Being Different with Dignity: Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design

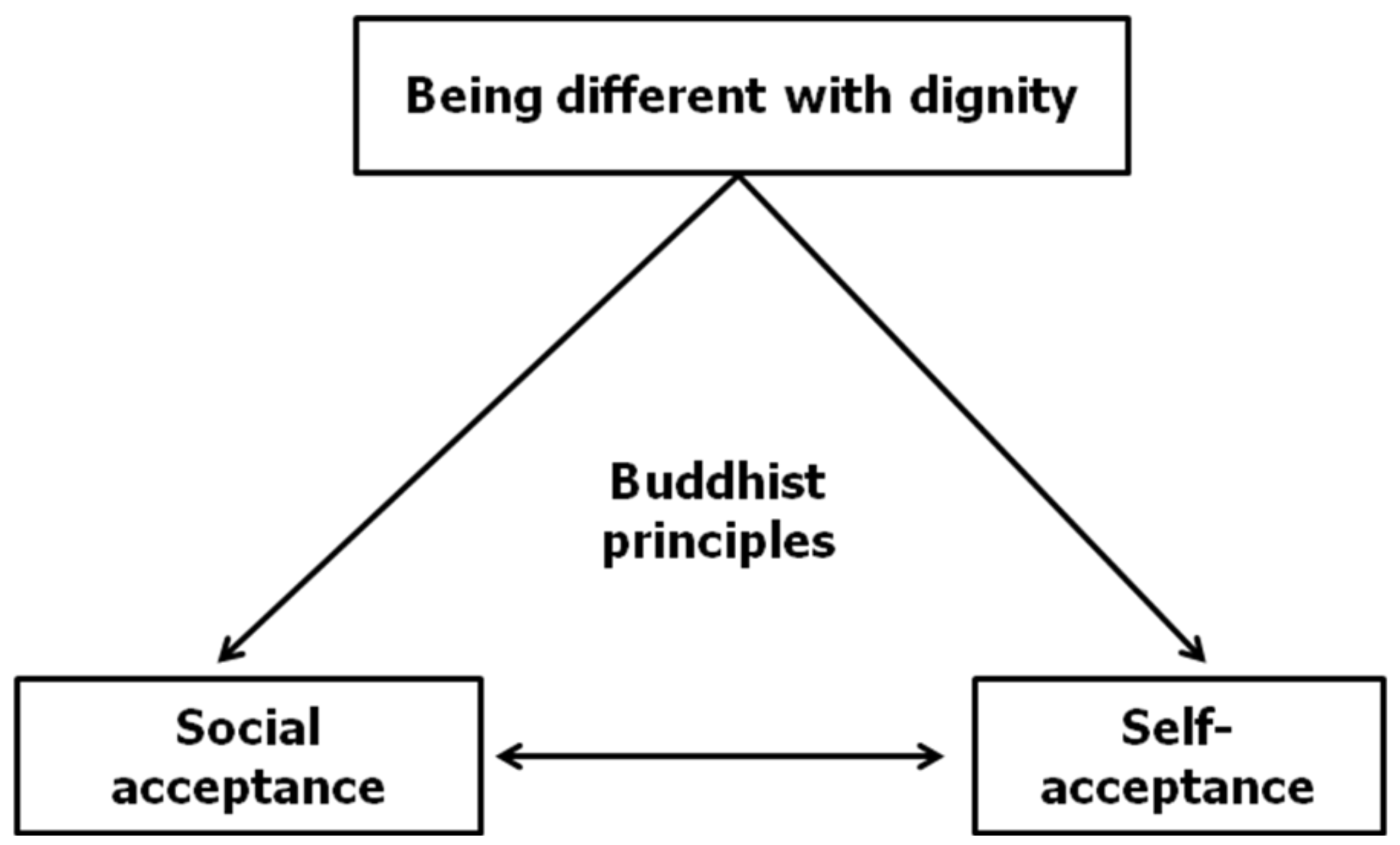

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality

“Homosexuals are as capable of wanting and of feeling love and affection towards their partners as heterosexuals are, and where such states are present homosexual sex is as acceptable as heterosexual sex.”

“I believe Buddhists’ attitudes towards LGBT are acceptance and love. Love only happens when we see others as equals with understanding and acceptance. The word tolerance isn’t even needed in this context. Support just comes naturally if one loves another, seeing it from a Buddhist perspective.”

“I’ve seen an email by a Buddhist saying LGBT [people] have no moral shame or fear of wrongdoing. Other Buddhists responded to this email [saying] that sexual orientation isn’t the issue; rather, it’s integrity and respect for each other.”

“My impression of Buddhists is largely formed of the particular [Buddhist] school I practise in, which is extremely open and accepting in the sense of not seeing any innate difference for someone practising who is LGBT, any more than a straight/heterosexual person … I have of course [benefited from] the usual widespread qualities of kindness, friendliness and acceptance of people within the Buddhist saṅgha [Buddhist monastic order in which the members are celibate and are officially ordained to provide religious services] in general.”

3.2. Interplay between Social Acceptance and Self-Acceptance

“The more I could learn to accept and understand myself, the more I could understand and feel more compassion for others and so feel more connected and less isolated. And also if I’ve been meeting maybe sometimes prejudices from others about my sexuality, I have more capacity to forgive and recognise that there may be some fear causing their attitude towards me. So I think it just gives me a lot more ways to understand the way human beings are relating to each other, for better or worse.”

3.3. Buddhist Insights

3.3.1. Non-Violating Precepts

He repeated the Buddhist viewpoint clearly, saying,“In the case of sexual behaviour, it’s not what gender your partner is … but rather what your intention is. So I’d say if your intention is to give and share, please, and express love and affection, and there was mutual consent, then that action would be good because your intentions are good, or positive. I just couldn’t see what would make that action immoral … If intentions were negative, that would be negative.”

“So homosexuality as such is neither positive nor negative, any more than heterosexuality is. What makes [it] one or the other is the intention behind the act. That’s not my opinion. That’s classical Buddhism.”

“When I practise the precepts, I was never told of any contradictions between the precepts and my sexual orientation … Basically I think in Buddhism everything begins with the intention. Intention is the key point. It doesn’t matter whether it’s same sex or opposite sex.”

“If two people [are] of the same gender or two people [are] of a different gender, their sexual actions are motivated by love and the desire to share, give comfort, or even have fun, that wouldn’t necessarily be an immoral act … Buddhist ethics about sex are primarily concerned with the motives behind our sexual behaviour, rather than the gender of our partner.”

3.3.2. Buddhist Equality

3.3.3. Manifestation of Existence

4. Implications

4.1. Methodological Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboul-Enein, Basil H. 2015. Marks of ambivalence of homosexuality between Arab literary works and Islamic jurisprudence: A brief historiographical commentary. Archives of Sexual Behaviour 44: 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasti, Sanaz. 2006. Comparative study of cruel and unusual punishment for engaging in consensual homosexual acts (in international conventions, the United States and Iran). Annual Survey of International and Comparative Law 12: 149–83. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Samman, Hanadi. 2008. Out of the closet: Representation of homosexuals and lesbians in modern Arabic literature. Journal of Arabic Literature 39: 270–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Joel, and Elise Holland. 2015. The legacy of medicalising homosexuality: A discussion on the historical effects of non-heterosexual diagnostic classifications. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain and Culture 11: 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, Yaakov. 2007. Judaism. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 138–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ariyabuddhiphongs, Vanchai, and Donnapat Jaiwong. 2010. Observance of the Buddhist five precepts, subjective wealth, and happiness among Buddhists in Bangkok, Thailand. Archives for the Psychology of Relgion 32: 327–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagde, Uttamkumars. 2014. Essential elements of human rights in Buddhism. Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution 6: 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Levi, and James K. McNulty. 2011. Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 853–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, David M., and Ilan H. Meyer. 2012. Religious affiliation, internalised homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82: 505–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, Joy Noel, and Jonathan K. Burns. 2014. Measuring social inclusion: A key outcome in global mental health. International Journal of Epidemiology 43: 354–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernat, Jeffrey A., Karen S. Calhoun, Henry E. Adams, and Amos Zeichner. 2001. Homophobia and physical aggression towards homosexual and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 110: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blais, Martin, Jesse Gervais, and Martine Hébert. 2014. Internalised homophobia as a partial mediator between homophobic bullying and self-esteem among youths of sexual minorities in Quebec (Canada). Ciência and Saúde Coletiva 19: 727–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blutha, Karen, and Priscilla W. Blanton. 2015. The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. Journal of Positive Psychology 10: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisvert, Donald. 2007. Homosexuality and spirituality. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell, C., P. Weatherburn, and F. Hickson. 2000. Sexually transmitted infection as a risk factor for homosexual HIV transmission: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. International Journal of STD and AIDS 11: 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brotman, Shari, Bill Ryan, and Robert Cormier. 2003. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist 43: 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, Allison. 2005. Queering heterosexual spaces positive space campaigns disrupting campus heteronormativity. Canadian Woman Studies 24: 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Burri, Andrea, Tim Spector, and Qazi Rahman. 2015. Common genetic factors among sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and number of sex partners in female twins: Implications for the evolution of homosexuality. Journal of Sexual Medicine 12: 1004–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, Jodie, and Joseph Ciarrochi. 2007. Psychological acceptance and quality of life in the elderly. Quality of Life Research 16: 607–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byne, William. 2015. LGBT health equity: Steps towards progress and challenges ahead. LGBT Health 2: 193–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd, A. Dean. 2001. Homosexuality and the Church of Jesus Christ: Understanding Homosexuality according to the Doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Springville: Cedar Fort. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Kate. 2010. We Exist: Intersectional in/Visibility in Bisexuality and Disability. Disability Studies Quarterly. 30. Available online: http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1273/1303 (accessed on 10 January 2017).

- Campo-Arias, Adalberto, Edwin Herazo, and Lizet Oviedo. 2015. Internalised homophobia in homosexual men: A qualitative study. Duazary 12: 140–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canali, Tiago José, Sylvia Marina Soares de Oliveira, Deivid Montero Reduit, Daniele Botelho Vinholes, and Viviane Pessi Feldens. 2014. Evaluation of self-esteem among homosexuals in the southern region of the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Ciência and Saúde Coletiva 19: 1569–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, Mariângela, Fabíola Adriane Cardoso, Marília Greco, Edson Oliveira, Júlio Andrade, Dirceu Bartolomeu Greco, Carlos Maurício de Figueiredo Antunes, and Project Horizonte team. 2003. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence in homosexual and bisexual men screened for admission to a cohort study of HIV negatives in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: Project Horizonte. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 98: 325–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Fung Kei. 2015. A qualitative study of Buddhist altruistic behaviour. Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment 25: 204–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Fung Kei. 2017a. Applying Buddhism to social work: Illustrated by the lived experiences of Buddhist social workers. In Spiritualität und Religion: Perspektiven für die Soziale Arbeit. Edited by Leonie Dhiman and Hanna Rettig. Weihein: Beltz Juventa, pp. 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Fung Kei. 2017b. Resilience of Buddhist sexual minorities related to sexual orientation and gender identity. International Journal of Happiness and Development 3: 368–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Fung Kei. 2017c. Using email and Skype interviews with marginalised participants. In SAGE Research Methods Case, Part 2: Health. Edited by Bronia Flett, Michael Gill and Christine Schorfheide. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Margatet H. 1980. Chigo monogatari: Love stories or Buddhist sermons. Monumenta Nipponica 35: 127–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzens, Donald B. 2014. Gay ministry at the crossroads: The plight of gay clergy in the Catholic Church. In More than a Monologue: Sexual Diversity and the Catholic Church: Voices of Our Times. Edited by Christine Firer Hinze and J. Patrick Hornbeck. New York: Fordham University, pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dalacoura, Katerina. 2014. Homosexuality as cultural battleground in the Middle East: Culture and postcolonial international theory. Third World Quarterly 35: 1290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, Luciana Karine, and Claudio Simon Hutz. 2016. Self-compassion in relation to self-esteem, self-efficacy and demographical aspects. Paideia 26: 181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Teresa. 2014. A delicate dance: Utilising and challenging the sexual doctrine of the Catholic Church in support of LGBTIQ persons. In More than a Monologue: Sexual Diversity and the Catholic Church: Voices of Our Times. Edited by Christine Firer Hinze and J. Patrick Hornbeck. New York: Fordham University, pp. 107–13. [Google Scholar]

- DeSteno, David. 2015. Compassion and altruism: How our minds determine who is worthy of help. Current Opinion in Behavioural Sciences 3: 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionne, Stéphanie Islane. 2002. Gay and lesbian health. In The Gale Encyclopaedia of Medicine. Edited by Jacqueline L. Longe. Michigan: Gale Group, pp. 1414–17. [Google Scholar]

- Doebler, Stephanie. 2015. Relationships between religion and two forms of homonegativity in Europe: A multilevel analysis of effects of believing, belonging and religious practice. PLoS ONE 10: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drescher, Jack. 2015. Out of DSM: Depathologising homosexuality. Behavioural Sciences 5: 565–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drydakis, Nick. 2014. Sexual orientation and labour market outcomes: Sexual orientation seems to affect job access and satisfaction, earning prospects, and interaction with colleagues. IZA World of Labour 111: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duncan, Dustin T., and Mark L. Hatzenbuehler. 2014. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health 104: 272–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, Bruce. 1998. Power and sexuality in the Middle East. Middle East Report 206: 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, Shinsuke. 2006. Social and internalised homophobia as a source of conflict: How can we improve the quality of communication. The Review of Communication 6: 348–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidhamar, Levi Geir. 2015. Divine revelation and human reasoning: Young Norwegian Muslims’ reflections on homosexuality. Sociology of Islam 3: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekotto, Frieda. 2016. Framing homosexual identities in Cameroonian literature. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 53: 128–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ellwood, Robert S., and Gregory D. Alles. 2007. The Encyclopaedia of World Religions, rev. ed. New York: Facts on File Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 1998. The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay-Jones, Amy L., Clare S. Rees, and Robert T. Kane. 2015. Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: Testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modelling. PLoS ONE 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flebus, Giovanni Battista, and Antonella Montano. 2012. The Multifactor Internalised Homophobia Inventory. TPM 19: 219–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, Barbara L., and the Committee on Adolescence. 2004. Sexual orientation and adolescents. Pediatrics 113: 1827–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, Karen I., Jane M. Simoni, Hyun-Jun Kim, Keren Lehavot, Karina L. Walters, Joyce Yang, Charles P. Hoy-Ellis, and Anna Muraco. 2014. The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualisation of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84: 653–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, Karen I., Hyun-Jun Kim, Chengshi Shiu, Jayn Goldsen, and Charles A. Emlet. 2015. Successful aging among LGBT older adults: Physical and mental health-related quality of life by age group. The Gerontologist 55: 154–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, David M., and Ilan H. Meyer. 2009. Internalised homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counselling Psychology 56: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Danilo, Al Nima Ali, and Oscar N. E. Kjell. 2014. The affective profiles, psychological well-being, and harmony: Environmental mastery and self-acceptance predict the sense of a harmonious life. PeerJ 2: e259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, Trevor G., and Pamela A. Viggiani. 2014. Understanding lesbian, gay, and bisexual worker stigmatisation: A review of the literature. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 34: 359–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorayeb, Daniela Barbetta, and Paulo Dalgalarrondo. 2010. Homosexuality: Mental health and quality of life in a Brazilian socio-cultural context. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 57: 496–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, S. J., H. J. Deuel, and C. A. Wright. 1940. Sex hormone studies in male homosexuality. Endocrinology 26: 590–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, Hank. 2004. Sexuality. In Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Edited by Robert E. Buswell. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, vol. 1, pp. 761–64. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, Joseph N. 2014. Fracturing interwoven heteronormativities in Malaysian Malay-Muslim masculinity: A research note. Sexualities 17: 600–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Arnold. 2001. Depathologising homosexuality. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 49: 1109–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, Darrell C., and Paula J. Britton. 2015. Predicting adult LGBTQ happiness: Impact of childhood affirmation, self-compassion, and personal mastery. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counselling 9: 158–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugler, Thomas K. 2011. Politics of pleasure: Setting South Asia straight. South Asia Chronicle 1: 355–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gumbleton, Thomas. 2014. A call to listen: The Church’s pastoral and theological response to gays and lesbians. In More than a Monologue: Sexual Diversity and the Catholic Church: Voices of Our Times. Edited by Christine Firer Hinze and J. Patrick Hornbeck. New York: Fordham University, pp. 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hammock, Clinton E. 2009. Heterosexual/Homosexual definitions and the homosexual narrative of James Purdy’s The Candles of Your Eyes. Journal of the Short Story in English 52: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2011. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics 127: 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillerbrand, Hans J. 2004. The Encyclopaedia of Protestantism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Irons, Edward A. 2008. Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. New York: Facts on File, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, Lyn. 2007. Homophobia and heterosexism: Implications for nursing and nursing practice. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 25: 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Karen M. 2000. Substance abuse among gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents. School Psychology Review 29: 201–6. [Google Scholar]

- Karesh, Sara E., and Mitchell M. Hurvitz. 2006. Encyclopaedia of Judaism. New York: Facts on File, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Hubert. 1997. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs: First theorist of homosexuality. In Science and Homosexualities. Edited by Vernon A. Rosario. New York: Routledge, pp. 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Keuroghlian, Alex S., Derri Shtasel, and Ellen L. Bassuk. 2014. Out on the Street: A public health and policy agenda for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84: 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Ki-Joo. 2011. Women and homosexuals in the South Korean defence force: Possibility and limitation of their full integration. The Korean Journal of International Studies 9: 233–60. [Google Scholar]

- King, Michael, Eamonn McKeown, James Warner, Angus Ramsay, Katherine Johnson, Clive Cort, Lucie Wright, Robert Blizard, and Oliver Davidson. 2003. Mental health and quality of life of gay men and lesbians in England and Wales: Controlled, cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatrity 183: 552–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleponis, Peter C., and Richard P. Fitzgibbons. 2011. The distinction between deep-seated homosexual tendencies and transitory same-sex attractions in candidates for seminary and religious life. The Linacre Quarterly 78: 355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, Doug, Mary Ann Devine, Shay Dawson, and Jennifer Piatt. 2015. Examining perceptions of social acceptance and quality of life of pediatric campers with physical disabilities. Children’s Health Care 44: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodny, Debra. 2007. Bisexuality. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kugle, Scott, and Stephen Hunt. 2012. Masculinity, homosexuality and the defence of Islam: A case study of Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s Media Fatwa. Religion and Gender 2: 254–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, Toshie. 2009. The concept of equality in the Lotus Sutra: The SGI’s viewpoint. The Journal of Oriental Studies 48: 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara, Toshie. 2015. Gender equality of Buddhist thought in the age of Buddha. The Journal of Oriental Studies: The Institute of Oriental Philosophy 25: 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Jan-Erik. 2006. Gender and homosexuality as a major cultural cleavage. Swiss Political Science Review 12: 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Paul. 2010. Homosexuality. In Encyclopaedia of Psychology and Religion. Edited by David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan. New York: Springer Science + Business Media LLC, pp. 411–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jason. 2014. Too cruel for school: LGBT bullying, noncognitive skill development, and the educational rights of students. Harvard Civil Rights: Civil Liberties Law Review 49: 261–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lipka, Michael. 2016. Why America’s ‘Nones’ Left Religion behind. Pew Research Centre. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/08/24/why-americas-nones-left-religion-behind/ (accessed on 26 December 2016).

- Logie, Carmen H., LLana James, Wangari Tharao, and Mona R. Loutfy. 2012. We don’t exist: A qualitative study of marginalisation experienced by HIV-positive lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender women in Toronto, Canada. Journal of the International AIDS Society 15: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzi, Giorgia, Marina Miscioscia, Lucia Ronconi, Caterina Elisa Pasquali, and Alessandra Simonelli. 2015. Internalised stigma and psychological well-being in gay men and lesbians in Italy and Belgium. Social Sciences 4: 1229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, Jamie L. 2014. Tainted love: The LGBTQ experience of Church. In More than a Monologue: Sexual Diversity and the Catholic Church: Voices of Our Times. Edited by Christine Firer Hinze and J. Patrick Hornbeck. New York: Fordham University, pp. 150–56. [Google Scholar]

- Markley, Arnold A. 2001. E. M. Forster’s reconfigured gaze and the creation of a homoerotic subjectivity. Twentieth Century Literature 47: 268–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, Alan. 2000. Images of gay men in the media and the development of self esteem. Australian Journal of Communication 27: 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Suzanne, Belinda Jude, and Angus J. McLachlan. 2007. Sexual orientation, sense of belonging and depression in Australian men. International Journal of Men’s Health 6: 259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, Stuart, and Brigitte Lhomon. 2006. Conceptualisation and measurement of homosexuality in sex surveys: A critical review. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 22: 1365–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Miller, Merle. 2012. On Being Different: What It Means to Be a Homosexual. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mireshghi, Sholeh I., and David Matsumoto. 2008. Perceived cultural attitudes towards homosexuality and their effects on Iranian and American sexual minorities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 14: 372–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mitchell, Stephen A. 2002. Psychodynamics, homosexuality, and the question of pathology. Studies in Gender and Sexuality 3: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleiro, Carla, and Nuno Pinto. 2015. Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontier in Psychology 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, Sandra, Andrea Frolic, and Brenda Key. 2015. Investing in compassion: Exploring mindfulness as a strategy to enhance interpersonal relationships in healthcare practice. Journal of Hospital Administration 4: 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, Frank, Bernhard Fink, Karl Grammer, and Michael Kirk-Smith. 2001. Homosexual orientation in males: Evolutionary and ethological aspects. Neuroendocrinology Letters 22: 393–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newman, Bernie Sue. 2002. Lesbians, gays and religion: Strategies for challenging belief systems. Journal of Lesbian Studies 6: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozeren, Emir. 2014. Sexual orientation discrimination in the workplace: A systematic review of literature. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences 109: 1203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Richard K. 2015. Pure land or pure mind? Locus of awakening and American popular religious culture. Journal of Global Buddhism 16: 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, Letitia Anne, and Susan D. Cochran. 1990. A relationship perspective on homosexuality. In Homosexuality/Heterosexuality: Concepts of Sexual Orientation. Edited by David P. McWhirter, Stephanie A. Sanders and June Machover Reinisch. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 321–49. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Henrique, and Patrícia Rodrigues. 2015. Internalised homophobia and suicidal ideation among LGB youth. Journal of Psychiatry 18: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Centre. 2009. Leaving Catholicism. Available online: http://www.pewforum.org/2009/04/27/faith-in-flux/ (accessed on 26 December 2016).

- Phillips, Richard. 2006. Unsexy geographies: Heterosexuality, respectability and the Travellers’ Aid Society. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 5: 163–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, P. V., K. S. Ayyar, and V. N. Bagadia. 1982. Homosexuality: Treatment by behaviour modification. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 24: 80–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Provence, Markus M., Aaron B. Rochlen, Matthew R. Chester, and Emily R. Smith. 2014. Just one of the guys: A qualitative study of gay men’s experiences in mixed sexual orientation men’s groups. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 15: 427–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Momin. 2014. Homosexualities, Muslim Cultures and Modernity. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Marc Eric S., Paul John P. Lanic, Erwin Nikko T. Lavadia, Emmet Fernanne Joy L. Tactay, Edrae R. Tiongson, Pamela Jennifer G. Tuazon, and Lynn E. McCutcheon. 2015. Self-stigma, self-concept clarity, and mental health status of Filipino LGBT individuals. North American Journal of Psychology 17: 343–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rowson, Everett K. 2004. Homosexuality. In Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. Edited by Richard C. Martin. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, pp. 316–17. [Google Scholar]

- Roxas, Maryfe M., Adonis P. David, and Eduardo C. Caligner. 2014. Examining the relation of compassion and forgiveness among Filipino counsellors. Asian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 3: 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Fang-fu, and Yung-mei Tsai. 1987. Male homosexuality in traditional Chinese literature. Journal of Homosexuality 14: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, Glenda M., and Janis S. Bohan. 2006. The case of internalised homophobia. Theory and Psychology 16: 343–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagone, Elisabetta, and Maria Elvira De Caroli. 2014. Relationships between psychological well-being and resilience in middle and late adolescents. Procedia: Social and Behavioural Sciences 141: 881–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiz, Halis, and Hakan Sariçam. 2015. Self-compassion and forgiveness: The protective approach against rejection sensitivity. International Journal of Human Behavioural Science 1: 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sánchez, Francisco J., Stefanie T. Greenberg, William Ming Liu, and Eric Vilain. 2009. Reported effects of masculine ideals on gay men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 10: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, Kathleen M. 2007. Homosexuality, religion, and the law. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Susan Douglas, Alastair Pringle, and Colin Lumsdaine. 2004. Sexual Exclusion: Homophobia and Health Inequalities: A Review. London: UK Gay Men’s Health Network. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, Brad, and Christy Mallory. 2014. Employment discrimination against LGBT people: Existence and impact. In Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Discrimination in the Workplace: A Practical Guide. Edited by Christine Michelle Duffy. Arlington: Bloomberg BNA. [Google Scholar]

- Semerdjian, Elyse. 2007. Islam. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 128–33. [Google Scholar]

- Siker, Judy Yates. 2007. American Baptist churches USA. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Heather. 2010. Dying for love: Homosexuality in the Middle East. Human Rights and Human Welfare 2010: 160–72. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Glenn, Annie Bartlett, and Michael King. 2004. Treatments of homosexuality in Britain since the 1950s: An oral history: The experience of patients. British Medical Journal 328: 429–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan A., Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin. 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, Sanchita, and Purnima Singh. 2015. Psychosocial roots of stigma of homosexuality and its impact on the lives of sexual minorities in India. Open Journal of Social Sciences 3: 128–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sujato, Bhikkhuni. 2012. Why Buddhists Should Support Marriage Equality. Available online: https://sujato.wordpress.com/2012/03/21/1430/ (accessed on 30 August 2015).

- Sumerau, J. E. 2016. They just don’t stand for nothing: LGBT Christians’ definitions of non-religious others. Secularism and Nonreligion 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, Michael J. 2007. Buddhism. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, Judit. 2004. Social Exclusion of Young Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) People in Europe. Brussels: The European Region of the International Lesbian and Gay Association. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira-Filho, Fernando Silva, Carina Alexandra Rondini, and Juliana Cristina Bessa. 2011. Reflections on homophobia and education in schools in the interior of Sao Paulo state. Educação e Pesquisa 3: 725–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teliti, Adisa. 2015. Sexual prejudice and stigma of LGBT people. European Scientific Journal 11: 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Thiselton, Anthony C. 2002. A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Harry. 2013. Immaculate manhood: The city and the pillar, Giovanni’s room, and the straight-acting gay man. Twentieth-Century Literature 59: 596–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumma, Scott. 2007. Evangelical Christianity. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 112–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tolino, Serena. 2014. Homosexuality in the Middle East: An analysis of dominant and competitive discourses. DEP: Deportate, Esuli, Profughe 25: 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, Gill. 1993. (Hetero)sexing space: Lesbian perceptions and experiences of everyday spaces. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11: 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wormer, Katherine, and Robin McKinney. 2003. What school can do to help gay/lesbian/bisexual youth: A harm reduction approach. Adolescence 38: 409–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanita, Ruth. 2007. Hinduism. In Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopaedia. Edited by Jeffrey S. Siker. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 125–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, James E., III. 2011. Homophobia. In Encyclopaedia of Child Behaviour and Development. Edited by Sam Goldstein and Jack A. Naglieri. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, pp. 751–52. [Google Scholar]

- Viau, Jeanine E. 2014. Calling out in the wilderness: Queer youth and American Catholicism. In More than a Monologue: Sexual Diversity and the Catholic Church: Voices of Our Times. Edited by Christine Firer Hinze and J. Patrick Hornbeck. New York: Fordham University, pp. 124–37. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, J., J. Shaver, and R. Stephenson. 2016. Outness, stigma, and primary health care utilisation among rural LGBT populations. PLoS ONE 11: e0146139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B. 2001. Pastoral care of homosexuals. In The New Catholic Encyclopaedia: Jubilee Volume, The WOJTY2A Years. Edited by Peter M. Gareffa, Laura Standley Berger, Joann Cerrito, Thomas Carson, William Harmer, Stephen Cusack, Erin Bealmear, Jason Everett, Laura S. Kryhoski, Margaret Mazurkiewicz and et al. Washington: The Catholic University of America, pp. 310–13. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Monnica. 2008. Homosexuality anxiety: A misunderstood form of OCD. In Leading-Edge Health Education Issues. Edited by Lennard V. Sebeki. New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Liz. 2003. Buddhist views on gender and desire. In Sexuality and the World’s Religions. Edited by David W. Machacek and Melissa M. Wilcox. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Inc., pp. 133–73. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Joseph, and Joe Phillips. 2015. Paths of integration for sexual minorities in Korea. Public Affairs 88: 123–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Andrew K. T. 2009. Queerness and sangha: Exploring Buddhist lives. In Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places. Edited by Kath Browne, Sally R. Munt and Andrew K.T. Yip. Surrey, Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Chün-fang. 1997. Ambiguity of Avalokiteśvara and the scriptural sources for the cult of Kuan-yin in China. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 10: 409–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zessin, Ulli, Oliver Dickhauser, and Sven Garbade. 2015. The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 7: 340–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jia Wei, and Serena Chen. 2016. Self-compassion promotes personal improvement from regret experiences via acceptance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 42: 244–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlstra, Iris. 2014. The turbulent evolution of homosexuality: From mental illness to sexual preference. Social Cosmos 5: 29–35. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, F.K. Being Different with Dignity: Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7040051

Cheng FK. Being Different with Dignity: Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Fung Kei. 2018. "Being Different with Dignity: Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality" Social Sciences 7, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7040051

APA StyleCheng, F. K. (2018). Being Different with Dignity: Buddhist Inclusiveness of Homosexuality. Social Sciences, 7(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7040051