1. Introduction

This paper

1 investigates the narratives involved in the becoming public of an ecological, relational, and culinary culture through artistic mediums. Specifically, the question posed is this: how do food and cooking feature in some selected design and architecture exhibitions? My analysis starts by engaging with the current reputation of the arts as disengaged from everyday life, an aspect which substantially limits their transformative potential. This criticality stands as the underlying core of the paper and fuels my desire to highlight case studies that embody an ecological and intimate relationship between people and their environments.

In

Section 2,

The Schizoid Attitude to the Arts: Leveling Art to the Level of Cooking, I explore that controversy, its implications and the potential role that art and exhibition-making play in forging ecological narratives. In doing so, I briefly revisit the characteristics of some historical movements (such as New Museology, New Institutionalism and Relational Aesthetics) and some 20th-century artists (such as Joseph Beuys, Gordon Matta-Clark and Daniel Spoerri’s Eat Art Gallery).

The following sections become more descriptive, as I analyze contemporary case studies primarily between Italy and the UK, in the timespan 2015–2023, with the goal of proposing tangible projects that embody an ecological perspective.

In

Section 2.1,

Food: Bigger than the Plate Exhibition: Experimental Entanglements in Process, the focus is on the exhibition format. I introduce the multidisciplinary nature of food and its entanglements with design and architecture through the pivotal 2019 exhibition

Food: Bigger than the Plate, an exhibition that stands as the frontier between academic research and public engagement.

In

Section 2.2,

Living Furniture at Milan Design Week 2015/2016, I focus on the development of designers’ ecological thinking in relation to the wasteful culture of consumption they partake in. Through the chosen case studies, the notion of art as something unchangeable and to be contemplated from a distance is radically challenged. Instead, I consider aspects such as digestion, perishability and fragility for their aesthetic value.

This line of enquiry continues in

Section 2.3,

Care and Conviviality at Venice Architecture Biennale 2021, which focuses on architectural projects that envision spaces of kinship around a dinner table. The concept of hospitality creates a spatiality and shapes architectural components, expanding also to the non-human. Through these sections, designers and architects are considered in their “cooking” process with living materials, which results in a series of chairs and tables embodying values of community and ecological thinking.

2In

Section 3,

An Ecology of Exhibitions Through the Concept of Hospitality, I go back to a more theoretical enquiry by exploring the ambiguous concept of hospitality in the context of exhibitions. I argue that in the current crisis of public engagement with the arts, developing exhibitions through the lines of hospitality can be highly effective and amplify a relational model which calls for the collective and entangled nature of all things. Arguing for an ecology of exhibitions—as the study of the relationships that take place in and beyond the exhibition space—reinforces a certain responsibility of those that are primary actors in the development of such exhibition spaces, such as curators, artists, designers, and architects. Exhibitions are thus proposed as stages where relationships and holistic thinking perform, challenging the commonplace of art and design spaces as elitist, off-putting, and sterile. Nonetheless, I also consider the risks and paths forward for a curatorial practice that attempts to communicate the ecological paradigm.

The overall narrative of examples I follow challenges the boundaries of established definitions and categories. I use words such as “objects”, “design”, and “architecture”, but their understanding is placed within an ecological paradigm, as opposed to a consumerist social model where their meaning corresponds to their economic status symbol value. The same goes for “narratives”, which are to be understood in their etymological sense, namely the act of telling a story composed of connected events. I align with

Perullo’s (

2022) position and with

Bismarck’s (

2022) recollection of the radical architecture group Supertudio that call, although in different ways, for a life

with objects, which necessitates that we “approach and fluidify by breaking down the barrier between mind and world” (

Perullo 2022, p. 166 [my translation]).

Proposing a shift in perception comes from the realization that current modes of perceiving leave us unprepared to understand and act within the crisis in which we are participating as a species. Indeed, the topic is a lively one at present. As

Alva Noë (

2004) and Perullo argue, to perceive is to act, and to perceive is a process of transformation (

Perullo 2022, p. 76). Through this paper, I propose an encounter with art that is not an exception from our daily life—“art as the ‘Sunday of life’“ (

Perullo 2022, p. 73), art that is encountered as “aestheticization” where perception is at the service of consumerism (

Perullo 2022, p. 122). In the wake of the current debate about art and a more inclusive aesthetics, a renewed encounter with art entails an integrated way of perceiving density on a daily basis. Therefore, the examples that follow blur the lines of food, design, architecture, and curatorship, as they perform as processes of collective authorship happening in atmospheres of conviviality and hospitality.

My purpose in emphasizing these specific case studies is to provide examples of the rich (yet fairly marginalized) presence of these practices. In order to engage with the combined potential of food and art, we must acknowledge the criticalities of the systems in which they are embedded and trace a path forward for research and practice which stands on radical collaboration and response-ability. I hope this paper contributes to that end.

Before getting to the heart of the matter, a brief note on the autoethnographic element of this paper. The research reflects my own experience of living, working, and studying between the countryside and the city, between Italy and the UK, and between the arts and gastronomy. Specifically, having worked both in fine dining and in the curatorial team for the development of a design exhibition has provided me with valuable first-hand experience into the topic discussed in this paper. In terms of schooling, I trained both in curation (BA) and in gastronomic sciences (MA), which gives me the possibility to approach the topic in a hybrid way. The intersection between ecology, food, and art is at the heart of my long-term research. I very much care to create coherence and synergy between my private and professional lives, as in reality, it already is just one, unified life. In other words, the relationship between humans and their environment that underlines this paper is not just a theoretical enquiry, it is a heartfelt commitment to aesthetic engagement that I practice in my everyday life.

2. The Schizoid Attitude to the Arts: Leveling Art to the Level of Cooking

The moral function of art [...] is to remove prejudice. [...] Works of art are means by which we enter, through imagination and the emotions they evoke, into other forms of relationship and participation than our own.

Despite the numerous flirtations between food, cooking, and the so-called major arts, assiduously cultivated by Western avant-garde chefs (from Escoffier to Adrià in modern history), I would like to revisit the relationship between the arts and food from a different perspective. This attempt develops through the lines of several questions that I am going to unpack, such as which narratives about food and cooking do exhibitions foster? What is the role of exhibitions in the “becoming-public” of a certain culture, and more specifically an ecological sensitivity? Can museums and exhibitions be places of conviviality and what would the potential of conviviality in those spaces be?

The definition of art

3 as something that is strictly exhibited in the institutional space of a museum or gallery has been notoriously challenged starting from the 20th century. However, in this paper, I argue that institutional art spaces are holders of a collective identity and a powerful narrative, which can be applied in a reactionary or disruptive way in relation to the status quo. Bencard et al. argue that as a “physical space apart from everyday life, museums are well suited to containing this kind of rupture, that is, disturbances in standard concepts” (

Bencard et al. 2019, p. 136). Exhibitions started to be recognized as “primary cite of exchange” (

Greenberg et al. 1996, p. 183) already more than twenty years ago, and their cultural significance has increased even more to this day. Following the path of

New Museology outlined by Vest Hansen et al., exhibitions more than ever are “producers of narratives that actively participate in the construction of dominant ideas that shape our perception of time, space, and history, as well as influencing the identity of subjects, communities, classes, and nations” (

Vest Hansen et al. 2019, p. 1). Exhibitions become the space for critical investigation, where meaning is forged and negotiated through a culture of research.

Originally described by Peter Vergo, the field of New Museology emerged at the end of the 1980s and placed an emphasis on “museum’s awareness of their purpose rather than their methods so that they are accessible to all visitors without regard for cultural capital, upbringing, or education” (

Vest Hansen et al. 2019, p. 60). New Museology concerns museums and collections, and its strategy particularly emphasizes the use of popular exhibition topics to better engage and attract audiences to museums. This approach also entails a shift in focus from collections to visitor experience and participation.

In a neoliberal framework of museum management, these kinds of programs risk to fall into a catch-22 situation. Intended to increase accessibility, they can instead turn into the commercial (or populist) trap of the so-called “experience economy” or a way for businesses (like the commercial fashion system) to obtain visibility in non-commercial spaces (ibid., p. 61). However, in the best case scenarios, New Museology interventions introduce multivocal perspectives.

The desire to highlight relations, dialogue, and multiplicity of New Museology connects in many ways to

New Institutionalism and

Relational Aesthetics. The former was a term borrowed from the social and economic sciences which emerged in the context of Northern European 1990s art practice. Doherty defines New Institutionalism as “characterized by the rhetoric of temporary/transient encounters, states of flux and open-endedness. It embraces a dominant strand of contemporary art practice—namely that which employs dialogue and participation to produce event or process-based work rather than objects for passive consumption” (

Doherty 2004, p. 1). Its application was mainly on medium-sized public contemporary art institution: its curatorial, educational, and administrative activities were expanded and challenged towards more inclusive and adaptable forms (

Kolb and Flückiger 2013).

The passing of time revealed some practical issues confronting this ideal vision of an art institution designed as a politicized community space between the workshop and the academy. Both

Wang (

2022) and

Kolb and Flückiger (

2013) attribute the main reason for the fading of New Institutionalism to the lack of financial resources—a chronic problem in contemporary curation which makes a democratic art space an “unattainable utopia” (

Wang 2022, p. 610). More specifically, political bodies would deny state-subsidized art institutions support for critical attitudes (

Kolb and Flückiger 2013).

Nonetheless, the literature agrees on the fact that while the term does not frequently appear in current curatorial discourse, its legacy still lives in contemporary practice. Looking back at the practical examples of that period is still valuable, as they refuse museums’ focus on representation and instead initiate “an open, contingent learning process with viewers” (

Kolb and Flückiger 2013) (for more see

Voorhies 2016).

In regard to Relational Aesthetics, the term was created by French curator Nicolas Bourriaud in his 1998 book called

Relational Aesthetics. There, he defined Relational Aesthetics as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space” (

Bourriaud [1998] 2002, p. 113). Not only related to the arts, Relational Aesthetics is more broadly a perspective of aesthetics that opposes the classical themes of dualism, disinterest, and distance between subject and object to the

relationship with art and the environment in general.

In the Relational Aesthetic discourse, relationships are strictly intertwined with ecology and the environment under the common understanding that the environment is a common house, shared among organisms. According to Arnold Berleant, for instance, the environment is nothing but the sum of forces that constitute a continuum relationship between actors. For Gernot Böhme, fields of relationships take the name of atmospheres, which are the materialization of emotional affections. New paths for Ecological and Relational Aesthetics call to investigate the role that technology plays in the perception of relationships, in addition to the importance of emotional experiences for an effective aesthetic education (

Gambaro 2020). Applied to art spaces, this entails a museum—comprising its exhibitions and public programs—that performs as an open stage where bonds and knowledge are constantly negotiated and co-created.

While it is not within the scope of this paper to analyze these different historical approaches to museums management in depth,

4 it is useful to highlight the similarities between New Museology, New Institutionalism, and Relational Aesthetics as a base to the case studies that will follow.

Despite the potential outlined so far, institutional art spaces need to confront a certain off-putting reputation. Lingering on museums’ bourgeois heritage, exhibitions feature in people’s minds under a span of dust, as a boring and stale space. David Novitz’s argument in

Ways of Artmaking: The High and the Popular in Art (1989) provides a useful perspective. In his paper, Novitz calls out the West’s “ambiguous, almost schizoid, attitude to the arts” (

Novitz 1989, p. 213). On one hand, arts are publicly praised as repositories of our cultures; on the other, they are removed from everyday life, which contributes to people’s perception of art as “rarefied objects which are for the educated, the cultures, the élite” (ibid.). Anything that is routinely encountered and enjoyable is at best considered ‘low’, popular art or culture. In this category, Novitz mentions films, romances, television programs, advertisement, comic strips, magazines, erotica, and rock music. To the list, the centuries-old mainstream Western tradition based on dualism adds food and cuisine (

Kuehn 2012;

Perullo 2017).

5The distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art does not benefit art transformative aesthetic power. ‘High’ art has acquired the bad reputation of “irrelevant, pretentious and boring” (

Novitz 1989, p. 222), out of touch with reality, while ‘low’ art is considered bland and lacking sophistication (ibid., p. 215). Novitz considers this distinction a major crisis in the arts, and connects it to some 19th-century changes in Europe such as the primacy of economic value supported by the rise of a “staid, prudent, small-minded, tigh-fisted” (ibid., p. 220) middle class. Becoming the backbone of Western society, the

bourgeoisie established the economic value as the dominant social value. In an attempt to reject the pressure of the market-place, many practitioners rejected the materialistic, everyday dimension of art and exiled in the hyper-conceptual, detached world of art for art’s sake. And “there arose, for the first time in the history of art, a deep and intentionally created rift of understanding. The broad mass of people in European society could no longer understand the work of their artists” (ibid., pp. 221–22).

A scene from the satirical movie

The Square (directed by

Ruben Östlund 2017) is helpful in visualizing the intrenched commonplaces about the dichotomy ‘high’ and ‘low’, and the similar hierarchy between art and food. In the scene, Christian is the curator of the fictional X-Royal art museum in Stockholm and he is presenting the new artwork installation to a full audience of what seem well-to-do bourgeois art scene people gathered for its inauguration. At the end of Christian’s speech, the head chef of the museum takes the word to introduce the food which the guests are going to find at the buffet that will follow the presentation. If only the audience did not wait to hear his words that everyone is already literally rushing to the food, losing all the previously showcased composure. Comparing the shifting attitude of the audience—bored and uninterested when listening to the presentation of the artwork installation for which they are officially attending the event, while enthusiastic and disheveled when heading to the buffet—makes the persistence of the ‘high’ vs. ‘low’ perfectly visible.

One of the consequences of accepting this formal distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ is the dissociation of art from any social end, and consequentially a crisis in people’s engagement with art and art spaces. This is a crucial issue to take into account for anyone believing in the potential of art in sparking a cognitive restructuring and a shift in perspective. I argue that healing people’s contemporary dissociation with the arts requires an ecological, collective perspective.

Many, though kept to the margins, have been the artists opposed to the ‘high’ vs. ‘low’ dichotomy. One of them is artist Joseph Beuys, who brought forward a radical idea of extended and socially engaged art that is still revolutionary (and controversial) to this day. For instance, in the 1979 television-broadcasted documentary

Everybody Is an Artist, Beuys presents the careful preparation of one’s daily meal as a work of art and as an “evolutionary revolution” (

Lemke 2017, pp. 250–52). Or again, during his

Kartoffelernte (Potato Harvest) action (1977), he planted and then harvested potatoes in front of a Gallery in Berlin. In Lemke’s words, “he became ‘a farmer’ who ecologically cultivates his land, […] ‘exhibiting’ a form of an ethical praxis that is now known as sustainable urban gardening or city farming” (ibid., p. 257).

In elevating the ‘humble’ (according to the mainstream Western culture) activity of food production and cooking to the dignity of art, he aims to awaken the consciousness of the public while raising the eyebrows of conservatives, broadly challenging a hierarchical and dualistic paradigm of power which is well-entrenched in the Western legacy.

Connected to Beuys, artists such as Césan, Arman, and Dieter Roth also provide striking examples of creativity that intertwine art and food through their edible works. They were operating in the context of Daniel Spoerri’s Eat Art Gallery that opened in Düsseldorf in 1970 (

Novero 2017). Across the ocean, Gordon Matta-Clark opened in New York the artist-run restaurant FOOD (1971–1974), with Carol Gooden and Tina Girouard. And another example can be found in Rirkrit Tiravanija’s performance

untitled 1990 (Pad-Thai), when he cooked pad Thai for exhibition visitors at Paula Allen gallery in New York.

According to Blanc and Benish, Beuys contributes to the idea that “art needs not to be thought as a refuge from the impossibility to act in the real world” (

Blanc and Benish 2017, p. 35). In this regard, Perullo goes even further, calling for an inversion of perspective, from “elevating cooking to the level of art as if this would sanction its value,” towards instead “leveling art to the level of cooking. What does it mean? Thinking art as cooking means thinking it as a material practice of sensible, perishable and contingent processes” (

Perullo 2018, p. 191). The leveling of art to the level of cooking calls for a broader resolution of hierarchical dichotomies: between subject and object, knowledge and experience, mind and body, masculine and feminine, perception and cognition, culture and nature, city and countryside, etc. Therefore, I propose to adopt the same leveling perspective in other contexts: with agriculture, urban farming, and human to non-human relationships. Some scholars have been moving in this direction for decades. Among others, Arnold Berleant adds his voice to the chorus stating that “any object that acts in this [participatory engaged] way is art or art-like; any experience that joins object and perceiver is a non-transcendent unity is aesthetic” (

Berleant 1985), and therefore ecological.

Considering what has been said so far, to place labels such as ‘high’ and ‘low’ on artistic practices, cultural institution, and places might be a long overdue paradigm that has proven its inefficacy in intimately engaging people. These are issue that several curators are confronting, often in a joint effort with other disciplines that suffer of the same communicational staleness towards a shift to more “affective, material and aesthetic dimensions” (ibid., p. 134) of curation, academia and science that move beyond the catchy journalistic discourse. Engaging with this perspective, a New Museology serves as a fertile ground—literally—that hosts the “awkwardness of transdisciplinary ‘experimental entanglement’, rather than aiming to extract maximum reciprocal value from an exchange-based interdisciplinarity” (ibid., p. 135).

Luckily, I could mention many more voices and names that contributed to counter-hegemonic narratives, and my references are by no means exhaustive. My goal here is to highlight common multigenerational questioning and discourse, rather than individual contributions. Despite being more than thirty years old, David Novitz’s questions are still relevant: “why do we think it necessary to distinguish the high arts from the popular arts? Are there any grounds for this distinction? Why do so many people virtually ignore high art while at the same time professing its worth? And why are they sometimes contemptuous of the popular arts which they none the less seek out and enjoy?” (

Novitz 1989, p. 214). These questions prompt a transversal, everyday perspective rather than a hierarchical one and inspire, together with the other references I mentioned, my upcoming analysis that looks out for the points of connections, rather than the disconnections.

2.1. Food: Bigger Than the Plate Exhibition: Experimental Entanglements in Process

Creative collaborations uniting artists with farmers, and designers with chefs, are fueling new routes of inquiry, blurring the lines of art or design and allowing us to imagine different, better food futures.

Catherine Flood and May Rosenthal Slone, Food: Bigger than the Plate (2019, p. 7)

According to curators Catherine Flood and May Rosenthal Slone, the place where most often the cooking process takes place, the kitchen, is “a space packed with intangible, unrecognized knowledge and skill. It can be a powerful site of caring, of subversion and of creativity, where the lines between professionalized art and design practice, and the everyday activity […] can be blurred” (

Flood and Slone 2019, p. 93). Thus, they recognize the knowledge surrounding the kitchen as incredibly valuable. They too entangle in the blurriness of these relationship by presenting the topic of cooking in the public setting of the exhibition

Food: Bigger than the Plate, held at the Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum of London in 2019. The exhibition has been particularly important in the history of food in exhibitions because of the broad narrative proposed, merged with the prominence of its setting: the V&A was founded in 1852 and is currently the world’s largest museum of design, applied and decorative arts. In the following paragraphs, I provide a plethora of narratives introduced in the

Cooking segment—one among the four sections of the exhibition which are

Composting, Farming, and

Trading.

The

Cooking segment engages with several facets of cooking in the West from the early modern period to the present, starting from the development of the cooking space—namely kitchen design—and how that influenced the cooking process throughout time. A long-lasting debate about efficiency vs. experience emerges, together with the current appeal for a “kitchen of the future” that values the experiential more (

Sugg Ryan 2019, p. 101).

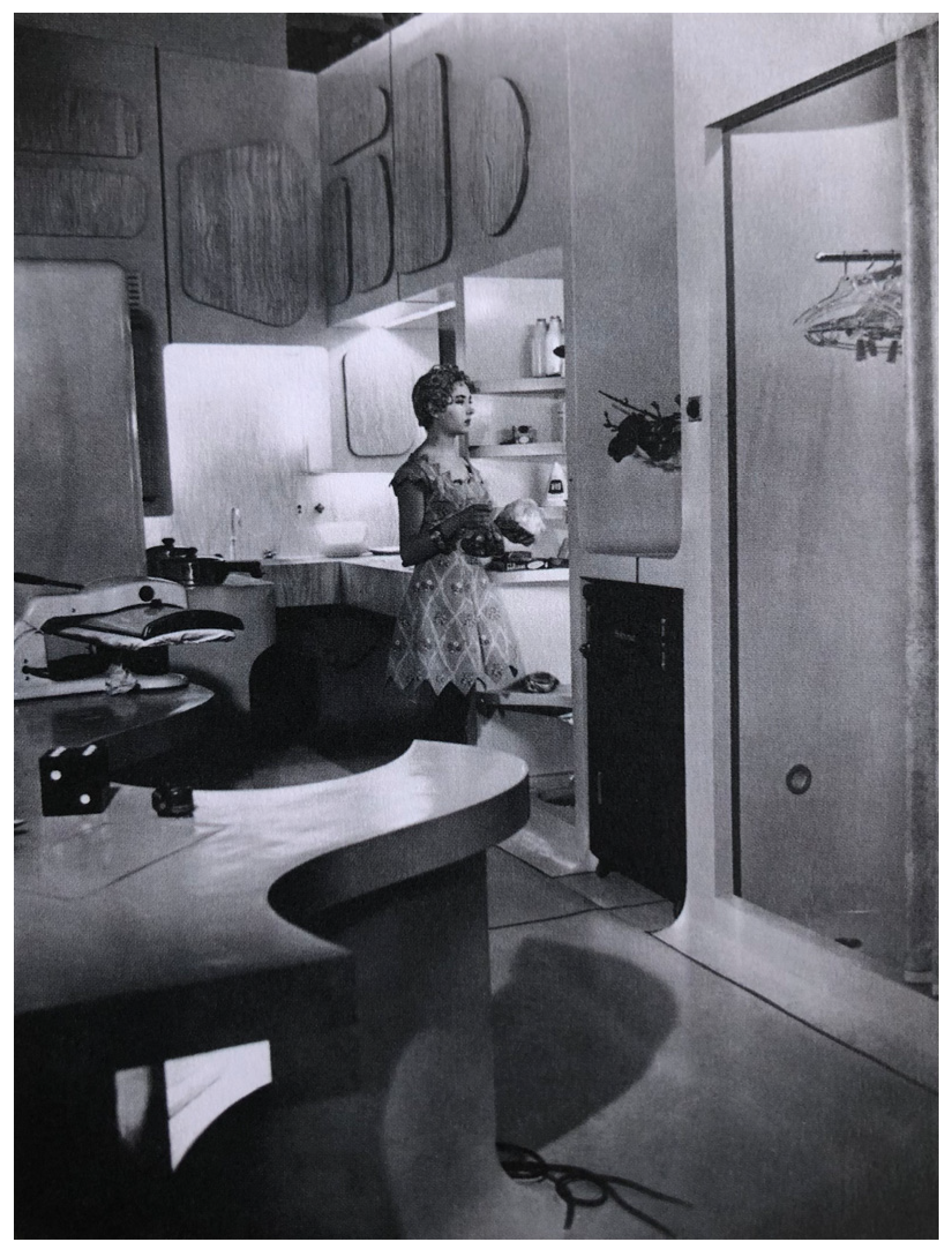

During the 20th century, there is a rich history of how creative professionals, particularly architects and designers, have been imagining the kitchen of the future in exhibition settings and world fairs in a way that reflects society’s preoccupations over time.

6 An emblematic early example is that of the

Frankfurt Kitchen (

Figure 1), designed by architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky in 1926 as part of the

New Frankfurt social housing project in Frankfurt, Germany. Schütte-Lihotzky’s design radically reorganized the layout of the kitchen to improve time efficiency while reducing production costs in order to respond to society’s increasing pace of life. During those years, many other professionals explored the same and other principles, which is reflected in the exhibition of kitchen designs at the 1927

Werkbund exhibition in Stuttgart, at the 1929 exhibition

Die neue Küche in Berlin, and in the projects proposed for the low-cost housing programs. All of them, Bullock argues, “confirm the importance accorded to the kitchen as central issue in the design of the New Dwelling” (

Bullock 1988, p. 188).

Another instance is that of Alison and Peter Smithson’s

House of the Future (

Figure 2) presented at Britain’s annual

Ideal Home Exhibition in London in 1956. It envisioned solutions that would make the kitchen more hygienic and time-saving. In the 1962 cartoon series

The Jetsons, the kitchen of the future is instead fully automated through robots, a forecast which proved particularly resonant in the present moment (

Sugg Ryan 2019, p. 103).

Presented in the exhibition, a progressive example of what the kitchen of the future should look like is embodied in the open-plan kitchen design at a Maggie’s cancer care center in Newcastle (UK) by architect Charles Jencks (

Figure 3). The 2013 project envisioned an open-plan kitchen in place of the entry hall, which invited people to make themselves a hot drink upon arrival and enter the space in a less formal way. Jencks claims that “the centrality of food and drink allows people to enter and exit without declaring themselves, try things out, listen or leave without being noticed. You can insinuate yourself in the kitchen on any number of pretexts” (ibid., p. 102). He calls this concept

kitchenism, where the kitchen table is the “central hub for social interaction, enabling conversation, mutual support and friendship” (ibid.).

A further narrative line explored in

Food: Bigger than the Plate is that of gendered labor. Curators problematize women managing of the kitchen even in the scenario where labor is automated, while men tend to “be depicted at leisure in the kitchen” (p. 104). In the exhibition, traditional gendered labor is represented merging with the kitchen of the future to highlight how the notions of progress and technology are wrongly associated with neutrality. In fact, they reproduce the social hierarchies of the people who design and produce that technology. As

Rose Eveleth (

2015) and

Sarah Kember (

2016) argue, “technology companies and futurology tend to be dominated by men” (in

Sugg Ryan 2019, p. 104). This is something that the etymology of technology reflects, from the Greek “téknē” and “-logía”, which, respectively, mean “art, skill of craft” and the study of something (

Wilson 2012, p. 5). This root reaffirms the nature of technology as humanity’s tool or craft, prompting us to see appliances in an ambivalent way, embedded in our own human bias and therefore reflecting any social and gendered structure already in force.

Continuing on the line of technology, the exhibition curators problematize the role of smart kitchens, in which electrical devices are increasingly adaptable following a development of artificial intelligence (AI). The curators trace a trajectory for appliances’ growth starting from their participation to the

Internet of information, followed by the

Internet of intelligent things, and culminating in a near future of

Internet of actions, in which robots are forecasted to fill kitchens, “talk to each other and act on our behalf” (

Sugg Ryan 2019, p. 104). This scenario carries both promises and risks, expressed through the notion of the

Internet of creepy things (ibid., p. 109) which the exhibition considers through the examples of some popular Western appliances, such as Amazon’s Alexa and multi-function electric cooking pots.

In the comparison between the high-end Thermomix multi-function cooking devise and the more affordable Instant Pot multi-functional electric pressure cooker, Sugg Ryan clearly takes the stance for the latter in terms of inclusivity, social progressiveness, and sustainability. She notes that the Instant Pot success was strongly connected to its community of users which recognized the product as the “center stage in cooking practices [which] also creates a sense of attachment by being an agent in our social and emotional lives” (p. 108). On the other hand, the Thermomix 2018 promotional video ad seemed “depressingly stuck in the 1950s” (p. 106). It still reiterated gender roles which show themselves in the choice of a female narrator and the scene of the (working) mother concurrently taking care of the mental and emotional task of planning and executing meals for the family. The narrative seems to problematize the meaning of progress, as the promises of new devises often partake in the reiteration of old dynamics.

Moving to the exhibition catalogue of

Food: Bigger than the Plate, the curators and editors dedicated the last section to 11 recipes, each embodying a different (and overlapping) set of narratives and entanglements: protein futures; closing the nutrient loop; feeding the microbiome; embodied knowledge; sensory eating; cultural connection; open source; culinary diplomacy; feeding loved ones; eating in museum; community action. Through these recipes, hospitality and conviviality are encouraged beyond the exhibition temporary nature in space and time. For instance, the community action recipe invites the readers to organize jam-making workshops following the example of the art collective

Fallen Fruit, which was originally conceived in 2004 with the goal of gather people around the collection of fallen fruits in urban public spaces, while encouraging “action, fun and discussion” among them (

Flood and Slone 2019, p. 161).

All the other recipes emphasize narratives of collaboration involved in food growing and the cooking process: between the butcher and the chef to redesign the meat sausage into a fruit-based one (ibid., p. 149); between humans and mushrooms when grown from used coffee grounds (p. 150); between humans and bacteria in the fermentation of drinks (p. 151); between female ancestors and new generations in an intergenerational exchange of expertise that values the embodied knowledge of women which was and still is taken for granted because involving daily and domestic tasks (p. 153); between people, their own bodies and senses: their hands, their mouths, in a playful engagement as proposed by Giulia Soldati’s sensory eating recipe (p. 154); between immigrant people, their communities of origin and those of arrival (p. 155); between people, research, supply chains and industrial production (p. 156); between people with different backgrounds or even separated by biases, such in the case of the Iraqi–American recipe workshops of the

Enemy Kitchen project (p. 158); and finally, between people and everyday acts of care and love (p. 159).

7 2.2. Living Furniture at Milan Design Week 2015/2016

I imagine the current design world as an organism. What does it eat? What does it excrete? Well, I see it shitting chairs […]. Is there still a large need for our societies to find out how to sit? […] Do we need more chairs and what do we need to design instead?

Mathilde Nakken, Make Food, Not Chairs (2017, pp. 7–8)

The provocative opening quote by Mathilde Nakken, Dutch design student of the Food Non Food course at the Design Academy Eindhoven, helps me to introduce this second part. The section brings to the foreground the perspective of the designer in its relationship with food in the context of Milan Design Week 2015 and 2016. This section is inspired by the similarities between designing and cooking. Some questions that have directed my reflection have been: if designers worked as growers and cooks, what would their ingredients be? In which processes would they engage? Which dishes would they produce? Of course, it should be defined which kind of growers and cooks is implied in the questions, an aspect that the next case studies are going to suggest.

Nakken’s 2015 manifesto project

Make Food, Not Chairs is a strong example of the designer ecological approach. In the design and architecture field, it is common knowledge that chairs are the statement piece that designers and architects use to exemplify their philosophy and style of work. However, in her manifesto Nakken proposed a critique to the wasteful culture of consumption in which designers partake, one that just creates “products and furniture which are pleasing to the eye” (

Nakken 2017, p. 3).

The manifesto was presented during the 2015 Milan Design Week as part of the

Food Non Food class exhibition titled

Eat Shit. In that occasion, Nakken and her classmates created and built stories around the subject of design, food, and digestion (ibid., p. 4). One of the projects presented was the

Digesting Stories Bakery, in which bread was used “as a material to work around the topic of poop” (p. 6). To that purpose, two ovens, 75kg of flour, and some sourdough cultures were transported from Eindhoven to Milan, where the students baked 100 classic design chairs in miniature made of bread (

Figure 4).

The miniature chairs would not last long after being baked, and precisely their fragility triggered the curiosity of visitors, giving “a tender relationship with the spectators, unless the bold statement they made” (p. 8). Despite being fragile, the bread chairs were made to be smelled, touched, and eventually eaten, “followed by the digestion of the design, and eventually poop it out” (p. 7).

The peculiarity of the pieces made them unforgettable and ignited conversations about design practice and its need to be endlessly redefined. The project aimed to establish “digestion and metabolism as aesthetic values for a relational and processual model” (

Perullo 2022, p. 121), but it also ascertained designers’ responsibility towards what they create. Nakken sustained that “in the moment you create, you are the one responsible for the material of the product and the globe on which you will launch it” (

Nakken 2017, p. 7). However, not all visitors would agree with Nakken’s vision, starting from the Design Academy director Thomas Widdershoven. Nakken recalls the fruitfulness of the heated debate she had with Widdershoven, who argued that designers should not take on big responsibilities. Without expecting designers to solve all the problems of the world, in Nakken’s view they can tackle complex issues by starting from the local scale, having a long-term perspective in mind, working holistically and in collaboration with other disciplines and even as catalyzers of different connections. I argue that this approach echoes that of cooks or farmers who work closely with the land.

In Glenn Kuehn’s words, it can be argued that “food is more than merely edible—it is an insight into the way we construct various environments” (

Kuehn 2012, p. 85), food is an “edible expression of a place” (ibid., p. 90). This crucially implies that food can carry an environmental education. In the specific case of Nakken’s edible chairs, the fact that people eat them opens up an embodied experience, therefore also the aesthetic potential for a very intimate relationship that can change us “on a level of inherent and (though it is often hard to face) inescapable involvement with one’s environment” (p. 92).

8 Additionally, the anecdote of the discussion between Nakken and Widdershoven exemplifies the dialogic potential of such projects. Lee argues that such dialogue is not only happening between people, but also within one’s self as a dialogue of inner worlds (

Lee 2022).

The project Make Food, Not Chairs was later exhibited at the Paris Design Week 2015, for which Nakken baked a second series of new designs. As part of the soon later Dutch Design Week, the project was also exhibited at Coffee You, alongside the new production of a real-size bread chair in collaboration with Broodt bakery in Eindhoven. Nakken arrived at the clear realization that “we should bring food closer into the living environment. Having a bread chair at the dining table can contribute to a wider understanding and appreciation of our food. Now we hide everything we eat in cupboards and fridges. In the future I hope to sit, stand and sleep together with what I eat” (ibid., p. 14).

This awareness was the foundation of her third-year project called LACKING, which intended to discuss our connection to mass-produced furniture by growing a living mushroom table. Rethinking a popular Ikea design, Nakken’s project consisted of a step-by-step guide to growing tasty oyster mushrooms out of a LACK coffee table. The statement she aimed to make was that “a living table, which feeds you, asks for a completely new approach. Your coffee table almost becomes your pet” (ibid.).

In 2016, at the new edition of the Milan design week, the same thread of topics was picked up in The Shit Evolution installation curated by Luca Cipelletti for the Shit Museum. The exhibit presented tableware, seats, and tables made of merdacotta, which stands for a patented material made of dried cow dung by-product and clay. As it happens, in mainstream production, these examples of chairs and tables do not lack the intention of embodying a statement. In this case, it strongly emphasizes the production process rather than the end product. The material used, in fact, was unique and borne out of a closed-loop system, from the necessity not to waste anything as it would happen in a zero-waste approach to cooking.

Additionally, there is a clear provocation hidden in the choice of names for The Shit Museum and merdacotta (literally ‘baked shit’). Similarly to English language, there is a ‘high’ and ‘low’ way to refer to feces which would correspond to excrements (in Italian: ‘escrementi’) vs. shit (‘merda’). The founder of the museum and the curator intentionally used the ‘low’ word associated with the ‘high’ environment of the Milan Design Week. The Milan Design Week awarded the project, praising the storytelling of a process of great complexity and innovation, capable of destabilizing common perception. In fact, similarly to the edible chairs, people are intrigued by the project. There is not a single person with whom I discuss The Shit Evolution project that does not find it comically absurd and wants to know more about it. Going back to Novitz’s schizoid attitude towards the arts, this project aims to challenge the disconnection between people, design, and the environment.

9Going back to merdacotta, the starting ingredient in the recipe was cow dung, hiding a plethora of uses beyond being a fertilizer for agricultural purposes. The dung came from 3500 cows that produce 1500 tons of it each day, in the Castelbosco farm in the province of Piacenza, in the north of Italy. In the several stages of processing, the ‘dung ingredient’ releases electricity and heat, is turned into fertilizer, and is finally implied in the making of merdacotta. Cipelletti states that “there is no more that thing called waste material, even the leftover of the leftover of the leftover of the processing becomes a product which feeds the vital cycle of the farm” (

Petrolio 2017, min. 4:47). In this process, the lines between designer, curator and an agricultural entrepreneur are incredibly blurred, and the final result on the ecosystem is nourishing.

The Shit Museum was inaugurated in 2015 as an integral part of the farm by owner and agricultural entrepreneur Gianantonio Locatelli, who challenges mainstream canons of both what it means to be a farmer and a creative practitioner in the arts. He argues that the ecological paradigm suggested by The Shit Museum project has the potential to spread to other fields, creating a “cultural and aesthetic revolution of social norms” (ibid., min. 3:25). Locatelli says to be inspired by the concept of transformation (ibid., min. 5:25), which is found in the agricultural wisdom of closed cycles, borne of out of necessity and scarcity. This does not mean being nostalgic of an illusionary better past; it means bringing centuries of Western indigenous practices and knowledge into the present and future. Going through a process of endless refinement in dialogue with their land is what growers and cooks do, respectively, adapting to ever-changing climate conditions, and reinterpreting traditional recipes.

Make Food, Not Chairs, the LACKING living mushroom table, and The Shit Evolution exhibit are emblematic examples of a historical line of resistance in design sensitivity that can be traced back to movements of early industrialization and commodification critique, such as the Arts and Crafts movement in mid-19th century Britain. The dualistic, neo-liberal, capitalist paradigm that these artistic movements oppose is the same system that holistic agriculture refuses. Their joined ecological and relational perception of the world calls for a merging of the narratives of the arts and food, which are normally kept separated by the economic interests gained in alienation.

In the milestone text

Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change (

Papanek [1971] 1985), Victor Papanek describes the power imbalance present between two perspectives. The first approaches design practice as integrated in its ecological and relational environment, while the other, mainstream one, utilizes design as a tool for consumerism. Although a dated text in some ways, I aim to highlight the portrayal Papanek makes of the marginal position that food had in mainstream design thinking in the 1970s, tracing its legacy in contemporary design thinking.

Being a forerunner of ecological sensitivity in design, food takes up a great portion of Papanek’s reflection, who strongly critiques design subjugation to capital even in agriculture and food-related environments, denouncing the fact that “food production and the development of new food sources have been of no interest to the design profession at all”, while also claiming food importance as “

designers are involved, like it or not, as human being” (

Papanek [1971] 1985, p. 278 [emphasis in original]). Since then, the reading of Papanek’s work in design universities has highly influenced an approach to biological systems design that relates the practice of making to its sociological, psychological, cityscape surroundings through ecology and ethology. The ecological and relational paradigm transpiring from his critique is strongly visible, not least when he writes about design education: “the main trouble with design schools seems to be that they teach too much design and not enough about the social and political environment in which design takes place” (ibid., p. 291 [emphasis in original]).

Contemporary examples, therefore, are not showcasing a brand-new sensitivity, but developing an ecological heritage whose voice has been marginalized in history narratives. The reading of Papanek’s work keeps inspiring designers regarding the importance of a careful and also ruthless review of their engagement with the environment.

2.3. Care and Conviviality at Venice Architecture Biennale 2021

The collective preparation and cooking of meals, as well as sharing recipes and hearing each other’s stories are among the most effective ways of bonding and creating a sense of trust that is essential.

Herkes İçin Mimarlık collective, Politics and the Power of Eating (2019, p. 111)

The ideal model of food, cooking, and eating as core activities of care and conviviality can be also found encompassing three projects presented at the

Biennale Architettura 2021: How will we live together? exhibition. The first example is that of the Nordic Pavillion—comprising Sweden, Finland, and Norway—curated by the National Museum Norway with architecture studio Helen & Hard. Their project addresses the Biennale theme by transforming the pavilion space into an experimental co-housing project titled

What We Share: A Model for Cohousing (

Figure 5). The concept was inspired by the real 40-unit cohousing project Vindmøllebakken, located in Stavanger, Norway, that the architects completed in 2019. There is where they themselves reside (

Figure 6).

The kitchen space and the tables where to eat convivially are the protagonists of the cohousing model activities that shift from a concept of private to one of semi-private. Certainly, architecture plays a crucial role in this possible evolution, to which Siv Helene Stangeland (Helen & Hard co-founder) states:

I think architecture is currently understood as purely related to economic investment, whereas it should be seen as an investment in our commons. Ideally, it should: nurture potential of a place and its inhabitants, which is specific and unique; be inclusive to people, local resources and the physical environment at hand; provide the necessary social and environmental care and consequent transformation; invite us to meet and find meaning on a collective level; inspire us to contemplate and value nature and move us with beauty.

Stangeland’s choice of vocabulary could easily be interchangeable with agroecology and cooking: nurture, local resources, and the physical environment at hand, care, and collective level.

The second project example is offered in the section

As New Households, which explores the theme of communal living accounting for the emergence of more fluid relational and cohabitation patterns than the traditional family composition. In such a context, the concept of hospitality is extended to the more than human in the

Refuge for Resurgence installation by London-based studio Superflux (

Figure 7), which was also later included in the 2022 exhibition

Our Time on Earth at the Barbican in London. The installation imagines a multi-species community dining among the ruins of modernity to find new ways of living together. It consists of a banquet table set with designed crockery for 14 different species. Through this exhibit, Superflux aimed to convey the message of equal status between species and the importance of their collaboration. Visitors can imagine sharing a meal with a host of other creatures similarly to how Perullo communicates the relational paradigm through the metaphor of the apartment block. Drawing on Donna Haraway’s insights, he envisions humans living with other beings as neighbors. This kinship would not resolve in a less, or post-human epoch, but a more-than-human as well as “more human” one (

Perullo 2022, p. 10), meaning infused with more empathy towards, and awareness of, the neighbors (ibid., p. 12). As if we were participating at a meal together, Haraway would add technology to the entanglement, speaking of a “commensal technological lifeworld” in which critters are “commensals, neither benefactors nor parasites” (

Haraway 2008, p. 253).

The third project example also involves a table and is presented in the Central Pavilion within

Linking the Levant. The exhibit negotiates the sharp political divisions in the Levant region by offering examples of architecture that mitigate those same conflicts. The Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST) presents

Watermelons, Sardines, Crabs, Sands, and Sediments: Border Ecologies and Gaza Strip, an exhibit that represents a table as a convivial place par excellence. It traces over ten years of transformation of a small farm in Kutzazh located along one of the most militarized borders between Gaza and Israel. Ten stories highlight how the activities of growing, harvesting, and fishing are inevitably affected by Israeli-imposed restrictions and continued violence. Accessories and textiles decorated with watermelon, sardines, sand, and sediment, linked to bureaucratic protocols, appear on the dining table. There is also a less immediate but profound meaning to the table: around it, the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory (FAST), Malkit Shoshan family, and Qudaih family (the owners of the farm) conversed during the months of research. In the course of that process, the table participated as a place to discuss hope. However, at Biennale, the table was shown empty. Because of the bombing, the Qudaih family could not move to reach the exhibition, and this aspect added a further meaning to the table, where absence plays a warning symbol (

Arrighi and Giberti 2021).

Not included in the 2021 Venice Biennale, I would like to nonetheless mention two final examples of ecological architectural practice that relate to the previous ones through their symbolic use of the table: Earth Table (2013) and À table (2023).

The Herkes İçin Mimarlık (HiM) (Architecture for All Association NGO) is a collective of 95 architecture and design students and professionals based in Turkey. Throughout its projects, HiM utilized cooking both literally and metaphorically, as it believes that “collective preparation and cooking of meals, as well as sharing recipes and hearing each other’s stories are among the most effective ways of bonding and creating a sense of trust that is essential” (

Herkes İçin Mimarlık 2019, p. 111).

Alongside cooking, the table often recurs in the HiM collective imagination as the best representation of a place were critical intimacy takes place. The HiM is particularly interested in how the concept of hospitality creates a spatiality and shapes architectural components, which range from communal ovens to street vendors up to the table, in that they are all instruments that “blur the traditional roles of guest and host” (ibid.). One powerful example is that of their 2013 project

Earth Table (

Figure 8)

10, a communal fast-breaking meal during Ramadan that took place in a busy street of Istanbul. The meal was organized as a protest against the governmental urban development plan for Istanbul Gezi Park, which according to the government was not utilized as a public space.

The image of the

Earth Table holds a great power both in terms of visual impact for those that did not attend the event, but also in terms of collective memory for those who were present. It sets an example of how ordinary rituals like that of eating, in ordinary and public places, can actually mediate resistance and transformation in a meaningful way.

11The echoes to this ethos are countless: most recently, the 2023 London Serpentine Pavilion project features a large circular table with chairs. It is titled

À table (

Figure 9), the French equivalent of “lunch/dinner is ready”, a call to sit together at the table to share a meal. Designed by architect Lina Ghotmeh and her team, the structure aims to be “a space for grounding and reflection on our relationship to nature and the environment” (

Serpentine Gallery 2023), and invites visitors “to convene and celebrate exchanges that enable new relationships to form, considering food as an expression of care and offering a moment of conviviality around a table” (ibid.). Indeed, the space welcomes to “share ideas, concerns, joys, dissatisfactions, responsibilities, traditions, cultural memories, and histories that bring us together” (ibid.). The project is a tribute to spaces and atmospheres of intimacy, and takes its inspiration from Ghotmeh Mediterranean heritage but also from togunas, traditional structures used in Mali, West Africa, for community gatherings.

In these projects, food and communal kitchens are presented as instruments of occupation that enable bonds between people and a diversity of backgrounds to emerge through the creativity and spontaneity of communal cooking and eating. In these spaces, narratives and consequential identities are formed as the result of a process of intimate negotiation.

3. An Ecology of Exhibitions through the Concept of Hospitality

In recent times, the concept of hospitality has found its way into the curatorial field in a number of forms. In art, food and meals are routinely used as a “materialization of guesthood” for a very literal engagement with hospitality.

Beatrice von Bismarck, The Curatorial Condition (2022, p. 141)

From the narrative proposed so far, it seems food representation swings between being instrumentalized and being a genuine common, two faces that in reality coexist. In terms of product and furniture design, new living materials are a good start but not enough alone to challenge broader perspectives, something Chapman considers a “symptom-focused” approach (

Chapman 2005, p. 25). Products need to be backed up by philosophical depth; otherwise, consumption will simply shift from new to recycled materials, and in the same way, it is not enough for a chef to limit his engagement to personal action if the bigger system is still operating under different values.

On the bright side, there is something to be said about the potential of highlighting hospitality in exhibitions, intended as that atmosphere of intimacy that “blurs the traditional roles of guest and host” (

Herkes İçin Mimarlık 2019, p. 111). At the same time, I am not sure to what extent the mentioned case studies had an actual impact on informed opinion development or a better political agenda. Therefore I acknowledge my argument as more theoretical in the last and concluding part when considering the concept of hospitality in exhibitions.

Firstly, arguing for an ecology of exhibitions—as the study of the relationships that take place in the exhibition space—reinforces a certain responsibility of those that are primary actors in the development of such exhibition spaces, such as curators, artists, designers, and architects. Drawing from Jennstål and Öberg’s analysis of the use of provocation in art exhibitions, I argue that it is not enough for these figures to only instigate; rather, they should help to sustain a dialogue in mass space about important collective matters and certain community attitudes (

Jennstål and Öberg 2019, p. 9). Exhibitions come to be through the practice of curatorship, which mediates how culture becomes public and therefore can play an important role in communicating ecological awareness and citizenship (

Bismarck 2022, p. 8).

Nowadays, the curatorial practice is a cultural production in its own right, which emphasizes participation, coming together and being together in public. The borders of curatorial authorship expand to recognize the fact that the final exhibition is a constellation of interactions between actors, things, ideas, and not just the product of the curator’s vision. Aligning with Beatrice von Bismarck, I bring forth an idea of curatorship which constitutes a space of conviviality, one that is formed through negotiation, which can be positive or negative depending on the level of openness and awareness of the parts in dialogue. The core aim in Bismarck’s book

The Curatorial Condition (2022) is to shift the emphasis from a dichotomous paradigm focused on separate subjects and objects (such as the curator, the exhibition, etc.), towards instead highlighting the relational paradigm in the curatorial practice which accounts for the interplay that constitutes the participants. She introduces the term

curatoriality (

Bismarck 2022, p. 8) to indicate the fabric of relationship of which the curatorial practice is made. These relations are made by a vast range of human and non-human participants that co-create aesthetic experiences. Specifically, they are, among countless others, curators, artists, designers, architect, creative practitioners, critics, cultural institutions, exhibits, and the public. Nonetheless, this “transdisciplinary cocuration” (

Bencard et al. 2019, p. 133) does not come without challenges.

Historically, in the 1960s, a shift from objects to experiences started to be spotted in the practice of the Italian architecture and design group

Archizoom Associati (

Bismarck 2022, p. 9). As a response to the globalization and commercialization of the cultural field which occurred more prominently after 1989 and entailed art institutions booming all over the world based on the North American and European model, exhibitions started a dynamic process of mutation, together with the professional figures and the cultural institutions connected to them (ibid., p. 11). For instance, the boundaries between professional roles became more and more fluid and blurred: scholars became at times curators, such in the case of Bruno Latour for the several exhibitions at the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.

Bismarck remarks how “the exhibition format has an inherent potential for action, helping to actively shape the relations that constitute it” (p. 12). Recalling its Latin etymology, curating comes from curare, “to care”, which is at the base of exhibition making. However, care is an ambivalent and relative position which hides and shapes “the presence of conventions, narratives, discourse, and attribution of value” (p. 10). Like any other storytelling, exhibitions can on the one hand back up the narrative of those in power or, on the other, help the understanding of “hierarchies, dependencies and privileges” (p. 15). Bismarck remarks: “exhibitions—and by extension other formats like books, invitation cards, or performances—establish public relations in which, from a sociological viewpoint, artwork function as ‘social media’. This means that exhibitions and art, in general, can perform as a social media: a medium through which relationality flourishes” (ibid.).

The relational nature of exhibitions is what turns them into a performative practice which, through the participants’ processes of becoming, brings about new meanings and narratives. Other two aspects bring exhibitions closer to performance: the fact that they have a limited duration and, when they tour, they restage in another place as a performance would do, which entails renewed relations. Secondly, exhibitions rely on a collective structure made of interdisciplinary figures. Leaning on Bismarck, I argue that one of the greatest political potentials of the discipline lies in the curatorial transversality because what is at stake is participation, the shaping of power struggles, inclusion or exclusion, and ways of representation.

Parallel to its relationality potential, Bismarck also problematizes the politics of publicness to which the curatorial partakes, pointing to the fact that there is a fine line between recognition and public visibility. In other words, the becoming public is easily appropriated by what scholars have differently defined as the distribution of the sensible, the visual regime, the economy of visibility, or the attention economy—philosopher Gernot Böhme also speaks of aesthetic capitalism. These regimes/economies imply publicness as a currency and a form of capital on which to profit (p. 23). We can resume again Perullo’s position because, in a way, it can also be seen against the economization of the public when he argues against the tyranny of sight, the visible and the material, as long as they are used in a dichotomous perspective of reality (

Perullo 2022, pp. 7–8).

Like everything else,

curatoriality is not exempted by ambivalence and contradictions. The curatorial is, after all, historically rooted in the development of the middle-class and industrialization since the 18th century. A graft-like departure from that origin started to develop within the 1970s feminist and postcolonial debates (

Bismarck 2022, p. 22). In

The Curatorial Condition, Bismarck explores three main concepts—constellation, transposition, hospitality—and takes into analysis some exhibitions as case studies for each of them. I focus a little further on the last concept, hospitality, to which Bismarck argues:

with aesthetic, economic, political, social, and not least ethical implications, the dispositif of hospitality is the arena in which it is decided whether and how questions of aesthetic experience, of recognition and exclusion, of distribution of resources and generosity, of power and hierarchies, and of care and responsibility are dealt with in curatorial terms.

The concept of hospitality, whose philosophical complexity cannot be unraveled here, is closely entangled with another concept, care, already mentioned in regard to curatorship etymology. Hospitality on the side of food, and care on the side of curatorship, represent two of the greatest features of food and curatorship that, when intertwined, can generate powerful synergies. Both need to be handled with care as they inevitably carry ambivalence. Indeed, in

Outline of a Theory of Practice (

Bourdieu 1977), Pierre Bourdieu refers to hospitality as a form of symbolic violence:

the gentle, invisible form of violence, which is never recognized as such, and is not so much undergone as chosen, the violence of credit, confidence, obligation, personal loyalty, hospitality, gifts, gratitude, piety—in short, all the virtues honored by the code of honor—cannot fail to be seen as the most economical mode of domination.

(p. 192)

On the other hand, in

Of Hospitality (

Derrida and Dufourmantelle 2000) Jacques Derrida appeals for unconditional hospitality as a moral imperative to correspond with the other, to attend the encounter. The two positions are not mutually exclusive, as in a necessary practice of unconditional hospitality there can be an infinite and unquantifiable spectrum of encounters that range between the positive and the negative. Therefore, before being a hospitable practice, hospitality is a commitment to participate in relations. This commitment involves assigning and accepting responsibility as response-ability (

Haraway 2016).

Transferred to the curatorial context, curatorial care-based responsibility emphasizes the service orientation of the curator’s role. Curators are responsible for the making of place and the allocation of space, which can be a public or an institutional one. To the distribution of space follows that of other resources such as “time, funds, materials, attention” (

Bismarck 2022, p. 143), which create the environment through which encounter, exchange, and mediation among actors take place.

In the past years, there have been many exhibitions flourishing on the themes of hospitality, food, and ecological perception in Western capitals. All of them seem to have a reflective approach towards how the curatorial can mediate the unfolding of relationality. Bismarck defines curatorial caring as “a situational, transformative ethos” (ibid., p. 145), echoing philosopher Maria Puig

De la Bellacasa’s (

2017) interpretation of care as a form of participating in the becoming of things, avoiding a simple, non-situative categorization of care, and emphasizing its transformative ethos. Ultimately, hospitality is not a fixed noun but it is a performing conviviality (

Rosello 2013, pp. 132–33), constantly reshaping relations and possibilities of participation, which performs in art and food spaces alike, intertwined.

4. Conclusions: Risks and Paths Forward

I have attempted to reflect on the representation of food, cooking, and eating in the confined space of the exhibition. Through the set of chosen examples, I have also tried to highlight how strongly the entanglements and narratives, however imperfect, relate to the world outside of the exhibition walls. The narratives of food, cooking, and eating are meant to contaminate the visitor and propagate the dialogue on those themes into the world, in the homes, and in the streets. These dialogues are opportunities for relationships to develop around social synergy. In a flexible and open mindset, people learn and work together.

Nonetheless, there is a critical stance to take towards exhibition making as it is turning into blockbuster mass production aligned with aesthetic capitalism, similarly to what happens for Hollywood movies. In Chris Fite-Wassilak’s review article of

Food: Bigger than the Plate for

E-Flux, he argues that the exhibition is not challenging the consumerist and neoliberal system enough, giving “only a token acknowledgment of the realities and the efforts behind our food systems” (

Fite-Wassilak 2019). He further states that the narrative presented suggests that “all the waste we produce by eating, it seems, can go back into the commodity market just fine” (ibid.). What struck him

isn’t so much the attempt to use food as a way to anchor the body […], but more how this reflects a wider circular issue in the show, and often food in general: how we are prepped, or prep ourselves, for an experience, looking out for delight or disgust, and then finding exactly what we were looking for. The “Food” exhibition is heavily peppered with exotica intended to weird out tame urbanites.

(ibid. [my emphasis])

His critique continues a fruitful and never-ending reflection on the stories implied in exhibition making, claiming that the exhibition is itself the product of a consumerist middle-class society that produces and consumes its own narratives: “the overall atmosphere of ‘Food’ is of a swish trade fair that, rather than suggesting necessary modifications to what and how we’re eating altogether, offers well-designed, consumer-friendly products that tweak on the outputs of the current system, implicitly telling us it’s OK to continue as we are” (ibid.).

A similar and broader interpretation of Western societies’ relationship to consumerism can be found in Chapman, according to whom we currently live in a “fast-food culture of nomadic individualism and excessive materialism”, in which “empathy is consumed not so much from each other, but through fleeting embraces with objects” (

Chapman 2005, p. 26). In this scenario, “waste is symptomatic of failed relationships between products and users”, specifically, “the failure to sustain empathy” (ibid., p. 20). Consumption, whether of an object, food, or people—

Papanek (

[1971] 1985) calls it the

Kleenex culture—is a way of being, and we interact with the world through it. Chapman argues that we

will always be engaged within this process. We are consumers of meaning and not matter. […] Material consumption operates on a variety of experiential layers […] and consumers mine these layers, unearthing meaningful content as they steadily excavate deeper into the semiotic core of an object. If one of these layers should fail to stimulate, the relationship between user and object immediately falls under threat. […] In marketing […] the disappearance of a response due to lack of reinforcement is a hazardous stage in the subject-object relationship.

I would stress the

disappearance of a response as a crucial aspect of the culinary humanities that this open call suggests. As already pointed out,

Haraway (

2016) stresses that responsibility comes from a

response-ability, the capacity to be present in the encounter, and, when that is threatened, the ecosystem of balanced relationships follows along. It is, therefore, necessary to speak of a sustainability of meaningfulness, narratives, identities, and of empathy, although meaning is highly context-specific and creative practitioners cannot fully control it; they can rather direct it (

Chapman 2005, p. 54). In the creative process that engages both mind and body as a whole, that shapes ideas through the engagement with the matter, what can lead to a nurturing and empathic relationship is leaving space for “discoveries, randomness and intimacy” (ibid., p. 56).

When the encounter subject-object develops successful degrees of intuition, “the boundaries between flesh and polymer disintegrate to make way for new and provocative modes of material engagement” (p. 81). As I face in my daily experience the negative heritage of the materialist society which brings people to think of materiality and ethics as polarized and irreconcilable, I argue for a dawn of a positive materialism in which objects are not simply mirrors of our ego, our desires and aspirations, but partners with whom we engage life and broader ecosystems. In Berleant’s words: “in art there is not object. A painting or any ‘object’ in art is a means, an instrument, no, better, a party to aesthetic experience” (

Berleant 1985).

Despite calling for the longevity of emotional attachment and the empathic and craft-like engagement which are acquired slowly over time between user and object, Chapman’s text is constellated by subject–object references, and it is not fully clear whether his reflection still operates within a dichotomous paradigm where the user is in a restless state while objects are “static, possessing non-evolutionary souls” (

Chapman 2005, p. 67). Walking on the lines of conflict that emerge between a subject–object paradigm and a relational/processual/ecological one, I propose an understanding of exhibitions as “experimental setups in the process of becoming that explore themselves in the moment of showing themselves, and, in the knowledge of their own ephemerality, continue to exist in a different way but never entirely without the traces of this exploration” (

Bismarck 2022, p. 84).

Under this assumption, empathy and hospitality in exhibitions avoid both subjectivation and objectification, which Bismarck recognizes as common notions of the curatorial. The curatorial itself is in need of a (self-)reflection and (self-)critical historiography. This kind of relational approach creates meaning that is always derived, and not a priori, to the curatorial relations, and enables a critical engagement with historical narratives, “making for a distribution of tasks, responsibilities, and powers that is more complex because temporary and interchangeable” (ibid., p. 85). Curator Marco Scotini recognizes few instances of true cultural innovation as the result of curatorial openings, against the market force that reclaims art as individual production of separate, original, and autonomous art works as necessary forms of capital (

Scotini 2021, p. 16). However, most often curators themselves respond to the politics of what he calls the “exposure machine” (ibid., p. 24), which is driven by the decisions of a board of advisors and its pre-decided key guidelines.

Pointing to the possible paths forward, I align with Scotini’s call for the necessity of broadening the framework in which exhibition analysis is carried out. The path forward in exploring the topic of food representation in art spaces cannot only strictly analyze curatorial decisions and artworks, disregarding the process of production of the space itself, from the moment that production and consumption are inseparable in art as much as in agriculture.

To this end, Scotini’s most poignant reflection guides the theoretical and practical implications and opportunities for future research in the field of relational, ecological art. His questioning revolves around both the genesis and legacy of these cultural events: what do exhibitions spaces and events leave behind them once their performance ends? Are they enslaved to the market politics of window display or do they also contribute to activate spaces for research? (p. 26). In these times of crisis, maybe we already hold the answers to many of our questions, and what is more important right now is to put that knowledge into practice. Performing an ecological awareness can look like striving for biodiversity on land and on the plate, as much as for diversity of representation in a museum board, and in exhibitions visitors. The path forward must carry a radical attitude of cooperative inquiry.

Within the curatorial practice, sensible implications follow the example of relational art and focus on the engagement of the local surrounding community. Efforts should start from the cultivation of an aesthetic sensitivity in children through programs that are specifically designed for them. Stemming from Relational Aesthetics and performative curating, another effective approach entails diversifying the set of museum activities. They can revolve around an exhibition theme and range from residences, to festivals, and art workshops. Finally, the museum as a place for gathering and research between local communities, artistic practitioners, and academia is a theoretical and practical area still largely unexplored. One brilliant example of this has been the 2023 Land, Body, Ecologies Festival held by the Wellcome Collection in London. But that is perhaps a topic for further research.

In a last closing remark, I recall the need for leveling unhelpful hierarchies in our way of perceiving the world. In that process, it is necessary to reclaim people’s art as the “illumination of a shared community” (

Kuehn 2005, p. 205). Similarly to Perullo’s claim of leveling art to the level of cooking (

Perullo 2018, p. 191), Scotini proposes to trace back art to the level of any other job (

Scotini 2021, p. 17). In other words: we must make room for art and food as our everyday source of relating and healing.