Abstract

An iconic photograph of Ieshia Evans’ arrest at a Black Lives Matter protest went viral on Twitter. Twitter users’ textual and visual responses to it appear to show recurring patterns in the ways users interpret photographs. Aby Warburg recognized a similar process in the history of art, referring to the afterlife of images. Evaluating these responses with an updated form of iconography sheds light upon this tangled afterlife across multiple media. Users’ response patterns suggest new ways to develop iconological interpretations, offering clues to a systematic use of iconography as a methodology for social media research.

1. Introduction

During an arrest in the American city of Baton Rouge on 5 July 2016, a police officer shot and killed Alton Sterling after having rendered him immobile. Philando Castile was shot and killed during a routine traffic stop in Saint Paul, Minnesota the following day. Both men were African Americans. Video recordings of both deaths went viral on social media. Both events were part of a long string of police killings of African Americans during the past several years, and the tragedies were subsumed into the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest movement (Lebron 2017). Ieshia Evans, a nurse from Pennsylvania, was so outraged by the deaths that she decided to attend a protest scheduled for 9 July in Baton Rouge.

Jonathan Bachman (Reuters) and Max Becherer (AP) were among a number of photographers present to record the day’s events. Evans and other BLM protestors marched through the streets; on the pretext of public safety, police threatened to arrest individuals who refused to clear the road. Both Bachman and Becherer photographed the impassive Evans as she stood in the street while armored police bore down upon her, arrested her, and carted her away (Figure 1 and Figure 2).1

Figure 1.

Arrest of Ieshia Evans at a Black Lives Matter rally in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on 9 July 2016. Photograph by Jonathan Bachman (Reuters).

Figure 2.

Arrest of Ieshia Evans at a Black Lives Matter rally in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on 9 July 2016. Photograph by Max Becherer (AP/Rex/Shutterstock).

One of Bachman’s pictures (Figure 1) rapidly went viral on Twitter, and then spread to traditional broadcast media swiftly afterwards. Regarding the photograph solely on its own merits, it is not difficult to see why it evoked such a strong response. In Figure 1, the central figures are parallel to the picture plane: since none of the figures are blocked from view, the relationship between them appears clear. There is a strong contrast between the frenetic, awkward movement of the two armored police at the left as they advance upon the tranquil Evans in a sundress: they appear to be at the point of touching her in order to arrest her.2 The background of the photograph serves to heighten the contrast between the two central forces: behind the arresting police is a phalanx of armored associates. Behind Evans, there is an expanse of grass and a tree, the branches of which seem to arch away from her. Both the phalanx of police and the tree form lines locking the viewer’s eyes to the center of the picture.

The awkward stance of the police uncannily suggests not that they are rushing forward, but rather that they are jumping backwards, either from fear or by an unseen, even supernatural, force emanating from Evans at the moment they appear to touch her. Formal elements and the peculiarities of the frozen moment, then, allied with the contrast between action and passivity, aggression and preternatural calm, present a profoundly asymmetrical representation of power and action: one coercive and the other moral. The tension in the photograph is all the greater given that similar asymmetric confrontations have resulted in the deaths of many African Americans by U.S. police. The presence of recording witnesses has not been a deterrent, as in the cases of Eric Garner, Laquan Donald, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Alton Sterling, and Philando Castile, to name but a few particularly egregious examples.

This contrast between coercive and moral force, between armored male aggression and a woman whose sundress floats in the breeze, seems an example of punctum. In contrast to the studium, or our general interest in a photograph, the punctum is the element that causes an affective response that “pierces” the viewer (Barthes [1981] 2000, p. 26).

However, the notion of punctum does not do justice to the scale and variety of responses elicited by the photograph on Twitter. Twitter has become a locus of visibility for the BLM movement, in part because of the greater visibility of African Americans there—a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “Black Twitter” (Ince et al. 2016; Sharma 2013). However, the photograph was not merely forwarded and reproduced in isolation: Twitter users paired many other pictures with it and supplied short, pithy observations with their posts. They also presented similar pictures, produced new pictures based upon the original photograph, and explained the characteristics that they saw in common among all of them.3 To an art historian, this will sound familiar: these users were effectively engaged in a contemporary iteration of iconographic practice. This paper looks at the textual and visual responses to Bachman’s photograph of Ieshia Evans. It uses iconography as a method to map some patterns of interpretation and how they connect the photograph to the larger history of image making, focusing upon users’ characterization of the conflict. Indeed, it appears that using iconography on images in social media provides significant advantages over its use when investigating works of fine art.

2. The Status of Photographs Showing Human Conflict

One of the most arresting photographic forms is that which records episodes of human conflict—whether the act itself or the aftermath. How do we read them? Why do we seem to respond to some pictures, such as Bachman’s—to the extent that we call them “secular icons” (Sontag 2003, p. 107)—in marked preference to others, such as Becherer’s (Figure 2)?

Is it even legitimate to view some photographs as “secular icons”? There is a strain within photography criticism that exhibits distrust over whether photojournalistic images can contain any meaning beyond its status as an instantaneous record. Sontag claimed that photographs “give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal” and moreover that photography of conflict can amount to “war pornography” (Sontag [1977] 1979, pp. 9, 12). Barthes described the photograph as “somehow stupid and undialectical”, an “arrest of interpretation” that “teaches me nothing” (Barthes [1981] 2000, pp. 4, 90, 107). It cannot provide context: “photographs do not explain the way the world works; they do not offer reasons or cause; they do not tell us stories with a coherent, or even discernible, beginning, middle, and end. Photographs cannot burrow within to reveal the inner dynamics of historic events” (Linfield [2010] 2012, p. 21). In addition, these theoretical concerns bleed over into the professional world. Zelizer (2010, pp. 3–4) notes that journalists prize words over imagery, because the photograph is unable to convey the more complex issues at hand.

There is truth to these statements. In addition, yet some photographs—Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Mount Suribachi (1945), and Nick Ut’s Accidental Napalm (1972),4 to name but a handful of undisputed classics—seem to possess an ontological status greater than that of being a mere record of a fraction of a second in a specific location. In short, they seem symbolic. Such photographs produce a range of responses from audiences: sympathy, outrage, antagonism, and more. Hariman and Lucaites call such examples “iconic”. They define the iconic photograph as an aesthetically conventional image featuring recognisable subject matter, framed in such a way as to performatively, emotively emphasise conflicts within the society in which it was produced. Simple in composition, the iconic photograph nevertheless provides fertile ground for multiple semiotic codings (Hariman and Lucaites 2007, pp. 30–37). Focusing upon notions of citizenship in the American polity, theirs is a civically oriented elaboration of Barthes’ punctum. Bachman’s photograph seems to fit their definition.

Whereas Sontag saw photography as providing an untrue past, Hariman and Lucaites instead see the photograph as producing our collective memory of the past: that they are instances of making sense, or interpreting, important events. For them, iconic photographs form the starting-point of a dialogue with audiences and artists, who reproduce, re-use, and re-situate them in different contexts: they provide the “provision of figural resources for collective action” (Hariman and Lucaites 2007, p. 12) and are thus seen as providing a vocabulary of symbolic materials.

However, this vocabulary does not arise ex nihilo. Hariman and Lucaites claim that iconic photographs follow recognizable conventions (Hariman and Lucaites 2007, pp. 30–31), but in this assessment and in their subsequent volume—wherein they examine non-iconic photographs that make the viewer “take a second look” (Hariman and Lucaites 2016, p. 45)—they make only brief nods towards any antecedents to their imagery in the photographs.5

This is odd, because photography is not isolated from the prior history of image making. Indeed, they are rarely taken in any form of isolation at all, photographers often taking dozens or hundreds of pictures at a given event. In this pile of imagery, one or two are recognized as being superior to the others. Bachman wrote, “When I came back to my car and I looked at that picture, I knew it would speak volumes about what was going on in that moment right there and over the past few days in Baton Rouge” (Bachman 2016). The question, of course, is what is it about the photograph that suggests it speak volumes?

In the long history of Western image making, many have suggested that image-makers create, and audiences interpret, images along the lines of similar things they have seen before. Broadened to photography, we might state that photographers and editors gravitate towards instances that look like things they have seen before. Apollonius of Tyana discussed the “imitative faculty”: we project comprehensible interpretations onto imagery, such as clouds, because we try to use familiar items to parse the unfamiliar (Philostratus [c 225] 2005, pp. 181–85). Edgar Wind (Wind [1930] 1983, p. 24) stated succinctly that “every act of seeing is conditioned by our circumstances”. Those trained in the history of art are used to examining connections between images, taking it as axiomatic that pictures influence one another. Tracking meaningful connections in the history of art—be they gestural or thematic in nature—often falls under the rubric of iconography. In addition, while it is not a given that photographs echo past image-making patterns, or that viewers interpret photographs iconographically, the methodology provides a structure for investigating possible connections.

3. What Is Iconography?

Iconography is a method for examining, categorizing, and interpreting imagery. It has been most thoroughly employed in the investigation of works from both the Italian and Northern Renaissance (Warburg [1912] 1999; Panofsky [1953] 1971, [1955] 1982), but variations of it have been used in archaeological contexts (Roller 1999) and, arguably, in Hariman and Lucaites’ aforementioned study of 20th-century iconic photography. The most well-known formulation of the method comes from the art historian Erwin Panofsky.6 He divided it into three parts:

- Pre-iconographic description. The most fundamental step, identifying the components in a picture. It is “the sphere of practical experience”, augmented by research when elements of the picture are unfamiliar (Panofsky [1955] 1982, p. 33).

- Iconographical analysis. Here, one uses the stuff of pre-iconographic description to identify symbolic elements such as personifications, allegories, symbols, attributes, and emblems inherent in the artifact. It is necessary to consult materials outside of the picture or sculpture (including books, myths, and standard representational practices for the subject) to make sense of these elements.

- Iconological interpretation. This is “iconology turned interpretative” (Panofsky [1955] 1982, p. 31), wherein one synthesizes the materials collected from the iconographical analysis with knowledge of the period in which the picture was created. In order to check the sanity of one’s interpretation, Panofsky enjoined the iconographer to hew to the “general and essential tendencies of the human mind” (Panofsky [1955] 1982, p. 39).

Elements of iconography have been remarkably influential, for pre-iconographic description and iconographical analysis can help one follow the development and spread of imagery across space and time. Its value continues today. For example, reflect upon any number of political cartoons that employ the Statue of Liberty or Uncle Sam. We identify these figures through their attributes, and understand their presence in the cartoon via their symbolic associations: each performs didactic roles, in effect telling the viewer that the figure is emblematic of the United States, and that therefore whatever happens to the symbol is happening to the country.

Acknowledging the Limitations and Addressing Them

The solidity of the methodology breaks down, however, when one comes to iconological interpretation, and many criticisms have been leveled at it.7 As formulated, it treats symbolic content as having clearly-defined meanings when this is often not the case.8 Iconological interpretations have been pursued as secret codes that unlock some fixed, erudite meaning.9 And surviving contemporary accounts of pictorial content often concentrate upon affective responses instead to, e.g., the sweet and chaste appearance of the Virgin Mary in a painting, and not upon any didactic program (Marrow 1986).10 There are direct parallels for the study of imagery on social media: affective responses are common, but references to iconographic resonances less so.

This seems to provide support for constructing a new form of iconology, borrowing from Aby Warburg and Jan Białostocki. Warburg placed emphasis upon the “charge” of affective gestural formulas (Pathosformeln) and their impact upon artists and viewers.11 Warburg saw these gestural types as periodically recurring in an “afterlife” or “survival”. Compositions and gestures were reused in radically different contexts and meanings, e.g., a defensive gesture used in antique sculpture is retooled as a gesture of victory in the Renaissance (Warburg [1905] 1999). Białostocki (1965) also proposed a looser iconographical categorization based upon “encompassing themes” such as the ruler, the sacrifice, motherhood, and the like, all of which were incorporated into gestures and poses. This modified approach recognizes the fact that gestures often cross into different iconographic subjects and contexts.12

It might be more useful to bifurcate Panofsky’s iconological interpretation between an “iconographical interpretation” and an “iconological interpretation”. The former would be oriented around the artist’s intention (if discernible). The latter, in contrast, would ask cultural and historical questions, which are perhaps more the domain of the specialist: “why has a certain work of art arisen in a particular way? How can it be explained in the context of its cultural, social, and historical backgrounds; and how can the possible hidden meanings that were not explicitly intended by the artist be brought to light?” (Van Straten 1985, p. 18). A revised iconological interpretation thus provides an independent space both to examine the effect of gesture and recurrent themes, and address viewers’ interpretations of art as vital clues for the reconstruction of cultural resonance.

Nevertheless, problems remain. Within the broader history of image making, we are still left with patchy evidence linking specific commentary to specific images. We are also hobbled in evaluating responses to images, given the lack of direct connections between text and picture. In addition, perhaps because of these breaks in the evidence, the iconographer’s approach privileges the iconographer’s conclusions: we rarely hear the voices of those who made pictures, commissioned them, or looked at them, because records of those voices have rarely survived.

4. Pursuing Iconography of Social Media

This is where social media presents opportunities unavailable to art historians: images are frequently presented with interpretative commentary alongside them. On Twitter for example, a user shares a picture; indeed, they frequently share a gallery of pictures, comparing and contrasting them. Comments almost invariably accompany these pictures. Individually, these comments may be inchoate, but in aggregate they can teach us a lot: the iconographer here follows a form of discourse analysis, of “talk and text in context” (Van Dijck 1997, p. 3). Here, however, the discourse is between the author of the tweet, the event that motivated the tweet, and the picture appended to the tweet. By taking comments seriously as part of a complex relationship with pictures, we make the first steps in taking greater advantage of the information afforded us by the collection of social media data.

The rich potential of analyzing imagery, text, and data together is rarely explored in social media research. Studies frequently focus upon the purely textual response to photographs to the detriment of the pictures they share, for example in the spontaneous formation of ad hoc publics that arise from their distribution online (Mortensen and Trenz 2016). An alternative, and equally rich, form of analysis is to focus upon the “visual rhetoric” employed in photographs and memes; however, these are conducted with little recourse to social media users’ responses, whether in terms of accompanying commentary or metrics that suggest the comparative resonance of some pictures over others (Huntington 2016; Milner 2016). A more integrated approach examining both text and image in a data context is only just emerging (Bruns and Hanusch 2017). An updated iconographic approach follows this, employing user responses and their clues to explore, as it were, the mechanics of resonance working through a loose chain of antecedent imagery.

The intersection between initial photograph, comments about it, and response pictures all reveal patterns wherein people articulate their understanding of imagery. They echo Warburg’s emphasis upon gesture and affect. They point to other visual examples, indicating the resonances they have felt from pictorial antecedents. Their interpretations are polyvalent: different people shared Bachman’s photograph, yet assigned different interpretations to it. The result is relevant to methodological questions relating to the study of imagery of social media, but also to the permutation of images over time, a classic iconographic question.

4.1. Practicalities

Social media texts—in this instance, 140-character-long tweets—may be individually brief, but collectively their volume may prove daunting. Collecting and processing the data is a multi-step process involving a number of computer applications. The Evans data was collected into a basic spreadsheet via Pulsar Platform, web-based commercial social analytics software that has the ability to collect keyword- and hashtag-based content across various social media platforms, blogs, forums, and news sources (Benello 2017a, 2017b). Individual tweet URLs were extracted into a text-file and processed in a beta version of Webometric Analyst, specialized software that can download copies of the tweet and accompanying image files to a computer (Thelwall 2014, pp. 103ff). The original spreadsheet and downloaded data were then merged, and image files accompanying individual tweets were manually appended to it. Image files were identified individually and the contents of tweets were parsed manually according to recurrent thematic patterns.

4.1.1. Organizing Pictures for Analysis

There then follows several stages of manual analysis. The first stage identifies the authors of different pictures, where necessary identifying the creators through a reverse image search on Google Images. Pictures are then analyzed for their content, e.g., the number of appearances of the U.S. Statue of Liberty, or the tanks from Tiananmen Square. Each tweet record also contains a textual description of the appended picture[s] in order to perform future searches of the spreadsheet.

Twitter users also often share multiple pictures in galleries of up to four pictures.13 The intentions of users when presenting galleries seem to vary. Some present multiple renditions of the scene, for instance comparing Bachman’s photographs with Becherer’s. Others presented multiple artistic interpretations of the event, seemingly pointing to a broader recognition of the photograph’s iconicity by image-makers. Yet others paired Bachman’s photograph with artistic variations, either to anchor the artistic interpretation to its source material or to show the original photograph and an interpretation with which they presumably agree. Still others paired Bachman’s photograph with other photographs—be they iconic, such as an image of Tank Man in Tiananmen Square (1989) or historically resonant, such as Dr. Martin Luther King being arrested in a Civil Rights demonstration—again seemingly to underscore the nature of the photograph’s iconicity, and the continuation of acts of civil disobedience. Indeed, a number of users indicated their belief that the photograph will be one replicated in history books.

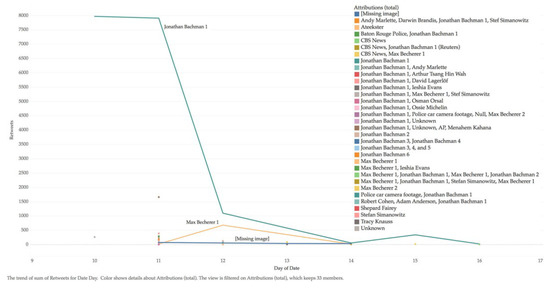

However, people did not merely share original photographs: they also shared derivative imagery, i.e., response imagery based upon the original photograph. The spreadsheet outlined above is less useful for querying these: few artistic responses were shared sufficiently widely. For instance, for the top 133 most widely shared posts of Evans—which reaches down to the level of nine retweets—the vast majority of posts share Bachman’s photographs (Figure 3), with only Becherer’s variant coming a distant second. Only four of the 133 tweets contain artistic interpretations of Evans. This power law distribution is a common feature of viral events: many people share and repost a few tweets—forming the bulk of the sharing—while there is a long tail of tweets that appear briefly and are barely reposted at all (Nahon and Hemsley 2013).

Figure 3.

Sharing images of Ieshia Evans over the period 9–16 July 2016, demonstrating the utter dominance of Jonathan Bachman’s photograph in the dataset. Chart developed in Tableau.

This does not mean that these less widely shared pictures, situated far down in the list of posted tweets, are unworthy of interest: far from it. However, to study them, the researcher will have to pick through all the collected pictures to find them. In this dataset, there are over 50 variations (see Section 5.2 below).

4.1.2. The Importance of Textual Commentary

Because the vast majority of sharing focused upon Bachman’s photograph, concentrating exclusively upon the small variety of pictures omits a lot of evidence: namely, the wide variety of comments people make about the pictures they share. This textual commentary is analyzed as further evidence of iconographic resonances.

Tweets are broken into separate themes and listed in the spreadsheet.14 For instance, any time an author refers to the police in the picture as “Robocops”, “army”, or “armor”, that tweet is tagged as “armored police”. Iterations of similar comments can be aggregated to achieve a better understanding for the similarities (and differences) of different users’ comments about a given picture, and to see what other terms they use in common. For instance, the most common theme accompanying Bachman’s photograph emphasizes and individuates Evans as a person and not a symbol. They introduced her with terms such as “Her name is”, “Say her name”, or “This is”; it is often coupled with the authors noting that Evans is both a mother and a nurse, thus highlighting her roles of familial duty and professional care—i.e., an ordinary person doing something extraordinary in the face of armored police. On the face of it, these interpretations resist iconographic readings.

However, Evans’ role in Bachman’s photograph was also described in symbolic terms: she is a positive symbol of black identity (“She represents what it means to be unapologetically black”), and the term is often accompanied by themes of defiance, strength, and connection to the Civil Rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s.

5. Iconographies of the Arrest of Ieshia Evans

Iconographic readings of the Evans photograph are therefore derived from pictures and text. It is necessary to familiarize ourselves with both.

5.1. The Textual Evidence

It should be emphasized again that much textual evidence does not allow for iconographic readings. By individuating Evans as a mother and a nurse, they appear to echo Sontag’s belief that the picture cannot be symbolic.

That said, many users clearly drew comparisons to other imagery and saw symbolic elements in the photograph. The police are described as the aforementioned “Robocops” or storm troopers (from the Star Wars films): images of faceless, oppressive armored forces, and tellingly, both from cinema. Despite all their armor, the police “fear her strength”; facing them, Evans wears only a sundress, but the author rhetorically asks, “tell me who looks stronger”.

In contrast, Evans is not only beautiful and defiant, she “is beauty” and “is defiance” (emphasis mine), i.e., she is the personification of those traits. She is the “living, breathing Statue of Liberty”, and is described as a “Queen”, a “Goddess”, a “superhero”, and “Wonder Woman”, as having a “strength that lives”. She “captures the spirit” of the BLM movement. All these descriptions confer extraordinary powers upon her.

5.2. Pictorial Evidence

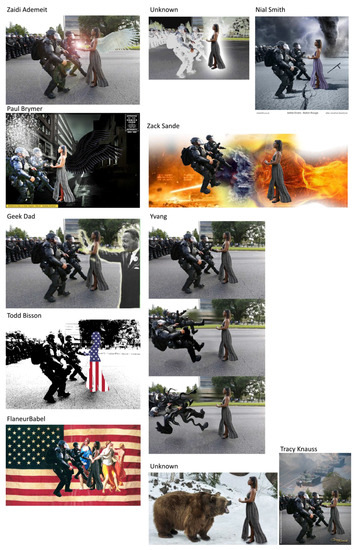

Of the 966 pictures in the full dataset, there are 56 separate artistic interpretations of Ieshia Evans’ arrest. Some of these mediations have been shared multiple times, but the majority were only shared once. All but two were-based upon Bachman’s photograph. They can be separated into the following five forms:

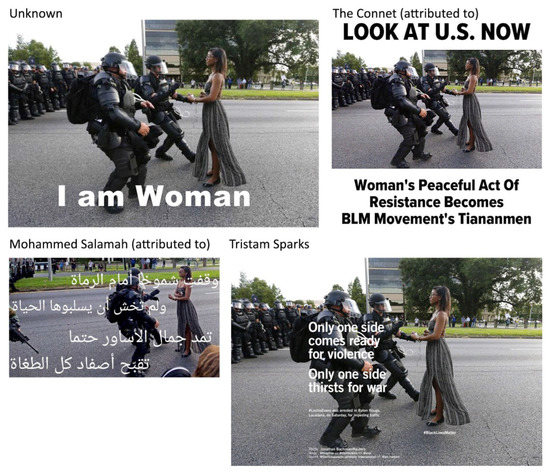

Textual overlays: Perhaps the simplest of mediations, the image-maker places text atop the photograph (Figure 4).15 There are four examples of this in the dataset.

Figure 4.

Textual overlays. Source: Twitter.

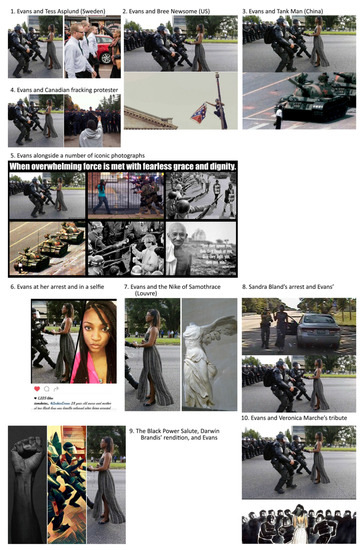

Pictorial comparisons: The image-maker has juxtaposed two or more picture files together for the sake of comparison (Figure 5). There are ten of these merges, the majority of which compare Bachman’s photograph with other notable pictures. In effect, these pictorial merges duplicate the gallery presentations in Twitter, the number of which dwarfs these. She is frequently compared with the “Tank Man” from Tiananmen Square. Apart from comparing the pictures in Figure 4, users compared Evans’ nonviolent resistance to that of Gloria Richardson Dandridge during the original Civil Rights struggle. Users also connected Evans to contemporary struggles against racism, notably to Bree Newsome, the woman who removed the Confederate Flag from Charleston, South Carolina, and Tess Asplund, who defied neo-Nazi marchers in Sweden (Kisseloff 2007; Contrera 2015; Crouch 2016).

Figure 5.

Pictorial comparisons. Source: Twitter.

Filtered mediations: Bachman’s picture of Evans has been passed through one or more digital filters (Figure 6). These include filters such as those found in Instagram that brighten, increase the contrast, or warm color tones. Other users appear to use mobile applications such as Snapchat to add elements such as Peace symbols, or other applications such as Prisma or Visionn or create more ethereal versions. Still others appear to use Photoshop filters to manipulate the threshold or posterize the photograph for dramatic effect. There are eighteen filter-based variations in the dataset.

Figure 6.

Filter-based mediations. Source: Twitter.

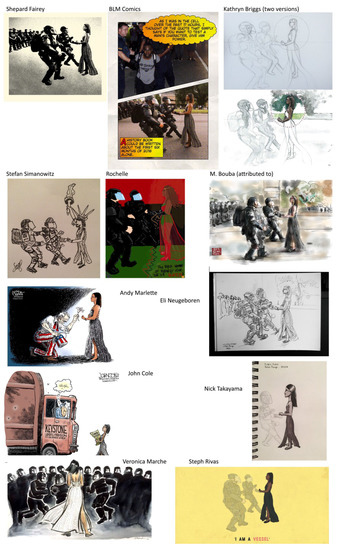

Artistic mediations: These fourteen examples required more significant reworking of the source material in order to create the final image (Figure 7). Some are by professionals such as Shepard Fairey while others are by enthusiastic amateurs. In these, Evans is converted into (and identified as) a goddess and as the Statue of Liberty; Uncle Sam kneels to her. She is pressed into service for other contemporary debates (Keystone). Veronica Marche entirely reimagines the scene. BLM Comics uses the Comic Life application to contrast Bachman’s photograph with one of organizer DeRay McKesson’s arrest at the same protest: the very format casts the protagonists as heroes.

Figure 7.

Artistic mediations. Source: Twitter.

Photoshop-style manipulations: These mediations used Adobe Photoshop to alter Bachman’s photograph significantly (Figure 8). The majority of these take heed of the odd stance of the police by ascribing supernatural power to Evans. There are eleven manipulations in the dataset.

Figure 8.

Photoshop-style manipulations. Source: Twitter.

5.3. Visual Theme: Extraordinary Power

Most of the Photoshop manipulations work upon the contrast between the peculiar posture of the police and Evans’ calm, as if providing an underlying cause for these features. Both Zaidi Ademeit and Paul Brymer gave Evans wings—in effect, acknowledging the visual support provided by the tree branch behind her in the original photograph even when the background has been removed. Brymer makes his associations explicit with a text-box that states “America has a new superhero! Ieshia Evans!” (Figure 9). The comics code approval of authority stamp adds to the comic book look-and-feel, but it also adds a subtle moral element, as the introduction of that stamp was intimately connected to the teaching of public morality in the medium (Hajdu [2008] 2009).

Figure 9.

Ieshia Evans, superhero (2016). By Paul Brymer. Picture courtesy of the artist.

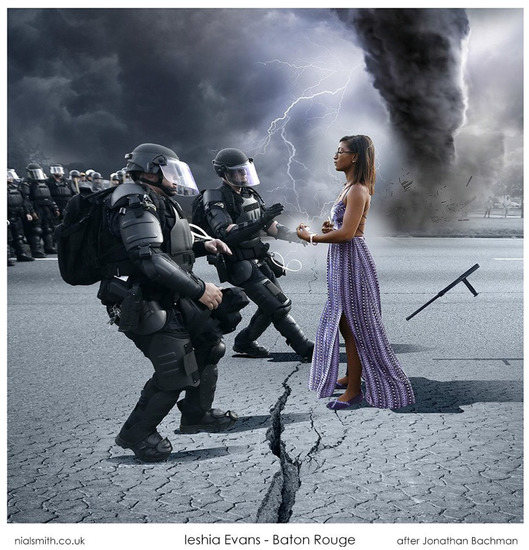

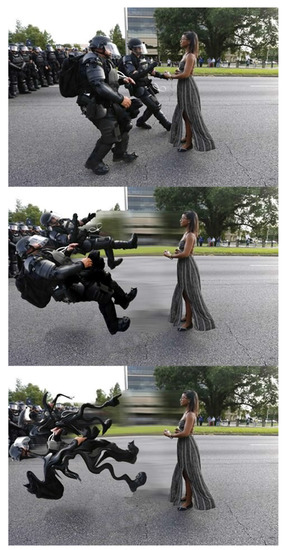

In addition, these artists place great emphasis on the moment that the police seemingly touch Evans. Ademeit places a lens flare between Evans and the police to highlight the defining moment, while Brymer adds sparkles that emanate from Evans’ hand and cover the police, seeming to freeze them. Nial Smith (Figure 10) adds a tornado and lightning surrounding Evans, the lightning striking and repulsing the police as they touch her: the very ground cracks between them, Smith being the only one to highlight the role that the pavement’s cracks play in the creation of depth in an otherwise planar composition. Zack Sande places imagery of explosions in the background in order to explain the seeming repulsion (Figure 11). Geek Dad places a ghostly Dr. Martin Luther King in the picture, his hand providing the supernatural power causing the repulsion. In addition, Yvang creates a three-part narrative, whereby the touch causes the police to fly back and deflate (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Ieshia Evans, supernatural being (2016). By Nial Smith. Picture courtesy of the artist.

Figure 11.

The supernatural effect of touching Evans (2016). By Zack Sande. Picture courtesy of the artist.

Figure 12.

The police repulsed and deflated (2016). By Yvang. Picture courtesy of the artist.

None of these interpretations are random. The image-makers acknowledge and highlight formal properties in the photograph. Their usage of these properties, however, points back to other, older imagery and reinforces the textual comments made by Twitter users.

5.4. The Chain of Antecedents

The purpose of iconological interpretation in examining both the photograph and the responses social users made to them is to see how a specific compositional formula accretes into a recurring encompassing theme to the point that the theme feels not only familiar, but natural.

Twitter users often likened Evans and the police to superheroes and villains, often figures from films or comics; they concentrate upon the power relationship between the figures. The cinematic comparison is particularly telling. In a medium that frequently depicts depth recession, it is notable that conventions depicting confrontation between two characters employ a planar composition: the “two-shot” parallel to the screen, familiar to any movie-goer in which antagonists square off against one another, viewable in popular films such as Avengers (2012),16 Star Wars (1977),17 and classic films such as Yojimbo (1960)18 (Bordwell and Thompson [1996] 2013, p. 251; Brown [2002] 2016, p. 63). This convention is enforced in other media besides, such as comic books, which by their nature are completely unconstrained by technical limitations of the camera angle, since they have none.19

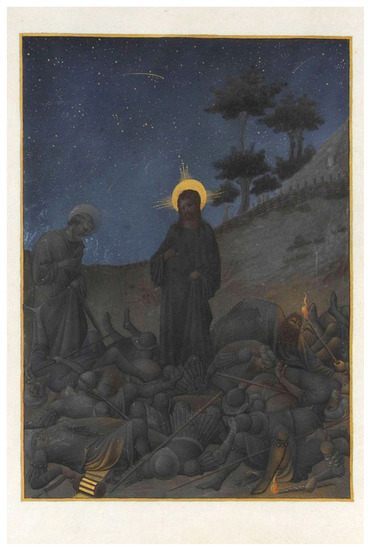

These in turn have their own formal antecedents, however, and thematically they cleave more closely to the spirit of Bachman’s photograph, i.e., to the confrontation of moral and coercive authority.20 The arrest of Evans shares strong thematic and formal parallels with images of the Arrest of Christ.21 This event is commonly represented with Jesus’ arrest at the hands of armed soldiers in the garden of Gethsemane, frequently at the moment when Judas betrays Jesus with a kiss: Giotto’s Arrest of Christ (Figure 13) and Caravaggio’s Betrayal of Christ (Figure 14) are representative of this. This theme almost invariably portrays Christ calmly standing in a shallow plane amid a roiling storm of armed adversaries. His hands are held out, already bound or waiting to be bound, suggesting passive acceptance of his fate. A rare variant, famously portrayed by the Limbourg brothers (Figure 15) depicts the moment directly following, when Christ identifies himself and the soldiers fall to the ground (John 18:6). Uncannily, Bachman’s photograph—highlighted by many of the Photoshop-manipulated responses—evokes the liminal point between these two Biblical scenes: the awkward stance of the police suggests their imminent collapse to the ground.

Figure 13.

Arrest of Christ (c. 1304–06). By Giotto. Arena Chapel, Padua. Photograph from Wikimedia and flagged for noncommercial use.

Figure 14.

Betrayal of Christ (c. 1602). By Caravaggio. National Gallery of Art, Dublin. Photograph from Wikimedia and flagged for noncommercial use.

Figure 15.

Arrest of Christ, from the Très riches heures de Jean, duc de Berri (before 1416). By the Limbourg Brothers. Musée de Chantilly MS65, fol. 142v. Photograph from Wikimedia and flagged for noncommercial use.

Each of these examples—the Arrest of Christ, two-shot scenes in cinema, and comic book covers—are links in a chain of antecedents. Each link in the chain influences those near it. But of course, none of this is to claim that Bachman consciously modeled his photograph after old representations of antagonistic encounter, nor is it to denigrate his skill as a photographer. It is certainly not to mitigate the extraordinary bravery of Evans in the face of aggression, particularly when the police have used deadly force with impunity. Finally, it is not to suggest that viewers had works of art in mind when they described what they saw in Bachman’s photograph. It is rather to understand the mechanisms of resonance: to understand why users responded more to Bachman’s photograph than to Becherer’s, and indeed, why Bachman himself knew it would “speak volumes”.

6. Looking Forward, Looking Back

There is no iconographic stopping point for iconic imagery: they inflect future examples by their existence. Well after the end of data collection, the image of the arrest of Evans has kept popping up. Aby Warburg wrote of the Nachleben der Antike, or the “survival” of imagery from the Greco-Roman world. By this he meant the survival and reuse of emotive formulas, not their mere repetition. They can spring forth anew. Similarly, as Nahon and Hemsley (2013) observed, viral events—and the sharing of Bachman’s photograph certainly counts as a viral event—can be reactivated in the public’s consciousness when the context dovetails into the wider perception of that viral event. This constitutes no less than the afterlife not of images in general, but the afterlife of a particular photograph.

In the middle of August, a French “naïf noir” artist working under the name Mina Mond previewed a piece inspired by Bachman’s photograph. By the end of the month, Mond had finished the triptych Am I Not A (Wo)Man?, placing the image of Evans within the United States’ traumatic history of race relations, from slavery to the killings highlighted by the BLM movement (Figure 16). Mond has adopted a syncretic mixture of attributes and symbols gleaned from sources across various cultural traditions and belief systems: Europe and the Middle East (the sun and moon) and Louisiana/Haiti/Sub-Saharan West Africa (the skeletal figures), to name but a few. Mond has added her own symbolic elements to the mix: the tormentors of all the figures are now American eagles. In the center, they are symbolic referents to the police, and by their repetition in the other panels, to all the agents of the pernicious racism that has plagued the United States since before its independence. She described the work thus:

The left panel recalls slavery. The white snake (found throughout the three panels) was a Confederate symbol against the abolition of slavery. The skeletal figures with raised arms are inspired by African statuary honoring ancestors, and their placement in the work references the Black Lives Matter Movement. The central panel is a direct reference to Ieshia Evans, who became a symbol for both the struggle for civil rights against police violence in spite of herself. The right panel is an homage to Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and all those who have died for no good reason. The main figure wears a mask (derived from funerary masks) because he has no precise identity: a phantom, he symbolizes the spirit of those killed. I won’t explain everything, as I would prefer the viewer to weave it together.(Mond 2016)

Figure 16.

Am I not a (wo)man? (2016). By Mina Mond. Picture courtesy of the artist.

Evans had previously been linked to representations of confrontation that reaches back at least as far as the Arrest of Christ and through cinematic confrontations, and now, through Mond, to the on-going struggle of people in their confrontation with a violent state apparatus. Mond’s title evokes Wedgwood’s anti-slavery slogan, updated to focus upon Evans and her centrality of a woman in the photographed event. That inflection echoes Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech: Truth emphasized the scantly-recognized strength of women in the struggle for racial equality. This was recognized immediately by a number of Twitter commentators, who noted that African-American women were always in the front lines of the Civil Rights struggle.

In Mond’s triptych, we therefore see a motif migrating back, from painting to photograph to painting; from a religious subject of cosmic importance, to the recording of a fraction of a second containing deep resonance, and back to an image containing historical evocations. This is a true migration of images, which are “always reappropriated, and thus metamorphosed, in the constantly changing course of their survivals and their renaissances” (Didi-Huberman [2002] 2016, p. 93).

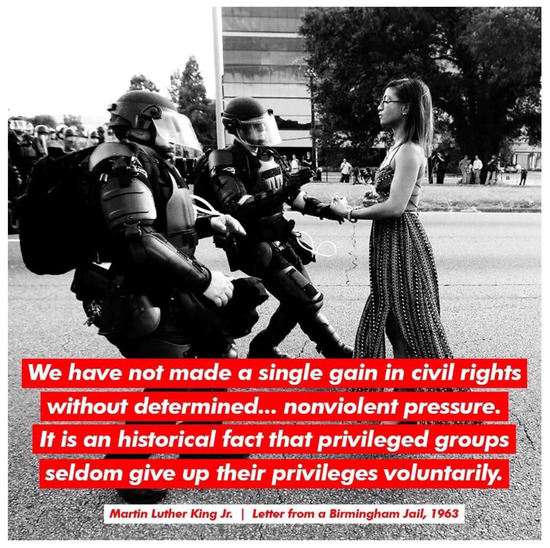

In a prominent example commemorating the Dr. Martin Luther King holiday on 16 January 2017, photographer and graphic artist Daniel Rarela paired Bachman’s photograph with a quotation from King about the importance of nonviolent protest. By framing his piece (Figure 17) in the visual language of Barbara Kruger’s work—stark black and white photograph, with bands of brilliant red crossing it, text set in the Futura font—Rarela inflected the image with the political, indeed revolutionary power of both King’s words and Evans’ peaceful protest. Having been evoked in the arrest of Evans, the theme of nonviolent or passive confrontation undergoes another transformation, curling back to the Civil Rights struggle of the 1960s and the graphically confrontational power of 1980s art. The photograph will, in turn, impact future evocations of the theme.

Figure 17.

We have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined… nonviolent pressure. By Daniel Rarela (2017). Picture courtesy of the artist.

The migration of images does not follow a pre-ordained, unobstructed path: fundamentally rhizomatic, it is “always in the middle, between things, interbeing, intermezzo“ (Deleuze and Guattari [1980] 2013, p. 26). The instantiation of any particular theme inflects its usage and influences future instantiations. Warburg recognized this process long ago. It continues on social media platforms, where we see a continuous dance of encounter, interpretation, and re-situation of imagery, coiled around each other and, though more distant, the broader history of image-making. Through an examination of the data afforded to us by social media, we can glean new, more granular observations about the myriad ways resonance plays out in contemporary culture.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank An Xiao Mina, with whom I penned a brief online article that inspired this analysis (Mina and Drainville 2016). I would also like to thank Anne Burns and Jennifer Saul for their many editorial and theoretical insight, and to Pulsar Platform, which kindly provided the funds to cover the collection of the dataset for this paper. Finally, many thanks to Simon Faulkner, Farida Vis, and Jim Aulich, who read an early draft of this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The dataset sponsors had no role in the design of the study, in its analysis or interpretation; in the writing of the manuscript, or in any decision to publish the results.

References

- Arasse, Daniel. 2012. Take a Closer Look. Translated by Alyson Waters. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, Jonathan. 2016. Taking a stand in Baton Rouge. Reuters. Available online: https://widerimage.reuters.com/story/taking-a-stand-in-baton-rouge (accessed on 16 January 2017).

- Bann, Stephen. 1998. Meaning/Interpretation. In The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology. Edited by David Preziosi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 256–70. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 2000. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. London: Vintage. First published 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Benello, Sophie. 2017a. What Data Sources or Channels are Supported on Pulsar? Pulsar. Available online: https://intercom.help/pulsar/pulsar-general-faqs/what-data-sources-or-channels-are-supported-on-pulsar (accessed on 19 April 2017).

- Benello, Sophie. 2017b. What is Pulsar TRAC? Pulsar. Available online: https://intercom.help/pulsar/pulsar-trac/what-is-pulsar-trac (accessed on 19 April 2017).

- Białostocki, Jan. 1965. Die ‘Rahmenthemen’ und die archetypischen Bilder. In Stil und Ikonographie: Studien zur Kunstwissenschaft. Köln: DuMont, pp. 144–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. 2013. Film Art: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Blain. 2016. Cinematography: Theory and Practice. Imagemaking for Cinematographers and Directors. London: Routledge. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Axel, and Folker Hanusch. 2017. Conflict Imagery in a Connective Environment: Audiovisual Content on Twitter Following the 2015/2016 Terror Attacks in Paris and Brussels. Media, Culture & Society 39: 1122–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Lorne, and Jan Van der Stock. 2009. Rogier van der Weyden 1400–1464: Master of Passions. Zwolle: Waanders. [Google Scholar]

- Contrera, Jessica. 2015. Who is Bree Newsome? Why the Woman Who Took Down the Confederate Flag Became an Activist. Washington Post. June 28. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2015/06/28/who-is-bree-newsome-why-the-woman-who-took-down-the-confederate-flag-became-an-activist/ (accessed on 13 June 2017).

- Crouch, David. 2016. Woman Who Defied 300 Neo-Nazis at Swedish Rally Speaks of Anger. The Guardian. May 4. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/04/woman-defied-neo-nazis-sweden-tess-asplund-viral-photograph (accessed on 15 June 2017).

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2013. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. 2 vols.London: Bloomsbury, vol. 2. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2005. Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. Translated by John Goodman. Philadelphia: Penn State University Press. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2016. The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms: Aby Warburg's History of Art. Translated by Harvey Mendelsohn. Philadelphia: Penn State Press. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, William A., and Andre Modigliani. 1989. Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombrich, Ernst. 1978. Introduction: Aims and Limits of Iconology. In Symbolic Images: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance II. London: Phaidon, pp. 1–25. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu, David. 2009. The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How it Changed America. New York: Picador. First published 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. 2007. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hariman, Robert, and John Louis Lucaites. 2016. The Public Image: Photography and Civic Spectatorship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Heidi. 2016. Pepper Spray Cop and the American Dream: Using Synecdoche and Metaphor to Unlock Internet Memes’ Visual Political Rhetoric. Communication Studies 67: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilsink, Matthijs, Jos Koldeweij, Ron Spronk, and Luuk Hoogstede. 2016. Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Catalogue Raisonée. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ince, Jelani, Fabio Rojas, and Clayton A. Davis. 2016. The Social Media Response to Black Lives Matter: How Twitter Users Interact with Black Lives Matter through Hashtag Use. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 1814–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisseloff, Jeff. 2007. Generation on Fire: Voice of Protest from the 1960s: An Oral History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. London: Sage. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lebron, Christopher J. 2017. The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linfield, Susie. 2012. The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marrow, James. 1986. Symbol and Meaning in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Renaissance. Simiolus 16: 150–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, Philippe-Alain. 2004. Aby Warburg and the Image in Motion. Translated by Sophie Hawkes. New York: Zone Books. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Ryan. 2016. The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mina, An Xiao, and Raymond Drainville. 2016. An Art Historical Perspective on the Baton Rouge Protest Photo that Went Viral. Available online: http://hyperallergic.com/311570/an-art-historical-perspective-on-the-baton-rouge-protest-photo-that-went-viral/ (accessed on 15 July 2016).

- Mitchell, W. J. Thomas. 2005. What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mond, Mina. 2016. Triptypque: Am I Not A (Wo)Man? Available online: http://www.minamond.com/search/label/leshia evans/ (accessed on 23 May 2017).

- Mortensen, Mette, and Hans-Jörg Trenz. 2016. Media Morality and Visual Icons in the Age of Social Media: Alan Kurdi and the Emergence of an Impromptu Public of Moral Spectatorship. Javnost—The Public 23: 343–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxey, Keith. 1993. The Politics of Iconology. In Iconography at the Crossroads: Papers from the Colloquium Sponsored by the Index of Christian Art, Princeton University, 23–24 March 1990. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nahon, Karine, and Jeff Hemsley. 2013. Going Viral. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 2012. On the Problem of Describing and Interpreting Works of the Visual Arts. Critical Inquiry 38: 467–82. First published 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1972. Introductory. In Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York and London: Harper and Row, pp. 3–31. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1971. Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. 2 vols.New York: Icon. First published 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1982. Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art. In Meaning in the Visual Arts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 26–54. First published 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Philostratus. 2005. Life of Apollonius of Tyana. Edited by Christopher P. Jones. 2 vols.Cambridge: Harvard, vol. 1. First published c 225. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, Lynn E. 1999. In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Sanjay. 2013. Black Twitter? Racial Hashtags, Networks and Contagion. New Formations 78: 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, Susan. 1979. On Photography. London: Penguin. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Paul. 1995. Dutch Flower Painting: 1600–1720. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thelwall, Mike. 2014. Big Data and Social Web Research Methods. Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton, Available online: http://www.scit.wlv.ac.uk/~cm1993/papers/IntroductionToWebometricsAndSocialWebAnalysis.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2017).

- Van Dijck, Teun. 1997. The Study of Discourse. In Discourse as Structures and Processes. Edited by Teun Van Dijck. London: Sage, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Van Straten, Roelof. 1985. An Introduction to Iconography. Translated by Patricia de Man. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1991. The Lives of the Artists. Translated by Julia Conaway Bondanella, and Peter Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published 1549. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby. 1999. Dürer and Italian Antiquity. In The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: Contributions to the Cultural History of the European Renaissance. Translated by David Britt. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, pp. 554–58. First published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby. 1999. Italian Art and International Astrology in the Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara. In The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: Contributions to the Cultural History of the European Renaissance. Translated by David Britt. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, pp. 563–92. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, Edgar. 1983. Warburg’s Concept of Kulturwissenschaft and its Meaning for Aesthetics. In The Eloquence of Symbols: Studies in Humanist Art. Edited by Jaynie Anderson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 21–35. First published 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Wind, Edgar. 1937. The Maenad under the Cross. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 1: 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2010. About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zittrain, Jonathan, Kendra Albert, and Lawrence Lessig. 2013. Perma: Scoping and Addressing the Problem of Link and Reference Rot in Legal Citations. Harvard Public Law Review Forum 127: 165–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The full series may be viewed online per Bachman (2016). Bachman was perpendicular to Evans at the moment of arrest. Becherer was positioned obliquely to Evans and to the left of Bachman, behind the pair of policemen. |

| 2 | Becherer’s photograph (Figure 2), taken at virtually the same instant, suggests instead that the police have not yet in fact laid hands upon Evans, and that this touch is an illusion based upon Bachman’s viewpoint. |

| 3 | Materials for this essay are drawn from Twitter data collected by social media analytics company Pulsar covering the period between 9 and 13 July 2016. The criteria for collection were the use of the terms: “Ieshia Evans”, “Ieshiaevans”, “Leshia Evans”, and “Leshiaevans” (Evans was misidentified by some users as Leshia, so this erroneous name is necessary to cover the subject). This data amounted to 5628 tweets in total and 966 shared pictures, the vast majority of which were Bachman’s photograph (Figure 3). This essay focuses upon the text of the 133 most shared tweets (containing 165 pictures in total) and upon all the artistic response pictures that were based upon the arrest of Evans (56 pictures). The most-shared tweets were all positively disposed towards Evans. Negative interpretations exist via different search terms and in replies to individual tweets: but they, too, use different phrases other than the search terms above, and so were not captured in this dataset. A note on ethics: Twitter users may broadcast their opinions in a public social media space, but this does not mean that they expect their opinions to be reproduced outside of that space. In order to protect users’ privacy, this essay will only summarize comments from private individuals; any comments from public individuals present in the dataset will be quoted in full. This includes artists who presented their own work; where possible, I have identified the image maker. |

| 4 | The titles to these photographs are not the original captions but are rather the titles subsequently given them as they have become cultural touchstones. |

| 5 | Notable exceptions include Madonna and Pietà-style imagery in Lange’s Migrant Mother (Hariman and Lucaites 2007, pp. 56–57) and the conventions of portrait photography inherent in a photograph of a bird suffocating in an oil slick (Hariman and Lucaites 2016, p. 85). |

| 6 | Evidently not content with his formulation of the methodology, Panofsky pursued several iterations of it over the course of two decades. He first articulated his conception of it in German; this account was only translated into English eighty years later (Panofsky [1932] 2012). He subsequently introduced the subject twice in English (Panofsky [1939] 1972; Panofsky [1955] 1982), refining his conception as he did so. The distinctions between these versions are beyond the remit of this paper; an exhaustive rendition of the differences, and the possible implications of those differences, may be found in (Didi-Huberman [1990] 2005, pp. 98ff). |

| 7 | Moxey (1993, p. 271) highlighted the single (or terminal) authoritative voice in Panofsky’s iconology. Bann (1998) noted interpretative problems when different artists used the same imagery in entirely different contexts, resulting in a tangle of contradictory meanings and associations. Arasse (Arasse [2000] 2012, p. 20) and Mitchell (2005, pp. 27–28) both claimed that Panofskian iconography flattens idiosyncrasies in individual examples by concentrating upon ostensibly similar treatments of subject matter. Similarly, Didi-Huberman (Didi-Huberman [1990] 2005, pp. 102–7) objected to the synthetic nature of Panofsky’s iconological interpretation, and more broadly questioned the very possibility of reducing a work of art to discursive interpretation. |

| 8 | See for example, Taylor (1995, pp. 28ff) on the dangers of iconographic interpretations of Dutch flower paintings. Because there is so much (often contradictory) symbolism attached to flowers, one can easily cobble together an elaborate iconographic program—with, however, little proof that anyone in the period would have “read” the painting in that way. |

| 9 | See (Gombrich [1972] 1978, pp. 18–19). There is often very little evidence linking source material to works of art, something Gombrich observed to a student many years ago (Marrow 1986, pp. 151–52). |

| 10 | Worse, we have surviving accounts for pictures that do not survive, and vice versa. A number of exceptions of surviving pictures and commentary about them are available in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (Vasari [1549] 1991): they are nevertheless rare. Other examples include Rogier Van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross and Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (Campbell and Van der Stock 2009, pp. 32ff; Ilsink et al. 2016, pp. 356ff, 578–82). |

| 11 | Michaud (Michaud [1998] 2004, p. 252) contrasted the Panofskian approach as finding meaning in figures, whilst the Warburgian approach finds meaning in the interrelationships of figures and how they are composed. Didi-Huberman (Didi-Huberman [2002] 2016, pp. 104ff) emphasizes that Warburg viewed the recurrence of Pathosformel not as an identical return to the same meaning or forms, but rather as shifting over time. |

| 12 | A classic example is the use of ecstatic maenads as models for the mourning Mary Magdalene at the foot of crucifixion scenes (Wind 1937; Didi-Huberman [2002] 2016). |

| 13 | Figure 3 contains a list of all the various gallery permutations, organized by author (where attribution could be confirmed). |

| 14 | This approach is based very loosely upon framing and content analysis, except that the texts are divided into smaller, tag-like elements (Gamson and Modigliani 1989; Entman 1993; Krippendorff [1980] 2004, pp. 280ff). |

| 15 | Licensing rights to reproduce some pictures (mainly stills from movies) have proven impossible to obtain. In these circumstances, I have used the Perma.cc service, which creates permanent links to resources on the Internet. Its purpose is to combat link rot, wherein links fail to resolve to the linked resource due either to its deletion or change of location. See (Zittrain et al. 2013) for the issues surrounding link rot and the rationale for creating Perma.cc. The makers of derivative response pictures have been identified where possible (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). Their pictures are reproduced on a small scale with specific, permitted exceptions. |

| 16 | https://perma.cc/Q66T-5UXT (Accessed 31 August 2017). |

| 17 | https://perma.cc/A9YT-T3L9 (Accessed 31 August 2017). |

| 18 | https://perma.cc/9K94-PH8U (Accessed 31 August 2017). |

| 19 | https://perma.cc/T869-5A7K (Accessed 31 August 2017). |

| 20 | It is useful to compare Bachman’s photograph with Arthur Tsang Hin Wah’s Tank Man at Tiananmen Square (1989), one made by a number of Twitter users. In contrast to Bachman’s composition, which acts out parallel to the picture plane, Wah’s subject recedes from the picture plane. Twitter users comparing the two thus concentrate upon thematic rather than compositional similarities. |

| 21 | This scene is alternately called the “Betrayal of Christ”, the “Taking of Christ”, or the “Kiss of Judas”, depending upon the precise moment being portrayed. For the source, see especially Luke 22: 47–54. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).