Horses, Humans, and Domestic Bodily Knowledge in All’s Well That Ends Well

Abstract

:

1. The King of France’s Fistula and the Species Divide

Serving man or horse, this fistula cure makes clear that domestic practitioners proved capable of bringing relief to either species. The recipe itself, moreover, crosses seemingly uncrossable lines, since it does not require an expensive or highly trained physician like Helena’s father to prepare or administer the cure. Instead, both Bridget Parker and Miss Mills—otherwise unknown women with no formal connection to the medical profession—not only possess this seemingly specialized medical knowledge but share it with one another. Furthermore, such privately held and locally circulated recipes were at times touted as more effective than cures offered by supposed professionals. In her manuscript recipe book, Alice Corbett swears that her fistula cure involving neat’s foot oil “Cured those who have been given over by ye best Chirurgons In London” (Corbett n.d., p. 51), just as the King had been left for dead by his physicians.Take a quart of vinegar 2 penyworth of mer[-]cury an ounce of white coperres a litlebay salt and a litle alume sett it on yefire till the things is melted then put in aquarter of a pound of hony & when it is de[-]solved put it up in a bottle for useIt cureth all fistulas washing & siringingthem & all foule sors that need drying in manor horses

2. Bertram’s Equine Ambitions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Edwards reports that “By Continental standards horse ownership was widespread in England and the number of people who rode on horseback was one of the features noted by foreign observers” (see Edwards 1988, p. 6). |

| 2 | According to the American Horse Council, more than half a million of the United States’ 7.2 million horses were classified as “working” animals in 1997, and those animals presumably have adult handlers. https://horsecouncil.org/resources/economics/ (accessed on 18 September 2022). See also https://horsesonly.com/horse-industry/ (accessed on 18 September 2022). |

| 3 | |

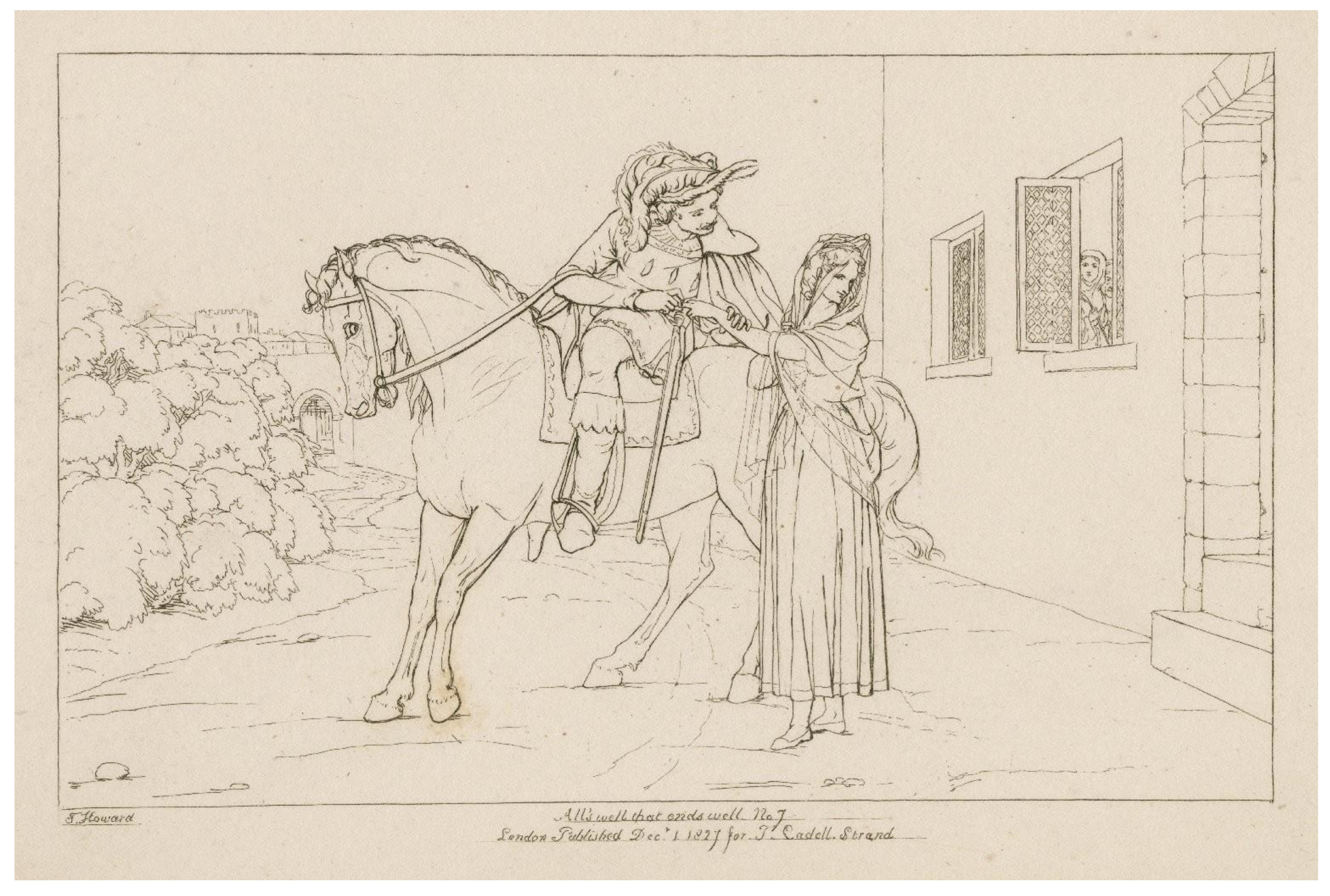

| 4 | Howard explains his purpose in the Preface to his five-volume collection The Spirit of the Plays of Shakespeare on page vi, https://archive.org/details/spiritplaysshak01howagoog/page/n14/mode/2up (accessed on 18 September 2022). The plates for All’s Well are in volume 3, at https://archive.org/details/spiritplaysshak03shakgoog/page/n4/mode/2up (accessed on 18 September 2022). |

| 5 | For an in-depth study of hobby-horses on the early modern stage (see Pikli 2021). |

| 6 | De Ornellas suggests that riding and training manuals “forge an all-male world”, utterly ignoring women as riders, even though women clearly were skilled in this area (see De Ornellas 2013). |

| 7 | All citations to All’s Well That Ends Well refer to the text as printed in Orgel, The Complete Pelican Shakespeare (Shakespeare 2002). |

| 8 | For discussion of this tradition of reading the King’s affliction as fistula ano (see Lopez 2019, pp. 21–24; Field 2007, p. 195). Lopez and Harris both remark that the story’s source in Boccaccio places the King’s tumor in the breast; Lopez argues that performance suggests Shakespeare intended audiences to imagine an anal fistula anyway (see Harris 2006, p. 169). |

| 9 | For a recent recap of these discussions see (Seneviratne 2020). |

| 10 | While many readers today might think of vaginal fistulas occurring during childbirth, no such use of the term fistula appeared in my search of EEBO-TCP database; dental fistulas are not mentioned in the database either. The OED does not list such meanings before the nineteenth century (Fistula 2022). |

| 11 | Over the past decade, a growing list of scholarship has worked to examine and contextualize early modern domestic recipe manuscripts. For foundational interpretations (see DiMeo et al. 2013; Leong 2018). Treatments that consider All’s Well in light of these manuscripts include Wall (2016, pp. 168–83), which examines the recipe in All’s Well as an act of preservation. Floyd-Wilson (2013), meanwhile, analyzes the overlap between these recipes as presented in the play and the occult in Occult Knowledge, Science, and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage. |

| 12 | To add another later of irony: horse leech is another term for veterinarian; if a horse specialist tried to cure a human’s hemorrhoids in this manner, it would suggest an even greater overlap between the human and the animal realms. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Howard, curiously enough, depicts Helena administering a potion to the King while members of his court look on, in an image described as “Helena giving the medicine to the king” (see Howard 1833, p. v). Some stagings of All’s Well have presented Helena’s treatment of the King in front of the audience, as in Scott Wentworth’s 2022 production at the Tom Patterson Theater in Stratford Ontario. |

| 15 | Curth asserts that, even though “women carried out the medical care for humans and small animals”, there is “little evidence to suggest that this would have been the case for larger animals” such as horses (see Curth 2011, p. 230). |

| 16 | For more on Helena as an unlicensed practitioner (see Traister 2003, p. 336). |

| 17 | For a reading that connects women’s loss of chastity to the public performance of medical care see (Lehnhof 2007). |

| 18 | Raber examines instances where products of horse—specifically dung and urine—are used to make medicine for humans and vice versa, but she does not address recipes that can be used on either species (Raber 2013, pp. 106–9). |

| 19 | Other performances have nodded toward the significance of horses in play’s military action—for example, Russell Jackson describes Bertram appearing in 3.3 “with an armored horse’s head in front of him, as if he were on horseback” in a 2003 RSC production (Jackson 2004, p. 194). |

| 20 | Edwards points out that Smithfield had a substantial horse market at the turn of the seventeenth century; he reprints a selection of Thomas Dekker’s 1608 Lanthorne and Candle-Light, Or the Bell-Man’s Second Nights Walke to illustrate the skills of buyers who can “redily reckon up all the Aches, Cramps, Crickes, and whatsoever disease else lyes in [a horse’s] bones” (Edwards 1988, pp. 98–99, 160–61). |

| 21 | While the bed-trick need not be visually represented onstage, productions sometimes allow viewers hints of the offstage action. A photo from a Washington University production (2004), for example, shows Helena straddling a blindfolded Bertram, thus hinting at her riderly control, if not horse training (see Buccola 2007, p. 76). |

References

- An Account of the Causes of Some Particular Rebellious Distempers. 1670. London.

- Banister, John. 1585. A Compendious Chyrurgerie. Imprinted by Iohn Windet, for Iohn Harrison the elder. London. [Google Scholar]

- Buccola, Regina. 2007. ‘As Sweet as Sharp’: Helena and the Fairy Bride Tradition. In All’s Well, That Ends Well: New Critical Essays. Edited by Gary Waller. New York: Routledge, pp. 71–97. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Alice. n.d. Recipe Book. Reference: Wellcome MS 212. Available online: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/hrvc6bbk (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Curth, Louise Hill. 2011. ‘A Plaine and Easie Waie to Remedie a Horse’: Equine Medicine in Early Modern England. In The Horse As Cultural Icon: The Real and Symbolic Horse in the Early Modern World. Edited by Peter Edwards, Karl A. E. Enenkel and Elspeth Graham. Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–40. [Google Scholar]

- de Gray, Thomas. 1639. The Compleat Horseman and Expert Ferrier. London: Thomas Harper for Lawrence Chapman. [Google Scholar]

- De Ornellas, Kevin. 2013. The Horse in Early Modern English Culture: Bridled, Curbed, and Tamed. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DiMeo, Michelle, and Sara Pennell, eds. 2013. Reading and Writing Recipe Books, 1550–1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Peter. 1988. The Horse Trade of Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Catherine. 2007. ‘Sweet Practicer, Thy Physic I Will try’: Helena and Her ‘Good Receipt’. In All’s Well, That Ends Well: New Critical Essays. Edited by Gary Waller. New York: Routledge, pp. 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fistula, n. OED Online. 2022. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Floyd-Wilson, Mary. 2013. Occult Knowledge, Science, and Gender on the Shakespearean Stage. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Jonathan Gil. 2006. All Swell That End Swell: Dropsy, Phantom Pregnancy, and the Sound of Deconception in All’s Well That Ends Well. Renaissance Drama 35: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horse, n. OED Online. 2022. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howard, Frank. 1833. The Spirit of the Plays of Shakespeare. London: T. Cadell. [Google Scholar]

- Isherwood, Christopher. 2006. Maybe He’s Just Not That Into You, Helena. New York Times, February 14, E1. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Russell. 2004. Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon: Summer and Winter 2003–2004. Shakespeare 55: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, Robert. 2006. All’s Well That Ends Well. Review of All’s Well That Ends Well, by Darko Tresnjak, Theatre for a New Audience. Shakespeare Bulletin 24: 113–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnhof, Kent R. 2007. Performing Woman: Female Theatricality in All’s Well, That Ends Well. In All’s Well, That Ends Well: New Critical Essays. Edited by Gary Waller. New York: Routledge, pp. 111–24. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Elaine. 2018. Recipes and Everyday Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and the Household in Early Modern England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Jeremy. 2019. Text as Performance as Text: The King’s Disease in All’s Well That Ends Well. In Shakespeare in the Light: Essays in Honor of Ralph Alan Cohen. Edited by Paul Menzer. Vancouver: Fairleigh Dickinson Press, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, Julia Reinhard. 2011. Thinking With Shakespeare. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacInnes, Ian F. 2011. Altering a Race of Jades: Horse Breeding and Geohumoralism in Shakespeare. In The Horse As Cultural Icon: The Real and Symbolic Horse in the Early Modern World. Edited by Peter Edwards, Karl A. E. Enenkel and Elspeth Graham. Leiden: Brill, pp. 175–89. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, Gervase. 1610. Markhams Maister-Peece. London: Nicholas Okes. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Bridget. 1663. Recipe Book. Reference: Wellcome 3768. Available online: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/d37s6qq4 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Pendleton, Thomas A. 2005. All’s Well That Ends Well at the Duke Theatre. Shakespeare Newsletter 55: 66, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Perssehouse, Richard. 1643. Bifolium miscellany of medical, domestic, and veterinary receipts [manuscript], Belhall, Folger X.d.738. [Google Scholar]

- Pikli, Natália. 2021. Shakespeare’s Hobby-Horse and Early Modern Popular Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Post, v.2. OED Online. 2022. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raber, Karen. 2013. Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne, Sachini K. 2020. Rethinking the ‘Good Receipt’All’s Well That Ends Well. Essays in Criticism 70: 160–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, William. 2002. All’s Well That Ends Well. The Complete Pelican Shakespeare, 2nd ed. Edited by Stephen Orgel. New York: Penguin, pp. 565–603. [Google Scholar]

- St. John, Johanna. n.d. Johanna St. John Her Book. Reference: Wellcome MS 4338. Available online: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wa8darch (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Traister, Barbara Howard. 2003. ‘Doctor She’: Healing and Sex in All’s Well That Ends Well. In A Companion to Shakespeare’s Works, Volume IV: The Poems, Problem Comedies, Late Plays. Edited by Richard Dutton and Jean E. Howard. Hoboken: John Wiley, pp. 333–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Wendy. 2016. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern Kitchen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nunn, H.M. Horses, Humans, and Domestic Bodily Knowledge in All’s Well That Ends Well. Humanities 2022, 11, 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050121

Nunn HM. Horses, Humans, and Domestic Bodily Knowledge in All’s Well That Ends Well. Humanities. 2022; 11(5):121. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050121

Chicago/Turabian StyleNunn, Hillary M. 2022. "Horses, Humans, and Domestic Bodily Knowledge in All’s Well That Ends Well" Humanities 11, no. 5: 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050121

APA StyleNunn, H. M. (2022). Horses, Humans, and Domestic Bodily Knowledge in All’s Well That Ends Well. Humanities, 11(5), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050121