Abstract

Recently, scholars have looked at the ethnic press through a social constructionist lens, examining the process through which immigrants developed a sense of identity and the role of print culture in forming “imagined communities” (Anderson). Here, I analyze the coverage of the 1909 assassination of police Lieutenant Petrosino in both mainstream and Italian-American press and popular culture. This shocking event ignited a debate over the nature and origin of the Mafia and the dangerousness of the Italian community, a debate involving discourses of racial difference, immigration restriction, and the capability of Italians to assimilate. This debate became an important arena in which Italian immigrants defined themselves and their place in America. Italians were represented predominantly in the context of criminality, so immigrant writers constructed their own counter-representations in newspapers, re-coding stereotypes and negotiating a collective Italian-American identity. In the press, Petrosino became a contested symbol: on the one hand, of the rhetoric of the inclusiveness of the American melting pot and, on the other, of the possibility of redemption from the discredit that the actions of a small minority threw on the whole community.

1. Introduction

On 12 April 1909, one of the largest funerals in the history of New York City took place. Seven thousand people were part of the procession, including nearly two thousand policemen and firemen, an honor guard, “Mayor McClellan, Police Commissioner Bingham and nearly every official of prominence in New York city” (To Guard Body of Policeman 1909), and 250,000 lined the streets to pay their respects to Lieutenant Joseph Petrosino of the NYPD, killed in the line of duty while in Palermo, Sicily, on a mission against Mafia and Camorra. That an Italian immigrant from near Naples should be granted a state funeral that was almost as big as Abraham Lincoln’s,1 “a funeral such as it accords only to heroes”, with “mounted police and guard of honor,” is quite an extraordinary fact (Moses 2015, pp. 148–50; Funeral of Petrosino 1909). Petrosino’s murder on 12 March had shocked the public and ignited, in both the mainstream and Italian-American press and popular culture, a debate over the nature and origin of the Mafia and the dangerousness of the Italian community. This debate over the emergence and the nature of the Mafia in the US became an important arena in which the struggle of Italian immigrants to define themselves and their place in American society took place. In this context, the Italian-American policeman became a contested symbol: on the one hand, he embodied the greatness of the American system of “good government and law” (Petrosino 1909) and the inclusiveness of the American melting pot—one in which an immigrant of even the lowest sort, an Italian, could come to stand for the values of American justice and courage, not only for his community but for all Americans—and, on the other hand, he represented the possibility of redeeming the Italian-American community from the discredit that the crimes perpetrated by a small minority brought upon it.2 The stakes of this public debate over the relationship between Italianness and criminality could not have been higher as the possibility of successfully negotiating an Italian-American identity itself, along with the affirmation of the capacity of Italians to become part of the American polity, were put in question.

2. Background and Methodology

Today, of course, we can recognize that Italians have been incredibly successful in their integration into American society and culture; besides their prominence in many different areas of American popular culture, in real terms, ordinary Italian Americans have, as Gabaccia notes, progressed so far that they “no longer differ in education or socioeconomic status from other urban Americans of European descent” (Gabaccia 2010, p. 33). However, such integration was neither smooth nor easy. Although Italians, under the 1790 Naturalization Act, qualified as “free white persons” and legally had access to naturalized citizenship3 and political participation, unlike African Americans, Asians, and Mexicans, in the early days of Italian mass immigration (1890s–1920s) the reality was different as the status of Italians as prospective Americans was very much in doubt. Their whiteness as Europeans was put into question as, in those years, in public discourse and even in the Congressional record,4 they were often placed in an in-between, “dark white” category (Roediger 2003). This narrower differentiation within whiteness was brought about by the anxiety that the massive influx of “swarthy” Catholic and Jewish foreigners from Southern and Eastern Europe caused in the native population. Whiteness was no longer a monolithic category, diametrically opposed to the category of “colored, ” which in the formulation of the 1790 law had helped maintain the cultural homogeneity of the predominantly Protestant, Anglo-American population and guaranteed fitness for self-government, but “became fragmented into an array of racially inflected ‘national types’” which were considered inferior and unfit for self-government (Coladonato 2014). In 1907, the Dillingham Commission was established by the Congress to investigate different immigrant groups and the phenomenon of mass immigration with an eye toward restricting the entry of less desirable types. Its most significant report, entitled A Dictionary of Races or Peoples (1911), officially defined a hierarchy of races in which European national groups were included in a “hierarchical scale of human development and worth” (Jacobson 1998, pp. 77–79).

As we can see in this influential text, Southern Italians arrived in America with previously established racial baggage from Italy. The Dictionary based many of its racial claims about Italians on the ideas of post-unification Italian positivist sociologists such as Sergi and Nicefero (citing them by name) which placed Italians themselves in a binary structure divided into categories of Northern/Southern, Alpine/Mediterranean, Hamitic-Semitic/Aryan, in which the negative term of comparison for constructing this hierarchy of races was Africa. In these theories, Africa was used as a metaphor for primitiveness and atavism and, consequentially, all those characteristics that were attributed to Southern Italians, such as laziness, “little adaptability to highly organized society, ” and lack of impulse control leading to crimes of passion and violence, were represented as an inheritance from their racial and geographical proximity to Africa (United States Immigration Commission 1911, p. 83).5

Arriving in the US, they also encountered racial dynamics in which African-Americans were a point of reference for defining whiteness (by opposition). As Vellon (2014) very convincingly argues, in the initial period of immigration (1890–1910), the strategy used, especially in Italian newspapers, to construct and elevate their group identity in the eyes of Americans was that of celebrating the long history of Italian civilization and the contribution of Italians to building America. However, this was followed by a period (1910–1920) in which they realized that their claim to being likely candidates for Americanization would be more effective if it were based upon whiteness, which became the central basis for their claims to assimilibility, and previous criticisms of white violence and discrimination against African Americans and Asian Americans which, for example, had characterized their commentary of lynchings in the early period, were largely abandoned.

Against this background, much early discourse on Italian immigration insisted on the impossibility of their integration due to certain “inherent” racial and/or cultural characteristics that rendered them incompatible with American values and practices. The biggest obstacle to the integration of Italian immigrants was certainly their widely alleged “natural” tendency to crime, which came to dominate early representations of Italian immigrants in the American mainstream press. My recent study argues that, while beginning from the 1890s “Italian immigrants were systematically (and almost exclusively) represented in relation to the Italian Mafias by the American mainstream press,” it was in this discursive field that many immigrant writers sought to construct their own representations. Indeed, “the Americanness of Italian Americans that is taken for granted today was the product of a long discursive struggle carried out, in this early stage, primarily in the Italian-American press as it sought to construct counter-discourses of identity to combat the sinister, racialized representations of the mainstream press of the day” (Cacioppo 2016, p. 55) and to renegotiate their racial status (Michaud 2011).

By focusing the analysis specifically on representations of organized crime and law enforcement, both in the mainstream and Italian-American press and popular culture, we can use the discourse of Italian criminality as an interpretive frame through which to examine the broader processes of negotiating and constructing Italian-American identity. On the one hand, news coverage in the yellow press, feature articles on Mafia, Camorra, and Black Hand in mainstream papers and illustrated magazines, and popular detective libraries (inspired by real Black Hand crime stories) depicted Italian criminality with a discourse resting on a substrate of eugenicist assumptions that Italians were naturally inclined toward criminality and, therefore, unable to conform to the strictures of American law, incapable of successfully integrating and participating in American civil society. In contrast, counter-representations published in Italian-language newspapers and serialized detective fiction (for example, in Bernardino Ciambelli’s works; see (Cacioppo 2005) focused on highlighting the disparity between the law-abiding majority and the criminal minority within the Italian community, utilizing discourses of victimization which argued that the community was not only victimized by organized crime but also by the neglect of institutions, especially the police. Indeed, the emergence in both fiction and journalism of the myth of the Italian-American detective as a tough and honest hero, epitomized by Lt. Petrosino, coming from within the Italian community yet representing American law, functioned precisely as another brand of counter-narrative combatting representations of Italians as criminals.

The racially charged representations characterizing this early debate, which have often been overlooked by scholars of Italian American culture and the Italian Diaspora, are important because they shed light on the way in which, in this early period, discourses of Mafia and race were inextricably intertwined. A detailed study of these representations and counter-representations will contribute to drawing a “clear picture of the entanglement of Italian Americans in American racial issues” (Giunta and McCormick 2010, p. 17), adding a new dimension to the study of Italian American history in which emphasis on this rough beginning, marked by discrimination on the basis of race, moves further away from the traditional model of straight-line assimilation and the notion of the inclusivity of the American nation that dominated conventional history in the past.

Regarding issues of race, contemporary historians such as Noel Ignatiev (1995), Matthew Frye Jacobson (1998), David R. Roediger (2005), David A. J. Richards (1999), Guglielmo and Salerno (2003), Thomas Guglielmo (2003), and Peter Vellon (2014) have directly addressed the question of whiteness in their discussions of European and Italian ethnicity, acknowledging that, during the period of mass immigration, European immigrants were differentiated and mapped onto a hierarchy of “white” races according to their socio-political status as well as their perceived proximity to whiteness. However, while Thomas Guglielmo argues that Italians, even though racially discriminated against, were considered “white on arrival” (both in their own consciousness and by the native-born), Jacobson, Roediger, and Vellon argue that Italian Americans, in the period 1890–1920, moved from an in-between state to white. A number of documentary histories of Italian-American discrimination, such as the work of Richard Gambino (1996), Salvatore J. LaGumina (1999) and Joseph P. Cosco (2003), have focused on mainstream American culture’s perception of Italians, examining external representations and stereotyping (including associations of Italian Americans with Mafia and organized crime). However, the relentless work of self-representation produced by early Italian-American communities continues to be undervalued and understudied. Although scholars such as Francesco Durante (2001, 2005) and, to some extent, Martino Marazzi (2000; Marazzi and Goldstein 2004) have rediscovered and made available a wealth of archival literary and cultural texts from the early phase of the Italian-American experience, these texts have not been explored in depth in relation to their role in Italian-American self-representation in the face of overt hostility from mainstream culture and its expression in the press.

Previously, I have analyzed Italian-American autobiographies and popular detective fiction as sites in which a self-conscious ethnic identity is constructed and negotiated (Cacioppo 2005). The present work continues this emphasis on uncovering the internal perspective of the Italian-American community and remains focused on issues of self-representation, but my analysis shifts from works of fiction and autobiography to the Italian-American press, which played a vital role as a site of dialogue and debate with representations in mainstream journalism and other publications. While the importance of the Italian-American press has always been acknowledged, from Robert E. Park (1922) to Rudolph Vecoli (1998), the first in-depth study emerged only in 2014 with Vellon’s broad work on the representation of race, class, and identity in the early Italian-language press. The present article expands on an earlier work (Cacioppo 2016) which adds to the existing literature on the Italian-language press, representations of Mafia, and the construction of Italian-American identity by looking at the Mafia stereotype as a manifestation of the “precarious racial position” (Vellon 2014, p. 2) of Italians in the US at the turn of the century, with the press providing the venue in which discourses of racialization and identity construction converged.

This previous work analyzed specific events related to Mafia and/or criminality in a “horizontal” perspective, examining different sources from both the mainstream and Italian-American press that contemporaneously discussed these events, in order to foreground the debate among them regarding issues of race, criminality, and identity. It identified a series of symbolic violent incidents which received extensive coverage in the press from various points of view which used these events to promote particular political and/or ideological aims. This work discussed two early nodal events around which representations of the relation between Italian immigrants and organized crime clustered: The New Orleans Massacre of 14 March 1891,6 and the Barrel Murder in New York on 14 April 1903.7 The former brought the association between Mafia and race to a national scale for the first time (Jacobson 1998, p. 56), while the second was represented as proof that organized crime had penetrated the fabric of urban America. Here, I concentrate on the assassination of Lieutenant Petrosino in Palermo in March 1909, an event which was perceived and depicted as confirmation of the transatlantic reach of Italian organized crime and its potential to subvert American institutions. The ensuing debate, in both the mainstream and Italian-American press and popular culture, focused on the nature and origin of the Mafia and the dangerousness of the Italian community. Significantly, it intersected with discourses of racial difference and immigration restriction, raising questions about the ability of the Italian element to assimilate and Italians’ compatibility with the values and social practices making up the fabric of American society.

3. Representations in the Mainstream Press

The news of Petrosino’s assassination was first published by the New York Herald on 13 March and officially confirmed by a cable to Commissioner Theodore A. Bingham from the American Consul in Palermo on the morning of the same day: “Petrosino shot, instantly killed, heart of the city, this evening. Assassin unknown. Dies a martyr. Signed Bishop, Consul” (Petrosino, Mortally Wounded 1909). Little other detail arrived from Sicily for a while and, in the days following the assassination, newspapers tried to fill in the details despite having little reliable information, as is shown by the numerous inaccuracies, incongruities, and contradictions in the different accounts. For example, it was first reported that he had had a gun and fired back at his killers (Petrosino, Mortally Wounded 1909), but then it was recounted that he had been unarmed. Newspapers did not have much to go on, and so their pages and special sections were filled with articles eulogizing Petrosino as a “martyr” and as the best policeman in New York (Blackmail and Murder 1909; Career of Petrosino 1909; Petrosino a Terror to Criminal Bands 1909), explaining his mission to Italy (Mission That Took Petrosino to Italy 1909), the phenomenon of the Black Hand (Woods; Black Hand Peril 1909), and the origins of Mafia and Camorra in Sicily and Naples (A Review of the World 1909; The Camorra, the Mafia 1909). In addition, there was a flurry of generic newspaper and magazine articles reporting on the “growing” threat of the Black Hand (White 1909) and how Italians were Undesirable Citizens (1909) while eulogizing Petrosino and condemning the Black Hand as America’s archenemy.

The assassination of Petrosino rekindled a debate over the problem of Italian criminality, which was already present in the newspapers, often clustering around the news of major Italian crimes. By 1909, the American public had become very familiar with Italian crime through the sensational journalistic accounts of famous cases, such as the aforementioned New Orleans massacre (1891) and Barrel Murder (1903). In 1909, the editorialist Francis J. Oppenheimer of the National Liberal Immigration League (who believed that the Black Hand was a myth created by the press), stressing the proliferation and amplification of the Black Hand news in the press, noted that “a day scarcely passes without some mention coming up in the news of the misdoings of the Black Hand Organization. Either it is a ‘Black Hand Robbery,’ or a ‘Black Hand Kidnapping,’ or a ‘Black Hand Dynamiter.’ Sometimes it is even a ‘Black Hand Murder’!” (Oppenheimer 1909). Crimes involving Italians (either as perpetrators or victims) were increasingly categorized under the heading of Mafia or Black Hand, whether they were related to these criminal bands or not.8 Thus, the press was creating what has been called a “news theme,” a category under which everything Italian could be subsumed and then explained in terms of a broader idea (Lombardo 2010, pp. 162–63; Kappeler and Potter 2006, pp. 3–5); in this case, the explanatory frame was the newly emergent eugenics theory which held that crime was the result of certain characteristics of the offender and thus tied to essential, innate, hereditary traits of a group: in a word, tied to race. Through selective reporting and distortion, newspapers were contributing to racializing Italians and constructing them as a social problem, while the focus on and amplification of the organized crime “theme” kept their audiences interested. The Italianness of Italians was becoming increasingly identified with their alleged tendency to crime, and “Mafia” became a unified, totalizing narration which could entirely explain Italians in terms of the early positivist theories of deviance.

Particularly virulent and sensational images characterized the representations of Italians found in the popular press, the so-called “yellow papers” (such as Bennett’s Herald, Hearst’s New York Journal, and Pulitzer’s World) and magazines (such as Puck, Judge, Munsey’s, McClure’s, Collier’s, and Life) which, exploiting the growing wave of xenophobia that followed the mass immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe—which made the topic of foreign crime very popular—constructed the acts of a small group of criminals as the work of a massive international organization, creating the myth of the Mafia spanning across two sides of the ocean, a foreign conspiracy attacking American institutions, especially those supporting law and order, from the inside. For many newspapers, the assassination of Petrosino was simply the final proof of the overarching, corrupting power of Mafia, as we can see in this headline from the New York American: Petrosino Slain in Italy on Sentence of New York Black Hand (1909). The idea of an institution with its own government and its own tribunals, which acts across two continents, is clearly suggested here.

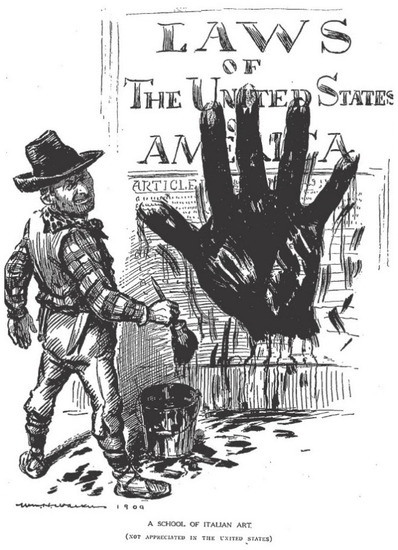

Petrosino’s death resulted in a particularly heightened perception of the growing threat posed by Italians in America (White 1909). The assassination was constructed as an organized attack carried out in a foreign land on a representative of American Law and Order; it was thus perceived as an attack on America itself carried out by a “conspiracy of foreign criminals” (The Massacre at the Parish Prison 1891). The image of a tentacular organization which (branching out from Sicily to America) has the power to infiltrate and potentially corrupt and threaten the American system of Law and Order is crystallized, for example, in a cartoon which featured in Life magazine less than a month after Petrosino’s assassination (“Illustration 12—A School of Italian Art”; Figure 1). Here, a gigantic black hand painted, not very artfully, by a bandit-like character (with stilettoes hanging from his belt) literally taints a page of the American legal code. The caption, “A school of Italian art (not appreciated in the United States)” points to the fact that the Italians in America were not people with a natural inclination toward art and beauty, the descendants of Michelangelo and Raphael who had made Italy famous and who are appreciated around the world, but rather a lineage of criminals posing a threat to America. The cartoon substitutes the old (and relatively benevolent) stereotype of Italians as artists with that of Italians as delinquents recasting all things Italian in terms of an overarching “theme, ” that of Mafia.

Figure 1.

Life Magazine, 1 April 1909.

The ideological background which supported this shift towards the racialized representation of Italians was that of the rise of eugenics as a way of reorienting discourse surrounding the debates on immigration which had begun at the turn of the century.9 Under the influence of the pseudo-scientific theories of Positivism and Social Darwinism, the concept of race expanded to also encompass nationality, so Italians and other Europeans were characterized as races which could be identified by fixed, immutable, hereditary characteristics and thus organized into a taxonomy of peoples in which one’s race was the prime determinant of one’s behavior. Since races were considered immutable, elements of social inadequacy would not melt. Moreover, mixing races with elements that were too different or those presenting various traits of social inadequacy (including criminality) would not lead to the improvements promised by the melting pot but rather to “race suicide”, to an ineluctable tendency toward decline amongst the multiracial elements (Ross 1901).

In line with this emerging eugenics approach to issues related to immigration, the problem of Italian and, in general, foreign crime was “reconceptualized in biological terms and represented as a manifestation of the inevitability of race” (Wong 2006, p. 61), reducing its etiology to the simple fact that bad people came from “bad provinces” and needed to be stopped by limiting immigration from those areas, rather than seeing immigrant criminality as part of a more complex social problem. Indeed, such a theory easily dovetailed with the theory of a conspiracy of foreign criminals menacing the nation from the outside which had arisen and circulated in the wake of the New Orleans massacre (Lodge 1891) and acquired strength with the assassination of Petrosino. It was certainly a more convenient explanation for rampant foreign crime than acknowledging the ineffectiveness of the police and corruption in the municipal government which was, in fact, the structural force which permitted its existence (Lombardo 2010, p. 163).

These ideas, represented from an institutional point of view by the Immigration Restriction League and the investigations of the Dillingham Commission, had penetrated so deeply into society through newspapers that, reacting to Petrosino’s assassination, even a historically pro-immigration periodical such as Hamilton Holt’s The Independent—a traditionally liberal weekly which, in the past, had supported the causes of abolitionism and women’s suffrage, especially under the editorship of Henry Ward Beecher (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother), and which, in 1909, under Holt (1897–1921), was a strong advocate of immigrants’ rights—deployed the rhetoric of the “bad provinces”, ascribing the blame for Italian criminality to a matter of faulty biology because, of course there are good Italians, “but here in this country the multitude of people that have come from the ‘bad provinces’ of Sicily and Southern Italy have, by the percentage of criminals, cast discredit on the whole nation” (Petrosino 1909).

As Wong notes, “the stereotype that Italians were more prone to criminality and required strict surveillance and policing became increasingly common” (Wong 2006, p. 121), as can be seen in this article published after the assassination by Arthur Woods, the Deputy Police Commissioner of New York City, who deployed a rhetoric of primitiveness to characterize Italian immigrants and propose a solution to Italian crime:

We are trying to deal with medieval criminals, men in whose blood runs the spirit of the vendetta, men who have been used to arbitrary police measures and unfettered prosecutions, and we are trying to handle them by a legal and judicial system that heretofore has not been called upon to meet this sort of situation.(Woods 1909)

Assertions like this one that, going back to Italian positivist sociology, saw the alleged criminal tendencies of Southern Italians as directly descending from their racial proximity with the more “primitive” African races, clearly declared that Italian criminality was of a fundamentally different nature than American criminality--in that it was determined by innate qualities rather than moral agency--and that the modern, enlightened American legal system was incapable of dealing with such atavistic primitiveness. This idea even led people to advocate for the removal of certain constitutional rights for these people. For example, The Evening Sun, in a sensational five-column article entitled Black Hand Peril (1909) suggested suspending the fundamental right to the presumption of innocence as the only way to deal with such primitive, callous people, advocating that the burden of proof be put on them rather than the state, thus implying that they were all potentially guilty. This rhetoric of difference and primitiveness spilled over into popular culture, showing how pervasive these views were in society, especially in the wake of Petrosino’s murder. A review of the first American performance on 6 April 1909 of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s pastoral drama, La Figlia di Iorio by a well-known Sicilian company, which was a success on Broadway, expressed sharp criticism. The play itself is described as “brutal, gruesome and primeval,” “too violent for our well-manicured tastes,” too violent to be tolerated by an American audience. But what shocked him the most was the style of acting: “All these Sicilian actors seemed to be impelled by the ferocity of their temperament to do exactly what they did. None of the tricks were the melodramatic tricks that we know. It was all completely different” (Mimi Aguglia’s ‘Iorio’ Quite a Shock to Bowery 1909; emphasis added).

While in the various feature articles and editorials on Italian immigration and crime the mafiosi and Black Handers were Italians who remained attached to their primitive, atavistic culture and refused or were incapable of assimilating or embracing American culture and values (The Camorra, the Mafia 1909), Petrosino was portrayed as the exact opposite: “He died a martyr to good government and law”. He had absorbed the values of American justice, and he represented them not only for Italians in America but for all Americans (Petrosino 1909). While the Black Hand is the symbol of the risks of unrestrained immigration, Petrosino is the symbol of successful assimilation, and many papers cast his life story into the format of the American success story. (Career of Petrosino 1909). While working as an overseer of garbage collection on the Manhattan riverfront, which at the time was under the Police Department, the young Petrosino was noticed by Police Inspector Williams for his intelligence and hard work:

“Why don’t you join the police force?” asked the inspector. This opened up a new life to this young alien, a native of Padula, Province of Salerno, who had come to this country eight years before with little money and almost friendless.(Petrosino a Terror to Criminal Bands 1909)

His slow but steady rise through the ranks, from patrolman to sergeant and on to lieutenant, was attributed to hard work, dedication, and ingenuity. His deep knowledge of the entire Italian community, including its criminal underworld, which “was like an open book” to him, made him the perfect candidate to run the Italian Squad, a special unit of Italian policemen dedicated to ferreting out Italian crime. He is described as being able to penetrate “the inmost secrets of the back rooms of Mulberry, Mott and Elizabeth streets, those of the 12th street Little Italy and the newer Italian section on the east side of Harlem” (Career of Petrosino 1909). It is his insider knowledge and ability to blend in with the local criminal environments, together with his modern investigative techniques and use of physical evidence, that are portrayed as enabling him to solve many difficult cases. Most of all, what the press emphasized was Petrosino’s courage, incorruptibility, and single-minded commitment to justice, even going so far as to exonerate the innocent and save them from execution in the electric chair. In short, with a record of 500 convictions and 100 deportations, “he was the greatest detective that New York police ever had, honest brave, shrewd” (Petrosino 1909; Murder of Detective Petrosino 1909).

But while his life was made into an exemplary tale of successful immigration, with his Italian culture harnessed in the service of American Law and Order, his mission to Italy which ended with his death was instead constructed as a cautionary tale, a warning of the dangerousness and far-reaching power of Italian crime, a warning that free immigration had to be stopped.

The objective of his mission was to obtain the penal certificates and birth records of criminals who had illegally immigrated to the United States so that they could be positively identified and deported, taking advantage of a law approved by Congress in 1907 which allowed the deportation of criminals within three years of their arrival. In order to attain this objective, as suggested by Professor Jeremiah Jenks, a member of the Dillingham Commission, a man would be sent to Italy to establish a collaboration with the Italian authorities. The plan, which was expected to be extremely effective at “stemming the tide of criminal immigration to this country from Italy”, arrived on 7 November 1908 in a letter to Police Commissioner Bingham, and it was based on the premise that most Italians were law-abiding citizens but that almost all Italian criminals in the United States had already been criminals in Italy and had escaped to America in order to evade the harsher control measures permitted under Italian law (Mission That Took Petrosino to Italy 1909). Indeed, this idea was consistent with what Petrosino himself had held about crimes committed by Italian immigrants in a famous interview in the New York Times in 1908, in which he asserted that “there is no big central organization of criminals called the Black Hand”, but only small opportunistic bands of malefactors who could be stopped from entering the country with stronger pre-immigration controls (Blames Immigration for the Black Hand 1908).

But Petrosino’s assassination in the line of duty, besides elevating him to the status of a martyr or a sort of secular saint, was used to paint a much darker picture than that he himself had described, one that pointed to a much more pervasive and dangerous phenomenon with international ramifications, growing numbers, and a conspiratorial character. And this characterization of Italian criminality led to calls for an acceleration in the implementation of more extreme measures which went well beyond the simple monitoring of criminals arriving illegally from Italy. If in 1907 the New York Times was still asking the question “Black Hand a Myth or a Terrible Reality” (Is ‘the Black Hand’ 1907), in 1909 the threat was definitely real and on the rise, an “increasing menace” (White 1909) threatening to spill out from the confines of the Italian community and aim its attacks directly at American institutions (New York Is Full of Italian Brigands 1905). An article by the journalist F. Marshall White alarmingly predicted that, in 1910, the number of Italian criminals would reach 50,000, based on an estimate allegedly done by Petrosino himself,10 that the percentage of criminals in the Italian population in 1908 was about 2–3% (White 1909). The fact that the assassination happened in Italy was taken as evidence that the Black Hand was indeed a branch of a much larger and pervasive organization based out of Italy (Petrosino Slain in Italy on Sentence of New York Black Hand 1909). Articles that explained the origin of the Mafia and the Camorra and linked them to the Black Hand proliferated (The Camorra, the Mafia 1909). The structural, institutional presence of organized crime in the Italian system made the ramifications much more frightening. An article on 28 March by an anonymous veteran diplomat portrayed the Mafia as an institution above all institutions, and to which all Italian institutions both inside and outside Italy were subservient, characterizing the entire Sicilian populace as accomplices through omertà (Diplomat 1909):

the biggest national virtue in Sicily is “omertà” which means that one must never in any way help the authorities by giving information of crimes within one’s knowledge […]

I have endeavored to show above the extent to which Italian politics, Italian police, Italian magistracy, Government officials, both at home and abroad, and even Cabinet Ministers are dominated by and subservient to the Mafia.

The tone of the discourse surrounding the assassination rapidly intensified. In a pamphlet published immediately after the assassination Oppenheimer, noting that “so many unscientific and uninformed if not frenzied sociologists, strike not only at the Italian criminals, but at the Italians generally, and for no reason other than that they are Italians” felt the need to tell a different “Truth about The Black Hand” (Oppenheimer 1909).

In an official statement, the day after the assassination, lamenting the laxity of immigration laws, Deputy Commissioner Woods, referring to Southern Italians with racially inflected language, suggested that perhaps “men who by breeding and inheritance are accustomed to take the law into their own hands” should not be allowed into the country (Spies on Petrosino at Naples 1909). The idea that foreign criminality, particularly Italian criminality, was the biggest problem of American cities and that it was a result of a certain culture and of certain non-fungible, inherited “racial” traits came increasingly to the fore, along with the insistence that the only way to stop this scourge on the American nation was to limit immigration from those areas, an argument that would eventually lead to the Immigration Restriction Act in 1924. The press played a socially and politically active role in this process of Othering, and it was there that discourses about the criminal tendencies of Italians, their inability to assimilate, and the need for immigration restriction began to interact, finally converging in the 1924 legislation.

4. Representations in the Italian-American Press

This darker and more threatening view of the possible effects of immigration on the American nation, brought to the fore by the coverage of Petrosino’s assassination, was detected by Italian journalists and Italian-language newspapers which had, since their origins, always monitored and attempted to contest unfavorable representations in the mainstream American press. In the contemporary climate, with eugenics theories being increasingly applied to immigration, the racist rhetoric of the Dillingham Commission, and a general sense of the growing political weight of the problem of immigration and foreign criminality, Italians in America (along with the other so-called “Mediterranean races”) felt their racial status was precarious and unstable. Italians knew that the stakes were high and that their association with criminality, particularly the idea of their innate tendency to criminality, could be seen as indicating their impossibility of assimilating and possibly result in becoming the target of an outright exclusion like that which had been applied to the Chinese since 1882, or at best being considered second-class citizens on account of their uncertain racial status.

In an editorial written in the heat of the moment on 13 March, a journalist vents: “it is a terrible day for Italians in America, and none of us can maintain any longer that a criminal organization operating between Italy and America doesn’t exist.”11 The whole editorial, at the same time that it announces the terrible news, expresses preoccupation about “the disastrous impression that the crime will make on Americans” and the “wave of invective and hatred that will fall upon our name,” demonstrating a certain sense of disempowerment and impotence against the growing prejudice that they knew this terrible event would be used to support. There is the “impression that it will be exploited against us by those who can’t stand us and who do not tolerate us in these countries” (Il Luogotenente Petrosino Assassinato 1909).12 The article shows that the Italian community knew full well that the interpretation of the Black Hand as an international foreign conspiracy would contribute to making the status of all Italians in America more precarious and that manifestations of intolerance and prejudice would increase. As an example of these possible consequences, another editorial from La Gazzetta del Massachusetts on 27 March reported the case of a kidnapping in Ohio in which the press had been quick to erroneously assume that the criminals were Italian, connecting this jumping to conclusions directly to the climate of hostility against Italians that followed Petrosino’s assassination. The editorialist goes on to explain that Petrosino’s assassination has set back by 50 years (in block capitals, “RETROCESSO DI CINQUANTANNI”) the progress that Italians had made in being accepted by American society and which had been shown by the demonstrations of solidarity just a few months earlier on the occasion of the Messina earthquake, and evokes the lynchings of New Orleans (1891) and Tallulah (1899), suggesting the possibility, “God forbid”, that such a thing could happen in the heart of New York City (Commenti Settimanali 1909), a reference which reveals their preoccupation with their racial status.

Conscious of the socially and politically active role played by the mainstream press, Italian papers reviewed and reprinted editorials which had come out in mainstream English-language papers (La Stampa Americana 1909). L’Araldo Italiano, for example, flagged the previously mentioned article Black Hand Peril (1909) which had come out in the Evening Sun the previous day, defining it as “very yellow” (with reference to the sensational element) and alarmingly exposed the dangerous logic of its underlying ideology. The article, invoking the ideas that would later be deployed by The Dictionary of Races or Peoples, suggested that Italians, and especially Sicilians, were incompatible with the complex democratic American justice system which assumes that an individual is to be considered innocent until proven guilty (Per la Morte di Petrosino 1909). The editorial concludes, “From this article to one that advocates the exclusion of Sicilian immigrants as an extreme measure against extreme evils seems but a short step away.”13

Just as these Italian-language newspapers flagged articles unfavorable to the Italian community, they also often republished and commented on favorable ones. Both L’Araldo Italiano and Il Progresso Italo-americano wrote editorials based on an article by Arthur Brisbane, editor of the New York Journal (and very close to William Randolph Hearst) and whose column had an estimated daily readership of over 20 million (Il Mistero di Palermo 1909; Let Us Not Get Hysterical 1909). Brisbane’s article, entitled “Let Us Not Get Hysterical About Black Hand or Mafia,” labels exaggerations about the Black Hand as “hysterical” and utter “nonsense”, describing the Black Hand as a myth that “cannot compare with our mob murderers that burn and hang negroes”, and suggests that a more balanced approach involving dedicating more police and having Italian-speaking policemen would help deal more effectively with the problem and thus reduce such hysterical responses. The picture that emerges is one of “industrious” and “law-abiding” Italians, frugal people who by working, accumulating wealth, and paying taxes and rent, are contributing to the wealth of America and therefore deserve a level of police protection from the city commensurate with their numbers. In both Italian newspapers, the commentators, understanding the power of such a widely circulating newspaper in swaying public opinion, acknowledge the importance of such a defense of the Italian community, and the Progresso sees in it, in spite of everything, proof of their progress in the assimilation process and some advancement in their acceptance by wider American society:

The editorialist concludes by suggesting that all Italians save a copy of Brisbane’s article and use it “against their detractors” and “those who treat them as dagoes” (Il Mistero di Palermo 1909; Per la Morte di Petrosino 1909; Let Us Not Get Hysterical 1909).The words being written by the ‘New York Journal, ’ which is like the Bible for people who, unfortunately, don’t see Italian things with the most generous disposition, are of exceptional value. They demonstrate that public opinion, as the Italian element in America increases and makes progress, can slowly change and give Italians just consideration.14

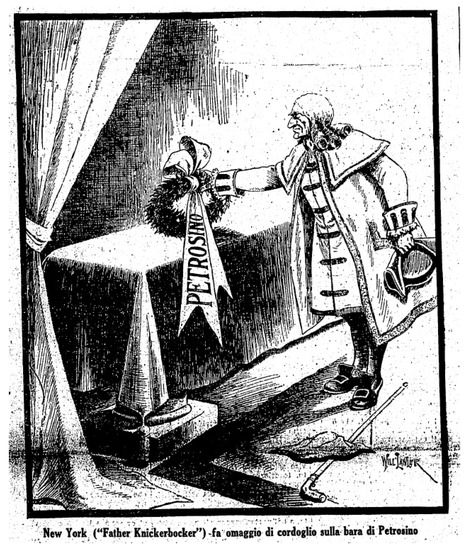

The press coverage shows that the Italian community was certainly flattered by the official honor dedicated to Petrosino, a son of Italy, by the institutions of the city, as illustrated by this image (Figure 2) in which the city of New York, symbolized by Father Knickerbocker, bows in honor before his coffin, but at the same time they wanted to reappropriate Petrosino as a symbol and articulate it to benefit their position in American society.

Figure 2.

Il Progresso Italo-americano, 13 April 1909, p. 1.

The funeral was certainly an opportunity to show publicly that they were all against criminality and on the side of the law embodied by the Italian Lieutenant. The accurate, detailed description of the massive participation at the funeral, both in its organization and funding (with a generous contribution to the widow’s fund), and of the procession, with an emphasis on the high number of participants, seems to be a response to the articles which, in the mainstream press, alarmingly estimated the percentage of criminals making up the Italian community. The Progresso published an impressive column listing, in order, all the benevolent societies that took part in the procession—the society of barbers, of stonemasons and contractors, of the workers of Nicosia (a little town in Sicily), etc.—which seems to suggest that they were all there, that they were all on the side of Petrosino, they were all on the side of the Law. As Il Telegrafo explains: “The expression of grief and pain will be so great […] that the American people will be convinced that the vast majority of Italians condemn the crimes of the shadowy organizations that plague our hardworking and honest community” (I Particolari dell’assassinio di Petrosino 1909).15

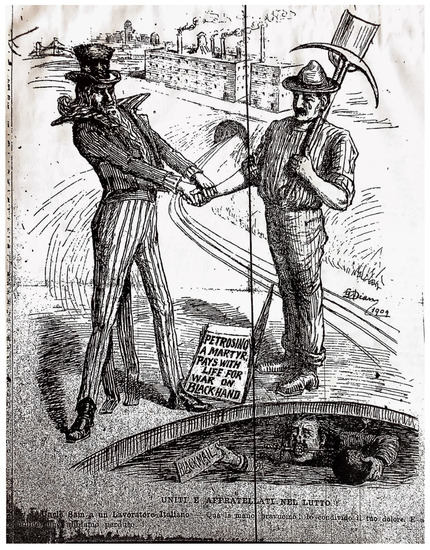

Another cartoon (Figure 3) published by La Follia di New York on 21 March reinforces this concept that Italians are on the side of the Law and that the Black Hand is a threat for the Italian community just as much as it is for the whole nation. In this image, with Petrosino’s death announced by a sign physically placed between them, Uncle Sam (representing America) and a pick and shovel worker (representing the Italian community) cry together over Petrosino’s death as a martyr, which is seen as a loss that unites them. The caption says: “United and Brothers in Mourning: Uncle Sam to an Italian Worker--Here is my hand, my good man! I share your grief. It is a friend that we have lost.” In this cartoon, although the Black Hand is represented consistently with the iconography seen in mainstream magazines such as Puck or The Judge, as a threat coming to the American shores from across the ocean in the form of a dark figure with a stiletto between his teeth and a bomb in his hand, the Italian community is represented by the figure of a worker against the backdrop of American industry and infrastructure, thus suggesting the contribution of Italians to building America and the role of the Italian detective in upholding and defending American values, as the symbolic link between the Italian community and mainstream America.

Figure 3.

La Follia di New York, 21 March 1909, p. 1.

The rhetoric surrounding the figure of Petrosino in the Italian-language press was overwhelmingly marked by the idea that he was “one of us, ” that he was not an exceptional man as portrayed by the mainstream press in which he seemed to tower above the mass of Italians who were portrayed as criminals at worst and cowardly “omertosi” at best, but rather a simple, ordinary, and honest man like most other Italians. The journalist Camillo Cianfarra, a personal friend of Petrosino who had accidentally run into him in Rome while he was on the mission which would ultimately lead to his death, was entrusted to write the story of Petrosino for L’Araldo. Cianfarra characterizes Petrosino as “the prototype of the Italian American who, having emigrated as a child, has never seen our homeland in the artistic and aristocratic grandeur of its big cities, ” and who was blown away and overwhelmed by it.16 He was a simple man who looked after his community, not so much “the scourge of criminals” but “a man with a big heart,”17 Through his account of some episodes of Petrosino’s career, Cianfarra depicts him as a man who was attentive to the circumstances of the individuals and the community that he served, rendering a justice tempered with humanity and empathy rather than merely the cold justice of the law (Cianfarra 1909a, 1909b). To cite Durante: “Petrosino was the epitome of national virtue transported to the American scene. He was the redemption of the vast majority of honest people from the misdeeds of a small minority responsible for the discredit that impacted an entire community” (Introduction, Ciambelli 2009, p. 21).18

Moreover, in Cianfarra’s editorials, instead of being held up as the greatest of detectives with a brilliant career, as he had been in the mainstream press, Petrosino was instead presented as having been, in fact, held back from having the success he could have had because of his independent-mindedness and refusal to be subservient to corrupt local politics. It is a remark that points in the direction of a whole different narration, one in which the corruption of local police and Tammany Hall was as much to blame for the criminality in New York as the actions of criminals themselves, notably by putting up obstacles to Petrosino’s career progression and to the success and funding of the Italian Squad. This suggests that responsibility for criminality in New York was a far more complex phenomenon than simply the culpability of individuals but was rather entangled with the interests and corruption of local police and politicians.

In a similar vein, the lawyer and activist Carlo Speranza suggested that the failure of Petrosino’s mission to Italy was also linked to institutional failures. He writes: “We must not send or allow brave officers to go to their death in inspiring but impractical skirmishes” (Speranza 1909). Substituting the rhetoric of the martyr and the hero, which was at play in the mainstream press, with that of the victim, Speranza reveals the reality of the inadequate resources and police incompetence that surrounded Petrosino’s mission and, in general, the policing of the Italian neighborhoods.

As Roediger notes, “Early in the 20th century it was by no means clear that immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe would escape the condemnations of white supremacists” (Roediger 2005, p. 93) and be accepted within American society as equals. This uncertainty, the precariousness of this position, becomes apparent in the press coverage of sensational and shocking events such as Petrosino’s assassination which, by showing a cross-section of the contemporary debate over the problem of Italian criminality, functions as a point of intersection between discourses of racialization and identity construction. A detailed study of these representations and counter-representations contributes to bringing to the fore the importance of these initial phases, marked by discrimination on the basis of race, for the history of the Italian Diaspora and moves us further towards a better understanding of the role that race played in the dynamics of negotiating an Italian-American identity.

Funding

Much of this research was funded by a Fulbright Research Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the courteous staff of the Historical Periodicals section of the New York Public Library.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Los Angeles Herald compared Petrosino’s funeral to that of the political economist and journalist, Henry George, in 1897: “The funeral was one of the largest ever witnessed in New York since the burial of Henry George several years ago”. In turn, George’s funeral had been compared to Abraham Lincoln’s. The New York Tribune described the extension of the procession, illustrating it with photographs: “The streets were thronged all along the line of march from Lafayette Street to Houston, to Mulberry, to Bleecker, To Mercer, to Waverley Place, to University Place, to 12th Street, up Fifth Avenue, to 57th Street, to Second Avenue, to 59th Street, where the civilians, foot police and firemen fell out leaving the mounted police and guard of honor to escort the body to its resting place in Calvary Cemetery” (Funeral of Petrosino 1909). |

| 2 | Prior to his assassination, Petrosino had already become a well-known popular figure, and his assassination was an opportunity to capitalize on the sensational event and gain readership. In popular fiction, the serialized novels by Bernardino Ciambelli featured Petrosino as a detective (Il delitto di Coney Island, ovvero la vendetta della zingara, serialized in La Follia di New York, 28 April 1907–26 July 1908 and I misteri di Harlem, ovvero la bella di Elizabeth Street, serialized in La Follia di New York, 16 January 1910–17 September 1911); but he also appeared in detective libraries (for example, Nick Carter’s 1909 story “The Black Hand; Or, Chick Carter’s Well-Laid Plot”, in The New Nick Carter Weekly) and in films such as The Black Hand: True Story of a Recent Occurrence in the Italian Quarter of New York (1906), an America silent film directed by Wallace McCutcheon which is generally considered the earliest surviving gangster film. After the assassination, another movie was released called The Adventures of Lieutenant Petrosino (1912). Ciambelli, after the assassination, also wrote a drama, Il martire del dovere, ovvero Giuseppe Petrosino, which remained unpublished for almost a century and was first published in 2009, edited by Francesco Durante (Ciambelli 2009). |

| 3 | W.E.B Du Bois, commenting on the lynching of two Sicilians in Tampa in 1910 and noting that they were, in fact, naturalized, ironizes that ”the inalienable right of every free American citizen to be lynched without tiresome investigations […] is one which the families of the lately deceased doubtless deeply appreciate” (quoted in Roediger 2003, p. 260). |

| 4 | For a more detailed discussion of the Congressional debates, see part 3 of Cacioppo (2005). Relevant documents include: U.S. Congress (1957); U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Immigration and Naturalization (1923); U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Immigration and Naturalization (1924), Harry H. Laughlin Archives, Papers, C-2, 6-6, Truman State University, Kirksville, MO; U.S. House of Representatives, Congressional Debate on Immigration Restriction, Testimony of James V. McClintic, 20 April 1921. |

| 5 | For a detailed discussion of issues of race in the context of Italian unification, see (Wong 2006). |

| 6 | A group of Sicilians were believed to be responsible for the murder of the New Orleans Chief of Police on 15 October 1890. However, they were acquitted at trial, provoking the anger of the local community. On March 14, 1891, an enraged crowd of 20, 000 people forcibly removed eleven Sicilians from the jail and lynched them (The Massacre at the Parish Prison 1891). |

| 7 | Benedetto Madonia’s corpse was found in a barrel abandoned in the street, and Lt. Petrosino solved the case by using both logic and local knowledge, tracing it to a band of counterfeiters and extortionists headed by Giuseppe Morello. Petrosino was able to identify the victim, but, in the end, despite numerous arrests of associates of Morello’s gang, no one confessed and the case was closed with no convictions (Dash 2009, p. 155). |

| 8 | Furthermore, Oppenheimer (1909) reported that: “Prominent Italians have often made the complaint that every immigrant of dark complexion, unless he wears a Turkish fez when arrested, is put down in the police blotter as being an Italian, and that by this slip-shod method of keeping police records, Italians are made responsible for a variety of crimes committed by other nationalities.” |

| 9 | The Immigration Restriction League, founded in 1893, became a proponent of “the biological engineering of the body politic”; in 1904, the Carnegie Institution opened a Station for the Study of Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island; in 1911, The Dillingham Commission published vol. 9 of its Report, A Dictionary of Races or Peoples, which outlines a “hierarchical scale of human development and worth” (Jacobson 1998, pp. 77–79). |

| 10 | Gaetano D’Amato, former president of the United Italian Societies of New York, in an article published in the North American Review in 1908 which explains how the Black Hand scare was a fabrication by the press, reports that journalists speciously used Petrosino’s name to back up false claims: “One monthly magazine even published an alarmist article, actually signed with the name of Petrosino […] entitled ‘Italian Mafia Has New York by the Throat,’ expressing views not held by the detective, who had never even heard of the article until it was shown to him in the press” (D’Amato 1908, p. 547). |

| 11 | “È questa una gran brutta giornata per gli italiani d’America e nessuno di noi potrà più dire che non esiste un’associazione del delitto che ha ramificazioni in Italia e in America”. All translations are the author’s. |

| 12 | La impressione disastrosa che il delitto produrrà fra gli americani”; “onda di vituperio e di odio ricade sul nostro nome”; “impressione che sarà sfruttata ai nostri danni da quelli che non ci possono vedere e che non ci tollerano in questi paesi”. |

| 13 | “Da questo articolo ad uno che invochi quale estrema misura contro estremi mali l’esclusione dell’immigrante siciliano ci pare breve il passo.” |

| 14 | “La parola in questo momento del ’New York Journal’, ch’è come la bibbia per quella gente che non guarda, disgraziatamente, le cose italiane con la miglior disposizione d’animo, ha un valore eccezionale. Essa dimostra che l’opinione pubblica, man mano che l’elemento italiano in America aumenta e progredisce, si cambia e sa tributargli la dovuta considerazione.” |

| 15 | “La dimostrazione di lutto e di dolore sarà così grande […] che il popolo americano si convincerà che la grandissima maggioranza degli italiani condanna i delitti delle tenebrose associazioni che funestano le nostre colonie laboriose e oneste.” |

| 16 | “Il prototipo del Italo americano che, emigrato bambino, non ha mai visto la patria nostra nell’ imponenza artistica ed aristocratica delle sue maggiori città.” |

| 17 | “Il terrore dei briganti”; “un uomo di cuore.” |

| 18 | “Petrosino rappresenta l’epitome della virtù nazionale trasportata sulla scena americana. È il riscatto della stragrande maggioranza degli onesti rispetto alle malefatte di un’esigua minoranza responsabile del discredito che tocca un’intera comunità.” |

References

- 1909. A Review of the World. Current Literature 46: 465.

- Black Hand Peril. 1909, The Evening Sun, March 18.

- Blackmail and Murder. 1909, Outlook, March 27, 656.

- Blames Immigration for the Black Hand: Lieut. Petrosino Says We Are the Dumping Ground for the Criminals of Italy. No Central Organization Italian Detective Declares the Crimes Are the Work of Small Bands at Odds with Each Other. 1908, New York Times, January 6, 14.

- Cacioppo, Marina. 2005. “If the Sidewalks of These Streets Could Talk”. Reinventing Italian-American Ethnicity: The Representation and Construction of Ethnic Identity in Italian-American Literature. Nova Americana in English. Turin: Otto. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, Marina. 2016. Early Representations of Organized Crime and Issues of Identity in the Italian American Press (1890 to 1910). The Italian American Review 6: 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Career of Petrosino: Full of Thrilling Adventure and Brilliant Achievement. 1909, New-York Tribune, March 14, 3.

- Ciambelli, Bernardino. 2009. Il Martire Del Dovere, Ovvero Giuseppe Petrosino: Dramma in Quattro Atti. Naples: T. Pironti. [Google Scholar]

- Cianfarra, Camillo. 1909a. Io E Petrosino a Roma. L’Araldo Italiano, March 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cianfarra, Camillo. 1909b. L’uomo e Il Poliziotto. L’Araldo Italiano, March 16, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Coladonato, Valerio. 2014. Italian-Americans’ Contested Whiteness in Early Cinematic Melodrama. Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commenti Settimanali. 1909. Era Una Donna Italiana. Gazzetta del Massachussetts, March 27. [Google Scholar]

- Cosco, Joseph P. 2003. Imagining Italians: The Clash of Romance and Race in American Perceptions, 1880–1910. Suny Series in Italian/American Culture; Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, Gaetano. 1908. The ‘Black Hand’ Myth. North American Review 187: 543–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, Mike. 2009. The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Diplomat, A. Veteran. 1909. Protection of the Slayers of Petrosino: Influences of Camorra and the Mafia Exerted on the Police of Italy May Shield Assassins and Booty. New York Times, March 28, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, Francesco. 2001. Italoamericana: Storia e Letteratura degli Italiani negli Stati Uniti, 1776–1880. Milan: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Durante, Francesco. 2005. Italoamericana: Storia e Letteratura degli Italiani negli Stati Uniti, 1880–1943. Milan: Mondadori. [Google Scholar]

- Funeral of Petrosino: City Honors Detective Thousands of Policemen and Fellow Citizens Escort Body Scenes at the Funeral of Detective Joseph Petrosino. 1909, New-York Tribune, April 13, 5.

- Gabaccia, Donna R. 2010. The History of Italian American Literary Studies. In Teaching Italian American Literature, Film, and Popular Culture. Edited by Edvige Giunta and Kathleen McCormick. New York: Modern Language Association of America, pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gambino, Richard. 1996. Blood of My Blood: The Dilemma of the Italian-Americans. Toronto: Guernica. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, Edvige, and Kathleen McCormick. 2010. Teaching Italian American Literature, Film, and Popular Culture. New York: Modern Language Association of America. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, Jennifer, and Salvatore Salerno. 2003. Are Italians White? How Race Is Made in America. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, Thomas A. 2003. White on Arrival: Italians, Race, Color, and Power in Chicago, 1890–1945. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- I Particolari dell’assassinio di Petrosino. 1909, Il Telegrafo, March 15, 1.

- Ignatiev, Noel. 1995. How the Irish Became White. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Il Luogotenente Petrosino Assassinato. 1909, Il Telegrafo, March 13, 1.

- Il Mistero di Palermo. 1909, L’Araldo Italiano, March 19, 1.

- Is ‘the Black Hand’ a Myth or a Terrible Reality?: Italian Ambassador and Consul General Deny Its Existence—Police Declare That Several Thousand Brigands Are at Work in the City Terrorizing the Italian Colony—Fifty Murders in Two Years Record of One Band. 1907, New York Times, March 3, 1.

- Jacobson, Matthew Frye. 1998. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kappeler, Victor E., and Gary W. Potter. 2006. Constructing Crime: Perspectives on Making News and Social Problems, 2nd ed. Long Grove: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- La Stampa Americana. 1909, L’Araldo Italiano, March 16, 1.

- LaGumina, Salvatore John. 1999. Wop!: A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States. Toronto: Guernica. [Google Scholar]

- Let Us Not Get Hysterical About Black Hand or Mafia. 1909, Il Progresso Italo-Americano, March 20, 1.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot. 1891. Lynch Law and Unrestricted Immigration. The North American Review 152: 602–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, Robert M. 2010. The Black Hand: Terror by Letter in Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marazzi, Martino, and Ann Goldstein. 2004. Voices of Italian America: A History of Early Italian American Literature with a Critical Anthology. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marazzi, Martino. 2000. Le Fondamenta Sommerse della Narrativa Italoamericana. Belfagor 327: 277–96. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, Marie-Christine. 2011. The Italians in America, from Transculturation to Identity Renegotiation. Diasporas 19: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimi Aguglia’s ‘Iorio’ Quite a Shock to Bowery. 1909, New York American, April 7, 1.

- Mission That Took Petrosino to Italy: Sent There under a Plan Devised against Criminals by an Italian Treasury Agent Here. Getting Their Records Measures under Way by Which Undesirable Immigrants Were to Be Sent Back. Mission That Took Petrosino to Italy. 1909, New York Times, March 16, 1.

- Moses, Paul. 2015. Black Hand. In An Unlikely Union. The Love-Hate Story of New York’s Irish and Italians. New York: NYU Press, pp. 113–54. [Google Scholar]

- Murder of Detective Petrosino. 1909, The Independent … Devoted to the Consideration of Politics, Social and Economic Tendencies, History, Literature, and the Arts, March 18, 555.

- New York Is Full of Italian Brigands. 1905, New York Times, October 15, 1.

- Oppenheimer, Francis J. 1909. The Truth About the Black Hand. New York: National Liberal Immigration League. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Robert Ezra. 1922. The Immigrant Press and Its Control. Americanization Studies. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Per la Morte di Petrosino. 1909, L’Araldo Italiano, March 20, 1.

- Petrosino a Terror to Criminal Bands. 1909, New York Times, March 14, 2.

- Petrosino Slain in Italy on Sentence of New York Black Hand: Proof That One Death Society Is in Two Lands. 1909, New York American, March 14, 1.

- Petrosino, Mortally Wounded, Died Firing in Vain at His Assassins. Marked by Black Hand, He Fell a Victim of Police War on Blackmail. 1909, New York Herald, March 14, 1.

- Petrosino. 1909, The Independent … Devoted to the Consideration of Politics, Social and Economic Tendencies, History, Literature, and the Arts, March 18, 598.

- Richards, David A. J. 1999. Italian American: The Racializing of an Ethnic Identity. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger, David R. 2003. Du Bois, Race, and Italian Americans. In Are Italians White? How Race Is Made in America. Edited by Jennifer Guglielmo and Salvatore Salerno. New York: Routledge, pp. 259–63. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger, David R. 2005. Working toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White: The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Edward A. 1901. The Causes of Race Superiority. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 18: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, Gino. 1909. Petrosino and the Black Hand. Survey 22: 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spies on Petrosino at Naples. 1909, New York Times, March 14, 2.

- The Camorra, the Mafia, and the Black Hand. 1909, New York Times, April 11, 1.

- The Massacre at the Parish Prison. 1891, Harper’s Weekly, March 28.

- To Guard Body of Policeman. 1909, Los Angeles Herald, April 19, 1.

- Undesirable Citizens. 1909, The Independent … Devoted to the Consideration of Politics, Social and Economic Tendencies, History, Literature, and the Arts, April 1, 712.

- United States Immigration Commission (1907–1910). 1911. Dictionary of Races or Peoples; Senate Document—United States Congress, 61st, 3d Session. Washington, DC: Government Print. Off.

- U.S. Congress. 1957. Annals of Congress, Vol. 1, Abridgements of the Debates of Congress, 1789–1956; New York: D. Appleton.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. 1924. Hearings on H.R. 5, 101 and H.R. 561; 68th Cong., 1st Sess. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 585–606.

- U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. 1923. Statement of Harry H. Laughlin. In Analysis of America’s Modern Melting Pot: Hearings Before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization; 67th Cong., 3rd Sess. (21 November 1922), Serial 7-C. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Vecoli, Rudolph. 1998. Italian Immigrant Press and the Construction of Social Reality, 1850–1920. In Print Culture in a Diverse America. Edited by James Danky Philip and Wayne A. Wiegand. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vellon, Peter G. 2014. A Great Conspiracy against Our Race: Italian Immigrant Newspapers and the Construction of Whiteness in the Early Twentieth Century. Culture, Labor, History Series; New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, Frank Marshall. 1909. The Increasing Menace of the ‘Black Hand’: The Murder of Petrosino Directs Attention to the Laxity in Immigration Laws While It Increases Terrorism of Organized Crime. New York Times, March 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Aliza S. 2006. Race and the Nation in Liberal Italy, 1861–1911: Meridionalism, Empire, and Diaspora. Italian and Italian American Studies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Arthur. 1909. The Problem of the Black Hand. McClure’s Magazine 33: 40–47. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).