Gendered and Racial Injustices in American Food Systems and Cultures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Wrongs without Wrongdoers: Structural Food Injustices That Disadvantage Women and Minorities

2.1. Dolores’s Choices

2.2. Wrongs with(out) Wrongdoers

Social structures do not constrain in the form of direct coercion of some individuals over others; they constrain more indirectly and cumulatively as blocking possibilities. Part of the difficulty of seeing structure, moreover, is that we do not experience particular institutions, particular material facts, or particular rules as themselves sources of constraint; the constraints occur through the joint action of individuals within institutions and given physical conditions as they affect our possibilities.

2.3. Situating Responsibility

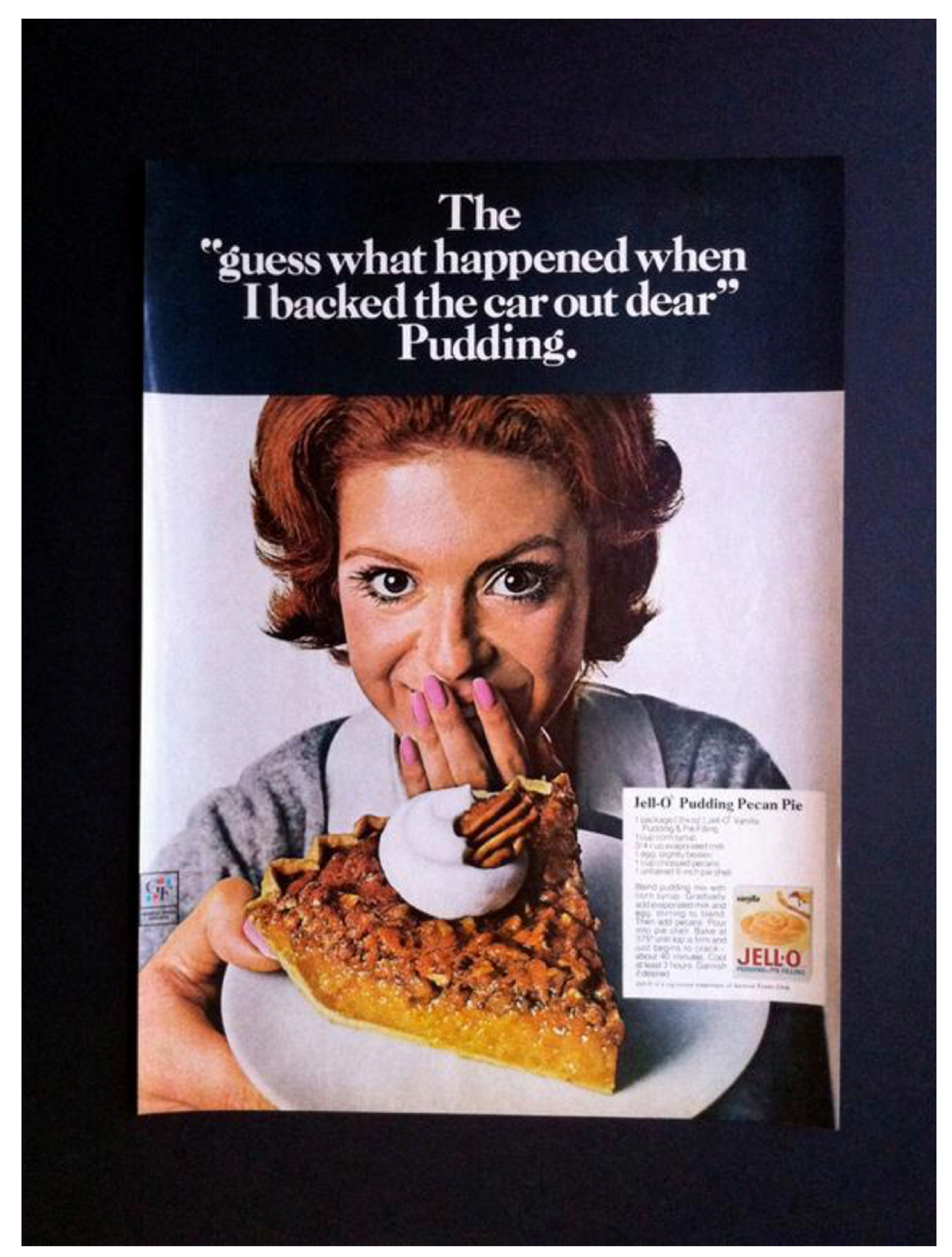

3. Women and Womanliness: Gendered Food Injustices in American Culture

3.1. The Hazards of Gendered Food Injustice

3.2. Responsibility without Agency

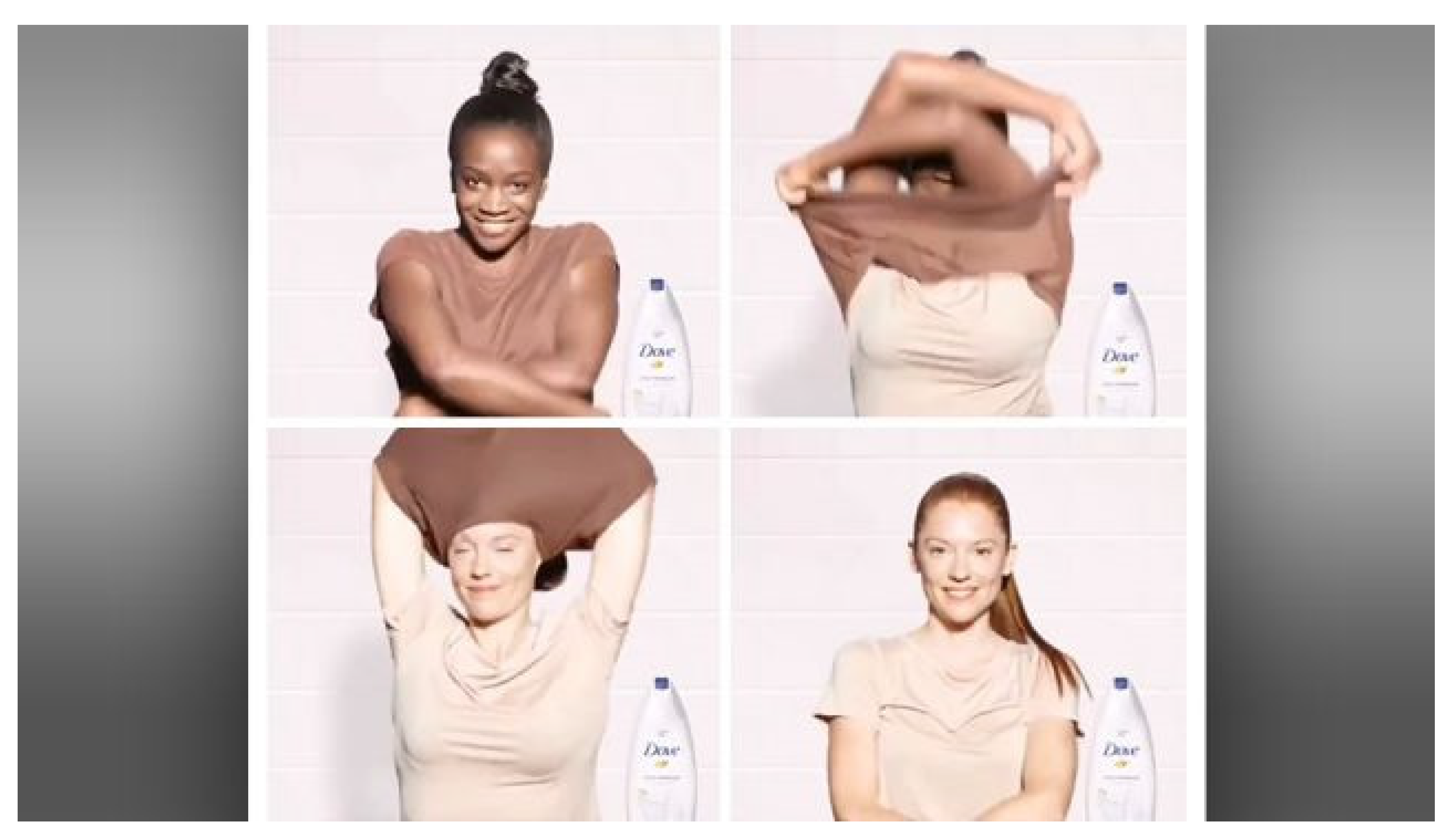

3.3. Women as Food

4. The “Ideal” Mediterranean Diet?: The Risks of Promoting De-Territorialized Foodways without Cultural Context

4.1. The De-Territorialization of the Mediterranean Diet

4.2. The Dangers of the “Best” Dietary Model

4.3. Re-Territorializing Traditional Foodways

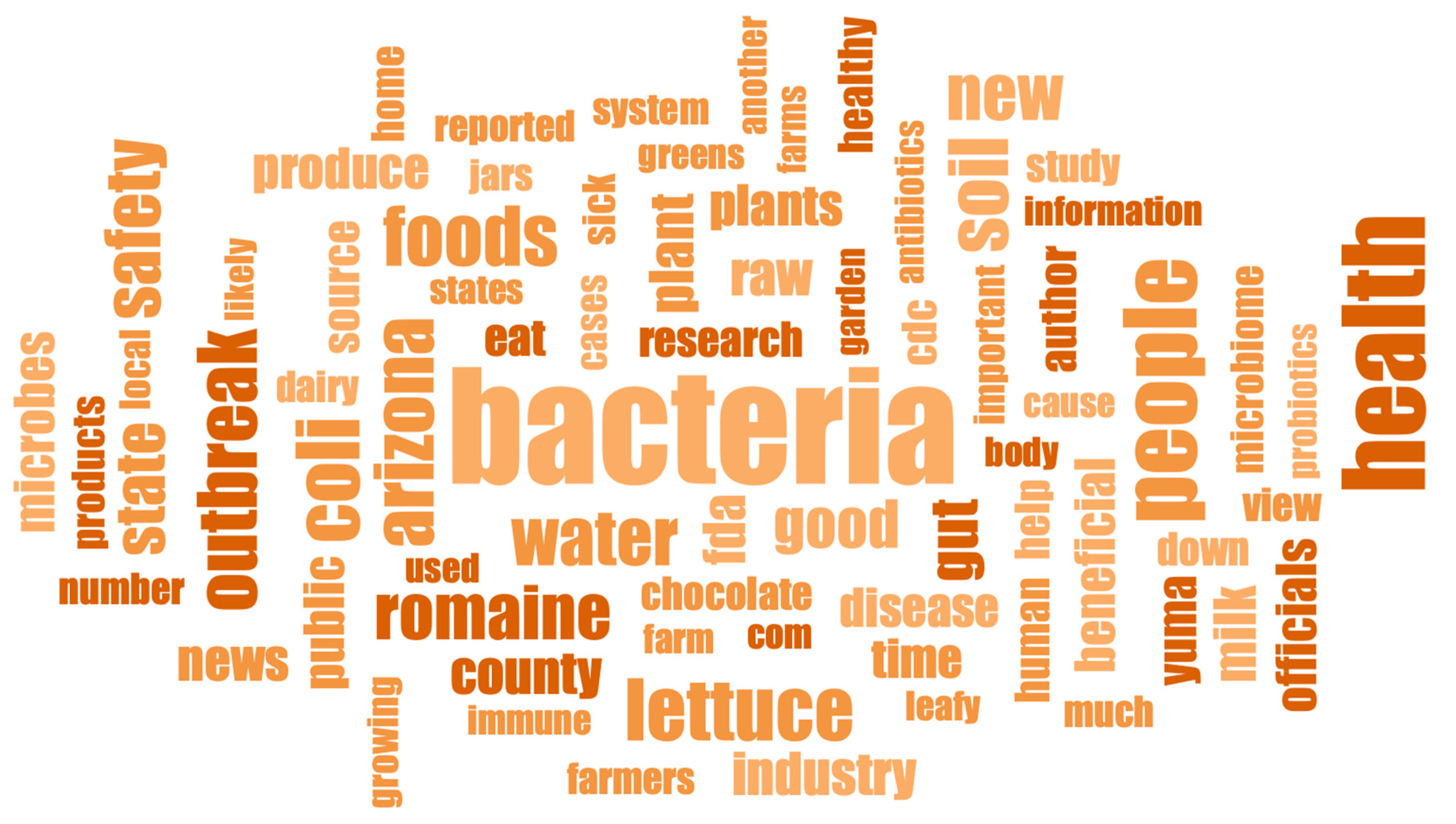

5. Food Contamination Standards That Can Foster or Reduce Food Injustice

5.1. Practicing Gotho in a New Land

5.2. Talking about Food Safety

5.3. Making Gundruk, Safely

5.4. New Lexicon, New Culture

6. Designing Food Artifacts for Social Justice and Sustainability

6.1. Micro and Macro Level Food Systems by Design

6.2. Critical and Systemic Design

6.3. A Critical and Systemic Approach to Designing Food Artifacts

7. Conclusions: Using Critical and Systemic Design Principles to Promote Food Justice and Sustainability

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Carol J. 2014. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, 20th anniversary ed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrowicz, Lukasz, Rosemary Green, Edward J. M. Joy, Pete Smith, and Andy Haines. 2016. The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 11: e0165797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkon, Alison Hope. 2012. Black, White, and Green: Farmers Markets, Race, and the Green Economy. Athens: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, Alison Hope. 2014. Food Justice and the Challenge to Neoliberalism. Gastronomica 14: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, Alison Hope, and Teresa Marie Mares. 2012. Food Sovereignty in US Food Movements: Radical Visions and Neoliberal Constraints. Agriculture and Human Values 29: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 1999. What’s the point of Equality? Ethics 109: 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, John J. B., and Marilyn C. Sparling. 2015. The Mediterranean Way of Eating: Evidence from Chronic Disease Prevention and Weight Management. Boca Raton: CRC Group. [Google Scholar]

- Avakian, Arlene Voski, and Barbara Haber. 2005. From Betty Crocker to Feminist Food Studies: Critical Perspectives on Women and Food. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Badger, Emily. 2017. How Redlinings Racist effects Lasted for Decades. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/24/upshot/how-redlinings-racist-effects-lasted-for-decades.html?smid=em-share (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Barbercheck, Mary, Kathryn Brasier, Nancy Ellen Kiernan, Carolyn Sachs, and Amy Trauger. 2014. Use of Conservation Practices by Women Farmers in the Northeastern United States. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 29: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, Patrick Francis. 2016. Ordering People and Nature through Food Safety Governance. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkley, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bloome, Deirdre. 2014. Racial Inequality Trends and the Intergenerational Persistence of Income and Family Structure. American Sociological Rreview 79: 1196–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, Nicholas A., Zachery T. Lewis, Kyria Boundy-Mills, and David A. Mills. 2016. A New Perspective on Microbial Landscapes within Food Production. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 37: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissette, Christy. 2017. Is Meat Manly? How Society Pressures Us to Make Gendered Food Choices. Washington Post. January 25. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/is-meat-manly-how-society-pressures-us-to-make-gendered-food-choices/2017/01/24/84669506-dce1-11e6-918c-99ede3c8cafa_story.html (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Brown, Sandy, and Cristy Getz. 2011. Farmworker Food Insecurity and the Problem of Hunger in California. In Cultivating Food Justice. Edited by Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 121–46. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, Lawrence. 2011. Food Standards: The Cacophony of Governance. Journal of Experimental Botany 62: 3247–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadieux, Kirsten Valentine, and Rachel Slocum. 2015. What Does It Mean to Do Food Justice? Journal of Political Ecology 22: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, Kate, and Josee Johnston. 2015. Food and Femininity. London: Bloomsbury Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Contois, Emily. 2019. ‘Lose like a Man’: Gender and the constraints of self-making in Weight Watchers Online. In Feminist Food Studies: Intersectional Perspectives, 1st ed. Edited by Barbara Parker, Jennifer Brady, Elaine Power and Susan Belyea. Toronto: Women’s Press, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Contois, Emily J. H. 2020. Diners, Dudes, and Diets: How Gender and Power Collide in Food Media and Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Temra. 2010. Farmer Jane: Women Changing the Way We Eat. Layton: Gibbs Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Counihan, Carole M., and Steven L. Kaplan, eds. 1998. Food and Gender: Identity and Power. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, Joop, and Harry Aiking. 2017. Pursuing a Low Meat Diet to Improve Both Health and Sustainability: How Can We Use the Frames That Shape Our Meals? Ecological Economics 142: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, Sunny. 2020. Coronavirus Is Attacking the Navajo ‘Because We Have Built the Perfect Human for It to Invade’. Scientific American. July 8. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/coronavirus-is-attacking-the-navajo-because-we-have-built-the-perfect-human-for-it-to-invade/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Downey, Liam. 2005. Assessing Environmenta Inequaity: How the Conclusions we draw vary according to the Definitions we employ. Sociological Spectrum: The Official Journal of the Mid-South Sociological Association 25: 349–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, Rob. 2018. Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets and Honeybeeds, the Natural History of Where We Live. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- DuPuis, E. Melanie. 2002. Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elmes, Michael B. 2018. Economic Inequality, Food Insecurity, and the Erosion of Equality of Capabilities in the United States. Business & Society 57: 1045–74. [Google Scholar]

- Farag El sheikha, Aly. 2018. Revolution in fermented foods: From artisan household technology to the era of biotechnology. In Molecular Techniques in Food Biology: Safety, Biotechnology, Authenticity and Traceablity. Edited by Aly Farag El sheikha, Levin Robert and Jianping Xu. Hobolken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 241–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fonte, Maria. 2018. Food relocalisation and knowledge dynamics for sustainability in rural areas. In Naming Food After Places: Food Relocalisation and Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Development. Edited by Maria Fonte and Apostolos G. Papadopoulos. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, Caroline, Sonia M. Grandi, and Mark J. Eisenberg. 2013. Agricultural subsidies and the American obesity epidemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 45: 327–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedan, Betty. 1963. The Feminine Mystique. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Gohal, Amanpreet K. 2017. The Lifeworlds of Urban Women Farmers in Sustainable Agriculture. Ph.D. dissertation, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/docview/1877998799?pq-origsite=summon (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Gottliev, Robert, and Anupama Joshi. 2010. Food Justice. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Granai del Mediterraneo, Digital Archive Curated by University of Naples, SOB. 2013. Interview with Delia Morinelli by Elisabetta Moro. Available online: http://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/granai-del-mediterraneo-cura-delluniversita-di-napoli-sob/delia-morinelli-cuoca-di-ancel-e-margaret-keys (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Grosso, Giuseppe, and Fabio Galvano. 2016. Mediterranean Diet Adherence in Children and Adolescents in Southern European Countries. NFS Journal 3: 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, A. Breeze, ed. 2020. Sistah Vegan: Black Female Vegans Speak on Food, Identity, Health & Society, 2nd ed. New York: Lantern Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Deborah Ann, and Patti Giuffre. 2015. Taking the Heat: Women Chefs and Gender Inequality in the Professional Kitchen. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haslanger, Sally. 2012. Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 315-ff. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein, Neva. 2011. Matters of Scale and the Politics of the Food Safety Modernization Act. Agriculture and Human Values 28: 577–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, Anthony Ryan, Sonya Sternlieb, and Julia Gordon. 2019. Sugar ecologies: Their metabolic and racial effects. Food, Culture & Society 22: 595–607. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, Sarah M., Christine Agnew-Brune, Mark Anderson, Laura D. Zambrano, Charles E. Rose, Melissa A. Jim, Amy Baugher, Grace S. Liu, Sadhna V. Patel, Mary E. Evans, and et al. 2020. COVID-19 among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons—23 States, January 31–July3, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69: 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawthorne, Stephanie, Kathy D. Geller, Salvatore Falletta, and Adrienne Juariscio. 2017. A Hidden Community: Narrative Journeys of Young Black Women with Eating Disorders. Ph.D. dissertation, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/1961236459/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Herkes, Ellen, and Guy Redden. 2017. Misterchef? Cooks, Chefs and Gender in MasterChef Australia. Open Cultural Studies 1: 125–39. Available online: https://doaj.org/article/25e1a30da8634fa3a9b8230f5411fec8 (accessed on 1 April 2021). [CrossRef]

- Holt-Gimenez, Eric. 2011. Food Security, Food Justice, and Regime Change. In Cultivating Food Justice. Edited by Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 309–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Elizabeth. 2017. ‘You Can’t Say You’re Sovereign if You Can’t Feed Yourself’: Defining and Enacting Food Sovereignty in American Indian Community Gardening. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 41: 31–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Laura C., and Carolyn Gunther. 2015. A Historical Review of Changes in Nutrition Standards of USDA Child Meal Programs Relative to Research Findings on the Nutritional Adequacy of Program Meals and the Diet and Nutritional Health of Participants: Implications for Future Research and the Summer Food Service Program. Nutrients 7: 10145–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horst, Megan, and Amy Marion. 2019. Racial, ethnic and gender inequities in farmland ownership and farming in the U.S. Agriculture and Human Values 36: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Sarah. 2020. Food from home and food from here: Dissaembling locality in local food systems with refugees and immigrants in Anchorage, Alaska. In The Immigrant-Food Nexus: Borders, Labor, and Identity in North America. Edited by Julian Agyeman and Sydney Giacalone. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Inness, Sherrie A. 2001. Kitchen Culture in America Popular Representations of Food, Gender, and Race. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Interview with Giuseppina and Rosetta by Elisabetta Moro. n.d.Available online: https://www.granaidellamemoria.it/index.php/it/archivi/granai-del-mediterraneo-cura-delluniversita-di-napoli-sob/giuseppina-e-rosetta (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Irwin, Terry. 2015. Transition Design: A Proposal for a New Area of Design Practice, Study, and Research. Design and Culture 7: 229–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, Terry. 2018. The emerging transition design approach. In Design Research Society Conference DRS2018. Edited by Cristiano Storni, Keelin Leahy, Muireann McMahon, Erik Bohemia and Peter Lloyd. Londonvol: Design Research Society, pp. 968–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Anetta, Tom Silverstone, Max Duncan, Jess Gormley, and Christ Michael. 2019. The Food Deserts of Memphis: Inside America’s Hunger Capital | Divided Cities. The Guardian. November 20. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/video/2019/nov/20/theres-food-its-just-not-real-food-inside-americas-hunger-capital-video (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Jovanovski, Natalie. 2017. Digesting Femininities: The Feminist Politics of Contemporary Food Culture. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Julier, Alice. 2019. The political economy of obesity: The fat pay all. In Food and Culture, 4th ed. Edited by Carole Counihan, Penny Van Esterik and Alice Julier. New York: Routledge, pp. 462–79. [Google Scholar]

- Karpyn, Allison E., Danielle Riser, Tara Tracy, Rui Wang, and Y. E. Shen. 2019. The changing landscape of food deserts. UNSCN Nutrition 44: 46–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keys, Ancel, and Margaret Chaney Keys. 1959. Eat Well and Stay Well. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Aya H., Charlotte Biltekoff, Jessica Mudry, and Jessica Hayes-Conroy. 2014. Nutrition as a project. Gastronomica 34: 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klindienst, Patricia. 2006. The Earth Knows My Name: Food, Culture, and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law, John, and Annemarie Mol. 2008. Globalisation in Practice: On the Politics of Boiling Pigswill. Geoforum 39: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, Isaac Sohn, Jaclyn Wypler, and Michael Mayerfeld Bell. 2019. Relational Agriculture: Gender, Sexuality, and Sustainability in U.S. Farming. Society & Natural Resources an International Journal 32: 853–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Ellen. 2018. Lesbian Mothers: Accounts of Gender in American Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenmeyer, Antje. 2006. ‘Lesbian Appetites’: Food, Sexuality and Community in Feminist Autobiography. Sexualities 9: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques da Silva, Antonio José. 2018. From the Mediterranean Diet to the Diata: The Epistemic Making of a Food Label. International Journal of Cultural Property 25: 573–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Blake, Mari Kate Mycek, Sinikka Elliott, and Sarah Bowen. 2019. Low-income mothers and the alternative food movement: An intersectional approach. In Feminist Food Studies: Intersectional Perspectives, 1st ed. Edited by Barbara Parker, Jennifer Brady, Elaine Power and Susan Belyea. Toronto: Women’s Press, CSP Books, Inc., pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Carolyn. 1996. Earthcare: Women and the Environment. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Tina. 2020. How the Mediterranean Diet Became No. 1—And Why That’s a Problem. The Conversation. March 19. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-the-mediterranean-diet-became-no-1-and-why-thats-a-problem-131771 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Moro, Elisabetta. 2014. La Dieta Mediterranea. Mito e Storia di Uno Stile di Vita. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, Bonnie. 2019. Design in the Age of Climate Change. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 5: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, Marion. 1995. Mediterranean Diets: Historical and Research Overview. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 61: 1313S–20S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, Marion. 2002. Food Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle, Marion. 2003. Safe Food: Bacteria, Biotechnology, and Bioterrorism. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nestle, Marion. 2018. Unsavory Truth. How Food Companies Skew the Science of What We Eat. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nettles-Barcelón, Kimberly D., Gillian Clark, Courtney Thorsson, Jessica Kenyatta Walker, and Psyche Williams-Forson. 2015. Black Women’s Food Work as Critical Space. Gastronomica 15: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York Law School Racial Justice Project. 2012. Unshared Bounty: How Structural Racism Contributes to the Creation and Persistence of Food Deserts. (with American Civil Liberties Union). Racial Justice Project. Book 3. Available online: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/racial_justice_project/3 (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Nicol, Poppy, and Alice Taherzadeh. 2020. Working Co-operatively for Sustainable and Just Food System Transformation. Sustainability 12: 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Donald, and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2015. DesignX: Complex Sociotechnical Systems. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 1: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha. 2003. Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and Social Justice. Feminist Economics 9: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoms-Young, Angela M., and M. A. Bruce. 2018. Examining the Impact of Structural Racism on Food Insecurity: Implications for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities. Family & Community Health 41: S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, Katherine J. 2006. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, Raj. 2007. Stuffed and Starved. Brooklyn: Melville House. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, Heather. 2019. ‘Don’t Pack a Pest’: Parts, Wholes, and the Porosity of Food Borders. Food, Culture & Society 22: 657–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penniman, Leah, and Karen Washington. 2018. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. Chelsea: Chelsea Green Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, Ruth, Liping Pan, and Heidi M. Blanck. 2019. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Adult Obesity in the United States: CDC’s Tracking to Inform State and Local Action. Preventing Chronic Disease 16: 180579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, Diane. 2016. Resisting the Male Gaze: Feminist Responses to the ‘Normatization’ of the Female Body in Western Culture. Journal of International Women’s Studies 17: 133–51. Available online: https://go-gale-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/ps/i.do?p=CWI&u=asuniv&id=GALE%7CA443011529&v=2.1&it=r (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Probyn, Elspeth. 2018. An Ethos with a Bite: Queer Appetites from Sex to Food. Sexualities 2: 421–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, Laura. 1996. Environmentalism and Economic Justice: Two Chicano Cases from the Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan Swain, Manas, Marimuthu Anandharaj, Ramesh Chandra Ray, and Rizwana Parveen Rani. 2014. Fermented Fruits and Vegetables of Asia: A Potential Source of Probiotics. Biotechnology Research International 2014: 250424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, Ashante M. 2018. Food access in the United States. In Gender: Space. Part of the Macmillan Interdisciplinary Handbooks: Gender Series. Edited by Aimee Meredith Cox. Farmington Hills: Macmillan Reference USA. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/36153608/_Food_Access_in_the_United_States_in_Gender_SpacePart_of_the_Macmillan_Interdisciplinary_Handbooks_Gender_series._Aimee_Meredith_Cox_ed._Farmington_Hills_MI_Macmillan_Reference_USA_2018 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, Carolyn, Mary Barbercheck, Kathryn Braiser, Nancy Ellen Kiernan, and Anna Rachel Terman. 2016. The Rise of Women Farmers and Sustainable Agriculture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schieder, Jessica, and Elise Gould. 2016. Women’s Work and the Gender Pay Gap: How Discrimination, Societal Norms, and Other Forces Affect Women’s Occupational Choices—And Their Pay. Available online: https://www.epi.org/publication/womens-work-and-the-gender-pay-gap-how-discrimination-societal-norms-and-other-forces-affect-womens-occupational-choices-and-their-pay/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Schösler, Hanna, Joop de Boer, Jan J. Boersema, and Harry Aiking. 2015. Meat and Masculinity Among Young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch Adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 89: 152–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrinis, Gyorgy. 2015. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice. New York: Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Elizabeth A. 2018. Betty Crocker Versus Betty Friedan: Meanings of Wifehood Within a Postfeminist Era. Journal of Family Issues 39: 843–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Herbert Alexander. 1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slocum, Rachel, and Kirsten Valentine Cadieux. 2015. Notes on the Practice of Food Justice in the U.S.: Understanding and Confronting Trauma and Inequity. Journal of Political Ecology 22: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, Jyoti Prakash, Victor Ladero, Robert Hutkins, Shannon Rezac, Reen Kok, and Melanie Heermann. 2018. Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms. Frontiers in Microbiology 1: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Becky Wangsgaard. 2019. ‘A way outa no way’: Eating problems among African-American, Latina, and White women. In Food and Culture: A Reader, 4th ed. Edited by Carole Counihan, Penny Van Esterik and Alice Julier. New York: Routledge, pp. 177–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vester, Katharina. 2015. A Taste of Power: Food and American Identities. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walkinshaw, Laura. 2014. The Rise of the Female Michelin Star Chef. Elite Traveler. Available online: https://www.elitetraveler.com/features/the-rise-of-the-female-michelin-star-chef (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Wall Kimmerer, Robin. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Weismantel, Mary J. 1992. Food, Gender, and Poverty in the Ecuadorian Andes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, Kyle Powys. 2015. Indigenous Food Systems, Environmental Justice, and Settler-Industrial States. In Global Food, Global Justice: Essays on Eating under Globalization. Edited by Mary C. Rawlinson and Caleb Ward. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 143–56. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, Walter, Johan Rockström, Brent Loken, Marco Springmann, Tim Lang, Sonja Vermeulen, Tara Garnett, David Tilman, Fabrice DeClerck, Amanda Wood, and et al. 2019. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. The Lancet 393: 447–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Norbert L. W., and Michelle R. Worosz. 2014. Zero Tolerance Rules in Food Safety and Quality. Food Policy 45: 112–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Wynne, and Alexis Annes. 2020. FASTing in the Mid-West?: A Theoretical Assessment of ‘Feminist Agrifoods Systems Theory’. Agriculture and Human Values 37: 371–82. Available online: http://search.proquest.com/docview/2395451120/ (accessed on 14 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Young, Iris Marion. 2012. Responsibility for Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Zah, Samantha (Navajo). 2020. Chef Maria Parra Cano. Sana Sana Foods. Sharing the medicine of ancestral plant-based foods. In Arizona Indigenous Foodways Yearbook 2020; Tempe: Glocull Urban Living Labs, pp. 20–22. Available online: https://www.tempe.gov/home/showdocument?id=85616 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

| 1 | Redlining was the discriminatory practice by lenders, backed by the federal government starting in the 1930s, whereby they would “redline” or flag communities or neighborhoods, mostly where minorities lived, and deny them mortgages due to their supposed higher risk of default. Richard Rothstein (2017) in The Color of Law (W.W. Norton and Company) details how the FHA subsidized builders creating suburbs with the requirement that no houses be sold to African-Americans. Even when redlining was explicitly outlawed in the 1960s, the underinvestment and lower property values continued. |

| 2 | This vignette is based on a true story recounted in Thompson (2019, pp. 186–87). |

| 3 | Stereotypes of Black women as powerful food providers have generated accusations that they are natural castrators of black men (Avakian and Haber 2005, p. 24). |

| 4 | https://www.tias.com/stores/mspackratz/ (accessed on 2 February 2021). This image, like all others used in this essay, is in the public domain. |

| 5 | This figure is from the U.S. Department of Labor, 22 January 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm (accessed on 2 February 2021). The percentage of female head chefs has increased from 4.7 percent in 2014 (Walkinshaw 2014). |

| 6 | “Five Female Chefs with Michelin Stars: Get Inspired by Them!” Artemis. https://www.artiemhotels.com/en/blog/chef-female-michelin-star.html (accessed on 2 February 2021). |

| 7 | https://www.foodsafetynews.com accessed 15 July 2020. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitch, S.; McGregor, J.; Mejía, G.M.; El-Sayed, S.; Spackman, C.; Vitullo, J. Gendered and Racial Injustices in American Food Systems and Cultures. Humanities 2021, 10, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10020066

Kitch S, McGregor J, Mejía GM, El-Sayed S, Spackman C, Vitullo J. Gendered and Racial Injustices in American Food Systems and Cultures. Humanities. 2021; 10(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitch, Sally, Joan McGregor, G. Mauricio Mejía, Sara El-Sayed, Christy Spackman, and Juliann Vitullo. 2021. "Gendered and Racial Injustices in American Food Systems and Cultures" Humanities 10, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10020066

APA StyleKitch, S., McGregor, J., Mejía, G. M., El-Sayed, S., Spackman, C., & Vitullo, J. (2021). Gendered and Racial Injustices in American Food Systems and Cultures. Humanities, 10(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10020066