Videographic, Musical, and Linguistic Partnerships for Decolonization: Engaging with Place-Based Articulations of Indigenous Identity and Wâhkôhtowin

Abstract

1. Partnerships for Decolonization

Okiskinohamawakanew Daylon, Devon, ekwa Joseph. Kîhtwâm ka-wâpamitin.1

2. Positionality and Methodology

3. Representations of Indigeneity in N’we Jinan Artists’ Videography

4. Linguistic Negotiation of Indigeneity in N’we Jinan Artists’ Lyrics

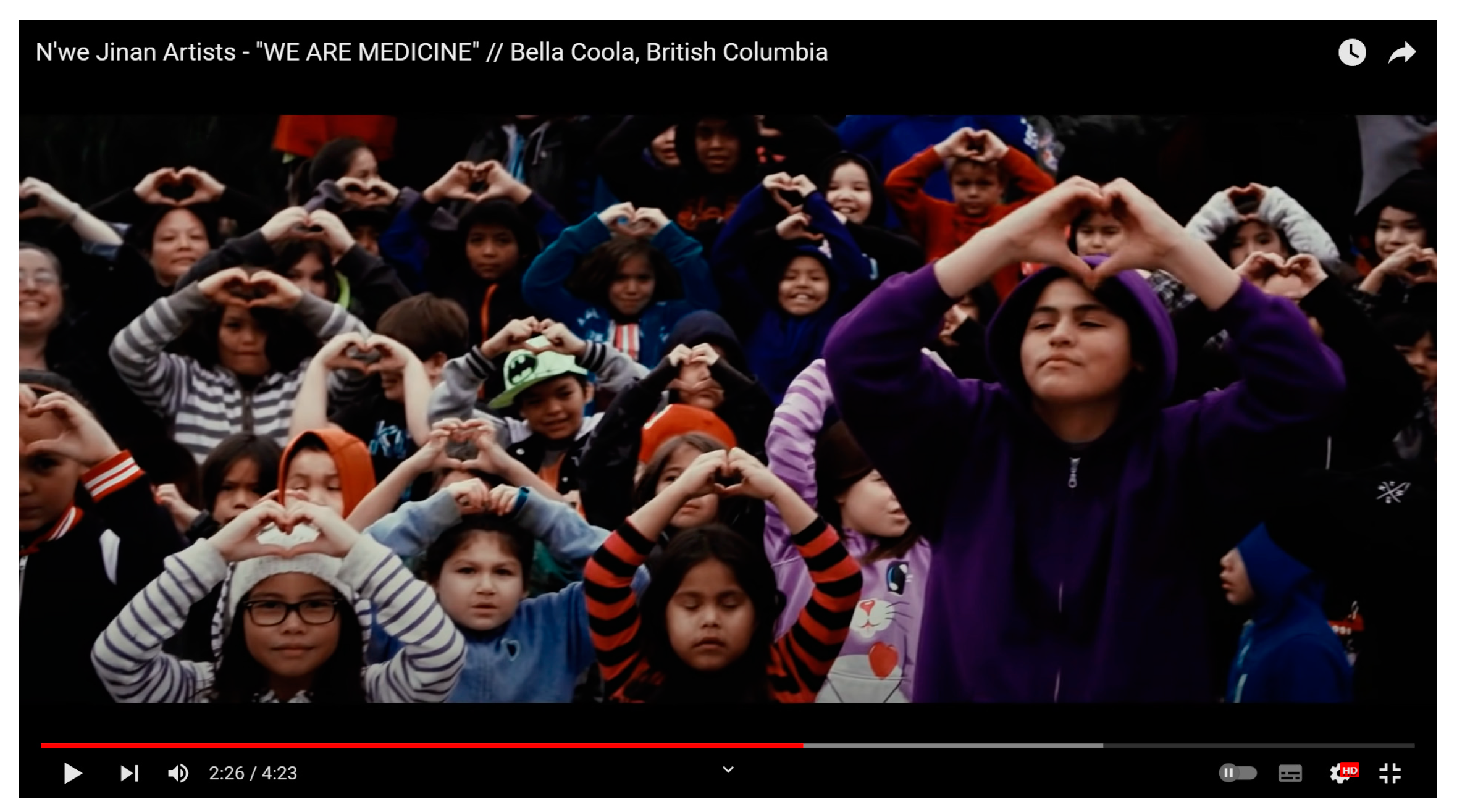

- We, children, are the medicine, the bringers of tradition

- Keepers of the peaceful, sacred life that we’ve been given

- We’re the bridge of two paths, the voice of our spirit

- The forgivers of a nation, we are one voice singing.

5. Connectivity and Access

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | English translation: To Daylon, Devon, and Joseph, who also taught me. We will see you again. With the families’ permission, I am dedicating this current work on decolonization and Indigenization to the young Nêhiyawak Cree men who are no longer with us. |

| 2 | Indigenous, in this article, refers to individuals and groups descended from people—which include First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people—who lived in the country known as Canada before settlers arrived. |

| 3 | The members of N’we Jinan are artists who travel to Indigenous communities. They support youth artist participants in collaborating in writing, performing, recording, and producing original songs (N’we Jinan 2022a). All merchandise profits feed the youth programs (N’we Jinan Artists 2014a). While the offices are located in Tiohtiá:ke (Montreal), the members of the mobile production team conduct their work in Indigenous communities and remotely, so it is useful to view the details provided in each of the YouTube videos to identify the individual N’we Jinan members who assist with the video, music production and mixing, and mastering as well as the community in which the video occurs and the individual N’we Jinan youth artists who participate in the video. |

| 4 | In exploring the videos in this article, I follow Lev Manovich’s considerations of the disruption and redistribution of power embedded in past cultural categories (Manovich 1998) and Sonia Livingstone’s definition of new media as already “familiar technologies” (Livingstone 1999, p. 61). |

| 5 | Future in-text references will refer to this document as the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. Educators are explicitly directed to incorporate this resource into their teaching in Nunavut classrooms. While N’we Jinan has not yet worked with Nunavummiut youth, I incorporate this document here to draw attention to it for its potential in terms of engaging with literature. I advocate for using locally-specific Indigenous resources and frameworks where possible and acknowledge that there are many unique differences between Indigenous cultures even when they share a language, and I also acknowledge from my experience as a teacher in Indigenous communities that sometimes a needed entry point to a text within a teaching context comes from identifying similarities and differences between the culture and language being studied and that of the learners. The Dene Kede Education: A Dene Perspective Kindergarten—Grade 6 explicitly states an impetus to “Recognize similarities and differences between Dene and others” (Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment 1993, p. 5). Similarly, the Inuuqatigiit: The Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective states that “the curriculum [has] something for people of many different backgrounds. We want to celebrate the similarities of all people, rather than differences” (Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment 1996, p. 3). I draw upon these texts because of my first-hand experience using them in Arctic schools. |

| 6 | Future in-text references will refer to this set of documents as the Dene Kede. Educators are explicitly directed to incorporate these resources into their teaching in Northwest Territories classrooms. |

| 7 | Future in-text references will refer to this document as the Inuuqatigiit. Educators are explicitly directed to incorporate this resource into their teaching in Northwest Territories classrooms. |

| 8 | According to (Cree Dictionary Online 2023), wâhkôhtowin means “relationship” or “the state of being related to others”. This, I believe, is a particularly important idea as part of reconciliation in educational contexts so that Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners, educators, instructional leaders, and administrators can walk together. |

| 9 | I have been privileged and honoured to support Nêhiyawak (Cree), Inuit, Inuvialuit, Gwìch’in, and Métis learners in a number of educational roles. I am grateful to each of the people who have supported and continue to support my learning journey through Indigenous languages and cultures both in person and online, formally and informally. This article represents my efforts at “being and becoming a good relative … [through] active and meaningful engagement—relatives aren’t just static roles or states of being, but lived relationships” (Heath Justice 2018, p. 73). The work of N’we Jinan offers learning opportunities for educators like myself who are interested in social justice. Learning about how empowering linguistic and visual articulations of Indigenous identity resist coloniality is an important underpinning to teaching about social justice. |

| 10 | The narratives emerging from contemporary Indigenous, Inuvialuit, and Métis youth require interpretation that acknowledges the ongoing impact of colonialisms. Consciousness of colonialisms enacts an “an entry point into agency” (Tlostanova 2019, p. 165). The term “decolonizing” foregrounds Indigenous ways of knowing and doing (Mullen 2020) and can connect accessible traditional knowledge with potential pedagogical approaches (Thevenin 2022, p. 16). One of the ways in which I attempt to honour the gifts of learning about Indigenous cultures that I have received is through engaging with Indigenous resources and epistemologies (Battiste and Henderson 2000; Battiste et al. 2002; Donald 2021; Tuhiwai Smith 1999). |

| 11 | See also Craig Womack’s (1999, 2005) arguments for cultural specificity in interpreting literary texts and Nassim Balestrini’s (2022) call to research hip-hop artists and their music in ways that are contextualized within their specific location. |

| 12 | According to Janet Loebach et al. (2019), digital storytelling is a narrative methodology (p. 283) that is participatory (p. 284), supports participants in shaping their own narratives (p. 284), encourages creativity (p. 286), and can be captured through cell phone recordings as well as more expensive equipment (p. 294). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | A form of critical pedagogy for educators must be enacted that is cognizant of the impact of racialized and cultural context (Giroux 1992, 1999). It must be agentic, reflective, and reflexive and attend to how linguistic and visual elements enact selfhood and negotiate figured worlds (Holland et al. 1998; Urrieta 2007). Further, language, culture, and media representation require explicit engagement, particularly in the ways in which they disrupt, query, or reinforce experiential themes of survival (Wiggins and Monobe 2017). |

| 15 | N’we Jinan offers rich opportunities for forms of what Giroux (1992) refers to as border crossing. Negotiating border spaces and reflecting upon and engaging in the epistemic disobedience of pluriversality furthers decolonial thinking (Mignolo 2011, p. 63) and has the potential to initiate or further epistemic activism (Behari-Leak 2020, p. 19) as part of a social justice pedagogy. |

| 16 | The N’we Jinan website provides the opportunity for viewers/listeners to download the phonetically spelled Cree lyrics. The phonetic spelling is beneficial in rendering the sounds immediately accessible but can provide a challenge in seeking translation to access meaning via published Cree in language online/textual dictionaries, which tend to employ Standard Roman Orthography (SRO). |

| 17 | The poster Ikpiguhungniq, expressed in the Nattilingmiutut dialect of Inuktitut, represents Respect through the image of a caribou nibbling lichen under a bright Arctic sun. The image suggests the need to respect the cycle of life in the same manner as the caribou, to take only what one needs and to appreciate what is being granted from the land and the lives that give of themselves that people may also be sustained. |

| 18 | The Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit value Ihumamut Akhuurniq, expressed in the Nattilingmiutut dialect of Inuktitut, also explores the value of Strength in an Arctic context. The poster represents Strength through the image of a polar bear gazing off from a small ice floe, an image ever more powerful as the increasing impact of climate change becomes ever more evident in the north. |

References

- Akom, Antwi A. 2009. Critical Hip Hop Pedagogy as a Form of Liberatory Praxis. Equity & Excellence in Education 42: 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Ian. 2003. Introduction. In Blacklines: Contemporary Critical Writing of Indigenous Australians. Edited by Michele Grossman. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Leon. 2006. Analytic Autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35: 373–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker Boy. 2018. Black Magic. YouTube. Uploaded by Baker Boy. July 12. Available online: https://youtu.be/j3_WuuWJ1hw (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Balestrini, Nassim Winnie. 2022. The Cultural Ecology of Alaskan Indigenous Hip Hop: “Ixsixán, Ax Kwáan (I Love You My People)”. Ecozon@: European Journal of Literature, Culture and Environment 13: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Adam J. 2015. ‘A Direct Act of Resurgence, A Direct Act of Sovereignty:’ Reflections on Idle No More, Indigenous Activism, and Canadian Settler Colonialism. Globalizations 12: 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiste, Marie, and James Youngblood Henderson. 2000. Protecting Indigenous Knowledge and Heritage: A Global Challenge. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, Marie, Lynne Bell, and Len M. Findlay. 2002. Decolonizing Education in Canadian Universities: An Interdisciplinary, International, Indigenous Research Project. Canadian Journal of Native Education 26: 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Behari-Leak, Kasturi. 2020. Toward a Borderless, Decolonized, Socially Just, and Inclusive Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Teaching & Learning Inquiry 8: 4–23. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/toward-borderless-decolonized-socially-just/docview/2459013933/se-2?accountid=142373 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Bequette, James. W. 2014. Culture-Based Arts Education That Teaches Against the Grain: A Model for Place Specific Material Culture Studies. Studies in Art Education 55: 214–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, Homi. 2015. Remembering Fanon: Self, Psyche and the Colonial Condition. In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory. London: Routledge, pp. 112–23. [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist, Rut Elliot. 2016. Decolonization in Europe: Sami Musician Sofia Jannok Points to Life Beyond Colonialism. Uneven Earth: Tracking Environmental Injustice. November 9. Available online: http://unevenearth.org/2016/11/decolonisation-in-europe/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Carney, Nikita. 2016. All Lives Matter, But So Does Race: Black Lives Matter and the Evolving Role of Social Media. Humanity & Society 40: 180–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton, Charlotte. 2012. Problematising the Role of the White Researcher in Social Justice Research. Ethnography & Education 7: 363–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J. Edward. 2003. If This is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Meredith D. 2019. White Folks’ Work: Digital Allyship Praxis in the #BlackLivesMatter Movement. Social Movement Studies 18: 519–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Kris, and Michael Yellow Bird. 2021. Decolonizing Pathways Towards Integrative Healing in Social Work. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Sandra, and Philip Hiscock. 2009. Hip-Hop in a Post-Insular Community: Hybridity, Local Language, and Authenticity in an Online Newfoundland Rap Group. Journal of English Linguistics 37: 241–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Elizabeth. 2010. “Never Say Die”: An Ethnohistorical Review of Health and Healing in Aklavik, NWT, Canada (edsndl.MANITOBA.oai.mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca.1993.4103). Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, Ashley, and Leilani Sabzalian. 2020. The Urgent Need for Anticolonial Media Literacy. International Journal of Multicultural Education 22: 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree Dictionary Online. 2023. s.v. “Wâhkôhtowin”. Available online: http://www.creedictionary.com/ (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Davis, Camea. 2021. Sampling Poetry, Pedagogy, and Protest to Build Methodology: Critical Poetic Inquiry as Culturally Relevant Method. Qualitative Inquiry 27: 114–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Korne, Haley. 2021. Language Activism: Imaginaries and Strategies of Minority Language Equality. Oslo: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, Dwayne. 2021. We Need a New Story: Walking and the Wâhkôhtowin Imagination. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies 18: 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, Sara Nicole. 2019. Lines, Waves, Contours:(Re) Mapping and Recording Space in Indigenous Sound Art. Public Art Dialogue 9: 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, Paulo, and Donaldo Macedo. 2005. Literacy: Reading the Word and the World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Jo Anne Kleifgen. 2020. Translanguaging and Literacies. Reading Research Quarterly 55: 553–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, Henry A. 1992. Border Crossings: Cultural Workers and the Politics of Education. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, Henry A. 1999. Performing Cultural Studies as a Pedagogical Practice. In Soundbite Culture: The Death of Discourse in a Wired World. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Elizabeth, and Mark Williams. 1998. Raids on the Articulate: Code-Switching, Style-Shifting and Postcolonial Writing. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature 33: 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath Justice, Daniel. 2018. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Juliet. 2017. Critiquing the Critical: The Casualties and Paradoxes of Critical Pedagogy in Music Education. Philosophy of Music Education Review 25: 171–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, Dorothy, William S. Lachicotte, Jr., Debra Skinner, and Carole Cain. 1998. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheon, Linda. 1989. ‘Circling the Downspout of Empire’: Post-Colonialism and Postmodernism. Ariel 20: 149–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Lauren Leigh. 2020. Listening Differently: Youth Self-Actualization Through Critical Hip Hop Literacies. English Teaching: Practice & Critique 19: 269–85. [Google Scholar]

- King, Thomas. 2004. Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial. In Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism. Edited by Cynthia Sugars. Peterborough: Broadview Press, pp. 183–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, Adam J. 2020. ‘Take a Back Seat’: White Music Teachers Engaging Hip-Hop in the Classroom. Research Studies in Music Education 42: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBaron, Michelle, and Janis Sarra, eds. 2018. Changing Our Worlds: Arts as Transformative Practice. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, Sonia. 1999. New Media, New Audiences? New Media & Society 1: 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebach, Janet, Kate Tilleczek, Brent Chaisson, and Brian Sharp. 2019. Keyboard Warriors? Visualising Technology and Well-Being with, for and by Indigenous Youth through Digital Stories. Visual Studies 34: 281–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, Lev. 1998. Database as a Symbolic Form. Available online: http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/167-lev-manovich-all-articles-1991-2007/lev_manovich_all_articles_1992_2007.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Maracle, Lee. 2004. The ‘Post-Colonial’ Imagination. In Unhomely States: Theorizing English Canadian Postcolonialism. Edited by Cynthia Sugars. Peterborough: Broadview Press, pp. 204–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2011. Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto. Transmodernity 1: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, Carol A. 2020. Canadian Indigenous Literature and Art: Decolonizing Education, Culture, and Society. Schöningh: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- N’we Jinan. 2014. About. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/@nwejinan/about (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022a. About. Available online: https://nwejinan.com/about (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022b. Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/nwejinan (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Family of Sites. 2022. Available online: www.nwejinan.com (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022c. Instagram. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/nwejinantv (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022d. iTunes. Available online: https://music.apple.com/ca/artist/nwe-jinan-artists/1049194860 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022e. Soundcloud. Available online: https://soundcloud.com/nwejinan (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022f. Twitter. Available online: https://twitter.com/nwejinan (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan. 2022g. YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/user/nwejinan (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2014a. I Believe. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. November 4. Available online: https://youtu.be/3RFT1Pu0e28 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2014b. N’we Jinan. YouTube. Uploaded by Notre Home. May 28. Available online: https://youtu.be/3p6Zc9mc9wA (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2015. Creespect. YouTube. Uploaded by CDBaby. November 7. Available online: https://youtu.be/7BddMc6nGJU (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2016a. Home to Me. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. March 18. Available online: https://youtu.be/EgaYz8YWsO8 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2016b. We Are Medicine. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. December 7. Available online: https://youtu.be/VeWqgLLCef0 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2016c. When the Dust Settles. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. September 23. Available online: https://youtu.be/FilF26tdu8w (accessed on 5 March 2023).

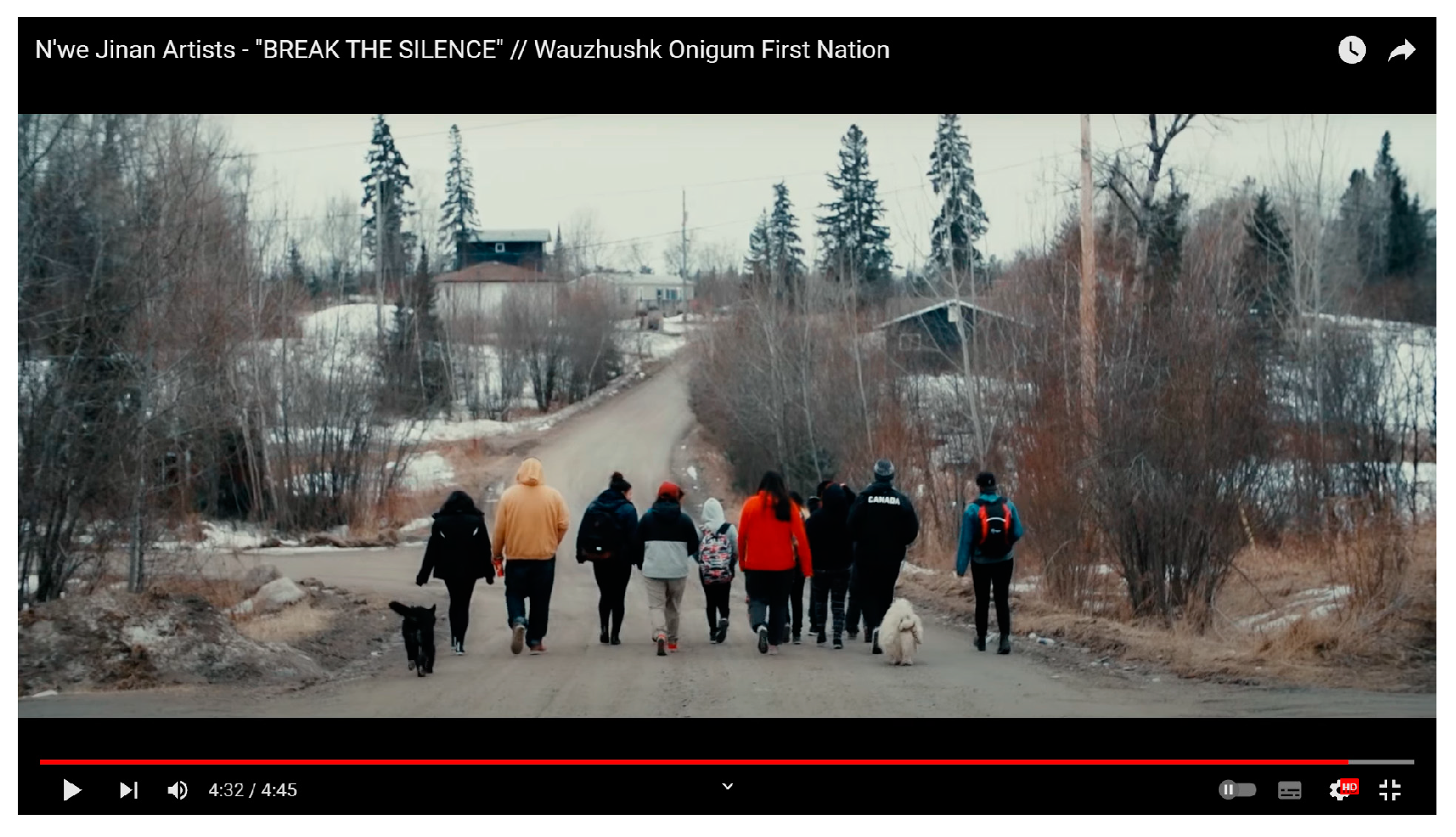

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2017a. Break the Silence. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. April 24. Available online: https://youtu.be/30PS-h6yKvk (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2017b. We Won’t Forget You. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. December 19. Available online: https://youtu.be/u0YYkvIWbng (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2018. The River Flows. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. March 9. Available online: https://youtu.be/N5D-1TyJmSE (accessed on 5 March 2023).

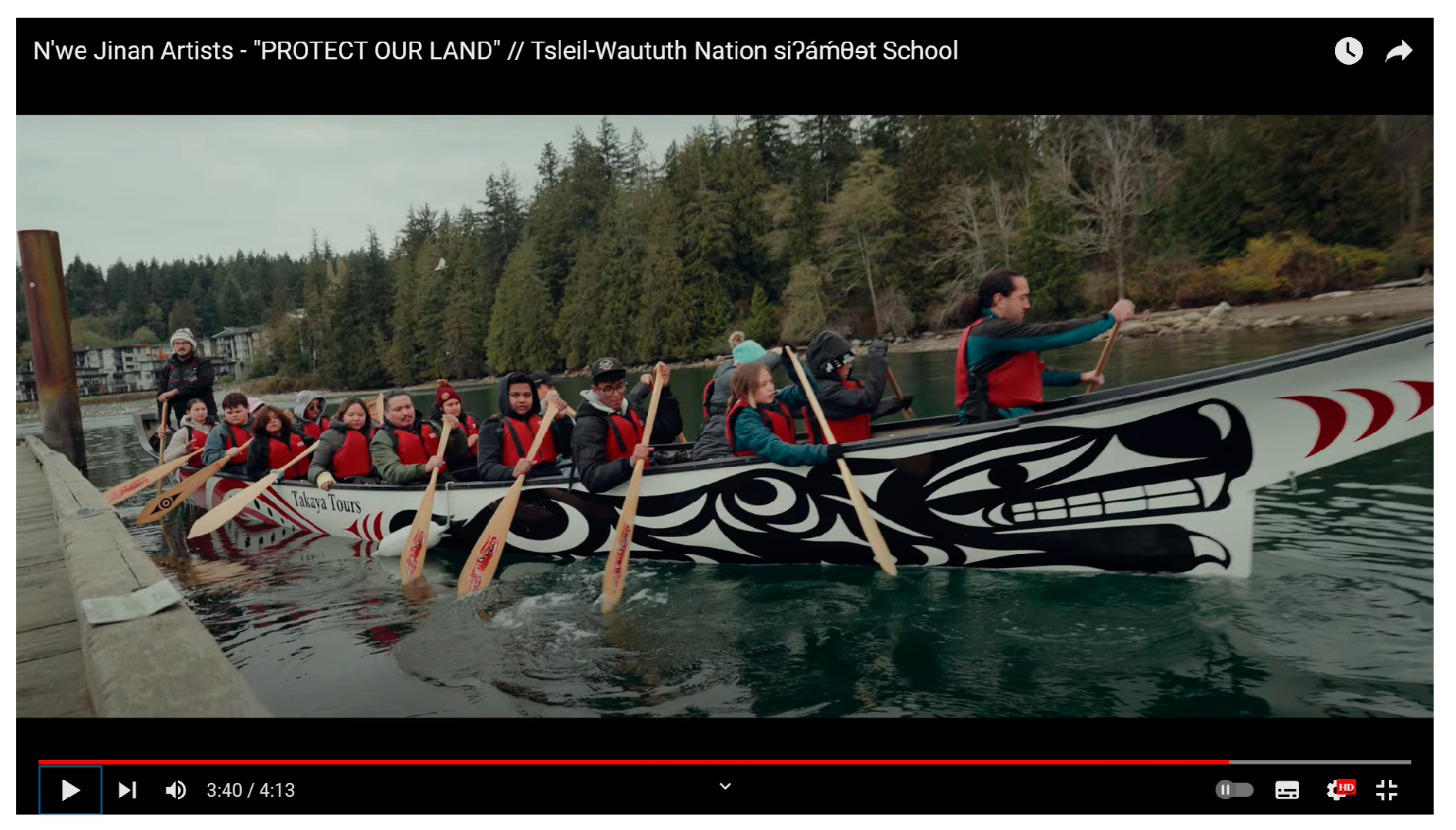

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2022a. Protect Our Land. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. December 7. Available online: https://youtu.be/kVWVSJKC0xs (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2022b. We Are Strong. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. April 22. Available online: https://youtu.be/7iIFC2QS-yc (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2023a. Everlasting. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. April 3. Available online: https://youtu.be/3qndUl6niT8 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2023b. Never Say Die. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. March 3. Available online: https://youtu.be/MVp1YZRTLLQ (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- N’we Jinan Artists. 2023c. Don’t Give Up. YouTube. Uploaded by N’we Jinan. March 27. Available online: https://youtu.be/N_0AVTfsf28 (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment. 1993. Dene Kede. Education: A Dene Perspective. Kindergarten—Grade 6. Available online: https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/dene_kede_k-6_teacher_resource_manual.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment. 2002. Dene Kede Education: A Dene Perspective. Grade 7. Available online: https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/dene_kede_grade-7_curriculum.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment. 2003. Dene Kede Education: A Dene Perspective. Grade 8. Available online: https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/dene_kede_grade-8_curriculum.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment. 2004. Dene Kede Education: A Dene Perspective. Grade 9. Available online: https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/dene_kede_grade-9_curriculum.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment. 1996. Inuuqatigiit: The Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective. Available online: https://www.ece.gov.nt.ca/sites/ece/files/resources/inuuqatigiit_k-12_curriculum_-_english.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Nunavut Department of Education. 2007. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Education Framework for Nunavut Curriculum. Available online: https://gov.nu.ca/sites/default/files/inuitqaujimajatuqangit_eng.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Peters, Mercedes. 2019. The Future is Mi’kmaq: Exploring the Merits of Nation-Based Histories as the Future of Indigenous History in Canada. Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region/Acadiensis: Revue D’histoire De La Région Atlantique 48: 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharte, Matias. 2019. De-Centering Music: A “Sound Education”. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education 18: 68–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Carla, and Ingrid Mündel. 2018. Story-Making as Methodology: Disrupting Dominant Stories Through Multimedia Storytelling. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 55: 211–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringsager, Kristine, and Lian Malai Madsen. 2022. Critical Hip Hop Pedagogy, Moral Ambiguity, and Social Technologies. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 53: 258–79. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1994. Orientalism. Toronto: Random House Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, Mela, and Lise Winer. 2006. Multilingual Codeswitching in Quebec Rap: Poetry, Pragmatics and Performativity. International Journal of Multilingualism 6: 173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Mela, Lise Winer, and Kobir Sarkar. 2005. Multilingual Code-Switching in Montreal Hip-Hop: Mayhem Meets Method, or, ‘Tout Moune Qui Talk Trash Kiss Mon Black Ass du Nord’. In ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism. Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slemon, Stephen. 1990. Unsettling the Empire: Resistance Theory for the Second World. World Literature Written in English 30: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Laurel C. 2010. Locating Post-Colonial Technoscience: Through the Lens of Indigenous Video. History and Technology 26: 251–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong-Wilson, Teresa. 2009. Moving Horizons: Exploring the Role of Stories in Decolonizing the Literacy Education of White Teachers. In Education, Decolonization and Development. Boston: Brill, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tacan, Frank. 2022. The Seven Sacred Teachings. Brandon Friendship Centre. Available online: https://honouringthegoodroad.com/seven-sacred-teachings/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Thevenin, Benjamin. 2022. Making Media Matter: Critical Literacy, Popular Culture, and Creative Production. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tlostanova, Madina. 2019. The Postcolonial Condition, the Decolonial Option, and the Post-Socialist Intervention. In Postcolonialism Cross-Examined: Multidirectional Perspectives on Imperial and Colonial Pasts and the Neocolonial Present. Edited by Monika Albrecht. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 165–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed. [Google Scholar]

- Urrieta, Luis. 2007. Figured Worlds and Education: An Introduction to the Special Issue. The Urban Review 39: 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wason-Ellam, Linda. 1991. Start with a Story: Literature and Learning in your Classroom. Markham: Pembroke Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wason-Ellam, Linda. 2005. Unpackaging Literacy: Multimodal Reading. English Quarterly 36: 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wason-Ellam, Linda. 2010. Children’s Literature as a Springboard to Place-Based Embodied Learning. Environmental Education Research 16: 279–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, Joy L., and Gumiko Monobe. 2017. Positioning Self in “Figured Worlds”: Using Poetic Inquiry to Theorize Transnational Experiences in Education. Urban Review 49: 153–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, Craig. 1999. Red on Red: Native American Literary Separatism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, Craig. 2005. Address. In Blackfoot Studies/First Nations Literature and Writing Conference. Lethbridge: University of Lethbridge, May 13. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crandall, J. Videographic, Musical, and Linguistic Partnerships for Decolonization: Engaging with Place-Based Articulations of Indigenous Identity and Wâhkôhtowin. Humanities 2023, 12, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12040072

Crandall J. Videographic, Musical, and Linguistic Partnerships for Decolonization: Engaging with Place-Based Articulations of Indigenous Identity and Wâhkôhtowin. Humanities. 2023; 12(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrandall, Joanie. 2023. "Videographic, Musical, and Linguistic Partnerships for Decolonization: Engaging with Place-Based Articulations of Indigenous Identity and Wâhkôhtowin" Humanities 12, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12040072

APA StyleCrandall, J. (2023). Videographic, Musical, and Linguistic Partnerships for Decolonization: Engaging with Place-Based Articulations of Indigenous Identity and Wâhkôhtowin. Humanities, 12(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12040072