Abstract

In the 18th century, nations began acknowledging the presence of those who belonged to inferior classes and regarding them as the constitutive political subject of the modern state. Paradoxically, even as these marginal individuals were turned into central figures of the state’s political apparatus, they plunged the notion of sovereignty into crisis as they questioned the status quo and embodied an alternative to institutional power. In this light, the present essay explores the idea of crisis and modernity in the Spanish context from a historical, spatial, and gendered perspective. Women occupy a central space as a minority collective at the margins of the citizenry. But with their action and participation in mutinies, wars and revolutions—all landmarks of state crisis—they make themselves visible and open new spaces of agency from which to disrupt and renew traditional norms. By analyzing 18th- and 19th-century newspaper articles, literary works, and a number of visual representations by Spanish painter Francisco de Goya, this essay will examine the power of art to reveal how crises allow women to emerge as political subjects and to rewrite a narrative of modernity in which they take the leading role in propelling social change, influencing projects of political citizenship, and shaping a modern nation that needs to tend to all its members, making evident that crisis, while a break in the established order, is also a liberating step towards emancipation.

Women are more disposed to be mutinous... in all public tumults they are foremost in violence and ferocity—Thompson (1971, p. 116)

In spite of everything there have been revolutions for the better in this century... for instance, the emergence of women after centuries of repression—Montalcini (Hobsbawm 1994, p. 1)

1. Introduction

On 23 March 1766, a simple project proposed by the Marquis of Esquilache, one of the ministers of King Charles III of Spain, sought to change Spaniards’ apparel by substituting the long capes and broad-brimmed hats worn by madrileños with French-style short capes and three-cornered hats in an attempt to modernize Spain.1 But the people of Madrid, unhappy with this Enlightened reform, took to the streets, occupied the center of the city, and throughout the month of March destroyed lampposts, burned objects associated with the monarchy, and sacked mansions and churches in what would become known in history as the Esquilache Riots. The public altercations ended with the crowd gathered together in front of Palacio Real, the king’s residence in downtown Madrid, yelling a contradictory “¡Viva el Rey, muera Esquilache!” (“¡Long live the king, death to Esquilache!”).2 There was more to the riots than just a protest over fashion. A hungry and infuriated crowd saw the opportunity to take to the streets to protest against the increased cost of basic staples like bread and wheat.3 But far from challenging royal authority, the common people were demanding a voice with which to speak and be heard, the right to be seen and not ignored, and the agency with which to make decisions in the political and ideological sphere.

Nancy Fraser describes a crisis as a system of disturbance. Following this general definition, a crisis would be a time of intense difficulty, trouble, or danger in which the prevailing normality loses its validity and yields to dramatic change. In the context of our contemporary times, the term has been employed to denote a turning point or a situation of abnormality in the areas of law, medicine, politics, psychology and, above all, economics, as crises at an international level tend to be understood as a complicated situation of privation or scarcity that threatens the collapse of the economic system. In the modern definition of crisis there are parallels to the metaphorical range of meanings contained in the Greek origin of the word as “separation, dispute, judgement.” While there has been significant cultural alteration in its meaning over a period of two thousand years, the current usage of the word continues to indicate a decisive moment of rupture and interruption in which something breaks and therefore analysis and judgement are required. In this light, the Esquilache episode would come to represent a major crisis in which an uneducated population emerged as a new collective subject to break with old traditional forms of authority and to disturb the existing social, economic, and political order by opening new spaces of agency, representation and protest from which to deviate from accepted social norms. It is clear that this historical event constituted a conflictive situation of profound instability that threatened the continuity of an economic, political and cultural framework and that had a long-lasting impact in the construction of Spanish national identity, one that continues until today.

The crisis represented by the Esquilache Riots serves well to open this essay in which I aim to put in dialogue the notions of crisis and modernity from a historical, spatial, and gendered perspective. The modern dimension of this historical episode derives from the introduction of people as a political term: the class of the underprivileged that, socially marginalized and long excluded from politics, now becomes the constitutive political subject of the modern state (Agamben 2000, p. 28). In the light of modernity as a complex and long historical process characterized by the use of Reason, industrial development, and the advent of democracy, but also by the crystallization of constitutional principles, the birth of public opinion, the rupture with the old and the worship of the new, the construction of a modern nation requires the gradual inclusion in political projects of what is known as the pueblo, the common people, the plebeians: ordinary individuals who become citizens only when the State acknowledges their presence and grants them rights. But as these marginal figures start to be regarded as central in political history, they introduce a disquieting element in the order of the nation that brings the very threat of crisis with them: with their presence and action, they clear the way for a revision of traditional categories that need to be actualized for the configuration of the modern nation. Ironically enough, then, we can say that in an attempt to modernize and Europeanize Spain, the Esquilache project failed and gave way to the real modernizing processes that shape the modern state as we know it.

In this group of excluded bodies, working-class women occupy a central role as a minority collective at the margins of the citizenry. With no voice and no right to vote, they were usually relegated to the space of the home where they occupied a subordinate position. But as Diane Willen aptly notes, low-class females crossed “both the private and public spheres” (Willen 1992, p. 184), although it is important to note that when they made themselves visible in public, it was either to perform low-paid or marginalized work (such is the case of seamstresses, dressmakers or wet nurses); or to follow the orders and run the errands of their masters (for example, domestic servants or maids); or to carry out basic tasks of a domestic nature (going shopping for food and necessities of the household). However, times of crisis will encourage females to abandon the domestic space and display agency in the public sphere, which results in the reformulation of the dominant ideals of gender as a necessary step toward Spain’s integration into modernity. I understand modernity both as a historical period when processes of industrialization and urbanization opened new physical and symbolic spaces that entailed new possibilities and a leeway for action for women; and also as a more general experience of cultural habits that make up a modern and more secularized social order, one that is no longer structured around a superior authority but “predicated upon an individuated and self-conscious subjectivity”, as Rita Felski has defined the philosophical attitude that lies at the heart of modernity (Felski 1995, p. 13). Thus, in times of crisis, lower-class women enjoy a subjectivity that incorporates participation in activities and behaviors that seek to exert a political influence that, as a guarantor of a modern identity and existence as an individual of a state, allows them to rise above their status as second-class citizens.

This essay explores how moments of crisis in the modern history of Spain serve to open new spaces of representation and enunciation along with avenues of agency that give visibility to otherwise hidden and ignored marginal collectives like working-class women, whose presence and actions become central in the configuration of a modern state. Times of disturbance unveil formative processes of modern subjectivities that, undermining social norms and rebelling against normative discourses, dare to act and to make themselves visible in the urban public sphere where they demand a space of representation. By moving them out of the shadows and into the light, crises allow these emerging political subjects to rewrite a narrative of modernity in which they take the leading role and in which their inclusion and participation is essential to propel social change, influence projects of political citizenship, and shape the project of a modern nation that needs to tend to all its members.

For this purpose, and embracing the conception of art as a powerful instrument of social critique and political protest, I analyze a number of newspaper articles, literary works, and visual representations by the great Spanish artist Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) that, spawned by the conflict, bring to center stage women of the pueblo taking active part in certain critical episodes in the history of modern Spain that are considered landmarks of crisis of the state: the Esquilache Riots, the War of Independence, and the so-called mutinies of cigar makers at the end of the 19th century. These battles constitute the foundation on which the modern history of the nation was built, not only due to the leading role of the civil population—an indispensable presence in the political apparatus of the modern state as Giorgio Agamben has masterfully explained (Agamben 2000, pp. 29–36)—but also because of active female participation, a factor that represents an unprecedented feature of modernity (Aymes 2008, p. 351). This feminine presence is well represented in the cultural work by the gradual invasion of two exclusively masculine spaces: the war arena and the public space, imprecise and timeless, where armed conflicts usually take place. My analysis will reveal how the spatial rearticulation that inevitably follows times of crisis opened new possibilities for women, and how it is indeed in public spaces that we have to read modernity in the cultural production of the time, since it was generally in urban contexts where these revolts first took place. In this sense, the public sphere as theorized by Habermas as a space from which to articulate a resistance through dialogue and employing the tools of reason is thrown into crisis. The public sphere as the site of women’s displays and participation in crisis will certainly have all the hallmarks of resistance, but it will be characterized by disorder, chaos and a dangerous transgression of social norms, all of which are usually associated with the lower classes and all of which come to support the idea of the modern state.

Female participation was fundamental in catalyzing the decline of the Ancien Régime and in propelling a political, cultural and economic evolution that paved the way for Spain’s transition to a liberal state in a process that came to be known precisely as a “crisis of modernity” (Jiménez Moreno 1993, p. 94). The spatial occupation of the public war arena through which women set out to emerge as active participants at the same level as men advances the idea of progress, which is inseparable from the threatening presence that conceals the reality of crisis inasmuch as these resistant subjectivities disrupt the status quo and act as a resisting force in politics. By abandoning the home and actively participating in riots, women shake the sexist, patriarchal, and traditional society to its core, introducing another level of crisis and inviting us to rethink and explain the crisis of the war by means of another crisis. In other words, action and participation turn the subjects of crisis into the objects of the same crisis.

2. Women of the Pueblo: Gaining Visibility in the 18th Century

As José Miguel López García has affirmed in his work on the Esquilache Riots, the revolt was eminently “un movimiento popular” (a popular movement) whose main social actors were servants, artisans, construction workers and day laborers; in general, “trabajadores que vivían de su salario en unas condiciones miserables” (López García 2006, p. 14) (workers who lived off their salaries in miserable conditions). This active participation found artistic expression in the visual production of the time. A number of paintings featuring the Esquilache Riots put at the center of the frame the unity of the populace, leading actor of the disturbances. Such is the case of Goya’s famous painting “The Esquilache Riots” (1766) (Figure 1), which illustrates one of the manifestations of crisis in the urban as a space of social diversification and therefore more prone to rebellions and protests.4 Scholar of modern Spanish cultural studies Nil Santiáñez explains this concept of urban crisis well: a destabilization of order provoked by the masses due to a moment of high social tension in which the normativity of the urban space is questioned and subverted as the citizen deviates from civic codes of urbanity and traverses physical boundaries and symbolic norms, opening up the potential for the disruption of these norms (Santiáñez 2003, p. 213). Indeed, Goya’s painting shows a multitude of rebels in a defiant attitude gathered in downtown Madrid, as indicated by the town hall tower on the left of the frame and the royal palace in the background. The urban blurring of limits is reinforced by the social dissolution of borders, a symptom of modernity according to Berman: in this central street members of the pueblo dressed against Esquilache’s reform, representatives of the upper classes in dress coats, and a Franciscan friar coincide—nobility, clergy and the working class, representatives of the three strata that shaped the social mosaic of mid-18th century Madrid.

Figure 1.

“The Esquilache Riots”.

These socially marginalized collectives were usually referred to in the press of the time as “the mob”, “rabble” or “people of a low type” (Menéndez Pelayo 1998, p. 92) as a way to highlight their social marginalization in contrast with the enlightened and learned elites, but also as a reflection of the fear associated with the crisis they came to represent. Among them, women, who also participated in this symbolic depreciation—“mujeres desgreñadas” (unkempt women), “brutas mujerzuelas” (ignorant floozies) and “furiosas amotinadas” (raging rebels) (Imparcial 1892)—played an essential role. In fact, we need to trace the origin of the conflict back to a female figure, as it has been recorded in the annals of history: one day after the street altercations, on 24 March 1766, a group of workers of both sexes walked towards the royal palace in order to continue their protest, where they faced a military squad who opened fire against the protesters, which resulted in the death of a woman who was among them. This single action immediately triggered a furious dispute between guards and rebels that resulted in beatings, fires, and deaths on both sides (Domínguez Ortiz 2005, p. 104). But it is important to note that more than half of the rebels gripping sticks, stones, knifes and handguns were women. As some critics have pointed out, women in particular were portrayed in cultural works of the time as feisty, fierce and passionate and therefore prone to participate in uprisings and revolts (Antigüedad 2010, p. 11). This might be explained by the fact that, as they were in charge of the domestic economy, working-class women were the first to note shortages in food and consumer goods or, in other words, to feel the effects of the crisis triggered by Esquilache’s Enlightened reforms, which gave them a direct reason to participate in altercations. Similarly, Thompson argues that women were in fact responsible for starting the mutinies in 18th-century England precisely because they were experienced in detecting “short-weight or inferior quality” products in the market (Thompson 1971, p. 116).

Indeed, for the next few days after the killing of the woman in the street, females from Madrid suburbs with scissors in hand took the hats of upper-level individuals they encountered in the street and cut them to make them look like broad-brimmed hats in the Spanish fashion. And not just that: the day after the accident, groups of women walked to Casa-Galera, the women’s prison, and to the Colegio San Nicolás de Bari, where renegades and morally suspicious women were confined awaiting “reform”. Hundreds of women were liberated from both institutions by the female mobs. This act of liberation showed that women already enjoyed a certain amount of political power along with the freedom to take action, which was brought about by these moments of crisis. This physical movement from closed into open spaces marks a symbolic displacement inasmuch as the freedom women enjoyed after liberation from confinement was a reaction to centuries of imprisonment behind closed doors and behind social norms that have circumscribed women’s role in a patriarchal society. So beyond altering urban normativity, women see moments of crisis as an opportunity to open up new avenues of subjectivity and new spaces of freedom, desire, action, and resistance to power, which would inevitably result in a threat to the patriarchal social order. In Michel De Certeau’s terms, these unstable subjects defy location within their proper place and actualize their spatial trajectory by traversing social limits and boundaries (De Certeau 1984, pp. 117, 128). Via movement and invasion of the public sphere, women claim a visible place in History and a space for themselves in Spanish cultural modernity.

3. Women in War: Opening Spaces of Female Agency

The historical leading role of women as active subjects paves the way for their construction as objects of representation in images of war. The War of Independence (1808–1814) was a national war of resistance against the Napoleonic invasion. Although a popular and national war, it has often been considered an international conflict due to the participation of Portuguese and mercenary armies of different origins, along with the intervention of British troops which aided the Spanish victory. As many historians have pointed out, this war signals the beginning of the so-called crisis of modernity, characterized by a climate of permanent political, administrative and institutional crisis that marked the transition from the Ancien Régime to a liberal system.5 This critical period of six years, which would transcend the notion of crisis to go down in history as a revolution due to the profound transformations it brought about, would continue to have important consequences in the social and political organization of Spain throughout the 19th century. For instance, it was crucial for the crystallization of constitutional principles of the nation and in its overseas possessions, as not only did it pave the way for the triumph of liberalism, but it established the foundation in 1812 for the first constitution in the history of Spain, symbol of freedom.

This symbolic advancement is undoubtedly closely connected with the popular nature of the war—which employed the totality of the civil population, from working-class men to children and the clergy—and especially with the participation of lower-class women, a phenomenon which has not been sufficiently studied and that gives a modern dimension to the armed conflict (Aymes 2008, p. 351).6 As María Romeo Mateo has argued, the need to construct a national identity against the French required the symbolic visibility of women, and therefore the female presence in the war was essential for its rhetoric as a “guerra del pueblo,” that is, a war of the people or of a long excluded and ignored collective that comes to claim its place as representative of the sovereign nation (Romeo Mateo 2015, p. 68). But of course, the press and public opinion encouraged the mobilization of women according to the dominant discourses on gender in 19th-century Spain, which categorized women in the inactive role of victims and pigeonholed them in the cultural tradition of passivity and resignation in times of war. These, after all, were the values that configured the national essence that was at the intersection of the construction of the nation-state.7 As Elizabeth Munson has clearly put it, while the reconfiguration of space brought about by modernity opened new possibilities for “the performance of gender”, it continued to “reinforce gender distinctions, even if in a modified form” (Munson 2002, p. 64). The following citation from a public notice that appeared in the city of Valencia in 1808 serves to note how in a war that tried to involve everybody, women still had a limited margin of action:

Hilad el hilo, blanqueadlo, haced calcetas, cosed camisas, moderad el lujo, y renunciad a las ropas extranjeras. Esto es lo que corresponde a vuestro sexo, lo que exige de vosotras la patria, y lo que necesitan nuestros guerreros. Lo más importante: guardad retiro. El pudor, el recato y la modestia sean una valla que os haga inaccesibles mientras durare la guerra... que no se vea una mujer en las calles de nuestra capital. Madrugad con la aurora para ir al templo a pedir al Dios de la victoria la conceda a nuestros ejércitos, pero antes de que el sol haya registrado nuestras calles, volveos a vuestras casas, aguardad para presentaros en público a que vengan nuestros valientes coronados de laureles... Tomad mi consejo: hilad y cosed. Si lo hacéis así, seréis acreedoras al reconocimiento de la patria(Fernández García 2007, p. 559).8

The spatial terminology used in this proclamation aims at pinioning women and encouraging them to participate in the war within the limits of the familiar and domestic sphere. Expressions such as “remain,” “indoors,” “wall,” or “not be seen” point to the fact that restraining women physically was more important than their value in fighting against the enemy. The true and real crisis would be to have loose women defy the spatial limits imposed on them by the patterns of historical subordination. After all, as Mary Nash, one of the experts in the study of women’s political experience in times of war, has contended, redefining the public and the private, questioning the separated spheres, and demanding visibility in the public space cannot be disassociated from the trajectory of female emancipation (Nash 1994, p. 171). In this way, female participation in the war followed in many cases the normative discourse around a feminine nature: they provided supplies to soldiers on the front, went door to door requesting food and medicines, and urged men to fight.9

But there was more to it. The war opened avenues of female action that had been either closed or available to women in a limited way before 1808. Following the steps of “several hundred women” who “proposed forming a women’s militia” in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802) (Goldstein 2001, p. 116), Spanish women took to the streets and participated in the public conflict. Women who protest collectively have important historical precedents. In the French Revolution they played an essential role as agitators, sounding the alarm in Paris, entering stores and workshops to call men into action, throwing objects at guards, and challenging the armed forces in the middle of the street—actually it is no coincidence that it was during the French Revolution when people’s sovereignty was claimed as a principle.10 Women deviated from highly stereotyped feminine roles and became even more visible and active, appropriating a male role, questioning traditional formulas and actualizing their existential, cultural and spatial trajectory, in De Certeau’s terms, through physical and symbolic acts “of crossing, inversions and displacements” (De Certeau 1984, p. 128). In fact, the spatial terminology that served to constrain women in the home continues to be used to drive them out of doors. The liberal Spanish newspaper La Vanguardia published an article in 1937 remembering the women of 1808 and the profound change they brought with them. The next citation proves the fundamental role of the Habermasian public sphere—in this case, the press—as a subject of crisis that articulates a resistance through public speech:

En el primer momento de la guerra, nuestras mujeres, un poco descentradas, un poco fuera del ambiente, sintieron la necesidad de hacer acto de presencia en la lucha... Entonces surgió la mujer en la calle, con su mono azul, su cartuchera y su fusil, y la mujer en el frente, al pie de un cañón o al pie de una ametralladora. Fue algo que sirvió para que los reporteros extranjeros sacasen a relucir los tópicos más viejos acerca de nuestro país.(Vanguardia 1937, p. 3).11

Phrases like “off-center” and “out of their element” are spatial metaphors that serve to theorize the deviant subject’s location in relation to the norm, which exists only upon the condition of its transgression—“woman in the street, woman on the front lines.” The image of “female present in the struggle” identifies the female protest as object of criticism—and therefore object of crisis—in a dominant discourse built around stereotypes of masculinity which include these deviant bodies in order to exclude them from the social and moral norm. Again, inclusion is a prerequisite for exclusion. We need to remember that the press and social texts of the period established a relationship between protesting women and lack of morality (Lucea Ayala 2002, p. 188), an association reinforced by the strong connection between itinerancy (or public presence) and female immorality in the cultural imaginary of the 19th century. The image of the blue overalls is a direct reference to militiamen in the Spanish Civil War12 whose outfit would not only indicate their social origins but also their opposition to fascism and their defense of the Republic. Working class women in the protest movement are put at the same level as working class men, in both cases a marginalized collective that configures a political community that resists power by making their members visible in the public sphere. This visibility is essential, the author of the article says, in order to actualize “traditional conceptions of our nation,” that is, the circumscription of feminine activity to the domestic sphere. By bringing this issue to the fore, the author of the article uses the construction of these women in the street as a way to highlight the anachronism in Spanish customs and to encourage Spain to follow the model of countries such as France and England regarding social, economic and political rights of women.

4. Goya and the Advancement of a Feminist Agenda

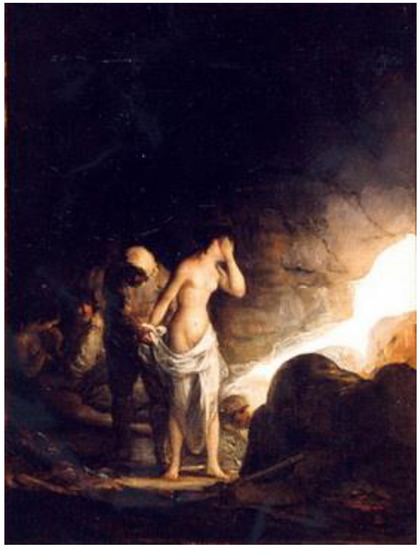

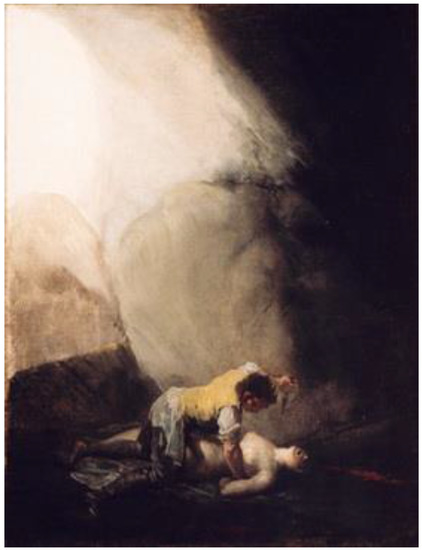

The cultural representations of the time contributed to bringing to light this active female participation. In the 82 prints contained in the series The Disasters of War, painted between 1810 and 1820, Goya moves away from painting tapestries commissioned by members of the aristocracy and etchings of vain feminine models embodying vices and capricious habits to focus on women from a new perspective, as victims of violence but also as leading agents of the battle. The engravings give prominence to working women in different roles. There are several plates showing women in an attitude of passivity and resignation, as indicated by the passive verbs used to describe them: woman awaits, rests, lies at the ground, lies dead, huddles behind ruins, kneels. These images have two important antecedents in two dramatic scenes painted between 1798 and 1808 by Goya: “Bandido desnudando a una mujer” (A Bandit Undressing a Woman) (Figure 2) and “Bandido asesinando a una mujer” (A Bandit Knifing a Woman) (Figure 3) in which women occupy the central space of the frame, not only as objects of representation but as objects of sexual and physical violence in that their naked bodies are being brutally used for male recreation.13

Figure 2.

“A Bandit Undressing a Woman”.

Figure 3.

“A Bandit Knifing a Woman”.

This female passivity soon gives way to cultural examples introducing women in action, a sign of modernity in process: in engravings “No quieren” (They don’t want it), “Ni por esas” (Nor those) and “Amarga presencia” (Bitter presence), women actively resist physical and sexual violence perpetrated by French male soldiers, which captures an aspect that transcends the Spanish geographical and cultural frontiers to announce one of the basic and impending foundations of the ideology of feminism in the 20th century: resistance to violence against women, in open confrontation with a patriarchal and relational system where women are subordinate to men in the worst possible way. Plates “Las mujeres dan valor” (Women are courageous) (Figure 4) and “Y son fieras” (And they are fierce or And they fight like wild beasts) (Figure 5) are relevant in that they show women as agitators. Both of them depict women of the pueblo actively fighting the French invaders with knives, spears and rocks in a way that suggests women have a justification for violence and rebellion after centuries of oppression. Crises give them the opportunity to set the record straight. The use of the word “wild beasts” to describe militant women establishes an analogy between women and animals. There are different readings of this connection. Romeo Mateo has seen this rage on the part of women as the excuse for Frenchmen to invade Spain and bring European modernity to an otherwise backward and uncivilized nation (Romeo Mateo 2015, p. 76). This theory would connect women once again with the plebs and would serve to underline the social marginalization that defines this group. This would be the attitude of Gustave Le Bon, theorist of the mob who had reactionary attitudes towards women and other social groups that claimed greater rights. Indeed, he identified “the irritability, the impulsiveness, their incapacity to reason and their mobility” as elements typical of those “belonging to inferior forms of evolution”, that is, women and savages (Le Bon 2002, pp. 10, 13).

Figure 4.

“Women are courageous”.

Figure 5.

“And they are fierce”.

However, the fact that these warrior women appropriated a male role and emerged as virile or manly women identifies them with those New Women that appeared in the European literature of the late 19th century who questioned the womanly ideal and wanted to be at the same level as men (Charnon-Deutsch 1994, p. 143). To attain this, the first step is appropriating traditionally male physical spaces, such as the battlefield, as well as symbolic ones, such as the right to carry and use weapons and defend the homeland and, by extension, access to citizenship or citoyenneté (Bock 2002, p. 42). In this sense, Lynne Hanley, among others, has identified war as a key space for the negotiation and articulation of gender identities (Hanley 1991, pp. 134–35). Here, the female presence proves to be disruptive as it would come to alter the normativity of the urban space and to usher in a world of inverted roles. Goya takes women out of the reclusion typical of the Ancien Régime and gives them a new position of much greater visibility in which “they were not only much more widely seen, but also much bolder in their general behaviour” (Esdaile 2014, p. 8). Women as wild beasts destabilize the order and introduce a new order of crisis when they abandon the submissive role and walk away from the traditional image of the compassionate, resigned and selfless woman circulated by conservative gender discourses.

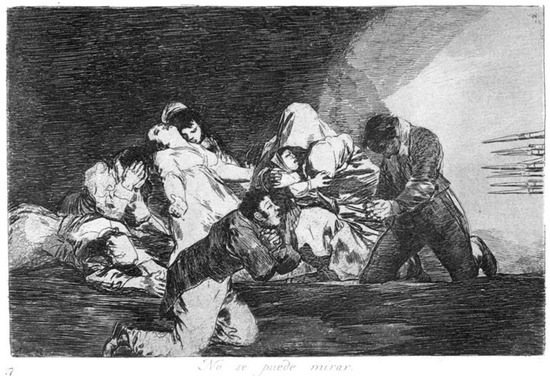

In this appropriation of a male role lies the rejection of the marginal role of women and the demand for equality on which the agenda of the first wave of feminism will be built in the second half of the century. The engravings “No se puede mirar” (One cannot look) (Figure 6), which brings echoes of the famous Third of May 1808 painted by Goya in 1814, reveals men and women alike being the target of execution by a French firing squad; and “Escapan entre las llamas” (They escape among the flames) (Figure 7) shows men and women together running into the night, amidst chaos and terror. These images are both inspired by another 1808–1809 painting from the Marqués de la Romana collection, “Ataque a un campamento militar” (Attack on a Military Camp) (Figure 8) that shows a woman in the center of the piece cradling a baby and standing next to a group of male civilians, all of which are about to be shot by French troops. By turning women and men into equal victims of the horror of the war, Goya’s political eye reduces the distance between the sexes, moves forward in the social itinerary of women, and introduces a principle of equality that, overcoming biological differences, needs to be read as a demand for the exercise of individual rights. In this sense, Goya turns a dreary episode into a political and cultural revolution which is a tribute to equality and, by extension, to modernity.

Figure 6.

“One cannot look”.

Figure 7.

“They escape among the flames”.

Figure 8.

“Attack on a Military Camp”.

5. Becoming Modern: Crisis as Symbol of Emancipation

Moments of crisis are closely connected with times of profound historical disruption and change. In the light of the cultural work as an instrument of political protest, the breaking of a relational system between the sexes forces us to rethink the experience of modernity from a feminine perspective. In fact, the symbolic force of the term “modern” requires a process of differentiation, a change and an act of separation from the past (Simmel 1904, p. 133), which is what these virile women come to represent by moving away from the traditional feminine role and by inverting gender relations. Following up on this idea, Felski concluded as a corollary of her reading of Berman that militant women portend the birth of a conscience and a process of constitution of modern subjectivities that develop a resistive agency and that want to be “free of familial or communal ties” (Felski 1995, p. 2). One of the “wild beasts” fighting in Goya’s plate puts her baby behind and the spear forward, in a symbolic act of displacement in which the lower class female (who has to reconcile both the home and the public sphere) breaks away from the cult of maternity as the maximum horizon of female self-realization. In the cultural imaginary of the 19th century, this distancing came to encapsulate the emancipation of women, as a women’s journal of the period would claim (Armiño De Cuesta 1871, p. 15).

Becoming a “subject” involves a splitting of identities which fuels an interruption of the logic of subjection and a certain pragmatics of self-constitution. By abandoning the home and the family and standing “tägig-frei” (Berman 1988, p. 66) in the battle field, women take a leading role in the historical formulation of a social process of negotiation and modification of the structure of domination based on gender. Women themselves ended up participating in the very process of the production of the crisis by becoming protagonists in these cultural works that explain the crisis of the war by means of another crisis: the symbolic advancement of women represented by the emergence of a new female political subjectivity and the renegotiation of culturally accepted norms of femininity. In this sense, it would be wise to revisit the concept of feminism in the light of these actions, experiences and initiatives directed towards social change in a time when the word “feminism” didn’t yet exist.

Many more riots took place throughout the 19th century in Spain that we won’t be able to discuss for obvious reasons. Suffice it to say that working-class women continued to have a prominent role in street altercations that crowd the pages of history as well as Spanish cities. To name a few: 18 May 1898, Badajoz: a demonstration organized just by women took place in order to protest against price increases of basic foods. December 1895, Tarazona: inequality and injustice in the taxation of consumer goods provoked a revolt initiated by women against the wealthy. The hunger mutinies that took place in several cities of Castile between 1854–56 were a reaction to the crises of subsistence provoked by the increase in the price of bread; radical behavior was displayed on the part of women who rose up against institutions and prevented officials from taking wheat out of the city limits (García Sanz 1977, p. 431).

Literature echoed these social phenomena. One of the most paradigmatic examples comes with the narrative work The Tribune of the People (1882), by feminist Spanish writer Emilia Pardo Bazán. In one of the last scenes, after not being paid for months, a group of cigar makers barricade themselves inside the factory and confront institutional power by refusing to work until they receive their salary, just like “rich men” (Pardo Bazán 1975, p. 239). By asking for economic and social equality, working women demand recognition as citizens with full rights and contest a sexist and classist society that exploits their bodies. Cigar maker riots and the subsequent alteration of urban normativity were very common in Spain in the second half of the 19th century, and they concealed a feminist agenda. As Rosa Capel Martínez has said, the discrimination suffered by women in the space of the factory served “to promote both their awareness of women’s rights and their association in order to defend these rights,” a sine qua non of the emancipation of any social group (Capel Martínez 1999, p. 132). By turning the personal into the political, the female vindication is triple: equal access to professional activity for men and women; parity in wage-earning jobs; and the right to protest in the public space, which was still regarded as a male sphere. In this sense, times of war and crisis would symbolize a metaphor of female emancipation.

6. Conclusions

Times of disturbance bring with them change that is deeply desired and long overdue. Just as the quotation that opens this essay indicates, there have been revolutions for the better, an example of which is the emergence of widespread female political participation after centuries of oppression. For those who are fans of the series, the example of Downton Abbey is a case in point. After World War I, many are the times in which the aristocratic and privileged members of the Crawley family lament that “times are not what they were”; habits are changing, morality becomes less restricted; maids and footmen are ceasing to exist; women are more “loose” in the way they dress, in the use they make of public spaces, and in their relationships with men; and as a consequence, the cultural logic of male dominance and female subordination is problematized. The transformative potential of women to organize and change society should not be underestimated, and the same is true for the close connection between issues of gender and a nation’s progress towards modernity. One of the functions of art is to question existing gender norms and propose alternative models of femininity. Revealing the symbolic power of art as an instrument of social critique and political protest, literary and visual representations contain numerous cultural elements that encourage female action; but also they give center stage to marginal subjects on whose shoulders lie the forces of progress and advancement.

Crises sow the seeds that never cease to grow, irrigated by the physical and symbolic mobilization of resistance to the normalizing discourses of society. As López García points out in reference to the Esquilache Riots, even though order was reestablished two days after the outbreak of violence, nothing would be the same again (López García 2006, p. 11). Similarly, although the revolts of cigar makers were diligently contained and repressed, which points to the need of a disciplinary society to combat disorder and restrain those who pose a threat to order, change would inevitably follow. Women embody the reality of crisis in their potential for action and their power to resignify the norm about woman’s role in society, her rights, and her mapped out spaces of movement. By taking themselves to the streets to protest against food price increases, to resist male physical violence, to defend their nation against foreign forces, or to demand equal pay, women in modern Spain opened new spaces of subjectivity and paved the way for future feminist movements, showing that there is no need to concentrate their energies on “women’s issues,” that is, access to suffrage and to education, in order to propel change. Even before these women’s rights were attained, and long before they could participate actively in the passing of laws, women were making themselves heard and seen. They were changing things from the outside and influencing the broader constellation of political forces, and precisely this inclusiveness is what makes possible a modern project for the future weaved on a network of power (crucial to the formation of the subject) and resistance.

The result of crisis is the advent of modernity, a historical period which is characterized according to scholar of feminism and social movements in Spain, María Dolores Ramos, by the emergence of hidden and diffused voices, female experiences, and social practices that illustrate the advancement of feminisms (Ramos 2011, p. 26). These hidden voices started to emerge in the 18th century and continue to be articulated and enunciated in our contemporary times. After all, modernity is an unfinished project, as Habermas’ seminal essay reads (Habermas 1997): an impending crisis motivated by marginal subjectivities that represent a constant threat. Take the new social movements that have emerged in the 21st century, for example. In what brings echoes of the Esquilache Riots, the awakening of a social and political awareness in times of unprecedented economic crisis has led to the active participation of thousands of citizens who take themselves to the central streets of Spanish cities—again, the concept of crisis cannot be disassociated from the idea of the street as a space of opinion formation—to demand their participation in the making of political decisions, a phenomenon that reveals a context of crisis at a national and international level that requires new codes and values, new political forms of representation, and a new language, just like the 19th century needed to coin the term “feminism” to describe the movement that demands rights to achieve a new personal, social and legal status for women.

These emerging collective identities—be it women, the plebs, or ordinary people—break with the traditional and institutional narrative on Spanish modernity according to which only an enlightened minority has been responsible for advancing projects of political citizenship and economic modernization. But this fabrication falls into a crisis when majorities located at the margins of the intellectual, business and political elite wake up, dare to think, and act by themselves—a symptom of a modern subjectivity. In this appropriation, these plebeian masses rise as historical agents of modernization and social change which, in keeping with the ambivalent nature of modernity, is always chaotic and disorderly. Let the words of Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset serve as closing remarks for this work: modernity invades every nation sooner or later, and this invasion comes with illegitimacy and desecration of order (Ortega y Gasset 1962, p. 129). Let’s be thankful for this illegitimacy and for the crisis that it brings with it.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2000. Means without End: Notes on Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Antigüedad, María Dolores. 2010. Goya y la génesis de un nuevo modelo femenino durante la Guerra de la Independencia. Revista HMiC: Història Moderna i Contemporània 8: 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Armiño De Cuesta, Robustiana. 1871. La mujer emancipada. La Moda Elegante Ilustrada 30: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Aymes, Jean-René. 2008. La Guerra de la Independencia: Héroes, Villanos Y Víctimas (1808–1814). Lleida: Milenio. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, Marshall. 1988. All that is Solid Melts into Air. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Gisela. 2002. Women in European History. Malden: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Breward, Christopher, and Caroline Evans. 2005. Fashion and Modernity. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Cantos Casenave, Marieta. 2008. Del cañón a la pluma. Una visión de las mujeres en la Guerra de la Independencia. In España 1808–1814. De Súdbitos a Ciudadanos. Edited by Juan Sisinio Pérez Garzón. Madrid: Junta de Castilla La Mancha, pp. 267–86. [Google Scholar]

- Capel Martínez, Rosa. 1999. Life and Work in the Tobacco Factories: Female Industrial Workers in the Early Twentieth Century. In Constructing Spanish Womanhood. Female Identity in Modern Spain. Edited by Victoria Lorée Enders y Pamela Beth Radcliff. Albany: State University of New York, pp. 131–50. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Irene, Gloria Espigado, and María Cruz Romeo. 2009. Heroínas para la patria, madres para la nación: Mujeres en pie de guerra. In Heroínas y patriotas. Mujeres de 1808. Edited by Irene Castells, Gloria Espigado and María Cruz Romeo. Madrid: Cátedra, pp. 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- Charnon-Deutsch, Lou. 1994. New Women. In Narratives of Desire. University Park: The Pennsylvania State UP, pp. 141–86. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Ortiz, Antonio. 2005. Carlos III y la España de la Ilustración. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Esdaile, Charles J. 2014. Women in the Peninsular War. Norman: University of Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

- Espigado, Gloria. 2010. Europeas y españolas contra Napoleón. Un estudio comparado. Revista HMiC 8: 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Felski, Rita. 1995. The Gender of Modernity. Cambridge: Harvard UP. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández García, Elena. 2007. Las Mujeres en los Inicios de la Revolución Liberal Española (1808–1823). Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Fusi, Juan Pablo, and Jordi Palafox. 1997. España: 1808–1996. El Desafío de la Modernidad. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- García Sanz, Ángel. 1977. Desarrollo y Crisis Del Antiguo Régimen en Castilla la Vieja. Economía y Sociedad en Tierras de Segovia, 1500–1814. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Godineau, Dominique. 1993. Hijas de la libertad y ciudadanas revolucionarias. In Historia de las Mujeres en Occidente. Edited by Georges Duby and Michelle Perrot. Madrid: Taurus, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Joshua S. 2001. War and Gender: How Gender Shapes the War System and Viceversa. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1997. Modernity: An Unfinished Project. In Habermas and the Unfinished Project of Modernity. Critical Essays on the Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Edited by Maurizio Passerin d’Entrèves and Seyla Benhabib. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, Lynne. 1991. Writing War: Fiction, Gender and Memory. Amherst: University of Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, Eric. 1994. Age of Extremes: The Short 20th Century 1914–1991. London: Michael Joseph. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Moreno, Luis. 1993. Crisis de la modernidad en el pensamiento español: Desde el Barroco y en la europeización del siglo XX. Anales del Seminario de Historia de la Filosofía 10: 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Juliá, Santos. 1984. Madrid, 1931–1934. De la Fiesta Popular a la Lucha de Clases. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon, Gustave. 2002. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- García, López, and José Miguel. El motín de Esquilache. Crisis y Protesta Popular en el Madrid del Siglo XVIII. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Lucea Ayala, Víctor. 2002. Amotinadas: Las mujeres en la protesta popular de la provincia de Zaragoza a finales del siglo XIX. Ayer 47: 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, Manuela. 2008. Goya en Tiempo de Guerra. Madrid: Museo del Prado. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Pelayo, Marcelino. 1998. Historia de los Heterodoxos Españoles. Regalismo y enciclopedia. México DF: Porrúa. [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo, Aurora G. 2000. True Catholic Womanhood: Gender Ideology in Franco’s Spain. DeKalb: Northern Illinois UP. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Lewis. 1961. The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. New York: Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Munson, Elizabeth. 2002. Walking on the Periphery: Gender and the Discourse of Modernization. Journal of Social History 36: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, Mary. 1994. Experiencia y aprendizaje: la formación histórica de los feminismos en España. Historia Social 20: 151–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega y Gasset, José. 1962. Una interpretación de la Historia Universal. In Obras completas IX. Madrid: Revista de Occidente, pp. 11–229. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Bazán, Emilia. 1975. La tribuna. Edited by Benito Varela Jácome. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, María Dolores. 2011. Feminismo laicista: voces de autoridad, mediaciones y genealogías en el marco cultural del modernismo. In Feminismos y Antifeminismos. Culturas Políticas e Identidades de Género en la España del Siglo XX. Edited by Ana Aguado and Teresa Mª Ortega. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Laura. 1973. The Spanish Riots of 1766. Past & Present 59: 117–46. [Google Scholar]

- Romeo Mateo, María Cruz. 2015. Españolas en la guerra de 1808: Heroínas recordadas. In Heterodoxas, Guerrilleras y Ciudadanas. Resistencias Femeninas en la España Moderna y Contemporánea. Edited by Mercedes Yusta and Ignacio Peiró. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, Ana. 2009. Heroísmo femenino, memoria y ficción: La Guerra de la Independencia. Vanderbilt e-Journal of Luso-Hispanic Studies 5: 265–94. [Google Scholar]

- Santiáñez, Nil. 2003. El fascista y la ciudad. In Madrid de Fortunata a la M-40. Un Siglo de Cultura Urbana. Edited by Edward Baker y Malcolm Alan Compitello. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, pp. 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 1904. Fashion. The International Quaterly 10: 130–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledziewski, Elisabeth G. 1993. Revolución Francesa. El giro. In Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Edited by Georges Duby and Michelle Perrot. Madrid: Taurus, pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Squicciarino, Nicola. 1998. El Vestido Habla: Consideraciones Psicosociológicas Sobre la Indumentaria. Translated by José Luis Aja Sánchez. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Edward Palmer. 1971. The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century. Past and Present 50: 76–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, Janis A. 2002. Goya: Images of Women. New Haven: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Willen, Diane. 1992. Women in the public sphere in early modern England: the case of the urban working poor. In Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women’s History. Edited by Dorothy O. Helly and Susan M. Reverby. Ithaca: Cornell UP, pp. 183–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yépez Piedra, Daniel. 2010. Víctimas y participantes. Las mujeres españolas en la Peninsular War desde la óptica francesa. Revista HMiC 8: 156–77. [Google Scholar]

- El Imparcial, 1892 July 2.

- La mujer y la guerra. 1937, La Vanguardia, May 20.

| 1 | After the death of the last Habsburg monarch, the new Bourbon dynasty was established in Spain in 1759 with Carlos III. A firm proponent of enlightened despotism (a form of absolute monarchy that embraced rationality, fostered education, and allowed religious tolerance and freedom of speech), the king focused on modernizing the Spanish nation by implementing a number of far-reaching reforms; from promoting science and university research, to facilitating trade and commerce, modernizing agriculture, and improving Spanish infrastructure: roads, canals and drainage works were established and sewage, street-lighting, and rubbish collection were implemented. Charles III’s government believed it was important to rescue Spain from decay by Europeanizing the country. In the view of the Bourbon dynasty, French culture was the cornerstone of modernity. Hence the government’s attempt to force madrileños to adopt French dress: among all the changes and reforms aimed at modernizing the country and making Spain more prosperous, fashion played a fundamental role as an expression of individuality and identity construction, and as a form of protest and political vindication, as critics have pointed out (Squicciarino 1998, pp. 149–90; Breward 2005; Bock 2002). However, as we shall see in the next pages, Spaniards saw in the new policies regarding attire an excuse to riot against more pressing issues such as the rising prices in bread, oil, coal, and cured meat, caused by Esquilache’s liberalization of the grain trade. |

| 2 | All translations from Spanish are mine, unless otherwise indicated. |

| 3 | The popular protest was a reaction to one of the worst crises of subsistence in the 18th century. Between 1760 and 1765, agricultural production was significantly reduced due to unfavorable meteorological conditions and a series of bad harvests. This led to an increase in the price of bread and other staples, which in those five years reached the highest price allowed under the law. As a consequence, Esquilache was responsible for passing a law for the liberalization of the grain trade, a policy that only benefited the Church and the clergy, who accumulated corn and wheat directly from the fields and hoarded most of the harvests for sale later. Therefore, the popular revolt was not only a challenge against royal authority, but also against religious monopoly. See Rodríguez’s work (Rodríguez 1973) and López García (López García 2006, pp. 92–95) for details about this crisis of subsistence. |

| 4 | Many are the historians and cultural critics who have read the urban as the ideal environment for crises and riots to develop. Lewis Mumford saw the city as the stage for drama, made possible precisely due to “the inclusion of human diversities within the enclosed urban amphitheater” (Mumford 1961, p. 117). In the specific case of Spain and, in particular, the emergence of the working class as a political subject during the Second Republic (1931–1936), historian Santos Juliá speaks of the urban space as the locale where the raising of awareness among the dispossessed takes place (Juliá 1984, p. 415). |

| 5 | The War of Independence has attracted the attention of numerous historians and critics. See Fusi and Palafox (Fusi 1997, pp. 17–25) for an analysis of the causes, reactions and different stages of the War as one of the most important crisis in the modern history of Spain. |

| 6 | Espigado (2010), Yépez Piedra (2010), Romeo Mateo (2015), Esdaile (2014), and Rueda (2009) have studied the participation of women in the War of Independence along with their role in the formation of a national identity during the conflict. Rueda’s is particularly interesting because it focuses on the artistic treatments this participation has received, providing numerous cultural examples of what the author calls “female heroines” including the famous Agustina de Aragón, historical figure who became a legend in the literary and visual representations of the conflict when she crossed the line from a passive role as mere supplier of food and water to the soldiers to action and participation as a fighter at the same level as men. See Rueda’s list of works cited for extensive references on this female character (Rueda 2009, pp. 288–91). |

| 7 | On that subject, see the work by Castells, Espigado and Romeo, whose title is already illustrative of this traditional construction: “Heroínas para la patria, madres para la nación” (“Heroines for the homeland, mothers for the nation”) (Castells 2009). |

| 8 | “Thread the needle, whiten the thread, knit socks, sew shirts, moderate spending, reject foreign fashion. These are the duties of your sex, what the fatherland asks of you, and what our warriors need. Most importantly: remain indoors. Let decency, constraint and modesty be a wall that makes you unreachable during the war... a woman must not be seen in the streets of our capital. Rise early with the first light to go to church to pray to the God of victory that He grant it to our armies, but before the light illuminates our streets, return to your houses, wait until our valiant men return crowned with glory to present yourselves in public... Follow my advice: knit and sew. If you do this, you will be deserving of the recognition of the fatherland.” |

| 9 | Cantos Casenave has explored the ambivalent stance on women of official propaganda during the war (Cantos Casenave 2008, p. 276). |

| 10 | See Elisabeth Sledziewski for the role of women in the French Revolution (Sledziewski 1993). Godineau has studied women as “agitators” in revolutions of Western societies (Godineau 1993), while Thompson has explored the female presence in mutinies in 18th century England (Thompson 1971). |

| 11 | “In the beginning of the war, our women, a bit off-center, a bit out of their element, felt the need to declare themselves present in the struggle... At that point the woman in the street came into existence, with her blue overall, her cartridge belt and her rifle; and also the woman on the front lines, at the foot of a cannon or at the foot of a machine gun. It was something that allowed foreign reporters to bring to light the most traditional conceptions of our nation.” |

| 12 | One of the bloodiest conflicts in the history of modern Spain, the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) was fought between the Republicans, loyal to the democratically elected leftist government of the Second Spanish Republic; and Nationalists, a right-wing group led by General Francisco Franco, who staged a coup supported by the military and by a number of conservative groups. After three years of atrocities, the Nationalists won and Franco ruled Spain for the next 36 years, from April 1939 until his death in November 1975. This centralized dictatorship, which has shaped the trajectory of Spain until today, not only froze political, economic and social modernization but restricted the advances of women and feminism in terms of education and professional opportunities. With a legislation that was modeled around the Napoleonic code that compared married women to minors, Francoism rechanneled females back into the home and fabricated a discursive narrative around a self-sacrificing, obedient and subordinated feminine archetype that made women good mothers and wives, as the success of the nation depended on the successful workings of a traditional conservative family. See Morcillo for a study of the conservative ideology of female domesticity in Franco’s Spain (Morcillo 2000). |

| 13 | These images are part of a collection of eight cabinet paintings by Goya (originally they were 11 paintings, but three are lost) belonging to Diego del Alcázar, the current Marquis of the Romana, direct descendant of Pedro Caro y Sureda, 3rd Marquis of la Romana, a Spanish general in the War of Independence. He was the son-in-law of Don Juan de Salas, a Mallorcan businessman who acquired and collected the series. See Mena (Mena 2008) and Tomlinson (Tomlinson 2002, pp. 236–43) for an analysis of these paintings. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).