Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case Studies of Sex Workers in Argentina and Ecuador

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“We don’t have a place to work.”—Río, a Buenos Aires sex worker

“All we want is for them to give us a space, nothing more.”—Rosa, a Quito sex worker

2. Background: Sex Work and Space

2.1. Geographies of Sex Work

Sex workers and the law’s constant response to one another creates the spaces of sex work, which move and change over time as a result of this negotiation [35,36].“as the outcome of an ongoing relationship between the ordering enacted by the state, law and citizenry…and the negotiation of this ordering enacted by those who make their living in the red-light district. This identifies the red-light district as always becoming, a complex assemblage made and remade through the folding together of these different types of space.”.([21], p. 80, emphasis in original)

2.2. Spaces’ Influence on Sex Workers’ Conditions

3. Methods

3.1. Argentina

3.2. Ecuador

4. Case Study: Argentina

4.1. Background

4.1.1. Regulation of Sex Work

4.1.2. Sex Worker Organization

4.2. Sex Workers’ Use and Experience of Space

4.2.1. Brothels

4.2.2. Bars

4.2.3. Cafés13

4.2.4. Street Work

Boliches had registers of who entered, and in the café, her friends look out for her. “But in the street, no one is going to take care of me,” she said. “It’s very hard. You have to be very brave to work in the street,” said Clarisa. Street sex workers sometimes experience violence or robbery from homeless drug users or drunks. Estela, who works outside Montecarlo, explained she acts nice to the street youth so that when they’re drugged on paco, cocaine paste, they don’t attack and rob her.“It bothers me when they go to a boliche, where high quality people go…and [the authorities] make a fuss there because…it’s not being in the street…like a typical prostitute left in the street picking up guys in their car. By contrast I worked in a boliche, they closed it, I had to go to the corners, the street, that is, walk, and if a car stopped me I stopped, I got in.”

5. Case study: Ecuador

5.1. Background

5.1.1. Regulation of Sex Work

5.1.2. Sex Worker Organization

5.2. Sex Workers’ Use and Experience of Space

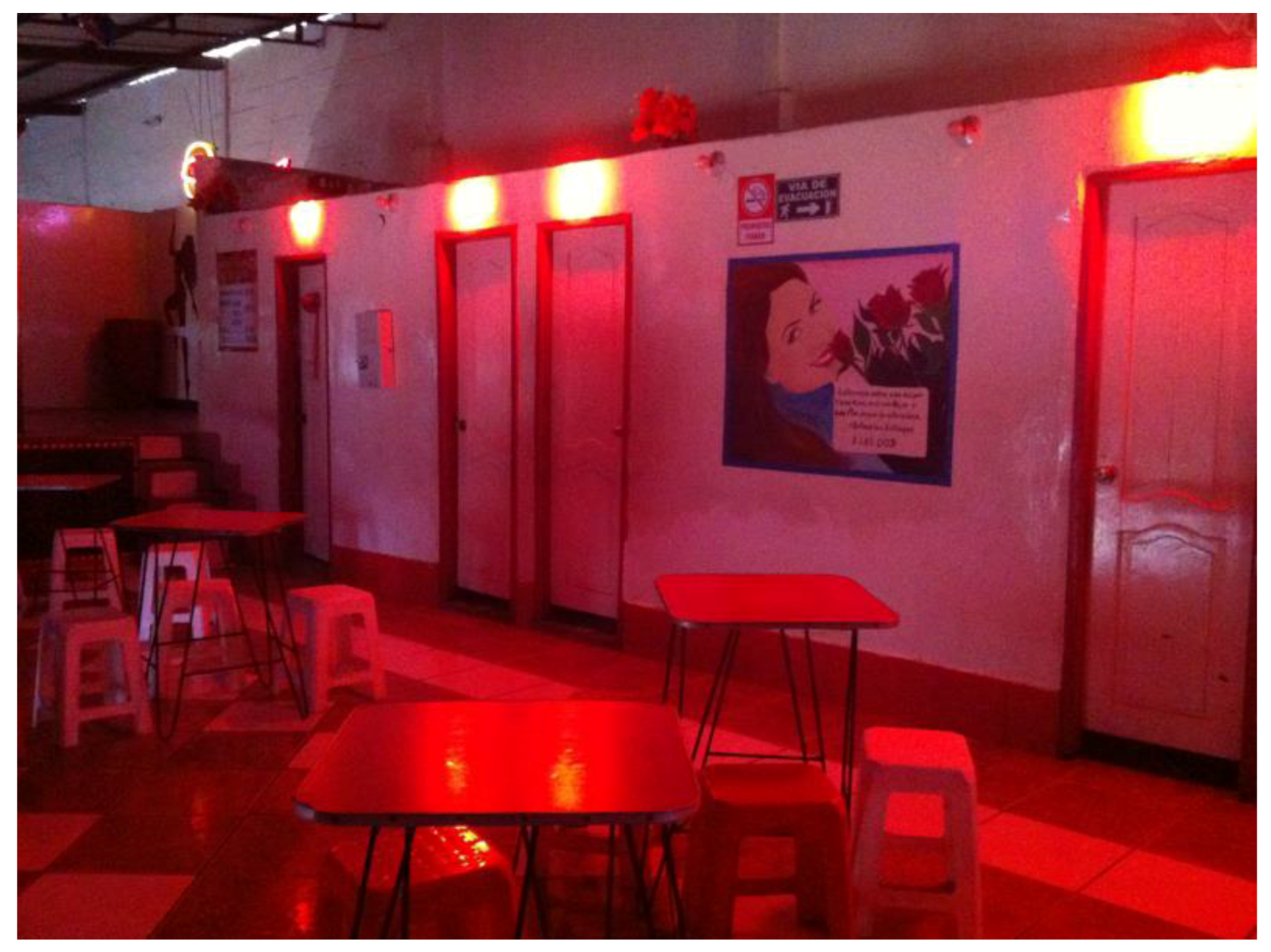

5.2.1. Brothels

5.2.2. Street Work

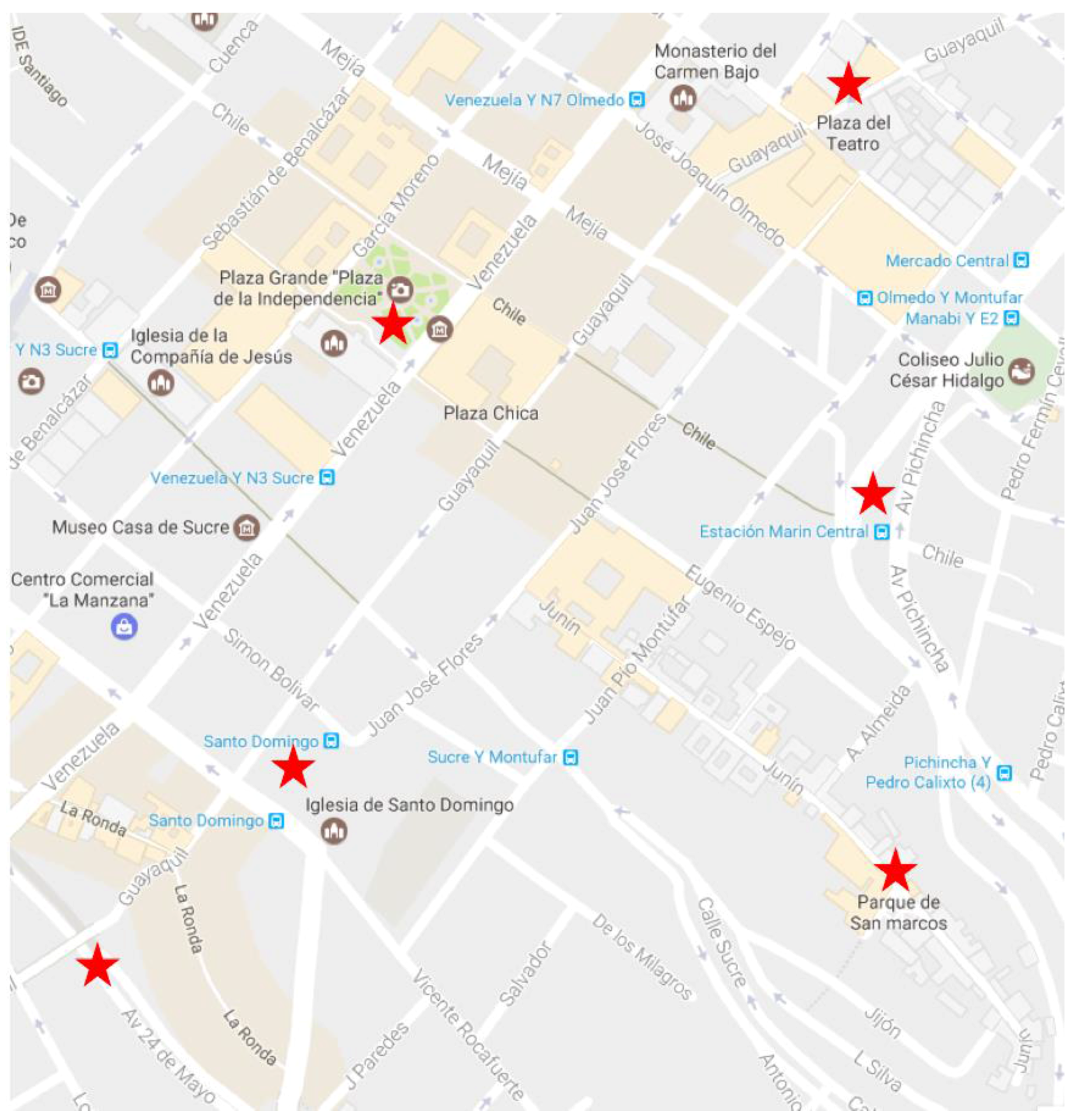

Conflict over Space in the Historic Center of Quito

6. Discussion

6.1. The Importance of Space

6.2. Ideological Influences on State Control of Prostitution Spaces

The state’s efforts to remove sex workers from public outdoor space into a designated indoor space reflect an attempt to make sex work less visible, but not to eliminate it, supporting Hubbard and Sanders’ claim that “the intention [of the state] has never been to completely destroy prostitution, rather, to enact a mechanism of regulation that serves to enclose it” ([21], p. 82).“Here not only is the surface of the city—the facade of postcard-perfect colonial Quito—at stake, but so is the substance: the notion of the city being argued for. The debate about the regulation of street sex work is a debate on what presences are allowed and even celebrated in public space, and what others are discouraged, are “ordered” rigorously, or point-blank hidden.”[82]

6.3. Sex Worker Resistance

6.4. How Should States Address Sex Work Space?

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Pseudonym | Neighborhood Where Was Working | Space of Solicitation | Gender | Age Range 1 | Country of Origen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanca | microcentro | café | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Clara | microcentro | café | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Clarisa | microcentro | café | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Juliana | microcentro | café | F | 38–60 | Brazil |

| Luna | microcentro | café | F | 38–60 | Paraguay |

| Mónica | microcentro | café | F | 27–33 | Paraguay |

| Rio | microcentro | café | F | 38–60 | unknown |

| Abril | microcentro | street | F | 20–26 | Argentina |

| Barbie | microcentro | street | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Catarina | microcentro | street | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Magali | microcentro | street | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Olivia | microcentro | street | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Sandra | microcentro | street | F | 34–37 | Uruguay |

| Yesenia | microcentro | street | F | 27–33 | Dominican Republic |

| Jessica | microcentro | street | T | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Fernanda | microcentro | street outside café | F | 38–60 | Brazil |

| Lucila | microcentro | street outside café | F | 20–26 | Peru |

| Maribel | microcentro | street outside café | F | 20–26 | Argentina |

| Marina | microcentro | street outside café | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Pilar | microcentro | street outside café | F | 20–26 | Argentina |

| Rocío | microcentro | street outside café | F | 34–37 | unknown |

| Sabrina | microcentro | street outside café | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Valentina | microcentro | street outside café | F | unknown | unknown |

| Vanesa | microcentro | street outside café | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Estela | microcentro | street outside café | T | 36–60 | Argentina |

| Gonzalo | mostly Recoleta and Palermo | bars/nightclubs and street | M | unknown | Argentina |

| Alma | Once | street/public transport station | F | 38–60 | Paraguay |

| Andrea | Once | street/public transport station | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Nia | Once | street/public transport station | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Rafaela | Once | street/public transport station | F | 20–26 | Argentina |

| Violeta | Once | street/public transport station | F | 34–37 | Argentina |

| Viviana | Once | street/public transport station | F | 34–37 | Argentina |

| Alfonsín | Once | street/public transport station | M | 34–37 | Argentina |

| Felipe | Once | street/public transport station | M | 20–26 | Argentina |

| Roberto | Once | street/public transport station | M | 34–37 | Uruguay |

| Belén | Once | street/public transport station | T | 20–26 | Paraguay |

| Casandra | Recoleta | bar | F | 38–60 | Argentina |

| Talia | Recoleta | bar | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Gisel | Recoleta | street | F | 27–33 | Argentina |

| Kelsi | Recoleta | street | F | 27–33 | Dominican Republic |

| Patricia | Recoleta | street | F | 34–37 | Argentina |

| Name | Organization | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Margarita Peralta | AMADH | Board of Directors |

| Argentina Ascona | AMADH | Spokesperson |

| Silvia Mónica | AMADH | Treasurer |

| Georgina Orellano | AMMAR | President |

| María Esther López | AMMAR Neuquén | Representative |

| Norma Beatriz Torres | AMMAR Entre Rios | Representative |

| Fátima Olivares | AMMAR Mendoza | Representative |

| Mónica Lencina | AMMAR San Juan | Representative |

| María Lencina | AMMAR San Juan | Representative |

| Mariana Alejandra Contreras | AMMAR Santiago | Representative |

| Elena Reynaga | RedTraSex | General Secretary |

| Name | Institution | Position at Time of Interview | Year of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viviana Caminos (roundtable discussion in 2016 also included Maria Rios, Edgardo Calandra, Ricardo Prieto, Vanesa Morio, and Vivian Ravich) | Stop Trafficking Network (RATT) | President | 2015, 2016 |

| Luján Araujo | Foundation María de los Angeles | Press and Communications Director | 2015, 2016 |

| Carla Majdalani | Civil Association The Meeting House (La Casa del Encuentro) | Coordinator of Institutional Development | 2015 |

| Monique Altschul | Foundation Women in Equality | Co-founder and Executive Director | 2015 |

| Marcela Rodríguez | Counseling and Sponsorship Program for Victims of the Crime of Trafficking in Persons (Programa de Asesoramiento y Patrocinio para las Víctimas del Delito de Trata de Personas) | Head | 2015 |

| Ana Bettina Casadei | Congress of the Nation of Argentina; General Labor Confederation; | Lawyer | 2015 |

| Cristian Encinas | Program of Rescue and Assistance of Victims of Trafficking | Legal Services Coordinator | 2015 |

| Marcelo Colombo | Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons | Head | 2015 |

| Victoria Sassola | Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons | Subsecretary | 2015 |

| Agustina D’Angelo | Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons | Chief Dispatcher | 2015 |

| Octavia Botalla | Prosecutor’s Office for the Combatting of Trafficking and Exploitation of Persons | Official | 2015 |

| Aníbal Fernández | Cabinet of Ministers of Argentina | Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers | 2015 |

| Cecilia Varela | National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET) | Researcher | 2015 |

| Pseudonym | City Where Worked | Space of Solicitation | Gender | Age Range i | Country of Origen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ana | Guayaquil | brothel | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Ariana | Guayaquil | brothel | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Ava | Guayaquil | brothel | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Daniel | Guayaquil | social media | M | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Elena | Guayaquil | street | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Lourdes Toscano * | Guayaquil | street | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Rosalinda | Guayaquil | street | T | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Fiona | Machala | brothel | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Juanita | Machala | brothel | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Mari | Machala | brothel | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Ronda | Machala | brothel | F | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Cristina | Machala | street | T | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Lucero | Machala | street | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Soraya | Machala | street | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Adolfo | Machala | street/park | M | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Bryan | Machala | street/park | M | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Marco Luis | Machala | street/park | M | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Miguel | Machala | street/park | M | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Tomás | Machala | street/park | M | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Renata | Milagro | street | F | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Belicia | Quito | brothel | F | 28–34 | Colombia |

| Gabriela | Quito | brothel | F | 44–59 | Colombia |

| Isabela | Quito | brothel | F | 28–34 | Colombia |

| Samantha | Quito | brothel | F | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Susana | Quito | brothel | F | 35–43 | Colombia |

| Barbara Reyes ** | Quito | internet/social media | T | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Alexandra | Quito | street—Amazonas | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Angela | Quito | street—Amazonas | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Britney | Quito | street—Amazonas | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Claudia | Quito | street—Amazonas | F | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Ana Lucia | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Aurelia | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Colombia |

| Belinda | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 28–34 | Spain |

| Cecilia | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Concepción | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Erika | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Josefina | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Luz | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| María Carmen | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Colombia |

| Rosa | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Sandra | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 44–59 | Ecuador |

| Teresa | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | F | 18–27 | Colombia |

| Ana Carolina Alvarado * | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Dominica | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Donna | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Lohana | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 28–34 | Ecuador |

| Maria | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 35–43 | Ecuador |

| Suri | Quito | street—Plaza del Teatro | T | 18–27 | Ecuador |

| Name | Organization | Position | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jovita Valencia | Association of Autonomous Female Workers “1st of August” | President | Guayaquil |

| Elizabeth Colobón | Association of Female Sex Workers “1st of May;” Association of Female Sex Workers “For a Better Future” | President; Vice President | Quito |

| Virmania Montaño | Association of Autonomous Women “22nd of June” | Secretaria Jurídica | Machala |

| Brígida Reyes | Association of Autonomous Women “22nd of June” | President | Machala |

| Carolina Alvarado * | Aso TST UIO | President | Quito |

| Lourdes Torres | ASOPRODEMU | President | Guayaquil |

| Margarita | Flor de Azalea | Vice President | Machala |

| Lourdes Herrero Franco | Mujeres del Cantón Milagro | President | Milagro |

| Karina Bravo | PLAPERTS; Association of Women Sex Workers “Collective Flor de Azalea” | President; President | Machala |

| Alexandra Flores | Association of Women Sex Workers “For a Better Future” | President | Quito |

| Lourdes Toscano * | RedTrabSex Guayaquil | President | Guayaquil |

| Name | Organization | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Angel Rivas | Agrupación GLBT Sembrando Futuro | Vice President |

| Rosa Manzo | Fundación Quimera | President |

| Elizabeth Vásquez | Proyecto Transgénero | Founder, Legal Coordinator |

| Ana Almeida | La Marcha de las Putas; Proyecto Transgénero | President; Executive Director |

| Amira Herdoíza | Corporación Kimirina | Executive Director |

| Yvets Morales | Corporación Kimirina | Consultant |

| Juan León | Ecuadorian Center for the Promotion and Action of Women (CEPAM) | Researcher, psychologist |

| Name | Government Office | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Joseph Mejía | Secretariat of Social Inclusion, Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito | Coordinator of Human Mobility and Sexual and Gender Diversity |

| Sara González | Secretariat of Social Inclusion, Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito | Responsible for the Area of Sex Work for Promotion of Rights |

| Dayana Morán | Secretariat of Security, Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito | Director of Governance |

| Nelly Sánchez | Commission of Constructions, Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito | Curator of the Central Zone |

| anonymous | Zonal Tourism Administration of the Mariscal, Municipality of the Metropolitan District of Quito | anonymous |

| Name | Business or Institution | Occuptation | City |

|---|---|---|---|

| David | Habana Club brothel | manager at Habana Club brothel | Quito |

| Elizabeth Martinez | Akershuz brothel | owner of Akershuz brothel | Quito |

| Ivonne Alexandra Cruz Figueroa | Health Center Mabel Estupiñán | doctor | Machala |

| Jim | spa | owner | Machala |

| unknown | video cinema | owner | Machala |

Appendix B

| Street | Brothel | Business at Which Sex Worker Is Employee | Business at Which Sex Worker Is Customer | Private Premise Owned or Rented by Sex Worker | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security | Material protections ii | Low | Moderate to high, depends on brothel | Moderate to high | Moderate to high | Low to moderate |

| Ability to screen clients | Low | Moderate | High | High | High | |

| Proximity of people who can help in case of emergency | Depends on location and if works alone or in a group | High | High | High | Low, unless shared with others | |

| Agency | Ability to set own schedule | High | Low to moderate | Low to moderate | High | Very high |

| Ability to choose clients | High | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | High | Very high | |

| Ability to choose how to dress | High | Low | Low | Moderate to high | Very high | |

| Ability to avoid consuming alcohol | High | Moderate, depends on brothel | Low | Moderate in bar or club, high in café | High | |

| Earnings | Price charged | Low, depends on location | Moderate, depends on brothel | High | High | High |

| Number of clients | Depends on location & time | Depends on location & time | Depends on location & time | Depends on location & time | Depends on location & time | |

| Percent of earnings kept for self | High | Low | High | Moderate to high (may need to pay cover charge or make purchase) | High, but premise may be costly | |

| Other | Privacy from public | Low | High | Moderate | Moderate | Very high |

| Physical comfort iii | Low | Moderate, depends on brothel | High | High | Very high |

References

- Javier Ortega. “Protesta Extrema De Las Trabajadoras Sexuales En Quito.” El Comercio. 2015. Available online: http://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/protesta-extrema-trabajadorassexuales-quito.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- El Mercioco. “La Protesta De Las Trabajadoras Sexuales En Quito No Tiene Límites.” Available online: http://elmercioco.com/video-la-protesta-de-las-trabajadoras-sexuales-en-quito-no-tiene-limites/ (accessed on 9 December 2016).

- AMMAR. “Acá No Hay Víctimas De Trata, Acá Hay Mujeres Libres.” 2016. Available online: http://www.ammar.org.ar/Aca-no-hay-victimas-de-Trata-aca.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Gillian M. Abel, and Lisa J. Fitzgerald. “‘The Street’s Got Its Advantages’: Movement between Sectors of the Sex Industry in a Decriminalised Environment.” Health, Risk & Society 14 (2012): 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Esohe Aghatise. “Trafficking for Prostitution in Italy: Possible Effects of Government Proposals for Legalization of Brothels.” Violence Against Women 10 (2004): 1126–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheila Jeffreys. The Idea of Prostitution. Melbourne: Spinifex, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Donna M. Hughes. “Women’s Wrongs.” National Review. 2004. Available online: http://www.nationalreview.com/article/212601/womens-wrongs-donna-m-hughes (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Monica O’Conner, and Grainne Healy. The Links between Prostitution and Sex Trafficking: A Briefing Handbook. New York: Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW). Brussels: European Women’s Lobby (EWL), 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald Weitzer. “The Mythology of Prostitution: Advocacy Research and Public Policy.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 7 (2010): 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kamala Kempadoo. “Globalizing Sex Workers’ Rights.” Canadian Woman Studies 22 (2003): 143–50. [Google Scholar]

- Carol Leigh. “Inventing Sex Work.” In Whores and Other Feminists. Edited by Jill Nagle. New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 225–31. [Google Scholar]

- Martha C. Nussbaum. “Whether from Reason or Prejudice: Taking Money for Bodily Services.” Journal of Legal Studies 27 (1998): 693–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carol Queen. “Sex Radical Politics, Sex-Positive Feminist Thought, and Whore Stigma.” In Whores and Other Feminists. Edited by Jill Nagle. New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 125–35. [Google Scholar]

- Frankie Mullin. “The Difference between Decriminalisation and Legalisation of Sex Work.” New Statesman. 2015. Available online: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/feminism/2015/10/difference-between-decriminalisation-and-legalisation-sex-work (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Ronald Weitzer. “Sociology of Sex Work.” The Annual Review of Sociology 35 (2009): 213–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason Prior, and Penny Crofts. “Is Your House a Brothel? Prostitution Policy, Provision of Sex Services from Home, and the Maintenance of Respectable Domesticity.” Social Policy & Society 14 (2015): 125–34. [Google Scholar]

- Phil Hubbard, and Jason Prior. “Out of Sight, out of Mind? Prostitution Policy and the Health, Well-Being and Safety of Home-Based Sex Workers.” Critical Social Policy 33 (2012): 140–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason Prior, Phil Hubbard, and Philip Birch. “Sex Worker Victimization, Modes of Working, and Location in New South Wales, Australia: A Geography of Victimization.” Journal of Sex Research 40 (2013): 574–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angie Hart. “(Re)Constructing a Spanish Red-Light District: Prostitution, Space and Power.” In Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities. Edited by David Bell and Gill Valentine. London: Routledge, 1995, pp. 214–28. [Google Scholar]

- Phil Hubbard. “Red-Light Districts and Toleration Zones: Geographies of Female Street Prostitution in England and Wales.” Area 29 (1997): 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phil Hubbard, and Teela Sanders. “Making Space for Sex Work: Female Street Prostitution and the Production of Urban Space.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (2003): 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathy McIlwaine. “The Negotiation of Space among Sex Workers in Cebu City, the Philippines.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 17 (2006): 150–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard Symanski. Immoral Landscape: Female Prostitution in Western Societies. Toronto: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jason Prior, and Andrew Gorman-Murray. “Housing Sex within the City: The Placement of Sex Services Beyond Respectable Domesticity? ” In (Sub)Urban Sexscapes. Edited by Paul Maginn and Christine Steinmetz. Abingdon: Routledge, 2015, p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Marc Askew. “City of Women, City of Foreign Men: Working Spaces and Re-Working Identities among Female Sex Workers in Bangkok’s Tourist Zone.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 19 (1998): 130–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence Knopp. “Sexuality and Urban Space: A Framework for Analysis.” In Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities. Edited by David Bell and Gill Valentine. London: Routledge, 1995, pp. 149–61. [Google Scholar]

- Henri Lefebvre. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- David Bell, and Gill Valentine. “Introduction: Orientations.” In Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities. Edited by David Bell and Gill Valentine. London: Routledge, 1995, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Petra L. Doan. “Regulating Adult Business to Make Spaces Safe for Heterosexual Families in Atlanta.” In (Sub)Urban Sexscapes: Geographies and Regulation of the Sex Industry. Edited by Paul Maginn and Christine Steinmetz. Abingdon: Routledge, 2015, p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- David Bell, and Gill Valentine, eds. Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Paul Maginn, and Christine Steinmetz, eds. (Sub)Urban Sexscapes: Geographies and Regulation of the Sex Industry. Abingdon: Routledge, 2015.

- Petra L. Doan, ed. Queerying Planning: Challenging Heteronormative Assumptions and Reframing Planning Practice. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011.

- Jason Prior, Penny Crofts, and Phil Hubbard. “Planning, Law, and Sexuality: Hiding Immorality in Plain View.” Geographical Research 51 (2013): 354–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anna Wilking. “Sex Workers Outsmart Quito Police: Without Clear Legislation Governing Street Prostitution in Ecuador, Sex Workers Band Together to Battle Frequent and Arbitrary Police Crackdowns—And Win.” NACLA Report on the Americas 47 (2014): 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason Prior, and Phil Hubbard. “Time, Space and the Authorisation of Sex Premises in London and Sydney.” Urban Studies 54 (2017): 633–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason Prior. “Planning for Sex in the City: Urban Governance, Planning and the Placement of Sex Industry Premises in Inner Sydney.” Australian Geographer 39 (2008): 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariangeles Palacios. “Patrulla Legal: El Derecho En La Calle.” 60 min: Namaste, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sharvari Karandikar, and Moisés Próspero. “From Client to Pimp: Male Violence against Female Sex Workers.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 25 (2009): 257–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celia Williamson, and Terry Cluse-Tolar. “Pimp-Controlled Prostitution: Still an Integral Part of Street Life.” Violence Against Women 8 (2002): 1074–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny Crofts. “Brothels: Outlaws or Citizens? ” International Journal of Law 6 (2010): 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra Álvarez, and Mariana Sandoval. El Trabajo Sexual En El Centro Histórico De Quito. Edited by Esteban Crespo. Quito: DMQ, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Phil Hubbard, Spike Boydell, Penny Crofts, Jason Prior, and Glen Searle. “Noxious Neighbors? Interrogating the Impacts of Sex Premises in Residential Areas.” Environment and Planning A 45 (2013): 126–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara G. Brents, and Kathryn Hausbeck. “Violence and Legalized Brothel Prostitution in Nevada: Examining Safety, Risk, and Prostitution Policy.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20 (2005): 270–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamara O’Doherty. “Victimization in Off-Street Sex Industry Work.” Violence Against Women 17 (2011): 944–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathleen Ragsdale, Jessica T. Anders, and Effie Philippkos. “Migrant Latinas and Brothel Sex Work in Belize: Sexual Agency and Sexual Risk.” Journal of Cultural Diversity 14 (2007): 26–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daria Snadowsky. “The Best Little Whorehouse Is Not in Texas: How Nevada’s Prostitution Laws Serve Public Policy, and How Those Laws May Be Improved.” Nevada Law Journal 6 (2005): 217–47. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara G. Brents, and Kathryn Hausbeck. “What Is Wrong with Prostitution? Assessing Exploitation in Legal Brothels.” In Paper presented at the American Sociological Association Annual Meetings, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–14 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- David Brady, Monica Biradavolu, and Kim M. Blankenship. “Brokers and the Earnings of Female Sex Workers in India.” American Sociological Review 80 (2015): 1123–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maureen Norton-Hawk. “A Comparison of Pimp- and Non-Pimp-Controlled Women.” Violence Against Women 10 (2004): 189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominique Eve Roe-Sepowitz, James Gallagher, Markus Risinger, and Kristine Hickle. “The Sexual Exploitation of Girls in the United States: The Role of Female Pimps.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 30 (2015): 2814–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendy Chapkis. Live Sex Acts: Women Performing Erotic Labor. New York: Routledge, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mary Sullivan, and Sheila Jeffreys. Legalising Prostitution Is Not the Answer: The Example of Victoria, Australia. North Amherst: Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Toorjo Ghose, Dallas T. Swendeman, and Sheba M. George. “The Role of Brothels in Reducing Hiv Risk in Sonagachi, India.” Qualitative Health Research 21 (2011): 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean-Louis Guereña. “El Burdel Como Espacio De Sociabilidad.” Hispania 63 (2003): 551–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny Crofts, Jane Maree Maher, Sharon Pickering, and Jason Prior. “Ambivalent Regulation: The Sexual Services Industries in Nsw and Victoria—Sex Work as Work, or as a Special Category.” Current Issues in Criminal Justice 23 (2012): 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Penny Crofts. “Brothels and Disorderly Acts.” Public Space: The Journal of Law and Social Justice 1 (2007): 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Judith G. Kelley. Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, Available online: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B06XTTTD6R/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1 (accessed on 15 April 2017).

- Amnesty International. “Amnesty International Policy on State Obligations to Respect, Protect and Fulfil the Human Rights of Sex Workers.” Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol30/4062/2016/en/ (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Cheryl Overs. “Sex Workers: Part of the Solution: An Analysis of Hiv Prevention Programming to Prevent Hiv Transmission During Commercial Sex in Developing Countries.” Popline, 2002, unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Argentine federal Senate and Chamber of Deputies. “LEY 12331—PROFILAXIS.” 1937. Available online: http://www.comisionporlamemoria.org/normativa/genero/Ley%20N%C2%B0%2012.331%20Profilaxis%20de%20Enfermedades%20Ven%C3%A9reas%20y%20Examen%20prenupcial%20obligatorio.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2017).

- Donna J. Guy. Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires: Prostitution, Family, and Nation in Argentina. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. "What I’m Doing Is Not a Crime": The Human Cost of Criminalizing Sex Work in the City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. London: Amnesty International, 2016, p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- AMMAR. Criminalización Del Trabajo Sexual En Los Códigos Contravencionales Y De Falta De Argentina. Buenos Aires: AMMAR, 2016, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Development Studies. “Map of Sex Work Law.” Available online: http://spl.ids.ac.uk/sexworklaw (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Kate Hardy. “Incorporating Sex Workers into the Argentine Labor Movement.” International Labor and Working-Class History 77 (2010): 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramiro Barreiro. “Buenos Aires Prohíbe Cualquier Tipo De Prostíbulo.” El País. 2016. Available online: http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2016/09/30/argentina/1475271044_315470.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- La Política. “Prostitutas Le Hicieron Un ‘Bombachazo’ a Vera En La Puerta De La Legislatura.” La Política Online. 2014. Available online: http://www.lapoliticaonline.com/nota/79159/ (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Redacción A24. “La Asociación De Meretrices Escrachó a Gustavo Vera.” Adelanto 24. 2015. Available online: http://adelanto24.com/2015/08/07/la-asociacion-de-meretrices-escracho-a-gustavo-vera/ (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Nora Sánchez. “Cerrarán Las Whiskerías Y No Podrá Haber Coperas En Los Boliches.” Clarín. 2016. Available online: http://www.clarin.com/ciudades/Cerraran-whiskerias-podra-coperas-boliches_0_1654634583.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Castillo Muñoz, and María Augusta. “Tutela Jurídica Para Las Y Los Trabajadores Sexuales En Ecuador. Propuesta De Elementos Jurídicos Que Debe Contener Un Proyecto De Ley.” Bachelor Thesis, Abogada de los Tribunales y Juzgados de la República, Universidad de las Américas, Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador. Acuerdo Ministerial No. 1784; Edited by Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador. Quito: Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador, 2010, p. 64.

- Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador. Acuerdo Ministerial No. 5910; Edited by Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador. Quito: Ministerio del Interior del Gobierno Nacional de la República del Ecuador, 2015, p. 20.

- “Asociacion de Trabajadora Autónomas"22 de Junio" de El ORO en Fundación Quimera.” In Trabajadoras Del Sexo, Memorias Vivas. Machala: Mamacash, 2002.

- EL UNIVERSO. “Reunión Con Trabajadoras Sexuales.” EL UNIVERSO. 2009. Available online: http://www.eluniverso.com/2009/10/14/1/1355/reunion-trabajadoras-sexuales.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Betty Beltrán. “El Danubio Azul Sobrevive En La Cantera, Zona De Tolerancia Del Centro De Quito.” El Comercio. 2016. Available online: http://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/lacantera-danubioazul-prostitucion-trabajadorassexuales-barrios.html (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Mariuxi Lituma, Susana Morán, and Alejandra Yépez. “El Olvido De Las Mujeres En La Cantera.” El Comercio. 2012. Available online: http://especiales.elcomercio.com/2012/07/prostitucion/4.php (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Lacallendisputa Quito. “Trabajadoras Sexuales De Quito: Derecho a La Calle.” YouTube, 2016, Video file. [Google Scholar]

- El Consejo Metropolitano de Quito. Ordenanza Metropolitana No. 0280. Quito: El Consejo Metropolitano de Quito, 2012, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Nikki Jeal, and Chris Salisbury. “Health Needs and Service Use of Parlour-Based Prostitutes Compared with Street-Based Prostitutes: A Cross-Sectional Survey.” An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 114 (2007): 875–81. [Google Scholar]

- Penny Crofts, and Jason Prior. “Home Occupation or Brothel? Selling Sex from Home in New South Wales.” Urban Policy and Research 30 (2012): 127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason Prior, Spike Boydell, and Phil Hubbard. “Nocturnal Rights to the City: Property, Propriety and Sex Premises in Inner Sydney.” Urban Studies 49 (2012): 1837–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Calle en DisPuta. “El Concepto De La Ciudad: Para Un Quito Inclusivo.” 2016. Available online: https://lacallendisputa.wordpress.com/2016/07/18/el-concepto-de-la-ciudad-para-un-quito-inclusivo/ (accessed on 18 April 2017).

- Cristian Encinas, and Programa Nacional de Rescate y Acompañamiento a las Personas Damnificadas por el Delito de Trata, Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Interview, 2015.

- Victoria Sassola, Agustina D’, Octavia Botalla, and Procuraduría para el Combate de la Trata y Explotación de Personas, Ministerio Público Fiscal, Procuración General de la Nación, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Interview, 2015.

- Viviana Caminos, and Red Alto a la Trata y el Tráfico (RATT), Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Interview, 2015.

- Monique Altschul, and Fundación Mujeres en Igualdad, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. Interview, 2015.

- Cecilia Varela. “Del Tráfico De Las Mujeres Al Tráfico De Las Políticas. Apuntes Para Una Historia Del Movimiento Anti-Trata En La Argentina (1998–2008).” Publicar en Antropología y Ciencias Sociales 10 (2012): 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cecilia Varela. “La Campaña Anti-Trata En La Argentina Y La Agenda Supranacional.” In Género Y Violencia En El Mercado Del Sexo: Política, Policía Y Prostitución. Edited by Deborah Daich and Mariana Sirimarco. Biblos: Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Janet Halley, Prabha Kotsiswaran, Hila Shamir, and Chantal Thomas. “From the International to the Local in Feminist Legal Responses to Rape, Prostitution/Sex Work, and Sex Trafficking: Four Studies in Contemporary Governance Feminism.” Harvard Journal of Law & Gender 29 (2006): 335–423. [Google Scholar]

- Gillian M. Abel, Lisa J. Fitzgerald, and Cheryl Brunton. The Impact of the Prostitution Reform Act on the Health and Safety of Sex Workers. Christchurch: Department of Public Health and General Practice, University of Otago, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara Sullivan. “When (Some) Prostitution Is Legal: The Impact of Law Reform on Sex Work in Australia.” Journal of Law and Society 37 (2010): 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine Harcourt, Jody O’Connor, Sandra Egger, Christopher K. Fairley, Handan Wand, Marcus Y. Chen, Lewis Marshall, John M. Kaldor, and Basil Donovan. “The Decriminalisation of Prostitution Is Associated with Better Coverage of Health Promotion Programs for Sex Workers.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 34 (2010): 482–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Goodyear, and Ronald Weitzer. “International Trends in the Control of Sexual Services.” In Policing Pleasure: Sex Work, Policy, and the State in Global Perspective. Edited by Susan Dewey and Patty Kelly. New York: New York University Press, 2011, pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tiantian Zheng. “Sex Work and the State in Contemporary China.” In Policing Pleasure: Sex Work, Policy, and the State in Global Perspective. Edited by Susan Dewey and Patty Kelly. New York: New York University Press, 2011, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 1In this study, I use the terms “prostitution” and “sex work” interchangeably, relying more often on the term “sex work” due to the stigma associated with “prostitution.” I define sex work as the direct exchange of sexual services for money or goods, similar to Abel and Fitzgerald’s definition [4]. When discussing persons or organizations that explicitly object to defining prostitution as a form of work, I employ the terms they use.

- 3Several of the forementioned articles about the emergent research in this area address this issue. For more on the geography of sexuality, specifically sex work and LGBT+ spaces, see Bell and Valentine’s Mapping Desire: Geographies of Sexualities, Maginn and Steinmetz’s (Sub)Urban Sexscapes: Geographies and Regulation of the Sex Industry, and Doan’s Queerying Planning: Challenging Heteronormative Assumptions and Reframing Planning Practice [30,31,32].

- 4I define a brothel as a business of more than one sex worker in which the sexual services are provided on premise, typically managed by a third party to whom sex workers must pay a portion of their earnings. However, there are also instances where sex workers may manage their own brothel as a collective, such as the brothel Danubio Azul in Quito, discussed further in the case study on Ecuador. Some sex workers work out of privately owned premises or their own homes, either collectively or alone; Prior and Crofts [16] suggest that home occupation sex services premises should be considered a separate category from large commercial sex premises. When using the term brothel, I generally refer to a commercial sex premise owned by a non-sex worker third party, and I specify if referring to a sex worker-owned business.

- 5Sex workers were free to choose the time of their interview, and all chose to be interviewed during times they would normally be soliciting clients.

- 6I did not find or hear of any transgender men sex workers in my research, so the term “transgender sex workers” in this study refers to transgender women. I categorize sex workers into female, transgender, and male, rather than cisgender women, transgender women, and cisgender men, both for brevity’s sake and to reflect how the sex workers tended to refer to themselves and each other, as the term “cisgender” is as of now little used in Latin America.

- 7The two former sex workers were both under the age of 18 when they engaged in prostitution, and therefore would be considered victims of child sexual exploitation. Many of the active sex workers also began selling sex before the age of 18. Whether minors who sell sex should be labeled sex workers is a source of debate; some definitions use the term “sex work” to refer only to “consensual exchanges between adults” [58], while others use a broader definition that includes minors [59].

- 8For a history of this law and other prostitution legislation in Argentina, see Guy’s Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires: Prostitution, Family, and Nation in Argentina [61].

- 9All quotes translated from Spanish by the author.

- 10All names are pseudonyms unless last name is included.

- 11Uruguay is the only country in Latin America that has expressly legalized sex work through regulated brothels.

- 12Name changed.

- 13Many of the sex workers referred to these restaurants as bars; I call them cafés to distinguish them from bars that primarily sell alcohol.

- 14Names changed.

- 151000–1500 ARS at time of interview

- 16100–200 ARS

- 17400 ARS

- 182000–3000 ARS, minimum 1000

- 195000 ARS; 10,000 ARS

- 20It is of note that the Argentine and Ecuadorian federal legislation took opposite approaches to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases through prostitution: Argentine legislation by prohibiting brothels but allowing sex work not in brothels, and Ecuadorian legislation by allowing prostitution only in regulated brothels.

- 21Sex workers may have partners or family members who take their money by force or pressure. However, this abuse occurs both in brothels and in the street.

- 22As sex workers are a highly mobile population, these numbers may vary greatly; during the time of this study, the president of Association For a Better Future, Alexandra Flores, claimed her organization had 280 members, 1st of May had over 60 members, and Hope for the Future had over 60 members [77].

- 23González identified the association of sex work with crime as a common stereotype that her office tries to eliminate.

- 24These tables are partially inspired by a similar table by Weitzer [15] on characteristics of different types of prostitution.

- 26For more on feminism’s influence on prostitution and sex trafficking law, see Halley et al. [89].

- 27For instance, in Ecuador, police sometimes enter brothels to check IDs and shut down those where minors are working, incentivizing brothel management to strictly enforce age checks.

| Space of Solicitation (Neighborhood) | Female | Transgender | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street (microcentro and Recoleta) | 10 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Street/Public transport station (Once) | 6 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Street outside café (microcentro) i | 9 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Café (microcentro) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Bar (Recoleta) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Bars/nightclubs and street (mostly Recoleta and Palermo) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 34 | 3 | 4 | 41 |

| Space of Solicitation | Female | Transgender | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street (includes all outdoor spaces) | 19 | 10 | 5 | 34 |

| Brothel | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Internet or social media | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 31 | 11 | 6 | 48 |

| Space of Solicitation | Female | Transgender | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street (Plaza del Teatro) | 12 | 6 | 0 | 18 |

| Street (Avenue Amazonas) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Brothel | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Internet and social media | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 7 | 0 | 28 |

| Space of Solicitation | Female | Transgender | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Brothel | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Social media | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Space of Solicitation | Female | Transgender | Male | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Street | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Street/Park | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Brothel | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 4 | 3 | 5 | 12 |

| Space | Security ii | Agency iii | Earnings iv |

|---|---|---|---|

| Street | Low | High | Depends |

| Brothel | Moderate to high, depending on the brothel | Low to moderate | Depends |

| Business at which sex worker is employee v | High | Moderate | Depends |

| Business at which sex worker is customer vi | High | High | Depends |

| Private premise owned or rented by sex worker | Moderate | Very high | Depends |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Meir, J. Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case Studies of Sex Workers in Argentina and Ecuador. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020042

Van Meir J. Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case Studies of Sex Workers in Argentina and Ecuador. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Meir, Jessica. 2017. "Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case Studies of Sex Workers in Argentina and Ecuador" Social Sciences 6, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020042

APA StyleVan Meir, J. (2017). Sex Work and the Politics of Space: Case Studies of Sex Workers in Argentina and Ecuador. Social Sciences, 6(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6020042