Illuminating Our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose

Abstract

:1. Introduction—The Species Concept

2. Development of the Species Concept

2.1. Origin of Species

I have continued steadily reading & collecting facts on variation of domestic animals & plants & on the question of what are species; I have a grand body of facts & I think I can draw some sound conclusions. The general conclusion at which I have slowly been driven from a directly opposite conviction is that species are mutable & that allied species are co-descendants of common stocks [4]. (Stress ours).

What are the empirically verifiable conditions that have made possible and are making possible actually occurring history in its temporal extensions? … In what ways do historians constitute their history (Geschichte) when they fix it, orally or in writing and offer it to a circle of listeners or readers? Both… questions concern the mediation of being and saying, happening and recounting, (Geschichte and Historie) [20].

2.2. The Problem of Conceptual History

Olfers in 1814 made Lepas aurita Linn. into the genus Conchoderma: [Oken?] in 1815 gave name Branta to Lepas aurita & vittata & by so doing he alters essentially Olfer’s generic definition—Oken was right (as it turns out) & Lepas aurita & vittata must form together one genus. … Now I suppose I must retain Conchoderma of Olfers: I cannot make out a precise rule in Brit. Assoc. Report for this: when a genus is cut into two I see that old name is retained for part & altered to it; so I suppose definition may be enlarged to receive another species; though the cases are somewhat different [21]. (Stress ours).

Linnaeus gives no type to his genus Lepas though L. balanus comes first. Several oldish authors have used Lepas, exclusively for the pedunculate division, & the name has been given to the family & compounded in sub-generic names. Now this shows that old authors attached the name Lepas more particularly to the Pedunculate division.—Now if I were to use Lepas for Anatifera; I shd get rid of difficulty of 2d Edit of Hill & of difficulty of Anatifera vel Anatifa. Linnæus generic description is equally applicable to Anatifera & Balanus, though latter stands first, must this mere precedence rigorously outweigh the apparent opinion of many old naturalists? As for using Lepas in place of Balanus, I cannot. Everyone will understand by LepasAnatifera—so that convenience wd. be wonderfully thus suited—If I do not hear, I shall understand I have your consent [21]. (Stress ours).

…the world of everyday experience is made up of natural chemical and biological kinds whose exemplars manifest definite colors, change in time and are locally distinguished by their relations in time [28].

The taxonomy of living things that Darwin inherited was…a direct descendant via Aristotle of Plato’s essences…In Darwin’s day species of organisms were deemed to be as timeless as the perfect triangles and circles of Euclidean geometry [32].

…when there is so much variation within a group like the barnacle what—in terms of size, mode of reproduction, and life cycle—common features hold the family together? [11].

…awareness of a gap between historical events and the language used to represent them—both by the agents involved in these events and by historians retrospectively trying to reconstruct them … [37].

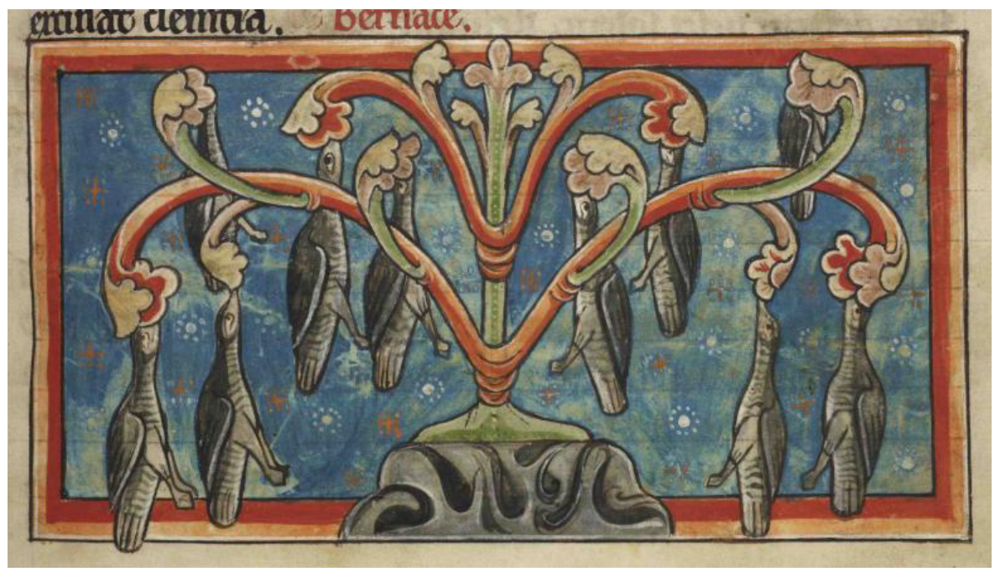

3. The Case of the Barnacle-Goose

There are here many birds that are called ‘Barnacles’ [barnacoe] which in a wonderful way Nature unnaturally produces; they are like wild geese but smaller. For they are born at first like pieces of gum on logs of timber washed by the waves. Then enclosed in shells of a free form, they hang by their beaks as if from the moss clinging to the wood and so at length in process of time obtaining a sure covering of feathers, they either dive off into the waters or fly away into free air … I have myself seen many times with my own eyes more than a thousand minute corpuscles of this kind of bird hanging to one log on the shore of the sea, enclosed in shells and already formed… [42].

…bird which is commonly called bernekke [which] takes its origin from pinewood which has been steeped for a long time in the sea. From the surface of the wood there exudes a certain viscous humour which in course of time assumes the shape of a little bird clothed in feathers and is seen to hang by its beak from the wood. This bird is eaten by the less discreet in times of fasting because it is not produced by maternal incubation from an egg. But what is this? It is certain that birds existed before eggs. Therefore should birds that do not emerge from an egg follow the dietary laws for fish any more than those birds which are begotten by the transmission of semen? Have not birds derived their origin from the water according to the irrefutable pages of holy doctrine? [43].

“This tree had been known for centuries to grow certain shellfish, which falling into the water, doe become foules, whom we call Barnakles… Brant Geese… or tree Geese” [44].

No one who has read this memoir can fail to be amazed that an absurdity such as we have been discussing has occupied the attention of scientists of the first rank for centuries, and that it has taken all this time to establish a truth which a properly conducted observation would have established… it would have been sufficient to have watched the life-history of the s (or) to have made a careful dissection… but that would have required care and attention, and it was more convenient to give a loose rein to the imagination [46].

4. Making Sense of the Barnacle-Goose

A vast network of created objects that bare profound theological meanings … made manifest through a contemplative consideration of how they analogously resemble moral and theological truths [49].

Be wise at length, wretched Jew, be wise even though late. The first Generation of man from dust without male or female [Adam] and the second from the male without the female [Eve] thou darest not deny in veneration of thy law. The third alone from male and female, because it is usual, thou approvest and affirmest with thy hard beard. But the fourth, in which alone is salvation, from female without male, that with obstinate malice thou detestest to thy own destruction. Blush, wretch, blush, and at least turn to nature. She is an argument for the faith and for our conviction procreates and produces every day animals without either male or female [26]. (Stress ours).

… the much more basic ideas of distinct stages, water-sheds, new beginnings, and punctual or decisive change. These narrative conventions, imported into intellectual history from 18th- and 19th-century political historiography, only distort the nonlinear and non-progressive cultural phenomena we describe. For the most part our story is not punctuated by clearly distinguished epistemes or turning points, but is instead undulatory, continuous, sometimes cyclical [26].

5. The Barnacle-Goose and Species Essentialism

…natural kinds. It holds that each natural kind can be defied in terms of properties that are possessed by all and only members of that kind. All gold has atomic number 79 and only god has that atomic number ... a natural kind is to be characterized by a property that is both necessary and sufficient for membership [34].

…species essentialism…has enjoyed a long and distinguished history, being traceable back, broadly speaking, to the views of Plato and Aristotle on the one hand, and the Book of Genesis on the other. The combination of these two traditions found its culmination in Carolus Linnaeus [55].

6. Conclusions: Darwin and the Problem of Species

I look at the term species as one arbitrarily given for the sake of convenience to a set of individuals closely resembling each other, and that it does not essentially differ from the term variety [3].In other words, he could determine no difference between species and varieties, and there are three good reasons for this [8]:

- That there is no process that distinguishes ‘varieties’ from ‘species’8.

- That any difference drawn between them sat on a seamless continuum and was made by the observer for pragmatic reasons.

- That the distinction between varieties and species was rejected because it rested on theological frames which relied on ideas about a divine creation rather than ‘natural selection’.

…we shall have to treat species in the same manner as those naturalists treat genera, who admit that genera are merely artificial combinations made for convenience. This may not be a cheering prospect but we shall at least be freed from a vain search for the undiscovered and undiscoverable essence of the term species[3]. (Stress ours).

In the following pages I mean by species those collections of individuals which have commonly been so designated by naturalists [3].Likewise he advised that:…in determining whether a form should be ranked as a species or a variety, the opinion of naturalists having sound judgment and wide experience seem the only guide to follow [3].

When the views entertained in this volume on the origin of species, or when analogous views are generally admitted, we can dimly foresee that there will be a considerable revolution in natural history. Systematists will be able to pursue their labours as at present; but they will not be incessantly haunted by the shadowy doubt whether this or that form be in essence a species [3]. (Stress ours).

What confronted Darwin then, was not a property essentialism but a multiplicity of species concepts based on similarity, fertility, sterility, geographic location and geologic placement, and descent [2].

References and Notes

- N. Carl, E. Hendrik, and S.J.-E. Maria. Systema Naturae, 1st ed. Nieuwkoop, The Netherlands: B. de Graaf, [1735] 1964. OCLC 460298195.

- R. Richard. The Species Problem; A Philosophical Analysis. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010, p. 325. [Google Scholar]

- D. Charles. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, 1st ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, [1859] 1964.

- “Darwin Correspondence Project Database. Letter to Rev. L. Jennyns. 12 October 1844, letter no. 782.” Available online: http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-782.

- W.M. Ernst. “The biological meaning of species.” In Biological Journal of Linnaean Society. 1969, pp. 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- H.G. Jody. Categories and Species: The Evolutionary and Cognitive Causes of the Species Problem. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, including an Autobiographical Chapter. D. Francis, ed. London: John Murray, 1877, Volume 2.

- E. Marc. “Darwin's Solution to the Species Problem.” In Synthese. 2010, pp. 405–425. [Google Scholar]

- S.B. John. “Of trees, geese and cirripedes: Man's quest for understanding.” Integrative Zoology 6 (2011): 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.B. John. “Barnacles, biologists, bigots and natural selection… Confound and exterminate the whole tribe!” Biology International 47 (2010): 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- S. Rececca. Darwin and the Barnacle. London: Faber and Faber, 2003, p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- D. Charles. “A Monograph on the fossil Lepadidae, or pedunculated cirripedes of Great Britain.” In Palaeontographical Society Monograph. 1851, Volume 13, pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- D. Charles. A Monograph on the Sub-class Cirripedia. The Lepadidae; or Pedunculated Cirripedes. London: Ray Society, 1852, p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- D. Charles. A Monograph on the Sub-class Cirripedia. The Balanidae and Verrucidae. London: Ray Society, 1854, p. 684. [Google Scholar]

- D. Charles. “A Monograph on the fossil Balanidae and Verrucidae of Great Britain.” In Palaeontographical Society Monograph. 1854, Volume 30, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- “Darwin Correspondence Project Database. Letter to J. Henslow on 2 July 1848, letter no.” 1225. Available online: http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-1189.

- K. Ulrich. “A comparative analysis of the Darwin-Wallace papers and the development of the concept of natural selection.” In Theory in Biosciences. 2003, Volume 122, pp. 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- K. Ulrich. “Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, directional selection, and the evolutionary sciences today.” In Naturwissenschaften. 2009, Volume 96, pp. 1247–1263. [Google Scholar]

- F. Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge. London: Tavistock Publications, 1974, p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- K. Reinhart. The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing concepts. Edited by T. Presner. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- “Darwin Correspondence Project Database. Letter to H.E. Strickland on 10 February 1849, letter no. 1225.” Available online: http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/entry-1225.

- S. Jacob. “The Barnacle goose myth in the Hebrew literature of the Middle Ages.” In Centaurus. 1961, Volume 7, pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- “World Register of Marine Species. Lepas Anatifera Linnaeus, 1758. Aphia ID: 10. 6149.” Available online: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=106149.

- T. Lynn. History of Magic and Experimental Science. New York: Macmillan, 1923, Volume 1, p. 420. [Google Scholar]

- F. Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994, p. 451. [Google Scholar]

- D. Lorraine, and P. Katharine. Wonders and the Order of Nature. New York: Zone Books, 1998, pp. 1150–1750. [Google Scholar]

- M.E.R. Anna. The Salt of the Earth Natural philosophy, Medicine and Chymistry in England 1650-1750. Boston: Brill, 2007, p. 293. [Google Scholar]

- A. Scott. “Origin of the Species and Genus Concepts: An Anthropological Perspective.” Journal of the History of Biology 20 (1987): 195–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. David. “The effects of essentialism on Taxonomy-Two Thousand years of Stasis.” British Journal of the Philosophy of Science 15 (1965): 314–326. [Google Scholar]

- E.R.L. Geoffrey. Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- S. Phillip. “John Locke, John Ray and the problem of the natural system.” Journal of History of Biology 5 (1972): 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Daniel. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 592. [Google Scholar]

- J. John. “Aristotle: Descriptor Animalium Princeps!” In The New Panorama of Animal Evolution. Edited by A. Legakis, S. Sfenthourkis, R. Polymene and M. Thessalou-Legaki. 2003, pp. 19–25, Proceedings of the 18th International Congress on Zoology. Sofia: Pensoft Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- S. Elliott. Philosophy of Biology, 2nd ed. Boulder: Westview Press, 2000, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- W.M. Ernst. TheGrowth of Biological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982, p. 974. [Google Scholar]

- K. David. “Darwin's keystone: The principle of divergence.” In The Cambridge Companion to the “Origin of Species”. Edited by M. Ruse and R. Richards. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- W. Hayden. Foreword to The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts. Edited by R. Koselleck and T. Presner. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- H-A. Edward. Barnacles in Nature and in Myth. London: Oxford University Press, 1928, p. 180. [Google Scholar]

- R.L. Edwin. Diversions of a Naturalist, 3rd ed. London: Methuen, 1919, p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- G. Gustav. The Jewish Encyclopedia.com. Available online: www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/2534-barnacle-goose (accessed on 10 April 2012).

- D. Daniel. “An Anser for Exeter Book Riddle 74.” In Words and Works: Studies in Medieval English Language and Literature in Honour of Fred C. Robinson. Edited by P.S. Baker and N. Howe. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- J. Joseph. The Jews of Angevin England: Documents and records. London: Macmillan, 1893, p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- N. Alexander. De Naturis Rerum: Libri Duo. Edited by T. Wright. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. London: Longman, Green, ("Rolls Series" 34), 1863, 1180. Archival Reference: Library of Magdalen College Oxford; BL MSS. Reg. 12 G xi. 12 F. xiv.

- G. John. The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes. London: Imprinted by Edmund Bollifant for Bonham & John Norton, 1597. [Google Scholar]

- T. Whitney. “Becoming Plant: Magnifying a History of Micromedia Circuits in Nehemeiah Grew’s Anatomy of Plants (1682).” Available online: http://postmedievalcrowdreview.wordpress.com/papers/trettien (accessed on 8 October 2012).

- G. Jean-Étienne. “Sixième Mémoire sur les Conques anatifères, à l'occasion desquelles on parle de la naissance spontanée.” Mémoires sur différentes parties des Sciences et Arts, Paris 1768-1783 (1783): 238–303. [Google Scholar]

- H. Urban. “Gerald the Naturalist.” Speculum 11 (1935): 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- S.B. John. “Goose barnacles, acorn barnacles, wart barnacles and burrowing barnacles-Subclass Cirripedia.” In The New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity: A Species 2000 Symposium Review. Edited by D.P. Gordon. Christchurch: University of Canterbury Press, 2010, Volume 2, pp. 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- H. Peter. “Linnaeus as a Second Adam: Taxonomy and the religious vocation.” Zygon 44 (2009): 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Neremiah. “The Anatomy of Plants: With an Idea of a Philosophical History of Plants and Several Other Lectures Read before the Royal Society.” London: W. Rawlins, 1682. [Google Scholar]

- M. Alan. History of Botanical science: An Account of the development of Botany from Ancient Times to the Present Day. New York: Academic Press, 1981, p. 474. [Google Scholar]

- H. Peter. The Bible, Protestantism and the Rise of Natural Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, p. 313. [Google Scholar]

- B. Klaas van, and V. Arjo. The Book of Nature in Early Modern and Modern History. Leuven: Peeters, 2006, p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- S.E. Elliott. “Population thinking and Essentialism.” In The Units of Evolution: Essays on the Nature of Species. Edited by M. Ereshefsky. Cambridge: Bradford Books, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- S. David. Darwin and the Nature of Species. Albany: SUNY Press, 2007, p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- E. Marc. The Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy: A Philosophical Study of Biological Taxonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. “De Partibus Animalium I.” In A New Aristotle Reader. Edited by D.M. Balme and J.L. Ackrill. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987, p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- S. Charles. A Short History of Biology to about the Year 1900. A General Introduction to the Study of Living Things, 3rd ed. London: Abelard-Schuman, 1959, p. 580. [Google Scholar]

- O. Brian. The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- B. John. “Speaking of Species: Darwin's Strategy.” In The Darwinian Heritage. Edited by D. Princeton. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985, pp. 265–281. [Google Scholar]

- D. Michael. “Biological Realisms.” In From Truth to Reality: New Essays in Logic and Metaphysics. Edited by D. Heather. New York: Routledge, 2009, pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- W. Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Edited by G.E. Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwells, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 1 Although some decades prior to this, Jean-Baptist Lamarck had concluded in his Philosophie Zoologique (1806) that some organisms might change, it was Darwin who first saw both the universality of evolution and the deep time frame in which it operated.

- 2 In his fourth (1744) edition of his Systema Naturae Linnaeus described the barnacle goose thus: BERNICA: seu ANSER SCOTICUS & CONCHA ANATIFERA e lignis putridi, in mare abjectis, nasci a Vetribus creditur. Sed fucum impsuit Lepas interanis suis penniformibus, & modo ahaerendi, ac si verus ille Anser Bernicla inde oriretur

- 3 This changed in the late 20th Century, when increasing mobility and trade led to a greater need to recognize subtle differences between species, e.g., to identify invasive and poisonous taxa and to enhance (or restrict) interbreeding.

- 4 As Stott shows, only in the 1840s did Darwin discover how absolutely anomalous this barnacle was.

- 5 Although Heron-Allen spent some time reviewing images of birds and other animals on Mycenaean pottery (circa 1600–1100 BC) he concluded that it was unclear that the Mycenaeans were claiming any biological relationship between geese and barnacles.

- 6 In modern parlance, the term “shellfish” exclusively applies to molluscs. Barnacles are crustaceans.

- 7 In his De Naturis Rerum Neckam provides the earliest European notice of the compass i.e., a floating magnet as a guide to seamen.

- 8 Most of Darwin’s varieties remain as valid species and although some were subsequently reassigned to other taxa, recent work has resulted in these being returned, close to where Darwin had originally assigned them [48].

- 9 Darwin put the problem clearly to Hooker: It is really laughable to see what different ideas are prominent in various naturalists’ minds, when they speak of ‘species’; in some resemblance is everything and descent of little weight-in some, resemblance seems to go for nothing and Creation the reigning idea-in some sterility and unfailing test, with others it is not worth a farthing. Darwin to Hooker, 24 Dec. 1856 [7].

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Buckeridge, J.; Watts, R. Illuminating Our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose. Humanities 2012, 1, 145-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/h1030145

Buckeridge J, Watts R. Illuminating Our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose. Humanities. 2012; 1(3):145-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/h1030145

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuckeridge, John, and Rob Watts. 2012. "Illuminating Our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose" Humanities 1, no. 3: 145-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/h1030145

APA StyleBuckeridge, J., & Watts, R. (2012). Illuminating Our World: An Essay on the Unraveling of the Species Problem, with Assistance from a Barnacle and a Goose. Humanities, 1(3), 145-165. https://doi.org/10.3390/h1030145