Unveiling ‘European’ and ‘International’ Researcher Identities: A Case Study with Doctoral Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

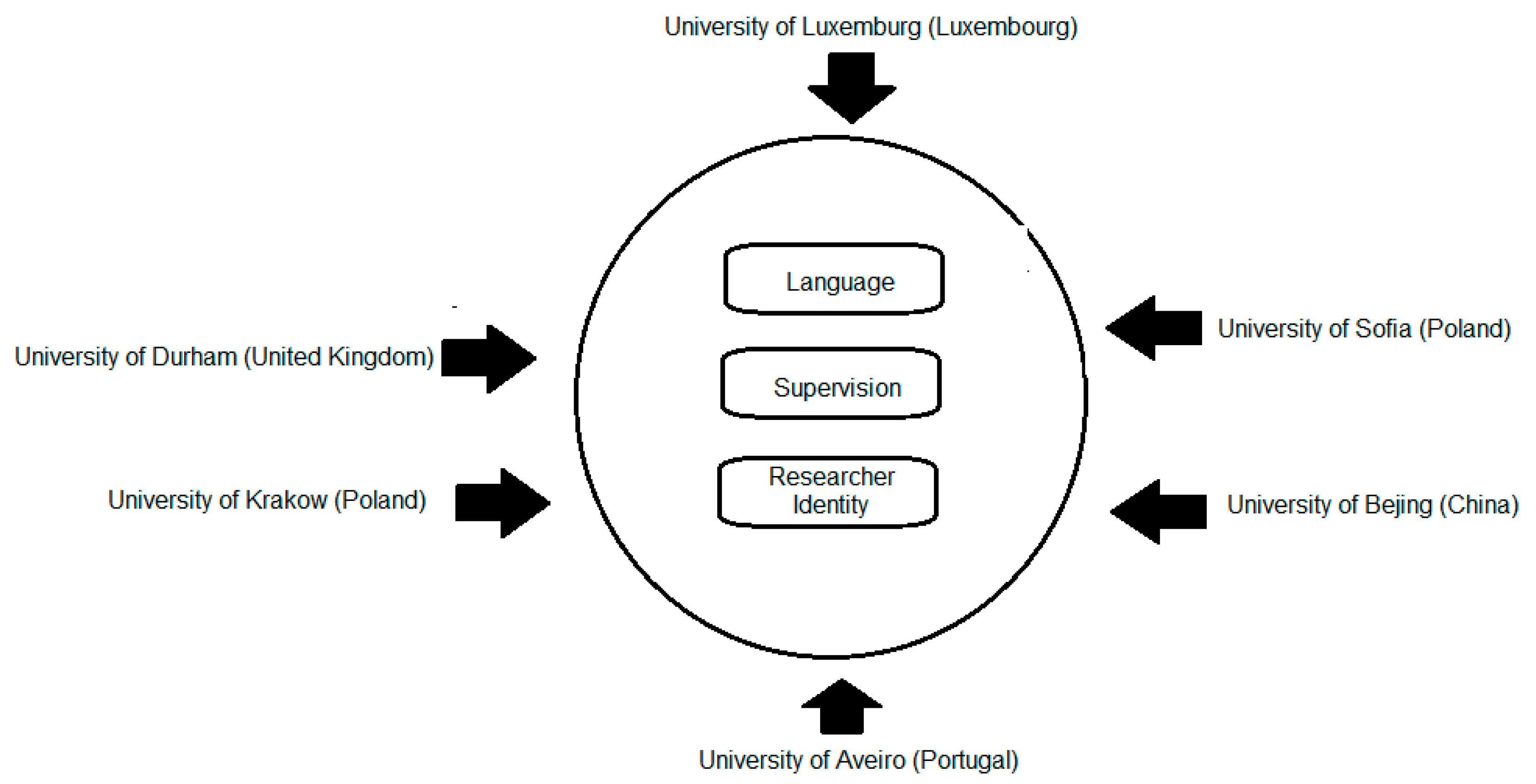

2. Doctoral Education at the University of Aveiro

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Factors Associated with the Construction of ‘European’ or ‘International’ Researcher Identities

4.1.1. Networking

Still, she recognizes that integration was a difficult process, as a result of cultural difference. Although she did not label the situations she was involved in as ‘discriminating’, she often felt that she had to prove herself as a researcher (and an academic) to be accepted by her colleagues. A similar feeling was expressed by S6, an international student and university teacher from Mozambique. Acknowledging initial difficulties in integrating into the group of doctoral students in Education, he explained that he had to work harder than his peers in order to overcome the (low) expectations some of his teachers and colleagues had of him, and get himself into a position where he could just be acknowledged and respected for his personal contributions:Because we are learning in groups, we have to deal with people of different backgrounds, of multiple disciplines … even of different cultures… it is a learning process… and this broadens our perspective, our point of view, contributing to our personal development. […] This helped me to take off my engineering persona, my conceptual framework, which was embedded in engineering, and I started to think within the framework of education.

Identical experiences have also been reported in previous studies conducted with international doctoral students (Archer 2008; Gardner 2008a; Sherry et al. 2010), and with those coming from Portuguese-speaking African countries (Ambrósio et al. 2017; Lopes and Diogo 2019). These studies suggest that students who do not fit the traditional mold of graduate education in the West (i.e., anyone other than young, white males) struggle to fit into academia, experiencing negative interactions with others and a general feeling of ‘differentness’. This tends to affect overall satisfaction and integration in the doctoral program, thus impairing the socialization process and the development of their self- and professional identities. Despite this, and considering the two previous quotes, curriculum-based programs sustained in a group work methodology seem to enhance networking opportunities and therefore play a crucial role in gradually helping students overcome hindrances and prejudice, thus acting as privileged places for broadening students’ perspectives, promoting intercultural dialogue and therefore fostering their sense of belonging to a broader research community.I think that I demand a lot of myself. But during the doctorate the demand I put on myself was bigger… to try to match the expectations […]. But after a while I think that my colleagues and I came to the conclusion that we had to work on an equal footing… And I think it is important to stress this: it’s good to work in a multicultural context…

The contact with her Swedish supervisor led her to take a short-term internship in one of the world’s leading medical institutions. This experience marked a turning point in her doctorate, allowing her to rethink the scope and relevance of her project: “that experience made me go deeper into my topic and determine the meaning that this line of research could have, not only locally but also internationally”.The possibility to work with so different people and to experience such different cultures, which seem distant but actually bring us closer, allows us to exchange knowledge and information… so they took advantage of our knowledge and we took advantage of their knowledge. This was the most rewarding aspect… having a project that was developed with people who are top experts in this area.

4.1.2. Doing What Researchers Do

This reinforces the importance of experiencing activities that are ‘automatically’ linked with an international scope of research during the PhD (Byram et al. 2017). For instance, reading in another language to become aware of previous research developed in one’s research field is considered by doctoral students to be mandatory. As S1 explains: “Nowadays, all PhDs have an international dimension, even if this is only related with the references used for the thesis”.We… as doctoral students … read and write a lot. And during these reading process, we are actually learning, isn’t it so? It is a process of learning a specific language, the thinking mode of that specific ‘tribe’. When I say that I would like to bring Mozambique to the research community … it is through the use of the specific language of that tribe… and I think that it is happening… I am learning to think and gather information in alignment with what is done in that specific community.

When it comes to publishing our work, we are aware of the need to internationalize. Whoever thinks that it is enough to stay in Portugal and publish locally is wrong.

However, for international students, coming from African Portuguese-speaking countries and East Timor, publishing in their home countries was particularly relevant. As stressed by S8, an international student and academic from East Timor, “we rarely write articles or organize seminars and discussions there”. Therefore, for these students, publications are seen a way to contribute to the advancement of research and teaching in their homeland.I think that publishing the results of our work is important… What can we bring to the research community that is interesting?

As regards attending conferences, only six out of twelve students mentioned that they had participated in events to disseminate their findings. Most of these events had a national scope, due to personal or financial constraints, as highlighted by S1:I would like to publish in Mozambique. […] And I hope that some of my ideas, disseminated through this medium, can influence the development of education in Mozambique, namely the teaching of chemistry.(S6)

For those students who had the chance to participate in international conferences, the gains seemed to extend beyond publications and peer recognition though. Recalling a conference that she attended in the United States, S11 stressed how interaction with other PhD students helped her understand the need to present herself in a more ‘professional’ way and to be more confident speaking up her own ideas:I participated in several seminars and conferences in Portugal. Unfortunately, I was unable to participate in an international conference that is one of the best in my area of research, which took place in Chile. I submitted a proposal, was accepted, but I was not able to get funding. And that conference would result in the publication of an international article, it was not a book of proceedings… It was a very good conference.

If we were going to a conference, they [my PhD colleagues] would present their business cards. They have business cards; here we don’t. […] So, they are aware […] of how important it is to brand ourselves and how important it is to present yourself in a professional way. Here in Portugal it’s different. […] I don’t want to offer stereotypes (we have to be careful with this), but we have to recognize that in Portugal we have this culture of being humble and sometimes… I mean you have to be aware of your own rights and speak about your own ideas, about your work and… to speak up your mind!

4.1.3. Mobility Experiences

For S11, being a visiting scholar in the United States and contacting with other researchers and academics allowed her not only to become more aware of international standards and of different working traditions among the American academia and the Portuguese academia, but also to reconsider her own identity as a researcher. When asked if she considered herself an international researcher, she answered:The summer school [in Denmark] was fundamental for me to rethink the meaning of doing a PhD. I remember that there was a teacher with whom I talked more often […] who told me the most interesting thing, which was… all PhD theses that were supervised by him had a personal first chapter, where people described how their individual process of doing a PhD was. And this made me think… I have been around this work for several years now… it is personal, it has to be personal… and this was when I decided to change the title of my thesis from plurilingual competences to plurilingual repertoires.

Researcher mobility, for instance the one supported by the Erasmus program, has also been identified as an important factor by the Luxembourg case of the EUROMEC project. According to Byram et al. (2017), mobility plans and agreements between different European universities and in different countries may contribute to creating an identify of a doctoral researcher in Europe. Nevertheless, while this may be a desirable output for European citizens, it may be problematic for students coming from other countries, in particular developing countries, as it will be highlighted in the following section.I certainly made my best to be an international researcher. All institutions have their strengths and weaknesses and having the possibility to be a visiting scholar in another institution makes you more aware of what you have in your own country and how research is done in your country, and how research is handled on the other side of the ocean, in my case. So, I think that’s quite important for all scholars.

4.2. Doctoral Students’ Researcher Identities: Four Profiles

Throughout the interview, it became clear that probably her age in combination with her initial motivations for doing a PhD, which were deeply tied with professional development in her working area, as well as the lack of mobility experiences or networking activities abroad, may have prevented her from developing a sense of self as a researcher (see Archer 2008).I don’t consider myself a researcher, because I do not have…I promised myself that I would not go back to studying… I have been enrolled 34 times as a student […] So I do not feel like a researcher or want to think about it now. Of course, I’m saying that I do not want to, but if something comes up that interests me… But not in this sense of yet another title, because it requires a lot of personal involvement.

This suggests that for these two students, whose main motivation in doing a PhD was grounded in professional development, the doctorate experience was not so much a foundation of an academic researcher career, but a means to become what Elsey (2007) describes as ‘knowledge worker’—a person with advanced training in research and a knowledge expert in the profession. This is clearly in tune with the new reality of doing a doctorate. Indeed, professional doctorates, which are consolidating in the areas of Natural Sciences and Engineering (Cardoso et al. 2019), are now becoming a popular alternative to PhDs in the Humanities and Social Sciences, particularly for teachers who are interested in applying research to their professional areas or designing effective practice within their own field (Araújo e Sá et al. 2019; Breganha et al. 2019).I do not know if I feel entirely like a researcher… I have my doubts. That’s because I have a foot in the business world, that’s my experience. In the business world is where I feel more at ease. And I think my foot is still more on that side than on the research side…

This intrinsic desire to contribute to the development of their countries led us to profile these students as ‘research ambassadors’, i.e., people who have experienced research abroad and want to share their knowledge with others for their mutual benefit. Curiously, for these three students being an ‘international’ researcher means to be aware of Portuguese standards, in particular of the methodological principles researchers in Portugal apply, and to bring this way of doing research to their academic institutions:At the professional level, it [the doctorate] will have an impact because I will have more knowledge about research, such as how to write an article. In East Timor, we rarely write articles or organize seminars and discussions. We still do not have a lot of research practice and I hope to start doing more of this with my colleagues there. We have new teachers and I have some plans to collaborate with them. I want to share my experience to incorporate them in this research dynamics.

The aspiration of these three international students in following ‘Portuguese standards’ and the emphasis on the idea that “all has to be similar” raises issues concerning the mainstreaming of Western knowledge and values (Nobes 2017; Santos 2003; Udoma et al. 2014). Therefore, this should be taken into account in doctoral programs in order to avoid that education for research contributes (even though unintendedly) to the phenomena of neo-colonialism (see, for instance, Stein et al. 2016; Lopes and Diogo 2019; Lopes forthcoming; Udoma et al. 2014).[In order to be of an international standard, the research I conduct] has to be similar to what is done in Portugal but studying in a different context. […] It has to be similar in terms of the demands, the references, the research methodologies, all of that has to be similar, only the context, the study environment is different […] This gives me the sense of being an international researcher.

S11 also assumed that she pursued ‘intercultural’ experiences while doing the doctorate for both personal and professional reasons:I did not have the chance to have an Erasmus experience… but I have always thought that it would be an asset for me, and for my work, to study abroad. So, I started searching and found ‘European Doctorate’ … so I looked for the requirements… and I discovered that there is a generic European recommendation… and then there are some specificities in each university.

These experiences abroad made her more conscious about the professional dimension of being a researcher and, curiously enough, allowed her to develop a sense of ‘Europeanness’, being this the only assumed case within the twelve students and the one more in tune with Evans (2010) model of European early career researchers. As she explains:Yes, I went to the US […] because there was a strong master’s program in International Education and my PhD research is situated in the field of International Education. So, I went for academic reasons. There was also a personal side to my stay in the United States, because, well… as I was saying, I was an exchange student before, and once you are an exchange student, you are an exchange student for life. So, you feel that need to go to another institution to know other ways of working and to know other cultures.

Finally, from the twelve interviewed students, S2 was the only one who expressed feeling like a full-fledged ‘international’ researcher. Having an international supervision team allowed her to establish her own international network of scholars with whom she still develops cutting-edge research. Furthermore, publishing in international journals and participating in international conferences contributed to her being recognized as an expert by her peers:I would rather consider myself a European researcher with some awareness of how research is done in the United States. I would say that I am a European researcher, because everything I research is about Europe, and I have some awareness, to some extent, of how research is being done in the United States.

When asked at the end of the interview how she imagined her future, she promptly answered that it would be the continuation of what she is presently doing—lecturing in a higher education institution, researching in an area that is recognized internationally, and including some of her students in her international network of collaborators, just like her supervisors did with her.Yes, I definitely feel like a researcher […] because now when there is a conference in my research domain, people easily identify me and say ‘Oh, there is a person in Aveiro who is working on this’.

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Schedule—Doctoral Students

Appendix A.1. International/European Identity

- -

- Does the phrase ‘international standards in doctoral work’ (or perhaps ‘European standards’) have meaning for you and, if so, can you explain how you understand it?

- -

- Do you know/how do you know if the work you are doing is of an ‘international standard’?

- -

- [if international or mobile student] Some people say that studying in another country creates a sense of being an ‘international’ researcher or a ‘European’ researcher. Does this describe in any way how you feel?

Appendix A.2. Identity as Researcher

References

- Ambrósio, Susana, João Filipe Marques, Lucília Santos, and Catarina Doutor. 2017. Higher education institutions and international students’ hindrances: A case of students from the African Portuguese-speaking countries at two European Portuguese universities. Journal of International Students 7: 367–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo e Sá, Helena, Nilza Costa, Cecília Guerra, Betina Lopes, Mónica Lourenço, and Susana Pinto. 2019. Case studies—University of Aveiro, Portugal. In The Doctorate as Experience in Europe and Beyond. Edited by Michael Byram and Maria Stoicheva. Abingdon: Routledge, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Louise. 2008. Younger academics’ constructions of ‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Studies in Higher Education 33: 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, Doutor Manuel António Cotão de. 2011. No. 6403/2011, approves the Regulation of the Doctoral School of the University of Aveiro, 14 April. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, Uwe, and Hans De Wit. 2015. The end of internationalization. International Higher Education 6: 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breganha, Graça M., Nilza Costa, and Betina Lopes. 2019. Avaliação sumativa das aprendizagens em Física no 1° ciclo do ensino secundário através de provas escritas—o caso de uma escola pública do município de Lubango (Angola) [Summative assessment of learning in Physics in the 1st cycle of secondary education through written tests—The case of a public school in the municipality of Lubango (Angola)]. Indagatio Didactica 11: 209–31. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael, Adelheid Hu, and Mizanur Rahman. 2017. Are researchers in Europe European researchers? A study of doctoral researchers at the University of Luxembourg. Studies in Higher Education 44: 486–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Sónia, Orlanda Tavares, and Cristina Sin. 2019. Can you judge a book by its cover? Industrial doctorates in Portugal. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Colbeck, Carol L. 2008. Professional identity development theory and doctoral education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 113: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, Sara. 2016. Changes in Finnish and Portuguese Higher Education Governance: Comparing National and Institutional Responses to the Bologna Process and New Public Management. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, Sara, and Teresa Carvalho. 2019. What am I doing here? Reasons for international students to enroll in a PhD in Portugal. Paper presented at the 13th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, March 11–13; pp. 4490–502. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, Sara, Anabela Queirós, and Teresa Carvalho. 2019. 20 years of the Bologna Declaration—A literature review on the globalization of Higher Education. Paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, July 1–3; pp. 5196–209. [Google Scholar]

- Elsey, Barry. 2007. After the doctorate? Personal and professional outcomes of the doctoral learning journey. Australian Journal of Adult Learning 47: 379–405. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2011. Towards a European Framework for Research Careers. Brussels: European Commission, Directorate General for Research and Innovation. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Linda. 2010. Developing the European researcher: ‘Extended’ professionality within the Bologna process. Professional Development in Education 36: 663–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Susan K. 2008a. Fitting the mold of graduate school: A qualitative study of socialization in doctoral education. Innovative Higher Education 33: 125–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Susan K. 2008b. ‘What’s too much and what’s too little?’ The process of becoming an independent researcher in doctoral education. Journal of Higher Education 79: 326–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Leigh A., and Leslie D. Burns. 2009. Identity development and mentoring in doctoral education. Harvard Educational Review 79: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Janet E. 2009. Developing a Doctoral Identity—A Narrative Study in an Autoethnographic Frame. Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu, Natal, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Jazvac-Martek, Marian, Shuhua Chen, and Lynn McAlpine. 2011. Tracking the doctoral student experience over time: Cultivating agency in diverse spaces. In Doctoral Education: Research-Based Strategies for Doctoral Students, Supervisors and Administrators. Edited by Lynn McAlpine and Cheryl Amundsen. London: Springer, pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kehm, Barbara M. 2004. Developing doctoral degrees and qualifications in Europe: Good practice and issues of concern—A comparative analysis. In Doctoral Studies and Qualifications in Europe and the United States: Status and Prospects. Edited by Jan Sadlak. Bucharest: UNESCO/CEPES, pp. 279–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kehm, Barbara M. 2007. Quo vadis Doctoral Education? New European approaches in the context of global changes. European Journal of Education 42: 307–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiley, Margaret. 2009. Identifying threshold concepts and proposing strategies to support doctoral candidates. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 46: 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Jane. 2004. Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education 8: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Betina, and Sara Diogo. 2019. Institutional challenges in monitoring and evaluating cooperation protocols between higher education institutions in Portuguese speaking countries. Paper presented at the 13th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, March 11–13; pp. 1563–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, Betina, Maria João Macário, Mariana Pinto, Maria Helena Ançã, and Maria João Loureiro. 2013. Learning transitions of three doctoral students in a Portuguese higher education institution facilitated by the use of ICT. International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Lifelong Learning 23: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Betina, Helena Pedrosa-de-Jesus, and Mike Watts. 2016. The old questions are the best: striving against invalidity in qualitative research. In Theory and Method in Higher Education Research. Edited by Jerome Huisman and Malcolm Tight. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, Betina. Forthcoming. As universidades públicas portuguesas e a capacitação na área da Educação em Ciências no âmbito da Cooperação Internacional para o Desenvolvimento: do mapeamento à sua problematização [Portuguese public universities and training in the field of science education in the context of international cooperation for development: from mapping to problematization]. Revista Lusófona de Educação.

- Lourenço, Mónica, Ana Isabel Andrade, and Michael Byram. Forthcoming. Representations of internationalisation at a Portuguese Higher Education Institution: From institutional discourse to stakeholders’ voices. Revista Lusófona de Educação.

- McAlpine, Lynn. 2012. Identity-trajectories: Doctoral journeys from past to present to future. Australian Universities’ Review 54: 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine, Lynn, Marian Jazvac-Martek, and Nick Hopwood. 2010. Doctoral student experience in Education: Activities and difficulties influencing identity development. International Journal for Researcher Development 1: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerad, Maresi. 2012. Conceptual approaches to doctoral education: A community of practice. Alternation 19: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nobes, A. 2017. Challenges Faced by Early Career Researchers in Low and Middle Income Countries—How can We Support Them? Available online: http://gheg-journal.co.uk/2017/01/challenges-faced-early-career-researchers-lmics-support/ (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- Parry, Sharon. 2007. Disciplines and Doctorates. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- PORDATA. 2019. Foreign Students Enrolled in Higher Education (ISCED 5–8) (2000–2012). Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/en/Europe/Foreign+students+enrolled+in+higher+education+(ISCED+5+8)+(2000+2012)-1313 (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Santiago, Rui, Teresa Carvalho, and Agnete Vabø. 2012. Personal characteristics, career trajectories and sense of identity among male and female academics in Norway and Portugal. In Effects of Higher Education Reforms: Change Dynamics. Edited by Martina Vukasović, Peter Maassen, Monika Nerland, Bjørn Stensaker, Rómulo Pinheiro and Agnete Vabø. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Boaventura Sousa. 2003. Reconhecer Para Libertar: os Caminhos do Cosmopolitanismo Multicultural. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, Mark, Peter Thomas, and Wing Hong Chui. 2010. International students: A vulnerable student population. Higher Education 60: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Sharon, Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti, and Rene Suša. 2016. ‘Beyond 2015′, within the modern/colonial global imaginary? Global development and higher education. Critical Studies in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoicheva, Maria, and Michael Byram. 2019. The Doctorate as Experience in Europe and Beyond. Abingdon: Routledge, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Virginia M., Christine Bruce, and Sylvia L. Edwards. 2016. Using grounded theory to discover threshold concepts in transformative learning experiences. In Theory and Method in Higher Education. Edited by Jeroen Huisman and Malcolm Tight. Bingley: Emerald, vol. 2, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Udoma, Ogenna, Sarah Glavey, Sarah O’Reilly Doyle Martina, Hennessy Frank Barry, Mike Jones, and Malcolm MacLachlan. 2014. Research Capacity Building in Africa: perceived strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats impacting on the doctoral training for development programme in Africa. In Enacting Globalization. Edited by Brennan Louis. London: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Weidman, John C., and Elizabeth L. Stein. 2003. Socialization of doctoral students to academic norms. Research in Higher Education 44: 641–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Student | Gender | Type of Student | Doctoral Program | Background Area | Scholarship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Female | Home student | Education | Math Education | Yes (FCT) |

| S2 | Female | Home student | Psychology | Psychology | Yes (FCT) |

| S3 | Female | Home student | Gerontology and Geriatrics | Social Work | No |

| S4 | Female | Home student | Education | Social Work | Yes (FCT) |

| S5 | Female | Home student | Multimedia in Education | Information Management | Yes (FCT) |

| S6 | Male | International student (Mozambique) | Education | Chemistry Education | Yes (Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua, I.P.) |

| S7 | Female | International student (East Timor) | Education | Math Education | Yes (East Timorese Government) |

| S8 | Female | International student (Brazil) | Education | Accounting, Language and Literature | Yes (FCT) |

| S9 | Female | International student (Ukraine) | Multimedia in Education | History and Psychology | No |

| S10 | Female | International student (Angola) | Education | Engineering | No |

| S11 | Female | Home student with mobility experience | Education | Language and Literature | Yes (FCT) |

| S12 | Female | Home student with mobility experience | Education | Adult Education and Educational Psychology | Yes (FCT) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopes, B.; Lourenço, M. Unveiling ‘European’ and ‘International’ Researcher Identities: A Case Study with Doctoral Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110303

Lopes B, Lourenço M. Unveiling ‘European’ and ‘International’ Researcher Identities: A Case Study with Doctoral Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(11):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110303

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopes, Betina, and Mónica Lourenço. 2019. "Unveiling ‘European’ and ‘International’ Researcher Identities: A Case Study with Doctoral Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences" Social Sciences 8, no. 11: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110303

APA StyleLopes, B., & Lourenço, M. (2019). Unveiling ‘European’ and ‘International’ Researcher Identities: A Case Study with Doctoral Students in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Social Sciences, 8(11), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110303