Abstract

Structural social changes and population aging are emerging as important policy issues in many countries around the world. In particular, although early retirees aged 50 or older are left behind from social welfare services and suffer from worsening social problems, policies have often only focused on elderly people aged 65 or older and vulnerable groups. Based on the theory of a welfare service delivery system, the present study analyzed the case of the Seoul 50 Plus Project in South Korea, which was established to enhance service professionalism and integrate various services to keep up with a changing environment, considering four factors: ‘integration’, ‘accessibility’, ‘systematic function distribution’, and ‘participation’. The case analysis revealed that interconnected service content, which can improve leisure activities, hobbies, and self-development, is very important along with job creation from social services to the 50 plus generation.

1. Introduction

According to the UN report World Population Aging (2017), the number of people aged 60 or older around the world is 962 million as of 2017, which accounts for 13% of the global population. As population aging continues, the number of those aged 60 or older increases by 3% each year (UN 2017). Korea also has been transforming into an aging country since 2000 when the percentage of those aged 65 or older first exceeded 7% of the total population. The country has become an aged country in the shortest period of time globally, as the percentage surpassed 14.2% in 2017. Furthermore, a survey published by Statistics Korea (2017) forecasts that the percentage of those aged 65 or older will sharply increase from 12.8% in 2015 to 30% in 2045, and the average life expectancy will reach 82.9 years.

While policy actions have been put in place to address population aging, baby boomers, who account for the largest proportion of the population in Korea, are beginning to retire early. The early retirement of those in their 50s has caught the country off guard and is increasingly becoming a social issue. When the 50 plus generation, aged 50–64, reaches 12 million in 2019 with early retirement and increased life expectancy, it will account for 23% of Korea’s total population of 51.8 million (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs 2015; Economic Survey of Korea 2018).

According to the Seoul Metropolitan Government, while the number of those in their 50s increases with increased life expectancy, they retire earlier and earlier; the average retirement age stands at 53. Although many of these people want to work, they are less likely to acquire another job, and the quality of jobs they may undertake after retirement is quite low. The central government’s efforts focus on welfare programs, which support the elderly (aged 65 or older) and vulnerable groups. However, the Seoul Metropolitan government needs to plan the new policies for the 50 plus generation such as preventative support to the life redesign and field-based sustainable support through links with related jobs, and social contributions.

In response, the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation was established in 2016, and systematic and integrated services have begun to support the social participation of the 50 plus generation (Nam 2018). The Seoul 50 Plus Foundation developed and successfully implemented systematic, integrated, and sustainable policies to address the various social participation needs of the 50 plus generation that were left behind in government policies. The Foundation modeled a new paradigm that turns socioeconomic problems caused by demographic structure and social changes into opportunities. This paradigm is an innovative case of public institution-led social participation service policies for the 50 plus generation—the first of its kind not only in Korea and but also around the world (Han 2014).

Thus, this study analyzes the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s case of service policies to support the 50 plus generation and examines the characteristics of public services for the sustainable social participation of those in their 50s and the successful operation of the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s social welfare service delivery system to provide sustainable public services. By doing so, the present study aims to suggest specific implications that may help aging cities and countries around the world to explore the diversity and sustainable success of 50 plus social participation policies over the long term and strategies to operate and differentiate the integrated platform of 50 plus social welfare services.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Welfare Delivery System

The definition of social services varies among researchers and depends on each country’s level of institutional development. The UK uses the concept of personal social service, which has a narrower sense than social service. Personal social service refers to a support and care service that aims to meet social protection needs (Cutler and Waine 1994). In the US, social service also refers to a narrow sense of service that supports socially disadvantaged groups in terms of social protection, disabilities, and diseases excluding income, education, healthcare, and culture (Kendall et al. 2006). In implementing social services, Korea adopts a broad sense of the term and defines it as a service socially provided to improve the welfare and quality of life of individuals or society as a whole (Jung 2009; Lee 2010).

While traditional social welfare services are provided at the national minimum to the recipients of Basic Living Security, the recipients of social services have been expanded to cover those who “need to receive services and have needs for such services” with 100% or less of the national average household income. The provided services are also expanded across various areas that require support in daily life such as nursing, childcare, and caregiving. With the expansion and diversification of social service recipients and areas, the traditional mechanism that finances local non-profit organizations to provide welfare services exposes various limitations. Consequently, vouchers are used as a new delivery method to pay expenses directly to social service recipients: the delivery method has shifted from provider-centered to recipient-centered (Lee 2008; Warner and Gradus 2009).

In particular, rapid population aging, rising divorce rates, falling birth rates, labor and job insecurity, and a widening gap between the rich and the poor are becoming concerns for many countries around the globe, and there are growing calls for a service delivery system that can respond to the explosive demand of welfare services as a result of such socioenvironmental changes (Martin and Kettner 1996). In the past, key components of the social welfare delivery system were discussed from the perspective of service providers in terms of how to improve efficiency, and the reorganization or system of welfare services was planned mostly through public structures and frameworks. However, as more and more public or social welfare services are delivered by local or private social welfare organizations around the world, there is a growing interest in a recipient-centered service delivery system (Dinerman 1992; Kang 2008; Oh and Nam 2012).

The delivery system exists between service providers in the local community and between service providers and consumers (Gilbert and Terrell 2002). In other words, the welfare service delivery system as a procedure, instrument, and framework by which welfare resources are provided to users refers to a set of procedures and systems through which welfare resources are delivered from the central or local government to welfare service users. Gates (1980) and Gilbert and Specht (1986) defined the social welfare service delivery system as an organizational device to link social welfare service providers and consumers, and Friedlander and Apte (1980) comprehensively defined it as the whole service delivery network between public and private welfare organizations for clients.

The service delivery system is, in a way, an organizational linkage between the stakeholders that provide policy services or benefits and between service providers and consumers (Cha 2006; Whitaker 1980; Yang et al. 2016). As Mizrahi and Davis (1995) defined service integration as a holistic and systemic work to overcome problems with a fragmented service delivery system and resolve a discrepancy between intervention programs, professional services, and the problems or needs of individuals or families in the local community, social welfare services require an integrated service system to simplify various recipients and complex services or benefits and organize them more efficiently. Hence, the delivery system refers to a system that delivers the services by interconnecting organizations or policy recipients, not activities by a single organization to provide policy services effectively.

2.2. Services to Support the Social Participation of the 50 Plus Generation

According to Byun (2011), advanced countries that grew into aging countries before Korea have long conducted comparative studies between generations and implemented social participation policies for those in their 50s. In the US, extensive studies have been conducted since the end of World War II about changes along the life cycle and life after retirement. In the UK, aging policies have been in place since 2000, and the population continues to age, as the elderly (aged 65 or older) accounted for 17% of the population in 2010. In Japan, a wider range of studies has been conducted since the 1980s about the ripple effect of retirement in terms of socioeconomics. Germany became an aging country in 1932 and was an aged country in 1972—the first among advanced countries—and has implemented policies to support the 50 plus generation, beginning with a policy that extended the retirement age in 1972 (Gilbert and Specht 1986). Around the world, aging advanced countries have mainly pursued policies that supported the social participation of the 50 plus generation focusing on employment, extending the retirement age, and returning those in their 50s or older who are unemployed for a long time to the labor market (Fragoso and Valadas 2018).

Fifty plus projects first emerged from and have been operated in advanced countries. In the US, policies that support the 50 plus generation are categorized into three groups. The Workforce Investment Program provides integrated support based on recipients and the local community by introducing education or training opportunities to job seekers or offering career counseling (Seoul 50 plus Foundation 2018). The American Job Center is a one-stop career service, and the Senior Community Service Employment Program (SCSEP) trains low-income individuals aged 55 or above in the local community. Some of the most notable organizations in the US include the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) and Encore.org (Encore.org, Civic Ventures) (Kim 2017).

Since its establishment in 1958, AARP has become the largest non-profit private retiree organization in the US, with 37 million members aged 50 or older. Encore.org runs various programs that encourage and spread an “encore” career for those over 50. The most noticeable 50 plus generation programs in Germany, whose population aging has accelerated with aging baby boomers since the 1960s and low birth rates in the 1970s, are Initiative 50 Plus, which aims to achieve 55% in the employment rate of those aged 55 or above and reduce their early retirement, and Perspective 50 Plus, a government-led employment promoting program that the German Federal Employment Agency launched in 2005 with local employment pacts (Kim 2017). The program focuses on the long-term unemployed aged 50 or older, develops their job skills, and links them with employment through trilateral cooperation between industry, academia, and research. Consulting firms also participate jointly in the program to provide age-tailored consulting, and companies in the private sector provide job training to job seekers.

The primary purpose of the program is to encourage the short-term older unemployed to get a job, create a working environment that does not discriminate against older workers, and promote lifelong working (Eckardt and Benneworth 2018). Policies for the 50 plus generation in the UK include Age Positive, New Deal 50 Plus, and Link Age Plus. Age Positive is a government-led campaign that began in 2001 to lead perception changes about the employment of the 50 plus generation, promote related advantages, and change the practice of employers and employees. It selects institutions, private organizations, or academic institutes that meet the government’s guidelines and carries out advice activities in various areas such as employment management and training through government-run online websites. New Deal 50 Plus provides training subsidies, individual counseling, and advice to job seekers aged 50 or older who have received disability, unemployment, and income support benefits for at least six months. Link Age Plus links employment and volunteering with funding from the Ministry of Labour (Mizrahi and Davis 1995; Skidmore 1983).

Japan is implementing support policies for the 50 plus generation based on the Basic Law on Measures for the Aging Society (Ministry of Employment and Labor 2013). The Tokyo Foundation for Employment Services is a well-known public foundation that was established to support the job opportunities and employment of Japanese people and Tokyo citizens aged 50 or older. Since 1981, Silver Human Resources Centers in shichōson (municipalities) in Tokyo has identified appropriate jobs to train those aged 50 or older, researched cases in other countries to link with employment, and operated senior job counseling and employment centers. They were integrated in 2004 and have since then been operated with the Tokyo Metropolis Occupational Development Center for People with Physical and Mental Disabilities. Since 2016, Silver Human Resources Centers have supported employers to upgrade their employment environments and nurture talented individuals and have provided employment support services not only to elderly people but to various other job-seekers such as people with disabilities, women, and young people. In addition, they also implement the Life-Long Active Society Model Project in the local community (Kim 2017; Cho 2015).

3. Research Methods

3.1. Background of the Selection of the 50 Plus Foundation

Since the 1990s, Korea has actively implemented social participation policies for the 50 plus generation that have mainly been led by the central government. In the early days, job transition support systems or senior internships for retirees-to-be were created by focusing mainly on employment support (Ahn and Sung 2016). Measures for the stable employment of the 50 plus generation including employment extension subsidies, wage peak subsidies, new middle-aged job employment incentives, support for social contribution activities, middle-aged job hope centers, life cycle career design services, senior talent banks, and projects to support jobs in government departments are currently being implemented (Lee 2013; Won and Song 2014).

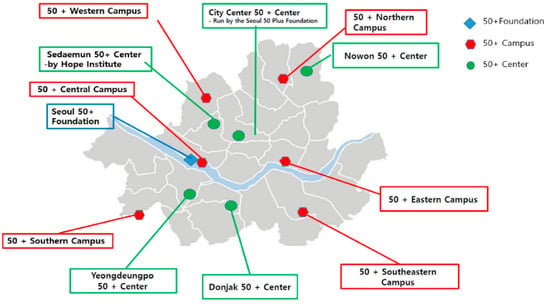

In 2012, Mayor Park Won-soon discussed the seriousness of policies for an increasingly aging population in Seoul. While the 50 plus generation has been left behind from support policies and has become a social issue due to early retirement and increased life expectancy, the Post-Retirement Second Life Center began as a pilot program commissioned in the private sector to support the social participation of the 50 plus generation. After the Center launched, the Seoul Metropolitan Government announced the Comprehensive Baby Boomer Cheering Plan in April 2014, which aims to provide more systematic and active support to baby boomers, established the Post-Retirement Support Division, organized the Post-Retirement Second Life support group composed of experts in the private sector, and created a public-private support group. And the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation was established in April 2016 (see Figure 1). Since then, the foundation has continued to expand its campuses, and the services operated by the foundation have been able to deliver successful outcomes as the number of participants in campus training increased sharply from 164,528 in 2017 to 288,828 in 2018 (Seoul 50 Plus Foundation 2018).

Figure 1.

Seoul 50 Plus Foundation (as of 2018).

According to a survey by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, the average age of 50 plus generation is 23% (2.19 million) of the population in Seoul. By recognizing this as social problem, the Seoul Metropolitan Government established an ordinance to support the Post-Retirement Second Life of the 50 plus generation as those from ages 50 to 64 (separate from the elderly aged 65 or older), and implemented the Post-Retirement Second Life Project for them (Seoul Institute 2015). In this context, the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation, which is equipped with professionalism, accountability, and public value, took the launched innovative integrated services to support the social participation of the 50 plus generation. All related institutions from citizens to civil society groups have participated in implementing 50 plus policies, and the demands and needs of participants have been reflected in such policies.

The 50 plus generation needed preemptive and preventative support like the life redesign program, and field-based sustainable support through links with related organizations, jobs, and social contributions. The Seoul Metropolitan Government planned to implement the 50 Plus Project, intend the policies focused on supporting the 50 plus generation, efficiently operate 50 Plus Campus and Centers, and ensure responsible operation and public value for the sustainable support of the 50 plus generation. The foundation was designed as the operator for efficient management with strong momentum and representation.

3.2. Analytical Framework and Method

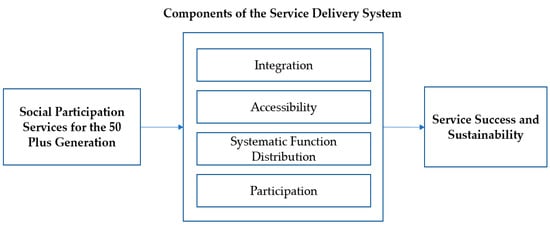

The study intended to examine the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s social participation service activities for the 50 plus generation. An in-depth analysis was conducted of the establishment of a practical social service system for effective and integrated policy service activities that aim to improve the quality of life for the 50 plus generation across an increasingly aging country and sustain their social participation activities (Serre 2017; O’Grady 2018). To this end, among the components of social welfare service systems that have been defined by previous studies, such as integration, continuity, accessibility, and accountability as asserted by Gilbert and Terrell (2002) and systematic function distribution, professionalism, accountability, accessibility, integration, and participation as suggested by Jo (2004), the present study excluded service factors such as continuity, professionalism, and accountability.

The research attempted to analyze the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s service system to reinforce the sustainability of the 50 plus generation’s social participation based on four administrative factors that practically explain its implemented service system: integration, accessibility, systematic function distribution, and participation. As shown Figure 2, the present study analyzes specific success factors and activities regarding the ways in which the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s 50 plus social participation services were established as successful social services through these four factors of service delivery systems and produced sustainable social participation.

Figure 2.

Conceptual research model.

First, integration is necessary since the needs of recipients using welfare services do not involve a single problem, but two or more complex problems (Muñoz-Guzmán et al. 2015; Kahn and Kamerman 1992). In this regard, this study analyzes the 50 Plus Project in terms of various services and the organizations or systems that have been established to provide such services. Second, an accessible welfare service system should allow anyone who requires the service to receive the service they need at a time and place that is convenient to them through a simple procedure (Gates 1980; Gilbert and Specht 1986). In this respect, this study analyzes the 50 Plus Project in terms of service accessibility for recipients considering various aspects such as physical distance and time. Third, systematic function distribution refers to a welfare service delivery system the functions of which are divided or distributed systematically (Seo 2008; Jo 2004). Thus, this article analyzes the delivery process between organizations that divide the foundation’s service functions. Finally, a service delivery system should identify the needs of local residences through widespread participation from the local community (Sung 1992). Accordingly, this study analyzes the ways in which the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s various stakeholders with private organizations or groups beyond government activities.

This research presents an innovative case that can establish an integrated and expanded foundation for social participation services for the 50 plus generation in many aging cities, suggests success factors that can sustainably drive such services forward, not only reinforcing the relationship between recipients and stakeholders but also encouraging the social participation of recipients. In this regard, this case study examines a phenomenon as a single case in its real-life context, as suggested by Yin (1994), where the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clear. To in-depth facts from the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s design, implementation, and service outcomes of the 50 Plus Foundation the research method used a by Woods and Catanzaro (1998) that investigates and analyzes in-depth data related to background, current status, environmental characteristics, and interactions under naturalistic conditions.

For basic data, the research analyzed the interview data of project managers and recipients and collected and examined key documents used in social service projects. Documents were collected starting at the end of 2011, when the Seoul Metropolitan Government began to explore social participation projects for the Post-Retirement Second Life of the 50 plus generation, until the present. From November to December 2018, the interview data were collected from various angles with three key staff members and managers, two government officials, and three stakeholders in public and private organizations. A total of eight people directly involved in the foundation activities were interviewed either one-on-one or by off-line meeting. Through these methods, the case study not only analyzed the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s organizational operation and service quality but also obtained information about various projects and programs operated by the foundation for the sustainability of recipients’ social participation.

4. Case Study

4.1. Integration

The counseling services of the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation are divided into two tracks. The first track provides professional counseling in seven areas of the 50 plus generation’s life redesign. The 50 Plus Foundation placed its focus on moving beyond providing help to solve career-related or financial problems and to instead offer various services that help the 50 plus generation lead a healthy life over the long term with the aim of designing their life. The focus was placed on the seven life redesign areas; ‘job, finance’, ‘social relationship’, ‘family’, ‘health’, ‘social contribution’, and ‘leisure’, were used to identify required service programs and implement interconnected service policies for the programs.

Likewise, the service operates 50 plus participants’ community activities in seven areas and creation activities by discovering a job model. Additionally, the foundation provides follow-up support such as linking jobs with related organizations and encourages startups through incubating. As such, support is provided directly to 50 plus generation-centered groups and research for seven areas of life design, programs planned by the 50 plus generation, or their community activities. A consultant from the Counseling Center explains the uniqueness of such services:

“Consulting services provided by our foundation move beyond simple services that are offered by other organizations such as policy support and analyze many concerns of the 50 plus generation from various angles in an integrated way. We have a system that delivers tailored support services that design and implement an individual’s life cycle. Accordingly, these services are very significant as they pursue holistic support that can continue to support an individual’s life and help him or her to live a healthy and meaningful life without being disconnected from society, instead of one-off government support services.”

The second track matches education or training courses with the needs of 50 plus counseling clients. The 50 Plus Counseling Center provides one-stop services for seven areas of life redesign and comprehensive support that connects all of Seoul’s policies and systems with various professional organizations. With counseling from professional consultants in the 50 plus generation, it supports social relationships by connecting projects and social networks, runs life redesign programs, and nurtures and assigns 50 plus consultants and moderators. The center offers a tailored learning process design that introduces training programs tailored to the propensities and characteristics of counselors, provides 50 plus information that introduces policies, systems, groups, and programs related to the 50 plus generation, and supports the formation of a network. The system is optimized to establish field-based policies through people-to-people and information exchanges with the 50 plus generation.

4.2. Accessibility

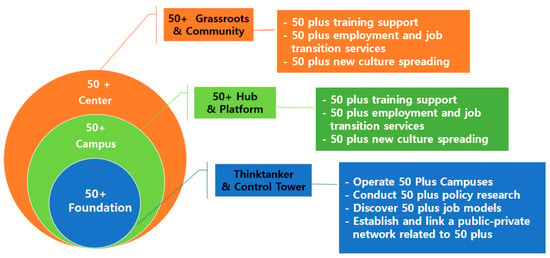

The 50 Plus Foundation aims to improve the 50 plus generation’s quality of life and promote a shift in the perception of their transition period, aiming to enhance their social participation and activities in which they can share experiences. To achieve these objectives, the Seoul Metropolitan Government generated innovative services that strengthen field-based implementation together with the 50 plus generation. The service functions are distributed to the ‘foundation’, ‘campuses’, and ‘centers’ to establish an integrated operation system so that tailored programs reflecting local characteristics can be operated efficiently while maintaining consistency, continuity, and uniformity in the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s support policies for the 50 plus generation’s social participation.

As a result, the organization of the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation consists of three 50 Plus Campuses and five 50 Plus Centers around the Control Tower as of 2019 (see Figure 3). The Seoul 50 Plus Foundation oversees the 50 Plus Project and operates and supports 50 Plus Campuses and Centers. The foundation directly operates 50 Plus Campuses, which serve as hubs for providing sustainable support services across Seoul while maintaining the consistency of the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s policies. With district budgets, the foundation also commissions the private sector to operate 50 Plus Centers, which serve as hubs for the activities of grassroots organizations in smaller parts of the city. This allows such organizations to provide local programs reflecting local characteristics.

Figure 3.

Structure of the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation (Reference: Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s Annual Report).

The Seoul 50 Plus Campus and Center are district facilities that provide a site for networking activities between the 50 plus generation. The campuses and centers currently deliver local training programs and community-linked programs. The 50 plus new culture and infrastructure strategy provides locations in which the 50 plus generation can share activities, build a community, and create a new culture. Furthermore, it supports community activities based on common interests in which the 50 plus generation takes the clubs, small groups, associations, organizations, cooperatives, and legal entities. It also provides various places; shared offices, lecture rooms, meeting rooms, forums, community halls, and startup innovation centers where different generations can exchange ideas. The holistic design of the 50 Plus Centers and Campuses and the operation of communities are intended to encourage the active participation of 50 plus service providers and can serve as an important element in ensuring service recipients’ active and sustainable participation and making it easier to access services.

The 50 Plus Foundation has also established the 50 Plus Information System, an integrated and efficient platform that gathers generational information in one place to share and provide information. It provides users with quick, accurate, and tailored services in an efficient and integrated way so that all 50 plus generation information such as jobs, communities, counseling, training courses, and contests can be shared and exchanged. The 50 Plus Information System is a tool that facilitates online access to services and offers users more opportunities to log in any time, receive various types of information, and find support services that fit their needs. Strategies that establish a holistic organization to facilitate access to services across all parts of Seoul and build a community-centered network for those in the 50 plus generation who are not familiar with community or social participation activities have encouraged more active participation from this generation, resulting in sustainable participation in activities and an a consistently increasing number of participants.

4.3. Systematic Function Distribution

The 50 Plus Foundation required a systematic and professional operation management of social welfare services and established a service participation process model in which participants begin with counseling, go through a preliminary process to explore various opportunities, build their competencies through a specific retraining or education program, choose their desired social participation activities, and receive personalized support. Integrated support services for the 50 plus generation’s social participation begin with 50 Plus Counseling Center, where counseling is provided with 50 plus participants or expert consultants. Participants then join job- or activity-exploring courses on life transition, jobs, activities, and daily life skills, moving on to life transition professional courses that offer more professional training, job or activities professional courses, or job-connecting training courses in partnership with professional organizations. This leads to social participation activities in jobs or activities.

The primary objective of these training courses is to identify jobs that contribute to society with a strategy that involves the 50 plus generation in the discovery of jobs and occupations to create shared social value, implement partnering projects, help them find the latter part of their life rewarding, and use their competencies and experiences. Discovered job models lead to job support services; they provide support for the establishment of social enterprises, cooperatives, and other non-profit organizations with shared offices or group support, result in social contribution activities through talent donation, and connect with training courses or related organizations through newly discovered job models. Allowing the 50 plus generation to take the lead as job seekers rather than welfare recipients engages their competencies and experiences, allows them to explore new career paths, and provides them with new opportunities. This method supports activities that create new job demand, allowing the 50 plus generation to participate in social activities in a sustainable way. A project manager from the 50 Plus Foundation’s Public Relations and Cooperation Team explained the functions in each step of these courses as follows:

“Since the Seoul 50 Plus Project aims to not only support services but provide tailored services that can create participation, settlement, and sustainable social participation right from the design phase, the process design and each function have established an organic and strategic relationship and laid the groundwork where all functions of services can be operated systematically and organically by responsible centers or organizations. Accordingly, even though many participants sign up, one-on-one tailored services are operated smoothly. We are continuing to develop our foundation to increase the success rate in social participation, so we expect to deliver more advanced services in the future.”

The Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s job strategy focuses on using the 50 plus generation’s experiences and abilities so that they can realize personal achievements, secure an income, generate social change, and contribute to society, providing opportunities to explore new careers, and creating and spreading job models by discovering and connecting the occupations that have social needs. Rather than simply providing job or training programs, the model delivers active support through reinforcing social networks that have deteriorated after retirement. The model allows the transition into a new career, startups through community. Additionally, it provides them with practical benefits and opportunities by implementing projects in connection with private enterprises and offering support in partnership with professional organizations. This model is further developed each year by discovering, connecting, and retraining the 50 plus generation with new and sustainable job models.

4.4. Participation

The Seoul Metropolitan Government is a major stakeholder that supports and supervises the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation to provide realistic and integrated social participation services to the 50 plus generation. It plays a role in maintaining an organic relationship between the foundation and center-related organizations. The organizations in civil society serve as links to spaces in the local community that public institutions have difficulty working or accessing. This allows the 50 plus generation to build a cooperative network and lay the community groundwork, helping to expand various activities and effective services. Stakeholders in the private sector support professional and innovative programs that public institutions cannot provide to allow the 50 plus generation to receive systematic and professional training and consulting and participate realistically in society.

The number of partnering organizations that provide training to the 50 plus generation to establish a platform where they can share their experience and knowledge has increased every year. Such partners include various public institutions, private organizations, foundations, private enterprises, social enterprises, and cooperatives such as the Ministry of Employment and Labor, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Seoul Welfare Foundation, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs etc.

Furthermore, with the 50 plus generation’s community activities, support for research by 50 plus participants, programs, shared offices, intergenerational integration startup campuses, 50 plus forums, and 50 plus festivals, the foundation provides support to enable 50 plus participants to proactively create various activities. Furthermore, by building and developing an organic relationship between the 50 plus generation, private organizations, civil society groups, and the foundation in job education, health, finance, counseling, and culture, it shares each organization’s professionalism and resources, explores joint planning for collaborative projects, and focuses on expanding the infrastructure. This results in the dissemination of a new culture and empathy regarding the 50 plus generation by increasing their information and databases and securing an information network. As of 2018, the foundation has partnerships with 100 organizations and groups.

The CEO of Hope Doremi discusses the organization’s partnership with the 50 Plus Foundation in the following:

“Together with the 50 Plus Foundation, Hope Doremi has carried out social contribution activity projects and helped many people in their 50s to participate in social activities since 2016. We have done various and sustainable activities contributing to the local community and been accepted positively by participants. I believe that co-existence with private organizations like us beyond government agencies not only disseminates social services, it also contributes to shared growth with various stakeholders and ultimately improves positive infrastructure and social service competencies across society.”

The field-based management provides cultural sites in which 50 plus participants take the lead, exchange, and work with one another. The foundation operates a systematic support system that offers 50 plus professional counseling, followed by training tailored to the needs of the 50 plus generation, and jobs, specific activities, or leisure. By reinforcing governance that connects related organizations, participants, the foundation, civil society groups, and the Seoul Metropolitan Government and operating an integrated information system, the Seoul 50 Plus Foundation’s integrated social participation services support the 50 plus generation’s sustainable social participation. The 50 Plus Project based on the integrated governance system across all parts of society results in the accumulation of organizational social service competencies and know-how regarding encouraging social participation from those in their 50s, includes more diverse participants, and performs an important function in maintaining sustainable services in society.

5. Conclusions

This case study of Seoul’s social participation service model for the 50 plus generation has identified the following implications. First, although national social welfare systems for elderly groups were primarily focused on providing support in the past, the social welfare system for the 50 plus generation now requires a participation-centered service system to consider their quality of life rather than solely focusing on productivity. As in the case of the Seoul 50 Plus Project, social services should be considered in the integrated service system to encourage and support voluntary participation in jobs, leisure, social contributions, health, family, finance, and social relationships.

Second, in accordance with changing trends, the 50 plus generation’s social welfare should move beyond startup or retirement support and ensure that they are not alienated from society and have access to participate more actively in job-seeking activities, community activities, and other civil society activities. In this respect, it is necessary to explore services in various aspects including society, culture, and economy and participation-centered programs. Finally, it is necessary to connect a network with the local community, social enterprises, and for-profit enterprises and change policy strategies. This will allow the realization of the effectiveness of realistic and sustainable social participation beyond the traditional social service delivery framework that designs or implements policies from the central or local government in a one-way, top-down direction.

However, this case study has only examined a single case. It means that this case study cannot represent the diversity of all social participation service activities for the 50 plus generation in a large city in Northeast Asia. Furthermore, the present study has limitations regarding subjective interpretations that occur in the analysis process. To overcome such limitations, it is necessary to conduct a comparative case study to juxtapose the social participation welfare service cases with those of large cities in other leading countries in Northeast Asia such as China or Japan. In addition, although this study used only the four factors to the case analysis but other factors to reinforce the social service system should be considered and empirically examined their effectiveness. Last, the perspective of social service providers without participant’s interviews would make it possible to differences regarding whether the social participation activities of service recipients in their 50s can ultimately lead to their service satisfaction with life. The future study will need a perspective balance between users and providers.

Author Contributions

Data curation, M.L.; Formal analysis, B.K.; Methodology, B.K.; Supervision, M.M.; Writing—original draft, M.L. and B.K.; Writing—review & editing, M.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahn, Jun Ki, and Choi Ki Sung. 2016. The Career Characteristics of Those in Their 40s and 50s and Support Policy Options. Seoul: Korea Employment Information Service. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, Roo Na. 2011. A Comparative Study of Korea and Japan in Social Participation Support Policies for the Baby Boom Generation After Retirement. Seoul: Health and Social Welfare Review. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Bo Hyun. 2006. A Study on the Reorganization and Development Issue of Social Welfare Delivery System. Journal of Public Welfare Administration 16: 2572–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Dal Ho. 2015. Job Characteristics and Labour Policy Implications for Seoul. Seoul: Seoul Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, Tony, and Barbara Waine. 1994. Managing the Welfare State: The Politics of Public Sector Management. Oxford: Berg Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dinerman, Miriam. 1992. Managing the Maze; Case Management and Service Delivery. Administration in Social Work 16: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, Franziska, and Paul Benneworth. 2018. The G1000 Firework Dialogue as a Social Learning System: A Community of Practice Approach. Social Science 7: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Survey of Korea. 2018. Achieving New Paradigm for Inclusive Growth. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/Achieving-a-new-paradigm-for-inclusive-growth-OECD-economic-survey-Korea-June-2018.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Fragoso, António, and Sandra T. Valadas. 2018. The Rise and Fall of Adult Community Education in Portugal. Social Science 7: 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, Walter. A., and Robert Z. Apte. 1980. Introduction to Social Welfare, 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Bruce L. 1980. Social Program Administration: The Implementation of Social Policy. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Neil, and Harry Specht. 1986. Dimensions of Social Welfare Policy. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Neil, and Paul Terrell. 2002. Dimensions of Social Welfare Policy, 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Ginsberg. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Dong Whee. 2014. A Study on Active Aging Policy in Aged Society. Journal of Welfare for the Aged 64: 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Sung Shin. 2004. An Empirical Study for Interconnection between the Public and Private Sectors in the Social Welfare Delivery System. Ph.D. dissertation, Sangmyung University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Ik Jung. 2009. A Critical Perspective on the Integration of Service Delivery Systems in Child-Youth Policy. Korean Journal of Social Welfare Studies 40: 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Alfred J., and Sheila B. Kamerman. 1992. Integrating Services Integration: An Overview of Initiatives, Issues, and Possibilities. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Hye Kyu. 2008. Social Service Policy and the Community Social Service Provision Systems in Korea. Journal of Critical Social Welfare 25: 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, Jeremy, Martin Knapp, and Julien Forder. 2006. Social Care and the Nonprofit Sector in the Western Developed World. In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sun Gap. 2017. How The 50 Plus Generation Live the Second Chapter of Life. Seoul: Hanvit Education. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. 2015. A Feasibility Study for the Establishment of the 50 Plus Foundation. Policy Report. Yeongi-gun: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jae Won. 2008. The Market and Consumer-Directed In-Home Care Service for the Elderly and the Korean e-Voucher System. Journal of Korean Association for Governance 15: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jong Soo. 2010. A Study on the Strategy of Korean Post-NPM Reform. Korean Society and Public Administration 21: 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, So Jung. 2013. Analysis on the Blind Zones of Elderly Welfare Services: Focusing on Social Participation Services. Journal of Korea Gerontological Society 33: 699–715. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Lawrence L., and Petter M. Kettner. 1996. Measuring the Performance of Human Service Programs. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. 2013. A Case Study of Policies to Promote the Employment of Those in Their 50s in OECD Member States. Seoul: Korean Women’s Development Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi, Terry, and Larry E. Davis. 1995. Social Welfare Policy. In Encyclopedia of Social Work. Edited by Richard L. Edwards. Washington: NASW Press, pp. 22262–37. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Guzmán, Carolina, Candice Fischer, Enrique Chia, and Catherine LaBrenz. 2015. Child Welfare in Chile: Learning from International Experiences to Improve Family Interventions. Social Sciences 4: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Kyoung-A. 2018. The 50-Plus Generation. Seoul: The Seoul Institute. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, Maeve. 2018. Existence and Resistance: The Social Model of Community Education in Ireland. Social Science 7: 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Yoon Jung, and Jin Yeol Nam. 2012. Analysis of Research Trends in Social Service Project Evaluation. Journal of Critical Social Welfare 37: 249–83. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Jae Ho. 2008. A Study on the Examination of the Change of Social Welfare Delivery System in Local Government. Journal of Korean Association for Governance 15: 139–64. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul 50 Plus Foundation. 2018. A Study on the Status of 50 Plus Policy Projects by Governments and Private Sectors in Korea and Abroad. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/innovative-government/Republic-of-Korea-case-study-UAE-report-2018.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Seoul Institute. 2015. The Establishment and Operation Plan of the 50 Plus Foundation. Seoul: Seoul Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Serre, Delphine. 2017. Class and Gender Relations in the Welfare State: The Contradictory Dictates of the Norm of Female Autonomy. Social Science 6: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, Rex Austin. 1983. Social Work Administration: Dynamic Management and Human Relationships. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Korea. 2017. Statistics Korea’s Estimated Future Population Trends in Cities and Provinces: 2015–2045; Daejeon: Statistics Korea.

- Sung, Gyu Tak. 1992. The Theoretical Framework of a Social Welfare Service Delivery System. Theological Forum 20: 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2017. World Population Aging 2017 Highlights Department of Economic and Social Affairs. New York: UN. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Mildred E., and Raymond Gradus. 2009. The Consequences of Implementing a Child Care Voucher: Evidence from Australia, the Netherlands and USA. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 09-078/3. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library, Available online: https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/2468698/09078.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2019).

- Whitaker, Gordon P. 1980. Coproduction: Citizen Participation in Service Delivery. Public Administration Review 40: 240–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Seo Jin, and In Ok Song. 2014. Factors Affecting Perceived Retirement Preparation of Babyboomers in Gyeongbuk Province. Journal of Rural Society 24: 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Nancy Fugate, and Marci Catanzaro. 1998. Nursing Research: Theory and Practice. Mosby: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ui Joo, Jo Eun Sook, Ko En Sook, and Ha Jung. 2016. A hermeneutic phenomenology study on the retirement experience of the baby boom generation. Korean Employment & Career Association 6: 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 1994. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).