Commuting Stress–Turnover Intention Relationship and the Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis of Turkish Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptualization

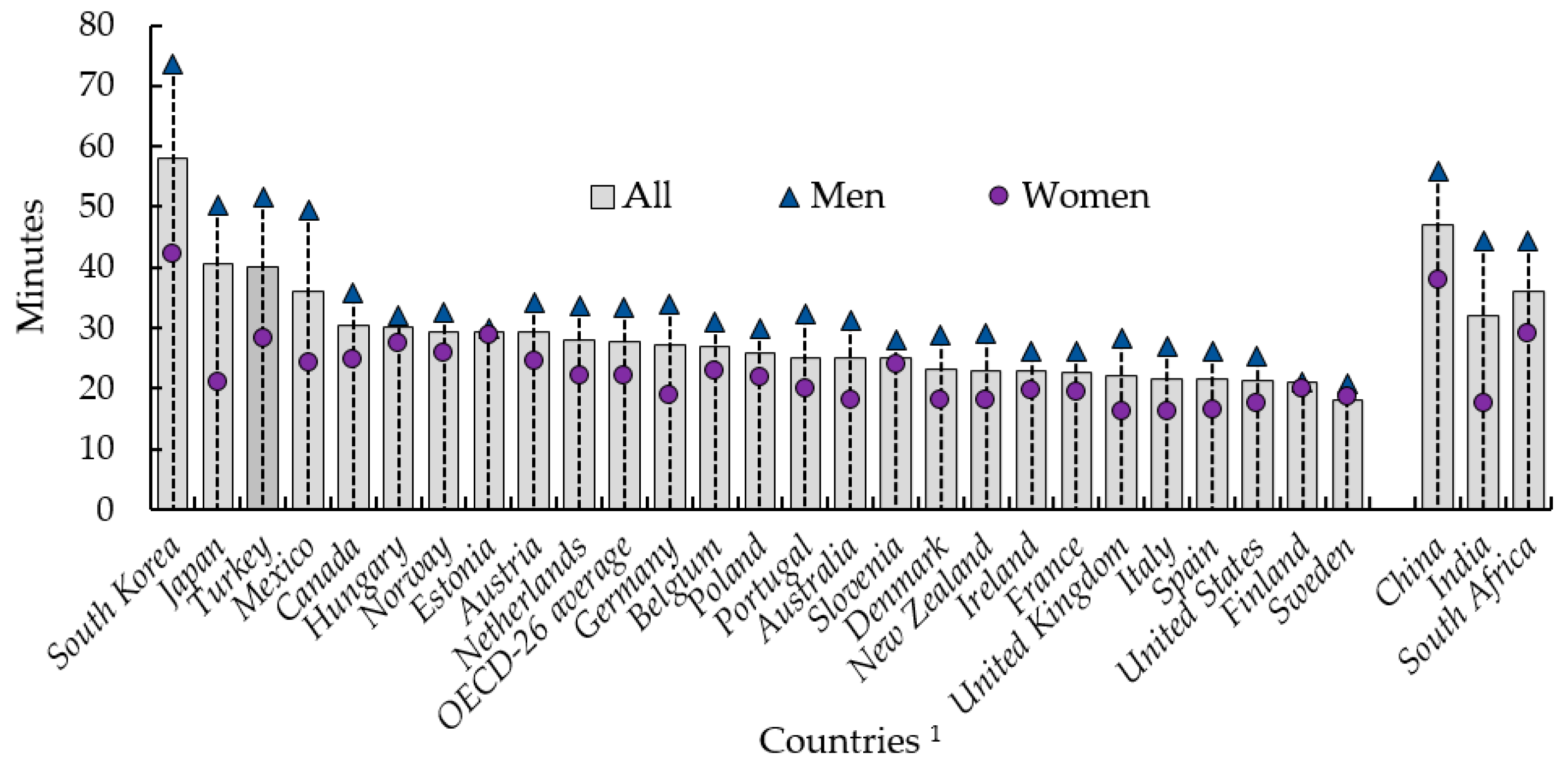

2.1. Commuting Stress

2.2. Commute Spillover into Turnover Intention

2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.4. Demographic and Atmospheric Factors

3. Methodological Framework

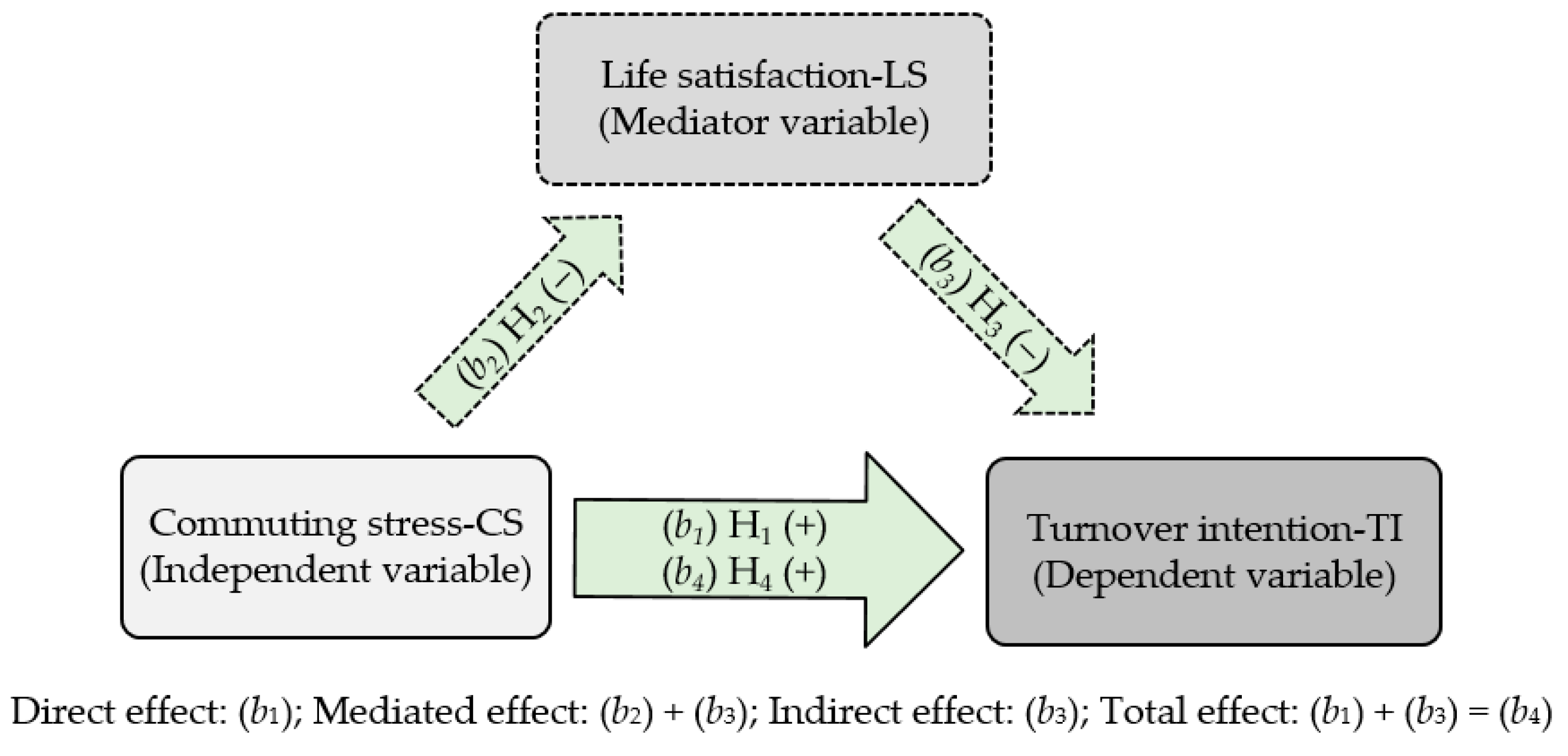

3.1. Hypotheses and Model Development

3.2. Participants and Survey Design

3.3. Measures and Properties

3.3.1. Employees’ Commuting Stress (CS)

3.3.2. Employee Turnover Intention (TI)

3.3.3. Employee Life Satisfaction (LS)

4. Analysis Procedure and Results

4.1. ANOVA and Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

4.3. Validation of Mediation Effect

5. Conclusions and Implications

6. Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiken, Leona S., Stephen G. West, and Raymond R. Reno. 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Akgunduz, Yilmaz, and Ovunc Bardakoglu. 2017. The impacts of perceived organizational prestige and organization identification on turnover intention: The mediating effect of psychological empowerment. Current Issues in Tourism 20: 1510–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, Kerstin, Amanda D. Shantz, Catherine Truss, and Emma C. Soane. 2012. The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24: 330–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Natalie J., and John P. Meyer. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology 63: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah-Tawiah, Kwesi, Francis Annor, and Beckham G. Arthur. 2016. Linking commuting stress to job satisfaction and turnover intention: The mediating role of burnout. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health 31: 104–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoux-Nicolas, Caroline, Laurent Sovet, Lin Lhotellier, Annamaria Di Fabio, and Jean-Luc Bernaud. 2016. Perceived work conditions and turnover intentions: The mediating role of meaning of work. Frontiers in Psychology 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluedorn, Allen C. 1982. A unified model of turnover from organizations. Human Relations 35: 135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutus, Stéphane, Roshan Javadian, and Alexandra Joelle Panaccio. 2017. Cycling, car, or public transit: A study of stress and mood upon arrival at work. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 10: 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. 2010. From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 178–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hao, David L. Ford, Gurumurthy Kalyanaram, and Rabi S. Bhagat. 2012. Boundary conditions for turnover intentions: Exploratory evidence from China, Jordan, Turkey, and the United States. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 23: 846–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Seonghee, Misty M. Johanson, and Priyanko Guchait. 2009. Employees intent to leave: A comparison of determinants of intent to leave versus intent to stay. International Journal of Hospitality Management 28: 374–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Galia, Robert S. Blake, and Doug Goodman. 2016. Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration 36: 240–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costal, Giovanni, Laurie Pickup, and Vittorio Di Martino. 1988. Commuting—A further stress factor for working people: Evidence from the European community. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 60: 377–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, John L., and Jeffrey M. Tuttle. 1986. Employee turnover: A Meta-analysis and review with implications for research. The Academy of Management Review 11: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, Özge. 2017. The effect of vocational training/education activities on employee leaving tendency in organisations: A survey-based research on practices in Turkey. Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences 16: 1014–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, Alper. 2014. Influences of HR practices, social exchange, and trust on turnover intentions of public IT professionals. Public Personnel Management 43: 140–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, Dick, Margareta Friman, Lars E. Olsson, and Tommy Gärling. 2017. Season and weather effects on travel-related mood and travel satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, Gary W., and Richard E. Wener. 2006. Rail commuting duration and passenger stress. Health Psychology 25: 408–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Zhiqiang, and Paul Boyle. 2014. Do long journeys to work have adverse effects on mental health? Environment and Behavior 46: 609–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Andy. 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Filiz, Zeynep. 2014. An analysis of the levels of job satisfaction and life satisfaction of the academic staff. Social Indicators Research 116: 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, Lucy, David J. Mellor, Kathleen A. Moore, and Claude Loquet. 2004. How can managers reduce employee intention to quit? Journal of Managerial Psychology 19: 170–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiselli, Richard, Joseph M. La Lopa, and Billy Bai. 2001. Job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and turnover intent among food-service managers. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 42: 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Piyali, Rachita Satyawadi, Jagdamba P. Joshi, and Mohd Shadman. 2013. Who stays with you? Factors predicting employees’ intention to stay. International Journal of Organizational Analysis 21: 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Peter M. 1999. Predicting employee life satisfaction: A coherent model of personality, work, and nonwork experiences, and domain satisfactions. Journal of Applied Psychology 84: 564–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy, Dwight A. 2008. The impact of commuter stress on workplace aggression. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38: 2315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, Brooks C., Terence R. Mitchell, Thomas W. Lee, and Marion B. Eberly. 2008. Turnover and retention research: A glance at the past, a closer review of the present, and a venture into the future. The Academy of Management Annals 2: 231–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, Peter W., Thomas W. Lee, Jason D. Shaw, and John P. Hausknecht. 2017. One hundred years of employee turnover theory and research. Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 530–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igbaria, Magid, Guy Meredith, and Derek C. Smith. 1994. Predictors of intention of is professionals to stay with the organization in South Africa. Information & Management 26: 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Chan Su. 2010. Predicting organizational actual turnover rates in the U.S. federal government. International Public Management Journal 13: 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hansung, and Madeleine Stoner. 2008. Burnout and turnover intention among social workers: Effects of role stress, job autonomy and social support. Administration in Social Work 32: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koslowsky, Meni, Avraham N. Kluger, and Mordechai Reich. 1995. Commuting Stress: Causes, Effects, and Methods of Coping. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann, Bernd, Rayna Sariyska, Christopher Kannen, Maria Stavrou, and Christian Montag. 2017. Commuting, life-satisfaction and internet addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Jooa Julia, Francesca Gino, and Bradley R. Staats. 2014. Rainmakers: Why bad weather means good productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology 99: 504–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, David P., Amanda J. Fairchild, and Matthew S. Fritz. 2007. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology 58: 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maden, Ceyda, and Hayat Kabasakal. 2014. The simultaneous effects of fit with organizations, jobs and supervisors on major employee outcomes in Turkish banks: Does organizational support matter? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25: 341–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Thomas N. 1979. A contextual model of employee turnover intentions. The Academy of Management Journal 22: 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masum, Abdul K. Muhammad, Abul K. Azad, Kazi E. Hoque, Loo-See Beh, Peter Wanke, and Özgün Arslan. 2016. Job satisfaction and intention to quit: An empirical analysis of nurses in Turkey. PeerJ 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, William H., Rodger W. Griffeth, Herbert H. Hand, and Bruce M. Meglino. 1979. A review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin 86: 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, Donald P., and Sanjay K. Pandey. 2008. The ties that bind: Social networks, person-organization value fit, and turnover intention. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18: 205–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Better Life Index. 2018. Available online: http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- OECD Family Database. 2018. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Olsson, Lars E., Tommy Gärling, Dick Ettema, Margareta Friman, and Satoshi Fujii. 2013. Happiness and satisfaction with work commute. Social Indicators Research 111: 255–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PageGroup. 2018. Transport and Commute Survey. Available online: https://www.pagepersonnel.ch/news-and-research-centre/studies/transport-commute-survey (accessed on 10 February 2018).

- Pasupuleti, Sudershan, Reva I. Allen, Eric G. Lambert, and Terry Cluse-Tolar. 2009. The impact of work stressors on the life satisfaction of social service workers: A preliminary study. Administration in Social Work 33: 319–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2012. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 539–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, Robert W., Janet P. Near, and Raymond G. Hunt. 1980. The job-satisfaction/life-satisfaction relationship: A review of empirical research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 1: 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Cecil, and Randall E. Schumacker. 2009. Interaction Effects: Centering, Variance Inflation Factor, and Interpretation Issues. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints 35: 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, Joseph C. 2004. Job satisfaction and life satisfaction revisited: A longitudinal test of an integrated model. Human Relations 57: 1205–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Jason D. 1999. Job satisfaction and turnover intentions: The moderating role of positive affect. The Journal of Social Psychology 139: 242–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Jason D., John E. Delery, G. Douglas Jenkins, and Nina Gupta. 1998. An organization-level analysis of voluntary and involuntary turnover. The Academy of Management Journal 41: 511–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobel, Michael E. 1982. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology 13: 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, Sandra, and Sara Leroi-Werelds. 2016. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. European Management Journal 34: 618–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, Robert P., and John P. Meyer. 1993. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology 46: 259–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S. Arzu. 2003. Organizational commitment, turnover intentions and the influence of cultural values. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 76: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Stephen G., John F. Finch, and Patrick J. Curran. 1995. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Edited by Rick H. Hoyle. Newbery Park: Sage, pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Michael. 2005. Bootstrapped confidence intervals as an approach to statistical inference. Organizational Research Methods 8: 454–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Alternatively, mediation studies have been also using structural equation modeling, which combines factor analyses, path diagrams, and a system of linked regression equations to capture complex and dynamic relationships within a web of observed and unobserved (latent) variables that can simultaneously be both dependent and independent variables. In our case, because there were only three variables and a clear distinction existed between the dependent and independent variables with causal relationships rather than casual linkages, the hierarchical regression analysis was more appropriate. |

| 2 | This vacation congestion is another cause of the increase in the CS of summer workers, especially in coastline cities. |

| Aspect | Statement | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Payment | The money paid to employees for the services and values they add. | − |

| Integration | Having close friends and good relationships with colleagues at work. | − |

| Internal communication | The extent to which employees have efficient and sustained communication with colleagues at work. | − |

| External communication | The extent to which employees have efficient and sustained communication with their counterparts in other organizations. | + |

| Centralization | The extent to which organizational decisions are often made by employers or by empowered and privileged several managers. | + |

| Routinization | The extent to which job-related responsibilities are repetitive. | + |

| Distributive justice | The prevalence of a merit and performance-based promotion system. | − |

| Upward mobility | The possibility and availability of movement between different status and career levels in organizations. | − |

| Job satisfaction | The extent to which employees are satisfied with what they do. | − |

| Work commitment | The extent to which employees feel committed to their work. | − |

| Occupational status | The extent to which employees hold occupational status. | − |

| Aspect | Statement | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunity | The availability of alternative occupational roles and job opportunities offered by other organizations in the working environment | + |

| Social networks | Intra-organizational social network | − |

| Inter-organizational social network | + | |

| Social/community networks | + | |

| Commuting | Location of work (distance to home) | + |

| Location of home (distance to work) | + | |

| Length of service | The time that employees have been working at the company | − |

| Age | Elder employees are more inflexible and thus loyal to their organizations | − |

| Education and training | Although more educated and trained employees are expected to be more flexible, education and training qualifications should be considered | + |

| Gender and marital status | Should be considered together with other demographics and cultural values | +/− |

| Work type | The effects of working as blue or white collar are inconclusive | +/− |

| Commuting Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving alone | Carpooling | Public transportation | Walking | Bicycle/motorcycle | Telecommuting | Total |

| 100 | 41 | 39 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 214 |

| 47% | 19% | 18% | 10% | 1% | 5% | 100% |

| Round-trip duration of commuting (in minutes) | ||||||

| 20− | 20–40 | 40–60 | 60–80 | 80–100 | 100+ | Total |

| 48 | 42 | 50 | 34 | 19 | 21 | 214 |

| 22% | 20% | 23% | 16% | 9% | 10% | 100% |

| Category | Group | No. of Businesses (and %) (1) | No. of Respondents (and %) (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business sector | Manufacturing | 16 (55) | 113 (53) |

| Service | 7 (24) | 60 (28) | |

| Trade | 6 (21) | 41(19) | |

| Location (City) | İstanbul | 14 (48) | 110 (51) |

| Ankara | 5 (17) | 36 (17) | |

| İzmir | 4 (14) | 29 (14) | |

| Adana | 2 (7) | 13 (6) | |

| Antalya | 2 (7) | 14 (7) | |

| Mersin | 2 (7) | 12 (6) | |

| Business size (no. of total employees) | Small: 5–19 | 7 (24) | 20 (9) |

| Medium: 20–99 | 11 (38) | 79 (37) | |

| Large: 100+ | 11 (38) | 115 (54) |

| Category | Group | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–29 | 42 | 20 |

| 30–39 | 69 | 32 | |

| 40–49 | 60 | 28 | |

| 50+ | 43 | 20 | |

| Gender | Male | 135 | 63 |

| Female | 79 | 37 | |

| Marital status | Single(1) | 71 | 33 |

| Married | 143 | 67 | |

| Number of children | None | 83 | 39 |

| 1 | 41 | 19 | |

| 2 | 62 | 29 | |

| 3 and more | 28 | 13 | |

| Formal education level | Elementary school degree | 24 | 11 |

| High school degree | 79 | 37 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 83 | 39 | |

| Master’s degree | 18 | 8 | |

| Doctoral degree | 10 | 5 | |

| Time in current job (job tenure) | 2 years or less | 36 | 17 |

| 3–5 years | 66 | 31 | |

| 6–8 years | 54 | 25 | |

| 9 or more years | 58 | 27 | |

| Time at company (organizational tenure) | 5 years or less | 78 | 36 |

| 6–10 years | 80 | 37 | |

| 11 or more years | 56 | 26 | |

| Job status | Permanent | 186 | 87 |

| Contract | 28 | 13 | |

| Managerial position | White collar(2) | 119 | 56 |

| Blue collar(3) | 95 | 44 |

| Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| It takes me longer than necessary to commute to work in the morning. | 0.83 |

| It takes me longer than necessary to commute back home after work. | 0.80 |

| I am unable to avoid heavy traffic on my way to work. | 0.72 |

| I am unable to avoid heavy traffic on my way back home after work. | 0.76 |

| I have to leave home earlier than I would like because of traffic congestion. | 0.68 |

| Traffic congestion is a frequent inconvenience. | 0.65 |

| My journey to and from work is often interrupted by traffic signals. | 0.71 |

| I am not satisfied with my journey to and from work. | 0.80 |

| My journey to and from work is unpleasant. | 0.87 |

| I worry about my journey to and from work due to traffic accidents. | 0.66 |

| Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| If I had the chance, I would be working for another organization. | 0.83 |

| I will probably look for other organizations to work for in the near future. | 0.77 |

| I have never thought of leaving this organization(1). | 0.84 |

| I feel a ‘strong’ sense of belonging to my organization(1). | 0.75 |

| I feel ‘emotionally attached’ to this organization(1). | 0.79 |

| I am loyal to this organization(1). | 0.73 |

| I really feel as if this organization’s problems are my own(1). | 0.69 |

| Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| In general, I am satisfied with my housing expenditure and my dwelling’s basic facilities. | 0.68 |

| In general, I am satisfied with my earning. | 0.73 |

| In general, I am satisfied with my job quality. | 0.55 |

| In general, I am satisfied with my social networks. | 0.58 |

| In general, I am satisfied with my education. | 0.70 |

| In general, I am satisfied with my environment regarding water quality and air pollution. | 0.63 |

| In general, I am satisfied with the services provided by the local governmental institutions. | 0.52 |

| In general, I am satisfied with the health services I am offered. | 0.59 |

| In general, I am happy with my life. | 0.79 |

| In general, I feel I am safe in my dwelling area. | 0.68 |

| I think I can efficiently balance my working and personal lives. | 0.77 |

| Groups | CS | LS | TI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean(1) | F | p | Mean(1) | F | p | Mean(1) | F | p | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male (n:135) | 3.27 | 7.25 | 0.00 (5) | 3.99 | 1.93 | 0.17 | 3.48 | 0.86 | 0.36 |

| Female (n:79) | 3.68 | 3.78 | 3.34 | ||||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single (n:71) | 3.21 | 11.59 | 0.00 (5) | 3.96 | 3.14 | 0.07 (3) | 3.52 | 4.95 | 0.03 (4) |

| Married (n:143) | 3.74 | 3.80 | 3.31 | ||||||

| Age | |||||||||

| 20–29 (n:42) | 3.28 | 11.43 | 0.00 (5) | 3.73 | 3.83 | 0.014 | 3.47 | 0.28 | 0.83 |

| 30–39 (n:69) | 3.20 | 3.76 | 3.40 | ||||||

| 40–49 (n:60) | 3.58 | 3.95 | 3.36 | ||||||

| 50+ (n:43) | 3.82 | 4.09 | 3.42 | ||||||

| Number of children | |||||||||

| None (n:83) | 3.20 | 12.35 | 0.00 (5) | 3.85 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 3.44 | 0.21 | 0.80 |

| 1–2 (n:103) | 3.63 | 3.82 | 3.38 | ||||||

| 3 and more (n:28) | 3.58 | 3.96 | 3.42 | ||||||

| Commuting type (2) | |||||||||

| Driving alone (n:100) | 3.46 | 2.92 | 0.04 (4) | 3.89 | 0.19 | 0.90 | 3.59 | 2.84 | 0.04 (4) |

| Carpooling (n:41) | 3.39 | 3.86 | 3.36 | ||||||

| Public transportation (n:39) | 3.70 | 3.83 | 3.41 | ||||||

| Other (n:34) | 3.32 | 3.92 | 3.30 | ||||||

| Commuting duration | |||||||||

| <20 (n:48) | 2.94 | 35.70 | 0.00 (5) | 3.87 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 3.42 | 2.81 | 0.03 (4) |

| 20–40 (n:42) | 2.91 | 3.76 | 3.17 | ||||||

| 40–60 (n:50) | 3.48 | 3.94 | 3.48 | ||||||

| 60–80 (n:34) | 3.83 | 3.99 | 3.45 | ||||||

| 80+ (n:40) | 4.21 | 3.87 | 3.59 | ||||||

| Group Pair | Means | Q Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | CS | ||

| (20–29) vs. (40–49) | (3.28) vs. (3.58) | 3.48 | 0.07 (2) |

| (20–29) vs. (50+) | (3.28) vs. (3.82) | 5.88 | 0.00 (4) |

| (30–39) vs. (40–49) | (3.20) vs. (3.58) | 5.01 | 0.00 (4) |

| (30–39) vs. (50+) | (3.20) vs. (3.82) | 7.51 | 0.00 (4) |

| Age | LS | ||

| (20–29) vs. (50+) | (3.73) vs. (4.09) | 3.94 | 0.03 (3) |

| (30–39) vs. (50+) | (3.76) vs. (4.09) | 4.02 | 0.02 (3) |

| No. of children | CS | ||

| (None) vs. (1–2) | (3.20) vs. (3.63) | 6.85 | 0.00 (4) |

| (None) vs. (3 and more) | (3.20) vs. (3.58) | 4.04 | 0.01 (3) |

| Commuting type | CS | ||

| (Carpooling) vs. (Public transportation) | (3.39) vs. (3.70) | 3.33 | 0.09 (2) |

| (Public transportation) vs. (Other modes) | (3.70) vs. (3.32) | 3.83 | 0.04 (3) |

| Commuting type | TI | ||

| (Driving alone) vs. (Other modes) | (3.59) vs. (3.30) | 3.41 | 0.08 (2) |

| Commuting duration | CS | ||

| (20−) vs. (40–60) | (2.94) vs. (2.91) | 6.22 | 0.00 (4) |

| (20−) vs. (60–80) | (2.94) vs. (3.83) | 9.24 | 0.00 (4) |

| (20−) vs. (80+) | (2.94) vs. (4.21) | 13.78 | 0.00 (4) |

| (20–40) vs. (40–60) | (2.91) vs. (3.48) | 6.34 | 0.00 (4) |

| (20–40) vs. (60–80) | (2.91) vs. (3.83) | 9.29 | 0.00 (4) |

| (20–40) vs. (80+) | (2.91) vs. (4.21) | 13.71 | 0.00 (4) |

| (40–60) vs. (60–80) | (3.48) vs. (3.83) | 3.67 | 0.08 (2) |

| (40–60) vs. (80+) | (3.48) vs. (4.21) | 8.02 | 0.00 (4) |

| (60–80) vs. (80+) | (3.83) vs. (4.21) | 3.79 | 0.06 (2) |

| Commuting duration | TI | ||

| (20–40) vs. (80+) | (3.17) vs. (3.59) | 4.53 | 0.01 (3) |

| (20–40) vs. (40–60) | (3.17) vs. (3.48) | 3.46 | 0.10 (2) |

| First Survey (Conducted in Winter) | Second Survey (Conducted in Summer) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | LS | TI | CS | LS | TI | |

| Mean | 3.32 (1) | 3.93 | 3.38 | 3.63 | 3.84 | 3.46 |

| Maximum | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 | 7.00 |

| Minimum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Std. Dev. | 1.52 | 1.39 | 1.73 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.68 |

| Skewness | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.51 |

| Kurtosis | 2.55 | 2.42 | 2.27 | 2.67 | 2.49 | 2.31 |

| CS | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| LS | −0.27 (2) | 1.00 | −0.33 (2) | 1.00 | ||

| TI | 0.44 (3) | −0.29 (2) | 1.00 | 0.51 (3) | −0.34 (2) | 1.00 |

| Observations (N) | 214 | 214 | ||||

| Model | Causal Path | Standardized Coefficient (1) | Constant | F | R2 | Durbin–Watson Stat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CS→TI | 0.53 (0.07) [7.72] (2) | 1.56 (0.26) [5.95] (2) | 59.61 | 0.22 | 1.78 |

| 2 | CS→LS | −0.28 (0.07) [4.30] (2) | 4.83 (0.25) [19.35] (2) | 18.49 | 0.08 | 1.82 |

| 3 | LS→TI | −0.32 (0.08) [−4.30] (2) | 4.71 (0.31) [15.14] (2) | 18.48 | 0.08 | 1.62 |

| 4 | CS; LS→TI | 0.48 (0.07) [6.76] (2); −0.19 (0.07) [−2.62] (2) | 2.49 (0.43) [5.72] (2) | 34.07 | 0.25 | 1.76 |

| Suggested and Estimated Models of the Study | Model Alternatives | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable(s) | R2 | Dependent Variable | Independent Variable(s) | R2 |

| TI | CS | 0.22 | CS | TI | 0.09 |

| LS | CS | 0.08 | CS | LS | 0.02 |

| TI | LS | 0.08 | LS | TI | 0.01 |

| TI | CS, LS | 0.25 | CS | TI, LS | 0.11 |

| LS | TI, CS | 0.14 | |||

| Causal Path | Coefficient (Average) | Std. Error | Confidence Interval | Inference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| CS→TI | 0.61 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.15 | Significant at the level of 5%. |

| CS→LS | −0.30 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.14 | |

| LS→TI | −0.24 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| CS; LS→TI | 0.45; −0.16 | 0.10; 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.13 | |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demiral, Ö. Commuting Stress–Turnover Intention Relationship and the Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis of Turkish Employees. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090147

Demiral Ö. Commuting Stress–Turnover Intention Relationship and the Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis of Turkish Employees. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(9):147. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090147

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemiral, Özge. 2018. "Commuting Stress–Turnover Intention Relationship and the Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis of Turkish Employees" Social Sciences 7, no. 9: 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090147

APA StyleDemiral, Ö. (2018). Commuting Stress–Turnover Intention Relationship and the Mediating Role of Life Satisfaction: An Empirical Analysis of Turkish Employees. Social Sciences, 7(9), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090147