Abstract

While the importance of pursuing integrated population, health and environment (PHE) approaches and ensuring their sustainable expansion to regional and national levels have been widely affirmed in the development field, little practical experience and evidence exist about how this can be accomplished. This paper lays out the systematic approach to scale up developed by ExpandNet and subsequently illustrates its application in the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin (HoPE-LVB) project, which is an integrated PHE project implemented in Uganda and Kenya from 2012–2017. Results demonstrate not only the perceived relevance of pursuing integrated development approaches by stakeholders but also the fundamental value of systematically designing and implementing the project with focused attention to scale up, as well as the challenges involved in operationalizing commitment to integration among bureaucratic agencies deeply grounded in vertical departmental approaches.

1. Introduction

Much development effort has focused on funding and organizing projects that test innovative approaches as the basis of subsequent large-scale implementation. However, while such projects have typically achieved remarkable results on a small scale, they have not been so successful in reaching beyond initial target areas and are often not sustained in places where implemented. As the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations 2016) and Paris Climate Agreement (United Nations 2015) move from global to national policy and program implementation, there is need to test more holistic development efforts and approaches that cross traditional sectoral boundaries. Therefore, change is needed not only in practicing a greater degree of integration among activities but also to ensure a focus on explicit strategic planning and management of scaling up. Consensus is building that simply developing a good model or approach and hoping it will spontaneously achieve widespread adoption is not sufficient (World Health Organization 2007; ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2011; Cooley and Ved 2012; Linn 2011). Instead, initiatives that strategically build on the work of existing systems and institutions, using knowledge about the determinants of success with scale-up processes are needed (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2009; Aichatou et al. 2016; Keyonzo et al. 2015).

This paper describes a systematic approach to scaling up developed by ExpandNet that begins from the earliest stages of project design and progresses to planning for and managing scale up (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2009, 2010, 2011). It then highlights key aspects of the experience of the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin project (hereafter HoPE-LVB or just HoPE) an integrated population, health and environment project implemented since 2012 in Kenya and Uganda (Ghiron et al. 2014; Pathfinder International 2015). HoPE applied the ExpandNet approach over the course of planning, implementation, and scale up and the paper provides examples of outcomes that resulted from this application.1

2. Materials and Methods

The authors of this paper led, managed and monitored the HoPE-LVB Project from 2012–2017 and one is co-author of the ExpandNet/WHO guidance tools who has been providing technical support to the project team in their application since it began. The experience and analysis laid out in this paper represent the authors’ reflections as participant observers in the multi-year process of implementing and scaling up HoPE interventions. Results presented are informed by analysis of routine service statistics, when available and reliable, and continuous qualitative and quantitative project monitoring over the entire project period that included sector-specific health and environment-related indicators. For specific health and population-related outcomes, the HoPE team sought to capture changes in uptake and use of family planning, use of facility-based, skilled birth attendance, childhood immunization, and water, sanitation and hygiene-related changes such as latrine coverage among others. For environmental conservation-related change the team monitored the demarcation and protection of fish breeding sites, use of and conversion to sustainable fishing and farming techniques, tree planting, changes in crop yield and fish catch, and use of energy saving stoves among others. In most cases these data were collected by community-level stakeholders with support from project personnel, and substantial efforts were made to feed the data back into local planning processes and decision-making at local and higher administrative levels.

Baseline, midline and endline evaluations were undertaken but did not capture the same measures with the same populations and therefore only absolute numbers are reported when available. Evaluation methods included participatory rural appraisal, rapid assessment in expansion areas, environmental surveys, focus group discussions, periodic PHE-related policy and program analysis based on key informant interviews and participation in multiple meetings at local, district/county, national and regional East Africa levels. The ExpandNet team visited the Kenya and Uganda teams two- to three times per year over the five-year project period, and the authors worked via distance communication in the intervening times.

3. ExpandNet’s Systematic Approach to Scale Up

ExpandNet is an informal network of public health professionals founded in 2003 to advance the science and practice of scaling up. ExpandNet’s systematic approach to scaling up was developed between 2001 and 2011 and is based on extensive practical experience, application and a broad review of literature from a range of disciplines. Two key tenets of ExpandNet’s systematic approach to scaling up are that: (1) successful scale up requires explicit, ongoing attention; and (2) that it is never too soon to apply such a focus. This implies that from the earliest stages, pilot projects should build an understanding of what makes scaling up succeed into their design and overall approach and make project management decisions consistent with that understanding throughout implementation.

ExpandNet’s systematic approach is based on a conceptual framework2 and the following definition for scaling up (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2009, 2011):

“Deliberate efforts to increase the impact of successfully tested pilot, demonstration or experimental projects to benefit more people and to foster policy and program development on a lasting basis.”

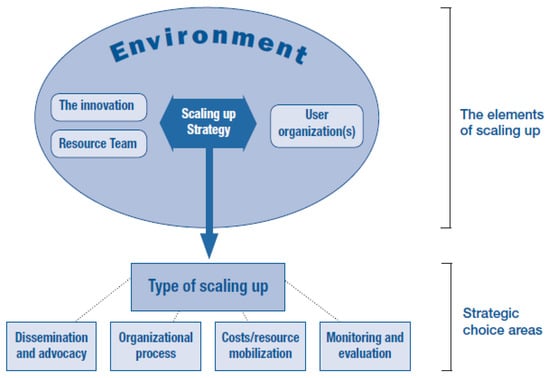

ExpandNet/WHO’s conceptual framework for scaling up (Figure 1) (Simmons et al. 2007; ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2010) takes a systems perspective to help implementers identify the key elements of scaling up, including: the package of interventions that is to be scaled up (called the innovation3 (Rogers 1995)); the user organization(s) that is expected to adopt and implement the innovation on a larger scale; the resource team that has been involved in the development and testing of the innovation and/or seeks to promote its wider use; the larger socio-political, bureaucratic, policy and economic context in which scaling up takes place; and the scaling-up strategy which is the means by which the innovation is adopted, transferred or otherwise promoted. The scaling-up strategy involves making strategic choices about: the different types of scaling up, of which expansion and institutionalization are the most essential, how to approach dissemination and advocacy, how to organize the scaling-up process, the role of capturing cost information and the need to mobilize resources, and how to monitor and evaluate scale up.

Figure 1.

The ExpandNet/World Health Organization (WHO) scaling-up framework (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2010).

The systems perspective entails gaining clarity on how the elements and strategic choices in the scaling-up framework interact and how to strive for balance among them in developing a scaling-up strategy. This implies for example that expectations about how fast or how far to scale up have to be calibrated with the complexity of the innovation, the capacities of adopting organizations to implement it and the capacities of the team who will support the process.

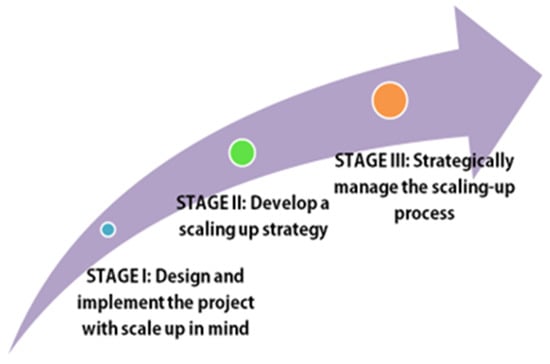

Figure 2 illustrates the stages of ExpandNet’s systematic approach to scaling up which begins at Stage I with a pilot project4 that is designed and implemented to focus on sustainability and scalability, anticipating future scale up if proven successful. Stage II focuses on the development of a scaling-up strategy for interventions that have demonstrated signs of their effectiveness, ideally through a participatory process with key stakeholders. Stage III calls for strategically managing the scaling-up process, which tends to be the lengthiest, most labor-intensive stage. Projects that proceed through such a process are more likely to yield better scaling-up results than ones that implement the process less systematically.

Figure 2.

ExpandNet’s systematic approach to scaling up.

3.1. Stage I

ExpandNet/WHO’s guidance tool “Beginning with the end in mind: Planning pilot projects and other programmatic research for successful scaling up” (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2011) describes key considerations for Stage I. It provides 12 recommendations (Table 1) to help researchers, policy planners, program managers, technical-assistance providers, implementers, donors and others to design pilot or other programmatic research efforts and implement them for lasting and larger-scale impact. Taken together, the guide’s 12 recommendations represent a major paradigm shift from the way projects are typically undertaken. While all of the recommendations are important, several key ones are described in further detail below that deserve special attention in this paper because they constitute areas of critical learning from the HoPE scale-up experience. Ghiron et al. (2014) provide insights and critical learning that emerged from applying the ExpandNet/WHO recommendations for designing and implementing HoPE-LVB for scale up during the Stage I pilot. Additional information on specific steps the HoPE project took to address the 12 recommendations can be found in the HoPE toolkit (Pathfinder International 2017b).

Table 1.

ExpandNet/WHO’s 12 recommendations for Beginning with the end in mind (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2011).

3.2. Stage II

The second stage of ExpandNet’s systematic approach emphasizes that once piloted interventions show evidence of success, it is important to undertake a strategic planning exercise. The nine-step guide (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2010) can be used to develop a comprehensive scale-up plan. Implementing this approach benefits from the voices of multiple stakeholders, including those who are most familiar with: (1) the experience of implementing the intervention package, and can help identify the most effective and relevant components of the package to be scaled up and how the package could be simplified; (2) the scale up setting and those who are intended to implement the intervention package on a larger scale, including key actors who can support—and might hinder—the process; and (3) the larger contextual environment that influences the scaling-up process.

Application of the nine-step approach involves asking a series of relevant questions that are based on the ExpandNet/WHO framework (Figure 1) and are contained in the Nine-step guide and associated worksheets (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2010). The nine steps appear in Table 2. Areas of analysis typically include: what are the implications of the complexity of the intervention package; how fast can expansion reasonably be expected to proceed given the characteristics of the innovation and the scale-up setting; and what steps are needed to ensure that the package is institutionalized in budgets, plans, frameworks, regulations, norms, laws and policies.

Table 2.

ExpandNet/WHO’s Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy.

3.3. Stage III

The third stage of strategically managing the scaling-up process is often the most neglected, and yet requires the greatest skill, effort and resources (Perlman Robinson et al. 2016; Cooley and Ved 2012). Using the ExpandNet/WHO scaling-up framework during this stage to revisit and revise the scaling-up strategy based on more recent developments and to take advantage of emerging opportunities is critical (Simmons et al. 2011). Such analyses of progress can help the team supporting scale up to systematically identify and prioritize necessary actions and gaps in the approach. Scaling up is a complex, non-linear process, and a framework helps ensure a comprehensive assessment of critical issues. Difficult decisions need to be made about: (1) how best to proceed given undoubtedly limited resources; and (2) which tradeoffs are most appropriate so as not to jeopardize the goal of sustainable scale up. Ongoing analysis of monitoring results, and identifying where periodic evaluation activities could help understand implementation is an important component of ensuring sustainable scale up. Given that funding for research and monitoring often drops off dramatically after a pilot is completed, a convincing case needs to be made to capture information about whether appropriate fidelity has been maintained or whether the innovation has been so greatly adapted during implementation that it no longer can reasonably be expected to have the same outcomes as observed in the pilot. These and many more such issues arise during the management of scale up.

HoPE’s collaboration with ExpandNet represented a first opportunity to jointly apply all three stages of the systematic approach to scaling up in a hands-on way, from the earliest stages of design (Ghiron et al. 2014) through to management of the early scaling-up process. While ExpandNet’s initial experience grew out of supporting scale up of family planning and other reproductive health innovations, the framework and guidance provided are generic in nature and can be applied to projects addressing a wide range of thematic and technical areas. This is because scaling up is primarily a managerial, political and organizational development issue rather than tied to a particular set of technical interventions. Thus they could be readily used to support the scale up of a PHE project without major adaptation. Presented below is an overview of relevant results arising from the application of ExpandNet’s systematic scale up approach over five years of HoPE implementation, followed by key lessons emerging at each stage of this experience.

4. Background on the HoPE-LVB Project

HoPE began as a result of the interest of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur and David and Lucile Packard Foundations and USAID to jointly fund an integrated population, health and environment initiative in the Great Lakes region of East Africa. The PHE approach is loosely defined as integrating efforts to increase access to, utilization, and quality of family planning services while simultaneously addressing other pressing health and environmental conservation concerns to build greater synergies for the environment and human welfare than single-sector approaches could accomplish alone. Both USAID and the Packard Foundation had previously funded integrated PHE work, notably in Madagascar (Gaffikin 2008) and the Philippines (De Souza 2008; Yavinsky et al. 2015), and were interested to see if this new effort could go on to have even greater impact in the region if implemented with a scaling-up focus from the outset. While integrating PHE had up to then shown promise as an approach to achieving sustainable development on a relatively small scale, at that point few beyond the Philippines and Madagascar had demonstrated success with institutionalization and expansion beyond initial target areas. Having been familiar with, and in the cases of the MacArthur and Packard Foundations having funded the work of ExpandNet, the donors requested that they work with HoPE to ensure that a scale-up focus permeated the initiative. An initial three-year grant was made to support Pathfinder International—a sexual and reproductive health and rights-focused organization—to support work on the ground in Kenya and Uganda in close partnership with local conservation-focused NGOs (in Uganda—Ecological Christian Organization (ECO) and Conservation through Public Health (CTPH); in Kenya—OSIENALA—Friends of Lake Victoria and Nature Kenya). Meanwhile USAID supported ExpandNet involvement and other technical assistance through existing cooperative agreements.

Initially envisaged as a pilot (Phase I; 2012–2014), HoPE’s strategic objective was to “develop and demonstrate/test a model for PHE integration in lake basin sites in Kenya and Uganda that could be adapted and scaled up in communities, as well as by local, national and regional governments”. There was an understanding between the donors and Pathfinder International that if the pilot phase was considered successful, there would be a possibility for continued funding to support a scaling-up phase.

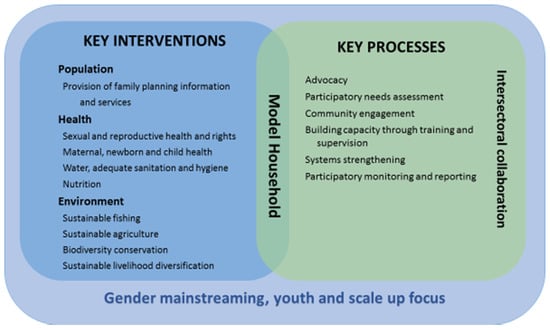

The HoPE pilot worked in one lakeside/island sub-county in each of two districts—Mayuge and Wakiso—in Uganda, and in two sub-counties of Homa Bay County in Kenya. Key components of the HoPE integrated PHE model are presented in Figure 3. To implement the key population, health or environmental components, the project worked in a participatory way with existing community-based groups that included beach management units; Village Health Teams/Community Health Workers (volunteers); and women’s, youth, and farmers’ groups and helped establish young mothers’ groups and school PHE clubs. HoPE worked with the existing health and environment-oriented public sector service systems/officials to strengthen capacities to deliver health (such as family planning, skilled delivery, etc.) and environmental services (such as tree planting, energy saving stove construction, etc.). At the same time there was a strong focus on educating and empowering community groups to understand and share information on the linkages between population, health and the environment and to refer community members for services. The project simultaneously worked with natural resource/environment/fisheries officials, community leaders and groups to institute new conservation activities such as sustainable agriculture and fisheries interventions, and to renew the focus on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Throughout these capacity-building activities, there was a consistent focus on orienting groups and individuals to understand “the how” and “why” for working in more integrated ways across the sectors (Pathfinder International 2015). While other predecessor PHE projects may have accomplished any combination of the above, what was new about the HoPE approach was its concurrent focus on scale up. This meant that everyone participating was made aware that they were pioneering an approach that, if successful, would be scaled-up.

Figure 3.

Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin (HoPE-LVB) integrated population, health and environment model components.

Two key components of the HoPE model included: (1) the establishment of PHE model households who were committed to practice and teach other community members and decision makers about HoPE’s environmental and health interventions; and (2) a strong focus on intersectoral collaboration and advocacy with local, district/county, national and regional level decision-makers in the three sectors of population, health and the environment. The latter included cultivating multi-sectoral “PHE Champions” at all these levels to build momentum for expanding application of the PHE integrated approach in East Africa (Pathfinder International 2015, 2017a, 2017b).

5. Stage I: Designing and Implementing the HoPE Pilot with Future Scale up in Mind

Given that the collaboration between ExpandNet and HoPE began after proposal submission but before project implementation began, there was an opportunity to review the proposed plans to better facilitate future scale up, if approaches proved successful. The first step was to undertake a participatory “scoping exercise” to engage community groups in project sites, and national and regional level stakeholders, in discussions about the proposed interventions. The team met with key government institutions which, if successful, could potentially adopt and implement the interventions on a larger scale. These included the Uganda and Kenya Ministries of Health, National Environmental Management Authority, Population Secretariat/National Council for Population and Development, district/county officials, elected officials and more. Stakeholder meetings took place from the grassroots up to the regional level of the East African Community’s Lake Victoria Basin Commission level. The Commission had early on been identified as a key advocacy target, given their role then in leading the five partner states of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda5 in harmonizing and operationalizing sustainable development policies and programs throughout the basin (Pathfinder International 2017a).

The scoping enabled the project team to brief stakeholders on the project design and obtain stakeholder insight on pressing needs as well as input on the most appropriate and sustainable implementation modalities. This was in line with Recommendations 1 and 7 from the Beginning with the end in mind guidance, which emphasizes ensuring a participatory process involving key stakeholders and testing the innovation under routine operating conditions and existing resource constraints of the system respectively (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2011).

Considering the information gathered, the scoping analyzed how best to implement initially proposed interventions from a sustainability and scale up perspective. A few major shifts occurred. For example, originally the project team was going to conduct training in environmental conservation activities only with project communities. Instead, they switched to an approach that would actively involve district/county level officials whose job responsibilities already included conducting such training but they either lacked the capacity, the resources, or both.

As implementation moved ahead, the HoPE team sought to establish multi-sectoral project steering committees in both countries with the goals of helping to guide the project, ensuring continued stakeholder dialogue, engagement with and cultivation of champions, as well as to provide a vehicle to reach the various line ministries and other participating institutions with key project learning. However, instead of creating a steering committee bound to the project, the Kenyan team advocated for a Homa Bay County PHE Steering Committee to ensure it would be sustained beyond the project’s lifespan. The Homa Bay Governor immediately saw the value of the PHE approach to achieving sustainable development for his county and supported the initiative. This decision, plus composition and functionality yielded some of the productive outcomes described below under Stage III.

In keeping with ExpandNet/WHO Recommendations 9 and 10, HoPE built a strong focus on advocacy into its work plan and budget from the outset to ensure that key aspects of the political, policy and budgetary environment would increasingly move towards supporting integrated PHE work. This entailed active participation in meetings at the local/community, district/county, national and even international levels with stakeholders from the field of population/reproductive health, maternal and other global health, environmental conservation/climate mitigation, food security, and research and academic institutions. Some of these meetings were organized by or with the project—such as PHE conferences—while others were routine standing meetings—such as Uganda’s District Health Management Team meetings. In addition, per Recommendation 11, visits to HoPE field sites were frequently organized for a wide array of stakeholders, including Members of Parliament, so they could observe the project in action and learn about the benefits of the integrated approach directly from its beneficiaries and implementers.

Another key aspect of applying Recommendation 7 was HoPE’s mobilization of existing community-based institutions, service providers and leaders as multi-purpose resource persons to implement the project, as opposed to creating new cadres of workers or parallel service delivery systems. HoPE built the capacity of these resource persons to implement integrated PHE at the community and higher levels with the understanding that they could use their learning to support the adoption and scale up of HoPE approaches more widely to other sub-counties/districts. Nonetheless, profound resource constraints faced in the public sector, including both the environment sector and health system meant that it would not have been possible to accomplish much without some infusion of additional resources. Even when these systems succeed in getting sector-specific (vertical) budgetary allocations for implementation at the district/county or lower levels, there is no assurance those funds will ultimately be released to achieve agreed-upon goals. Still, representatives of government institutions at the various levels who had gained PHE implementation experience as a result of HoPE’s focus on building system capacity for future scale up had become champions of expanding the approach. These champions sought opportunities to replicate the interventions and would play an important role once funding for scale up was secured.

Although the scale-up perspective strongly influenced the design and implementation of the HoPE project, ultimately not all of the Beginning with the end in mind recommendations (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2011) could be addressed through the course of the pilot. Some were difficult to implement given constraints on the project team’s time, capacities and budget. For example, one recommendation suggests testing the interventions in the range of settings that characterize eventual scale-up sites. In Uganda the project decided at the outset of the pilot to only work with island communities of Lake Victoria since they are the most marginalized and in need, whereas scaling up would inevitably address mainland sites as well. As a result, some stakeholders perceived the model as only relevant for island settings, whereas this was not the case. Overall, however, the project was implemented in ways that differed substantially from typical PHE projects—and in fact from most global health and development projects—in terms of how and with whom it was implemented. And these shifts in approach set the project on a solid path for the next stage, which is discussed below.

6. Stage II: Developing Scaling-Up Strategies for HoPE Interventions in Kenya and Uganda

As the pilot stage was drawing to a close, the project conducted a review (referred to hereafter as the midline) through a series of key informant interviews, analysis of routine service statistics and ongoing project monitoring data for selected service provision indicators, as well as an independent ecological assessment. The review showed widespread improvements on several sector-specific and integrated (also called value-added) indicators. In terms of population and health, pilot sites experienced a steep uptake in family planning usage, critical increases in facility-based, skilled birth attendance, and substantial increases in latrine coverage and other water and sanitation behaviors. In terms of environmental conservation, the construction and installation of energy-saving stoves took off rapidly, thanks to HoPE’s efforts to build a cadre of community-based skilled artisans. Tree nurseries were highly successful in providing environmentally-friendly incomes and led to marked efforts in tree-planting. Fish breeding sites were newly demarcated and policed to ensure that fish would reach maturity to ensure sustainable harvest and use of illegal fishing gear was strongly discouraged. Capacity for implementing sustainable agriculture and agroforestry techniques had been built at the community and district/county levels. Changes in a few key indicators are described further below.

The results of the review were shared with project donors at a meeting to decide whether a second phase focused on scale up should be funded. The project team and donors concluded that the HoPE interventions had been successful and warranted scale-up and that the HoPE team could formulate a proposal. Therefore, ExpandNet worked with the project team to first undertake internal scaling-up strategy development exercises in both countries, using the nine-step process (see Figure 1) (ExpandNet and World Health Organization 2010). Applying the nine-step approach internally prior to holding the multi-stakeholder workshop was useful for two reasons: (1) it helped the team formulate ideas to shape the scale-up proposal; and (2) it familiarized the team more deeply with the scaling-up framework and how the nine-step methodology is applied. The new proposal subsequently focused on both expanding the number of implementation sites while also working to institutionalize HoPE approaches in governmental, non-governmental and community-based organizations in the two countries.

After receiving the scale-up grant, the HoPE project team determined that an essential first action was to repeat the nine-step process, now with a diverse array of stakeholders who could contribute recommendations for how HoPE approaches could reach more people and influence policies and programs. National workshops were planned for Kenya and Uganda in early 2015 with a range of participants from the local to national levels. These included line ministry representatives from the sectors of population, health and environment, NGOs, donors, technical agencies, implementers, parliamentarians, etc. Some had been involved in HoPE since the outset and were already self-identified PHE champions, while others were hearing of the project and PHE for the first time. Explicit attention was given to invite potential implementers from governmental, non-governmental, and technical assistance agencies who could collaborate on scale up. Given the HoPE donors’ request for the expansion phase to initiate work in the biodiversity sensitive Yala wetlands ecosystem area of Siaya County, Kenya, several institutions working in Siaya were invited. In Uganda, the team decided to expand from a few parishes in one sub-county in each of the two districts to cover all parishes in the entire sub-county. Thus, no new districts were invited to participate in the strategy workshops, and instead the focus was on stakeholders from the two districts plus the national level.

The Stage II application of ExpandNet/WHO’s nine-step approach in both countries resulted in a rich and diverse set of recommendations from participants on how the scaling-up process could advance. Some pertained to how the resource team could be expanded to include new partner organizations and how to get broader participation of existing partners, like the Ministry of Health, to help institutionalize HoPE approaches more widely within their programming. Ideas for new potential technical partners, for mobilizing resources from the private sector and for ensuring PHE-friendly policy and political will all emerged. More generally, these exercises served to generate substantial energy around the relevance of the PHE approach as a means for sustainable development in East Africa. Participants both new to HoPE and those already familiar were in strong agreement that the integrated PHE approach was highly relevant and merited wider expansion and institutionalization within both countries. The ExpandNet facilitators noted that in comparison to other nine-step exercises they had conducted, the quality of stakeholders’ recommendations reflected substantial commitment to the PHE approach, quite likely due to the strong foundation laid during the first stage application of the recommendations of “Beginning with the end in mind”.

In Uganda, the strategy-development workshop generated commitment from a pivotal new stakeholder group, the Ministry of the East African Community Affairs (MEACA). Up to that point, MEACA had not heard much about HoPE or the PHE approach, but during the meeting the representative became convinced to support wider adoption. Similarly, at the Kenya meeting, there was strong representation of the government’s National Council for Population and Development (NCPD). This could be attributed to NCPD’s multi-year focus on PHE and the high involvement of the Homa Bay NCPD representative in supporting the PHE Steering Committee, which is comprised of representatives from multiple line ministries and other stakeholders. NCPD’s participation resulted in the recommendation that they continue to play a key role in expanding HoPE’s PHE approach in Kenya’s 47 counties. The HoPE project team was surprised by the excitement, breadth and depth of the recommendations. The Kenya team consolidated 300+ recommendations into 48 overarching ones that were then circulated to all participants for review before wider dissemination. A similar process took place with the results of the Uganda meeting. Some key categories of recommendations to emerge included: the need to expand the number of funders and implementing organizations with capacity to work on PHE integration; to ensure that integrated PHE approaches were mainstreamed in government work plans and budgets; and to make use of HoPE-trained resource persons to support the scaling-up process. For a complete list of the recommendations that came out of the scaling-up strategy meetings in Kenya and Uganda, see the supplementary materials.

7. Stage III: Strategic Management of HoPE’s Early Scaling-Up Process

In the months following the scaling-up strategy development workshops, the project teams in Kenya and Uganda followed up on many of the key recommendations made by stakeholders. These included pursuing possible collaboration with new community-based and non-governmental organizations, as well as strengthening work with governmental partners from the local to the national and even regional East African levels. In the scale-up proposal the HoPE team had identified expansion sites based on the internal strategy development exercise. Thus expansion efforts to new sites (as shown in Table 3) were initiated, but a major change took place in the approach to PHE capacity building in these areas. Whereas in the pilot phase the HoPE team had taken responsibility for capacity building to implement health and environmental interventions, in the scale-up phase they played a more facilitative role. This meant supporting the community and government leaders who had been implementing PHE since the pilot to become trainers—a role that they heartily embraced. This adaptation and simplification of the model during scale up had multiple spinoff effects in that community and government capacity was strengthened to further replicate HoPE approaches, and the likelihood for enhanced sustainability grew.

Table 3.

HoPE-LVB expansion from pilot to scale-up sites.

For example, members of the multi-sectoral Homa Bay PHE Steering Committee created during Stage I were mobilized to support the establishment of a counterpart steering committee in Siaya County where HoPE was expanding. This “sisi-kwa-sisi” (meaning “us to us” in Swahili) process markedly sped up the work of the new committee since the Homa Bay team had already learned a great deal about how to strengthen integrated PHE work within the county planning process. For example, Siaya County was able to insert several integrated PHE components into their County Integrated Development Plan for the next program and budget year as a result of this cross-county collaboration and HoPE support. Such collaboration was a key recommendation to come out of the strategy-development workshop and the rapidity and marked success of Siaya’s replication using the sisi-kwa-sisi approach constituted important scaling-up learning.

Scaling up in Uganda looked very different than in Kenya, given that the decision was made to expand within the initial two pilot districts, and within them, mostly more widely within the pilot subcounties. Since the project sites were Lake Victoria islands, but their districts’ administrative offices were both on the mainland, district officials who had become HoPE trainers and champions identified a need for technical support from HoPE to help create PHE demonstration villages where interventions could be observed nearby their headquarters. This sign of government ownership and institutionalization represented a key step towards positioning them to scale up the PHE approach to other sub-counties in their districts.

During scale up of HoPE approaches, the project team and resource persons continued to implement successful interventions in the original pilot sites while expansion to new areas was undertaken with less intensive support. Such a simplification included new expansion sites being mentored less by the project team and more by HoPE resource persons who had been part of the pilot. Overall, however, efforts were made in the expansion sites to adhere as much as possible to implementing the integrated package that had been tested during the pilot, not only to ensure fidelity to the model but also because having begun with the end of scale up in mind, the package was already minimalist, even while it addressed several needs that had been identified during Stage I scoping and rapid assessment in Stage III expansion sites.

Table 4 indicates that considerable progress (in absolute numbers) was made by midline on key maternal/neonatal health, family planning and environmental conservation indicators. By endline, however, Uganda experienced a dip in the average monthly number of new and repeat FP revisits and facility-based deliveries, which could point to some saturation of long-term contraceptive method use that would affect both of these indicators. This is especially likely since the Uganda expansion was largely in the same sub-counties where the pilot functioned. More research would be needed to have definitive answers.

Table 4.

HoPE Project family planning, maternal/neonatal health and environmental conservation outcomes.

HoPE-LVB worked with the Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC) as a key regional advocacy platform to scale up the PHE approach and ensure its adoption by the LVBC policy and decision making organs. Consistent engagement since 2012 to help institutionalize a PHE focus within LVBC was rewarded during the scaling-up phase as it resulted in a formal memorandum of understanding between Pathfinder and LVBC to collaborate to strengthen LVBC’s and other stakeholder’s PHE work around the Basin. LVBC also received a grant from the USAID/East Africa Mission around this time to support the establishment of an East Africa Regional PHE Technical Working Committee. LVBC was to help create or, in the cases of Kenya and Uganda, strengthen the existing national PHE networks and working groups of the five member nations. Over the last 24 months these networks—comprised of multi-sectoral government and civil society representatives—have been meeting regularly to formulate national PHE strategies, curricula, and five-year plans and to undertake resource mobilization. In Uganda, the National Population Council (previously Population Secretariat) is playing a key role in coordinating the National Population, Health and Environment Network which is comprised of state and non-state PHE actors. The National PHE Strategic Plan 2016–2020 for Uganda is now developed and the Council has allocated a small annual budget to organize quarterly PHE coordination meetings. The substantial country and government ownership of the PHE approach that has resulted from HoPE’s efforts to strategically manage the scaling-up process is likely to serve the advancement of PHE in East Africa for many years to come. The momentum that has been created by HoPE and allied PHE activities—like the strengthened national and subnational networks and working groups—is likely to continue, but will need to be nurtured.

Given the HoPE team’s breadth of experience, they have played a critical role in supporting and advising both the Kenya and Uganda networks on key principles of operationalizing PHE. It was clear that having a real-life, home-grown East African example of PHE implementation to learn from was important for these groups. The Tanzania network was similarly helped by the presence of another Pathfinder International-led project within their borders. Given the broad representation across different line ministries, these working groups have been an excellent venue for building internal advocates for expanding institutional attention to the PHE approach within a diverse set of agencies. It was also critical that during this time LVBC began incorporating aspects of HoPE’s integrated approach into several of the projects in their portfolio, which had up to then been focused more on single-sector approaches, such as water and sanitation or environmental conservation in isolation. In an effort to assist others to successfully design, implement and scale up PHE efforts, the HoPE project team developed a HoPE toolkit (Pathfinder International 2017b) providing extensive guidance and lessons learned, which has a strong focus on monitoring and evaluation.

Meanwhile, efforts by the HoPE team to expand the number of PHE implementing organizations by supporting new NGO and community-based organization (CBO) partners to begin adopting the PHE approach had mixed results. While many saw the need and were interested in initiating or diversifying their work to address PHE, the idea that they could begin this process with minimal training and technical support, and without additional funding, turned out to be unrealistic. NGOs and CBOs normally have a mission and mandate from their funders to undertake a certain type of work, and an integrated PHE approach was either perceived as a distraction from their missions or risky insofar as the organizations were not sufficiently skilled to undertake such cross-sectoral work. This concern is reasonable when one considers that it took the HoPE team roughly a year to feel confident in their implementation of the PHE approach and they benefitted from staff with expertise in each of the population, health and environmental conservation domains.

8. Discussion

Key policy and programmatic results of the HoPE project demonstrate that applying a systematic approach to planning for scaling up from the outset and throughout pilot implementation substantially facilitated the later scaling-up process. Certain outcomes would not have been possible without the project’s strong, ongoing focus on diverse stakeholder participation and ownership-building that resulted from attention to recommendations from Beginning with the end in mind. For example, the results obtained during scale-up at the regional East Africa level, with the establishment or strengthening of PHE networks in the five member-nations, would not have happened if HoPE had not introduced the PHE concept to the Lake Victoria Basin Commission during the scoping exercise at the outset of Stage I. This focus on early, ongoing involvement of key stakeholders to promote ownership ties to recommendation 1 from Beginning with the end in mind guidance. LVBC, having now assumed the role of a regional PHE coordinator, has laid a strong foundation for the scale up of PHE efforts in East Africa. LVBC’s support to the national PHE networks has meant that especially for Uganda and Kenya, the networks are well-positioned to guide PHE scale up nationally, having learned much from HoPE along the way. At the same time, HoPE communities are and will continue to serve as resource teams who teach others about the PHE approach as well as advocating to key decision makers to help expand and institutionalize the PHE approach more widely.

Part of a systematic approach to scale up requires taking time to organize a strategic reflection and planning process when moving from pilot project to larger scale impact. For HoPE the scaling-up strategy development exercises worked well to obtain both stakeholder validation of the approach as a means to address sustainable development, as well as their recommendations for how best to proceed with scale up. The systematic inclusion of stakeholders led to a large number of champions at all levels who were aware of and supporting the idea of expanding and institutionalizing the PHE approach. The participatory process was essential in bringing the voices of important stakeholders who are often left out of such proceedings, thereby enriching the scaling-up recommendations that were made.

As a result of designing and implementing the project with scale up in mind, and the organization of a strategic planning exercise, the transition to scale up proceeded relatively smoothly. Nonetheless, as compared to other scaling-up strategy work that ExpandNet has supported for single-sector interventions, scale up of the integrated, multi-sectoral PHE approach has also presented unique challenges. Given the wide range of needs at the community level for both environmental conservation, and reproductive and other health interventions, the HoPE model contained multiple components, making it a “heavy” package compared to a simpler family planning intervention alone, for example. Even while the various sectors expressed that the integrated PHE approach was highly relevant, it was difficult to identify one sector who could take the lead and meaningfully coordinate all the others to advance scale up. In addition, even if one champion agency had emerged for coordination, funding streams tend to be highly verticalized, even within county, district and sub-county budgets. As a result, convincing health decision-makers to spend precious resources on work that also addresses environmental conservation is a “tough sell.”

Even so, the regional East African and national PHE movements now underway as a result of HoPE can play a strong role in breaking down the bureaucratic barriers to integrated development work by re-shaping the policy environment. Without HoPE the work of these national networks would be hypothetical and not as well-informed on how to operationalize PHE within their local country contexts. However, even with HoPE’s support, the individual institutions and single-sector line ministries are not immediately able to implement integrated PHE approaches without additional capacity building and hands-on technical support from HoPE or similar initiatives. This is because: (1) the majority of global health and development professionals are trained in single-sector approaches and cannot be immediately expected to implement integrated work; and (2) verticalized line ministries and bureaucracies do not have explicit mandate to address other areas of health and development outside of their purview.

At the same time, even within the HoPE project it is clear that Uganda and Kenya had very different expansion experiences and degrees of institutionalization. This may in part be explained by the composition of the implementing teams. However, probably more important was the role that the national bureaucratic, politico-administrative organization and level of resources in the relevant systems played in determining how far and how fast scale up could proceed. Whereas some may be skeptical of the emphasis placed on working with government institutions due to their transience of personnel, the HoPE project’s success came despite the devolution/decentralization of government in Kenya during the pilot stage where the Beginning with the end in mind approach encouraged engaging with government stakeholders at all levels from local, subnational, national, and regional. Working at all these levels helps ensure that work can continue even in the face of political change. For example, with Kenya’s decentralization of funding and decision-making, the Homa Bay Governor and his team were able to institutionalize the PHE Steering Committee as a county structure. Meanwhile, Uganda has had a long-standing administration where there are vastly insufficient resources at the district and lower levels to meet the development needs of the population, let alone the leeway to try new things such as integrating across sectors. Nonetheless, champions came forward at the district level in Uganda who saw in PHE a tremendous opportunity to address the needs of the populations they serve and who sought to replicate HoPE’s approach, even in the context of resource scarcity. For this reason, they opted to support the creation of demonstration village sites nearby to district headquarters.

HoPE made efforts to select and implement interventions that both fit the systems which were supposed to adopt them, and had the potential for scaling-up success should additional resources be identified. Unfortunately, it has been difficult to secure continued funding for furthering the scaling-up process (Stage III), probably in large part due to the nature of verticalized government and donor funding streams. Despite ongoing efforts to advocate for continued funding (reflected in recommendation 9 as well as resource mobilization being a key strategic choice area in the ExpandNet/WHO framework) identifying new donors to support scale up has been difficult. Although the barriers may partly be structural, earlier and more concerted efforts to mobilize funding by the HoPE project team to continue advancing Stage III might have helped.

9. Conclusions

As one looks back on the East Africa regional, national, district/county, and local/community level results that were achieved through HoPE, most would not have been seen without the team’s effort to maintain a deliberate and systematic focus on scale up all throughout. While HoPE was able to make a strong start towards PHE adoption in Kenya and Uganda, the job is far from complete and the commitment of many more stakeholders will need to be identified to ensure continued expansion and institutionalization. The same can be said for other pilot interventions: if they are to go on to achieve their intended goal of influencing larger policy and program development, then Stage III of the systematic approach to scaling up—strategically managing the scaling-up process—must receive much more explicit attention and resources from both donors and implementers. HoPE’s major commitment to the consistent use of participatory approaches, that gave strong voice and leadership to members of the community as well as to government authorities at all levels, was a key factor in the results achieved. Such approaches deserve to be widely noted and replicated in light of the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Financing for Development process, and the Paris Climate Agreement, which together offer a unique window of opportunity to move towards the application of scalable integrated approaches. After all, expansion and institutionalization of integrated development approaches may be the most promising way to more rapidly achieve the equities highlighted in these ambitious goals.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/7/1/8/s1. Document S1: HoPE-LVB Feb 2015 Kenya scaling-up strategy meeting report, and Document S2: HoPE-LVB Feb 2015 Uganda scaling-up strategy meeting report.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to appreciate multi-year support from the Office of Population and Reproductive Health, Bureau for Global Health, U.S. Agency for International Development, provided via the Evidence to Action Project cooperative agreement. Likewise, we would like to gratefully acknowledge the support from the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, who made possible the implementation of the Health of People and Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin Project in Uganda and Kenya. Much appreciation goes to the entire project team, including current Project Director Eileen Mokoya and past Project Director Lucy Shillingi; the HoPE Project communities for their dedication, and the national and international participants and stakeholders who have given their energy, commitment and support to this endeavor. Special thanks go to Ruth Simmons for support with conceptualizing and drafting the paper and to Sarah Ismail for helping it reach publication. Thanks, too, to Peter Fajans, Cara Honzak and Cheryl Margoluis for editorial contributions. Lastly, our gratitude goes to Alexis Ntabona for giving ExpandNet scaling-up related technical assistance to the HoPE team over many years. This article and the work it describes was made possible through USAID support provided under the terms of Award No. AID-OAAA-11-00024. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Author Contributions

Antony Omimo and Dorah Taranta led the implementation and scale-up of HoPE-LVB in Kenya and Uganda respectively and contributed to the paper-writing. Laura Ghiron gave ongoing scaling-up related technical support (2012–2017) and led the preparation of the manuscript. Charles Kabiswa and Samuel Mugaya guided implementation of the environmental conservation-focused work from the local to the national level in Uganda. Sono Aibe helped conceptualize the HoPE project and provided strategic inputs throughout with particular focus on advocacy and scale up. Millicent Kodande (Kenya) and Caroline Nalwoga (Uganda) provided leadership on HoPE’s monitoring and evaluation activities and implementation more generally, while Pamela Onduso provided critical inputs on Kenya national and East Africa regional-level advocacy and supported information-sharing. All authors reviewed the manuscript for accuracy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aichatou, Barry, Cheikh Seck, Thierno Souleymane Baal Anne, Gabrielle Clémentine Deguenovo, Alexis Ntabona, and Ruth Simmons. 2016. Strengthening Government Leadership in Family Planning Programming in Senegal: From Proof of Concept to Proof of Implementation in 2 Districts. Global Health Science and Practice 4: 568–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, Larry, and Rajani R. Ved. 2012. Scaling Up—From Vision to Large-Scale Change A Management Framework for Practitioners, 2nd ed. Washington: Management Systems International (MSI). [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, Roger-Mark. 2008. Scaling up Integrated Population, Health and Environment Approaches in the Philippines: A Review of Early Experiences. Washington: World Wildlife Fund and the Population Reference Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- ExpandNet and World Health Organization. 2009. Practical Guidance for Scaling Up Health Service Innovations. Geneva: World Health Organization, Available online: http://www.expandnet.net/tools.htm (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- ExpandNet and World Health Organization. 2010. Nine Steps for Developing a Scaling-Up Strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization, Available online: http://www.expandnet.net/tools.htm (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- ExpandNet and World Health Organization. 2011. Beginning with the End in Mind: Planning Pilot Projects and Other Programmatic Research for Successful Scaling up. Geneva: World Health Organization, Available online: http://www.expandnet.net/tools.htm (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Gaffikin, Lynne. 2008. Scaling Up Population and Environment Approaches in Madagascar: A Case Study. Washington: World Wildlife Fund and Evaluation and Research Technologies for Health (EARTH) Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiron, Laura, Lucy Shillingi, Charles Kabiswa, Godfrey Ogonda, Antony Omimo, Alexis Ntabona, Ruth Simmons, and Peter Fajans. 2014. Beginning with sustainable scale up in mind: Initial results from a population, health and environment project in East Africa. Reproductive Health Matters 22: 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyonzo, Nelson, Paul Nyachae, Peter Kagwe, Margaret Kilonzo, Feddis Mumba, Kenneth Owino, George Kichamu, Bartilol Kigen, Peter Fajans, Laura Ghiron, and et al. 2015. From Project to Program: Tupange’s Experience with Scaling Up Family Planning Interventions in Urban Kenya. Reproductive Health Matters 23: 103–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linn, Johannes F. 2011. It’s time to scale up success in development assistance. KfW-Development Research 7: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pathfinder International. 2015. Sustaining Health, Rights, and the Environment in the Lake Victoria Basin. Watertown: Pathfinder International. [Google Scholar]

- Pathfinder International. 2017a. HoPE-LVB Advocacy Brief: Scaling up Family Planning in East Africa through Population, Health and Environment Advocacy. Watertown: Pathfinder International, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pathfinder International. 2017b. HoPE LVB Toolkit. Available online: http://www.pathfinder.org/publications/hope-lvb-toolkit/ (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Perlman Robinson, Jenny, Rebecca Winthrop, and Eileen McGivney. 2016. Millions Learning: Scaling up Quality Education in Developing Countries. Washington: The Brookings Institution Center for Universal Education. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Everett. 1995. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Ruth, Peter Fajans, and Laura Ghiron. 2007. Scaling up Health Service Delivery: from Pilot Innovations to Policies and Programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Ruth, Peter Fajans, Laura Ghiron, and Brooke Ronald Johnson. 2011. Managing Scaling Up. In From One to Many: Scaling up Health Programs in Low Income Countries. Edited by Richard A. Cash, A. Mushtaque R. Chowdhury, George B. Smith and Faruque Ahmed. Bangladesh: The University Press Limited, chp. 1. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2015. Paris Agreement. Available online: http://unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php (accessed on 15 October 2017).

- United Nations. 2016. Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 15 October 2017).

- World Health Organization. 2007. Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yavinsky, Rachel Winnik, Carolyn Lamere, Kristen P. Patterson, and Jason Bremner. 2015. The Impact of Population, Health, and Environment Projects: A Synthesis of the Evidence. Washington: Population Council, The Evidence Project. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Given the paper’s focus on the systematic scaling-up approach, it provides only an overview of the HoPE initiative. Further details are available elsewhere (Pathfinder International 2015). |

| 2 | The ExpandNet/WHO scaling-up framework is discussed in greater depth in ExpandNet/WHO tools. |

| 3 | The term innovation is used as in the literature on the diffusion of innovations to imply something that is new in the setting where it is to be implemented and not necessarily a completely new approach. |

| 4 | The term pilot project is used in this paper as a shorthand to also encompass a diversity of field tests including experimental designs, implementation research, tests of policy changes, proof of concept studies, demonstration projects and other operations research efforts. |

| 5 | South Sudan became the sixth member state of the East African Community in April, 2016. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).