Abstract

Norway is a world leader in gender equality according to sustainable development performance indicators. This study goes beyond these indicators to investigate systemic economic disadvantages for women, focusing specifically on the Norwegian pension system. System dynamics modeling is used to understand how gender disparity is built into social systems. A significant contributor to the gender inequality in pensions is the difference in lifetime working hours due to childbearing/rearing. There are childcare policies in place to equalize lifetime working hours between the genders; however, these policies require women to conform to the pension system structure and outsource their childcare. The system dynamics modeling illustrates how social investment strategy requires women to conform to a masculine pension system if they want equivalent financial security when they reach retirement.

1. Introduction

1.1. Norway, Gender, and Sustainable Development

Norway is considered a leader in gender equality and progressive in its commitment to sustainable development [1,2]. Social sustainability in particular is strongly supported with Norway’s implementation of social investment strategy in its welfare state policies. Many dimensions of social inequality are eased by policies that focus on early childhood education for example, which is a major pillar of social investment strategy. With this focus on early childhood education and other social investment policies, gender equality is often ranked high compared to other countries around the world [3]. It may be surprising that a study should focus on gender issues in a country that appears to be doing well according to most sustainable development performance indicators [4,5]. The point of departure for this study is to go beyond current performance indicators and investigate gender inequality in a way that data and indicators cannot. It must be mentioned that even though Norway ranks among the highest in the world for gender equality, Norway does recognize that more work needs to be done [4]. This study highlights a place to start.

1.2. Gender Disparities in the Norwegian Pension System

Men receive on average higher pensions than women in Norway. There are three main forces at work that make this so: wage inequality, lower salaries in female dominated professions, and more women in part time work than men. As wage disparity converges over time and as women are encouraged to enter male dominated professions (and vice versa), it can be too easily assumed that the difference in pension earnings will eventually disappear. This assumption simplifies how the pension system works operationally [6]. In addition to this, there are more elderly (67+) women than men in Norway, which increases the imperative to understand how this large demographic group experiences gender inequality systemically.

Within Norway, the pension system receives a lot of attention because of the aging population. The system is based on labor force participation, and when the rate of elderly population growth outpaces that of the working age population, funding problems are seen on the horizon. There are studies that have dynamically modeled the pension system in Norway, and these indicated economic sustainability given the changes in demography [7]. The social sustainability of the Norwegian pension system is another matter, and this is especially important for the pension system’s largest group of beneficiaries: women [6]. Lower pensions for women lead to a higher degree of social isolation and poor housing and health [8]. This study, through the use of system dynamics modeling, analyzes the structure of the Norwegian pension system, specifically highlighting how pension payments are determined for men and women.

There are several categories of pensions in Norway. This study investigates the public “Old Age Pension” (Alderspensjon), where pension payments are based on pension points. The Old Age Pension structure requires the accrual of pension points over 40 years of working life to receive maximum pension. There is also a minimum pension safety net to avoid elderly abject poverty. Pension points are earned through how much income a person has earned in their lifetime. In this way, the time in which the income is earned does not matter. This is a major difference from pension schemes in other countries such as the UK, for example [9]. Women on average start their careers later due in large part to longer educations and childbearing/rearing [10]. The time that a person invests in their pension account corresponds to large differences in pension payments even if accumulated lifetime incomes are equal. Norway avoids this problem because of the pension point system. The only factor that matters is total accumulated income, not when it was earned. It should also be noted that Norwegian pensions have been reformed in recent years, with the new regulations encouraging people to remain in the labor force for a longer time (although this does not affect the historical behavior investigated in this study). This reform was needed to make the pension system economically sustainable with an increasing elderly population and a decreasing juvenile population [7].

A recent report through the Nordic Council of Ministers [11] has indicated that part time work during childbearing/rearing years has no significant effect on state pension payments for women in the Nordic countries. However accurate their economic forecasting may be, this conclusion does not address the core gender issues in Nordic pension systems. In order to identify and analyze these issues, this study investigates gender disparities in the Norwegian pension system from the point of view of female labor force participation using system dynamics modeling.

Female labor force participation helps protect pension systems threatened by aging populations. Norway has, among developed nations, very generous childcare resources available to enable women to enter the workforce quickly after their parental leave. These childcare resources include nursery care after parental leave ends and before and after school care once the child is of school age. This can be argued as a very important policy for gender equality. It helps to raise a woman’s lifetime income to a level that gives women a pension closer to that of men. The purpose of this study is to analyze how this policy works operationally; examining how gender differences in pension develop over time, how this is related to accumulated lifetime income, and how childcare policies affect this. It is important to note that this study examines childcare policy in the form of pre-school daycare offered by the state after parental leave ends. Paid parental leave does not affect pension payments, and for this reason has been left out of this study.

It is very well-established in the literature that women are disadvantaged in many pension systems because of the wage gap, the salary gap between male/female-dominated professions and higher rates of female part time work. What is lacking in the literature is an investigation of the systemic forces that make this so. This study specifically addresses how policy operationally leads to this disadvantage, focusing on part time work. In addition to this, there is no dynamic modeling of gender and pensions in the literature, not just in Norway but in any country. Dynamic modeling has made few inroads into the evaluation of social policy, and part of the novelty of this study is the application of new methods to a well-established body of literature.

The first section of this paper provides a short background on the system dynamics methodology and feedback theory. System dynamics modeling is then used to examine the following research question: are there structural disadvantages for women in the Norwegian pension system? This is illustrated and explained through the use of a stock and flow diagram. Simulations of the stock and flow diagram, represented through graphs, are presented in the results section. A causal loop diagram is also presented with the results, and is used as the focal point for the discussion due to its simplicity. The discussion section explores how the Norwegian pension system structure, in light of social investment strategy, operationalizes a structural social and economic disadvantage for women. Appendix A provides additional information on the model, validation, and limitations.

2. Methods

System dynamics is a relatively new discipline that saw its formation in the mid-20th century and began to spread with the publication of Industrial Dynamics by Jay Forrester [12]. System dynamics is used when analyzing a domain as a system to understand the feedback within the system in order to develop solutions to inherent problems versus symptoms. The methodology was originally developed at MIT by a group dedicated to this academic pursuit [13] and engaged by the Club of Rome to create the World3 model, which has been a cornerstone of sustainability and climate change analysis [14]. System dynamics is an iterative, interdisciplinary process that views problems holistically. Essentially, using system dynamics involves identifying elements, subsystems, and the systems’ context, boundaries and properties of the system under investigation. System dynamics is both systematic and systemic in that there are systematic processes, and it is rooted in systemic thinking in order to recognize and solve complex problems by seeing the whole instead of only the parts [15]. System dynamics is often preferred over other analysis methods because of its underlying computational rigor—see Appendix A.

System dynamics is applied in this study to the Norwegian pension system in order to understand how elements in this system operate and interact. System dynamics modeling is aided by the use of software (this study uses iThink, see Appendix A). The elements in a system dynamics model consist of stocks, flows, and variables (stock and flow diagram). Stocks are an accumulation of its flows over time, and flows represent addition and subtraction to the stock over time. Variables in stock and flow models are elements that affect the inflows and outflows. The variables are linked to each other and flows through instantaneous causal links. The accumulated causal behavior in the stock is affected by the flows, which are in turn affected by the variables.

The structure of a system yields the behavior over time (accumulated in stocks), and the goal is to discover all the elements and relationships in a system and reproduce the observable reference mode behavior (actual system behavior). In system dynamics models, there are endogenous and exogenous elements. Endogenous elements are incorporated in the model structure in relation to other structural elements. Exogenous elements are variables that contain data that are directly imported into the model structure.

Feedback Theory

A fundamental concept in system dynamics is feedback theory. In the evaluation of the relationships between elements in a system, there are often feedback loops operating in a system [16]. A feedback loop is the interconnection of variables in a system that feeds back into itself. This is a closed loop system. Open loop systems do not have a feedback loop, and often the policy goal in these systems is to close the loop, especially in environmental management systems. Open loop systems have exogenous variables that influence the system structure from outside the system to generate the system behavior. Closed loop systems have endogenous variables, where the behavior is influenced by forces within the system. An example of this is climate change variables. When modeling societal collapse in history (e.g., the classic Mayans), climate change (drought) influenced societal collapse. Climate change is exogenous in this example because the population was not causing the drought. However, when modeling human-induced climate change in contemporary societies, climate change is endogenous because human activity influences climate change and climate change, in turn, affects human societies.

A causal loop diagram (CLD) of the stock and flow diagram shows the relationships between elements in a system (the feedback loop), which can be either positive or negative. A positive relationship means the elements develop in the same direction (when one increases, so does the other), and a negative relationship means the elements develop in opposite directions (when one increases, the other decreases). A balancing feedback loop means that the relationships between the elements keep the accumulated elements (stocks) at equilibrium. In addition to the balancing feedback loop, there is also a reinforcing feedback loop, where the behavior of the stock does not find an equilibrium and continues to increase or decrease over time.

One of the major goals of system dynamics is to understand the structure of the system that results in the observable behavior. This is the motivation for using system dynamics as the methodology for this study. The goal of this study is to understand how policy structure produces gender disparity in the pension system. Representing the pension system mathematically is an approach that serves to complement other methodological approaches. For more information about system dynamics modeling and its limitations, please see Appendix A.

3. Results

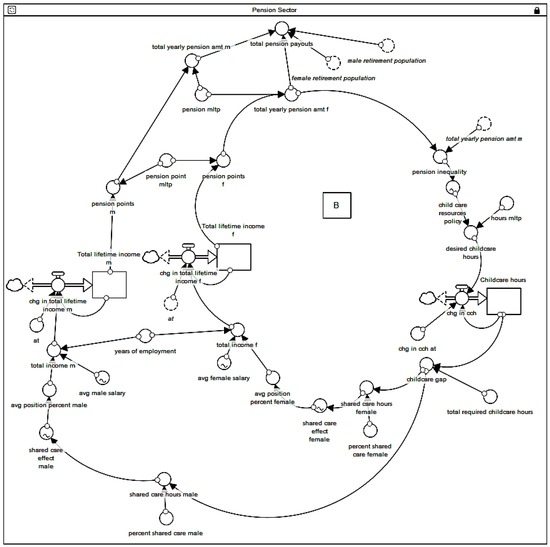

The model presented in Figure 1 is one part of a larger model. This section presents the stock and flow diagram of the Norwegian pension system (representing its structure). This is only a portion of the system however, and represents how income is accumulated over time (see Appendix A for an expanded description of the model). Total lifetime income is the largest determining factor of pension payments. There are policies in place to equalize the pension payments between men and women. The main structural policy is the provision of childcare resources (i.e., pre-school daycare).

Figure 1.

Stock and flow diagram of a section of the Norwegian pension system. The “B” shows the location of the balancing feedback loop, shown as a causal loop diagram (CLD) in the Results section. The boxes are stocks, and the flows are the large arrows going into and out of the stocks. Variables are the circles, and the small arrows connecting all the elements are the causal links. Each variable and flow represents either data or an equation. “avg” is a short form of average, and “chg” is the short form of change.

The stock and flow structure only represents childcare resources after parental leave ends. During parental leave, parents earn the same amount of pension points as they did before parental leave. The model only represents how women are enabled to enter the labor force after parental leave ends (the availability of childcare resources), and how this in turn affects income and pension. Only labor force participants who have worked 40 years (regardless of position percent/full time vs. part time) are represented in this model. This model assumes that the male position percent is not affected by child rearing, and this is recognized as a limitation of the model. Also, although this study only investigates pension transfers from the state, the pension system also includes a mandatory occupational pension. In addition to this, pensioners may have invested in private pension accounts to supplement their income at retirement. Therefore, the model does not represent total pension income, only total pension amount received from the state (in the Old Age Pension category).

The CLD of the system is presented in this section as well as the behavior (in the form of graphs) produced from the structure.

3.1. Stock and Flow Diagram of the Norwegian Pension System

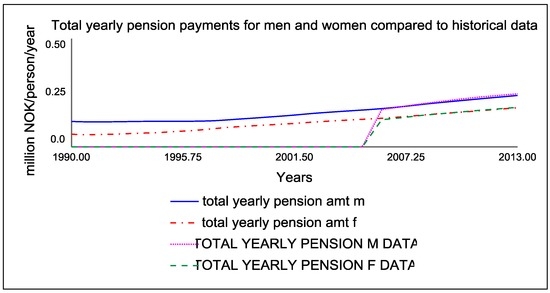

Figure 1 shows the stock and flow diagram of the section of the Norwegian pension system that represents how total lifetime income is accumulated for men and women. Total lifetime income for men is the stock on the left, and total lifetime income for women is the stock on the right. Total lifetime income is the largest determining factor for pension payments. Men and women earn different levels of pension as shown in Figure 2. Total yearly pension payments are simulated in the model in Figure 2 (blue-men and red-women) with the historical data (pink-men, green-women, no data before 2006).

Figure 2.

Total yearly pension payments for men (blue-simulation, pink-historical data) and women (red-simulation, green-historical data) in Million NOK/person/year.

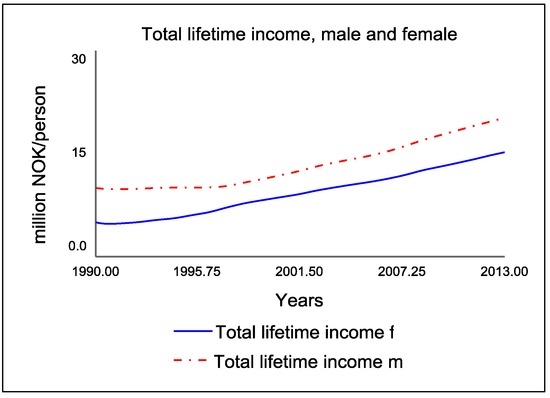

The total lifetime income for men and women (Figure 3) differs because of several factors. There is wage inequality between men and women, which is around 83%–87% female/male income, although this has been decreasing with time [10]. Another factor that affects the total lifetime income is the salary difference in male versus female dominated fields. Male dominated fields, such as engineering, have much higher salaries than typically female dominated fields, such as teaching [10]. Wage inequality and male/female dominated fields are factors that are aggregated in the variables “avg male salary” and “avg female salary” in the model.

Figure 3.

Total lifetime income for women (blue) and men (red) in Million NOK/person.

The purpose of this model is to investigate how state policies have worked to reduce pension inequality between men and women. As stated, there are policies to reduce wage inequality and goals to encourage women to enter male dominated fields. However, even if these inequalities disappear, the average position percent (full time position equals 100%) is still affected for women in childbearing/rearing years by a significant amount (ca. 20%). All else being equal, this large gap leads to major differences in pension, which is why the policies regarding this are investigated in this model.

Parental leave in Norway allows for men and women to stay home for 36 or 46 weeks after the birth of a child (number of weeks depends on whether they take 100% or 80% salary). Of these, the father must take 10 weeks of this, and the mother cannot take leave for the father [17]. Parents receive pension points during this time. By the age of one, the child has a right to a place in daycare [18]. This system allows for women (mothers are much more likely to be the parent taking the majority of parental leave) to be back at work as early as possible to start/resume earning income and pension points again.

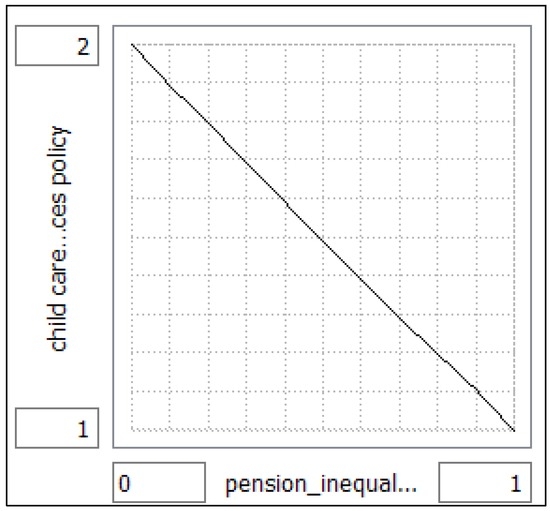

Women are most likely to work part time versus full time (represented as “position percent” in the model), and this is usually due to childbearing and rearing even with childcare resources in place. Norwegian childcare resources include income for women who stay home with children and do not hold a job, but these women do not receive pension points for this (and this income is not included in the model.) This tendency to work part time is represented in the stock and flow diagram in Figure 1. The “average position percent female” variable is affected by shared care hours. “Shared care hours” are the number of unpaid childcare hours parents must provide, which are not available to be outsourced to state childcare services. Either the mother or the father can provide unpaid childcare work, but this is (as a societal norm) usually provided by the mother. “Childcare resources policy” is a non-linear graphical function that states: as pension inequality increases, the childcare resources increase in availability in order to reduce pension inequality. This is a model assumption to represent policy decision-making. In short, policy makers will offer more childcare resources when pension inequality is higher. As pension inequality approaches 1, childcare resources increase by a decreasing percentage. In this sense, pension inequality between the genders is used as one performance indicator of gender inequality in general. The representation of this in the model does not mean that the only influence on childcare resources is pension inequality. Many variables not investigated in this model influence the level of childcare resources, which is a supply and demand dynamic referred to as the childcare gap [19]. Please see Appendix A concerning assumptions in system dynamics modeling.

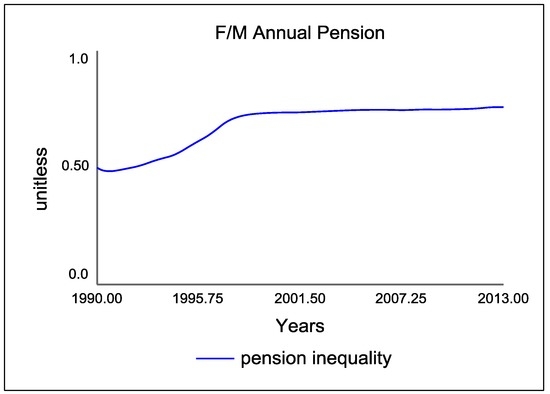

“Pension inequality” is the ratio between male and female pensions. The goal is to have this equal 1 (equal female/male pensions). The graph in Figure 4 shows the behavior of this over time. The simulation runs until 2013, with the ratio at 0.75.

Figure 4.

Pension inequality-the relationship between female and male pensions.

3.2. Causal Loop Diagram

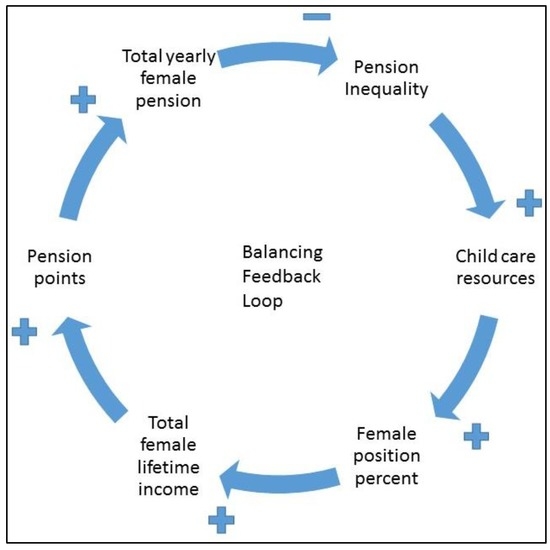

The relationship between the variables in the stock and flow diagram forms a balancing feedback loop, which is represented in the CLD in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Balancing feedback loop showing how the system reacts to gender inequality in pensions.

The CLD explains that as pension inequality increases, the amount of childcare resources increases. This increases the position percent (full versus part time work) that women are available to take. A higher position percent gives a higher total female lifetime income, which means more pension points for women. The more pension points women earn, the higher the pension they receive at retirement. As women receive higher pensions, pension inequality is reduced.

It seems from the CLD that the policy (childcare resources) in place helps to alleviate the pension inequality. As is often the case in policy implementation, as one problem is fixed, another arises. The next section discusses why this policy helps fix the problem, but with structural consequences for women.

4. Discussion

One important variable that is left out of the CLD is unpaid childcare work. The childcare policy relies on the importance of the dual earner household, but does not address the issue of shared caregiver, which is the other side of the dual earner relationship. This section explains how this structural oversight in policy leaves women disadvantaged.

There is a social dilemma with having children in Norway and most modern societies because of the large economic burden for the parents; yet children are valuable and necessary for the society [20]. Having children is not a rational economic choice for women, but it is rational as a societal choice. Norway has an interest in keeping the fertility rate from dropping and socially investing in children because the welfare system depends on labor force participation. Therefore, investing in the welfare of the young supports the welfare of the elderly in this model [18]. This is social investment strategy represented in the Norwegian pension system. However, the focus on children and childcare resources to increase female labor force participation (which increases the pension payment and hence female elderly welfare) keeps women locked into the balancing feedback loop shown in the CLD in Figure 5. Is this fair? It is not a rational economic choice (in terms of pension) for women to provide their own childcare versus having it provided by the state. I am not indicating that most women that use state provided childcare resources would rather stay home with their children (though some most likely would), but many do choose to stay home either full time or part time and are not rewarded (in terms of their pension) for their contribution to the social investment (as shown in Figure 2).

The “new gender contract,” advocated by Gøsta Esping-Andersen is the concept that welfare states should support a child-centered social investment strategy, where female labor force participation is necessary for the sustainability of the political economy [21]. Norway’s social welfare policy has focused on making this a reality, and women are needed in the labor force to do so, making gender equality both an economic issue and a social issue [22]. Increasing female labor force participation leads to what Esping-Andersen calls “female life course masculinization,” and men should hopefully adopt (and must in order for the new gender contract to work) a more “feminine life course” (higher rate of care duties at home). However, a more feminine life course for men is not easily achieved, and has as yet not been achieved to the level where childbearing/rearing does not affect female position percent (level of part time work). Although feminists are skeptical of the focus on children in social investment strategy having a positive outcome for women [23], this problem with the new gender contract and social investment strategy should instead call for the revival of the concept of husbandry [24]. Husbandry is a richer gender identity for men, where they identify beyond “the economic man.” Husbandry is not “a male mother;” and women need not become an “honorary man” or adhere to female life course masculinization. The argument in the revival of husbandry is that caring is a human trait, where men are leading less full lives without having it as part of their gender identity.

The CLD in Figure 5 indicates that women are at a structural disadvantage in terms of future pension payments. Only those women who want to contribute to the welfare system with labor force participation (and hence contributing to social investment strategy) will achieve higher pensions. Women must adhere to social investment strategy with labor force participation, where there is the defamilialization of care [23]; and if they choose not to adhere and provide childcare themselves, their lifetime earnings and hence pension will suffer. Even if women do adhere, care work at home is still largely the responsibility of mothers, which leads to higher rates of female part time work in childbearing/rearing years.

Regarding the recent report by the Nordic Council of Ministers [11] mentioned at the beginning of this paper, their assertion that part time work during childbearing/rearing years has no significant effect on the pension payment for women (using economic forecasting) is a very simplistic view of the systemic forces at work in the Norwegian pension system. Because of the methodological differences and points of departure between that study and the one presented in this paper, different elements of this issue are highlighted. The Nordic Council of Ministers research highlights that female part time work does not economically influence the level of pension compared to her full time counterpart (not a male/female comparison). This study identifies the systemic forces that make this so (and compares her to her male counterpart) and argues that these forces are what leads to the structural disadvantage for women in the Norwegian pension system. The two main systemic forces that lead to this disadvantage are the policy requirement of outsourcing childcare to enable female labor force participation (female life course masculinization) and the policy requirement of the shared caregiver (male life course feminization-which is a hopeful, not a strategic policy requirement). It is this policy that determines whether or not a woman’s pension payment equals or comes close to her full time counterpart, but it is the policy requirements that are the disadvantage for women.

Though not coming from a systemic perspective, Jensen [23], in an analysis of gender issues in social investment strategy, explains that structural factors (devaluation of women in the welfare system) must be attended to instead of worked around (male life course feminization). The structure of a system causes the behavior. Any realistic policy must address the structure to create real change [25]. As an extension of “female life course masculinization,” the Norwegian pension system is considered a “masculine pension system” because there is a requirement of labor force participation to receive pension points [26]. Women do not earn pension points for unpaid childcare work in the years after parental leave ends unless they are in paid employment. Women must “act like a man” and enter the labor force full time as soon as parental leave ends if they do not want to see a reduction in their pensions. However, there are only so many hours in the day, and women caught in this policy will never achieve maximum pension if men do not share childcare responsibilities. Because the policy relies on hope and not strategy to fulfill this shared caregiver requirement, in the evaluation of social investment strategy and its policies in regards to pension, the effect of solely focusing on children to enhance elderly welfare leaves women at a structural disadvantage.

This study does not model the Norwegian labor force and does not address the salary gap between male and female dominated professions, nor does it address the wage gap. This is important to address in relation to this study because labor force dynamics have a relationship with gender identity, as women are much more represented in care professions, and these are considered of lower value even when they are highly-skilled (such as nurses and teachers) [27].

5. Concluding Remarks

This study uses system dynamics modeling to explore how the Norwegian pension system in its implementation of social investment strategy traps women in a structurally disadvantaged situation. There is no attempt in this paper to give policy recommendations, as is so often the purpose of system dynamics modeling studies, because further research must be done before policy can be addressed. This includes, for example, analyzing the results in relation to various household structures (e.g., single men and women, couples without children, couples with many children versus one child). This study assumes equal pension levels for men and women as the desired system behavior, which corresponds to Norwegian equality goals, and further analysis must address several policy scenarios to achieve this. For example, if the male population contributes unpaid childcare hours and this achieves the desired behavior, what are the possible side effects of this and are the implementation challenges insurmountable? To be relevant for Norway, policy analysis must include a thorough evaluation of implementation challenges and feasibility. The model presented in this paper is the first system dynamics model that focuses on gender and pension in Norway. Labor force dynamics and childcare gap dynamics beyond pension are important future model developments that will give new insight into Norwegian gender issues.

Supplementary Materials

All model equations and data are available online at www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/6/1/22/s1.

Acknowledgments

In developing the ideas and reviewing early versions of this work, special thanks goes to Åsa Lundqvist and the Sino-Nordic Welfare Research Network (SNoW). Special thanks also go to Cecilia Haskins for her constructive feedback and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Model Building and Validation

*All model equations and data are available in the supporting material.

Appendix A.1. Notes on Model Building

The model in this study was built using iThink 10.1 from isee systems. The time horizon is 1990–2013. The year 1990 was chosen because of data availability and because the 1990s shows the start of the effect of childcare policy implementation. The year 2013 was chosen because this was the last common year data that was available for all variables in the model. The portion of the model shown in the paper is one part of a larger model. The total model includes dynamic demography modeling and state accounting modeling. The population model is broken up into four age cohorts (0–14, 14–49, 50–66, and 67+). Immigration also forms part of the demography model as a separate inflow into each age cohort corresponding to the percentage of immigrants belonging to each age group. The working age population (the sum of the 14–49 and 50–66 population stocks) is linked to state income, whereby labor force participation is calculated and then linked (with the unemployed removed) to the state income section of the model. The state income portion of the model has several elements. All income to the state that is connected to the labor force is disaggregated (e.g., pension contribution, income tax, employer fees and social security fees) and connected to the demography modeling. There is also an individual capital tax that is linked to the total population. All oil related income is disaggregated though not linked to any other part of the model.

The state income portion of the model also includes the Norwegian pension fund stock. Though not relevant to the discussion in this paper, the model has a reinforcing feedback loop involving the state general fund and the Norwegian pension fund. The general fund stock is a state accounting stock (state income minus expenditures). In Norway, this stock is always (in the model’s time horizon) positive. All surplus income is invested in the Norwegian pension fund. This stock has nothing do with the pension system and is the new name for the Norwegian Petroleum Fund. There are discretionary drawdowns on this interest-bearing fund where the maximum annual drawdown is 4%, though the fund consistently yields higher returns, thus creating the reinforcing loop in the Norwegian pension fund.

In the state expenditures portion of the model, only pension expenditures (named pension transfers in the model) are disaggregated, making two outflows from the general fund stock: pension transfers and other expenditures. Pension transfers are linked to the 67+ population stock, with males and females disaggregated. This population and the pension transfers are linked to the portion of the model discussed in this paper.

Appendix A.2. Notes on Data and Support for Variables and Relationships

The demography sector data was retrieved from Statistics Norway (SSB). The state accounting sector data was retrieved from the Norwegian National Budget (Statsbudsjettet), which is an online database of state budget information. The pension sector includes data from SSB and Statsbudsjettet, but several relationships assumptions are made. The most important relationship assumption is the childcare resources policy, which is explained in the paper (see Section 3.1). This variable was also subjected to a sensitivity analysis (see below). The other assumption was pension inequality, and how it is represented and why is also explained in the paper (see Section 3.1).

Appendix A.3. Notes on Validation

Validation of the model presented in this paper took several forms. On the most superficial level, face validity of the model architecture was achieved by presenting the model and paper with Nordic welfare state experts in the Sino-Nordic Welfare Research Network (SNoW).

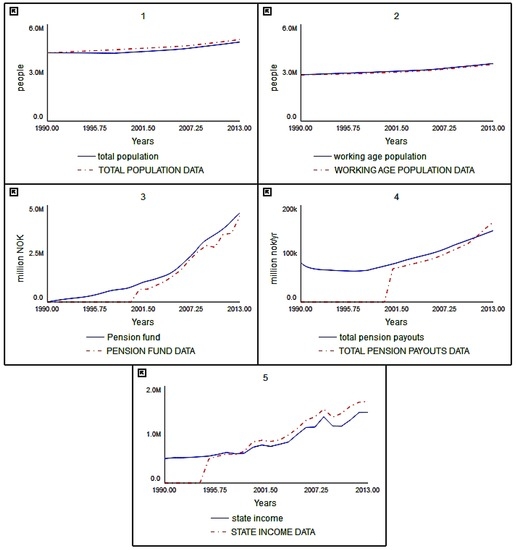

The model validation process involved comparing simulations to historical data. Model behavior is compared to several different sets of historical data (the reference modes). The main reference mode along with the simulated behavior is shown in Figure 2. Several reference modes were chosen in the population and state accounting systems to validate the model, including: population stocks (total Norwegian population and working age population), the Norwegian pension fund, annual pension transfers and annual state income. These simulations along with the historical data are shown below in Figure A1. It should be noted that in Graphs 4 and 5 in Figure A1, there are no available data before 2000 and 1995 respectively. The data variables are set to 0 in the graphs when no data is available in order to make the data gaps transparent.

Figure A1.

Other supporting reference modes used for validation. 1 = Total Norwegian population; 2 = Working age population; 3 = Norwegian pension fund; 4 = Pension transfers; 5 = State income. All simulations are in blue, and all historical data are in red.

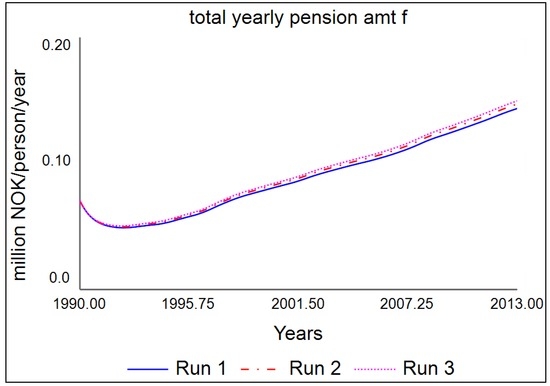

Appendix A.4. Sensitivity Analysis

The pension sector is dependent on an assumption in the variable “Childcare resources policy.” As stated in the paper, this is a non-linear graphical function that states as pension inequality increases, the childcare resources increase in availability in order to reduce pension inequality. This is a model assumption to represent policy decision-making. In short, policy makers will offer more childcare resources when pension inequality is higher. As pension inequality approaches 1, childcare resources increase by a decreasing percentage. In this sense, pension inequality between the genders is used a one performance indicator of gender inequality in general. The graphical function is shown in Figure A2.

Because the pension sector of the model is dependent on this assumption, a sensitivity analysis was needed. The results of the sensitivity analysis are shown in Figure A3. The effect of the childcare resources policy non-linear graphical function was reduced and increased by 25%, and results in Figure A3 show the effect on total yearly female pension payment. Run 1 is the reduction of 25%; Run 2 is the same as in the model simulation presented in the paper; and Run 3 is the increase of 25%. Total yearly female pension payment is the variable most affected by this assumption in the childcare resources policy, in addition to being the focus of the model, which is why it was chosen for the sensitivity analysis.

Figure A2.

Childcare resources policy variable: non-linear graphical function.

Figure A3.

Childcare resources policy sensitivity test and the effect on total female yearly pension payment.

Appendix A.5. Methodological Limitations

System dynamics modeling is not without its limitations. All forms of mathematical modeling are simplifications of reality. While models are still useful in their simple and abstract representation of actual system structure, this does limit their usefulness. Although there are validation tests that evaluate the robustness of the model, as in the sensitivity analysis shown in Appendix A.4, uncertainty is never fully resolved. System dynamics modeling can be taken as a very deterministic method, especially when uncertainty is not made transparent, and modelers must take extreme care of not assuming or influencing others to believe that the assumed causality represented in the model structure are actual causal relationships. System dynamics models are engineering tools, where system model design can be represented in nearly limitless ways. Just because one system design shows a certain outcome, this does not mean that a different model design of the same system will replicate that outcome.

This is of specific concern in a study of the type presented in this paper because of the limited application of system dynamics modeling in welfare state policy analysis. Models evolve over time, and the novelty of this study is that this is a first iteration model, meaning there are no published models on which the model in this study could be built. Because of this, there are issues regarding not only robustness, but also of model scope. The model boundaries are rather limiting in this model; salary and wage gaps are not represented endogenously, and this must be further developed in future iterations of the model. Childcare resources are only endogenously affected by pension inequality, and it would be very useful to extend the model boundaries to see dynamics between other influential variables. As models evolve over time, with many modelers of different backgrounds developing them, the robustness of the model is strengthened and the scope is widened, making the model outcome much more supported.

In addition to this, and related to robustness, is that one of the strengths of system dynamics modeling is also one of its weaknesses. System dynamics modeling is largely secondary analysis, but when there are literature gaps about system structure, system dynamics modeling has techniques to cope with this shortcoming. Graphical functions, e.g., the childcare resources graphical function presented in this paper, are able to approximate relationships between variables when there is a dearth of literature. System dynamics models are engineering models that do not attempt to make causal claims [28]. In doing so, literature justification gaps are supported by model validation. Although graphical functions are a useful technique, it must be used with caution and tested, with its limitations made transparent. In this model, this was done with the sensitivity analysis for the childcare resources non-linear graphical function. It is recognized that further model development is needed to strengthen the understanding of this system.

References

- World Economic Forum (WEF). “Global Gender Gap Report 2015.” Available online: http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2015/rankings/ (accessed on 21 October 2016).

- Regjeringen. “Norway’s Follow-Up of Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 5 July 2016. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/follow-up-sdg2/id2507259/ (accessed on 21 October 2016).

- The Economist. “The Best—and Worst—Places to Be a Working Woman.” Available online: http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2016/03/daily-chart-0?fsrc=scn%2Ffb%2Fte%2Fbl%2Fed%2Fthebestandworstplacestobeaworkingwoman (accessed on 31 July 2016).

- SSB. “Indicators of Sustainable Development, 2014 Sustainable Development-Future Challenges.” Statistisk sentralbyrå. 3 July 2014. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/artikler-og-publikasjoner/sustainable-development-future-challenges (accessed on 26 July 2016).

- Niels Schoenaker, Rutger Hoekstra, and Jan Pieter Smits. “Comparison of measurement systems for sustainable development at the national level.” Sustainable Development 23 (2015): 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Letizia Zanier, and Isabella Crespi. “Facing the Gender Gap in Aging: Italian Women’s Pension in the European Context.” Social Sciences 4 (2015): 1185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSB. “Mikrosimuleringsmodellen MOSART.” Statistisk sentralbyrå. 2010. Available online: http://ssb.no/forskning/beregningsmodeller/mikrosimuleringsmodellen-mosart (accessed on 5 September 2015).

- Jon Kvist. “A framework for social investment strategies: Integrating generational, life course and gender perspectives in the EU social investment strategy.” Comparative European Politics 14 (2014): 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liam Foster, and Jon Smetherham. “Gender and Pensions: An Analysis of Factors Affecting Women’s Private Pension Scheme Membership in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 25 (2013): 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SSB. “Women and Men in Norway: What the Figures Say.” Statistisk sentralbyrå. 2010. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/bld/rapporter/2010/cedaw_rapporten/annex_3.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2015).

- Alma Wennemo Lanninger, and Marianne Sundström. “Part-Time Work in the Nordic Region: Part-Time Work, Gender and Economic Distribution in the Nordic Countries.” Available online: http://jamda.ub.gu.se/bitstream/1/742/1/parttime2_nikk.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2015).

- Jay Wright Forrester. Industrial Dynamics. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Donella H. Meadows. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green: White River, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William Behrens W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. New York: Universe Books, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Cecilia Haskins. “Systems Engineering Analyzed, Synthesized, and Applied to Sustainable Industrial Park Development.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- David C. Lane. “Social theory and system dynamics practice.” European Journal of Operational Research 113 (1999): 501–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAV. “Fedrekvote (Pappaperm), Mødrekvote og Fellesperiode.” Nye Arbeids- og Velferdsetaten. 14 June 2016. Available online: https://www.nav.no/no/Person/Familie/Venter+du+barn/fedrekvote-pappaperm-mødrekvote-og-fellesperiode--347651 (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- Nicole Hennum. “Developing Child-Centered Social Policies: When Professionalism Takes Over.” Social Sciences 3 (2014): 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne Lise Ellingsæter, and Lars Gulbrandsen. “Closing the childcare gap: The interaction of childcare provision and mothers’ agency in Norway.” Journal of Social Policy 36 (2007): 649–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joakim Palme. “The Quest for Sustainable Social Policies in the EU: The Crisis and Beyond.” In What Future for Social Investment? Edited by Nathalie Morel, Bruno Palier and Joakim Palme. Stockholm: Institutet för framtidsstudier, 2009, pp. 177–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gøsta Esping-Andersen, Duncan Gallie, Anton Hemerijk, and John Myers. Why We Need a New Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Julie Steinkopf Rice. “Free Trade, Fair Trade and Gender Inequality in Less Developed Countries.” Sustainable Development 18 (2010): 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane Jenson. “Lost in Translation: The Social Investment Perspective and Gender Equality.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 16 (2009): 446–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julie A. Nelson. “Husbandry: A (feminist) reclamation of masculine responsibility for care.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40 (2016): 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donella Meadows. “Places to Intervene in a System.” Whole Earth 91 (1997): 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Raj Aggarwal, and John W. Goodell. “Political-economy of pension plans: Impact of institutions, gender, and culture.” Journal of Banking and Finance 37 (2013): 1860–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erika K. Palmer. “The Heavy Cost of Care: The Gender Gap in Norwegian Work.” In Paper presented at the ESPAnet Poland 2016 Conference, Social Investment and Development, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland, 24 September 2016.

- Erika K. Palmer. “Beyond Proximity: Consequentialist Ethics and System Dynamics.” Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, 2017. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).