1. Into the MonsterVerse

More than a hundred meters in height, with dorsal plates emitting a nuclear glow and a roar audible across large distances, Godzilla seems somewhat hard to “miss”. And yet, the most recent American (re)imagination in the multi-media franchise

MonsterVerse1 focuses heavily on making the giant monster visible, audible, sensible through technological mediation. In this article, I am proposing to read the giant monster’s (dis)appearance in the

MonsterVerse as a reflection of larger socio-cultural concerns about visibility and truth. At the beginning of 2024, the “Doomsday Clock”—a symbolic indicator of perceived proximity to apocalyptic events—was set to remain at 90 s to midnight, the closest it has ever been to “global catastrophe” (

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 2024). The threats to humanity and the planet listed in the scientists’ reasoning balance a fine line between visible and invisible, real and hypothetical—and echo through the history of science fiction films and its monsters, from radioactive contamination and artificial intelligence to environmental devastation. Drawing on Susan Sontag’s understanding of the “deepest anxieties about contemporary existence” (

Sontag 1965, p. 47) lurking beneath the surface of science fiction films, this article argues that the focus on monitoring, mapping and materializing the giant monster in the

MonsterVerse functions as a negotiation of the limits of visibility of catastrophe. Co-produced by Legendary Entertainment and Warner Bros. Pictures, the multi-media franchise

MonsterVerse centers on a narrative universe shared by Godzilla, King Kong and other monsters referred to as “Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms” (MUTOs) or, once they have been identified and named, “Titans”. At the time of writing, the

MonsterVerse consists of the five feature films

Godzilla (

Edwards 2014),

Kong: Skull Island (

Vogts-Roberts 2017),

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (

Dougherty 2019),

Godzilla vs.

Kong (

Wingard 2021) and

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (

Wingard 2024), the animated series

Skull Island (

Duffield 2023) and the television series

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (

Black and Fraction 2023), as well as a series of comics. Both leaning on and expanding from the monstrous characters introduced in the films of Japanese film studio Toho, the

MonsterVerse presents a world that is aware of the existence of Godzilla—following a showdown between Godzilla and two MUTOs in San Francisco—and yet still seems to grapple with the implications of a monstrous hierarchy.

While engaging with the

MonsterVerse as a larger universe, the main focus of my discussion will be the television series

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023). Not only because the format of the series allows for more narrative development but also because the series can be understood as a connective element between the films—filling in some of the (narrative and scientific) blanks glanced over in the spectacle of Hollywood productions. The series, which premiered on the streaming service Apple TV+ in November 2023 and has since been renewed for a second season as well as multiple spin-off series (

Rice 2024, n.p.), weaves together two narrative timelines: The series’ present timeline begins in 2015, after the events of

Godzilla (2014), and follows half-siblings Cate and Kentaro Randa on a search for their missing father Hiroshi “Hiro” Randa with the help of hacker May Olowe-Hewitt. Not only did their father keep his second family a secret but also his professional and personal connections to the scientific/military “monster-hunting” organization Monarch. The series’ past timeline, moving non-linearly from the 1950s to the 1980s, explores the origins of Monarch through the experiences of Japanese scientist Keiko Miura, her American military escort Lee Shaw and cryptozoologist Bill Randa. As the series progresses, these two timelines become more and more entangled as the “present” trio teams up with Lee Shaw to follow Hiroshi Randa and the giant monsters he, in turn, seems to be conjuring from the depths of the earth. In doing so, the series appears to trace both the genealogy of the Randa family, from Keiko Miura to her son Hiroshi Randa and his children Cate and Kentaro Rando, and the genealogy of the giant monsters waiting in, on and beneath the earth.

Time and space play an important—if somewhat confusing—role in the

MonsterVerse more generally: The first movie,

Godzilla (2014), mostly takes place in contemporary San Francisco of the year of its release but opens with two parallel events unfolding in the Philippines and Janjira, Japan, in 1999. The second installment,

Kong: Skull Island (2017), moves back in time, with an opening scene set in the Second World War in 1944, followed by an expedition to the titular Skull Island in 1973 during the last days of the Vietnam War. This pattern of establishing a temporal development also comes through in

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019), which begins in the direct aftermath of the destruction wrecked by Godzilla in San Francisco in 2014, to then move forward five years to the film’s present. More than narrative prologues, I am proposing that the continuous back and forth in time and space in the

MonsterVerse functions as a commentary on the persuasive power of media. Throughout and across these installments, mediations—ranging from folklore and oral history via classified documents to photographs and smartphone recordings—function as connecting elements, tying the past to the present and the scientific to the mythical, while at the same time complicating what is and can be known about the giant monsters. Following Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock’s suggestion that the invisibility of the monster challenges us “to extend vision temporally and to augment it prosthetically” (

Weinstock 2020a, p. 371), media in the

MonsterVerse are entangled with “proving” the threat of the (in)visible.

2. Monitoring Monsters: Media as Technologies of Detection

General Puckett: “This is gonna give me nightmares.

But until you show us what made this, a

Footprint is just a hole in the sand.

You couldn’t at least get me a photograph?” |

(Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, Episode 3)

While the giant monsters of the

MonsterVerse, toppling skyscrapers and resembling prehistoric creatures in spectacular fight scenes, do not necessarily fall into what Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock calls a “contemporary disconnection of monstrosity from physical appearance” (

Weinstock 2020a, p. 359), their existence becomes increasingly a question of documentation. In her extensive overview of disaster films, Nicole Schröder differentiates between two types of media: “those media which collect data in order to observe and, in a sense, control nature” and “the mass media, which capture and multiply images of the catastrophe and spread them around the globe” (

Schröder 2010, p. 300). In line with this categorization,

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019)

2 begins with a compilation of news segments documenting both “the day the world discovered that monsters are real” on the five-year anniversary of Godzilla’s emergence in 2014 and the larger changes to the world’s ecosystem since then. While the former draws a chronological connection to the spectacle of the previous film, the images used for the latter traverse the line between fiction and reality. Writing on

Godzilla (2014), Geoff King argues that the use of media within the film’s narrative decreases the “distance between the spectator-as-consumer-of-spectacle and those depicted on the screen” (

King 2019, p. 163). Expanding on these existing discussions of meta-media in disaster and science fiction films, I suggest that the focus lies increasingly not on the presentation of these media and mediated images but their production. Tasked with not only representing the monsters’ destruction but rather documenting, recording and visualizing their existence, media in the

MonsterVerse become technologies of detection. For the threats in the

MonsterVerse, there are always signs—if one only knows how to recognize and read them.

Not uncommonly for science fiction and disaster films, the

MonsterVerse features a variety of technologized “operation rooms” covered in screens displaying news coverage, scientific measurements and mediated surveillance in a spectacle of mediation. Somewhat uniquely though, both the films and the series place an emphasis on visualizing the multiple sources and origins of the information displayed in these rooms. In the

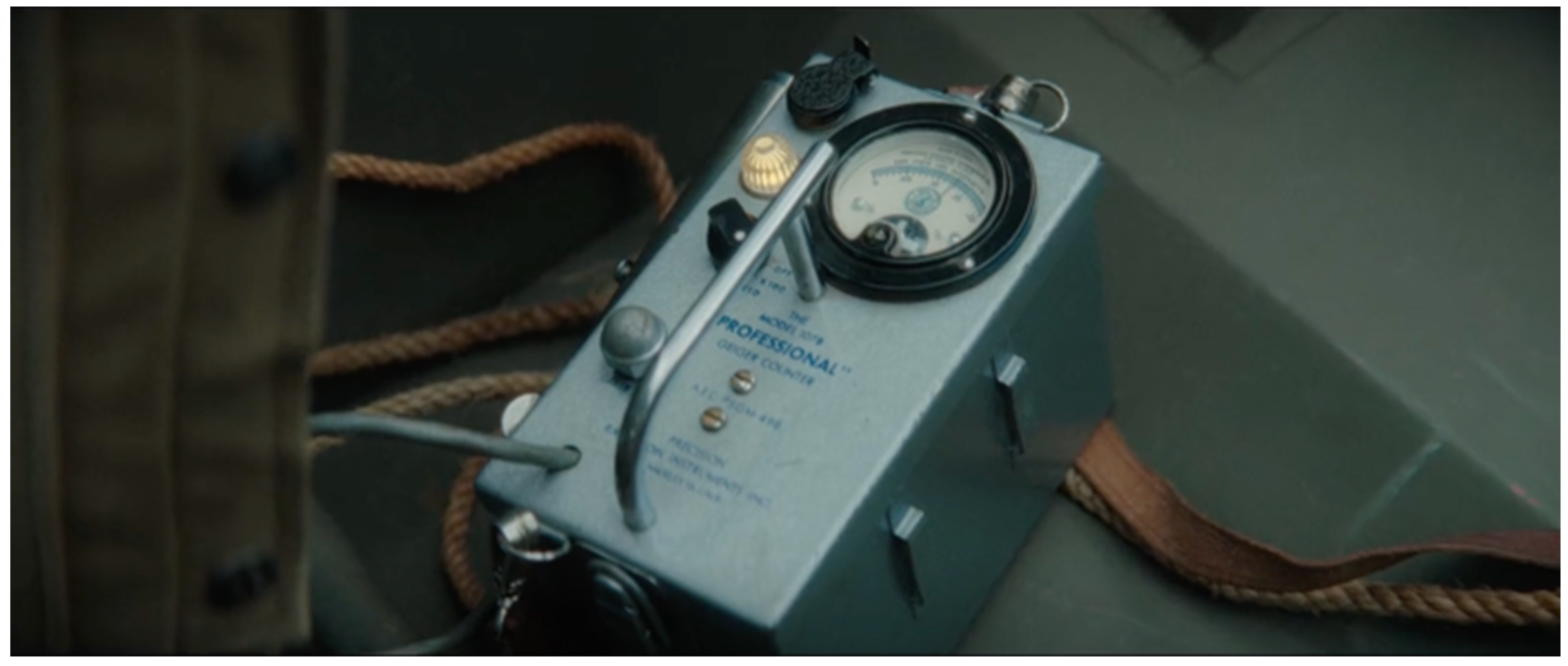

MonsterVerse, Godzilla and the other monsters both feed on and emit specific radioactive signatures—which are, importantly and realistically, invisible to the human eye. Foreboding the monsters’ presence, then, includes an emphasis on the recognizable audiovisual ticking of the Geiger counter (

Figure 1) and more complex setups, with the protagonists unpacking technological systems, connecting cables and observing changing lines and patterns on a variety of monitors. Increasingly complex, these technologies document not just the existence but rather the escalating proximity of the giant monsters despite their invisibility, a threat that becomes sensible through technology before its physical emergence. While the television series focuses predominantly on detecting radioactivity, the films also extend their experimentation with ways to measure the presence of the monsters. For instance,

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) centers on bioacoustics—including the heartbeat and “sentiment” of Godzilla. Invisible (radioactivity) and inaudible (bioacoustics), these indicators of a monstrous presence need to be technologically mediated to become visible, audible, sensible to the humans both within the narrative and in front of the screen. The bioacoustic signatures, unintelligible shrieks,

3 must be made readable both for the protagonists within the film and the audience outside of it. This corresponds to what Susan Sontag has called science fiction films’ invitation of “a dispassionate, aesthetic view of destruction and violence—a

technological view” (

Sontag 1965, p. 45—emphasis in original). Or, as Lee Shaw phrases it in the first episode of

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023): “Time for some science shit.” Some of these technologies push the idea of detection even further: In

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023), Japanese scientist Dr. Suzuki develops a “gamma radiation simulator” that functions as a call-and-response setup, with the pulses of radiation bringing the giant monsters, including Godzilla, from Hollow Earth to the surface and vice versa. Following a similar idea, though based on a different form of simulation,

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) centers on the bioacoustics sonar sampler and amplifier ORCA, which functions as a replica of the bioacoustic commands of Titans—and either attracts or subdues them, depending on the set frequency. More than just a mode of documentation, these technologies function as active interventions—making the giant monsters of the

MonsterVerse not just visible through graphs, lines and pulses but conjuring their physical presence.

As one of the first official finds of Monarch, at this point in the timeline a small, semi-independent research team, Bill Randa, Lee Shaw and Keiko Miura present a “footprint” taken out of the mud in a field in Indonesia to the United States military as embodied by General Puckett. The general’s response reflects two larger themes recurring through the series: “How does something this big walk around without being seen?” and “You couldn’t at least get me a photograph?” While each film features protagonists connected to scientific and military institutions—including Monarch—it does become noticeable that the films also introduce leading cast members either as or through their work with different media, from (anti)war photojournalist Mason Weaver in

Kong: Skull Island (2017), animal behavior scientist turned wildlife photographer Mark Russell in

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) and podcaster Bernie Hayes in

Godzilla vs.

Kong (2021) and

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (2024) to digital-visual artist Kentaro Randa in

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023). Increasingly, the

MonsterVerse not only features but frames Godzilla—and the other monsters—through an extended timeline of media recording, tracking and documenting their existence.

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023) even begins with a recording, visualized as grainy footage, of Bill Randa’s expedition to Skull Island in 1973.

4 Caught in the fight between two giant monsters, Mother Longlegs and Mantleclaw, the scientist’s concern does not necessarily seem to be his own survival—but rather that of his visual “evidence”. Protected in a Monarch-branded satchel against the rough waters of the Pacific, the documentation of the expedition—including the grainy video message—resurface off the coast of Japan in 2013 in the series’ opening like a scientific message-in-a-bottle. This prologue does not only set up a recurring plotline throughout the series’ eight episodes about understanding and decoding these materials, but also points to the series’ theme of repeating and doubling media.

Rather than providing more and more visualizations of the monsters’ presence, the

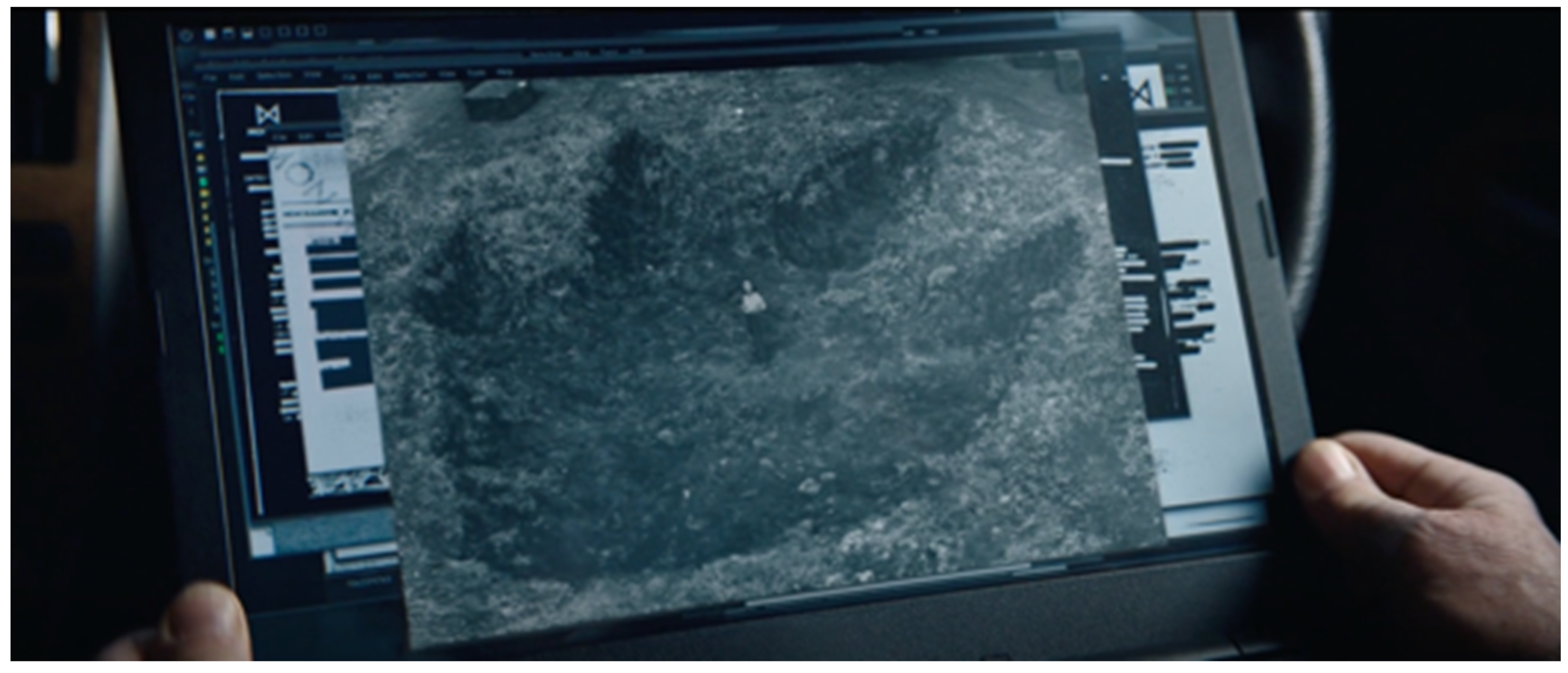

MonsterVerse increasingly features the same “evidence” in different media formats. For instance, the muddy footprint, not convincing enough for the American military in the 1950s, returns in the series’ 2015 timeline in the form of a photograph of Keiko Miura standing in the “original” footprint in Indonesia (

Figure 2). Importantly, the series does not feature the actual discovery of the footprint—or the monster leaving behind this trace—thus leaving the audience, as much as the disbelieving military representatives in the narrative, with “only” mediated evidence. Between the films and the series, however, the media doubling appears to counter exactly this gap. A recurring reference made throughout the films is to the Castle Bravo nuclear tests of the 1950s: the opening sequence of

Godzilla (2014) features documents and maps of Bikini Atoll—the real site of the tests—as well as a compilation of grainy footage of Godzilla’s dorsal plates moving through the water, a nuclear bomb featuring a drawing of Godzilla and the bomb detonating over the ocean. Similarly, and with an undercurrent of conspiracy, Bill Randa insists in the opening scene of

Kong: Skull Island (2017) that Castle Bravo was not a nuclear test but an attempt to “kill something out there” by the American military. What is presented as “historical” documents—and blended with actual history—in these opening sequences is repeated “live” in the past timeline of

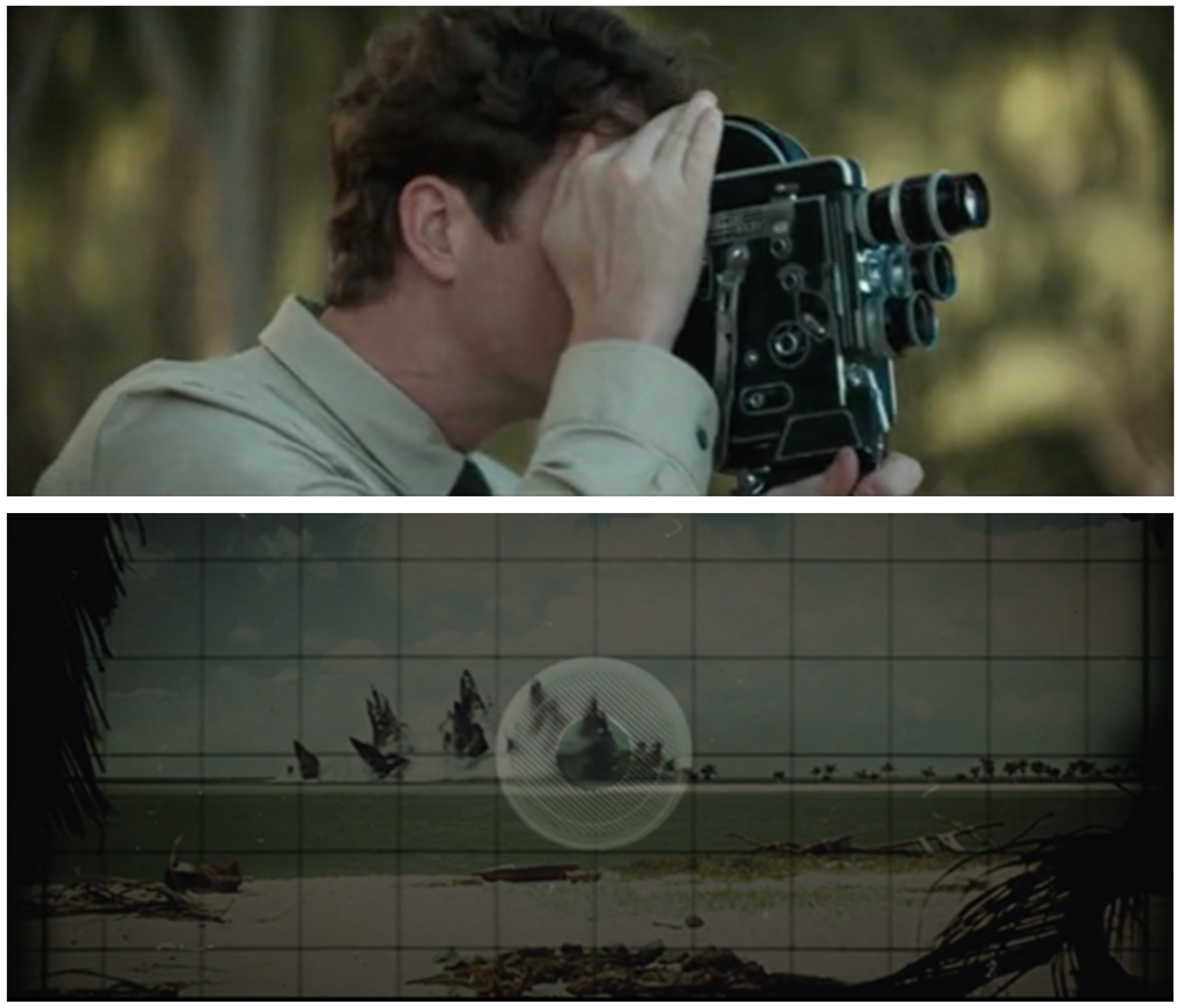

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023). The series extends the partial and disrupted footage of the film’s opening sequence into a continuous scene, in which Godzilla is shown quite literally staring down the bomb—before vanishing into the depths of the ocean, seemingly defeated by the technological superiority of the American military. More than just witnessing this encounter as a live and immediate spectacle, the series emphasizes the efforts of both the scientists and soldiers present to document the existence of—and assumed victory over—Godzilla through reports, photographs, sound and video recordings (

Figure 3). In doing so, the

MonsterVerse complicates the usual temporality of media within science fiction films, in which “a mediated vision is presented in order that it can be transcended by what is an apparently more direct or ‘authentic’ view of the action” (

King 2019, p. 164). Rather, the use of media within the

MonsterVerse focuses on both detecting the monsters and detecting the mediated evidence of their existence—in a continuous loop of detection and disappearance of both the monsters and the evidence of their existence in and across the installations of the

MonsterVerse.

3. Mapping Presence: Monsters in Time and Space

Bill Randa: “Well I know that you are not gonna find what’s

out there following a Geiger counter”.

Keiko Miura: “What should we be following, Mr. Randa?”

Bill Randa: “[…] I think you should be following the stories. Folklore. Legends”. |

(Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, Episode 1)

The historic “tendency to locate monsters at the edges of the earth” (

Van Duzer 2017, p. 391) becomes complicated through an increasingly mapped world: in an age of satellites and geolocation, the spaces outside of human—or technological—view increasingly disappear. The

MonsterVerse responds to this by venturing into the Hollow Earth, the “birthplace” of the Titans and a realm existing below and in parallel to the Earth’s surface. Traveling between Earth and Hollow Earth through a complex network of appearing and disappearing vortexes, Godzilla, Kong and the other Titans exemplify that monsters “can be pushed to the farthest margins of geography and discourse, hidden away at the edges of the world and in the forbidden recesses of our mind, but they always return” (

Cohen 1996a, p. 20). Hiding, waiting, lurking beneath the surface in the Hollow Earth, the giant monsters of the

MonsterVerse are—paradoxically—invisible and hypervisible, absent and present at the same time. The danger seems to be less that “anyone could be a monster” (

Weinstock 2020a, p. 363) and more that

anywhere could be a monster—and a giant one at that. Expanding on media as technologies of detection discussed in the previous section, the

MonsterVerse responds to the (in)visibility of its monsters with an emphasis on cartography: through the material form of the map, the presence of the monsters is written into both time and space.

Writing on the inclusion of monsters in medieval maps both through monstrous drawings and inscriptions like “hic sunt dracones”,

5 Chet Van Duzer argues that the “description and representation of distant monsters involves an intriguing tension between helplessness and control, between surrender and power” (

Van Duzer 2017, p. 389). Mapping the presence of monsters, in this regard, functions both as a practical warning about spaces to avoid (or at least to approach with utmost caution) and as a political negotiation of knowledge and understanding. While there are recurring storylines based on “finding” monsters with and through different maps—both analog and digital, hand-drawn and high-tech—the

MonsterVerse also highlights the complex process of mapping itself. Not coincidentally, both Houston Brooks (played by Corey Hawkins) in

Kong: Skull Island (2017) and Nathan Lind (played by Alexander Skarsgård) in

Godzilla vs.

Kong (2021)—the two films in the

MonsterVerse that explicitly set up and engage with the Hollow Earth theory—are presented as geologists and cartographers. Drawing on Bieke Cattoor and Chris Perkins’ work on alternative atlases, Sébastian Caquard and William Cartwright underline the “importance of designing alternative maps and atlases that destabilize audiences ‘in order to show possibilities’, to ‘offer important new ways of imagining our futures’ and to challenge some of our assumptions” (

Caquard and Cartwright 2014, p. 104). At the same time, it should be pointed out that these destabilizing maps—as well as other scientific technologies of detection and documentation—and the people devising, developing and defending them are initially represented as discredited and/or disreputable within the

MonsterVerse. For instance, Houston Brooks’ theories on seismology, developed as part of his college thesis, are entangled with an attitude of disillusionment with Monarch as an “unfundable” research institution in the 1970s in

Kong: Skull Island (2017), while Nathan Lind is introduced as an obsessed and academically ridiculed “sci-fi quack trading in fringe physics” in

Godzilla vs.

Kong (2021). The temporal disconnect between their research—in 1973 and 2021, respectively—highlights that an unmapped Hollow Earth remains hypothetical and thereby questionable, at least from a geological perspective. Even beyond these explicit professional identities as geologists, I suggest that the protagonists in the

MonsterVerse can be understood more generally as modern iterations of the medieval cartographers chartering unknown—and maybe unknowable—lands.

Interestingly, the giant monsters appearing throughout the

MonsterVerse (and in Kaiju media at large), from the three-headed dragon Ghidorah and the crustacean Scylla, named after the mythical Greek sea monster, in

Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) to the more general idea of “monster islands” like the titular

Kong: Skull Island (2017), could also be found on these medieval maps. The underlying question of how to map something beyond our direct experience similarly resonates in the cartographic approaches in the

MonsterVerse. While the technological mediation of radioactivity, electromagnetic pulses and high-frequency sound waves registers the monsters in the

MonsterVerse in their moment of emergence (or, hopefully, slightly before), a longer and deeper understanding of their world(s) becomes only accessible by turning to folklore and legends. Keiko Miura and Bill Randa only find the first monster in

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023)—in the show’s second episode—once they overlay the graphs of radioactive isotopes measured by Miura with the oral histories “going back centuries” collected by Randa (

Figure 4). Resonating with what Sébastian Caquard and William Cartwright refer to as “the narrative power of maps” (

Caquard and Cartwright 2014, p. 104), the series highlights the connection between map and myth in negotiating the “real”.

At the same time, these legends—while seemingly true or at least versions of the truth—do not consistently hold up as evidence outside the group of scientists collecting them. One of the critiques Keiko Miura brings up against cryptozoologist Bill Randa’s field notes and research data is that they consist of “second-, third- and fourth-hand accounts with no corroborating evidence” (Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, Episode 8). Only once these accounts, both individual memories and folklore, have been turned into the form of a map, following the expected scientific standards of representation, does the “data” become convincing for the institutional decision-makers deciding on Monarch’s future (and funding). The map, in this regard, does not only function as a way to find the monsters but rather to inscribe their presence in a material, scientific, authoritative form. The map, more than the story, commands factuality.

4. Materializing Truth: Analog Media and Materials “For Eyes Only”

Taxi Driver: “San Francisco was a hoax. They did it with CGI.”

Cate: “Well that’s … quite a revelation.”

Taxi Driver. “There’s more. I have a podcast!” |

(Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, Episode 1)

The dialogue featured as the introduction to this section, between Cate Randa and an unnamed taxi driver, during one of the first scenes in the series’ first episode, highlights how the reality of living with monsters has seeped into the everyday, becoming an acceptable and almost automatic topic of small talk with strangers. Arguably, it does something else as well. Notably, the destruction in

Godzilla (2014), the starting point of the

MonsterVerse franchise, is focused on San Francisco—not Tokyo. The series, however, presents a version of Tokyo a year later, decked out in missile defense systems and drone surveillance, Godzilla evacuation routes and underground bunkers in the transit system. The images of destruction, relayed through media across the Pacific Ocean, are operationalized to create further systems of technological and military surveillance—and maybe precisely for that reason become questioned by the general public in the

MonsterVerse. Watching the monster on the screen, it appears, does not materialize its threat in an age of image generation. The “Doomsday Clock”, referenced in the introduction of this article, also engages with this development explicitly, stating that artificial intelligence “has great potential to magnify disinformation and corrupt the information environment on which democracy depends” (

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 2024). This connects back to a larger conceptual understanding of the monster’s role as keeping “competing discourses of the real an active and open register, even in an age of transparency, technology, and information saturation” (

Dendle 2017, p. 448). With the emphasis on flashbacks to different time periods—including the 1940s in

Kong: Skull Island (2017), the 1950s in

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023) and the 1990s in

Godzilla (2014)—this not only appears to be about the mediatization and mapping of the monsters but rather their analogization. Captured in hand-drawn maps, grainy images and static sound recordings, proving the existence of the monstrous threat becomes a question of materiality as well.

As is not uncommon for science fiction films (cf.

Sontag (

1965) for an early discussion of giant monsters in film), the

MonsterVerse features a recurring plotline of scientists not being believed due to an absence of concrete and convincing evidence for their prophetic warnings—from Bill Randa’s theory about the existence of Hollow Earth in

Kong: Skull Island (2017) and nuclear physicist Joe Brody’s insistence that “something is out there” in

Godzilla (2014) to the first scientific recordings of the MUTOs in

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023). In their attempts to prove their theories, the

MonsterVerse creates a clear dichotomy not only between first-hand and mediated witnessing, but also between digital and analog media. More than digital recordings and visualized projections, it is physical, material, analog media that function as evidence—from handwritten diaries to floppy disks and developed photographs. The character of Bernie Hayes (played by Brian Tyree Henry)—blogger and self-proclaimed whistleblower behind the semi-obscure “Titan Truth” podcast—corresponds to an understanding that science fiction films “reflect world-wide anxieties, and they serve to allay them” (

Sontag 1965, p. 42) by functioning as both accidental prophet and comic relief in his paranoia in

Godzilla vs.

Kong (2021) and

Godzilla vs.

Kong: The New Empire (2024). Despite constantly referencing digital technologies and networks, Bernie Hayes takes polaroid pictures and records videos, selfie-style, on both a retro flip phone and handheld video camera. This does not only underline that the monster is, in effect, able to escape the seemingly ever-present and always-live gaze of digital technologies in a contemporary media landscape, but also creates a hierarchy of trustability across different media. Printed on paper, captured on cassette tapes and saved on SD cards, these non-networked technologies, it appears, provide the more believable, more real evidence of unbelievable encounters. In the disaster films of the 1990s and early 2000s films, Nicole Schröder finds an emphasis on “filming and commenting

live on the catastrophe” (

Schröder 2010, p. 300). While there are scenes featuring broadcast media and breaking news, the

MonsterVerse creates a temporal and spatial distance between the event and its mediation in the narrative structure. With an emphasis on redacted documents, secret recordings and classified photographs right from the first scenes of

Godzilla (2014), the

MonsterVerse constructs the idea that somebody

was there live in the moment but that the material evidence of what actually happened has been accidentally lost—or actively hidden.

6 For instance, the pictures investigative photojournalist Mason Weaver takes of Kong, the monstrous “Skullcrawlers” and the hidden civilization on the titular

Kong: Skull Island (2017) in the 1970s are never made public within the narrative universe. In the film’s final scene, which presents a serene and scenic paradise under Kong’s protection, Weaver responds to a somewhat melancholic statement about the island inevitably changing—“Word will get out. It always does”—with a resolute promise that it will not be the expedition crew telling the world about their monstrous encounters. A similar sentiment is repeated in

Godzilla vs.

Kong: The New Empire (2024), with blogger Bernie Hayes deciding not to use the video recordings of his time in Hollow Earth—even if they would confirm his claims, otherwise so easily dismissed as paranoid conspiracy theories.

The notion that material media reveal (more) truth about the monsters’ existence becomes most striking in the opening sequences that expand across the films. The opening sequence of

Kong: Skull Island (2017) moves from December 1945 forwards, with specific moments in time—in the rotating letters of a news board—used as an overlay over historical media recordings: a video of the victory speech of President Harry S. Truman blending with “home videos” of American suburbia in the 1950s, recordings of the “Bravo” detonation in the Castle series of nuclear testing conducted by the United States government over Bikini Atoll blending with scans of (seemingly) official documents outlining monstrous sightings. In doing so, the film constructs a linear historical timeline in which the “real” blends with the “fictional” not just through the narrative structure but—maybe more importantly—through the blending of media formats. The superfilm aesthetic, film rolls flickering and glitching behind slightly metallic sound recordings, adds a sense of historicity superseding concerns of digitally augmented images. While the title sequences of the following films do not follow the exact same “linear” structure, the references to analog media as material evidence for the present threats continue. Or, as Jeffrey Jerome Cohen has argued, “the monster haunts; it does not simply bring past and present together but destroys the boundary that demanded their twinned foreclosure” (

Cohen 1996b, pp. ix–x). Either invisible to or unbelievable in the digital media of the present, the

MonsterVerse returns to both technologies and mediations of the past to materialize the monsters’ existence—while at the same time emphasizing that material evidence in itself is always vulnerable to disappearing.

5. Conclusions

If “the monster polices the borders of the possible” (

Cohen 1996a, p. 12), then the

MonsterVerse also polices the borders of the visible, knowable, sensible. More than just being “concerned with the aesthetics of destruction, with the peculiar beauties to be found in wreaking havoc, making a mess” (

Sontag 1965, p. 44), this article has argued that the

MonsterVerse pays an increasing attention to documenting, recording and mediating this destruction—and its causes. Expanding on existing discussions of meta-media in science fiction films, the

MonsterVerse highlights media as technologies of detection. Initially charged with tracing the monster through its resonances—like radioactivity or bioacoustic signatures—the same media technologies also contain the potential to conjure the physical presence of the monster. In a recurring loop, both within the series and across the larger narrative universe, the extended invisibility and momentary hypervisibility of the monster follow each other, constructing an ever-present threat

somewhere. Expanding from monitoring to mapping monsters, the emphasis on cartography extends the temporality of the monster’s existence: The myths and legends of (more) monstrous histories are quite literally written into the space of the present through the map. In doing so, the map also simultaneously challenges and reinforces registers of factuality. Between monitoring the present and mapping the past, media are entangled with making the invisible visible—and the unbelievable believable. Following the idea that media “remediate the past in order to premediate the future” (

Grusin 2004, p. 23), the doubling and echoing of media across the complex temporality and spatiality in the

MonsterVerse not only constructs the idea that monsters are “everywhere” (

Weinstock 2020a, p. 366)—but also that they have been and always will be. Throughout the films, the mediatization of the monster’s existence expands further and further, even including cave paintings in the latest installment

Godzilla vs.

Kong: New Empire (2024). Entangled in the logic of somewhere-always and everywhere-sometimes, the monster is conjured as a threat that

can—but not always will be—seen, known, felt. Monitoring, mapping and materializing the giant monster then functions as a negotiation of the threatening (in)visibility of the monster despite—or maybe also because of—its mediation.

While this article places an emphasis on these themes in the television series

Monarch: Legacy of Monsters (2023), the threat of the (in)visible can also be traced in the

MonsterVerse at large—and arguably also in other contemporary science fiction media. While not the focus of discussion here, the most recent Japanese installment in the Godzilla franchise,

Godzilla Minus One (

Yamazaki 2023) should be mentioned not just for its temporal setting in 1947 (with a narrative prologue in 1945). In the seemingly happy end of the film, the female protagonist of the film, Noriko, is implicitly “infected” with Godzilla’s monstrous DNA (

Colbert 2024, n.p.)

7—thereby presenting another invisible threat. As the film’s camera lingers on the ominous black mark on her neck, the “invisibility and potential ubiquity” (

Weinstock 2020a, p. 359) of contemporary monstrosity is simultaneously enacted and undermined. Bridging discussions in monster studies and media studies, I have attempted to highlight how making the monster visible, audible, sensible is simultaneously presented as the promise and problem of technological mediation. The multiplication and repetition of the same event in different mediations not only functions as a connecting element of the films and series within the

MonsterVerse, but also creates the impression that there is always another viewpoint to be revealed—or rediscovered. Read through the lens of truth and trust, the emphasis on monitoring, mapping and materializing the giant monster in the

MonsterVerse resonates with contemporary anxieties both in regard to technology and their larger socio-political contexts. As both giant monsters and their mediations appear and disappear, even that which has been

made visible through technologies of detection and documentation has the risk of

becoming invisible again through practices of control and censorship. Interweaving historical events in the fictional narrative, the

MonsterVerse positions media as vulnerable: digital media are presented as vulnerable to manipulation, whereas material media are vulnerable to destruction—or at least redaction. While it is not necessarily new to read the monster through the lens of conspiracy (cf.

Weinstock 2020b), the emphasis on the role of mediation to reveal and conceal the monster’s presence in the

MonsterVerse adds a further dimension. While other science fiction films arguably “draw attention to the fact that the media, to a large extent, determine what kind of world we look at and how we see it” (

Schröder 2010, p. 302), the

MonsterVerse highlights what we cannot see—or what the media do not show us. At the same time, the continuous reference to and use of materials marked as “for eyes only” envelops the audience in this exclusive group of people in the know: the notion that the truth is and has been out there (if you just know how to find it) at the same time plays with and rewards a paranoid disposition. Tellingly, the official Twitter/X account linked to the

MonsterVerse, @MonarchSciences, now features the tagline “This account no longer belongs to Monarch. It belongs to the truth. Soon, the rest will surface” (@MonarchSciences).