Abstract

This study seeks to examine the influence of mothers’ schooling accomplishments on child mortality outcomes by exploiting the exogenous variability in schooling prompted by the 1997 universal primary education (UPE) policy in Uganda. The UPE policy, which eliminated school fees for all primary school children, provides an ideal setting for investigating the causal effect of the subsequent burst in primary school enrollment on child mortality outcomes in Uganda. The analysis relies on data from three waves of the nationally representative Uganda Demographic and Health Survey conducted in 2000/01, 2006, and 2011. To lessen the bias created by the endogenous nature of education, this study employs the mother’s age at UPE implementation as an instrumental variable in the two-stage least squares model. The empirical analysis shows that one-year spent in school translates to a 2.24 percentage point decline in under-five mortality as observed at survey date and a 1.58 percentage point reduction in infant mortality even after accounting for potential confounding variables. These upshots are weakly robust to a variety of sample sizes and different model specifications. Overall, the results suggest that increasing the primary schooling possibilities for women might contribute towards a reduction in child mortality in low-income countries with high child mortality rates.

Keywords:

maternal education; child mortality; universal primary education; instrumental variable regression; Uganda JEL:

J13; I18

1. Introduction

Previous studies suggest that learned individuals tend to enjoy prolonged life spans, are healthier and have fewer, but healthy, babies [1]. The seminal works of Caldwell [2] and the subsequent body of related studies have inspired many scholars to scrutinize the contribution of parental schooling on child well-being, especially in developing countries where child fatalities are still rampant [3,4]. Part of this literature alludes to significant associations between maternal schooling and infant mortality [5,6,7,8,9]. However, whether a causal relationship exists remains a topical matter in the empirical literature, particularly in developing countries [10,11,12,13]. Given the disparate and obstinately high child mortality rates in less-industrialized countries, understanding the potential links amongst motherly learning and child survival can be an operational public policy tool for lowering child fatalities in developing countries [2,5,14].

There is sufficient evidence to suggest the existence of a causal relationship between parental schooling and child well-being in developed countries [15,16,17,18]. For developing countries, the evidence is surprisingly thin. It is only recently that research has attempted to establish a causal connection between maternal schooling and under-five mortality outcomes [13,14,19]. This study adds to this emerging literature for developing countries by examining the causal influence of mothers’ educational accomplishments on child mortality outcomes in Uganda—a nation still experiencing high under-five mortality rates despite making recent progress [20]. The official statistics for Uganda reveal that nearly 38 children per every 1000 live births perished before celebrating their first birthday while approximately 55 children per every 1000 live births failed to celebrate their fifth birthday in 2015 [20]. This study uses data from three most recent waves of the nationally representative Demographic and Health Survey for Uganda (UDHS) conducted in 2000/01, 2006 and 2011. The methodology adopted here is somewhat similar to that employed in related studies by Grépin and Bharadwaj [14] and Makate and Makate [21]. The two noted studies examine the impact of mother’s education on child mortality in Zimbabwe and Malawi respectively. The primary goal in this analysis is to assess whether primary learning might help lower mortality rates in less-industrialized nations such as Uganda. While there has been a recent surge in empirical studies examining the causal effects of maternal schooling in developing countries, we are not aware of related studies that have been conducted in the case of Uganda.

2. Related Literature

The link between schooling and health outcomes has received lots of attention from numerous researchers, especially in economics and other related social sciences [1,22]. While there seems to be an agreement among researchers on the positive correlation between schooling and health, empirical evidence on the causal connection is far from conclusive [23,24]. Moreover, numerous studies have primarily focused on developed country contexts with less emphasis on developing countries [12]. The goal of this brief appraisal of the literature is threefold. First, we discuss policy implications of educational changes on child health outcomes. Second, we deliberate the methodologies often employed by previous related studies. Lastly, we discuss the potential passageways through which mothers’ schooling achievements might impact child survival.

Previous studies concur on the correlation that exists between under-five survival and maternal schooling even after accounting for other important factors like the father’s level of education [2,25,26]. Whether the observed positive correlation reflects improvements in health knowledge or empowerment of the women, it remains to be empirically ascertained [19]. Mothers’ education levels are said to have a larger influence on child well-being than fathers’ education [14,26,27]. This finding has prompted many to believe that public transfers to women are more effective in enhancing child well-being than transfers to the father [26,28,29]. Mothers’ schooling is also linked to favorable developments in the physical stature of her offspring such as height-for-age, weight-for-age, and birth weight [17,19,30]. This observation can be explained by the fact that learned mothers are more liable to comprehend the benefits of nutrition and thus liable to give their children nutritious foods [31]. Prior literature has established that children born with below average birth weights are more liable to spend less time in school [32,33]. This observation highlights the consequence of educating the mother as it is not only associated with improved outcomes for herself but her offspring as well.

The main challenge encountered by the empirical literature in the quest to establish a causal connection between maternal schooling and child health has mainly been methodological. The most prominent studies have relied on the exogenous variability in education brought about by education reforms as instrumental variables to address the endogeneity of schooling. This literature mostly applies instrumental variables (IV) methods to consistently estimate the influence of schooling achievements on child health outcomes. For example, Chou, Liu, Grossman and Joyce [15] used a two-stage least square (2SLS) approach to assess the causal influence of parental schooling on early health (measured by birth weight) and under-five mortality. Exploiting the 1968 schooling initiative in Taiwan as the omitted instrument in a 2SLS model, they established that increased schooling saved nearly one child in every 1000 live births which translated to an approximate 11 percent decline in infant mortality. In a study in Norway, Grytten, Skau and Sørensen [16] used a 2SLS methodology to investigate the influence of the 1967–2007 schooling reform on child birth weight. Their results indicated a rather large effect of the mother’s education level on birth weight [16]. Similarly, Gunes [17] used a 2SLS framework to inspect the contribution of motherly learning on child health and nutrition outcomes in Turkey. Using the 1997 educational policy development in Turkey, they found that mothers’ primary school completion lowered the prospect of low infant birth weight and improved child nutrition as measured by height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores even after accounting for numerous potential mediating factors [17]. More recently, Grépin and Bharadwaj [14] examined the important role played by maternal secondary schooling on under-five mortality in Zimbabwe. Using an IV technique they established that an added year of secondary schooling lowered the plausibility of child death by nearly 21 percent [14]. In a related study, Makate and Makate [21] established that increasing primary schooling of the mother by an additional year lowered the plausibility of infant and under-five mortality in Malawi by nearly 3.22 and 6.48 percentage points [21]. Quamruzzaman et al. [34] used the propensity score matching technique to establish whether UPE policies in less-industrialized economies had any protective effect on neonatal and infant mortality rates. Their results indicated a beneficial effect of UPE policies on infant survival in these countries [34]. In Nigeria, Osili and Long [35] used a differences-in-differences technique to analyze the influence of female learning on fecundity behavior. Their results indicated that a one-year increase in schooling lowered the plausibility of early fertility by about 0.26 births amongst Nigerian women of reproductive ages. Other studies for developing and developed countries relying on 2SLS methods to establish causal effects of parental learning on child well-being include, but are not limited to, the following: Breierova and Duflo [36]; Currie and Moretti [18]; and Lindeboom, Llena-Nozal and van der Klaauw [27].

The health economics literature suggests numerous passageways through which schooling affects child well-being. One frequently cited channel through which schooling could impact child health is through its effect on the socioeconomic status of the individual or the family [10]. Increased schooling enhances a woman’s chances of getting high paying jobs which indirectly impacts the health of her offspring [27,37]. Other studies have established a negative association between increased schooling and fertility behavior [14,35,38,39]. Furthermore, parental schooling might positively impact child well-being through its effect on parental cognition and health knowledge [1,19,40]. At the community level, researchers have established that aggregate schooling levels can help improve village sanitation and consequently child nutrition [13,41]. For the purposes of this analysis, we ignore the examination of the potential alleyways through which education impacts child mortality outcomes.

This study employs an instrumental variables technique to assess the causal effect of maternal schooling on child mortality outcomes in Uganda. The empirical analysis exploits the exogenous variability in education prompted by the 1997 UPE in Uganda as a natural experiment to consistently estimate the causal influence of schooling on under-five mortality. Particularly, we compare the mortality outcomes for women aged 5–13 years to those aged 17–25 in 1997. The primary hypothesis to be tested being that increased primary schooling lowers child mortality in the setting of a high mortality country like Uganda.

3. Universal Primary Education in Uganda

Uganda is among the first countries to have adopted a UPE policy in 1997 [42]. The implementation of the UPE policy saw an explosion in primary school enrollment from 3.1 million children in 1996 to about 8.7 million in 2014 [43]. The primary objective of the UPE policy in Uganda was to enable all Ugandan children to enroll and complete their primary education [44]. This was to be achieved through the government’s capitalization grant (the UPE grant) to schools [45]. The government eliminated tuition fees for all children at the primary school level, effective 1 January, 1997 [46,47]. Under this initiative, parents still had the responsibility of paying other school-related expenses including food, books, uniforms and transportation for their children [48]. To guarantee that the benefits of this education policy spread to every Ugandan child regardless of location and socioeconomic status, the Ugandan Ministry of Education embarked on a massive advertising campaign with targeted messages aimed at encouraging girls to entirely exploit the benefits of this education initiative [46]. Despite all the merits allied to the UPE, critics often cite a reduction in education quality following the implementation of this education program [46]. Others have cited low internal efficiency of the program to the extent that only 22% of the children who enrolled in grade one in 1997 made it to grade seven in 2003 [49]. Nearly 78% of these children experienced grade repetition with only 5% dropping out completely [49]. The very low drop-out rate of 5% is less liable to negatively impact the overall analysis estimates. We cannot assess the quality of the UPE policy due to data limitations. However, we have no reason to believe that the quality concerns raised by critics of the UPE are likely to impact the estimates greatly.

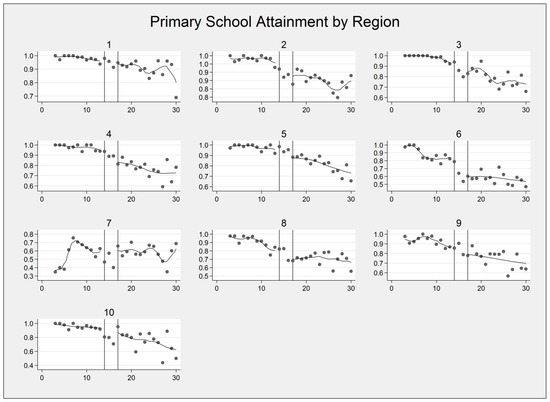

The UPE policy was a nationwide policy that sought to provide free primary schooling opportunities for the underprivileged children from poor families in Uganda. Figure 1 shows the average probabilities of primary learning in each of Uganda’s ten provinces. The graph indicates that across all the provinces except for Karamoja, women aged 13 years and younger had a higher probability of enrolling into primary school than their relatively older counterparts.

Figure 1.

Primary school attainment by region of residence: Regions: 1 = Kampala, 2 = Central 1, 3 = Central 2, 4 = East central, 5 = Eastern, 6 = North, 7 = Karamoja, 8 = West-Nile, 9 = Western, 10 = Southwest. Note that the figures on the y-axis are rounded to one decimal point.

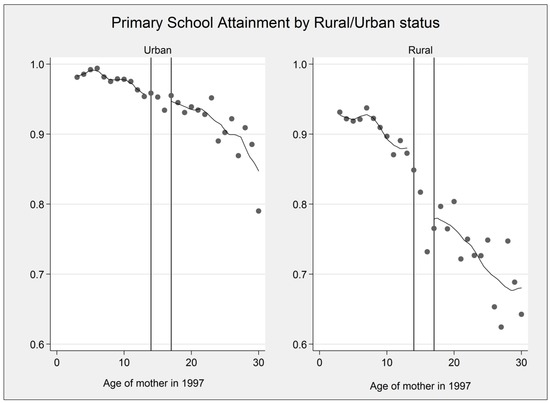

In Figure 2, we observe that women in urban communities had a higher overall probability of enrolling into primary schooling than their rural counterparts (averaging around 60% compared to above 60% for urban residents). We do observe that the discontinuity at age 13 is clearer for the rural sample than it is for the urban sample. Overall, Figure 2 appears to support the claim that the UPE policy had a larger impact for the group of women aged 13 and under than it did for the relatively older sample. This observation provides further support to the identification strategy (see Section 4).

Figure 2.

Primary school attainment by urban or rural residence.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Source

The analysis in this study uses data from three waves of the nationwide Uganda Standard Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS) conducted in 2000/01, 2006 and 2011. The UDHS is a cross-sectional household survey conducted by Inner City Fund (ICF) International in collaboration with the government of Uganda. The UDHS collects detailed health information for women of reproductive ages 15–49 and their children. The survey uses a stratified two-stage cluster sample design based on the Uganda population censuses of 1991 and 2002 provided by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). The first stage involved a random sampling of clusters or enumeration areas followed by a random sampling of listed households within the randomly selected clusters (excluding families living in institutional facilities like boarding schools, hospitals, army barracks, or police camps) at the second stage. The individual response rates in the 2000/01, 2006, and 2011 UDHS surveys were high, 94%, 95%, and 94% respectively.

4.2. Measures of Child Mortality

We assemble under-five mortality data from the UDHS birth histories file which contains detailed fertility history for each interviewed woman of reproductive ages 15–49 years. Recorded in the birth records are all the births of each interviewed lady, the birth date and date of deaths (if the child died before the survey date). We construct three binary indicators to measure child mortality. First, we create a binary indicator taking 1 if the child was deceased (at survey time) and 0 otherwise. Second, a binary indicator equals 1 if the child died before reaching the age of one and 0 otherwise is created. Lastly, we created a binary indicator taking 1 if the child died before reaching the age of five (under-five mortality) and 0 otherwise. The mortality definitions used here are consistent with international measurements of child mortality rates [50].

4.3. Explanatory Variables

To examine the causal effect of motherly learning on child mortality, this study uses the respondent’s (woman) completed schooling years observed at the survey date. Many control variables believed to influence under-five mortality are also included. These variables include binary indicators for the region of habitation (Kampala, Central 1, Central 2, East central, Eastern, Karamoja, North, West Nile, Western and Southwest), urban residence, the woman’s previous birth experiences, child’s birth year, birth type (single or multiple births), child’s gender (female = 1), and indicators for the survey year to account for the likely influence of time. The parity of the woman, measured by the total births in the last five years, is also controlled for in the regression models.

4.4. Econometric Model

To assess the association between maternal schooling and child mortality, the following basic equation is estimated:

where is the dependent variable of interest of the ith woman; refers to the woman’s years of learning; is a vector of maternal and child health characteristics as mentioned earlier. The parameter is an intercept term, is an idiosyncratic error term. The primary coefficient of interest is capturing the influence of motherly learning on child mortality or other maternal health outcomes. Estimating Equation (1) via Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) or standard probit/logit regression results in an inconsistent coefficient estimate of due to the influence of some potentially unobserved maternal characteristics affecting child mortality. To minimize the chances of omitted variable bias, Equation (1) is estimated using a Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS) or instrumental variable (IV) approach.

The two-stage regression model we estimate is of the type specified in Makate and Makate [21], Grépin and Bharadwaj [14]; Fenske [51], and Tsai and Venkataramani [52] among others and is shown below. The first stage is specified as follows:

where measures maternal education; is the instrumental variable taking 1 if the woman’s age in 1997 was 13 years or below and 0 otherwise; is the woman’s age in 1997; Xi is the vector of control variables mentioned earlier; is an intercept term; , , , are regression coefficients and, is an idiosyncratic error term. Equation (2) also takes into account linear approximations around the age 13 cutoff. The predicted values for maternal education from Equation (2) are then used in the second stage regression model that takes the following form:

Estimating Equation (3) via IV regression gives the coefficient estimate which we construe as the causal influence of motherly learning on child mortality outcomes. Following van der Klaauw [53]; Hahn et al. [54]; Grépin and Bharadwaj [14]; Tsai and Venkataramani [52] and Behrman [55], the dummy variable for susceptibility to the 1997 UPE policy (i.e., age 13 years or under in 1997) is used as the instrumental variable in the IV model [53,54]. Though other non-tuition fees might have played a role in influencing whether the woman enrolled into primary school or not, the age of the woman at UPE implementation had the biggest influence on enrollment. This study, therefore, compares the upshots for women of primary schooling ages 5–13 years in 1997 (treated group) to those of women aged 17–25 years in 1997 (control group). We disregard the 14–16 age group since they are most liable to have partly profited from the reform. In a sensitivity check, including these women does not significantly alter the primary findings (results available upon request). We prefer to guesstimate the binary dependent variables for child mortality using linear probability models (LPM) owing to the ease in interpretation De Janvry et al. [56] and the consistency of the results, particularly under conditions of suspected heteroskedasticity Hyslop [57], a common phenomenon in cross-sectional data [58].

4.5. Robustness Checks

It is plausible that the empirical estimates we find are plagued by time effects or secular time trends, a common problem in studies of this nature. As a sensitivity check, we carried out additional analyses to assess the robustness of the child mortality estimates. First, since elderly women have had more time giving birth than their relatively younger counterparts, it is plausible that the mortality estimates reported here suffer from a right-censoring problem. To examine this possibility, we compare the mortality outcomes of women who were aged 19–27 in the survey year 2011 (mainly impacted by the reform) to the cohort of similar age in 2000 (and not impacted by the reform). This comparison helps delineate the age effects from the education effects.

Second, as is customary in analyses of this nature, we restricted the age bandwidths to the 8–22 and 10–20 years in 1997. This adjustment in the age bandwidth ensures that the mortality estimates are comparable and less liable to suffer to secular time trends. However, the narrower age bandwidth negatively impacts statistical power.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics for the overall, treatment and comparison groups are displayed in Table 1 together with the pairwise t-tests for these groups. The average years of learning for the women in the 5–25 age cohort was 4.547 years. Approximately, 15.7% of the women live in urban areas, 40% are from low wealth backgrounds with 40.7% coming from relatively affluent families. About 24.7% of the women in the analysis sample had previously terminated their pregnancy at least once. Many of the women gave birth for the first time around the age of 18 years.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of selected variables.

Almost 49.4% of the children are female, 2.9% are non-single births, and many of them were born in 1995. Geographically, the proportion of children ranges from 2.9% in the Karamoja region to 16.8% in the Central 1 region. As expected, the average time spent in school by women in the intervention group was higher (about 5.924 years) compared to that of the comparison group (about 4.609 years). The corresponding pairwise t-test discloses that the difference is meaningfully significant at 1%. The t-test results reveal significant differences between the control and treatment groups on observable characteristics except for the parity, urban residence, child’s gender and birth type. The observation that the treatment and comparison group appear somewhat similar in terms of parity over the last five years gives us reason to rule out earlier concerns for the possibility of right censoring on the child mortality estimates. If right censoring was indeed a significant problem, we would expect to see a statistically significant difference between the treatment and comparison groups. We discern that the average woman in the treatment (control) group had given birth to about 1.54 (1.547) children in the past five years from each survey.

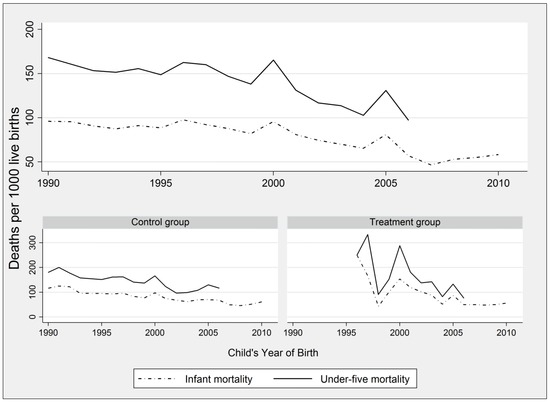

Figure 3 depicts the evolution of infant and under-five mortality for the overall, treatment and comparison groups using data for the three most recent waves for Uganda, collected in 2000/01, 2006 and 2011 by child’s birth year. The trends indicate a persistent and steady decline in overall infant and under-five mortality rates in Uganda over the last decades. Looking at the comparison and treatment groups, Figure 3 shows that the mortality pattern for the comparison group does not show any drastic changes compared to that of the treatment group (women aged 5–25 in 1997). Concerning the treatment group, we observe a sharp decline in child mortality coinciding with the year of UPE implementation in 1997. However, this observed discontinuity did not appear to last long as mortality patterns rose again in 2000 before showing a declining trend thereafter. The observed discontinuity in infant and under-five mortality appears to corroborate the earlier hypothesis that the 1997 UPE resulted in a fall in child mortality in Uganda, though the impact seems to be short-lived.

Figure 3.

Child mortality trends by year of child’s birth for the overall, treatment and control groups.

5.2. First Stage Results

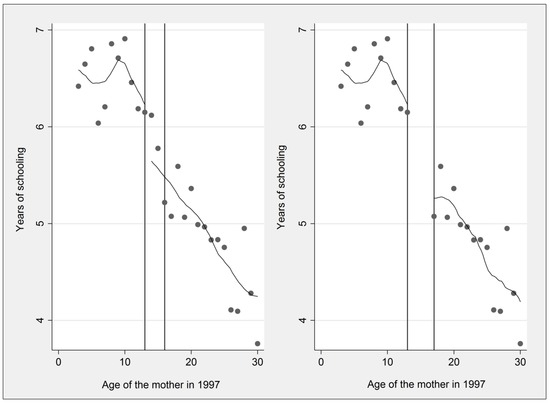

Figure 4 shows the influence of the 1997 UPE policy on motherly learning in Uganda using data from the waves of the UDHS conducted in 2000/01, 2006 and 2011 [59,60,61]. The two perpendicular lines shown represent the age 14 and 16 markers. To the left(right) side of these lines lies the treatment(control) group. Figure 4 appears to show a fall in schooling from age 16 in 1997. We can observe that women who were 13 years and under in 1997 acquired more years of schooling compared to their counterparts aged 17 and above in 1997. The observed jump in completed years of education seems to overlap with the sharp decline in under-five mortality shown in Figure 3. This discontinuity is even clearer if we consider the graph excluding women in 14–16 age bandwidth.

Figure 4.

The effect of the universal primary education policy on maternal education In Uganda. Note: The graph to the right excludes those women who were aged 14–16 years in 1997.

The results of the first stage regression are summarized in Table 2. In this model, we regress the woman’s years of learning on the indicator variable for exposure to the UPE using an OLS regression model. The results indicate that the 1997 schooling reform in Uganda was allied to an overall average increase in maternal schooling of approximately 0.682 years even after adjusting for potential mediating factors.

Table 2.

First stage results: Effect of the 1997 universal primary education reform on maternal education.

The results also indicate that the first stage upshots are robust to different sample sizes as shown in the three columns (2, 3, and 4). The bottom section of Table 2 displays the marginal probability effects from the probit regression model for the influence of the UPE policy on the prospect of primary learning completion. The results show that for the overall sample, a woman aged 13 years and under in 1997 had a 4.6 percentage point likelihood of completing primary school compared to her counterpart aged 17 years and above. These results remain unaltered even after considering a variety of sample sizes as displayed in columns 2–4.

To judge the legitimacy and strength of the instrumental variable, we conducted the standard F-test statistic (shown in Table 3). An instrumental variable is considered strong if the first stage F-test statistic exceeds 10 [62]. The findings from the F-tests point to a strong instrumental variable. However, the F-test statistics from the models using the binary indicator for primary school completion as the instrumented variable seem to suggest the possibility of a weak instrumental variable (results not shown in Table 3). The first stage F-test statistics from these models range from 2.651 to 7.807 suggesting that the instrumental variable is weak.

Table 3.

Effect of maternal education on child mortality.

5.3. Second Stage Results

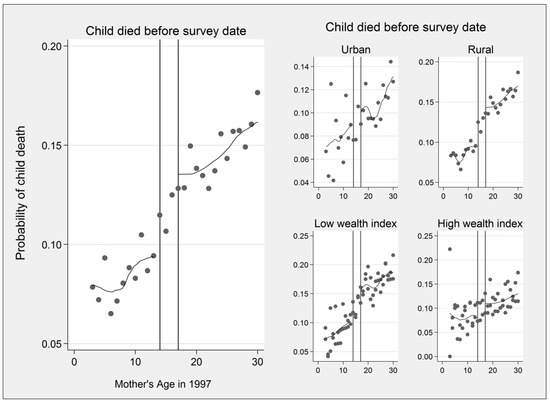

The left panel of Figure 5 shows the average mortality rates for children born to women aged 5–25 in 1997. There seems to be an irregular drop in the prospect of child mortality corresponding to the time of the UPE policy. This finding also corroborates the disjointedness in mortality observed in Figure 3. Figure 5 shows that women aged 13 years and under in 1997 had a lower probability of experiencing a child death compared to their counterparts older than 13 years in 1997. The right panel also shows the heterogeneities in child mortality by rural or urban and household wealth status. It appears that women (13 years and younger in 1997) from low-wealth households and residing in non-metropolitan areas had the least probabilities of experiencing a child death matched to those above 13 years. However, we cannot make solid conclusions from the graphical analysis alone, instead, we turn to the IV regression results.

Figure 5.

The impact of universal primary education on child mortality for the overall sample (left panel), urban or rural and household wealth status.

Table 3 presents the OLS and IV regression coefficients for the influence of motherly learning on child mortality in Uganda. The OLS results show a statistically significant and negative association between mothers’ schooling and child mortality (infant and under-five mortality). A comparison of the OLS estimates to the IV results demonstrates that the effect of education on child mortality is underestimated (e.g., 0.0043 vs. 0.0224).

Table 3 also displays the IV regression estimates (the lowermost panel of Table 3). Maternal schooling is instrumented using a binary indicator taking 1 if the woman was aged 13 years or under in 1997 and 0 otherwise. The results show that a one-year increase in motherly learning translated into a 2.24 percentage point decline in child mortality by the survey date. This result imprecisely signifies a 17.5% drop in child mortality given that nearly 12.8 percent of children died by the survey date. Also, a one-year increase in maternal schooling lowers the plausibility of infant mortality by about 1.58 percentage points. This reduction imprecisely translates into a 19.27% drop in child mortality given that, on average, 8.2% of the children in the analysis sample died in infancy. The influence of motherly learning on under-five mortality is negative but statistically insignificant. The results, when we consider the binary indicator for primary school completion as the instrumented variable, show that the mortality estimates are weakly robust to this change. Specifically, we observed a drop in the prospect of child death by nearly 0.405.

To assess the robustness of the child mortality results, we conduct an array of sensitivity checks. The results of these tests are presented in Table 4. First, since the results are more liable to be biased by secular time trends, we re-estimated the model in Equation (3) but this time matching the outcomes for women aged 19–27 in 2011 (impacted by the UPE reform) to those of similarly aged women in 2000 (not affected by the reform). This comparison is critical for us to examine whether the estimates are compounded by age-effects or time effects. Here, the instrumental variable becomes the binary variable taking 1 for women aged 19–27 in 2011 and 0 if aged 19–27 in 2000. The top section of Table 4 shows the estimates from regression models using this instrumental variable. The results show a statistically meaningful effect of schooling on mortality by the survey date and infant mortality. Specifically, we observe that an added year of primary learning lowers the prospect of infant mortality by nearly 2.25 percentage points. The results suggest that the mortality estimates found in Table 3 are less liable to be compounded by age or time effects.

Table 4.

Robustness checks—Two stage least squares estimates of the effect of mothers’ education on child mortality outcomes.

Second, how the mortality estimates would respond to changes in the age bandwidth (8–22 and 10–20) was checked. In these models, we re-estimated Equation (3) using the age 13 indicator variable as the instrumental variable. The upshots for the 8–22 age bandwidth suggest that an added year of primary learning lowers the plausibility of mortality by the survey date and infant mortality. This finding is statistically significant at the 1% level. Changing the age bandwidth to 10–20 years in 1997 reveals a weakly robust effect of motherly learning on child mortality. Overall, the results suggest that the mortality estimates found in Table 3 are weakly robust to the sensitivity checks we conducted. Thus, the estimates cannot imply a causal influence of motherly learning on child mortality in Uganda.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

We examined the causal effect of mothers’ schooling on child mortality outcomes in Uganda. To test the causal nature of maternal schooling, we have relied on the exogenous variability in schooling induced by the UPE policy in Uganda. The results have shown that the education reform had a significant impact on primary school attendance for women aged 5–13 years in 1997. The IV estimates revealed that an added year of primary learning lowered the plausibility of child death by the survey date and infant mortality. The sensitivity checks suggested that the mortality estimates presented here are weakly robust to possible variations in the age bandwidth.

The baseline OLS estimates we found are smaller than the IV estimates. This difference can be attributed to the observation that the 2SLS model estimated the local average treatment effects (LATE) while the OLS estimates reflect the average treatment effect (ATE) [63]. We speculate that girls from average wealthy families are more liable to be driving the observed LATE. Since the UPE policy in Uganda did not eliminate other fees associated with school uniforms, school stationary, and food, it is plausible that children from very poor families are less liable to have profited from the UPE initiative and hence less liable to be impacting the results. As noted in Alcott and Rose [64], observable wealth differences might account for the differential access to learning in East Africa [64]. We rule out the plausibility that girls from affluent families are driving the result since the UPE policy did not alter the enrollment rates for this group as they could afford the tuition rates.

The results corroborate previous and more recent studies in developing countries which found a protective effect of motherly learning on child survival. For example, Grépin and Bharadwaj [14] used a change in the Zimbabwe’s schooling system to examine the causal effect of secondary learning on child mortality outcomes. Their results suggested a 21% decline in under-five mortality following the 1980 schooling reform in Zimbabwe that prompted a burst in secondary school expansion. The analysis differs from the Grépin and Bharadwaj [14] study in that we concentrate on the influence of the UPE in Uganda that expanded primary learning prospects for Ugandan children. This study contributes to the literature by testing whether education policies at the primary level are helpful in lowering child deaths in developing countries. Though not perfectly comparable, the results can be compared to those found in Grépin and Bharadwaj [14]. The 17.5% decline in child mortality we found seems to align with research that suggests that increases in education at the secondary school level are much more effective than increases at the primary school level [12]. The results here also corroborate the findings in Makate and Makate [21] who established that increasing maternal schooling by an additional year was associated with a 34.07% and 36.26% reduction in infant and under-five mortality in Malawi. Their findings appear to suggest a much stronger effect of maternal education on child mortality outcomes.

This study is not without its shortcomings. First, this study acknowledges that measuring the schooling level of the woman at the survey date might not be a precise and accurate representation of her actual educational attainment. It is possible that some of the women in the analysis sample might have acquired more education after the survey date which might have had an effect on the results. Second, even though the analysis here makes an attempt to address the issue of secular time trends, the estimates might still be minimally biased. Third, the fuzzy regression discontinuity strategy adopted has often been highly criticized for lack of statistical power due to its demanding statistical requirements. Given that the analysis compares the mortality estimates for women close to the age 13 cut-off, the samples become less comparable once we drift further from this cut-off point. Thus, one should interpret these results with caution. Despite the above concerns, the present study meaningfully adds to the currently scarce literature for developing countries. Overall, the results suggest that increasing the primary learning opportunities for women might be an effective strategy for lowering child mortality in less-industrialized regions such as sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgments

This research has immensely benefited from comments made by Econometrics Seminar Participants and the Health Economics Work Group at the State University of New York at Albany. We are also grateful to MEASURE DHS for granting us unlimited access to the DHS data for Uganda.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Michael Grossman. “Education and nonmarket outcomes.” Handbook of the Economics of Education 1 (2006): 577–633. [Google Scholar]

- John C. Caldwell. “Education as a factor in mortality decline an examination of Nigerian data.” Population Studies 33 (1979): 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linda G. Martin, James Trussell, Florentina Reyes Salvail, and Nasra M. Shah. “Co-variates of child mortality in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Pakistan: An analysis based on hazard models.” Population Studies 37 (1983): 417–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Bellessa Frost, Renata Forste, and David W. Haas. “Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: Finding the links.” Social Science & Medicine 60 (2005): 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John G. Cleland, and Jerome K. van Ginneken. “Maternal education and child survival in developing countries: The search for pathways of influence.” Social Science & Medicine 27 (1988): 1357–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George T. Bicego, and Boerma J. Ties. “Maternal education and child survival: A comparative study of survey data from 17 countries.” Social Science & Medicine 36 (1993): 1207–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary Mahy. “Childhood Mortality in the Developing World: A Review of Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys.” DHS Comparative Reports No. 4. Calverton, MD, USA: MEASURE DHS+, ORC Macro, December 2003, vol. 4. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR4/CR4.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- T. Akter, D. M. E. Hoque, E. K. Chowdhury, M. Rahman, M. Russell, and S. E. Arifeen. “Is there any association between parental education and child mortality? A study in a rural area of Bangladesh.” Public Health 129 (2015): 1602–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emily Smith-Greenaway. “Maternal reading skills and child mortality in Nigeria: A reassessment of why education matters.” Demography 50 (2013): 1551–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John Hobcraft. “Women’s education, child welfare and child survival: A review of the evidence.” Health Transition Review 3 (1993): 159–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alaka Malwade Basu. “Maternal education, fertility and child mortality: Disentangling verbal relationships.” Health Transition Review 4 (1994): 207–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lance J. Lochner. “Nonproduction benefits of education: Crime, health, and good citizenship.” NBER Working Paper 16722. Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2011, pp. 183–282. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16722.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- Sonalde Desai, and Soumya Alva. “Maternal education and child health: Is there a strong causal relationship? ” Demography 35 (1998): 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karen A. Grépin, and Prashant Bharadwaj. “Maternal education and child mortality in Zimbabwe.” Journal of Health Economics 44 (2015): 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin-Yi Chou, Jin-Tan Liu, Michael Grossman, and Theodore J. Joyce. “Parental education and child health: Evidence from a natural experiment in Taiwan.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2 (2010): 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jostein Gryttena, Irene Skau, and Rune J. Sørensen. “Educated mothers, healthy infants. The impact of a school reform on the birth weight of Norwegian infants 1967–2005.” Social Science & Medicine 105 (2014): 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pınar Mine Gunes. “The role of maternal education in child health: Evidence from a compulsory schooling law.” Economics of Education Review 47 (2015): 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet Currie, and Enrico Moretti. “Mother’s education and the intergenerational transmission of human capital: Evidence from college openings.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (2003): 1495–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Glewwe. “Why does mother’s schooling raise child health in developing countries? Evidence from morocco.” The Journal of Human Resources 34 (1999): 124–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, and UN-DESA Population Division. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality. Edited by Natalie Leston. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall Makate, and Clifton Makate. “The causal effect of increased primary schooling on child mortality in Malawi: Universal primary education as a natural experiment.” Social Science & Medicine 168 (2016): 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo Sabates, Jo Westbrook, and Jimena Hernandez-Fernandez. “The 1977 universal primary education in Tanzania: A historical base for quantitative enquiry.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 35 (2012): 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damien de Walque. “Does education affect smoking behaviors? Evidence using the vietnam draft as an instrument for college education.” Journal of Health Economics 26 (2007): 877–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriana Lleras-Muney. “The relationship between education and adult mortality in the United States.” Review of Economic Studies 72 (2005): 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Paul Schultz. “Returns to women’s education.” In Women’s Education in Developing Countries: Barriers, Benefits, and Policies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, pp. 51–99. [Google Scholar]

- John Strauss, and Thomas Duncan. “Chapter 34 human resources: Empirical modeling of household and family decisions.” In Handbook of Development Economics. New York: Elsevier, 1995, vol. 3, part A; pp. 1883–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maarten Lindeboom, Ana Llena-Nozal, and Bas van der Klaauw. “Parental education and child health: Evidence from a schooling reform.” Journal of Health Economics 28 (2009): 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul Gertler. “Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? Evidence from progresa’s control randomized experiment.” The American Economic Review 94 (2004): 336–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar Martinelli, and Susan W. Parker. “Do school subsidies promote human capital investment among the poor? ” The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 110 (2008): 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Duncan, John Strauss, and Maria-Helena Henriques. “How does mother’s education affect child height? ” Journal of Human Resources 26 (1991): 183–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcan Yabancı, Ibrahim Kısaç, and Suzan Şeren Karakuş. “The effects of mother’s nutritional knowledge on attitudes and behaviors of children about nutrition.” Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 116 (2014): 4477–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jere R. Behrman, and Mark R. Rosenzweig. “Returns to birthweight.” Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (2004): 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra E. Black, Paul J. Devereux, and Kjell G. Salvanes. From the Cradle to the Labor Market? The Effect of Birth Weight on Adult Outcomes. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Amm Quamruzzaman, José M. Mendoza Rodríguez, Jody Heymann, Jay S. Kaufman, and Arijit Nandi. “Are tuition-free primary education policies associated with lower infant and neonatal mortality in low-and middle-income countries? ” Social Science & Medicine 120 (2014): 153–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Una Okonkwo Osili, and Bridget Terry Long. “Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria.” Journal of Development Economics 87 (2008): 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia Breierova, and Esther Duflo. “The impact of education on fertility and child mortality: Do fathers really matter less than mothers? ” NBER Working Paper 10513. Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2004. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w10513.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2016).

- Anne Case, Darren Lubotsky, and Christina Paxson. “Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient.” The American Economic Review 92 (2002): 1308–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pınar Mine Güneş. “The impact of female education on teenage fertility: Evidence from Turkey.” The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 16 (2016): 259–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David M. Cutler, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. “Education and health: Evaluating theories and evidence.” In Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy. Edited by Robert F. Schoeni, James S. House, George A. Kaplan and Harold Pollack. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2008, pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Grossman. “The relationship between health and schooling: What’s new? ” NBER Working Paper 21609. Cambridge, MA, USA: National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2015. Available online: http://papers.nber.org/tmp/21399-w21609.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Harold Alderman, Jesko Hentschel, and Ricardo Sabates. “With the help of one’s neighbors: Externalities in the production of nutrition in Peru.” Social Science & Medicine 56 (2003): 2019–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred M. Ssewamala, Julia Shu-Huah Wang, Leyla Karimli, and Proscovia Nabunya. “Strengthening universal primary education in Uganda: The potential role of an asset-based development policy.” International Journal of Educational Development 31 (2011): 472–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2015 Statistical Abstract. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2004 Statistical Abstract. Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ikuko Suzuki. “Parental participation and accountability in primary schools in Uganda.” Compare 32 (2002): 243–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus Deininger. “Does cost of schooling affect enrollment by the poor? Universal primary education in Uganda.” Economics of Education Review 22 (2003): 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja Bentaouet Kattan. “Implementation of free basic education policy.” The Education Working Paper. Washington, DC, USA: The World Bank, December 2006, p. 7. Available online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/EDWP_User_Fees.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Louise Grogan. “Universal primary education and school entry in Uganda.” Journal of African Economies 18 (2009): 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert Byamugisha. Overall Performance of Districts and Constraints towards Attainment of Sector Targets Using the District League Table (Basing on Education Performance Index: EPI). Kampala: Government of Uganda, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). World Health Statistics 2015. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- James Fenske. “African polygamy: Past and present.” The Journal of Development Economics 117 (2015): 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander C. Tsaia, and Atheendar S. Venkataramani. “The causal effect of education on HIV stigma in Uganda: Evidence from a natural experiment.” Social Science & Medicine 142 (2015): 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbert van der Klaauw. “Estimating the effect of financial aid offers on college enrollment: A regression-discontinuity approach.” International Economic Review 43 (2002): 1249–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinyong Hahn, Petra Todd, and Wilbert van der Klaauw. “Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design.” Econometrica 69 (2001): 201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia Andrea Behrman. “The effect of increased primary schooling on adult women’s HIV status in Malawi and Uganda: Universal primary education as a natural experiment.” Social Science & Medicine 127 (2015): 108–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alain de Janvry, Frederico Finan, Elisabeth Sadoulet, and Renos Vakis. “Can conditional cash transfer programs serve as safety nets in keeping children at school and from working when exposed to shocks? ” Journal of Development Economics 79 (2006): 349–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean R. Hyslop. “State dependence, serial correlation and heterogeneity in intertemporal labor force participation of married women.” Econometrica 67 (1999): 1255–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey M. Wooldridge. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), and Macro International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton: UBOS and Macro International Inc., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), and Macro International Inc. Uganda: Demographic and Health Survey 2000–2001. Calverton: UBOS and Macro International Inc., 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala: UBOS. Calverton: ICF International Inc., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Staiger, and James H. Stock. “Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments.” Econometrica 65 (1997): 557–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshua D. Angrist, Guido W. Imbens, and Donald B. Rubin. “Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 91 (1996): 444–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcott Benjamin, and Pauline Rose. “Does private schooling narrow wealth inequalities in learning outcomes? ” Oxford Review of Education 42 (2016): 495–510. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).