Abstract

Since the first democratic elections in 1994, South Africa has faced the challenge of creating new cultural capital to replace old racist paradigms, and monuments and museums have been deployed as part of this agenda of transformation. Monuments have been inscribed with new meanings, and acquisition and collecting policies have changed at existing museums to embrace a wider definition of culture. In addition, a series of new museums, often with a memorial purpose, has provided opportunities to acknowledge previously marginalized histories, and honor those who opposed apartheid, many of whom died in the Struggle. Lacking extensive collections, these museums have relied on innovative concepts, not only the use of audio-visual materials, but also the metaphoric deployment of sites and the architecture itself, to create affective audience experiences and recount South Africa’s tragic history under apartheid.

1. Introduction

This paper considers some of the problems to be faced in the arena of culture when a country undergoes massive political change that involves a shift of power from one cultural group to another, taking South Africa as a case study. The new government, formed by the African National Congress (ANC) after the first democratic elections in 1994, fully acknowledged the need to transfer monetary capital. Programs for economic development have been underway, such as educational and up-skilling opportunities, and housing and infrastructure developments. Despite continuing difficulties, there have been dramatic changes, perhaps most obvious in the evolving well-to-do black middle class, even though high unemployment rates and the vicious spread of HIV/AIDS continue to entrench acute levels of poverty.

A challenge that equals the redistribution of wealth is the need to transfer cultural capital to give recognition to those who were long marginalized. A demanding task under any circumstances, this is made all the more difficult in the South African context because it is not considered important by those still struggling with basic issues of survival, who may resent the deployment of resources for what seem to be intangible results. Yet it is critical that racist readings of culture, deeply embedded in the country’s recorded history, should be reshaped if South Africa is to reformulate its long established social hierarchies, which privileged white culture to a degree that almost entirely erased black values. Cultural empowerment of all groups is an essential ingredient for a successful democracy.

In attempts to recover the history of black culture in South Africa, scholars have been energetically engaged in researching the past anew, a process initiated by liberal scholars long before the demise of the apartheid state; but their writings tend to target a limited readership. To reach wider audiences, reshaping the visual histories recorded in public monuments and museums may be a more accessible form of redress.

2. Reframing and Renaming

One way of tackling the issue would be to remove traces of the abhorred oppressor of the past—there are certainly many monuments related to the old regime and its values that spring to mind. But the ANC with its much vaunted policy of inclusivity has chosen not to obliterate all the signifiers of white culture, and there has been remarkably little vengeful iconoclasm. Statues of Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd have been taken down, notably the one in front of the administration buildings in Bloemfontein, where the newly appointed Premier of the Free State, Terror Lekota, not surprisingly found it problematic to contemplate a key architect of apartheid every day as he went to his office.1 After the work’s removal in 1994, President Nelson Mandela warned colleagues to use sensitivity in removing Afrikaner icons, saying “We must be able to channel our anger without doing injustices to other communities. Some of their heroes may be villains to us. And some of our heroes may be villains to them” [1].

Few have been as generous as Mandela, but some have a pragmatic view that ascribes new meaning to old monuments. At a meeting in central Pretoria where the Kruger monument still stands, Daniel Mmethi said he thought the statue of the old Boer Republic president should stay. “It reminds me of victory,” he said. “We won. That's what matters” [1]. And gradually new sculptures are joining the old to celebrate more recent heroes: not surprisingly there are many of Mandela, forceful or formal, even in his famous dance routine.2 More unusual is the sculptural group in honor of South African recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize by Claudette Schreuders (Figure 1), installed at the Cape Town waterfront in 2005, where Mandela takes his place alongside images of Albert Luthuli, Desmond Tutu and F.W. de Klerk; despite the traditional valorizing medium of bronze, the artist’s distinctive style projects an appealing sense of vulnerability rather than authority.

Figure 1.

Commemorative sculptures of Nobel Peace Prize winners, Luthuli, Tutu, De Klerk and Mandela, by Claudette Schreuders, Cape Town waterfront (author’s photograph).

Figure 1.

Commemorative sculptures of Nobel Peace Prize winners, Luthuli, Tutu, De Klerk and Mandela, by Claudette Schreuders, Cape Town waterfront (author’s photograph).

Mandela’s significance in the political transformation of South Africa has led to a certain amount of confusion, as so many institutions now carry his name, not only new buildings, such as the museum dedicated to him in Mthatha, and the bay and municipality of Port Elizabeth, as well as the soccer stadium built there for the FIFA World Cup, but the many old ones that want to be rechristened in his name. A case in point is the erstwhile King George VI Art Gallery in Port Elizabeth, originally named to commemorate the royal visit to South Africa in 1947, which has relinquished its colonial ties in its renaming as the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum. This is part of a growing trend to replace the names of buildings, as well as towns and streets in South Africa, some of the erased names obviously colonial or linked to apartheid, but others seemingly quite innocuous. The new, mainly African names signal change in a very public fashion, although they can be more confusing than celebratory for visitors, as changes are ongoing and not always updated on maps. Some cities, such as Pretoria, have devised an ingenious compromise, showing the old name in cancelled form below the new, a pragmatic strategy that, possibly unintentionally, overtly displays the process of transformation.

A more subtle initiative is found in a number of monuments which have been re-inscribed with fresh meanings in the service of the new South Africa. War memorials provide an interesting example. Like many colonies that fought for the British Empire, South Africa erected memorials after World War I, and in Johannesburg this took the form of a cenotaph based on the famous example in London’s Whitehall designed by Edward Lutyens. While many of these monuments were later given a broader brief to include the Second as well as the First World War, the one in Johannesburg was rededicated yet again in 1996 to a far wider purpose. Its new inscription reads:

The City of Johannesburg honours all those who made the supreme sacrifice in all wars, battles and armed struggle for freedom, democracy and peace in South Africa.

It thus includes those who took part in the internal conflicts of the later twentieth century, although it is left to viewers to decide whether it embraces those who fought on both sides of the battle for freedom. In similar vein, the Johannesburg memorial to the Rand Regiments that fought for Britain against the Boers in the South African War, now also commemorates their former enemies, and indeed all who died as a result of the conflict, whether combatants or not:

On 10 October 1999 this memorial was dedicated to the memory of men, women and children of all races and all nations who lost their lives in the Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902.

But the nearby Museum of Military History, which is responsible for the care of this monument, still focuses chiefly on European wars and white heroes: African men were not allowed to bear arms, and took part only in menial positions that were seldom documented. They were even more rarely honored for the part they played, although the Museum has managed to uncover a few examples, and has created small exhibits on Lucas Majozi, imprisoned at Tobruk, and Job Maseko, who was a stretcher bearer at El Alamein, both of whom received medals for bravery.

As part of the northern national museum group, the Museum of Military History has taken a new name, Ditsong (a Sotho word meaning culture), and has redefined its mission. But the focus on World War armaments still dominates the museum exhibits, even in the large additional wing that has recently been built. The new memorial vestibule, too, focuses on international rather than internal conflict, commemorating Delville Wood, the site of the greatest South African losses in World War I. The exhibitions have been somewhat expanded, with the Border Wars of the apartheid era inserted alongside the World Wars, and some rather minimal exhibits about conscientious objectors, white men who refused to fight in the South African Defence Force because they did not want to participate in the border wars or support the quelling of internal township unrest, although they faced lengthy imprisonment as a result. There has also been a rewording of labels to eliminate offensive terms such as ‘terrorists’, now referred to as ‘freedom fighters’. But very little attention is given to the achievements of such soldiers, perhaps in part because there are few artifacts to exhibit, but no doubt also because the state of civil war is still too recent and raw to be viewed with historical detachment, and there is some awkwardness about how to represent the opposing sides. Only a single scant display case is devoted to Umkhonto We Sizwe, the military arm of the ANC (Figure 2). It focuses on the uniform worn by Joe Modise, the former Commander in Chief, who was to become Minister of Defence in the new government. In its unstated irony, the exhibit captures something of the complexity of the South African story.

Figure 2.

View of the Umkhonto We Sizwe display, Ditsong Museum of Military History, Johannesburg, and detail of Modise’s uniform. (author’s photographs).

Figure 2.

View of the Umkhonto We Sizwe display, Ditsong Museum of Military History, Johannesburg, and detail of Modise’s uniform. (author’s photographs).

3. Reconfiguring Cultural Exhibits

It is no easy task for museums to change ideological focus when their collections and exhibitions were initiated under colonial rule and shaped under apartheid. Perhaps stimulated by the work of artists who critiqued apartheid oppression, art galleries led the way in revising museum culture, as some enlightened curators started shifting the focus of collections, and mounted exhibitions that began to redress the omissions of South African art history from the 1980s.3 A notable example was The Neglected Tradition at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1988, when Director Christopher Till sought the services of an independent curator Steven Sack, whose experience in non-government initiatives, particularly the African Institute of Art at Funda in Soweto, gave him the knowledge and insight to undertake a large survey exhibition of the work of black artists who had received little attention in the past [2]. Acquisition policies also changed direction to embrace works by these artists for collections, gradually forging a new canon of South African art [3]. At the same time, galleries began to reconsider the range of works they were acquiring, expanding the parameters of their collections to include historical ethnographic African objects that challenged Western definitions of art, which focused on easel paintings and sculptures in marble and bronze, and introducing artifacts such as beadwork and carved headrests that unite design skill and symbolism with functionality (Figure 3). A major early case was Christopher Till’s negotiation of the permanent loan of the Brenthurst collection of African art, examples of which were included on Images of Wood at the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1989 [4], and which later formed the basis of innovative exhibitions focused on historical African art, such as Art and Ambiguity: Perspectives on the Brenthurst Collection of Southern African Art (1991) [5], where the gallery, which did not yet have a curator in the area, drew on the expertise of academics such as Anitra Nettleton in Art History and Karel Nel in Fine Arts, both at the University of the Witwatersrand, to document and display the artifacts.

Figure 3.

Display of African headrests, Johannesburg Art Gallery. Display under the direction of Karel Nel. (author’s photograph).

Figure 3.

Display of African headrests, Johannesburg Art Gallery. Display under the direction of Karel Nel. (author’s photograph).

Yet it must be acknowledged that the overriding ethos of an art museum is in itself western, signaled even in its architecture, and packing away European art treasures does little to shift this perception. Yet that is what has been done. At the Johannesburg Art Gallery, for example, we no longer see its fine Pre-Raphaelite works on display, and the gallery was able to send a travelling show of its Impressionist paintings, Da Corot a Monet, to Italy in 2001 because they no longer had a place on the walls.4 Instead, the gallery’s exhibitions have represented a far wider understanding of visual culture that includes contemporary works by African artists as well as historical artifacts, which now take their place alongside more conventional paintings and sculptures in the gallery, reflecting enlivening cross-cultural exchanges; an interesting example is as an exhibition that set up visual relationships between historical African works and those produced by black artists working in a western tradition, Views from Within, by the curator of African art, Nessa Leibhammer (see [6], p. 11). There have also been exhibitions that challenge the usual parameters of art galleries by introducing issues of social history, such as two at Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town: Strengths and Convictions: The Life and Times of the South African Nobel Peace Prize Laureates, curated by Gavin Jantjes in 2009 [7], and Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushman, curated by Pippa Skotnes in 1996 [8], which displayed life casts and Khoisan artifacts more often seen in ethnographic museums.

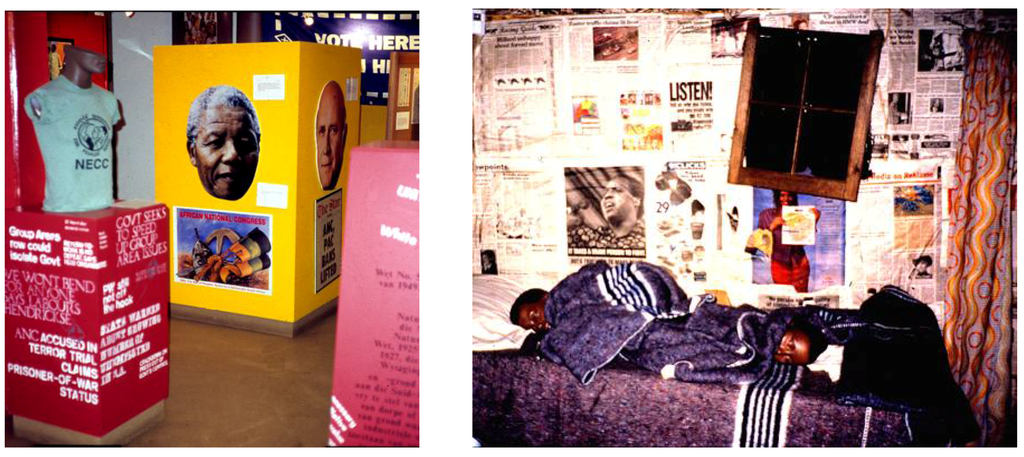

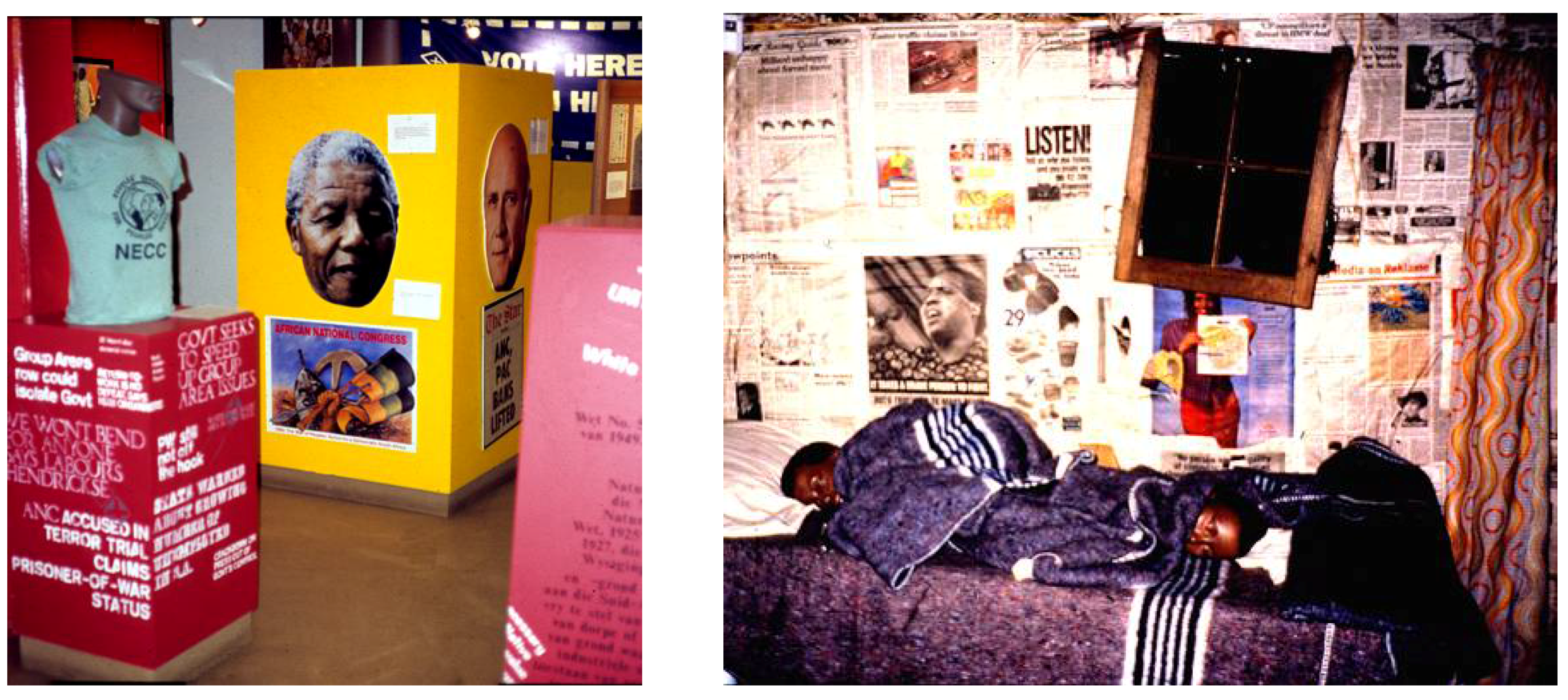

There is some irony then that, when the reconceptualized Africana Museum in Johannesburg opened as Museum Africa in the 1990s, most of its ethnographic treasures were packed away in favor of a more contemporary emphasis, such as an exhibit on the first free elections (Figure 4), and displays that focused on urban workers rather than historical artifacts, developing new exhibition strategies, described in detail by Annie Coombes ([9], pp. 174–200). Alternate objects for exhibitions were acquired in unusual ways: a squatter camp display, for example, involved the purchase of actual shanties from their owners, which were then rather disconcertingly re-inhabited by life-like models in the museum (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

First free election exhibit, and interior of shack dwelling on display, Museum Africa, Johannesburg (author’s photographs).

Figure 4.

First free election exhibit, and interior of shack dwelling on display, Museum Africa, Johannesburg (author’s photographs).

It seems odd that historical works which would surely be a source of cultural pride for African visitors were not given prominence, and it is interesting to speculate about the reasons for this decision. Ethnographic research had been very much the domain of white academics, and related exhibits had relegated African culture to a timeless past, suppressing cultural change, a mindset that could be perceived as demeaning by contemporary black audiences. The intention to shift such an approach seems to be signaled also in the dropping of the old name, Africana Museum, which emphasized the study of Africa as passive object, to the more active implications of Museum Africa. In the context of South Africa, there is another factor to be taken into account—the complicity of academe in the ethnographic definition of tribal identities that were deployed under apartheid to divide African peoples into discrete homeland units. The assignment of artifacts to different tribal groups seemed to endorse such differences, in conflict with a more cohesive Pan-Africanism that has been fostered in the wake of the 1994 elections, as in President Thabo Mbeki’s promotion of the concept of an African Renaissance. Yet there is tension between different approaches, and today many Africans themselves embrace tribal categories as a valid form of identity; it is also notable that the recent efflorescence of popular ‘native’ villages created for tourist consumption stresses tribal ethnicity rather than a more unified sense of Africanness [10].

A more direct and pragmatic reason for the shift from ethnographic displays at Museum Africa might be the immediate appeal of contemporary displays to viewers unfamiliar with museums. It has to be acknowledged that drastic shifts are necessary to reach such audiences. After the opening in the 1990s of the nearby Worker’s Museum, which preserves the sub-human accommodation of migrant workers, administrator Lucky Ramatseba told me that he was faced with negative responses from African visitors who were outraged, not so much by the appalling conditions, but because the hostel had been turned into a museum rather than being used to provide shelter for the homeless. Similarly, when it was proposed in the mid-1990s to build a monument at the site of the 1955 signing of the Freedom Charter in Kliptown, Johannesburg, angry residents of the poverty-stricken area demanded new housing instead. The Kliptown Urban Renewal Project was launched and the 2005 square, renamed for the longstanding ANC leader, Walter Sisulu, who died in 2003, is a site of urban renewal, accommodating an upmarket hotel and convention centre, as well as a conical monument commemorating the charter, which houses an eternal flame of freedom. While it is uncertain how much residents have gained from the development, it has become a standard stop on township tours.

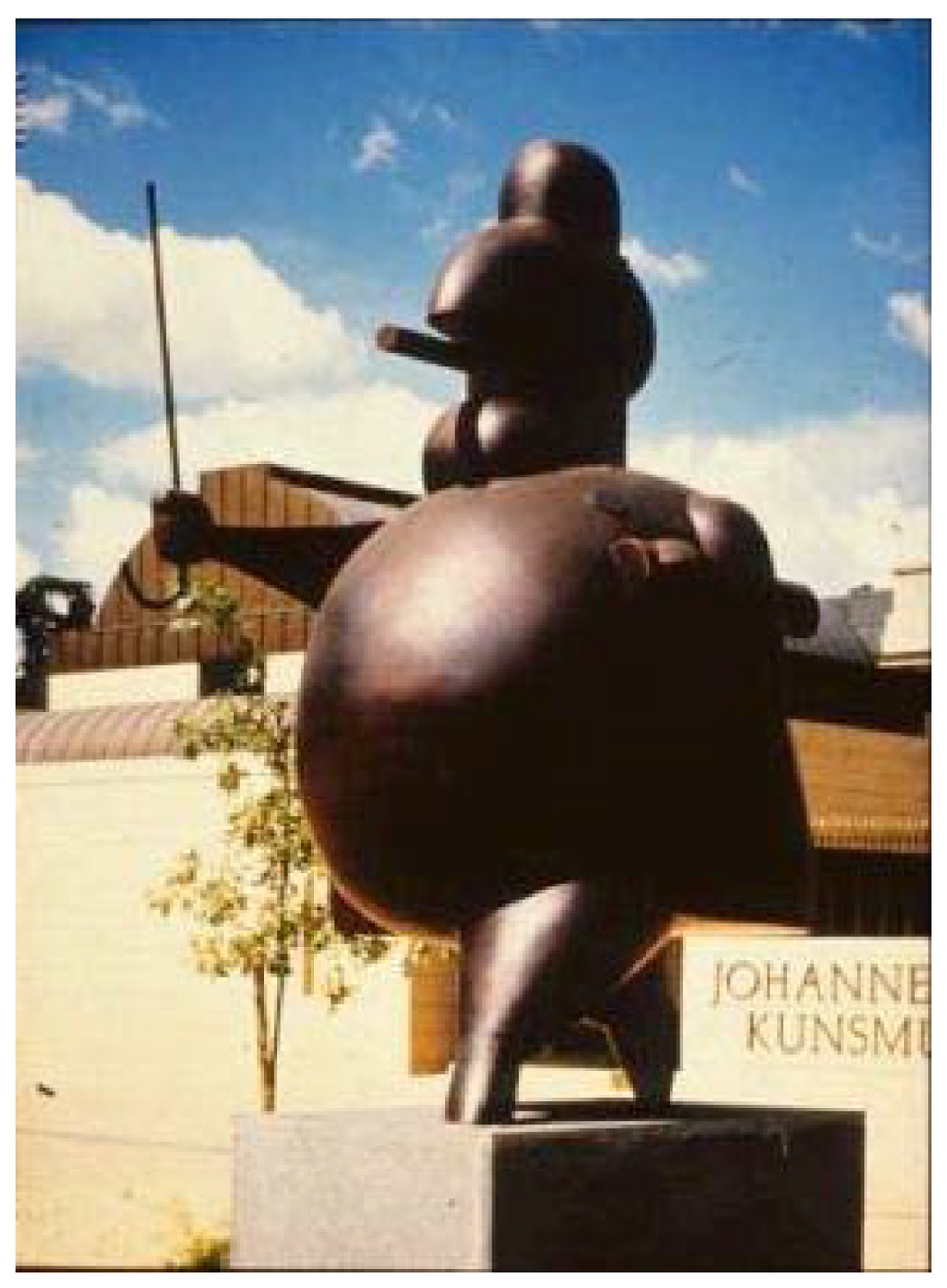

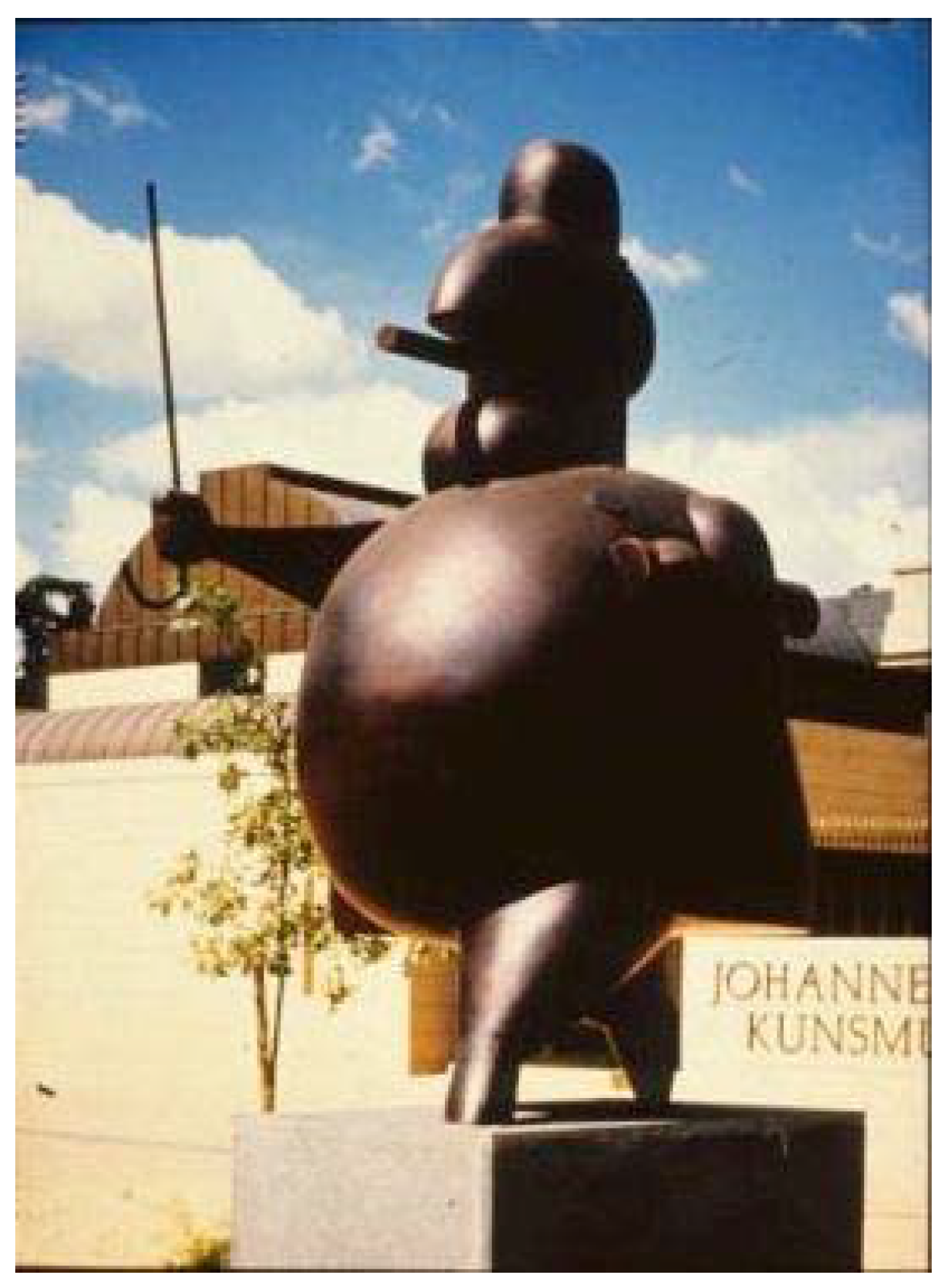

Understanding of art works also shifts with new audiences: a stainless-steel construction by sculptor Ian Redelinghuys outside the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, whose abstract forms proclaimed the gallery’s contemporary interests, is on occasion happily used by small visitors as a jungle gym. Interpretations also vary, such as two opposing comments on Bruce Arnott’s witty caricature of a business tycoon, installed outside the Johannesburg Art Gallery in celebration of the city’s centenary in 1986 (Figure 5)—one black respondent told the then director of the gallery, Christopher Till, “Come the revolution, this will be the first to go”, while a second remarked “Come the revolution, this will be me!”

Figure 5.

Bruce Arnott’s Citizen (1985–86) in the forecourt of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (author’s photograph).

Figure 5.

Bruce Arnott’s Citizen (1985–86) in the forecourt of the Johannesburg Art Gallery (author’s photograph).

The humorous aspect of the contradictory positions of revolutionary and reactionary responses aside, the remarks highlight the ambiguities of interpretation and the challenges set for establishing new cultural parameters. Yet, while diverse attitudes and misunderstandings may abound, it nonetheless seems a curious aberration that, in both Johannesburg’s museum and art gallery, many of the finest works of black and white cultural groups in their respective collections have been concealed, with a singular focus on new directions at the expense of old.

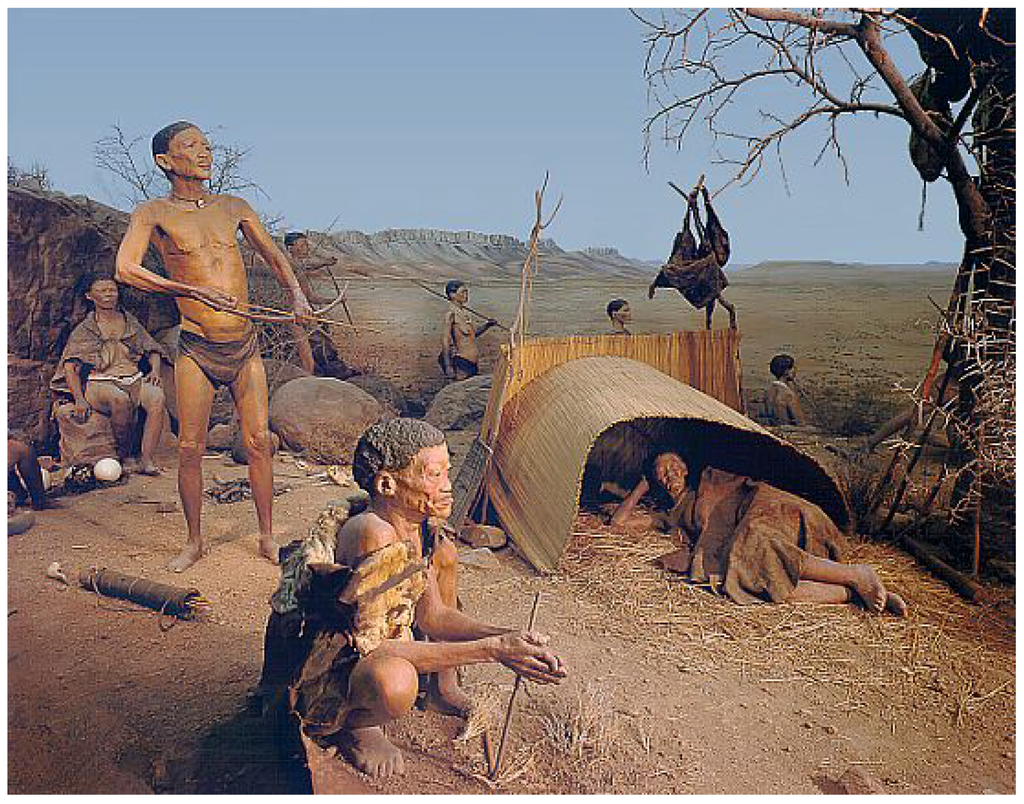

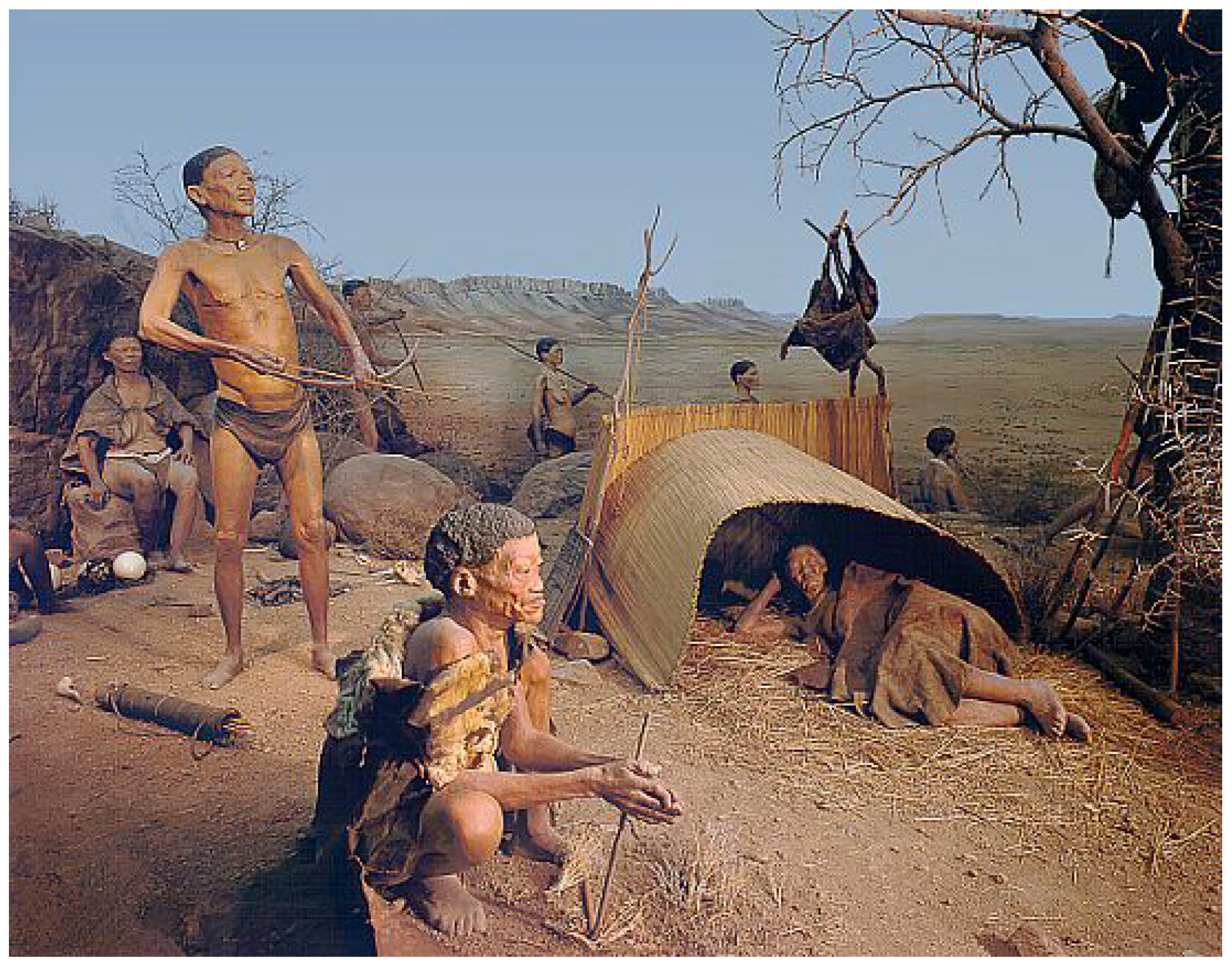

A perhaps even more extreme make-over is found in some of Cape Town’s institutions. The Social History Museum, which had since 1960 represented European settler history (together with some antiquities), has set that material aside and been redeveloped as the Slave Lodge Museum—the original function of the building it occupied. White culture had been separated from ethnographic material: as John MacKenzie expresses it, “Natural history and ethnography went together as representative of the African environment—cultural history, whether of whites or of ancient cultures, was something quite distinct” ([11], p. 115). The mingling of African culture and nature at Iziko South African Museum had been typified by its notorious so-called ‘Bushman’ diorama (Figure 6), where early Khoisan peoples of the Cape were represented in a way not dissimilar to nearby animal dioramas.

Figure 6.

So-called ‘Bushman’ diorama, Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town (author’s photograph).

Figure 6.

So-called ‘Bushman’ diorama, Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town (author’s photograph).

After attempting to redress the problem with a number of contextualizing exhibits, the decision was ultimately reached by the museum to dismantle the diorama in favor of one that celebrated the much admired rock art their artists created, shown together with video interviews with people of Khoisan heritage. But other older presentations using display figures are still in place at the museum, and attempts to intervene in a postmodern way to provide contemporary commentary, by suspending photographs of urbanized Africans in front of glass cases housing rural figures with artifacts that illustrate ‘traditional’ lifestyles, has not been met with great success.

4. Site-Specific Commemorative Museums

At the inauguration of Robben Island as a heritage site in 1997, the need for reform was addressed by President Nelson Mandela himself in his opening speech, when he castigated museums for their lack of progress, clearly referring to Iziko South African Museum when he asked: “[C]an we afford exhibitions in our museums depicting any of our people as lesser human beings, sometimes in natural history museums usually reserved for the depiction of animals? … Can we continue to tolerate our ancestors being shown as people locked in time?” ([12], p. 2). Robben Island certainly affords a different approach: the former prison on the island where he had been an inmate is one of the many new heritage projects developed after the transition to democracy. As opposed to the examples discussed previously, which represented change within existing galleries and museums and was largely driven by the institutions themselves, this project was an early instance of a number of new initiatives, driven by the government, through the Ministry of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology. As stated in the Foreword of the proceedings of a seminar at the University of Zululand in October 1998, considering the re-interpretation of the 1838 Battle of Blood River/Ncome, and presided over by Minister L. P. H. M. Mtshali:5

A motivating factor for the institutionalization of all the legacy projects: the Samora Machel Memorial, the Ncome Monument, the Nelson Mandela Museum, the Women's Memorial, the Khoisan Project, the Inkosi Albert Luthuli Project and Freedom Park, was to fill the gaps in the South African cultural heritage scenery, in which one finds an overrepresentation of colonial history and underrepresentation of especially the history of indigenous people.([13], p. 3)

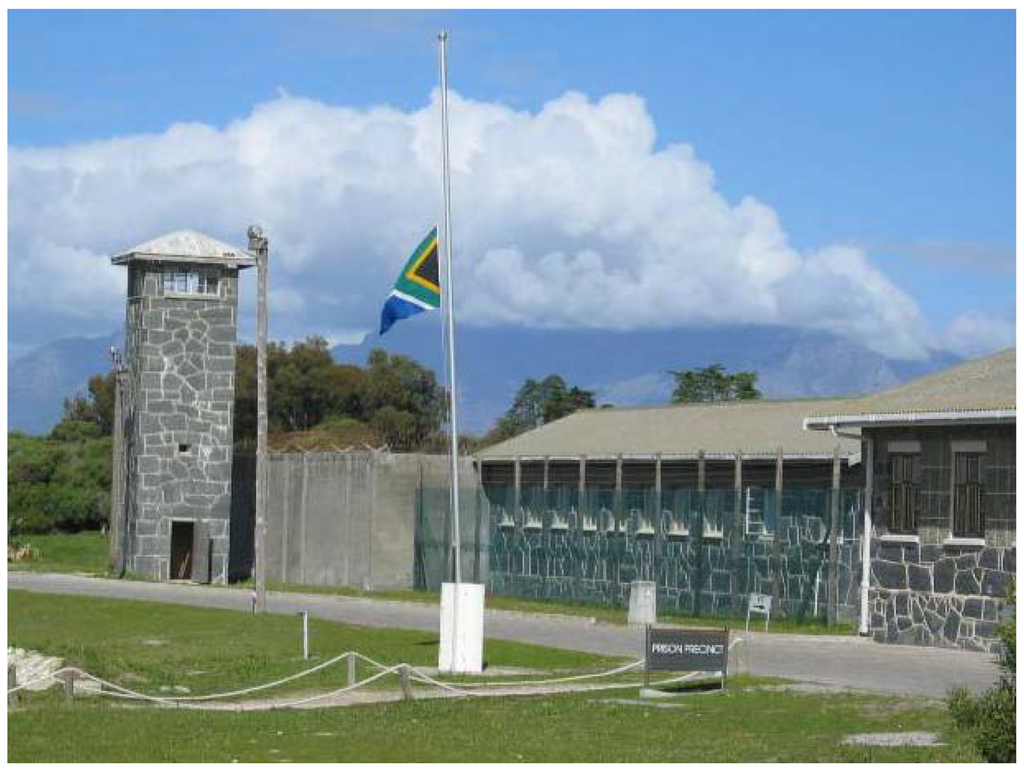

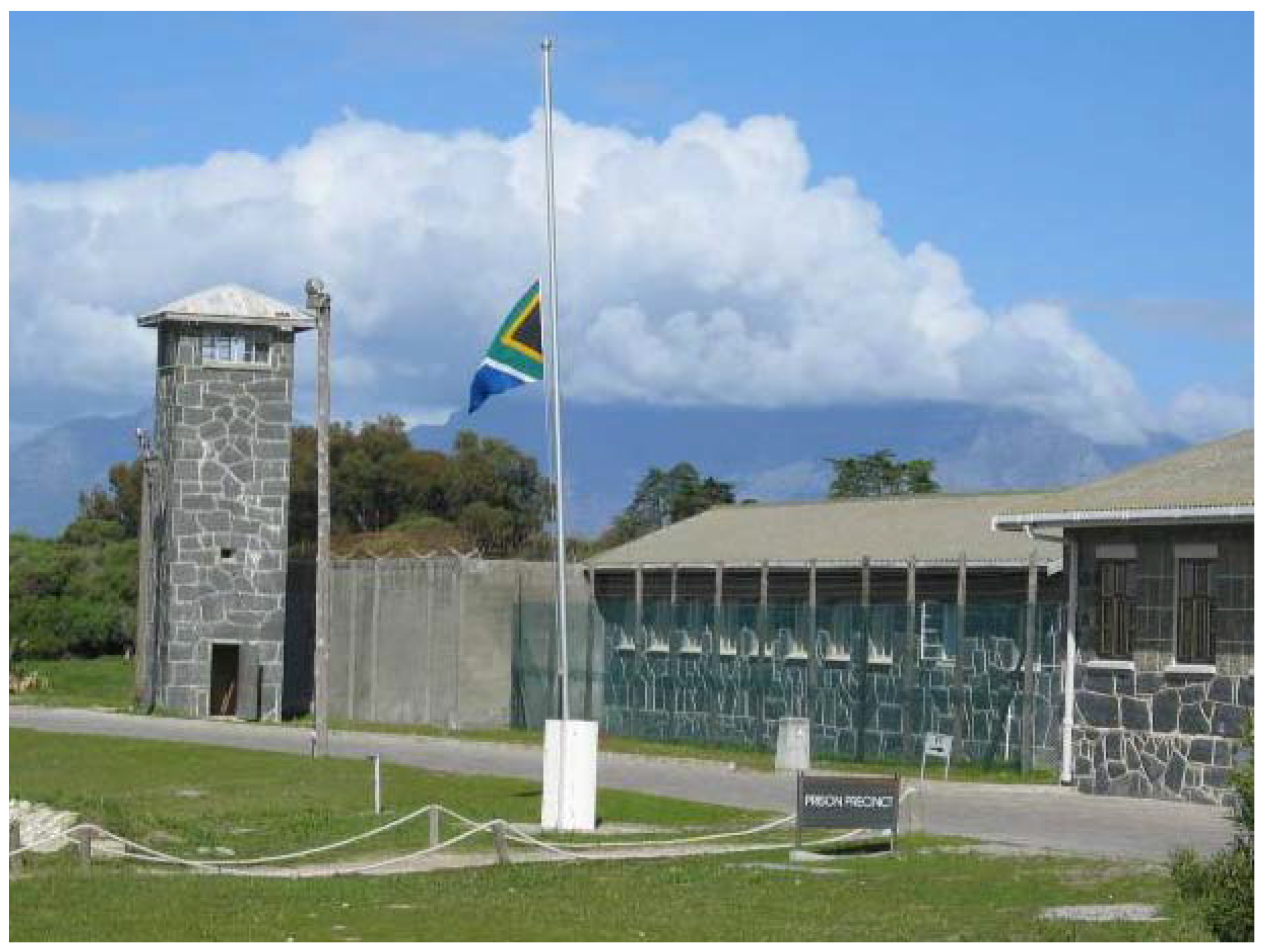

At Robben Island, the site in itself acts as museum and visitors are ferried to the island, then driven by bus to view different buildings and the infamous B Block, where Mandela was held after being sentenced to life imprisonment for treason in 1964 (Figure 7). Uniquely, the guides at Robben Island are former inmates, a strategy that can provide affective insights for visitors, although this is dependent on the skill of the individual. There has been relatively little development of the site as a museum, or helpful didactic interventions. While there is minimal reference to the island’s ecology and to earlier stages of its history, there seems to be undue reliance on visitors arriving with an awareness of Robben Island’s notorious past as a place of political incarceration, and there is some ambivalence in its overall intentions: visitors may reach their own conclusions as to whether it is predominantly a place that signifies the affliction of imprisonment or triumph over hardship. Only the departure point on the Cape Town waterfront, the Nelson Mandela Gateway opened in 2001, has been lavishly developed as the reception point for what is primarily a tourist excursion, too expensive for working class South Africans.

The dependence on the site at Robben Island is a notable aspect of a number of new museums established in post-apartheid South Africa. By being built on significant historical sites of the Struggle, they memorialize past events and acknowledge their importance. In Gauteng province two such institutions on key sites are the Sharpeville Human Rights Precinct, near Vanderbijlpark, a memorial opened by Nelson Mandela in 2002, which was expanded by the addition of an Exhibition Centre, initiated by the Sedibeng District Municipality in 2010 at the time of the Sharpeville massacre’s fiftieth anniversary, with funding from the government’s Neighbourhood Development Programme Grant; and, secondly, the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum in Soweto, which opened in 2002, funded by the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism and the Johannesburg City Council. The Sharpeville massacre occurred in 1960 when the South African government was so intent on pursuing its policy of apartheid that it broke away from the British Commonwealth to become an independent republic. At the time, there were renewed demonstrations against the legislation that controlled the movement of African people and required them to carry pass books. At Sharpeville township, police fired on a crowd of unarmed protestors, killing 69. The ensuing government clamp-down included the banning of the ANC. Fifteen years later, it was a mass demonstration by schoolchildren in Soweto against the enforcement of teaching in the hated language of Afrikaans that sparked violence that led to hundreds of deaths, including that of Hector Pieterson. The date of the first demonstrations, 16 July 1976, is still seen by many as the flashpoint that triggered escalating unrest that would ultimately lead to the downfall of the apartheid government, although it took nearly another fifteen years, and was ultimately achieved by negotiation and constitutional change rather than outright civil war.

Figure 7.

View of B Block where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island, Cape Town (author’s photograph).

Figure 7.

View of B Block where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned on Robben Island, Cape Town (author’s photograph).

Neither of these institutions has sufficient objects to constitute what might be thought of as a collection, and they have had to be ingenious in finding alternative ways to tell their stories. At the place in Soweto where the first clash between schoolchildren and the police occurred in 1976, a memorial like a grave was built, together with a huge image of the iconic press photograph by Sam Nzima of the death of Hector Pieterson, remembered as the first victim (Figure 8). In support of this, the red-brick museum tells the story of the Soweto Uprising, largely through video footage, some historical, some recorded for the exhibition. Only a few damaged banners and school desks provide ‘authentic’ artifacts. But the site itself can be considered an artifact and this has been fully exploited. For example, a living line of planted grasses leads from the museum entrance to the exact spot of the first confrontation. Inside the building there is an ingenious use of windows, often considered a distraction in museums: as well as some opening into interior courtyards with memorial functions (Figure 9), there are a number on exterior walls which offer views of the different sites that were part of the events of the Uprising, and texts are inscribed on the glass to identify them for viewers, transforming them into part of the museum display.

Figure 8.

Memorial with photograph by Sam Nzima at the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, Soweto (author’s photograph).

Figure 8.

Memorial with photograph by Sam Nzima at the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, Soweto (author’s photograph).

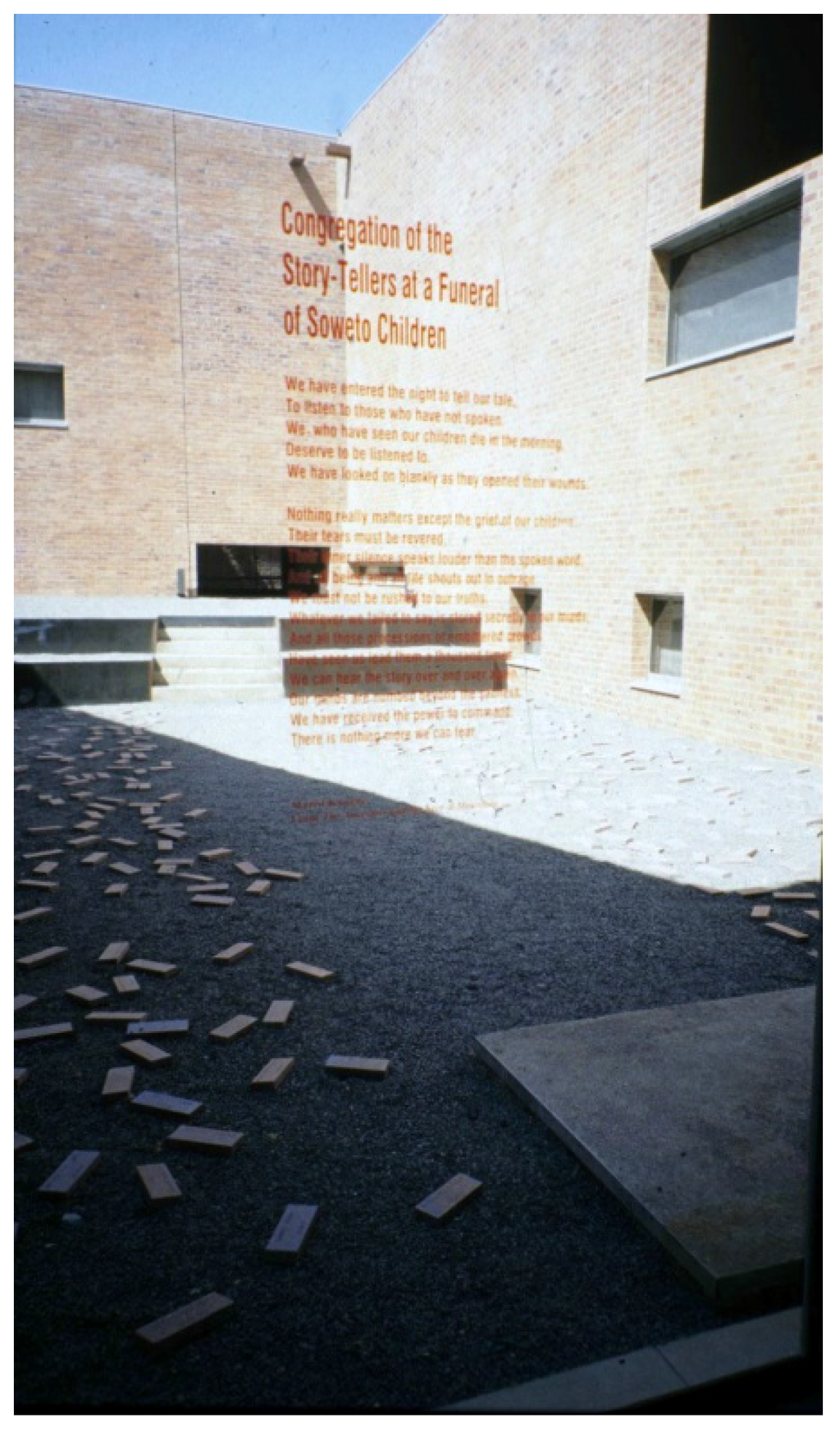

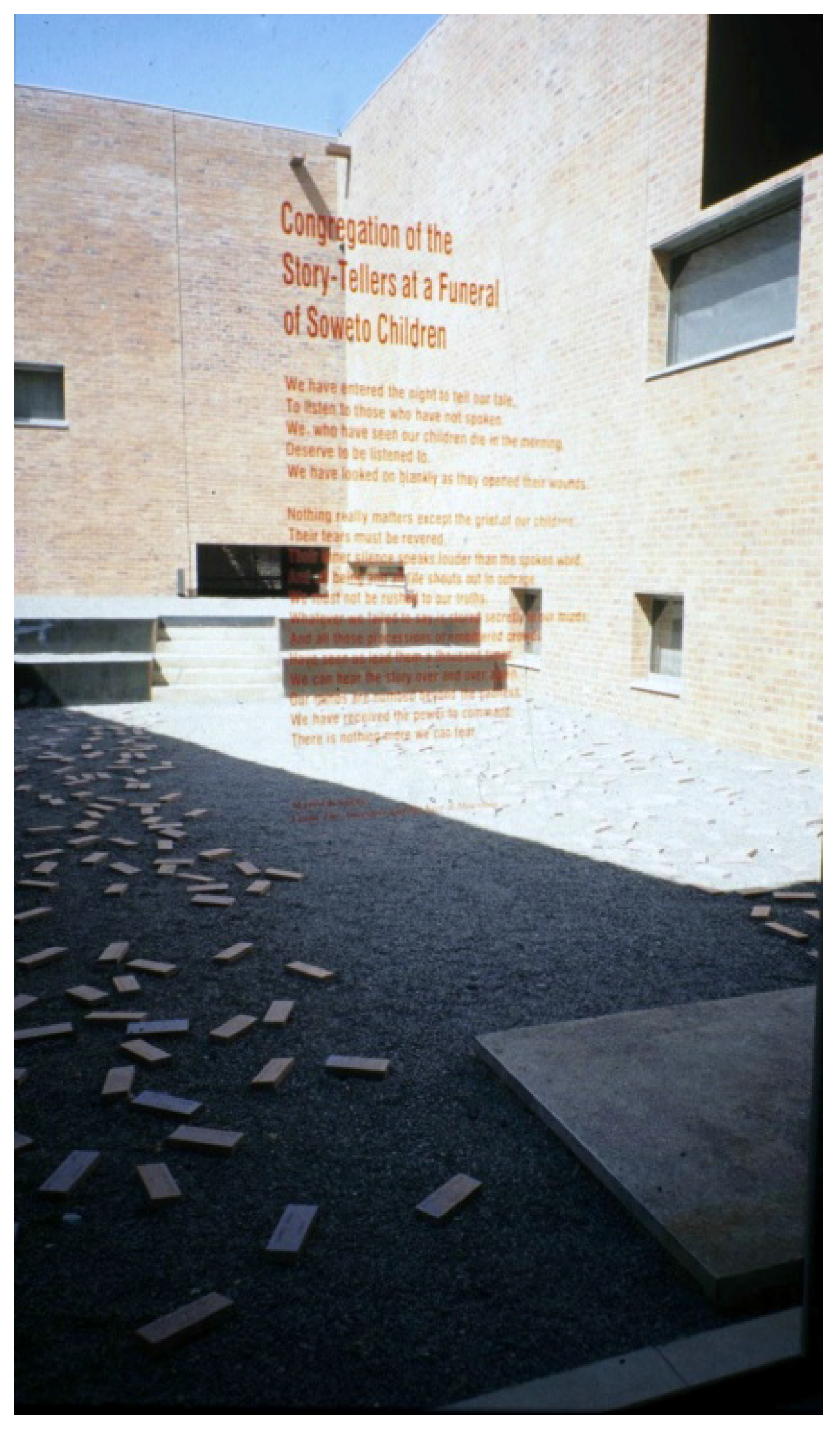

Figure 9.

Window opening onto a memorial courtyard, with scattered bricks inscribed with the names of victims of the Soweto Uprising, Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, Soweto (author’s photograph).

Figure 9.

Window opening onto a memorial courtyard, with scattered bricks inscribed with the names of victims of the Soweto Uprising, Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, Soweto (author’s photograph).

At Sharpeville, the commemorative aspect is dominant, with a pylon gateway, reminiscent of Egyptian funerary temples, leading from the site where the protest took place into a memorial garden (Figure 10). It houses 69 pillars to honor the dead, each inscribed with a victim’s name. A line in the pathway links the site of confrontation with a memorial wall at the far end of the garden, a similar concept to the line of grasses at the Hector Pieterson Memorial in Soweto, although in this case it carries water, a universal symbol of the renewal of life. More specific to South Africa’s new museums is the red brick used for the precinct and the adjoining exhibition center, a distinctive feature that links many of these projects.

Figure 10.

Entrance to the memorial garden at the Sharpeville Human Rights Precinct and Exhibition Centre (author’s photograph).

Figure 10.

Entrance to the memorial garden at the Sharpeville Human Rights Precinct and Exhibition Centre (author’s photograph).

Again there are few artifacts to tell the story of Sharpeville, and assemblages of posters and other ephemeral material in the Exhibition Centre has to suffice. As at the Hector Pieterson Memorial there are also inscribed windows, in this case with a memorial function rather than views of the locale. An innovative installation is a print portfolio specifically commissioned to commemorate Sharpeville. Creative work does not depict history literally, but can be highly evocative and prompts viewers to experience something of the emotional dimensions of the event.

5. The Apartheid Museum

The Apartheid Museum that lies between Soweto and Johannesburg, which opened in 2001, had an unusual inauguration, proposed by a business team as a supposedly civic-minded gesture in support of their application for a gambling license to build a casino in the vicinity (for an extensive description of the museum and its development, see [12], pp. 192–201, [14]). Although there were delays in carrying out this promise after the license was granted, ultimately funding was provided for the building of the museum, designed by architects Mashabane Rose, and the contracting of historians, chiefly from the University of the Witwatersrand, to devise the exhibition program under the directorship of Christopher Till.6 The fact that the museum sits alongside such odd bedfellows as the casino and the adjacent Gold Reef City theme park does raise questions about the intended audience for the museum.

The approach by road from the other side of the museum is happily free of such commercial associations. A curving curtain wall of stone evokes indigenous building, such as the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, and it hugs a low hillside replanted with veld grasses. The entrance, on the other hand, displays the use of the familiar red brick that has become so popular for South Africa’s new museums. Here it forms a severe exterior reminiscent of high prison walls, the first hint that the architecture itself is a crucial part of the affective experience for the visitor. Concrete shafts tower over the walls (Figure 11), carrying metal letters that spell out the principles of the new constitution which proclaim a more affirmative message—Democracy, Equality, Reconciliation, Diversity, Responsibility, Respect, and Freedom.

Figure 11.

Pillars of the constitution at the entrance to the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Figure 11.

Pillars of the constitution at the entrance to the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

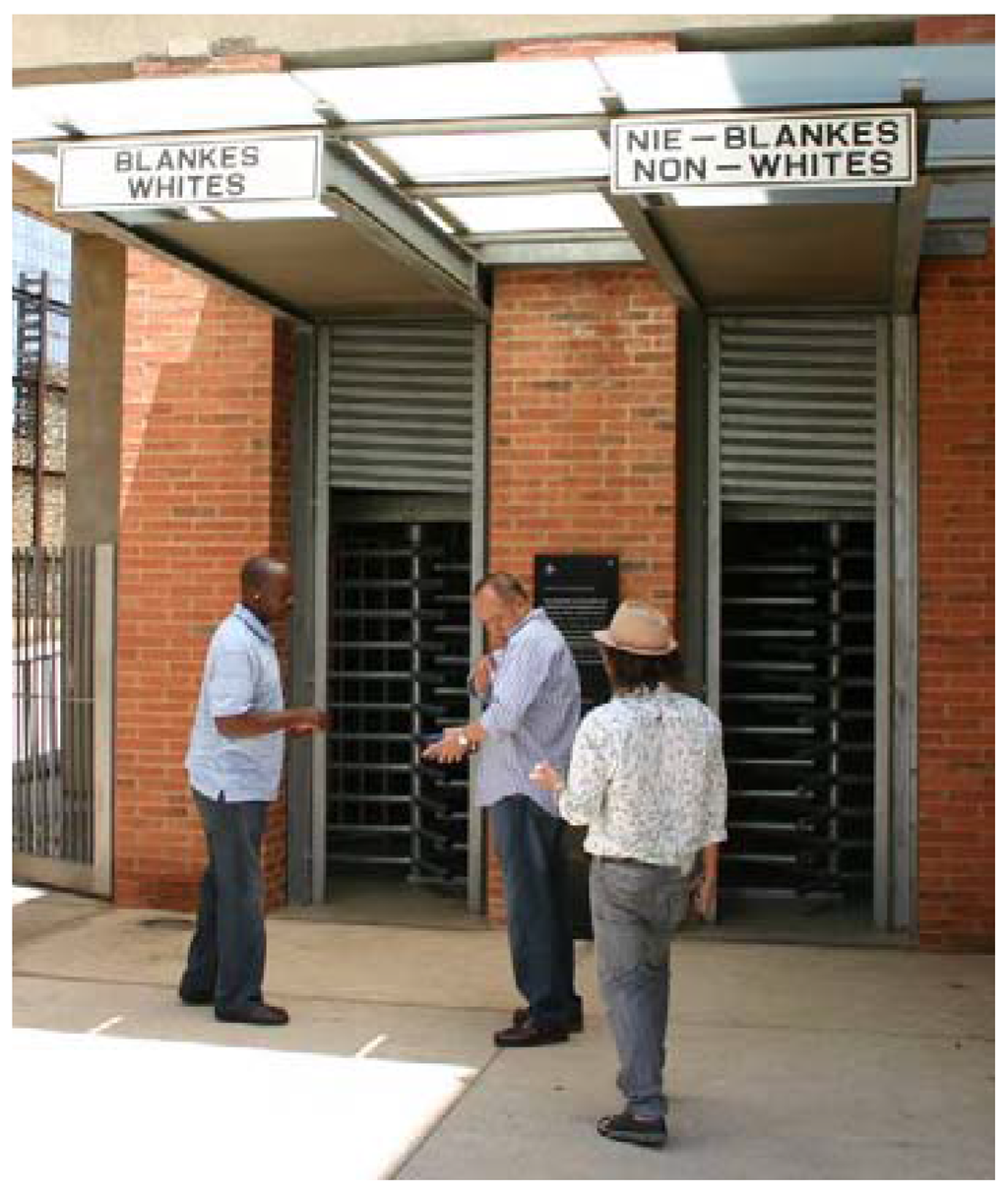

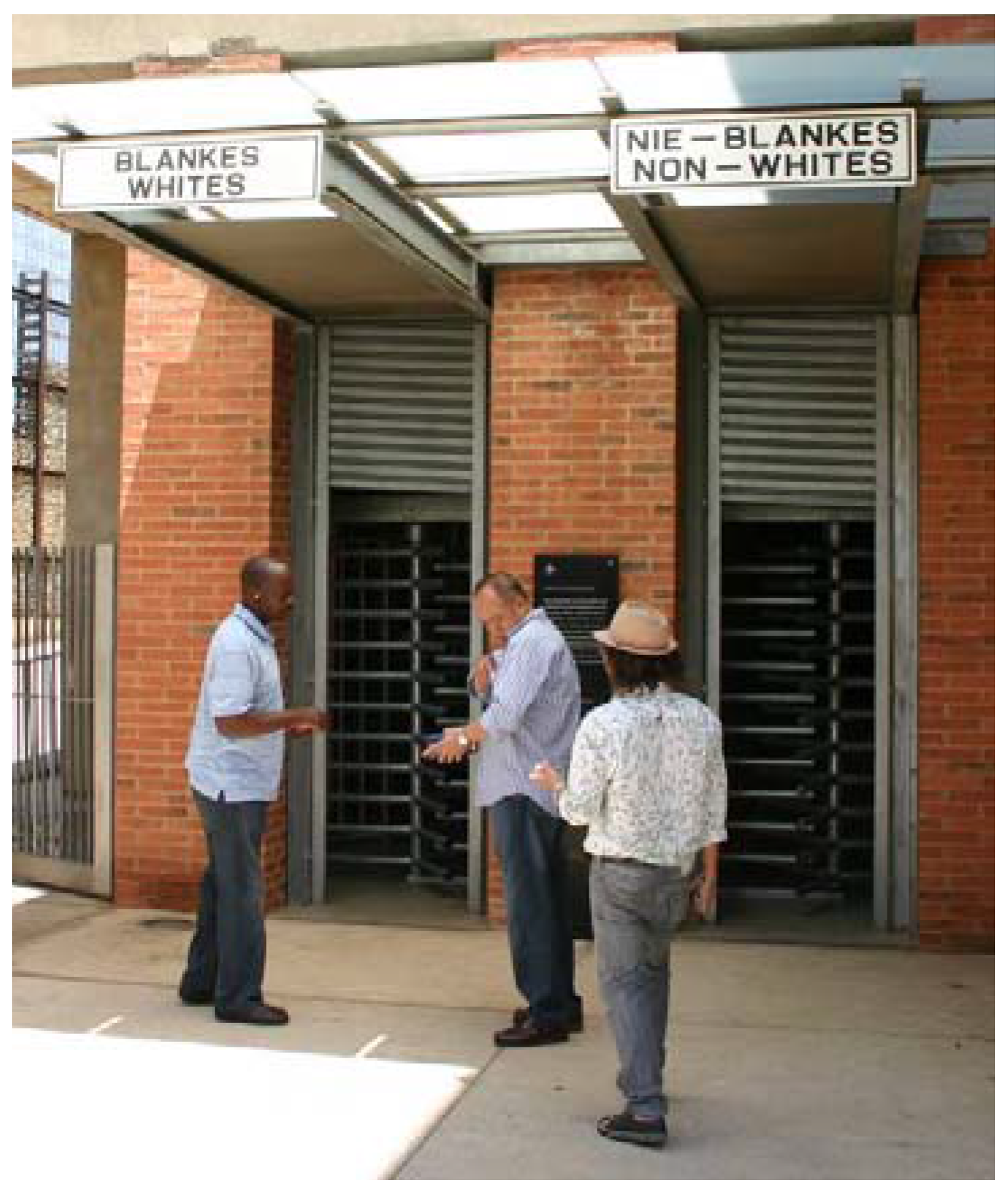

Borrowing an idea from the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, the Apartheid Museum issues visitors with passes that arbitrarily assign them not an individual identity but a racial group—black or white—which dictates which entrance they must use to go into the museum—labeled White or Non-White in old apartheid terms (Figure 12).

Once through the turnstiles, themselves giving a feeling of regulation and control, visitors find reminders of apartheid’s perfidious racism that match the group to which they were assigned. Housed in industrial wire cages reminiscent of prison bars, which line the entrance corridors, are enlarged simulations of the identity documents used to distinguish racial categories—African on one side, European on the other, with the ambiguous category ‘colored’, referring to those of mixed race, inhabiting the barrier of cages between them. Further underlining the ethnic division, ubiquitous signs that served to keep races apart—some of the museum’s few actual artifacts of apartheid—hang overhead, adding to the ominous feeling of the dark passageways with their bleak message of a divided society. At the far end the visitor confronts a huge photograph of the classification board that decided the fate of each applicant—whether he or she would have a life as privileged white or oppressed black.

Figure 12.

‘White’ and ‘Non-White’ entrances to the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Figure 12.

‘White’ and ‘Non-White’ entrances to the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

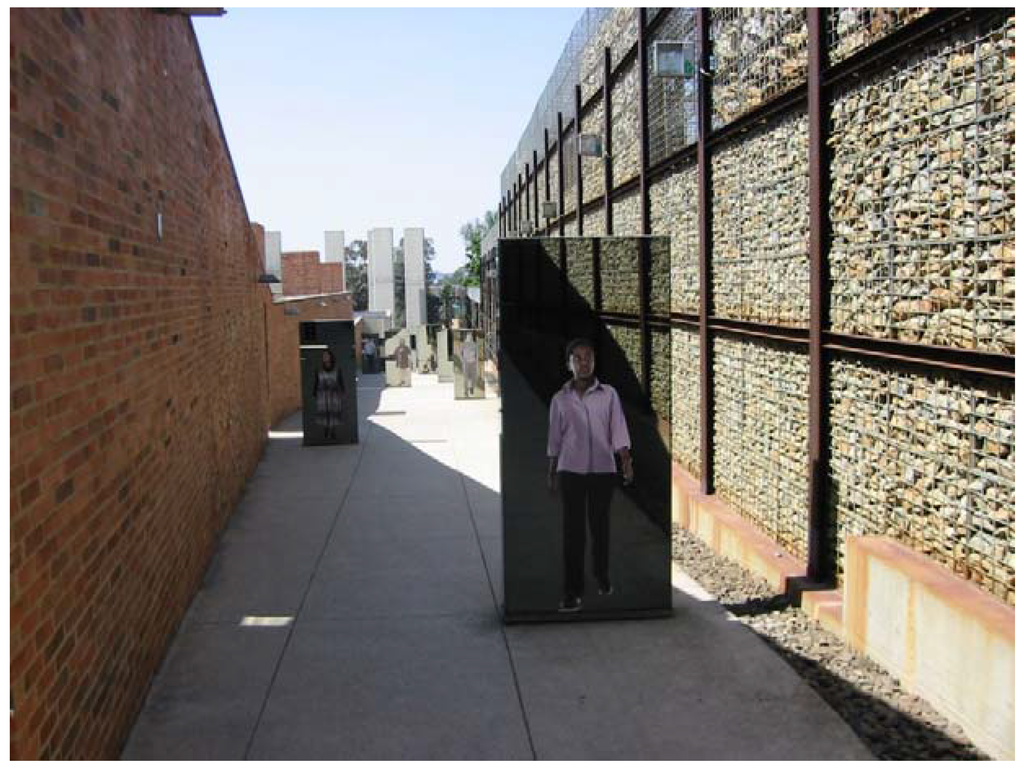

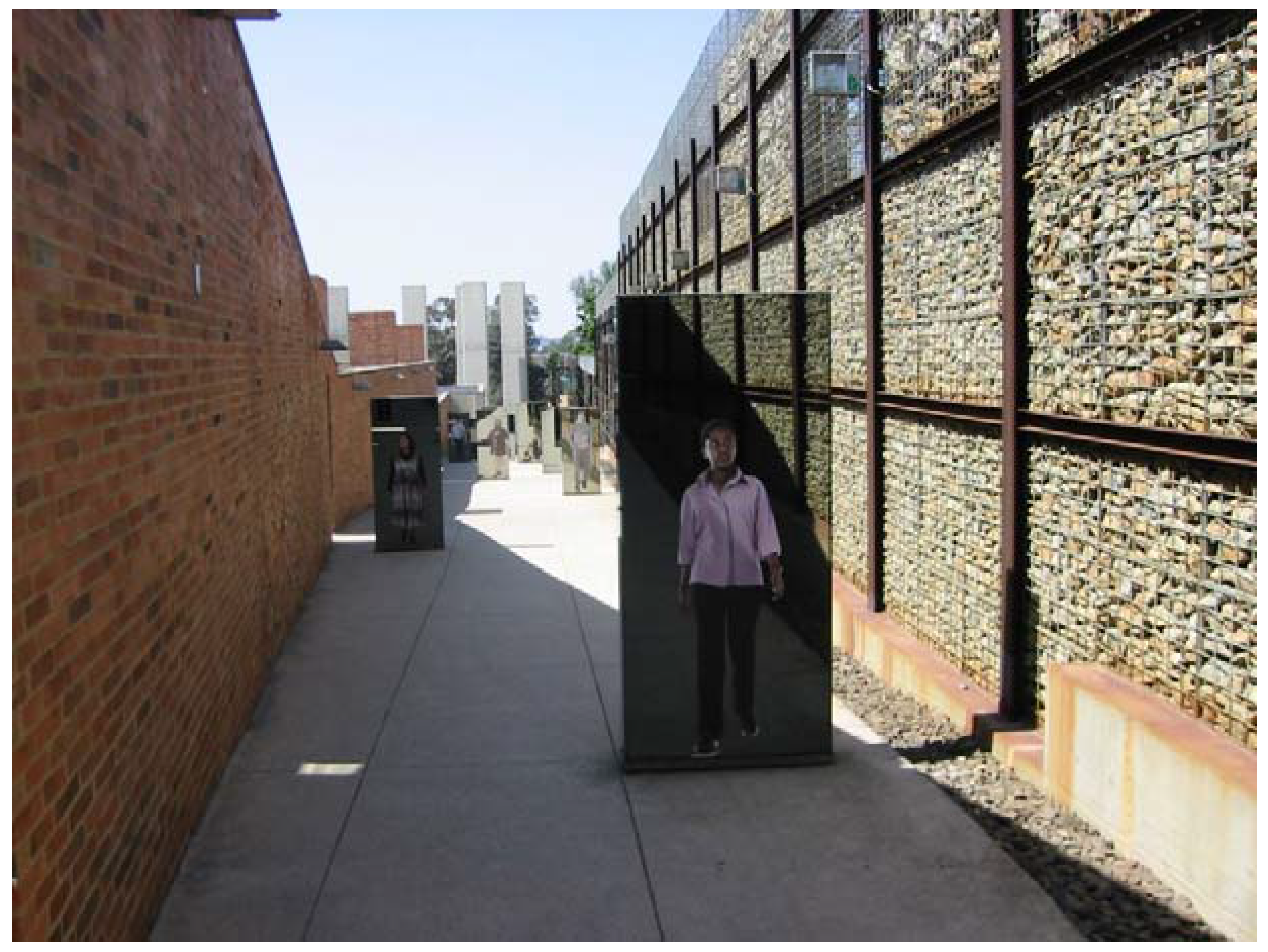

It is unexpected, but something of a relief that at the end of these forbidding spaces there is not direct access into the museum building but doors that lead outside again into the sunshine. There visitors follow a long ramp, hemmed in by high walls of brick on one side and gabion wire structures packed with stones on the other (Figure 13). At regular intervals along the ramp there are double-sided mirrors with life-sized photographs, front and back, of people associated with the Struggle; as visitors ascend they symbolically join those freedom fighters, their reflections mingling in the mirrors. Progress along the ramp itself carries metaphorical implications, continuing the sense of embodiment that visitors experienced in the entrance area, as the narrowing walls assert control, suggesting people forced to follow a pre-ordained route. At the end there is a renewed feeling of release as the confines of the ramp open onto a wide viewing platform.

Figure 13.

Ramp with mirrors and photographs leading from the entrance to the viewing platform of the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Figure 13.

Ramp with mirrors and photographs leading from the entrance to the viewing platform of the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

From here the city spreads out before visitors. Although this is not a site-specific museum in the way that Robben Island, Sharpeville and the Hector Pieterson are, the historians who devised the program for the Apartheid Museum decided to use its location to shape the story. As a major site of South Africa’s mineral wealth, Johannesburg played no small part in the development of apartheid legislation, which ensured ample migrant labor but retained the fruits of that labor for the privileged few. So when visitors descend once more into the museum proper, they first encounter large photographs of early Johannesburg, shifting the view from the terrace back in time, and opening the museum narrative by acknowledging the role that mining played in the pernicious evolution of apartheid.

The museum has a large and complex layout that creates an affective experience by directing visitors along a predetermined route that does not cater for those who prefer to wander freely, but echoes the constraints on the movement of black people under apartheid. The exhibits set up a narrative with chronological underpinnings that acknowledges the segregation of earlier colonial days, and how it was legislated into the formal policy of apartheid by the Nationalist Afrikaner government once it had been voted into power in 1948. After tracing this early history, the viewer is led along a tortuous maze-like path between wire cages which present the apartheid years (Figure 14). It is a disturbing experience as the cages’ open form prevents a clear division of one section from the next, and the lack of a collection of objects means that the displays rely chiefly on digital media: a cacophony of sights and sounds, emanating from video recordings playing on television monitors and broadcast through overhead sound domes, adds to the sense of confusion. Next to the maze is the shockingly long list of the apartheid laws that increasingly constrained personal freedom, and forced blacks and whites apart.

Figure 14.

‘Maze’ of open cages with audio-visual displays, Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Figure 14.

‘Maze’ of open cages with audio-visual displays, Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Even more disturbing is the next room which names political prisoners who were executed or died in detention, their deaths symbolized by 131 rope nooses which dangle overhead, one for each death. Beyond that is a reconstruction of the cells in which prisoners were incarcerated—bleak and distressingly claustrophobic even with their doors ajar. They are followed by a Casspir (Figure 15), an armored personnel carrier, which again plays on a phenomenological response, as the limited area in which it is displayed forces visitors into a close encounter with the huge vehicle, which looms over them, emphasizing how frightening real confrontations must have been. Casspirs became notorious for their intimidating patrols in black townships, and a video inside the confined space of the vehicle shows footage of viciously quelled riots.

Figure 15.

Casspir armored vehicle on display in the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

Figure 15.

Casspir armored vehicle on display in the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (author’s photograph).

The visit continues with further videos of violence in South Africa, screen after screen unfolding the grueling story—the experience becomes increasingly unbearable. Only at the very end of the museum is the tension relieved by a display on the first free elections, implying a successful conclusion to all the hardship and suffering. Finally, visitors are invited to add a stone to the cairn beneath the new South African flag, commemorating the sacrifice of those who died to achieve freedom, and to contemplate anew the principles of the constitution before leaving the museum.

A text at the exit of the Apartheid Museum sums up the institution’s intentions:

South Africa still bears the wounds of apartheid and of the struggle against it. If these are to heal fully, and if South Africa is to develop into a truly non-racial society, the past must be grappled with and understood. Without that, no full reconciliation can occur. This is the reason for the Apartheid Museum.

6. Communication and Communities

The final statement at the Apartheid Museum begs the question of whether everyone shares the belief that past history is important and has to be understood in order to move forward. Much has been made of the catharsis of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, and museums which uncover the country’s past may be said to perform a similar function, helping South Africans to deal with their history. But are museums equally effective in this role? The Commission revealed compelling personal histories and reached wide audiences through TV coverage: it is difficult to replicate the immediacy of the individual ‘confessional’ in a museum situation.

The function of a museum dedicated to apartheid may be considered primarily educational, intended not only to bear witness but to preclude such atrocities being repeated. The call of ‘never again’ is reminiscent of the mission statements of holocaust museums, and there are similar pitfalls to be overcome. It is essential to avoid encouraging a kind of atrocity voyeurism amongst visitors, especially tourists who have begun to seek out such sites around the world. And there is the danger of stereotyping victims and perpetrators. This is a particularly acute problem when the factors that differentiated opposing groups persist in South Africa—not only ethnic differences, but economic and class differences too. In giving the hidden past full recognition how can such programs avert imploding the hard won culture of reconciliation? And, even if divisiveness is avoided, is there not a danger that dwelling on past wrongs provides too easy an excuse for failing to meet the challenges of the new constitution?

The Apartheid Museum fulfills an important role in narrating South Africa’s years of shame as a prelude to the new constitution. It gives recognition to the lives of those who suffered, were imprisoned or died in the Struggle for liberation, and affords some ideological reinforcement for those who suffered under the apartheid regime. But it can be questioned whether it contributes to any sense of pride for the future. How effective is a museum like this is in creating cultural capital for those who were the victims of apartheid, and for those who follow? Many South Africans may feel that, having lived through the hateful years of apartheid, they do not want to relive it in a museum. There may also be some loss of confidence in whether the keenly anticipated ‘new’ South Africa has succeeded in fulfilling its aspirations, and a sense of disillusionment amongst those who feel that idealistic principles have not always been met, and that in any event principles alone, even if embodied in a museum, are a poor substitute for a living wage and adequate housing.

There is also the question of who actually visits museums. While institutions like this are a valuable resource for school groups who are brought on excursions, there seem to be few enough independent South African visitors. A high proportion of the visitors are in fact tourists, and the Apartheid Museum and the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum are well established stops on Soweto tour itineraries. So how can these institutions make themselves more relevant to the home community at large, to extend their educational function to a broader constituency? However much we may believe in the merit of museums, it has to be acknowledged that their value is not obvious to all. Their programs, devised by those fortunate enough to have a higher education, may seem inscrutable to those who do not. And even new museums may still be seen to embody old values.

Something of the gap between high-minded intentions and the realities of life for many in South Africa may be detected in an initiative of the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality, the Red Location Museum, opened in 2005 in the eponymous township, near Port Elizabeth in the Eastern Cape, the site of some of the earliest ANC activities. As is customary in South Africa, designs for the building and a new precinct for the area were open to competition and the successful design by Noero Wolff Architects has been widely applauded, winning the prestigious Lubetkin award of the Royal Institute of British Architects. In contrast to the imposing authority of its Hall of Columns, featuring heroes of the Struggle, the design takes a new approach that contests the usual hegemonies of museum narratives by creating discrete memory boxes within its vast interior. They draw on the idea of the boxes with treasured possessions that migrant workers took with them to the cities, and their fragmentary nature with separate, independent exhibits also acknowledges the fallacious nature of the single coherent history or metanarrative that museum curators customarily attempt to create.

It is an impressive piece of architecture and a fascinating attempt to give concrete form to postmodern ideas. But what of the community it purports to serve? The memory boxes are faced with rusting metal in imitation of the shanties which gave the Red Location its name. But this seems a high flown conceit that may be less than appealing to those who still live in shacks in the immediate vicinity of the museum. The new building stands in strong distinction to the surrounding township and, although it favors a more industrial style rather than mimicking the grandeur of historical European museums, its clean architectural lines are almost a mockery of the squalor around it (Figure 16). And the fact that the design included a restaurant behind plate glass at the entrance, in full view of those who might struggle to put even the most basic food on the table, exacerbated a sense of difference. Prize-winning architecture or not, one wonders whether complex ideas embodied in built form are not a misconception of the needs of the local people, more likely to alienate them than build a sense of pride. However, the museum is planned as part of a new civic center, housing also a library, archive and art gallery, and eventually sports facilities, housing, a supermarket and day care center. There is thus a strong drive to be more inclusive and uplift the lives of those who live in the area—even if, in its initial form, the fence around the museum precinct seems a metaphorical as well as a real barrier separating it from the less than perfect lives of those who live there.

Figure 16.

View of the Red Location Museum precinct with surrounding shacks, Eastern Cape (author’s photograph).

Figure 16.

View of the Red Location Museum precinct with surrounding shacks, Eastern Cape (author’s photograph).

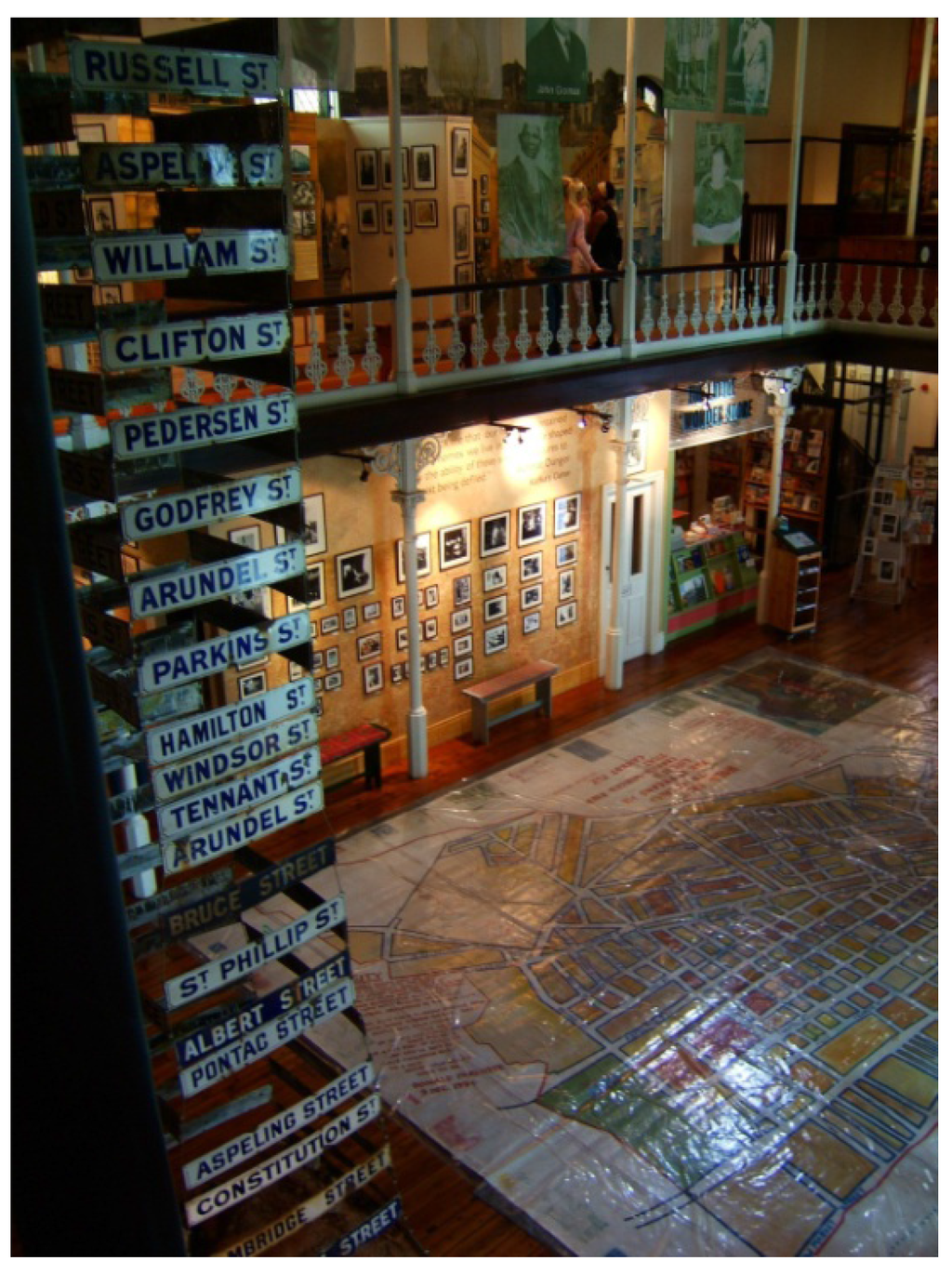

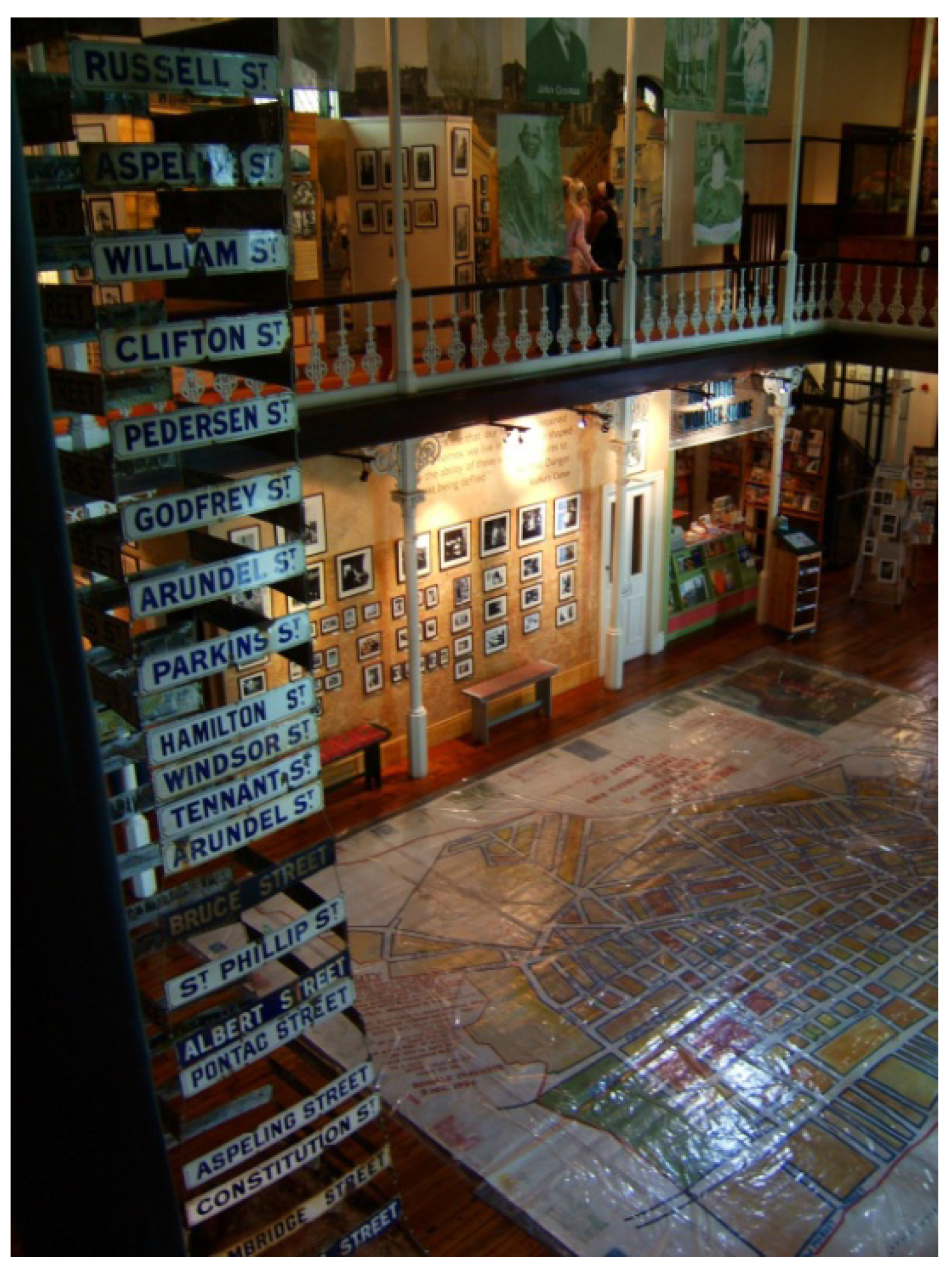

It is interesting to look back at a much earlier museum that had no such grand origins. The District Six Museum, which clearly plays a role in building self-esteem, was founded in memory of Cape Town’s most multicultural area, and its unusual approach has attracted the attention of many different writers (e.g., [6,9,12,15]). District Six was demolished after the legislation of the Group Areas Act in the 1960s, which denied people of color the right to own property or live in white cities. The museum is housed in what was originally the Methodist Church, where families with members in prison detention met to exchange information about their loved ones. The vibrant life of District Six before its destruction is recorded in the museum, pieced together from personal keepsakes and photographs, donated or loaned by past residents, in a community initiative under its inaugural director, Sandy Proselendis, whose prior experience in education and non-governmental organisations in Johannesburg go some way to explaining the fresh strategies employed, which depended on direct engagement with past residents. The establishment of the museum is discussed in Recalling Community in Cape Town: Creating and Curating the District Six Museum [15], but Proselendis’s approach is succinctly captured by her quoted words on the museum’s website (located rather oddly among Visitor’s Comments):

The District Six Museum has broken with the traditional ideas of museums and collecting. It has created and implemented the concept of an interactive public space where it is the people's response to District Six that provides the drama and the fabric of the museum.[16]

The exhibits are grouped around a huge map of the area, unceremoniously laid on the floor under a cover of plastic sheeting, created for the opening exhibition Streets: Retracing District Six, where it was surrounded by a collection of the area’s old street signs (Figure 17). The map was a simple enough idea, hand drawn and quite amateurish. While there is no clever architectural design to shape visitors’ responses, the map has become the focus of the gathering of memories, as people inscribe details on it, recording who lived and what happened at different sites, writing stories and poems, and it has been retained as a vital centerpiece of the museum. It captures a sense of community, as does the constant presence of past residents of District Six on duty at the museum, explaining its displays and narrating its stories. Whether visitors had a connection to the area or not, it is a heart-warming and energizing experience, an outstanding example of what a living museum can be and the part it can play in acknowledging a community. In some senses the District Six Museum presented a counter-culture to establishment museums; now officially recognized as a heritage site, one hopes that it does not lose its uniqueness, based on a generosity of spirit rather than a generous budget.

Figure 17.

Interior view of District Six Museum, Cape Town, showing floor map and street signs (author’s photograph).

Figure 17.

Interior view of District Six Museum, Cape Town, showing floor map and street signs (author’s photograph).

7. Freedom Park

Quite different in terms of its funding and its conceptualization is Freedom Park just outside Pretoria, a Presidential Legacy Project and the official monument for the liberation of South Africa, which began construction in 2003. In discussing the project’s origin, the Freedom Park website quotes Nelson Mandela who said in 1999, “…the day should not be far off, when we shall have a people’s shrine, a Freedom Park, where we shall honor with all the dignity they deserve, those who endured pain so we should experience the joy of freedom” [17]. Yet it is not dedicated only to heroes of the resistance, but to all those who suffered for human rights across the spectrum of South African history. President Thabo Mbeki who launched the project on the Day of Reconciliation in 2006,7 described it as “the fulcrum of our vision to heal and reconcile our nation” [18]. In this spirit, a conscious effort has been made to be inclusive, as in the naming of the different elements of the park, each of which is in a different language to reflect all the official languages of the country—for example, the sanctuary area is called Sikhumbuto (a SiSwati word meaning memorial), the hospitality suite for meetings Moshate (Sepedi for the place where the king resides), the pathway around the site is Mveledzo (Tshivenda for success), leading to Isivivane (IsiZulu for collective effort), and the rest area has an Afrikaans name, Uitspanplek. There is also a reconciliatory spirit in the description of the intended aim of the museum:

By relaying the history of our region from an African perspective, we dip into the deep wells of African indigenous knowledge as well as reservoirs of contemporary western scientific knowledge. //hapo is thus a fusion of African knowledge and western scientific knowledge that tells us what happened here, on the southern tip of the African continent.8[17]

The museum and library which are yet to be completed are named in the /Xam language, //hapo,9 meaning dream, acknowledging the earliest inhabitants of South Africa, although Khoisan languages, spoken by so few today, are not included amongst the eleven official languages of the country.

The recognition of these early peoples has been late coming, but it is telling that they provided both the main image and the motto for South Africa’s new coat-of-arms, introduced in 2000. It seems appropriate since Khoisan were the originating peoples of South Africa, but it was also a convenient way of avoiding the problem of how to select a language that would not be contentious.10 The new coat of arms is an amalgam of images that avoids motifs specific to a particular group with the exception of the central rock art figures—elephant tusks, ears of corn, protea flower, secretary bird and rising sun, all evoking positive values related to the natural environment and suggesting new life and progress, while a spear and a fighting stick are shown in a horizontal position implying their being laid down in peace. The coat-of-arms forms yet another symbol seeking to achieve reconciliation and define a united way forward.

Freedom Park is a potent attempt to create shared cultural capital in a metaphoric architecture of place, by drawing on forms which are not directly associated with a single group and which reflect values that all can relate to. The poles that surround the park, for example, are intended to evoke reeds as a sign of life, and the project constantly uses water as an important symbol of rejuvenation. Much of the emphasis is on the natural environment of the 52 hectare park. The amphitheater for large gatherings is an open-air hill slope overlooking water fountains and the Sikhumbuto sanctuary which enshrines an eternal flame (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

View of Sikhumbuto sanctuary with ‘reed’ poles in the background, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

Figure 18.

View of Sikhumbuto sanctuary with ‘reed’ poles in the background, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

One of the key features of the park is Isivivane (Figure 19), a pool surrounded by stones from historical sites in the nine provinces of the new South Africa, which symbolizes closure of past conflict and the process of healing. It was blessed by representatives of the many faiths in South Africa, who performed cleansing rituals there, and visitors are required to remove their shoes, as though walking on sacred ground. The foregrounding of natural elements is typical of the park, in the use of local stone in a form echoing ancient dry stone walling rather than ashlar masonry, and in the many views of the surrounding countryside encountered as visitors follow the winding pathway from one site to another. Alien plants are also being eliminated to create a wholly indigenous landscape.

The pathway through the site also speaks of the history of the area as views embrace two other heritage landmarks of previous eras. Freedom Park takes its place as the third element in a potent landscape, a point that triangulates the prior confrontation of the Union Buildings of imperial British heritage after the South African War at the beginning of the twentieth-century, and the Voortrekker Monument of Afrikaner ascendancy in the mid-century. Just as the Afrikaner monument represented defiance of British rule, and predicted its end when an Afrikaner government took up office in the Union Buildings in 1948, so Freedom Park signals the end of Afrikaner rule. It does so in a far less confrontational manner, however: there are even plans to link the park to the Voortrekker Monument as a single heritage site.

Figure 19.

Isivivane pool with stones from the nine provinces, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

Figure 19.

Isivivane pool with stones from the nine provinces, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

Unlike other new heritage projects, it is a site that looks forward beyond tragedy; even as it memorializes the dead, it strives to create shared values. Doing this via symbolic architectural forms and landscape elements is an astute way to avoid contentious ideologies: while the materials and organic plan reminiscent of Great Zimbabwe deployed at Freedom Park undoubtedly evoke an African aesthetic, as pointed out by Ariane Janse van Rensburg [19], it is unlikely to cause offense in the way that the imperial aspirations of British colonial architecture or the overbearing monolith of the Afrikaner Voortrekker Monument could. But it remains to be seen whether this can be achieved in the narratives told in the museum. That linguistic communications are invariably loaded seems to have been acknowledged by the use of many languages in the naming of the different elements of the park, to avoid the suggestion that one dominates over others. It is also borne out by contention relating to the categories of those named in the memorial area of the park.

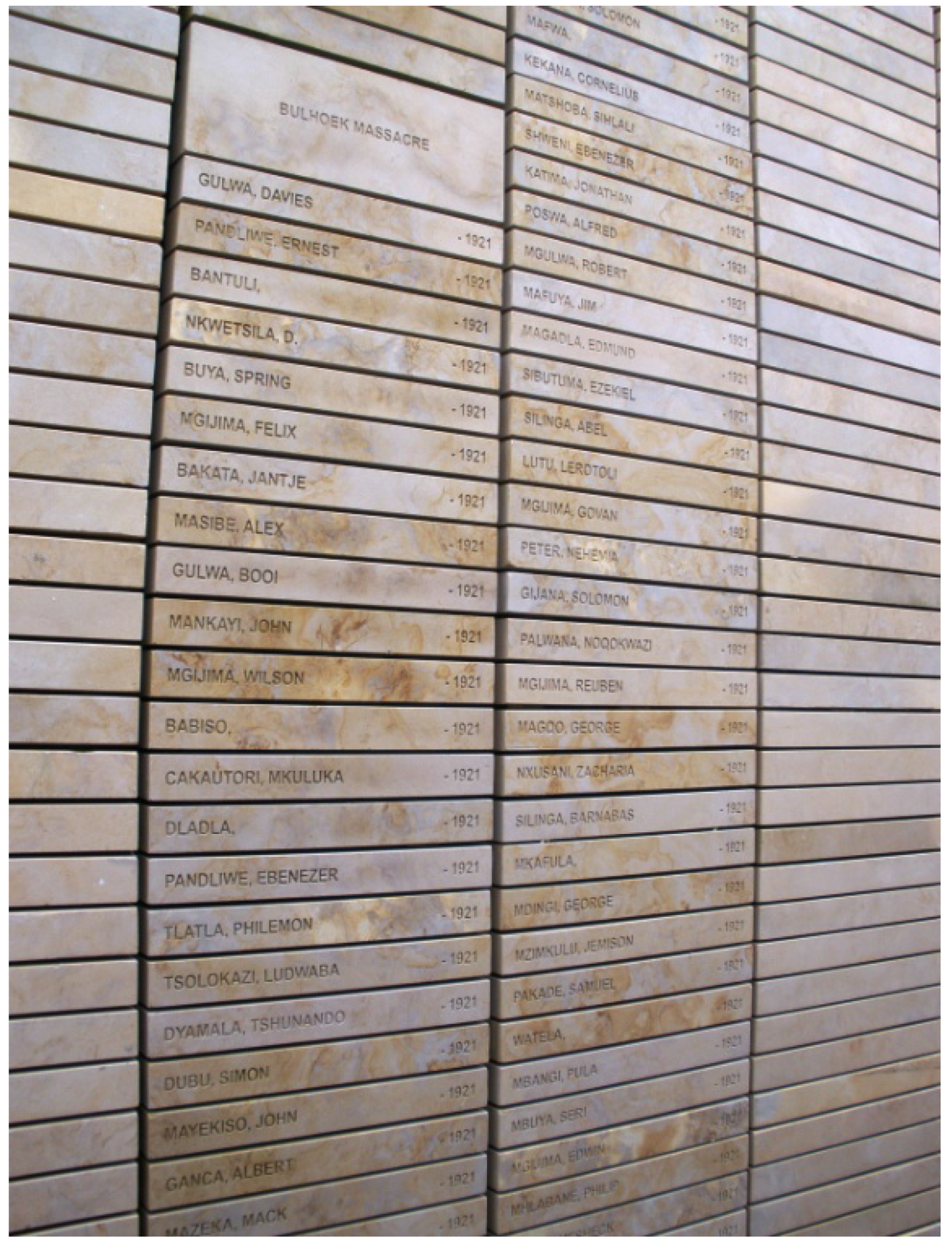

The most monumental part of the Freedom Park site is the Wall of Names, nearly 700 meters in length, which embraces the back of the amphitheater mound, and holds its own against the scale of the other heritage buildings. It is dedicated to those who died in the Struggle with places for more than 100,000 names (Figure 20), deliberately not in alphabetical order, as it is an ongoing project and more will be added as further names are submitted for verification. A database is planned where biographical information about the names will be available at an on-site touch screen. There are also memorial walls for other conflicts in which South Africans lost their lives, going back to the earliest times—the site embraces Precolonial; Genocide; Slavery; Wars of Resistance; the South African War; and World Wars I and II; as well as the Struggle for Liberation. Poignantly, the earliest of these cannot record specific names, but refer instead to events where people were killed, as in the ruthless decimation of Khoisan peoples.

Figure 20.

Detail of the Wall of Names, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

Figure 20.

Detail of the Wall of Names, Freedom Park, Pretoria (author’s photograph).

It is an indication of the strong desire for reconciliation which drives the project that the South African and World Wars are included, when African people were included in them only in subservient roles. But one category has been omitted—soldiers in the South African Defence Force (SADF) who died in the border wars and internal conflicts. Not all the young white men who were subject to compulsory conscription supported the political ideologies of the Afrikaner Nationalists who were in power; but, whatever their personal beliefs, they were fighting to uphold an apartheid government, and so have been considered unfit for inclusion on a site that pays tribute those who gave their lives in the cause of human rights. This is a bone of contention, and the Voortrekker Monument rapidly raised funds to erect a wall of honor for the SADF dead. Such problematic issues suggest that the uniting of Freedom Park and the Voortrekker Monument is not likely to be a straightforward amalgamation, and point to deeper controversies. But the park has in general steered an admirable path between the agendas of different groups, focusing on its intention to promote reconciliation and peace—even in the decision to change the lights on the poles that crown the site from red to a more pacifist blue-white.

8. Conclusions

It is telling that so many heritage projects in post-apartheid South Africa have included the development of museums, a reflection that a monument alone does not in itself seem sufficient when there is a need to tell stories anew to set the record straight. As Paul Williams writes of memorial museums internationally, “the coalescing of the two [memorial and museum] suggests that there is an increasing desire to add both a moral framework to the narration of terrible historical events and more in-depth contextual explanations to commemorative acts” ([20], p. 8). It can also be suggested that the form of a museum and exhibitions is valuable because it affords a more accessible revisionist history than scholarly texts, performing a didactic function that can range “from allowing victims to mourn, to forgiving perpetrators, to keeping criminal acts at the forefront of public consciousness, to aiding the cultural redevelopment of an afflicted people, to imparting to all of us values that might make us better human beings” ([20], p. 22).11

In addition, the built form of the museums can carry meanings. Most of the commemorative symbols within post-apartheid projects draw on precedents that are found in memorials the world over—gateways, standing stones and memorial columns, the honorific inscription of names, the purifying effect of water and the solace of eternal flames—signaling perhaps the return of South Africa to the international community after so many years of isolation. But the architecture itself develops a distinctive metaphorical language. The sense of a commonality of style could be attributed to the fact that the same influential architectural firm of Mashabane Rose has been responsible for many—the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, the Apartheid Museum and Freedom Park. But it is notable that all the projects, whoever the architects, have avoided the extravagances of colonial buildings, and instead favored red brick and shuttered concrete, which links them with more industrial buildings and evokes workers rather than overlords. Even when stone is used, the formality of cut ashlar masonry is avoided, and the stacked configurations of dry stone walling again speak of labor, and also suggest links to ancient Africa and the ruins of Great Zimbabwe. To further impart a unique flavor to museums, many post-apartheid projects have also relied on the specific locality and historical links of their sites, rather than simply the content of exhibitions, to forge a narrative.

Both sites and displays have focused strongly on the travail and torment of the apartheid era, which has a resonance shared by all South Africans, even if in vastly different ways. It is a history that has to be confronted and understood. Yet there is something inherently troubling about forging a sense of shared identity on negatives alone. A parallel could be drawn with Holocaust museums focusing on the victimhood rather than the agency of Jewish peoples. The danger is all the more potent in South Africa, when the focus on apartheid narratives has the potential to perpetuate the divisiveness of the past. But museums must avoid “simply reinforcing the silences imposed by apartheid … [encouraging] a convenient amnesia about the struggle for democracy and the sacrifices made during the liberation struggle” ([9], p. 162). And equally they should avoid perpetuating concepts of conflict, as has arguably happened at the site of Blood (Ncome) River in KwaZulu-Natal. The original Blood River site with its granite memorial commemorating the centenary of Afrikaner victory over the Zulus in 1838, which was further embellished with a laager of bronze wagons in 1971, is now paired with the Ncome Museum, which tells the Zulu side of the story. The new project embodies a cautionary tale for planners. It is touted as a site of reconciliation but, positioned as it is on the other side of the river from the earlier monument, shaped according to the fighting formation of Zulu impis, with shields emblazoned on its façade, the Ncome Museum seems to create a stand-off that re-enacts the confrontation of the adversarial battle itself. Even though both the Zulu and the Afrikaner institutions at the site acknowledge ‘divergent interpretations’ ([12], p 188), a strong impression of opposing accounts is generated, reinforcing a sense of historical opposition. Tellingly, the central element of the Bridge of Reconciliation, proposed in 1998, still lies in the veld, with the incomplete commencements of the bridge on either side of the river acting as forlorn reminders of the difficulty of fulfilling good intentions, and the overriding objective of achieving a truly reconciliatory representation of South African culture.

The most demanding task in building cultural capital at memorial museums is to reconcile an acknowledgement of past iniquities with a sense of achievement and future possibilities—to quote the phrases from the 1994 Report of the Robben Island Feasibility Study as Commissioned by Peace Visions ([9], p. 58), to achieve a balance between “a shrine to suffering and hardship” and the “triumph of the human spirit over suffering and hardship.” It is a challenge the ‘new’ South Africa has yet to meet.

References

- Isabel Wilkerson. “Apartheid Is Demolished. Must Its Monuments Be? ” New York Times. 25 September 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/09/25/world/apartheid-is-demolished-must-its-monuments-be.html?pagewanted=2&src=pm.

- Steven Sack. The Neglected Tradition: Towards a New History of South African Art (1930-1988). Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Rankin. “Recoding the canon: towards greater representivity in South African art galleries.” Social Dynamics 21 (1995): 60–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Rankin. Images of Wood: Aspects of the History of Sculpture in 20th-century South Africa. Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johannesburg Art Gallery. Art and Ambiguity: Perspectives on the Brenthurst Collection of Southern African Art. Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Rankin, and Carolyn Hamilton. “Revision; reaction; re-vision. The role of museums in (a) transforming South Africa.” Museum Anthropology 22 (1999): 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavin Jantjes, ed. Strengths and Convictions: The Life and Times of the South African Nobel Peace Prize Laureates. Oslo: Press Publishing, 2009.

- Pippa Skotnes. Miscast: Negotiating the Presence of the Bushman. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Annie Coombes. History after Apartheid: Visual culture and Public Memory in a Democratic South Africa. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie Wits, Civaj Rassool, and Gary Minkley. “Repackaging the past for South African tourism.” In Heritage, Museums and Galleries. Edited by Gerard Corsane. London and New York: Routledge, 2005, pp. 308–19. [Google Scholar]

- John MacKenzie. Museums and empire: Natural History, Human Cultures and Colonial Identities. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Steven Dubin. Transforming Museums: Mounting Queen Victoria in a Democratic South Africa. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Malefane K. Comp. Art and Culture. The Re-interpretation of the Battle of Blood River/Ncome: One-day seminar held on 31 October 1998 at the University of Zululand, Kwa-Dlangezwa. Pretoria: Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Rankin, and Leoni Schmidt. “The Apartheid Museum: Performing a Spatial Dialectics.” Journal of Visual Culture 8 (2009): 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraj Rassool, and Sandra Prosalendis. Recalling Community in Cape Town: Creating and Curating the District Six Museum. Cape Town: District Six Museum, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- “District Six Museum website.” http://www.districtsix.co.za/ (accessed on 31 January 2013).

- “Freedom Park: a heritage destination.” http://www.freedompark.co.za/cms/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=19&Itemid=21 (accessed on 3 November 2012).

- “Mbeki: Reconciliation Day Isikhumbuto Freedom Park handover.” Polityorg.za. 16 December 2006. http://www.polity.org.za/article/mbeki-reconciliation-day-isikhumbuto-freedom-park-handover-16122006-2006-12-16.

- Ariane Janse van Rensburg. “Comparing altars and agendas – using architecture to unite? ” South African Journal of Art History 24 (2009): 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Williams. Memorial Museums: The Global Rush to Commemorate Atrocities. Oxford and New York: Berg, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht Classen. “Self and Other in Contemporary German Literature: Confrontation with the Foreign World in the Novels by Renate Ahrens.” Journal of Literature and Art Studies 2 (2012): 365–76. [Google Scholar]

- Renate Ahrens. Zeit der Wahrheit. Munich and Zürich: Piper, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 1Presumably the sculpture is languishing somewhere in storage: today it is impossible to find even a picture of it, other than a lonely replica erected at the right-wing all-white Afrikaner village of Orania, which has also given a home to other deposed images of Verwoerd.

- 2Examples of these different approaches are to be found at Drakenstein Prison, Franschhoek, Western Cape; Mandela Square, Hammanskraal, Gauteng; and Mandela Square, Sandton, Gauteng, respectively. The fiftieth anniversary of Mandela’s imprisonment in 1962 provided a reason for further celebratory portraits, such as a 6.5 metre bronze in Bloemfontein, and the unusual steel structure Release by Marco Cianfanelli in Howick, KwaZulu-Natal, where Mandela was arrested.

- 3While the focus of this essay is on public museums, it should be noted that some university collections were more advanced in this regard. At the ‘black’ University of Fort Hare, for example, a fine collection of African artists was assembled by anthropologist Eddie de Jager, although it lacked dedicated exhibition premises until the De Beers Centenary gallery was built in 1989. The Art Galleries of the University of the Witwatersrand, which had led the field in introducing the study of African art in its Art History curriculum, collected historical African art from 1979 with sponsorship from the Standard Bank, and also generated many innovative exhibitions, including both historical and contemporary African art.

- 4These works, which once occupied pride of place in the gallery, were briefly mounted again at the Johannesburg Art Gallery as the exhibition From Corot to Monet: Impressionists and Post-Impressionists from the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2004, and also included in a further exhibition, The French Connection, curated by director Antoinette Murdoch (appointed in 2009) and curator Sheree Lissoos, which opened in late 2012, and currently occupies much of the gallery, temporarily reversing the now more customary dominance of African art.

- 5I acknowledge the astute comment of one of my reviewers that as a ‘fervent Zulu nationalist’ Minister Mtshali may have had considerable influence on the choice of monuments; although a fairly wide range of individuals and ideas is listed for commemoration, the point is certainly applicable to the Ncome Museum, briefly discussed at the end of the present article.

- 6I am grateful to one of my reviewers for bringing to my attention that Till was at the same time in charge of setting up the Gold of Africa Museum in Cape Town, whose celebratory approach forms a striking contrast with the Apartheid Museum, and is an indication of Till’s versatility as a museum director, previously at the Johannesburg Art Gallery and then the short-lived Johannesburg Biennale.

- 7It is a reflection of South Africa’s complex path to democracy that the public holiday on 16 December, now celebrated as the Day of Reconciliation, has embodied different meanings for different groups. First celebrated as the Day of the Vow (more popularly known as Dingane’s Day) to commemorate the Afrikaner covenant with God before they defeated Dingane and the Zulus in 1838, it also had historical meaning for ANC members as the day in 1961 when the military wing of the ANC was initiated after the massacre at Sharpeville the previous year.

- 8Museum exhibits are planned around seven epochs of South Africa’s history, which do not side-step contentious issues, but, at least in the preliminary materials displayed prior to the museum’s opening, avoid a strongly condemnatory tone which might alienate some viewers, and also suggest a role for South Africa as part of the continent as a whole—Earth; Ancestors; Peopling; Resistance and Colonisation; Industrialisation and Urbanisation; Nationalisms and the Struggle; Nation Building; and Continent Building [17].

- 9While other sources spell the word //kabbo, this is the spelling given to the name on the official website: “which has been drawn from a Khoi proverb ‘//hapo ge //hapo tama /haohasib dis tamas ka i bo’ that translates into ‘A dream is not a dream until it is shared by the entire community.’” [17]

- 10The problem had been resolved in the previous South African coat of arms when there were two official languages, Afrikaans and English, by using Latin. Interestingly that motto, translated as Unity is Strength, is not greatly different in meaning from the new one, meaning Diverse people unite, although the previous coat of arms was referring to the unification of the four independent provinces of South Africa, and of English- and Afrikaans-speaking peoples, and gave no attention to African culture.

- 11Albrecht Classen draws attention to how engaging with the experiences of ‘the other’ ‘can prove to be the catalyst for the discovery of the self, and this in psychological, mental-historical, political, religious, and social-economic terms’ ([21], p. 366), in a discussion of the novels of Renate Ahrens, particularly Zeit der Wahrheit (2005) [22], which is set in South Africa at the time of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

© 2013 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).