1. Introduction: Politics and Identity

What is a child? In one sense, I can offer a very clear answer:

What is a Child? (

Alemagna 2008) is an English translation of a picture book for children, ‘

Che cos’è un bambino?’ by Beatrice Alemagna, an internationally celebrated author and artist

1. In another sense, the question is open-ended. In the title of Alemagna’s text, ‘a [c]hild’ is not sufficient, turning as it does on something that is and is not the child, the ‘[w]hat’ of the child’s being. One starting point for a thinking-through of the politics of children’s literature, and the politics of childhood, is that even as questions concerning the child are posed, and in the title of the book, at least, are not resolved, a certain identity is secured: the question of the child’s identity is dependent on ‘a [c]hild’ that is other to that identity, that can be identified independently of that identity, and that is never in doubt.

This might seem a minor point, but it is one that can be framed in terms of significant debates among children’s literature scholars. Take, for example, Marah Gubar’s following contention:

The fact that something is very difficult to define—even ‘impossible to define exactly’—does not mean that it does not exist or cannot be talked about. In such cases, we simply have to accept that the concept under consideration is complex and capacious; it may also be unstable (its meaning shifts over time and across different cultures) and fuzzy at the edges (its boundaries are not fixed and exact). Childhood is one such concept; children’s literature is another. True, there is no eternal essence that all children share—not even youth. (To a parent, a forty-year-old can be a child.) But it does not follow that the designation ‘child’ has no meaning, that we cannot know anything about the lives, practices, and discourse of individual children from different times and places. Similarly, in order to expand our knowledge of children’s literature as a whole, the best approach we can take is to proceed piecemeal, focusing our attention on different subareas and continually striving to characterize our subject in ways that acknowledge its messiness and diversity.

There are several shifts in this analysis to which I would like to draw attention. There is an understandable resistance to claims about the non-existence of the concept of childhood. I do not know of any contemporary critic who claims the concept of childhood does not exist, or that it has no meaning: this is not what I take the anti-essentialist arguments of Karín Lesnik-Oberstein and Jacqueline Rose, with their debts to psychoanalysis and deconstruction (

Lesnik-Oberstein 1994;

Rose 1984). Indeed, I would take a claim to the certainty of absence to be the reverse of those concerning absolute presence. Counter to this notion of non-existence, Gubar forwards an unstable and fuzzy ‘concept’, where instability is limited (because, seemingly, there is a true history of shifts in meaning), and its fuzziness localised (the concept has a shape, which includes edges, and it is these only that are not fixed—there is thus a certainty positioned against the edge, a certainty too of structure, that divides edge from its other, and an internal structure too, that divides the ‘subarea’ from its others). From this limited fuzziness and instability, Gubar moves to make a claim to knowledge about individual children, their lives, as well as their discourses. This seems to me not to engage the sense in which the meaning of children—‘

What is a Child?’ (Also, my emphasis)—is problematised both by a necessary internal split and a framing perspective: the child as other to its meaning but also the child known from a perspective other than its own. In terms of this last, it is helpful to turn to Jacqueline Rose’s classic formulation:

Childhood is not an object, any more than the unconscious, although this is often how they are both understood. The idea that childhood is something separate which can be scrutinised and assessed is the other side of the illusion which makes of childhood something which we have simply ceased to be. In most discussions of children’s fiction which make their appeal to Freud, childhood is part of a strict developmental sequence at the end of which stands the cohered and rational consciousness of the adult mind. Children may, on occasions, be disturbed, but they do not disturb us as long as that sequence (and that development) can be ensured. Children are no threat to our identity because they are, so to speak, ‘on their way’ (the journey metaphor is a recurrent one). Their difference stands purely as the sign of just how far we have progressed.

What interests me about What is a Child? is firstly the sense in which ‘a [c]hild’ is constructed as lacking meaning, or as formulated above, that the question of a child separates it from the ‘[w]hat’ of its being. Might this suggest that the complexity and capacious nature of the identity child includes that which confounds or is other to notions of identity? Is the ‘a [c]hild’ to be included in the identity that I read to be, in some sense, other to it? Is there a necessary meaninglessness to the child, that is, to the posing of the question of meaning? In short, what is a child? if the child is at one stage other to its meaningful identity? What is ‘a [c]hild?’ on its own if the question of identity demands a split, a division, or deferral of identity?

My concern is with the extent of ‘messiness’, as formulated by Gubar. I am not interested in a discourse premised on non-existence. I am rather intrigued by a problematisation of the ‘concept’. There is a unity granted the concept, even as it is brought into doubt by Gubar, a unity comparable to that of the child for Alemagna. ‘[A] child’ in ‘[w]hat is a [c]hild?’ has the danger of being returned as a condition for meaning and of a unity that is necessary for diversity. A connection can be made at this point to Gubar’s notion of a ‘subarea’, a specific, localised aspect that nonetheless is set up in a hierarchical relationship to the whole. It is the subarea that produces the ‘whole’, the specificity, ironically, that constructs the general condition. The variety of children is the way into an apparent knowledge of childhood more generally.

With that in mind, let us return to Alemagna’s text, or the back cover peritext: “Through bold and sensitively observed portraits and a thought-provoking text, Beatrice Alemagna inspires children, and adults reading with them, to consider their own identity” (Back cover blurb). An own identity can be considered, and the considering parties are adults and children. As the title of the book is What is a Child?, does ‘a [c]hild’ own the identity of children? If so, what are the limits of that identity? Is there something in one’s own identity that might belong to another? For the blurb, both adults and children seem to be subject to certain limits. The blurb already knows who will ‘inspire’ whom (or who would be ‘inspire[d]’ by whom), and the subjects for each are already settled: it will be ‘children’ who will be ‘inspire[d]’ by ‘Beatrice Alemagna’. The way of ‘inspir[ing]’ is also designated as ‘children’ are supposed to ‘read’ certain things, such as ‘portraits’ and ‘text’. Those ‘portraits’ have been ‘observed’, and I take this observation to be the perspective of another (Beatrice Alemagna?) who is not within those ‘portraits’.

I see various images of children in What is a Child? Or is it instead that what I see are ‘portraits’, not children, portraits that come from ‘observation’? To put it another way, the images are framed both as ‘portraits’ in the peritext, and as ‘[c]hild’ (through the question What is a Child?). There is a tension between child and portrait, and one that is not resolved by the idea of observation, the idea that the child is not to be located in the text, but an observation prior to it, or outside its bounds. For the blurb, the child may read the text, and observation has occurred, but the child is not in the text.

If I suggest a certain lack of the child in the text, then the child outside of it (the child of seeming reality) is something other than an independent subject. Here, I am thinking of the idea that

What is a Child? provides ‘a thought-provoking text’. Thought does not come from the child alone, as it is the ‘text’ provoking thought. Moreover, both ‘portraits’ and ‘text’ are articulated with a certain purpose, to help children ‘to consider their own identity’. This ‘identity’ belongs to ‘children’, but ‘children’ and adults seem to be rather passive beings compared to ‘Beatrice Alemagna’ within this formulation. It is the question of framing that is central to my reading that draws me to the peritext, but in so doing, I am also returning to a question introduced tentatively above: is there something in one’s own identity that might require another? Again, it is such a question, rather than any notion of ‘non-existence’, that opens up to me Jacqueline Rose’s notion of the ‘impossibility’ of the child (

Rose 1984).

There is an additional tension arising from a further claim in the peritext that the work is a ‘celebration of what makes every child unique’. However, how can this be if Alemagna is inspiring children to consider their own identity as a child? If there is a sense in which children can be understood to be considering both their singularity as a ‘child’ and whatever additional individual identity they might have, there is a counter sense in which this contemplation is one undertaken by members of a collective. The own identity is considered by an identity haunted by others, and as considered only, there is a sense in which the own identity is independent of the considering party (

Lesnik-Oberstein 2016).

I wish to point out the two moves that problematise the politics of the child. Firstly, that the very move to secure the diversity of the child brings with it the necessity of a unified, and pre-meaningful concept; that there is something required by diversity and meaning that works against both. Secondly, there is something other than the child that helps secure the ‘[w]hat’ of its being: the perspective on the child and its reading, the third that knows it, in however ‘piecemeal’ a fashion.

To bring this introduction to a close, I find it necessary to address the problematisation of the ‘independent subject’ introduced above. Of course, I realise that such a notion is widely questioned in literary and social theory (for selection of texts that would illustrate the diversity of this questioning, see

Foucault 1965;

Derrida 1978;

Copjec 1994;

Butler 1996)

2. My criticism is gesturing toward a specific tendency within contemporary Children’s Literature Criticism that claims to engage with these questioning accounts: I am working within a critical tradition that sees in the work of theory-indebted Children’s Literature Criticism, a resistance to work through the questions of agency and selfhood. I would include theorists such as Jacqueline

Rose (

1984), Sue

Walsh (

2010), Karín

Lesnik-Oberstein (

1994), Neil

Cocks (

2022), and Giulia

Zanfabro (

2017) in this alternative tradition. Due to the modest length of this article, I limit myself to the modest task of responding to the question ‘what is a child?’ in one picture book with reference to the critical work of a single critic. If I were to extend this analysis in a subsequent article, it would be to suggest that Marah Gubar is a particularly articulate example of what, in comments that will be available below, one reader of this present article described as the ‘liberal framing of children’s literature as a field’. Lesnik-Oberstein and Walsh include Karen Coats, David Rudd, and Perry Nodelman among those who perpetuate this ‘liberal framing’

3. Each has criticised the work of Walsh and Lesnik-Oberstein on the grounds that they fail to recognise the reality of the child. Despite calling on Lacan and Derrida, theorists who, in opposing ways, question hard-impacted identities, critics such as Rudd, Nodelman, Coats, and Gubar remain consistently committed to ‘real children’ (

Nodelman 1985, p. 98), ‘actual children’ (

Gubar 2013, p. 451), and ‘referents that are extra-discursive (literally existing outside the text)’ (

Rudd 2020, p. 98). The tradition I am working with, on the other hand, is one that adopts a detailed analysis of narrative perspective and textual framing to question such appeals to the knowable and discrete independent reality of child identity. This counter-tradition has generally appealed more to sociologists and psychoanalysts than to those working exclusively in children’s literature (

Stainton Rogers and Stainton Rogers 1992;

Walkerdine et al. 1984;

Burman 2007). One could trace the tradition back to the work of Phillipe Ariès’

Centuries of Childhood, yet as Lesnik-Oberstein argues, this is not because he is not an early adopter of the claim that ‘the child not to exist’, that claim Gubar argues is applicable to Lesnik-Oberstein and Rose. Instead:

Some of the criticism which has been levelled at Ariès reveals misunderstandings that I wish to avoid from the outset […] neither Ariès nor I am arguing that there were times or places where there were no children […]Ariès makes it quite clear that […] he is not writing about ‘realities’ (whatever they may be seen to be) of states of childhood-dependency or lack of life-experience, but that he is interested in the development of cultural and social ideas of ‘family’ and ‘childhood’ as carriers of social, moral, emotional, and ethical values and motivations. As Ariès states at the beginning of Centuries of Childhood: ‘it is not so much the family as a reality that is our subject here as the family as an idea.

My original intention in this article was not to revisit these arguments. As Rudd claims in a recent critical work on Lesnik-Oberstein, Cocks, and Walsh, the disagreements I am outlining here can seem interminable, and I think it is important not to write simply to shore up existing antagonisms (

Rudd 2020). Therefore, my focus will be on a specific text, through which I aim to push the question ‘what is a child?’ further than, or at least in a different direction to, responses that move away from the kind of non-essentialist, text-based reading upon which the tradition I work with. My interest is in the points at which conventional children’s literature criticises investment in contemporary critical theory, those points at which received common-sensical ideas of a reality that is not up for political contestation reaffirm themselves.

2. ‘Children’ with ‘Ideas’

I wish to tentatively read out the issues introduced through my analysis of Gubar’s quotation through a detailed engagement with

What Is a Child? It is made up of a series of openings, or double page spreads with short sentences on the verso and, on the recto, the pictures—the ‘portraits’ discussed above. For this reason, the openings can be seen to constitute a

pair. In addition, page numbers are not specified for each page. In order to direct my reading, I will refer to each pair (e.g., the first pair, the second pair) in numerical order when making a reference. I would like to begin with the third pair to start my reading (

Figure 1):

The first sentence is about ownership of a single ‘child’. The physical parts of the body are measured as ‘small’, but ‘ideas’ are not necessarily small to the perspective of ‘[a] child’. For that reason, the ‘ideas’ of ‘[a] child’ are different from ‘hands’, ‘feet’, and ‘ears’ (

Figure 1). In the second sentence, the subject expands to multiple numbers of ‘[c]hildren’. They are claimed to have their own ‘ideas’, and the size of ‘ideas’ can ‘sometimes’ be ‘very big’. Although the text is neither from the perspective of ‘[a] child’ itself nor ‘[c]hildren’ themselves, the size of their ‘ideas’, and the frequency of these can be secured. What is particularly striking to me in this formulation, however, is that it is not the ‘[c]hildren’ themselves who ‘amuse the grown-ups’—whatever that might mean—and make them say a word/some words; it is the ‘ideas’ from ‘[c]hildren’ (

Figure 1). In addition, the ‘ideas’ that are not ‘very big’ would not ‘amuse the grown-ups and leave them open-mouthed saying: “Oh!”’. ‘[A]mus[ing] the grown-ups and leav[ing] them open-mouthed saying: “Oh!”’ is conditional on the size of their ‘ideas’. The sizes of ‘ideas’ are either ‘small’ or ‘very big’, as measured as the physicality of a child in the picture and the text (

Figure 1). In this case, even ‘the grown-ups’ are constructed by the other as the reaction is settled: this reaction is invisible in the picture. It remains as if a leftover (

Figure 1).

As the ‘ideas’ are not always likely to be ‘very big’, ‘ideas’ of ‘[c]hildren’ cannot ‘amuse the grown-ups and leave them open-mouthed, saying: “Oh!”’ all the time. If the ideas are not ‘very big’, the reactions of ‘the grown-ups’ should be different from what the book is describing. According to the text, ‘small hands, small feet and small ears’ are not something that will amuse ‘the grown-ups’. In addition, ‘[a] child’ would not be ‘amuse[d]’ by his or her own ideas (

Figure 1). Here, perhaps, the perspective begins to become clear: the extent to which the child is constituted by a perspective other than its own. When ‘the grown-ups’ are ‘amuse[d]’, what they are ‘saying’ is confined to one word, ‘[o]h!’, and this saying occurs when the adults have been ‘left’ by the ideas, further constructing an encounter that is not about an interaction. As there is no sense of what happens after the grown-ups are ‘left’, there is a sense of a condition that is final.

It is worth thinking about the structure of the pages. Although the lack of page numbers is common in picture book texts, here they might be read here to shore up the suggestion that the text is not sequential, and on each page, the portrait is different. This is not perhaps a developmental narrative. We might call upon Painter, Martin, and Unsworth’s division between conceptual and narrative images, with the openings being classed among the former (

Painter et al. 2013)

4. However, my interest is with a slightly different understanding, one that specifically turns on the relationship between the pairs as both isolated and as part of a

series. If the openings might be understood to oppose simultaneous succession or sequential narrative, in what sense can we nonetheless read the text as a whole and as a

continuum?

In this case, there is text on the verso, and the recto has a picture of the child. Each text starts with a capital letter, which stands out among other letters. This biggest letter is in various colours whereas the rest of the letters are black. Although the biggest letters look different from other letters because of their colour and outstanding size, I still read them as text; this is because their font is the same as the other small letters. On the recto, the child is always in a square frame. This frame is different from verso because of the colour; the verso is mainly in white, whereas the recto is not. For that reason, the verso can be read as a big white frame with letters, while the recto can be taken as a portrait (as the blurb describes) with different colours. The child in the recto, therefore, seems to be in a different frame from the text. However, the picture can be read with the text on the left (or the text can be read with the picture), as I have mentioned, in pairs. The two pages continue with different images and texts, but always with the image of a child on the recto and the letters on the verso. However, the pairs are not sequential. These pairs make an omnibus scene or story in What is a Child? Instead, not without narrative, but neither with each opening simply continuing from the last.

What, then, gives the whole continuity? I might argue, the repetition: shape of pages, the same font, the images of the child on the recto, and the ideas related to the child/children. The first point I wish to raise here is that continuity, the continuity of the child, is dependent on a structure that is not the child. What I additionally wish to draw out, however, is the danger that this sense of continuity might be read to work against—that of an encounter that goes nowhere. Framed by a perspective that is neither child nor grown up, the big idea, which is never granted specifics, is understood to be encountered often in the same way: the grown-up is amused, and is known to be amused, but it is additionally left with the perspective knowing that the grown-up’s mouth is opened with the saying of a single word. If the perspective cannot tell what the grown-ups are thinking, or what they mean by this, then their word is included: the grown-ups’ words are included, but there is no sense about what the big ideas were that amused the grown-ups so. The continuity of the scene, its repetition, is thus premised on … nothing. The big ideas are all the same and all, no doubt, unique because they cannot be read. If the scene ends with openness, the adult with the open mouth is rendered speechless. The openness can also be read as a closure, a disconnection to anything subsequent, and an unavailableness.

I will try to answer the question posed by the book by turning to the picture of the child? Let us take a look. I see a hand, but I cannot find any foot/feet (

Figure 1). There are yellow hair and yellow eyebrows. The tongue is pointing upwards, while the pupils are looking downward. One of the fingers seems to point or pick a nostril. There is also a torso and arms in the picture (

Figure 1). What I have read as hair, eyebrow, tongue, pupils, fingers, nostril, torso, and arms are ‘small’. Certainly, one could read irony in the child too big for the frame, and this might relate to what is amusing. One might also claim that, no matter how the child looks, no matter the space they take up on the page, for the perspective, they are all ‘small’. Again, as there is no picture of ‘grown-ups’ on the recto, I do not see someone who is ‘le[ft]’ ‘open-mouthed’ (

Figure 1). Is this because the image is prior to the adults being ‘left’? Moreover, the words ‘they’, ‘[c]hildren’, and ‘the grown-ups’ are all plural, but I only see one child in the picture (

Figure 1). If there are no ‘children’ in the picture, there is also no ‘amus[ing]’. I have mentioned that there are a hand and ears, but I do not see any picture of ‘ideas’. Can the dark blue around the child be the ‘ideas’? (

Figure 1) Here, I am thinking about the claim to the pictures being ‘sensitively observed’, the notion that they are grounded in a visual reality. The uniqueness of the child comes from this idea. The difficulty is that this observation secures the child from a perspective, not its own. Its ideas are what

cannot be seen. However, can they not be seen because they have yet to occur, or because the adult has yet to be inspired to say ‘“Oh”’? Alternatively, is it because what affects the adult is not the child, but their big ideas, and these are what cannot be seen? Here, the perspective on the child is set up as a limit, suggesting something beyond and unobtainable. What is at stake here, first, is the difficulty of securing the child in the image according to the child as it is constructed in the text. The child is constructed in terms of size where the relative nature of size is not secured. The child engages with the adult, but there is no adult; it is the child’s ideas that engage with the adult, but there are no ideas. Or, the ideas and adults, if they are to be read, are constructed in terms of their other. Counterintuitively and following the reading of Elsa in

Frozen offered by Neil Cocks in this Special Issue, I might say: the child picking its nose is its ideas, as what signals their presence in terms of their unavailability of the perspective; the child on its own is the observed child, signaling the absence of the adult (

Cocks 2022)

5. In these terms, how might I resolve the question ‘[w]hat is a [c]hild’? How could I locate the child, or the meaning of the child in the absence of its constitutive absences? If the lack of the grown-up is read as its presence as an observer, how is it to be kept distinct from the ideas that are also present in absence? A text is securing the child against the adult; this might be understood with some issues: an absence here is overdetermined, and it cannot be claimed for one party alone.

3. ‘[S]mall People Who Will Change Some Day’

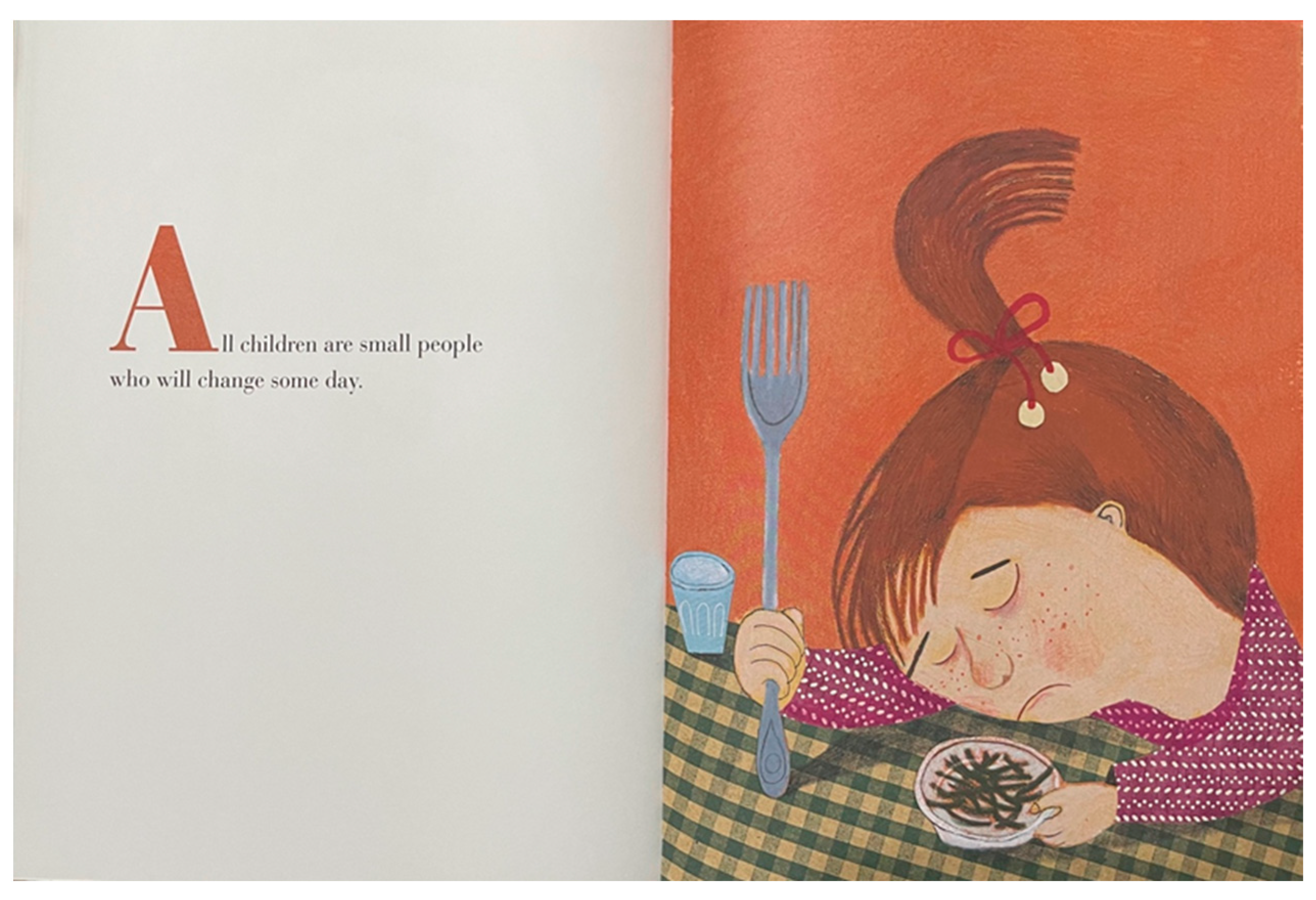

At this stage, I would like to think a little more about the question of size. ‘All children are small people’ according to the fourteenth pair. So here, I will move on to the fourteenth pair to read about the ideas on ‘[a]ll children’ and ‘small’ to see how the children are illustrated by the other person’s point of view (

Figure 2):

‘[S]mall people’ are not stated as all small people, and ‘[a]ll children’ are not all small children, yet ‘[a]ll children are small people’. Without an exception, ‘[a]ll children’ are ‘small’ when they are claimed to be ‘people’. For the perspective, ‘small people’ have not changed yet, but the perspective on ‘small people’ knows ‘small people’ will be different from now ‘some day’. Without an exception, ‘[a]ll children’ will ‘change’. In other words, ‘[a]ll children’ do not remain as they are; they will not, perhaps, be the same ‘children’ in the future. ‘All children’ do not change before ‘some day’: they were not changed before and are not changing now, in other words. The ‘change’ of ‘[a]ll children’/‘small people’ are not claimed by ‘[a]ll children’ themselves/‘small people’ themselves, but from a perspective that is other to them, and knows their fate.

On the recto, there is a picture of a child (

Figure 2). From my perspective, the child is one of the children/small people. Although the child on the picture is much bigger than the letters on the left-hand page, she is still a ‘small’ person, and as she is one of ‘small people’, she has not changed yet (

Figure 2). She will, however, change someday. In this understanding, the word narration constructs the image as limited.

By way of reading the change of a child, I will turn to Sue Walsh’s

Kipling’s Children’s Literature (

Walsh 2010). In Chapter 2 of Walsh’s book, she reads the ‘identities’ of Mowgli, including that of the human child. There, Walsh exemplifies different readings on Mowgli. To help draw out what is at stake in my reading of the change of ‘[a]ll children’, I will read one of the examples about the change of Mowgli and his identity from Walsh’s text:

Something similar occurs in ‘Red Dog’ from The Second Jungle Book where Mowgli goes through a process of re-naming himself over and over again: ‘“Mowgli the Frog have I been,” said he to himself; “Mowgli the Wolf have I said that I am. Now Mowgli the Ape must I be before I am Mowgli the Buck. At the end I shall be Mowgli the Man. Ho.” Here then, each renaming signals difference from a sameness from which it nevertheless originates, and also produces a self that in having more than one guise signals an ambivalence about the relation of the body identity.

Although Walsh does not mention the word change in the text above, there are multiple implications for changes in the reading of Mowgli. ‘Mowgli’ and ‘himself’ in the first sentence are different from each other since it is ‘Mowgli’ who goes ‘through a process of re-naming’, and it is ‘himself’ who has been ‘re-nam[ed]’ ‘over and over again’. The identity of one person has diverged. ‘[R]e-naming himself’ is a process that gives ‘Mowgli’ other names, and it is something to be ‘go[ne] through’; ‘himself’ is part of ‘a process of re-naming’, and it is ‘Mowgli’ who ‘goes through’ this ‘process of re-naming’ ‘over and over again’. For that reason, there could be multiple names for ‘Mowgli’, and according to the ‘sa[ying]’ of ‘h[im]’, ‘Mowgli’ has different names such as ‘Mowgli the Frog’, ‘Mowgli the Wolf’, ‘Mowgli the Ape’, ‘Mowgli the Buck’, and ‘Mowgli the Man’. ‘Mowgli’ is always the same among the various names, but the latter parts of ‘Mowgli’ are all different. ‘Mowgli the Man’ was not his name before, and now he ‘shall be’ that name. The perspective on the saying of ‘Mowgli’ knows what were, are, and will be his names.

For Walsh, ‘each renaming’ ‘signals’ ‘difference from a sameness from which it nevertheless originates’. This ‘difference’ is also another reason why I read the idea of change. The new name, which is ‘renam[ed]’, is always different from its previous name. The previous names became the origin of their latter names, and these previous names were the original names of their latter names once. ‘[A] sameness’ can be read as the origin, but this origin ‘produces a self … having more than one guise’. ‘[A] self’ is not an origin either since it is ‘produce[d]’ by ‘each renaming’. ‘[A] self’ and ‘guise’ are different from each other; ‘guise[s]’ belong to ‘a self’ (in other words, ‘a self’ owns ‘more than one guise’); the number of ‘a self’ is singular, but the number of ‘guise[s]’ is ‘more than one’; ‘guise[s]’ are not only owned by ‘a self’ but also something to be within ‘a self’. In other words, multiple ‘guise[s]’ are included ‘in’ ‘a self’ and this inclusion ‘signals an ambivalence’. According to my reading, the multiple ‘guise[s]’ are one of the origins of ‘Mowgli’ (‘Mowgli the Frog’) and the result of ‘renaming’ (‘Mowgli the Wolf’, ‘Mowgli the Ape’, ‘Mowgli the Buck’, and ‘Mowgli the Man’). Moreover, Walsh develops her argument by claiming that there is the ‘identity’ in the case of ‘the body’, and its singular ‘identity’ can be claimed with ‘a self’ and ‘more than one guise’. (

Walsh 2010, p. 53) The number of ‘the body identity’ is only one, but there seems to be a division between ‘a self’ and ‘one guise’. What is more, ‘a sameness’ yields the ‘difference’ according to Walsh; ‘the relation of the body identity’ yields the change of names such as ‘Mowgli the Wolf’, ‘Mowgli the Ape’, ‘Mowgli the Buck’, and ‘Mowgli the Man’. Mowgli is Mowgli but also not the same Mowgli. He is him and his previous names. It is what I read from ‘difference from a sameness’ and ‘each renaming’. A single person can be announced as

different both in the text that Walsh is reading and what I am reading from Walsh.

There are differences between the fourteenth pair and Walsh’s reading of Mowgli, of course. Mowgli names himself, and the fourteenth pair is less about a sustained and sequential deferral. The two can nonetheless be compared. In the fourteenth pair, I see a single child in the picture, but this can be read in many ways, as I have elaborated in the previous section, and in a sense, I take to introduce a certain problem of identity rather than being simply capacious.

Let us read the child of the fourteenth pair again in another way: the child is holding a fork with one hand and a plate with the other hand; this child is leaning a head against one of the two arms. The cup is near the arm where the head is leaning; the hair is tied up with a red hair band. The child is dressed in violet, and the tablecloth is on the bottom side of the picture—and this is a child ‘who will change some day’; it is the picture of ‘a child’ and ‘a child’ who will not be the same child (

Figure 2). In terms of the child’s changes by reading the picture on the recto, even if the child is holding, leaning, being tied up, and dressed up, the child has not changed yet (

Figure 2). She is a subject of change—the change of the future. The recto can be read to describe her as someone who will change because she is one of ‘[a]ll children’/‘small people’. She has not said that she will be changed, but she

will by the perspective of a child on the text. The child on the recto stays a child, and it is constructed as such by the text on the verso. ‘All children’ and the child in the picture are retrospections because they have stayed as they are and still stay as ‘children’/one of ‘children’; without any change, they will remain as ‘children’ in the text/a child in the picture. Whenever I read this picture, it does not depict the day of ‘some day’. The child will forever be one of ‘[a]ll children’ and one of ‘small people’. Neither the picture nor the text mentions when ‘some day’ will come. The difficulty that interests me here is that the image must be read as one of no change, yet the identity on offer is one that is split: all children are small people. Transformation does not oppose stability. To put it another way, the fixity of what is prior to change requires a division, and thus a deferral.

4. ‘Children’: Always from and by Others’ Points of View

Again, I will read the idea of change by reading another pair in

What is a Child? I will move backwards to an earlier opening. The text in the eighth pair does not directly mention words like changes and metamorphoses within the text. However, I read the ideas of change by reading the description of ‘[c]hildren’ (

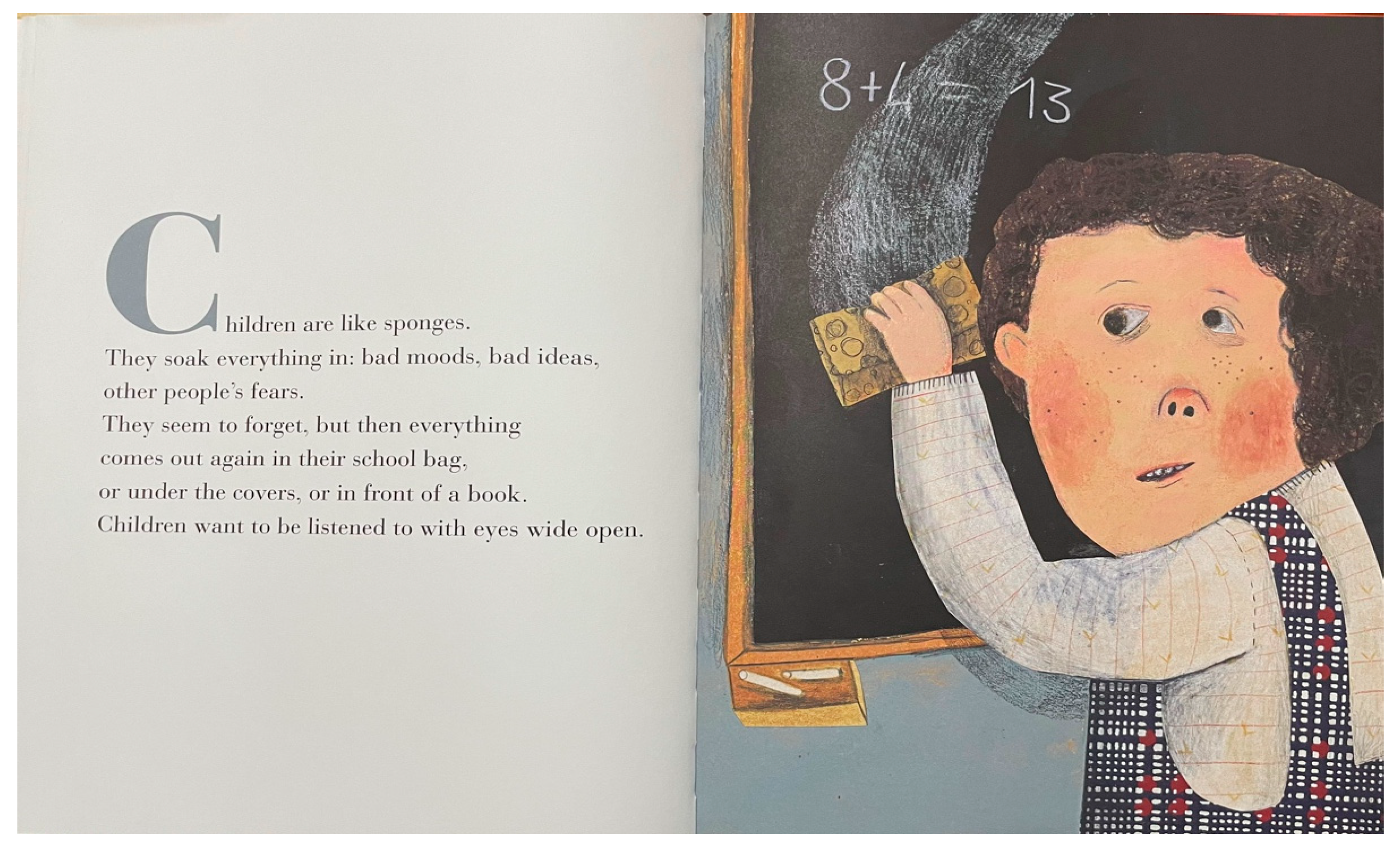

Figure 3):

From this perspective, ‘[c]hildren’ are not ‘sponges’, but they are similar to them (

Figure 3). They are understood in terms of what they are not. The similarity between ‘sponges’ and ‘[c]hildren’ is that they ‘soak everything in’. What interests me is the limit to the child thus constructed: everything does not include children, in so far as everything must be able to be soaked in by them. Thus, a move that might be taken to politically construct a child that is not separate from the world, a child that carries what is ostensibly opposed to it within itself, is tempered by the necessity of separation.

The political difficulty of similes can be further read through the notion of ‘soaking’. It is not that the comparison between children and sponges produces an idea of the children ‘soaking in’ everything, but this soaking is what connects children and sponges. The difficulty is one of the literal. The temptation might be to read the soaking of children as somehow figural against the actual soaking of the sponge, but that is not necessarily the case. This soaking cannot be easily dismissed. In other words, it is read as representative of something else. The precise process of ‘soaking in’ suggests that ‘everything’ is unchanged by the process, the only shift being one of position. Nothing is transformed, and there is a sense that the child remains unaffected by the process. ‘[O]ther people’s fears’, for example, remain the fears of others, not of the child. ‘[B]ad ideas’, too, remain bad. The child has not been swayed. Inside, one might say, is not necessarily intimate to the child but rather a kind of crypt, an inside that is external to the child, a place that remains other.

The relationship between children and sponges can be read further through the image on the recto of a sponge and a child. Are we to read the sponge in the picture as one that soaks everything in (however we might suppose the sponge is actually being used in the image?), and the child in the picture as similar to such ‘sponges’? The sponge is held by a child (

Figure 3). I cannot see how the child can be read to internalise the sponge; thus,

the sponge is problematically outside the notion of ‘everything’. I might read the child in the image as soaking everything in by rubbing the sponge on the surface of a blackboard. However, this needs to be elaborated more; there is a white part that I read as a trace of chalk powder, and there are numbers written on the blackboard (

Figure 3); it seems to me that the chalk powder and the numbers have not fully soaked into the sponge, or, indeed, have soaked at all (

Figure 3): that is not the operation being constructed. Both numbers and chalk powder are not included in ‘everything’ in that sense (

Figure 3). There is an exception or lack of ‘everything’ in the case of a picture.

The sponge in the picture does not soak something into it; it is rubbed by its holder (

Figure 3). The child is holding a sponge, and the yellow sponge spreads out the chalk powder. The equation on the blackboard, the trace of chalk power, the blackboard, and the hand of the child are not soaked into the sponge. The equation also does not show the right answer; it seems that the equation has not been solved in the right way, and the figures are not chosen to be soaked into the sponge (

Figure 3). The equation and the chalk powder are not ‘everything’, which can be ‘soak[ed]’ ‘in’ for that reason.

‘They soak everything in’, but nothing is soaked in the case of the picture (

Figure 3). As the chalk power and equation are all left on the surface of the blackboard, it might not be forgotten. In addition, they would not be forgotten, as I read that they are not included in ‘everything’. ‘Children are like sponges. They soak everything in’, but what I read from the picture is a child who is rubbing a sponge that does not soak something into it (

Figure 3).

A further claim here, of course, is that ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ are not innate in children at first, as they are ‘soak[ed] in’. What is the child prior to the process of soaking in? Is there a pre-socialised identity, a structure that exists prior to soaking? It is a seductive thought, and one that is in keeping with the universalising tendency of the book, but also one that can be read to run counter to an account of the inevitability of socialisation, the openness of the child to the world and the move to work against the notion of the child as romantically isolated and inviolate. However, if there is an unsocialised core to the child, what of its others? Where did the fears of others originate? Again, this is a political question. Is the idea, for example, that these fears—of children, perhaps, but more likely of those who were once children—were also soaked in? Can we trace back fears to a point of origin? Or is this a movement without origin? Either way, there is a conservative notion of emotion to be read, one resistant to change, a circulation of a seemingly a-historic emotion. Counter to this, it might be that others do not function like children. The bad moods and bad ideas are self-authored, and it is this that is taken in by children. However, there is nothing to say that children also do not author their emotions and ideas, only that what differentiates children from others (but not sponges) is an ability to soak in everything.

We recount the problem of ‘everything’. At one stage, there is no limit to what is taken inside. However, it seems to me that there are limits. Is, for example, the narration of the process understood to be included in ‘everything’? This is, after all, a perspective on the ‘[c]hildren’ that knows what is inside of ‘[c]hildren’ and what can be ‘soak[ed]’ into those ‘[c]hildren’. This narration is other than the child. Indeed, the pathos of the child require a perspective on the child that is not its own (likewise, the internality of sponge is known from a perspective on the outside of it). The child, in this text, cannot articulate its own perspective, and that requires a narration whose knowledge is limited to seeming. This grants the child independence; there is something of it that exceeds the narrative frame, yet this excess is a product of the frame. Children are framed as what exceeds the perspective. The child cannot be known on its own terms, as I am guessing that would result in a child alienated from itself. However, the child cannot be narrated on its own terms because the child does not know itself: it seems to forget. It is because of this forgetting that the child must be known by another. However, because of the necessity of external knowledge, the child can only ever seem to forget. The upshot of all of this is, crucially, that there is something. Therefore, the child cannot draw in and absorb the otherness through which it is constructed.

Let us turn in more detail to this notion of forgetting: “soak everything in: bad moods, bad ideas, other people’s fears. They seem to forget, but then everything comes out again in their school bag, or under the covers, or in front of a book”. ‘[B]ad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ are either the memory or an oblivion. Memory and oblivion are conjectured (‘seem’) to be a memory and an oblivion. What is more, ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ are claimed to be the memory and oblivion not because ‘[t]hey’ had claimed so. By the sight (‘seem’) of the perspective on ‘they’, ‘they seem to forget’. Meanwhile, ‘com[ing] out’ of ‘everything’ is not a matter of ‘seem[ing]’. What ‘they’ are doing and how they are different are already known to the perspective on ‘they’.

‘[T]o forget’ does not mean that ‘they’ had forgotten something permanent. This is because ‘everything comes out again in their school bag, or under the covers, or in front of a book’ after ‘forget[ting]’. ‘[B]ad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ would not be lost forever unless they are kept ‘in’ a ‘school bag’, ‘under the covers’, or ‘in front of a book’.

In addition, ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ do not always remain inside of the ‘[c]hildren’; they can be found somewhere ‘in’ or ‘under’ certain places once they ‘come[…] out again’. Even if they ‘come[…] out again’, it does not mean the ‘[c]hildren’ have remembered ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’. What is more, ‘soak everything in’ does not mean the ‘[c]hildren’ do have ‘everything’ (or ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’) inside. The internal/external issues lead to further issues. Here, I am thinking of the way ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’ are repetitive as they ‘come[…] out again’. ‘[E]verything’, which is also restricted to ‘bad moods’, ‘bad ideas’, and ‘other people’s fears’, is related to the matter of positioning. Positions of memory change; the position of ‘everything’ shifts from outside to inside, then to outside. It will be repeated as long as ‘[c]hildren’ are like ‘sponges’. To forget does not mean that ‘[c]hildren’ lose their memories. It is about moving around and reappearing, but oddly, reappearing sometimes remains inside.

Although the perspective on ‘[c]hildren’ (‘Children’ in the last sentence) is not one of those ‘[c]hildren’, it knows what they ‘want’ in detail. The perspective announces that they ‘want’ to be ‘listened’ to. There is an addition (‘with’) of ‘listen[ing]’, and then they are ‘listened to’. ‘[L]isten[ing]’ to the ‘[c]hildren’ is related to the ‘eyes’, and these ‘eyes’ are not the eyes of ‘[c]hildren’. The ‘eyes’ have to be ‘opened’ ‘wide’ when the ‘[c]hildren’ are ‘listened to’. The number of ‘eyes’ in the last sentence is plural. Would someone with no eye or one eye not fulfil the wishes of the ‘[c]hildren’? In other words, someone who is not with multiple ‘eyes’ and who cannot open their eyes particularly ‘wide’ do not satisfy the condition of ‘eyes wide open[ing]’. To satisfy what the ‘[c]hildren’ want is conditional on the physical state. The irony is that the ‘[c]hildren’ do not know what has been listened to. Being listened to is what they want, even if they do not know what has been listened to.

If ‘[c]hildren want to be listened to with eyes wide open’, it does not mean that these ‘eyes’ necessarily look at the ‘[c]hildren’. There is an openness to the child but also the possibility of not seeing it. Here, I could also call on the reaction to ‘big ideas’ in the third pair I discussed initially; ‘the grown-ups’ say only a word (‘“Oh”’) with opened ‘mouth[s]’, and this cannot be regarded as a communication between the ‘[c]hildren’ who have ‘very big ideas’ and ‘the grown-ups’. There is a repetition of openness across the open mouth and open eyes. However, this openness in some sense is not engaged with the child, as there is a possibility of not seeing and not communicating. What is more, the openness from adults needs a child. If this can be understood in terms of openness to the other, it also requires a child of independence and separateness. The child as other, an otherness that is known to always be such from a narrating perspective. Politically, the child must maintain its independence, even as the adult removes any cynical or arrogant barriers between them. Openness separates. What I am circulating around here is a certain doubleness to the child, necessary for its independence, a notion of childhood that requires the question of its being to be posed and answered endlessly in the text. A child who is known and also not known.

The reading above is premised on an understanding of the text as isolated pairs, yet as pairs that are nevertheless caught up in a deferral of meaning. This is not the only way to approach this text. An alternative reading might return the three pairs discussed to their sequence within Alemagna’s text. A conventional reading of the text will begin by opening the third. Then, the eighth with the notion of not changing before meeting the fourteenth. The force of this argument is that the text does not finally stall but suggests a range of different encounters that result, or at least indicate, that it will come at some point. The counterargument, as I have suggested above, is that the individual pairs can be read to work against that sequence. The sequence that I am trying to show in this paper is more about a certain structural repetition

6.

5. Constructing as Known: The Child as Impossible

I wish to conclude by reiterating some of the challenges to answering the question, ‘What is a Child?’ in Alemagna’s text, by indicating several difficulties in getting rid of the impossible condition of childhood and gaining a more certain knowledge of the child itself.

Let us begin with the difference between the construction of the child in the back cover blurb and the third pair. In the former, ‘every child’ is claimed to be ‘unique’, a ‘unique[ness]’ to be ‘ma[d]e’ from ‘this beautiful celebration’ by ‘award-winning author Beatrice Alemagna’. For that reason, the ‘unique[ness]’ of ‘every child’ is not innate to ‘every child’, and it is not made by ‘every child’ him/herself. The ‘unique[ness]’ in the back cover is from a single person, the author with a specific name and work experience. However, in the case of ‘every child’, the name, occupation, and other details are not specified, and thus, no matter who the ‘every child’ is, they are ‘ma[de]’ ‘unique’ by the other. This makes me think: if there were no name of an author who had published a bestselling book, would there be uniqueness?

Might it be, then, that the child in the picture represents the uniqueness forwarded by the blurb? Being ‘unique’ is defined in a certain way with a text and picture in this case. Is not the word ‘unique’ already confining the uniqueness of the children/child? Why does ‘every child’ have to be made as such? ‘[E]very child’ is influenced by something and constructed as a result. In what sense is it unique? I would think back to the various elements, such as fonts, colors, the openness from grown-ups, and the formation of the two pages that are repeated within the frame of What is a Child? Although the continuity that I have read from the book is not the child him/herself, it is necessary for the construction of the child. For that reason, I would have an identity as fragmented, even meaningless. Each pair in What is a Child? is different, or even—‘unique’: we are introduced to a variety of individual children. However, as the pairs are still pairs, they are part of a continuum. From now on, I might return to the Marah Gubar quotation with which this article began, where the claim might be formulated: “of course childhood is a problem, and is not secure as a concept, thus we should look to individual children, or specific instances of childhood”. Gubar emphasizes the uniqueness or singleness of either ‘children’ or ‘childhood’, but, as read above, this ‘individual’ is related to the group, ‘children’ and ‘childhood’ to multiple ‘instances’. Likewise, the pairs can also be read as unique but also as the whole. My interest is in how the structure of the pair is bound to the identity ‘child’. Put simply, this identity, its sense of being an instance of a category, its repeatability, requires a structure of continuum that is not synonymous with it: ‘child’ cannot be secured in What is a Child? independently of the text’s structure, but this structure is other to the child. A child is constituted by something in excess of it.

A further difficulty with the notion of a child as independent is that a child does not have his/her own perspective in What is a Child? A child is announced, defined, depicted, and framed from beginning to end. ‘[E]very child’ is ‘unique’, but how can a child be unique without his/her own perspective? Again, there is an otherness necessary for the child. Thus, the image of the child does not include everything that the text calls upon to answer the question, ‘[w]hat is a [c]hild?

The child in the text is inconsistently constructed: image and text offer different understandings. If I were to single out one claim, it would be that, according to the back cover blurb, there are no children in the images: the pictures are the ‘portraits’, apparently presumably of real children that are not included in the images. This claim introduces a division between child and portrait, and between absence and presence, reality, and representation. Such a division could be read from the question (‘what’/‘a child’): the pair (the text in the verso and picture in the recto), transformation (the child of now and ‘some day’) but also uniqueness (child against children) and structure (the repetitious structure required for the child to be figured as ‘children’). Lastly (at least in this brief summation), the children or a child are separate from the grown-ups, yet, as with all the divisions we might call upon, this is compromised: both the child and grown-up are figured in terms of absence at one stage. For example, the absent grown-up can be read in terms of the framing perspective necessary for the child. A child, I would suggest, is as an antagonistic category, rather than a ‘capacious’ category with ‘fuzzy edges’, ‘impossible’ not in terms of its absence or non-existence, but in the sense that it is other to what it is at certain stages, its uniqueness—its specificity or instance—never isolatable outside a chain of meaning that touches identities that should not come within its reach.

I wish to conclude here with the question of knowledge, a question necessary for the question this article has turned upon: ‘[w]hat is a [c]hild?’. I have argued that the openness to the child in Alemagna’s text requires a certain closure: the notion of the child as independent, with this requiring a limit on the adult investment in the child. However, what are the politics of knowledge at work here? To begin to answer, I will return for a final time to Marah Gubar’s quotation:

It does not follow that the designation “child” has no meaning, that we cannot know anything about the lives, practices, and discourse of individual children from different times and places. Similarly, in order to expand our knowledge of children’s literature as a whole, the best approach we can take is to proceed piecemeal, focusing our attention on different subareas and continually striving to characterize our subject in ways that acknowledge its messiness and diversity.

In the name of ‘knowledge’ or ‘approach[ing]’, ‘children’s literature’ is taken to be ‘our subject’. The knowledge of children and children’s literature is all expansive. However, because they are accumulative, they resist the dead-ends and antagonisms of impossibility. This ‘expansion’ is about ‘positive’ knowledge, but it is also related to the ‘messiness and diversity’. ‘[M]essiness and diversity’ do not challenge knowledge because they are the known truth of the subject in question. On the other hand, there is knowledge that is owned, and must proceed through subjectification. One might say that there is the knowledge that is only ever something ‘about’ that which is ‘of’ children, and another more direct, ‘positive’ and expansive ‘knowledge of’ children’s literature, and these are read as ‘similar’. To ask what is a child?, we should be interested in thinking through these and other tensions and in problematising constructions of similarity, sameness, and difference.