Abstract

Only recently have scholars begun to discuss the implications of the Anthropocene for the translation of literature, introducing the new practice and study of ecotranslation. The Anthropocene—a term popularized by Paul Crutzen—describes the current epoch as one where human activity gains a large negative impact on geology and ecosystems. In light of this, an ecological approach to translation is not only useful but necessary for addressing the complex relationship between humans and the natural world. Ecotranslation can be understood as translation that recognizes and retains ecological themes from the source text. This study looks at the application of ecotranslation theory to an English translation of the German poem “so habe ich sagen gehört” by Ulrike Almut Sandig. The poem critiques preconceived notions about how humans relate to and conceptualize nature, making it an ideal source for applying ecotranslation. Through a close reading and interpretation of the poem, its ecological features are noted, then close attention is given to their translation. Comparison of the ecotranslation with an existing translation displays that an ecological approach can lead to a particular recognition and emphasis of ecological aspects. The resulting translation differs significantly from those translations lacking an ecological emphasis.

1. Introduction

Only recently have scholars begun to discuss the implications of the Anthropocene for the translation of literature, introducing a new practice and study of ecotranslation.1 The Anthropocene, a term proposed and popularized by the Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen in 2000, describes the current geological epoch as one in which human activity gains a significant, largely negative, global geological and ecological impact.2 In view of this development, literary scholars have begun to address the implications of the increasingly complex relationship between humanity and the natural world, by examining how ecological themes and ideas are expressed in literature, thus establishing the now expanding field of ecocriticism. Ecocriticism has, according to Benjamin Bühler, no authoritative definition,3 but a good starting point is Cheryll Glotfelty’s explanation: “Simply put, ecocriticism is the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment.”4 An additional important factor of ecocriticism is the presupposition that (a) nature is endangered, and (b) nature is entangled with human culture, therefore nature is inaccessible to us without a human perspective. Not only have ecocritical frameworks been adopted as a lens through which to view literature, but literary genres have emerged as well, which have a primary ecological focus—genres such as ecopoetry and climate fiction.

Recently, as a result of the expansion of ecocritical approaches to the study of literature, as well as the emergence of ecological literary genres, a theory and practice of ecotranslation has developed, which gains its major insights from ecocriticism, in particular regarding the nature of ecologically conscious language. Ecotranslation seeks to recognize such language in a source text and recreate or realize it in translation. In general terms, ecotranslation can be understood as translation from an ecological perspective, which, according to Badenes and Coisson, implies three different possible approaches:

Rereading and retranslating literary works where nature, having its own voice in the source text, was silenced in translation; translating works that present an ecological cosmovision and have not yet been translated; and translating via manipulation works that do not originally present an ecological vision with the aim of creating a new, now ecological, text.5

What little literature exists on ecotranslation emphasizes theory, yet does not extend to application.

In this study, I show the validity and impact of ecotranslation by creating an ecologically focused interpretation and translation of the poem “so habe ich sagen gehört” (so I’ve heard it said) by German author Ulrike Almut Sandig (born 1979, Nauwalde), followed by a commentary of the translation process and reflection on the result. The translation approach I implement combines aspects of Badenes and Coisson’s first and second definitions of ecotranslation. I follow the first definition in that I retranslate a previously translated poem. I overlap this with the second definition by translating a literary text that presents ecological themes and perspectives. In preparation for the ecological interpretation, first, I composed a literal translation, and analyzed the existing translation6 of the poem by Dr. Karen Leeder, which does not demonstrate a focus on the poem’s ecological aspects. The combination of these two non-ecological translations of the poem aided my implementation of an ecocritical translation approach, as they helped me to discover the deviations of such an approach. This present study and practice of ecotranslation attempts to answer the question of whether an ecological approach will impact the resulting translation. The result is positive, as it shows that an ecological approach to translation can lead to a particular recognition and emphasis on the ecological aspects of a poem and to a translation that differs significantly from translations that are lacking this emphasis.

2. Ecopoetry and Ecotranslation Theory

Zemanek and Rauscher define ecopoetry as a subcategory of nature poetry that meets one or more specific criteria regarding its approach and attitude towards nature, in not only its content but also formal representations. All these criteria follow the requirement that the worldview portrayed in the poem not be anthropocentric.7 The difference between ecopoetry and forms of nature poetry as seen in other periods of literary history such as Romanticism, is, according to Axel Goodbody, that in the latter, humanity held the central position in their own perspective of the world, and human emotion was projected on to the depicted natural landscape.8 Yet, an ecotranslation of a Romantic poem could perhaps enhance its biocentric perspective. Goodbody proposes that ecopoetics in the Anthropocene need to be a practice of poetry that is biocentric, assigning appropriate interest to all things and considering the simultaneous physical existence of the human and non-human. Lynn Keller complicates this definition with her statement that in composing ecopoetry, “formal or linguistic experimentalism is a key resource…”9 Accordingly, in ecotranslation the issue arises of how one might recognize and translate these ecological components of poetry.

In their essay, Badenes and Coisson claim that, when ecological perspectives and translation are combined, ecotranslation is created, which involves the intersection of not only different languages as in any translation, but also of cultural differences in ecological concern and thought.10 According to Michael Cronin’s Eco-translation: Translation and Ecology in the Age of the Anthropocene, the separation of humanities, social sciences, and natural, physical sciences is not sustainable. This is so, he claims, since it is no longer possible to ignore the relationship between the non-human and the human. He proposes that the relationship between non-human nature and humanity has changed drastically through industry, technology, and agriculture. This change cannot therefore be left unaddressed. He suggests that if a new perspective is required of humanity, this will affect all of human activity, including translation.11 From the insights of these authors, two specific challenges in ecotranslation emerge. The first lies in the attempt to rethink how translation should be approached considering the current ecological crisis. As mentioned in the introduction, in light of the Anthropocene, the weight of finding a solution to environmental issues that result from an anthropocentric perspective on nature is in part on the shoulders of the humanities, which includes the translation of literary texts. The second challenge lies in how cultural ecological knowledge and concern can be transferred interculturally in literary texts.

As mentioned in the introduction, according to Badenes and Coisson, who focus on literary translation, ecotranslation can be approached in three different ways: retranslating literature where nature had a voice in the original text that was previously silenced in its translation; translating, for the first time, literary texts that present ecological themes and perspectives; and translating, through manipulation, non-ecological texts into ecological ones.12 In the first approach to ecotranslation, there is an existing translation of a text, where the source text portrays nature in a way that one can perceive as ecological. The authors suggest that, when a critical analysis of an existing translation of such a text reveals that the translation has silenced the way it represents nature, a retranslation can be produced that is truer to the portrayal of nature in the source text. The second version of ecotranslation, the very first translation of a literary text that is perceived as ecological, is similar to the first, since both come to the source text with an ecological worldview in mind. Both approaches affirm the aspects of ecology already present in a source text. The third, and final version of ecotranslation is critical, like the first, but the criticism is not directed against an existing translation, but against the text to be translated. The authors promote the manipulation of what they perceive as a nonecological literary text in order to transform it, via translation, into one that is ecological. This transformation, however, is in opposition to Michael Scott Doyle who says of translation that it “must demonstrate fidelity toward what is given in the source-language text.”13 Rather than to manipulate a text via translation, Doyle suggests that translators remain faithful to the text, though he acknowledges the challenges of this task.

In their essay, Badenes and Coisson explore and illustrate all three of their proposed versions of ecotranslation through case studies. They examine rereading and retranslation through an analysis of an excerpt of a translation of Katherine Mansfield’s short story “At the Bay” (1912),14 which is most relevant to this study since there is an existing English translation of “so habe ich sagen gehört.” Badenes and Coisson critique the translation of the Mansfield text for ignoring the voice of nature expressed in the original.15 They focus on word choice, especially on the effects of the connotations that words carry for readers, particularly words’ connection to human agency. One example is the translation of the word “paddock.” In Mansfield’s original, it appears in the sentence, “The sandy road was gone and the paddocks and the bungalows the other side of it.”16 All of the objects mentioned in this sentence represent a manmade object, which nature, in this case mist, obstructs from view.17 The translation converts “paddock” into the Spanish “pastos” (grass), which, according to Badenes and Coisson, diminishes the prevalence of nature in the text. The English “paddock” is a manmade fenced-in field, and in contrast the word “grass” is natural and refers to a grassy field or meadow. Nature in the source text makes manmade constructions vanish, but in this translation natural landforms (grass) replace the artificial construction (paddock), taking away power from the image that nature, namely the mist, obstructs the manmade paddock.18

A general translation practice creates a new text in the target language, on the basis of a source text in the original language. In any approach to translation, Maria Tymoczko explains that translators must make choices; they cannot capture all aspects of a source text, and their choices establish a place focus. According to Tymoczko, translators must make choices about what to translate and what to silence.19 Following Tymoczko’s perspective on translation, a translation which aims to capture ecological aspects establishes a place of focus on ecology. Concurrently, such a translation attempts to minimize losses of other aspects in the source text such as tone and musicality. If ecological themes and structures are prominent in the source text, their retention is valuable in translation; thus, the choice to make ecology a place of focus is justified.

3. An Ecological Interpretation

The poem ‘so habe ich sagen gehört’ by Ulrike Almut Sandig was first published in the collection Dickicht (2011).20 Additionally, it has appeared in audio format on the album Märzwald (2011), a collaboration by the poet Sandig and the songwriter and singer Marlen Pelny.21 The anthology Lyrik im Anthropozän (2016), edited by Anja Bayer and Daniela Seel,22 features the poem as well, which suggests that it can be understood, and that the editors and the author thought it could fit, within the context of poetry concerned with ecological themes, in particular with the notion of the Anthropocene. The title of the volume, Lyrik im Anthropozän, proposes that the poetry in it contains the sentiment that all of the natural world has been touched, and subsequently harmed by humanity, and that poetry is potentially changed by the Anthropocene. The poetry in the anthology is accompanied by three critical essays, including an essay by Goodbody that develops a concept of ecological poetry in contrast to earlier forms of nature poetry. My examination of Sandig’s “so habe sagen gehört” focuses on how specific structural, formal, and thematic elements reflect the poem’s ecological concerns.

Loss is the main ecological theme in the poem. Its central idea is that the speaker “hab sagen gehört, es gäb einen Ort/ für alle verschwundenen Dinge” (heard said, there would be a location/ for all vanished things),23 which is “auf keiner gültigen Karte verzeichnet” (not listed on any valid map), and they are reiterating what they have heard to the reader. The speaker explains that the vanished items are perhaps located in the middle of the silver fir forest, but this location is only a rumor. The structure of the poem is reminiscent of a list—a list of these vanished items, which include apples, gods, clowns, the character of a radio drama, cities, and the names of destructed villages. While the location is ambiguous, the loss described is not fictitious but real. Seen through an ecological lens, one could say that this list it is a taxonomy of items. A taxonomy is a human-created classification of organisms, which can be defined as a practice of recognizing, naming, and ordering units of biological classification.24 A focus on names in the poem is reminiscent of taxonomy and biological nomenclature. The poem organizes a list of natural and cultural loss; and itself acts as a structure which Sandig uses to order the loss of a variety of different items. This taxonomical likeness imbricates the human and non-human, as well as nature and culture. This relation suggests a natureculture, to use Donna Haraway’s term, which synthesizes nature and culture, maintaining an inseparability.25

The poem consists of six stanzas, including five couplets, and a concluding tercet. Within the final tercet of the poem is the bolded phrase “so habe ich sagen gehört” (so I have heard it said), which can be read as its title or, perhaps more accurately, an emphasis on the lack of a title. A lack of a traditional title placement at the top of poem is a common occurrence throughout Dickicht. This stylistic choice in the case of this specific poem functions as a textual visualization of the discussed hidden location, which is the rumor itself— speaking about what has been lost, perhaps in an attempt to find it again. In the same way that the location of the vanished items is in the middle of the forest, the title has vanished from its traditional placement and is “hidden” in the last stanza of the poem. In the same way the title could well be the name of the location, which is the overall focus of the poem.

Sandig expands the definition of the Anthropocene to include not only how human actions effect nature, but also how our perception and understanding of nature and humanity must recognize them as mutual extensions of each other. Through the selection of items lost in the poem, Sandig clarifies the entanglement of nature and humanity. She shows in this poem the anthropogenic impact on the environment in the reduction of biodiversity in apples—but she thereby also points to the fact that humans have created this biodiversity in the first place through breeding different varieties. The first mentioned vanished item, the ‘Sorten von Äpfeln’ (varieties of apples) are a form of domesticated nature that originated in Asia. In Germany, there are between 2000 and 5000 varieties of apples.26 Yet, due to commercial agriculture only a few of these varieties are cultivated today, and diversity of apples has decreased as a result. Some of the old varieties have gone extinct like the Deutsch Goldpepping and the Holsteiner Rosenhäger.27 Apples are natural, and at the same time they are one of the most important fruits in culture.28 All apple varieties are the result of selective cultivation, they are a manmade alteration of nature, hence their reference in the poem creates further imbrication between biodiversity loss and cultural loss. Not only are apples deeply connected to humans via agricultural history, but they also hold significant symbolism in cultural tradition. One of the most well-known apples is the biblical forbidden one eaten by Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Apples have represented love, health, temptation, death, femininity and more.29 They are an excellent example of what nature in the Anthropocene looks like, an anthropogenic form of nature that cannot be separated from humanity; therefore, they elude any categorization as “other.”

‘Die Götter’ (the gods) are the second vanished item listed in the poem, bringing out spiritual connotations, which in a variety of belief systems are deeply tied to nature, even making nature the object of worship. Unspecified as these gods are, the assumption can be made, considering the modern German literary tradition, that they could refer perhaps to Greek gods. For the German lyric that arose in the late 18th century, often referred to the Greek gods as simply “gods,” such as in Hölderlin’s hymn Germania or Schiller’s poem Die Götter Griechenlands. Niklaus Peter suggests that in contemporary poets’ work there is rapprochement between poetry and religious thought.30 Hence, it makes sense that on the one hand the poem speaks of the loss of the gods, yet on the other it formulates current relations of poetry and religion. According to Adorno and Horkheimer, gods are traditionally not identical to natural elements but signify them; they embody nature as a universal power.31 The authors believe that diminishing nature-gods plays a role in the Enlightenment, a part of the process of humans attempting to dominate and control nature in order to overcome their fear of nature. Neither the ancient perspective of appeasing nature-gods to avoid natural disaster, nor the Enlightenment’s promotion of installing humanity over nature, are biocentric. By bringing up the loss of gods, Sandig signifies a lost connection between humanity and nature, a connection reflected in Sandig’s poem which increases the theme of the interconnection of humans and nature. Movement away from this anthropocentric way of thought liberates possibilities for biocentric ones. Allusion to lost gods is similar to the lost varieties of apples, one of deep historical and cultural connection between humans and nature. This loss is ambivalent as it does mourn a loss of connection with nature but gains in independence and rationality.

The next item listed is clowns. The clown has a long history and can be dated all the way back to the Old Kingdom 5th dynasty in Egypt;32 they can be defined as a comic entertainer who uses humor, often of the slapstick variety, to entertain their audience. Clowns represent humor, a distinct aspect of human psychology. As a result, clowns fulfill a cultural psychological need in society.33 Despite their long history, according to some, the clown is now dead,34 which makes their place with the other vanished items coherent. If clowns represented a certain aspect of humanity’s humor and in turn psychology, but they no longer exist, then the loss of them indicates loss of a part of humanity. Therefore, their inclusion in this poem distinguishes that the poem speaks beyond pure non-human or biodiversity loss and into loss of culture and human nature.

Braunkohledörfer (brown coal villages) are the final vanished items listed. Braunkohledörfer are a special, particularly German phenomenon,35 and hence a localized environmental issue. They are villages that either will be or have been destroyed since they are atop land that has been selected for the mining of brown coal which lies on the surface of the earth.

In contrast to these physical items, the names of cities are listed. All of the cities still exist today, yet their names have been changed. For example, today Karl-Marx-Stadt readopted its previous name Chemnitz, Constantinople is now Istanbul, Benares is today called Varanasi, and Bombay is Mumbai. Each of these cities have particular cultural connotations. For example, in Constantinople, Zeno (474–491 AD) saw the Imperial Library destroyed in a fire and he then rebuilt it with copies of works gathered from other libraries.36 A loss of knowledge stored in books is another cultural loss that Sandig implicitly alludes to by mentioning the lost name Constantinople, and connects to biodiversity loss. The names Benares and Bombay were coined by British colonizers in the 19th century. Like the gods previously mentioned, the cities have undergone a name change; Sandig lists their old names, in line with the lamentation on loss throughout the poem. However, their inclusion creates nuance, because the loss of colonial names is not something to be mourned. Names as well as cities are anthropic, yet they are also ecological here in that they show that human activity destroys not only nature, but places of human cultural significance, too. Karl-Marx-Stadt’s mention is, in addition to Braunkohledörfer, a further grounding of the poem in a German context. This reference also connects to the map mentioned in the poem, as the GDR is no longer listed on “any valid map.” Karl-Marx-Stadt was an industrial city in the GDR and suffered sulfur pollution from the burning of domestic brown coal,37 a correlation to Braunkohledörfer.

In the last stanza, a forest is mentioned where all the listed vanished items are rumored to be; the speaker explains that this location is not on any map. Yet, what is a map? It is a guide—an overview of the earth. At the same time, a map is also a riddle to be deciphered and understood by its own key.38 The location of the lost items might not be on any map, but it is being discussed in the poem. The poem itself can thus perhaps be understood as a map in its own right: a guiding overview of the loss of both human and non-human phenomena and their hidden location which awaits decipherment. Like a map, it connects places together, shows space between them, and specifically names them. Maps visually or symbolically represent an area often times of the earth or sea. They combine roads with fields and forests, cities with rivers and mountains, the human and non-human. Likewise, the poem displays this combination of human and non-human.

At the end of the poem, the speaker explains that the location of the “things” lost may be in the middle of the silver fir forest. In this forest, all sound waves are “geschluckt” (swallowed), therefore implying that the apples, gods, cities, might be lost forever, once they reach this location. Such an implication connects to the repeated plosive sounds, which cause airflow obstruction, making the reader “swallow” the words as they are read. This emphasizes further the concept of language loss throughout the poem. The body’s involvement communicates the inherent physicality in the nature of speech.

Inseparable to ecological loss is loss of culture, and their interconnection is prominent in the poem. Rather than conveying nostalgia, the poem addresses the complexity of this loss. For example, the loss of apple varieties may appear at first nostalgic for a time when more varieties existed, but there is also address of the loss of colonial names and domination of nature which are not to be lamented. Additionally, the location of the lost items in a specifically “silver fir forest” is ecological as the silver firs have particular resiliency in the face of global warming.39 The poem suggests that nature is both impacted and conceptualized by humans. Therefore, while remaining natural, in that nature eludes complete control by humans, nature holds important cultural significance.

By reason of its lament over the loss of vanished items, the poem can be categorized as an elegy.40 It does not adhere strictly to any one poetic form, however, but combines characteristics of distiches and spondee. The vanished items consist of a variety of objects, including, in addition to the varieties of apples, places, persons, and names. The items mentioned can be divided into two categories: items that have vanished, and the old or forgotten names of those that still exist. The items that have disappeared include various apple varieties, gods, clowns, names of Braunkohledörfer—brown coal villages that have been destroyed, and various cities that still exist.

Some of the items mentioned in the poem come from nature, like the apples and the silver fir forest, others are locations, like the cities, others still are mythical or fictitious persons like the clowns and the gods, and the gute Gott von Manhattan (good God of Manhattan), which refers to Ingeborg Bachmann’s eponymous radio drama. In the drama, the “gute Gott von Manhattan” (good God of Manhattan) blows up two young lovers, resulting in one of the lover’s death, because the God views their all-consuming love as unnatural.41 Thus, despite his name, the good God of Manhattan is far from good. This brings forward the concept that some of the loss depicted is not to be lamented. For example, the view of the human-nature relationship informed by Enlightenment thought, as one of domination, is not lamented, the loss of a megalomaniacal love-loathing god is also not.

Since all of its lines are about the same length, the poem appears symmetrical, which creates a sense of order. Both lines in the first distich have ten syllables. All of the following two-line stanzas have ten syllables in the first line, and nine in the second. In the last stanza, the first two lines have nine syllables and the last one has eleven. In contrast to this regular syllabic construction, the content of the poem seems incongruous, upon first reading: it is not clear what apples, gods, clowns, cities, and villages have in common. The map mentioned near the end, on which the vanished items cannot be located, suggests that the structure itself may be understood as a map but one that can, paradoxically, help recuperate what has been lost, at least in words. The poem talks about the unknown location and what specific items might be there. Likewise, a map displays to its readers a landscape and helps bring order to its various parts. Similar to how taxonomy creates classification and order, a map does the same. The clear emphasis on form in the poem and its internal reference to structures, I read as a reflection of the way these structures, such as taxonomy, maps and even poems are conduits through which humans’ awareness of non-humans is moderated.

The speaker of the poem repeats information that they have only “heard said.” Though the poem speaks to loss of biodiversity by mentioning the loss of variety of apples, the speaker and their unknown informant never address the reader by saying “you.” Therefore, the poem does not explicitly demand a response to this environmental concern from the reader. This feature distinguishes Sandig’s poem from ecological themed poetry from the 1960s through the 1970s, which is often accusatory in tone and contains calls to action against environmental destruction. This situates the poem in the context of modern ecopoetry, which does not require explicit calls to action, but instead articulates ecological thought.42

The phrase “hab sagen gehört” repeats three times throughout the poem. This phrasal repetition is reminiscent of a refrain in a song, but also of a legend, fable or fairytale. The phrase “hab sagen gehört” (heard said) recalls the well-known “es war einmal” (once upon a time) popularized by fairytales such as Schneewittchen from the Brothers Grimm. Introductory phrases such as this function as narrative signals to the reader; “es war einmal” signals to the reader that a fictitious and often fantastical story will follow.43 “Hab sagen gehört” provides a similar function, by giving a narrative signal that second-hand information will promptly ensue. It differs through the addition of ‘I’ which personalizes the statement. The use of this lyrical ‘I’ recalls the modern 18th century traditional poetic technique of evoking empathy from the readers by allowing them to identify with the lyrical ‘I’ and by emphasizing human individuality. Additionally, the use of the word “sagen” creates a connection to “die Sage” (Legend). This fairytale reminiscence connects well with the silver fir forest of the poem in which the vanished things are said to be, perhaps, located, as forests play an important role in many fairytales.44 According to Jack Zipes, the fairytale “forest is always large, immense, great, and mysterious. No one ever gains power over the forest, but the forest possesses the power to change lives and alter destinies.”45

Sandig’s poem does not explicitly make a request to the reader, it only relays information to them. This choice of relaying information through the first-person speaker in the form of a rumor that recalls fairytales or legends, emphasizes that the loss thematized in the poem has a narrative structure. The reader knows of the vanished items and the hidden location only through the speaker. This suggests that we do not have first-hand information about what disappears in biodiversity and other, cultural loss, and it therefore remains somewhat vague; e.g., we learn only of “varieties of apples,” not the names of such varieties. This vagueness creates the impression that the loss has become so far removed from human culture that its existence is intangible, like a fairytale. It becomes almost fictional, something in the far past that is now reflected upon.

In addition to the phrasal repetition, sounds are also repeated such as, “rt” in words like “gehört”, “Ort”, “Sorten” and “Karte.” And the “g” sound in words like “gehört”, “gäb”, “Götter”, “guten”, “Gott”, and “gültigen.” This pattern of sounds is distinguished by the fact that they are all plosive, meaning that their production blocks airflow in the throat. These sounds satisfy the line ‘jeder Schallwelle schluckt’ (swallows every sound wave), since the reader almost ‘swallows’ their own words as they read the poem, by uttering (aloud or silently) the plosive sounds; the poem as a whole is akin to an onomatopoeia by phonetically suggesting what it describes.

Sandig’s poem “so habe ich sagen gehört” displays ecological features, following the definition by Zemanek and Rauscher. They define ecopoetry as a subcategory of nature poetry that meets one or more of the following criteria: (1) a thematic treatment of nature; (2) presentation of nature as a complex ecosystem; (3) an eco- or biocentric worldview; (4) the articulation of environmental concerns; or (5) the formal representation of ecological principles like interdependence and cyclic structures.46 Sandig’s poem contains three of these features: a thematic treatment of nature, articulation of environmental concerns, and representation of interdependence and cyclic structures. The motif of a forest and the mention of apples are thematic treatments of nature; biodiversity loss and the loss of villages to brown coal mining present environmental concerns; and a list-like structure that mimics taxonomy represents the ecological principles of interconnection and coexistence. The taxonomy in the poem lists both nature and culture, which maintains the impression of interconnection. There is specific focus on not only how humans conceptualize nature in the poem, and also that they created this interconnection between human culture and nature. These and other features discussed above plant it firmly in the genre of ecopoetry.47

4. Translation Commentary: Literal, Existing, and Ecological Translations

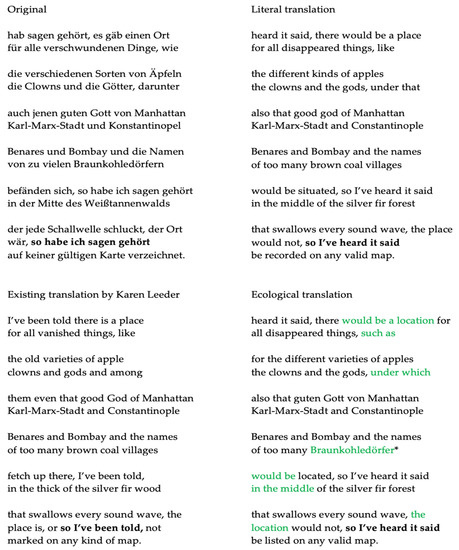

Dr. Karen Leeder’s translation of Sandig’s “so habe ich sagen gehört,” appears not to contain an ecological focus, seeming instead to emphasize word-for-word equivalents and poetic language. As Tymoczko said on translation, a translator must make choices, but when one choice is made another is inherently neglected.48 All ecologically relevant words in my ecotranslation which differ from the non-ecotranslations are highlighted by green text in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Side-by-side comparison of the literal, existing, and ecological translations along with the original poem.49

In preparation for an ecological translation of Sandig’s poem, I analyzed the existing translation by Leeder and completed an original literal translation of the poem. All the translations and the original poem are in Figure 1 for reference. By first completing a literal translation, the places in the poem where the literal translation fails to communicate the ecological elements of the original poem in a satisfying manner I can more easily recognize. This helps guide me through the ecological translation. The existing translation by Leeder displays several characteristics of a literal approach; but in a few cases I find she has also employed a freer translation. I will discuss a selection of Leeder’s translation choices along with their effects on the possibilities of interpreting the poem, in particular with respect to its ecological elements. Leeder’s translation of “so habe ich sagen gehört” was published in her translation of Sandig’s collection Dickicht in which the poem was originally published.

The literal translation I prepared for this study aims to produce a text that most accurately represents each individual word in the original poem within its immediate context. Accurately in this case means that one of the first options listed in a current, reputable dictionary is selected for each individual word in the poem.50 If the word could have multiple valid meanings, I examined the context of the word to determine how it is most likely to be understood so that I might select the closest corresponding English translation. The focus in my use of this approach is not on the overall meaning or essence of the poem but on word for word equivalence. My main goal is to represent the poem’s semantical and syntactical features in English. In this translation, the retention of ecological aspects and structural features is not of concern to me.

Leeder’s choice to translate the variations of the phrase “habe ich sagen gehört” as “I’ve been told” in English places more agency on the unknown speaker of the poem than the literal translation, “have heard it said” suggests. When an individual is “told” something, it indicates that whoever spoke to them was deliberate in this communication. However, such a sentiment is not conveyed by the original German “habe sagen gehört.” While both “tell” and “say” are direct translations of “sagen,” “tell” requires the sentence to be switched to a passive voice. This effect distances the reader even further from the unknown figure speaking. This distancing is both prominent and significant, as shown in the above interpretation of the poem. Leeder’s translation, by contrast, not only brings attention to the speaker of the poem by making them the emphasis of the passive phrase, but also by including the pronoun “I” in the first repetition of the phrase when it is excluded in the original.

The original poem employs the German subjunctive II mood throughout. I translate this literally in English as “would be” to maintain the sentiment of doubt conveyed in the original by the usage of this mood. Leeder chooses to use the indicative mood which does not communicate doubt or uncertainty but rather statement of fact. Due to this, her translation leaves no doubt about whether the location exists.

In the third line of the poem, Leeder inserts the word “old” and changes the German dative plural of the word apple, “Äpfeln” to the singular, “apple,” while leaving “Sorten” translated as “varieties,” as plural. Sandig speaks of general “things” in this poem with almost no adjectives or descriptions, thus the addition of “old” creates a specification non-existent in the German text. The apples are the first vanished item mentioned, and their disappearance is not in connection with their age. The items are lost, not old, not rotten, not decayed, not anything besides vanished. Similarly, the use of the of the singular “apple” emphasizes a particularity to the lost items in Leeder’s translation.

Finally, there is an instance where I detect Leeder’s translation choices are quite free, meaning that the way in which she has rendered a specific phrase diverges significantly from the original poem. The instance where Leeder uses this strategy is the phrase “in der Mitte.”

- befänden sich, so habe ich sagen gehört

- in der Mitte des Weißtannenwalds

- (fetch up there, I’ve been told,

- in the thick of the silver fir wood)

“in der Mitte,” is rendered “in the thick of.” This expression refers back to the English title of the collection Thick of It, which was translated by Leeder who likely also chose this translation of the German title, Dickicht, which means “Thicket.” Yet, the German “in der Mitte” does not refer to Dickicht. “In the thick of” means the most intense or violent part of something.51 Through the usage of a more direct equivalent, “in the middle,” I retain the specificity of place in “in der Mitte.”

The first word of ecological importance in the poem is “Ort.” It can be translated as “place”, “spot”, or “location.” A place is defined as a “physical environment” or “physical surroundings.” This definition is more general than the specificity that I observe the original “Ort” suggests. The poem is entirely about this “place,” including a number of lost items to be found there, and rumors of where the place is. Thus, while “place” is the most commonly used German translation of “Ort,” it lacks specificity, since a place is a physical space with no defined borders or limits. A term that appears to better preserve the ecological aspect of “Ort” in Sandig’s poem is “location” because it signifies a clearly defined and limited area. The specificity of location is fitting since near the end of the poem, one learns that the lost things are perhaps situated “in the middle of the silver fir forest,” which is a particular location. This results in the statement in the last line that the location (Ort) cannot be found on any map, which is even more jarring since specific locations are marked on maps. If the poem can be read as a map, as I suggest in the interpretation, it follows that it would provide clarity and specificity as maps do. It would maybe even perform the opposite of what it says within itself, in that it leads to the lost things or provides guidance to those seeking this location.

The list-like structure of the poem with its taxonomical connotation is expressed in the second and fourth lines of the poem by the German words “wie” and “darunter.” Leeder translates these as “like” and “among” respectively, both of which are equivalents of the German words and appropriate. The use of “among” specifically gives the impression of inclusion in a grouping of items as opposed to a list categorization. These choices, however, cannot capture the list-like structure of the source text in the way that the original German does. Therefore, I chose the less intuitive translations “such as” and “under which,” respectively, in order to highlight the taxonomical structure. By not only focusing on the meaning of individual words but also the context of these words and how they fit into the overall structure and interpretation of the poem, I kept open the possibility to discover and retain additional layers of the poem’s ecological associations, in this case the reference to the classification of living organisms. While “like” is the most literal translation of “wie” in the context of this poem, this choice does not signal the beginning of the list-like structure of the original poem. “Such as” signals to the reader that a list will follow. By translating “darunter” in the fourth line as “among,” the connotation of a list following below is lost. In contrast to this, “under which” communicates a hierarchy or categorization of items.

The most challenging word to translate in the poem is “Braunkohledörfern” (written in the dative case, “Namen von + Dative case,” “the names of”) in line eight; one could translate it word for word into “brown coal villages” as Leeder does in the existing translation. However, the fact that is expressed by the German noun is villages that have been destroyed because they are atop land to be mined. For the average English speaker, this long-standing, harmful side-effect of lignite mining in Germany is not common knowledge, and therefore the association for the common reader of “brown coal villages” is rural towns where people who work in the mining industry live, not a town that has been annihilated to make space for a coal mine. While it is possible to translate the term as “villages destroyed for mining,” this sounds unpoetic. This phrase would also make the line much longer than the other ones, creating a distraction away from the overall meaning of the poem. How I render the word “Braunkohledörfer” in translation has an impact on the ecological emphasis of the poem. For all these reasons, I left “Braunkohledörfer” untranslated and included a footnote explaining and defining it, rather than to risk a reader misunderstanding this cultural occurrence. This is one strategy for dealing with culturally specific words, the culturally untranslatable word is left in the source language and an explanation is inserted.52 In defense of leaving words in original language, Cronin says: “The untranslatable becomes a way of thinking about the specificity of languages and cultures, a call to attend to the singularity of written expression in particular places at particular times.”53 Since the poem is claiming that too many of the names of these villages have been destroyed, not retaining this term would further erase the names connected to it. My aim in leaving this term untranslated is to respect its place sensitivity and ensure that it is understandable by providing a footnote—the only one in the translation.

5. Conclusions

In the Anthropocene, literary works will continue to be produced that address crucial environmental and ecological themes. As these themes are global, they should be presented in multiple languages. This creates a need for an ecological approach to translation. My present study shows in this rendition of “so habe ich sagen gehört” that ecotranslation is a possible and meaningful mode of translation that bears a clear difference to a practice of translation without this particular focus. Through an ecological translation, the poem “so habe ich sagen gehört” can be read and understood by English speakers, not only as a piece of literature, but one that clearly addresses important themes in ecology, some of which are specifically German and might without such a translation remain unknown to English speakers. Sandig’s poem is relevant globally in that it addresses questions of how humans and have related to nature previously, and thus, brings forth further questions as to how humanity can move forward into alternative ways of relating to the natural world.

My study shows how ecotranslation is applied; however, it is only one example. There are many extant challenges and questions to be explored regarding ecocriticism and translation. For example, what is ecological language definitively? Perhaps in the Anthropocene we will reach a point of interconnected relation with nature where differentiating between ecological and non-ecological literature will be impossible. Regarding translation, how biocentric can or should an ecotranslation be? As the lines continue to blur between nature and humans in the Anthropocene, a need to answer such questions as well as continued application of ecotranslation will only increase.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank May Mergenthaler for her insightful comments, guidance, and continual support of this project. Additionally, I warmly thank Katra Byram for her helpful feedback and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Badenes, Guillermo, and Josefina Coisson. 2015. Ecotranslation: A Journey into the Wild through the Road Less Traveled. European Scientific Journal 11: 356–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, Michael. 2010. The Clown: An Archetypal Self-Journey. Jung Journal 4: 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, Anja, and Daniela Seel, eds. 2016. Naturlyrik-Umweltlyrik-Lyrik Im Anthropozän: Herausforderungen, Kontinuitäten Und Unterschiede. In All Dies Hier, Majestät, Ist Deins: Lyrik Im Anthropozän: Anthologie, 1. Auflage. Reihe Lyrik (Idstein, Germany), Band 48. Berlin: Kookbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Braak, Ivo, and Martin Neubauer. 2007. Poetik in Stichworten: Literaturwissenschaftliche Grundbegriffe; eine Einführung. 8., überarb. und erw. Aufl. Stuttgart: Borntraeger. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, Benjamin. 2016. Ecocriticism: Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen, Martin L. 1995. Cladistic Taxonomy, Phylogenetic Systematics, and Evolutionary Ranking. Systematic Biology 44: 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornille, Amandine, Pierre Gladieux, Marinus J. M. Smulders, Isabel Roldán-Ruiz, François Laurens, Bruno Le Cam, Anush Nersesyan, Joanne Clavel, Marina Olonova, Laurence Feugey, and et al. 2012. New Insight into the History of Domesticated Apple: Secondary Contribution of the European Wild Apple to the Genome of Cultivated Varieties. PLoS Genetics 8: e1002703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, Michael. 2017. Eco-Translation: Translation and Ecology in the Age of the Anthropocene. New Perspective in Translation and Interpreting Studies. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, Paul, and Eugene Stoermer. 2000. Anthropocene. Global Change Newsletter 41: 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Welle. 2016. Can Germany’s Heirloom Apple Varieties Be Saved? DW, January 22. DW.COM. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/can-germanys-heirloom-apple-varieties-be-saved/a-18997147 (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Deutschland, Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik. 2003. Gerade auf LeMO gesehen: LeMO Kapitel: Umweltzerstörung. Available online: https://www.hdg.de/lemo/kapitel/geteiltes-deutschland-krisenmanagement/niedergang-der-ddr/umweltzerstoerung.html (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Doyle, Michale Scott. 2008. Translation and the Space between: Operative Parameters of an Enterprise. In Translation: Theory and Practice, Tension and Interdependence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Pub. Co., pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Glotfelty, Cheryll. 1996. Introduction: Literary Studies in an Age of Environmental Crisis. In The Ecocriticism Reader Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Atlanta: University of Georgia Press, p. xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Goodbody, Axel. 2016. Naturlyrik-Umweltlyrik-Lyrik im Anthropozän. In All dies hier, Majestät, ist deins: Lyrik in Anthropozän. Edited by Anja Bayer and Daniela Seel. Berlin: Kookbooks, pp. 287–304. [Google Scholar]

- Grözinger, Albrecht, Andreas Mauz, and Adrian Portmann, eds. 2009. Carte Blanche von Niklaus Peter. In Religion Und Gegenwartsliteratur: Spielarten Einer Liaison. Interpretation Interdisziplinär, Bd. 6. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, pp. 177–85. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Paradigm 8. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Michael H. 1999. History of Libraries in the Western World. Lanham and London: Scarecrow. Available online: http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9780810877153 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Horkheimer, Max, Theodor W. Adorno, and Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. 2002. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Christian, and Edward H. Dahl. 2006. The Sovereign Map: Theoretical Approaches in Cartography throughout History, English-Language ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Lynn. 2017. Recomposing Ecopoetics: North American Poetry of the Self-Conscious Anthropocene. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Knauss, Stefanie. 2015. The Journey of a Symbol through Western Imaginaries. The Curious Case of the Apple. In Religion in Cultural Imaginary. Edited by Daria Pezzoli-Olgiati. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, Anthony. 2018. ‘Once Upon a Time’ and Other Formulaic Folktale Flourishes. The Paris Review (blog). May 23. Available online: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/05/23/once-upon-a-time-and-other-formulaic-folktale-flourishes/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Mansfield, Katherine. 1922. At the Bay. In The Garden Party, and Other Stories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster.com. 2020. Available online: https://merriam-webster.com (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Pons.com. 2020. Available online: https://en.pons.com/translate (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Red Pepper. 2016. From Russia to Colombia, the Villages Destroyed by Britain’s Coal Addiction. Available online: https://www.redpepper.org.uk/from-russia-to-colombia-the-villages-destroyed-by-britains-coal-addiction/ (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Sandig, Ulrike A. 2011. so habe ich sagen gehört. In Dickicht: Gedichte. 1. Aufl. Frankfurt am Main: Schöffling & Co., p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Sandig, Ulrike A., and Karen J. Leeder. 2018. so I’ve been told. In Thick of It. London and New York: Seagull Books, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Sandig, Ulrike Almut, and Marlen Pelny. 2011. Märzwald. CD. Frankfurt: Schöffling & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tymoczko, Maria. 2006. Translation: Ethics, Ideology, Action. The Massachusetts Review 47: 442–61. [Google Scholar]

- Utami, S. K. Nur. 2014. Cultural Untranslatability: A Study on the Rainbow Troops. Celt: A Journal of Culture, English Language Teaching & Literature 14: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasse, Yann, Alessandra Bottero, Martine Rebetez, Marco Conedera, Sabine Augustin, Peter Brang, and Willy Tinner. 2019. What Is the Potential of Silver Fir to Thrive under Warmer and Drier Climate? European Journal of Forest Research 138: 547–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomologen Verein. 2013. Suchliste Verschollener Historischer Obstsorten. Available online: https://obstsortenerhalt.de/obstart/verschollene (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Xlibris. 2019. Interpretation ‘Der Gute Gott von Manhattan’ von Ingeborg Bachmann. Available online: https://www.xlibris.de/Autoren/Bachmann/Werke/Der%20gute%20Gott%20von%20Manhattan (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Zemanek, Evi, and Anna Rauscher. 2018. Das Ökologische Potenzial Der Naturlyrik. In Ökologische Genres: Naturästhetik-Umweltethik-Wissenspoetik. Umwelt Und Gesellschaft, Band 16. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zipes, Jack. 1987. The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World. Germanic Review 62: 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 360). |

| 2 | (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000). |

| 3 | (Bühler 2016, p. 28). |

| 4 | (Glotfelty 1996, p. xviii). |

| 5 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 360). |

| 6 | (Sandig and Leeder 2018, p. 9). |

| 7 | (Zemanek and Rauscher 2018, p. 97). |

| 8 | (Goodbody 2016, p. 299). |

| 9 | (Keller 2017, p. 26). |

| 10 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 357). |

| 11 | (Cronin 2017, p. 17). |

| 12 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 360). |

| 13 | (Doyle 2008, p. 14). |

| 14 | (Mansfield 1922, pp. 1–58) |

| 15 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 361). |

| 16 | Ibid. |

| 17 | Ibid. |

| 18 | (Badenes and Coisson 2015, p. 362). |

| 19 | (Tymoczko 2006, p. 453). |

| 20 | (Sandig 2011, p. 13). |

| 21 | (Sandig and Pelny 2011). |

| 22 | (Bayer and Seel 2016). |

| 23 | Here and below, the translations provided in brackets are literal translations. |

| 24 | (Christoffersen 1995). |

| 25 | (Haraway 2003, p. 3). |

| 26 | (Deutsche Welle 2016). |

| 27 | (Pomologen Verein 2013). |

| 28 | (Cornille et al. 2012). |

| 29 | (Knauss 2015). |

| 30 | (Grözinger et al. 2009, p. 178). |

| 31 | (Horkheimer et al. 2002, pp. 5, 12). |

| 32 | (Bala 2010, p. 50). |

| 33 | Ibid. |

| 34 | (Bala 2010, p. 60). |

| 35 | There are other examples of the destruction of villages due to mining in both Russia and Columbia. (Red Pepper 2016). |

| 36 | (Harris 1999, p. 72). |

| 37 | In the 1970s and 1980s within Europe, the GDR had the highest sulfur dioxide pollution. (Deutschland, Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Stiftung Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik 2003). |

| 38 | (Jacob and Dahl 2006, p. xvii). |

| 39 | (Vitasse et al. 2019). |

| 40 | (Braak and Neubauer 2007, pp. 182–83). |

| 41 | (Xlibris 2019). |

| 42 | (Zemanek and Rauscher 2018, p. 97). |

| 43 | (Madrid 2018). |

| 44 | (Zipes 1987, p. 66). |

| 45 | Ibid. |

| 46 | (Zemanek and Rauscher 2018, p. 97). |

| 47 | Ibid. |

| 48 | (Tymoczko 2006, p. 453). |

| 49 | * Braunkohledörfer are villages that are destroyed for the purpose of mining the coal beneath them. |

| 50 | (PONS 2020). All German word English equivalents are from the PONS Online German-English Dictionary. |

| 51 | (Merriam-Webster 2020). All English word definitions are from the Online Merriam-Webster Dictionary. |

| 52 | (Utami 2014, pp. 53–54). |

| 53 | (Cronin 2017, p. 17). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).