1. Add-On Value Brought by Publication Bans: Senki and “The Crab Cannery Ship”

The proletarian cultural movement began in 1921 with the release of the first issue of the literary magazine Tanemakuhito (The Sower). Another magazine called Bungei sensen (Literary Arts Front) became the center of the movement in 1924, and in 1925 the Japan Federation of Literary Arts was formed. This period–from the 1920s until the destruction of the Japan Federation of Proletarian Culture (KOPF) in 1934–represented the peak of the proletarian cultural movement in interwar Japan. One of the most preeminent magazines of this period was Senki (Battle Flag). Senki was launched in March 1928, when the Japan Proletarian Art League and the Union of Avant-garde Artists jointly formed the NAPF (All-Japan Federation of Proletarian Arts), merging their journals, Puroretaria geijutsu (Proletarian Art) and Zen’ei (Vanguard).

Senki was published until May 1930, when a police raid and mass arrests led to the dissolution of the editorial organization. Below is the circulation data of

Senki until just before the mass arrests (

Table 1).

Norma Field and Heather Bowen-Struyk write that proletarian journals like

Senki were dangerous to possess and as a result were passed around from reader to reader, meaning that “actual readership was even higher than circulation numbers indicate” (

Field and Bowen-Struyk 2016, p. 4). And yet, the overall trend of

Senki's intended and actual publication is roughly comparable to the circulation of

Chūō kōron after 1927, when sales began to lag because of the growing popularity of the newly emerging cheap paperback book format (

enpon) (

Shimbun zasshi-sha toku-hi chōsa 1979).

2The September 1928 issue of Chūō kōron indicates, for instance, that the president had been replaced, and change in editorial direction was conducted by the newly appointed president, Shimanaka Yūsaku. Before Shimanaka’s tenure, the magazine was an emblem of ‘Taishō Democracy,’ and published work from a number of major liberal intellectuals, including Yoshino Sakuzō; but Shimanaka employed many writers from the proletarian Senki in order to compete with Kaizō, which published many writers from Bungei sensen. In describing Chūō kōron’s editorial strategy during the period, which aimed to repel the challenge of Kaizō and seize the initiative, then-editor Amamiya Yōzō stated that “The owner, Shimanaka, approached Marxist thought like it was in vogue, like it could be material for the magazine alongside cinema and sports,” noting that it was at this time that proletarian writer Kuroshima Denji’s story about the Siberian exodus, “Hyōga” (“Glacier”), planned for inclusion in Chūō kōron’s special issue in January 1929, was banned and the magazine pulled from sale. In a memoir of this time, Amamiya writes:

While reading and proofreading [Kuroshima’s] novel with President Shimanaka, I told him that it might cause problems with the authorities, but he was bullish, and assured me there was nothing to worry about. When we heard that the issue was banned, he was impressed that I had such a keen eye, but I think we just had a different sense of the risks publishing faced at the time. Indeed, after this special New Year’s issue was banned, Former President Asada seemed extremely worried about the economic impact, but Shimanaka believed that it would sell well once we had made the changes the censor required. Although it frayed the nerves of all involved, at the time, editorial work was nothing less than ideological and moral warfare, where defeat meant a publishing ban and victory meant release to the commercial market. So, even if the magazine was fundamentally liberal in orientation, a harder left-wing core formed among us editors.

It should be noted here that in order to form the editorial left wing at

Chūō kōron, and counter rival

Kaizō, Amamiya was drawn to the increasingly successful

Senki, whose circulation had risen to around 20,000, rather than

Bungei sensen, whose circulation was only several thousand. Page space would also be devoted to the writers of

Bungei sensen when they were considered to have commercial value (

Amamiya 1998, p.536). To the editors and publishers of

Chūō kōron, who were trying to rebuild their editorial strategy and business along a leftist line,

Senki’s increase in circulation to more than 20,000 copies was very attractive and seemed to prove the efficacy of the strategy. But with this increase in

Senki circulation came an intensifying frequency of publication and distribution bans, as

Table 1 shows. In conjunction with this data, the “socialist” competition between Chūōkōron-sha and Kaizō-sha, the publishers of

Kaizō, the representative publishing capital of Imperial Japan became visible, leading to a spike in the number of publishers specializing in left-wing books (

Ko 2009,

2010b;

Wada 2022).

3 The terms “left-wing publishers” (sayoku shuppan-sha) and “leftish publishers” (sayoku-teki shuppan-sha) even appeared.

4 Left-wing publishers were “class-based publishers that printed and published books based on the activist tactics of the proletariat,” while leftish publishers were “bourgeois publishers in form and leftish book publishers in content” because they utilized the capitalist distribution network (

Kanroji 1931, p. 348). Kanroji Hachirō writes that the major leftish publishers were Kibōkaku, Dōjinsha, Kyōseikaku, Sōbunkaku, Marx Shobō, Iskura-kaku, Hakuyōsha, Sekaisha, Tetsutōshoin, Ueno Shoten, Nanban Shobō, Nansō Shoin, and Kōbundō. Hakuyōsha was the only “leftish publisher that cannot be trusted”. The reason was simple: its books were never banned. As Kanroji points out, the main competitors of leftish publishers are the bourgeois publishers who are not afraid to commercialize socialism, rather than the left-wing publishers.

For example, there was the fierce competition (

Umeda 1998)

5 between the ‘leftish publishers’ (an edition produced by a coalition led by Iwanami Shoten, and including Kibōkaku, Dōjinsha, Kōbundō, Sōbunkaku) and the ‘bourgeois publishers’ (Kaizō edition) over the publication of the Complete Works of Marx and Engels in 1928, recorded as the “greatest tragedy in the history of

enpon” (

Obi 2007, p. 298). In the end, the Iwanami-led version was defeated and the coalition dismantled, and not a single volume could be published. The enormous losses from the investment in translation, typesetting, advertising, etc., were borne mainly by Iwanami Shigeo, founder of the publisher Iwanami Shoten (

Obi 2007;

Cheon 2003).

6 When publication of the Kaizō edition began, the Special Higher Police, together with the Ministry of Education, conducted a thorough investigation of those who had applied to pre-order books, mainly students and teachers.

7 Based on this information, a blacklist of ‘left-leaning elements’ was compiled, and those on the list were explicitly excluded from being hired as elementary school teachers.

8 At a time when the

Yomiuri newspaper reported a flurry of ‘damage’ caused by ‘legal’ publications circulating in the ‘legal’ market, where the yen production-distribution-consumption system of

enpon operated, there was heightened demand for ‘illegal’ products whose very possession was deemed dangerous, by intellectual readers such as students and teachers.

There was not a rigid or stable distinction between left-wing and leftish publishers, however, because many publications changed their strategies throughout the period and many writers published work in both kinds of outlet. Indeed, the

Senki coterie writers, who were regarded as the base of left-wing publishing, came into the limelight because they moved freely between bourgeois publishing, leftish publishing, and left-wing publishing. In particular, Nakano Shigeharu, who wrote the well-known poem alluding to the Emperor’s assassination, “Ame no furu Shinagawa-eki” (Shinagawa Station in the Rain), and Kobayashi Takiji, who made his debut during this period, were rapidly emerging as talented and popular writers. Kobayashi’s story “Kanikōsen” (The Crab Cannery Ship) was serialized in

Senki in May and June 1929. Of these, the June issue was initially pulled from sale. As demonstrated in

Table 1,

Senki was frequently pulled from sale months starting in November 1928, and the banning of the June 1929 issue could have been easily predicted given the mass arrests and imprisonment of communists and labor activists in the infamous April 16 Incident, which took place during the editing and printing of the issue. But when the issue was released, containing the second half of “The Crab Cannery Ship,” the newspaper

Tōkyō Asahi Shimbun (Tadato Kurahara, “Works and Reviews”, June 17, 1929) and literary journal

Shinchō (Seiichiro Katsumoto, July 1929) published favorable reviews of it, and the general readership responded positively (

Ogasawara 1985;

Shimamura 2008;

Field 2009).

9The stricter the censorship against socialism became, the more manuscript requests were made to NAPF-affiliated writers, and the more revenue was generated from printing books by these authors. Amamiya noted that “the so-called bourgeois literary world was dismayed that

Kaizō and

Chūō kōron were competing so forcefully to publish works by professional writers” (

Amamiya 1998, p. 537). But there was another aspect to this arrangement. Amamiya continues that “Kobayashi Takiji was so pleased by the results from my negotiations to publish his work in

Chūō kōron that he danced for joy,” and when “Kobayashi and his colleague, the equally great proletarian writer Tokunaga Sunao, were too thrilled to speak when they came to collect the manuscript fee, and thanked me later by letter instead” (

Amamiya 1998, p. 539). Of course, it is necessary to take Amamiya’s reflections–recorded so long after the fact–with a grain of salt. However, they speak to the atmosphere that enabled NAPF to embark on a publishing business, and demonstrate its opposition to censorship in order to create a unique brand as the ‘headquarters of left-wing publishing’.

When publishing “The Crab Cannery Ship” in book form, Senki-sha restored all of the

fuseji that had appeared in its original publication in the magazine

Senki (

Toda 2019).

10 Fuseji are censorship marks that made the traces of deletion visible. In this period, editors often ‘voluntarily’ used them to cover expressions that might violate regulations or otherwise put them at risk from authorities. In this way, contrary to the original function of

fuseji, to conceal, they functioned as a formal device to encourage reading comprehension of the concealed material (

Maki 2014, p. 15). In this sense, while

fuseji were a symbol of submission to censorship and the resulting humiliation, they were also a form of resistance to censorship (

Yamamoto 1967;

Ko 2006,

2010a;

Abel 2012;

Maki 2014).

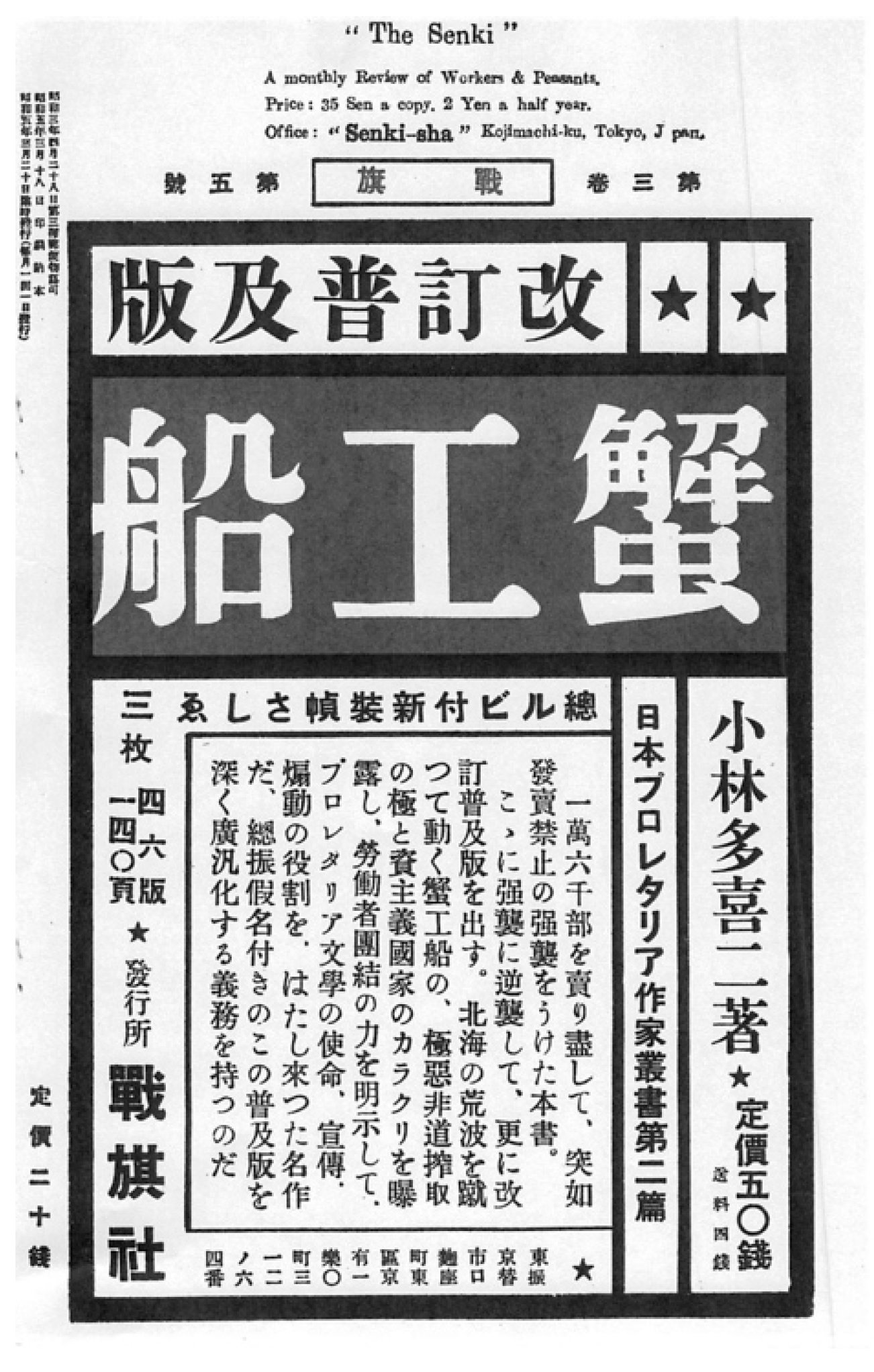

11 Senki-sha’s publishing strategy is clearly shown in the text used in a series of advertisements that appeared in

Senki.

September 1929 issue: Prepare for the book’s inevitable ban! Always pre-order! (Best timing: just before it goes on sale)

October 1929 issue: Defend proletarian publications against censorship! Order directly!

November 1929 issue (Figure 1): The first edition was immediately prohibited from sale.

The first edition was sold out before publication, and a revised edition with a new binding will be issued.

Protect class-based publications from bans! You can be sure of obtaining a copy if you pre-order in person!

December 1929 issue: More editions on the way! The sixth edition is published with the overwhelming support of workers and peasants throughout the country!

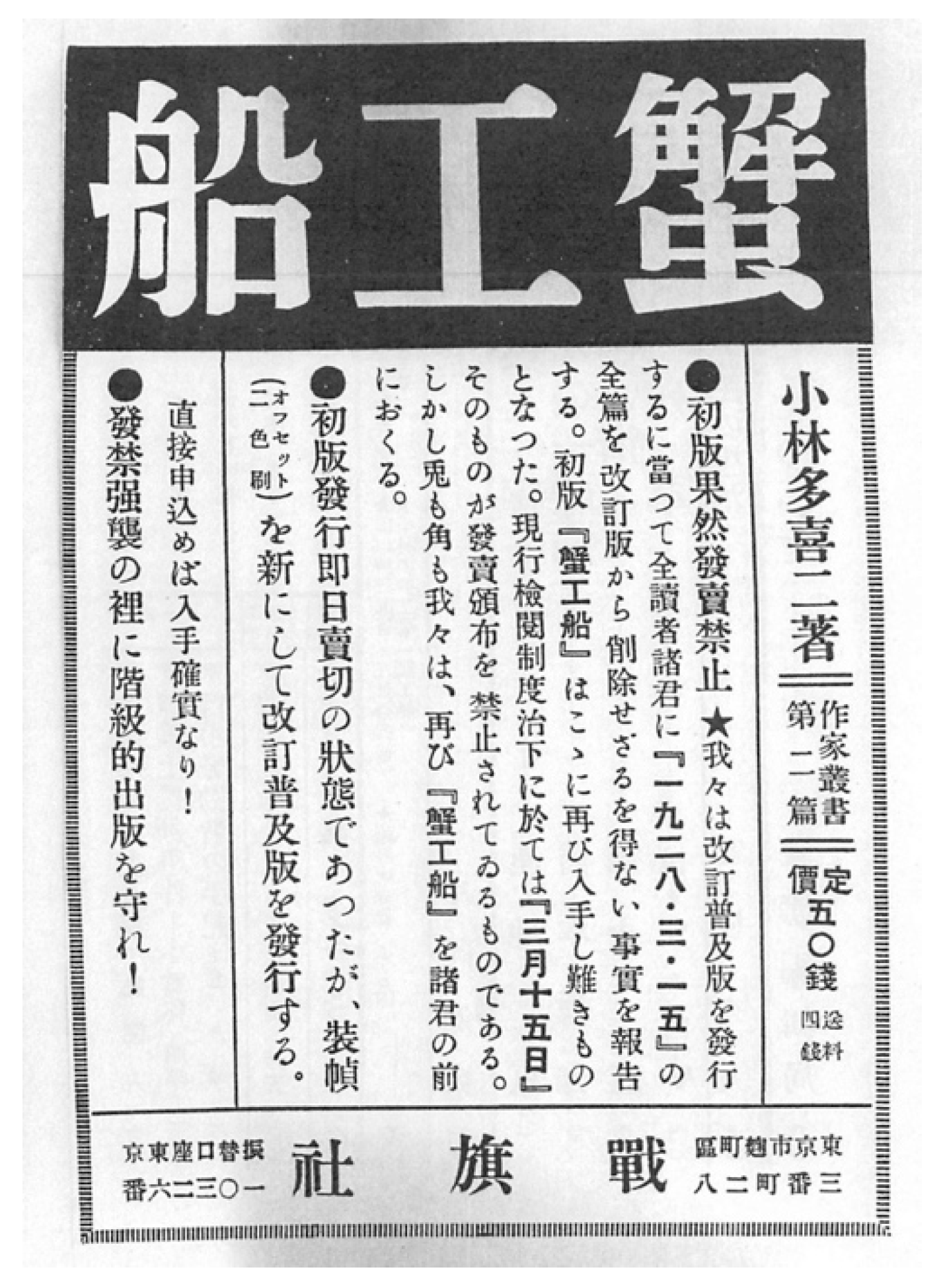

The first edition of

The Crab Cannery Ship, which used few fuseji, was banned on its day of publication. In this edition, the novel was published together with another Kobayashi story, the more closely regulated “15 March 1928”, about the March 15 Incident, a mass-arrest of leftists. As shown in the text of

Figure 1, this story was removed in its entirety from the revised edition. However, the revised edition published in accordance with the stipulations described in advertisements (with some phrases covered with

fuseji) was also immediately banned. In March 1930, a revised and popularized edition was published with more

fuseji, as well as “full-text

rubi,” or phonetic kana over the kanji, making the text much more friendly to people with low literacy skills. The advertisement in

Figure 2 reports that a total of 16,000 copies were issued. The successive bans attracted so much attention that there was a rush of orders; so many, in fact, that there were conflicts among the distributors over how copies would be allocated. The following testimonies from 1931 show how sales-sensitive booksellers reacted to the publication of the book

The Crab Cannery Ship:

It didn’t matter whether the price is low or high. I was told by a Tokyo bookstore that when The Crab Cannery Ship first came out, they thought it was going to be banned, so they kept it in the back of their shop, in storage, instead of selling it. This is because there was a sense that such a book will inevitably be able to go back on sale.

The strategy of the newly formed publishing house, Senki-sha, was to visualize its opposition to censorship and government power; in other words, to acquire the added value of being banned, and capitalize on the ‘illegal’ label. It was a movement for capital acquisition, not only an ideological movement. Therefore, Senki-sha’s position cannot be ascertained by merely foregrounding the damage of severe censorship to its medium and the ideas inscribed therein. Indeed, although

Senki was closely surveilled and aggressively censored, it remained nonetheless highly culturally and politically influential. In the remainder of this essay, I will focus on the distribution of socialist magazines and books that moved between the boundaries of ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ definitions set by the Imperial power in the 1930s. I aim to consider the term ‘illegal’ and the process of capital generation related to it. This capital generation abounded in the pages of magazines such as

Senki, which both the publishing police and the “Special Higher Police” or Tokkō, classified as ultra-left wing and subjected to special vigilance. I will also discuss how this period coincided with the discovery of the colonial publishing market by imperial publishing capital and the commodification of socialism, and explore how leftist publishing engaged in this restructuring of the publishing market.

12 2. Senki and Capitalizing on ‘Illegal’ Goods

Amidst increasingly punitive and extensive censorship, how was Senki-sha able to ensure the mass distribution of banned books, with customers even openly purchasing these ‘illegal’ commodities through direct order? Was it the incompetence of the Imperial authorities, or did Senki-sha alone find some way to avoid the pressures of the times, which included significant factors such as the amendment of the Peace Preservation Law, and the subsequent March 15 Incident and April 16 Incident?

13 Unlike the March 15 incident, when the general press was able to stage a performance-like media event (

Okudaira 2006, p. 110), by competitively reporting the mass arrest of 3400 people nationwide, the April 16 incident in 1929 was a pinpoint attack, recorded as an incident that demonstrated the expanded influence and power of the Tokkō (

Ogino 1984, p. 213). In the wake of the March 15 incident, at the beginning of April, a fund of 2 million yen was allocated for the expansion of the Police Affairs Bureau, mainly for the Special Higher Police Department and the Book Department. The sudden expansion of the budget was not a request from the administrative level of the Home Ministry, but rather a directive from “higher up,” (

Ogino 1984, p. 171) and those in charge had difficulty fully executing the newly swollen budget. For example, Tsuchiya Shōzō, then the head of the Book Department, said, “The Director [of the Police Affairs Bureau] called me and told me to double the budget of the Book Department, but it was not easy. […] Ultimately, we doubled the budget by increasing the number of clerks and censors on the payroll, and by devising and publishing circulars and other internal reports” (

Tsuchiya 1967, p. 50).

Through this process, the

Shuppan keisatsu hō (Publication Police Reports) were published and the number of personnel in the Book Department was expanded from 24 in 1927 to 61 in 1929. In addition, the monthly internal publications, detailing censorship activities, procedures and policies were also launched to help Tokkō chew through its budget. Other materials were compiled six times a year for the education of Tokkō officials, and various reference books were also published. The content of the magazines and books published by the Book Department and the Tokkō with their expanded budget was largely an analysis of trends in arrests of socialists and censorship statistics. The sharp increase in the number of special investigators at this time shows the same curve as

Table 1, on the rapid growth in

Senki sales; in October 1927, there were 4401 special inspectors, which almost doubled to 8043 in October 1929 (

Shakai undō no jōkyō 1971).

14 This was also due to the increased budget of the Police Affairs Bureau, and the sharp increase in the number of bans-from 216 cases in 1927 to 935 cases in 1929-under the designation of the Publication Law and the Law of the Temporary Control of Seditious Documents, especially those related to the ‘public peace and order’ (

Yui 1985, p. 58).

Along with the increase in the budget, surveillance of Koreans was also expanded. At the direction of the Home Ministry, the Tokkō began to maintain a list of all the approximately 20,000 Koreans living in Japan, and once or twice a month conducted door-to-door check-ins and nighttime house-to-house searches. Furthermore, in order to prevent the movement of Koreans into the interior of Japan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also focused its efforts on countermeasures against ‘malcontent’ Koreans, such as mobile police units, coastal patrols, and language classes. The stated reason was that “overseas Korean malcontent groups are plotting with left-leaning Koreans in Japan’s interior to accomplish their anti-social plans in anticipation of the Imperial Enthronement Ceremony.”

15 The discourse of the ruling power that initiated the March 15 and April 16 incidents linked ‘socialism’ and ‘Korean malcontents’ through the medium of expressions such as ‘disrespect for the Emperor’ and ‘high treason’. In the September 1928 issue of

Senki, both “Through the Steel Bars” (by anonymous Taka[XX] Tarō in Nagoya Prison) and “Deported” by Yi Puk-man appeared under the issue’s special theme of “Deported and Incarcerated Comrades” in relation to the March 15 Incident. In his article, Yi Puk-man asks, “What ‘crime’ have I committed that they would persecute me so relentlessly?” Thus,

Senki was a venue where ‘public enemies’ as defined by the Tanaka cabinet at the time came into contact with each other.

Tsuboi Shigeji, who worked in

Senki’s management department and was directly involved in financial matters during the magazine’s period of rapid growth, gave the following account: “

Senki is banned from publication every month. Not only that, it is also banned from being released before it is published and delivered to distributors, and the reality is that the censor’s minions take all the copies. If

Senki were a bourgeois magazine that only pursued profit, we would simply cease publication because there is no opportunity to make money”. He continued that, for proletarian magazines, “Bans and seizures are fatal, rather than a lack of profit. […] [T]herefore, even if bourgeois laws banned the release of the magazine, we devised methods to prevent it from being seized by the authorities, and employed management methods particular to proletarian magazines for the magazine’s economic defense.”

16 Tsuboi revealed that Senki-sha utilized two distribution methods, a ‘bourgeois’ distribution network (through book shops) and a direct distribution network (though local

Senki branch offices).

A brief article entitled “Appeal to All Readers” published in

Senki, shows that in the early years of the magazine’s existence, when it was still a legally published magazine, it actively sought to utilize the `bourgeois’ distribution network. This Appeal, from the September 1928 issue, reported bans on the magazine’s release, the detention and arrest of NAPF officials who published it, and the forced search of NAPF headquarters on August 7th, among other things. The Appeal concluded, “If you find any bookstores that do not stock this magazine, please ask them to order it from the major sales outlets as soon as possible. Posters advertising the magazine should also be placed in bookstores and other locations throughout the country.”

17In order to solve the problem of increased magazine production costs and defray the risk associated with publishing a left-wing magazine, Senki-sha borrowed (1) The distribution and consumption channels of ‘bourgeois publications’ that used large distributors (such as Tōkyō-dō) and general-interest bookstores, (2) The distribution channels of leftish publications that operated their own membership system, and (3) Direct distribution through local Senki offices and reading groups, while repeatedly emphasizing the challenges of censorship, suppression and publication bans in the magazine’s pages to drum up support and establish their brand. As can be seen in Tsuboi’s statement above, Senki owed its success in part to the added value of it being banned, and a unique distribution network was devised based on (3) direct distribution, distinct from the production, distribution and consumption system of (1) bourgeois publishing and publishing capital.

Incidentally, connecting the distribution scheme with the question of content reveals an interesting structure. First, let us note that

Senki was launched in 1928, at the peak of the

enpon boom, and that until early 1930, when the magazine experienced dramatic growth, print capitalists were engaged in a fierce competition to capitalize on ‘socialist’ commodities. Who provided the content for the ‘socialist’ commodities that fed the ‘bourgeois’ press? An answer to this question occurred in 1930–1931. The anthology

Senki Sanjyūroku-jin shū (Thirty-Six War Flags 1930), which contained many ‘illegal’ pieces, appeared on the publishing market as a collaboration between Kaizō-sha and Senki-sha (

Eguchi and Yamaji 1930). The reason why the NAPF entered a joint venture with the Kaizō-sha rather than just using its own publishing organization, Senki-sha, was outlined in the March 1931 issue of the magazine

Nappu (the theoretical organ of the NAPF, published by Senki-sha).

Kaizō-sha co-published the anthology Thirty-Six War Flags. […] Major works which would have served to represent each author were not included, (because permission to publish the works published by Senki-sha was not granted). The book was edited to cover the author’s most recent works. We can assure readers that each of the thirty-six pieces here are representative of their authors’ best work. […] The reader might wonder what the purpose of publishing this anthology was. As Eguchi has stated in his preface, there were many class casualties among our comrades in 1930. This publication is to provide material support to their families. All royalties will be sent to their needy families.

Kiji Yamaji, “Introducing the New Publication Thirty-Six War Flags”

As mentioned previously, high-profile members of the NAPF, including Kobayashi Takiji, Nakano Shigeharu, Hayashi Fusao, Tsuboi Shigeji, and Murayama Tomoyoshi, were imprisoned for more than a year following the mass arrests of Senki-sha workers and collaborators in May 1930. Many of the writers listed in

Thirty-Six War Flags were also included there. As it is emphasized that only their representative works were published by

Senki itself, the

Japanese Proletarian Writers’ Series published by Senki-sha the same year included “Kanikōsen” (The Crab Cannery Ship, by Kobayashi Takiji), “Tetsu no hanashi” (The Story of Tetsu, by Nakano Shigeharu), and “Taiyō no nai machi” (The Town Without Sun, by Tokunaga Sunao), among others, as

Senki’s representative works. These books were “representative of the

Senki authors, and did not often appear in remainder sales at the night market in Jinbōchō [a major book selling neighborhood in east Tōkyō], because they have sold a considerable number of copies already and should continue to sell well” (

Kanroji 1931, p. 240).

Although Senki-sha’s advertisement for the Kaizō-sha co-produced

Thirty-Six War Flags is explicit that it does not contain “representative” works by

Senki writers, the inclusion of such works in Senki-sha’s own book series is particularly emphasized. It thus becomes clear that works by the same authors were simultaneously marketed through the distribution routes of ‘bourgeois publishing’ and ‘left-wing publishing’. After the 1930 Senki-sha incident, it became impossible to sell the company’s publications in bookstores. Therefore, they attempted to use the legal distribution system to generate income from royalties, although there was significant internal protest against such a move. For example, the editors even adopted a resolution that

Senki should increase its circulation figures “in order to attract readers to proletarian publications,” because “thanks to their inclusion of work of proletarian writers, bourgeois magazines’ sales figures already bolster their sales figures by ensnaring readers who originally sought proletarian publications.”

18From the very beginning of its publication,

Senki set a goal of securing 20,000 readers. However, while attempting to diversify their risk in various ways, they began to aim for the same one million readers of the magazine

Kingu (King, published by Kōdansha). The “mass = 1 million readers” calculation had already appeared in debates about the uses of popular art between Kurahara Korehito and Nakano Shigeharu, two of NAPF’s leading theorists, which had the effect of raising the profile of the first issue of

Senki (

Shockey 2019).

19 Interestingly, despite the fact that both sides of the debate could not resolve their opposing views, their specific goals for popularization in the debate were identical.

While analyzing this debate, Maeda Ai focuses on the emergence of the concept of ‘masses’ and discusses the discourse which posited the ‘masses’ being ‘enlightened’ by

enpon (inexpensive paperbacks of classic literature, foreign literature and philosophy) and Kōdansha culture. In short: “The new challenge of how to win the ‘masses’ back to the side of proletarian literature and politically ‘enlighten’ them was faced by the proletarian literary movement” (

Maeda 1989, p. 208).

Furthermore, Satō Takumi, scholar of

Kingu magazine, analyzed the efforts of the

Senki group to win readers as a “counter-movement that directly challenged the mass public nature of

Kingu.” (

Satō 2002;

Perry 2014)

20 A common point among the discussions of the popularization movement is that they consider the establishment of print capitalism in the same period as chiefly a problem of capital, while the ‘head-on opposition movement’ by the

Senki group and others is considered only as a problem of the agitprop that “opposed bloated bourgeois journalism,” far removed from capital formation (

Maeda 1989, p. 209). From such a perspective, it is impossible to read into the meaning of the statement by Tokunaga Sunao, a star writer produced by

Senki, that “Our

Senki can achieve its economic objectives only by recapturing the common workers who are the readership of

Kingu” (

Tokunaga 1930, p. 244).

To emphasize once again, Senki appeared during the heyday of enpon. Through applying the advertising, publicity, and distribution system of the mass-media magazine Kingu, enpon created a huge publishing phenomenon thanks to mass book production, low-cost sales policies, loyalty programs, advertising with a radical and commanding tone, lectures by famous authors for readers, and so on. Senki was also trying to access this market and its capital using similar strategies to enpon publishers. In other words, Senki was not immune to the sphere of influence of print capitalism, which was booming at the time.

While differences in the use of capital acquired in the publishing market should be taken into account, as will be discussed in the next section, the bottom line is that the structural characteristics of the Senki and the Senki-sha book editions, i.e., the publication competition and struggle of the treasonous Senki coterie (NAPF) that advocated overthrowing the Emperor System (Kingu) since the 1927 Thesis, were not a purely ideological movement that developed outside the existing print capital. It is important to be aware that they, too, were internal to the system of print capitalism and, like other commercial magazines such as Kaizō, formed an axis of the capital movement that dreamed of recapturing the masses, the readers of Kingu.

Of course, the magazine Senki and the publisher Senki-sha also produced books through collaboration with paper producers, printers and bookbinders, and conducted business not only with book distributors and bookstores, but also with workers and farmers who were members of their direct distribution network through the medium of yen. Their agitprop activities were based on the collection of this yen; the collection, in other words, of capital.

3. Senki as a Catalog of ‘Illegal’ Commodities

Around the end of 1928 (November 1928, December 1928, and February 1929 issues), when

Senki was continually pulled from circulation, the marketing mottos “Become a reader yourself” and “Expand the reader distribution network throughout the nation” appeared repeatedly in the magazine’s pages. The ‘nation,’ included Imperial Japan’s colonies such as “Chōsen [Korea], Taiwan, and other areas,” where “Senki’s publication was XX [

fuseji concealing the word ‘banned’] before it is issued every month” (March 1929). The word ‘Chōsen’ appeared in a variety of ways in

Senki. From the first issue (May 1928), three articles by Yi Puk-man (“The Past and Present of the Korean Proletarian Movement (2),” “On the Occasion of Welcoming May Day,” and “Deported”) and “Our Day Is Near” by Yi Byung-ch’an appeared. In addition, “The Truth of the Clash in Kawasaki” (July 1929), which dealt with an armed clash between Korean workers in Kawasaki, an industrial center outside Tōkyō, was written by Kim Tu-yong, the Chair of the Central Executive Committee of the Federation of Trade Unions of Zainichi Koreans in Japan. From the end of 1929, he took the lead in dismantling the Korean workers’ organizations on the mainland and organizing them under the umbrella of the Japan Trade Union National Council (or Zenkyō).

21 The structure of

Senki (such as the placement of the table of contents) and the information conveyed by Yi Puk-man and Kim Tu-yong in their writings were perceived as representing the voices of “comrades and compatriots” from “the whole country and the Korean provinces” of Japan. For example, “Floods in Korea: Help Our Korean Brothers in Disaster!” (Pak Wang-yang, September 1928), denounced contemporary relief movements, asserting they were impossible inside Korea, because of the prohibition of relief donations in the affected area, Kunsan, and urged “Dear Japanese Comrades,” to “send relief funds” to directly their “comrades in white coats!” The letter contained instructions to address all remittances to Senki-sha.

One of the reasons for the Tokkō’s intensive pursuit of

Senki’s readership organization and network was to reveal the relationship between the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) and the NAPF.

22 Senki published statements in support of the JCP, and its offices were used as operations and editorial spaces for

the Second Musansha Newspaper (legal from December 1929), the

Agricultural Labor League and the

Musansha Youth Newspaper; all published by a Senki-sha bureau dedicated to rebuilding the JCP. It also became problematic because it was acting as a proxy for the solicitation of funds for organizations that had come to the attention of the Tokkō, such as the Defense Fund for the

Musansha Newspaper and the Liberation Movement Victims Relief Society.

During this time, Senki was a kind of catalog for various ‘illegal’ goods and ‘illegal’ fund solicitation. All purchases required payment in advance. When the Liberation Movement Victims Relief Society sold hand towels (advertised in the August 1928 issue, 15 sen per towel plus postage), the magazine announced, “We have received inquiries from Taiwan, Korea, Manchuria, and even the U.S., but we are still unable to ship many orders because they sold out so quickly” (September 1928). ‘Lenin’ was also one of the magazine’s main commodities. For example, a bust of Lenin was introduced as a fundraising item in the same issue for 75 sen. The same bust was also advertised in the Musansha Newspaper Club for 80 sen. Large portraits of Lenin (“Brighten up your rooms, comrades, and support the relief society!” August 1929 issue) and other items frequently appeared as fundraising items. Senki-sha itself sometimes developed commodities and sold them. Among these were a commemorative photograph of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party Founding Convention (February 1929 issue, 20 sen per copy plus postage), which was sold to mark the fact that the audience protested after speeches were canceled by the Tokkō, and other moments where ‘illegality’ was staged. The advertisement for the photo sale was placed at the end of the article reporting on the convention, and above the advertisement was written, “A living example of the dialectical struggle to attain legal status by using and subverting ‘legality’”. In other words, the boundary between ‘illegality’ and ‘legality’ was not clear, and the oppressed could strategically stage their ‘illegality’.

Above all, Senki-sha was engaged in securing direct funding. In February 1929, as

Senki was hit with recurring sales bans, the magazine published an article titled “How to Organize Local

Senki Branch Offices!” in which the company presented a concrete proposal for the establishment of branch offices and the formation of a readers’ association. The price for purchasing

Senki directly, at a bookstore, or through a readers’ group or

Senki branch office would be 35 sen per copy. The more times

Senki was banned, the more emphasis was placed on the phrase, “If the readers of bourgeois magazines are mere consumers of commodities, the only source of revenue for proletarian magazines is the magazine fee paid in advance to the branch offices” (

Tsuboi 1930, p. 198).

In May 1930, the Senki-sha mass arrests led to the seizure of the branch office directory and the complete destruction of the organizational network the publisher constructed. Until this point, the Tokkō had no grasp of the entire organization of Senki-sha, and had to rely on publicly available information to conduct its investigations. Immediately prior to the mass arrests, the

Tokkō Geppō stated, “The producers of

Senki are becoming more and more cunning day by day. From April, the publishers proclaim the necessity of a fund of 3000 yen. This demand seems to be having the desired effect.”

23 This indicates that the branch offices and reading groups were systematically mobilized for the fund solicitation by

Senki. In other words, the reason why the Tokkō monitored the branch office of

Senki was not simply because it generated 2600 yen in revenue; it was also because the 20,000 readers of

Senki had become material supporters of this ‘illegal’ organization, funding it through round-about channels such as by contributing to the fund to relaunch the

Musansha Newspaper (Japanese Communist Party Reconstruction Movement) and the fund of the Liberation Movement Victims Relief Society (which supported detained comrades and their families).

An increase in

Senki’s sales meant an increase in the number of branch offices, and an increase in branches meant an increase in the number of ‘mass’ readers, including workers, peasants, and others. The names of purchasers of all ‘illegal commodities’ appearing in the pages of

Senki include many Koreans. In addition, a few unknown Koreans of a different class from Kim Tu-yong and Yi Puk-man, who conveyed socialist theory and the situation of the struggle in the interior in Japanese, appear in

Senki, although in small numbers. In the “Readers’ Room” section (January 1930 issue), a Korean worker wrote that it took him “two and a half days” to write a single postcard because “I am not a learned man”. This Korean, who said he had no money and could not go to his mother’s funeral, concluded his missive with determination, “I will defend

Senki even if I lose my head”. In those days, ‘defending’

Senki meant nothing more than expressing one’s intention to send funds.

24Immediately after being banned seven times over the course of a year, the editorial board of Senki published “On the Writing of Letters–An Appeal to All Readers” (November 1929). It is a reminder of the lack of efforts towards popularizing the magazine up to this point, and an invitation for more submissions from readers. The number of pages devoted to readers’ comments increased from the end of 1929 to the beginning of 1930. Many readers began to request the addition of rubi pronunciation marks and the elimination of difficult characters and expressions. For example, “‘The Crab Cannery Ship’ is a powerful work, but it is a little complicated. I think it would be better if it were simpler. We couldn’t quite follow it”. (letter from the Kakuda Printing Company Youth Laborer Group, July 1929). Later, Kobayashi Takiji, the author of the story, published “Ginkō no hanashi” (Bank Story, April 1930 issue), a very simple narrative with almost no kanji characters. Thus, in order to withstand the financial hit that the sales ban caused, which became more severe around 1930, Senki’s strategy of popularization was accelerated, and its sales circulation thus exceeded 20,000 copies. Then, in early 1930, Senki the mass-audience magazine was born in the process of staging a joint struggle with the branch offices and reader-comrades over the sales ban, albeit for a short period of time. The aforementioned top theorists of the Senki school (see Nakano and Kurahara’s debate on popularization) were unable to present an alternative to this strategy. In the end, the greatest cause of Senki’s evolution into a mass-audience magazine was the sales ban and the continued suppression by the Tokkō.

4. Uri tongmu (Our Comrades) and the Colonial Book Market

At the end of 1931, when the pressures faced by the Senki coterie were becoming increasingly serious, the Japan Proletarian Cultural Federation (KOPF) was organized, and its journal Puroretaria bunka (Proletarian Culture) was launched. The KOPF launched Hataraku fujin (Working Woman) in January 1932, Taishū no tomo (The People’s Friend) in February 1932, and Chīsai dōshi (Small Comrades) for children in March 1932. Specific left-wing magazines targeted different audiences, such as women, workers, and children; and sales methods and reader organizations of these magazines followed those of Senki.

The Tokkō paid close attention not only to the how funding for Senki-sha and the NAPF was collected and managed, but also to their sources. Even in its heyday in the 1930s,

Senki was in poor financial condition, and the NAPF was aware of this.

25 Of particular interest to the Tokkō was the role of

Senki and the NAPF as a source of funds for the JCP as an extra-Party organization. According to reports from the Tokkō, communication between the Party and the Comintern had been cut off since the April 16 Incident. As a result, the Party needed a financial boost for its campaigns, and “those who were sympathetic were divided into groups such as the NAPF, doctors, students, laborers, journalists, and so on, and representatives from each group were asked to solicit contributions”. Those in charge of solicitation were told that “True comrades would be told that the money was for Party activities, while others would be told they would be donating to relief funds, newspaper funds and so on.”

26Many of the items published in and sold through

Senki were related to the relief funds and

Mushin (a newspaper for the unemployed). More than half of the income recorded in the “Survey of Income from the JCP Activity Fund” from July 1929 to January 1930, prepared by the Tokkō, was secured through the NAPF (from August 1929 to January 1930).

27 Significantly, the increase in donations to the NAPF was proportional to the increase in sales fees for

Senki. Therefore, the Tokkō was more interested in the funds raised through the ‘joint struggle’ with the branch office and community of readers staged on the magazine’s front page than in the income from

Senki sales. The ‘masses’ organized through the medium of

Senki were regarded as material supporters or agents for the reconstruction of the JCP. However, it cannot be said that all readers were aware of how the yen they sent to

Senki were used. Chōsen (Korea), a member of the ‘community of readers,’ was no exception.

Why would the KOPF publish a Hangul magazine, Uri tongmu (Our Comrades), at a time when reorganization was still underway? In 1928, the Fourth Congress of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profintern) adopted a thesis forcing colonial workers to join the trade union of their country of residence. In August of the same year, the Secretariat of the Comintern also reaffirmed the ‘one country, one party’ principle. In the interior of Japan, the dismantling of the Federation of Trade Unions of Zainichi Koreans in Japan began in earnest around September 1929, with the aforementioned Kim Tu-yong in overall charge of the task. In October 1931, the Japanese General Bureau of the Korean Communist Party and the Japanese headquarters of the Kōrai Communist Youth Association (a Korean youth group active during the Japanese occupation) published a joint statement in a Japanese Communist Party organ, the newspaper Sekki (Red Flag), and the KOPF became an organization under the Japanese Communist Party umbrella. The Chōsen Council was formed with KOPF and Dōshi-sha members such as Kim Tu-yong and Yi Puk-man as its core members. The instructions given to them by the KOPF were to “eliminate the national language of the imperialist state and make the mother tongue and national language the basis of creative practice” (5th Congress, 11–13 May 1932). As part of this policy, Uri tongmu was launched.

Let us now turn our attention to a Japanese-language advertisement in the April 1932 issue of the KOPF journal

Proletarian Culture28 which advertises the first issue of

Uri tongmu.

Dear all workers, peasants, and working masses across the country! Uri tongmu, a Korean-language magazine for all Korean workers who cannot read Japanese, will finally be launched in the coming May! […] In order to defend the publications of the Japan Federation of Proletarian Culture against the violent repression and interference of the ruling class and to protect Uri tongmu as your own, Japanese workers, peasants and Korean workers in Japan must become direct readers. Also, you should encourage as many Korean colleagues in your factories and workplaces to read this magazine as possible, so that the proletariat in Japan and Korea can form a revolutionary coalition. […] Even if it is only one or two sen, give generously. Please send funds to this magazine from your factories, workplaces, and farming villages. And please remember to order the magazine with advance payment, to protect the magazine.

Let us grow

Uri tongmu with a sense of class duty. Only then will it have a readership network like a spider’s web throughout the nation’s workplaces of Korean laborers, and the financial basis for publishing the magazine will be solidified. […] Let it rain 200 yen for the publication fund!

29

If we replace the mention of the title Uri tongmu with Senki in the above quotation, we can see exactly the same structure as the advertisement examined in the previous section. Just as Korean readers who could not master the Japanese language as they wished sent funds to protect Senki, the ad urges “Japanese workers and peasants” who do not understand Korean to send funds to “become direct readers” and subscribe to the magazine every month so that “the proletariat of Japan and Korea can form a revolutionary coalition,” even if they do not understand the magazine’s contents. The ad also emphasizes that a network of readers of Uri tongmu should be built in all workplaces of Korean laborers.

At this time, organizing or joining a network of readers of the KOPF’s Uri tongmu or distributing the magazine was itself (even more than the network of readers of Senki and NAPF) considered an affiliated organization and source of funds for the JCP, and could be punished. The reason is that since the 1930s, such activities had been criminalized. As a result, the Tokkō began to investigate Korean residents in Japan. First, the Special Higher Police targeted the Zenkyō, which had targeted the Federation of Trade Unions of Zainichi Koreans in Japan for investigation. The new criteria for prosecution for ideological reasons, which allowed for prosecution simply if one’s membership in an affiliated organization such as the Japan Proletarian Writers’ League could be proved, gradually began to gain strength. In May 1931, the Supreme Court ruled that defendants could be punished if the police and prosecutors determined that they had contributed to the accomplishment of the Party’s objectives.

Since the dissolution of the Federation of Trade Unions of Zainichi Koreans in Japan, the list of arrests of Zainichi Koreans by the Tokkō shows that the overwhelming majority of the prosecutions were for crimes of contribution to the accomplishment of the Party’s objectives. The majority of those charged with this were suspected of distributing

Senki and

Musansha and organizing reader groups. In addition, many of them are affiliated with the Zenkyō. For example, Kim Mun-jun, who was indicted on 10 October 1930, was charged with the crime of accomplishment of purpose (distribution of

Mushin newspaper, creation and distribution of leaflets), and his affiliation with “persons related to Zenkyō and the JCP” (

Tokkō geppō, October 1930). Of course, those affiliated with

Senki were also eventually charged with the same crime and indicted.

30In 1932, when Uri tongmu was first published, more than one-hundred KOPF officials were punished for association with it, because the KOPF was judged to be an offshoot of the Japanese Communist Party. The building of a readership network for Uri tongmu published by the KOPF, meant the creation of a “a readership network like a spider’s web throughout the nation’s workplaces of Korean laborers” was seen as a JCP auxiliary. Moreover, from the perspective of the KOPF, whose readership network was on the verge of collapse as the intensive crackdown by the Tokkō and the thought prosecutors was in full swing, the potential market of over 200,000 Korean readers must have been appealing. The mission of KOPF’s Uri tongmu and the branch office and community of readers developed by the KOPF, including Yi Puk-man, was to bolster the agency of ‘Korean malcontents’ as it circulated among the 200,000 Koreans and the magazine was distributed. In the “Reports of the Chōsen Council” (Puroretaria Bunka, June/July 1933), criticism, reflections, and future initiatives concerning Uri tongmu are presented in detail.

The KOPF directs the collection of funds through deliveries and the organization of Koreans. The language “overcome the sectarian struggle of the Korean people” is also consistent with the policy of the JCP, which had emphasized that the struggle for colonial independence and class-based proletarian revolutionary struggle could not coexist. On the other hand, in June 1933, when this report was published, major conversions were covered by Japanese-language media, triggered by the conversion of Sano Manabu, who had served as chairman of the JCP (‘conversion’ refers to leftists renouncing their political beliefs, under pressure from Imperial authorities). As symbolized by the torture and murder of Kobayashi Takiji in February of the same year, the repression against the KOPF was becoming more severe by the day. In short, it is possible that the launch of KOPF’s Uri tongmu was an alternative to overcome the limitations of the Japanese ‘illegal commodity’ market, which rapidly atrophied during this period. Uri tongmu should be reconsidered from the perspective of developing a new market for such ‘illegal commodities’.

In the early 1930s, the reorganization of the Imperial publishing market was explored, and the colonial market was discovered. The April 1932 issue of the ‘bourgeois magazine’

Kaizō introduced literary writers from the colonies as its new commodity, including the Korean Chō Kakuchū (Chang Hyŏk-chu), and the April 1932 issue of the left-wing magazine

Puroretaria Bunka (Proletarian Culture) heralded the appearance of a new commodity called

Uri tongmu. Also in the early 1930s, the claim emerged that Imperial colonies, never before consciously considered as independent publishing markets, would make possible “the realization of publishing imperialism”. This text argues that the publishing world was being reformed by the fact that vast inventories of

enpon “are inundating the colonies with a force that rivals the deployment of Japanese troops to Manchuria” (

Minato 1931;

Ko 2012).

31 At the same time that books produced by Imperial Japan’s print capital flowed toward the colonial market as mobile media via rail, in Japan’s interior, ‘Korean malcontents’ became ‘mobile media,’ and arrived at the colonial market in the interior bearing the new commodity

Uri tongmu. In other words,

Uri tongmu symbolizes the realignment of the Zainichi Korean bloc, which was once expected to be the foundation for the reconstruction of the Korean Communist Party, into an organization which served the reconstruction of the

Japanese Communist Party. The market restructuring attempted by leftist print capital in Imperial Japan began at the intersection of two markets, empowered by the illusion of collective resistance to Imperial power, and the illusion that Koreans could become equal Imperial subjects if they entered a ‘community of readers’.

Previous Japanese-language scholarship has tended to beautify cultural movements pursued by Japanese and Koreans around 1930 as solidarity among comrades–intellectual and political movements marked as sacred and above the predations of capital. As demonstrated in this essay, however, the publication and commodification of ‘illegal’ materials had a profound bearing on the movement of capital in the print industry. Furthermore, the struggle for survival waged in print by the Japanese socialist movement in the early 1930s resulted in a major blow to the organizational base and funding for the reconstruction of the Korean Communist Party, which was being advanced by Korean socialists in Japan. This particular chapter within Japan’s cultural history of the late 1920s and early 1930s, the essay claims, should be subject to a degree of critical rethinking and rewriting.

32