1. Introduction

A boundary is not that at which something stops, but as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins its essential unfolding [

1].

Martin Heidegger, “Building, Dwelling, Thinking”

Increasing emphasis on the delivery of healthcare that is integrated across the professions requires clinicians with teamwork and collaboration skills as well as an understanding of the roles of other healthcare professionals. The World Health organization [

2] as well as the Institute of Medicine [

3] put forth vision statements calling for the redesign of healthcare curriculums in ways that promote the development of the clinician skilled in this way. Despite the many barriers to developing learning experiences that bring students from different programs together, interprofessional (IP) experiences in many forms from didactic to experiential have developed recently in programs across the United States.

This paper draws on the writings of Homi K. Bhabha in an effort to provide insight into the sociocultural development of the student during the interprofessional learning experience. What is happening to students in IP learning experiences? Professional cultures create boundaries [

4]. During IP experiences these students arrive with those boundaries intact, not really aware that they exist and that the student next to them has different perceptions. Are these students at an in-between, or Third Space between identity in a single profession and potential identity as an interprofessional clinician? The Bhabhaian concepts of Third Space and hybridity present an interesting lens to consider this important developmental process. Understanding of the process will aid in development of pedagogy supporting the student’s transition from the unicultural view of their profession to a hybrid view of being a professional, supporting quality collaborative care.

Homi K. Bhabha is a post-colonial and cultural theorist who describes the emergence of new cultural forms from multiculturalism. His work is complex and beautifully written, focusing on first world-third world relations. The focus on unequal relations and issues of power could be a lens for historical professional hierarchies, though the focus of this article is how the concepts of Third Space and hybridity lead to understanding of the developmental process of the health profession student’s identity during IP learning experiences.

When health profession students, enculturated into their profession discuss patient care in an interprofessional group, their unilateral view is challenged. The students are in an ambiguous area, where statements of their profession’s view of the patient enmesh with the differing approach of another health profession. This is a Third Space, where the differing professional cultures collide, allowing an interprofessional identity to potentially form. The lessons learned from other’s way of assessing and treating a patient, seen through the lens of hybridity create the environment for the development of a richer, interprofessional identity. This process allows the practitioner to be more collaborative and also to have assessment techniques that are a hybrid of all professional assessments experienced. This manuscript will seek out the ways Bhabha’s views of in-betweenness enhance understanding of the student’s development of an interprofessional viewpoint or identity.

2. Background: Bhabha’s Concepts of Hybridity and Third Space

Homi K. Bhabha, born in Mumbai India, is currently a Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University [

5]. He is considered a post-colonial and literary theorist and in The Location of Culture Bhabha assembles previous essays as he presents a theory of cultural production and identity arising from the relationship of the colonial powers on post-colonial peoples [

6]. In The Location of Culture, he uses concepts such as Third Space, hybridity, and liminality to argue that “cultural production is always most productive where it is most ambivalent” [

6]. The Bhabhian perspective is of the power relations between the dominating and the dominated in relation to the 18th and 19th century world powers. Today’s health profession empires could be viewed in a parallel manner. Bhabha focuses on power relations through the relational perspective, emerging from identity construction of both participants.

The focus in this article is not on the power relations or the dominating influence of one profession on another, although this would be a valid focus for healthcare professions. Arguments could be made for the historical hierarchy of care in medicine and its influence on other professions. With the focus of creating collaborative practitioners who will be able to care for the complex, chronic patients it is more constructive to focus on their development as interprofessional clinicians. In this paper the Bhabhian concepts of hybridity and Third Space will be used as a lens to the view the developing professional (colonial) and interprofessional (post-colonial) identities and social cultures of health profession students.

2.1. Hybridity

When traditional colonial knowledge is mixed with peoples’ own indigenous knowledge the opportunity exists for what Bhabha calls “creative heterogeneity” [

6]. The result of this encounter is the emergence of a hybrid culture that can no longer be traced back to the roots of either community. Bhabha claims that nations and cultures must be understood as narrative constructions rising out of the hybrid interactions of competing constituencies [

6]. There is an ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation [

6]. Individual’s characteristics are not limited by their ethnic heritage but are subject to change and modification [

6]. Bhabha studied the space constituted around the encounters between the colonizers and the colonized. This is termed a Third Space, where hybrid cultures are constructed as a fusion of the two.

Bhabha writes:

“It is in the emergence of the interstices-the overlap and displacement of domains of difference-that the intersubjective and collective experiences of nationness, community interest, or cultural value are negotiated…Terms of cultural engagement, whether antagonistic or affiliative, are produced performatively”.

Hybridity indicates the emergence of new cultural forms from multiculturalism. The metaphoric space where this occurs is termed Third Space [

6].

2.2. Third Space

According to Bhabha the Third Space is a liminal space, the “cutting edge of translation and negotiation” between the colonizer and the colonized” ([

6], p. 38). It is a place where we construct our identities in relation to varied and often contradictory systems of meaning [

6]. He argues cultures are never unitary or dualistic, where there is just you and the other. Rather, in the process of describing a cultural text or activity there is an interpretation and this allows for a new meaning to occur [

6]. “The production of meaning requires that these two places be mobilized in the passage through a Third Space. The meaning is neither the one or the other” ([

6], p. 53). So the thinking that someone can pass on a culture through meaning and symbols of a culture is false. He negates the view of a fixed culture that is transmitted through speaking to others unchanged. As a result the belief that it will be difficult to change because of past clashing cultures is questioned [

6].

3. Third Space in Other Discourses

Bhabha himself uses his concepts as a means of analysis of postcolonial literature including the writings of V.S. Naipaul, Toni Morrison and Joseph Conrad [

6]. Others use the concepts for political and artistic analysis [

7]. Many writings on race and national identity, including that of African, Muslim women and Native Americans draw on his thinking [

8,

9].

Conceptually, Third Space has been applied in other disciplines including education. Moje

et al. [

10] indicate Third Space as the place where spaces of home and school merge. To Moje

et al. [

10], Third Spaces are the in-between or hybrid spaces where the seemingly oppositional first and second spaces work together to generate new Third Space knowledge. There is an emphasis on the value of what knowledge the child brings from home and community to the classroom. Moje speaks of the different “funds: or sources of knowledge that can be identified and supported to increase the content literacy.

4. Interprofessional Education from a Third Space Perspective

When health profession students enculturated into their profession discuss patient care in an IP group, their unilateral view is challenged. The majority of pre-licensure students have no clinical background to draw upon in IP experiences. In an IP learning environment where students from many programs are asked how they would care for a patient, the differences in approach to care are noted by the students. This is at first surprising, then challenging to them.

In an unpublished study [

11], first year students from five health profession programs met in groups of eight to ten and discussed a case study of a patient with complex physical and psychosocial problems. Each student was asked to describe their initial assessment and plan for care. One student described the experience of hearing other student perspectives on providing care as an “evolutionary conception of my profession” [

11].

In a qualitative study of students in an inteprofessional fellowship on developmental disabilities [

12], a medical student noted after an IP encounter:

“Just watching a speech therapist gather speech data, and I get to do a physical exam alongside of a physical therapist faculty. How does she feel those particular joints? The way they go about an exam is different. It adds to my depth.”

These two settings, experienced by the author as a facilitator and researcher, exemplify the student’s understanding as they come from their disciplinary education settings to hearing students describe differing ways of assessing the patient.

Professional education may all begin with the same scientific background, but then the unique disciplinary perspective comes into play. How the patient is assessed is different. All assessments begin with the identification of cardiovascular stability, but then the assessment of a nursing student may focus on comfort and level of pain, the physical therapist on physical strength and limitations, the occupational therapist on activities of daily living, the psychologist on the patient’s mental health. The focus of care leads to different plans of care. Professional values differ, exhibited in the nature of the discussion with the patient.

The students are in an ambiguous area where statements of their profession’s view of the patient enmesh with the differing approach of another health profession. This is a Third Space, where the differing professional cultures collide. Students are experiencing the varied and contradictory systems of meaning described by Bhabha.

Identity Development in IP Education Settings

Identity, your conception of yourself is reimagined as a professional while progressing through an education program. It is based on attributes, beliefs, values, motives and experiences [

13] Khalili

et al. [

14] identifies an IP socialization framework where barriers are broken, knowledge of others is obtained, and a dual identity is formed. The concept of hybridity deepens understanding of the changing identity in these settings. The uniprofessional views are in a liminal or transitional state and the presentation of various approaches leads to hybridity as the student subconsciously expands their view of ways to approach care of the patient. Students’ experiences are translated and integrated into an interprofessional view of care. The lessons learned from other ways of assessing and treating a patient, seen through the lens of hybridity create the environment for the development of a richer, interprofessional identity. As Khalili

et al. [

14] states, a dual identity is formed, professional and interprofessional. Applying this view to the Bhabha concepts, the student understands the roles and values of their profession, but also understands that they can function collaboratively to achieve patient care outcomes. The assessment tools and approach to care planning are richer as a hybrid of all they have learned.

5. Interprofessional Collaboration in Practice

Many studies of student interprofessional experiences indicate they create an understanding of each other’s roles and the value of collaboration [

15]. In the work settings though, research on the success of collaboration and valuing of each professions role in patient care less robust and shows inconsistent results [

16]. What is different in clinical collaborative environments? This is a subject where research is needed however the differences in setting include that in a student setting the student accepts the teacher concepts and it is untested in the reality of the work environment. According to Wenger [

17] mutual engagement and joint enterprise are necessary for a community of practice to form. In a clinical setting the organizational and unit culture as well as historical hierarchy and stereotypes prevent these authentic encounters from occurring in many cases. It is unlikely hybridity and identity development would occur without authentic engagement.

6. Transformative Pedagogy of Fusion

How would education of students in interprofessional learning environments occur based on these concepts? Acknowledging the Third Space encounter and its effect on a student is a transformative view of their education. What we are describing is the transformation of the individual through IP experiences in both the psychological, convictional and behavioral sense [

18].

Health profession students are socialized in their profession with its set of practices, tasks, values, rituals and social hierarchies. Their professors and clinical instructors pass on these cultural markers through didactic instruction and reflection in the clinical encounter. This uniprofessional identity leads individuals to view their profession as different as other identities [

14]. In an interprofessional experience, through the lens of hybridity each student takes their developing professional identity to an encounter with other students. As they encounter the narratives of students or professors of other professions they enter that liminal space where they realize there may be another way of viewing the patient and assessing and caring for that patient.

In terms of Bhabhian theory this is a space where new cultural values and norms can occur, a Third Space. “It is a place where we construct our identities in relation to varied and often contradictory systems of meaning” ([

6], p. 38). How is this transformative for the student? How are they changing? They are changing in terms of their knowledge of the other professions, of a different way to view the plan of care for that patient. They understand, for example, the view of the physical therapist student, and what they might discuss with them related to the patient care. This is the first step to being a collaborative practitioner. They have engaged with other students and have a sense of interprofessional community (

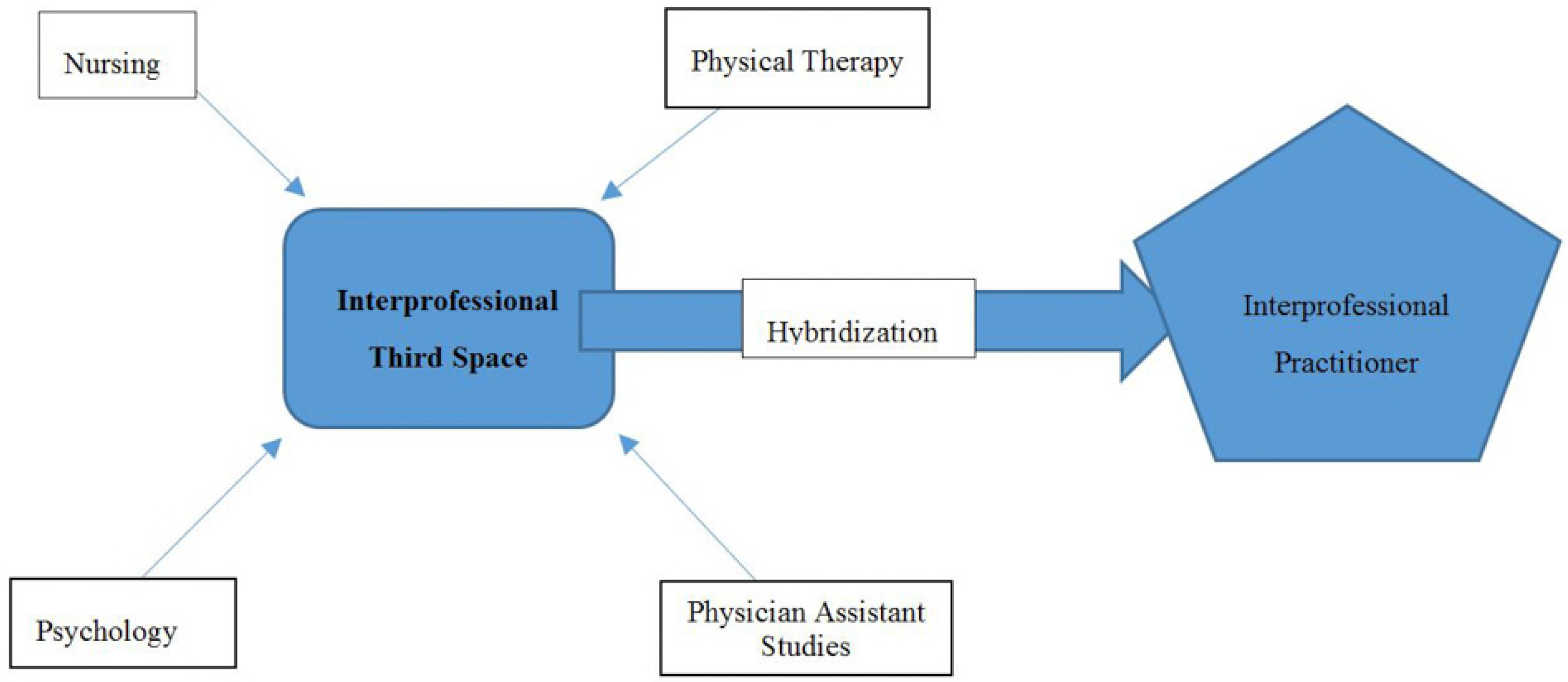

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Process of interprofessional development.

Figure 1.

Process of interprofessional development.

What views are they changing or does nothing change except the knowledge that there is another way? The process of development (See figure) includes engagement between students. Participants stand at the threshold between the previous way of structuring their identity and the new way. During the liminal, or third space experience the normally accepted differences between groups are deemphasized and a spirit of community develops.

7. Rethinking Pedagogy: Creating an Interprofessional Community of Practice

Health profession students are socialized, then into their profession with practices, values, rituals and social hierarchies. Professors and clinical instructors aid in this process through didactic instruction, modeling behaviors and assisting in student reflection on experience. In nursing, Williams and Burke [

19] state the act of caring for patients who are dependent on them for care was voiced as a significant act in student’s identity as a nurse.

As reflection assists in uniprofessional identity development, a pedagogic model leading to the development of an interprofessional identity would also actively guide students in interprofessional settings to reflect on their reactions to discussions that identify professional differences. The naming of what is going; the identification of differences between the professions, in Third Space experiences, aids in the development of hybrid assessments and collaborative techniques based on the new knowledge. The recent approach to nursing education, narrative pedagogy [

20], would be a way to allow for this reimagining of professional identity to develop.

The process requires a structure that allows for engagement and discussion. Understanding professional differences occurs when there is discussion about care revealing different approaches. This would not occur in a traditional didactic classroom, but does when there is mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire; the markers of a community of practice.

Wenger’s [

17] Community of Practice theory of situated learning provides the structure for the development of a third space and hybridity, leading to a clinician who has an interprofessional as well as a professional identity. Structures of learning would include discussion of clinical case studies and interprofessional clinical experiences. Group reflection identifying differing practices and values would lead to hybrid assessment tools and techniques as well as an identity as an interprofessional practitioner.

8. Summary and Conclusions

Interprofessional education is a thought-provoking meeting of students at their professional boundaries. As students of their profession they are unaware of the boundaries and differences until discussions with other students make the differences visible. As Martin Heidegger noted there is something that begins its presence in this setting. Students enter a Third Space where a hybrid development of an interprofessional identity and culture can occur in the right environment. Creating healthcare clinicians who have both professional and interprofessional identities will lead to improved collaboration necessary for caring for the complex patients of today and tomorrow.

If health profession education’s goal is developing health care professionals to act as collaborative partners in the care of patients, the concepts of Third Space and hybridity may provide a key part in the student’s transition to development of an interprofessional identity. To Bhabha, these concepts describe the outcome of the coming together of cultures; the resulting hybrid culture, a part of, but different from the other two. Bhabha evokes cosmopolitanism of the world; the idea that all human beings belong to a single community [

6]. Collaborative healthcare practitioners identify a single community of practice, a community focused on improving the healthcare of individuals.