “tiny jubilations” (

Barthes 2010, p. 16) within the observer.

This kind of emotional connection to her past is what Gisela was desperately searching for through family narratives. Regardless of the bits and pieces of information that she was able to gather in the process of investigating her past, she always felt distant and removed from this history, unable to truly connect. What was missing was an affective link, a space that would bring the past emotionally alive again in the present. As Alison Landsberg notes in

Prosthetic Memory, a transferential space is vital in bringing the past into a thinkable and palatable context for the present (

Landsberg 2004, pp. 120–21). Transferential spaces are aptly named because they transfer memories affectively. Gisela’s affective response to the Vigeland mother and child sculpture is triggered by her own familial connection to history through her mother. Thus, Gisela’s identification process with the sculptures works twofold. First, she is able to relate to the monument because of her own experiences as a mother and also, in part, because of her complex history with her own mother. Secondly, Gisela is able to relate to history through imagery that is also unrelated to her own personal history. It was not until Gisela stood at Frogner Park in Norway that she was able to experience that affective connection to history, bridging an important emotional gap between the past and the present. See

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The most popular attraction sits at the highest point in Frogner Park. Gisela finally arrives at the wrought iron gates that take on the form of human bodies. She has finally come face to face with the forty-six-foot high monolith, made up of 121 human figures rising towards the sky, carved from a single piece of granite. The monolith is designed to represent man’s desire to commune with the spiritual world. The humans embracing each other are carved as if they are being carried towards salvation, propelled upwards together. Work on the structure began in 1924, and was finally unveiled in 1944, a year after Gisela’s birth.

Gisela is struck by the sheer size of the sculpture, but also by its resemblance to images from the concentration camps. She recalls “auch wenn diese glatt und wohlgenährt sind und die Skulptur die Form eines riesigen Phallus hat, erinnert sie mich an die Fotos von den Leichenbergen in den Konzentrationslagern” [Even if the figures are flat and well fed and the sculpture is in the form of a giant phallus, I am still reminded of the photos of mass graves in the concentration camps] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 75). Though Vigeland could not have predicted the resemblance between his “human pillar” and the images of the mass graves and bodies being bulldozed during the liberation of the camps, his intertwined bodies provide a transferential space to catapult Gisela into a moment in history that she herself did not experience. See

Figure 3.

In accordance with Gary Weissman’s argument in

Fantasies of Witnessing, Gisela

feels the need to witness the past as if she were there, to study, remember, and memorialize the Holocaust and the atrocities committed by the Nazis (

Weissman 2004, p. 4). Weissman describes this process of

feeling and visualizing the Holocaust as a “fantasy of witnessing”, and highlights the desire of those who did not live through the event to experience the past, whether through museums, monuments, images, or films (

Weissman 2004, p. 15). Weissmann theorizes this process as a desire to act as a witness to the past. However, as Weissman makes clear, we are not witnessing the actual events of the Holocaust, but instead “experiencing representations of the Holocaust” (

Weissman 2004, p. 20). Whereas firsthand accounts and “family connections grant children of survivors a ‘position of privilege’ closer, as it were, to the Holocaust” (

Weissman 2004, p. 21), non-witnesses must work to construct a different space in relation to the event. Thus, Gisela constructs this space for herself through images, which she is vividly reminded of by Vigeland’s monolith. This phenomenon of reconstructing memory through palimpsest markers and objects is often achieved by recalling the most horror-filled and iconic imagery from the past. In Gisela’s case, though she does not explicitly identify the images by name, she invokes the widely publicized photos of the mass graves from April of 1945, during the liberation of concentration camp Bergen-Belsen.

10 However anachronistically, the human pillar strongly

seems to reference one shot in particular, depicting Dr. Fritz Klein, a Nazi physician tried for his crimes at the Belsen Trials and subsequently hung, standing on a heap of mangled bodies. Much like Vigeland’s monolith, the grey bodies are piled up so high in the Klein photograph that they reach out of the frame, suggesting an endless cascade of corpses. It is no surprise that Gisela is able to call up this memory of the camps when confronted with the gigantic Vigeland sculpture. She herself recalls later in the narrative how, upon watching a film about the liberation of the camps at school, she could not shake the images from her memory. “Nie mehr habe ich die Bilder der lebenden Skelette in den gestreiften Anzügen, in zerschlissene Decken gehüllt, die sich gegenseitig stützen, vergessen…Die Leichenberge. Die Brillen. Die Kleider-und Haarhaufen” [I have never forgotten the images of the living skeletons in striped uniforms, who were enveloped in blankets as they held each other up…the mass graves. The glasses. The heaps of clothes and hair] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 160).

4. Conclusions: Transferential Spaces in Unexpected Places

The same affective link that photographs rely on can be experienced through the awareness of a space. These palimpsest traces, still often physically present in contemporary structures, can often go unnoticed, much as an old family photo can go unnoticed tucked away in a drawer. However, physical markers, such as monuments, cannot be tucked away. The presence of spaces associated with the Nazi past unsettles the setting they occupy, and intrudes on the present landscape. Thus, palimpsest markers haunt the present with memories of the past, and evoke both feelings of nostalgia for, and dread of, Heimat. Heidenreich begins her memoir with a quote from philosopher George Santayana’s

Reason in Common Sense: “Wer sich der Vergangeheit nicht erinnert, ist verurteilt, sie erneut zu durchleben” [Those who do not remember the past are sentenced to relive/repeat it] (

Santayana [1929] 1982, p. 284).

Das endlose Jahr is most immediately a memoir about a woman’s attempt to relive her past through places and spaces.

The many sites, monuments, and images that she is confronted with on her trip to Norway facilitate Gisela’s insistent quest to remember and understand her past. Gisela aptly begins this search in Norway, not Germany. Her obsession with the past and insistence on retracing the steps of history become visible in her quest to find her birthplace. However, Gisela’s trip to Norway is not enough to recreate a complete sense of Heimat.

Gisela returns to Bad Tölz, her childhood home in Bavaria, after suffering sudden sensorineural hearing loss and, quite literally, begins a healing process.

11 On her doctor’s orders to return to Bad Tölz, where she can be surrounded by friends and family (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 216), Gisela sets out on a second journey to come to terms with her past, this time in her German Heimat. She notes upon her arrival, “meine Erinnerungen haben mich heimgesucht” [My memories have haunted me] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 217). The specters of Gisela’s past have driven her back to Germany in an effort to heal. She notes, “vielleicht gehört es zu meiner ‘Heilung’, dass ich an Ort und Stelle endgültig mit meiner Kindheit ‘ins Reine’ kommen kann” [Maybe it is part of my ‘healing process’ that I can here and now definitively come to terms with my childhood] (

Heidenreich 2002, p. 217). Thus, Gisela confronts each childhood trauma, from the time her uncle tried to kill her simply for being an ”SS-Bankert” (SS bastard) to the time the American soldiers burst into her aunt’s house, ransacking their belongings and chasing them out of their home. Gisela approaches each trauma, each memory of her troubled past, through the various sites of her childhood, from Norway to Germany. Each new landscape and each marker awakens a vivid recollection, catapulting Gisela into the memories of her past. With time Gisela’s hearing loss heals, disappearing as suddenly as it came on, and with it her deeply rooted anxieties of being

heimatlos. Gisela makes peace with her former childhood home and even embarks on a journey to get to know her biological father, a married former SS officer.

12 Gisela Heidenreich’s healing process tellingly began in Norway, through encounters with monuments of an unknown past. Her narrative comes full circle as she wanders the streets and sites of her former home in Germany.

Das endlose Jahr accesses memories through palimpsest markers, in an effort to integrate the past into the contemporary landscape, rather than solely coming to terms with it and settling the score. In

The Condition of Postmodernity, David Harvey expresses the view that the modern city, or any material modern space, is like a theater, developing into a series of stages upon which individuals can perform a multiplicity of roles (

Harvey 2000, p. 5). The dependence on physical markers and monuments in

Das endlose Jahr encapsulates a kind of memory stage; in each instance, the memories of the past are relived through places. As Harvey notes, the essence of time is thus impossible to capture from a single perspective. Instead, memory is constructed from multiple perspectives (

Harvey 2000, p. 30), through one memory folding into another as time progresses. As evidenced by Gisela Heidenreich’s journey, discovering Heimat can come from unexpected places. Since timescape is inaccessible, Heidenreich seeks a transferential memory space through often unexpected sites. Thus, Heimat is a process, rather than a static and immovable space, changing in response to historical circumstances and individual recollections. While our identities remain tied to our sense of home and to the collective, our sense of home has become far more malleable. As Adorno points out, “Germanness” is not necessarily a simple identity marker. We strive to consolidate our understanding of history with our understanding of what it means to be at home today—a notion of home that is constantly shifting and evolving.