Abstract

In northeastern Brazil, a region with extreme droughts and the smallest rainfall index in the whole country, water sources are crucial to ensure the survival of humans and nonhumans in this semi-arid region, known as sertão nordestino. Since the mid-twentieth century, classical cultural expressions focusing on this area have emphasized poverty in a desert of dry vegetation. Unlike romanticized portrayals of the backland in the 1990s, contemporary visual culture resorts to speculative and science fictional elements to reflect on possible futures amidst pressing socio-environmental challenges in the Capitalocene. This article examines how speculative and science-fictional elements in the film Bacurau (2019) by Juliano Dornelles and Kleber Mendonça Filho and the sertãopunk comic Cangaço Overdrive (2018) by Zé Wellington and Walter Geovani configure human–nonhuman and life–death entanglements to rearticulate both the representation of these communities as backward or picturesque and their historical de-futuring due to neo-colonialism and extractivism. These Brazilian visual productions problematize the notion of sustainability as a linear progression of human-centric futurity. In a dialogue between feminist posthumanist (Donna Haraway) and decolonial (T. J. Demos) works and the visual productions, I offer the notion of ‘vernacular sustainabilities’ that decenters the human while fashioning new conceptualizations of entangled and diverging futures in the sertão.

Unlike romanticized and contemplative representations of the sertão nordestino in the 1990s, some of twenty-first century’s visual culture products have turned to speculative and science fiction [SF]1 to reflect on the socio-ecologies of the region in the context of climate change and the extinction drive of the Capitalocene2. Given the special atmospheric and geographical characteristics of the northeastern region in Brazil, its transformations due to climate change, and its colonial history, so the way contemporary visual culture reflects on this region is very particular. While there is a considerable scholarship on Latin American speculative and SF currents, the recent emergence of futuristic genres such as sertãopunk in Brazil recasting a territory loaded with mythology and symbols as the sertão in the twenty-first century explains the scarce critical approaches to the topic3.

Since the twentieth century, the sertão nordestino has been the object of a long literary and cultural tradition4 that depicted the particularities of the local environment, emphasizing the cultural richness in the mix of sixteenth century Portuguese, indigenous, and African languages as well as the hardship and lack of hope in a largely impoverished and remote region forgotten by the rest of the nation (Lowe 2016, pp. 8–9). At the same time, landscapes such as the sertão have been used as emblematic places in nationalistic discourses (Saramago 2021, p. 16). The contemporary visual culture productions that I study here are inserted in that tradition but employ speculative and SF aesthetics to explore extinction prospects and the fight for the survival of local communities in the Capitalocene, in a region where water resources are scarce, droughts are intensifying, and the neocolonial past is still a pressing reality.

The purpose of this article is to analyze the speculative and SF features to envision possible futures in two contemporary visual productions: the film Bacurau and the comic Cangaço Overdrive. I contend that these works activate what I call ‛vernacular sustainabilities’, i.e., socio-ecological interconnections configured by multispecies and life–death entanglements that radically oppose the (historical) de-futuring of local human and nonhuman communities of the sertão in the northeast. If the “vernacular” points to grassroots dialects spoken in a particular region, and “sustainability”5 in environmental discourses indicates “the ability of a given ecosystem to maintain its essential functions […] over time” (Cielemęcka and Daigle 2019, p. 70) for the well-being of future generations, the idea of ‛vernacular sustainabilities’ that I attempt to conceptualize names the web of socio-ecological relationalities between humans and the environment grounded in the lived experiences and practices of local and marginalized communities (Afro-indigenous, rural) that build an ethics of care, thus constituting a crucial alternative to developmentalist and extractivist models in the current ecological crisis. In particular, in this article, I will examine how the use of speculative and science fictional elements in these two visual productions build entangled relations between humans and nonhumans, death, and life as ways of decolonizing dominant future imaginaries governed by productivity and progress in the Capitalocene. Before analyzing the cultural expressions in question, I will establish the historical and artistic contexts from which they emerge and the relevance of the topics they explore.

“I thought you were all dead”—Damiano, Bacurau

“I have more than one life”—Cotiara, Cangaço Overdrive

1. She Spoke about the Past, Mixing It with the Future—Radical Futurisms and Cyborg Ecofutures in Contemporary Brazilian Culture

Writing about the Brazilian northeast in 1938, Brazilian author Graciliano Ramos captures in Vidas Secas a projection of an impossible future for a peasant family of the sertão: “A resurrection. The colors of health would return to the sad face of Miss Vitória. The children would wallow in the soft soil of the goat pen. All those surroundings were going to clink the cowbells. And the caatinga would turn green. Baleia waved her tail, looking at the embers” (Ramos [1938] 2018, p. 19, my translation)6. In this regionalist work, Ramos entangles moribund human and nonhuman lives with the drought-ridden environment and the projection of lives whose futures had been severed long ago. This poetic and suggestive scene from the late thirties entangles lifeforms at a threshold between life and death in a past mixed with visions of an impossible future7, i.e., a future-making that relates to the past in an entangled conceptualization of human-nonhuman, life–death kinships mobilized by imaginations from communities that have historically been de-futured. This form of futurity entangling diverse lifetimes, disenfranchised bodies, and singular materialities contrasts sharply with the popularized view of ‘Brazil, país do futuro’8. With the key publication Brazil, Land of the Future by Austrian writer Stefan Zweig who moved to Brazil in 1941 to escape a decadent Europe, the exclamation evokes the exuberant geographic extension in Brazil and the abundance of natural resources as a promise for a prosperous future. However, one may wonder, future for whom? Furthermore, under what conditions in places such as the sertão nordestino, where atmospheric dryness is worsened by climate change and (neo)colonial dynamics of resource extraction in the region?

Focusing on the inequalities revealed in the setting up of the Alcantara space center in the northeastern state of Pernambuco in 1982, socio-cultural anthropologist Sean T. Mitchell (2018) connected neoliberal technological aspirations with the temporality of a utopian future extended over the northeastern region: “The developmentalist utopia from which the space program was born conceived of inequalities along a temporal line, in which the telos of development […] put the promise of a confluence of the developed and the underdeveloped somewhere in the future” (p. 29). Mitchell observed how neoliberal capitalism instituted an imaginary time that displaced 1500 poor Afro-Brazilians from the coast to the land and activated the resistance of Afro-descendant communities living in quilombos to be downtrodden by progress. This temporal imagination is deeply engraved in the colonial and extractivist history of this sub-region of Brazil and, by extension, Latin America. Brazilian anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro (1972) reflects on how, in the formation of new social groups after the colonization, marginal and minority cultures (African slaves, disenfranchised communities, indigenous peoples) underwent a temporal dislocation in the capitalist export-oriented matrix: “They are peoples available for posting, once they have been unhooked from their matrices they are open to the new, as people who only have a future with the future of man” (p. 78, my translation)9. In this violent colonial temporal frame, marginalized groups have fought to dislocate the integration of their divergent temporalities into a monolithic and homogeneous time that attempts to standardize pluriversal ontologies into the broader time of the nation and capitalism.

Graciano, Ribeiro, and Mitchell seem to call cultural criticisms’ attention to what art historian, ecocritic, and decolonial scholar T. J. Demos (2022) calls “radical futurisms” as the emergence of cultural expressions that explore the question “Who has the right to produce the future” through “speculative visions of times to come” (p. 58). Demos conceptualizes contemporary modelings of futurisms where ethnic, class, and nonhuman identities are entangled in imagining an equal yet-to-come. Radical futurisms revise the social history of the future from a multispecies chronopolitics (Demos 2022, p. 58) that asserts the rights of the disenfranchised against dominant and domesticating uses of time in extractive capitalism. In these resistant temporalities, time is not narrated or perceived through linearity. Furthermore, as Kyle Whyte (2021) argues, in several indigenous cosmologies, kinship addresses “multiple responsibilities […] to the environment and humans to diverse plants and animals” (p. 5), hence, producing cross-connections between species and generations through multilayered temporalities.

Latin America, particularly regions such as northeastern Brazil, has played a significant role in the imaginations of domesticated futures where nature, Afro-indigenous, and rural communities have been shaped into the future projections of European Modernity as natural resources to be extracted. A paramount example of the de-futuring of poor communities and the sertão are quilombos, settlements first established by escaped slaves from slave plantations in Brazil before 1888. Formed by African slave descendants, quilombos and their lifestyles have pointed to the history of colonization and the modernizing project in Latin America. As Elizabeth Farfán-Santos (2016) argues, while the post-dictatorship 1988 constitution called attention to the rights of Afro-Brazilian communities, the status of quilombolas remained problematic since they had to fight to prove their authenticity to access rights guaranteed by the constitution. That constitution imagined quilombos as being part of the nation, although the definition of what characterizes a quilombo was still a subject of debate and struggle. While this constitution was securing a future through “the promotion of well-being for all without prejudice” (p. 2), for quilombolas, it was also paradoxically enforcing a persistent structure of “exclusion and violence in the right of land-ownership for poor, black Brazilians” (p. 3). My essay takes the socio-ecologies of quilombos, that is, how people interact with the environment in these northeastern Brazilian communities amidst struggles for land ownership and persistent racism, as departure points to examine the near-futures elaborated in the movie Bacurau and the comic Cangaço Overdrive, both fictionalizing quilombo-like communities. In particular, I ask how these contemporary cultural expressions envision multispecies futures that include multifarious temporal scales in a fictive Bacurau and Ceará in northeastern Brazil; and how these diverging futures resist capitalist conceptions of time, while proposing alternative forms of sustainable futures grounded in the socio-ecologies of local communities. If sustainability in environmental discourses proposes in general a human-centered discourse that rarely considers forms of envisioning futures produced at the margins of Western cultural traditions grounded in dual thinking (Cielemęcka and Daigle 2019, p. 69), how can multispecies stories in vernacular sustainabilities of the sertão prompt us to imagine futures where nonhumans are active agents and where forms of life/death entanglements can disarticulate hegemonic lineal temporalities?

As fictions dealing with near-futures traversed by environmental conflicts, these audio-visual and textual-visual productions explore futures from the margins involving questions about environmental justice and the colonial legacies in Latin America. These futuristic cultural expressions propose complex understandings of relationality across species and human/nonhuman ontologies. Although marginal in literary and cultural canons, speculative fiction and SF are the terrain where nonhuman perspectives, planetary and cosmic scales, and science–art relations have broadened the cultural limits of the thinkable and the narratable, thus opening spaces for the expression of the nonhuman (Ghosh 2016). While Bacurau’s setting is a fictive town west of Pernambuco “some years from now” (Dornelles and Filho 2019) and Cangaço Overdrive takes place in an imagined Ceará in a near future, also located north of Pernambuco, there are several similarities between the film and the comic. Both stories portray marginalized rural collectives in northeastern Brazil under attack by foreigners coming from the south of Brazil and American tourists. Both revive the cangaçeiro bandits, who, together with the local community members, fight to defend their ancestral lifestyles, local ontologies, and habitats. Some approaches to the movie and the comic have pointed to the relations with the decolonial epistemes that highlight marginalized and impoverished communities fighting for the right to exist (Sauri 2021). Read in the light of the present COVID-19 pandemic, Bacurau has been regarded as a “social drama” signaling historical repetitions witnessed in the “disparities in COVID-19 illnesses, deaths” in the northeastern region (Fischer 2021, pp. 168–69) and the disregard by president Jair Bolsonaro of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian land and health rights, thus repeating and deepening the same racist structures of Brazilian politics.

The intimate relationship between humans and the material environment in the northeastern region has a historical background. In the history of Brazil, black slaves who rebelled against their owners took refuge in the woods or other remote wild places while bandits (jagunços) who rebelled against inequality as the cangaçeiros took refuge in the dry vegetation of the sertão. This recasting of regional places in contemporary cinema and visual culture echoes what Jens Andermann (2017) calls “critical neo-regionalism”, that is, a re-emergence of regional places in cinema foregrounding nonhumans, the agency of places, and indigenous ontologies that do not divide nature from culture. Donna Haraway (2016) has suggested that “to renew the biodiverse powers of terra is the sympoietic work and play of the Chthulucene” (p. 55)—a term that aims to open for tentacular cyborgian thinking to allow perceiving “ongoing multispecies stories and practices of becoming-with” (p. 55). How can divergent ecofutures that involve multispecies kinships connected with Afro-indigenous cosmologies craft stories of mutual care beyond the hegemonic futurity conceived by extractive capitalism?

While Haraway does not provide detailed analysis of SF or speculative fiction, her way of connecting SF and indigenous ontologies through the cyborg figure provides a platform to bridge what would be disparate realms such as indigenous cosmologies and futuristic technology. However, it is important to lift the critique of decolonial scholars to Haraway´s use of Third World women of color and indigenous people as examples of a universal cyborg grounded in U.S. feminist theory, where the term loses its resistance and situated dimension. Drawing on this critique of Haraway´s cyborg, Pitman (2018, p. 4) prefers the idea of “oppositional cyborg” to refer to the adaptations and appropriations of new technologies by indigenous people to advance their demands and affirm their identity. In this study, I draw on this relation between opposition and cyborg since the two works studied here articulate an appropriation of new technology by marginalized groups for their self-affirmation into the future.

Latin American comics and films have a long engagement with the nonhuman. King and Page’s (2017) study on graphic novels point out that, since its emergence in the nineteenth century, Latin American comic culture has served as a site of contact between lettered and popular culture, of the critique of urban modernity (p. 14), and of the formation of posthuman subjectivities that challenge the humanist project. Speculative fiction scholarship focusing on Latin America has pointed out the genre´s use of fantastic imagination to tackle societal problems, filling in the “void of the future” (Chimal 2018, p. 6) after the crisis of Western ideas of progress to craft stories beyond absolute destruction. The volume on speculative fiction edited by Colanzi and Castillo (2018) highlights that speculative narratives in Latin America have tackled transformations of the body (with biotech), the meaning of being human in a planet in crisis, and the need of reaching to deep pasts to envision possible futures. My work draws on this scholarship on speculative fiction and broadens it by including a decolonial approach to the socio-ecological dimensions of the futures imagined by speculative narratives in Latin America. Regarding Latin American cinema, in their study on cinema and the more-than-human planet, Fornoff and Heffes (2021) pointed out that twenty-fist century Latin-American cinema shows a growing interest in environmentalist topics and an engagement with the nonhuman (p. 10), but the authors also call attention to considering up to what point can cinematic visualization render the nonhuman. This recent cinema scholarship considers several genres related with ecocinema (such as cinema of natural catastrophe); however, it does not include cinema that exhibits SF and speculative features coupled with environmental preoccupations and futures, as I do in this study.

Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive afford a speculative and science fictional lens toward sustainability and the future in environmental discourses. The question about sustainability, multispecies futurity in culture and politics take us to Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive as contemporary future fictions that employ speculative and SF elements to imagine a possible yet-to-come for vulnerable communities. Posited upon the invasion of foreigners to small rural villages in northeastern Brazil in a near future, Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive feature local communities fighting racist and colonial interests that try to eradicate their bodies and habitat from the map. Combining the drought history of the sertão with features from speculative fiction and SF (in dialogue with Western, thriller, and punk), these two visual culture expressions redress dystopian genres, taking elements from the past and present to assert a possible future for local communities and their habitat for whom corporate power decided to erase them from the future. As from the mid-twentieth century, the sertão was attached to an image of the interior of northeastern states characterized by severe droughts, mixed-race rural communities, and misery coexisting with bandit leagues and social leaders (Saramago 2021, p. 37). While Euclide da Cunha’s Os sertões from 1902 long influenced the portrayal of sertanejos as backward or as a symbol for national authenticity (Goodman 2016)10, the textual and visual poetics of the sertão has been reconstructed from contemporary contexts of climate change and new philosophical visions that produce tensions in the representation of nature–culture relations of this region. The cultural productions that I analyze here envision the sertão, its bandit culture, Afro-cultural roots, and rural lives from northeastern Brazil in a possible future against the extinction plan that extractive capitalism designed for them. Both visual culture expressions deal with communities on the verge of disappearing from the map in the northeastern region. In light of the contemporary political scene, the vanishing of these communities from text and image connects to President Jair Bolsonaro’s policies to delete environmentally protected areas and the fines for trespassing onto protected communities. Instead, Bolsonaro promised to intensify the exploitation of all available natural resources in Brazil, thus worsening for members of quilombos to buy land rights, while the landscape in northern Brazil is becoming dryer and water shortage is rife. This Brazilian political context resounds with both visual cultural productions. In these future fictions, the communities in Bacurau and Ceará constitute self-sustained communities that, with scarce water and food resources, manage to share and uphold an ethics of care against the attacks from outsiders supported by the police and the local governments.

I have sketched out the conceptual, cultural, and political frame in which futurity and chronopolitics in Brazil—and I would say in Latin America—become crucial issues in the present intensification of extractivism and rapid climate change in a region deeply affected by social inequalities. In what follows, I will devote the first section of my analysis to the movie Bacurau and turn to Cangaço Overdrive in the second section.

2. Human–Nonhuman, Life-Death Temporalities as Kinship in Bacurau

“Vocé, quer viver ou morrer?”—Damiano, Bacurau

With inspiration in the storyline of Asterix comic book11, Bacurau (Dornelles and Filho 2019) portrays a local community of Afro-Brazilians (and maybe also indigenous people) that fights capitalist and (neo)colonialist powers coming from outside the community with the help from a seed that gives them supernatural perceptive capacities. The movie’s dispersive aesthetics combines SF with futurist western12, a genre cinema of graphic and oppressive violence, but not spectacular, thus connecting this movie to Roucha’s Cinema Novo and Brazilian Western, in the revisionist Western from the 70s. With that unusual combination of aesthetic and cultural currents, the movie investigates the conflict between a local Afro-Brazilian community inspired in a quilombo in Northeastern Brazil and white foreigners coming from the South of Brazil, nearby cities, and tourists from North America, who take advantage of them and try to wipe them out from the map. Hence, Bacurau projects conflicting forms of future-making: the lineal (white) human-centered futurity coming from capitalist-imperialist forces aimed at extinction, and the diverging, multispecies forms of future-making from marginalized Afro-Brazilian communities in the sertão nordestino.

The film revolves around the conflict on access to water and river use where powerful private owners have occupied and militarized the only river nearby, thus preventing Bacurauans from accessing this vital source of natural water and forcing the water truck that provides the community with drinkable water to take the longest road. As spectators, we enter Bacurau together with the truck bringing drinkable water, to be launched into the funeral of the community’s matriarch, Carmelita, where strange things start to happen ominously announcing the disappearance of the community, as its erasure from the maps and satellite apps, and transformation into a hunting zone for American tourists. In this conflict, the police search for a run-away bandit, el Lunga—echoing the most famous outlaw cagançerio, Virgulio Lampião, in the 30s. El Lunga resists and fights the cutting of water channels that prevent the community access to river water, thus bringing to cultural memory the cangaçeiros, the bandits who gathered the dispossessed from the extractivist bonanzas (rubber, coffee, and minerals) in the 30s and 40s to oppose corporate and police power and who took refuge in the sertão.

Like Cangaço Overdrive, as I will develop later, Bacurau exhibits several intertwined temporal and narrative levels that add diverse temporal frames. One narrator is the bard, the old man singing and playing improvised songs in the guitar. There is also the storyline unfolding with the Bacurauans, and the surveillance and repressive narratives channeled by media, and the technology used by the police, the armed foreigners and white politicians from outside. Against this attack, the movie emphasizes collective action in Bacurau rather than individuals since this local community shares food provisions, showers together, and acts as a single entity in diverse events such as the death of the matriarch and the bloody confrontation with the Americans where all Bacurauans participate in the defense.

The film directors have commented that the town of Bacurau staged a quilombo community because when they looked for a diverse setting in that region, they realized that the sertão was too white13. This human collectivity also includes nonhumans and engages a cosmology from Candomblé traditions (uses of foresight tools, relation with dead ancestors, trance ritual) activated to fight the attacks from outsiders. Moreover, the movie entangles the inhabitants of Bacurau with the regional flora and fauna, thus portraying nonhuman centered forms of connection with the environment that acknowledge nonhuman agency. When the character Teresa, the granddaughter of the dead matriarch, arrives in the town, Damiano puts the seed of a tree in her mouth. Afterward, she begins perceiving things that we would call supernatural such as water flowing out of the coffin as foreboding sing. I will return to the coffins later when considering the death–life entanglements in the movie, but I want to highlight that the centrality of the seed in this movie foregrounds an ethno-pharmacology for the future in this movie. When the hunt from the Americans begins on the Bacurau community, Damiano distributes seeds to all of Bacurauans as medicine and a resistance medium that opened new sensible and perceptive realms of their surroundings. The seeds, as a psychotropic medium, produce multispecies kinships between Bacurauans, vegetal life, and supernatural realms. The use of local flora and customs to resist the invasion and slaughter also connects with the old museum of Bacurau staged in the movie from where Bacurauans recover traditional weapons and practices that they use to defend themselves from the outsiders.

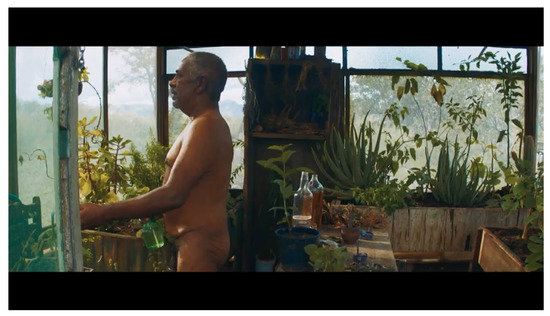

In the scene below (Figure 1), where two Americans approach Damiano’s little thatched house between the cacti to haunt the inhabitants, naked Damiano is watering the plants and speaking to them: “I thought you were all dead.” After a moment in which he stands looking out while we hear a bird squeal, he tells the plants, “don’t worry”, as if he, the plants, and the bird had connectedly sensed a danger lurking around. The camera shows the rain falling on the dry vegetation from where the two armed Americans emerge before that scene. As they approach, the still camera keeps on filming at the level of their hands holding the weapons and after they have passed away, we see again the bushy cactus landscape. The camera moves to a close-up of this foliage while we hear the bird squeal. In this subtle way, Damiano, the bird, and the vegetation connect through a transspecies communication produced by cinematic technique that alerts him about the approaching danger. Moreover, Mendonça Filho and Dornelles’ Bacurau takes its name from a night bird typical of the sertão that tupinis called wakura’wa, thus making cinematic kin between the human and this regional bird species.

Figure 1.

Film still, Bacurau.

In her study on nonhuman animals in Third Wave cinema, Fradinger (2021) analyses how cinematic strategies frame “humanimal assemblages” and proposes that Brazilian drought films such as Barren Lives by Nelson Pereira dos Santos and Black God, White Devil by Glauber Rocha “make human and nonhuman animals interchangeable under the common fate of the drought” (p. 124) where slaughtered animal corpses are exposed. In Mendonça Filho and Dornelles’ film, a similar frame of interchangeability can be seen in the examples commented in the previous paragraph. In Bacurau, the nonhumans emerge subtly as part of the human community in an interchangeable manner. When the foreigners from the South of Brazil arrive at the town on motorcycles, they comment to each other, “atrajimos as pessoas. Bom dia” [we attracted the attention of the people. Good morning]. Immediately after, the camera zooms in on a dog scratching itself and then moves to the human inhabitants looking at the foreign couple with estrangement. This subtle camera sequence portrays the dog as one of the “pessoas” [people] attracted by the foreigners’ arrival and, therefore, as a community member. Such a scene destabilizes the division of human–animal for the viewer (though not for the foreigners). Bacurau shows animal bodies sharing feelings with humans such as premonition, or as fossils, as in the shot on the fossil jaw of a piranha in the sand, pointing to the droughts in past barren desserts, but also as foreboding barren lives yet-to-come. In this way, Bacurau constitutes a human–nonhuman community on the verge between death and life, ancient spirits and dead ancestors that are holding on to a future from where they are being thrown out. At the end of the movie, the white mayor coming from the urban areas recognizes that he negotiated with the American tourists to let them in to hunt the Bacurauans. Consequently, he is put on a donkey with a mask of evil as part of an ancient ritual of punishment, in which the community pitied the donkey and wished it would come back from the dry arid landscape.

Analyzing the SF and speculative elements, I now turn a closer look to the interventions of technology in the movie. In his description of the uses of SF in contemporary Brazilian sertãopunk, de Sá and Silva (2020) mention that the inclusion of technology and social media partly break the idea that these local communities are organic and natural to portray technologies that are already part of life in this region (p. 8). Through technology, in Bacurau, we see how the rest of (white, Southern) society both sees and invisibilizes this community of Afro-descendants. On one hand, the TV installed in the old water truck (“Agua potável”) that is coming to Bacurau shows an announcement from the authorities to hand over the bandit el Lunga for compensation. This portrayal is paralleled in the reality show called “Pacote, el rey del gatillo” [Pacote, king of the trigger], where Bacurauan Pacote is shown ruthlessly shooting down people on TV that labels the scene “Sertânia” at the bottom of the screen. These uses of technology communicate how this community is shown to the rest of society as bandits, murderers, and marginal. However, that representation of el Lunga and the sertânia are opposed by the community’s own perception of el Lunga. For example, an old lady calls attention to the aesthetics of his clothes despite his outlaw circumstance as a call for self-affirmation and dignity. Additionally, a man at the funeral tells Lunga that he used to write very well and should not have stopped, and the community shows joy when he joins in their defense. These appraisals contrast sharply with his bandit figure shown on TV and open to other perceptions of this region both aesthetically, culturally, and politically. At the same time, technology is also used to show distorted images of Bacurauans and even erase them such as when Erivaldo tries to show the school class Bacurau on Google Earth and does not find it. This cutting out of technology that registers the existence of Bacurau creates a sense of strangeness and adds to that feeling of vanishing with the death dimension. Technology in this movie becomes a foreign invasion that constantly tracks the communityand their whereabouts, threatening them with erasure. In this movie, the drone flying over Bacurau, a feature of SF, simulates a UFO, but this technology here gathers important information from this village, maps their behavior, and can cut out all of their electronic devices.

For the marginalized community in Bacurau, death becomes an ominous material presence that acts as a form of looming prophecy. The materiality of death in the movie is mediated through the mysterious coffins that are delivered to the community, the ruins of a school on which the character Teresa poses her eyes on the way to Bacurau as well as the focus on other ruins throughout the movie (a fossil fish, abandoned buses). Furthermore, there are many subtle references to death in the movie such as the girl visiting the doctor for a hangover, who says “ganas de morré” [desire to die], or when el Lunga and his followers come out from their hiding place looking all pale and moribund, expressing that they are hungry (“Estoy com fome”). The overwhelming references and ominous evocations of death in the movie can be understood in the light of the extinction politics of the Capitalocene. Quoting philosopher Rodrigo Guimarães, Sauri (2021) contends that becoming extinct is part of the politics of developmentalism and extractivism while more people are left on the margins:

“What the film does is take a characteristic of the present and extend it into the future” projecting “an increasingly possible scenario” in which “there are more and more pockets of people left on the margins, without access to the benefits of development” and ”extractivism and exterminism finally became entirely reversible”.(n/n)

Bacurau projects this extension into the future of the corporate view. Ominous scenes in the movie point to death for the community, starting with the entrance of the water truck to Bacurau where we see a sign with the name of Bacurau followed by the mysterious phrase: “Se for vá na paz” [if you leave, leave in peace], which paradoxically evokes departure and death as a welcome into the town.

In the night scene below (Figure 2), the camera captures a group of horses running away, passing Bacurau from Manuelito’s nearby farm.

Figure 2.

Film still, Bacurau.

Simultaneously, the camera shifts to the inside of the houses to show the inhabitants sleeping with open windows from where we still hear and see the herd of horses. The moving camera over the sleeping bodies stops to zoom into the doctor played by Sônia Braga, who is having a distressful dream about a youngster from the town covered in blood falling over dead onto a hospital bed. This sequence of scenes (horses running away outside and the disturbed dream inside) foreshadows a human-animal connection and a looming future hanging over this human and nonhuman community, thus the scene has a premonitory power. The shift between outer to inner, planetary to local, is a recurrent feature in the film and adds to the enigmatic atmosphere, while it connects different dimensions. Indeed, the movie opens with a pleasant planetary view on planet Earth: the camera is placed in outer space shooting the Earth, and slowly begins zooming into the globe to the rural street where the water truck is driving in the dry landscape. The sequence from the zooming out to the zooming into the road portrays two contending views, a planetary and a local, and marks different observation points from where the events are seen.

Placed within the confrontation between colonizer and colonized fictionalized in the movie, this aesthetics of death (extreme hunger and ruin) connects with Glauber Rocha in the 60s, and in fact, the film directors have commented that Rocha´s cinema was an inspiration for this movie (Cannes interview, 2019). However, Bacurau is, despite its political message, a commercial film. Investigating the relations between the cinema that features the sertão and the favela in the 60s and in the 1990s, Ivana Bentes (2007) identified a shift from an aesthetics of hunger based in Roucha´s manifest, to what she called a “cosmetics of hunger” in the 1990s cinema. Bentes argues that while the aesthetics of hunger cinema in the 60s showed a concern with how to represent marginality, poverty, and vulnerability in reassuring manners (p. 243) against cliché images and for an ethics for images of pain; the cosmetics of hunger cinema of the 1990s was produced for an international globalized audience, where the sertão was romanticized, “sertão romántico” (p. 246), becoming a multicultural and pop place, stylized and self-mythicized. This cosmetic makes poverty a consumable object where spectators are encouraged to contemplate a spectacle of the poor killing each other or of an idealized sertão.

I contend that Bacurau differs from the cosmetics of hunger cinema in three ways. First, it presents the problem of poverty and underdevelopment as “a problem of how its victims are viewed” (Sauri 2021) and shown in the media by and to the rest of Brazilian society, rather than as an intrinsic problem of this community and this country. The movie´s investment in how outsiders see or try to invisibilize the plight of this local community in this movie reflects rather on what I call “the mediatization of hunger” including a self-reflection on the cinematic medium´s approach. Second, in Bacurau, the gaze of the foreigners is part of the fiction, thus beseeching the audience to think on which side one is, and therefore avoiding the paternalist reaction, the victimization of the vulnerable, and the contemplative gaze that characterizes the cosmetics of hunger. The tourist that used to contemplate the scene from outside is now inside the movie in a safari. Third, the hardships of characters such as el Lunga, who displays a resemblance with el Limpião, are shown through the sacrifices they make for the community (remain hidden, go hungry, not be able to write anymore), and not through victimizing images. In fact, several scenes in the movie seek forms of self-affirmation such as when at Carmelita´s funeral, Erivaldo (played by Rubens Santos) tells the community that Carmelita has relatives from all walks of life and professions (doctors to prostitutes) that came to say good bye. Indeed, Carmelita´s granddaughter, Teresa, played by Bárbara Colen, returns to Bacurau bringing vaccines. In contrast to the characters that return to the sertão in the cosmetics of hunger movies as a “projection of a lost dignity” (Bentes, p. 246) after a failed attempt in the city, Teresa in Bacurau returns for the funeral and we do not know anything about where she was before coming to Bacurau, thus avoiding the trope of the unsuccessful but affective comeback to recover a lost dignity from the urbanized areas.

In Archaeologies of the Future, Jameson (2007, p. xii) speaks about the relation between SF and the issue of identity–difference in connection with the anthropocentric (patriarchal) prejudices that are foregrounded when facing ‛the other’. In Bacurau, this relation identity–difference portrayed through SF and speculative elements is constantly traversed by racism. In the scene when the Americans meet with the two southern Brazilians that were hired to cut down the town’s communication with the outside, but end up killing a whole family and other Bacurauans, the colonizer’s racist view on the other is exposed. When the southerners try to explain the murders by making a parallel with the killings to be performed by the American hunters/tourists, the latter use a racist register to point out their lower status: “You look like us but are not”, pointing to the woman’s “broad nose”, and the guy’s “handsome Latino look”. This conversation evidences the diverse forms of structural racism and colonialism that still pervade the country and that affect how the impoverished areas of the northeast are perceived and treated. The bodies in the movie become sites where racist and colonial violence is reflected (e.g., the scene when the white Brazilian mayor kidnaps an unwilling Afro-Brazilian girl from Bacurau as a prostitute; the sharing of due food to the community by governmental authorities to fight scarcity; the American tourists´ view on Bacurauans as empty bodies), but also where the seed of resistance and self-affirmation can grow. Bacurau finishes with the list of workers involved in the making of the film, thus acknowledging the collective effort behind this cultural product. This strategy further contributes to an ethics of visualization of overshadowed bodies, emulating the collective of Bacurau in the fiction.

The strangeness and alien/foreigner interventions in Bacurau produce openings for the visualization of this more-than-human community that entangles life and death in its ontologies. In the scene when the southern female foreigner asks “what are those that live in Bacurau?”, to which a child replies “people” and the local woman explains it is the name of the local bird bacurau that hunts at night, we can sense the racism in the way that the southerners cannot consider a town such as Bacurau in their spatiotemporal ontologies. However, for the spectator, the scene opens a speculative space to reflect on what this community is. Are these ghosts to come of the Capitalocene, already dead people and environment, or survivors? What are the ontological and political status of a community that has long been de-futured but continues fighting for a future?

3. Cyborg Cangaçeiro—Technonature Temporalities in Cangaço Overdrive

“Nunca um defunto tinha voltadoe reivindicado uma propriedade”—Cangaço Overdrive

Supported by the Secretaria da Cultura do Governo do Estado do Ceará, this comic highlights traits of the regional cultures and customs intertwined with cyberpunk in a high-tech future that recasts the sertão in the light of north/south national inequalities and the current ecological devastation. While in Bacurau water is scarce, it still rains, and there are rivers with water around. The future portrayed in Cangaço Overdrive builds a more devastating drought scenario. With a start in medias res that breaks the narrative line, it is only in the middle of the story that one inhabitant of this 30-people community in Ceará describes the past that led to the current situation in that scorching future by pointing to a lack of rain in ten years, a climate exodus, and complete desolation until a freshwater source emerged on a hill. A group of dispossessed people that found the fountain decided to share it with others in need, thus forming a self-sustaining open community that caught the attention of corporations from the south interested in commercializing the water, but not in the lives or fate of local communities depending on it for survival. As we have seen, in Bacurau, high technology presents a looming perspective for the local community; moreover, to defend themselves, Bacurauans resort to the ancient weapons exhibited in the museum as well as precarious but effective (in the movie) forms of defense through underground ambush. However, in Cangaço Overdrive, technology and hyper-connection have advanced to such an extent that it allows both transhumanist experiments to extend lives and avoid death (only for corporations and governments that have the means to access this technology) and advanced surveillance mechanisms for population control, but are also appropriated for resistance. This dystopic use of technology by corporations and governments is typical of the cyberpunk genre. However, this futuristic comic fits in the sub-genre of sertãopunk, i.e., a northeastern speculative fiction genre14 that critically and creatively combines sub-genres such as steampunk or cyberpunk (dystopic future in high-tech societies) with the aesthetics and cultures from northeastern Brazil.

The creative effort in this comic is grounded in a team of graphic designers and artists, all of whom come from northeastern Brazil, thus exhibiting a regionalism even in the creation process (Adeodato Junior 2020). Despite the efforts to imbue the comic with regional features, one may wonder what the signs are that this is not just another cyberpunk story having the background of a regionalist setting of northeastern Brazil, rather than a northeastern futurism for the self-affirmation of local communities? In his study on the possible transformations of cyberpunk as a SF genre when transferred to other media as comic and cultural contexts such as in Cangaço Overdrive, Reis (2018) highlights several features in the comic that coincide with a cyberpunk aesthetics and its most prominent works such as Neuromancer or Monalisa Overdrive:

um Ceará imerso em tecnologia avançada capaz de abrigar ciborgues, conexões neurais, hackers, inteligência artificial e até ressurreições mas com conflitos sociais […] O regionalism da obra é retratada através da comunidade do Preá através de um noir futurista, our neo-noir, que contêm […] alienação, pesimismo, ambivalência moral e a desorientação das obras clásicas.(p. 3)

The cyberpunk features that Reis identifies in Wellington and Giovani’s comic seem to suggest that this work appropriates regional content to configure a cyberpunk in Western paradigms. However, even if cyberpunk is a genre rooted in Western culture, I contend that the comic shows a self-awareness about the dangers of mixing cyberpunk and cordel literature through the materiality of the comic. The succession of panels that afford movement to the story are not formatted in a traditional manner. The comic´s panels are uneven in size and some are higher and some lower, which scatters the order of the narrative, thus creating ambiguity as to the narrative sequence of the actions. Such structural arrangement in the page creates a temporal fluidity that mixes diverse temporalities that in turn matches the constant flashbacks in the narrative, also signaled by the change in tonality of the images from colorful to yellow-brownish. There are gutters separating the diverse panels in a page, which can contain scenes with bandits from the 1940s with futuristic scenes showing cyberhackers and cyborgs. The gutters afford a separation that I read as an effort to acknowledge difference in temporalities, ontologies, and epistemologies within the comic. This structure of the panels is furthered complicated by the addition of intra-panels with speech bubbles featuring social media entrances that are not part of the dialogues in the frames or are even located between frames commenting on the action taking place, which draw attention to how the rest of society sees the conflict and the fight of this community. In this sense, the comic invites a reflection on how this community and the socio-environmental conflicts in the area are mediatized and seen, rather that communicating alienation and pessimism as in traditional forms of cyberpunk.

Furthermore, the comic engages a vaporwave poetics that shows a preoccupation with promised socio-ecological futures that never materialized for poor Brazilians in the northeast. As Adeodato Junior (2020) notices, this comic evokes vaporwave in retro bright colors and simple shades of the book cover, evoking high-tech futures. While vaporwave refers to a consciousness about liberties and rights that would come with the Internet era but never materialized, in the comic, this aesthetics extrapolates to the promises made to the local Afro-Brazilian communities that did not happen such as the right of access to land rights. In this sense, the technology that allows the cyborg character Cotiara to return from death and transcend life opens a parallelism between the bandits from the past and the local hackers from the present and future that still fight to materialize the futures that they were promised. While Cotiara´s body is an ambiguous hybrid kept alive by mangrove water and technology and his condition is one of alienation in that future, this hero-centered focus is strategically blurred to put the urgent concerns of that community in the center of the scene so much that his whole body is put at the service of the resistance: his enhanced body performance serves to fight the police and Avelino, and from the memories stored in his brain, the community obtains the land property titles. In that sense, recalling Pitman (2018, p. 4), this is an “oppositional” cyborg cangaçeiro and not an object recovered from the past for nostalgia or contemplation.

As sertãopunk, the comic Cangaço Overdrive is part of a broader cultural movement about futuristic fiction in the Northern cultures in Brazil15 that de Sá and Silva (2020) call “Movimento Sertãopunk”, where the geography and cultural history of the sertão are refashioned by the futuristic aesthetics of the cyberpunk to reflect on socio-environmental conflicts in the region, which in turns also infiltrates the cyberpunk genre with an activation of the socio-ecological and political concerns of the local community. However, futurity in Cangaço Overdrive is constructed by engaging the cultural and political past and projecting it into a possible future. In fact, in the dedication section of the comic, Zé Wellington acknowledges: “a Walter Geovani por acreditar que cangaçeiros podem salvar o futuro do Ceará” [to Walter Geovani for believing that cangaçeiros can save the future of Ceará], pointing to an authorial position about the political revival of the cultural past into the future. In northeastern speculative fiction writers and artists such as Wellington and Geovani, there is a willingness to address regional concerns and awaken past cultural history to address the yet-to-come. The question of human/nonhuman life/death entanglements in the comic is traversed by the possibilities of technology used by the local community resisting the attack from the police that defends the interests and investments by the corporation called “Rios”, owned by southerners. As we will see, technology fulfills a crucial role in this futuristic comic to recover a cangaçeiro bandit from the dead and the cangaço from cultural memory. Similar to Bacurau, the lived past (in contrast to the anecdotic or romanticized one) infiltrates possible futures historicizing the conflict and decolonizing the future.

The comic combines cyberpunk with the traditional cordel literature (string literature) in the region. The story is told in three interspersed narrative levels marked by different forms of vignettes featuring an omniscient female narrator that tells the story using cordel verse and speaks to the audience, the intradiegetic narration where the story unfolds (using flashbacks and color shifts) and a parallel narrative showing social media conversations along with the story. The simultaneous occurrence of three parallel narratives (the cordelista narrator, the characters, and the social media voices) in three different temporalities decenters the lineal temporal frame. It is not a minor detail that the narrative voice framing the story is a female cordelista because although female cangaçeiros played a significant but overlooked role in that community in the 30s and 40s, that role is becoming more prominent in contemporary representations of cordel literature (string literature) (Draper 2020, p. 150). This cordelista female narrator evokes the regional twentieth-century poet Patativa do Assaré (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 8), thus framing the narration in popular culture and the cultural history of the region:

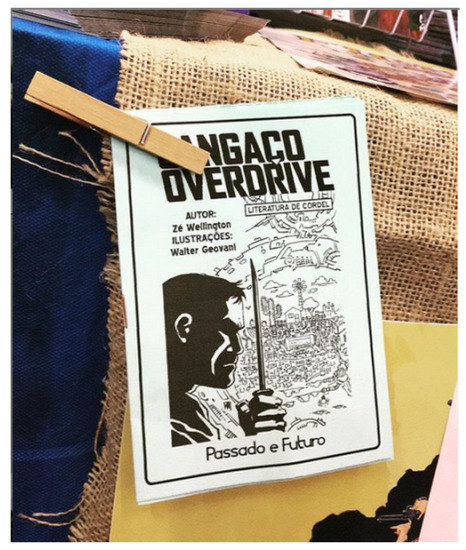

By recycling cordel literature, this comic reopens an oral channel for the voice, dialect, and lived experiences of the marginalized northeastern region. For the Comic Con Experience (CCEX), the multi-genre comic convention in 2018, Zé Wellington distributed a version of the comic as cordel literature, both as a commercial strategy to promote the book at that event but also, as the author commented, to distribute the story of Cotiara and Rosa in a connection of past and future (Wellington and Geovani 2018b).Drought, poverty, death, and a bit of sarcastic humor to deal with it all—that is how the history of cordel literature begins. A tradition that reached Brazil through its colonial past, cordel started orally, as an important way to take information to those who did not have access to it.(de la Vega 2019, p. n/n)

This sertãopunk fanzine (Figure 3) in black and white presents the comic as cordel literature and contains a long sextet poem that narrates the origin of Cotiara (Janus and Flor de Lis) and the way in which his fight in the past comes to connect with the fight of the hackers in the future (Bahia, Calango, Rosa, and Lila). The use of this regional verse couples with the plethora of colloquial expressions in the comic that are typically used in the northeast as “aperreio da moléstia” (a big preoccupation)16. In this way, cordel literature is not just a picturesque ornament, but it infiltrates the materiality of the comic and its distribution, thus redirecting the future-oriented cyberpunk to the past, the history of socio inequalities that still persist in the present, and the future, where climate conditions exacerbate those inequalities even more.

Figure 3.

Image taken from Zé Wellington’s website (the comic exhibited at the CCEX in the traditional manner hanging with a clothes pin).

The story revolves around Cotiara, a cyborg human–machine that is brought to life again. In a near future, the inhabitants of Ceará are suffering from extreme drought and the attack from the corporation “Rios”, headquartered in the south of Brazil, which employs the local police to try to occupy a hill where a community of dispossessed people has found a source of water and a means of surviving in that dry environment. In this future, technology has advanced, and Cotiara is found on a life-sustaining machine that keeps him alive. While technology is used against this community to rob them of the only source of survival by cutting their communications to force them to surrender, the members of this group also appropriate the Internet to defend themselves. Technology is therefore repurposed to decolonize and empower marginalized people17.

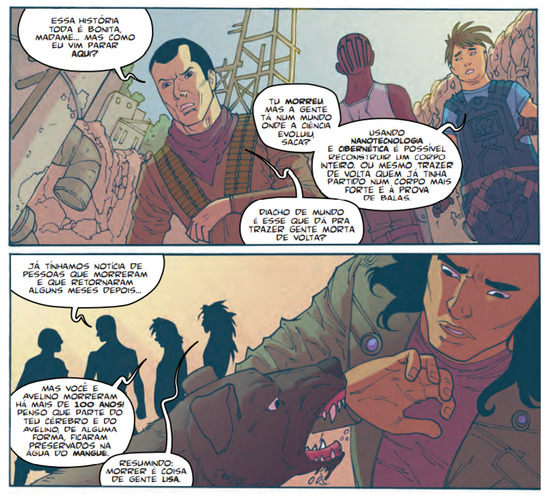

The combination of technology and nature has kept Cotiara alive for more than a hundred years and when this local community robs the box containing the body, they awaken him as a person and as a cultural and historical expression into this future, as he affirms “I have more than one life”. The characters describe the high-tech world they inhabit in that future, as can be seen in the dialogues above (Figure 4): “Using nanotechnology and cybernetics, it is possible to reconstruct a whole body. Likewise, to bring back someone who had died in a stronger bullet-proof body” (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 41, my translation).

Figure 4.

Zé Wellington and Walter Geovani. Cangaço Overdrive (p. 41). Courtesy of the artists.

However, the other characters speculate that the brains of Cotiana and his rival, Avelino, both dead more than 100 years ago, must have been first preserved by the mangrove waters (nature) and then connected to a life-support machine (technology). In this way, Cotiara and Avelino echo the techno-organic hybridity of the “cyborg” in Haraway’s terms. While these two cyborgs have the same hybrid constitution, they represent the historical division between the bandits defending the dispossessed and those such as Avelino, defending the economically powerful classes. This social division is kept in the future envisioned in the comic and signaled by the color tonalities in the comic since for the corporation owners, the tonalities are darker while for the morro inhabitants of Ceará, a variety of lighter and more harmonious colors are used, showing an authorial positionality in alignment with the latter community.

The comic opens a space to imagine a possible future where Ceará’s inhabitants have built a sustainable community that retrieves cultural dimensions from the past and the region. The place the comic imagines is, however, not rooted in a future society yet to come, but in vernacular cultural currents that are subtly deployed in the visual and textual form of the work and a subversive appropiation of technology. The comic pays homage to Pernambucan Chico Science, one of the creators of the manguebeat movement in the 1990s. However, this northeastern aesthetics is not just a textual reference but it is deeply imbued in the materiality of the future that this comic envisions. The comic fuses depictions of the flesh of the sertão (cacti, bushes) with several artistic expressions (cyberpunk, vaporwave, cordel literature) inserted in the materiality of the comic. At the same time, the idea that the mangrove that kept Cotiara´s brain alive, allowing his survival and hyperconnected body recalls maguebeat´s idea about being “caranguejos com cerebro” exposed in their manifesto (Adeodato Junior 2020). Fred Zero Quatro, Pernambuco exponent of manguebeat, called for a cultural revitalization in the 90s in Recife by resorting to the geological strata of the region formed at the intersection of rivers and mangroves from where a musical revival taking this mangrovial energy would begin. This connection produces a cybernetic circuit that, as Adeodato Junior (2020) notices, envisions “um futuro plural e cibernético alimentado ativamente por vastas raíces fincadas no pasado” (pp. 175–76). Indeed, the very first image that the reader encounters in the comic is a whole page entanglement of electrical wiring in sharp colors that also resemble the entangled roots and branches of a mangrove forest. In this sense, the comic stimulates a biocultural revitalization of the sertão to occur both inside and outside of the comic. The community members from Ceará frequently repeat “Um lugar como esse” (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 39) and speak of the value of the community. This community, however, does not coincide with the imagined community of the Brazilian nation-state, but with what Rob Nixon calls the “unimagined communities” narratively displaced from “narratives of national development” (p. 152) and thrown into invisibility and emptiness (p. 165). In the comic, the unimagined community of the Morro do Preá uses hyperconnectivity as a way to connect the environment with technology to resist the corporate and governmental efforts to throw them into the shadows, to erase them from the future imagined by extractivist power.

In the drought portrayed, the comic communicates two different responses to climate change in an already dry area: on one hand, the corporation “Rios” that sees water as a profitable commodity; and on the other hand, the group of people that use the water for their survival and that of the ecosystems, considering water as a commons. These two contending views and positions are expressed in the way the comic entangles the past and the future to develop an ethics of care in the present, but also resistance and responsibility rather than an apocalyptic, end of the world fight between two contending sides. This way of interweaving past and future activates the notion of “kinship time” proposed by Whyte (2021):

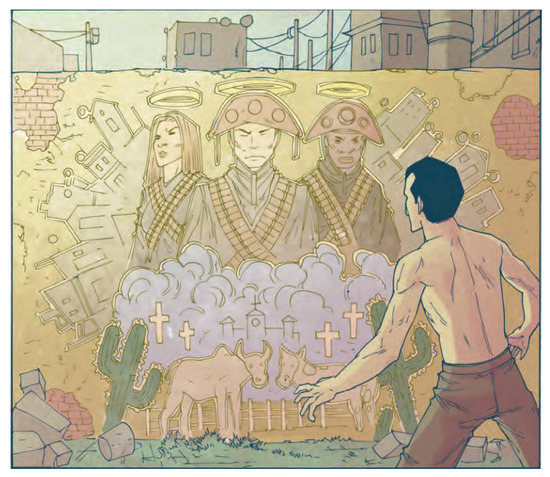

In other words, human and nonhuman kinship, climate, and economic systems are deeply intertwined and constantly influencing each other. The corporation’s view on the sertão, channeled through Rios’ owners in the south of Brazil, is that “É só mais um pedaço de terra improdutiva” [It is just another piece of unproductive land] (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 66). The comic portrays climate migrations due to the drought: it was an exodus that “dried out Ceará also of people” (p. 40). The hybrid community that formed from the left-overs of that exodus in the “Morro da Preá” comprises Afro-indigenous members, queer people, children, cyborgs, animals, and the dry vegetation—all of them connected by the same colonial and extractivist tale of the Capitalocene in the region, as suggested in the following image (Figure 5).understanding that kinship relationships are in peril, and we must take urgent action to establish or repair kinship relationships. Or else we will not have the interdependence required for responsiveness that prevents harm and violence […] kinship relationships are the basis of shared responsibilities. We do not have to separate climate and kinship systems in our understanding.(p. 21)

Figure 5.

Wellington and Walter Geovani. Cangaço Overdrive (p. 36) Courtesy of the artists.

Although the comic is set in the future, the conflict that it revolves around sends the gaze back constantly to the past, to memory and the region’s history, as we can see in Cotiara’s projection of a memory onto a wall as if a political mural. These constant flashbacks reconstruct past scenes of Cotiara’s life, who is amnesic after returning to life. However, they also appeal to the reader-viewer’s cultural and historical memory about the sertão and the place of northeastern Brazil in the construction of the modern nation. In a flashback, we learn that his father calls him Cotiara after the cotiara snake from Minas Gerais. In another crucial flashback, we learn that one hundred years ago, Cotiara had bought that piece of land where the community is now set. While he was to settle down with Flor de Lis, his girlfriend, in the past they were taken by surprise by Avelino (working for landowners), who killed Flor de Lis to then die together with Cotiara in a mutual fight.

In this community, Cotiara finds a new opportunity for the future life of which he was robbed. However, this future is not idealized. This character is burdened by the murder of his beloved cangaçeira, Flor de Lis, his new condition as human–machine cyborg and the special connection he feels with the dry environment, so much that he later chooses to get lost in the vegetation of the sertão. In the section on graphic novels inspired by cyberpunk in Chile, King and Page (2017) point out that these novels use cyberpunk to challenge cyberculture’s stimulation of transcendence of the body to instead insist on the significance of “embodiment in human experience” (p. 109). Rather than a critique of the social impacts of technology, the engagement with bodily transcendence in Cotiara and Avelino in the comic has the function of activating cultural memory on the historical conflict around land rights and access to sources of life as water in the region. When Rosa, the group’s hacker, accesses Cotiara’s memory, she recovers a judicial document: a land tenure contract stating that Cotiara had bought the land where the community is located at Morro de Preá one hundred years ago. This past recovery, made possible by technology, stands as a territorial claim coming from the past to affect the future of disadvantaged groups. The comic activates then questions about sustainable land use and territorial rights, as one of the characters exclaims ironically: “Never had a deceased returned and claimed a property but this slaughter pressed the government” (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 66, my translation). In this comic, the human–machine link characteristic of cyberpunk connects the cybernetic flows of hyper-connection with the energy of the mangrove and rivers to dynamize the question about land rights for disenfranchised communities in times of severe climate change.

Both visual productions studied incorporate how media channels the violence inflicted on those communities to encourage a reflection on how these communities are portrayed. As we have seen, in Bacurau, the TV reality show and the news channel send negative images of Bacurauans. Cangaço Overdrive fictionalizes social media and troll culture created to influence public opinion about poor areas. These vignettes in the comic show threads of conversations in social media, consisting of messages by bloggers and social media users that find the violence inflicted in those regions as a spectacle. Others represent trolls that try to influence public opinion from right-wing ideologies, for example, “TheRightHand,” which expresses: “Tem que matar mesmo esses bandidos #bbbm” (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 53). Both these voices and the cordelista narrator are directed to the reader-spectator as well as the intradiegetic world, opening for reflections on the spectacularization of violence in favelas and other marginal places, both in Brazilian society and in the genre of cyberpunk, part of the sertãopunk. Aware of the thirst for battles in cyberpunk’s readers/spectators and in a Brazilian audience who is constantly fed with violence in media, Lila, the cordelista narrator, speaks directly to the audience explaining the need to look to history or pointing out that violence should be placed in a historical context, as when Lila explains: “The reader probably likes/futurist things//But to tell the story/Trust this cordelista//We will return a hundred years…” (Wellington and Geovani 2018a, p. 13, my translation). This metanarrative strategy does not only allow flashbacks, but it also frames the future envisioned in the comic as an oral song sung by local poets, thus grounding the future-making practice not in technological advancement as in typical cyberpunk, but in traditional verse and its prediction power.

After the confrontation where the community in Ceará triumphs, not so much due to their force but to the property title found in the name of Cotiara, who in turn yielded the rights to the community, this anti-hero chooses to return to the desert of caatingas. Instead of staying with the community, Cotiara decides to make community with the cacti, reptiles, and other nonhumans, while remaining an outlaw. In this way, Cotiara’s body highlights hybrid assemblages between life, death, organic materials, and machine that make up this cyborg sertão, lifeforms that do not count as agents in human-centered sustainability discourses relying on a lineal vision of futurity and an idea of well-being for human generations.

As a recurring feature in Afrofuturism, I want to call attention to the box18 where Cotiara was found unconscious and kept alive by machines. North American Black futurism makes use of objects such as boxes in connection to time-machine rooms as a tool to summon the dead ancestors and call for reversals of time that can infiltrate dominant futures (Al-Maria et al. 2021). Similarly, the box where Cotiara is found in the comic, as I argue, echoes the museum in Bacurau, and constitutes a tool containing a body from one hundred years ago that is opened to become useful in the future of this community. Hence, the oppositional cyborgian cangaçeiro contained in the found box breaks the linear temporality to unravel a hybrid body that opens multiple speculative futures, which in turn connect with the cultural history of Afrodescendants in the American continent.

4. Conclusions: The Birdsongs of Bacurau and Ceará in the Diverging and Entangled Futures of the Sertão

Current Brazilian visual art such as the works studied here envision futures that foreground material and narrative entanglements with the past, death, and other species, mapping a path between what has been occurring and what is occurring, about the future survival prospects for dispossessed communities from this marginalized region in Brazil.

As Cielemęcka and Daigle (2019) have stated, sustainability is faced with the challenge of going beyond the human-centered focus and acknowledging diverging futures that fall outside sustainable development models. As I have argued, future fictions such as Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive show this effort by configuring what I have called ‛vernacular sustainabilities’ as critical ways to rethink the representations of marginalized communities in the sertão nordestino, and creative paths to envision possible futures that affirm the existence of marginalized and dispossessed communities. The fictional communities of Bacurau and Ceará are both on the verge of extinction, on the way to dying off and drying out, attacked by colonial and extractivist projects. With that prospect, these two audiovisual and visual-textual works speculate on possible futures where these local communities manage to defend their ways of life and fight for a future. As stated, the speculative and SF elements in these visual productions activate futurity as a temporality beyond the kind of homogeneous future projected by extractive techno-capitalism and national culture. As Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive, future fictions employing speculation and SF propose a creative and critical practice of projecting the future into the past and vice versa. Both Brazilian visual productions attempt to decolonize the future as appropriated by techno-capitalism, thus foregrounding those who have been de-futured, erased from maps, cut away from the media and communications, and left to be predated by the corporate organization of life, for whom these communities are erasable. As I have shown, these two visual culture productions attempt to decolonize the yet to come through a multispecies matrix that connects with Afro-indigenous cosmologies and the disarticulation of the life/death divide, strategically avoiding re-inscribing art into an anthropocentric human-centered discourse to, instead, explore complex future literacies grounded in alternative perceptive, lived and material experiences of the environment.

These two visual culture products emerge at a time when the concern for the future for vulnerable communities in the Capitalocene is expressed in several cultural products that resort to SF, speculative narratives and philosophies of thought in Brazil19. In this context, these two visual cultural expressions are representative of this emerging concern for the future of marginal human and nonhuman populations amidst socio-ecological inequalities. At the same time, the portrayal of the sertão and Afro-Brazilian communities locates the studied works in a long cultural tradition in Brazil that has engaged with vulnerable communities and places such as the sertão.By merging regionalist history and culture with the present concern for the near future, the studied works repurpose futuristic genres such as speculative fiction and SF to recast the question of land-ownership and management of natural resources in the drought and impoverished northeast. Through supernatural entries and evocations of the regional bacurau bird, Bacurau entangles the human community with the nonhuman through traditional oral song from the dispossessed. Similarly, the evocation of the northeastern poet Patativa do Assaré by the cordelista narrator in Cangaço Overdrive entangles this human community with oral verse, cyborg bodies, and the local patativa bird to craft a channel for the resilient voices of disadvantaged and oppressed rural communities of the northeast. Such human–nonhuman, life–death entanglements function as a critical exercise in these visual futurisms where the odd kinships of the sertão nordestino become perceptible in the audio, visual, and textual materiality of the film and the comic.

Funding

The research presented in this article was conducted during 2021. The article was finished in January 2022 with the postdoc funding from the Swedish Research Council (international postdoc, funding number: 2021-06648).

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Associate Professor Thaïs Machado Borges (Nordic Institute of Latin American Studies, Stockholm University) for the wonderful Master’s course “Geography, Regions, and People” where in critical and creative ways, we discussed utopia and the future in northeastern Brazil in ways that have inspired me to connect those topics with the film and sertãopunk. I also want to thank the anonymous reviewers for the careful and sharp comments that helped me improve and develop the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Haraway (2013) interconnects science fiction with speculative fiction and fantasy as part of the same matrix that gathers opposing forces, social reality, and fiction beyond Western binaries (nature–culture, male–female). In the Latin American context, a recent volume on speculative fiction defines this genre as “genre fiction that takes technological advances as its point of departure. Yet, in the Latin American context, as Foucault intuited, and is evident in the touchstone works of the great Argentine writers Jorge Luis Borges and Angélica Gorodischer, speculative fiction stands out as a framework from which to explore philosophical ideas and to extend literary styles and formats. It provides complex reflections on the changes that are produced in the subject and society, by positing and making possible other structures of thought” (Colanzi and Castillo 2018, p. 2). In the case of Latin American science fiction, it is also a genre with unclear boundaries that has “proved to be an ideal vehicle for registering tensions related to the defining of national identity and the modernization process [and] the uneven assimilation of technology” (Haywood Ferreira 2011, p. 3). |

| 2 | I employ the term “Capitalocene”, defined by Moore (2017) as the “age of capital—the historical era shaped by the endless accumulation of capital” (p. 3). This term dialogues with the visual productions that I study since they portray the violence of capitalist expansion and modern accumulation on marginal communities who are locally affected by environmental transformations and who are forced to disappear/become extinct so that national governments and corporations can make use of the resources in the territories that they have ancestrally occupied. The necro-violence and the extinction policies of making-die in the Capitalocene bring about responses from local resilient communities that fight for a future, as the Bacurauans in the film and the inhabitants of morro in Ceará in the comic. |

| 3 | These futuristic genres mix specificities from the geographic regions with futuristic elements inspired in cyberpunk or steampunk as in sertãopunk. Closely connected with sertãopunk, there is the sub-genre of cyberagreste that obtains inspiration from the semi-arid agreste zone in northern Brazil between the coastal forest and the sertão with futuristic features from science fiction and cyberpunk (de Sá and Silva 2020). |

| 4 | This tradition is composed of classical works such as Os sertões by Euclides da Cunha ([1902] 1980), Vidas secas by Graciliano Ramos ([1938] 2018), and Grande sertão: Veredas by Guimarães Rosa ([1956] 2018). |

| 5 | As Eduardo Gudynas (2009, p. 14) argues, there are several approaches to sustainability at play in contemporary societies ranging from “weak sustainability”, where environmental issues are considered but nature is still seen as economic asset; “strong sustainability”, where the ideal of progress is criticized but where nature is still considered from an economic viewpoint though emphasizing conservation; and “ultra-strong sustainability”, where there is a strong criticism to the idea of development and where alternative models are actively searched that consider nature a common patrimony and nature as having its own agency. The “vernacular sustainabilities” that I attempt to discuss based on Bacurau and Cangaço Overdrive resonate with the “ultra-strong sustainability” defined by Gudynas since they are grounded in the lived experiences of local communities that consider the ecology of the place a common patrimony, thus constituting an alternative to the extractive capitalist model. |

| 6 | I employed the version of the book in the Spanish translation published by Ediciones de Banda Oriental. The quote in the Spanish version is the following: “Una resurrección. Los colores de la salud volverían a la cara triste de doña Vitória. Los niños se revolcarían en la tierra blanda del corral de las cabras. Por todos esos alrededores iban a tintinear los cencerros. Y la catinga se tornaría verde. Baleia agitaba el rabo, mirando las brasas” (Ramos [1938] 2018, p. 19). |

| 7 | The phrase comes from Vidas secas and is uttered by the narrator to describe how the character Doña Vitoria projects a happier past into the future to cope with the hardships of the present. I quote the whole passage in the version in Spanish: “Doña Vitória necesitaba hablar. Si permaneciese callada, sería como uno de esos troncos de mandacaru, que se secaban y morían. Quería engañarse, gritar, decir que era fuerte y que todo aquello, el tremendo calor, los árboles transformados en esqueletos y la inmovilidad y el silencio no valían nada. Se acercó a Fabiano para ampararlo y ampararse, y olvidó toda esa realidad inmediata, los espinos y las bandadas de pájaros y los cuervos que husmeaban la carniza. Habló del pasado, confundiéndolo con el futuro. ¿No podrían volver a ser lo que ya habían sido?” (Ramos [1938] 2018, pp. 100–1). |

| 8 | See the sharp analysis and criticism to this “future” ideology in Brazil by Brazilian historian and anthropologist Lilia Schwarcz (2022) recently published in the journal Nexo. |

| 9 | The quote in the original: “São povos em disponibilidade, uma vez que, tendo sido desatrelados de suas matrizes, estão abertos ao novo, como gente que só tem futuro com o futuro do homem” (Ribeiro 1972). |

| 10 | In his approach to national perceptions of the northeast from Euclides da Cunha to the present, Goodman (2016) contents that “the peculiarities of the sertanejo (backlander) rendered him the subject of idealized visions of Brazilianness, either negatively as a lawless revolutionary or positively as full of vigor and possibility. These projections have enduringly informed notions of Northeasterners throughout Brazil” (pp. 22 and 23). |

| 11 | The film directors commented on this inspiration of Bacurau in the comic Asterix in an interview in Cannes 2019 titled “Cannes 2019: Bacurau—a violent critique of Brazilian politics”. In the well-known French comic series, local Gaulish warriors fight the Roman Empire aided by a magic potion, which has resonances with the conflict portrayed in the film and the seed that Bacurauans consume. |

| 12 | For an insightful essay about how Bacurau disarticulates the Western genre, see Girish (2019). |

| 13 | In the Cannes 2019 film interview, the films directors commented that they looked for inspiration in Afro-Brazilian communities such as quilombos in the sertão. |

| 14 | See Hidalgo’s (2021) intuitive reflection on the element of cultural criticism and geographic reference in the sub-genre sertãopunk. |

| 15 | Other emerging sub-genres that belong in contemporary Brazilian futurisms together with sertãopunk are, for example, cyberagreste, amazonfuturism and tupinipunk. |

| 16 | See Adeodato Junior (2020, p. 178) for a list of the regional colloquial expressions used in the comic. |

| 17 | In this point, my essay connects with Lidia Zuin’s included in this dossier about how Bacurau repurposes technology while shaping the ways Brazilians envision the future. |