Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. STEM-Related Federal Agencies

2.2. Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Variable Operationalization

3.2. Controls

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Percent LGBT | Percent Women | Percent Racial/Ethnic Minorities | Mean, Tenure Measure | Mean, Age Cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRC | 2.8% | 36.8% | 30.5% | 2.19 | 2.45 |

| EPA | 5.0% | 54.7% | 29.2% | 2.47 | 2.47 |

| DOE | 2.7% | 39.7% | 22.8% | 2.25 | 2.46 |

| NSF | 4.2% | 64.5% | 34.6% | 2.34 | 2.58 |

| NASA | 2.2% | 36.8% | 24.3% | 2.47 | 2.46 |

| DOT | 2.7% | 32.0% | 29.7% | 2.29 | 2.56 |

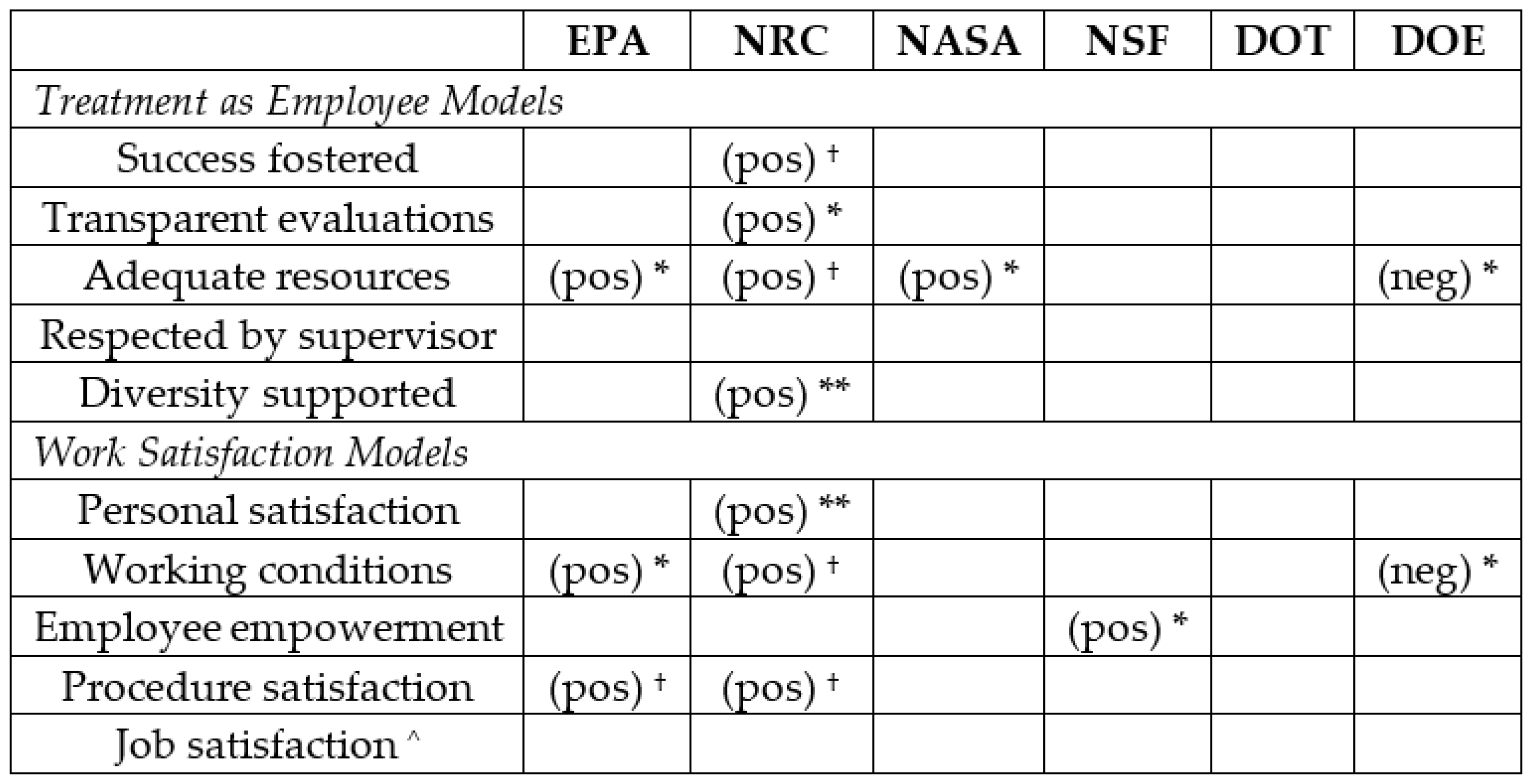

| EPA * LGBT Coef. | NRC * LGBT Coef. | NASA * LGBT Coef. | NSF * LGBT Coef. | DOT * LGBT Coef. | DOE * LGBT Coef. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (SE, p-Value) | (SE, p-Value) | (SE, p-Value) | (SE, p-Value) | (SE, p-Value) | (SE, p-Value) | |

| Treatment as Employee Models | ||||||

| Success fostered | 0.127 (0.089, p = 0.155) | 0.143 † (0.084, p = 0.090) | 0.095 (0.068, p = 0.164) | 0.094 (0.145, p = 0.517) | −0.067 (0.092, p = 0.466) | −0.088 (0.081, p = 0.278) |

| Transparent evaluations | 0.074 (0.083, p = 0.373) | 0.178 * (0.089, p = 0.046) | 0.048 (0.067, p = 471) | 0.054 (0.127, p = 0.669) | −0.066 (0.089, p = 0.461) | −0.022 (0.075, p = 0.770) |

| Adequate resources | 0.192 * (0.084, p = 0.023) | 0.174 † (0.102, p = 0.090) | 0.169 * (0.069, p = 0.014) | 0.053 (0.154, p = 0.730) | −0.096 (0.091, p = 0.295) | −0.154 * (0.074, p = 0.038) |

| Respected by supervisor | 0.059 (0.082, p = 0.475) | 0.119 (0.078, p = 0.127) | 0.026 (0.066, p = 0.695) | −0.033 (0.127, p = 0.795) | −0.065 (0.093, p = 0.483) | 0.037 (0.075, p = 0.616) |

| Diversity supported | 0.141 (0.101, p = 0.161) | 0.255 ** (0.089, p = 0.004) | 0.076 (0.095, p = 0.369) | 0.108 (0.144, p = 0.453) | −0.128 (0.131, p = 0.330) | −0.036 (0.092, p = 0.698) |

| Work Satisfaction Models | ||||||

| Personal satisfaction | 0.084 (0.124, p = 0.497) | 0.330 ** (0.119, p = 0.006) | 0.023 (0.104, p = 0.821) | 0.137 (0.181, p = 0.446) | −0.032 (0.148, p = 0.827) | −0.098 (0.109, p = 0.369) |

| Working conditions | 0.152 * (0.068, p = 0.026) | 0.115 † (0.066, p = 0.081) | 0.009 (0.061, p = 0.883) | 0.087 (0.099, p = 0.378) | −0.056 (0.093, p = 0.551) | −0.144 * (0.071, p = 0.041) |

| Employee empowerment | 0.114 (0.088, p = 0.196) | 0.143 (0.100, p = 0.153) | 0.101 (0.070, p = 0.151) | 0.292 * (0.131, p = 0.025) | −0.061 (0.093, p = 0.514) | −0.097 (0.081, p = 0.233) |

| Procedure satisfaction | 0.174 † (0.092, p = 0.058) | 0.170 † (0.093, p = 0.068) | 0.076 (0.073, p = 0.302) | 0.205 (0.128, p = 0.109) | −0.099 (0.103, p = 0.333) | −0.065 (0.081, p = 0.420) |

| Job satisfaction ^ | 0.074 (0.106, p = 0.485) | 0.080 (0.116, p = 0.492) | 0.110 (0.084, p = 0.192) | 0.093 (0.162, p = 0.564) | −0.047 (0.119, p = 0.695) | −0.065 (0.097, p = 0.502) |

References

- Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. Beyond Bias and Barriers: Fulfilling the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering. Washington: National Academies Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences. Expanding Underrepresented Minority Participation: America’s Science and Technology Talent at the Crossroads. Washington: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. Cech, Anneke Metz, and Jessi L. Smith. “Epistemological Dominance and Social Inequality: Experiences of Native American Science, Engineering, and Health Students.” Science, Technology & Human Values, 2017. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. Cech. “Engineers & Engineeresses? Self-Conceptions and the Gendered Development of Professional Identities.” Sociological Perspectives 58 (2015): 56–77. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Xie, and Kimberlee Shauman. Women in Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maya A. Beasley. Opting Out: Losing the Potential of America’s Young Black Elite. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Heather Dryburgh. “Work Hard, Play Hard: Women and Professionalization in Engineering—Adapting to the Culture.” Gender & Society 13 (1999): 664–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaine Seymour, and Nancy M. Hewitt. Talking About Leaving: Why Undergraduates Leave the Sciences. Boulder: Westview Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. Cech. “Ideological Wage Gaps? The Technical/Social Dualism and the Gender Wage Gap in Engineering.” Social Forces 91 (2013): 1147–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judith S. McIlwee, and J. Gregg Robinson. Women in Engineering: Gender, Power, and Workplace Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Robert William Connell. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mimi Schippers. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony.” Theory and Society 36 (2007): 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheri J. Pascoe. Dude, You’re a Fag: Masculinity and Sexuality in High School. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Judith Butler. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kristen Schilt. Just One of the Guys?: Transgender Men and the Persistence of Gender Inequality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. Cech. “LGBT Professionals’ Workplace Experiences in STEM-Related Federal Agencies.” In Proceedings of the 2015 American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) National Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 23–26 June 2015.

- Diana Bilimoria, and Abigail J. Stewart. “‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’: The academic climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender faculty in science and engineering.” NWSA Journal 21 (2009): 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Eric V. Patridge, Ramon S. Barthelemy, and Susan R. Rankin. “Factors impacting the academic climate for LGBQ STEM faculty.” Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering 20 (2014): 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin A. Cech, and Tom J. Waidzunas. “Navigating the Heteronormativity of Engineering: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Students.” Engineering Studies 3 (2011): 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon Traweek. Beamtimes and Lifetimes: The World of High Energy Physicists. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Julie Des Jardins. The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. New York: The Feminist Press at City University of New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory M. Herek. “Confronting Sexual Stigma and Prejudice: Theory and Practice.” Journal of Social Issues 63 (2007): 905–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrys Ingraham. White Weddings: Romancing Heterosexuality in Popular Culture. New York: Routledge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Laurel Smith-Doerr. Women’s Work: Gender Equality vs. Hierarchy in the Life Sciences. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- William T. Bielby. “Minimizing workplace bias.” Contemporary Sociology 29 (2000): 120–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevin Stainback, Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, and Sheryl Skaggs. “Organizational Approaches to Inequality: Inertia, Relative Power, and Environments.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (2010): 225–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald Tomaskovic-Devey. Gender & Racial Inequality at Work: The Sources and Consequences of Job Segregation. Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Julie Dolan. “Gender Equity: Illusion or Reality for Women in the Federal Executive Service? ” Public Administration Review 64 (2004): 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Accountability Office. Women’s Pay: Gender Pay Gap in the Federal Workforce Narrows as Differences in Occupation, Education, and Experience Diminish; Report to Congressional Requesters GAO-09-27; Washington: Government Accountability Office, 2009.

- Sean Waite, and Nicole Denier. “Gay Pay for Straight Work: Mechanisms Generating Disadvantage.” Gender and Society 29 (2015): 561–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendy Faulkner. “Dualism, Hierarchies and Gender in Engineering.” Social Studies of Science 30 (2000): 759–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin A. Cech, and William R. Rothwell. “Workplace Experience Inequalities among LGBT Federal Employees.” Working Paper, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cathryn Johnson, Barry Markovsky, Michael Lovaglia, and Karen Heimer. “Sexual orientation as a diffuse status characteristic: Implications for small group interaction.” Advances in Group Processes 12 (1995): 115–37. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. “Maps of State Laws & Policies.” Available online: http://www.hrc.org/state_maps (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- András Tilcsik. “Pride and Prejudice: Employment Discrimination against Openly Gay Men in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (2011): 586–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doris Weichselbaumer. “Sexual Orientation Discrimination in Hiring.” Labour Economics 10 (2003): 629–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. V. Badgett, Holning Lau, Brad Sears, and Deborah Ho. Bias in the Workplace: Consistent Evidence of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- G. Reza Arabsheibani, Alan Marin, and Jonathan Wadsworth. “3 Variations in gay pay in the USA and in the UK.” Sexual Orientation Discrimination: An International Perspective 4 (2007): 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Erin A. Cech. “The Veiling of Queerness: Depoliticization and the Experiences of LGBT Engineers.” In Proceedings of the 2013 American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) National Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 June 2013.

- Kristin L. Gunckel. “Queering Science for All: Probing Queer Theory in Science Education.” JCT (Online) 25 (2009): 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Donna M. Riley. “LGBT-Friendly Workplaces in Engineering.” Leadership Management Engineering 8 (2008): 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith C. Clarke, and Jeffrey J. Hemphill. “The Santa Barbara Oil Spill: A Retrospective.” In Paper presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 12–15 September 2001.

- PBS American Experience. “Timeline: The Modern Environmental Movement.” Available online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/timeline/earthdays/ (accessed on 22 August 2016).

- EPA. “Introduction: Environmental Enforcement and Compliance. ” Available online: https://www3.epa.gov/region9/enforcement/intro.html (accessed on 9 August 2016).

- Scientific American. “Environmental Enforcer: How Effective Has the EPA Been in Its First 40 Years? ” Scientific American. 2010. Available online: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-epa-first-40-years/ (accessed on 23 August 2016).

- Masao Omichi. “Nuclear power in the United States and Japan.” In US-Japan Relations: Learning from Competition. Edited by Richard B. Finn. Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- James R. Temples. “The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Politics of Regulatory Reform: Since Three Mile Island.” Public Administration Review 42 (1982): 355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John E. Chubb. Interest Groups and the Bureaucracy: The Politics of Energy. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Dickson. “Farewell ERDA, Hello Energy Department.” 2 October 2012. Available online: http://energy.gov/articles/farewell-erda-hello-energy-department (accessed on 30 August 2016)). [Google Scholar]

- Energy.gov. Office of Management. “A Brief History of the Department of Energy. ” Available online: http://energy.gov/management/office-management/operational-management/history/brief-history-department-energy (accessed on 25 August 2016).

- Terrence R. Fehner, and Jack M. Hall. Department of Energy 1977–1994: A Summary History; Washington: Department of Energy, 1994.

- David J. Bardin. “The Role of the New Department of Energy.” Natural Resources Lawyer 10 (1978): 633–38. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Energy. “Factsheet of the Department of Energy. ” Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/factsheet_department_energy (accessed on 25 August 2016).

- The Birth of NASA. “Why We Explore. ” Available online: http://www.nasa.gov/exploration/whyweexplore/Why_We_29.html (accessed on 9 August 2016).

- Rita G. Koman. “Man on the Moon: The U.S. Space Program as a Cold War Maneuver.” OAH Magazine of History 8 (1994): 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA. “NASA History in Brief. ” Available online: http://history.nasa.gov/brief.html (accessed on 12 August 2016).

- John M. Logsdon. “Space in the Post-Cold War Environment.” In Societal Impact of Spaceflight; Edited by Steven J. Dick and Roger Launius. Washington: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NSF. “About the National Science Foundation. ” Available online: http://www.nsf.gov/about/ (accessed on 14 August 2016).

- Heather B. Gonzalez. “The National Science Foundation: Background and Selected Policy Issues Specialist in Science and Technology Policy.” Congressional Research Service. 2014. Available online: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R43585.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2016).

- Daniel Lee Kleinman. “Layers of Interests, Layers of Influence: Business and the Genesis of the National Science Foundation.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 19 (1994): 259–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSF. “Science and Engineering Indicators 2014. ” Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind14/ (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- John L. Hazard. “The Institutionalization of Transportation Policy: Two Decades of DOT.” Transportation Journal 26 (1986): 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Richard W. Barsness. “The Department of Transportation: Concept and Structure.” The Western Political Quarterly 23 (1970): 500–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transportation.gov. “Creation of Department of Transportation—Summary. ” Available online: https://www.transportation.gov/50/creation-department-transportation-summary (accessed on 16 August 2016).

- Belle Rose Ragins. “Disclosure Disconnects: Antecedents and Consequences of Disclosing Invisible Stigmas Across Life Domains.” Academy of Management Review 33 (2008): 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle Rose Ragins, and John M. Cornwell. “Pink Triangles: Antecedents and Consequences of Perceived Workplace Discrimination against Gay and Lesbian Employees.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (2001): 1244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annette Friskopp, and Sharon Silverstein. Straight Jobs, Gay Lives: Gay and Lesbian Professionals, the Harvard Business School, and the American Workplace. New York: Scribner, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. “Deepening Divide between Republicans and Democrats over Business Regulation.” 14 August 2012. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/daily-number/deepening-divide-between-republicans-and-democrats-over-business-regulation (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Eric Keller, and Nathan J. Kelly. “Partisan Politics, Financial Deregulation, and the New Gilded Age.” Political Research Quarterly 68 (2015): 428–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. “Section 2: Views of Government Regulation.” 23 February 2012. Available online: http://www.people-press.org/2012/02/23/section-2-views-of-government-regulation (accessed on 18 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Gary R. Hicks, and Tien-Tsung Lee. “Public Attitudes toward Gays and Lesbians: Trends and Predictors.” Journal of Homosexuality 2 (2006): 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel A. Smith, Matthew DeSantis, and Jason Kassel. “Same-Sex Marriage Ballot Measures and the 2004 Presidential Election.” State & Local Government Review 38 (2006): 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brad Sears, and Christy Mallory. Economic Motives for Adopting LGBT-Related Workplace Policies. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Long Doan, Annalise Loehr, and Lisa R. Miller. “Formal Rights and Informal Privileges for Same-Sex Couples Evidence from a National Survey Experiment.” American Sociological Review 79 (2014): 1172–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory M. Herek. “Gay people and government security clearances. A social science perspective.” American Psychology 45 (1990): 1035–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda Baruch, and Brooks C. Holtom. “Survey Response Rate Levels and Trends in Organizational Research.” Human Relations 61 (2008): 1139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd S. Purdum. “Clinton Ends Ban on Security Clearance for Gay Workers.” New York Times. 5 August 1995. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/1995/08/05/us/clinton-ends-ban-on-security-clearance-for-gay-workers.html (accessed on 30 August 2016).

- Robert Eisenberger, Florence Stinglhamber, Christian Vandenberghe, Ivan L. Sucharski, and Linda Rhoades. “Perceived Supervisor Support: Contributions to Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Retention.” Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (2002): 565–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phyllis Moen, Erin L. Kelly, and Rachelle Hill. “Does Enhancing Work-Time Control and Flexibility Reduce Turnover? A Naturally Occurring Experiment.” Social Problems 58 (2011): 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan Grant Smith, and Kathleen M Ingram. “Workplace Heterosexism and Adjustment among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals: The Role of Unsupportive Social Interactions.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 51 (2004): 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Along these lines, a recent Canadian study of pay gaps for gay men found that these gaps were smallest among public-sector workers and largest among private-sector workers [30].

- 2We refer to these as “STEM-related agencies” rather than the more common “science agencies” because the former aligns more closely with the actual work done in these agencies (which includes mathematical, engineering, and technical work) and because “STEM” aligns with existing literature on inequality in technoscientific work.

- 3The Energy Research and Development Agency was absorbed into the DOE upon its creation in 1977 [49].

- 4For instance, in recent Pew polls, 76% of Republicans say that the government regulation of business does more harm than good (compared to 41% of Democrats) while 64% of Democrats (compared to only 28% of Republicans) believe that environmental protection should be strengthened [70].

- 5Along similar lines, interviews with sexual minority graduate students in engineering suggested that they felt more comfortable being open about their sexual identity as teaching assistants than they were as undergraduate students [19].

- 6FEVS was administered to a random sample of all permanent, non-seasonal employees of 37 large agencies and 45 independent agencies. The 2013 response rate was 48.2%, which is a typical response rate for workplace surveys [76].

- 7The Stata “chained” command was used to produce the 20 imputed datasets. Seventeen percent of responses were missing on the diversity support measure and 16 percent were missing from the meritocratic organization measure. All other measures had less than 7 percent missing.

- 8Because the sample of LGBT respondents at NSF is numerically small (N = 28), there may be LGBT*NSF effects that are too small to be picked up by the analysis. However, the p-values on the majority of the NSF*LGBT interaction terms are quite large, lending confidence that NSF does not, indeed, provide better workplace experiences than other agencies. The sample of LGBT respondents at NRC is similarly small. Several of the NRC*LGBT interaction terms approach full or marginal significance; with a larger sample, we may see an even more substantial NRC effect.

- 9Older LGBT workers report marginally lower satisfaction with their pay than younger LGBT workers, possibly reflecting actual wage gaps for older LGBT employees that have accumulated over time.

- 10The effects for employee satisfaction and job satisfaction are negative but do not reach statistical significance for women. However, the interaction term between LGBT *gender in supplemental analysis is nonsignificant, suggesting that LGBT-identifying women and men experience similar disadvantages on those measures.

- 11Occupational segregation by gender likely plays a role in the results by gender as well. The sample of women includes STEM workers but also likely a larger proportion of non-STEM workers than among the sample of men. As such, these results likely underestimate biases that women working in STEM jobs in these agencies encounter.

- 12We found that LGBT persons were equally as likely as their non-LGBT colleagues to have supervisory responsibilities in their agency.

| Perceived Treatment as Employees | |

|---|---|

| Work Success is Fostered | “I feel encouraged to come up with new and better ways of doing things”, “I am given a real opportunity to improve my skills in my organization”, “I have enough information to do my job well”, and “My talents are used well in the workplace”. (1 = [neg]ative to 3 = [pos]itive; α = 0.820) |

| Transparent Evaluations | “My performance appraisal is a fair reflection of my performance”, “My supervisor/team leader provides me with constructive suggestions to improve my job performance”, and “Discussions with my supervisor/team leader about my performance are worthwhile”, (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.816) |

| Adequate Resources | “I have sufficient resources to get my job done”, “My workload is reasonable”, and “My training needs are assessed”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.657) |

| Respected by Supervisor | “My supervisor/team leader listens to what I have to say”, “My supervisor/team leader treats me with respect”, and “My supervisor/team leader provides me with opportunities to demonstrate my leadership skills”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.852) |

| Diversity Supported | “My supervisor/team leader is committed to a workforce representative of all segments of society”, “Policies and programs promote diversity in the workplace”, “Prohibited Personnel Practices are not tolerated”, and “Managers/supervisors/team leaders work well with employees of different backgrounds”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.798) |

| Workplace Satisfaction | |

| Personal Satisfaction from Work | “I like the kind of work I do”, “My work gives me a feeling of personal accomplishment”, and “The work I do is important”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.723) |

| Satisfaction with Working Conditions | “Employees are protected from health and safety hazards on the job”, “Physical conditions allow employees to perform their jobs well”, “My organization has prepared employees for potential security threats”, and “I recommend my organization as a good place to work”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.659) |

| Employee Empowerment | “Creativity and innovation are rewarded”, “Employees have a feeling of personal empowerment with respect to work processes”, “Employees are recognized for providing high quality products and services”, and “Supervisors/team leaders in my work unit support employee development”. (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.844) |

| Satisfaction with Procedures | “How satisfied are you with the recognition you receive for doing a good job?” “How satisfied are you with your involvement in decisions that affect your work?” “How satisfied are you with your opportunity to get a better job in your organization?” and “How satisfied are you with the information you receive from management on what’s going on in your organization?” (1 = neg to 3 = pos; α = 0.835) |

| Overall Job Satisfaction | “Considering everything, how satisfied are you with your job?” (1 = neg to 3 = pos) |

| ALL | LGBT | Non-LGBT | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 37,219) | (N = 1042) | (N = 36,177) | |||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | ||

| LGBT | 0.028 | 0.001 | n/a | n/a | |||

| Female | 0.369 | 0.003 | 0.379 | 0.016 | 0.369 | 0.003 | |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | 0.279 | 0.002 | 0.251 | 0.014 | 0.279 | 0.002 | * |

| Supervisor | 0.184 | 0.002 | 0.183 | 0.012 | 0.184 | 0.002 | |

| Age cohort | 2.495 | 0.005 | 2.293 | 0.030 | 2.500 | 0.005 | *** |

| Tenure | 2.318 | 0.004 | 2.219 | 0.025 | 2.321 | 0.004 | *** |

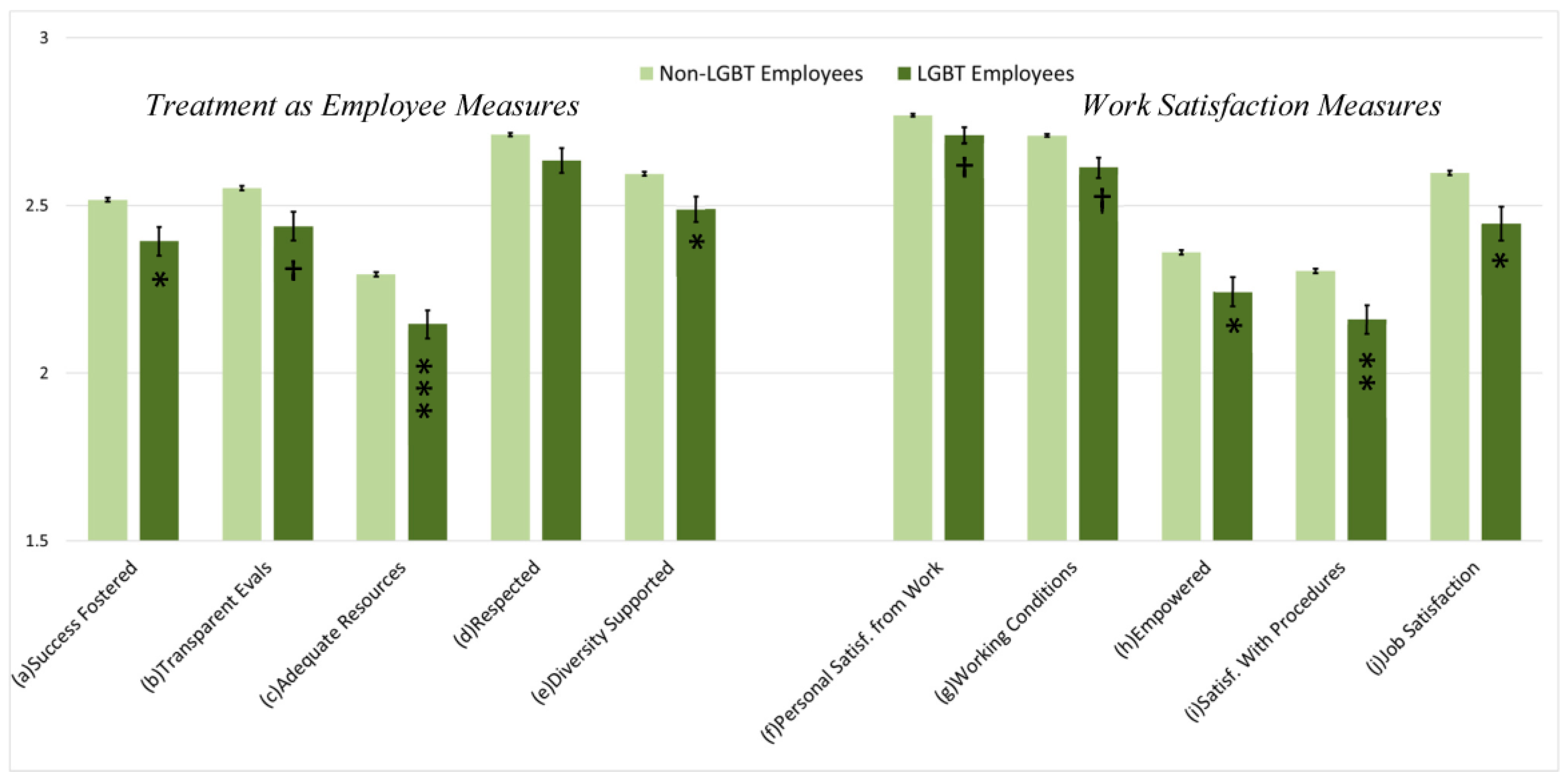

| Treatment as Employee | |||||||

| Success fostered | 2.513 | 0.003 | 2.394 | 0.021 | 2.517 | 0.003 | *** |

| Transparent evaluations | 2.548 | 0.003 | 2.438 | 0.022 | 2.551 | 0.003 | *** |

| Adequate resources | 2.291 | 0.003 | 2.146 | 0.021 | 2.295 | 0.003 | *** |

| Respected by supervisor | 2.709 | 0.003 | 2.635 | 0.019 | 2.711 | 0.003 | *** |

| Diversity supported | 2.592 | 0.003 | 2.489 | 0.019 | 2.594 | 0.003 | *** |

| Work Satisfaction | |||||||

| Personal satisfaction | 2.768 | 0.002 | 2.710 | 0.015 | 2.769 | 0.002 | *** |

| Working conditions | 2.705 | 0.002 | 2.613 | 0.015 | 2.708 | 0.002 | *** |

| Employee empowerment | 2.357 | 0.003 | 2.243 | 0.022 | 2.360 | 0.003 | *** |

| Procedure satisfaction | 2.300 | 0.003 | 2.160 | 0.021 | 2.304 | 0.003 | *** |

| Job satisfaction | 2.593 | 0.004 | 2.446 | 0.025 | 2.597 | 0.004 | *** |

| Agencies | |||||||

| EPA | 0.084 | 0.001 | .152 | 0.011 | 0.082 | 0.001 | *** |

| NRC | 0.053 | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.007 | 0.053 | 0.001 | |

| NSF | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.027 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.001 | |

| NASA | 0.218 | 0.002 | 0.168 | 0.012 | 0.220 | 0.002 | |

| DOT | 0.487 | 0.003 | 0.464 | 0.015 | 0.487 | 0.003 | |

| DOE | 0.140 | 0.002 | 0.136 | 0.011 | 0.140 | 0.002 | |

| Treatment as Employees Measures | ||||||||||

| Success Fostered | Transparent Evaluations | Adequate Resources | Respected by Supervisor | Diversity Supported | ||||||

| B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | |

| LGBT | −0.115 * | 0.046 | −0.084 † | 0.043 | −0.162 *** | 0.046 | −0.074 | 0.046 | −0.147 * | 0.066 |

| Female | 0.035 ** | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.013 | −0.031 * | 0.014 | −0.029 * | 0.012 |

| REM | 0.008 | 0.015 | −0.017 | 0.014 | 0.081 *** | 0.015 | −0.035 * | 0.014 | −0.134 *** | 0.014 |

| Supervisor | 0.203 *** | 0.014 | 0.130 *** | 0.014 | −0.048 ** | 0.016 | 0.153 *** | 0.011 | 0.216 *** | 0.011 |

| Tenure | −0.060 *** | 0.011 | −0.075 *** | 0.011 | −0.066 *** | 0.010 | −0.041 *** | 0.010 | −0.079 *** | 0.009 |

| EPA | −0.018 | 0.017 | 0.067 *** | 0.017 | −0.173 *** | 0.017 | 0.056 *** | 0.015 | 0.058 *** | 0.015 |

| NSF | 0.064 * | 0.027 | 0.079 ** | 0.028 | −0.088 ** | 0.029 | 0.029 | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.025 |

| NASA | 0.267 *** | 0.011 | 0.226 *** | 0.012 | 0.177 *** | 0.012 | 0.164 *** | 0.010 | 0.246 *** | 0.010 |

| NRC | 0.185 *** | 0.015 | 0.149 *** | 0.017 | 0.218 *** | 0.017 | 0.111 *** | 0.014 | 0.187 *** | 0.014 |

| DOT | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.071 *** | 0.015 | 0.046 ** | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.013 |

| Constant | 2.485 *** | 0.027 | 2.577 *** | 0.027 | 2.369 *** | 0.025 | 2.750 *** | 0.025 | 2.69 *** | 0.022 |

| Workplace Satisfaction Measures | ||||||||||

| Personal Satisfaction | Satisfactory w/Working Conditions | Employee Empowerment | Procedures Satisfaction | Overall Job Satisfaction ^ | ||||||

| B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | B | S.E. | |

| LGBT | −0.049 † | 0.026 | −0.080 † | 0.045 | −0.115 * | 0.046 | −0.140 ** | 0.050 | −0.379 * | 0.153 |

| Female | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.037 ** | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.078 † | 0.044 |

| REM | 0.018 * | 0.008 | 0.028 * | 0.012 | 0.042 ** | 0.015 | 0.046 ** | 0.015 | 0.081 † | 0.048 |

| Supervisor | 0.098 *** | 0.009 | 0.128 *** | 0.011 | 0.274 *** | 0.015 | 0.243 *** | 0.016 | 0.505 *** | 0.054 |

| Tenure | −0.029 *** | 0.006 | −0.058 *** | 0.008 | −0.102 *** | 0.011 | −0.092 *** | 0.010 | −0.229 *** | 0.035 |

| EPA | −0.002 | 0.012 | 0.035 * | 0.011 | 0.040 * | 0.017 | −0.037 * | 0.016 | −0.020 | 0.053 |

| NSF | 0.044 * | 0.019 | 0.064 *** | 0.017 | 0.057 * | 0.028 | 0.003 | 0.027 | 0.105 | 0.093 |

| NASA | 0.096 *** | 0.008 | 0.169 *** | 0.008 | 0.386 *** | 0.012 | 0.303 *** | 0.011 | 0.695 *** | 0.041 |

| NRC | 0.073 *** | 0.012 | 0.152 *** | 0.010 | 0.267 *** | 0.017 | 0.233 *** | 0.016 | 0.514 *** | 0.061 |

| DOT | 0.059 *** | 0.010 | −0.014 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.030 * | 0.015 | 0.279 *** | 0.049 |

| Constant | 2.728 *** | 0.015 | 2.686 *** | 0.020 | 2.296 *** | 0.027 | 2.280 *** | 0.026 | N/A | N/A |

| Supervisor Coefficient | LGBT Coefficient | Supervisor * LGBT Coefficient | Supervisor * LGBT p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment as Employee Models | ||||

| Success fostered | 0.203 *** | −0.115 * | 0.004 | 0.957 |

| Transparent evaluations | 0.131 *** | −0.079 | −0.041 | 0.572 |

| Adequate resources | −0.049 *** | −0.169 ** | 0.046 | 0.574 |

| Respected by supervisor | 0.152 *** | −0.077 | 0.024 | 0.717 |

| Diversity supported | 0.215 *** | −0.151 * | 0.026 | 0.768 |

| Work Satisfaction Models | ||||

| Personal satisfaction | 0.097 *** | −0.051 † | 0.020 | 0.670 |

| Working conditions | 0.128 *** | −0.079 | −0.011 | 0.863 |

| Employee empowerment | 0.272 *** | −0.120 * | 0.041 | 0.580 |

| Procedure satisfaction | 0.242 *** | −0.142 * | 0.018 | 0.823 |

| Job satisfaction ^ | 0.506 *** | −0.376 * | −0.026 | 0.923 |

| Age Cohort Coefficient | LGBT Coefficient | Age Cohort * LGBT Coefficient | Age Cohort * LGBT p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment as Employee Models | ||||

| Success fostered | 0.014 † | −0.155 | 0.021 | 0.672 |

| Transparent evaluations | 0.010 | −0.052 | −0.013 | 0.788 |

| Adequate resources | 0.006 | −0.247 † | 0.042 | 0.413 |

| Respected by supervisor | −0.004 | −0.072 | 0.001 | 0.989 |

| Diversity supported | 0.001 | −0.284 | 0.067 | 0.366 |

| Work Satisfaction Models | ||||

| Personal satisfaction | 0.014 ** | −0.030 | −0.009 | 0.705 |

| Working conditions | 0.026 *** | −0.133 | 0.026 | 0.574 |

| Employee empowerment | 0.039 *** | −0.116 | 0.004 | 0.978 |

| Procedure satisfaction | 0.030 *** | −0.149 | 0.006 | 0.915 |

| Job satisfaction ^ | 0.067 * | −0.376 | −0.001 | 0.998 |

| MEN (N = 22,550) | WOMEN (N = 14,669) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGBT Coefficient | Std. Error | LGBT Coefficient | Std. Error | |

| Treatment as Employee Models | ||||

| Success fostered | −0.119 † | 0.063 | −0.099 † | 0.051 |

| Transparent evaluations | −0.066 | 0.055 | −0.112 † | 0.060 |

| Adequate resources | −0.153 ** | 0.055 | −0.177 ** | 0.069 |

| Respected by supervisor | −0.061 | 0.044 | −0.092 | 0.094 |

| Diversity supported | −0.106 † | 0.053 | −0.216 † | 0.127 |

| Work Satisfaction Models | ||||

| Personal satisfaction | −0.049 † | 0.027 | −0.045 | 0.073 |

| Working conditions | −0.079 | 0.063 | −0.087 | 0.112 |

| Employee empowerment | −0.100 * | 0.049 | −0.136 | 0.086 |

| Procedure satisfaction | −0.145 * | 0.069 | −0.130 ** | 0.046 |

| Job satisfaction ^ | −0.456 * | 0.196 | −0.210 | 0.216 |

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cech, E.A.; Pham, M.V. Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010012

Cech EA, Pham MV. Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleCech, Erin A., and Michelle V. Pham. 2017. "Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies" Social Sciences 6, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010012

APA StyleCech, E. A., & Pham, M. V. (2017). Queer in STEM Organizations: Workplace Disadvantages for LGBT Employees in STEM Related Federal Agencies. Social Sciences, 6(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6010012