Integrated Social Housing and Health Care for Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals: A Study of the Housing and Homelessness Steering Committee in Ontario, Canada

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Homelessness, Health, and Integrated Care in Canada

For homeless individuals, integrated care may involve the coordination of housing, health care provision, and mental health and/or substance use supports.Integration is a coherent set of methods and models on the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical levels designed to create connectivity, alignment and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors. The goal of these methods and models is to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction and system efficiency for patients with complex, long-term problems cutting across multiple services, providers and settings. The result of such multi-pronged efforts to promote integration for the benefit of these special patient groups is called “integrated care”.[31]

…a recovery-oriented approach to homelessness that involves moving people who experience homelessness into independent and permanent housing as quickly as possible, with no preconditions, and then providing them with additional services and supports as needed. The underlying principle of Housing First is that people are more successful in moving forward with their lives if they are first housed.[33]

Social determinants of health should be central to mainstream discussions and funding decisions about health care. For many patients, a prescription for housing or food is the most powerful one that a physician could write, with health effects far exceeding those of most medications.[46]

3. Methodology

4. Health and Social Housing Sector Collaboration: Identifying Key Challenges

4.1. Legislative and Historical Differences

Initial public concerns focused on the word “integration” and what it meant for health service providers:CE-LHIN 2: I think when we started it, people were like, “Oh, here comes the next—or first—wave really of integration.” I have been through a few system integrations but it was always the planning entities in the province, and the LHIN was the necessary move to bring planning and funding accountability into one local body…But we did not know if it would stick through governments…It’s been three elections, at least, of provincial government that…it’s stuck through.

While some uncertainty remains, the CE-LHIN participants believed that their work is better understood and appreciated today than it had been previously:CE-LHIN 2: With the word “integration” in our name and that being a new term, there was a lot of discussion about, “What does that mean? Is that a merger? Amalgamation? Cease our service? What is that?” We spent a lot of our time in [the] early days explaining that, absolutely, that is part of the continuum of integration but partnerships, collaborations, transfers, mergers, amalgamations, stop service are all in the [LHSIA] as a continuum.

CE-LHIN 1: I think [the public] understand[s] what it means better. There’s still some providers that are very frightened by that. I think the fright comes from believing that they’re going to lose their service and their jobs. The opportunity that people see now, that perhaps we saw in the beginning, is the opportunity for the people that they serve. So whereas the planning used to be based on the service, it’s now based on the person being served and I think now that people see that, it’s kind of renewed the interests of some people who were working in the field.

SM 2: [The legislation and funding procedures identified within them are] overly complicated, I think at this point. And I think the root of the problem is that the devolution was done too quickly and there wasn’t enough consolidation at that point and there wasn’t enough faith in municipalities that they could do a good job and that may have been appropriate back in the day. Municipalities were terribly resistant to this [download].SM 3: It’s a very different world since download. There are a lot more procedures, a lot more things written down…certainly there were no service managers, that kind of collaboration between service managers to get things in place. It’s a lot more formal and written down, so that hopefully years and years from now, people won’t have to go, “Why did that happen?”SM 4: One of the interesting things about service managers, and our evolution, is when housing portfolio was downloaded there were a ton of people with lots of—20–30 years’—experience in housing delivery, provincial housing delivery program, that ended up in service manager positions across the province…So we rely on that expertise that is now imbedded within the service manager role to help create some information, fill the information gaps that sometimes all these young folk don’t have.

CE-LHIN 1: With the municipal lens, to a certain extent, we’re wandering into territory that we don’t really understand, as well as there’s some of those old wounds from other processes that we weren’t involved in that rear their heads in this process.SM 3: The province created the Consolidated Municipal service managers and the DSABs…So why, when they created the LHINs, didn’t they try and align that with the service managers? That was created by the province—the same province—so why didn’t they align it? Perhaps if they had aligned it, things would have evolved differently.SM 2: The geographic boundaries at the province have never been properly addressed. It’s a huge project, but the geographic boundaries are used by all ministries and they set up the province in different ways, and there ought to be an approach whereby we always know that we’re connected with these five other municipalities, whereas we’re not.

4.2. Accountability Structures

While the service managers all report to elected officials, they are each designed and operate independently from one another. One service manager representative stated:CE-LHIN 2: Our municipal partners have had to deal with downloads…They also are still having conversations with their municipal councils discussing the appropriateness of who delivers what, and we have similar conversations but the “who delivers what” and “who’s being asked to deliver what” is very at the forefront of their discussions.

SM 4: It’s a little bit different in every service manager…so it can be different in terms of the reporting. In terms of the broader goals and objectives and the things that we have to do, they’re the same because we’re falling under the same [legislation]. Just the nuance of council direction and priorities that are set out by those local councils and in terms of the internal arrangement and the reporting, that will be different based on what the infrastructure is within the level of government because we’re regional governments.

4.3. Priorities and Roles

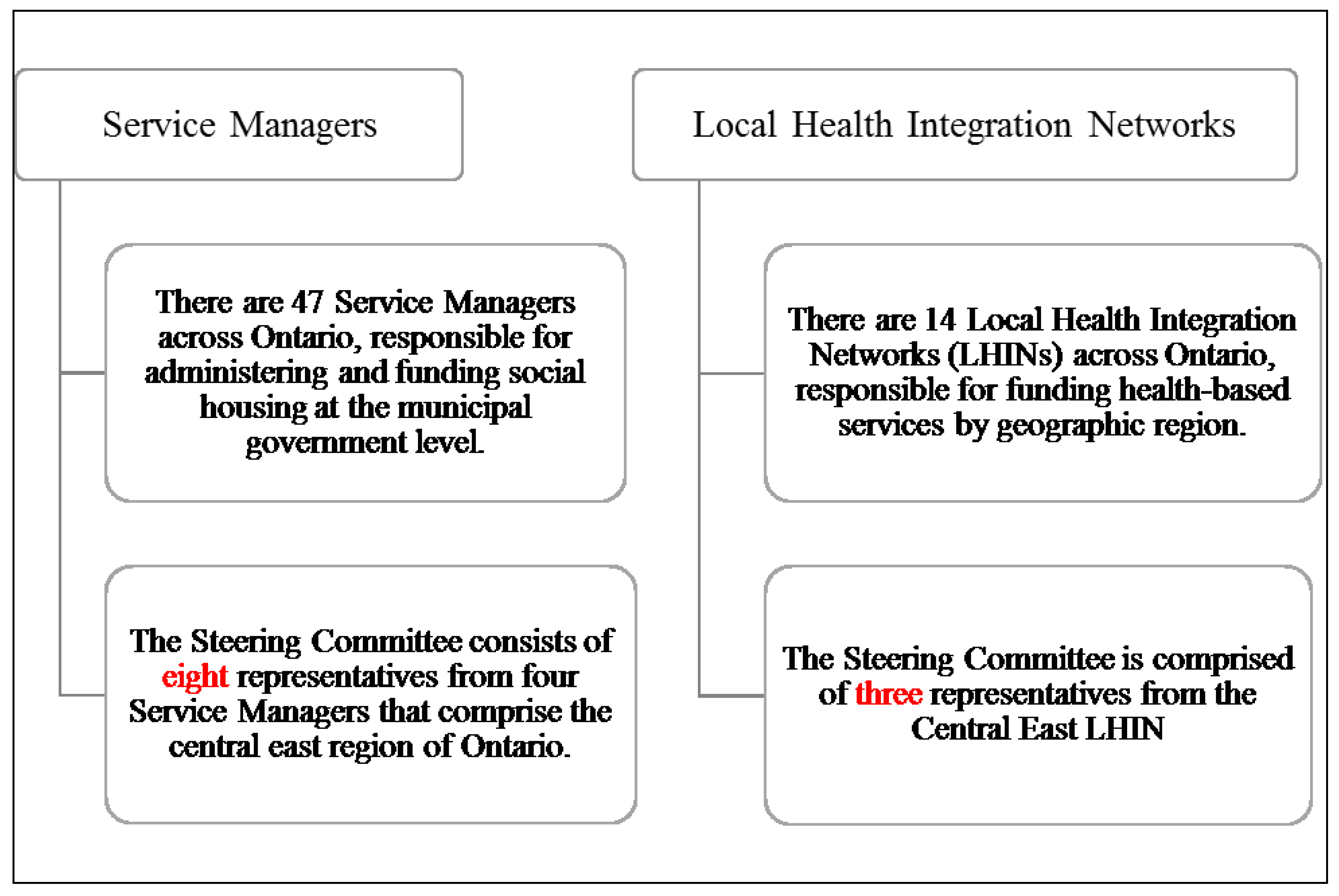

Beyond the different roles, as administrators and/or funders, the Steering Committee members also bring to the table their unique positions and priorities. In particular, the CE-LHIN interest extends broadly across the central east region of Ontario, while service managers are concerned with their individual municipalities. As a planning table, the differently aligned interests of the parties emerged as a notable challenge that needed to be considered and addressed. The difference in priorities was noted by CE-LHIN and service manager interview participants:SM 5: There’s an interesting kind of dynamic, in my opinion, in that [service managers] are immersed in our community and we have community partners that we’re trying to do this work with, but we have a dual role of we are providing service and we are funding service and the LHIN has only the role of funding service. But, at least in this forum we are able to talk funder to funder.

Entering into a collaborative Steering Committee with different roles and service area priorities was a challenge that service managers and the CE-LHIN had to collectively address and attempt to overcome.CE-LHIN 2: [service manager] interests are most directed to their own. They’re less interested in knowing what another municipality has. We’re very interested to know how the different municipalities are using similar pots of money. That’s not so much their concern, other than sometimes if it’s problem solving for them.SM 4: There’s one LHIN and then there’s the service managers, which are multiples…And so what we’re trying to do is create some more, better balance in the system across the communities but we’re still coming at it from a service manager perspective. We’re coming at this from our individual service managers and not one-to-one…We’re not coming at it as service manager/LHIN. We’re coming at it from service managers and LHIN, which must make it very difficult for them because they’re the ones trying to do the balance…I think that’s an important piece of the structure, that it’s 4:1.

5. Working through Key Challenges: Drafting a Guiding Framework Document

CE-LHIN 2: I’d say the time spent up-front in getting the agreement on guiding principles, and it is a long time, but…it’s good time spent. Now we haven’t had full fruition of that but I believe that it was good time spent, particularly because these are new partners to one table and we’re new. I think we just needed to allow that time. Another learning would be, and again we haven’t seen it to fruition but, putting forward a common strategic aim for the group...This is the approach we take and that’s an objective, a common goal…a statement we can take out and show people.

5.1. Legislative and Historical Differences

CE-LHIN 2: …integration was and is, I would say still, a very foreign term but our municipal partners are more uneasy with the term integration. Similar to how our service providers might have felt in the beginning around the term integration, in understanding it, because we had to spend a lot of time explaining. There was even a suggestion early on at the Steering Committee table that we not use the word integration. We couldn’t agree to that but we can define it other ways.

5.2. Accountability Structures

5.3. Priorities and Roles

The Steering Committee will adopt a consensus model of decision-making for recommendations/advice. As such, deliberations will seek to build consensus on the most acceptable advice/direction considering the best interests of residents. Where consensus cannot be reached, the Steering Committee will present a summary of the deliberations to their respective Sponsors for input and direction [60].

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nigel Keohane. A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Englan. Local Leadership, New Approaches: How New Ways of Working Are Helping to Improve the Health of Local Communities. London: Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Regional Municipality of Durham. At Home in Durham: Durham Region Housing Plan 2014–2024. Whitby: The Regional Municipality of Durham, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- City of Kawartha Lakes. Building Strong Communities: Housing and Homelessness Plan 2014–2023. Lindsay: City of Kawartha Lakes, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Northumberland County. Northumberland Housing and Homelessness Plan 2014–2023. Cobourg: Northumberland County, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- City of Peterborough. Peterborough: 10-Year Housing and Homelessness Plan 2014–2024. Peterborough: City of Peterborough, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Charles J. Frankish, Stephen W. Hwang, and Darryl Quantz. “Homelessness and health in Canada: Research lessons and priorities.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 96 (2005): S23–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stephen W. Hwang. “Homelessness and health.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 164 (2001): 229–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Katharine Kelly, and Tullio Caputo. “Health and street/homeless youth.” Journal of Health Psychology 12 (2007): 726–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alistair Story. “Slopes and cliffs in health inequities: Comparative morbidity of housed and homeless people.” The Lancet 382 (2013): S93. [Google Scholar]

- Isolde Daiski. “Perspectives of homeless people on their health and health needs priorities.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 58 (2007): 273–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen Hwang, Tim Aubry, Anita Palepu, Susan Farrell, Rosane Nisenbaum, Anita Hubley, Fran Klodawsky, Evie Gogosis, Elizabeth Hay, Shannon Pidlubny, and et al. “The health and housing in transition study: A longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities.” International Journal of Public Health 56 (2011): 609–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristy Buccieri, and Stephen Gaetz. Facing FAQs: H1N1 and Homelessness in Toronto. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen W. Hwang, Angela Colantonio, Shirley Chiu, George Tolomiczenko, Alex Kiss, Laura Cowan, Donald A. Redelmeier, and Wendy Levinson. “The effect of traumatic brain injury on the health of homeless people.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 179 (2008): 779–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jane Topolovec-Vranic, Naomi Ennis, Angela Colantonio, Michael D. Cusimano, Stephen W. Hwang, Pia Kontos, Donna Ouchterlony, and Vicky Stergiopoulos. “Traumatic brain injury among people who are homeless: A systematic review.” BMC Public Health 12 (2012): 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafael L.F. Figueiredo, Stephen W. Hwang, and Carlos Quiñonez. “Dental health of homeless adults in Toronto, Canada.” Journal of Public Health Dentistry 73 (2013): 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen Gaetz, Valerie Tarasuk, Naomi Dachner, and Sharon Kirkpatrick. “‘Managing’ homeless youth in Toronto: Mismanaging food access and nutritional well-being.” Canadian Revue of Social Policy 58 (2006): 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Valerie Tarasuk, Naomi Dachner, Blake Poland, and Stephen Gaetz. “Food deprivation is integral to the ‘hand to mouth’ existence of homeless youths in Toronto.” Public Health Nutrition 12 (2009): 1437–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheryl Forchuk, Rick Csiernik, and Elsabeth Jensen. Homelessness, Housing, and Mental Health: Finding Truths—Creating Change. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ami Rokach. “Private lives in public places: Loneliness of the homeless.” Social Indicators Research 72 (2005): 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle N. Grinman, Shirley Chiu, Donald A. Redelmeier, Wendy Levinson, Alex Kiss, George Tolomiczenko, Laura Cowan, and Stephen W. Hwang. “Drug problems among homeless individuals in Toronto, Canada: Prevalence, drugs of choice, and relation to health status.” BMC Public Health 94 (2010): 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maritt Kirst, Tyler Frederick, and Patricia G. Erickson. “Concurrent mental health and substance use problems among street-involved youth.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 9 (2011): 543–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne M. Gadermann, Anita M. Hubley, Lara B. Russell, and Anita Palepu. “Subjective health-related quality of life in homeless and vulnerably housed individuals and its relationship with self-reported physical and mental health status.” Social Indicators Research 116 (2014): 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuck K. Wen, Pamela L. Hudak, and Stephen W. Hwang. “Homeless people’s perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters.” Journal of the Society of General Internal Medicine 22 (2007): 1011–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernadette Pauly. “Close to the street: Nursing practice with people marginalized by homelessness and substance use.” In Homelessness and Health in Canada. Edited by Manal Guirguis-Younger, Ryan McNeil and Stephen W. Hwang. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2014, pp. 211–32. [Google Scholar]

- Vanessa Oliver, and Rebecca Cheff. “Sexual health: The role of sexual health services among homeless young women living in Toronto, Canada.” Health Promotion Practice 13 (2012): 370–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristy Buccieri, and Stephen Gaetz. “Ethical vaccine distribution planning for pandemic influenza: Prioritizing homeless and hard-to-reach populations.” Public Health Ethics 6 (2013): 185–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen R. Poulin, Marcella Maguire, Stephen Metraux, and Dennis P. Culhane. “Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: A population-based study.” Psychiatric Services 61 (2010): 1093–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Harris Ali. “Tuberculosis, homelessness, and the politics of mobility.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 19 (2010): 80–107. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen W. Hwang, Alex Kiss, Minnie M. Ho, Cheryl S. Leung, and Adi V. Gundlapalli. “Infectious disease exposures and contact tracing in homeless shelters.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 19 (2008): 1163–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis L. Kodner, and Cor Spreeuwenberg. “Integrated care: Meaning, logic, applications, and implications—A discussion paper.” International Journal of Integrated Care 2 (2002): e12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deborah K. Padgett, Benjamin J. Henwood, and Sam J. Tsemberis. Housing First: Ending Homelessness, Transforming Systems and Changing Lives. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Gaetz, Fiona Scott, and Tanya Gulliver. Housing First in Canada: Supporting Communities to End Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paula Goering, Scott Veldhuizen, Aimee Watson, Carol Adair, Brianna Kopp, Eric Latimer, and Tim Aubry. National Final Report: Cross-Site at Home/Chez Soi Project. Calgary: Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Suzanne Zerger, Katherine Francombe Pridham, Jeyagobi Jeyaratnam, Stephen W. Hwang, Patricia O’Campo, Jaipreet Kohli, and Vicky Stergiopoulos. “Understanding housing delays and relocations within the Housing First model.” The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 43 (2016): 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzanne Swanton. “Social Housing Wait Lists and the One-Person Household in Ontario.” Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Natalie Waldbrook. “Exploring opportunities for healthy aging among older persons with a history of homelessness in Toronto, Canada.” Social Science & Medicine 128 (2015): 126–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen W. Hwang, and Tom Burns. “Health interventions for people who are homeless.” Lancet 384 (2014): 1541–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle Patterson, Akm Moniruzzaman, Anita Palepu, Denise Zabkiewicz, Charles J. Frankish, Michael Krausz, and Julian M. Somers. “Housing first improves subjective quality of life among homeless adults with mental illness: 12-Month findings from a randomized control trial in Vancouver, British Columbia.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48 (2013): 1245–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen W. Hwang, Evie Gogosis, Catharine Chambers, James R. Dunn, Jeffrey S. Hoch, and Tim Aubry. “Health status, quality of life, residential stability, substance use, and health care utilization among adults applying to a supportive housing program.” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 88 (2011): 1076–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angela Russolillo, Michelle Patterson, Lawrence McCandless, Akm Moniruzzaman, and Julian Somers. “Emergency department utilisation among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders after one year of housing first interventions: A randomised controlled trial.” International Journal of Housing Policy 14 (2014): 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritt Kirst, Suzanne Zerger, Vachan Misir, Stephen Hwang, and Vicky Stergiopoulos. “The impact of a housing first randomized controlled trial on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 146 (2015): 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eric Macnaughton, Ana Stefancic, Geoffrey Nelson, Rachel Caplan, Greg Townley, Tim Aubry, Scott McCullough, Michelle Patterson, Vicky Stergiopoulos, Catherine Vallée, and et al. “Implementing housing first across sites and over time: Later fidelity and implementation evaluation of a pan-Canadian multi-site housing first program for homeless people with mental illness.” American Journal of Community Psychology 55 (2015): 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennifer S. Volk, Tim Aubry, Paula Goering, Carol E. Adair, Jino Distasio, Jonathan Jetté, Danielle Nolin, Vicky Stergiopoulos, David L. Streiner, and Sam Tsemberis. “Tenants with additional needs: When housing first does not solve homelessness.” Journal of Mental Health 3 (2015): 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan McNeil, Manal Guirguis-Younger, Laura B. Dilley, Jeffrey Turnbull, and Stephen W. Hwang. “Learning to account for the social determinants of health affecting homeless persons.” Medical Education 47 (2013): 485–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly M. Doran, Elizabeth J. Misa, and Nirav R. Shah. “Housing as healthcare—New York’s boundary-crossing experiment.” New England Journal of Medicine 369 (2013): 2374–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebecca Onie, Paul Farmer, and Heidi Behforouz. “Realigning health with care: Lessons in delivering more with less.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 10 (2012): 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Carol Wilkins. “Connecting permanent supportive housing to hear care delivery and payment systems: Opportunities and challenges.” American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 18 (2015): 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline Abrahams. “Caring for an ageing population.” In A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. Edited by Nigel Keohane. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015, pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Bowden. “Joining up health and care to meet each person’s needs—A provider’s perspective to being patient-centred.” In A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. Edited by Nigel Keohane. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015, pp. 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jeremy Hughes. “Apart at the seams: The challenge of integrating dementia care.” In A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. Edited by Nigel Keohane. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015, pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sir John Oldham. “Collective commissioning.” In A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. Edited by Nigel Keohane. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015, pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tim Kelsey. “Unleashing the power of people: Why transparency and participation can transform health and care services.” In A Problem Shared? Essays on the Integration of Health and Social Care. Edited by Nigel Keohane. London: The Social Market Foundation, 2015, pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dorothy Smith. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Oxford: AltaMira Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sandra Kirby, Lorraine Greaves, and Colleen Reid. Experience Research Social Change: Methods beyond the Mainstream, 2nd ed. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario. “Local Health System Integration Act 2006 (ON) c. 4.” Available online: http://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/06l04 (accessed on 20 November 2015).

- Housing Services Corporation. Canada’s Social and Affordable Housing Landscape: A Province-to-Province Overview. Toronto: Housing Services Corporation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. “Social Housing Reform Act 2000 (ON) c. 27.” Available online: http://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/00s27 (accessed on 20 November 2015).

- Government of Ontario. “Housing Services Act 2011 (ON) c. 6.” Available online: http://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/11h06 (accessed on 20 November 2015).

- Kristy Buccieri. Ethnography of the Central East Health, Housing, and Homelessness Steering Committee. Report and Toolkit. Toronto: Homeless Hub, 2015, pp. 44, 45, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buccieri, K. Integrated Social Housing and Health Care for Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals: A Study of the Housing and Homelessness Steering Committee in Ontario, Canada. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5020015

Buccieri K. Integrated Social Housing and Health Care for Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals: A Study of the Housing and Homelessness Steering Committee in Ontario, Canada. Social Sciences. 2016; 5(2):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5020015

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuccieri, Kristy. 2016. "Integrated Social Housing and Health Care for Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals: A Study of the Housing and Homelessness Steering Committee in Ontario, Canada" Social Sciences 5, no. 2: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5020015

APA StyleBuccieri, K. (2016). Integrated Social Housing and Health Care for Homeless and Marginally-Housed Individuals: A Study of the Housing and Homelessness Steering Committee in Ontario, Canada. Social Sciences, 5(2), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci5020015