Abstract

A university education is often regarded as a means for increasing social mobility, with attendance at a leading university seen as a pathway to an advantaged socio-economic status. However, inequalities are observable in attendance levels at leading UK universities, with children from less advantaged backgrounds less likely to attend the top universities (generally known as the Russell Group institutions). In this paper, we explore the different levels of assistance provided to state school children in preparing for their university applications. Guidance teachers and pupils at a range of Scottish state schools were interviewed. We find that inequalities exist in the cultivation of guidance provided by state schools, with high attainment schools focusing on preparing applicants to be desirable to leading universities, whilst low attainment schools focus on persuading their students that university is desirable.

1. Introduction

Scotland has a long tradition of fostering university attendance, prioritising the right to fulfil educational aspirations as a cornerstone of the national identity (Keating 2005). The Curriculum for Excellence defines which student attributes universities should value and, therefore, what areas Scottish schools should emphasise in their curriculum (Scottish Government 2008). It dictates the minimum that schools must contribute to give all students an equal opportunity to apply to university. However, inequality in university attendance between those living in the most and least advantaged areas are wider in Scotland than elsewhere in the UK, whilst the proportion of privately educated undergraduates is growing at the oldest Scottish universities (Blackburn et al. 2016).

Within the UK, access to advantaged social positions are often disproportionally granted to graduates of leading universities1 (Hussain et al. 2009; Savage et al. 2013), with such institutions disproportionately recruiting students from advantaged backgrounds (Sutton Trust 2011; Boliver 2013, 2015). Thus, while higher education is often seen as a means of increasing social mobility (Goldthorpe 2003; Breen 2004), there are inequalities in who has access to university. Whilst the scale of over-representation of students from advantaged backgrounds has been well mapped (Sutton Trust 2004, 2007, 2009, 2011; Boliver 2013), there is less clarity as to how these inequalities are formed. Past research has highlighted that people’s social connections can influence their paths into higher education (Mangan et al. 2001; Mannion 2004; Fasang et al. 2014), which could, in part, explain such patterns.

In this paper, we ask what guidance is being given to Scottish state school students when they are considering applying for university and explore whether there are differences in the advice and help provided between schools. Thus, we explore the institutional advice and guidance provided to young people in Scottish state schools to examine the ways in which structures within schools can affect pupil’s chances of accessing university. Our focus extends beyond assistance with the actual application process to consider the cultivation of noneducational attributes, such as extracurricular activities and interests, which can also be important in a competitive application process (Zimdars et al. 2009; Shuker 2014).

2. Background

Social Mobility and Education

Education is often considered a fundamental mechanism for increasing meritocracy (Goldthorpe 2003; Breen 2004). Goldthorpe (2003) argues that acceptance into higher employment is increasingly based on qualifications, and this represents a transition towards a legitimate education-based meritocracy. Further, he argues (2013) that society has become increasingly technologically focused, thus the demand for trained personnel has increased. This necessitates the expansion of the education system and, therefore, increased opportunities for access to higher education, which coincides with increased university attendance (Breen 2004; Morgan-Klein 2003). However, this increased engagement with higher education can itself be stratified. Marginson (2016) showed that although there is a global trend towards increased engagement with higher education, middle and high income countries still have the highest gross tertiary enrolment by world region when compared to lower income countries. Further, Triventi’s (2011, p. 499) analysis of 11 European countries found that ‘individuals with better educated parents have a higher probability of attaining a degree from a top institution, of a higher standard, and with better occupational returns’.

Despite a long-standing commitment in the UK to facilitate fair access to university, dating as far back as the Robbins Report (NCIHE 1963) and continued, more recently, through the AimHigher programme (DfES 2003) and Curriculum for Excellence (Scottish Government 2008), there remains an under-representation of students from disadvantaged positions in universities generally, and the leading institutions in particular (Boliver 2013; Zimdars et al. 2009; Kelly and Cook 2007; Blanden and Machin 2004; Blackburn and Jarman 1993). In Scotland, the effect of area deprivation on the outcomes of school leavers is stark; in 2016/17, just 25% of school leavers from the most deprived areas entered higher education compared to 41% nationally and 61% in the least deprived areas (Scottish Government 2018). Those from lower socio-economic groups are less likely to apply to, and consequently enter, the more ‘prestigious’ higher education institutions in the UK than students with the same grades from more advantaged backgrounds (Boliver 2013). Furthermore, state school pupils2, more generally, are less likely to participate in higher education than those from independent schools (Sutton Trust 2009) and are profoundly under-represented in more prestigious universities (Sutton Trust 2011). Boliver (2013) found students from fee-paying schools had a higher likelihood of being accepted to Russell Group universities than state school pupils with the same grades, with the increased acceptance rates equating to having an additional A grade at A-level3. In addition to this, children from lower income families experience feelings of stigma and low self-esteem due to their financial circumstances, which in turn affects their wellbeing and educational outcomes (Sime et al. 2015). These factors all contribute to the under-representation of state school pupils at the top UK universities.

These well-documented differences in acceptance rates between schools (Ball 1997; Sutton Trust 2011; Boliver and Swift 2011) has led policymakers to focus on strategies for increasing representation of a diverse cohort within universities. The Scottish Government, for instance, introduced the Curriculum for Excellence (Scottish Government 2008), which dictates that schools are required to provide all pupils with an equal opportunity to apply for university. This includes flexibility in learning, introducing a greater range of pathways to university and creating a supportive mechanism for potential applicants. Despite these aims, schools alone cannot provide pupils with sufficient human capital to access the top universities. Social capital can be viewed as the pool of resources that reside within other people, such as educational skills and training, which we do not already have ourselves (Bourdieu 1986). Further, whilst schools can assist with gaining entry qualifications, they are perhaps less equipped to generate the personal skills or ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu 1984), which are essential to producing personal statements that appeal to university admissions officers (Shuker 2014). Habitus refers to the cultural capital engrained in the knowledge, tastes, mannerisms and experience that help shape the way people act and empower individuals to feel accepted within social worlds (Bourdieu 1984). This is exemplified by Vincent and Ball’s (2007) study where they explored the difference between working class and middle class families preparing their children for school. They found that middle class parents were more likely to prepare their children for school through organised “enrichment activities”, which entailed a number of costly classes and activities (Vincent and Ball 2007, p. 1074). Middle-class children were more likely to be engaged with a number of activities, which aided them in their accumulation of cultural and social capital, unlike working class children, even at pre-school age. Additionally, evidence suggests that not only are additional travel and equipment costs excluding children from more deprived areas in Scotland (McKendrick 2014) but children from more deprived areas also have less access to leisure space, including parks and playgrounds, and are more likely to perceive these areas as unsafe (Scottish Government 2014). However, habitus is not only cultivated through the family and extracurricular activities, as shown, but also through the school system.

Khan’s (2011) ethnographic account of an elite US boarding school describes the cultivation of an Ivy League identity amongst pupils, providing not only the educational qualifications for accessing top-tier universities but also the cultural capital required to be accepted by members of elite social groups. He argues that the habitus moulded in elite schools will give their students a greater advantage in society and in elite higher education because their knowledge, tastes and mannerisms have been legitimised by the education system (Bourdieu 1984). Therefore, students from elite schools are not only more likely to be accepted to elite universities but also more likely to apply for them. Many contemporary UK analyses contend that people from advantaged backgrounds are more able to ease into advantaged positions (Savage 2015; Savage et al. 2013), receive higher pay for doing the same jobs as people from other backgrounds (Friedman et al. 2015) and adapt to advantaged lifestyles without experiencing negative emotional reactions related to the loss of their earlier, less privileged social identity (Friedman 2013).

Personal statements are a central component of university application decisions. Zimdars et al. (2009) found cultural knowledge was deemed more important than arts participation when applying to non-science subjects at Oxford, suggesting that appreciation, rather than exposure, was considered valuable. In medical schools there are conflicting levels of importance applied to student’s personal statements, with some acknowledging the potential for bias and therefore disregarding them (Parry et al. 2006). This question of recruiter bias complicates the issue of fair access. Although universities are committed to ensuring a larger in-take of pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, such statements enable a transparent mechanism of creating an uneven application process. Guidelines for accepting students onto prestigious courses become the criteria for accessing human capital (Bourdieu 1990) and thus the valuing of particular experiences and tastes can subtly encourage the acceptance of students from particular backgrounds. The Russell Group (2013) openly concentrate on students who have undertaken particular traditional academic subjects for their entry qualifications, making these details public to encourage appropriate subject choices amongst students from schools that offer alternative courses. There is no such guidance on the types of cultural capital individuals can foster to aid their applications.

Shuker (2014) explored the differences in representations of self in personal statements, providing case study analysis of applications from an independent school, a comprehensive and a further education college. She observed that the institution attended was the major difference between students who actively enriched their personal statements with activities and skills and those who did not. She observed students of independent schools actively enriching their personal statements with activities and skills that would appeal to universities. Personal statements are a means to self-market oneself and display the traits most desirable to universities. However, the ‘self’ that students were marketing was only one representation of ‘many possible identity projections’ (Shuker 2014), and these projections varied depending on one’s habitus. Thus, the independent school was able to help their students to self-market themselves to the universities. This supports Khan’s (2011) claim that independent schools act as hives of habitus cultivation in addition to being sites of learning.

Shuker (2014) contrasted the views of independent pupils who considered extracurricular activities to be essential for building the cultural capital to generate strong personal statements with those from further education courses, viewing them as either applicable only to failing students or being unobtainable due to noneducational commitments, such as paid employment. Whilst there is an emphasis on fair access within UK higher education, it is plausible that habitus provides a mechanism that discriminates against pupils from less advantaged backgrounds. Given that many disadvantaged students perceive top universities as being attended by fee-paying, rich, white students (Hutchings and Archer 2001; Reay et al. 2001; Mangan et al. 2001), this feeling of habitus could dissuade aspirations, undermine applications and produce insecurities for individuals feeling distant from their social worlds.

Whilst there is much focus on the division between independent and state schools (Dunne et al. 2014; Boliver 2013; Ball 1997), less focus has been applied to the distinctions between state school pupils. Forty per cent of state school teachers would rarely or never advise students to apply to Oxford or Cambridge, partly due to the complexity of the application process (Sutton Trust 2016) and a lack of understanding in how admissions tutors evaluate personal statements (Jones 2016).

Mangan et al. (2001) describes three forms of influence on whether pupils attend university: their parental background, their schools and local labour market conditions. Whilst local employment opportunities should be consistent amongst all school leavers within a local authority, in reality, opportunities vary both in terms of the adult networks that students have developed and the resources available from their school. Fasang et al. (2014) argue that pupils whose parents have poorer educational backgrounds are doubly disadvantaged as their parents’ social networks will be less likely to include people with strong educational skills and values. This can be reinforced by schools being located within communities that might have higher (or lower) levels of graduates, meaning parents are brought together with others from a similar socio-educational position (Small et al. 2008). Parents can therefore develop an unconscious tendency towards providing effective advice only in career options related to their own socio-economic positions through their knowledge of these areas (Mannion 2004). Similarly, the correct habitus can be cultivated more readily by parents who already embody those cultural tastes and experiences (Khan 2011; Kosunen and Seppänen 2015).

Schools provide an invaluable mechanism for exposing pupils to information. Many schools and educational projects attempt to foster aspiration and attainment of higher education (Hopkins 2006; Maguire et al. 2011; Donnelly 2014). This can include displaying posters throughout the school to normalise students towards university (Maguire et al. 2011), inviting former pupils who attend leading universities to speak to potential applicants (Donnelly 2014) and the provision of summer schools to provide greater insight into university life (Hopkins 2006). Such schemes exist to encourage pupils to both apply and feel that they are part of universities they might perceive as the habitat of fee-paying pupils. The role of guidance teachers is also a vital component of this process as they provide advice and support on accessing future career and educational options (Mannion 2004). While these processes may serve to mitigate the dislocation of disadvantaged pupils, it has the potential to focus university advice in schools upon aspiration rather than the means of attainment, namely, by developing the cultural and educational capital necessary to construct a strong application. However, in the UK, there remains a large inequality in educational performance between schools (Ball 2010), with some state schools achieving both better average results and more pupils attending university. Thus, further exploration into the processes and provisions utilised by state schools to aid their students with their university application is needed to fully understand the differences between state schools. This is especially true regarding the guidance provided to state schools students to develop their habitus and thus increase their chances of both applying and being accepted into university.

In this paper, we aim to explore the differences in provision of university application assistance across state schools in central Scotland. This is particularly important in Scotland as it has the largest disparity in university attendance between students coming from the most and the least deprived areas in Scotland when compared to anywhere else in the UK (Blackburn et al. 2016). We identify the forms of help that schools provide to their pupils to explore contrasting patterns of assistance to understand how these strategies can address inequalities in applications. Scotland offers an interesting focus for this analysis due to its comprehensive school system, which offers no distinctions between state schools (Croxford 2001).

3. Research Methods

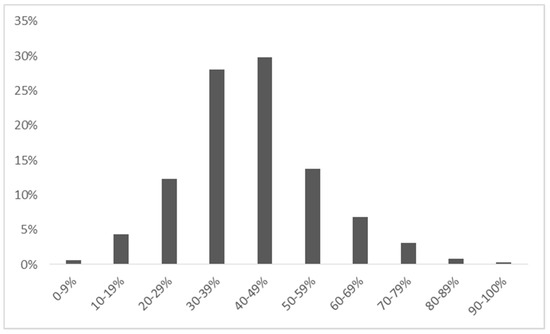

Interviews were conducted with nine teachers across six Scottish state schools in January 2015. These schools reflected a range of educational levels and were geographically diverse, as shown in Table 1. Schools were initially contacted though communications with administrative staff to establish the relevant contact for university applications, which was usually guidance teachers. In two instances, schools indicated that a team of teachers were responsible for applications and in these instances, each teacher was interviewed individually. Pseudonyms have been used and attainment levels banded into groups to prevent identification of which schools were studied. As Figure 1 shows, Scottish schools typically see between 30% and 55% of pupils achieve three Level 6 qualifications (the standard entry requirement for leading UK universities). Schools included in the study were selected across a range of attainment levels to reflect a range of schools that were more or less advantaged. Attainment and advantage, in the UK context, are highly correlated (Goodman and Gregg 2010; Andrews et al. 2017) and thus attainment is used as a proxy for advantage in schools.

Table 1.

Schools interviewed (attainment is the number of pupils with 3+ level 6 awards in 2014/15).

Figure 1.

Attainment levels of Scottish schools (percentage of pupils with 3+ level 6 awards in 2014/15).

Interviews were also conducted with 25 young people, attending 18 different schools, at a university open day at a Central Scotland institution in October 2014. Short five-minute interviews were conducted through convenience sampling between sessions arranged by the university for potential applicants. Interviews focused on where young people were receiving the most help and advice for making their university decisions, whether that was from their school or from elsewhere, and which source of information they were most reliant on or found the most resourceful. The interviews also explored what information and resources schools were providing the young people to help them with their university decisions and if there were particular events, people or resources that had been particularly helpful. Interviewing at a university open day allowed the researcher to interview a larger number of young people, from a great range of state schools, over a short period of time. In six cases, the young people attended alongside family members, who were also included in the interviews. These school pupils were based across Scotland and attended an educationally diverse range of state schools, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Attainment level of schools of pupil interviewees (percentage of pupils attaining 3+ level 6 awards in 2014/15).

This paper begins by examining the differences between schools and the narratives of the application process according to guidance teachers. It then looks at the perceptions of students in regard to the guidance they received from their schools.

4. Results

4.1. Preparing for University

For many state school pupils, university is perceived to be a natural progression after completing secondary education. Teachers in schools with a historically high number of university applicants often commented on the preparedness of pupils for the application process and defined their role as facilitating a smooth progression through the application process. Some teachers described the ‘knowing’ of both what the pupils wish to do at university and how to access those positions. Teachers remarked that students were planning and preparing for university through subject choices made in the second and fourth year when the pupils are typically aged 13/14 and 15/16, respectively. As one teacher put it:

When it gets to 6th year [final year of secondary school], they should already be knowing, they should already have an idea of what they want to do at university.(Creel Community High, high attainment school)

The teachers in the best performing schools were aware that their pupils had spent their secondary education developing not only the qualifications to apply to university but also the attributes necessary to stand out as a candidate. Thus, students were not only prepared in their subject choices, but also in their choices of extra-curricular activities. One teacher stated:

They all sing in the choir, they all play in the orchestra, all the boys play a sport, play an instrument, all have part time jobs.(Samuel High, high attainment school)

The route into higher education was not perceived as short-term assistance provided at the application stage but a long-term process of developing the habitus of an appealing persona throughout a student’s school career.

This ongoing process of preparation enabled schools to provide personalised guidance during the application process. Resources embedded within the parent and wider community were also tapped, with members of the local community brought in to discuss their time at university and provide detailed information about particular institutions. This supports Fasang et al.’s (2014) assessment that people from advantaged backgrounds benefit not only from parental support but also from the support of their advantaged social circles. Part of this process involved preparing pupils for mock interviews, irrespective of whether they would be necessary. This produced a spirit of planning that left pupils feeling prepared for their application and, undoubtedly, feeling ready to embark on university education. As one guidance teacher explained:

Well, usually in the November in-services, erm … an Acting Deputy now runs mock interviews and a whole load of external partners, eh … kinda business partners and parents who run businesses and they come in over the course of the day and interviews anybody who is in 5th or 6th year (years when applying to university) who has signed up to be interviewed. Eh … and quite often those are people who have applied to university who are never going to have interviews.(Creel Community High, high attainment school)

Such interviews take place while students are in the process of submitting applications and writing their personal statements. These interviews enable students to ascertain which of their qualities and experiences are most appealing to professional workers, enhancing their ability to demonstrate their possession of habitus. If Russell Group institutions are selecting candidates based on the quality of their personal statements, these processes of developing the correct lifestyle and generating dialogue with professionals may increase the likelihood of acceptance. Such processes were only evident in schools with the highest attainment levels.

4.2. Persuading towards University

Whilst the teachers within high attainment schools saw their roles as working with the local community to ease young people into university, many teachers in the lower attainment schools expressed their role as working against the community to encourage educational aspiration. Teachers from schools with low educational attainment often discussed how social inequalities interact with educational aspiration, producing cohorts of students lacking the motivation or social support to pursue higher education. Teachers often saw their role as providing the support to encourage pupils to apply. As one teacher explained:

In this area there are not a lot of people who have gone to university, most are in [deprivation] decile one and two. Lots of issues with unemployment, so for a lot of the children here they do not have the conversations at home about going to university that other people have. And we have to provide that for them.(Kennedy Community High, low attainment school)

Many teachers mentioned a lack of understanding of the university system amongst parents, reinforced by the profile of the communities producing few social ties where such information could be obtained. For instance, teachers brought up issues about parental knowledge of funding issues or qualities required to enter into university as areas that many parents were unaware of and thus they discourage their children. For instance:

They don’t know if it’s for them. They don’t know if it’s getting above their stations. They don’t want their children to fail so they think maybe they shouldn’t apply.(Bayside High, low attainment school)

I’ve had parents phone me saying ‘You’ve been speaking to my child about university y’know I can’t afford that’. And I’m the person who has to have the conservation to say we can look at funding.(Slater High, low attainment school)

Teachers acknowledged that parents were not trying to deprive their children of a university education but merely lacked the knowledge and experience required to provide effective guidance on the subject. Rather, parents provide advice on areas they are more familiar with, leading to a reproduction of aspirations, with teachers seeing it as their role to provide information about university life:

They [parents] don’t mean to be [a barrier to university entry] but they also have deprivation of aspiration and we have y’know. As an example, I spoke to someone in second year [age 13/14] … I asked them about subjects they’re going to take and I’ve looked at what level they’re at. And I can see they’re at the top decile for academic and they tell me they want to be a nail technician. And I say well, why do you want to be a nail technician, you could go to university. And they go, y’know ‘What? Why me?’ And we need to work on that. But you’re working against a lot of gender stereotyping in the area … In terms of subjects they pick, they go for pink jobs, blue jobs and that comes from the parents.(Kennedy Community High, low attainment school)

Thus, guidance teachers at low attainment schools are often concentrating upon developing the aspiration to go to university, rather than developing a persona that may be attractive to Russell Group institutions. Several teachers commented on the development of aspiration across the lifetime of the pupil’s secondary education, often having to fight against community influences, even at later stages of the schooling. Thus, teachers concentrate on building aspirations rather than personas, not only at the point of application but throughout the student’s education. Whilst teachers can influence student’s self-perception within the school, they are unable to influence their relationships within the community and, therefore, must adopt strategies to mediate the advice pupils receive. One teacher discussed the timing of their residential team-building week:

The fact that we do it straight after the holidays isn’t a coincidence. It’s because they’ve been in their home environments and we want to refocus them with ‘when you are in this building you aim high, when you’re in this building you be all you can be’. And we say that, we say that to the students in our school.(Kennedy Community High, low attainment school)

The teachers frequently mentioned support agencies that helped develop educational aspirations in their pupils. All of the low attainment schools had connections to third sector organisations and programmes that aim to increase participation in higher education, such as Lothian Equal Access Programme for Schools, Lift Off to Learning and Sutton Trust schemes. The fact that they enabled access to workshops, talks, trips to universities and residential weeks were appreciated by the teachers and viewed as important steps towards increasing participation. These programmes also provided mentors who met regularly with students, providing advice on university life and processes. Whilst this provides young people with greater access to knowledge, the focus is often on getting students to connect to people out with their communities. Unlike the fostering of habitus observed within the high attainment schools, many teachers discussed the necessity to develop pupils from looking inwardly within their community:

The kids are constrained in many, many ways and that’s an important one, because they see themselves as a part of a very small community, not part of a big community.(Slater High, low attainment school)

There’s still a culture that if you live in [area 1] you don’t go into [area 2] and if you live in [area 2] you don’t go into [area 1]. Y’know the smaller areas […] within our catchment area a lot of our parents and grandparents have never really ventured outside the small area in our catchment area, let alone to a different part of the city. And so, we really need to battle against this kind of insular [thinking].(Bayside High School, low attainment school)

A number of our young people see a trip in the centre as a trip to the end of the earth. We organised a trip to Bayside to use their gymnastic facilities and we had a few kids who were amazed at a sheep in a field, because they had never seen a real farmyard animal in life before.(Bayside High School, low attainment school)

Students were often portrayed as disconnected from wider society and developing habitus amongst deprived communities rather than more advantaged social groups. While teachers in high attainment schools perceived their role as cultivating persona, in the lower attainment schools, teachers stressed the importance of giving pupils glimpses of an alternative community and sought to raise aspiration levels to access such social worlds. Thus, rather than focusing on providing the practical experience to appeal to Russell Group institutions, guidance teachers spent their time fighting to make those universities appeal to their students.

The same themes, and limitations, were brought up by the teachers at the lower attainment schools, with a sense that the demographics of where the children lived, which were usually areas of relative deprivation, produced a series of challenges that they were forced to fight against. This contrasted with the interviews of teachers from the higher attainment schools who saw the communities the children grew up in as easing their way into higher education.

4.3. Student’s Perception of Institutional Guidance

Interviews were conducted with 25 school pupils at a university open day. Students were, unanimously, appreciative and supportive of what resources and information their school gave to them. Comments focused on the application process itself, for example, the assistance they received with personal statements and any resources they were given access to, rather than acknowledging development and support throughout their schooling.

All students were content with the services provided by their school, with all welcoming helpful feedback on the drafts of their personal statements which they believed would improve their chances of being offered university places. Typical comments included:

Mrs Smith does the personal statements for the whole year. She’s looking at my UCAS [personal] statement. I did a draft a couple of weeks ago so she’s looking it over. She’ll give me suggestions.(Kelly, 47% attainment school)

We had a session in one of our PSE [Personal, Social and health Education] lessons about the whole process… personal statements stuff like that. […] They gave us a brief outline of what should be in it [the personal statement] and we’ve done some drafts.(Fiona, 71% attainment school)

However, inequalities in provision were observable between schools. The structural delivery of support at high attainment schools clashed with the chaotic provision from low attainment schools. This is nicely illustrated by two quotes in particular, which demonstrate the levels of preparation shown to pupils by schools.

The school put on an open day where they gave out books [prospectuses] … and they let you ask about the different unis.(Bryan, 52% attainment school)

Interviewer: How did you find out about today’s open day?Chris: Online.Interviewer: Okay. Did your school give you any other information about other open days?Chris: Not really. No.[…]Interviewer: So what about your school? Have they put on any events or information days about coming to university or applying to university?Chris: No.(Chris, 38% attainment school)

This is unlikely to be due to disengagement of schools from the university process but rather a reaction to the multitude of stressors that occur within low attainment schools. This was illustrated whilst undertaking the research, with interviews at the high attainment schools being easily arranged, whereas interviews conducted at lower attainment schools were often delayed due to guidance teachers reacting to incidents that occurred in school that day. These differences in daily structures could provide unequal levels of assistance to pupils. Applicants were asked if they felt that there was an unequal distribution of support within their school and between different schools, with pupils generally perceiving an equality of provision. However, this was not unilaterally the case, as one pupil from a lower attainment school explained that students at a neighbouring school ‘got extra information on how to apply and stuff’ [Tori, 39% attainment school], a comment her parents, who worked there, attested.

Students from lower attainment schools were more likely to find information about the open day online or from other friends. Most acknowledged that they had not heard about the open day through their schools, and it was usually down to their own initiative or personal networks that they had gathered this information. Students remarked:

[gestures at two friends] It was these two that told me about it [the open day]. School didn’t have anything about open days.(Laura, 38% attainment school)

My school didn’t give me any dates about the open day. It was my dad that told me this one was on today.(Rhonda, 34% attainment school)

This inequality in provision of information meant pupils from the lower attainment schools were more reliant upon their personal networks for advice and information. This is particularly disadvantageous as low attaining schools are often situated within communities where access to such knowledge is uncommon. Several pupils mentioned relying on guidance from their social connections, often from people with either a singular or limited viewpoint. Students with siblings at university often gained information from them, viewing information provided as ‘biased, but a good source’ [Ben, 45% attainment school]. Students only perceived their parents as good sources of advice if they were themselves graduates or were in a professional job, further disadvantaging many students living in the lowest areas of deprivation. Family ties were viewed as advantageous by those pupils attending high attainment schools and were described as valuable sources of information for their pupils. Inequalities, therefore, are compounded by family ties that operate as a further advantage to those who are often already in high attainment areas but that are largely absent for those students for whom it might be most advantageous.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has demonstrated several distinctions in the type of support provided to students by different state schools in Scotland. State schools with pupils entering with the highest levels of habitus were able to nurture those personas and provide access to a multitude of resources that served to ease students into university. This has the potential to create further divisions in acceptance rates over those generated through other forms of educational inequality. Fasang et al. (2014) argued that children of people with low educational attainment are often doubly disadvantaged because not only can their parents offer only limited assistance with their learning, but family friends also often lack the skills to effectively assist with homework. We extend this idea to argue that schoolchildren within disadvantaged communities are sometimes additionally disadvantaged when applying to university as their parents and family friends also lack sufficient habitus to negotiate applications to leading universities.

We found no evidence of guidance teachers differing in their commitment, ability or attitudes between schools, nor did we find that attainment levels were predominately associated with the quality or failings of the school overall. Rather, we observed that different pressures on the school and the guidance teachers were associated with relative deprivation and educational attainment drew guidance teachers’ time towards raising aspirations rather than providing skills associated with successful applications to the most competitive institutions.

Whilst there is plentiful evidence that prestigious institutions recruit a disproportionately small number of applicants from less advantaged backgrounds, even if achieving similar grades, there is less knowledge of how such discrepancies occur. It is plausible that the quality of persona the student presents within their personal statement could contribute towards this inequality (Shuker 2014; Khan 2011). Within the most advantaged schools, there was a long-term commitment to actively build the skills that institutions desired and undertake one-to-one interviews to ensure the personal statement was pitched correctly, with strong applications demonstrating an appropriate habitus. Amongst the most deprived communities, there was evidence of a long-term ‘battle’ by teachers to foster student aspirations and encourage them to reach their potential. This appears to lead to teachers focusing on persuading students to apply, rather than preparing them longer term to be desirable. Given these pupils are often located within insular communities, which appear ‘detached’ from the more advantaged social worlds, and lack the dialogue required within the home to foster a professional voice, it is plausible this influences inequalities in the application level. Whilst there is evidence that schemes to support students into university are appreciated by both pupils and teachers (Hopkins 2006; Donnelly 2014), it appears these replace, rather than compliment, provisions to nurture potential applicants to develop their personal statements. Our research supports and extends the work of Shuker (2014), elucidating the evidence of a distortion between those guidance teachers who are able to support the development of a persona and those only assisting the writing of the personal statement existing within the state sector. Thus, the debate on fair access should not focus exclusively on the selection processes within the university sector but also within schools. The socio-economic environment that surrounds each school serves to shape the way guidance teachers construct their place within the application process. Therefore, the impact of socio-economic inequalities within education will generally become more pronounced within local authorities if schools focus their resources on where they are most useful. However, there are perhaps practical aspects of the guidance provided within higher attainment schools that may be applicable to those with lower attainment. For example, interview preparation could be administrated at local authority level, thereby removing part of the burden from schools and mitigating the effects of unequal provision. Indeed, it is this question of how busy guidance teachers might best focus their efforts that proves to be one of the most pertinent outcomes of this study. All pupils attending university open days appreciated the rich support they received from their guidance teachers. This differs fundamentally from Mannion’s (2004) findings a decade earlier that school leavers generally feel negated and disillusioned by the support they received. Given the tendency for teachers to discuss changing attitudes developed at home, further consideration of how the home environment impacts on those unwilling to attend university would be welcome. There is strong engagement between lower attainment schools and third sector or university-led programmes aimed to boost higher education participation, which is welcome. However, if the Scottish Government’s Curriculum for Excellence is truly to provide all state school pupils with equal access, then strategies should be provided to schools from within the public sector, whether at governmental or local authority level, to allow schools similar abilities to foster the habitus to appeal to leading universities rather than relying on minimum standards and ignoring the additional inputs plausible from schools that have fewer distractions on teachers’ time.

Naturally, this is a small-scale study from which convincing conclusions cannot be reached. However, it serves to demonstrate the important role of personal statements and in-school guidance, which should be further analysed to determine potential creation of inequalities between social groups. Little is known of the mechanisms underpinning differences in university acceptance rates, and this evidence suggests that inequalities are introduced not only at the point of the students’ application being received but also at the point of its preparation, a process which spans all years of secondary state schooling. Given the potential impact of these factors, we argue that further investigation is warranted if progress towards education-based meritocracy is to be achieved.

Author Contributions

Data curation, J.F. and D.G.; Formal analysis, J.F.; Methodology, J.F. and D.G.; Writing—original draft, J.F. and D.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews, Jon, David Robinson, and Jo Hutchinson. 2017. Closing the Gap? Trends in Educational Attainment and Disadvantage. London: Education Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Stephen. 1997. Good School/Bad School: Paradox and fabrication. British Journal of Sociology of Education 18: 317–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Stephen. 2010. New class inequalities in education: Why education policy may be looking in the wrong place! Education policy, civil society and social class. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 30: 155–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, Robert M., and Jennifer Jarman. 1993. Changing Inequalities in Access to British Universities. Oxford Review of Education 19: 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, Lucy Hunter, Gitit Kadar-Satat, Sheila Riddell, and Elisabet Weedon. 2016. Access in Scotland: Access to Higher Education for People from Less Advantaged Backgrounds in Scotland. London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Blanden, Jo, and Stephen Machin. 2004. Educational Inequality and the Expansion of UK Higher Education. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 51: 230–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2013. How Fair is Access to More Prestigious UK Universities? British Journal of Sociology 64: 344–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2015. Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics on Widening Access to Russell Group Universities. Radical Statistics 113: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Boliver, Vikki, and Adam Swift. 2012. Do Comprehensive Schools Reduce Social Mobility? The British Journal of Sociology 62: 88–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. Homo Academicus. Bristol: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Richard. 2004. Social Mobility in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Croxford, Linda. 2001. School Differences and Social Segregation: Comparison between England, Wales and Scotland. Education Review 15: 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- DfES. 2003. The Future of Higher Education; London: HMSO.

- Donnelly, Michael. 2014. Progressing to University: Hidden Messages at Two State Schools. British Educational Research Journal 41: 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, Máiréad, Russell King, and Jill Ahrens. 2014. Applying to Higher Education: Comparisons of Independent and State Schools. Studies in Higher Education 39: 1649–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasang, Anette Eva, William Mangino, and Hannah Brückner. 2014. Social Closure and Educational Attainment. Sociological Forum 29: 137–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Sam. 2013. The Price of the Ticket: Rethinking the Experience of Social Mobility. Sociology 48: 352–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Sam, Daniel Laurison, and Andrew Miles. 2015. Breaking the ‘Class’ Ceiling? Social Mobility into Britain’s Elite Occupations. The Sociological Review 63: 259–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldthorpe, John. 2003. The Myth of Education-based Meritocracy: Why the Theory Isn’t Working. New Economy 10: 234–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Alissa, and Paul Gregg. 2010. Poorer Children’s Educational Attainment: How Important Are Attitudes and Behavior? York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Peter E. 2006. Youth Transitions and Going to University: The Perceptions of Students Attending a Geography Summer School Access Programme. Area 38: 240–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Iftikhar, Sandra McNally, and Shqiponja Telhaj. 2009. University Quality and Graduate Wages in the UK. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4043. Bonn: IZA. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, Merryn, and Louise Archer. 2001. ‘Higher than Einstein’: Constructions of Going to University amongst Working-class Non-participants. Research Papers in Education 16: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Steven. 2016. Making a Statement. In Sutton Trust Research Brief. London: Sutton Trust, September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Keating, Michael. 2005. Higher Education in Scotland and England after Devolution. Regional and Federal Studies 15: 423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Kathryn, and Stephen Cook. 2007. Full-time Young Participation by Socio-Economic Class: A New Widening Participation Measure in Higher Education. Nottingham: Dfes Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Shamus Rahman. 2011. Privilege: The Making of an Adolescent Elite at St. Paul’s School. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosunen, Sonja, and Piia Seppänen. 2015. The Transmission of Capital and a Feel for the Game: Upper-class School Choice in Finland. Acta Sociologica 58: 329–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Meg, Kate Hoskins, Stephen Ball, and Annette Braun. 2011. Policy Discourses in School Texts. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32: 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangan, Jean, Nick Adnett, and Peter Davies. 2001. Movers and Stayers: Determinants of Post-16 Educational Choice. Research in Post-Compulsory Education 6: 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, Greg. 2004. Education and learning for social inclusion. In Youth Policy and Social Inclusion: Critical Debates with Young People. Edited by Monic Barry. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, Simon. 2016. The Worldwide Trend to High Participation Higher Education: Dynamics of Social Stratification in Inclusive Systems. Higher Education 72: 413–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendrick, John, Gerry Mooney, John Dickie, and Peter Kelly. 2014. Poverty in Scotland. London: Children Poverty Action Group. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Klein, Brenda. 2003. Scottish Higher Education and the FE-HE Nexus. Higher Education Quarterly 57: 338–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCIHE. 1963. Report of the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education; London: HMSO.

- Parry, Jayne, Jonathan Mathers, Andrew Stevens, Amanda Parsons, Richard Lilford, Peter Spurgeon, and Hywel Thomas. 2006. Admissions Processes for Five Year Medical Courses at English Schools: Review. BMJ 332: 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reay, Diane, Jacqueline Davies, Miriam David, and Stephen J. Ball. 2001. Choices of Degree or Degrees of Choice? Class, ‘Race’ and the Higher Education Choice Process. Sociology 35: 855–74. [Google Scholar]

- Russell Group. 2013. Informed Choices. London: Russell Group. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, Mike. 2015. Social Class in the 21st Century. London: Pelican. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, Mike, Fiona Devine, Niall Cunningham, Mark Taylor, Yaojun Li, Johs Hjellbrekke, Brigitte Le Roux, Sam Friedman, and Andrew Mile. 2013. A New Model of Social Class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey Experiment. Sociology 47: 219–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. 2008. Curriculum for Excellence: Building the Curriculum 3; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2014. Scotland’s People Annual Report: Results from 2013 Scottish Household Survey; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2018. Initial Destinations of Senior Phase School Leavers; No. 2: 2018 Edition; Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Shuker, Lucie. 2014. ‘It’ll look good on your personal statement’: self-marketing amongst university applicants in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sociology of Education 352: 224–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sime, Daniela, Joan Forbes, and Jennifer Lerpiniere. 2015. Poverty and Children’s Education. Glasgow: The Scottish Universities Insight Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Mario Luis, Erin M. Jacobs, and Rebekah Peeples Massengill. 2008. Why Organisational Ties Matter for Neighbourhood Effects: Resource Access through Childcare Centers. Social Forces 87: 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton Trust. 2004. The Missing 3000: State School Students Under-Represented at Leading Universities. London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. 2007. University Admissions by Individual Schools. London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. 2009. Applications, Offers and Admissions to Research Led Universities. London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. 2011. Degree of Success—University Chances by Individual School. London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton Trust. 2016. Sutton Trust Research Brief. London: Sutton Trust, October 2. [Google Scholar]

- Triventi, Moris. 2011. Stratification in Higher Education and Its Relationship with Social Inequality: A Comparative Study of 11 European Countries. European Sociological Review 29: 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, Carol, and Stephen J. Ball. 2007. ‘Making up’ the Middle-class Child: Families, Activities and Class Dispositions. Sociology 41: 1061–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdars, Anna, Alice Sullivan, and Anthony Heath. 2009. Elite Higher Education Admissions in the Arts and Sciences: Is Cultural Capital the Key? Sociology 43: 648–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | There is no consistent categorisation of ‘leading UK universities’, with a multitude of metrics and league tables ranking UK universities differently. Often the self-selecting Russell Group is used, but it does exclude institutions which would usually be considered as ‘leading’, such as St Andrews. We use the label of ‘leading universities’ in this paper more as meaning prestigious without taking a position on any specific universities nor a number of institutions covered by the term. |

| 2 | State schooling is provided free of charge by the government and is available for all children from the age 5 until they are 18. Alternatively, independent schools (also known as private schools) will charge fees to attend and are not provided by the government. |

| 3 | UK undergraduate university applications are processed through the same system, irrespective of whether in the devolved Scottish educational system. Boliver’s results compared the advantage to entry qualifications within the English, rather than Scottish, system. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).