Abstract

The following article examines the role of the sentidos and the entendimiento in Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s auto sacramental, El cubo de la Almudena. While scholarship recognises the pervasiveness of the play on the senses in early modern Spain, scholars often either deny or overemphasise the reliability of the senses as a means of truth acquisition. Moreover, scholarship often attaches too much weight to hearing, thus neglecting the role of the eyes of the entendimiento. Based on a Thomistic framework, Calderón demonstrates that the literal element of allegory relies on the active vehicle of the senses to serve as guides for the entendimiento and an entrance into devotion. Although hearing plays a central role in the play, it serves as a herald for sight, by which the devotee exercises faith. Moreover, where the sentidos prove limited, the entendimiento is an auxiliary support that makes up for their lack, seeing beyond sensual perception through faith. In this way, the medium of the auto sacramental and the theology of the Eucharist train the audience to use the vision of faith through both the senses and the entendimiento to see the allegorical meaning of the play, the divine nature of the Eucharist provided by Mary.

1. General Introduction

The characterisation of the arts of the Spanish Baroque as a spectacle for the senses is universally understood among scholars of the early modern Hispanic world. In the world of theatre, as María Alicia Amadei-Pulice describes, Pedro Calderón de la Barca transforms Aristotelian admiration—through new technological and theatrical innovations like apariencias and tramoyas for lifting and sudden appearances—creating a spectacular feast for the senses, especially sight and hearing (Amadei-Pulice 1990, p. 41). Indeed, the autos sacramentales (autos) of Pedro Calderón de la Barca are a quintessential example of the all—encompassing play of the senses in Baroque theatre through an intermixture of religious ritual and drama performed for the feast of Corpus Christi in honour of the Eucharist. Yet it seems incongruous to utilise the medium of the senses for promoting Eucharistic devotion when the Eucharist is incomprehensible to the senses alone. The Aristotelian substance–accidents distinction of the Eucharistic doctrine of transubstantiation holds that the accidents of bread and wine veil the divine nature of Christ’s body and blood (the substance). Consequently, the use of the senses for perceiving Christ’s divinity would be impossible without an extrinsic aid.

In El cubo de la Almudena (Calderón de la Barca 2004), Calderón demonstrates at once both the necessity of the senses for Eucharistic devotion as well as the requirement of an ‘interior’ sense that sees beyond what the senses see: the eyes of the entendimiento [the intellect]. For Thomas Aquinas, the entendimiento is a power of the soul for making something intelligible by making an intellectual act [Latin: intelligere] (Aquinas 1981, 1.79.1.; Kenny 1993, pp. 41–42). It receives material information from the senses in order to make this act of understanding (Aquinas, 1.84.6). As an interior sense, the entendimiento retains the information presented by the five senses—the exterior senses—by means of the imagination (1.78.3). The entendimiento relies on the senses, but also acts beyond them through intellectual activity since they cannot provide the fulness of truth on their own (1.84.6). Calderón follows Aquinas by highlighting how the entendimiento assents to belief in this auto (2—2.1.4; 2—2.6.1). When guided by faith, the entendimiento is an auxiliary to the senses that provides the spectator—reader with a special means of perceiving the divine nature of the Eucharist, perfectly compatible with the theatrical medium of the auto.

This auto was originally performed in 1651 and is based on the legend of the Virgin of the Almudena (Shergold and Varey 1961, p. 103). The legend recounts that a Marian image was discovered when King Alfonso VI retook Madrid in 1083 (Quintana 1629, fol. 60r). It had been hidden inside of the cubo [tower] of the wall near the church in Madrid during the time of the Goths to protect it from the invasion of the Moors (Quintana, fol. 60r). Discovered after the townspeople performed a solemn procession, ‘implora[ndo] el favor divino’, to discover the hidden image, Jerónimo de Quintana, a contemporary of Calderón, retells that that very night, ‘se cayó un gran pedazo de muro cercano al cubo que tanto tiempo había sido custodia y relicario de esta preciosa imagen’ (Quintana, fol. 61v). This caused the cubo to open and reveal the Marian image, to which the townspeople ‘[miraron] con gozo y admiración de los presentes la causa de tan prodigioso suceso, que era el haber querido Nuestro Señor descubrir esta santa imagen, condescendiendo a sus piadosos ruegos’ (Quintana, fol. 61v.). The image of the Virgin gained its name since the cubo was next to a house that the Moors called ‘almudena’, which, as Quintana describes, ‘en nuestro español es lo mismo que alhóndiga o alholí, donde tenían trigo para provisión del lugar’ (Quintana, fol. 61v). Later, after Alfonso VI’s death, Ali ben Yuçuf besieged Madrid in 1111 (Fradejas Lebrero 1959, p. 44). After the townspeople’s prayers to the Almudena, she did not allow any of the Moors to climb the muro [wall], and brought a pestilence upon them (Fradejas Lebrero, p. 45). Finally, the legend holds that in 1197, the King of Andalucía, Abderramán II, surrounded Madrid and tried to starve the peoples. The townspeople sought the intercession of the Virgin by venerating the sacred image. They were then miraculously provided with wheat:

andando unos muchachos en la Iglesia hicieron un agujero en un pilón por donde empezó a salir trigo y admirados de tan notable prodigio, abrieron la pared donde hallaron milagrosamente grande cantidad que el lugar se abasteció y el moro levantó el cerco, viendo que le arrojaban trigo y que no se podían rendir por el hambre.(Bravo Navarro and Sancho Roda 1993, p. 25n74)

The Virgin was attributed to have heard the cries and protected the townspeople from starvation because they implored her image. This event reflects Mary’s role as a participant in salvation because she gives birth to Christ. Since Christ is believed to reveal himself in the Eucharistic bread, Mary is credited, in line with patristic tradition, as the provider of wheat.1 These miraculous tales associated the statue’s protection of the people and supply of grain with Mary’s provision of the Eucharistic host through the birth of Christ.

In the text of the auto, Calderón embellishes these legends and situates the auto during the attack of the Moors in Maderit after Alfonso’s death in 1109.2 The plot unfolds as follows:

- When Oído is informed of the news, Iglesia prepares a plan of defence, giving each of her soldiers, the five sentidos [senses], jobs to defend the muralla.

- Apostasía (symbolic of Protestantism) appears, claiming to be part of Iglesia’s army, but Iglesia is suspicious of the orthodoxy of her faith.

- After Iglesia and her soldiers win the first attack against their assailants, Apostasía joins Iglesia’s enemies. Apostasía then interrogates the sentidos about the nature of the Eucharist to confound them and the Entendimiento, and seize Entendimiento and the Eucharist.

- The sentidos sing ‘Ave Maria’ to plead for Mary’s help in battle, and take on the assailants. Oído challenges Apostasía and Entendimiento, and recaptures Entendimiento through logical discourse.

- Although Apostasía is weakened by Entendimiento’s retreat, she plans to climb the muralla once more with the other enemies to enter the cubo and starve the faithful of wheat. When they are mysteriously prevented from climbing, the muralla begins to crumble.

- As the sentidos are starving of hunger, they pray for Mary’s intercession through song until her image miraculously appears from the rubble. The Eucharistic host is then revealed to sustain them and cause the enemies of the Church to retreat.

2. Purpose and Scholarly Overview

Utilising a close—reading methodology of the auto’s allegory and equipped with a Thomistic framework, we will examine how Calderón demonstrates that the literal element of allegory relies on the active vehicle of the senses to serve as guides for the entendimiento and an entrance into devotion. Moreover, where the sentidos prove limited, the entendimiento is an auxiliary support that makes up for their lack, seeing beyond sensual perception through faith. Although hearing plays a central role in the play, it serves as a herald for sight; Calderón prizes sight for augmenting devotion through the means of the entendimiento. In this way, the medium of the auto and the theology of the Eucharist train the audience to use the vision of faith—through the sentidos and the entendimiento—to see the allegorical meaning of the play, the divine nature of the Eucharist provided by Mary.

While scholarship recognises the pervasiveness of the play on the senses in this period, scholars often deny the reliability of the senses as a means of truth acquisition. Firstly, the epistemic pessimism attributed to the Baroque period is often obfuscated and results in a misunderstanding of the role of the entendimiento and the material world perceived by the senses.5 Stephen Gilman posits that ascetic influence during the Counter—Reformation resulted in ‘hatred’ of the material world and distrust of the senses in favour of a blind embrace of the entendimiento (Gilman 1946, p. 92). While Gilman rightly acknowledges that asceticism played an important role in Christian teaching, he creates a false binary that places the entendimiento and the senses in opposition. This caricature of the Baroque has persisted in more recent scholarship with Fernando De la Flor, who considers the authors of the Baroque to hold an ‘odio al cuerpo’, which destabilises humans from ‘un mundo menospreciado y engañoso’ (De la Flor 2002, pp. 31, 46). Such scholarship considers the senses to be inimical to perceiving reality in the Baroque framework, resulting in a skewed understanding of the entendimiento and of the value of the perceptual realm.

In contrast, this article seeks to elucidate how Calderón does not deny the senses and material world in favour of a disembodied spirituality, but rather characterises them as vehicles for prayer. According to Fernando Checa Cremades and José Miguel Morán Turina, the Spanish mystics of the sixteenth century upheld the image in contrast to Protestants, heartily affirming the use of the senses: ‘Los fines, pues, de la imagen sagrada son excitar la devoción, despertar nuestra atención o enternecer nuestra sensibilidad […] La discusión fundamental gira en torno al papel de los sentidos en la contemplación de las imágenes’ (Checa Cremades and Morán Turina 1982, p. 212). The senses were often harnessed through sacred images for sparking prayer, and were encouraged for use by mystics like St Ignatius, St Teresa of Avila, and St John of the Cross alike. The senses can create a bulwark for faith and virtue as they perceive material objects that promote piety to protect the soul. Because the Eucharist relies on the allegorical framework of the sacraments—as I will expound on below—Calderón utilises the senses in the Eucharistic auto as co—workers with the intellect for engaging in the divine.

On the other hand, scholars have also attached too much weight to the senses in Calderón. Amadei-Pulice observes, for example, that ‘la experiencia de los sentidos va a ser la única guía del dramaturgo barroco y del espectador teatral’ (p. 42). This notion considers the senses to be self—sufficient for relaying truth in Baroque drama. As such, it overlooks the limitations of the senses—which Calderón himself accounts for—and devalues the entendimiento.

Additionally, scholarly discussion often centres on the debate between hearing and sight in Calderonian scholarship, generally concluding that Calderón privileges the former over the latter. While María Luisa Lobato recognises the difficulty of accounting for the value of one sense over the others in Calderón, she yet notes that great importance is given to the ‘oído’ for ‘conocimiento de las verdades de la fe’ in the autos (Lobato 2002, p. 610). José María Díez Borque also concurs that ‘Calderón considera más importante el sentido del oído’ for faith (Díez Borque 1983, pp. 621–22). While I agree with these scholars on the primacy of hearing for Calderón, overemphasis of this sense over vision detracts from the importance of the optics of the entendimiento, which operate together with the senses in order to apprehend reality. I offer that Calderón not only privileges the senses as a means of informing the intellect, but that he also considers the entendimiento to play a role in imparting the sight of faith to the spectator—reader in El cubo de la Almudena.

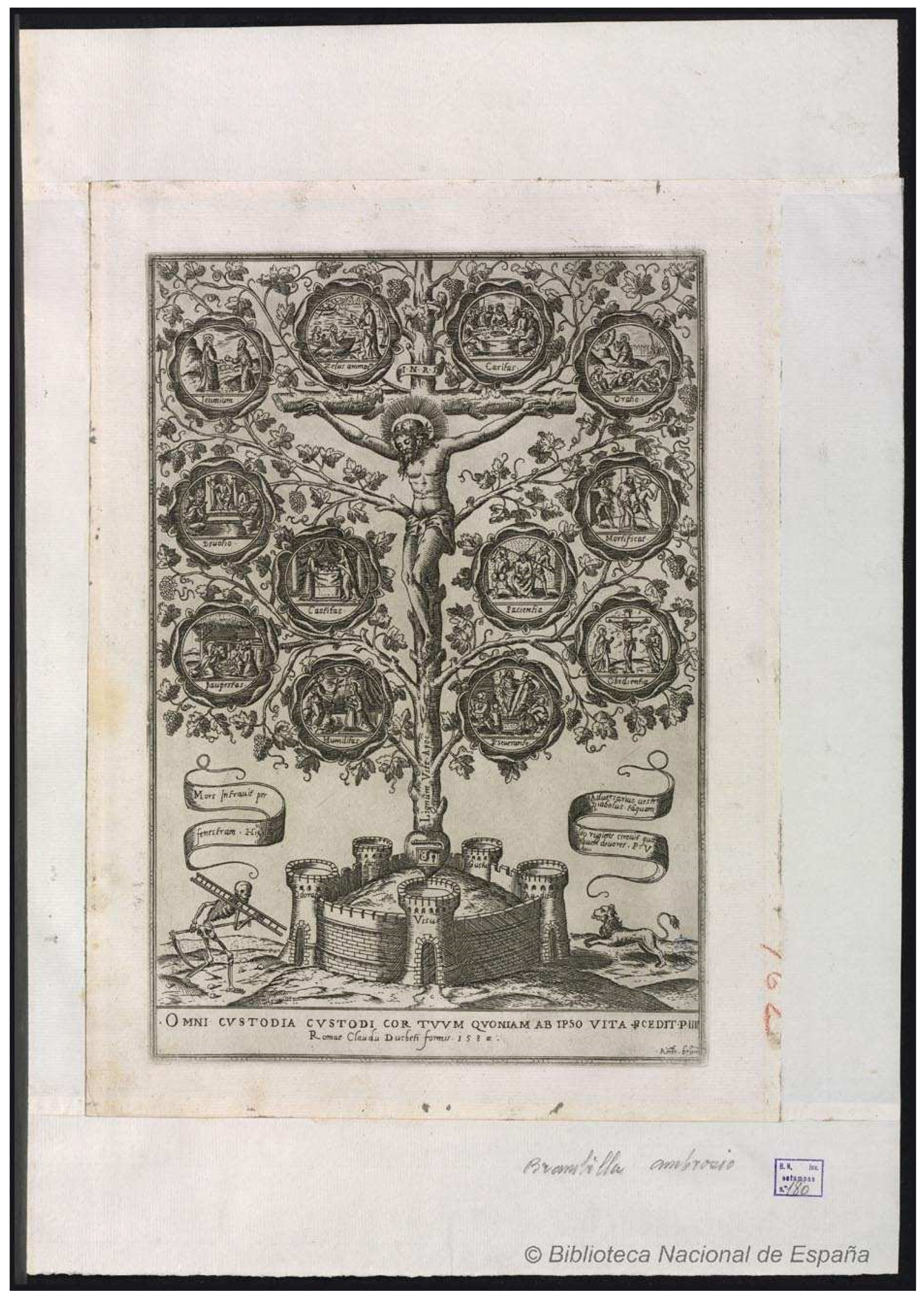

The following image (Figure 1) illustrates the early modern understanding of the role of the senses for faith. This sixteenth—century Italian woodcut depicts the five senses within the towers of a castle, fortifying the soul from enemy attack (death and the devil symbolised by the skeleton and lion). At the same time, the senses dwell within the fortress because they also need to be safeguarded from external threats. The senses operate in conjunction with the entendimiento for divine contemplation.6 As such, the soul is able to achieve beatitude by conforming itself with the life of Christ and the virtues (fruits of the vine) he embodies through his crucifixion (symbolised by the tree that transforms into a crucifix). The vine growing from the tree may symbolise the Eucharistic wine, which helps to sanctify the soul through the sacramental presence of Christ. Thus, the senses serve as the entrance to the soul (and hence the entendimiento), but they must also be protected with the soul for beatitude. When the soul and the senses function together and are properly protected from enemies, the soul ascends in contemplation of the divine.

Figure 1.

Brambilla and Duchet (1582), ‘Cristo crucificado en un tronco de vid’ [‘Christ Crucified on the Trunk of a Vine’], Rome.7

3. The Form of the Auto

In order to understand the relationship between the sentidos and the entendimiento in this auto, we shall begin by examining the form of the auto, which makes an abstract or transcendent concept tangible. Calderón distinguishes between the alegórico [allegorical] and the histórico [historical] through Secta in this auto:

- Tanto…–permitid que aquí

- del alegórico estilo

- al histórico me pase,

- pues de entrambos necesito,

- uno para sus noticias,

- y otro para mis designios

(ll. 213—218)8

The ‘histórico’ gives the ‘noticia’, or the literal signal for the spectator—reader to understand, borrowed from the history of the Moors’ invasion of Madrid.9 As mundane expressions of abstract concepts, moral and theological notions such as culpa [guilt] or entendimiento are personified. Whereas such notions are otherwise inaccessible to the senses, the histórico makes them tangible, giving them anthropomorphic qualities like malice or wisdom. Both the literal and the allegorical are necessary because when these literal elements are combined, the histórico results in allegory.10 The alegórico also gives meaning to the histórico, endowing it with a deeper sense than it would otherwise have at face value. Secta claims to use these devices for her own ‘designios’ in this auto. As Secta continues:

- […] con que a un tiempo

- uniendo los dos sentidos

- de historia y de alegoría,

- haré de entrambos un mixto,

- pues tocarán a la historia

- los asaltos y peligros

- y a la alegoría la falta

- de aquel misterioso trigo.

(ll. 258–264)

Together, both the historia and the alegoría create a meaning that can be seen on a ‘mixed’ level. In this auto, the former sets the plot, which is drawn from history—of the battle between the Christians and Moors in Madrid—and the latter converts it into a Eucharistic story (‘aquel misterioso trigo’). Secta believes that through these tangible elements, the spectator—reader will understand the deeper message of the auto. With evidently limited knowledge, she believes the ‘falta’ [inadequacy] of the Eucharist is its underlying meaning.11 As such, the literal elements are necessary for revealing the allegory of the auto.

Because of the auto’s literal–transcendent or literal–abstract dynamic, which is expressed through allegory, it becomes formally congruent with the substance–accidents dimension of the Eucharist. Personified Lady Allegory in the loa to El sacro pernaso describes herself in terms of ‘substance’ and ‘accidents’, utilising the same Aristotelian language used to describe Eucharistic transubstantiation:12

- ALEGORÍA: […] soy

- —si en términos me defino—

- docta alegoría, tropo

- retórico, que excesivo

- debajo de una alusión

- de otra cosa significo

- las propiedades en lejos,

- los accidentes en visos;

- pues, dando cuerpo al concepto,

- aun lo no visible animo

- en dos sentidos, careando

- cuanta erudición ha visto

- en el Areópago el griego

- o en la Minerva el latino.

(Cortijo Ocaña 2007, p. 263)

Alegoría explains that the form of the auto and the sacrament of the Eucharist lie in parallel with each other.13 The literal meaning of allegory and the accidental nature of the Eucharist have the common end of promoting the auto’s asunto [meaning; substance] of Christ’s divinity in the Eucharist. Through personified characters and rhetoric, the literal sense gives ‘cuerpo’ to or embodies an invisible concept and serves as an intellectual teacher. Concomitantly, the allegory or the sacral dimension of transubstantiation elicits a devotional response from spectator because of the Eucharist’s divinity. Furthermore, Barbara Kurtz posits that allegory itself acts as a visible sign of an invisible reality, much like Augustine’s definition of sacrament:14

If allegory is not deictic, if it does not simply point to a privileged reality outside itself, it becomes on the contrary coextensive with that reality. It becomes, in other words, in the case of the auto’s allegory, transcendent. And not merely transcendent, but sacramental. Allegory is numinous and sacral and the auto is sacramental, Calderón seems to suggest, because it and the Eucharist it celebrates are homologous.(Kurtz 1990, p. 239)

Kurtz suggests that the theology of transubstantiation is inherently allegorical: both transubstantiation and allegory combine the earthly and divine, literal and transcendent. The Eucharist and the allegorical form of the auto correspond because in both cases the substance is Christ. Likewise, they veil this substance through the accidental form of the bread and wine and through the rhetoric and literal elements of the auto. The allegorical form of the Eucharistic auto is perfectly fitting for the theology of transubstantiation. Hence, the Eucharistic auto is sacramental.

As such, the form of the Eucharistic auto provides a deeper spiritual meaning by means of the senses. The auto’s accidental nature, like the literal nature of allegory, is necessary for the spectator’s comprehension of Eucharistic doctrine. This approach to the senses follows Aquinas: ‘Now it is natural to man to attain to intellectual truths through sensible objects, because all our knowledge originates from sense. Hence in Holy Writ, spiritual truths are fittingly taught under the likeness of material things’ (1.1.9). The senses act as vehicles for understanding of intellectual or sacral truth, by informing the entendimiento. Allegory reveals an invisible reality by means of physical reality. With its union of these two realms in the auto, the historial relies on the senses to form allegory.15 Like the accidents of the Eucharist, the auto functions as the literal veil that presents Christ to the spectator—reader through the senses.

4. The Function of the Senses and the Entendimiento for Calderón

Calderón demonstrates the necessity of the sentidos for protecting faith in the auto through their unique roles as the guardians of the muralla. When Iglesia discovers that her attackers are coming to siege the muralla, she recruits the sentidos. Calling them, ‘valientes soldados’, she acknowledges the active role they will play for the faith. She also recognises that the sentidos and Entendimiento must work together for defence of the muralla, since, as will be shown later, the two are mutually dependent for faith: ‘hoy es día/de que leales y finos/me asista el entendimiento/con todos cinco sentidos’ (ll. 497–500). Notably, the sentidos appear on stage with Entendimiento, demonstrating their union as allies. Together they exhibit their position according to the stage directions as protectors of the faith by appearing in front of Iglesia. In order to properly assist Iglesia, she assigns each sentido a role that is connected to a virtue:

- El Oído ya se ve

- que siendo en mi hermosa esfera

- la centinela primera

- tendrá a su cargo la fe.

- La Vista, que siempre fue

- la que más lejos se avanza

- y lo más distante alcanza,

- a la esperanza tendrá

- a cargo, que siempre está

- a mi vista mi esperanza.

- El Olfato, que en inmenso

- aroma es quemada nube,

- la caridad, que es quien sube,

- si en la oración en Dios pienso,

- como el humo del incienso.

- La penitencia se inclina

- al Tacto en la disciplina

- y al Gusto ayunos, que son

- una fortificación

- que se labra de otra ruina

(ll. 503–522)

The sentidos are given the active responsibility of protecting against heresy and of promoting faith. Oído [Hearing] is the leader of the sentidos, named the ‘centinela’ [sentinel] and the one most closely aligned with the virtue of faith.16 Because Vista [Sight] can see a great distance, she is anchored to the virtue of ‘esperanza’ [hope], as in Romans 8.24: ‘But hope that is seen, is not hope. For what a man seeth, why doth he hope for?’ (Challoner 1899).17 The use of antithesis between ‘lejos’ [far] and ‘avanza’ [approaches], and ‘distante’ [distant] and ‘alcanza’ [reaches] demonstrates Vista’s ability to enter the realm of the unseen or eternal. Olfato [Smell] is related to ‘caridad’ [charity] through the metaphor of incense that rises to God like prayer. The last two sentidos, Tacto [Touch] and Gusto [Taste], are called to restraint through ‘disciplina’ [discipline] and ‘ayuno’ [fasting]. These tools of penance are characterised as a ‘fortificación’ [fortification], strengthening the sentidos despite their lack. The ascetic discipline combined with the active roles of these last two sentidos reveal both their importance and limitation. They are able to enter the spiritual realm, but they must also show restraint because they are naturally limited. In this way, Calderón creates parallels between the tangible sensory realm and the theological virtues and spiritual disciplines, illustrating the sentidos’ ability to enter the eternal sphere.

The sentidos receive the Eucharist after Iglesia’s first victory against Secta, validating their spiritual dimension. Iglesia describes:

- será bien que mi cuidado

- asista a todo, y así,

- haz, sentido de la fe,

- que a los soldados se dé

- ración de pan, que si aquí

- trato de satisfacellos

- y el pan de los cielos fue,

- con los cielos cumpliré

- al mismo tiempo y con ellos

(ll. 760—764)

Because of Apostasía’s distance from the faith, she does not have proper use of her senses, apparent from her lack of vision. Iglesia is the first to expose Apostasía’s blindness when she pretends to be a soldier for Iglesia: ‘¿Y quién eres/tú, que tan ciego has venido/que yo te he desconocido/en mi ejército?’ (ll. 633—636). Iglesia does not recognise Apostasía as one of her own. She admits ‘conózcote, pero mal’, symbolising that Apostasía has distanced herself from the Church (symbolic of Protestant heresy). In fact, her blindness reflects her inability to utilise her senses, which are necessary tools to be part of Iglesia’s army. Apostasía admits of herself that ‘está el contrario fuerte/en su ciega obstinación’ (ll. 649–650). Since Apostasía defines her ‘obstinación’ [obstinacy] with the adjective ‘ciega’ [blind], her blindness is representative of her contradictory position against Iglesia. In fact, Iglesia tells Oído to be careful with Apostasía because she is ‘sospechos[a] en la fe’ (l. 672). Calderón thus creates a correlation between the use of the senses, especially sight, and nearness to the faith.

Indeed, Apostasía’s lack of vision and faith relate to her inability to see the Eucharist’s divinity. She confesses:

- ¡Válgame el cielo! ¿Qué nieblas,

- cuando a ganar voy despojos,

- poniéndoseme en los ojos

- me ciegan con sus tinieblas?

- ¿Qué es aquesto? ¿Cuando veo

- ir a pelear, mi valor

- se vuelve atrás? ¿Qué temor

- es el mío? Mas ya veo

- que este pan que me sustenta

- como sin substancia ha sido

- para mí desvanecido

- me trae […]

- ¿Qué extraños misterios son,

- oh Iglesia, que mi opinión

- han dejado destruida

- los de este tu pan? Pues ellos,

- llegando a considerallos,

- me ocasionan a dudallos,

- y aun no sé si a no creellos

- ¡[…]

- oh confusa ilusión mía,

- esta ciega fantasía!

(ll. 685–696, 702–708, 718–719)

The rhyme of ‘ojos’ [eyes] and ‘despojos’ [loot] emphasises the contrast between the two. Apostasía is unable to use her eyes to see the despojos (the Eucharist) hidden in the muralla, which Calderón highlights as essential for perceiving the Eucharist. Similarly, the rhyme of ‘nieblas’ [fog] and ‘tinieblas’ [shadows] reiterates the fruitlessness of her attempt to see the Eucharist. Apostasía recognises that the heart of the matter lies in her unbelief in the substance of the pan [bread]. With Aristotelian language, she states the error of her ways: she has partaken of the bread without believing in the divine nature of its substance. This action results in her own detriment—‘mi desvanecido’ [my disgrace]—a result of her blindness and the cause of her fear and incapacity to fight in battle. She admits that her doubt has been challenged by the ‘bread’: ‘¿[…] que mi opinion/han dejado destruida/los de este tu pan?’ (ll. 703–705). The diction relating blindness and dreams is salient: ‘confusa ilusión’ [confusing illusion] and ‘ciega fantasía’ [blind fantasy]. The Diccionario de Autoridades defines ‘ilusión’ as ‘engaño o falsa imaginación’ (Real Academia Española 1726–1739, s.v. ‘ilusión’). Likewise, Sebastián de Covarrubias considers ‘fantasma’ to mean ‘falsa imagen’ (Covarrubias Orozco 2006, p. 1090). These terms relate to Aristotle’s conception of ‘phantasia’, a faculty of the intellect that produces images without the use of sensory perception (Aristotle 2020, III.iii). Thus, Apostasía confesses not only her own deception about reality because of her suspicion about this central tenet of faith, but also her disconnect from the senses, particularly sight. She confirms this doubt when Iglesia distributes the Eucharist after the first victory. Although she claims to desire belief in the Eucharist, she lacks faith of any kind, emphasised by repetition: ‘que aunque creerlo deseo/no lo creo, no lo creo’ (l. 775). Through Apostasía’s blindness, Calderón illustrates the necessity of sight for Eucharistic devotion.

Yet while the sentidos are essential for faith, Calderón also displays their limitations—apart from Oído—in identifying the Eucharist. Apostasía interrogates Vista, Gusto, Tacto, and Olfato about what they perceive when the Host is presented. She reveals their inability to recognise the Eucharist as they each respond that they perceive only ‘pan’ (ll. 818–899). These four sentidos can dictate only the external appearance of the sacrament.

In contrast to the other sentidos, Oído is characterised as the sentido that leads to faith. She stands guard for the muro and is the first sentido to which the spectator—reader is introduced when Alcuzcuz knocks on the door (ll. 355–356). Oído describes herself to Secta as the leader of the other sentidos: ‘que en aquesta puerta estoy/por cabo de todos cinco’ (ll. 401–402). Her primary mission is to serve the faith, and she claims to do so more than the others, stating: ‘La primera posta suya/que como a la fe servimos/[…] yo soy el que más la asisto’ (ll. 394–395, l. 397). Indeed, Oído proves her unity with faith when she calls the other sentidos to receive the Eucharist:

- Venid, que la comunión,

- que la provisora ha sido,

- ya os tiene pan prevenido,

- que en su transubstanciación

- es carne y sangre.

(ll. 765–769)

Entendimiento also demonstrates his capacity for vision beyond the limitations of Vista, Tacto, Gusto, and Olfato. He is associated with conocimiento [knowledge] when, later in the auto, Apostasía mourns Entendimiento’s absence. When asked three times by Idolatría, Secta, and Alí ‘¿quién eres?’, Apostasía replies, ‘No sé’ each time (ll. 1265–1277). At this point of the auto, Apostasía claims that she has lost the basic knowledge of her identity—conocimiento—because she admits, ‘estoy sin entendimiento’, which provides her with understanding (l. 1283). Entendimiento also furnishes arbitrio [judgement], the ability to choose, based on conocimiento: Apostasía clarifies that ‘A propósito no tengo/arbitrio’ because of the loss of Entendimiento (ll. 1279–1281).18 Without Entendimiento, Apostasía can neither take action nor make a decision, since arbitrio (for Covarrubias, ‘alvedrio’ or ‘libre voluntad’) comes from the entendimiento (Covarrubias Orozco 2006, p. 196).19 Thus, because of his ability to know, distinguish, and take action, Entendimiento corresponds with the virtue of prudence. Indeed, he admits, ‘¡Ay de mí!, /que aunque yo no comunico/con ninguno duda igual, /que es la parte prudencial’ (ll. 807–809). This ‘parte prudencial’ is his understanding and ability to judge by the arbitrio. He aligns with Aquinas’ definition of prudence as ‘right reason applied to action’ (Aquinas 1981, 2.47.2). Aquinas calls this virtue that which allows one to ‘[see] as it were from afar, for his sight is keen, and he foresees the event of uncertainties’ (2.47.1). Similarly, Entendimiento possesses the clear vision of prudence. He perceives, for example, that there is more to the ‘pan’ presented by Apostasía than is immediately perceptible to the senses. In conversation with Apostasía, he states, ‘A los accidentes dan/crédito la vista y tacto, /que no a la substancia’ (ll. 846–848). Entendimiento notes that Vista and Tacto are only capable of seeing the accidental nature of the pan; they lack proper vision to perceive the substance, the ‘carne’ or divine flesh that Apostasía denies.20 Again, Apostasía challenges the idea that ‘que lo que oigo puede ser/primero que lo que huelo’, referring to faith in the Eucharist that comes through hearing (ll. 859–860). Entendimiento responds that the four sentidos lack the ability to discriminate between the substance and accident: ‘Como todos al fin van/de responder libremente/no más que en el accidente’ (ll. 861–863). Unlike the four sentidos, Entendimiento recognises that something underlies the exterior appearance of the bread.

Instead, Entendimiento relies on faith to see the Eucharist as it is, which supplies him with his prudential vision: ‘La fe que tengo me basta’ (l. 817). Prior to being captured by Apostasía, he acknowledges that he is not capable of believing in the Eucharist on his own:

- APOSTASÍA: ¿Que este pan no entra en provecho

- a quien duda y no pelea?

- Entendimiento, ¿qué hare?

- ENTENDIMIENTO: No sé, que este sacramento

- no es dado al entendimiento.

- APOSTASÍA: ¿A quién es dado?

- ENTENDIMIENTO: A la fe.

(ll. 789–795)

Entendimiento admits that the Eucharist is beyond his comprehension. It is only through faith, which he accepts, that he understands the bread to be the Eucharist. Here, Calderón illustrates a Thomistic understanding of faith as something that surpasses human reason (Aquinas, 2—2.6.1). It is revealed by God, and assented to by the entendimiento. Entendimiento possesses prudential sight, which allows him to see with the eyes of faith beyond the realm of the senses.

Yet, despite Entendimiento’s special capacity for seeing the substance of the Eucharist, he is blind without faith founded on rational argument. Apostasía reveals her plan to capture Entendimiento:

- APOSTASÍA: Según eso, ¿a ti también

- es la fe la que te obliga,

- no la razón?

- ENTENDIMIENTO: Qué te diga

- no se.

- APOSTASÍA: Pues conmigo ven

- y al tomarle un argumento

- con él mi ingenio te hará.

- ENTENDIMIENTO: Quien con ese intento va

- no van con entendimiento,

- y así vete tú sin mí.

(ll. 794–803)

Aware of Entendimiento’s rational capacity, Apostasía seeks to lure him entirely with her ingenio [from the Latin ingenium], which is oriented towards doubt.21 However, her ingenio is incapable of understanding this doctrine on its own without the light of faith.22 Entendimiento rejects this attempt, but his original faith is weak because it is not bolstered by reason. Prior to hearing Oído’s argument, he admits:

- No dejo acá de tener

- escrúpulos de que muero

- afligido cuando quiero

- este misterio entender,

- mas es en vano y en vano

- la razón discursos gasta.

(ll. 811–816)

Entendimiento confesses the incomprehensibility of the Eucharist through his reason. He reveals his insecurity when he admits he faces ‘escrúpulos’ [doubts] with his attempts to penetrate it through rational argument. Apostasía capitalises on this uncertainty, first making her attack through interrogation of four of the sentidos, apart from Oído. These four sentidos are informed by Apostasía’s framework of doubt, which directs them to perceive only the empirical matter of the Eucharist, its accident of ‘pan’. Entendimiento then heeds these sentidos, and relinquishes as he declares, ‘Ciego estoy’ (l. 878).23 Devoid of faith and a rational framework for believing in the Eucharist’s divinity, Entendimiento loses his ability to see.

In turn, Iglesia sends Oído to save Entendimiento from Apostasía through logical reasoning (ll. 935–938). Entendimiento tells Oído that he will defend himself from the sentidos’ attempts to win him back, because he has already been taken by Apostasía: ‘Ya una vez restado yo, /verás como me defiendo’ (ll. 1037–1038). Yet, Oído tells Entendimiento: ‘Tú veras cómo te rindo’ (l. 1039). Oído strives to recover Entendimiento’s proper orientation by guiding him away from error, conquering him with an argument: ‘Vencerte intento, /[…] piérdase un error y no se pierda un entendimiento’ (l. 1153, l. 1156). At last, Entendimiento admits his central qualm: how is it possible for the Eucharist to be divine flesh yet appear as bread at the same time (‘me hacen/fuerza las dudas que tengo/de ser carne el pan’) (ll. 1156–1158)? Oído’s response is based on the premise of God’s omnipotence: ‘pues dirás en este estrecho/que o no es todopoderoso, /ingrato, o que pudo hacerlo’ (ll. 1168–1170). Oído directs Entendimiento to admit God’s total power and says that either he must give up this belief, or have faith in his ability to make the Eucharist his divine flesh. To this, Entendimiento retorts, ‘no niego/el poder, el modo dudo’ (l. 1173). It is the method of God making one thing from another that seems implausible to Entendimiento.

The next step of Oído’s argument prompts Entendimiento to admit that it is more difficult to make something from nothing, rather than one thing from another, based on an argument by St Ambrose (ll. 1174–1184). Entendimiento’s response is that it seems logically inconceivable for one ‘cuerpo’ to be in place of another ‘sin ocupar lugar’ (ll. 1218–1222). Oído then distinguishes that Christ is not present in the Sacrament in a quantifiable, material way, but rather in substance:

- El cuerpo extenso, concede;

- el cuerpo que está con modo

- indivisible, eso niego;

- y así está el cuerpo de Cristo

- en el pan del sacramento

- por el modo indivisible.

(ll. 1226–1231)

Oído’s logical syllogism has concluded that Christ is present in a way that is ‘indivisible’, in a manner that is unlike normal material matter. With this point, Entendimiento admits, ‘confieso que estoy vencido/y que sin armas me veo’ (ll. 1245–1246). Calderón illustrates the Thomistic understanding that faith that is founded on natural reason (Aquinas 1981, 2—2.4.2). Nevertheless, for Aquinas faith also perceives that which is above the natural reason (2—2.2.3). In like manner, Oído has proven that Entendimiento can rely on reason that also does not disregard faith. Gradually, Entendimiento recovers himself because he follows a rational framework until he transcends logic for faith.24

The sentidos play the important role of invoking hearing to restore the optics of faith. Unlike Apostasía’s endeavour to make Entendimiento suspicious of the Eucharist through empiricism, Oído strengthens Entendimiento against doubt by building a syllogism through reason, which allows him to restore his proper vision: Entendimiento recovers from his blindness and works alongside the sentidos when anchored in reason. Similarly, although Vista, Gusto, Olfato, and Tacto can be limited to the empirical sphere, they are also aids in faith for Iglesia and Oído through music, which solicits the sense of sight. Olfato describes the reinforcement of the muralla that the sentidos will provide Iglesia:

- Todos para repararle

- trabajaremos, porque

- diga la fama que fue

- ofrecer cada sentido

- la virtud que le ha cabido

- fortificarse en la fe.

(ll. 949–954)

In response to Iglesia’s entreaties for their help after Apostasía’s invasion of the Church, Olfato promises that the sentidos will aid Iglesia with protecting the broken muralla. As agents of the faith, each sentido offers assistance in the battle through their corresponding virtue.25 Iglesia charges the sentidos with singing a ‘pía cancíon’ (l. 956) to help Oído in warfare against Apostasía: ‘y así en fe suya salid/a dar calor al Oído, /vuestro principal sentido’ (ll. 1015–1017). The support they provide is through music, as Olfato and the rest of the sentidos pray for Mary’s aid in battle:

- OLFATO: […] y para que se vea

- que a María mi fe pía

- pide que se acerque el día

- que nos dé su imagen bella,

- donde esté he de hablar con ella

- diciendo: Ave María.

(ll. 959–964)

Olfato describes her hope that this song will summon a Marian image which will support them in combat. She correlates the faculty of seeing (‘vea’) with exercising faith (‘a María mi fe pía/pide’) and with the sense of hearing through speech (‘hablar con ella’). As she sings the Ave María, music plays on the stage and an echo repeats her song from inside of the cubo in the muralla (ll. 964–1010). Finally, an image of Mary is revealed according to the stage directions: ‘Chirimías y acaba de caer el muro, y vese como entre ruinas la imagen’. After the muro crumbles, the sentidos’ song triggers this image and invokes the faculty of sight. Iglesia harnesses optics to draw attention to the spectacle, as she declares, ‘Llegad, que la vista mía/entre la ruina, ¡ay de mí!’ (ll. 1549–1550). Although the sense of hearing is important for beckoning the appearance of the image, sight is the primary sense for devotion since the image is presented at the auto’s culmination. As she beholds this image, it is through vision that Iglesia realises the defeat of the muro’s assailants. The sentidos support the faith by effecting hearing (rational discourse, singing, and speaking) to beckon the use of vision (the image) to signify Iglesia’s victory.

As the spectator—reader witnesses the sentidos’ auditory and visual offensive to defend Iglesia and the Entendimiento, they learn to exercise their own hearing and sight for devotion. The sentidos assume a didactic function near the beginning of the auto as they enumerate with Entendimiento the ‘catorce soldados’ (l. 541) or ‘catorce baluartes’ (l. 611)—the doctrines of the creed—which support Iglesia against attack.26 As Iglesia is auditorily being instructed for defence of her faith, the spectator—reader’s faith is at once reinforced as they hear these doctrines of faith. Moreover, Oído’s subsequent defence of the Eucharist guides the spectator—reader in a rational argument that promotes devotion. Yet, these auditory tools ultimately support and prepare for the use of the visual faculty. Together, the sentidos describe the beauty of the image of Mary, until their song culminates in the image of the Almudena, which guards the muralla from heresy entering. The spectator—reader’s own faith is enriched through hearing so that they may know how to direct their gaze towards a sacred image. As they look upon the devotional image, they can properly make an act of devotion with their understanding of the faith that they have received through hearing. The sentidos’ doctrinal discourse and song teach the audience to develop the faculty of optics for the vision of faith.

However, with the sentidos’ inevitable physical limitations, the newly converted Entendimiento sustains Iglesia. The sentidos are ‘de hambre muriendo’ as the muro is being sieged by the assailants. Once the muro has fallen, Iglesia asks the sentidos what has happened, and they prove unable to answer:

- IGLESIA: Vista,

- Gusto, Olfato, Oído, ¿qué es esto?

- VISTA: Yo no sé, que con el hambre,

- señora, me desvanezco.

- GUSTO: Yo tampoco, porque el gusto

- fallece sin el sustento.

- TACTO: Entumecido me traes,

- solo sé que me entorpezco.

- OÍDO: A mí espíritus me faltan.

- OLFATO: A mí me faltan aliento.

(ll. 1505–1514)

Calderón highlights the physical frailty of the sentidos, including Oído, who are deprived of their ability to perceive. They are weak and incapable of fulfilling their duties as guardians of the muralla. Iglesia notices the faultiness of the sentidos, exclaiming, ‘En fin, humanos sentidos; /y por más ¡ay Dios! que quiero/aplicarlos, mis virtudes/desmayan […]’. Without food, the sentidos lack strength to be of use for guarding the muralla, other than their ability to pray for the Virgin to provide bread: ‘Pan, señora, trigo, trigo’ (l. 1609). Given their weakness, it is Entendimiento who recognises and announces the Eucharistic bread provided by the Virgin: ‘No esta vez te cause pena, /que ya vino el trigo que en esta almudena/tesoro ha de ser de Santa María’ (ll. 1612–1615). Entendimiento also alludes to the revelation of celestial secrets he has received, stating, ‘como a pequeñuelos, Dios/les revela sus secretos–’ (ll. 1623–1624). He proves that he once more is guided by faith since he can see heavenly mysteries. Immediately, Eucharistic bread appears according to the stage directions, as Entendimiento has rightly perceived. Calderón illustrates that Entendimiento can compensate for the sentidos’ inability to perceive.

Before Oído challenges Entendimiento, she reminds the audience to use the vision of faith to uncover the allegorical meaning of the auto. Oído states:

- En la sangrienta campana

- que es a dos luces a un tiempo

- de fieles y infieles, que es

- sentidos y entendimiento,

- cuerpo a cuerpo, no sin grande

- providencia de los cielos

- hemos quedado los dos,

- y así es fuerza cuerpo a cuerpo

- que hagamos los dos batalla.

(ll. 1139–1147)

Oído summons the audience to use its interior spiritual vision with this reminder of the allegorical nature of the auto. Just as the faithful and unfaithful war with one another, so do the sentidos battle with Entendimiento, and Iglesia with its assailants to preserve the faith. This battle has a transcendent meaning, but it can only be accessed through literal tools. The spectator—reader must use both their own senses and entendimiento in order to fully see the veiled allegorical message of the auto.

Hence, with Iglesia’s example, the spectator—reader learns to employ their own spiritual vision. Once the trigo is revealed, Iglesia calls the sentidos to feast, satisfying both their corporeal and spiritual natures with this spiritual bread: ‘Llegad, humanos sentidos, /al trigo a satisfaceros/mientras yo subo a adorar’ (ll. 1659–1661). As the sentidos partake of the Eucharistic Host, Iglesia is able to ascend in adoration since Entendimiento has renewed faith. As Iglesia’s assailants scale the muralla and think that they are about to achieve victory, they hear a bell ring (l. 1702). Although the assailants mistake it for a sign of peace, the bell in fact announces the Marian image revealed by the stage curtain, followed by the Eucharist presented from behind the muralla. The sound summons the spectator—reader to prioritise their sight to venerate both Sacrament and image. Iglesia both confirms her victory and calls the spectators and actors to adore the Eucharist with the use of sight, stating, ‘dadle con él en los ojos’ (l. 1736). As in Figure 1, the senses inform the spectator and form the foundation for vision of divine mysteries. Now trained to use the eyes of faith, they adore the Eucharist in conjunction with the senses and entendimiento.

Indeed, these images on the stage were aimed at fostering an affective response in the spectator. In this Counter—Reformation context, the image was considered a powerful means of soliciting devotion by harnessing Aristotelian verisimilitude (Checa Cremades and Morán Turina 1982, p. 211). Authors and artists of the period reclaimed images as ‘representación de las cosas invisibles’, as Checa Cremades and Morán Turina explain, orienting the viewer’s gaze towards heavenly mysteries through physical depictions (p. 212). In the Baroque imagination, the image was thought to excite the afectos [Latin: affectus; sympathy] that move the devotee towards faith (p. 215).27 Antonio Maravall considers Baroque theatre to harness the use of asombro [wonder] for an affective response: this theatrical tool is ‘una retención de las fuerzas de la contemplación o admiración durante uno instantes, para dejarlas actuar con más vigor al desatarlas después’ (Maravall 1996, p. 438). The appearance of an image—especially with the use of apariencias in the theatrical context—can spark asombro and harness the afectos of the viewer.

As such, Calderón’s theatre arrested the viewers’ sight in a grand visual display, promoting wonder through the afectos (Suárez 2002, p. 106). According to Juan Luis Suárez, Calderón facilitates human’s relationship with the material world and spiritual reality by means of the senses and the imagination (Suárez, p. 94). The theatrical spectacle orders the afectos to move the will to assent to faith in spiritual realities that the entendimiento perceives to be true.28 The appearance of the image of the Almudena—a polychrome statue—and the subsequent arrival of the Eucharist to herald Iglesia’s victory on the massive auto stage would have solicited the spectator’s sight at the denouement of the play (Ruano de la Haza 2000, p. 29). After hearing the rhetorical argument for the divinity of the Eucharist, this scenography would capitalise on the entendimiento and asombro through the senses, moving the spectators to an act of devotion by means of sight.

Even more, as the spectators use their allegorical vision, they realise the double meaning of the auto and the Eucharist, which requires the vision of faith to enter its deeper spiritual meaning. Consequently, the auto ends with the sentidos, Entendimiento, and Iglesia announcing together the victory of the Eucharist and Mary, and modelling an act of devotion for the worshiper. Música speaks directly to the faithful: ‘Este, católicos, es, /para aliviar nuestra pena, /el trigo de la almudena’ (ll. 1791–1793). The end of the auto is an invocation to devotion for the spectators. Calderón teaches the spectators to use their sentidos to guide their entendimientos, and in turn their entendimientos to direct their spiritual and allegorical sight, to grow in devotion to Mary and the Eucharist through the medium of the auto.

5. Conclusions

This article builds on the recently growing body of scholarship on vision within Golden Age studies.29 Given the emphasis on the mechanics of optics in this period, I offer an alternative understanding of this sense for sensory studies through an examination of the vision of faith. I have sought to reconcile both scholarship that denies the reliability of the senses for ascertaining truth and scholarship that does not properly account for the optics of the entendimiento in Calderón. Due to Calderón’s allegorical framework, Calderón stimulates trust in the material world through the senses while at the same time accounting for another means of perception, the prudential vision of the entendimiento that can perceive beyond the sensual realm. Although they are limited, the sentidos serve as vehicles for and defenders of the faith and guides of the soul towards truth. Oído is specifically named by Iglesia as the leader of the sentidos, imparting faith to both Entendimiento and the spectators through rational argument, doctrinal instruction in the creed, and a song that beckons the appearance of the Marian image to allow them to see clearly.

This article also contributes to Calderonian scholarship by highlighting the paradox Calderón creates within the debate between sight and hearing. Since Calderón uses the artistic medium of the auto, which is as much visual as it is auditory, Iglesia reveals a contradiction when she claims that Oído is the ‘principal sentido’. Indeed, the attainment of vision is the primary plot of the auto. Apostasía is characterised as blind without faith, seeking to capture Entendimiento for subversive purposes, and the restoration of Entendimiento’s sight proves to be one of the auto’s central problems. Calderón follows the Thomistic framework of the entendimiento, illustrating Entendimiento’s ability to assent to faith founded on logical reasoning that comes from Oído. The sense of hearing evidently serves to enact vision.

As the public witnesses the characters grow in their vision of faith through the play, the auto shapes their own entendimientos. The faculty of sight promotes piety with the live devotional elements at the denouement of the play. The spectators are invited to make an act of devotion themselves, as the bell calls them to attention, only to summon the presentation of the image of Mary and the Eucharist. The Marian image that appears at the end of the auto symbolises the Church’s victory and commands Iglesia’s attention for divine contemplation. The spectators are also offered the opportunity to follow in Iglesia’s suit by adoring the Eucharist and the Marian image through asombro and the afectos stimulated by sight. Using both the sentidos and the entendimiento, the spectators uncover the hidden meaning of the auto by enacting the eyes of faith as they use the literal to envision the spiritual realm.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See Cornelius Cornelii a Lapide, who calls Mary the ‘domus panis’ [house of bread] (Lapide 1638, p. 69). For other instances of Marian figures connected with provision of grain in the autos, see, for example: ¿Quién hallará mujer fuerte?; La primer flor del Carmelo; Las espigas de Ruth. |

| 2 | See Luis Galván’s introduction to the critical edition of this auto for a detailed account of the legend and analysis of the artistic liberties Calderón takes in the auto (Calderón de la Barca 2004, pp. 8–15). |

| 3 | On the representation of Islam in Calderón’s autos, see de Miguel Ángel Bunes Ibarra (1991). |

| 4 | On the allegorical meaning of this auto as both the ‘guerra del alma’ and the attack of the Church, see (Valbuena Prat 1924; Calderón de la Barca 1952, p. 559). |

| 5 | Jeremy Robbins espouses that Baroque society was disquieted by epistemological uncertainty, focused on the distinctions between ser and parecer and engaño and desengaño (Robbins 2005, p. 11). An important caveat, as Robbins clarifies, is that it deemed the exterior senses incapable of providing an objective epistemic account of reality, rather than a negation of the physical world. For more on the epistemic pessimism of the Baroque period and its relationship to scepticism. |

| 6 | See Aquinas 1.79.1. |

| 7 | Imagen procedente de los fondos de la Biblioteca Nacional de España [This image originates from the collections of the National Library of Spain]. |

| 8 | It is common for the devil character in the auto to establish the allegory. See, for example, Culpa in Las órdenes militares:

(Calderón de la Barca 2005, ll. 231–235) |

| 9 | I prefer to use the term ‘spectator—reader’ to allow for the diverse ways in which one can interact with this play, either by reading it as drama or watching it performed as theatre. For more on the meaning of historial in Calderón’s autos, see Antonio Regalado; Ignacio Arellano (Regalado 1995; Arellano 2000, 2001). |

| 10 | As Ignacio Arellano expresses, ‘Allegory is, in short, the main means of unifying the two levels of the play (that of human words and that of the divine meaning). What is invisible becomes visible on stage through its allegorical personification, and the step from one level to another occurs as the analogy is understood’ (Arellano 2015, p. 19). |

| 11 | For more on the devil characters’ limited knowledge and role in setting the allegory in Calderón’s autos, see Ángel Cilveti (1977). |

| 12 | Barbara Kurtz mentions this distinction on p. 233 (Kurtz 1990). |

| 13 | Since the sacrament of the Eucharist is believed to be in substance the real presence of Christ, it points to a transcendent realm, offering a tangible means of efficacious grace to the devout. Just as the historial functions to employ the transcendence of allegory, so do the ordinary elements of bread and wine, enjoyed by the senses, function as an entrance into the sacral realm of grace. |

| 14 | Note that this forms the basis for the Catholic Church’s understanding of the sacraments. See Augustine in City of God: ‘The visible sacrament [is the] sacred sign of an invisible sacrifice’ (Augustine 1963, 10.5). Aquinas adopts this same understanding that ‘a sacrament is a kind of sign’ (Aquinas 1981, 3.60.1). |

| 15 | This idea is also expressed by Dante:

Here, allegory is described as a deep well of meaning that can only be reached by means of the literal. |

| 16 | On the tension between sight and hearing as the faculty most closely aligned with faith in Calderón, see Lobato. |

| 17 | See also Galván’s footnote to this verse on p. 124 of El cubo de la Almudena (Calderón de la Barca 2004). |

| 18 | Calderón defines Entendimiento’s role in El pleito matrimonial (Calderón de la Barca 2011):

(ll. 425–428) Entendimiento identifies himself as one of the three powers of the soul—in line with Augustinian tradition—appearing after Memoria and Voluntad. Entendimiento is primarily oriented towards conocimiento, with which he is able to ‘eligir’, as he explains to Apostasía in La divina Filotea (Calderón de la Barca 2006): ‘Y si hago más memoria/nos apartaron los genios, /tú a inventar y yo a elegir’ (ll. 832–834). See Eugenio Frutos, pp. 153–65 for the different portrayals of Entendimiento personified in the autos of Calderón, a characterisation that Frutos claims is unchanging across the autos (Frutos 1952, p. 153). |

| 19 | Frutos: ‘Así como el querer es función de la Voluntad, el entender lo es del Entendimiento. Pero Albedrío, en Calderón, no puede equipararse, como veremos, a querer racional, a volición, pues en ocasiones significa el apetito sensible, y el Ingenio no es la simple intelección pura, sino la facultad de inventar (de intuir, acaso, pudiéramos decir hoy), mientras el Entendimiento es la facultad de elegir o discernir (esto es, de juzgar)’ (Frutos 1952, p. 153). |

| 20 | See El árbol de mejor fruto, where Salomón says: ‘Ya tengo/dicho, que lo que el sentido/no ve, ve el entendimiento’ (Calderón de la Barca 2009, ll. 1497–1499). |

| 21 | See A Dios por razón de estado, where Ingenio says:

(Calderón de la Barca 2014, ll. 194–200) |

| 22 | See A Dios por razón de estado when Gentilidad says: ‘que en materias de fee, /solo toca callar al ingenio’ (Calderón de la Barca 2014, ll. 393–94). For the treatment of the Ingenio and its accompanying Pensamiento in Calderón’s autos, see pp. 546–86 of Sansuán Sáez (Sansuán Sáez 2004). |

| 23 | See Fray Luis de Granada: ‘Mas, cuando siguen otro norte, que es cuando –dejada la razón–, se mueven por la imaginación y aprensión de las cosas sensuales –que es una guía muy ciega–, entonces van descaminadas, por seguir este adalid tan ciego’ (De Granada 2021, p. 246). |

| 24 | See also Galván’s treatment of this logical argument and its relationship to Aquinas and Church teaching on pp. 19–22 in the introduction to the critical edition of this auto (Calderón de la Barca 2004). Note that Calderón defines the rational part of Entendimiento through Pensamiento in La cena del rey Baltasar:

(Calderón de la Barca 2013, ll. 17–19) |

| 25 | Later, Vista battles with Idolatría, Tacto with Secta, Gusto with Alí, Olfato with Apostasía, and Oído with Entendimiento. See ll. 1081–1250 (Calderón de la Barca 2004). |

| 26 | See ll. 539–615 (Calderón de la Barca 2004). |

| 27 | For more on the use of the marvellous for affectivity in Calderón’s spectator, see Suárez, ‘La comunicación de los afectos’ (Suárez 2002, pp. 93–124). On the meaning of the term ‘afecto’ for Calderón, see Alan Soons (Soons 1992). |

| 28 | See Roberto Di Ceglie on faith, the intellect, and affectivity in Aquinas: ‘Faith is, therefore, not reducible to assent of the intellect. Although Aquinas insists that faith is formally an act of intellect, he also “does recognize the large part which the will plays in the act of faith.” Consequently, for him “the act of faith is an act intrinsically determined by affective elements”’ (Di Ceglie 2016, p. 139). |

| 29 | For further reading, see, for example (Battistini 2006; Bergmann 2003; García Santo-Tomás 2015; González-Cano 2004; Blanchard 2005). |

References

- Alighieri, Dante. 1990. Il Convivio. Translated by Richard H. Lansing. New York and Garland: Princeton Dante Project. Available online: https://dante.princeton.edu/pdp/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Amadei-Pulice, Maria Alicia. 1990. Calderon y el Barroco: Exaltación y engaño de los sentidos. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1981. Summa Theologiae. The Collected Works of St. Thomas Aquinas. InteLex Past Masters. Translated by English Dominicans. New York: Christian Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, Ignacio. 2000. Algunos aspectos del marco historial en los autos sacramentales de Calderón. In Velázquez y Calderón. Dos genios de Europa. Edited by José Alcalá Zamora y Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, pp. 221–48. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, Ignacio. 2001. Estructuras dramáticas y alegóricas en los autos de Calderón. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger and Universidad de Navarra, pp. 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, Ignacio. 2015. The Golden Age Sacramental Play: An Introduction to the Genre. In Dando luces a las sombras: estudios sobre los autos sacramentales de Calderón. Madrid and Frankfurt: Iberoamericana—Vervuert, pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 2020. De Anima. Edited and translated by Christopher John Shields. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, Saint. 1963. Bishop of Hippo. ‘Book X. Chapter 5: Of the Sacrifices Which God does not Require, but Wished to be Observed for the Exhibition of Those Things which He does Require’. In City of God Against the Pagans. Translated by George E. McCracken. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battistini, Andrea. 2006. The Telescope in the Baroque Imagination. In Reason and its Others: Italy, Spain, and the New World. Edited by David Castillo and Massimo Lollini. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, Emilie L. 2003. Amor, óptica y sabiduría en Sor Juana. In Nictimene … sacrílega: Estudios coloniales en homenaje a Georgina Sabat—Rivers. Edited by Mabel Moraña and Yolanda Martínez—San Miguel. Mexico City: Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana, pp. 267–81. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, Jean Vincent. 2005. L’optique du discourse au XVIIe siècle: De la rhétorique des jésuites au style de la raison moderne (Descartes, Pascal). Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, Ambrogio, and Claude Duchet. 1582. [Cristo crucificado en un tronco de vid]. Collection of the National Library of Spain. Biblioteca digital hispánica. Available online: http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000026738 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Bravo Navarro, Martin, and José Sancho Roda. 1993. La Almudena. Historia de la Iglesia de Santa María la Real y de sus imágenes. Madrid: Editora Mundial, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bunes Ibarra, Miguel Ángel. 1991. El Islam en los autos sacramentales de Pedro Calderón de la Barca. Revista de Literatura 53: 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 1952. Obras completas, Vol. III: Autos sacramentales. Edited by Ángel Valbuena Prat. Madrid: Aguilar, p. 559. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2004. El cubo de la Almudena. Edited by Luis Galván. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2005. Las órdenes militares. Edited by José M. Ruano de la Haza. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2006. La divina Filotea. Edited by Luis Galván. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2009. El árbol de mejor fruto. Edited by Ignacio Arellano. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2011. El pleito matrimonial. Edited by Mònica Roig. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2013. La cena del rey Baltasar. Edited by Antonio Sánchez—Jiménez and Adrián J. Sáez. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Calderón de la Barca, Pedro. 2014. A Dios por razón de estado. Edited by J. Enrique Duarte. Kassel and Pamplona: Edition Reichenberger—Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Challoner, Bishop Richard, ed. 1899. The Bible: Douay—Rheims Version. Baltimore: John Murphy Co. [Google Scholar]

- Checa Cremades, Fernando, and José Miguel Morán Turina. 1982. Teoría de la imagen religiosa. In El Barroco: el arte y los sistemas visuales. Madrid: Ediciones AKAL. [Google Scholar]

- Cilveti, Ángel. 1977. El demonio en el teatro de Calderón. Valencia: Albatros. [Google Scholar]

- Cortijo Ocaña, Antonio. 2007. La loa para el auto sacramental El sacro pernaso de Calderón de la Barca. Revista de filología Española 87: 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias Orozco, Sebastián. 2006. Tesoro de la lengua castellana o española. Edición integral e ilustrada. Edited by Ignacio Arellano and Rafael Zafra. Madrid and Frankfurt: Iberoamericana—Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- De Granada, Fray Luis. 2021. Introducción del símbolo de la fe. Edited by Fidel Sebastián Mediavilla. Barcelona: Real Academia Española—Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- De la Flor, Fernando. 2002. Barroco: representación e ideología en el mundo hispánico (1580–1680). Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ceglie, Roberto. 2016. Faith, reason, and charity in Thomas Aquinas’ thought. International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 79: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez Borque, José María. 1983. Teatro y fiesta en el Barroco español: el auto sacramental de Calderón y el público. Funciones del texto cantado. Madrid: Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, pp. 606–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fradejas Lebrero, José. 1959. La Virgen de la Almudena. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Madrileños, pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Frutos, Eugenio. 1952. La filosofía de Calderón en sus autos sacramentales. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, C.S.I.C. [Google Scholar]

- García Santo-Tomás, Enrique. 2015. La musa refractada: literatura y óptica en la España del Barroco. Iberoamericana and Frankfurt: Iberoamericana—Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Stephen. 1946. An Introduction to the Ideology of the Baroque in Spain. Symposium 1: 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cano, Agustín. 2004. Eye Gymnastics and a Negative Opinion on Eyeglasses in the Libro del exercicio by the Spanish Renaissance Physician Cristóbal Méndez. Atti della Fondazione Giorgio Ronchi 49: 559–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, Anthony. 1993. Aquinas on Mind. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, Barbara. 1990. Defining Allegory, or Troping through Calderón’s Autos. Hispanic Review 58: 227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapide, Cornelius Cornelii a. 1638. R.P. Corn. Cornelii a Lapide e Societate Iesu, S. Scripturae olim Louanii, Postea Romae Professoris Commentarii in IV. Euangelia, […] in duo Volumina Diuisi Tomus Primus. Complectens Expositionem Literalem et Moralem in SS. Matthaeum et Marcum. Indicibus Necessariis Instructus. Lugduni: Iacobi Prost and Petri Prost. Oxford: Collection of the Library of The Queen’s College. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato, María Luisa. 2002. El hechizo de la voz y la hermosura en el teatro de Calderón. In Calderón 2000. Homenaje a Kurt Reichenberger en su 80 Cumpleaños. (Actas del Congreso Internacional, IV centenario del nacimiento de Calderón, Universidad de Navarra, Septiembre, 2000). Kassel and Pamplona: Universidad de Navarra—Edition Reichenberger, vol. 1, pp. 601–17. [Google Scholar]

- Maravall, José Antonio. 1996. La cultura del Barroco. Análisis de una estructura histórica. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, Jerónimo. 1629. Historia de la antigüedad, nobleza y grandeza de la villa de Madrid. Collection of the Universidad Complutense Madrid. Edited by E. Varela Hervías. Madrid: La Imprenta del Reyno. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española 1726–1739. Diccionario de la lengua castellana en que se explica el verdadero sentido de las voces, su naturaleza y calidad. Madrid: Francisco del Hierro.

- Regalado, Antonio. 1995. Los orígenes de la modernidad en la España del Siglo de Oro. Barcelona: Destino, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Jeremy. 2005. The Arts of Perception. Bulletin of Spanish Studies 82: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano de la Haza, José María. 2000. Calderón, escenógrafo. Insula: Revista de letras y ciencias humanas 644–645: 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sansuán Sáez, Jesús. 2004. La filosofía ético—religiosa en los autos sacramentales de Calderón. Zaragoza: Colegio Mayor Universitario La Salle. [Google Scholar]

- Soons, Alan. 1992. La voz afecto y sus congéneres en la comedia. Lección de tres obras de Calderón sacadas de Diferentes XLII. Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 40-1: 451–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbuena Prat, Ángel. 1924. Los autos sacramentales de Calderón (Clasificación y Análisis). Revue Hispanique 61: 245. [Google Scholar]

- Shergold, Norman David, and John Earl Varey. 1961. Los Autos Sacramentales en Madrid en la Época de Calderón: 1637–1681. Estudio y Documentos. Madrid: Ediciones de Historia, Geografía y arte, S.L., p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, Juan Luis. 2002. El Scenario de la Imaginación: Calderón en su Teatro. Barañáin: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).