1. Introduction

In interviews shortly following the release of 2019’s

Motherless Brooklyn (

Norton 2019), star, writer, and director Edward Norton discussed the changes made in adapting Jonathan Lethem’s book of the same name in an interview with the

Hollywood Reporter: ‘I think that film is very literal and that if we try to make a film about the 90s in Brooklyn with guys acting like 50s gumshoes, it will feel ironic.’ (

Giardina 2019) Norton’s comment of film being literal is an interesting one to adaptations scholars, perhaps given that discussions of the properties of medium are so often brought to the fore. Thomas Leitch’s ‘Twelve Fallacies’ has provided some headway in thinking more critically about this, particularly his assertion that ‘movies cannot legitimately be contrasted with literary texts on the grounds of their visual signifiers, because their actual signifying system, combining images and sounds and excluding information that might be processed by the other three senses, is a great deal more subtle and complex than visual iconicity.’ (

Leitch 2003, p. 154) Norton’s implication that film is ‘literal’ implies a key difference between literature and film that saps the text of nuance and particular forms of signification. Yet, as Leitch notes, the other sensual signifiers encompass an understanding of the text, seen more distinctly in the form of the verbal or aural within Lethem’s writing.

Norton’s view of film as literal perhaps goes some way to explaining his particular choices in terms of casting, and alterations to plot. His aim, according to comments made in a different interview, was to draw parallels between the racial and political tensions of the 50s and now, but ‘post-2016, it started to have second-level echoes, of more intensity than maybe we even were intending.’ (

Schwartz 2019) This comes with the film’s focus on race, poverty, and political control. Norton’s

Brooklyn moves back in time in order to be more relevant to today, suggesting we are closer now to the conditions then than those of the postmodern 90s. As is discussed in adaptations of historical periods by Tutan and Raw, ‘coming to terms with the present necessitates an adaptation of the past, and thus, of the present and future’ (

Raw and Tutan 2012, p. 15). Norton’s adaptation plays with temporality in an interesting way; in the interview comments above, it becomes clear that texts rely on context, and adaptations are bound by the temporal. Equally, what emerges is the way in which Norton feels he is able to alter the time period of the text in order to refigure his own understanding of Lethem’s text: ‘Jonathan’s characters are written in a very 1950s hardboiled detective style’ (

Giardina 2019). These comments, along with the rationale for changing the temporal context, offer a starting point for thinking about notions of genre. Norton here focuses not on the disability—linked here to Tourette’s—of the protagonist, but instead politics through the lens of genre.

Lethem’s text approaches genre in a more parodic way, which is absent in the 2019 film, as this article will explore. Instead, Norton chooses to focus on adapting contemporary political concerns through the setting of the past. Within this, there is the influence, or perhaps, the constraints, of genre which impact specifically on presentations of disability and gender. Through exploring Norton’s film, the layers of adaptation become clear: firstly, there is the adaptation of Lethem’s text to the film, which necessitates some changes demanded by medium. Secondly, there is the adaptation of temporal contexts—in this case, not only the setting of Lethem’s text, but of the contemporary political milieu through 1950s Brooklyn. And finally, there is the adaptation of disability to fit the needs of the narrative. Lethem’s text is always narrated

through disability, whereas Norton’s film offers a story constructed

despite it. This article argues that by exploring these layers of adaptation, and approaching the adaptation as a ‘palimpsest’ (

Hutcheon 2006, p. 6), attitudes towards both disability and masculinity come to the fore. By removing the element of parody, Norton’s film offers a limited opportunity to productively think about the elements of disability and masculinity.

In order to explore these ideas, I will first introduce the text, outline the approach to parody and adaptation, engage with ideas of genre, gender, and disability, before considering how temporality and tone are crucial in understandings of an adaptation.

2. Motherless Brooklyn

Jonathan Lethem’s (

1999) text focuses on Tourettic detective Lionel Essrog, who narrates the story of his mentor/leader’s murder and its investigation. The book follows a traditional crime arc in that we open with a murder, and the subsequent story is devoted to unravelling the tale and solving the whodunnit. What differs from traditional crime fiction narratives, however, are two things: firstly, that the book is set in 90s Brooklyn, but employs the self-aware style of the neo-noir, and secondly, that the narrator has Tourette’s. Not only does he have Tourette’s, but indeed, the narrative itself is shaped by Tourette’s. In the first ten pages alone, we see the way Lionel plays with language, how it shapes the way he sees the world. After overhearing his mentor, Frank Minna, having a conversation with a mysterious and unknown person, where the world ‘characteristic’ is used, we see this exchange:

‘I chewed on a Castle instead and gazed out the windshield, brain going Characteristic autistic mystic my tic dipstick dickweek and then I thought to take another note, flipped open the notebook and under WOMAN, HAIR, GLASSES wrote ULLMAN DOWNTOWN, thought Dull Man Out of Town.’.

(p. 10)

As with any other whodunnit, we see the detectives getting clues in order to solve their case. However, each clue here is punctuated by a Tourettic rewording (as we see above), an adaptation of the conversation, which rethinks, reorders, allowing the reader to play with language as Lionel himself does. Within the book, we are privy to Lionel’s pursuing of the case that hinges on his Tourettic approach: his mentor Frank tells him a joke as he is dying, knowing that he will continue to reword and reshape, providing him with the answer as to who has murdered him. This approach has led to Lionel being described as ‘one of fiction’s most memorable narrators’ (

Logan 2000). Lethem himself, being quoted in the same review as this description, outlines his approach as such: ‘the book hinges on the joke of replacing the hard-boiled narrator—who’s supposed to be this Bogart figure impressing everyone with his Machiavellian control of circumstances and conversation—with this absolutely soft-boiled chaos of language’ (ibid). This focus on language is foregrounded in the text, and the element of the crime genre is reshaped by it, with surprising and innovative outcomes. Even as early on as this review, which is from 2000, there are mentions of Edward Norton acquiring the rights to the book as a film.

This foregrounds the long production history of the 2019 film, which was described as a ‘passion project’ (

Floyd 2019), but one that was put off due to Norton’s various other projects. Lethem’s Essrog as lone narrator relays the case, travelling across New York and over to Boston to solve it, in what at times feels like a wild goose chase. Of course, as with many a crime fiction novel, there is a femme fatale figure, but one here, a woman named Kimmery, that is both unknowing and dismissive of her role. Norton’s

Motherless Brooklyn, as noted, changes the temporal setting of the story. However, this also comes with a changing of story, one that engages with different themes and ideas than Lethem’s text. In the film, set in the 1950s, the central story engages with Lionel Essrog (Edward Norton) trying to solve the murder of mentor Frank Minna (Bruce Willis), which uncovers a broader conspiracy around race, housing, and local government. Unlike Lethem’s text, which sees the murder as linked to the greed of a small-time gang leader and the tensions with his brother, Norton’s film focuses its attentions on bigger social issues, mediated through the events of the present.

It is not being argued here that the lack of fidelity is unacceptable, or that it indeed, renders the film as being lesser than Lethem’s text. Nor am I saying that the film cannot do what the book does because of concerns around medium. However, two things are key here: firstly, that Norton himself references the medium as being partly crucial to why these changes were made, and secondly, these changes result in a different text, as all adaptations do. Adaptations are both defined by, and signify a relationship with another text, and indeed, the production history, the repeated discussion of Norton’s ownership of the rights for 20 years before the release of the film, unquestionably link it to Lethem’s text. As Colin MacCabe argues, using the source text in the marketing in the film is ‘claiming a cultural ambition and an existing audience.’ (

MacCabe 2011, p. 9) What is key to explore here is what the impact of the differences are. Rather than claiming one text has more value than another through an evaluative approach as often emerges with fidelity, I am instead looking at how the alteration to the text, through temporal means, tone and plot, results in a change in the presentation of disability and masculinity.

As I’ve already noted, the film itself signals itself as an adaptation. Not only this, but I am using Linda Hutcheon’s approach to adaptation, which is denoted through it being ‘

seen as an adaptation’ (

Hutcheon 2006, p. 6). Due to this framing of the film as an adaptation as I note above, it invites comparison. Here, I will explore how comparing the texts highlights the gaps between them, resulting in an illumination of the differences in representation of disability and masculinity. These gaps emerge partly due to the absence of parody, and both the understanding of parody and the implications of its absence will be set out below.

3. Parody and Genre

Before I go any further, I want to situate my discussion of parody. I am not using Thomas Leitch’s idea of parody, which he notes ‘debunks the adapted material’ (

Leitch 2017, p. 5), as this is arguably not what Lethem’s text does. Instead, I am using Linda Hutcheon’s approach to parody, which she sees as ‘an ironic subset of adaptation’ (

Hutcheon 1985, p. 170). Looking at parody this way adds another layer of adaptation to the discussion here, suggesting that Lethem’s parodic text could be a form of adaptation of the crime genre. The key idea that Hutcheon puts forward is as follows:

The collective weight of parodical practice suggests a redefinition of parody as repetition of critical distance that allows ironic signaling of difference at the very heart of similarity.

This ‘interconnectedness’ that she notes (

Hutcheon 1985, p. 182) allows for a thinking about the parody as a fruitful way to explore a text—highlighting problems, absent discourse, whilst paying homage to the boundaries a text puts in place.

Lethem’s text is aware of its relationship to genre, and approaches it in an ironic way, resulting in a parody (or pastiche, depending on how you see it) of the crime fiction genre. We see this throughout the text, with Lionel referencing his ‘hard-boiled despair’ (

Lethem 1999, p. 93), and making self-aware comments about the genre he is situated within: ‘Detective stories always have too many characters anyway’ (p. 119). Lionel references other hard-boiled fictional detectives, such as Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, and positions himself as performing in the investigation: ‘For once I was playing lead detective instead of comic—or Tourettic—relief’ (p. 143). Moments like these that punctuate the text function as a postmodern consideration of the genre; combined with the Tourette’s of the detective, and the subversion of the traditional narrative, we see a dismantling of the usual approach of the crime narrative. In discussing the novel, Pascale Antolin argues that it is a ‘construction questioning both the social and literary order’ (

Antolin 2019, p. 5). Antolin also sees the text as a parody, specifically a ‘Bakhtinian parody’ which is ‘a rewriting of the conventional genre’ (

Antolin 2019, p. 16).

Unlike Lethem’s novel, Norton’s film does not offer a parody, but rather, a rigid attempt to follow the conventions of the noir. This, as Megan Feeney notes in a review, is at times ‘heavy handed, unintentionally verging on parody’ (

Feeney 2020, p. 48), but there is no intentional parody in play here. The difference here is that Lethem’s text is

aware of its parodic nature, whereas Norton’s approach in its attempt at genre conformity results in a text lacking in substance. A knowing approach to genre can act as parody, pastiche, commentary; the unknowing approach and attempt at faithful recreation of genre often feels hollow, contrived, and therefore often fails to achieve its aims. With Norton’s film, the iconography of crime fiction is emphasised. We see frequent shots of the Brooklyn Bridge, the space of the urban sprawl, so common to the genre, foregrounded visually. By situating it in the 50s, the outfits and general setting appear to mimic the hardboiled noir films of the 40s and early 50s. The style and tone of the film work within the crime mode, with darker colour palettes and use of light and shadow similar to the noirs of the 40s (see

Figure A1).

Motherless Brooklyn is clearly positioned as a crime film in the vein of the hardboiled films, through its characterisation, setting, plot, and iconography. As Thomas Sobchack argues, genre film is ‘not realistic’, because of the ‘dramatic’ nature of it. This is shaped by the genre film’s pursuit of imitation, he argues (

Sobchack 1975, p. 197). Imitation here highlights the constructed nature of understandings of genre, masculinity, and disability, as will be further explored below. What adds to this is the temporal difference; though it is outside the cycle of the hardboiled films of the 40s and 50s,

Motherless Brooklyn seeks to recapture the style and tone of those films. This attempt at imitation, illuminated by the aspect of adaptation, necessitates an unrealistic and synthetic approach to character, bound by the needs of the imitative framework.

The hardboiled genre itself survived, according to John Scaggs, due to its ability to be culturally appropriated (

Scaggs 2005). Notably, he cites the role nostalgia for the genre has played in films of the late 20th and early 21st century:

The Black Dahlia and

L.A. Confidential as key examples. Nostalgia is key in this; with nostalgia comes an

adaptation of the past that relies on an (often) aestheticized version of events. Lethem’s

Motherless Brooklyn is not nostalgic, however, but parodic. Norton’s film, by contrast, in its nostalgia becomes a (re)construction, as much of nostalgia is.

1The film is underpinned by many aspects of the hardboiled genre, adhering to the elements of genre to such an extent that it reads as a classic example (or perhaps an imitation of a classic example) of the genre. For example, there is a hybrid between professional and amateur evident in the hardboiled mode—these private eyes are not within a state-structured law enforcement department but self-employed, freelance, and run by their own rules a lot of the time and what they believe to be ‘right’. There are no such questions of ‘right’ in Lethem’s text, but in the film, there is a moralising tale underpinning it, that of the systematic demolishing of houses occupied by poor minorities to control and segregate communities. Norton’s Lionel uncovers the hypocrisy and nefarious antics of Robert Moses, playing like Philip Marlowe, a ‘questing knight’ (

Scaggs 2005, p. 62).

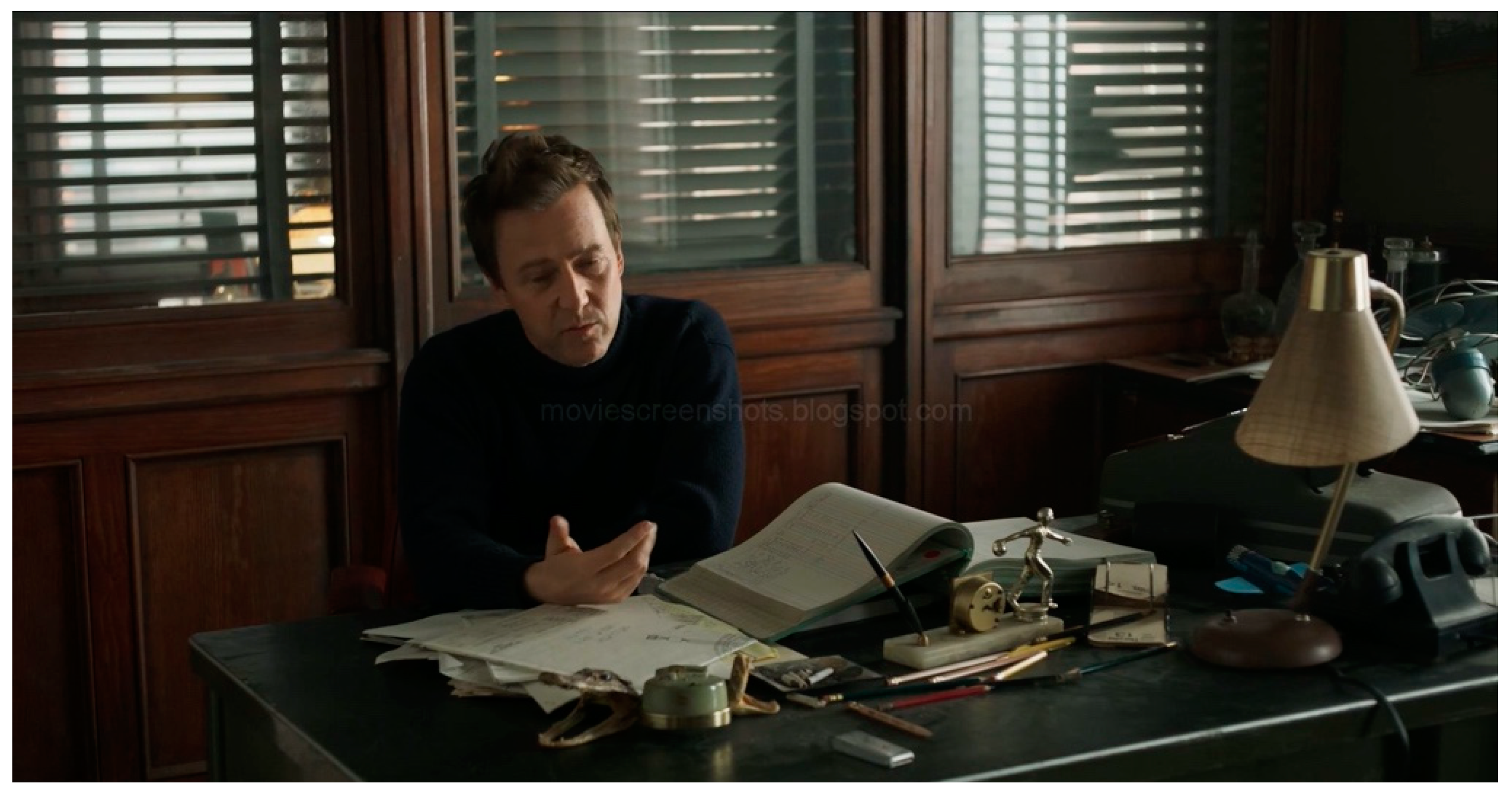

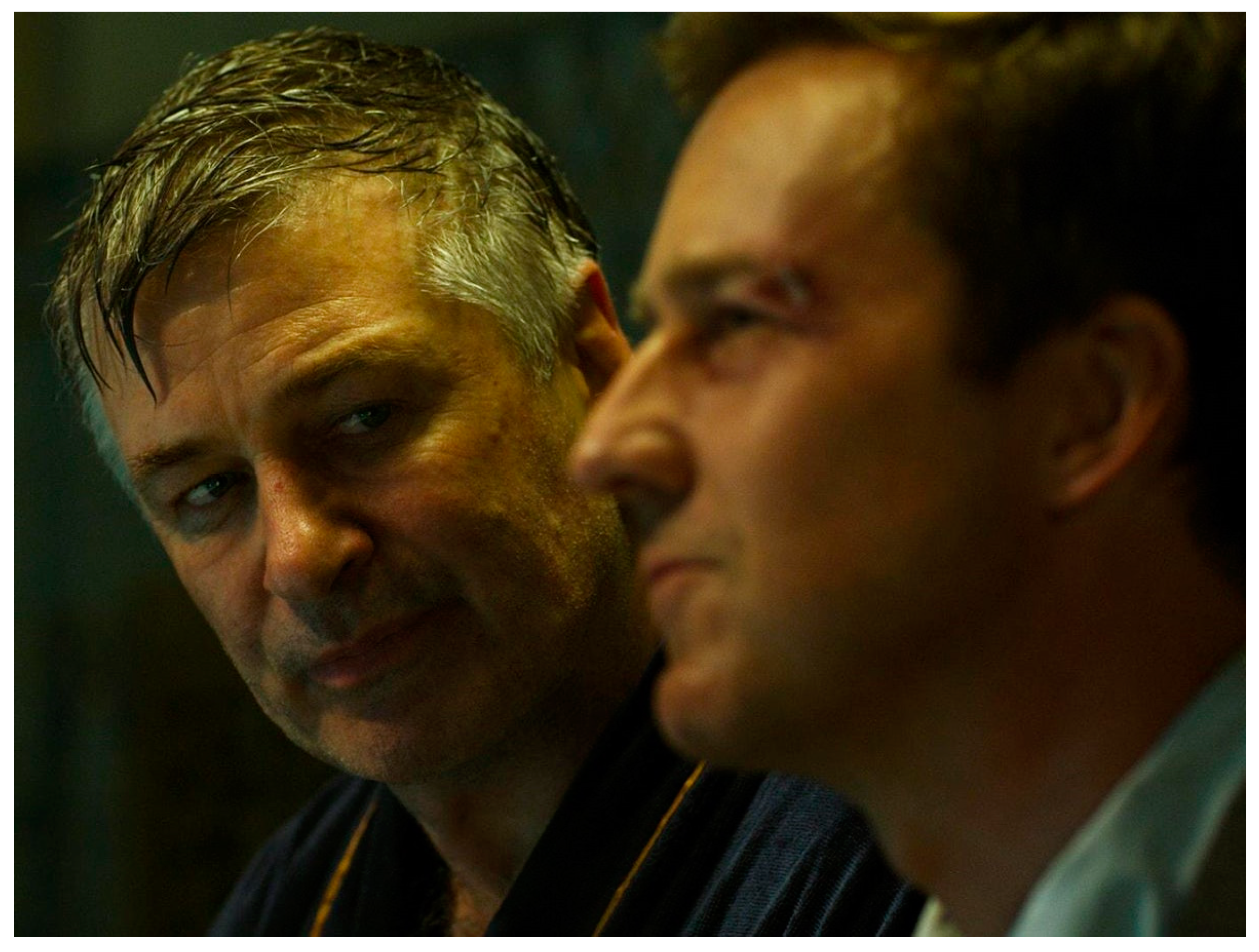

Motherless Brooklyn tries to subvert the elements of genre in some ways, as with the detective agency rather than the lone PI. In the hardboiled mode, the private eye is an ‘I’, a loner, existing outside or beyond the socio-economic order of family. They are independent and self-sufficient. They are so often waiting for the truth to make itself known rather than seeking it out. Lionel, despite his desire to be one of Frank Minna’s ‘men’, a collective which functions as a pseudo-family, is often ostracized because of his Tourette’s. Norton’s Lionel is equally alone, foregrounded in the visual differences between him and the other detectives of the agency. As we see in

Figure A2 and

Figure A3, Lionel is set apart, cornered physically by his desk, in a turtle-neck sweater. By contrast, Tony Vermonte (Bobby Cannavale), Minna’s right hand man, as it were, is in suit and tie, his suspenders on show, the epitome of power and authority as seen in his stance and positioning. These differences in masculine presentation also become apparent on examination, as I will touch upon below.

Perhaps what is also important to note in the genre of crime, particularly the hardboiled, is the aspect of narration. The first-person narration of some of these texts decenters the plot and makes the narrative focus the PI. However, in most cases the PI is given a passive role, following the story. This compromised in Lethem’s text as the story is literally adapted and retold through the Tourettic approach; although we have the occasional voiceover in the film that allows us an insight into the thought process of the character, these do not include any of the verbal tics that Lionel describes in the book, thereby only giving us the outline, not the Tourettic adaptation of the story. This adaptation and rewording links to the notion of parody, which ‘marks both continuity and change’ (

Hutcheon 1986, p. 204). Lionel is retaining elements of the case but altering them linguistically and furthering his understanding by a repositioning—at first linguistically which then offers new perspectives.

By contrast, because Norton’s text lacks the parodic element, the element of ‘interconnectedness’ is missing, and instead, the film’s concern is with generic constraints. With genre comes the horizon of expectations, the way in which the audience will engage with the text (

Jauss and Benzinger 1970). The audience, in watching a crime film, expect certain elements, and so the inclusion of these elements is key. This is further relevant when we consider Lacey’s point that ‘Genres, of course, are subject to history; that is to say that they are a product of particular societies at particular times (

Lacey 2000, p. 170).’ Given

Motherless Brooklyn is created outside the historical context of the formation of the crime genre, the inclusions of a series of patterns and other elements that construct the crime genre, specifically the hardboiled/noir subgenre, can only ever be a reconstruction, or adaptation of a generic mode.

4. Masculinity, Performance and Disability as Adaptation

As with the crime genre, the representation of disability in men is linked with a negotiation of masculinity (

Manderson and Peake 2005). What it may result in is the performance of gendered stereotypes, or a version of identity that upholds hegemonic values.

Motherless Brooklyn both foregrounds genre, particularly the elements of genre that illuminate idea(l)s of masculinity, and functions as a performance of disability, notably in Norton’s text. This is because of the way in which the body is implicated in the filmic text, arguably. I have asserted elsewhere that ‘the body itself becomes adapted

by the character, and the character adapted

to the body.’ (

Wilkins 2022, p. 5) The actor’s body, in this case, Edward Norton’s, is crucial in the understanding of the Tourettic body here. Our knowledge of his body translates the Tourettic elements into a performance on the surface of his body for us to read; the gestures and tics an interpretation of Tourette’s, one rendered as performance through its difference from the acting body. Sandahl and Auslander consider the relationship between interpretation, performance, and disability explicitly here:

‘As in traditional representation, disability inaugurates the act of interpretation in representation in daily life. In daily life, disabled people can be considered performers, and passersby, the audience. Without the distancing effects of a proscenium frame and the actor’s distinctness from his or her character, disability becomes one of the most radical forms of performance art, “invisible theater” at its extremes.’

It is this ‘distinctness’ of Norton’s from the character of Lionel; audiences are interpreting what they know to be a representation of the Tourettic self. The level of distinctness is interestingly something not often desired by audiences—fidelity to an idea of character is usually preferred in adaptations, as seen by the response to casting seen as ‘divergent’ from the character.

2 Jonathan Loucks argues that this is because of the role of imagination for the reader (

Loucks 2011, p. 145) and ‘Thus, the casting of the film takes on another level of authenticity in that the actors must not only match the characters’ temperaments, but faithfully embody their physiques’ (ibid). However, KS Williams argues that there can be no fidelity essentially. Discussing the theatre, she notes that it employs the ‘actor’s body beneath the character’s theatrical body, and this overlapping presentation complicates the dramatic fiction’s descriptions of the character the actor personates. Theatrical performance thus trades a kind of clarity produced by the written word for the thrill of the human actor’ (

Williams 2013, p. 768). This thrill could be seen as the mediation of the written word, the character. In the case of

Motherless Brooklyn, we see Lethem’s words filtered through the physicality (importantly not adhering to the description of ‘large men’ Lethem offers) and the non-Tourettic body of Norton.

Although I have already noted that I am not making a claim for fidelity being essential here, or arguing that Norton’s film should be seen as less significant due to its differences, it is also important briefly to continue to think about the changes made. These changes, as I’ve begun to argue, illuminate the idea particularly of the performance of disability, and therefore, its understanding in culture. The filmic representation of Tourette’s here appears to be inconsistent. In the trailer for the film, the opening shot is of Lionel (Norton) in a two shot with Gilbert (Ethan Suplee), his head twitching. The voiceover comes in quickly: ‘I got something wrong with me. That’s the first thing to know. I twitch and shout a lot.’ The comparison of the ‘normative’ body of Gilbert is important in highlighting the difference of Lionel’s. Throughout the trailer, most of the clips show Lionel ticcing, giving the impression of Tourette’s being key to the film itself. However, the actual film itself pulls back from this.

Lionel’s moniker of ‘freakshow’ (seen in the book and in the film) is repeated minimally, unlike Lethem’s text. The change of time period means that Tourette’s was not as well-known

3 and so the gestures and tics that Lionel displays are interpreted differently in the story. The film exaggerates and often misrepresents the symptoms of Tourette’s. As Calder-Sprackman, Sutherland and Doja argue: ‘Given that the primary goal of a movie is to entertain, it is understandable why screenwriters exaggerate diseases to create dramatic or comedic effects.’ (

Calder-Sprackman et al. 2014, p. 230) Sutherland discusses the representation of Tourette’s onscreen and finds that in some cases, symptoms of other neurodiverse conditions like Autism are presented but labelled instead as Tourette’s. This is similar to the presentation of Lionel here, who other than ticcing, has an extraordinary memory and can repeat conversations verbatim. He can also visualise scenarios from language only (as we see with

Figure A1). Although this links to Lethem’s Lionel and his obsession with language, here it reads as savant-like, a common representation of autistic people in film and television.

4Equally, Lionel’s Tourette’s is mostly something that helps him in terms of solving the case, rather than hindering, becoming a convenient plot device at particular moments. When he is listening or in crucial moments where stillness is required, he is often able to maintain it. His tics sometimes occur in disruptive ways, such as in the jazz club he visits, resulting in him getting thrown out, but the tics lessen as the film goes on, and the focus becomes the central puzzle of the murder and uncovering the scandal attached to Moses Randolph. Given this lessening, and particularly in the manner in which the trailer foregrounds Tourette’s as the unique approach to what is a conventional crime narrative, it becomes a performance of disability in order to entertain and hook the audience, rather than as a postmodern commentary on the genre that Lethem offers. This may be because as Mark Asch notes, ‘Norton makes

Rain Man comparisons inevitable because Lionel’s disability follows the demands of the script rather than the other way round’ (

Asch 2019, p. 71). Disability here is adapted

by the needs of the text, rather than the text being adapted

through disability as we see with Lethem’s text.

Arguably, Norton’s approach could be an attempt to temper some of the more uncomfortable approaches to disability in the literary text, wherein Lionel is othered due to his Tourette’s, described variously as ‘too strange’, ‘crazy’, and that Minna was ‘Jerry Lewis’ and Lionel ‘the thing in the wheelchair’ (

Lethem 1999, p. 183). By putting Lionel as protagonist and including his Tourettic behaviour but not drawing attention to it too much, or using slurs and insults to describe him, it reads as an attempt to frame it as difference rather than disability. Though, as has been noted throughout, Lethem’s text is a parody, and the book plays with the question of Tourette’s, reshaping both genre and ideals through the linguistic. Pascale Antolin sees the use of Tourette’s in the novel to offer a ‘major challenge to the negative perception of disability’ (

Antolin 2019, p. 15) and perhaps most importantly:

While the meta-generic comments symbolize his freedom from generic and narrative conventions, disability turns into a means of liberation from traditional representation.

(p. 18)

This use of disability as liberation is in line with the parodic approach of Lethem’s text. Returning to Hutcheon’s notion of parody, she argues that it is ‘the mode of the marginalized’ (p. 206). The use of parody and disability here thus seem well suited—an adaptation of traditional forms that offer a new perspective.

Norton’s film, though perhaps trying to temper some elements which may be read differently outside of a parodic context, is also bound by ideals of masculinity tied to genre. As Philippa Gates notes, ‘cinema offers a constructed, performed and ideal masculinity while promising its audiences that it is a real and attainable one’ (

Gates 2006, p. 37). Earlier, I raised the difference between the character of Tony Vermonte and Lionel, notably in their presentation in

Figure A2 and

Figure A3. There are clear differences in positioning, gesture, and costume that present Tony as a more conventional masculine hero. Yet, audiences are still primed to identify Lionel as the protagonist, and as Gates continues:

The protagonists of the detective film are constructed as representations of heroic masculinity…but there are many ways in which this demonstration of heroic masculinity is just a performance. […] the hardboiled detective is presented as epitomizing tough masculinity…but his is a divided masculinity, living on the periphery of society.

This question of the performance of masculinity links to the way in which disability is also understood. Arguably, the elements of masculinity in Norton’s text are contingent on an absence of the markers of disability. The moments that adhere to a more conventional presentation of the hardboiled detective—such as the romantic or sexual engagement with women, or moments of confrontation—see a lessening of tics, and Norton’s Lionel is once again bound by the constraints of genre. Given the adaptive nature of the text, these needs of genre and masculine standards attached to them become more evident. Alongside this is the question of disability, which arguably functions as a contemporary approach, an adaptation of the past shaped by the present.

5. Temporality, Adaptation and Parody

Within the text, there are several aspects of Lethem’s story that have been filtered through contemporary attitudes and events. As noted above, one is the attitude towards disability and difference coloured by present-day approaches. Norton’s text in its rewriting and resituating of the story in the 50s offers a buffer of history, a safe way to critique and draw parallels between the events of then and those of now. As Norton put forward in an interview, the events of 2016—notably, Trump’s election—shaped the story itself. I will briefly discuss these parallels, considering the role of history and the present in adaptation, and how it is shaped by the absence of parody.

One of the key storylines added in Norton’s

Motherless Brooklyn is the nefarious grip that Moses Randolph (Alec Baldwin) has on Brooklyn. He is in charge of building development, and has been systematically evicting and demolishing areas populated by those in poverty and notably, non-white areas. His character is based on Robert Moses, developer responsible for a number of key buildings in New York. The inclusion of this storyline was to highlight ‘the secret history of modern New York’ and its ‘institutional racism’ says Norton (

Denninger 2019). Though, given its production in the contemporary moment, the characterisation also echoes several issues post-2016, as Norton is aware of. This is made explicit in a few ways, through dialogue and casting choices.

Although based on (functioning perhaps as an

adaptation of) Robert Moses, Baldwin’s Moses Randolph acts in some ways as a processing of Trump’s presence in the American zeitgeist at the time of its release (see

Figure A4). For one, the choice of Baldwin is interesting given his history of impersonating Donald Trump for

Saturday Night Live sketches (arguably this parodic presentation does more to challenge than the reconfiguring of a Trumpian element in

Motherless Brooklyn). Secondly, dialogue famously uttered by Trump is used in the film. Within the film, it emerges that Randolph is trying to hide the fact he raped a black woman and they had a child (played by Gugu Mbatha Raw), who is campaigning against his actions. When Lionel pieces it together and confronts him in a swimming pool, Randolph admits his actions with the phrase: ‘I moved on her’, echoing Trump’s 2005 comments leaked in 2016.

5 These two links present Randolph as an adaptation and mediation of anxieties around Trump’s impact on society. In

Motherless Brooklyn, Randolph’s power to enact policies that strengthen racial division echoes many perpetuated by Trump, including the building of the wall between the US and Mexico, and the travel ban which primarily targeted Muslims.

As such, the inclusion of these links to Trump and Moses can be seen as a reckoning with the legacies and ongoing impacts of these figures in the contemporary moment. The film both re-enacts the past and uses it to comment on the situation of the present—particularly pertinent given the swelling support for the Black Lives Matter movement, with demonstrations and events occurring frequently, but gathering strength 2016 onwards in the wake of Trump’s election. Equally important is the cultural context of the #metoo movement, which emerged in 2017. Randolph’s comments and behaviour are read in this light, as well as fuelling a perceived crisis of masculinity.

6 The use of the crime genre, so often linked to masculine ideals and behaviours, therefore becomes doubly important. However, the absence of parody in Norton’s text strips impact from it, presenting a story that at times, as Feeney notes, offers ‘explicit moralizing’ (

Feeney 2020, p. 48). Unlike Lethem’s text, which subverts ideas of masculinity and genre through its use of disability, Norton’s focus on the temporal shift and (re)presentation of contemporary political debates through the past only reproduce rather than challenge. As Hutcheon argues, ‘parody seems to offer a perspective on the present and the past which allows an artist to speak TO a discourse from WITHIN it, but without being totally recuperated by it’ (

Hutcheon 1986, p. 206). Lethem’s postmodern parody shows its awareness of the conventions and alters them. Norton’s text, with its absence of parody, does not speak ‘to’ a discourse as Hutcheon would frame it, but instead, speaks

of it, or

about it.

6. Conclusions

All of this is to argue that the status of adaptation highlights cultural shifts in attitude and shows how genre can shape presentations of identity. Specifically here, adaptation renders a performance of masculinity and disability, one that is constrained and shaped by generic needs. The change in tone from parody undercuts the playful engagement with these ideas that occur in Lethem’s text. The temporal is also key—both the context the adaptation is produced in, and the one it is set within. An adaptation does not occur in a vacuum, and a text is not a fixed thing. How it is read differs on the moment it is read in. Understanding an adaptation arguably requires a knowledge of various contexts; the historical moments shaping

Motherless Brooklyn as a film are different from those of Lethem’s text. The slipperiness of the text and its adaptation (by virtue of its shifting meaning) acts more as a snapshot of a moment or perspective: the point leading up to 2019 where Norton interpreted and adapted Lethem’s text. Rather than being a filmed version of Lethem’s text, it thereby results in a different story. This is because of the historical factors shaping the creation of an adaptation, as Colin MacCabe argues:

‘To forget that a text is based in an individual body or bodies with their specific historical trajectories is to engage in the worst kind of academic idealism. However, those individual bodies need to be understood as dividual, divided by the multitude of dialogues, both past and present, which constitute them.’

The dialogues here are with contemporary understandings of disability, masculinity, and politics, as well as with the events of the past (through the actions of Randolph) filtered through the crime genre which in turn shapes how these dialogues are read. Because of Norton’s framing of the text in this way, it becomes a subjective view of Lethem’s text and of the contemporary moment, an interpretation. Tutan and Raw argue that ‘one’s interpretation of the past becomes more suggestive of the ways in which that person has adapted to the present for purposes of determining the future’ (

Raw and Tutan 2012, p. 12) which is evident here.

This approach however presupposes that audiences will read these elements in a prescribed way, that of Norton’s intention. However, we know that this is not often the case. As Frans Weiser argues, ‘Irrespective of the degree of intertextuality in a written text, it is ultimately consumed as a form of adaptation by audiences who transpose it onto their previous network of historical knowledge.’ (

Weiser 2017, p. 112) Audiences and their approach to an adaptation depend on knowledge: in this case, knowledge of the context of the text(s) and their own perspectives. As Scholz posits, ‘film adaptations should be approached as historical events, not mere re-enactments of cultural texts’ (

Scholz 2013). I would like to add to this, and argue that tone is also key to understanding an adaptation, as it alters the presentation of identity, genre, or historical moment.

We may approach the adaptation and the act of adapting in the same way that crime fiction broaches the act of detection: a breaking down of ‘reality’ in order to construct a new one that works, so we can know what ‘really’ happened. In a similar vein, the adaptation breaks down the ‘reality’ of the text it adapts to construct one that works in the context of the present, and one that works for the creator and their understanding of the text. Thus, the ‘reality’ of the text is contextual and subjective. Lethem’s Lionel presents a reality shaped by Tourette’s, and attempts to reconstruct Minna’s death in order to understand how he operates in the world in Minna’s absence. This becomes particularly important given the idea of Minna as his ‘sponsor’ and Minna’s handing him a book on Tourette’s, through which he ‘contextualised’ himself (

Lethem 1999, p. 82). Lethem’s construction of reality and its reconstruction through the postmodern crime fiction lens operates as a thinking through of identity and the way it adapts (and

adapts to) the world around us.

By contrast, Norton’s construction of reality is one that has broken down the constituent elements of Lethem’s text—taking Lionel’s Tourette’s, and the framing device of Minna’s death—and presents a different story altogether due to its adherence to generic conventions. Rather than thinking through identity on an individual and personal basis, the focus on the figure of Moses Randolph and the Trump echoes present within him offer a broader conception of identity, one that implicates the political. Norton’s use of these aspects, his desire to showcase the characters in such a way that aligned with his understanding of Lethem’s text (as ‘hardboiled’, notably) and one that could offer a commentary on the contemporary, results in a reinscribing of ideas of masculinity and disability.

Returning to Hutcheon’s idea of the ‘palimpsest’ where ‘more than one text is experienced’ (

Hutcheon 2006, p. 116), Norton’s adaptation in its signalling of a connection to Lethem’s work (in its production history, the interviews, title, and characters) enable us to experience it as such. What becomes apparent in this double experience is the difference, which arguably is experienced as a lack here. Although Norton’s text offers a new plot, setting, and the pursual of different themes, the absence of parody and the change to the presentation of disability reduce the opportunity the text has to challenge, subvert, or play with the conventions we are used to seeing in the crime fiction genre, and with it the hegemonic ideals (primarily of masculinity) that are contained or reproduced within it.

In the case of Motherless Brooklyn, it becomes an adaptation of a (particular) political viewpoint through the lens of the past. Yet, the past here is infused with the present—we cannot understand the crime fiction genre and the film’s imitation of the hardboiled mode without considering its temporal context. The inclusion of references to real-life figures, past and present, shape the reading of characters, and in turn, the reading of the text. Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn contains no such references. Norton’s film, however, in these inclusions, attempts to mobilise the core character of the text—Lionel—to reinterpret, rethink, and reshape our approach to the past. Although Lethem’s Lionel is able to reshape, and alter reality through his Tourettic play with language, the same does not occur within Norton’s text.