Abstract

While many studies examine how different legal approaches to prostitution affect sex workers’ living and working conditions, few studies analyze how sex workers’ physical workspaces and the policies regulating these spaces influence sex work conditions. Based on interviews with 109 current or former sex workers, 13 civil society representatives, 12 government officials, and 5 other actors in Ecuador and Argentina, this study describes sex workers’ uses of urban space in the two countries and compares how they experience and respond to government regulation of locations of prostitution. Argentina and Ecuador took different approaches to regulating sex work space, which appear to reflect different political ideologies towards prostitution. Sex workers expressed different individual preferences for spaces, and government limitation of these spaces represented one of their major concerns. The results illuminate how sex workers’ workspaces influence their working conditions and suggest that governments should consider sex worker preferences in establishing policies that affect their workspaces.

1. Introduction

“We don’t have a place to work.”—Río, a Buenos Aires sex worker

“All we want is for them to give us a space, nothing more.”—Rosa, a Quito sex worker

On 21 October 2015, a female sex worker performed sex acts with a client in the middle of the sidewalk in the Historic Center of Quito. Surrounding the couple, a group of women screamed, “We are going to have sex in the streets,” and, “Is this what the Mayor wants, is this what the Mayor wants?” [1]. Ecuadorian newspaper El Mercioco posted a video of the incident on its website with the headline, “The protest of the sex workers in Quito has no limits” [2]. Why were these sex workers so upset? The municipality had closed down the hotels where they serviced clients. They demanded that the municipality give them a “dignified space” to work [1].

On 6 October 2016, another group of women, some dressed in cat masks to hide their identities and others in shirts that read “Feminist Whore”, gathered in front of the Buenos Aires legislature. “We don’t need rescuing from anyone”, read one of their protest signs. They were protesting the recent law passed by the legislature to prohibit whiskerías, bars in which the waitresses or dancers are often sex workers [3].

Why did the governments of Quito and Buenos Aires close these businesses, and why did sex workers care so much? What do these sex workers’ reactions to the closures reveal about how sex workers relate to their workspaces?

Conflict over sex work in Western academic and political discourse normally centers on the legality of prostitution, producing fierce debates among policymakers and feminists about how different policy approaches to prostitution might impact the individuals in prostitution and gender relations within society.1 The abolitionist approach argues that prostitution is inherently exploitative and embodies the ultimate form of male dominance over women, and therefore feminists should aim to eliminate the existence of prostitution by criminalizing the purchase of sex [5,6,7,8]. The sex workers’ rights approach, however, criticizes this “oppression paradigm” [9] and argues that prostitution is a legitimate form of work and should be legalized or decriminalized [10,11,12,13].2 With this focus on the legality of prostitution, however, less research examines the effects of more specific policies regarding prostitution on sex work conditions in places where it is legal, and Weitzer [15] identifies the conditions of legal prostitution as an under-researched topic. While there is a growing body of research in this area, for instance in New South Wales (NSW), Australia and New Zealand [4,16,17,18], more research on the conditions within different contexts of legal sex work is warranted, particularly in developing countries.

Because sex work is legal in Argentina and Ecuador, but brothels are illegal in Argentina and legal in Ecuador, these two countries provide the opportunity to examine how sex workers experience different policy approaches to legal sex work. In interviews on the working conditions they face, sex workers in both countries expressed great concern with policies that limited their workspaces. This concern suggests sex workers’ relationship to space as an important topic of exploration. Most of the studies that explicitly identify space as an important component of sex work focus on mapping the geographies of sex work and examining how sex workers’ responses to law enforcement and their environments construct the locations of sex work within cities [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Through case studies of sex work in Argentina (primarily in Buenos Aires) and Ecuador, this study will focus on the types of spaces sex workers use in urban environments, adding to the emerging literature on the “micro spaces (sites and arenas) and strategies” used by sex workers ([4,17,18]; [25], p. 151).

Different types of spaces used by sex workers offer different working conditions. For instance, street-based sex workers are consistently found to experience more victimization than indoor sex workers [15,18]. Street-based sex work, however, may provide sex workers more autonomy and earnings than indoor managed spaces like brothels [4]. This paper seeks to expand the body of knowledge on sex workers’ feelings about the spaces in which they work, how they decide where to work, and how policies regulating these spaces affect the conditions they face. Given the potential influence of sex workers’ workspaces on their working conditions, this study examines how government regulation of these spaces impacts sex workers’ qualities of life. Furthermore, it analyzes how governments’ political ideologies towards prostitution shape their regulation of these spaces and how sex workers respond to government controls.

2. Background: Sex Work and Space

2.1. Geographies of Sex Work

Space, far from a mere background for the activities of society, plays a key role in manifestations of social hegemony and in individuals’ experiences and power. As Hart explains, “It is both uncontroversial and obvious (at least to geographers) that people’s identities are in part constructed through the spatial locations they inhabit and frequent” ([19], p. 215). The physical spaces that groups occupy may indicate their relative status within society, and power is exerted through these spaces [26,27]. Just as marginalized racial, ethnic, or class groups may occupy specific places within a city, so, too, may marginalized sexualities. Gay communities, for instance, often occupy specific neighborhoods or businesses; prostitution similarly occupies specific locations [28,29]. The nature of these spaces influences the experiences and behaviors of the individuals who inhabit them.3

The spaces that sex workers occupy within a city frequently result directly from state control over physical space and deliberate exclusion or tolerance of sex workers in specific places. In their application of Henri Lefebvre [27]’s Marxist theories on the production of space to prostitution, Hubbard and Sanders “contend that the geography of sex work is the outcome of an unfolding relationship between different types of space—the ordered spaces of the capitalist state on the one hand, and the ‘lived’ spaces of the prostitutes on the other” ([21], p. 75). States have a view of the way spaces should function to fulfill the goal of creating a productive society, which they enforce through laws, while sex workers occupy space with the goal of soliciting clients. The overlap of these spaces creates “distinctive geographies of sex work”, in which sex workers occupy spaces where the state will tolerate their presence or where they can escape state control ([21], p. 76). Red-light districts most obviously embody the relegation of sex work to specific spaces in a city. States limit sex workers’ access to certain spaces in their attempts to make the city “a functional and ordered whole”, viewing sex work as morally wrong and therefore “a disturbance to that socio-spatial order” ([21], p. 82). These efforts often reflect a desire to preserve an order of “‘respectable domesticity’—that is the social norms of heterosexual monogamous relationships and reproduction” by creating a “moral geography” that hides non-normative forms of sex from view by the dominant population ([24], p. 101; [29,33]). Policing of sex workers’ access to space marginalizes them both physically and socially; even the creation of legal zones of tolerance may ghettoize them from the rest of society [20,24].

Sex workers frequently find ways to escape or subvert state control, however. Sex workers may refuse to leave their spaces, instead coming up with tactics to solicit clients undetected by police [34]. Alternatively, they may move to other areas of the city or alter their forms of working. In Birmingham, England, sex workers turned to window prostitution as a “tactical response” to prohibitions against street sex work, forming the current red-light district ([21], p. 84). Not only does the state, thereby, shape urban space, but so, too, do sex workers themselves [21]. Sex workers are limited in their “experiences of space” by government control, but they exercise “resourcefulness and resistance” through the “construction of their own particular spaces” ([22], p. 150).

Sex workers can exercise some power against state control through the spaces they create for themselves. As Knopp explains, “As difference is constructed (spatially) to facilitate the accumulation of power, that (spatialised) difference is also empowered. This is true in even the most asymmetrical of power relations” ([26], p. 159). Although states have power over sex workers in excluding them spatially from mainstream society, the spaces sex workers do occupy can symbolize their resilience and provide them a place of their own within society. In Hart’s study of street sex workers in a Spanish red-light district, for example, the area became simultaneously an illicit space and a “safe space” for taboo activities ([19], p. 222). This space and power balance is dynamic; as sex workers adopt strategies to avoid state control, states come up with new ways to control them. For this reason, Hubbard and Sanders describe spaces of prostitution

Sex workers and the law’s constant response to one another creates the spaces of sex work, which move and change over time as a result of this negotiation [35,36].“as the outcome of an ongoing relationship between the ordering enacted by the state, law and citizenry…and the negotiation of this ordering enacted by those who make their living in the red-light district. This identifies the red-light district as always becoming, a complex assemblage made and remade through the folding together of these different types of space.”.([21], p. 80, emphasis in original)

Of course, sex workers and the state are not the only parties that shape these spaces. Clients, pimps, brothel owners, and local residents too contribute to the dynamics of sex work spaces. For instance, clients influence where sex work occurs because sex workers are likely to congregate where there is high client demand. Pimps or individual sex workers may control parts of the street and charge other sex workers to occupy those spaces [37], and prostitutes who are victims of sexual exploitation or trafficking may have little power to control where they work [38,39]. Brothels and other sex work businesses likely choose their locations in reaction to state policies and client demand [36,40]. Other residents may complain about the presence of sex work, leading the state to intervene and force sex workers out of a space where they were previously tolerated [20,41], or to preemptively allow sex work only in nonresidential or industrial areas [42]. These players all have a relationship with the state, and their negotiations may, too, shape sex work spaces and limit the power of sex workers to choose their own spaces. The spaces where sex work takes place, therefore, are the result of conflicting pressures in a complex evolutionary system.

2.2. Spaces’ Influence on Sex Workers’ Conditions

To the extent that sex workers do have control over the spaces where they work (and therefore excluding victims of sex trafficking), and among the spaces that are accessible to them, it’s safe to assume they choose those with the best working conditions. But what are their preferences and concerns, and what spaces provide the best conditions? Working conditions may include a variety of factors: earnings, autonomy, safety, cleanliness, privacy, comfort, distance from home, or relationships with other people in the space. As sex workers choose a space, however, they may have to make trade-offs between desired conditions.

Much of the literature on different sectors of sex work suggests that sex workers experience less victimization within managed indoor sex businesses like brothels4 than in street-based work, as well as possibly escort and private work [18]. Brothels in particular can protect sex workers from violence and theft in providing a safe, familiar location monitored by brothel management [43,44,45,46]. In Nevada, USA, many legal brothels have emergency buttons in the bedrooms so sex workers can call in security if a client becomes violent or refuses to wear a condom [43,46,47]. These buttons do not guarantee safety, as a sex worker might not always be able to reach the button if a client becomes abusive [43], but they can add an additional level of protection. Brents and Hausbeck suggest that safety in the brothel comes from “working in a setting that allows constant public scrutiny of the behavior of the customer before the actual paid party, that makes client anonymity and easy exit difficult, and that provides a houseful of people just a flimsy door away” ([43], p. 281). More important in determining the relative safety of a sector of sex work may be the site of provision rather than the site of solicitation; Prior, Hubbard and Birch [18] found that 52.6% of sex worker incident reports in NSW, Australia occurred in an assailant’s vehicle or the sex worker or assailant’s residence, sites more likely to be used by street-based, escort, and private workers. Brothels can thus provide security as compared with street-based or escort and private work, where sex workers may not have protection from client violence unless they pay a guard or pimp, who may also exert violence [39,48,49,50].

Sex workers who choose to work in a brothel for its security, however, must trade off income and agency. Sex workers in brothels often pay around 50% of their fees to brothel management [43,46,51,52]. Further, brothel-based sex workers may have less freedom to come and go as they please or to choose their clients. A study of 772 sex workers in New Zealand found that street-based sex workers preferred the greater autonomy and earnings of working in the street [4]. Yet the sex workers who chose to work in brothels viewed the downsides as worth the benefits [4]. The Nevada sex workers interviewed by Brents and Hausbeck [43] generally viewed the safety provided by the brothel as worth the decrease in income and felt free to leave the brothel when they wanted, despite requirements that they remain on brothel premises any time they are contracted to work. Similarly, migrant sex workers in Belize felt that brothels gave them “a large degree of self-autonomy” ([45], p. 31). Conditions can vary greatly between brothels depending on size, location, and management practices [47]. Sex workers’ choice of space to work depends upon their perceptions of conditions in all the spaces available to them and how they prioritize these conditions.

Sex workers may also develop personal attachments to their places of work. Both indoor commercial sex premises and outdoor sex work spaces can serve as important areas of socialization [4,19,53,54]. Street sex workers may decide to remain on the streets even if safer indoor alternatives become available because they like the environment’s familiarity and culture and may form strong social bonds with other sex workers and with clients [19,20]. Sex workers in brothels may also value socialization with other sex workers and with clients [4,53]. This socialization with other sex workers is less likely to occur in home-based sex work [16]; however, the home provides greater opportunities for other forms of socialization with children or other family members. It follows that sex workers’ spatial preferences may further depend on what spaces they are used to and may vary widely between individuals.

Government regulation of sex work spaces can significantly change the conditions sex workers face. Shutting down commercial sex establishments may drive sex workers to work on the streets or in more private, underground forms of indoor sex work, where they face more danger and law enforcement authorities are less able to monitor for exploitation [51]. Legalizing brothels could improve brothel conditions by creating regulations for the protection of sex workers and clients. Brothel codes can ensure that sex workers are working in safe and sanitary conditions, and contracts between sex workers and brothels enable sex workers to seek legal redress if the brothel does not follow the terms of the contract [46]. When brothels are unregulated, prostitutes do not receive legal status as workers and brothels have no legal obligations to them, leaving the workers in a vulnerable position [51].

However, simply legalizing brothels may not be sufficient to improve conditions. Just as brothels may operate outside the law when brothels are illegal, they may illegally operate outside of code when brothels are legal. Some brothels may choose not to comply with regulations because they can save on costs, or they may profit from exploiting their workers. Operation outside of code is more likely if regulations on brothels are constructed to make the operation of a legal brothel very difficult or expensive. For instance, in NSW, Australia, despite state law allowing brothels to operate as legal businesses, some local governments continue to place stricter regulations on brothels than other businesses [40,55,56]. Local governments and councils may subject them to restrictions intended not for the safety of sex workers but to discourage the existence of brothels, based on beliefs that they breed crime and contribute to moral corruption [40,56]. These restrictions may dis-incentivize some brothels from operating legally because obtaining legal status is much more expensive than continuing to operate illegally [40] or because seeking registration would bring attention to a business that previously operated without community or council knowledge, risking the business being shut down if not approved [55].

Governments control sex work space not only through legislation but also through regulations and implementation choices. Law enforcement chooses where to enforce laws against street prostitution, for instance [21], and local governments sometimes implement federal laws regarding brothels or other sex work spaces in a way that undermines the law’s intended purpose [40]. These choices all influence what spaces sex workers have access to and therefore the conditions they experience.

In light of the discussion above, this study therefore asks several questions: First, what is the relationship between sex workers and space, and what conditions do they experience in different types of spaces? Second, how do their interactions with the state influence the spaces they use and the conditions they experience? Finally, how do states decide how to regulate sex work space, and what strategies do sex workers employ to negotiate these spaces with the state?

3. Methods

I examine sex workers’ relation to space and policies regulating sex work spaces based on case studies of sex work conditions in Argentina and Ecuador. These two countries provide an opportunity for policy comparison, because brothels are criminalized in Argentina but permitted in Ecuador. Surveying a random sample of sex workers in different spaces in each country was not possible due to the wide diversity of locations where sex work can take place, lack of data about the population as a whole, limited time and geographic access, and safety concerns. I therefore used a snowball sample approach to interview sex workers and other relevant actors, including sex worker organizations, other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work on prostitution, and government officials to ask about the conditions faced by sex workers.

These interviews were semi-structured to obtain a comprehensive view of the conditions of sex work in the countries and to allow interview participants to explain the factors they considered most important. Questions for sex workers were designed to be open-ended and elicit storytelling to reveal their experiences and perceptions. I also sought to find out how participants thought sex work conditions could be improved and what legal model of sex work they wanted. To address the influences of brothel legality on sex work conditions, I specifically asked about the conditions sex workers faced in brothels versus other spaces. I asked additional questions in response to participants’ answers and varied questions as seemed contextually appropriate. All subjects gave their informed verbal or written consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. Methods were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (D0542) on 5 May 2016. See Appendix A for a list of all interviews conducted, Supplement A for a list of typical questions, and Supplement B for consent forms used.

3.1. Argentina

Interviews in Argentina took place in the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires in late May and early June 2016. I obtained interviews with 41 active sex workers on their personal experiences in prostitution by directly approaching individuals at their places of work with a small flyer with information about the study (see Supplement C) or through snowball sampling. Interviews took place in the locations where sex workers operated or in a nearby kiosk or café chosen by the sex worker, during their working hours.5 I interviewed 25 sex workers who worked in the microcentro, the center of the city. As a hub for business and tourism, the microcentro was safer and more easily accessible than many of the other areas of prostitution in Buenos Aires. Five participants worked in Recoleta, another upper-class area; ten in Once (officially called Balvanera), a lower-class neighborhood home to many immigrants; and one in other locations (see Figure 1). Due to time and financial constraints, I was unable to conduct interviews outside of the city of Buenos Aires, so information on sex work in other parts of the country relies on information provided by interview participants and secondary sources.

Figure 1.

Interview locations in Buenos Aires. Red stars indicate approximate areas interview participants identified as places where sex workers concentrate. Numbers indicate number of sex workers interviewed in the area. Map from Google Maps.

Most interviews lasted between 15 and 40 min. Each participant interviewed about their personal experiences received 300 Argentine pesos (ARS) (about 21.50 USD at time of interviews) for their time, as recommended by an NGO, except for two who received 500 ARS (about 36 USD) because their interviews lasted significantly longer than originally requested.

Of these participants, 34 were female, three were transgender, and four were male.6 The sample includes 27 sex workers who originated from Argentina, five from Paraguay (one of whom grew up in Buenos Aires), two from Uruguay, two from Brazil, two from Dominican Republic, one from Peru (but grew up in Buenos Aires), and two were not recorded. Among those who grew up in Argentina, 19 originated from the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, three from Buenos Aires province, two from Salta, one from Catamarca, one from Misiones, one from Tucumán, and five were not recorded. They ranged in age between 20 and 60 years old, with a mean of 34.5, median of 34, and standard deviation of 9.0 years (excluding two participants whose age was not recorded). The spaces where these participants reported soliciting clients are broken down by gender in Table 1. Because these data were obtained through convenience and snowball sampling, they should not be interpreted as representative of the population of Buenos Aires as a whole. For instance, I was unable to obtain interviews with sex workers in private apartment brothels or those who solicit by internet or public advertisement. However, some sex workers had previously operated in other types of spaces and could provide insight into the working conditions of those spaces. It is also important to note that these locations are not fixed; many sex workers changed spaces depending on changes in government policy, business owner attitudes, or client behavior, as discussed further in the case studies.

Table 1.

Sex worker participant spaces of solicitation in Buenos Aires, Argentina by gender.

Amongst NGOs, I interviewed the Secretary General of the national sex workers union Association of Women Prostitutes of Argentina (AMMAR); representatives of AMMAR’s provincial chapters in Entre Ríos, Mendoza, San Juan, Neuquén, and Santiago del Estero; multiple representatives of the prostituted women’s organization Association of Argentine Women for Human Rights (AMADH); the Secretary General of the Network of Women Sex Workers of Latin America and the Caribbean (RedTraSex); and representatives of two anti-trafficking organizations. I also rely upon 11 interviews I conducted with anti-trafficking NGOs and government officials in Buenos Aires in 2015 for Judith Kelley’s Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior [57].

3.2. Ecuador

Interviews in Ecuador took place from June to August 2016. I interviewed 46 active sex workers and 2 former sex workers7 on their personal experiences in prostitution, primarily through introduction by leaders of sex worker organizations, as well as through snowball sampling. Of these, 28 worked in Quito, 12 in Machala, seven in Guayaquil, and one in Milagro (see Figure 2). Interviews took place in the locations where sex workers operated during their working hours, except for several interviews in Guayaquil that took place in a park and one in Quito that took place in a restaurant. Most interviews lasted between 10 and 30 min. Each of these participants received 20 USD compensation, based upon a recommendation by two sex workers’ organizations.

Figure 2.

Interview locations in Ecuador. Numbers indicate number of sex workers interviewed in each city. Map from Google Maps, edited to include Milagro.

Of the sex workers who were interviewed about their personal experiences, 31 were female, 11 were transgender, and six were male. Among these participants, 40 originated from Ecuador, seven from Colombia, and one from Spain. Of the Ecuadorians, 10 originated from Guayas province, 10 from El Oro, seven from Manabí, six from Los Rios, four from Pichincha, one from Esmeraldas, one from Chimborazo, and one was not identified. They ranged in age from 18 to 59, with an average of 36.0, median of 34.5, and standard deviation of 11.3 years. The spaces where all these participants reported soliciting clients are broken down by gender in Table 2, followed by Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 which show soliciting spaces by gender in Quito, Guayaquil, and Machala, respectively. The single participant in Milagro was female and solicited in the street. For the same reasons described in the previous section on methods in Argentina, these data should not be considered representative of the sex worker populations as a whole.

Table 2.

Sex worker participant spaces of solicitation in Ecuador by gender.

Table 3.

Sex worker participant spaces of solicitation in Quito, Ecuador by gender.

Table 4.

Sex worker participant spaces of solicitation in Guayaquil, Ecuador by gender.

Table 5.

Sex worker participant spaces of solicitation in Machala, Ecuador by gender.

I also interviewed leaders of four sex worker organizations in Quito, three in Machala, two in Guayaquil, and one in Milagro. Two of these leaders are included in the personal interviews. Other interviews include seven representatives of other NGOs, five municipal officials in Quito, four owners or managers of businesses where sex work takes place, and one physician.

4. Case Study: Argentina

4.1. Background

4.1.1. Regulation of Sex Work

Independent sex work is legal at the federal level in Argentina, but brothels and other third parties that profit off sex work are illegal, as is advertising sex work. Articles 15 and 17 of Law 12.331 on Profilaxis of Venereal Disease of 1937 prohibit the “establishment of houses or premises where prostitution is practiced, or where it is incited” [60].8,9 In 2011, Presidential Decree 936/2011 on the Comprehensive Protection of Women also prohibited “notices that promote offers of sex”, on the basis that these advertisements promote the exploitation of women and facilitate human trafficking, and established the Office of Monitoring of Publication of Sex Trade Offer Notices.

Although no federal law prohibits independent sex work, Amnesty International [62] reports the 2012 anti-trafficking law has been used in practice to criminalize autonomous indoor sex work. The original law, passed in 2008, contained a clause that required victims to prove they had not consented to being trafficked, despite pressure from anti-trafficking NGOs and the US government to make consent irrelevant regardless of age. The legislature finally revised the law in 2012 due to public outrage after the accused traffickers of well-known trafficking victim Marita Verón were acquitted (Araujo, Caminos, Colombo, Encinas, and Rodriguez interviews 2015). While this revision satisfied many anti-trafficking activists, however, its lack of clear distinction between consensual sex work and sex trafficking has proven problematic for many sex workers. The law considers exploitation an “aggravating factor” of trafficking, which authorities have interpreted to mean that any “form of involvement in the organization of sex work” is trafficking ([62], p. 27). Sex workers who facilitate the sex work of others, for instance by managing a shared apartment, can thus be considered traffickers under the law [62]. Individuals who consider themselves autonomous sex workers may be treated as trafficking victims even if they insist they are not [62].

Additionally, indoor autonomous sex workers are often subjected to “code inspections” of the residences in which they work [62]. Police may claim they are need a business license and post signs that the business has been shut down, as though the location were a business and not a residence, despite the fact that no business licenses exist for sex work [62]. Sex workers reported that it was unclear under what law police were conducting these inspections [62].

Misdemeanor codes penalize various forms of prostitution, particularly in spaces that are visible to the public, in every province except for Neuquén, Río Negro, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba [63]. Law enforcement may charge sex workers with “offensive or scandalous public behaviour” [64]. In the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Law 1472, Article 81 criminalizes the offer and demand of sex “in an ostentatious manner in non-authorized public spaces”. Although most cases of violations of this law are thrown out due to lack of evidence, Buenos Aires sex workers, particularly transgender sex workers, are often asked by police to show identification and can be given fines or probation [62]. Sex workers therefore face limitations on the spaces they can use, both by explicit legislation and by law enforcement’s interpretation of legislation, even if the actual exchange of sex for money is legal.

4.1.2. Sex Worker Organization

Sex workers in Argentina began organizing in 1994, when a group of Buenos Aires street prostitutes founded the Association of Women Prostitutes of Argentina (AMMAR) to oppose police abuse [65]. After being granted office space by the Central of Argentine Workers (CTA) union in 1995, AMMAR officially joined the CTA in 2001 [65]. AMMAR now has branches in nine provinces and the city of Buenos Aires and fights for the recognition of sex work as legitimate work and an end to police harassment and abuse of sex workers.

In 2003, however, a group of members of AMMAR in Buenos Aires broke from the organization and formed AMMAR-Capital on the basis that they did not agree with the conception of prostitution as work. Considering themselves “people in a situation of prostitution”, they now call themselves the Association of Argentine Women for Human Rights (AMADH) to distinguish themselves from AMMAR and have branches in the capital and the provinces of Tucumán and Santa Fe. They take an abolitionist stance towards prostitution and work to help women who want to leave prostitution to find other job opportunities.

Buenos Aires is also the headquarters of the Network of Sex Workers of Latin America and the Caribbean (RedTraSex), which incorporates sex worker organizations in 15 countries, currently headed by founder and former president of AMMAR Elena Reynaga.

4.2. Sex Workers’ Use and Experience of Space

Sex work in Argentina occurs both indoors and outdoors in diverse types of spaces. Brothels operate undercover, either within private apartments or within legally registered businesses such as bars or nightclubs. Some independent sex workers operate out of their own residences individually or share private apartments with other sex workers. Sex workers may also operate independently out of existing businesses, soliciting clients there and then taking them to a nearby hotel. In Buenos Aires, many sought clients in bars and clubs, either as an independent customer or as a hostess or dancer employed by the business. Other sex workers interviewed for this research solicited clients in late-night cafés. Few legal businesses where sex work takes place remain in existence in Buenos Aires, however, due to the increased enforcement of anti-brothel laws since the passage of the 2012 anti-trafficking law. Sex workers also solicit on the street and in parks, typically engaging in sex in the client’s car or a hotel.

4.2.1. Brothels

Consistent with the literature on brothels, brothels in Argentina provide advantages and disadvantages to sex workers: they provide a level of protection from the dangers of the street, but they also subject sex workers to the power of the brothel owner and typically take 50% of their earnings. Despite their disagreements about whether prostitution is inherently exploitative, both the abolitionist and sex workers’ rights organizations interviewed believed brothels are exploitative. RedTraSex explicitly opposes brothels and any third parties who profit off sex workers, preferring independent sex work.

Since the passage of Argentina’s 2012 anti-trafficking law, law enforcement in Buenos Aires has cracked down on businesses selling sex. Rather, brothels operate out of private apartments called privados (privates). While none of the sex workers interviewed were currently working out of a privado, several of the women had worked in one in the past, and many knew of someone else who had. The women there work short turns of about 15 min and often must service many clients in a day. Clarisa,10 a sex worker in the microcentro, complained that in privados she had to work 12-h shifts and could not choose her clients. “It’s really ugly”, she said. Violeta, who works in Once, worked six years in privados, but she moved to the street because the privado took 70% of her earnings. Many of the privados too were being closed due to the anti-trafficking law, except, according to AMADH, those that paid bribes to police.

The privados, because of their clandestine nature, sometimes serve as sites of trafficking or sexual exploitation of minors. Mónica, a female sex worker now working out of a café in the microcentro, saw minors when she went to a privado: “The woman went to look in Paraguay, in Misiones, for 13, 14, 15-year-old girls. But the girls wanted to, eh. The girls wanted to [go to Buenos Aires to sell sex].” Viviana, a sex worker in Once, also saw Paraguayan minors when she worked in privados many years ago. The girls were not being forced, she said, but had likely been misled about the conditions they would face and didn’t realize they would be working “without rest”. Mónica, however, did witness one 15-year-old who was not allowed to leave. “She stayed there always, in the…apartment.” Mónica gave the girl her phone number and told her she ought to work on her own. “What happens is the owner arranges things with the police. It’s all a mafia.” Sandra, a friend of Mónica’s, had also witnessed human trafficking in the privados. She began working in a privado after moving to Buenos Aires from Uruguay, where she had worked in the country’s legalized brothels.11 “The privados here were horrible. Horrible. I had to leave in a hurry because I saw the, uh, kidnapped girls.” The girls came from Peru and Chile under promises they would be doing domestic work, but once in Buenos Aires, they were held without any contact with the outside world. Sandra reported the incident. “Here in Argentina”, she said, “the police, judges, lawyers, all of them are involved in prostitution …and they don’t do anything because they’re making money too.”

Not all privados are places of exploitation, however. The term privado can also refer to an apartment that sex workers rent and work out of collectively, each keeping their own earnings, or to a private apartment used by a single sex worker. AMMAR and RedTraSex view this model of independent sex work as ideal, because it provides sex workers the most autonomy. Unfortunately, the police seemed not to distinguish between residential apartments run by independent sex workers and those run by a third party, sometimes treating the former as if they were sites of trafficking. AMMAR complained of police raiding sex workers’ apartments and taking their belongings, consistent with the Amnesty International study in which every indoor sex worker interviewed reported experiencing raids, often involving “violence, intimidation, and theft of personal property” [62]. “Where can I work, in what place can I work, without being persecuted?” asked AMMAR General Secretary Georgina Orellano.

The existence of privados is ever present in Buenos Aires. After the federal government prohibited the advertising of sex work in 2011, sex workers and sex work businesses began advertising on Facebook pages and printing out papelitos, little papers, that they plaster on poles and signs across the city (see Figure 3). The city of Buenos Aires then passed a law in 2012 to prohibit flyers advertising commercial sex in public spaces, to no avail. In response, abolitionist groups have run campaigns to rip all the papers down. While abolitionists see the papelitos as advertising the exploitation of women, independent sex workers view them as a necessary resort for finding clients. When the municipality of Buenos Aires created a public campaign in August 2016 to urge people to tear down and report sex work advertisements, AMMAR created mock papelitos reading “Sex Work is NOT Trafficking”.

Figure 3.

Papelitos advertising sex work. Photo by author.

Multiple sex workers mentioned the ban on sex work advertising as a problem, preventing sex workers from obtaining clients. The ban, in combination with the closing of privados, has forced sex workers to wait for clients in any bar that remains open or in the street, said Río, a female sex worker who works out of a café in the microcentro. According to Amnesty International [62], the law against sex work advertising has contributed to an increase in street sex work.

4.2.2. Bars

The Argentine government and NGOs’ attempts to fight trafficking have also led to the shutdown of many bars where sex workers used to operate. Buenos Aires used to be full of cabarets, whiskerías, and boliches (clubs or bars) known for having sex workers. Sex workers sometimes used these terms to refer to brothels that took a percentage of incomes, but more often they referred to businesses that allowed them to keep their own earnings. Many of these locations got around the prohibition against brothels by registering as bars and hiring women as dancers or hostesses who also offered sex on site or in a nearby motel [66]. As employees, the women could receive a 50% commission on drinks clients bought, and the bar benefitted from the increased business. Other bars treated sex workers like any other customer, merely charging them an entrance fee or requiring them to purchase a drink, and the actual sexual exchange occurred elsewhere.

Since the passage of the 2012 anti-trafficking law, however, nearly all of these bars have closed. Río, a female sex worker, explicitly tied the closings to the anti-trafficking law. “They mix us up with trafficking”, she said. The anti-trafficking organization La Alameda led efforts to shut the bars down, sending people with undercover cameras to expose them and alleging the businesses were participating in sex trafficking. AMMAR has organized protests against La Alameda’s leader Gustavo Vera, a legislator of the City of Buenos Aires and friend of Pope Francis [67]. They criticize his attempts to “rescue” sex workers by shutting down their places of work, which AMMAR General Secretary Orellano claims only leads sex workers to conduct their work in public spaces, exposing them to greater rights violations [68]. In turn, Vera accuses AMMAR of supporting pimps and organized crime [66]. Attempts to contact Vera for this research were unsuccessful. Subsequent to my interviews in Buenos Aires, Vera and two other legislators passed an initiative to shut down all bars and other businesses operating as brothels [66].

At the time of this research only a couple bars remained in operation, which sex workers speculated had political connections. The closings have led female sex workers to crowd into the remaining bars, resulting in more competition and a reduction in earnings. I managed to interview two sex workers in one of the bars, Blue Star,12 but as soon as the manager noticed, she asked me to leave, likely fearful that I might be working undercover to expose the bar.

Many of the street sex workers interviewed who had formerly worked in these bars viewed them positively and complained they now had no other place to work. Kelsi, a Dominican sex worker, believed they were “more just than privados” because they were less exploitative. The sex workers had never seen trafficking in the bars; all the women there, to their knowledge, were adults working of their own volition. The two women working in Blue Star, Casandra and Talia, asserted there was no trafficking there. Casandra suspected that Gustavo Vera used La Alameda to gain political power. “The police know there’s no trafficking here”, she said.

4.2.3. Cafés13

In addition to the bars, 17 interviews took place at two different confiterías, or Parisian-style cafés, in the city center, Montecarlo and El Mundial14. These businesses operate as normal restaurants during the day but at night, women would often sit inside at a table and wait for clients. The spaces provide them refuge and comfort compared with street sex work. Many of the women described this form of sex work as ideal; the cafés treated them like normal clients, profiting only off the increased business the sex workers brought in. The women could come and go when they chose, and they did not have to dress skimpily like they would in a boliche. Juliana, who worked out of El Mundial but had previously worked out of Montecarlo, said, “The best method of work is this, in a café.” Unlike in street sex work, where a client could easily come with bad intentions, the café has cameras. “I feel safer”, she said. Like in bars, the setting allowed sex workers to talk with clients and assess whether they might be aggressive or violent before agreeing to leave with them. Typically, a client would invite a woman over to his table to converse and buy her a drink, allowing each to decide whether they wanted to proceed with the exchange. “A girl who enters a car doesn’t have time to get to know the client”, said Juliana.

Like the bars, sex workers are losing access to these cafés. While Montecarlo used to be full of sex workers, they are now only allowed to stand outside the restaurant. A few months before my interviews, a girl came to the café with a hidden camera to expose the prostitution occurring there. Ever since, the owner refused to let the sex workers inside, telling them he would get in trouble with the police if he did. The women complained of the difficulties of being outdoors, where they had to stand on their feet for hours at a time in the cold. The policies prohibiting any business from promoting prostitution, far from rescuing these women from exploitation, made their working conditions more difficult. Clara, a sex worker at El Mundial, explained, “There are places [the police] closed that are almost like this, that they do close for the fact that you’re working. Then the girls end up in the [street] corners. For me, that’s more dangerous than being in a bar.” A similar café, Café Orleans, was shut down for having prostitution in 2015 [69]. Although the women at Montecarlo could move to El Mundial, they received more clients at Montecarlo. The women in El Mundial were on average older than those at Montecarlo and less willing or able to stand outside in the cold for long periods of time. Sex workers chose the space that provided the optimal conditions for their needs.

Lack of access to indoor workspaces was a major concern for the women who formerly worked in Montecarlo. “We don’t have places to work anymore,” lamented Valentina. Because of their exclusion from indoor spaces, Rocío said, “we feel discriminated against.” When asked what she thought could be done to improve sex work conditions, Marina responded, “give us a place of work.”

4.2.4. Street Work

In the wealthier areas of Buenos Aires, including the microcentro and Recoleta, street sex work takes place only at night. Most of the sex workers in the microcentro are female, though there are some trans women as well. They generally charge about 70–110 USD for an hour.15 Male sex workers concentrate on a specific street corner in Recoleta. In lower-class areas, like Once, Flores, and Constitución, many sex workers work during the day. Both male and female sex workers work out of the Once subway station and plaza. They charge much less than the street workers in the microcentro or Recoleta, generally between 7 and 14 USD16 for 10–30 min and up to 29 USD17 for an hour. Another area of the city, the bosques de Palermo (Palermo woods), serves as a zone of tolerance for transgender sex work. At night, transgender sex workers fill the parks, and clients drive by to pick them up.

In addition to the physical strains of working in the street, sex workers perceived street work as more dangerous. The inability to assess a client before getting in his car puts them more at risk of ending up with a violent client, although most street sex workers interviewed had never or only once had a violent client. Andrea, a street sex worker in Once, explained, “Here anything can happen to you. You understand? Whereas in a boliche you do have security, understand?” Clara expressed similar sentiments:

Boliches had registers of who entered, and in the café, her friends look out for her. “But in the street, no one is going to take care of me,” she said. “It’s very hard. You have to be very brave to work in the street,” said Clarisa. Street sex workers sometimes experience violence or robbery from homeless drug users or drunks. Estela, who works outside Montecarlo, explained she acts nice to the street youth so that when they’re drugged on paco, cocaine paste, they don’t attack and rob her.“It bothers me when they go to a boliche, where high quality people go…and [the authorities] make a fuss there because…it’s not being in the street…like a typical prostitute left in the street picking up guys in their car. By contrast I worked in a boliche, they closed it, I had to go to the corners, the street, that is, walk, and if a car stopped me I stopped, I got in.”

Sex workers may also receive less money in the street than in a bar. Pilar, who works outside Montecarlo, said clients see street sex work as more desperate and degrading, “so they take advantage of you and offer you less money.” Now that the few remaining bars are so full of women, however, many make more money on the street because they receive more clients. Gisel, who now works on the street in Recoleta, charges about 145–220 USD for a turn, minimum 70.18 In the boliches, she said, women earn 360 or even 720 USD from a client, but now that there is so much competition, they might get only one client in a night, if any.19 Yesenia, who works in the microcentro, said she used to get about 220 USD for one boliche client, while in the street she makes about 70–110 USD.

Although many sex workers did not want to work in the street, some preferred it. Andrea, who had previously worked in a boliche that required her to give up half her earnings, explained, “In a boliche you had to present yourself. Heels…or underwear. And the difference was they gave you half and half. Whereas we work like this, how we want, and all the money is ours.”

Not all street prostitutes have this freedom; some have pimps who take their earnings. Belén explained that these tend to be younger girls whose partners mistreat them and Dominican migrants who are forced to do prostitution to pay the debt of their passages. “I was seven years in the street under threat to my daughter [by my pimp],” said Margarita Peralta of AMADH. These cases can be considered human trafficking. Though many sex workers I interviewed had not witnessed pimping, Gonzalo, a male sex worker who works in the street and in gay clubs, had seen more organized crime. He had worked “under a boss” before and believed all the streets are controlled by “bosses” who charge sex workers a portion of their earnings.

In contrast to the Amnesty International report, most street sex workers reported having no problems with the police. Jessica, a trans street worker in the microcentro, described her relationship with the police as “very good”. A few did mention police raids, however. Sabrina at Montecarlo said the police normally do not bother them, but there are some times in which the police say they have to “clean the zone”, and they might give a sex worker a violation. After the third violation, they’ll arrest you. Dominicans are particularly likely to get violations, she said, because the police know they may be undocumented. Sandra mentioned that not long ago police were bothering sex workers, not letting them work, asking for their documents and taking them to jail.

Street sex workers, too, wanted a space to work. Jessica wanted sex workers to have “a place where we can all work, with hygiene, prevention…people who take care of us”. Some female sex workers, like Kelsi, wanted the government to grant them a similar zone to that for trans sex workers. AMMAR, however, opposes red zones; Georgina Orellano believes they ghettoize sex workers and expulse them from public life. Many Argentine sex workers viewed independent, indoor sex work as ideal, but policies restricted them to street-based solicitation. “We don’t have a place to work,” Río told me.

5. Case study: Ecuador

5.1. Background

5.1.1. Regulation of Sex Work

Like in Argentina, sex work in Ecuador is legal, though no law recognizes prostitution as work. Unlike Argentina, Ecuador permits the operation of brothels. Previously, the Health Code prohibited “the clandestine practice of prostitution” but explicitly stated that prostitution was “tolerated in closed premises”, prostitutes had to get regular health checks, and brothels must obtain sanitary permits [70].20 In 2008, however, explicit references to prostitution were removed from the health law [70]. Multiple recent Ministerial Agreements by the Ministry of Health make brothels subject to controls and require them to fulfill certain health requirements. For example, Ministerial Agreement No. 4911, enacted in 2014, requires that brothels clean twice a day and provide basic amenities. They must also provide security and “[m]onitor the health of the sex workers”. Ministerial Agreement No. 1784, passed in 2010, gives the national police authority to “control the legality of activities in centers of tolerance” [71], and Ministerial Agreement No. 2521, passed in 2012, prohibits houses of tolerance from operating near “educational centers, hospitals, clinics, sanitariums, churches and residential zones” [70]. In July 2015, the Ministry of the Interior imposed regulations on the hours brothels can operate, limiting the hours of “evening centers of tolerance” to 11 am–8 pm Monday through Saturday and “nocturnal centers of tolerance” to 4 pm–12 am Monday through Thursday and 4 pm–2 am Friday and Saturday [72].

No legislation specifically addresses sex work that does not occur within these enclosed centers of tolerance. This lack of legislation leaves street sex work in “a gray area of jurisdiction” [34], which has resulted in the use of “public order offenses” to charge outdoor sex workers [64]. Activism by sex workers to exert their rights to public space and expose police abuse, however, has led to greater tolerance of street sex work in recent years.

5.1.2. Sex Worker Organization

Ecuador was the first country in Latin America where sex workers officially organized. On 22 June 1982, over 300 women from the brothels of El Oro province united in Machala and founded the Association of Autonomous Female Workers “22nd of June” [10,73]. The organization’s success in organizing a sex workers’ strike throughout the province and negotiating better treatment from brothel owners in 1988 inspired other sex workers across the country to form their own collectives [65,73]. According to Lourdes Torres, the president of the brothel-based sex workers’ organization Association Pro-Defense of Women (ASPRODEMU) in Quito, Ecuador is the only country in the world in which every province has at least one sex workers’ organization. Machala is currently home to the headquarters of the Latin American Platform of People Who Exercise Sex Work (PLAPERTS) (see Figure 4), the Latin American branch of the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). Unlike the RedTraSex, PLAPERTS and the NSWP do not oppose third parties who facilitate and profit from sex work, like brothel owners (though they do oppose trafficking and exploitation by third parties). These organizations advocate for sex work to be recognized as legitimate work, fight to improve the working conditions sex workers experience, and educate their members about their rights and necessary health precautions.

Figure 4.

Latin American Platform of People Who Exercise Sex Work (PLAPERTS) headquarters in Machala. Sign reads, “International Office of Sex Work and Public Policies.” The logos at the bottom, from left to right, are for the Association of Autonomous Female Workers “22nd of June”, Collective Flor de Azalea, and PLAPERTS. Photo by author.

5.2. Sex Workers’ Use and Experience of Space

Sex work in Ecuador takes place primarily in brothels or on the street. In brothels, sex workers typically pay the owner a fixed price per day, per week, or per client. In street sex work, sex workers solicit clients on a street or in a plaza or park and then usually take them back to a hotel; the client pays the sex workers’ fee and the hotel cost. Others use the Internet and social media to find clients.

5.2.1. Brothels

Sex workers in Ecuador generally believed brothels provide more security than street sex work. The brothels consist almost exclusively of female sex workers, who tend to be younger than female street sex workers. Like in Buenos Aires, younger sex workers choose brothels for their greater protection and privacy, and brothel sex workers expressed preference for working indoors because they perceived the streets as more dangerous. They also experienced less violence than street workers; most brothels have security guards and cameras outside the rooms, and many also have panic buttons in the rooms.

The quality of conditions in brothels varies. One brothel in Quito, Habana Club, provided relatively good conditions, cleaning the rooms regularly and providing sex workers with toilet paper and condoms, unlike some brothels that charge women for these items. They charged clients $21 for a 20-min turn in a room. To incentivize women to come to work early, the club allowed them to keep $20 per client if they showed up before four pm and $15 if they showed up after four. The women also earned two dollars per drink a client ordered for them. The club’s owner had a close relationship with sex worker leaders, particularly Lourdes Torres, the president of ASPRODEMU. One woman at Habana, Gabriela, said the owner was much better than other brothels where she had worked. “It makes me want to cry when a place like this closes,” she said. “In this establishment there’s a lot of security,” said another woman, Susana. “Here they have always treated me super well.”

Other brothels provide poorer conditions and exploit sex workers economically. According to Karina Bravo, director of PLAPERTS and president of Collective Flor de Azalea in Machala, brothels in some cities hold women’s identification documents and only pay them at the end of the week, claiming the practice protects them from robbery. If they must leave in the middle of the week, the women may earn nothing. Many brothels operate in violation of health regulations, while others illegally charge sex workers for access to hygiene supplies like soap or toilet paper. Brothels may also overcharge sex workers for their rooms. Juanita, a sex worker at the largest brothel in Machala, La Puente (see Figure 5a,b), complained that after paying $220 per month for her room, she is left with only $200. Women at La Puente also complained about lack of security. Although an administrator of the brothel assured me if something happens in a room, the women can easily call him, only one of the four women interviewed at La Puente felt secure. Juanita worried that with the noise of the music, no one could hear if something happened in the rooms. “You have to take care of yourself,” Fiona said. By the time the guards get to the room, she explained, the client could have killed you.

Figure 5.

La Puente brothel in Machala, Ecuador. Photos by author.

Lack of transparency in government regulations of sex work establishments posed challenges to some brothels’ operation. The two businesses interviewed in Quito wanted to comply with regulations, but they struggled to find out what the regulations are. “We aren’t against them imposing laws or norms on us,” said David, the manager of Habana Club. He favored protection of sex workers but described the regulations as a game between the municipal and national government, with the municipality telling businesses one thing and the national government another. Elizabeth Martinez, the owner of Akershuz, complained the municipality would not provide businesses with the necessary documents to obtain a permit and then punished them for not having one. Permits to operate a brothel could cost $800 or more, and fines for not complying with regulations could cost more than $1500. The municipality of Quito, she said, wants to make all sex work businesses relocate outside of the city. Shortly before these interviews, the government had temporarily closed Habana Club for not sending a requested document, even though the brothel said the document was in the mail. “We are persecuted by the authorities,” lamented Martinez.

Sex workers favored regulations that led to improved sanitary conditions but found the recent regulation of brothel hours harmful. The hour limitations eliminated times they normally receive clients, such as weekday early morning or Sundays. According to several sex worker leaders, the government made the decision without consulting sex workers or analyzing their schedules and economic situations. “The government has never listened to the voice of the workers,” said Bravo. Ariana, a sex worker at Guayaquil brothel Las Rosas (see Figure 6), recounted that prior to the hours change, the brothel operated 7 am to 8 pm. The hours worked well for her because she could drop her children off at school in the morning, come to work, go back to pick them up after school, and return to work in the evening. Whereas she used to receive many clients in the mornings, the brothel is empty with the later opening time. She also liked being able to work Sundays in the past to earn more money. “I would like for the President…to help us sex workers on this point…It’s just the hours, nothing else. It’s the only thing that harms us, the hours.”

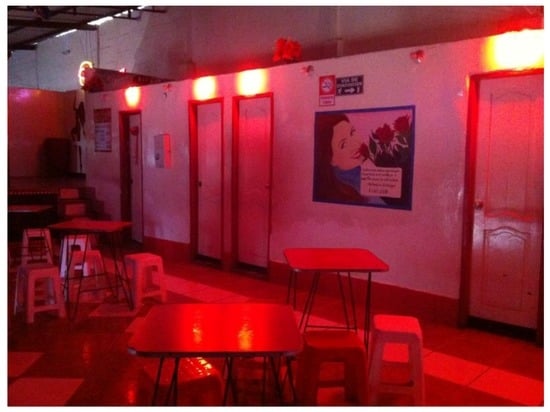

Figure 6.

Brothel Las Rosas in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Photo by author.

5.2.2. Street Work

Despite the relative greater security brothels can provide, some sex workers preferred working in the street. Teresa said she prefers the street because she earns more and gets to manage herself. In the club she used to work in, she had to be there from 10 am–8 pm, and if she left early, she wouldn’t receive her earnings. In the street she also has less competition. The club was crowded with over 50 women, and there were often drunk clients and fights. Alexandra, a Quito sex worker who had left nightclubs to work on Avenue Amazonas, said, “The difference [between brothels and the street] is that here in the street we don’t have a control, that nobody takes our money.”21 Claudia, another female sex worker on Amazonas who had previously worked in brothels, said that although the street is more dangerous, it’s better than brothels because in brothels you have to follow a set schedule, they exploit you, and you are obligated to drink. The ability to set one’s own hours was a drawing point of the street for many sex workers. Hours are especially important to the many sex workers who are mothers, “because they can set their schedules around their children’s needs” [34]. In choosing to work in the street, sex workers trade some of their safety for greater autonomy.

Other sex workers worked out of the street not because they preferred it, but because their identities made brothels inaccessible to them. Many older female sex workers were forced to work in the streets because of their age. Concepción, a 40-year-old woman in the Historic Center of Quito, used to work in a brothel on Avenue 24 de Mayo and preferred working there than on the street, because the conditions were “calmer” and the police sometimes “bother” street sex workers. She now works in the street because brothels will only hire young girls, she explained. Aurelia, a 55-year-old sex worker, would also prefer to be in a brothel because she thought it more secure, but said she can’t at her age because the girls in brothels are younger and have more plastic surgery. Transgender sex workers nearly all work in the street, because there are no brothels or clubs for transgender sex workers. The spaces sex workers use thus do not always reflect their personal preferences, but what spaces are available to them.

One of the negative experiences of working in the street was harassment and insults from passerby. Female sex workers like Teresa complained about people in the street insulting them with words like puta, whore. Trans sex workers experienced transphobic insults; Donna complained of being called maricón, fag.

Street sex workers also reported high levels of violence. Although not all sex workers in the streets had experienced violence, many more relayed stories of violence than those in brothels. Because street sex workers may go in a client’s car, where they have little control over the situation and little ability to escape, and the hotels where they service clients may not have the same kind of surveillance as a brothel, they are more vulnerable to client abuse. Clients sometimes beat, rob, or refuse to pay sex workers. Interview participants recounted that many sex workers have been found killed in hotel rooms or on the street. Rosa, a female sex worker in the Historic Center, told me that just two weeks previously a client had almost killed her, and the owner of the hotel rescued her. Britney, a female sex worker who worked at night on Avenue Amazonas in Quito, once had four men rape and beat her till she bled. Alexandra, another female sex worker on Amazonas, recounted several stories of client violence. Once, two clients tried to push her and her cousin off the second floor of a hotel for refusing to perform certain acts. Another client threatened her with a gun because he didn’t want to pay her, and she was forced to give him oral sex without a condom and then jump from his car to escape.

For trans sex workers, who must deal with transphobia in addition to stigma against sex work, violence is especially rampant. Cristina, a trans sex worker in Machala, told me she has lost many of her friends to “homophobic people”. Donna, a trans sex worker in the Historic Center of Quito, said a client once pulled a pistol on her; she managed to escape and tell the hotel owner, and he was sent to jail. According to Carolina Alvarado, the president of the Association of Trans Sex Workers of Quito (AsoTSTUIO), working on the streets at night is even worse than during the day. Although they get more clients, it’s cold, there’s more danger, and more “homophobes”. She too had experienced her share of violence; she once had a client hit her in the eye with his keys because he didn’t want to pay, and she has a cut on her hand from another client. Because sex workers and transgender people are both seen as deviant members of society, clients who commit violence against them face few to no consequences. María, a trans sex worker in Quito, said police are more likely to believe a client than a transgender sex worker. The less social capital sex workers possess, due to poverty, homelessness, age, or gender identity, for example, the greater their risk of violence.

Street sex workers in Ecuador, up until very recently, also faced high levels of police violence. Even though no law against street sex work exists, police frequently detained and abused street sex workers. In Quito, police often gassed sex workers to get them to move from the streets [34]. Sex workers in Quito also recalled the police would chase them in motorcycles, beat or rape them, insult them, force them to jump into the pond in Park La Carolina, and drop them far from the city and take their shoes or cell phones so they couldn’t get home. In Machala, Karina Bravo told me, police would arrest sex workers for being in the street more than ten minutes and drive them around the city in open trucks to humiliate them. Police especially abused transgender sex workers; trans sex worker María recalled police cutting transgender women’s hair (presumably as a method of removing their expressions of feminine identity).

However, sex workers developed modes of resistance against abuse and state attempts to limit their workspaces. During her research with street sex workers in the Historic Center of Quito from 2009–2013, Wilking [34] observed sex workers “actively subvert police control through creative strategies, often coordinated with other sex workers, to defy police orders and maximize their solicitation via covert opportunism” ([34], p. 11). The organization of sex workers played a key role in resisting state control. Bravo described how in 2004, her organization for street sex workers in Machala, Collective Flor de Azalea, exposed the police’s abuse. When police came to chase away a group of sex workers, Bravo and over 70 other sex workers refused to move, so the police took them to jail. In the police truck, they audio-recorded the police’s beatings and insults on their cell phones and then alerted a feminist organization, which threatened to file a report against the police. For the first time, sex workers had evidence of police mistreatment, resulting in an end to the high levels of police harassment in Machala.

In Quito, a legal counsel project by transgender rights organization Project Transgender, called the Legal Patrol, contributed to a decrease in police abuse of transgender sex workers by teaching sex workers about their constitutional rights and holding trainings with police [37]. Now, Ecuadorian sex workers generally express a better relationship with the police than before. Alexandra, a female street sex worker in Quito, said the improvement in police treatment came after sex worker leaders went to speak with President Rafael Correa in 2009, who subsequently said on TV that sex workers should not be detained [74]. “As soon as he said no, it ended,” she said. Although police treatment has greatly improved, however, some police still insult sex workers, explained multiple interviewees. While some sex workers felt comfortable seeking police help with a violent client, other still feared police. In their relatively successful organization against police control, however, sex workers asserted their rights to public space and maintained collective power over their workspaces. Their refusal to accede to police removing them from the streets, despite the violence they experienced as a consequence, demonstrates the value they place on the street.

Conflict over Space in the Historic Center of Quito

The conflict between the municipal government of Quito and street sex workers over the Historic Center of Quito, where I conducted 18 interviews, particularly demonstrates how sex workers relate to their workspaces and respond to policies regulating these spaces.

Historically, sex workers in the Historic Center worked both on the streets and in the houses of tolerance on Avenue 24 de Mayo (see Figure 7) [41]. Starting in 1999, however, the residents and businesses of the area began organizing against sex work businesses, for they disliked the presence of loud noise, alcohol, and the sex workers’ boyfriends or husbands, many of whom abuse the women and act as pimps [41]. The community’s organizing efforts led to the shutdown of the 15 houses of tolerance on Avenue 24 de Mayo, resulting in about 450 women being displaced to the streets between 2000 and 2001 [41].

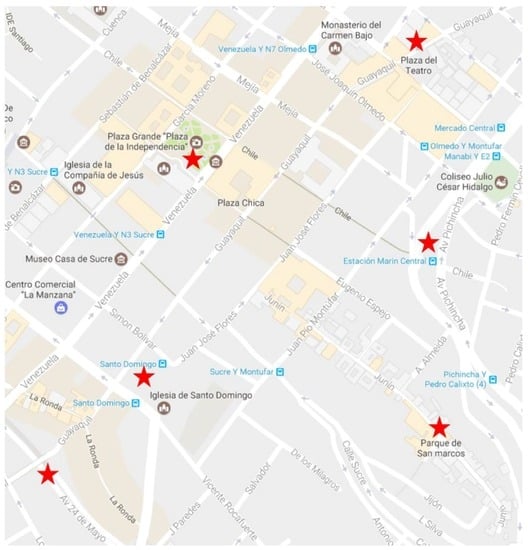

Figure 7.

Map of the Historic Center of Quito. Red stars indicate approximate locations where street-based sex workers concentrate, based on interview data and Álvarez and Sandoval [41]’s findings. Map from Google Maps.

To address the problem, the municipality of Quito relocated the sex workers in 2006 to the area La Cantera in the neighborhood of San Roque, where they permitted several brothels to operate [41]. Here, the organization of brothel sex workers ASOPRODEMU opened Danubio Azul, which ASOPRODEMU president Lourdes Torres claimed remains the only brothel outside the Netherlands operated entirely by sex workers. The municipality and sex workers alike originally viewed the project with optimism, hoping the relocation would provide increased safety and better working conditions. By the time of this study, however, nearly everyone who mentioned the project viewed it as a failure. The location is far from the center, high on a hill and difficult to get to, said Nelly Sánchez of the Quito Commission of Constructions. Further, the area is dangerous, with high levels of crime and risk of rocks falling [75,76]. As a result, most women have returned to the streets and plazas.

Other than La Cantera, Álvarez and Sandoval [41] identify four areas where sex work is concentrated in the Historic Center of Quito: Boulevard 24 de Mayo; the areas of Plaza Santo Domingo, San Marcos, and La Marín; Plaza del Teatro; and Plaza de la Independencia. According to Ecuadorian newspaper El Comercio, as of January 2016, there were 65 women working on Boulevard 24 de Mayo, 260 in the Plaza del Teatro, and 48 in Plaza de Santo Domingo [75].22 All my interviews in the Historic Center took place in the Plaza del Teatro. Three sex workers’ organizations operate in this area: the Association For a Better Future, the Association 1st of May, and the AsoTSTUIO. The three organizations have significant overlap, with many sex workers belonging to more than one.

At the time of interviews, the street sex workers were engaged in a struggle with the municipality of Quito over the use of public space. The municipality wanted to permanently relocate the sex workers from the streets and La Cantera to a government-constructed house of tolerance and were looking for a space near the Historic Center where they could construct the house. Dayana Morán, Director of Governance in the Secretariat of Security, said the house would provide a specific place for sex work to occur, with three floors, 60 rooms, security, a parking lot, an eating area, and green spaces. It would function only during the day, from morning to 6 pm, and would not have alcohol.

The municipality gave three reasons for this move. First, they said sex work must be moved from the streets to preserve “cultural patrimony” of the Historic Center. Because sex work is not illegal, nor is standing in the street, the municipality cannot prohibit street sex work. However, the city’s Ordinance 280 on the use of public space prohibits the issuance of permits for commercial activity to self-employed workers in the Historic Center and in “regenerated areas of the Zonal Administrations” because of Quito’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site [78]. Although sex work is not legally recognized as work, municipal officials interpret the ordinance as applying to street sex work and other informal vendors. Sara González of the Quito Secretariat of Social Inclusion explained the move is “not to exclude them from the Historic Center, but rather because by law…for the Historic Center to be considered a World Heritage Site, certain requirements must be preserved, and as the girls pass…they wear away the spaces” (emphasis hers). The city was concerned about the presence of sex work’s effect on tourism; the ex-Mayor of Quito, Paco Moncayo, told newspaper EL COMERCIO that the Historic Center “cannot be a big brothel or a big popular fair because the development of the city depends largely on tourism” [1]. No ordinance that specifically addresses sex work exists, and González favored the creation of such an ordinance, which could potentially allow sex workers to remain in the Historic Center.

Second, the municipality cited complaints about sex work from other residents of the area. Morán said the municipality received complaints from residents of the Historic Center about sex work in the streets. “…we have many complaints, many demands from inhabitants who are affected by the presence of sex work…because regrettably, often where there is sex work, there is crime…there are drugs, many, infinite things that collude with sex work,” she explained.23 The relocation into a house, she said, would allow sex workers to be an accepted part of society but in a specific place for them, where residents won’t complain that they are bad for their businesses. Quito wants to move towards a model similar to other countries that allow sex work only in specific streets or zones. “It’s not that we want to hide them,” said Morán. “We simply want to have one focus, sex work, in a single space.” Sánchez, too, favored the creation of a red-light district.

Third, the municipality believed the move would improve sex workers’ conditions. What we want most, Sánchez told me, is to improve their conditions and make their work more dignified. “[We want to] give the sex workers a place where all of them are and where they exercise their work without any problems, where neither the national nor the metropolitan police bother them, because it’s a specific place for them to exercise their work,” said Morán. González explained that many of the hotels street sex workers currently work out of have inadequate sanitary conditions, charge them extra for rooms, or don’t give them condoms or running water. She said the municipality wants sex workers to have a space with clean conditions and security.

The street sex worker organizations in the Historic Center, however, strongly opposed the move. Many sex workers emphasized the independence they exercised and freedom from a set schedule when explaining why they wanted to remain in the streets. Elizabeth Colobón, president of the Association 1st of May and vice president of For a Better Future, claims in a video called Sex Workers of Quito: Right to the street, “…our work is not meant to be enclosed, our work is free and democratic. We don’t have anyone who orders us, who manages us” [77].

Sex workers also worried about overpopulation and competition within the house. In the same video, Alexandra Flores asks, “What are we going to do in a space where there will be overpopulation of sex workers?...Here in the city of Quito come thousands of sex workers” [77]. Many said the move would harm older sex workers, who would be unable to compete with the younger sex workers in the brothel. Josefina, a female sex worker in the Plaza del Teatro, stated a house is for younger girls and asked what the older women would do. Teresa similarly questioned how the city could mix the older and younger women and predicted there would be fights between women over clients. When asked about this concern of the sex workers, Nelly Sánchez responded that such competition with younger workers exists in every type of work. “Sex work is that. Work. And in every type of work there is competition.” Transgender sex workers also rejected the move on the grounds that they have always worked in the street, not in an enclosed space. They worried they would be unable to compete with female sex workers in the same space, and that they might face violence if clients confused them with females only to find out in bed that they were trans.