1. Introduction

The discovery of oil and natural gas across the continent of Africa in recent years has renewed global interests in the continent’s economic significance. New discoveries of oil wealth in places such as Liberia, Uganda, and Kenya, among others, are great news for the African continent. As Alex Vines indicates, six of the top ten global discoveries of oil and gas in 2013 were made in Africa alone [

1]. Ghana has certainly not been left out of the oil wealth bonanza after a large quantity of crude oil was found in 2007 [

2,

3,

4]. While some have expressed optimism about the future prospects of these discoveries in terms of development purposes, others are concerned about the growing struggle for Africa’s oil and gas resources among some major countries. Frynas and Paulo have, for example, echoed this point when they argue that Africa might be witnessing a ‘New Scramble’ over its petroleum resources from major powers such as China and the United States [

5].

In addition to these concerns, scholarly interests on the phenomenon of the natural resource curse have re-emerged as well. Ghana has essentially been a part of the so-called natural resource curse debate since the country started earning revenues from oil sales. In contrast to the familiar cases of the resource curse phenomena in Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, as some have suggested, might escape the resource curse because of its advancing democratic institutions and good governance practices [

6,

7]. In other words, Ghana’s strong democratic institutions and governance practices are likely to help create a pathway of escape from the curse. For Kopinski and colleagues, Ghana’s readiness against the resource curse could be rooted in its stable political order, strong civil society, independent media, governance practices, and other political credentials [

8]. In fact, Gyimah-Boadi and Prempeh describe Ghana’s strong credentials as democratic dividends for the country [

6].

For others, Ghana might experience the resource curse if the oil wealth is not properly managed [

2]. This reasoning is grounded on the familiar cases of countries (e.g., Nigeria and Angola) with abundant natural resources that have experienced slow economic growth, with the exception of the outlier cases such as Norway and Botswana [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The key puzzle or question of interest is whether Ghana can escape the resource curse or not. Like other studies, the work by Kumah-Abiwu and his colleagues has underscored the significance of the strong institutions/good governance argument, but these scholars have also suggested the need for further scholarly works on oil sector governance [

13]. Obeng-Odoom’s authoritative review of the state of gas and oil research in Ghana [

14] has equally set a good scholarly tone for this article’s central argument. As one of the leading scholars on Ghana’s oil and gas sector, Obeng-Odoom provides wise counsel on the need to bolster the theoretical aspect of the fast growing studies on Ghana’s oil and gas sector [

14]. This article shares similar ideas and extends the scholarly and policy works on Ghana’s oil wealth, especially on oil sector governance with a strong theoretical grounding. It therefore focuses on the ongoing debate in terms of how Ghana can adopt policy options and best practices to help the country escape the so-called resource curse. In addition to the democratic governance thesis, oil sector governance appears to be gaining some attention of importance, but not to the level one would expect. The article, in essence, advances a conceptual idea of a dualistic governance approach to Ghana’s oil resources with two main objectives. First, the article makes the case for a scholarly/policy agenda shift toward the importance of oil sector governance. Second, the article argues for an integration or convergence of the two governance concepts (the democratic and the oil sector) in the broader discourse on how Ghana can escape the natural resource curse.

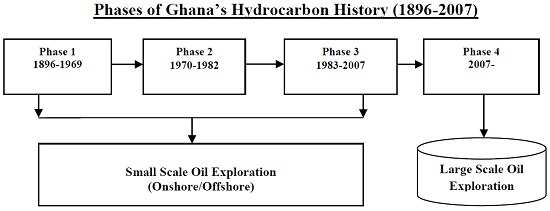

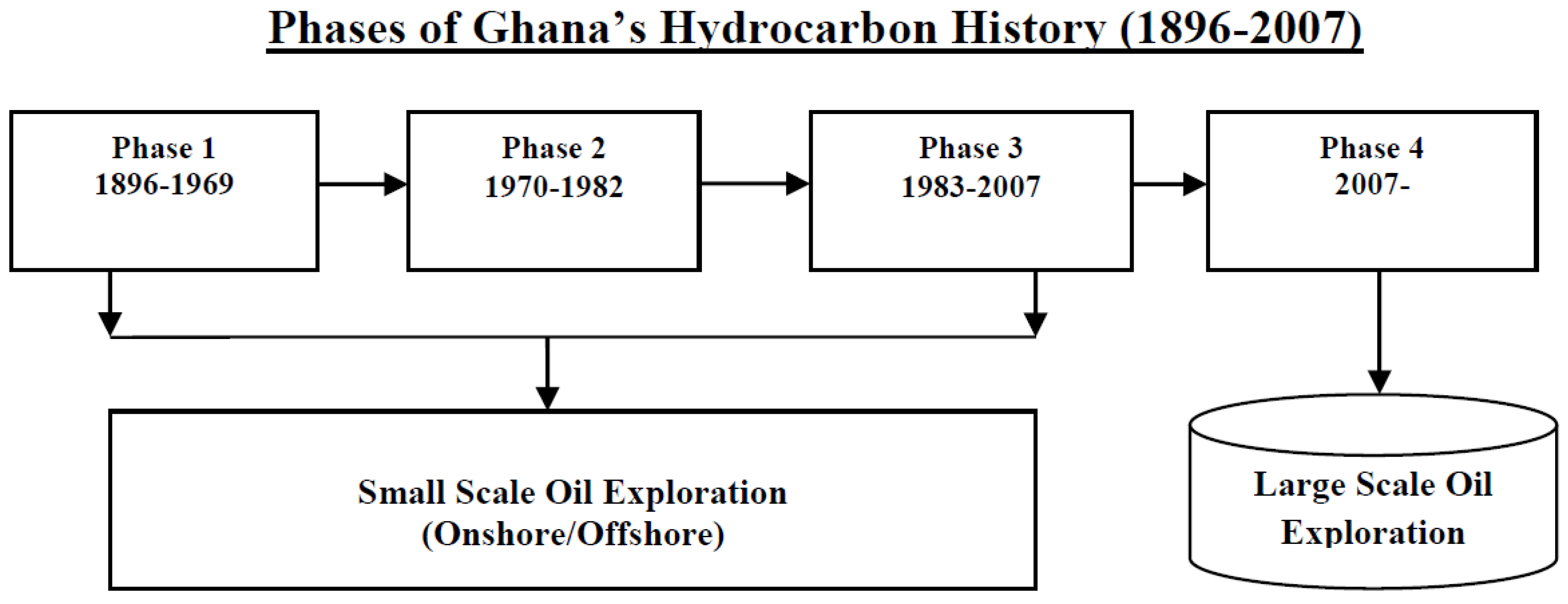

To explore these ideas, the paper draws on the resource curse and agenda setting theories for the analyses. The two main research questions to be explored are: first, to what extent can Ghana avoid the resource curse by integrating the two governance concepts (the democratic and the oil sector)? Second, how useful is agenda setting theory to the shift in the debate about oil sector governance? The article is structured into three parts in answering these questions. The first part provides a historical overview (phases) of Ghana’s oil industry. The second part examines elements of the resource curse theory and the debate on whether Ghana can escape the resource curse or not. The third part explores the dualistic governance approach or the two governance concepts (the democratic and the oil sector) and examines the usefulness of agenda setting theory to the broader discussions on oil sector governance. Policy recommendations have also been provided in the final part of the article.

2. Historical Phases of Ghana’s Oil Industry

Ghana secured a place among oil-producing countries when a large quantity of crude oil was discovered in 2007 and oil exportation started by December 2010 [

2]. The Jubilee field alone is reported to have 800 million barrels of oil reserves with potential reserves, which are likely to reach about 3 billion barrels ([

15], p. 1). As is the case with other oil-exporting countries, Ghana’s oil is expected to generate about US$20 billion in earnings from 2012 to 2030 ([

2], p. 3). While the commercial quantities of the recent oil discoveries have enhanced the country’s image as an emerging oil giant, it should be noted that Ghana’s history of hydrocarbon exploration began in small quantities dating back to the late 1890s. The Tano basin, for example, was among the first few places where onshore oil was discovered [

16]. To provide a clear understanding of the country’s hydrocarbon history, I categorize the evolutionary periods into four phases. The first phase (1896–1969) constitutes the starting point with the Tano basin discovery in 1896. A total of twenty-one shallow explorations took place between 1896 and 1957 [

16]. Although the exploratory activities were not in large quantities, the establishment of the Tema Oil Refinery (TOR), which was a strong component of former President Nkrumah’s development agenda in the 1960s [

17], constitutes a vital part of the first phase.

The second phase (1970–1982) of Ghana’s hydrocarbon history is not clearly distinct, but a critical observation from the 1970s reveals active attempts at offshore exploration. The Saltpond basin represents a significant milestone in this direction. This was followed by other exploratory activities in the Tano basin, Tano-Cape Three Points, the Volta Tano well, and the North Tano field [

16]. The third phase (1983–2007) of the hydrocarbon history is quite distinct in terms of the establishment of the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC) in 1983. With the aim of promoting the exploration, development, and production of petroleum resources, the GNPC distinguished itself as one of the pioneer agencies that prepared the way for the commercial discovery of oil in 2007 [

16]. The fourth phase is significant in terms of the huge change in exploration activities when a large quantity of crude oil was discovered in 2007 [

2,

18].

Figure 1 provides an illustrative display of the historical phases.

As the preceding discussion reveals, Ghana has been harnessing its petroleum resources for decades, but the 2007 discovery elevated the country’s position within the global oil terrain. As Ghana moves forward into its new space as an oil producer, scholars and policy makers are also reminded about the consequences of oil wealth and slow economic growth, often known as the natural resource curse phenomenon. Well-known countries such as Angola, Nigeria, Chad, and Venezuela [

17,

21] are good cases in point. No wonder, the question of whether Ghana can escape the resource curse or not has become the central point of the ongoing debate. If it can, as some have suggested, under what circumstances will this occur and why? If not, what might explain it? Simply put, will Ghana’s oil wealth help or hurt the country? This article will explore these important questions. Before then, it would be useful to first examine the conceptual elements of the resource curse phenomenon.

3. The Resource Curse Phenomenon

The question of why some countries with vast natural resources, such as oil, bauxite, and gold, tend to perform poorly in their economic growth in contrast to other countries which are less endowed with natural resources has been at the center of scholarly debates for several decades [

5,

10,

11,

22]. Scholars in the fields of economics, political science, and international development have been interested in exploring why countries such as Nigeria and Angola with vast natural reserves of oil and gas, for example, continue to experience poor economic performance. Except for the classic cases of Norway (oil) and Botswana (diamond), the literature is very clear about the slow economic performance and overall development in many resource-rich countries [

12,

23]. Leading empirical works [

9,

10,

23,

24] among many others have shown the connection between resource-rich countries and the resource curse phenomenon. The ‘Dutch disease’ is one of the noticeable signs of the resource curse. The disease occurs when economic resources shift from a competitive sector such as manufacturing, known for creating economic growth, to a newly booming sector of an economy, especially in the natural resource field [

10]. One of the consequences of the disease is the appreciation of a country’s currency relative to other currencies, which is often due to the windfall in government revenues from the booming sector of the economy [

7,

22,

25]. The volatility of global market prices of natural resources, especially oil and gas, is another manifestation of the curse phenomenon [

10]. As Clifford Krauss has recently observed, ‘the oil industry, with its history of booms and busts, is in its deepest downturn since the 1990s, if not earlier’ ([

26], p. 1). Countries in the global north and south have been affected, but new starters and weakened oil-producing countries such as Venezuela and Nigeria [

26] as well as Ghana have suffered low revenue inflows. The socio-economic and political impacts of fallen oil prices could be devastating with far-reaching implications for these countries.

Scholars have also identified rentier activities of states as another contributory factor to the resource curse. Rentier activities tend to occur when a resource abundant country earns large revenues to the point where lower taxes are imposed on citizens [

24,

25,

27]. As Ross argues, rentier activities have the potential to reduce the ability of citizens to effectively demand accountability from their governments because of the low taxation regime often put in place ([

24], p. 332). The consequences of citizens with less interest in demanding accountability from their governments could create incentives for authoritarian regimes, political corruption, and the abuse of human rights. In fact, Ross’ study has revealed similar findings, wherein countries with abundant natural resources, especially oil, have become more authoritarian with less appetite for democratic governance practices. Equatorial Guinea and Angola are good examples.

Given the trajectory of countries that have experienced the resource curse phenomenon, one wonders what the future direction of Ghana with its new oil wealth would look like. What is clear, and perhaps worrying, is the fact that the curse phenomenon is quite common across the African continent. What is unclear, however, is whether Ghana is likely to experience or escape the curse. For some, as previously noted, Ghana might escape the curse because of its strong democratic institutions and governance practices [

6,

7]. Indeed, this line of thinking is not in a vacuum, since the Norwegian example has been a celebrated case for other countries. But we also know that Ghana’s democratic history and practices differ from Norway, although both countries share some common democratic values. The idea that Ghana could successfully model the success story of Norway or what has become known as the democratic or good governance argument can also be problematic if overly emphasized. The fundamental question, as earlier articulated, is whether strong institutions and good governance practices are sufficient conditions for Ghana’s escape from the resource curse. This article argues otherwise by maintaining that democratic institutions and governance practices are essentially valuable, but these democratic fundamentals ought not to represent the end goal for Ghana, as the current debate seems to suggest. I argue that oil sector governance deserves equal attention and is of equal importance to democratic governance. Before examining the argument on the oil sector governance, the next few pages will discuss the strong institutions/good governance thesis and the resource curse phenomenon.

4. Governance Practices, Strong Institutions, and the Resource Curse

As the literature suggests, countries with rich oil wealth such as Nigeria, Angola, and Equatorial Guinea, as well as those gifted with mineral resources as the case with Sierra Leone and Congo, are rather poor in material wealth. Mehlum and colleagues got it right when they observe that, ‘resource booms often become a curse rather than a blessing’ for countries with rich natural resources ([

28], p. 1117). In effect, ‘being rich in natural resources is associated with being poor in material wealth’ as Mehlum and colleagues have very well articulated. While many resource-rich countries, especially those in the developing world, appear to fit the resource curse phenomenon; Norway and Botswana are two well-known outlier cases of the curse phenomenon [

11,

29].

In the case of Norway, for example, it is not only one of the largest oil and gas exporting countries in the world, but its economy continues to defy the expectations of the resource curse with a high growth rate [

30]. Botswana is also heavily dependent on natural resources, but its decades of high economic performance have been remarkable [

29]. For most scholars, strong institutions and good governance practices have been offered as key explanatory factors to the high economic growth of these countries [

28,

29,

30]. In fact, Holden captures the Norwegian success as one characterized by not only strong institutions and good governance, but the protection of property rights and high quality public bureaucracy [

30]. Thurber and colleagues describe the Norwegian example as an actual model (Norwegian Model), which could be useful for other countries for lesson drawing purposes [

31]. For these scholars, the Norwegian model is based on the principle of transparency in the management of oil resources. Botswana shares similar characteristics with the Norwegian case. In their study titled ‘An African Success Story: Botswana’, Acemoglu and colleagues observe that Botswana’s political stability with good governance practices, strong institutions, and sound policies are largely responsible for its high economic performance ([

11], pp. 2–3).

It is clear that the success story of Norway represents a good example for a newly oil rich country such as Ghana. But the critical question of whether Ghana can draw lessons from the Norwegian case in its attempt to escape the curse is still a subject of debate. For some observers, Ghana’s likely escape from the resource curse looks quite positive. In their analysis on the positive perspective, Gyimah-Boadi and Prempeh have argued that Ghana’s democratic dividends present the country with advantages during its oil discovery, as compared to the era when oil discoveries were made in countries such as Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria [

6]. Kopinski and colleagues share a similar view on Ghana’s future. For them, the democratic qualities could help withstand what they have described as ‘structural immunity’ to the natural resource curse ([

8], p. 582).

The democratic governance thesis has not only enhanced Ghana’s image vis-à-vis the curse debate, but the argument appears to have become the dominant discourse on the country’s so-called ‘democratic preparedness’ to escape the resource curse. In fact, the slogan that Ghana is not Nigeria, as often articulated [

6], underscores the hopefulness of some Ghanaians for the expected ‘blessing’ rather than the ‘curse’ from the oil wealth. There is no doubt, as revealed by the Norwegian case, that Ghana’s strong institutions and good governance practices could help the country escape the curse. However, this article is of the view that the democratic governance argument has been over-emphasized, as though it is the panacea to Ghana’s escape from the resource curse.

Apparently, the ‘over glorified governance argument’ raises a further issue that cannot be ignored at this point. That is, Ghana, as we know, is not new to depending on natural resources such as gold and bauxite as key sources of revenue in its current democratic dispensation. The important question worth asking is whether Ghana’s so-called democratic dividends have successfully created the space for the effective management of its other mineral resources, as is the case with gold and bauxite, since 1992? In other words, what was the country’s record in the management of its mineral resources during the current democratic dispensation before the 2007 oil discovery? Okpanachi and Andrews have some answers to offer. According to them, one should not be overly optimistic about Ghana’s escape from the resource curse due to the disappointing nature in which the existing mining and other natural resource sectors have been managed (i.e., policy, revenue/environmental issues) for the past several decades [

7].

It could be argued, in line with Okpanachi and Andrews’ reasoning, that Ghana’s inability to transform its economic growth from decades of dependence on mineral and other natural resources, especially in the current democratic dispensation [

7], raises further questions regarding the future prospects of the new oil wealth. For these scholars, as this article shares, Ghana’s strong institutions and governance practices constitute just a fragment or part of the larger puzzle for its future success. Consequently, Ghana’s democratic credentials, as this paper argues, are indeed valuable, but only to some extent. In other words, it is my contention that Ghana is not likely to escape the resource curse with an exclusive emphasis on strong institutions and democratic governance alone. What is needed is an agenda setting or scholarly/policy attention to Ghana’s natural resource (oil sector) governance.

6. Equilibrium of Governance: The Dualistic Governance Approach

As the name suggests, the conceptual idea of dualistic governance has two core elements of democratic governance and oil sector governance. The two concepts are essentially not new to the political economy literature on natural resources, but both concepts are often examined with unequal emphasis. Moreover, the natural resource literature is clear, as previously mentioned, about the significance of strong institutions and democratic practices to high economic growth. In view of the above conceptualization, one could endorse the idea that a stable democratic order with strong institutions provides a vital democratic architecture or what Kumah-Abiwu and his colleagues ([

13], p. 70) have described as the first level of desirable democratic structures necessary for rich-resource countries yearning to experience high economic growth rate. Ghana is, of course, not deficient of such democratic credentials, as revealed in our earlier discussion.

What is unclear is the extent to which Ghana’s strong institutions and governance structures may have helped in shaping the country’s management of other natural resources (e.g., gold) and the difference the current democratic credentials or political capital could make on the new oil wealth. Arguably, these empirical questions are unresolved and the attempt to find answers will continue to occupy scholars with interest in Ghana’s natural resources. For others, the good governance concept that has been promoted in developing countries for decades as if the concept itself creates high economic growth has been characterized by contradictions as well. It is imperative to note that major Western countries with control over international development agencies, such as the World Bank and other governmental donors, have been influential in promoting the good governance concept with little or no room for alternative ideas (e.g., African-centered) in the praxis of these governance principles. Many developing countries, including Ghana, were left with no choice but to implement the so-called good governance principles with many challenges in meeting some of the expectations.

Merilee Grindle’s groundbreaking study has enhanced our understanding of the difficulties faced by many developing countries in their implementation of the good governance agenda [

37]. According to Grindle, the good governance concept is not only ‘unrealistically long and growing longer’ with reference to the ‘must be done’ demands on developing countries, but the concept has been defined for several decades by Western-backed development agencies and sadly embraced by domestic reformers (national governments) ([

37], p. 526) with little room for modifications. In their efforts to promote the good governance idea for so-called development and poverty alleviation purposes, agencies such as the World Bank provided little direction on what Grindle describes as ‘what’s essential and what’s not, what should come first and what should follow, what can be achieved in the short term and what can only be achieved over the longer term, what is feasible and what is not’ ([

37], p. 526). The best approach, as Grindle suggests, is to redefine the notion of good governance to ‘good enough governance’. That is, ‘a condition of minimally acceptable government performance and civil society engagement that does not significantly hinder economic and political development…and one that accepts a more nuanced understanding of the evolution of institutions and government capabilities’ ([

37], p. 526).

Grindle’s study has indeed renewed the good governance debate in the global development community from two standpoints. First, the study has uncovered the problems associated with the governance concept that has been pushed on developing countries regardless of their political and cultural differences for decades. Second, the findings have also created the intellectual space for scholars, policy makers, and development practitioners to rethink the direction of what could be described as the ‘traditional notion’ of good governance. I applaud Grindle’s scholarly courage in exposing these problems. It is thus obvious that the concept of good governance has some problems that need modifications. In fact, Grindle’s novel idea of the good enough governance could become the alternative concept for developing countries.

While Grindle’s work has uncovered the difficulties associated with the traditional notion of good governance, as this paper shares, it is certainly not intended to diminish, let alone ignore, the importance of the broader ideas and principles of good governance. Core elements such as transparency, rule of law, public accountability, fairness, and anti-corruption measures are worthy principles for every country to pursue regardless of different political systems and socio-economic structures. In essence, the governance argument on Ghana’s likelihood of escaping the resource curse can be celebrated. At the same time, the fundamental or, better put, my alternative argument is simple; that is, any attempt to exclusively focus on the strong institutions/good governance logic as the only way for Ghana’s escape from the resource curse could be misleading. The idea of oil sector governance deserves important attention as well. This again explains my underlying argument for a shift in agenda to natural resource or oil sector governance on the debate on Ghana’s oil wealth. What then constitutes natural resource or oil sector governance?

Essentially, oil or petroleum sector governance is defined as a system in which decisions about the exploitation of a country’s oil and gas resources are made and implemented [

38]. Such a system is often characterized by governmental and/or non-governmental actors engaged in a country’s oil sector. For many oil sector observers, the governance idea in the natural resource sector, especially petroleum, emerged as a response to the mismanagement and corruption that have engulfed the sector in recent years. Failures of governance in the resource sector, as Lahn and colleagues have argued, can lead to adverse consequences for economic growth, social development, and larger political implications [

38]. On the contrary, a well-governed sector, as many scholars agree, is likely to increase wealth and sustainable development. For others, decisions on the exploitation and management of natural resources should conform to broader governance principles of clarity of goals, ability to execute them, accountability, transparency, responsibility, accuracy of information, and sustainable strategies to benefit future generations [

38]. On the part of Lockwood and others, resource governance should involve critical issues of legitimacy, inclusiveness, accountability, and adaptability, among other core governance principles [

39]. With respect to actors in oil sector governance, Lahn and colleagues [

38] have identified three key actors or stakeholders. They include:

The stakeholders are not only expected to perform their respective roles but also to serve as checks and balances on each other. For example, the people, through their representatives, delegate roles to government for policy making, while government, in turn, delegates responsibilities to companies involved in oil and gas explorations. Similarly, the government holds companies accountable for policy issues, as companies provide accurate information for regulatory purposes [

38].

These interactions, especially among the stakeholders may vary from country to country, but their overriding goal is often focused on oil sector governance [

38]. This overriding goal, as this paper suggests, could also involve the creation of a shared common narrative or national agenda, in which the natural resources are seen as belonging to the nation and its future generations. Steinar Holden captures this idea very well with the Norwegian experience. According to Holden, ‘the management of the petroleum resources reflect the view among Norwegian decision makers that the resources belong to the nation, and that the development should benefit the society as a whole, including future generations’ ([

30], p. 2). One wonders, in the case of Ghana, whether decision makers recognize that the oil resources belong to the nation and the gains should benefit society as a whole. In most cases, the political class is always quick to reassure the Ghanaian public that the oil wealth will benefit all, but the reality of these statements is yet to be noticed.

As the preceding discussion has revealed, oil sector governance is a desirable outcome that could benefit Ghana like other countries in Africa. In the meantime, the question of whether Ghana’s oil wealth can be translated into social development for the benefit of all seems to be a daunting one with no clear answers. There are other problems facing Ghana that could hinder strong oil sector governance that are worth noting at this point. For example, legal scholar Adimazoya observes that the ‘transparency-and accountability-enhancing laws’ ([

40], p. 149) that are needed for Ghanaians to demand information on the country’s natural resources appear not to reflect the growing changes in the sector, especially the petroleum sphere [

40]. On these legal challenges, Obeng-Odoom [

3] and Gary’s [

2] thoughts on the issue might help us to better understand the problem. For these scholars, the laws on Ghana’s petroleum sector were enacted during the era when petroleum was not produced in commercial quantities. Unfortunately, Ghanaian authorities seem to be slow in responding to the changing oil sector. Perhaps, the passage of the Mineral Development Fund (MDF) Bill, which is aimed at providing legal basis in the disbursement and management of government royalties [

41], will provide a good framework or, better put, a gateway for the passage of subsequent laws to enhance Ghana’s oil sector governance.

Ghana’s macro-economic challenges are of concern to achieving oil sector governance as well. As revealed in the earlier discussion, the question most people want answers to is whether Ghana’s democracy is capable of helping the country to escape the resource curse or not. In his article, ‘Can Ghana’s Democracy Save it from the Oil Curse?’, economist Robert Looney raises similar concerns. In his words, ‘Ghana entered its oil-producing phase with a strong civil society and government institutions firmly in place’ ([

42], p. 1). Looney adds that the country’s robust party system with a two-term limit on the presidency, independent media, freedom of speech and association, rule of law, and the peaceful transfer of political power have positioned the country for economic take off [

42]. The recent transfer of political power in January 2017 following the successful 2016 general elections represents another moment of progress for Ghana’s democracy. However, Ghana appears to be struggling to translate its democratic capital into high growth rates. For instance, the country’s economic outlook report, which was issued by the African Development Bank, indicates a decrease in macro-economic growth (for the fourth consecutive year) to an estimated 3.9 percent growth in 2015. The growth projection is about 6 percent for 2016, but the prevailing energy crisis, public debt problems, and other fiscal imbalances [

43], particularly in an election year (2016), could negatively affect this economic projection. For Looney, as other scholars have argued, Ghana’s notorious out of control spending in almost every election year is another problematic trend because of the effects on the country’s high budget deficits [

42].

Another issue of concern is whether Ghana is actually earning its rightful oil revenues. In other words, the key question is how much is Ghana really earning from its oil? Panford’s study has not only raised this revenue issue for debate, but it also provides some explanations for what he describes as Ghana’s anemic oil and gas revenue flows since 2010 [

44]. According to Panford, as reported by other outlets, Ghana’s two full years (2010 to 2012) of ‘oil production did not yield the projected revenue of US$1.3 billion per annum, even when petroleum was being sold for around US$100 per barrel on the world market ([

44], p. 84). Falling global oil prices have even worsened the revenue problem in recent years. As a leading scholar on Ghana’s petroleum resources, one cannot but take Panford’s scholarly lamentation on Ghana’s inability to fully benefit from its oil revenues seriously. Among other factors, Panford’s analysis of technical and operational problems and the business practice of thin capitalization are useful points in our attempt to better understand the revenue challenge [

44].

Corruption is yet another issue of concern in achieving strong oil sector governance. Ghana’s 2015 perception index reported by Transparency International indicates a score level of 47/100 (scores range from 0 as highly corrupt to 100 as very clean). This score shows that the perception of public corruption is still a problem for the country. A few encouraging steps have, however, been taken and must be recognized. For instance, the creation of the Ghana Extractive Industries Initiative (GHEITI), which is part of the global Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), is commendable. The Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC) is another positive step toward broader transparency initiatives [

8,

45].

Two interesting scenarios about Ghana’s democratic order and good governance practices can be inferred from the foregoing analysis. First, the country’s democratic order, as this article observes, is at work in avoiding political decay as compared to other countries in the West African sub-region. Second, while Ghana’s democratic state must be well-guarded and preserved, it is unclear why the country’s democratic credentials have been slow in creating the impetus for high economic performance. While this article would not discount other explanations, it is still the article’s central contention, as earlier argued, that the attention of importance in promoting oil sector governance appears to be lacking critical public/scholarly discourse, as compared to the emphasis on democratic governance. As Robert Looney has reminded us, it is particularly important to keep the question on whether Ghana’s democracy can save it from the oil curse [

42] active on the national discourse or agenda.

This article argues, in view of the above, that the democratic governance concept should be integrated with oil sector governance and both should be given the same attention of importance on how Ghana can escape the resource curse. This is where the dualistic governance concept becomes useful in enriching the scholarly debate on Ghana’s oil resources. In this case, I suggest the need for emphasis on oil sector governance as is the case with democratic governance. A good place for setting the agenda for oil sector governance could be with public and private sector institutions engaged in Ghana’s oil exploration. Further discussions and policy initiatives on both governance concepts (the democratic and the oil sector) should follow up in order to attain the equilibrium of importance as Ghana move forward with efforts to escape the resource curse. Critical scholarly engagement in terms of research and publication on oil sector governance must be supported and funded at various levels, especially in our local universities and other institutions of higher learning [

44]. The edited volume by Kwaku Appiah Edu on governance of the petroleum sector [

46] represents another valuable addition to the growing works on Ghana’s oil sector governance.

As Thurber and colleagues [

31] have rightly reminded us, Norway represents one of the good examples of a country that has successfully integrated both governance principles (the democratic and the oil sector) in escaping the curse. It is important for Ghana to draw lessons from the Norwegian experience toward its attempt to escape the resource curse. Recruiting highly skilled (managerial and technical) Ghanaians in the oil sector is another challenge [

4,

44] that needs further focus and attention. It is critically essential that Ghana’s energy policy should include expatriate knowledge transfer as part of the broader policy goals and initiatives on oil sector governance [

44]. It is also recommended that policies be initiated in diversifying revenue sources of the economy in order to mitigate the volatility of global oil prices, as scholars have suggested. Collaborative efforts between the energy sector and Ghana’s main universities and polytechnics, as Panford has very well articulated, should be given top priority as well [

44].