Abstract

This article explores the genesis, proliferation, and readership of an understudied genre of religious poetry in early modern Europe. The weeping poem—a devotional literary genre combining elements of epic narrative and Petrarchan lyric that focused specifically on the religious grief of biblical figures—swept across Europe in the forty years around the turn of the seventeenth century. Although this genre was instigated by the Italian Luigi Tansillo’s 1560 Le Lagrime di San Pietro and has often been read as exhibiting a distinctively Counter-Reformation spirituality, our survey of weeping poems uncovers the surprising reach of this genre across multiple languages and even into Protestant England. The range and popularity of this specific kind of weeping poetry across early modern national, linguistic, and confessional lines shows how this constellation of texts transmitted a new form of devotional affect founded on imaginative identification with weeping biblical narrators. In other words, these poems demonstrate how interiority, rather than factional political or theological difference, could be the basis for new emotional communities of worship. Moreover, the relative obscurity of this genre to scholars prompts new questions around the viability of continuing to explore early modern European literary traditions from the perspective of nationalist/linguistic/confessional frameworks.

1. Introduction

“How deserted lies the city,

once so full of people!

How like a widow is she,

who once was great among the nations!”1

Poetic expressions of lamentation extend back to the ancient world. The book of Lamentations (quoted above) is only one of the most influential of a long tradition of poetic laments. Augustine strongly echoes the language of Lamentations when discussing the death of his friend in book IV of the Confessions, and Dante would cite these very lines in chapter nineteen of the Vita Nuova to mourn the death of Beatrice (Edwards 1999, pp. 397–98). Examples of lament can be found not only within the Hebrew poetic tradition, but also within the Mesopotamian (e.g., Gilgamesh mourning for Enkidu), the Greek (e.g., Achilles mourning the death of Patroclus in book eighteen of the Iliad, or Andromache, Helen, and Hecuba weeping over Hector’s body in book twenty-four) and the Roman (e.g., Dido’s lamentation and suicide over Aeneas’ departure in book four of the Aeneid, or Ovid’s elegiac couplets lamenting his own fate in the Tristia). Over the course of the Middle Ages, the planctus would become a common literary form in Western Europe to mourn the death of great figures and political leaders, such as the Planctus obitu karoli composed around 814 to mourn the death of Charlemagne. The medieval planctus differed from classical elegy in two ways: the speaker was often fictional—either an individual or representative type—and the subject of the lament, while often death, could also be “any kind of loss that is experienced intensely.” (Woolf 1986, pp. 157–58) As Peter Dronke has noted, the planctus had particular resonance in twelfth-century France where it was given a new intensity by Peter Abelard’s lyrical cycle of six planctus poems, focussing on the lament of Old Testament biblical figures that “not only extends but at times profoundly alters their human significance.”(Dronke [1996] 2002, pp. 53–54)2 While many planctus poems had either the Virgin Mary or Mary Magdalene as their speakers, these poems were not tied to any particular devotional movement. Moreover, as Dronke notes, given the musical notation that accompanied these poems it would be “inept” to regard them as a kind of “journal intime.” From the beginning, these poems were intended for performance rather than for private reading or, we might add, for individual devotional practice (Dronke [1996] 2002, p. 55).3 Other scenes of lament exist in Western medieval romances, e.g., in the opening lines of the Cantar de mio Cid, or in early modern chivalric epics such as those of Boiardo and Ariosto. Yet, as with classical epic, these laments are part of a broader narrative and serve to highlight the pathos of a particular scene or the depth of emotion of a certain character. Similarly, many were performed aloud rather than read privately on the page, and there is no evidence to suggest that these laments served as models for devotional practice—with perhaps the exception of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, whose imitation of the penitence of Amadís of Gaul in chapters 23–26 of the 1605 Quijote is presented as a comical misreading that takes its source text all too seriously.

From a devotional perspective, although Mary’s emotional pain at the cross was the focus of a number of sung hymns in the late middle ages, such as the “Stabat Mater dolorosa”, the practice of weeping gained new importance as a mode of contrite penitence for Christians in the early modern period. In the 14th century, Saint Catherine of Siena distinguished between five different kinds of tears, pointing out that certain kinds of tears did not lead to spiritual health, while others could lead along a devotional path of tears that were increasingly perfect in their love of Christ (Gonzáles Roldán 2009, p. 110). Weeping as devotional practice was given new emphasis with the advent of the devotio moderna movement in the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which emphasized more intimate and personal techniques of prayer, including the imaginary immersion and projection of oneself into a scene from the Gospels as developed in Ludolph of Saxony’s Vita Christii. The technique became crucial for Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises and was important in Counter-Reformation Catholic Spirituality.4 A notable new emphasis was placed on weeping in the period, as Catholics were “elevating those inner emotions, which at the best of times flowed down from the fountain of God’s mercy, to the status of a reliable and verifiable means of knowledge”. Crying in public became a widespread fashion, and Pope Clement VIII wept so often and so copiously that people sometimes questioned the authenticity of his tears (Imorde 2013, p. 267). Historians of Counter-Reformation piety, however, have frequently focused on processions, sacraments, and the liturgy, bypassing the flourishing devotional culture that emphasized individual affective experience.5 As Simone Laqua-O’Donnell argues, piety was not simply a mode of thought that early modern Catholics “only switched on at church doors or under the procession banner” (O’Donnell 2013, p. 368).

The genre of lagrime poetry, which developed in late sixteenth-century Italy with Luigi Tansillo’s 1560 Le Lagrime di San Pietro and quickly gained popularity throughout Western Europe, combined this renewed emphasis on weeping and contrition as devotional practices with lyrical compositions that described the penitential emotions experienced by figures in the Gospels and by early saints. This genre was a unique poetic form that combined elements of Petrarchan lyric and epic topoi with a narrative—often interior—journey. As opposed to earlier depictions of lamentation, such as those found in planctus texts, in epic, or in romance, these early modern weeping poems invited their audience to share in imitative grief as private devotional practice. In other words, these poems not only provided literary entertainment, but also furnished their readers with an emotional script to follow. As this article will demonstrate, these poems were not only popular among Italian Catholics but also inspired an early modern genre with international trans-linguistic and trans-confessional reach. As we will show, the enormous popularity of this genre in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries yields a rich archive of examples across the continent, the channel, and the confessional divide. Of particular interest is the case of this genre in early modern England, where the genre was not only adapted for an English readership but indeed was reshaped for Protestant sensitivities. At a time when English Protestants jettisoned iconographic devotion, these weeping poems provided figures of imaginative identification and emulation for worshippers. One of the key reasons that the genre has not been adequately recognized or explored is due, in part, to the ongoing national character of early modern literary studies. While scholars have recognised the influence of Tansillo on Spanish, French, and English literary production (as will be discussed below) none have examined weeping poetry as a pan-European cross-confessional genre that provided a new form of emotional identification for individual devotion.

In this article, we will consider these texts from the perspective of affective links between seemingly disparate emotional communities. Barbara Rosenwein’s notion of the “emotional community” seems useful for exploring the phenomenon of weeping poetry as a pan-European genre. Extending beyond social groups, emotional communities are groups united by “systems of feeling.” Rosenwein aims to uncover what these communities (and the individuals within them) define and assess as valuable or harmful to them; the evaluations that they make about others’ emotions; the nature of the affective bonds between people that they recognize; and the modes of emotional expression that they expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore (Rosenwein 2002).

Emotional communities that valued an interactive reading practice of weeping and penitence through identification with biblical figures including Saint Paul, Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary, and King David extended beyond many traditional boundaries in early modern Europe. Their affective links help explain the durability and adaptability of the weeping poem across early modern national, linguistic, and confessional lines. More important, these poems contributed to a shift in the way individuals saw themselves in relation to society. By providing a script for emotional identification with a community of saints and Biblical figures, these texts contributed to a growing international sense of the Christian as an individual who chooses to join communities of worship based on emotional identification, rather than on the basis of rational conviction or political persuasion.

2. Tansillo and the Lagrime Genre in Italy

Italian lagrime poems were nearly all written in ottava rima—the standard rhyme scheme for narrative poetry popularised by works such as Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso and Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata. Focusing on the penitence of various figures from the Gospels, they featured a mix of narrative and lyric content and were occasionally presented as a new type of epic. The poem that launched this genre was Luigi Tansillo’s 1560 Le Lagrime di San Pietro, which describes the penitence and weeping of Saint Peter over the three days following his denial of Christ. Tansillo’s poem went through three main editions in late-sixteenth-century Italy. The first, a short version of 42 octaves printed in Venice, was published under the pseudonym of Cardinal De Pucci, as Tansillo’s early poem Il Vendemmiatore was deemed too lascivious for good Catholics and caused the poet’s name to be added to the 1559 index. After Tansillo’s name was removed from the 1564 Tridentine index, this version was reprinted five times between 1571 and 1589 bearing Tansillo’s real name.

Prior to his death in 1568, Tansillo had prepared a much longer version of the poem in 15 canti, but did not publish it. This manuscript version was heavily edited and modified by Giambattista Attendolo, a Capuan priest, philosopher, and man of letters, who organized the poem into thirteen “pianti” mirroring the stations of the cross, and had it published in 1585 (Mutini 1962). This edition appears to be the one that inspired imitators abroad, and was frequently republished in Italy alongside other lagrime poems and in various collections of rime spirituali published in the last quarter of the sixteenth century. Attendolo’s edition was reprinted at least 14 times by 1613. While it omitted more than 360 stanzas and was rife with editorial errors, as Jesus González Miguel has demonstrated, it was the version of the poem with which most Italian readers would have been familiar (González Miguel 1979, pp. 230–40).6 In 1606, the Venetian publisher, Barezzo Barezzi discovered a manuscript copy of Tansillo’s fifteen canti Lagrime on a visit to Naples and hired Tommaso Costo to correct Attendolo’s errors. However, Costo’s edition, which was accompanied by interpretive allegorical paratexts by Lucrezia Marinella, was not reprinted until 1788.7 In Italy, Tansillo’s poem served as the model for Erasmo di Valvasone’s Le lacrime di Santa Maria Maddalena (1586), Torquato Tasso’s Le lagrime della beata Vergine and Le lagrime di Cristo (1593), and Angelo Grillo’s Lagrime del penitente (1594), among others.8 The poem also inspired a number of musical compositions, such as Orlando di Lasso’s 1594 setting of Tansillo’s verse to music in a cycle of 20 madrigals and numerous imitators in France, Spain, Portugal, and England, as will be discussed below.

Despite such influence, Tansillo’s poem has suffered from profound critical neglect, as both Virginia Cox and Amedeo Quondam have noted; no modern edition exists of the work, and it is barely mentioned in the 1999 Cambridge History of Italian Literature (Cox 2011, pp. xiv–xv; Quondam 2005, p. 127; Brand and Pertile [1999] 2004, p. 258). Moreover, no work to our knowledge has yet recognised that Tansillo’s poem launched an international genre of weeping poetry across confessional and linguistic divides. Of the small bibliography that exists on Tansillo’s Lagrime, Erika Milburn has recently demonstrated how a manuscript dating to 1550 contains sixty-one stanze that appear to be an early version of the Lagrime di San Pietro (Milburn 2003, pp. 61–65). Tobia Toscano has examined the publication history of the work, noting the significant changes made by Attendolo due to his distaste for any elements that appeared to be in imitation of Ariosto—such as arbitrarily changing from canti to pianti and the omission of exordia and epilogues from each canto (Toscano 1987, pp. 437–61). Francesco Flamini, in his introduction to the 1893 edition of Tansillo’s Egloga e poemetti is quite critical of Tansillo’s poem and its lack of action, pointing out how Tansillo draws heavily from Jacopo Sannazaro’s 1526 De partu Virginis—translating a portion of the work directly in canto VIII—in order to construct a classicizing language for Christian devotion (Flamini 1893, pp. LXXXVII–LXXXI).9

The majority of the Lagrime di San Pietro depicts Saint Peter’s emotional outpouring and continual penitence as he recalls his sins and his denial of Christ. Peter also reacts to various sites around Jerusalem, such as the hanging body of Judas, and the three empty crosses on the mount of Calvary. He has a number of visions that cause him to weep, including the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and the resurrected Christ, and finally weeps again when meeting with the apostle John who recounts Christ’s passion. While the poem features a narrative tracing Peter’s spiritual growth and redemption through his tears, his emotions and thoughts are expressed primarily through lyric monologues.

The use of the lyric monologue to express devotional affect was not novel in spiritualized Petrarchan lyric in the period. It was already present in such works as Pietro Aretino’s 1534 I Sette salmi de la penitentia di David, Girolamo Malipiero’s 1535 Petrarca Spirituale, Vittoria Colonna’s 1556 Pianto della Marchesa di Pescara Sopra la Passione di Christo, and in a multitude of shorter devotional lyric compositions.10 Tansillo’s poem, however, combined these lyric moments with a broader epic narrative of penitence and redemption. Moreover, it appears to have been received as more than a simple literary experiment of adapting vernacular forms (epic and lyric) to suit a new religious sensibility. Instead, readers described their experience as launching them into their own Petrine flood of tears. In a letter to Attendolo from February 1585, Scipione Ammirato described his reaction to what appears to have been a manuscript edition of the poem and encouraged Attendolo to publish:

Io ho da rendere infinite grazie a V.S. delle Lagrime di San Pietro, le quali non ho potuto contenermi di leggere in 30 ore… Me han cavato le lagrime da gli occhi in tanta abbondanza che è una maraviglia

I must give infinite thanks to your grace for the Tears of Saint Peter, which I could not stop reading for 30 h… The abundance of tears they have drawn out from my eyes is a marvel.11

Such a reaction to Tansillo’s poem was not uncommon. In the preface to a 1587 reprint of Attendolo’s edition the Genoan printer Girolamo Bartoli writes that he was moved to reprint the edition because “mentre esprime Pietro piangente il suo fallo, invita a piangere i propri errori, chiunque affetuosamente il legge”, i.e.,“while weeping Peter expresses his fault, he invites whosoever affectionately reads to weep for his own errors.” (Tansillo 1587, p. a5r.).

The 1587 reprint of Attendolo’s edition was incredibly popular and was frequently reprinted with the same organisation of complementary poems and paratexts. In this edition, Tansillo’s poem was followed by: (1) Torquato Tasso’s sonnet “Dialogo Spirituale”, which dismisses the “dolce inganno” of human love to focus on weeping and the crucifixion; (2) Valvasone’s Lacrime di Santa Maria Maddalena, a narrative lyric similar to Tansillo that explored Mary Magdalene’s weeping and internal struggles following the Passion; (3) Orazio Guarguante’s Eccellenze di Maria Vergine, an extended blason to the Virgin Mary and her virtues; and (4) Angelo Grillo’s “Capitolo al Crocefisso”, a brief poem that focuses on the impossibility of conveying Christ’s pain and uses frequent imperatives to ask for a deeper religious experience. The edition also included Ammirato’s prefatory letter (as discussed above) and three prefatory sonnets. This arrangement of texts and paratextual materials was republished 12 times before 1618 with very minor changes (the same prefatory sonnets, the same arrangement of texts, i.e., Tansillo, Tasso, Valvasone, and Grillo, often with only a new letter from the publisher to the dedicatee or to the reader). At times, other texts were added, such as Tasso’s Lagrime di Maria Vergine and other brief weeping poems by Angelo Grillo. (Nuova raccolta di lagrime di piu poeti illustri 1593).12 Given the popularity of this edition and its paratexts, it appears that if readers read other texts in the genre with the same amount of emotion as Ammirato and Bartoli read Tansillo’s poem, these books could function as portable devotional manuals for private spiritual practice. Indeed, the paratextual sonnets and at times the letters from publishers are at pains to emphasize that these texts, particularly Tansillo’s, should be read as both literature and devotional material.

3. Weeping Poetry as a Pan-European Genre: 1550–1650

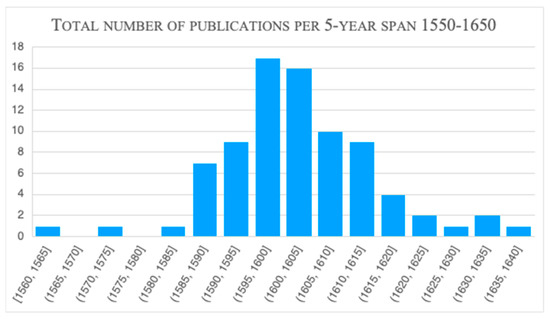

To investigate the extent of the genre of weeping poetry, we compiled an initial survey of published weeping poems or collections of such poems from the years 1550–1650 in Italy, Spain, France, and England (see Appendix A). To avoid confusion, only poems were included that were clearly within the genre of weeping poetry established by Tansillo—namely, poems that had epic pretensions, that often used lyrical narrative, and that featured the weeping of biblical figures. Sermons and poems in manuscript were excluded from this initial survey, though they may be included in a more comprehensive study in future. Our survey found that 81 texts were published in the period 1550–1650, many of which were printed in portable formats, suggesting that they would have been carried around for devotional purposes: 29 were published as octavos, 16 as duodecimos, and 4 as sedicesimos. We identified 21 poems in Italian, 20 in French, 29 in English, 8 in Spanish, and 2 in Portuguese.

This survey not only demonstrates the popularity of the genre, but indeed illustrates the undeniable impact of Attendolo’s 1585 edition and Bartoli’s 1587 reprint with the paratexts mentioned above. Sixty-nine weeping poems were published in the years 1585 to 1615 in Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, and England, which amount to nearly 79% of the weeping poems published in the 100 years we scrutinized (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total Number of Publications of Lagrime Poems per 5-Year Span 1550–1650.

The pairing of Attendolo’s version of Tansillo’s poem with Valvasone’s Lacrime della maddalena in 1587 appears to have influenced the publication of such poems in other European countries as well. While Mario Praz has noted that Southwell’s Saint Peter’s Complaint is indebted to Tansillo, he neglects the impact of Attendolo’s edition as Southwell pairs this poem with Saint Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares (Praz 1924, pp. 273–390). The practice of combining a version of Tansillo’s Lagrime di San Pietro with other poetry in the genre also occurs in France. As is well-known, Tansillo’s poem served as a source for François de Malherbe’s 1587 Les Larmes de Saint Pierre. In 1602, a collection published in Rouen pairs poetry by the Sieur de Valagre with a variety of other lagrime poems, including the tears of Saint Peter (Malherbe), of the Virgin Mary (translated from Tasso), of Jesus (translated from Tasso), and of Mary Magdalen.13

Similarly, in 1607, Cristóbal de Mesa published Valle de lágrimas y diversas rimas; the first part of this collection included a series of weeping poems focusing on the tears of the prophet David, the Virgin Mary, Saint Peter, Mary Magdalene, Saint Francis, and Saint Augustine. The prefatory dedication in the volume underlines important figures who wept in both the Christian tradition, i.e., Old Testament prophets, Christ himself, the Apostles, Greek and Latin Church Fathers, and the classical, i.e., Horace, Virgil’s Aeneas, Lucan’s Cesar, Alexander the Great, Heraclitus, and Democritus (De Mesa 1607, §6r). Once again, the devotional intent of this collection is emphasized; Mesa makes the clear suggestion that the dedicatee, Don Lorenzo Suárez de Figueroa y Córdoba, could emulate the same emotional experiences as great thinkers and leaders of the past through weeping. Indeed, the genre was quite popular in Spain. González Miguel has shown how Tansillo exerted a profound influence in early modern Spain and Portugal with three imitations/translations that have been lost, seven versions of the 42 octave poem, four of the 13 pianti edition and nine weeping poems all written prior to 1610 (González Miguel 1979, pp. 239–329). Even Miguel de Cervantes directly imitates Tansillo in “Las lágrimas de San Pedro,” a poem included as part of the interpolated novella “El curioso impertinente” in the 1605 Don Quijote (Johnson 2017, p. 495).14

4. Weeping Poetry in England: A Case Study

Weeping poetry can be found with surprising frequency in England, although that country had been officially Protestant since the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558. This transfer of the genre across not only linguistic but also confessional lines makes England a particularly interesting case study for illustrating how overlapping emotional communities could form around particular constellations of texts. In late sixteenth and early seventeenth century England, weeping poetry was transformed from a distinctively Catholic genre to one that could be used by Protestants in devotional contexts. The particular affective contours of weeping poetry, emulative grief above all, enabled this genre to cross between what are usually thought of as quite different emotional communities bound by confessional, national, and linguistic borders. As readers imitated the grieving saints of weeping poetry, they were drawn into a broader group of holy mourners who were not limited to one country or sect. Weeping poetry provided readers with emotional scripts that shaped their devotional practices and constituted their identities as worshipers through interiority.

Weeping poetry in England can be traced to two different instigating texts, both of which were drawn from Italian Catholic sources. These sixteenth-century texts inaugurated a mode of devotion in England focused on tearful penitence and the emulation of exemplary figures from the Bible. The first is Sir Thomas Wyatt’s Certayne psalmes chosen out of the psalter of David, commonlye called the .vii. penytentiall psalmes (printed 1549), verse paraphrases of the penitential psalms connected into a narrative after the model of Pietro Aretino’s I Sette salmi de la penitentia di David (1534) (Hamlin 2004, p. 112). This narrative follows the process of David’s repentance for his adultery with Bathsheba. Although this linked series of poems was based on an Italian Catholic model, and the precise confessional leanings of Wyatt himself are up for debate, the publishing history indicates that the volume was at least printed as an explicitly Protestant polemic, directed to the “godly reader” (that is, the Protestant reader) at a moment of intensifying reform.15 Wyatt’s text provided a model for using the text of the Bible itself as the template for an extended narrative, and in its printed version self-consciously translated Aretino’s Petrarchan religious grief into a mode more palatable for Protestants.

The second early and heavily imitated model of a weeping poem is Robert Southwell’s St. Peters Complaint (printed 1595), written by a martyred Catholic priest but later circulated widely and publicly, with at least fifteen editions between 1595 and 1640. This poem, often paired with the prose work Saint Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares (originally printed 1591), recounts Peter’s grief after his abandonment of Christ and memorializes his confession, without providing any straightforward conclusion or absolution within the frame of the narrative (Stegner 2016, p. 169; Kuchar 2008, p. 36). This piece was clearly modeled on Tansillo; Southwell’s holograph draft of a translation of Tansillo survives, as do two shorter poems that seem to be intermediate sketches or drafts for the full Saint Peters Complaint, gradually transforming the translation into an original work (Southwell 1967, p. lxxxvi).

Southwell’s highly popular poem and its prose accompaniment were imitated by both Catholic and Protestant poets—although the Protestant poets most often took the core conceit of the poem while stripping it of its specifically Catholic elements (Kuchar 2008, p. 46). Surprisingly, however, even as Southwell’s posthumously printed works were marketed to a predominantly Protestant audience, some editions were visibly Catholic in their title page iconography (Marotti 2005, p. 28). Southwell’s Catholicism was not entirely obscured; rather, it was reimagined as useful for the service of Protestant readers. Southwell’s Saint Peters Complaint, along with his prose Saint Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares, provided a bridge between a Continental Counter-Reformation tradition of poetry and an English Protestant one, and thus provided a model of imaginatively-engaged sorrowful devotion.

The two primary biblical sites for English weeping poetry, following Wyatt’s and Southwell’s early formation of the genre, are David’s life (and particularly his repentance after killing Uriah) and the Passion narrative. These two biblical moments remained central in the English tradition of weeping poetry through the mid-seventeenth century. As the juxtaposition of Wyatt’s Penitential Psalms and Southwell’s St. Peters Complaint shows, however, the story of English weeping poetry is bound up with a fundamental tension in attempting to make an originally Catholic genre appropriate for a Protestant readership. Later instantiations of the genre did not simply cover up or wholly reinterpret the Catholic origins of weeping poetry. These two central biblical narratives in themselves appealed to Protestant emphasis on the power of the vernacular Bible and the necessity for individual and communal repentance. Moreover, the affective mode of these texts invites readers to engage in a new kind of devotion of their own. The genre of weeping poetry does not assume a passive reader but, from Tansillo and Southwell on, draws the audience into imitative devotional participation (Shell 1999, p. 62). This participatory mode crossed linguistic and confessional borders to create an international genre even as English attempts to jettison the Catholic past were at their height.

As Gary Kuchar writes, religious grief is “a set of discursive resources which allow writers to express the implications that theological commitments have on the lived experience of faith” (Kuchar 2008, p. 2). Even as reformers changed the institutional rituals surrounding penitence, weeping poetry transferred the experience of religious grief between Catholic and Protestant contexts through exemplary biblical figures. Although the two originating examples of the genre of the weeping poem, Wyatt’s Penitential Psalms and Southwell’s St Peters Complaint, concern male mourners, the genre as a whole contains a high proportion of female weepers, suggesting that “divine sorrow” was seen as a particularly feminine gift (Kuchar 2008, p. 124). The weeping women of the Bible were seen as “important analogues for Protestant piety,” able to provide an embodied image of ideal English devotion (Hodgson 2015, p. 8). As the poets of the English Reformation used the mourners of the Bible to imagine Protestant modes of repentance and grief, they delved deeply into depictions of female interiority in order to offer their readers models to emulate. Conflicted female weepers, from Bathsheba to Mary Magdalene, offered imaginative models from which to learn.

A closer look at an assortment of weeping poetry from the decades on either side of 1600 shows how the predominantly Catholic affective modes of the genre were translated to a Protestant idiom. The material and stylistic variety of these texts points to how widespread the interest in weeping poetry became, and how diverse its presentation. Some texts were overt “corrections” of Southwell’s writing. Gervase Markham, an incorrigible author of dozens of books ranging from horsemanship manuals to religious poetry, wrote two separate weeping poems around the turn of the century: The teares of the beloved: or, The lamentation of Saint John, concerning the death and passion of Christ Jesus our saviour (1600) and Mary Magdalens lamentations for the losse of her maister Jesus (1601). Mary Magdalens lamentations is explicitly modeled on Southwell’s prose Saint Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares, but rewritten in a Protestant key. Similar to several other English weeping poems, it purports to show the phenomenology of grief in a female mind. Mary’s grief is both an almost erotic love for the absent Christ and a desire to undergo the same suffering he did; these intertwined desires are presented for emulation.

In bridging the emotional gap between Catholic and Protestant reading communities, Markham and other imitators of Southwell did not necessarily change the emotional valences of their appeals. Kuchar suggests that Southwell’s Peter serves as an “apostolic model of true compunction before Christ,” inviting the reader to recognize himself as part of a distinctively Catholic communion of saints (Kuchar 2008, p. 36). However, even staunchly Protestant imitations invite readers to see themselves as part of a devotional community that includes the saint. For instance, Markham writes, in his introduction to Marie Magdalens Lamentations, “And Marie showes us when we ought to beat/Our brasen breasts, and let our robes be rent….”(Markham 1601, sig. A2r). Mary Magdalene’s grief is meant to teach a right response to the passion narrative. She models the devotional movements (literal or figurative) that should follow a full realization of Christ’s sacrifice.

Markham also echoes Tansillo’s distinctive concern with wedding epic and religious verse. Markham’s Marie Magdalens Lamentations includes the figure of Colin, a well-known stand-in for Spenser, as the narrator of the introduction. As has been noted, this displaces Southwell from a privileged place of inspiration and substitutes the decidedly Protestant Spenser as the tutelary spirit of the piece (Shell 1999, p. 76); more than this, it conjures The Faerie Queene and introduces the idea that Marie Magdalens Lamentations can be read in the vein of an epic poem—if a short one. This comparison elevates the text and ties it to the international genre as inspired by Tansillo.

Other examples also insist on the generic singularity of this kind of verse. At the beginning of his Odes in imitation of the seaven penitential Psalmes, the Catholic Richard Verstegan successively discards Ovid’s “vaine conceits of loves delight,” Virgil’s “warres and bloody broyles,” and Sophocles’ “tragedies in doleful tales,” insisting that instead “unto our eternal king/My verse and voyce I frame”(Verstegan 1601, sig. A2v). By systematically comparing himself to three major models of classical genres, Verstegan sets up his own poetry as an equivalently unique poetic kind. In the epistle “To the courteous and friendly Reader” at the beginning of Saint Peters Path to the Joyes of Heaven, William Broxup similarly begs patience for his “imperfect worke”(Broxup 1598, sig. A3r). He explains, “Though Cicero were eloquent, Ennius was bluntish, high stile is not herein used, but a plaine Decorum touching the matter, a work roughly hewed out of a hard rocke.” This description of his project disavows classically ideal style, but at the same time asserts for himself a plainness that is implicitly more valuable than Ciceronian ornamentation because it suits his subject matter. Again, he sets this genre of poetry aside from classical precedent, and thus elevated above it. Just as Tansillo’s Lagrime featured a novel blend of epic narrative and lyric monologue, Verstegan’s and Broxup’s texts depict a new genre that uses but transcends epic.

Aemilia Lanyer’s Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611) picks up the emulative mode of sorrowful devotion and presents it not just through a female character, but by an explicitly female poet for a specific female audience. After a series of dedicatory letters to important female patrons, Lanyer describes the Passion from a distinctively female point of view, including a digressive vindication of Eve by Pilate’s wife. The key to this text is its multilayered, and multidirectional, depiction of emulative religious sorrow. Even as Lanyer depicts herself emulating the devotion of her female dedicatees, she provides them a narrative depicting the virtuous sorrow of female figures in the Passion narrative. Moreover, a Jesus explicitly imagined as feminine provides an even stronger basis for women’s emulation (Hodgson 2015, p. 57). Even non-noble readers of her text are invited to see themselves as part of a devotional community, joining the female mourners of the passion narrative along with the exemplary women to whom Lanyer dedicates her text.

Lanyer’s poem is not a straightforward imitation of Southwell, or Tansillo for that matter; it was published in 1611, after the first flush of enthusiasm for weeping poetry had died down (although it should be noted that Southwell’s Saint Peters Complaint had been reprinted as recently 1609, and was printed again several times throughout the 1610s and beyond). Lanyer also does not focus on a singular weeping character throughout the narrative, but rather apostrophizes several different individuals and groups to describe their complaints at the passion (Lewalski 1998, p. 52). However, a direct link to continental models of weeping poetry is certainly possible, as Lanyer herself could have been familiar with the Italian sources of this generic tradition; her father was a Venetian who had come to England to be a court musician. Moreover, consciously or not, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum can be read as part of the international genre of weeping poetry for two key reasons: Lanyer is very clear about the epic pretensions of her piece, and she trains her focus on the affective experience of grief. Virtuous mourning suffuses the narrative: the grief of Jesus himself becomes a focal point early in the text (Lanyer 1611, sig. b2r). Moreover, the third section of the main text, “The teares of the daughters of Jerusalem,” claims tears as a primary means for moving wicked hearts to mercy. Throughout, grief is portrayed as the appropriate affect for devotional experience.

Lanyer signals the epic nature of her piece by blending classical and biblical allusions in her prefatory matter. In an introductory letter “To all vertuous Ladies in generall,” she invites her gentlewoman-readers both to “let the Muses your companions be…whose Virtues with the purest minds agree” and to “annoynt your haire with Aarons pretious oyle” (Lanyer 1611, sig. b3v). They are encouraged to emulate both classical and biblical figures in almost the same way. This signals, from the beginning, that Lanyer conceives of her poetic project as something more than a bare retelling of the passion narrative. Lanyer’s paratexts, like Tansillo’s, insist that her verse must be read simultaneously as a literary work and as an entrance into personal devotion. As Lanyer’s text shows, even through the early seventeenth century English weeping poetry continued to draw strength from the distinctive features of the international genre.

The manuscript tradition offers us a further glimpse into the genre of weeping poetry. Although the scope of this article does not allow us to examine these manuscript poems in depth, we have found examples that suggest that the enthusiasm for weeping poetry spread beyond print sources.16 One fascinating but unpublished narrative that provides a glimpse into this manuscript tradition is Davids Harp Tuned unto Teares Aswell in himself as in his Children, written by the mapmaker and genealogist John Speed in the last decade of the sixteenth century. The manuscript in the Beinecke Library is dated 1628, but the poem’s dedication to Queen Elizabeth I suggests that it was written considerably earlier.17 The text is composed of thirteen chapters, most of them consisting of separate monologues, in two books. The first book follows David’s sin with Bathsheba from his first sighting of her to his final mourning after the death of their son. The second (unfinished) book tells the story of the rape of David’s daughter Tamar by her half-brother Amnon, and her brother Absalom’s subsequent killing of Amnon and revolt against David. While some chapters follow the biblical narrative, others (such as “Bethshabaes [sic] tears” and “Urias Complaint”) are extended tearful soliloquies by particular characters in the drama. This mixture of narrative and lyric points back to potential influence from continental weeping poetry.

However, the theology and tone of Davids Harp is militantly Protestant. In its dedication to Queen Elizabeth, this text explicitly draws out the biblical parallels between David’s oppression by Saul and Elizabeth’s supposed oppression by the tyrannical forces of the Pope (Speed n.d., p. 38). Perhaps partly because the text is directed toward this privileged female reader, the volume is extremely interested in the female experience of grief, guilt, and repentance. Both Bathsheba and Tamar are given extended monologues in which they explore their multiple reactions to what has been done to them with great depth and emotional intensity. The extended focus on these women’s experience of repentance and mourning gives readers a detailed template to follow in expressing their own religious sorrow. It is impossible to know whether Speed would have sought publication if he had finished this text; what is clear is that his manuscript exhibits all the features of the weeping genre that swept Europe at the turn of the seventeenth century. Although Speed’s text remained private in its unfinished, unprinted form, it partook in the practices of a much broader emotional community as it invited its privileged reader (Elizabeth I) to join in with sorrowful emulative devotion.

The English engagement with the continental genre of weeping poetry shows how widely the genre spread through overlapping confessional communities. This is not only the story of one decisive text being received in multiple linguistic contexts, even though Tansillo’s Lagrime di San Pietro was the catalyst for the outpouring of weeping poetry. Even as translations of Tansillo’s Lagrime (such as Malherbe’s Les Larmes de Saint Pierre and Southwell’s Saint Peter’s Complaint) served as a bridge from Italian to other languages, the rapid spread of additional editions and imitations suggests a deeper interest in the genre. The sheer volume of examples of weeping poetry we have identified, and the variety of narrators and presentations, points to a widespread and diffuse cultural phenomenon. The affective contours of the weeping poem as a genre spread throughout Europe in a forty-year period, crossing linguistic and confessional barriers and creating a devotional mode accessible to a wide range of readers.

Our identification of this international genre suggests the need for current scholars, no less than our early modern subjects, to be more willing to look beyond linguistic and confessional barriers. We have begun to compile examples of weeping poetry from Italy, France, Spain, and England, but more well may exist from Germany and the Low Countries, or in the vast archive of international neo-Latin verse, as well as in the manuscript traditions of all these languages. Likewise, other genres doubtless spread in similar ways across national boundaries, creating international affective modes that drew readers into emotional communities centered on constellations of texts. The international reach of the weeping poem as it moved between linguistic and confessional contexts suggests the porousness and adaptability of emotional communities, as well as the durability of devotional sorrow. It is hoped that future studies will be able to add to this complex picture through explorations of specific case studies, comparisons of manuscript and printed traditions, and consideration of the difference between poetry as performance and the increase in silent individual reading.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to all aspects of the research and writing of this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our thanks for the internal travel funding for Bryan Brazeau from the Warwick-Newberry Transatlantic Fellowship administered by the Warwick Centre for the Study of the Renaissance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of Weeping Poems Published from 1550–1650 in Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, and England.

Table A1.

List of Weeping Poems Published from 1550–1650 in Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, and England.

| Date | Last Name | First Name | Title | Publisher | Place | Language | USTC/ STC | Format |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1560 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lagrime di S. Pietro del Reverendiss. Cardinale de’ Pucci. | Francesco Rampazzetto | Venice | Italian | 862807 | 8o |

| 1571 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lagrime di S. Pietro del S. Luigi Tansillo. | Bernardo Giunta | Venice | Italian | 829007 | 16o |

| 1585 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lagrime di S. Pietro del S. Luigi Tansillo da Nola mandate in luce da Giovan Battista Attendolo da Capua | Gio. Battista Cappello et Giuseppe Cacchii | Vico Equense | Italian | 858051 | 8o |

| 1586 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lagrime di S. Pietro del Sig. Luigi Tansillo, gentil’huomo napolitano. | Vittorio Baldini | Ferrara | Italian | 858052 | 12o |

| 1587 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de Sainct Pierre imitées du Tansille, au roy | ? | Paris? | French | ? | ? |

| 1587 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di S. Pietro del Sig. Luigi Tansillo di nuovo ristampate con nuova gionta delle lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo Valvassone, et al.tre rime spirituali, del molto R. D. Angelo Grillo… | Girolamo Bartoli | Genova | Italian | 858053 | 8o |

| 1587 | Gálvez de Montalvo | Luis | Lágrimas de San Pedro (in Primera parte del thesoro de divina poesia) | Juan Rodríguez | Toledo | Spanish | 338790 | 8o |

| 1588 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di S. Pietro del Sig. Luigi Tansillo di nuovo ristampate con nuova gionta delle lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo Valvassone, et al.tre rime spirituali, del molto R. D. Angelo Grillo, di nuovo ristampate | Marcantonio Bellone | Carmagnola | Italian | 858054 | 8o |

| 1589 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lacrime di S. Pietro del signor Luigi Tansillo gentilhuomo napolitano. Di nuovo corretto et ristampato. | Leonardo Pontio | Milan | Italian | 858055 | 4o |

| 1589 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di S. Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo; con le Lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria del S. Horatio Guarguante da Soncino | G. Vincenti | Venice | Italian | 858056 | 8o |

| 1591 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di S. Pietro del S. Luigi Tansillo, mandate in luce da Gio. Battista Attendolo da Capoa con gli argomenti di Giulio Cesare Capaccio, e figure ad ogni pianto. Aggiuntovie le lagrime della Maddalena del S. Erasmo da Valvasone | Gio. Battista Capelli | Naples | Italian | Found in Flamini and repeated in Boccia but not in USTC or Edit16 | 16o |

| 1592 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo; con le Lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo di Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria, del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino | Simon Cornetti et fratelli | Venice | Italian | 858057 | 8o |

| 1595 | Breton | Nicholas | Marie Magdalens love and A Solemne Passion of the Soules Love | John Danter | London | English | 3665 | 8o |

| 1595 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint, with other poems | John Wolfe | London | English | 22955.7 | 4o |

| 1595 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaynt With other poems | James Roberts for Gabriel Cawood | London | English | 22956 | 4o |

| 1595 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint with other poemes | John Windet for John Wolfe | London | English | 22957 | 4o |

| 1595 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de Sainct Pierre, et autres vers chrestiens sur la Passion par Rob.Estienne | Mamert Patisson | Paris | French | 53084 | 8o |

| 1595 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lagrime di S. Pietro descritte dal Signor Luigi Tansillo e nuovamente poste in usica da Orlando Lasso, maestro di cappella del serenissimo Signor Duca di Baviera, et con un mottetto nel fine a sette voci | Adam Berg | Munich | Italian | 553117 | 2o |

| 1595 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo con le lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone… aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria del Signor Orazio Guarguante da Soncino. | [Giovan Battista Porta] | Venice | Italian | 858059 | 8o |

| 1596 | Sabie | Francis | Adams complaint. The olde worldes tragedie. David and Bathsheba. | Richard Johnes | London | English | 21534 | 4o |

| 1596 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de Sainct Pierre imitées du Tansille au roy | Lucas Breyer | Paris | French | 21133 | 8o |

| 1597 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaynt With other poems | James Roberts for Gabriel Cawood | London | English | 22958 | 4o |

| 1597 | Anonymous | Saint Peters Ten Teares | William Jones | London | English | 19797 | 4o | |

| 1597 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le pietose lagrime che fece s. Pietro doppo d’haver negato il suo Signore | Giovanni Battista Maringo | Palermo | Italian | 858060 | 12o |

| 1598 | Broxup | William | Saint Peters path to the joyes of heaven | Felix Kingston | London | English | 3921 | 4o |

| 1598 | Rowlands | Samuel | The betraying of Christ | Adam Istip | London | English | 21365 | 4o |

| 1598 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de S. Pierre, Imitees Dv Tansille. Av Roy. Plus y avons adiousté l’Hymne de la Conscience. | Raphaël du Petit Val | Paris | French | 73737 | 8o |

| 1598 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo con le lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncio | Gio. Battista Bonfadino | Venice | Italian | 858061 | 8o |

| 1598 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de Sainct Pierre: Dv Seignevr Loys Tansille, Italien. Avec L’Imitation de Malerbe. Av Roy. | ? | Paris | Italian and French | 16868 | 12o |

| 1598 | Gálvez de Montalvo | Luis | Lágrimas de San Pedro (in Primera parte del thesoro de divina poesia donde se contienen varias obras de devoción de diversos autores) | Jorge Rodrígues a costa de Pedro Flores | Lisbon | Spanish | 340675 | 8o |

| 1599 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint With other poems | James Roberts for Gabriel Cawood | London | English | 22959 | 4o |

| 1599 | Malherbe | François de | Les Larmes de S. Pierre, Imitées Dv Tansille. Av Roy. Plus y avons adiousté l’Hymne de la Conscience. | Raphaël du Petit Val | Paris | French | 21922 | 8o |

| 1599 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo con le lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncio | Agostino Spineda | Venice | Italian | 858062 | 8o |

| 1600 | Markham | Gervase | The teares of the beloved: or, The lamentation of Saint John | Simon Stafford | London | English | 17395 | 4o |

| 1600 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint With other poems | Robert Waldegrave | Edinburgh | English | 22960 | 4o |

| 1600 | Nervèze | Antoine de | Les larmes et martyre de s. Pierre avec ses meditations tres devotes | Maurice Malicieux [=Benoît Rigaud] | Chambéry [=Lyon] | French | 80267 | 16o |

| 1601 | Anonymous | The Song of Mary the Mother of Christ and The teares of Christ in the garden | William Ferbrand | London | English | 17547 | 4o | |

| 1601 | Breton | Nicholas | A divine poeme divided into two partes: the ravisht soule, and the blessed weeper | John Browne | London | English | 3648 | 4o |

| 1601 | Markham | Gervase | Marie Magdalens Lamentations | Adam Islip for Edward White | London | English | 17569 | 4o |

| 1601 | Verstegan | Richard | Odes in imitation of the seaven penitential psalmes | A. Conincx | Antwerp | English | 21359 | 4o |

| 1602 | Evans | William | Pietatis lachrymae. Teares of devotion | Edward Allde | London | English | 10597.5 | 4o |

| 1602 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint Newlie augmented with other poems | I. Roberts for G. Cawood | London | English | 22960a | 4o |

| 1602 | Anonymous | Saint Peters Teares | William Jones | London | English | 19798 | 4o | |

| 1602 | Ávalos y Figueroa | Diego de | Coloquio XLIII, “en que continuando el comenzado intento y amorosos trances, interponen las Lagrimas de Sant Pedro, traducidas del Tansillo” (in Miscelánea Austral) | Antonio Ricardo | Lima | Spanish | 5043250 | 4o |

| 1602 | de Valagre | Sieur | Les Cantiques | Raphaël du Petit Val | Rouen | French | 6811927 | 12o |

| 1603 | Nervèze | Antoine de | Les larmes et martyre de s. Pierre | Thibaud Ancelin | Lyon | French | 6900326 | 12o |

| 1603 | Despotot | N. | Les larmes de la pénitence, tirées de Jérémie et saint Paul | Arnaud Du Breil | Bordeaux | French | 6800102 | 4o |

| 1603 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo et quelle della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria, del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino. | Nicolò Tebaldini | Venice | Italian | 4030344 | 8o |

| 1604 | Gálvez de Montalvo | Luis | Lágrimas de San Pedro (in Primera Parte del thesoro de divina poesia, donde se contienen varias obras de devocion de diversos autores cuyos titulos se veran a la vuelta de la hoja) | s.n. | Seville | Spanish | 5003160 | 8o |

| 1605 | Ellis | G. | The lamentation of the lost sheepe | W. Jaggard | London | English | 7606 | 4o |

| 1605 | De La Boissonade | Les larmes du vray pénitent Saint Pierre | Jean de Heuqueville | Paris | French | 6015786 | 16o | |

| 1605 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo et quelle della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria, del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino. | Heredi di Domenico Farri | Venice | Italian | 4032769 | 8o |

| 1606 | Nostredame | César de | Les perles que les larmes de la Saincte Magdeleine avec quelques rymes sainctes dediees a Madame la Comtesse de Carces | Colomiez | Toulouse | French | 6810728 | 12o |

| 1606 | — | — | Larmes de la Vierge sur la passion de nostre Seigneur | Jean Osmont | Rouen | French | 6812750 | 4o |

| 1606 | Estienne | Robert | Les larmes de Saint Pierre et autres vers sur la Passion. Plus quelques paraphrases sur les hymnes de l’année. | Robert Estienne | Paris | French | 6026312 | 8o |

| 1606 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di San pietro del sig. Luigi Tansillo cavate dal suo proprio originale. Poema sacro et heroico in cui si narrano i lamenti, i dolori, i digiuni et le astinenze di Pietro, il quale ci è figura di un vero e divoto Penitente. Con gli Argomenti et Allegorie della Signora Lucretia Marinella et con un discorso nel fine del Sig. Tommaso Costo, nel quale si mostra quanto questo poema stia meglio di quello, che infino ad ora s’è veduto stampato, et esservi di più presso a quattrocento bellissime stanze. | Barezzo Barezzi | Venice | Italian | 4036542 | 8o |

| 1607 | Mesa | Cristóbal de | Valle de lágrimas y diversas rimas | Juan de la Cuesta | Madrid | Spanish | 5006697 | 8o |

| 1608 | Nervèze | Antoine de | Les Ouvres chrestiennes [Les Larmes et martyre de Sainct Pierre.L’exercise de l’âme chrestienne] | Thibaud Ancelin | Lyon | French | 6900969 | 12o |

| 1609 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint newly augmented with other poems | Humphrey Lownes for William Leake | London | English | 22961 | 4o |

| 1609 | — | — | Les larmes et souspirs de saincte Marie Magdalene | Robert Fouet | Paris | French | 6016567 | ? |

| 1609 | — | — | Les Larmes de la glorieuse Vierge Marie sur la mort et passion de son fils | Julien Thoreau | Potiers | French | 6805780 | 12o |

| 1609 | Fernández de Ribera | Rodrigo | Lágrimas de s. Pedro | Alonso Rodríguez Gamarra | Seville | Spanish | 5006260 | 8o |

| 1611 | Lanyer | Aemilia | Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum | Richard Bonian | London | English | 15227 | 4o |

| 1611 | — | — | Exposition des sept Pseaumes pénitentiels. Les Larmes de S. Pierre et autres vers sur la passion; plus, quelques paraphrases sur les hymnes de l’année. | Robert Sara | Paris | French | 6025366 | 12o |

| 1611 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo con le lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria, del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino. | Giorgio Bizzardo | Venice | Italian | 4025433 | 8o |

| 1613 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo con le lagrime della Maddalena del Signor Erasmo da Valvasone, di nuovo ristampate, et aggiuntovi l’eccellenze della Gloriosa Vergine Maria, del Signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino. | Lucio Spineda | Venice | Italian | 4027356 | 8o |

| 1613 | Tansillo | Luigi | Lágrimas de san Pedro compuestas en italiano por Luys Tansillo. Traducidas en español por el maestro fray Damian Aluarez de la orden de predicatores de la provincia de España. | Giovanni Domenico Roncagliolo | Naples | Spanish | 4022172 | ? |

| 1613 | Álvarez | Damián | Lágrimas de san Pedro | Giovanni Domenico Roncaglioli | Naples | Spanish | 5018800 | 12o |

| 1613 | de Valagre | Sieur | Les cantiques du Sieur de Valagre et les cantiques du Sieur de Maizon-fleur…En cette dernière edition ont esté adioustees les larmes de Jesus Christ… et autres œuvres Chrestiennes | Raphaël du Petit Val | Rouen | French | 6813068 | 12o |

| 1615 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint newly augmented with other poems | W. Stansby for William Barret | London | English | 22962 | 4o |

| 1615 | Méndez Quintella | Diego | Conversam e lagrimas da gloriosa sancta Maria Magdalena, et outras obras espirituales | Vicente Álvarez | Lisbon | Portuguese | 5016869 | 12o |

| 1616 | Southwell | Robert | S. Peters complaint. And Saint Mary Magdalens funerall teares. | English College Press | Saint-Omer | English | 22963 | 8o |

| 1618 | Tansillo | Luigi | Le lagrime di San Pietro. Aggiuntevi l’eccellenze della gloriosa Vergina Maria, del signor Horatio Guarguante da Soncino | Lucio Spineda | Venice | Italian | 4022122 | 8o |

| 1620 | Southwell | Robert | S. Peters complaint, and Saint Mary Magdalens funerall teares | English College Press | St. Omer | English | 22964 | 8o |

| 1620 | Southwell | Robert | St Peters complainte Mary Magdal. teares | W. Barrett | London | English | 22965 | 12o |

| 1621 | García | Lerín | Las lágrimas de Hieremias sobra la ruyna de Hierusalem | Adrian Tiffaine | Paris | Spanish | 5033321 | 8o |

| 1625 | Le Comte | Pierre | Les larmes de la Mère de Dieu ou Deux paraphrases sur le Stabat Mater dolorsa | Jean Bessin | Paris | French | 6002629 | ? |

| 1630 | Southwell | Robert | St Peters complainte Mary Magdal. teares | I. Haviland | London | English | 22966 | 12o |

| 1632 | Bouglers | Pierre de | Les larmes de la Madeleine ou le miroir de penitence | Jean de Spira | Douai | French | 1118644 | 12o |

| 1634 | Southwell | Robert | Saint Peters complaint | John Wreittoun | Edinburgh | English | 22967 | 4o |

| 1636 | Southwell | Robert | St Peters complainte Mary Magdal. teares | I. Haviland | London | English | 22968 | 12o |

Notes

| 1 | Lamentations 1: 1 (NIV). |

| 2 | For an expanded discussion on Abelard’s planctus cycle, see (Dronke 1970, pp. 14–49). |

| 3 | Woolf (1986) makes a similar point regarding Old English medieval planctus poems, noting that the cultural context where works were read aloud strongly suggests that such poets had their audiences in mind as recipients (p. 158). |

| 4 | Though Hay (2002) has argued that there was no significant following of the devotio moderna in Italy, save for the mid-fifteenth-century Venetian circles of Ludovico Barbo and Lorenzo Gustiniani (pp. 97–98), Mazzonis (2007) has highlighted that its emphasis on individual affect, interiority, and Christocentrism strongly resembles devotional practices in the mid-fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries (pp. 153–56). |

| 5 | Examples of this approach include the excellent work of (Prosperi 1996) and (de Boer 2001) on the broad expansion of Confession in the period as a sacrament that could be used to maintain social order. |

| 6 | González Miguel (1979) provides a helpful overview of each of the three Italian versions of the poem as follows: the one in 42 octaves (pp. 227–29); Attendolo’s edition in 13 pianti (pp. 230–32); and Costo’s 1606 edition in 15 canti (pp. 232–37). |

| 7 | Flamini (1893) counts 22 editions of the poem published in Italian between 1560 and 1847 (Flamini 1893, CXLI-CXLIX). |

| 8 | On the profound influence of Tansillo in the period, see (Cox 2011, pp. 37–38). |

| 9 | Sannazaro’s influence on weeping poetry has also been suggested by Terence Cave, who highlights the popularity of his 1526 De morte Christi Domini ad Mortales Lamentatio published with the De partu, and the influence of Guy de Le Fèvre de la Boderie’s 1576 French translation on the French tradition of weeping poetry. Further evidence for Sannazaro’s influence on weeping poetry in France is evidenced by the potential manuscript circulation of the lamentatio during the poet’s time in Paris (1503–1504) and by the early publication of the Latin poem in a collection printed by Josse Badius Ascencius in 1513 (Cave 1969, p. 249; Opuscula pia et docta septem 1513). On the early French circulation of the Lamentatio see (Deramaix 2006, p. 371). |

| 10 | Much of Tansillo’s literary career is as a lyric poet. Although he never published a Canzoniere, Milburn notes that he authored a great deal of lyric poetry that circulated in pirated editions and in both manuscript and printed miscellanies, often without the author’s knowledge or consent. See (Milburn 2003, pp. 13–15). On the experimental nature of Aretino’s Sette salmi conceived by the author as part of a ‘sacred trilogy’ combining both secular and religious material, see (Boillet 2007). |

| 11 | As Attendolo was one of the defenders of the superiority of Tasso above Ariosto, the letter is included in the 1588 collection of writings on the literary debate entitled Lo ’Nfarinato secondo ovvero dello ’Nfarinato Accademico della Crusca, risposta al libro intitolato Replica di Camillo Pellegrino (Lo ‘Nfarinato secondo 1588). All translations are ours unless otherwise indicated. |

| 12 | Confusion seems to exist around this collection with some authors claiming that two such anthologies were published (Spear 1997, p. 174). While a separate entry for Raccolta di lagrime cioè di Maria Maddalena. Di Maria Vergine. Del penitente exists in the USTC (#806834), EDIT 16 has deleted the CNCE record number 60380, noting that it is part of the aforementioned collection (CNCE 38317; USTC 806825). |

| 13 | Sieur de Valagre, Les cantiques du Sieur de Valagre et les cantiques du Sieur de Maizon-fleur… En cette dernière edition ont esté adioustees les Larmes de Jesus Christ… et autres œuvres Chrestiennes (Rouen: Raphaël du Petit Val, 1602). On this collection, and weeping poetry in Early Modern France more broadly, see (Cave 1969, pp. 249–66). |

| 14 | Johnson also notes that Tansillo’s poem was also imitated by other writers in the period, including Luis Gálvez de Montalvo (Toledo, 1587), Fray Damián Álvarez (Naples, 1613), and Rodrigo Fernández de Ribera (Seville, 1609), p. 497 fn.6. |

| 15 | For an argument against reading the relationship between Wyatt and Aretino as a straightforwardly Protestant reworking of a straightforwardly Catholic work, see (Rossiter 2015, pp. 595–614). For the argument that Wyatt’s publishers timed the printed edition of the Penitential Psalms as Protestant polemic, see (Costley-King’oo 2011, pp. 155–74). |

| 16 | Two immediate examples include several of the poems mentioned by González Miguel (1979) such as the Lágrimas de San Pedro by Jerónimo de los Cobos, which remained in manuscript until 1890, or the translation by Gregorio Hernández de Velasco—who also translated Sannazaro’s De Partu and Virgil’s Aeneid into Spanish—which remained in manuscript until 1957. |

| 17 | The most likely date of composition is between 1598, when Elizabeth gave Speed a political appointment (his dedication mentions her “graces” to him) and her death in 1603. |

References

- Boillet, Elise. 2007. L’Arétin et la Bible. Geneva: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, Peter, and Lino Pertile, eds. 2004. The Cambridge History of Italian Literature. First revised edition. repr. New York: Cambridge University Press. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Broxup, William. 1598. Saint Peters Path to the Joyes of Heaven. London: Felix Kingston. [Google Scholar]

- Cave, Terence. 1969. Devotional Poetry in France. New York and London: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costley-King’oo, Clare. 2011. Rightful Penitence and the Publication of Wyatt’s Certayne Psalmes. In Psalms in the Early Modern World. Edited by Linda Austern, Kari McBride and David Orvis. Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 155–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Virginia. 2011. The Prodigious Muse: Women’s Writing in Counter-Reformation Italy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, Wietse. 2001. The Conquest of the Soul: Confessions, Discipline, and Public Order in Counter-Reformation Milan. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Deramaix, Marc. 2006. Le Fèvre de la Boderie premier traducteur de Sannazar. In Italie et la France dans l’Europe latine du XIVe au XVIIe siècle: Influence, Émulation, Traduction. Edited by Marc Deramaix and Ginette Vagenheim. Rouen: Publications des Universités de Rouen et du Havre. [Google Scholar]

- Dronke, Peter. 2002. The Medieval Lyric, 3rd ed. Woodridge: Boydell and Brewer. First published 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dronke, Peter. 1970. Poetic Individuality in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Robert R. 1999. The Desolate Palace and the Solitary City: Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Dante. Studies in Philology 96: 394–416. Available online: ww.jstor.org/stable/4174651 (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- Flamini, Francesco. 1893. Luigi Tansillo, Egloga e i Poemetti. Trani: Naples. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles Roldán, Aurora. 2009. La poética del llanto en sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Zaragoza: Prensas Universitarias de Zaragosa. [Google Scholar]

- González Miguel, Jesús Graciláno. 1979. Presencia Napolitana en el Siglo de oro Español: Luigi Tansillo (1510–1568). Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin, Hannibal. 2004. Psalm Culture and Early Modern English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Denys. 2002. The Church in Italy in the Fifteenth Century: The Birkbeck Lectures 1971. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, Elizabeth. 2015. Grief and Women Writers in the English Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Imorde, Joseph. 2013. Tasting God: The Sweetness of Crying in the Counter-Reformation. In Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Wietse De Boer and Christine Göttler. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 257–69. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Paul Michael. 2017. The End(lessnes)s of Infamy: Agamben, Enjambment, and Embodiment in a Cervantine Stanza. MLN 132: 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchar, Gary. 2008. The Poetry of Religious Sorrow in Early Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lanyer, Aemilia. 1611. Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum. London: Valentine Simmes for Richard Bonian. [Google Scholar]

- Lewalski, Barbara K. 1998. Seizing Discourses and Reinventing Genres. In Aemilia Lanyer: Gender, Genre, and the Canon. Edited by Marshall Grossman. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lo ‘Nfarinato secondo ovvero dello ‘Nfarinato Accademico della Crusca, risposta al libro intitolato Replica di Camillo Pellegrino. 1588. Florence: Anton Padovani.

- Markham, Gervase. 1601. Marie Magdalens Lamentations for the Losse of Her Master Jesus. London: Adam Islip for Edward White. [Google Scholar]

- Marotti, Arthur F. 2005. Religious Ideology and Cultural Fantasy: Catholic and Anti-Catholic Discourses in Early Modern England. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzonis, Querciolo. 2007. Spirituality, Gender, and the Self in Renaissance Italy: Angela Merici and the Company of St. Urusla (1474–1540). Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milburn, Erika. 2003. Luigi Tansillo and Lyric Poetry in Sixteenth-Century Naples. MHRA Texts and Dissertations. Leeds: Modern Humanities Research Association, vol. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Mutini, Claudio. 1962. Attendolo, Giovanni Battista. Dizionario Biografico Degli Italiani 4. Available online: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovan-battista-attendolo_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Nuova raccolta di lagrime di piu poeti illustri. 1593. Bergamo: Comino Ventura.

- O’Donnell, Simone Laqua. 2013. Catholic Piety and Community. In The Ashgate Research Companion to the Counter-Reformation. Edited by Alexandra Bamji, Geert H. Janssen and Mary Laven. Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 359–80. [Google Scholar]

- Opuscula pia et Docta Septem. 1513. Paris: Josse Badius Ascencius.

- Praz, Mario. 1924. Robert Southwell’s ‘Saint Peter’s Complaint’ and its Italian Source. The Modern Language Review 19: 273–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, Adriano. 1996. Tribunali della Coscienza: Inquisitori, Confessori, Missionari. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Quondam, Amedeo. 2005. Paradigmi e Tradizioni. Rome: Bulzoni. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. 2002. Worrying about Emotions in History. American Historical Review 107: 821–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossiter, William T. 2015. What Wyatt Really Did to Aretino’s Sette Salmi. Renaissance Studies 29: 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shell, Alison. 1999. Catholicism, Controversy and the English Literary Imagination, 1558–1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Southwell, Robert. 1967. The Poems of Robert Southwell, S.J. Edited by James H. McDonald and Nancy Pollard Brown. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, Richard E. 1997. The “Divine” Guido: Religion, Sex, Money, and Art in the World of Guido Reni. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Speed, John. n.d. Davids Harp Tuned Unto Teares. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, Osborn b89.

- Stegner, Paul D. 2016. Confession and Memory in Early Modern English Literature: Penitential Remains. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tansillo, Luigi. 1587. Le Lagrime di San Pietro. Girolamo Bartoli: Genova. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, Tobia. 1987. Note sulla composizione e la pubblicazione de ‘Le Lagrime di San Pietro’ Di Luigi Tansillo. In Rinascimento Meridionale e Altri Studi. Edited by Maria Cristina Cafisse, Francesco D’Espicopo, Vincenzo Dolla, Tonia Fiorino and Lucia Miele. Naples: Società Editrice Napoletana, pp. 437–61. [Google Scholar]

- Verstegan, Richard. 1601. Odes in Imitation of the Seaven Penitential Psalmes. Antwerp: [A. Conincx]. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, Rosemary. 1986. Art and Doctrine: Essays on Medieval Literature. Edited by Heather O’Donoghue. London: Hambledon Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).