Abstract

Lake Qooqa in Oromia/Ethiopia started out as a man-made lake back in the 1960s, formed by the damming of the Awash River and other rivers for a practical function, i.e., for hydroelectric power. The lake flooded over the surrounding picturesque landscape, shattered sacred sites and the livelihoods of the Siiba Oromo, and damaged the ecosystem in the area, which was later resuscitated to have an aesthetic function for tourists. Available sources showed that people used the lake for irrigation, washing, fishing, and drinking, while tanneries, flower farms, and manufacturing facilities for soap and plastic products were set up along the banks without enough environmental impact assessment and virtually with no regulations on how to get rid of their effluents, which contained dangerous chemicals such as arsenic, mercury, chromium, lead, and cadmium, giving the lake a blue and green color locally called bulee; hence, the name the “Green Lake”. In the present study, following a string of “narrative turns” in other disciplinary fields of humanities and social sciences (folklore, history, and anthropology), I use social memory and life hi/story narratives from Amudde, Arsi, Oromia/Ethiopia, to consider a few methodological and theoretical questions of folkloric and ecological nature in doing a narrative study: What is social memory? What does social memory reveal about the people and the environment in which they live? Is a personal narrative story folklore? Where do stories come from? What should the researcher do with the stories s/he collected? Hence, this study aims to tackle two objectives: first, using social memory data as a means to connect social identity and historical memory set in a social context in which people shape their group identity and debate conflicting views of the past, I explore the Green Lake as a narrative, which is, in its current situation, a prototypical image of degradation and anthropogenic impacts, and trace trajectories and meanings of social memory about the shared past, i.e., the historical grief of loss that people in the study area carry in their memory pool. Second, toward this end, I use people’s stories from the research site, particularly Amina’s story about the loss of seven members of her family from complications related to drinking the polluted water, as evidence to show, sharing Sandra Dolby Stahl’s claim, that the narrative of personal experience belongs in folklore studies to the established genre of the family story.

bishaaniifi haati xuurii malee xurii hin qaban.there is nothing dirt about water and mother but guilt (when gone).Oromo proverb. Amudde

1. Introduction

The purpose of the present study is to explore contested social memory narratives about the unsettled human–ecology relationship in Amudde, using “narrative” methods of “temporality”, “sociality”, and “place” (Connelly and Clandinin 1990). People’s narrated life experience directs attention toward the past, present, and future (temporality) of places, events, and things in the area of study (place), which affects the personal and social conditions of the participants understood in terms of cultural, institutional, social, and linguistic narratives. A narrative approach “is closely linked to life history, because it involves telling stories, recounting—accounting for—how individuals make sense of events and actions in their lives with themselves as the agents of their lives” (McAlpine 2016).

In the present study, following a string of “narrative turns” in other fields of folkloric/literary studies, ethnoecology, environmental history, and anthropology, I use “social memory” and “life hi/story narratives” from Amudde, Arsi, Oromia/Ethiopia, to trigger a few rather broad methodological and theoretical questions of a folkloric and ecological nature: What is a social memory narrative? What does a social memory reveal about the people and the environment in which they live? Is a personal narrative story folklore? Where do stories come from? What should the researcher do with the stories s/he collected?

Thus, focusing on the Amudde people’s narrative of the Qooqa Lake and using social memory data from the area, this research project deals with issues of the politics of resources and trajectories of lives and local knowledge/poetics about social–ecological systems in the study area. Among the myriad of other cycles of chaos and renewals in social–ecological systems and problems facing Oromia and its people to date, the political paralysis, economic inequality, and cultural cultural and social injustices, while inseparably interlinked, exacerbated the “wicked problem”, namely, the social–ecological crises (for example, the case of the Qooqa Lake), which largely stems, as will be discussed shortly, from the denial of agency and humanity to the vast poor and resilient struggling segments of the society. While African ruling elites, for the most part, are the major players and surrogates of Western-led environmental and economic policies, this elemental human and ecological dimension has not received sufficient academic attention yet.

By linking the two dimensions of the stated problem, in this project, using the social memory and narrative inquiry method, I gathered evidence from across interdisciplinary fields of ecological humanities, folklore, and social sciences and from the social memory of people in Amudde in January, March, and April 2020 through interviews and observations to determine,

- (a)

- how local institutions, ecological knowledge, and indigenous practices work with the mainstream environmental conservation strategies to enhance cultural resilience and what strategies are socially and culturally acceptable;

- (b)

- what conflicting views and contested narratives are carried in the people’s social memory;

- (c)

- what scientific conservation plans and local water harvesting methods are used; and

- (d)

- what strategies the people use to recount the humanitarian and ecological crisis in the area and to envision the prospect of ethnoecological approach to solve the problem.

1.1. Background

When social capital is weakened, diversity is disregarded, and the local people are not consulted in decision making about their lives and the environment in which they live, governance is dysfunctional and resentment and fierce resistance become obvious (Krasny and Tidball 2015). Currently, the Oromo are in some debate about what constitutes the human good when things fall apart and how to endure life in adverse conditions as the socio-political and ecological crisis is unfolding in Ethiopia.

1.1.1. The Oromo People and Oromia

The Oromo are the most populous single ethno-nation in Northeast Africa, and they constitute the larger portion of the inhabitants of Ethiopia (Central Statistical Agency 2010). They speak Afaan Oromoo (Oromo Language), a Cushitic branch, which is spoken in Ethiopia and Kenya and is the fourth most widely spoken language in Africa after Arabic, Swahili, and Hausa (Lodhi 1993). Until they were colonized by Abyssinia, another African nation, with the help of the European colonial powers of the day, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century (1870–1900), the Oromo developed their own socio-political and cultural system called the Gadaa system, a uniquely democratic institution of paramount human and ecological significance (Luling 1965; Harris 1884; Hassen 1992). To find out how the local ecological knowledge and local institutions address the major challenges of eco-colonialism (Cox and Elmqvist 1997) in Oromia, which has imposed immense human dislocation, environmental degradation, violations of land property rights (land grab) and equity, and compensational injustices, the life histories of the people are a reliable source (Hassen 1992; Jalata 2012; Jackson 2002; Gedicks 1993). The case of the historical forceful eviction of Siiba, the Jiille branch of Tulama Oromo, in the previous Qooqa plain, is no exception. In this study, the life experience narratives of informants and social memory from Amudde, East Arsi, Oromia, and Amina’s story in particular, are to be analyzed from the people’s perspective. In so doing, the end goal of this research, in the long-run, is to seek out ways in the local culture to support the involvement/empowerment of the public through their active participation in community decision making about social–ecological services (sound human–environment relationships) and to work on better cultural ecology practices in the face of rapid socio-economic changes and ecological dynamism (Sheridan 2008).

1.1.2. The Research Setting

The environmental resources in Finfinne, the capital (Addis Ababa), and in its localities are threatened by severe pollution due to population growth, unplanned urbanization and less or no attention given to developing an ecocity, inconsiderate human (anthropogenic) activities, and incongruous industrial effluents and dry wastes that contaminate river waters (Qabbana River, the two Aqaqi Rivers, and Mojo River, among other tributaries of Hawas River) and lakes (Qooqa Lake and others) southeast of the capital (Kottak 1999). Since its foundation in 1887 by removing the Oromo natives of Galan, Yekka, and Gullalle of the Torban Oboo lineages, Finfinne (Addis Ababa) has grown from sparse settlements to an expansive and highly populated city to date, causing waterbodies and ecosystems southeast of its vicinity to suffer immeasurable crises. Its recent unplanned urban development and industrialization has caused considerable internal displacements and environmental degradation and, consequently, the encroachment has been met by furious protests over the last few years.

Lake Qooqa

The Aqaqi–Qooqa wetlands (Figure 1) are part of the Awash River catchment, about 30 miles southeast of Finfinne/Addis Ababa, the capital. The Qooqa reservoir catchment area is 1495 km², and originally it had an area of 12,068 km², but the catchment has suffered much erosion resulting in sediments in the reservoir (Ferezer Eshetu 2012). The fringe of the marsh has some tall sedge, grasses, and reeds, while the rest of the area is a farmland and grassland with a few scattered trees, mostly figs (Degefu et al. 2011a, 2011b). Studies show that the Qooqa Reservoir and other shallow water bodies are “of high ecological and socioeconomic importance”, and this importance has been “compromised by nutrient enrichment that resulted in turbid, algae-dominated waters associated with animal communities… the changes to aqua-system that lead to loss of biodiversity and pose a serious threat to public health” (Yeshiemebet 2016, citing Perrow et al. 1999).

Figure 1.

Qooqa Lake, southeast of Finfinne. Courtesy of Geoview.info.

The Mojo River is another tributary of the Awash River with its own two tributaries, the Wadecha and Balbala. The river is also vital for numerous bird species. Birdlife International identified the Aqaaqi–Qooqa wetlands as a crucial staging ground for winter migratory bird species. According to laboratory analyses of toxic industrial chemicals in the river waters, and by available clinical data from people in the watershed, there is evidence that the Mojo River is one of the two most polluted rivers in Ethiopia. The rivers feed into the Qooqa Lake with their contamitants and wastes out of Finfinne, the capital.

The Pollution Problem

Ethiopia is considered the water tower of east Africa because of its great resource of surface and groundwater. However, in spite of its available water, the country is unable to provide access to clean water in either rural or urban areas. With the growth of unplanned urbanization and industrialization in the capital, Finfinee (Addis Ababa), humanity faces many “wicked problems”. Rural water pollution is one grave danger that necessitates a long-lasting solution and action. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 3.58 million people die every year from water-related diseases. In the Oromia Region, the under age five mortality rate is 193 per 1000.

In central Oromia, around the Qooqa Lake, Mojo River, and the Aqaqi River, pollution has been putting tremendous pressure on both social and natural capital. This includes solid and liquid wastes recklessly dumped in the rivers and streams. Solid wastes are not recycled. Studies show that the practice of recycling solid wastes such as composting and biomass is at its experimental stage in the country (Ademe and Alemayehu 2014). The liquid waste management is also at its rudimental stage, and there is no binding rule implemented for industries regarding how to dispose of their wastes without affecting the environment and the society (Yeshiemebet 2016).

According to available data, the crucial environmental problems within and around the capital are caused by human (anthropogenic) factors and poor industrial waste disposals, which include the following: car washing, garages, petrol stations, chemical factories, paint factories, tanneries, slaughterhouses, market centers, breweries, textile factories, hospitals, tire factories, thread and garment factories, oil mills, flour mills, steel factories, tobacco factories, and pharmaceutical factories. Furthermore, most houses (residential or business) have no connection to the municipal sewer line; the majority of industries are located in the capital, industries are established close to rivers and discharge wastes into the waterways, and the people have no awareness of sustainable waste management or education about waste reduction, recycling, composting, or energy generation. The majority of industries were planted without practical environmental enforcement before delivery of the land.

The major wastewaters that drain industrial disposals into the Qooqa reservoir include the Aqaqi River (great and little Aqaqi), the tributary of Awash River, Mojo River, which in turn takes the raw effluent directly from the Mojo mill factory and from the butter houses and poultry farms, and the Shoa and Ethio-tanneries, which discharge their effluent into Lake Qooqa (Yeshiemebet 2016; Fasil Degefu et al. 2013). Social memory narratives and personal experience stories about the social–ecological crisis caused by industrial wastes discharged into the rivers and lakes, particularly the Qooqa Lake, will be collected to determine the people’s resilient reintegration process (Norris et al. 2008).

1.2. Purpose

Research into the meanings of social memory and narratives that come from folkloric and ecocultural data about Lake Qooqa and other humanitarian and ecological crises in the area is thin on the ground. By applying folkloric, historical, and ethnoecological methods, the present study is hoped to have the potential to advance the frontier of knowledge in the field of social memory research by introducing interdisciplinary approaches to the “wicked problem”, namely, a recurring ecological crisis in Amudde, and in so doing, it lays a fertile ground for further research into indigenous practices used to balance human and ecological solidarity at risk. As part of the impact activities, in collaboration with local institutions, custodians, and environmental education workers, a narrative-based ecological study can engage individuals and families in awareness raising tasks and empower the community to become more resilient and restore healthy ecosystems (Mowo et al. 2011). Witnessing the interdisciplinary understanding of “oral history”, Della Pollock (2005) writes in Remembering, “the performance of oral history is itself a transformational process. At the very least, it translates subjectively remembered events into embodied memory acts, moving memory into re-membering” (p. 2). Thus, the lasting impact of the present study is hoped to be that local institutional custodians and environmental (education) agents will work jointly and act together to challenge the top-down policies that violate human rights to live in a safe environment and disregard the local institutions and community’s role in decision-making processes from the ground up (Ruíz-Mallén et al. 2012).

1.3. Objectives

Using the social memory and narrative inquiry method, the objective of this interdisciplinary research is to explore the politics of resources in the study area, to identify strategies used to recount the historical humanitarian and environmental crisis, to consider the parameters and limits of the cultural resilience of the people, and, in so doing, to envision a reconstructive and transformative outlook on social–ecological issues in Amudde. Thus, the basic assumption here is that the social memory narrative is informative about the historical grief of loss and the local ethnoecological knowledge that are understudied in Amudde and its surroundings, and it plays a significant role in sustaining indigenous social–ecological practices and informing policies.

Toward that end, the present study looks forward to a youth- and women-focused social–ecological skill learning (eco-literacy) based on the local ecological practices and environmental education to maintain a healthy human–nature nexus and to enhance ecocultural resilience (Rappaport 1971). I collected relevant data through interviews and observation in Amudde to analyze using cultural, folkloric, and historical trend analyses. Examining closely the belief system of the people was helpful to find out the underlying values of the culture, uncertainties, fears, ambitions, taboos, and morals that constitute an ethical human–nature nexus. Studies show that the performances of rituals, personal life histories, festivals, and coronation of sacred trees/sites have considerable effects on environmental attitudes and can play a major role in revitalizing the ecological practices changed over time (Gumo et al. 2012; Ingold 2003).

1.4. Rationale

My interest in the present research and collecting available relevant documents about the Qooqa-Lake-related human and environmental crisis in Amudde started five years ago, when I was attending “Civic Ecology” courses at Cornell University, NY, after my PhD in Folklore and Anthropology from Indiana University, Bloomington, USA. It was at that time that I encountered the Al Jazeera BBC Documentary titled “People and Power/The Price of Development”, based on Amina’s narrative from Amudde, Arsi, about the tragic death of seven members of her family due to the Qooqa Lake water-pollution-related complications. Two major reasons make the current study compelling: first, the magnitude of human and environmental damages that people in the study area have suffered over the last sixty years, and second, the lack of studies conducted with significant paid attention to the problem from the people’s perspective using the social memory method and the people’s life experience narratives by focusing on indigenous ecological practices in the area.

1.5. Organization of the Study

This paper is organized into five sections. The first section deals with the objectives, purpose, and background of the study and a brief history of the Oromo people. In the second section, a review of literature on the social memory and narrative method and religious and socio-cultural pressures that led to the erosion of local knowledge and contamination of the lake is presented. Section three discusses discourses on the social memory method, followed by section four, where I interpretatively explore empirical examples of social memory narratives built around Lake Qooqa: its use, perceptions about the use, i.e., subjective perceptions of the reality (reality as witnessed) and their objective representations (reality as objectively practiced and described), and implications of the use as recounted by the people in Amudde (reflexivity) through interviews, group discussions, and observations of reality as agreed upon (intersubjective dimension). Social memory, personal stories, and their narrative repertoires are reconstructed, analyzed, and relocated by means of the contextualization of the stories within the broader meta-narrative of Oromo (macro-)history. Section five concludes that beyond the knowledge to be obtained from a modest contribution made by the present research into meanings of social memory, from related future research into ecological crisis and indigenous practices from the people’s perspective/s, it is hoped, some societally important and positive outcomes can be anticipated.

2. Theorizing the Social Memory Narrative

In the present project, it is not my plan to provide a definitive account of advances into narrative inquiry. Rather, I shall trace some of those terrains in the inquiry landscape along which the “social memory narrative” method has moved, focusing on those trajectories that have cut across the field of folklore (and narrative) research. Thus, for this purpose, I shall take up issues specific to the ecological crisis with specific reference to Lake Qooqa and its surroundings to address the uses and purposes of narrative inquiry in ethnoecology. Thus, some of the theoretical and methodological questions to consider here include: What is a social memory narrative? What does the story reveal about the people and the environment in which they live? Is a personal narrative story folklore? Where do stories come from? What should the narrative researcher do with the stories s/he collected?

2.1. Some Conceptual Considerations

Building on the research of other scholars, next, I emphasize the importance of understanding social memory as contextually and culturally based and capturing what people mean when (or even why) they say “nan yaadadha”, that is, “I remember”, or “nan hirraanfadhe”, which means “I forgot”. The purpose of this research is, using a folkloric “social memory” and “narrative inquiry” approach, to explore the uncharted terrain of Qooqa Lake, one of the “water bodies in the Oromian/Ethiopian Rift Valley subjected to escalating environmental degradation due to the increasing industrial and agricultural activities” (Yeshiemebet 2016). What is narrative? For the purpose of the present study, by “narrative” I mean, sharing Margaret S. Barrett’s view (Barrett and Stauffer 2006), a “mode of knowing” and “constructing meaning”, a “method of inquiry”, or a “story, an account to self and others of people, places, and events, and the relationships that hold between these elements …the capacity to speak, and through that medium, to construct a version of events” (pp. 6–7).

2.1.1. Discourses on Social Memory

What is social memory? Social memory as a concept is used to explore the connection between social identity and historical memory, and seeks to answer the reason why members of a social group think they belong to the group and share a common past. To put emphasis on the internalization of “group identity”, some scholars use “collective” memory, while some prefer “social” memory to pay attention to a “social context” in which people shape their group identities and decide to agree, disagree, or negotiate their conflicting views of the past and search for common memories to meet present needs. To Fentress and Wickham (1992), “memory is a complex process, not a simple mental act”, and it is used to describe various acts, such as to recognize, to remember, to recall, to recount, and to commemorate, which shows that “‘memory’ can include anything from a highly private and spontaneous, possibly wordless, mental sensation to a formalized public ceremony” (x). It is “individuals who do the remembering”; so, what is “social” about this individual act, i.e., “memory”? Fentress and Wickham rightly argue that “the essential answer is that much memory is attached to membership of social groups of one kind or another” (ibid). From a folkloric perspective, Ben-Amos and Weissberg (1999) succinctly state that “cultural memory” is the creative invention of the past to serve/critique the present and to envision the future, and they explore the dynamics of “cultural memory” on the level of everyday life contexts and show how memory is shaped and how it operates in uniting society on some common ground.

Of the relationship between “collective memory” and “historical memory”, Maria Todorova writes, the former “represents lived experience, and the second is concerned with the preservation of lived experience, i.e., ‘between one’s sense of having an experience, and an external representation of that experience’” (Todorova 2004, p. 4). Hence, as Bernbeck et al. (2017) convincingly argue, “anything in and from the past can be studied as part of a process that relates past and present—a diachronic relationship”, and sharing Halbwachs’s view they add that “memory” and “history” are distinct as “in the realm of memory the present is the dominant side, while historical disciplines give the past the primary place” (Bernbeck et al. 2017, p. 13). To stress this temporal dimension of memory against history, Bernbeck claims, “we have set memory apart from history because of its firm placement in the present” (Bernbeck et al. 2017, p. 24).

What is forgetting? If memories express the connectedness of minds to bodies and bodies to the social and natural world around them, then this connectedness and “continuity is also the source of normal forgetfulness as well” (Fentress and Wickham 1992, ibid. 39). The act of forgetting can be explained simply by “how a story, in passing from generation to generation, is successively altered”, particularly in oral societies, to describe the oral transmission of expressive cultures, as there is “no basis for comparison” of the version told by the storyteller as the version learned many years ago (Fentress and Wickham 1992, ibid. 40). The transmission of memory poses a problem regarding the distinction between “remembrance of the common past as made available through conversation, narration, songs, gestures (religious, cult, dance), pictures, emotions and empathy (performance), and of specific accounts of the past told by memory specialist who address a specific privileged audience” (p. 34). Plato claims (in his seventh letter) that “writing weakens the individual memory”; likewise, Ulrike Sommer (2017) maintains, “memory specialists preserved epic cycles, religious lore and genealogy, such as the Greek and Irish bards, or the Griots in Western Africa” (p. 34). Even though there can be “a tendency to overrate the time-span that shared memory can survive”, and chances for forgetting over a long period of time, there are longer oral transmissions claimed among oral cultures, as among the Borana Oromo (Oba-Smidt 2016), reaching back several years, “which is impossible to prove and rather unlikely” (Sommer 2017, p. 34). Despite the time limit to remembering past events, among the different types of knowledge about the past include “personal memory, which has a very limited temporal reach; and intergenerationally transmitted narratives and histories” (Sommer 2017, p. 37).

What is “narrative inquiry”? In this study, narrative inquiry is understood as an interpretive approach that involves a storytelling method. Thus, the story becomes an object of study about how the individual (or group) makes sense of events and actions in their lives set in place and time. The study aims to explore the potential of narrative inquiry as a research tool in ethnoecology (folklore-orianted ecology) to enhance the understanding of how stories convey local knowledge about the unbalanced human–nature nexus (Lee and Newfont 2017), and how narratives enable sense-making and identity construction.

What should the narrative researcher do with the stories s/he collected? Ethnographically speaking, “the first-person accounts are realistic descriptions of events” set in time, and thus “it is the events described and not the stories created that are the object of investigation”, whereas, in using narrative inquiry as a multidisciplinary research tool, “narrative analysis then takes the story itself as the object of study” (Mitchell and Egudo 2003, p. 2). In this regard, in doing a narrative study, the bewilderment about “interpretation” and “analysis” is not simple to disregard. Some might consider “analysis” to imply objectivity, and “interpretation” to imply subjectivity, whereas “both work in tandem because we analyze narrative data in order to develop an understanding of the meanings our participants give to themselves” (Kim 2016, p. 189). That is, through analysis of thematic structure and of social and cultural referents, narrative researchers interpret meanings, which “are to be analyzed and interpreted concurrently in a transitional period to the research text” (ibid. 2016, p. 190). To Ruthellen Josselson, “narrative research is always interpretive at every stage … from conceptualization of research, to data collection, to writing research text” (Josselson 2006, p. 4).

Is a personal narrative story folklore? The multifaceted narrative form is another challenge to a narrative researcher. One can connect “social memory” and “narrative” in Margarete Sandelowski (1991) note quoting Roland Barthes: “‘Narratives assume many forms. They are heard, seen and read; they are told, performed, painted, sculpted and written. They are international, trans-historical and transcultural: ‘simply there, like life itself’” (Sandelowski 1991, p. 162). In a non-folkloric context, Sandelowski considers spoken narratives as emphasizing (a) textual matters, that is, the syntactic and semantic devices connecting parts of the text; (b) ideational matters, the referential meaning of what is said; and (c) interpersonal matters, or the role of relationships between teller and listener as reflected in speech (Sandelowski 1991, p. 163).

Elliott Oring (1986), an American folklorist, shares the view that “narrative is another word for story, and narrating is a method by which an experience is transformed into a verbal account”, recapitulating an experience and “matching a verbal sequence of statements to some sequence of events which is purported to have occurred” (ibid). “Among some sub-varieties of “narrative” are: origin myth, Saint’s legend, memorate, fabulat, novella, aetiological tale, magic tale, joke, jest, animal tale, catch tale, clock tale, formula tale, personal experience story, and life history (emphasis mine), just to name a few” (Oring 1986, p. 121). To Oring, “personal experience story” and “life history” make a sub-variety of a spoken “narrative”, and whether those are folklore is left to us to bet.

However, from what Oring claims, what makes a “narrative” a “folk narrative” depends on our conceptualization of what “folklore” is. That is to say, to Elliott Oring, “folk narratives are generally conceptualized to be those narratives which articulate primarily in oral tradition and are communicated face-to-face” (pp. 122–23). Thus, from what has been stated, it is to be understood that “oral tradition” as a “culture bearer”, “language” as a “medium”, and a “face-to-face communication” as a “social context” are among other characteristic features that a “personal experience story” and a “life history” have to share with a “folk narrative”, since the two modes of communication (a “personal experience story” and a “life history”) exhibit “oral” rather than “written” channels. However, I should add here that some characteristics of “folk narratives” include the following: folk narratives must be re-created with each telling; with this recreation processes, they reflect, like social memory, the past (language, symbols, events, and forms) to evoke meaning at present about contemporary situations, concerns, values, and attitudes; renovation, that is, the past is made to speak the present, reflecting both the individual and the community; the narrator re-creates in accordance with his/her own disposition and circumstances (Oring 1986, ibid., p. 123).

This is an attempt to theorize social memory narrative data analysis and interpretation, which involves the broad concepts of stories, narratives, and storytelling using “stories as an approach to research inquiry; narrative analysis as a way of crystallizing arguments and assumptions; and storytelling as a way of understanding, communicating, and influencing others” (Kim 2016, p. 189). Among the various perspectives of doing narrative research, one can consider descriptive and explanatory methods. According to Margarete Sandelowski (1991), in descriptive narrative research, the focus of the researcher is to describe:

- (a)

- individual and group narratives of life stories or particular life episodes;

- (b)

- the conditions under which one storyline, or emplotment and signification of events, prevails over, coheres with, or conflicts with other storylines;

- (c)

- the relationship between individual stories and the available cultural stock of stories; and

- (d)

- the function that certain life episodes serve in individuals’ emplotment of their lives” (Sandelowski 1991, p. 163).

In this study, narratives are understood as stories, an ordering of events in time and place, “an effort to make something out of those events: to render, or to signify, the experience of persons-in-flux in a personally and culturally coherent, plausible manner … elements of the past, present, and future at a liminal place and fleeting moment in time” (Sandelowski 1991, p. 162). To repeat Sandelowski, narrative analysis is an act of finding a “narrative meaning”, used to “reveal the discontinuities between story and experience and focus on discourse: on the tellings themselves and the devices individuals use to make meaning in stories” (Sandelowski 1991, p. 162).

2.1.2. Revisiting Ethnoecology/Ecotheology

People are connected by their stories about their lived experiences and stand united or divided by their truths. One way to understand a hold that stories and songs can have on us is by examining closely the various ways culture can channel those resentments and express resilience (Dibaba 2018). The stories people tell each other, the song they sing, and prayers they chant reflect and shape their deepest feelings. The question people pose to officials, for example, “if this is your land, where are your stories?”, which came to be the title of Edward Chamberlin’s superb book, is an insight and glimpse into the deep-seated resentment about land and land resources are usurped by the government in the name of common good, bringing a new sense of urgency to find a common ground (Chamberlin 2003). Resentment of ecological injustices knows no borders. The bitter words of the late Ken Saro-Wiwa are about the “deadly ecological war” of eco-colonialism waged by the Anglo/Dutch Shell Oil Company since 1958 against the Ogoni micro-minorities in Nigeria. Like Oromia in Ethiopia, the Ogoniland is a “breadbasket”, a major food producing area; the Rivers State, Nigeria, and the Ogoni are resentful of resource exploitation, as they are victims of an environmental crisis caused by oil spills and blowouts.

The oppressed communities often have to deal with a particular set of vulnerabilities. To help in the search for actual causal mechanisms or resilience processes, it is pertinent to identify vulnerability factors, which include economic, social, environmental, and psychological risks (Vasseur and Jones 2015). The available literature identifies two kinds of risk factors that have a significant effect on the social–ecological resilience of the Oromo around the capital and those in the watershed of the Aqaqi and Mojo Rivers, southeast of the capital: the socio-political risks (adversities), or the historical grief, and the environmental risks, the water contaminants and solid wastes being one typical problem, among others. After the ecological crisis (Hufford 1995), one set of risk factors involves the historical loss or trauma about the unresolved historical grief of loss the Oromo suffer in general. That is, the unresolved historical grief and trauma is the loss that the Oromo communities of Galan, Gullalle, and Ekka suffered and still suffer from the time of the Abyssinian war of conquest (Sahlasillassie, king of Shoa, r.1813–1847; Minilik II, r. 1889–1913) and the Subba of Jille clan near Amudde.

2.2. Oromo Ethnoecology/Ecotheology

Ethnoecology is a human and nature-focused approach to the local ecological knowledge about people’s relationship to their environment (Johnson 2010; Berkes 1999), and ecotheology is a concern about a sanctified relationship between God and humankind, God and nature, and humankind and nature (Kelbessa 2010). Ethnoecologically speaking, to Leslie Main Johnson (2010), land, for example, is not limited to meaning soil or the surface of the Earth. Instead “land” encompasses the totality of beings existing in the place that a people live. It is a homeland, and includes the earth itself and its landforms—the waters, the sky and weather, the living beings, both plant and animal, spirit entities, history, and the will of the Creator. Land in this sense cannot be measured in hectares or reduced to a value of dollars, though the land provides both livelihood and identity. Land constitutes place, rather than space (Casey [1996] 2010, p. 3).

Similarly, from an Oromo perspective, the community “have user and management rights but lack judicial rights to dispose land” (Kelbessa 2010). Among the Oromo, there is a general trend that “human beings originated from this land and returned to it” (Kelbessa 2010, p. 71) (cf. the narrative, Uume Walaabuu baate/Creation began at Walaabu). He adds that the Oromo also “share the view held by many Africans”, and that is, “for Africans, land belongs to all, living and dead. We will live in this land where our fore-parents lived and where our great-great-grand children will live. To make sure that all benefit from this wealth, we have to take care of it properly now. This value system cuts across all ethnic groups in Africa” (Kelbessa 2010).

Unlike Garrett Hardin’s (1968) “tragedy of the commons”, a theory that holds that common property regimes lead to land degradation as each individual user focuses on maximizing their own gain at the expense of that of the community, the African, hence, the Oromo common property management system, and its ecological resilience has various religious and ecological attributes. Workineh Kalbessa, in his Oromo “ecotheology” studies, refutes the governmental and non-governmental claims that peasant farmers in Ethiopia are the major causes of environmental disasters “because of their obvious lack of knowledge about the processes of degradation and about the means used by outsiders to intervene positively”; rather, Workineh rightly argues that the “traditional land tenure system had been one of the major causes of environmental degradation, economic inequality, and exploitation of peasant farmers by the landlords in Ethiopia” (Kelbessa 2010, p. 52).

The African ethnoecological/ecotheological view of traditional environmental conservation includes “taboos”, “totemism”, and “common property” (Mawere 2013, pp. 6–13) to manage the environment and to survive adverse conditions. Thus, the Oromo local knowledge upholds abdaarii (dakkii) or qoolloo (sacred groves/trees) such as “hoomii, qilxuu, hambaabeessa, waddeessa and others which are well protected by some peasant farmers”, and Workineh Kelbessa affirms,

“in autumn, every year, … in most cases women used to sit under qoolloo trees and pray to Waaqa (God) for rain, for protection from sickness and death, famine, snow, drought, and failure of crops, for gifts of longevity, children, prosperity, peace and for protection from evil spirits and wild animals. The Oromo are not worshipping the material symbols, but the spirits of the symbols represented by trees”.(Kelbessa 2010, p. 75)

3. Social Memory Narrative Method

The main sources of the present study are different available relevant documents, interviews with key informants selected by a purposeful sampling method, and community elders and ritual leaders whom I contacted through a snowball technique in the study area and personal observations. I used interdisciplinary approaches such as “narrative trends”/“story-telling”, “ecopoetics”/“ethnoecology”, and “environmental history” vis-à-vis the Oromo worldview, an Oromo “ecotheology” perspective. I have also surveyed relevant studies and publications on social memory narratives and indigenous knowledge and practices.

3.1. Methods and Research Questions

The inquiries below indicate the complementary character of the two knowledge systems, namely, local knowledge and modern science, and the urgent need to promote collaborative projects between researchers and the local population to balance the human–nature relationship.

3.1.1. Research Questions

Using a “social memory narrative inquiry” method, the present study makes an attempt to answer the following questions. In the people’s social memory narrative: what are the major causes of Qooqa Lake water pollution and other related challenges from the people’s perspective? What are the conflicting views and contested narratives in the people’s social memory? What local knowledge is worth attending to in order to eco-culturally and historically alleviate the social–ecological crisis in the people’s lived experience (resilience)? What local institutions are available for decision making and how are they environmentally sound and economically viable to alleviate the crisis locally? Finally, what strategies do the people use to recount the humanitarian and ecological crisis in the area and to envision the prospect of an ethnoecological approach to solving the problem?

3.1.2. Methods

To answer the research questions, I collected primary data from the research area through observation, case-study, and interview tools based on fieldworks in the local ecological culture. There are personal and collective memory narratives used as preliminary evidence to show that, as the poor waste management system in the capital (Addis Ababa) continues, humans and non-humans living in the fringes of the city and southeast around the Aqaqi River, Mojo River, and Qooka reservoir continue to suffer incalculable disaster. I also used the “life history” approach, which plays an important role in redressing the wrongs suffered by the people.

3.2. Interviews and Focus Group Discussion

In the interview, I asked the informants (individuals and group) to reflect on Oromo cultural ecology, on what is sacred and secular in their domain, on indigenous ecological practices handed down through collective memory, on their water harvesting personal experiences, on alter/native ways of balancing human–ecology solidarity, on the causes and consequences of the Qooqa crisis, and on the challenges to and limitations of indigenous ecological practices. Throughout the interview process, I obtained not only information (facts, names, and dates) from the interviewees, but also insights, thoughts, attitudes, beliefs, and practices relevant to the lake and other related issues. The study also involved focus group discussions in which five participants (four males and one female) discussed different aspects of the Qooqa crisis.

4. Interview Project and Discussion

In this section, the data collected on multiple narrative voices (multivocality) and nuanced senses of place (multilocality) about Lake Qooqa will be presented and discussed. This section is organized into two subsections.

First, contested worldviews:

- (a)

- Although it is generally agreed that the culture and tradition in which both Christianity and Islam emerged were Jewish and Arabic cultures, respectively, it remains unclear how both religious creeds could totally fit into the diverse cultures of the world in general and to the culture of the study area in particular.

- (b)

- It is equally puzzling how the (eco-)culture of the study area can accommodate non-indigenous religion (e.g., Islam, Christianity) without being marginalized itself.

Second, contested ecologies and the “bulee”/“algae” metaphor

- (a)

- It is to be discussed that by taking advantage of the lack of regulations and clear policies, state-owned facilities such as the Qooqa dam and the power plant, multinational corporations (e.g., floricultures), factories (e.g., tanneries), and local entrepreneurs (e.g., horticultural irrigation systems) unsettled the ecosystem, nullified the traditional ecological knowledge and culture, dislocated the local political system and integrity of the indigenous people (social cohesion), with immeasurable psychological impacts and incompensable loss of values.

- (b)

- Metaphorically speaking, the Oromo and other peoples around the capital, Finfinne (Addis Ababa), have been subjected as citizens as they suffer forced evictions and a wide range of injustices. Findings from available sources show that

- (1)

- the majority of dumping sites are in Oromia, concentrated around towns, riverbanks, and grazing lands (e.g, the controversial Sandafa landfill), and

- (2)

- industrial plants are located by the rivers and lake-sides with their effluents (locally called bulee) discharged into waterbodies. As a result of those randomly selected dumping sites and poor waste management systems, people suffer a prevalence of diarrhea, body allergy, cough, and other diseases (e.g., pneumonia and sinus).

These issues of environmental and human problems remain grave concerns for people in the study area following the building of the Qooqaa dam in 1960, the encroachment of factories, the expansion of floriculture, and the introduction of non-indigenous religious creeds resulting into a multiplicity of voices (multivocality) and nuanced senses of place (multilocality).

4.1. Social Memory and Personal Experience Narratives

The folkloric element of storying resentment in the narrative voice of informants from Amudde, Doddota District, East Arsi, and the descriptions of injustices depict the dystopia of the top-down policies and development plans that disregard the involvement of the local population. Bruce Bradshaw argues that narratives or deeper traditions and stories explain the world and shape perspectives, actions, and behavior of members of the communities and work as a background to everything visible in the culture (Bradshaw 2002, p. 240). Hence, social memory narratives carry the values and beliefs of the society and direct the daily life of the people, and it is fair to say that real changes will occur when the people take command of their narratives and transform their social–ecological system.

4.2. Five Interviews

As will be presented next, the data in this chapter confirm that the different factors that compel changes in the study area include different world-views and ideologies, dominant religious creed/s, varied and competing political systems, and top-down policies that often disregard the ground-up development strategies and internal dynamics of community decision making. A few cultural sites in the study area, the Jaanoo Muudaa Mountain near Balaale and Haroo Roobii near Amudde, among others, which are now totally abandoned because of both religious (Islamic) and development-induced (politico-economic) pressures upon the residents, and Lake Qooqa, have been emphasized in the interviews and group discussions.

To begin with, I asked my informants to recount the major causes of Lake Qooqa water pollution and other challenges from their perspective, what conflicting views and contested narratives they know of about the human and ecological catastrophe, what local knowledge is worth attending to to alleviate the social–ecological crisis from their lived experience and to make sound decisions about what affects their lives and the environment in which they live, what local strategies are used to recount the politics of resources, and what is to be done to envision better humanitarian and ecological situations.

My informants unanimously agreed that, traditionally, there were secret societies and sacred sites (mountains, well-springs, lakes, and sacred groves and trees) where people gathered to worship Waaqa (God) for rain, peace, abundance, and fertility and to make decisions about what affects their life and the environment in which they live. To date, those places have been abandoned, and local institutions are weakened mostly by externally induced factors, which are religious, sociocultural, and political (Lee and Newfont 2017).

4.2.1. Interview 1: Narrating Jaanoo Muudaa

- (a)

- What local knowledge is worth attending to in order to eco-culturally and historically alleviate the social–ecological crisis in the area, from your experience, and to make sound decisions?

Among other sacred sites in the study area where local secret societies used to meet for a pilgrimage is Mountain Jaanoo, which is located south of Balaale in Doddota District. It is characterized by degraded forests and fragments of volcanic eruption, which occurred several years ago, and its ash flows and ash falls are seen covering all the down-slope areas. The ritual site of the muudaa was at the foot of Mount Jaanoo, where seekkara ritual songs and dance performance were carried out until the practice was gradually banned, according to Ahmad Gammada Butta (75) of Balaale, following the influence of Islam in the area.

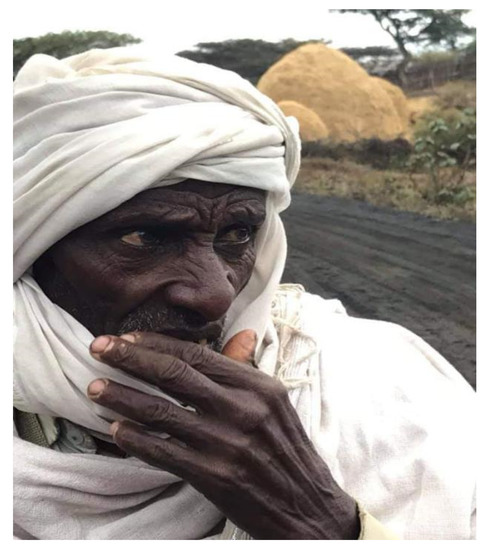

According to my informant, Ahmad Gammada of Balaale (Figure 2), the people of Doddota, Adama (Saapho Dabbullee), Hexosa, and many other neighboring districts in East Arsi make a pilgrimage in December to Jaanoo Muudaa to pray, worship Waaqa (God) together, sing songs, and perform ritual dances at the sacred site demarcated for the same purpose at the foot of Mount Jaanoo (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Ahmad Gammada (Inft.). Balaale. 27 January 2020. Photo, Author.

Figure 3.

Mount Jaanoo veiled in the cloud, morning, 27 January 2020, southwest of Balaale, and youth with a caravan of water jars from Qooqa (Haroo Roobii). Photo, Author.

Ahmad states in his words next the cultural significance of the ritual celebrated at Mountain Jaanoo in December

[Text 1]:…Zaara Jaanoo tu gahe jedhan. Achitti nami (Kirittaannis, Aslaammis, Waaqeffataanis) wal gaha. Waaqa kadhata. Waaqa faarsan; akkas jedhanii seekkaran:Jaaniyyoosiin godhanna faanooleenci hijaabaan (dhoksaan)jira Jaanoooh, Jaaniyyoo, againhere we come to your footDecorated, now and then then,your lions come home to their den

My informant (Ahmad Gammada) recommended to me two performers named Shubbisee Bobbaasaa Jaatanii and Hussein Galato (in Balaale), who, Ahmad said, are generally known in the area (Balaale) for their familiar talent in the Jaanoo Muudaa performance called seekkara. I met with Shubbise Bobbasa (70) and Hussein Galato (43) in Dheera on 4 March 2020, to collect data about Jaanoo Muuda and other social–ecological systems in the area. Both informants shared to me their lived experience and concern about the religious pressures that weakened the people’s cultural practices to maintain an ethical human–nature relationship, to be addressed broadly in the future in a separate study.

4.2.2. Interview 2: Narrating Haroo Roobii (i)

- (b)

- What conflicting views do you know of about the human and ecological crisis in Amudde?

Haroo Roobii (Roophii) is a natural lake near Amudde, Doddota District, eastern Arsi. Until it was over-flooded by the man-made Qooqaa Lake in 1960, Haroo Roobii was a sacred site and the sole source of pure water for the people and animals in and around Amudde. Hussein and Shubbise told me that Roobii Lake is called Marxifata on the Balaale side. The informants (Ayya Ubbe, Haj Gammachu, Obbo Fayyo, and others) generally agreed that Haroo Roobii was also another ritual site in the area, after Jaanoo Muudaa near Balaale, for the people to gather from all walks of life, irrespective of region, religion, or gender, and celebrate the Irreecha Thanksgiving ritual ceremony in Birraa, by the end of rainy season in September (Shunkuri 1998).

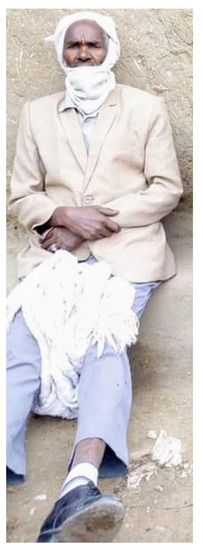

According to Ayyya Ubbe (Figure 4) of Amudde town, Haroo Roobii is an unforgettable ritual site for the Irreecha Thanksgiving ceremony. At the site, the Oromo women performed songs of rain, fertility, abundance, heroism, love, and light and danced, prayed, and chanted in praise of Waaqa (God) and Ateetee (the goddess of fertility) for the peaceful and quiet rainy season that led toward the shiny Birra season, which is suitable and convenient for all, including livestock and nature in general, on every side of the mountains and rivers and for the people to meet safely and securely.

Figure 4.

Ayya Ubbe, Amudde. 27 January 2020. Photo, Abadir, an assistant to the Author.

Sources indicate that the Rift Valley lakes are sources of water and have environmental, cultural, and economic significance (Yeshiemebet 2016; Masresha et al. 2011). Ayya Ubbee (infr.) confirmed to me that until they were prohibited by Sharia, men and women in the area went to the bank of Hara Roobii for Irreecha, a Thanksgiving festival in Birra, September. However, according to Ayya Ubbe, with the coming of a strong Islamic faith to the area, the people were told to drop and forget the indigenous practices labeled “seenaa shamaa”, i.e., “filthy tradition”, and to stick to Islam and abide by Sharia, as indicated in her words next.

[Text 2]:Me: -…seenaa Haroo Qooqaa kana qorachuudhaaf dhufnee, mee waa nutti himaa-…I have come to study the social memory narrative of the Qooqa lake, please tell us some stories about the lake from your experienceAyya Ubbee (A.U.): …sheena shamaa dha, dhiisaa ‘edhanii, nu dhiisisanii, kunoo salaatat’ gorree, irraanfannee, akkam goona egaa? …Bulee fi lolaalleen nu dhowwe.-…we were told to forget our tradition, to drop our folkways as backward, filthy, despicable, and we dropped it gradually, forced to forget it…what can we do?

After some observable reluctance and indecision, after some struggles to reach her memory pool, Ayya Ubbee performed some ritual songs of Irreecha thanksgiving that she once did with other young married women close to nature at the bank of Haroo Roobii, a small natural lake later over-flooded by the Qooqa dam.

[Text 3]:irreessaan sii dhufayaa malkaa, nagee nageeirreessaan sii dhufayaa malkaa, abeet abeetwe come to your bankwith a ritual grass, oh, sacred lakewe come with a ritual grassoh, sacred lake, oh, sacred lake

In the context of a religious group where she belonged, which is a Muslim group, my informant hesitantly shared with me a few pieces of information from her scant memory and confessed that she forgot the songs and stories about the sacred sites over-flooded by the man-made lake since her group was told to drop the “filthy backward tradition”, as it were, and to abide by Sharia. In this respect, I share James Fentress’ and Chris Wickham’s (Fentress and Wickham 1992) view that “the sorts of memories one shares with others are those which are relevant to them, in the context of a social group of a particular kind” (p. x). Social memory as a source of knowledge provides us with material for conscious reflection, and the social memory researcher “must situate groups (and group members) in relation to their own traditions, asking how they interpret their own ‘ghosts’, and how they use them as a source of knowledge” (p. 26). One remembers a memory of an event through performance, that is, through repetition, and Della Pollock (2005) rightly argues that.

At its most basic level, performance is a repetition. It is a doing again of what was once done, repeating past action in the time of acting. Because the repetition occurs in time, it differs from the original to the extent that any one moment differs from another (p. 11).

Furthermore, in spite of her effort to recite some of those sacred songs at the ritual site back then, Ayya Ubbe could hardly remember, and below are just a few of Ateetee songs she sang.

[Text 4]:A.U: …coqorsa qabannee, siinqee qabannee, okolee keenya qabannee, gaadii looniiqabannee, gubbaa teenya, Waaqa in kadhanna, harariima Birraa keessa, Masqala, Masqala.Irraanfadehee, qaata “salaatat’” dachaanee kana dhiifnee maal?Ateetiyyoo loonii tikaraan kashaan daggaggaleya fandalaleeAteetiyyoo loonii tiheexoo kashaan daggaggaleya fandalaleeheexoo kashaan daggaleeya giddii malee…jedhanii dalagan.Absooliyyoo nooraaAyyolee nooraasilaa dhufa hin ooltusi waamanii kottusilaa dhufa hin ooltuqophii kiyya kottu…nan irraanfadhe….kunoo, Allahuu Akubarii! kanatti jammarre (laughing).…holding a ritual grass and stick, our milk-gourd, our lactating cow-cord, we lower down to the sacred lake … pray to Waaqa (God), in Birraa (September), and sing songs of Ateetee, the goddess of fecundity……forced to forget it, to drop it, and turned forcefully to pray “salat”…what can we do?oh, Ateetee, Ateetee of the cattlethe road to come to you is so grassy, so bushyoh, you so proud, so grand, & majesticoh, Ateetee, oh, Ateeteethe path to you is so crowdedto come to you to pay homageoh, one must come one must come…thus, we used to sing in praise of Ateetee on the bank of Lake Roobii (now Lake Qooqa):oh, goddess, we are hereto greet you to worship youto call upon you to comewe trust, you never stop comingdown, oh, come to us, our Old Mother,Ayyolee come to my feast come….

The song above is an Ateetee ritual song of peace and fertility performed by women alone. Leila Qashu confirms that “For Arsi women, Ateetee cannot exist without song. Ateetee songs and the action of singing hold the power that solves problems (Dibaba 2020). Within Arsi culture, Ateetee is the only conflict resolution ritual organized and controlled by women and the only one that is sung” (Qashu 2016, p. 356). My informant (A.U.) stressed in her response to my question about whether people in Amudde stopped performing at Haroo Roobii simply because the lake was over-flooded by Qooqa Lake (Figure 5), or also because of the influence of Islam and pollution. She answered that people stopped because of Sharia, pollution, and over-flooding.

Figure 5.

Lake Roobii/Qooqa Lake. Amudde. 27 January 2020. Photo, Author.

[Text 5]:Me: Me waan Malkaa Roophii kanaawoo?A.U.: …lagni yoo duraa xiqqaa jedhani, akka burqituu wayiitii, hagasii asimmoo guddateeti daariitti as deeme ka roobii tu keessa gala, knf Haroo Roobii jedhan akka duraan jecha dhageenyetti natti fakkaata…amma wallaalee Ateetee isin jettan, haguma fudhattaniin deemaa (jette, koflaa, garuu saalfachaa fi waakkachaa, afaan ulfinaatiin)Me: -Haroo Roobiillee malkaan Awash dhufee irra galagalee jennaan dhiiftan moo?A.U.: Lakkii Sharia. Sharia tu nu harkaa gate.Me: …what do you know about Lake Roobii?A.U.: …in the past, we heard that it was a small lake made of a well-spring in which hypos lived, hence Haroo Roobii, and recently came to be in its present large size…… and now I am done with this Ateetee thing and about the Irreecha thanksgiving festival…you may be fine with what I told you (she commented very politely and laughingly that she forgot it, also that it may violate Sharia to sing).Me: …Then you stopped performing Irreecha on the Roobii Lake because the sacred lake wasover-flooded by Qooqa?A.U.: …no! never! the Irreecha thanksgiving festival was banned by Sharia.

Based on the above data, one can observe that the pressure of a non-indigenous religion, i.e., Islam, in the area is felt with remorse to this day, as those good old days, when people enjoyed close observation of and ethical relationship with nature, are long gone as a result of externally induced socio-political and cultural changes. In the past, secret societies of ritual leaders, community elders, rain makers, medicine-men, and, occasionally, the general public, met to worship Waaqa (God) on the bank of the Roobii sacred well-spring and experienced a most relaxing time. The gathering involved Ateetee ritual songs and dances for women, whereas, for men, a horse-race accompanied by suunsuma songs and several other performances, which are quite memorable.

The act of remembering is temporally limited, as in A.U.’s narrative. A.U. remembers the lake as a container of facts, as an object of historical loss, and only its blurry image surfaces in her fragmented stories. It makes sense to argue that “unless there is some special association that causes the memory to stick, we may find that we are simply unable to remember…” (Fentress and Wickham (1992, p. 39)). That is, to remember is to restore the text to its original version and to relocate it back to its social context, which helps the person establish a particular perspective on the past that the oral document represents. Fentress and Wickham (1992) put remembering in two parts, the distinction being between objective fact and its subjective interpretation: an objective part, which is comparatively passive, serves as a container of facts, and situated in a variety of locations, and the subjective part, which is more active and inbuilt, is located only within us, and holds knowledge, information, and feelings, which it experiences and recalls to consciousness (5).

Hence, from what my informants remember about the Oromo ecotheology, a close relationship between man and nature and nature and Waaqa (God) was indispensable (infrs. Ayya Ubbe & Haj Gammachu). Traditionally, it is common knowledge that “the Oromo ecotheology is mainly concerned with the nature of God, spirits, beliefs, and the relationship between God and humans, and between humans and the natural environment” (Kelbessa 2010, p. 62).

4.2.3. Interview 3: Narrating Haroo Roobii (ii)

- (c)

- What are the major causes of Lake Qooqa’s water pollution? Where is Haroo Roobii today? What local strategies are used to recount the politics of resources in the area, and what is to be done to envision better humanitarian and ecological situations in your view?

My informant, Haji Gammachu (H.G.) of Amudde (Figure 6), now a Muslim himself, shares Ayya Ubbe’s view and remembers with awe the men’s horse-race, the suunsuma song and dance, and men’s and women’s chants and prayers performed on Irreecha thanksgiving day in December on the bank of Haroo Roobii, in the old Qooqa plain of the Siiba Oromo.

Figure 6.

Haji Gammachu Tufaa Guutoo. Amudde. 27 January 2020. Photo Courtesy, Author.

[Text 6]H.G.: …Wanna fardaa tu jira ammammoo…malkaa san bu’uuf, gisee malkaa san irreessabaasani…gisee dubartiin magra qabattee, siinqee qabattee malkaaf baatu, nullee garmaamaa oollee, farda qabna, amma, malkaa irreeffachuuf deemnaMe: Malkaa kam?H.G.: Malkuma Roophii kana.biifoo biifooreeboo reebooCaanciyyo biifaadeebite kaawoon…jenna.H.G.: …there is also a tale of horse-race, of the suunsuma men’s song, while women, holding their siinqee (ritual stick), ritual grass sing, pray, and ululate to worship Waaqa on the bank of the sacred lake, Haroo Roobii, now covered by Lake Qooqa.And we sing a song of Irreecha:smear, spray (milk)smear smearplay, enjoyoh, Caanciyyoo,you who smear milkthat time has come back

I asked my informant to recount the story of Haroo Roobii and its surrounding, and he said the land now covered by the lake belonged to the Siiba clan of Jiille Oromo, Tuulma branch, who were washed away in the middle of the night, I was told, when the dam was intentionally opened to break Suuba’s fierce resistance to forced eviction from their ancestral land.

[Text 7]H.G: Haroo Roobii, burqaa wayii ture…dubartiin waraabbatanii qadaadanii biraagalan…burqituu dha, qadaada qaba…bakki Qooqaa kun in qotama, yeroo san, shunburaa qotama (bakka amma Qooqa irra ciise kana? Qooqaa kana, eeyyee)…gubbaa Siiba t’ jiraa…amma san yoo mangistiin irraa kaasuu jammaruu…dubartiin wayii, akka abbooti keenya nutti himan, deettuun, qadaada qabaa malkaan, deettuun wayii jarjartee yoo biraa deemtu, achumaan malkaan ganaffale jedhani…Awash immoo achii as Aanaa Booraa qabatee…Me: -Eenyutu irra jiraata ture, dur, bakka haroon kun irra ciisu, dur, eenyut’ qotata ture?H.G.: -Meedaa achi aanu, Siiba tu qotata ture, gamanaan Arsiin gabaabbinaan ni qabaa…loon tu dheeda…bosoqa tu jira, bosoqa kunoo akka shonkooraa kanat’ miyaawutu jiraa, …Me: -Siiba kun Jiille moo, kam?H.G.: -Jiille, eeyyee…Oromoo Jiillee…harma, sodda, waliin dheechifata nami yeroo san…(waliin dheechifata nami yeroo san?) …waliin dheechifata eeyyeeMe: -Amma waan suunsumaa, yeroo irreessaa san… me waan yaadattan…H.G.: -Suunsuma, nuti yeros dargaggoo dha…ka qabannu yeroo san nuyi…fardumaan garmaamuu kana bichaa…abbooti keenya suunsumanii dhiichisanii, qawwee tokkosan…ni suunsuman (ni geeraranii?…abbaa koo! balaan bu’e!)…nama faarsanii, biyya faarsanii, itti faarsanii…Giraammash Midhaansoo Nabii jedhanii, baalabbaata yeroo sanii…yeroo san farda keenya finnee, dubartiin itti elelfattii, birrii 2 birrii 1 akkana in kenninaafii…baqqaa nuti ulee keenya, farda keenya qabannee, meedaa garmaamaatti dachaana…Me: -Yoomii kaasee ti bishaan kun kan faalamuu jalqabe, …bara kami kaaseeti? Buleen kun kemikaalaa?H.G.: -waan isaa beennaa? qaancaa wayii faaqan jedhan …warshaarraa dhufa…-…mootummaan dhaabatee nurraa dhowwuu dandaha…daangessuu dandaha, bishaan fidee daariitti nuu baasuu in dandaha…mootummaat’ nuttiraa dhiisi…-Bishaan kan dhufee, bara 1959/60 waan taheefi…buleen tokko Awaash irraanqodaa afrikaa jedhani…kun kan kopheeti jedha…kun kan qaacaa itti faaqan jedha, san itti dhangalaasanii, buleen irraan galagallaan nama hin obaasu…(Me: Nama hin obaasu)…nama hin obaasu…isuma duranuu rakkoo tu ture…Rabbuma tu nu jiraachise malee…harreen keessatti dhugee fincaaha…loon dhugee keessatti fincaaha…sareelleen in dhuga…achuma keessatti fincaaha….garuu namillee isuma dhugnaamiiree…haa tahuummoo yeroosan nami hin duunee, amma eega buleen kun dhufee amma…re’een dhume,…, qotiyyoon du’e…H.G.: -of Haroo Roobii…Haroo Roobii was a well spring. Women fetch water from the small lake and close head of the spring…people plow the Qooqa plain back then …. Siiba of the Jiillee branch lived and plowed there…and Arsi…now, when the government started eviction for the dam, we were told, a nursing mother, hurriedly left the well spring open and it flooded the plain in its surrounding until it was over-flooded by the Qooqa dam…and then Awash River through the Booraa district was feeding into the dam…Me: -who were residents back then on the Qooqa plain and in its surroundings?H.G: -Suuba of Jiillee, and Arsi, east side of the lake. And it was rich in a pasture and water … for cattleMe: -Some Suunsua songs please …that you performed on the Irreessa festivalH.G.: -We were young for suunsuma. We enjoyed the horserace…our fathers sang suunsuma anddanced…they sang and praised dignitaries …landlords …such as Left-Lieutenant Midhaansoo Nabii and the like … it was huge fun, a joyous time for everone …men and womenMe: -when did the dam start …and what is bulee about?H.G.: -the government does not care … we are helpless…desperate ……the lake was made in 1959/1960. No one knows for sure where the bulee comes from …some say from a tannery, some say from a cord manufacturing factory…once they discharge bulee, it is hard to use the water for drinking but we have no choice…Rabbi (God) protected us so far but we are not safe…in the past, the lake (Qooqa) was not clean either…livestock drink and urinate and defecate in the lake, and dogs and wild beasts do the same …however, that was not quite deadly…with the bulee nowadays, though, animals and people are dying…

4.2.4. Interview 4: Amina’s Personal Story

- (d)

- What happened to you, Amina, and to your family, and who was responsible?

Qooqa dam (Figure 7), as already discussed in the “Research Setting”, is found on the Awash River in the East Shawa Zone, 75 km southeast of Finfinnee (Addis Ababa), the capital, and south of the main Mojo-Adama road. Galila is one of the lakes around the Qooqa reservoir and located 20 km south of Mojo town via the Rift Valley road toward Maqi with an area of about 180 square kilometers. The ecosystem around the lake includes the surrounding farmlands, the Awash River, the woodland, and the hot-spring below the dam. The only large trees left around the shores of the lake are qilxuu (figs) as a result of clearing for crop cultivation. Although the main human activity in the area is farming with a special focus on growing horticultural crops and pulses using the alluvial soil, in the area where eviction and pollution became a social problem for over 60 years, land and land resources have been a bone of contention.

Figure 7.

Lake Qooqa. Amudde. 27 January 2020. Photo Courtesy, Author.

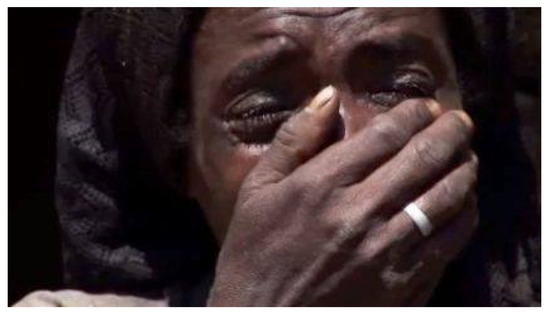

Amina is one of the thousands of residents in Amudde who use the Qooqa Lake as the only source of water for drinking, cooking, and washing, as well as for livestock. The February 2009 documentary titled the “Green Lake” by Al Jazeera BBC English Television featured Amina, who lives today shedding tears for her six dearly missed children and her husband, whose deaths were connected to water-related diseases.

The following is a summary of Amina’s personal narrative from Amudde, Oromia, which I obtained from the Al Jazeera English program titled People and Power (2009) while I was in exile in USA and later heard the story from Amina in Amudde. Amina confirmed it to me on my visit on 27 January 2020, in Amudde, that the interview (a situational context) was intended primarily to investigate the human and environmental crisis in Amudde village, Qooqa area. Next, with the story I collected from Amina herself (Figure 8) in Amudde town, I relocated Amina’s personal experience narrative in a social–material context (social and environmental justices) and in a symbolic–cultural context (social memory/a historical grief of loss).

Figure 8.

Amina. Courtesy of Aljazeera BBC, “People and Power” program (21 February 2009).

[Text 8]I gave birth to nine children. Six of them died: Makida, Hadiri, Tahir, Sultan, Kasim, Kalil. Three survived. My husband also died. I have lost seven members of my family. They were all vomiting and having diarrhea with blood in it. We visited a health center, but we were told the problem was associated with water. I feel sad about my dead children and husband. I wake at night thinking of them, and I now worry if my remaining children will survive. I don’t even know if I will survive. Except for God, we have no hope.

Amina is an Oromo mother of nine in Amudde village, near Lake Qooqa. Amina’s Story is about water pollution and the dire human and environmental impacts of reckless “development” plans in Ethiopia. I see her personal experience narrative as a symbolic representation of many other unheeded narratives of resentment about social and ecological crisis in the area and elsewhere in Oromia. As Amina’s personal experience narrative shows, the pollution of Lake Qooqa in her locality caused over time the consequent human and environmental crises, the tragedy that has become an example of the price of “development without freedom” in the country. Amina’s story focuses on the loss of seven members of her family, the historical grief of loss, and a collective memory (shared experience) of the Oromo. This experience of a historical loss is so universal because each story is believed to “echo one or more meta-narratives, local or universal” (Tuval-Mashiach 2014, p. 130).

Upon my visit to Amudde on 27 January 2020, and later, I got a chance to meet with Amina and talked with her about her story of the 2009, her tragic life experience, the loss of her seven family members, and her current life condition. It was quite heartbreaking to hear her account that officials harassed Amina (Figure 9) for telling her accounts of the loss to Al Jazeera BBC reporter in 2009, one year before the national election of 2010. Amina said she was reprimanded and bitterly blamed by the federal and regional officials for telling her stories to Al Jazeera Television about the possible cause of the death of her seven family members, that is, bulee (toxic algae, contamination, or water pollution). Until I left Ethiopia on forced exile in July 2010 to the USA, after repeated persecutions and imprisonment for my writings and speaking to power, I knew that local and regional officials were very cautious about the local people providing information related to the ongoing gross human rights violations in Oromia, which could, no doubt, affect the unfree and unfair national election result.

Figure 9.

Amina, 27 January 2020, Amudde. Sad, broken, and desperate look. Photo, Author.

Haj Abdu, the then administrator of Amudde, confirmed to me in Amina’s presence on 27 January 2020, in Amuude that the incident related to her interview with Al Jazeera BBC was highly politicized. The reason was that the 2010 election was approaching as the documentary was spread worldwide. In effect, the then president of Oromia Regional State, Junadin Saddo, I was told, was pressured to visit the area and promised clean drinking water, electricity, schools, health stations, and roads to calm down the resentful people, none of which were fully materialized; however, after the 2010 national election result was declared, the ruling party called the election fraud a landslide—an overwhelming victory.

4.2.5. Interview Five: Narrating Lake Qooqa

- (e)

- What are the major causes of Lake Qooqa water pollution and other challenges to the people and to the environment in which you live? What conflicting views do you know of about the human and ecological crisis in Amudde, and what is to be done?

Lake Qooqa, with an area of 180 square kilometers (69 m2), has a variety of wildlife and birds around the lake. It is reported that the lake contributes to the country’s aquaculture with its 625 tones of fish landed each year. Both the lake and reservoir are threatened by increasing sedimentation caused by environmental degradation and the invasive water hyacinth.

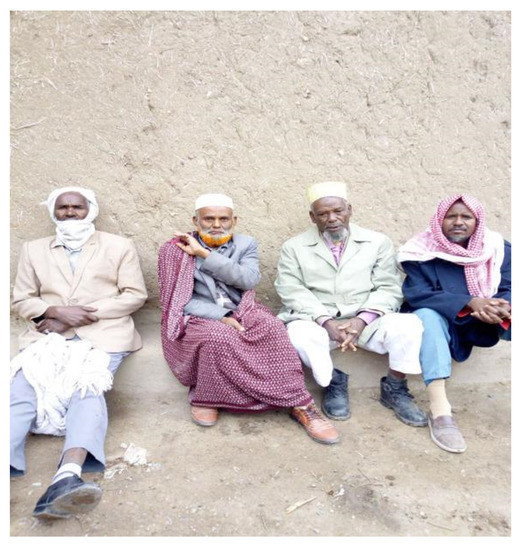

I presented to the elders (Figure 10) (a group of four Muslims picked at random) the interview questions next for their personal reflections and open discussions: major causes of Lake Qooqa (and Haroo Roobii) water pollution and other challenges from their perspective, conflicting views and contested narratives they know of about the human and ecological crisis in the area, what local knowledge is worth attending to to alleviate the problem from their lived experience, local strategies used to recount the politics of resources, and what is to be done.

Figure 10.

Community elders (Social Group). Amudde, 27 January 2020. Photo, Author.

When I asked Haji Gammachu Tufaa (left) and his group (left to right: Suleiman Jibril, Fayye Jirruu, and Mohammad Qumbii) in Amudde,

- (1)

- Has someone died you have heard of, or animals, related to Lake Qooqa, and what is the cause?

First, Haji Gammachu (H.G.) said the following, to the confirmation of other informants:

[Text 9]H.G.: …eeyee, likki likkii…lagarratti nami du’e…maqaasaan dagadhe…kanaachi, re’een in dhume, qotiyyoon in dhume, loon in dhumani…iyyanne, amma aanatti…bishaan nama fixuu jammaree….bishaan qulqulluu barbaannaa…bishaan bulee san nurraa dhaabaa….ykn baqqaa dhumuu jammarree…jennee …eegasii bishaan birkaan tokko jammaree sunuu yawusuma dhufee dhaabatee, akkasumatti…H.G.: …oh, yes. someone died on the lakeside…I forgot his name…except that someone …animals died…goats, oxen, cattle, … then we went to the district with complaints for a pure water… that cattle are dying and people are dying too…then a pipe line was set up…

My other concern was the availability of a functional local institution to speak for the people, to defend the local interest focusing on their prime concern, and I asked the community elders:

- (2)

- What available local institutions are functional to alleviate the ecological and human crisis?

Some of the community elders in the group had served as members of the local Water Management Committee. Haji Gammachu (H.G.) was one of them and said,

…bishaan boombaa takkaa magaala Goondeerraa dhaabatee…anuu kunoo an koree bishaaniiti mataa kiyyaa [H.G.] …haga Goondee deemee iyyadhe, haga aanaa deemnee…qaamni adda addaa dhufaniima ilaalanii, wanti nuuf godhan hin jiru………yoo lafaa qotan bishaan in baha…bishaan qulqulluu…in bahaa nuu baasaa jenne, boollayyuu nuu baasuu didanii….sanuma dhugaa jirra…bishaan boollaayyuu immoo kunoo Zuway Duddaarraa kan baasan dhibee godhatee, nama hube…inniyyuu qoratamuu barbaachisa, bishaan boollaayyuu…Me: -amma maal dhuddu isin ree?…-laguma san dhugna… a pipe line from Goondee to Amudde…I myself (H.G.) am member of the Water Management Committee …and then it stopped soon…now no clean water…and we placed our complaints to the district officials and no one paid attention to……even boreholes …drilling wells…can be risky…need to be checked in a laboratory by experts for safety …for example, from Zuway Duddaa, a borehole was drilled and was not safe…it hurt lives…even boreholes need care …

- (3)

- Now, what is your source of drinking water?

Group (G): nothing. just Qooqa, with the bulee (contamitants)

The stories my informants told were their personal life experience of over sixty years in Amudde, and they storied their first-hand accounts of the severity of life-threatening waste discharges into Qooqa Lake.

A study from Debub University and the University of Wales reported in 2001 that the blue–green algae (cyanobacteria), locally called bulee, covers a large area of the lake and causes liver damage, neurotoxicity, and tumor promotion with symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders, fever, and irritation of the skin, ear, eyes, throat, and respiratory tract (Zinabu and Pearce 2003; Yeshiemebet 2016). It has been confirmed in another study that “the most predominant water borne disease, diarrhea, has an estimated annual incidence of 4.6 billion episodes and causes 2.2 million deaths every year” worldwide (Erena 2015, p. 1).

When I asked the group how they could survive and what happened to Amina and her family, they said, if not for Rabbi (Allah), they would have all perished:

- (4)

- What happened to Amina? What caused the death of seven members of her family do you think?

Mohammed Qumbi’s view was the following: