1. Introduction

Both the 20th and the 21st centuries have been heralded as “Kafka’s Century”

1. Franz Kafka, indeed, is one of the most popular authors of all time. His work has been translated into more than 45 different languages, and his writings have been adapted into different media and formats such as film, theater, graphics, art, radio, audiobooks, anime, comics, opera, dance, videogames, and merchandise of all kinds. The OCLC record alone lists ca. 30,000 primary works of adaptation related to Kafka’s work. The amount of commentary and secondary literature can no longer be quantified.

There are many ways to explain Kafka’s popularity. From a structuralist–institutional perspective (

Danto 1996;

Moretti 2005), his success is largely the product of a virulent “Kafka industry” that was inaugurated by Max Brod and intensified over decades by a vast network of self-interested publishers, scholars, translators, and institutions who promoted Kafka’s work methodically across the globe (

Strathausen 2024a). From an aesthetic perspective, on the other hand, Kafka’s success simply reflects the unique quality of his fantastic stories and singular literary style. “In Kafka studies, the most basic tenet on Kafka’s style is that it is not only unique, but even ‘solitary’: Scholars converge in finding that among his generation, nobody else writes like him” (

Herrmann 2017, para. 27). These two explanations are not mutually exclusive, and critics frequently endorse both (

Kundera 1991;

Harman 1996)

2. But the point is that even critics who are highly suspicious of the Kafka industry readily agree that Kafka’s literary style is somehow distinct and unique.

Yet the labels they use to identify his style remain as contradictory today as ever. Jean-Paul Sartre regarded Kafka as an Idealist (

Sartre 1999), Thomas Mann saw him as a Realist (

Mann 1949), Albert Camus as a Surrealist (

Camus 1942), and Claude Gandelman as an Expressionist (

Gandelman 1974). Such labels aside, we find a similar disagreement about which rhetorical figure best characterizes Kafka’s writing: Is his literary style essentially symbolic (

Beißner 1952), metaphorical (

Emrich 1965), allegorical (

Brod 1926;

Thompson 2016), or parabolic and paradoxical (

Politzer 1962;

Buchholz 2018)?

3 There is no agreement about the major cultural or linguistic influences on Kafka’s writing either. Contemporaries like Tucholsky and Uzedil insisted that Kafka was a quintessential “German author” who wrote “the best and most pure German” there is (qtd. in

Thieberger 1979a, 180), whereas Thieberger noted the strong presence of Austrian colloquialisms and regional idioms in Kafka’s texts (

Thieberger 1979a, 183f.), and Max Brod insisted that Kafka was a genuine Jewish author influenced by the kabbala and Jewish mysticism (

Brod 1926, 500f.;

Fromm 2010, 429f.). Since then, others have emphasized the importance of administrative and juridical parlance (

Hermsdorf 1984) and the seeping influence of the Czech language into his prose (

Woods 2013). For Deleuze and Guattari, finally, Kafka writes “a minor literature” that escapes any such labels and classifications altogether (

Deleuze and Guattari 1986).

These long-standing debates are symptomatic of the hermeneutic density of Kafka’s writing, which provides ample evidence in support of vastly different, and often contradictory, interpretations of the text. The inevitability of such contradictions, in fact, has become a recurrent theme in Kafka scholarship precisely because it mirrors and highlights the inherent ambiguity of Kafka’s texts (

Koelb 2006;

Jahraus 2008). For more than 50 years, reader-oriented and narratological studies in particular have emphasized the ambiguity and indeterminacy of textual meaning in Kafka (

Troscianko 2018;

Kobs 1970;

Walser 1968;

Wagner 2011)

4. “Ambiguity,” Ritchie Robertson states categorically, “is a major characteristic of Kafka’s texts” (

Robertson 2018, p. 65). We know that a major reason for Kafka’s many self-corrections during the writing process was precisely “to avoid simple solutions or unambiguity” in his texts (

Engel 2018, p. 58). The result is a profound hermeneutic dilemma for Kafka’s readers, who must reconcile in their minds the opposing principles of “

Deutungsprovokation und

Deutungsverweigerung” that characterize Kafka’s texts (

Engel 2010, p. 411): “Every sentence invites interpretation,” Adorno quipped, “yet none will yield to it” (

Adorno 1997, p. 267)

5. Kobs, Michael. rsten. BioAesthetics. Making Sense of Life in Science and the Arts (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 2).

In this essay, we examine how this polyvalence of meaning in Kafka’s texts is engineered both semantically (on the narrative level) and syntactically (on the linguistic level), and we ask whether a computational approach can shed new light on this long-standing debate about the major characteristics of Kafka’s literary style. A mixed-method approach means that we seek out points of connection that interlink traditional humanist (i.e., interpretative) and computational (i.e., quantitative) methods of investigation. In the second section of our article, we will provide a critical overview of the existing scholarship from both a humanist and a computational perspective. We argue that the main methodological difference between traditional humanist and AI-enhanced computational studies of Kafka’s literary style lies not in the use of statistics but in the new interpretative possibilities enabled by AI methods to explore stylistic features beyond the scope of human comprehension. For many computational stylometry studies, the goal is to design a program that can identify, verify, or profile the author of any given text with high accuracy. Whether the data behind this prediction are interpretable by humans or not is of secondary importance as long as the prediction is correct. That is not the objective in literary analysis, however, because here, the focus rests entirely on the interpretability of the data to help interpret the text.

In the third and fourth sections of our article, we will introduce our own stylometric approach to Kafka, detail our methods, and interpret our findings. Rather than focusing on training an AI model capable of accurately attributing authorship to Kafka, we wanted to know whether AI could help us detect significant stylistic differences between the writing Kafka himself published during his lifetime (Kafka Core) and his posthumous writings edited and published by Max Brod. Through this, we aim to provide fresh insights into the long-standing scholarly debate on Kafka’s literary style.

2. Kafka, Hermeneutics, and Quantification

Quantitative approaches to Kafka’s stylistic patterns date back to the middle of the last century. In his dissertation entitled

Die Sprache Kafkas. Eine semiotische Untersuchung, M. Gerhardt used part-of-speech analysis in Kafka’s texts to identify two linguistic traits that separate his early from his later writing: adjectives outnumber adverbs, and nouns outnumber verbs in texts written before 1910, but not thereafter. In texts written after 1910, both adjectives and adverbs, and nouns and verbs, share the same frequency, respectively (

Gerhardt 1969, p. 27). Since then, there have been many related attempts to use the frequency patterns of (groups of) words in Kafka’s texts to characterize his style.

Binder (

1966) notes the frequency of “Als-ob” phrases throughout Kafka’s writings (201), while Thieberger emphasizes the many “Wenn–Dann” constructions as well as frequent repetitions of words and phrases, the use of series (Reihung) by piling up attributes, and the frequent use of parenthesis (

Thieberger 1979a, 188f.).

The Kafka Konkordanz (1993/2003) continued this tradition on a much larger scale. The two volumes of the Konkordanz provide detailed statistical information about total word count, word frequency, and frequency of major parts of speech (e.g., nouns, adjectives, conjunctions, etc.) within and across Kafka’s three novels and his Nachgelassene Schriften (according to the Kritische Kafka Ausgabe [KKA]). To refine their data, the editors reduced each word (token) in Kafka’s text to its base form or type (e.g., sehe to sehen or Herrn to Herr) and then calculated the type/token ratio for each individual corpus. This token/type relation provides critical information about the lexical variety of a text. For example, the Konkordanz documents that the most common tokens across all three Kafka novels are verbs (ca. 21% of all words in the novels), followed by nouns (ca. 17%), adverbs (ca. 8.5%), and adjectives (ca. 7%). Once tokens are reduced to types, however, the most common ones are nouns (ca. 44% of all distinct word stems in the novels are nouns), followed by verbs (ca. 33.5%), adjectives (ca. 15%), and adverbs (ca. 5%). This type/token ratio tells us that although Kafka uses more verbs than nouns throughout his novels, the lexical variety of the nouns he uses is significantly higher than that of the verbs. In other words, Kafka uses the same verbs far more frequently than he uses the same nouns. With regard to specific word frequencies, the Konkordanz shows that the most common verbs (sein, haben, sagen, werden, können, wollen) and the most common adjectives (viel, groß, gut, gleich, wenig, klein) are fairly stable across all four corpora, whereas the most common nouns are more varied, meaning they differ from one another more than do adjectives and verbs.

A major limitation of the statistical data in the

Konkordanz is the lack of an external comparison—that is, another author or set of authors—to render the data interpretable and meaningful for the debate about Kafka’s literary style. To be sure, the

Konkordanz does provide comparative statistical data of different works

within Kafka’s oeuvre, a line of inquiry that is continued in recent computational studies (

Salgaro 2023). But the

Konkordanz does not combine its four corpora into a single “Kafka corpus” with its own metadata and then compare them to the metadata of other German modernist writers around 1900

6. Recent computational analyses of Kafka’s style have done precisely that. Berenike Herrmann, for example, compared the stylistic features of Kafka’s texts to that of 20 other German authors around 1900

7. Her parts-of-speech analysis showed “a high frequency of lemmas that may perform ‘modal’ functions in the discourse” (

Herrmann 2017, para. 42). This makes sense, since the function of modal words (e.g.,

ja,

doch,

nur,

bestimmt, etc.) in discourse is to convey the speaker’s mood or attitude vis-à-vis the propositional content of the speech, the ambivalence of which is a major characteristic of Kafka’s narrative voice. Two other computational studies by Matt Erlin confirm the relative frequency of modal words in Kafka’s text (

Erlin 2017;

Erlin et al. 2023). We return to this point in the next section when we discuss our own computational analyses of Kafka’s text.

For now, we want to emphasize that Herrmann’s analysis also showed that “Kafka’s texts indeed form a cluster, which means that they are more similar to each other than to any other text in the study,” and that Kafka appears somewhat “removed from the rest of the corpus” (

Herrmann 2017, para. 34). These results strengthen the singularity thesis about Kafka’s unique literary style. But they come at a price. Whereas the

Konkordanz still enumerated the exact word frequencies and type/token ratios it found across Kafka’s novels, Herrmann’s study employs computational tools that combine hundreds of such features into a multi-dimensional vector space that ultimately gets visualized as a graph or map in two-dimensional space to aid human interpretation of the data. This approach enables a more comprehensive comparison of literary styles between different authors.

Hence the sheer computational prowess of today’s natural language processing tools, made possible by the recent advancements in AI technology, ushers in a new and distinctive era of statistical research on Kafka’s style. In methodological terms, there is no difference whether we count Kafka’s words by hand, as scholars did in the 1960s, or by machine, as we do today. But there is a huge difference between statistical results based on simple (and easily interpretable) parameters like word frequency in comparison to complex statistical results based on hundreds of stylistic parameters spread across multi-dimensional vector spaces that machines can read but humans cannot. Herrmann is cognizant of the problem and shifts her analysis back to a qualitative close reading of how modal particles function in some of Kafka’s texts. This is a mixed-method approach that combines hermeneutic criticism with statistical analyses, and our own approach follows the same model.

The key point we wanted to make in this section is that this mixed-method approach has a long history in Kafka studies and that the main distinction between humanist and computational analyses of literary style is not the use of statistics or scientific methods per se because everybody uses them to some degree in different ways. The main difference concerns the use of AI models that transform literary texts into features through sophisticated processes, capturing stylistic characteristics that reflect quantitative patterns of traits that we, human readers, cannot identify or interpret anymore.

There is a related distinction we want to introduce before we move on to our own computational studies of Kafka’s literary style. On the one hand, Kafka’s vocabulary can be described in positive scientific terms. This includes statistics about word frequency, parts-of-speech distribution, punctuation frequency, type/token analysis, etc. It also includes data about the relative frequency of modal particles and subjunctive I in Kafka’s texts as compared to those by other authors or data about the increasing dominance of direct speech in Kafka’s later works that culminate in The Castle (ca. 70% of the novel in the KKA consists of direct speech). Data of this kind is both quantifiable and indisputable (as opposed to the interpretation of this data, which certainly is disputable). It is scientifically robust but hermeneutically weak. To claim that the frequent use of modal words in Kafka’s texts contributes to (or correlates with, to use a more modest claim) the semantic ambiguity of Kafka’s texts is like claiming that alliteration, rhyme, and meter serve to increase the musical quality of pre-modernist poetry. It is a good insight but not an interpretation. This explains why computational studies like Erlin’s and Herrmann’s merely use these kinds of data as a starting point for more targeted investigations about the complexity of Kafka’s style.

We distinguish this group of

linguistic traits from a second group of

stylistic traits that are less static and more dynamic, which makes them harder to quantify. For example, critics frequently emphasize the self-reflexivity of Kafka’s texts, their dynamic tension between form and content, and the predominance of free–indirect discourse as characteristic of Kafka’s style

8. We cannot discuss these traits in detail, so we comment only on the dynamic tension between the linguistic form and the propositional content of Kafka’s writing. When critics describe the structural principle of Kafka’s prose as a “paradox circle” (

Kobs 1970, p. 14) or a “sliding paradox” (

Neumann 1968), they highlight a peculiar tension in his writing, namely that it constructs meaning at the linguistic level while, at the same time, it undermines that meaning at the rhetorical or narrative level. Kafka’s texts, in other words, juxtapose the obtuse meaning of

what is being said with the linguistic clarity of

how it is said.

9 What remains is “a narrative that doubles itself and allows what is told to be subverted by the very act of telling” (

Neumann 2011, p. 89; our translation). It is important to note that this dynamic tension primarily unfolds at the level of narration, not the plot level. It is not the argumentative back and forth between quarreling characters that undermines the credibility of linguistic signification in Kafka’s novels. Rather, narrative language succumbs to the fecundity and incongruence of meaning produced at the linguistic, rhetorical, and propositional levels of the text that cannot be synthesized into a coherent whole.

The distinction between these two groups—between positive linguistic traits and dynamic stylistic traits—carries significant implications for a computational approach to Kafka’s style. The dynamic nature of stylistic traits makes it difficult to quantify them into discrete, analytical values, which are necessary for computational approaches to operate. Counting metaphors (or paradoxes or self-reflexivity) is not as easy as counting nouns. Metaphors are more versatile, and they cannot easily be reduced to a stable linguistic core the way nouns can. A stem word like “Hand” appears hundreds of times in Kafka’s novels, but assumes only three codified forms (Hand, Hände, Händen). An expression like “die Hand heben/geben/reichen/fassen/streicheln” also appears hundreds of times yet exhibits a wide variety of different forms that may, or may not, function as metaphors depending on context.

All stylistic traits in the second group (e.g., narrative voice, self-reflexivity, form–content dynamics, etc.) are difficult to classify linguistically because they are structurally complex and activate different levels of meaning within the text. Yet their complexity makes these traits highly productive in hermeneutic terms, meaning they increase the semantic ambiguity that characterizes Kafka’s texts overall. We agree with

Drucker (

2012) and others that the future role of digital humanities in literary studies might depend in part on its ability to address this complexity problem and to offer adequate computational tools that can reasonably model the dynamic interplay of meaning production in literary text in ways that enable humanist interpretation of the data.

In our own computational studies described below, we have sought to identify and examine traits of both kinds; that is, we studied some dynamic stylistic traits and some positive linguistic traits that characterize Kafka’s texts. Through this dual approach, our article seeks to leverage the computational power of these novel AI models to gain an understanding of Kafka’s style from an unprecedented perspective while minimizing the limitations of the AI “black box” by closely examining the results through the lens of hermeneutic criticism.

3. Stylistic Comparison of Kafka vs. Brod

In our study, we created and used three corpora of texts: (a) all literary writings that Kafka himself published during his lifetime (Kafka Core); (b) Max Brod’s second edition of Kafka’s Gesammelte Schriften (1946–47) (

Kafka 1946); and (c) a selection of novels and fiction written by Brod between 1909 and 1935. What distinguishes our study from previous quantitative studies is that we split Kafka’s oeuvre into two groups (a and b), which allows us to compare texts edited and published by Kafka himself with texts edited and published posthumously by Brod.

We consider this distinction relevant and meaningful. Let us recall that many changes Brod made in his edition of Kafka’s Gesammelte Schriften had less to do with re-writing Kafka’s handwritten manuscripts than with re-arranging them. The Franz Kafka Ausgabe (FKA), a facsimile edition of Kafka’s manuscripts (1992–2018), revealed that Brod created coherent narratives from literary fragments and that many of Brod’s choices reflect his own personal preferences rather than common editorial practice

10. Hence, Roland Reuß, the editor of the

FKA, claimed that the novels commonly known as

Amerika,

The Trial, and

The Castle were authored by Max Brod, not Franz Kafka. “Kafka did not leave behind any novels” (

Reuß 1995, p. 21). Reuß’ wording is precise. Kafka wrote the material, sure, but he did not author any novels. The authorship belongs to Brod and his edition of Kafka’s texts.

To test this claim, we first investigated stylistic traits across the three corpora by tasking AI with developing its own set of stylistic criteria to distinguish them. We trained two distinct AI models to classify Kafka Core and Brod’s own literary corpus. Next, we tasked each model with assigning authorship of specific sections of text from Kafka’s

Gesammelte Schriften to either Kafka or Brod based on the stylistic patterns identified earlier. Our aim was to determine whether AI models would classify sections of Brod’s edition as stylistically closer to Brod’s own writing than to Kafka’s. Hence, our experiment differs from the typical case in stylometry research. The standard goal of using machine learning in stylometry is authorship attribution, which can be outlined as “Given a set of texts with known authorship, can we determine the author of a new unseen document?” (

Savoy 2020, p. 9). That is not our question. We already know exactly how Kafka’s original manuscripts were altered by Brod in his

Gesammelte Schriften. Both the

KKA and the

FKA provide detailed evidence of these changes, so there is no mystery here to solve. Instead, our focus is on examining the stylistic characteristics of Brod’s edition by analyzing its stylistic alignment with Kafka Core and Brod’s own works through AI-based analysis.

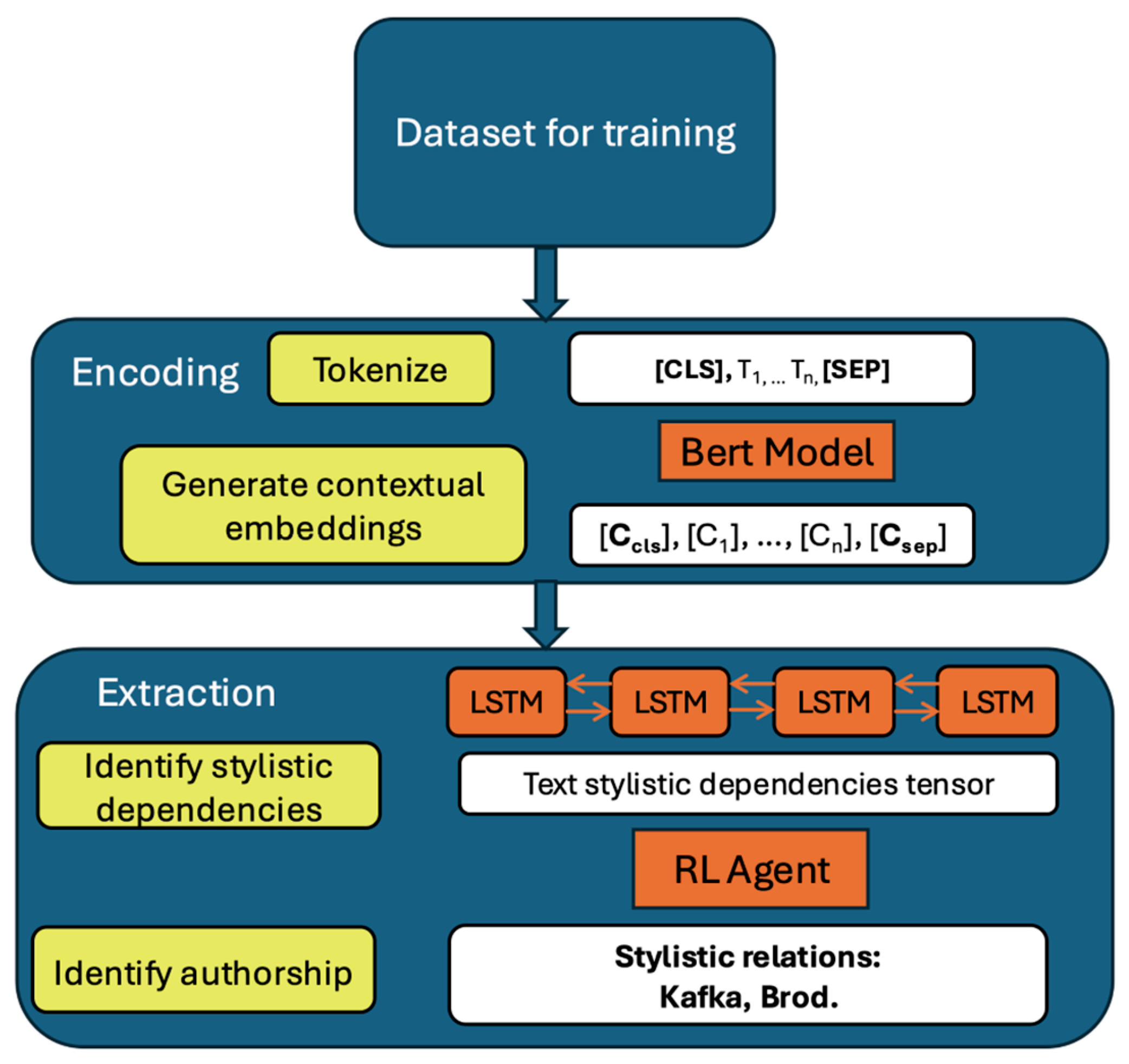

We used deep learning models in our classification experiments because they mitigate the limitations of hand-crafted features (e.g., word frequency, syntactic features, sentence length), which are often ineffective at capturing subtle stylistic traits. Deep learning models, particularly attention-based architectures like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), excel at capturing contextual information, making them well-suited for identifying stylistic nuances based on word usage, syntax, and grammar. This capability is crucial for detecting subtle variations in style, such as those introduced when a text is edited by another author. Deep learning models also handle fragmented text effectively, analyzing individual passages while maintaining a broader understanding of the entire document. Additionally, in real-world scenarios, authors’ styles are rarely perfectly distinct, as texts often exhibit a mixture of styles and inherent noise. Deep learning models, when trained on sufficient data, are more robust against such noise and can detect subtle stylistic shifts.

After preprocessing our three corpora (Kafka Core, Brod’s corpus, and Brod’s edition of Kafka), we divided each corpus into chunked passages of approximately 400 words using a BERT tokenizer and generated embeddings (numerical representations of text capturing semantic meaning) for each chunked passage with a pretrained German BERT model, available at

https://huggingface.co/dbmdz/bert-base-german-cased (accessed on 27 February 2024). To improve the robustness of our experiments, we employed two deep learning architectures that achieved state-of-the-art (SOTA) results: BERT fine-tuning and Bi-LSTM (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) Q-Learning. Both architectures were trained on the embeddings of the chunked passages of Kafka Core and Brod’s corpus to learn their stylistic differences. The models then made independent predictions on each chunked passage of Brod’s edition of Kafka, assigning either Kafka or Brod as the author. Since all the texts were originally written by Kafka (though edited by Brod), the correct attribution in each case was Kafka.

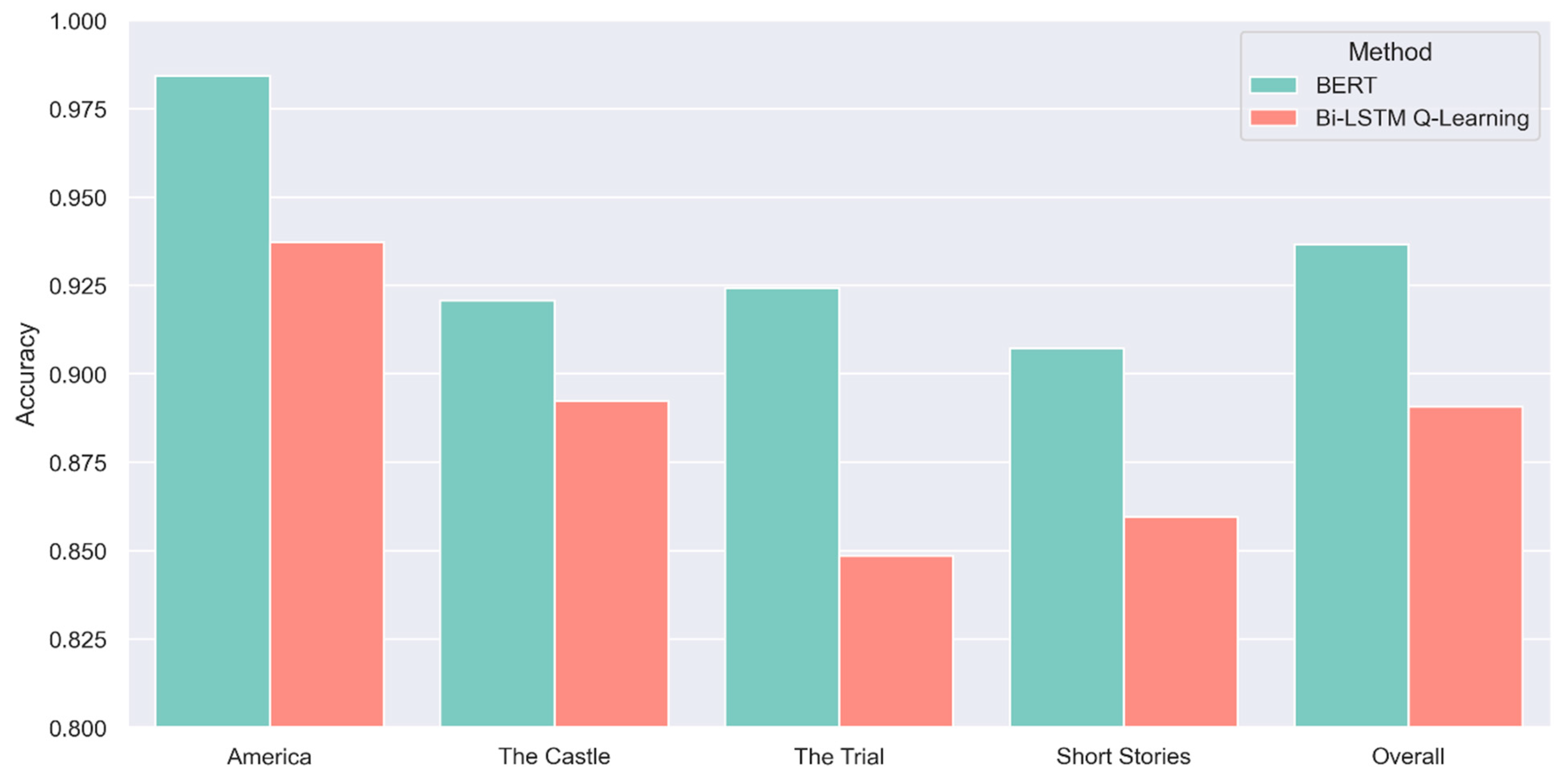

Figure 1 shows the accuracy results for both models.

For the technical details of the classification experiment, please refer to

Appendix A.

Among the 1545 chunked passages, 169 of these passages were misidentified by Bi-LSTM Q-Learning and 98 by the BERT classifier as Brod’s work. From a computational perspective, it is noteworthy that BERT consistently outperforms Bi-LSTM Q-Learning, which is understandable given that BERT employs a more advanced architecture compared to LSTM. In hermeneutic terms, it is remarkable how well, overall, both methods performed. The overall accuracy for Bi-LSTM Q-Learning was 89%, and that for BERT was 94%. We do not know and cannot interpret the thousands of criteria AI uses to calculate the statistical probability that a specific segment of text was written by Kafka, not Brod. We only know the result, namely that BERT correctly identified 94% of (thousands of) word segments in Brod’s edition of Kafka as written by Kafka, not Brod.

We were particularly interested in the remaining 6% of cases. Our hypothesis was that AI would primarily misidentify those text segments in Brod’s edition of Kafka where Brod’s editorial interventions are more evident than elsewhere. We used the

KKA and the

FKA editions to identify those passages that AI falsely associated with Brod, and we checked if and how these passages in Kafka’s manuscripts had been altered by Brod in his edition of Kafka’s

Gesammelte Schriften. But we could not confirm our hypothesis. Both AI programs frequently flagged text segments in Brod’s edition of Kafka that showed little or no apparent editorial interventions by Brod. We also identified a paragraph in Brod’s second edition of Kafka’s

Gesammelte Schriften that literary scholars have cited as evidence for Brod’s editorial meddling in the original manuscripts. In the opening paragraph of

The Castle, Brod changed the tempus of one verb from present tense to past tense, which has significant implications for the narrative voice and readers’ understanding of the text (

Strathausen 2024b). We checked whether our AI models had flagged this passage or not. Since only the BERT model provides a certainty level when assigning a passage to an author, we focused on its result, which showed that the BERT model identified Kafka’s authorship of this passage with 99.998% certainty. This result reminds us that a simple temporal change from presence to past tense in a literary text is

not significant in stylometric terms yet can be

very significant in hermeneutic terms with profound narratological implications for how to read and understand the text.

Finally, we wondered why both BERT and Bi-LSTM Q-Learning were more successful in identifying text segments from Kafka’s

Amerika compared to his other two novels and the remaining prose. Again, a cursory comparison of Brod’s edition of Kafka with the

KKA does not reveal any apparent differences in Brod’s treatment of

Amerika as opposed to other texts. As he had done previously for

Der Prozess [

The Trial] (

Kafka 1925) and

Das Schloss [

The Castle] (

Kafka 1926), Brod’s 1927 edition of

Der Verschollene [

Amerika] (

Kafka 1927) too, arbitrarily classified long sections of Kafka’s handwritten text as fragments and relegated them to the appendix. If Brod’s interference, or lack thereof, does not explain why AI identified Kafka’s style more easily in

Amerika than in his other texts, we must conclude that Kafka’s style in

Amerika is somehow more pronounced—which is to say, more accurately quantifiable—than elsewhere. A possible reason might be that Kafka wrote most of Amerika in a relatively short period (from September 1912 until January 1913), right after he had written “The Judgment,” a key text that signaled his literary breakthrough and that Kafka himself considered one of his best, and most authentic, works

11. Kafka was equally proud of the first chapter of

Amerika, which he published separately with Kurt Wolff under the title “Der Heizer. Ein Fragment” in Spring 1913. It is rare for Kafka to embrace his works so unconditionally. Does Kafka’s satisfaction with these texts point to a particular literary style that emerged during the short period from September 1912 to January 1913 and that AI is able to identify but Kafka was not able to replicate in his later writings? Such speculations are intriguing, but trying to substantiate them would require a lot more computational research with more granular corpora (e.g., single chapters) from all three novels and other writings by Kafka.

4. Linguistic Comparison of Kafka vs. Brod

To complement the AI-based approach for the identification of stylistic traits, we also analyzed three specific linguistic traits in each corpus, namely sentence length, the frequency of punctuation signs, and the frequency of subjunctive I. For the first two traits, our hypothesis was this: to the degree that Brod’s edition culled together disparate, decontextualized fragments into coherent literary texts, the formal appearance and inner structure of these texts were significantly shaped by Brod, not just Kafka. We wanted to see if sentence and punctuation statistics bore this out. As for subjunctive I—a mode of speech that introduces ambiguity about whether the reported statements are true and thus contributes directly to several stylistic traits of Kafka’s prose (e.g., narrative voice, form–content dynamics, contradiction, etc.)—our hypothesis was that Kafka Core would have a higher relative frequency of subjunctive I than both Brod’s own literary corpus and Brod’s edition of Kafka’s works.

We used the natural language processing tool SpaCy (

https://spacy.io, accessed on 27 February 2024) and the pretrained “de_core_news_lg” model to calculate total words, sentences, punctuation, and subjunctive I occurrences. This process involved dependency parsing, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging. The main challenge was accurately identifying subjunctive I forms in German; our identification approach is detailed in

Appendix B.

Table 1 shows that Kafka Core has a larger value in words per sentence and a smaller value in punctuation per word compared to Brod’s corpus. The values of Brod’s edition of Kafka stay in between but are much closer to Kafka Core than to Brod’s corpus. Brod’s literary works, in other words, feature shorter sentences with more punctuation signs than Kafka’s across both corpora (Kafka Core and Brod’s edition of Kafka). One interpretation of these statistics is that Brod’s emendations of Kafka’s unpublished manuscripts resulted in shorter sentences and increased use of punctuation signs compared to Kafka Core. Brod’s edition, so to speak, “pulled” Kafka’s texts towards Brod’s own style of writing (shorter sentences, more punctuation). That part of the data is consistent with our hypothesis.

The results for subjunctive I, however, were quite unexpected. Kafka Core has the smallest value (least frequency of subjunctive I), quite close to Brod’s corpus, while Brod’s edition of Kafka has a much higher value. It is difficult to interpret this result. We know that Brod occasionally changed tense and mood in Kafka’s sentences, but these relatively few instances cannot account for the significant value difference in subjunctive I between Kafka Core and Brod’s edition of Kafka. Moreover, both corpora include texts that were composed during different writing periods in Kafka’s life, that is, the early period (1904–1912), middle period (1913–1919), and late period (1920–1924), so we cannot attribute the difference in subjunctive I frequency to the different writing periods in Kafka’s life either. One possible explanation might be genre. The literary texts in Kafka Core are all (relatively short) stories, whereas the literary texts in both Brod’s own corpus and Brod’s edition of Kafka are dominated by (relatively long) novels.

Therefore, the value difference between the two Kafka corpora might reflect a genre-specific preference of his for the use of subjunctive I in novels as opposed to shorter prose pieces. The use of subjunctive I in German is directly tied to indirect speech, that is, to speech that reports what others have said in a neutral manner without assessing the veracity of the reported statement. Kafka’s longest novel, The Castle, consists mostly of characters’ direct speech, but this speech often contains long reports about alleged statements made by other characters expressed in subjunctive I. Hence, the frequency of direct speech in Kafka’s texts might be tied to—or correlate with—the frequency of indirect speech in the same text. Our metrics support this hypothesis. We found that The Castle, which has the most direct speech by far among all of Kafka’s works, has a much higher average use of subjunctive I per word (0.0058) compared to Amerika (0.0033) and The Trial (0.0048), and all three novels have a much higher average of subjunctive I per word than Kafka’s shorter stories (0.0024). One explanation is that Kafka’s longer texts, i.e., the novels, include more direct speech and dialogue, and these dialogues include portions of indirect speech that require the use of subjunctive I in German. Though true for Kafka, this finding can hardly be generalized. The fact that Kafka’s novels have a higher percentage of direct speech than his other prose (which correlates with a higher percentage of indirect speech and higher frequency of subjunctive I) does not mean that novels by other authors do, too. Trying to determine whether or not genre can be linked directly to different frequency rates of direct speech or subjunctive I in literary texts would require historical and genre-specific parameters of what we mean by “novel” or “literary form” in the first place, and it would require extensive computational research and large amounts of data from numerous corpora.

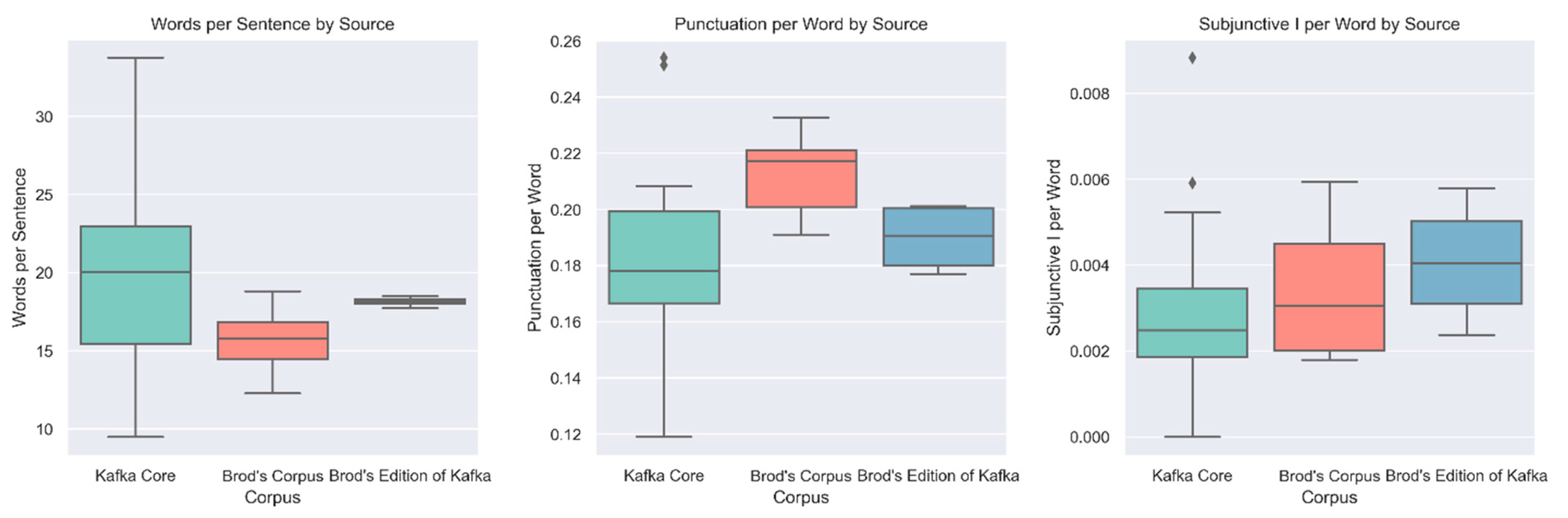

With this caveat in mind, we also found the more detailed statistics, as visualized in the boxplots of

Figure 2 below, helpful to characterize the literary style in Kafka Core.

The boxplots visualize the values of each individual work in the three corpora. If we just focus on the green boxplot (representing Kafka Core) in the left chart (words per sentence), it tells us that a literary text published during Kafka’s own lifetime ranges from 9 to 34 words per sentence at the extremes and from 15 to 23 words per sentence in the green box representing “interquartile range,” which includes the middle 50% of data—spanning from the 25% smallest data points to the 75% smallest. The middle chart shows a similarly wide variation in the punctuation per word in Kafka Core, which ranges from 0.12 to 0.25 at the extremes and between 0.17 and 0.20 in the green box. In other words, Kafka’s texts published during his lifetime vary significantly with regard to sentence length and punctuation use.

As we said earlier, this variation cannot be correlated with different writing periods in Kafka’s life because it occurs across periods and within each period. There is even significant variation of these metrics among stories published in the same collection (like Betrachtung from 1912 (

Kafka 1912) or

Ein Landarzt from 1919)

13. The most intuitive explanation for this variation is, once again, literary genres. Kafka experimented with different forms of literary writing throughout his life, and stylistic variations in sentence length and punctuation are surely part of this experimentation. The fact that we find far less variation in Brod’s edition of Kafka might be due to the predominance of long novels in that corpus and in Brod’s corpus. To test this further, we would have to compare these metrics in Kafka Core to those of other German literary writers around 1900 (not just Brod). As of now, none of our results contradict, and some of our results support our initial hypothesis that Brod’s emendations of Kafka’s unpublished manuscripts created a literary style closer to his own than Kafka’s.