Abstract

Prior research has examined the impact of community-oriented policing (COP) on crime extensively. While the implementation of community policing has been considered mainly within the context of large police agencies, there is a paucity of research on how COP impacts crime reduction efforts in smaller locales. This study explores the effects of the degree of community policing implementation within smaller agencies and cities on crime. As part of the discussion on the impact of COP implementation, this paper also considers the impact of social disorganization on crime in the United States. The aim is to gain further insight into what variables may be influencing crime rates in contexts that garner less attention from researchers. The findings indicate that COP implementation does not significantly explain the variation of crime rates. Still, the statistically significant results on several social disorganization factors reflect the need to incorporate social disorganization theory with practice in order to maximize community-policing success. The implications of these results for police practice as well as directions for future research are discussed.

1. Introduction

The ebb and flow of police-citizen relations has garnered a great deal of attention from scholars and practitioners. The need to examine policing strategies is increasingly important due to the questionable incidents of officer-involved shootings in minority communities in the United States. The aftermath of public outrage often characterized by Black Lives Matter protests, and riots in some instances are additional reasons why policing strategies are worthy of scholarly assessment. Some have argued that community-oriented policing (COP) is part of a necessary prescription for building trust in many large metropolitan areas where such police-civilian conflicts often occur (Gill et al. 2014; Kelling and Moore 1988). It is also widely held that community-oriented approaches can be successful in reducing crime in problematic inner-city areas (Connell et al. 2008; Rosenbaum and Lurigio 1994).

Although most empirical studies examine policing strategies such as COP within the context of large metropolitan cities and agencies, it is equally important to contribute to the limited research on smaller populations to increase knowledge of the applicability of COP in less studied settings. In addition, it is important to note that crime is not the sole burden of police. Rather than focusing solely on policing strategies, it is reasonable to incorporate social factors into crime prevention frameworks (Brogden and Nijhar 2005). Based on this reasoning, we bring the theory of social disorganization into this discussion. We suggest that the practical implications of COP and the theoretical implications of social disorganization are complementary perspectives that ought to be considered together. Moreover, prior research shows that individuals living in socially disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to hold less favorable views of police and experience higher crime rates (Kubrin and Weitzer 2003; Sampson and Bartusch 1998), and neighborhoods that in theory should benefit the most from COP are often the locales that are most resistant to any type of formal control (Grinc 1994). It is also noteworthy that communities with weaker social ties and higher levels of disorganization may be subject to higher crime rates due to changes in routine activities (Andresen 2006).

The ongoing discussion on crime in communities should therefore not only comprise the implementation of COP, but also solutions for improving social organization conditions. Throughout the implementation stages of COP, if community conditions are not accounted for, the introduction of these strategies might prove to be more harmful than beneficial to some communities. With these issues in mind, this study examines the degree of community policing implementation while controlling for social disorganization factors. The analysis is based on data collected from a national sample of small police agencies and cities across the US. We also discuss the implications for police practice and directions for future research on crime prevention in smaller cities.

1.1. The Context of Community-Oriented Policing Implementation

In our quest to understand the nuances of community-oriented policing, the exclusion of smaller departments and populations may be problematic due to the dissimilarities in how crime is generated within urban and rural areas. Moreover, the extent to which citizens are willing to act as co-producers of crime control alongside law enforcement also differs based on the social organization of the communities in which community-oriented policing is implemented (Gill et al. 2014; Greene and Pelfrey 2001). Nonetheless, what has become increasingly evident amid recent backlashes against the police, is that COP has become preferred to the traditional model of policing that relied largely on reactive measures such as issuing tickets and making arrests (Maguire and Mastrofski 2000; Pelfrey 2004).

To address the gap in the literature, in terms of nonmetropolitan communities, Wells and Weisheit (2004), used county-level data to examine whether crime-predicting variables used in urban models were in fact applicable to rural settings. Contrary to their original hypotheses, the researchers found that ecological and structural characteristics predicted urban crime to a better extent than rural crime, leaving them to conclude that the set of variables that best predicted crime in urban areas were not the same variables that predicted rural crime rates.

Therefore, understanding the context in which COP is implemented is extremely vital to the success of the strategy. As noted by Brogden and Nijhar (2005), when community conditions are unaccounted for during the implementation of COP, the introduction of these strategies may prove to be more harmful than constructive to communities. Disregarding community composition, could make the goal of reducing fear of crime, or increasing police legitimacy through the building of citizen relationships, practically unattainable.

1.2. Social Disorganization

The theory of social disorganization can be traced to the Chicago School and the work of Shaw and McKay (1942), and it has come a long way since its original conceptualization. Shaw and McKay (1942) were one of the first to argue that communities that lack necessary resources due to low economic status would generally have weaker social cohesion (i.e., social ties) and in return be subject to higher crime rates. To further support the theory, recent literature has linked structural characteristics to crime and delinquency and has provided claims that informal controls can mediate the relationship between the two (Bursik and Webb 1982; Hart and Waller 2013; Smith and Jarjoura 1988). To extend the study of community social disorganization and crime beyond urban settings, Osgood and Chambers (2000) conducted county-level analysis on more than 250 nonmetropolitan counties across four states. The study found not only that the themes from the theory are applicable to communities of all sizes, but also that nonmetropolitan communities present different patterns of structural variables that are worth examining further.

The more recent studies on social disorganization seek to incorporate informal controls such as collective efficacy and social cohesion to obtain a better understanding of community conditions and their relation to crime. Collective efficacy is a predictor of community functioning (Warner 2007) and is generally represented by trust in residents, a willingness to intervene in neighborhood problems and maintaining social controls for the common good (Sampson 2012). Social cohesion is formed through neighborhood interaction and generally leads to stronger social ties (Gau 2014; Sampson and Raudenbush 1999). Uchida et al. (2014) explain that when social cohesion and or trust among neighbors is at its peak, the potential to build upon collective action or collective efficacy is greater. In short, however, it can be summarized that if a community is facing hardships and lacks necessary informal controls needed to prevent crime, formal controls, such as the intervention of COP officers, may prove to be ineffective or not accepted (Sampson 2012; Warner 2007).

When discussing the differential levels of disorganization in communities as they relate to crime and deviance, it is important not to neglect supporting theories such as routine activities and the idea of capable guardianship. Both the theory of social disorganization and routine activities share the idea that crime has a geography and, because human behavior is often situated in a particular place, the location of crime must be heavily emphasized (Andresen 2006). Cohen and Felson (1979), the study often credited for developing the routine activity theory, contends that for crime to occur there must be a motivated offender, a suitable target, and a perceived lack of guardianship. To relate this theory back to social disorganization, it must be acknowledged that different locales—due to their differing socio-economic characteristics and demographics, display different routine activities which in turn leads to crime and deviance being neither uniformly or randomly distributed (Mustaine and Tewksbury 1998).

1.3. Community-Oriented Policing

Community-oriented policing strategies vary across agencies as some may require different strategies to tackle unique community-related problems. This variance may be regarded as disadvantageous to the extent that it prevents a uniform definition and implementation of COP, however, it is advantageous in the sense that each agency can implement the strategy as necessary to the community that it serves. However, defining community-oriented policing is much easier said than done. Consensus has not been reached on defining COP (Sozer and Merlo 2013), but it is generally referred to as a philosophy that aims to empower communities rather than control them. COP encourages police to find solutions for a multitude of community problems and concerns such as crime, fear of crime, quality of life, and neighborhood conditions (Lord et al. 2009; Reisig and Parks 2004).

Since its rise in popularity over the last thirty years, notably during the mid-1990s with the creation of the Office of Community-Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office), many law enforcement agencies in the US have implemented programs that are generally in accordance with the overall components of community policing (Somerville 2009; Morabito 2010). These components include community partnerships, organizational transformation and problem-solving, with terms such as “community involvement” and “decentralization” often used interchangeably (Somerville 2009).

Most advocates of COP believe that it can strengthen cohesion among community residents as well as social organization, further leading to reduced crime and disorder (Kerley and Benson 2000; Sadd and Grinc 1994). It is important to understand, however, that community-oriented policing does not flow in one direction—police to community—but instead works best when there is a flow between the two (Bain et al. 2014). To that point, a proactive style of policing is more likely to garner positive public perceptions of police and allow for COP initiatives to function more effectively (Wentz and Schlimgen 2012). Positive encounters with police should then theoretically increase community confidence in police work and relationships in which members are willing to approach officers with their local problems (Bain et al. 2014). This in turn may lead to higher crime reporting rates in communities in which COP is implemented properly. This type of outlook should not be dismissed but instead considered when answering the question as to why studies on COP effectiveness may have varying conclusions regarding increasing and decreasing crime rates.

Gill et al. (2014) conducted a meta-analysis that included thirty-seven independent tests on COP. Their study found evidence that community policing increased citizen satisfaction and perceptions of police legitimacy. However, regarding crime prevention, Gill et al. (2014) did not find any consistent evidence to support the assumption that COP influences crime rates. Moreover, they found that problem-solving strategies, whether utilized within an agency or not, also had no impact on crime rates. In general, their study produced support for the main objective of COP in improving the relationship between the community and public, but as noted by the researchers, their findings were also a reflection of the complexities in the relationship between COP and all other variables, such as disorder, fear, and social controls.

1.4. Community-Oriented Policing and Nonmetropolitan Communities

Contributing to the limited research on COP and nonmetropolitan communities, Connell et al. (2008) examined whether community policing can reduce serious crime in a suburban setting. The researchers used data from both, interviews conducted with officers involved in a COP initiative, as well as crime rates over an eight-year period within the locations that COP was implemented. Running a time series analysis on the data, the researchers found a significant reduction in property and violent crimes in areas that COP was implemented. Furthermore, the interview portion showed that the officers involved in COP were very eager to implement strategies within their jurisdiction. Officers who did not share this view within the department were able to switch beats and shift to other positions within the agencies. By doing so, the potential success of the COP strategies would not be hindered by those who lacked interest in the intervention. This supports the argument made by Sadd and Grinc (1994), that in order for community-oriented policing to be successful, officers or personnel must believe in the means and goals.

Sozer and Merlo (2013) provide a foundation for the present study, as their main objective had been to examine the relationship between level of implementation of COP and crime rates across various agency sizes. To observe this relationship, the researchers separated agencies by those serving fewer than 50,000 individuals and those serving more than 50,000 individuals. Furthermore, three dimensions were used to measure the level of COP implementation across agencies. These included community contribution, problem-solving partnerships and training, and problem-solving, which were all created through reducing 35 dichotomous variables through factor analysis. In the end, Sozer and Merlo (2013) found no evidence of COP in terms of a crime reduction effect, and in contrast to expectations, the researchers found certain community policing strategies to be associated with higher crime rates in both small and large cities.

The need to examine community-oriented policing implementation outside of urban areas is due in part to the recognition that structural variables present differently in nonmetropolitan locations than they do in urban ones (Kaylen and Pridemore 2013; Osgood and Chambers 2000). As stated by Adams et al. (2005), more often than not, these smaller departments that lack empirical evaluations are those that comprise the majority of publicly funded law enforcement agencies. Moreover, since community-oriented policing is based on the idea of strengthening the social organization of communities, it is surprising that an underwhelming amount of research has been directed towards examining the relationship between the two, especially as various community characteristics might also influence styles of policing (Maguire et al. 1997). The purpose of this present study is not only to determine COP’s effect on violent and property crime, it is also to examine whether COP implementation can predict crime rates when controlling for social disorganization.

2. Materials and Methods

This study merges three data sets—The 2013 Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics Survey (LEMAS), the 2012 Uniform Crime Reports (UCR), and the 2012 US Census 5-Year American Community Survey (ACS). The aim was to examine both the implementation of COP within 309 law enforcement agencies as well as social organization and crime rates in the areas where these agencies are located. The study sought to answer the following questions: (1) Is the implementation of community policing predictive of crime rates, controlling for agency size and indicators of social disorganization? (2) Are characteristics of social disorganization predictive of crime rates in small cities? It was hypothesized that there would be an inverse relationship between the degree of COP implementation and crime rates. It was also expected that variables pertaining to social disorganization would influence both property and violent crime rates.

To create a sample of smaller-sized law enforcement agencies and jurisdictions, only those employing between 40–80 full-time sworn personnel were included within the study. Therefore, from the initial LEMAS dataset comprised of 2822 law enforcement agencies, the following agencies were eliminated: 895 sheriff’s offices, 50 state agencies, agencies with 100 or more sworn personnel, and agencies with 39 or fewer sworn full-time personnel. Moreover, after merging and examining all three datasets, 3 agencies were eliminated due to an extensive amount of missing LEMAS data, 1 agency was eliminated due to not holding a primary jurisdiction within the ACS or UCR data, and 15 agencies were deleted as there was neither property nor violent crime rate data available. The final sample size therefore consisted of 309 law enforcement agencies.

The dependent variables, property and violent crime rates, were generated from the 2012 Crime Reporting Program using the FBI’s classifications for each offense. Burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft were combined to form the property variables, whereas murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault were combined to form the composite violent crime variable. Although arson is a part of the FBI property crime classification, it was not included in the present study as issues existed in reporting. To control for population size, crime rate per 1000 residents was used.

2.1. Measuring Community-Oriented Policing Implementation

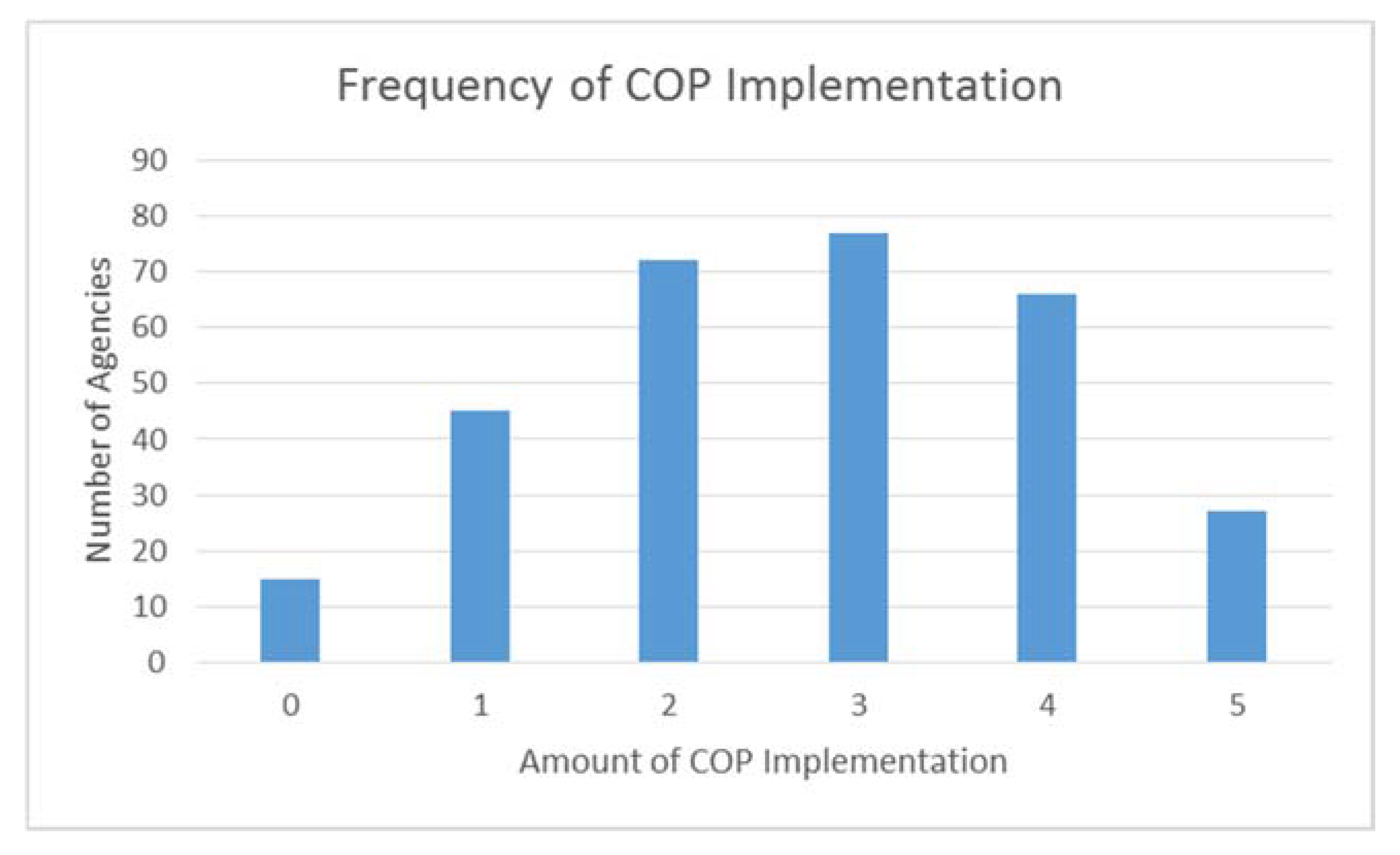

Regarding the measurement of COP implementation, we used 2013 LEMAS data to generate a single composite-variable. At the time of writing, these were the most recent available national-level data on the subject. Variables that best fell in line with the overarching theme of COP presented by the Office of Community-Oriented Policing Services (COPS) were selected to form an index variable. These variables included problem-solving partnerships, geographic assignment of officers, the encouragement of SARA–type (Scanning, Analysis, Response, and Evaluation) problem-solving projects, the utilization of information from community survey, and lastly, at least 8 h of in-service COP training. These variables, which were captured through the survey design in a dichotomous fashion, were then coded into new variables in which 0 signified “no,” and 1 signified “yes.” Within the context of the index variable, a 0 therefore meant no implementation whereas 5 highlighted the implementation of all variables within an agency. The variations of implementation are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Frequency of COP implementation.

It is evident from the descriptive statistics that of the 309 law enforcement agencies selected for the study, the majority of agencies (n = 77), reported implementing at least 3 of the 5 community-oriented policing strategies included in this study, whereas only 27 implemented all 5 strategies within their agencies. The remaining agencies reported implementing zero, one, two, or four strategies and of the 309 agencies, seven agencies did not report for any of these five strategies and are not depicted in the figure. In addition, the total number of full-time sworn personnel was used as a control for law enforcement agency size. Based on the definition provided by LEMAS, sworn personnel are deputies and law enforcement officers with general arrest powers. Only agencies employing between 40–80 full-time sworn personnel were included in the study to depict smaller-sized agencies.

2.2. Measuring Social Disorganization

The underlying theme of social disorganization emphasizes both environmental and social characteristics in explaining the etiology of crime and anti-social behavior (Shaw and McKay 1942). This study utilized the Census Bureau’s 2012 American Community Survey to depict the social organization of cities in which community-oriented policing was implemented. The variables included were the percentage of individuals whose income was below the poverty level, percentage of individuals foreign-born, percentage of female householders with children under the age of 18 with no husband present, and percentage of the population black or African American (See Table 1). Although the study initially incorporated the percentage of renter occupied housing units, the variable was removed due to its high level of collinearity with the percentage of individuals whose income is below the poverty level.

Table 1.

Measures of Central Tendency of Independent, Dependent, and Control Variables (n = 309).

Although skewed data indicates that outliers exist, in a study examining the social organization of 309 various cities located across the US, these outliers are almost expected. Moreover, the variation in variables such as the percentage of population black or African American or percentage of individuals whose income is below the poverty level for example, are a clear indicator of the importance of taking the social context of communities into consideration when deploying policing strategies.

In order to yield a model that infers any relationship between variables and their predictive power within the observed populations, the statistical technique utilized for this study was ordinary least square (OLS) regression. This allows for the identification of any unique contributions made by the key independent variables and likewise allows for the determination of how well the model accounts for or explains the variations that occur in the dependent variable.

3. Results

To gain better understanding of the impact of each of the variables included within the community-oriented policing implementation outside of the index variable, the model depicted in Table 2 examines each community policing strategy and its overall impact on the variation of both property and violent crime rates separately. Table 3 shows the impact of the composite COP variable and its effect on crime rates alone without the inclusion of any social disorganization characteristics.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Model for Individual COP Variables and Property and Violent Crime Rates (n = 309).

Table 3.

Regression Model for COP Composite Variable (n = 309).

When examined individually, the five community-oriented policing strategies, including problem-solving partnerships, geographic assignment of officers, the encouragement of SARA—type problem solving projects, the utilization of information from community surveys, and at least 8 hours of in-service COP training showed no significant contributions to the variations of property and violent crime rates. Both models held very low R-values of 0.108 in the property crime model, and 0.175 in the violent crime model. Therefore, given the low R-values and F ratios that are not statistically significant, the models did not hold high explanatory power. Likewise, although insignificant it is interesting to note that a one-increment increase in the geographic assignment of officers (beat patrol), and the utilization of information from community surveys were associated with higher rates of reported property crimes.

The regression model for the community-oriented policing composite variable provides similar results to the findings presented in Table 2. Although an argument can be made that community-oriented policing implementation alone makes no significant contribution to the variation of property and violent crime rates, the null results should not be viewed in a negative light. Instead, it should be noted that the overall directions of the results displayed in Table 3 are in the direction originally hypothesized. Nonetheless, the R-value of the property crime model is extremely low, at only 0.021 whereas the R-value of the violent crime model reaches 0.080. In addition, both F-ratios are not statistically significant, further indicating the lack of contribution made to the models by the composite variable.

3.1. The Full Model

The full model demonstrates the changes in significance when theory and practice are integrated. In Table 4, property crime rate per 1000 and violent crime rate per 1000 are regressed against the following variables, the total number of full-time personnel, COP implementation, percentage of the population black or African American, percentage of individuals foreign-born, percentage of female householders with child under the age of 18 and no husband present, and percentage of individuals whose income is below the poverty level, using the enter method.

Table 4.

Final OLS Regression Model for Property Crime and Violent Crime Rates per 1000 (n = 309).

According to Hinton et al. (2014), the closer the R-value is to 1.00, the higher the explanatory or predictive power of the model. Evaluating the results of the multiple regression model displayed in Table 4, the property crime rate model had an approximate R-value of 0.587, whereas the violent crime model held an R-value of 0.561. The predictive power of the models as determined through the ANOVA test and F ratio indicated a statistically significant result at the 0.000 level for property crime rates (25.75) and likewise a statistically significant result for violent crime rates (21.69). This is an indication that the models’ predictions of changes in the dependent variables are more accurate than just chance alone. The property crime model accounted for 34.4% of the variance in the population, with an adjusted R-Square of 33.1%. In terms of the violent crime model, the model accounted for 31.5% of the variance in the population with an adjusted R-Square of 30.1% indicating a slightly more powerful property crime model than the latter. Provided that most models in criminal justice research do not exceed 40% (Weisburd and Britt 2007), it can be said that both models predict crime rates fairly well. The contribution of individual variables within the models will be examined subsequently.

3.2. The Property Crime Model

The control variable of full-time sworn personnel had the second weakest contribution to the model with a Beta of −0.033. However, it was found that a one-increment increase in the amount of full-time sworn personnel resulted in a 0.054 decrease in property crime per 1000, which is in the direction hypothesized but not statistically significant. The amount of COP implementation, which ranged on a 0–5 scale, did not make a statistically significant contribution to the property crime model as it had the lowest Beta of −0.001. However, a one-increment increase in the amount of implementation resulted in a 0.017 decrease in crime, which is also in the direction hypothesized but not holding any statistical significance. The percentage of the population black or African American had a rather weak contribution to the property crime model with a Beta of 0.039. Although not statistically significant, a one-increment increase in Black or African American individuals resulted in an increase of property crimes per 1000 by 0.041, which is in the direction originally hypothesized. A significant predictor to the property crime model was the independent variable of percentage foreign-born individuals with a Beta of −0.236. This variable had an unstandardized coefficient of −0.435, therefore holding all other variables constant, a one-increment increase of foreign-born individuals equates to a decrease of 0.435 in property crime rates per 1000. Although in the direction hypothesized, it is important to note that this result is contrary to the theory of social disorganization, which asserts that communities with more foreign-born individuals have less social cohesion and more crime.

Percentage of female householder with child under the age of 18 and no husband present was the second strongest and significant predictor of property crime rates with a Beta of 0.272. This variable had an unstandardized coefficient of 1.442, which means that holding all other variables constant, a one-increment increase in the percentage of female householders equates to a 1.442 increase in property crime rates per 1000, an expected result in accordance to the hypothesis. In terms of contribution to the prediction, the percentage of individuals whose income is below the poverty level was the highest significant predictor of property crime rates per 1000 with a Beta of 0.273. This variable had an expected unstandardized B coefficient of 0.513, which means that a one-increment increase in the number of individuals whose income is below the poverty level equates to a 0.513 increase in property crimes per 1000. Thus, a 10% increase would result in an additional 5 crimes per person.

3.3. Violent Crime Model

In the violent crime model, full-time sworn personnel also had the second weakest contribution with a Beta of 0.068, indicating that a one-increment increase in full-time sworn personnel resulted in a 0.029 increase in violent crime. Not only was this result insignificant, it was also not in the direction hypothesized. Moreover, COP implementation also made a weak contribution to the model with a −0.057 Beta. However, a one-increment increase in the amount of implementation within an agency resulted in a 0.204 decrease in crime, a result greater than what was seen with the property crime model. Nonetheless, while this result is in the direction hypothesized, it did not hold any statistical significance. Percentage of the population black or African American had a rather strong and significant contribution to the model with a beta of 0.136. This result is in the direction hypothesized. The percentage of foreign-born individuals did not make a significant contribution to the model, holding a Beta of −0.083. However, similar to the property crime model, a one-increment increase of foreign-born individuals also resulted in a 0.040 decrease in violent crime rates per 1000, a result in agreement with the hypothesis but in overall contrast to social disorganization literature. The strongest contribution to the model was made by the percentage of female householders with children under the age of 18 and no husband present, with a Beta of 0.322. These findings reflect the hypothesis and literature on the theory of social disorganization. Lastly, percentage of individuals whose income is below the poverty level also made a strong significant contribution to the model. These findings are consistent with decades of research on poverty and crime.1

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to observe the variations of community-oriented policing implementation within smaller agencies while accounting for the social context. Predictors of social disorganization alongside community policing variables were examined to assess their impact on both property and violent crime rates within smaller locales. To measure implementation, five main strategies that fell under the general definition of community-oriented policing were combined to form an additive scale in which all variables were comprised of equal weight. These strategies included problem-solving projects, utilization of community surveys, the encouragement of SARA–type problem-solving projects, the geographic assignment of officers, and at least 8-h of in-service community policing training.

Of the 309 agencies observed, the majority (77) of these agencies implemented at least three of the five strategies within their departments, whereas only 27 reported implementing all five. Although it was hypothesized that controlling for both agency size and social disorganization, a greater degree of COP implementation would be associated with fewer property and violent crime rates across smaller locales, this study did not find any strong evidence to justify that community-oriented policing implementation impacts city-level crime rates (Gill et al. 2014; Kerley and Benson 2000; Sozer and Merlo 2013). It is important to note, however, that although not statistically significant, the findings of the study were in the direction hypothesized and call for further consideration.

The null results can be explained as follows. First, the adoption of community policing occurred at a time in which the professional model became highly criticized and deemed ineffective (Roh and Oliver 2005). Agencies that began implementing COP shifted away from reactive measures and primarily focused on finding ways to proactively respond to crime and on becoming more attentive to physical and social community disorder to decrease fear of crime and find solutions to local problems. It was not until the mid-1990s, with the establishment of the Justice Department’s Office of Community-Oriented Policing Services, that crime reduction became an increasingly important objective behind particular strategies (Skogan 2006). As a result, community-oriented policing began to be evaluated in terms of its crime reduction potential. However, as stressed by Gill et al. (2014), it is ironic that researchers continue to dedicate time and resources towards evaluating COP on its ability to reduce crime rates. It has become clear that achieving a direct impact on crime rates was never the primary objective of COP to begin with. Therefore, by disregarding the success of community policing on factors such as the decrease in fear of crime or increase in police legitimacy, and instead deeming the practice as either effective or ineffective based solely on its ability to impact crime rates, defies the basis of the philosophy.

Community policing, based on its success in creating positive shifts in police-citizen culture, should instead be regarded as a catalyst for social change and order. The reduction of fear of crime is just as important as the reduction of crime rates themselves and allows for a community to self-police. Individuals will not act on crime control if they have any indication or fear that their actions may affect their safety in any way (Bureau of Justice Assistance 1994). Furthermore, when police engage in community-oriented strategies that indirectly impact crime, they potentially improve relationships with the public while increasing police presence. This increased level of presence alone, has the ability to raise levels of satisfaction among community members, allowing for the growth of social cohesion and collective efficacy within their communities to occur (Trojanowicz 1983). An increase in informal controls likewise increases the likelihood that formal authorities, such as COP officers within the community, will be contacted when criminal or deviant activity occurs. Therefore, though it may seem paradoxical, it should be expected that communities with effective COP implementation will in fact have higher rates of reported crime in the short-term.

When it comes to integrating practice with theory, scholars have suggested that community-oriented policing must be cognizant of the characteristics of the community in which it is implemented. COP is also at its strongest when risk factors or influences of crime such as economic disadvantage or varying levels of family disruption are considered (Sherman and Eck 2006; Sozer and Merlo 2013). Implementing any type of formal control, without considering social context may instead lead to a backfire effect which can be manifested in declining public support for police. This has become evident in disorganized locales in Fergusson, Missouri and Baltimore, Maryland, after highly publicized incidents involving police use-of-force decisions and the death of unarmed residents. The influence of some social disorganization factors supports the assertion that there remains a need to assess policing strategies and the extent to which they are implemented within communities. The main findings are addressed below.

Extant research has provided evidence that neighborhoods with more concentrated disadvantage generally experience an increase of crime over a period of time (Bellair 1997; Hart and Waller 2013; Sampson and Groves 1989). While the findings of this study are in support of prior research, it cannot be assumed that disadvantage necessarily causes more crime. Although this is outside the scope of this study, there may be evidence of reciprocal effects between disadvantage and crime, in that, crime and disadvantage are bidirectional in nature—each variable is influenced by the other. In addition, the race variable in this study presented noteworthy findings. While scholars have suggested that social disorganization is far more prominent in communities with a higher percentage of Black or African American individuals, our findings are in support of Hipp (2010) who found no relationship between the percentages of population Black or African American and property crime, but a positive association with violent crime. With more recent literature breaking the stereotype associated with people of color, one may question whether race is merely a proxy for social factors that impact residents who live in cumulatively poor conditions.

We must also consider the influence of family disruption on crime. This proved to be one of the strongest contributors to the full model. There was a significant positive relationship between both property and violent crime rates and the percentage of female-headed households with children under the age of 18 and no husband present. As expressed by Silva (2014), due to significantly less parental monitoring within households, communities with a higher degree of family disruption not only experience weaker social controls, but also predict crime rates to a greater extant. Nonetheless, implementing community policing initiatives within these communities that may drive children away from acts of deviance may alleviate the degree to which crime occurs. This once again addresses the importance of viewing COP as, at best, an indirect crime fighting tool.

4.1. Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Due to the lack of a uniform definition of community policing, as well as a uniform system of implementing strategies within agencies, the measurement constructed for COP implementation in this study may not have been an accurate representation of implementation across all agencies. Moreover, there may be significant differences between small town or rural policing organizations and larger urban areas. Caradelli et al. (1998) suggested that community policing might not be implemented to its full potential in many smaller locales as officers assume community cohesion and social control mechanisms are deeply rooted in such tight knit communities. This type of reliance may translate into less formally structured strategies being implemented.

In addition to differential implementation, the binary approach in coding the implementation of individual COP items (0 = No, 1 = Yes) did not capture the nuances of design and community policing strategies within departments. This limitation may be traced to the data itself. With most community policing questions requiring departments to either answer yes or no, the results of the 2013 LEMAS survey did not acquire optimal explanatory power. Thus, while the questions allow for the basic assessment of whether agencies utilize COP strategies, there is no knowledge of how these strategies are implemented and to what degree. This leads to further problems in addressing similarities across departments. More in-depth investigations may reveal that two departments utilizing the same strategy may in fact be implementing it in a vastly different manner. Police departments may even be implementing strategies that are praiseworthy in nature but yet do not reflect the needs of their communities.

Issues with the measurement of social disorganization can also be addressed. Due to data limitations the theory was not tested at the community level but at the city level. Although it can be argued that the theory should be tested at varied levels in order to contribute to literature, examining the theory under such a broad scope did not allow for the measurement of variables that are generally accounted for in the extended models of the theory (friendship networks, social ties). It is evident that since the re-establishment of the theory, studies conducted on social disorganization incorporate social ties and informal controls such as collective efficacy and cohesion into their models as they play a vital role in achieving the best representation of community social disorganization. However, the inclusion of these variables could have potentially hindered the study, as a precise definition of these concepts is lacking. As explained by Kubrin and Weitzer (2003), this conceptual fuzziness does not allow for a clear understanding of the distinction between certain variables such as social ties and informal controls.

It is also acknowledged that the crime rates used in this study may have been underreported. A shortcoming of the UCR data is that only crimes known to police are included and not reports of victimization. Local police therefore may underestimate the true value of crime given that all individuals in a community report their experiences. It should also be considered that unreported crime may be resolved through internal community action rather than formal law enforcement procedures, and this phenomenon may not be reflected in official crime statistics (Winfree and Newbold 1999). While it is acceptable to use UCR data despite these limitations, future research should consider using National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) data and further comparing the results across data sources. This study utilized a cross-sectional design. Depending on the context of a study, focusing on only one time period may not necessarily produce the most accurate results and may not be able to capture change in demographics, COP implementation and crime rates. As argued by Steenbeek and Hipp (2011) there are pros and cons to using cross-sectional data as opposed to longitudinal data. Still, although longitudinal data is useful in studying long-term effects, it is also important to focus on a central time period in which certain processes occur.

4.2. Policy Implications

The policy implications that can be derived from this exploratory study largely pertain to the consideration of social context in the process of implementing community-oriented policing practices, especially in small cities which might not be as diversified as their counterparts. However, what has become overwhelmingly evident from this present study is that COP implementation, whether examined in a singular manner or as a composite measurement, holds very little predictive power in the context of crime rates. Instead it is clear that some determinants of social disorganization may impact the success of community-policing strategies or prevent them from reaching statistical significance within the models.

As stated by Hughes and Rowe (2007), the community is at the heart of not only political policies but also those involving policing. With this in mind, the central focus of police departments implementing COP should be on improving social controls through the increase of police legitimacy (i.e., increase faith in police) and the decrease in fear of crime. If a disjuncture exists between community members and local police, negative perceptions towards police could persist despite their best efforts (Bain et al. 2014). This gap can be filled if opportunities are provided for communities to be actively involved in implementing community-oriented, strategies rather than merely being informed of the types of community policing initiatives that exist (Kerley and Benson 2000).

In a study focused on community members’ perceptions of police, Crichlow and McGarrell (2015) highlighted the significance of both proper police treatment and quality of police performance on police legitimacy. Not only are members of communities that lack the necessary trust in authority more inclined to disobey the law (Sunshine and Tyler 2003), these communities also generally lack stable social controls that can further impact the success of COP implementation (Warner et al. 2010).

For COP implementation to thrive effectively, community-policing officers must recognize that varied community constituencies (i.e., individual citizens, business associations) bring differing perspectives and ideas to the overall discussion on local problems (Lab 2003). Without the cooperation of both community members and COP officers, problem-solving strategies may not properly target the real issues that communities face. In a study involving the Los Angeles Police Department, many officers within the community police unit admitted to being unaware of what the philosophy specifically entailed or required of them (Glen et al. 2003). Considering the inclusion of training in the implementation process of COP, this should never be the case. However, as noted by Lab (2003) this lack of understanding is the result of the amount of weight still placed on taking reports, criminal codes, making arrests and other similar tasks, whereas more emphasis should instead be placed on problem-solving, identifying intervention strategies and community advocacy.

In addition, the inherent challenges of policing predominantly Black or African American communities cannot be overlooked. Although the argument that racial disparities do not exist within policing is untenable, based on the findings of this study it would be unreasonable to suggest that all small cities with a higher percentage of Black or African American individuals are prone to a higher range of crime rates. Policy should focus on the organizational culture within police departments and prioritize police legitimacy in order to address issues in police-citizen conflict.

5. Conclusions: Directions for Future Research

To address measurement issues and to translate implementation efforts into comparable data across agencies, we recommend that more rigorous research should be conducted with a small sample of police agencies to assess variation in implementation strategies. Although LEMAS provides data on various aspects of policing, the community-policing portion of the survey does not provide a clear picture of an agency’s level of implementation. In addition, there is a need to evaluate officer outlook on the community policing philosophy itself. Research has demonstrated the importance of officer perception and its linkage to community-oriented policing effectiveness (Connell et al. 2008; Sadd and Grinc 1994). As stated by Lab (2003), most crime prevention programs such as COP are heavily reliant on support and input from law enforcement personnel.

Although the implementation process is not standard, there is a degree of consistency in regard to the overarching concept of community-oriented policing. Community policing models implemented within agencies can help to define roles for officers to ensure effective and consistent implementation. Whether proper training is provided is another important concern. Graziano et al. (2013) note that training is the primary vehicle through which change in American policing is orchestrated, yet very little controlled research has been conducted on the subject. We agree that research on training effectiveness, especially in the implementation of such strategies, must be further examined.

We must also ask whether grouping all five of the implementation variables into an index variable provided insight into the nuances of COP. Future research must consider going beyond broad terms and examine whether the pairing or grouping of selected strategies may be more beneficial to some locales. This could be managed through conjunctive analysis techniques, which would represent all possible combinations of implementation that could be observed simultaneously (Hart and Miethe 2011). This might also shed light on the compatibility of particular strategies and whether or not such strategies may be contradictory to the needs of the community.

Regarding social disorganization theory, future research should aim to incorporate the full model of the theory. This would require emphasis on intervening variables and measurement of social cohesion and friendship networks among other variables. As noted by Kerley and Benson (2000), when linking the social disorganization theory to community policing implementation, there is a need for additional measures of community characteristics or processes to be tested in various settings with a rich variety of COP strategies.

The continuing interest in policing strategies and crime control is likely to develop more insight into unanswered questions regarding community-level explanations of crime. The null findings concerning COP implementation within this study and others are therefore not disheartening but instead are a part of an empirical process of trial and error. What is evident, however, is that population or community demographics play a salient role, not only in the implementation process, but ultimately on the success of community-oriented policing. Therefore, law enforcement agencies might consider the social context of the communities they serve and implement policing strategies that are tailored with these characteristics in mind. While community policing’s impact on crime is inconclusive (Gill et al. 2014; Sozer and Merlo 2013), research pertaining to policing and community relations is still needed. Given the current state of policing, and questions pertaining to police legitimacy, police should be encouraged to build stronger relationships with the public, and law enforcement agencies are encouraged to also take community factors into account when implementing COP.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lisa Dario, David Kalinich and Rachel Santos for their assistance with an earlier version of this paper.

Author Contributions

Kimberly Przeszlowski conceptualized this paper and conducted the analyses. She also prepared the tables and figures and drafted the results section of the manuscript. Vaughn Crichlow provided intellectual insight and guidance throughout the project. He wrote and edited major portions on the front end of the paper, as well as the Discussion and Conclusion sections. Both authors participated in the final review and revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, Richard E., William M. Rohe, and Thomas A. Arcury. 2005. Awareness of community-oriented policing and neighborhood perceptions in five small to midsize cities. Journal of Criminal Justice 33: 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, Martin A. 2006. A spatial analysis of crime in Vancouver, British Columbia: A synthesis of social disorganization and routine activity theory. The Canadian Geographer 50: 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, Andy, Bryan K. Robinson, and Jim Conser. 2014. Perception of policing: improving communication in local communities. International Journal of Police Science and Management 16: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellair, Paul E. 1997. Social interaction and community crime: Examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology 35: 677–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogden, Michael, and Preeti Nijhar. 2005. Community Policing National and International Models and Approaches. Portland: Willan. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. 1994. Understanding Community Policing: A Framework for Action; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

- Bursik, Robert J., and Jim Webb. 1982. Community change and patterns of delinquency. American Journal of Sociology 88: 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradelli, Albert P., Jack McDevitt, and Katrina Baurn. 1998. The rhetoric and reality of community policing in small and medium-sized cities and towns. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 21: 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Lawrence E., and Marcus Felson. 1979. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review 46: 588–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Nadine M., Kristen Miggans, and Jean Marie McGloin. 2008. Can a community policing initiative reduce serious crime? A local evaluation. Police Quarterly 11: 127–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichlow, Vaughn J., and Edmund F. McGarrell. 2015. Exploring police legitimacy perceptions among Arab and Chaldean business owners in Detroit. Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice and Criminology 3: 139–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gau, Jacinta M. 2014. Unpacking collective efficacy: The relationship between social cohesion and informal social control. Criminal Justice Studies 27: 210–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Charlotte, David Weisburd, Cody W. Telep, Zoe Vitter, and Trevor Bennett. 2014. Community-oriented policing to reduce crime, disorder and fear and increase satisfaction and legitimacy among citizens: A systematic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology 10: 399–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, Russell W., Barbara R. Panitch, Dionne Barnes-Proby, Elizabeth Williams, John Christian, Matthew W. Lewis, Scott Gerwehr, and David W. Brannan. 2003. Training the 21st Century Police Officer: Redefining Police Professionalism for the Los Angeles Police Department. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano, Lisa, Dennis P. Rosenbaum, and Amie M. Schuck. 2013. Building group capacity for problem solving and police-community partnerships through survey feedback and training: A randomized control trial within Chicago’s community policing program. Journal of Experimental Criminology 10: 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Jack R., and William V. Pelfrey. 2001. Shifting the balance of power between police and community: Responsibility for crime control. In Critical Issues in Policing, 4th ed. Edited by Roger G. Dunham and Geoffrey P. Alpert. Prospect Heights: Waveland, pp. 435–65. [Google Scholar]

- Grinc, Randolph M. 1994. “Angels in marble”: Problems in stimulating community involvement in community policing. Crime and Delinquency 40: 437–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Timothy C., and Terance Miethe. 2011. Violence against college students and its situations contexts: Prevalence, patterns, and policy implications. Victims and Offenders 6: 157–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Timothy C., and Jeremy Waller. 2013. Neighborhood boundaries and structural determinants of social disorganization: Examining the validity of commonly used measures. Western Criminology Review 14: 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, Perry R., Isabella McMurray, Charlotte Brownlow, and Bob Cozens. 2014. SPSS Explained. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp, John R. 2010. A dynamic view of neighborhoods: The reciprocal relationship between crime and neighborhood structural characteristics. Social Problems 57: 205–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Gordon, and Michael Rowe. 2007. Neighbourhood policing and community safety: Researching the instabilities of the local governance of crime, disorder and security in contemporary UK. Criminology and Criminal Justice 7: 317–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaylen, Maria T., and William Pridemore. 2013. Social disorganization and crime in rural communities. British Journal of Criminology 53: 905–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelling, George L., and Mark H. Moore. 1988. The Evolving Strategy of Policing, Perspectives on Policing. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Kerley, Kent R., and Michael L. Benson. 2000. Does community oriented policing help build strong communities? Police Quarterly 3: 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubrin, Charis E., and Ronald R. Weitzer. 2003. New directions in social disorganization theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 40: 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lab, Steven P. 2003. Community policing and crime prevention in the United States. In International Perspectives on Community Policing and Crime Prevention. Edited by Steven P. Lab and Dilip K Das. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, Vivian B., Joseph B. Kuhns, and Paul Friday. 2009. Small city community policing and citizen satisfaction. Policing 32: 574–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Edward R., and Stephen P. Mastrofski. 2000. Patterns of community policing. Police Quarterly 3: 4–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Edward R., Joseph B. Kuhns, Craig D. Uchida, and Stephen M. Cox. 1997. Patterns of community policing in nonurban America. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 34: 368–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, Melissa Schaeffer. 2010. Understanding community policing as an innovation: Patterns of adoption. Crime and Delinquency 56: 564–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustain, Elizabeth E., and Richard Tewksbury. 1998. Predicting risks of larceny theft victimization: A routine activity analysis using refined lifestyle measures. Criminology 36: 829–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, D. Wayne, and Jeff M. Chambers. 2000. Social disorganization outside the metropolis: An analysis of rural youth violence. Criminology 38: 81–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelfrey, William V. 2004. The inchoate nature of community policing: Differences between community policing and traditional police officers. Justice Quarterly 21: 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisig, Michael D., and Roger B. Parks. 2004. Can community policing help the truly disadvantaged? Crime and Delinquency 50: 139–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Sunghoon, and Willard Oliver. 2005. Effect of community policing upon fear of crime: Understanding the causal linkage. Policing 28: 670–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, Dennis P., and Arthur J. Lurigio. 1994. An inside look at community policing reform: Definitions, organizational changes, and evaluation findings. Crime and Delinquency 40: 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadd, Susan, and Randolph Grinc. 1994. Innovative neighborhood oriented policing: An evaluation of community policing in eight cities. In The Challenge of Community Policing: Testing the Promises. Edited by Dennis P. Rosenbaum. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Robert J. 2012. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effects. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Robert J., and Dawn Jeglum Bartusch. 1998. Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: The neighborhood context of racial differences. Law and Society Review 32: 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., and W. Bryon Groves. 1989. Community structure and crime: Testing social disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology 94: 774–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., and Stephen W. Raudenbush. 1999. Systemic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology 105: 603–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquency in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Lawrence W., and John Eck. 2006. Policing for crime prevention. In Evidence-Based Crime Prevention. Edited by Lawrence W. Sherman, Doris Layton MacKenzie, David P. Farrington and Brandon C. Welsh. New York: Routledge, pp. 331–403. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Braulio A. 2014. Social Disorganization and Crime. Latin American Research Review 49: 218–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogan, Wesley G. 2006. Police and the Community in Chicago. New York: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Douglas A., and Roger G. Jarjoura. 1988. Social structure and criminal victimization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 25: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, Peter. 2009. Understanding community policing. Policing 32: 261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozer, Mehmet Alper, and Alida V. Merlo. 2013. The impact of community policing on crime rates: Does the effect of community policing differ in large and small law enforcement agencies. Police Practice and Research 14: 506–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbeek, Wouter, and John R. Hipp. 2011. A longitudinal test of social disorganization theory: Feedback effects among cohesion, social control, and disorder. Criminology 49: 833–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunshine, Jason, and Tom R. Tyler. 2003. The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and Society Review 37: 513–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanowicz, Robert C. 1983. An evaluation of a neighborhood foot patrol program. Journal of Police Science and Administration 11: 410–19. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, Craig D., Marc L. Swatt, Shellie E. Solomon, and Sean Varano. 2014. Neighborhoods and Crime: Collective Efficacy and Social Cohesion in Miami-Dade County. Final Report submitted to the National Institute of Justice. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Barbara D. 2007. Directly intervene or call the authorities: A study of forms of neighborhood social control within a social disorganization framework. Criminology 45: 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Barbara D., Elizabeth Beck, and Mary Ohmer. 2010. Linking informal social control and restorative justice: Moving social disorganization theory beyond community policing. Contemporary Justice Review 13: 355–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburd, David, and Chester Britt. 2007. Statistics in Criminal Justice. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, L. Edward, and Ralph A. Weisheit. 2004. Patterns of rural and urban crime: A county-level comparison. Criminal Justice Review 29: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentz, Erica, and Kristyn Schlimgen. 2012. Citizens’ perceptons of police service and police response to community concerns. Journal of Crime and Justice 35: 114–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfree, Thomas L., and Greg Newbold. 1999. Community policing and the New Zealand Police: Correlates of attitudes toward the work world in a community-oriented national police organization. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 22: 589–618. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | We also conducted a poisson regression with these data to determine whether this would make a difference in the observed relationships. However, there were no noteworthy differences found when comparing the findings from the OLS model and the additional analyses. Additional analyses can be provided upon request. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).