Hierarchical and Non-Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Clustering Methods to “Shakespeare Authorship Question”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Shakespeare’s writing style differs from one work to another in terms of divergent vocabulary use and different sentence structures. The copresence of more unrelated writing styles in Shakespeare’s works gives each an enhanced force as indicators of different author or multiple authors.

- (2)

- If Shakespeare had written all the plays, poems, and sonnets traditionally attributed to him, he would never have had time to keep his career as a businessman and landowner.

- (3)

- A documentary record fails to show that Shakespeare attended grammar school or received knowledge in classical literature and rhetoric. Based on this, the works attributed to Shakespeare were in a literary style and this indicates that these works were written by a person capable of a high literary style not by a person of only moderate or lacked education.

- (4)

- A documentary record in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries also fails to show Shakespeare as a playwright or poet. Rather, that evidence shows only that his career is a businessman and real-estate landlord, and this means that there is no explicit evidence in Shakespeare’s life connecting him to any of the plays and sonnets attributed to him.

- (1)

- The historical record of Shakespeare attests to the fact that Shakespeare authored 38 plays, 154 sonnets, and 5 poems. These works bear Shakespeare’s name which had explicit evidence and historical validity from Shakespeare’s own time. Much of this evidence comes either from “public sources, such as many title pages of plays and poems published in his lifetime, and references in works by other writers such as Francis Meres, who in 1598 named Shakespeare as the author of twelve plays, and John Weever, who wrote a poem addressed to Shakespeare” or from “manuscript sources, such as references in accounts of court performances, many entries in the Stationers’ Register (a volume in which publishers and printers were required to register the works they intended to publish), a note about Hamlet by the writer Gabriel Harvey, and William Drummond’s notes of his private conversations with Ben Jonson” [21].

- (2)

- There are no documents explicitly suggesting someone else wrote Shakespeare’s works. The only evidence on this question is that “the Shakespeare who wrote the plays was the man of Stratford-upon-Avon is provided by his monument in Holy Trinity Church, which compares the man of Stratford with great figures of antiquity, by Ben Jonson’s verses in the First Folio, which call him the, ‘sweet swan of Avon’, and, also in the Folio, by verses by Leonard Digges, which refer to his ‘Stratford monument’”. There is also much indirect evidence like the fact that “visitors to Stratford during the seventeenth century sought to learn more about its most famous former inhabitant” [21].

- (3)

- Interpreting the historical and biographical information about Shakespeare for evidence to reject his authorship to the advantage of another author(s) is a much contested one at the time. Mere evidence with a biographical interpretation of literature is not a marker to attribute authorship.

2. Authorship Attribution

2.1. Stylometry

- ●

- Despite a very large number of proposed stylistic criteria, there is little agreement on which are valid, and

- ●

- Similarly, there is little agreement on which quantitative analytical methods give the most useful and reliable results, and there is again very little work on formal assessment of their validity.

2.2. Previous Stylometric Works on the Shakespeare Authorship Question

- (1)

- Shakespeare was responsible for the writing of the early plays traditionally attributed to him. At the same time, the impact of Bacon and Marlowe on Shakespeare’s writings during this stage of his career as a playwright is very significant.

- (2)

- Sir Francis Bacon was not likely to have written Shakespeare’s plays.

- (3)

- Marlowe did have an enormous influence on Shakespeare’s works; while he is not the creator of the whole Shakespeare’s oeuvre, his contribution is seriously considered. In other words, Edward III, Henry VI trilogy, Richard II, and Richard III, or major part of them, are likely to have been written by Marlowe.

- (4)

- John Fletcher was likely to have written Henry VIII or even contributed to it. The possibility of Fletcher’s involvement in helping Shakespeare to write some other plays was not ruled out.

3. Methodology

3.1. Corpus

- ●

- Dido, Queen of Carthage, is at best a collaboration between Christopher Marlowe and Thomas Nashe, though scholars have typically sought to limit Nashe’s involvement. It is therefore, at the least, a contested play and cannot be used to generate Marlowe’s profile.

- ●

- Doctor Faustus exists in two early versions (1604 and 1616), both printed long after Marlowe’s death and known to have been subjected to revision by other hands (Henslowe’s Diary records payments made for them). It is therefore not exclusively Marlowe’s, and cannot be included to generate his authorial profile.

- ●

- The Jew of Malta was printed in 1633, long after Marlowe’s death, because it was revived for Caroline performance. The 1633 quarto includes two prologues and an epilogue added by Thomas Heywood, and unclear whether further revisions were made to Marlowe’s text. Even if the prologues and epilogue are removed, the authenticity of the text remains in doubt.

- ●

- Thomas Kyd’s authorship of Arden of Faversham is far from conclusive. The general scholarly consensus is that Shakespeare is responsible for a sizeable amount, if not the entirety, of the play. Kyd and Marlowe are other likely candidates for collaborators. Kyd’s authorship of 1 Hieronimo is equally contentious.

- ●

- Cymbeline was first printed in 1623 and setting information (such as “in the garden of Cymbeline’s palace”), not evident in the early texts, was typically added to the nineteenth century editions of Shakespeare.

- ●

- Hamlet, King Lear, Richard III, and Titus Andronicus are not disputed. These are all Shakespeare’s canonical works. Titus is a collaboration with George Peele.

| No. | Author & Work Title | Code |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr1 |

| 2 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr2 |

| 3 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr3 |

| 4 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr4 |

| 5 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr5 |

| 6 | Translations of the philosophical works | BaconTr6 |

| 7 | F. Bacon from the tower of London pleads for mercy with King James | BaconLet |

| 8 | The history of the reign of King Henry the seventh | Bacon Henry1 |

| 9 | The history of the reign of King Henry the seventh | Bacon Henry2 |

| 10 | John Fletcher-Rule a wife | Fletwife |

| 11 | John Fletcher—The Faithful Shepherdess | FletFaithful |

| 12 | John Fletcher—The Humorous Lieutenant | FletLieutenant |

| 13 | John Fletcher—The Tragedy of Bonduca | FletBonduca |

| 14 | John Fletcher—The Wild Goose Chase | FletChase |

| 15 | John Fletcher—The Woman’s Prize | FletPrize |

| 16 | John Fletcher—Wit Without Money | FletMoney |

| 17 | Christopher Marlowe—Dido, Queen of Carthage | MarDido |

| 18 | Christopher Marlowe—Edward II | MarEdward |

| 19 | Christopher Marlowe—The tragedy of Dr. Faustus | MarFaust |

| 20 | Christopher Marlowe—The Jew of Malta | MarMalta |

| 21 | Christopher Marlowe—Massacre at Paris | MarMassacre |

| 22 | Christopher Marlowe—Tamburlaine, Part 1 | MarTamb1 |

| 23 | Christopher Marlowe—Tamburlaine, Part 2 | MarTamb2 |

| 24 | William Shakespeare—Cymbeline, King of Britain | ShaCymbeline |

| 25 | William Shakespeare—History of Henry IV, Part I | ShaHenry1 |

| 26 | William Shakespeare—History of Henry IV, Part II | ShaHenryII |

| 27 | William Shakespeare—History of Henry V | ShaHenryIII |

| 28 | William Shakespeare—History of King John | ShaKing |

| 29 | William Shakespeare—History of Richard II | ShaRichard |

| 30 | Thomas Kyd—Arden of Feversham | ThoArden |

| 31 | Thomas Kyd—Ieronimo | ThoIeronimo |

| 32 | Thomas Kyd—The tragedy of Soliman and Perseda | ThoPerseda |

| 33 | Thomas Kyd—The Spanish Tragedie | ThoSpanish |

| 34 | Disputed—King Edward | DisEdward |

| 35 | Disputed—The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark | DisHamlet |

| 36 | Disputed—History of Henry VI, Part I | DisHenryI |

| 37 | Disputed—History of Henry VI, Part II | DisHenry2 |

| 38 | Disputed—History of Henry VI, Part III | DisHenryIII |

| 39 | Disputed—History of Henry VIII | DisHenry8 |

| 40 | Disputed—The Tragedy of King Lear | DisLear |

| 41 | Disputed—Richard III | DisRichard |

| 42 | Disputed—Titus Andronicus | DisTitus |

3.2. Stylistic Criteria: Function Words, Word N-Grams, and Character N-Grams

- (1)

- Which stylistic criteria should be selected to describe the texts?

- (2)

- Which analytical method(s) should be used to analyze these texts on the basis of the selected stylistic criteria? The second question will be dealt with in Section 3.3.3.

3.3. Data Representation and Vector Space Model

3.3.1. Dimensionality Reduction

| Function words |

|---|

| the of i you and my he in me a to which was your that thou her thy thee ye it or as which so this be not in on why thus yet only soon still both us who how such all with him be by for have will she our shall do what had o but not then now |

| Words bi-grams |

|---|

| and now- and with- and so- of that- of thy- with thy- on thee- in he-to my-and that- and a- ye to- of the- from he- but to- a- in our- of it- yet i- with us-me and- not to- in all- me and-as it- to he-but that-it to-that by- and as |

| Character tri-grams |

|---|

| sti- uch- our- thr- men- tin- upo- ate- are- may- all- wel- ful- low-ity- uth-any-you-but- ady- day-now-nor-new-ton-can- tre-ndi- tur- ide- ond- nto- sen-giv-red-ery-ord-not-fou |

3.3.2. Text Length Normalization

3.3.3. Cluster Analysis Methods

- (1)

- In the current application, the function that generated DFW, Dbigram, and Dtrigram may not be known, and the strong suspicion must be that the generating function was nonlinear, but this is not certain. Even if the generating function is nonlinear, however, there is no guarantee that every data set it generates will contain non-linearities. In general, data that contains significant non-linearity must be analyzed using a nonlinear clustering method; use of a linear method in such a case misrepresents the structure of the data to greater or lesser degrees, depending on the nature of the non-linearity. In a linear method, the distance between two points in a space is taken to be the length of the straight line joining the points, or some approximation to it, whereas in a non-linear method, the distance between the two points is the length of the shortest line joining them along the surface of the curved-surface and where this line can but need not be straight. Depending on the amount of curvature, the difference between the two measures can be significant, and can therefore significantly affect analysis based on it. Given the difficulty of determining the presence of non-linearity in high-dimensional data and given also the implications of non-linearity for the present analysis cannot be ignored, and because hierarchical methods are linear, the additional method or methods used must be non-linear to take account of non-linearity and accommodate the possibility that the DFW, Dbigram, and Dtrigram contain significant non-linearities [33].

- (2)

- It is recognized that a single class of methods cannot safely be relied on [34,54], and that at least one additional method or class of methods must be used to corroborate the results from hierarchical analysis. Given that we selected a hierarchical method, the additional method or methods used must be non-hierarchical. Each clustering method provides a different mathematical view of what constitutes a cluster and how clusters can be identified, and interprets such agreement as was found among them as an indication of the intrinsic or “true” structure of the data. Specifically, we attempted to establish the validity of cluster results by applying a variety of different clustering methods to the same data and to compare the results: a clear convergence on one particular cluster structure was held to support the validity of that structure with respect to the data.

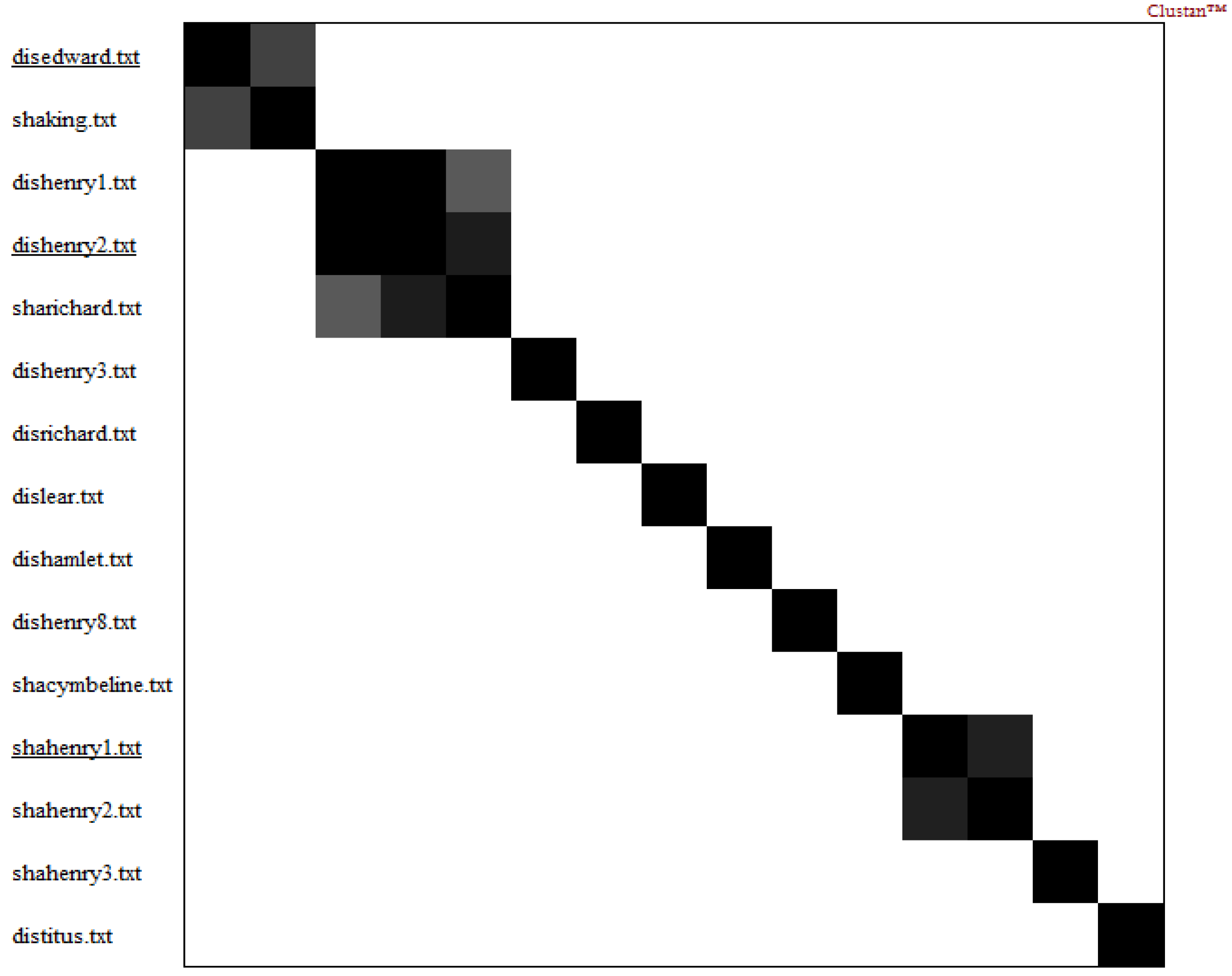

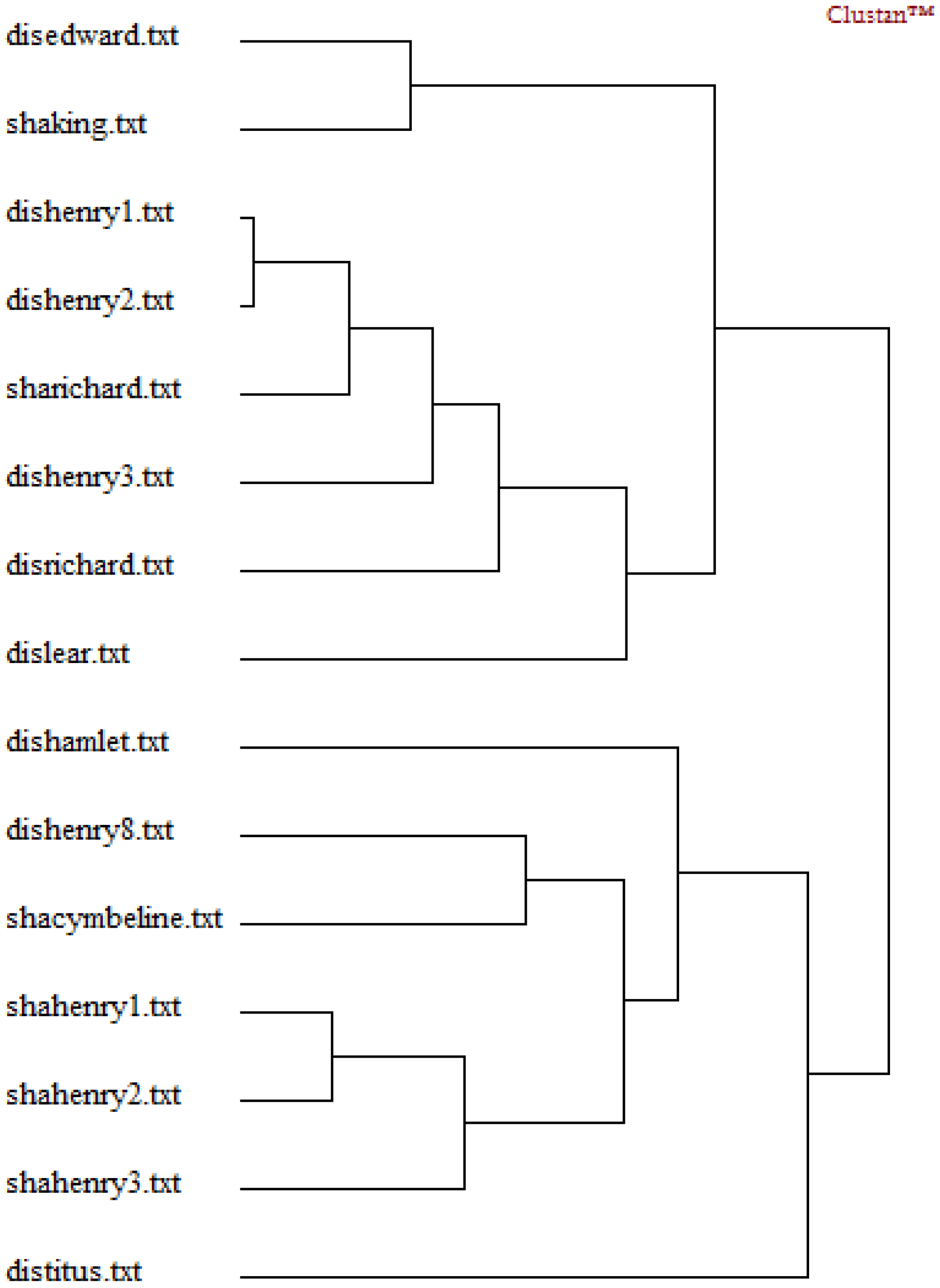

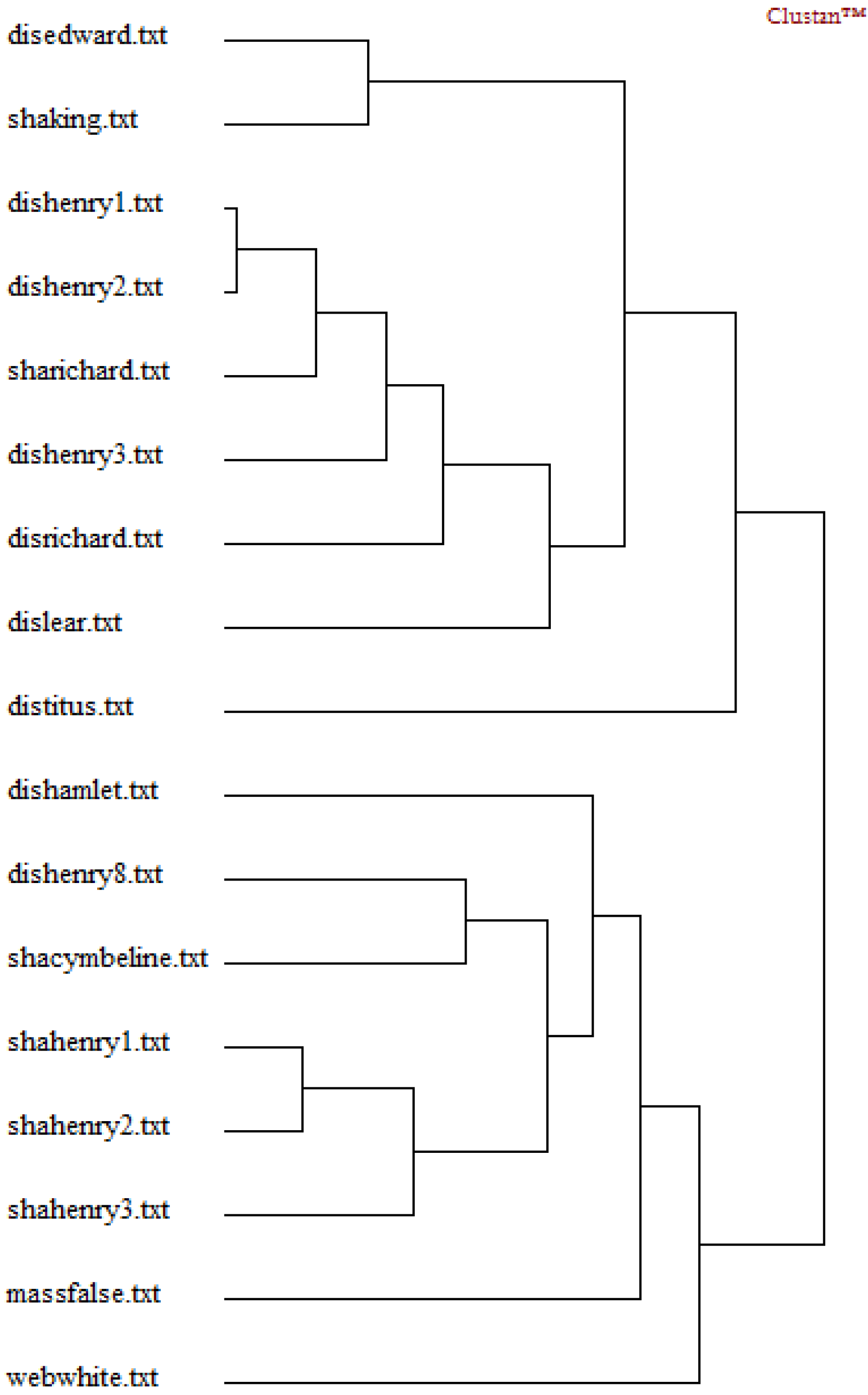

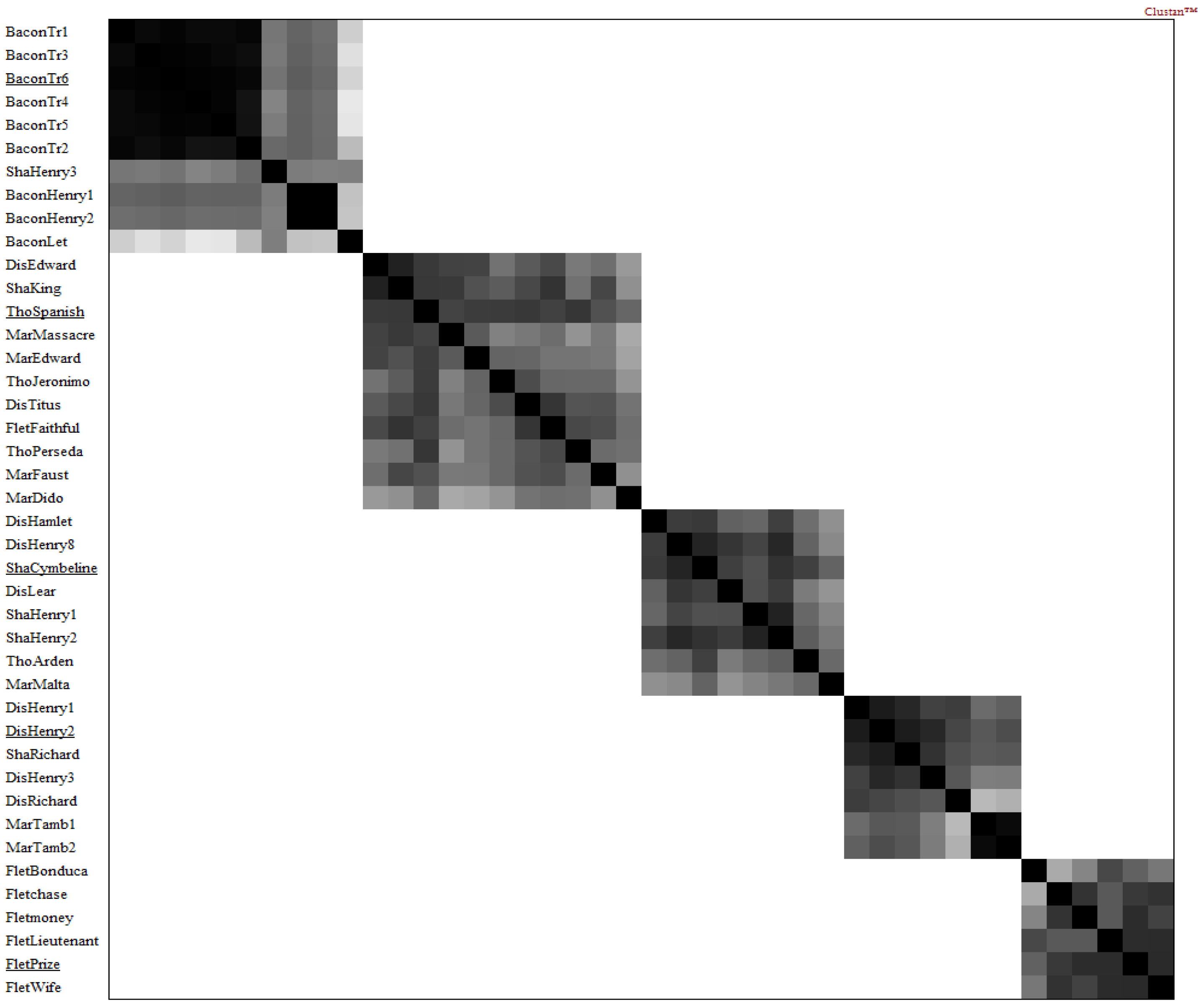

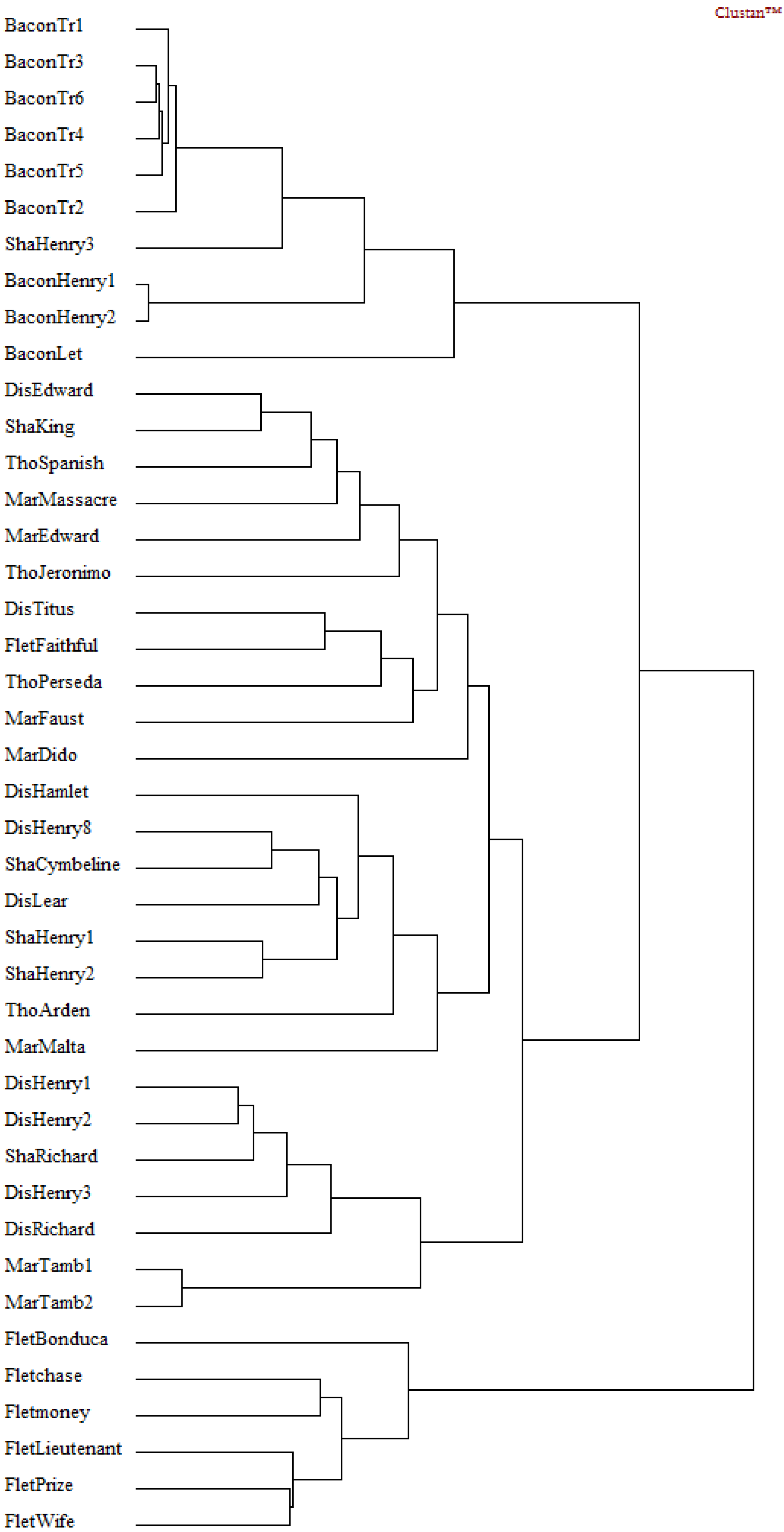

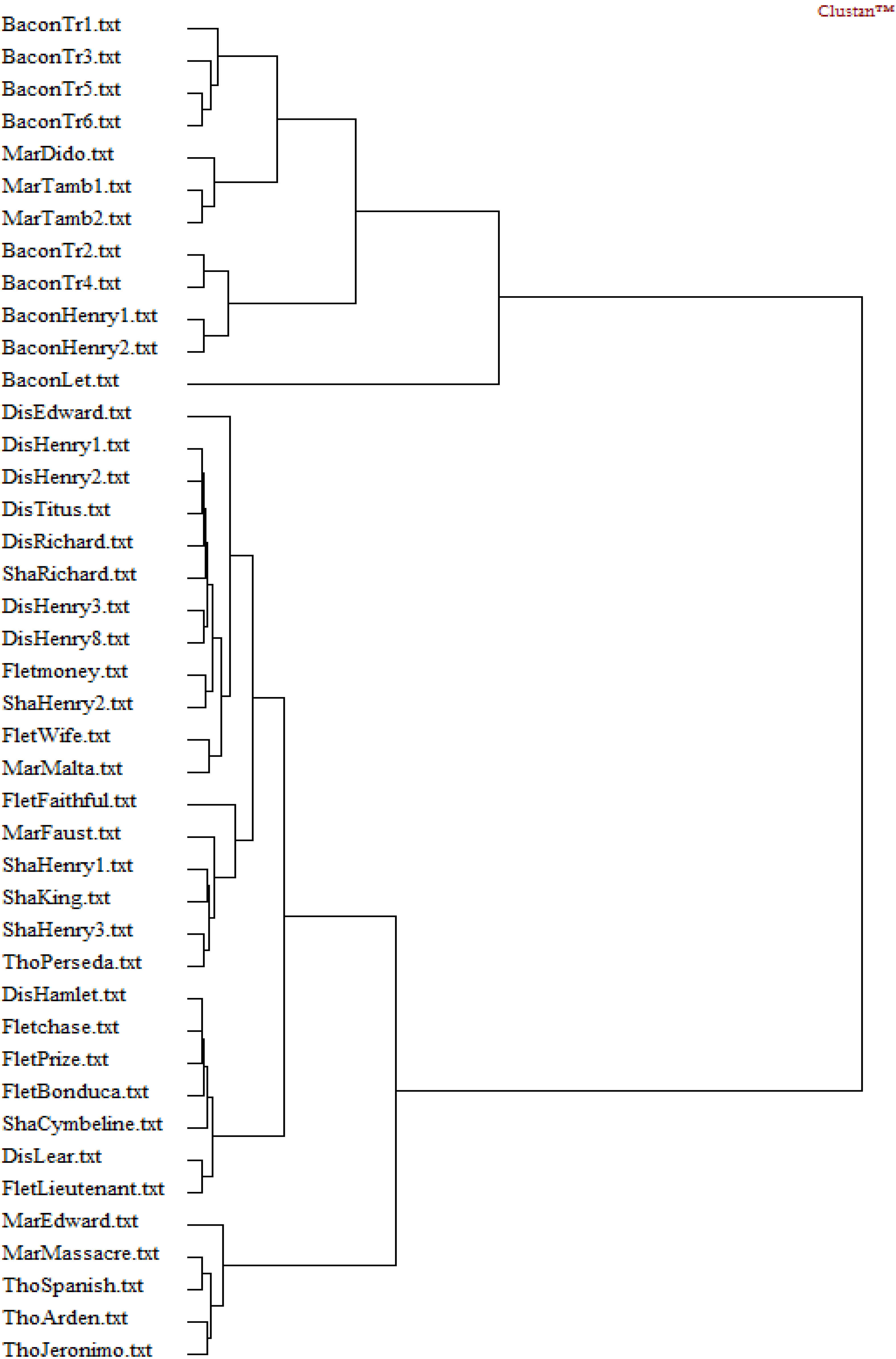

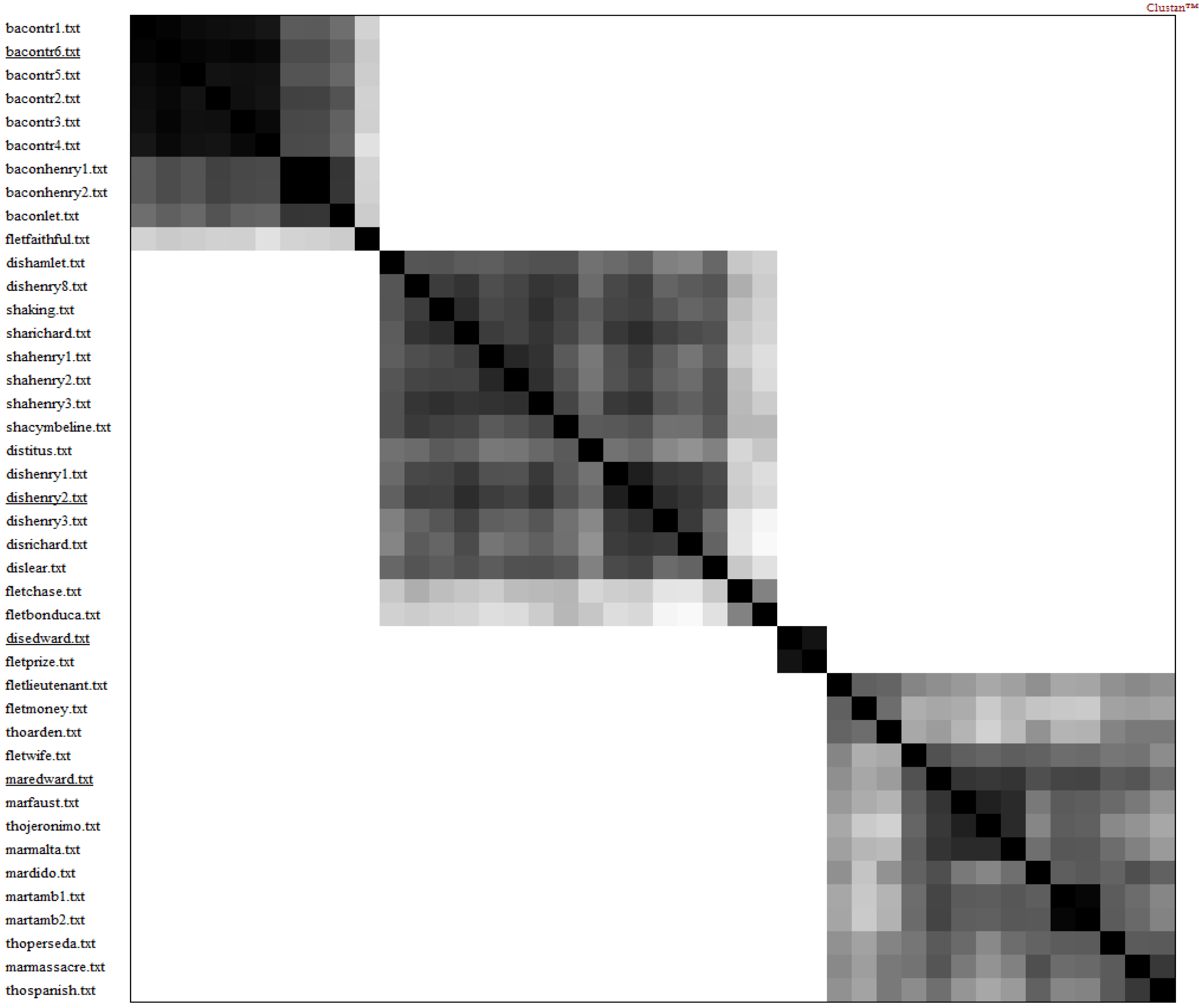

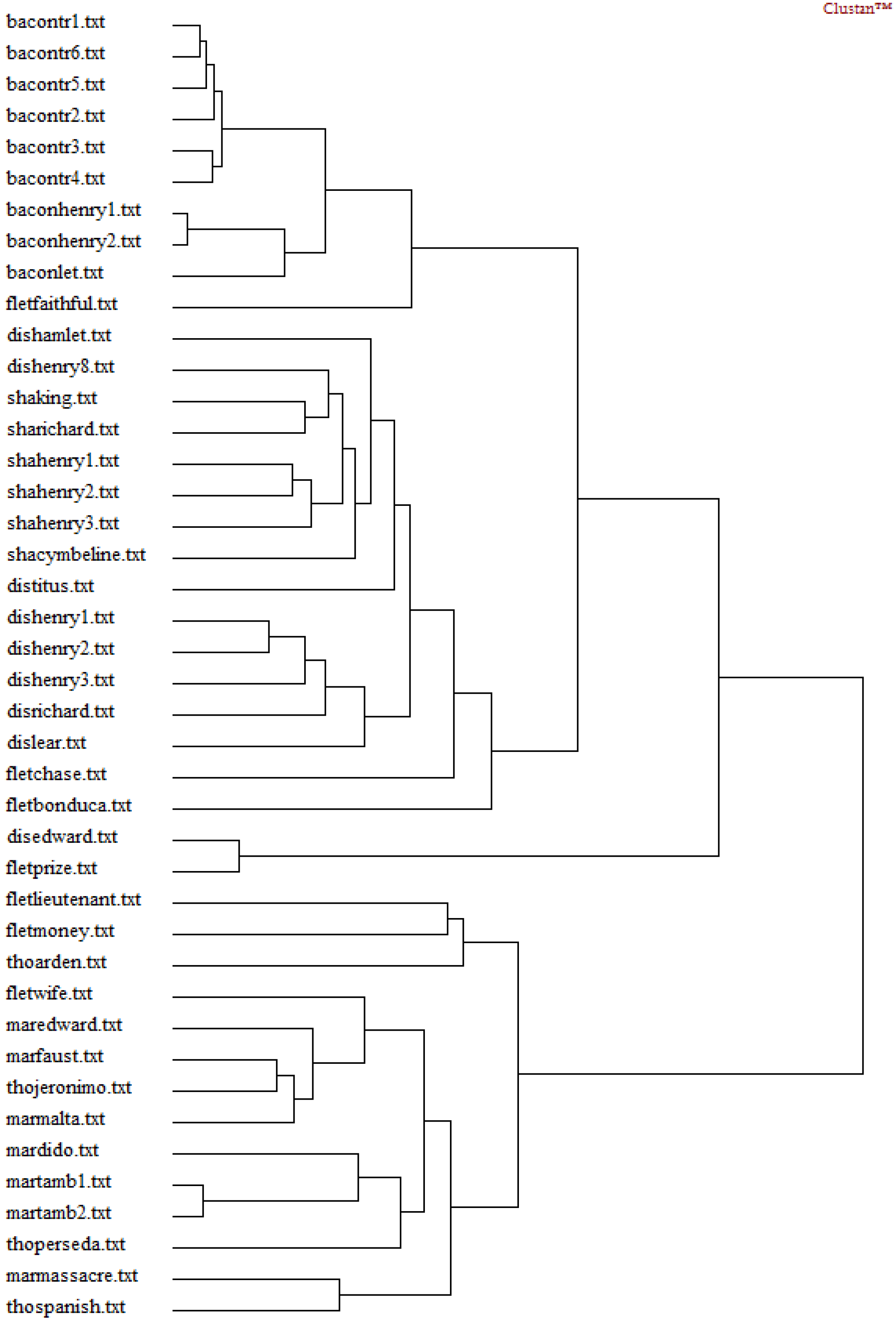

Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

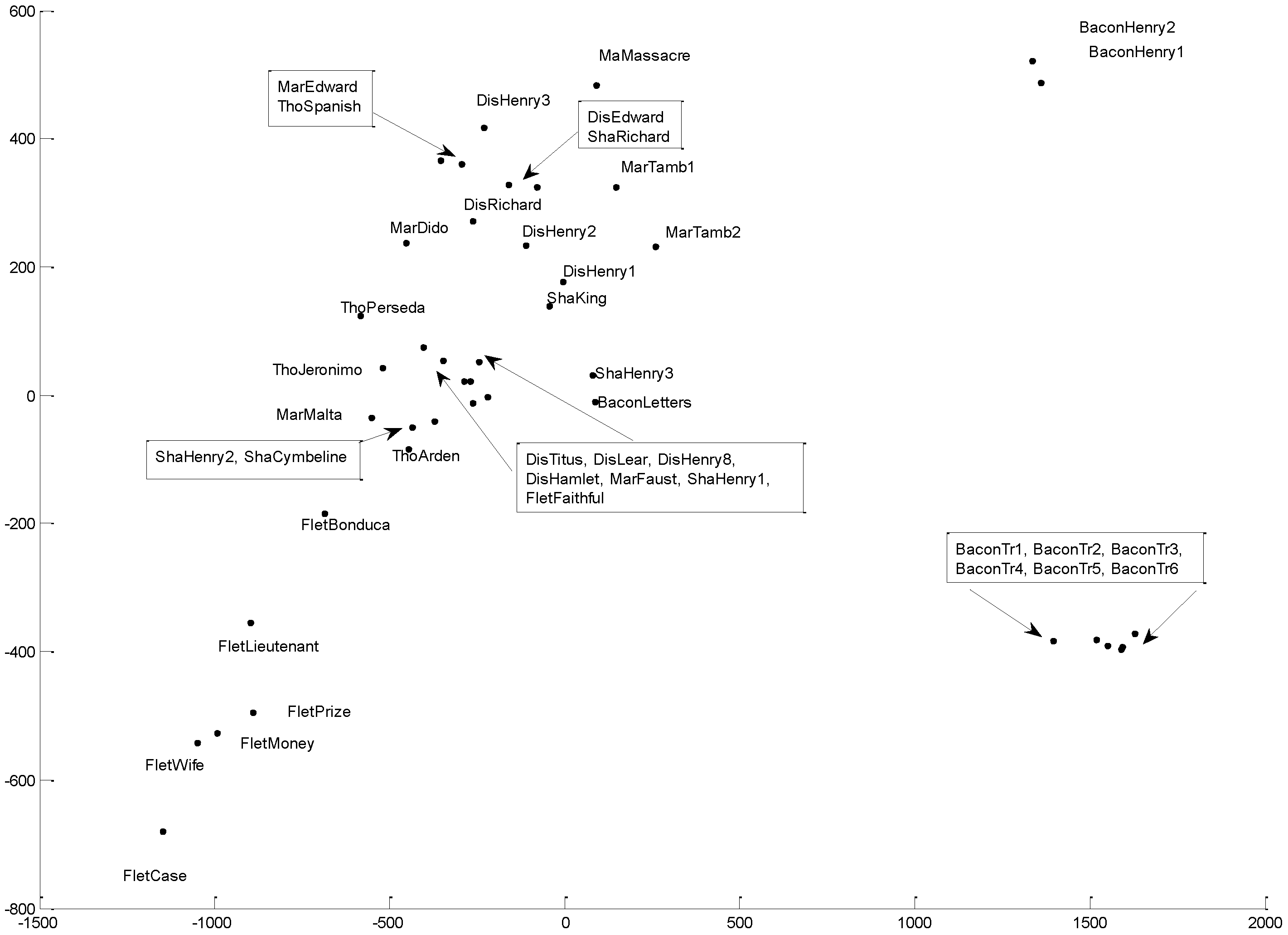

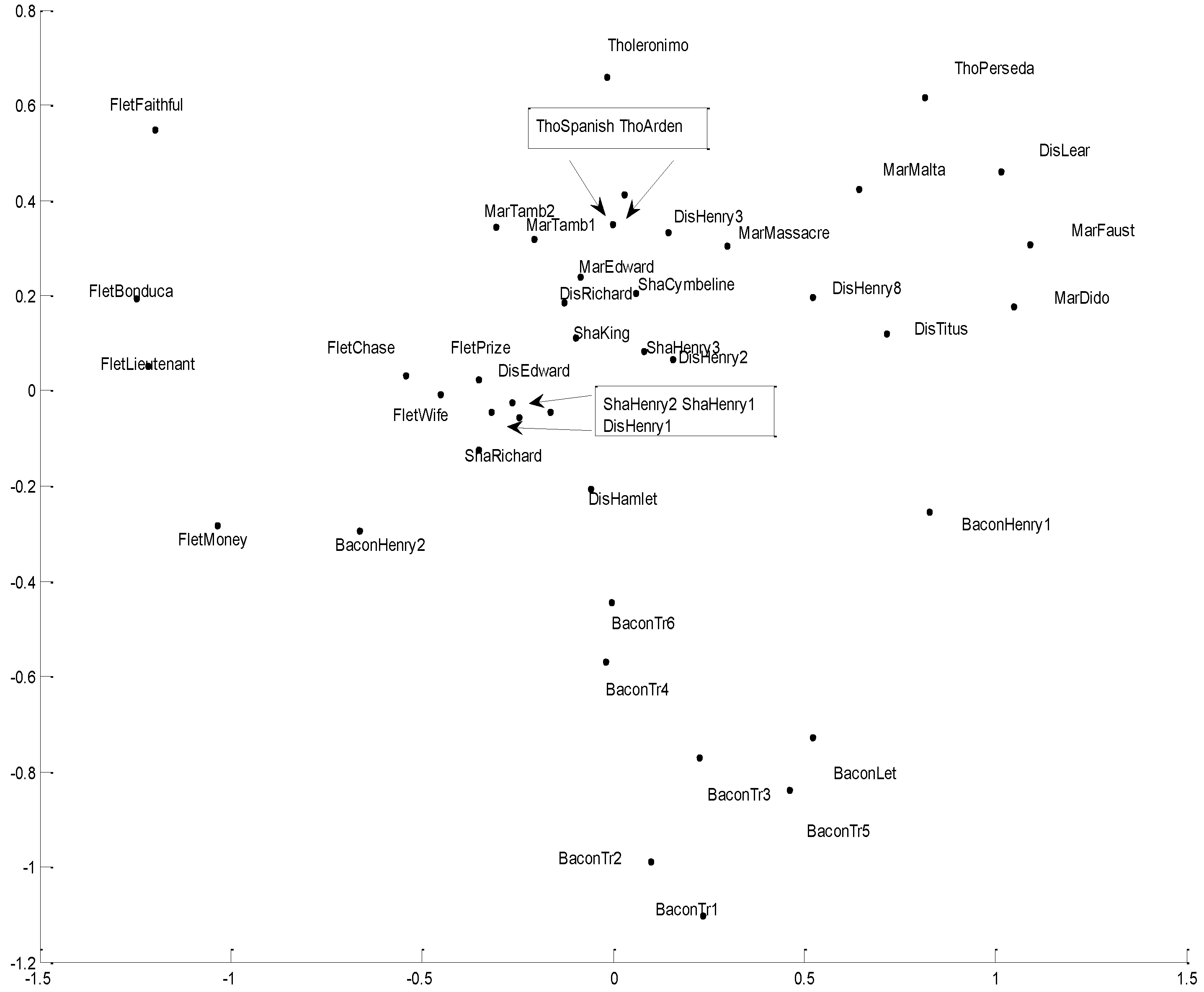

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

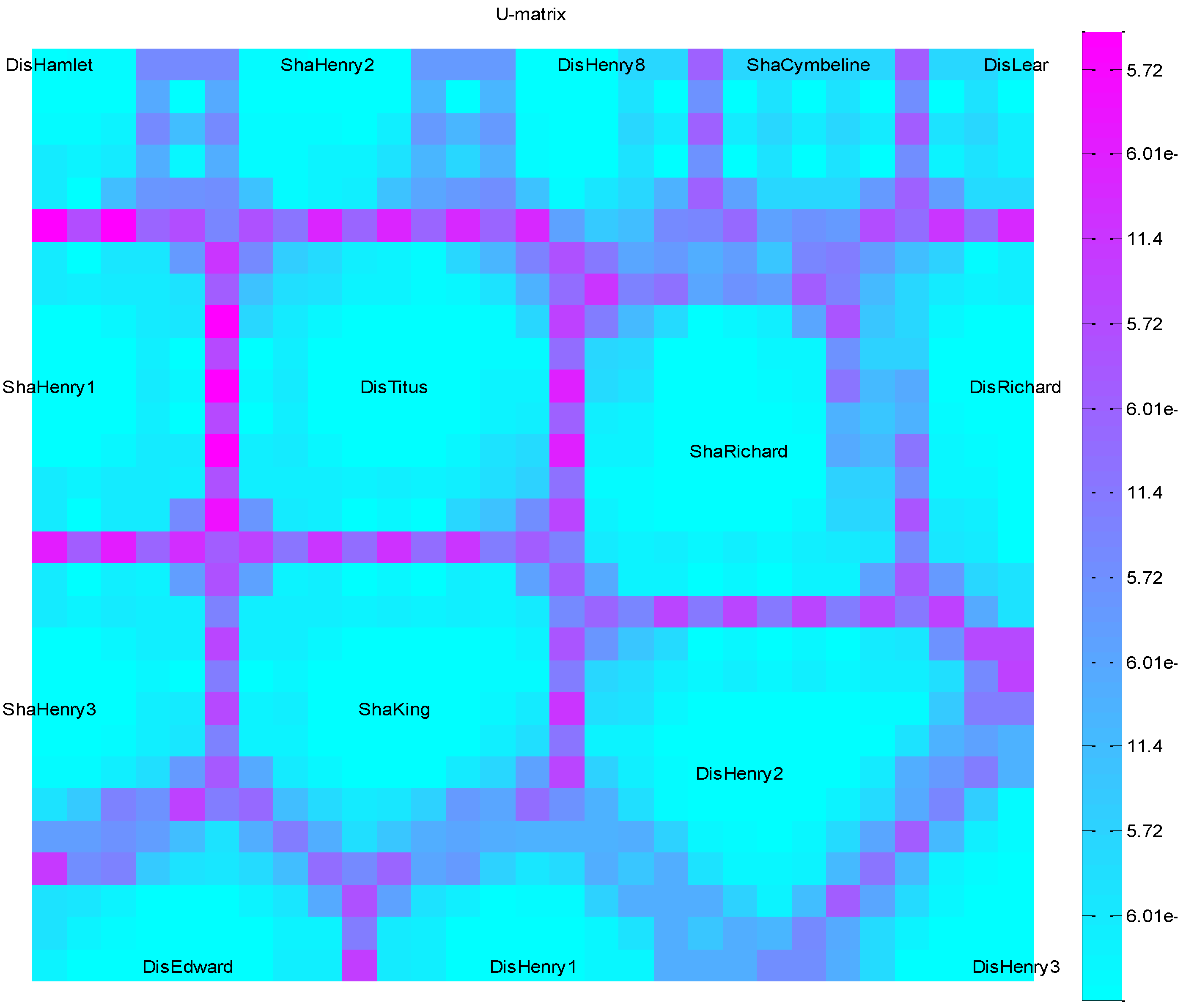

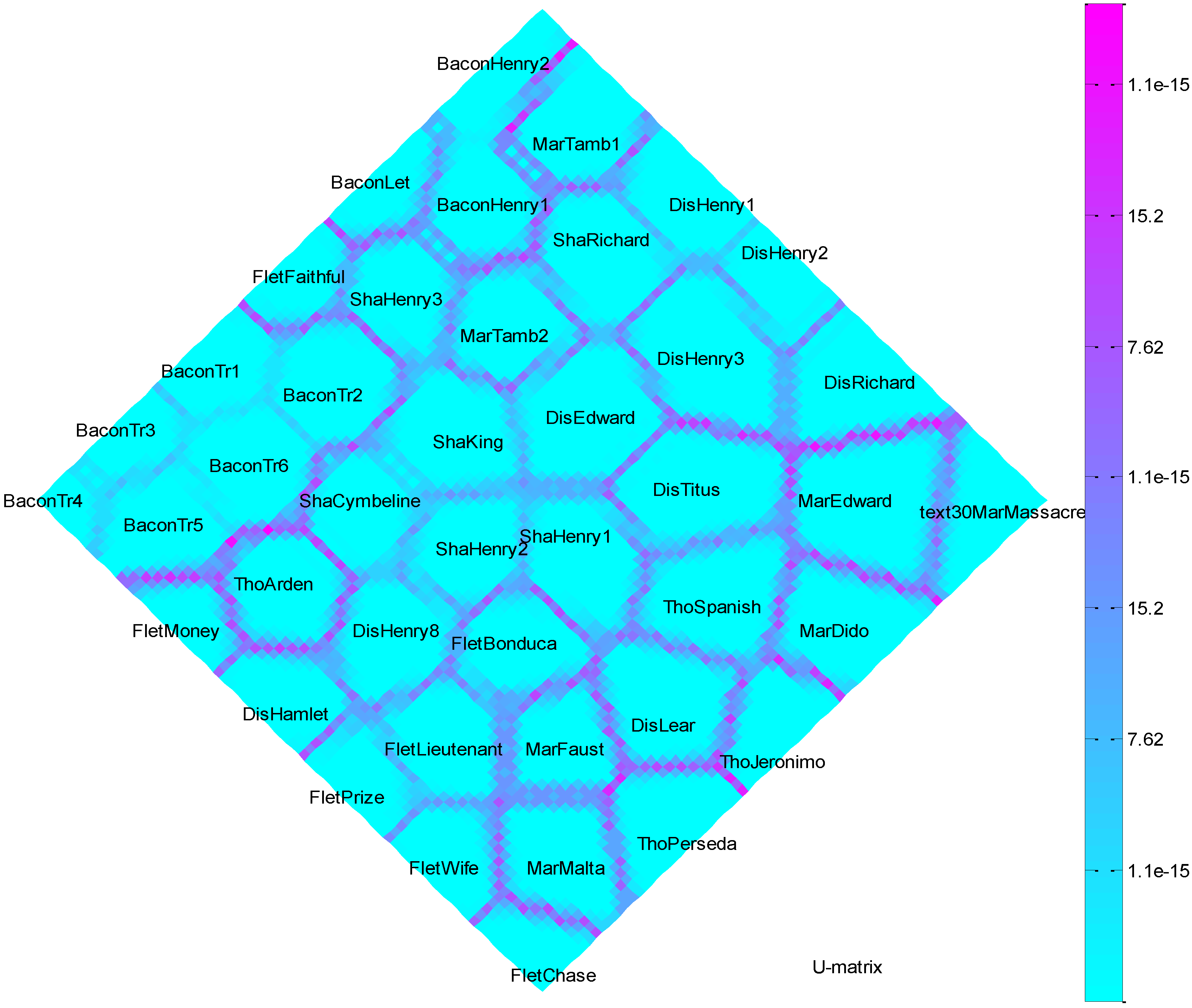

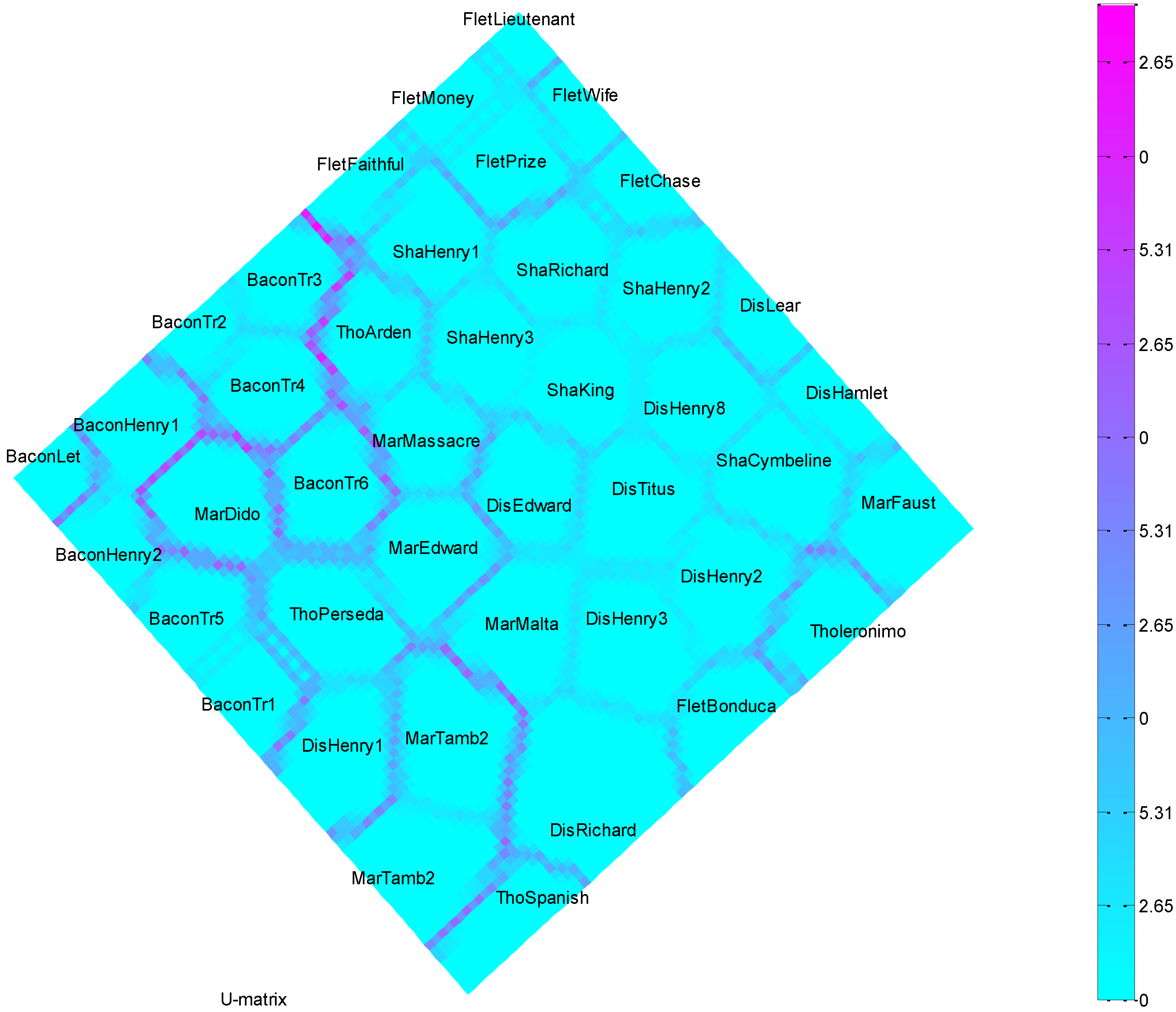

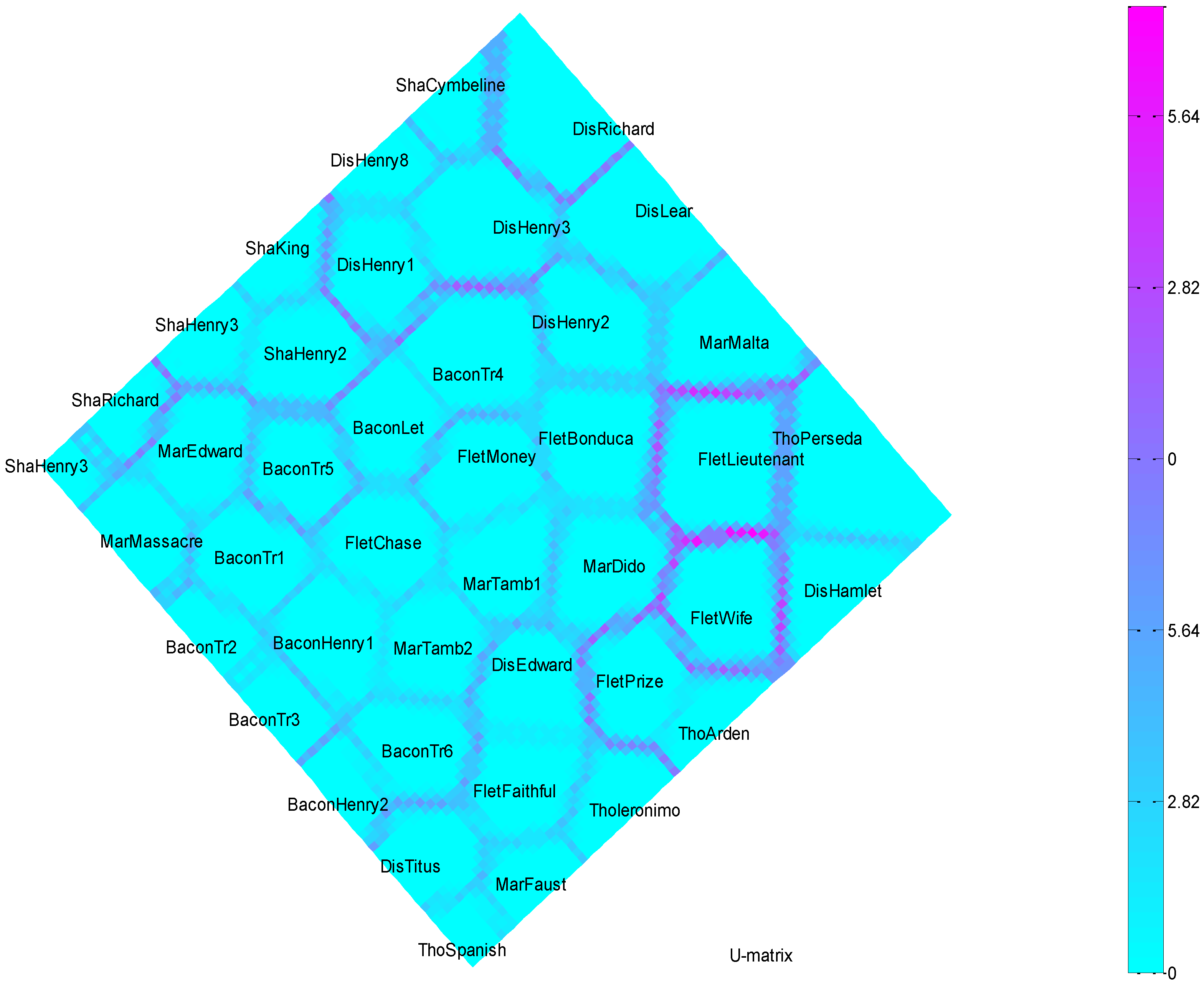

Self-Organizing Map (SOM) U-Matrix

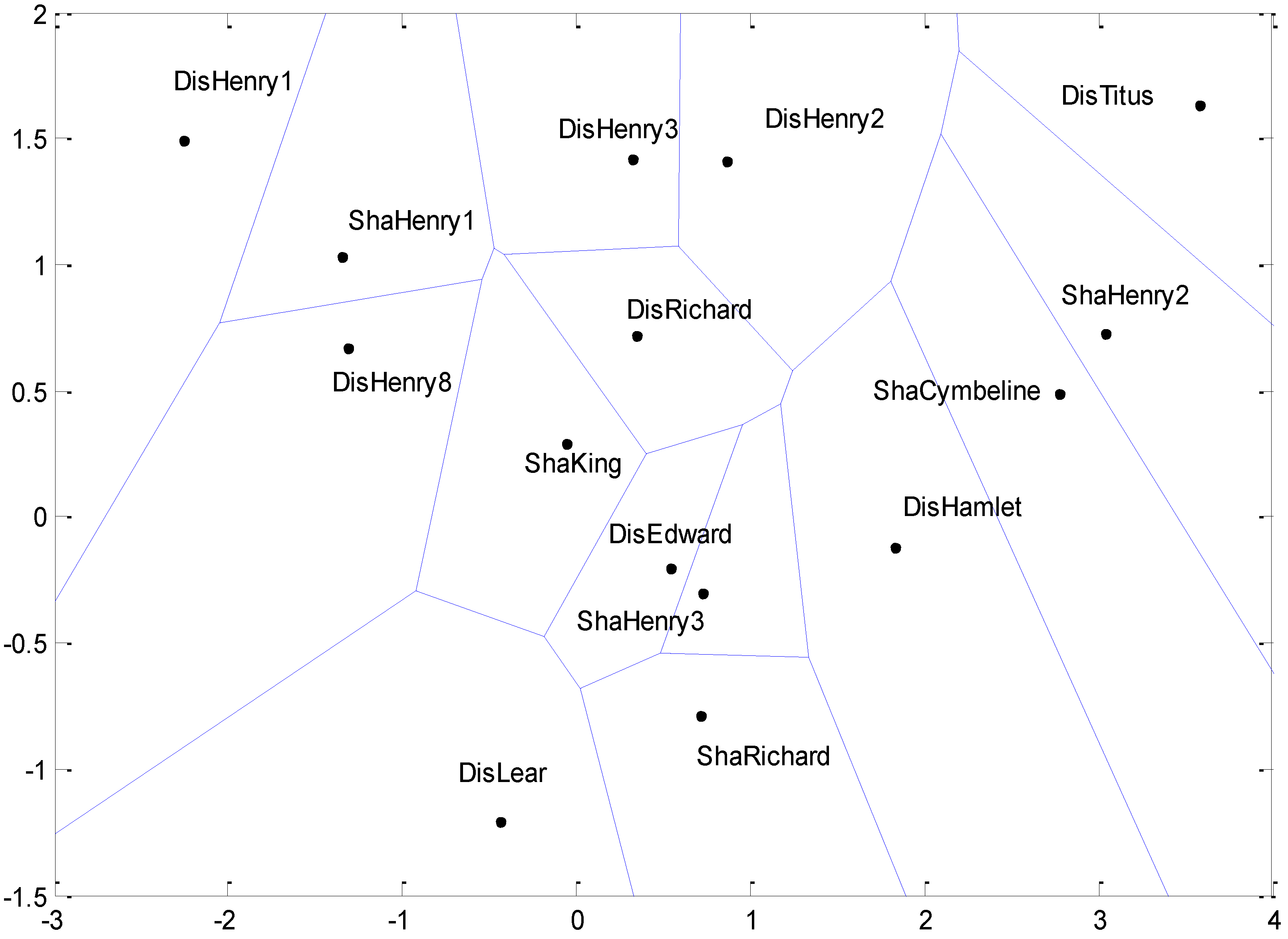

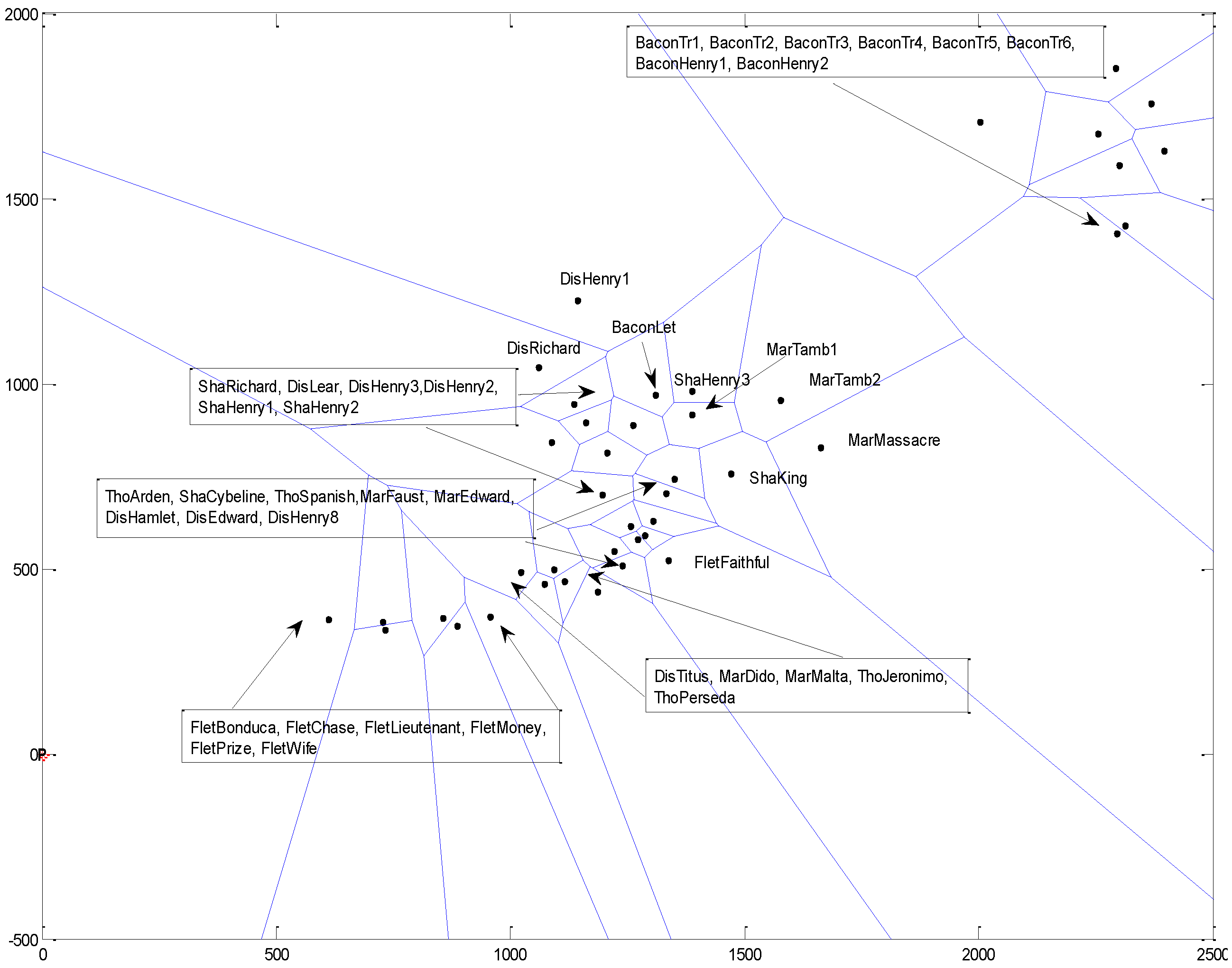

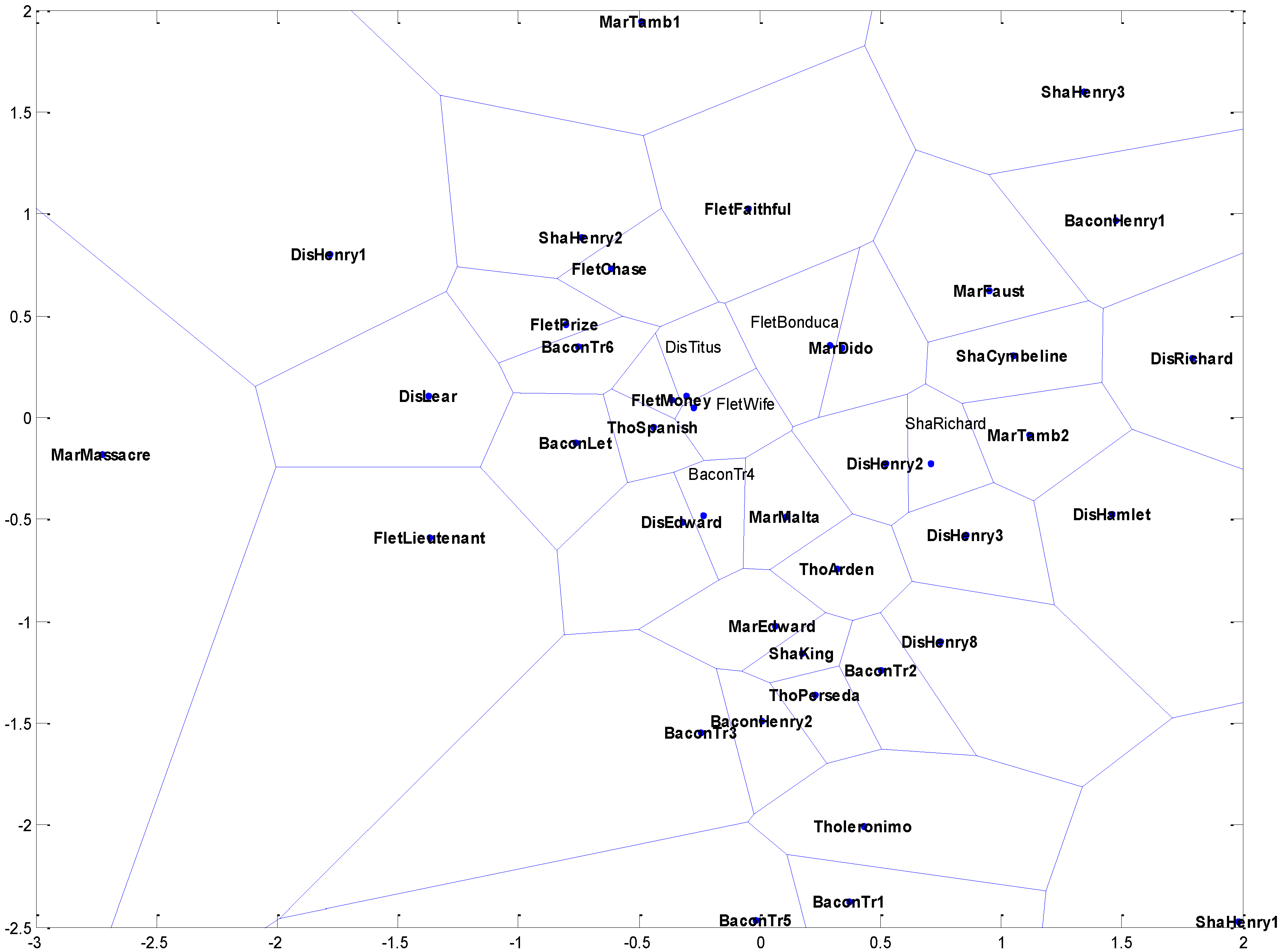

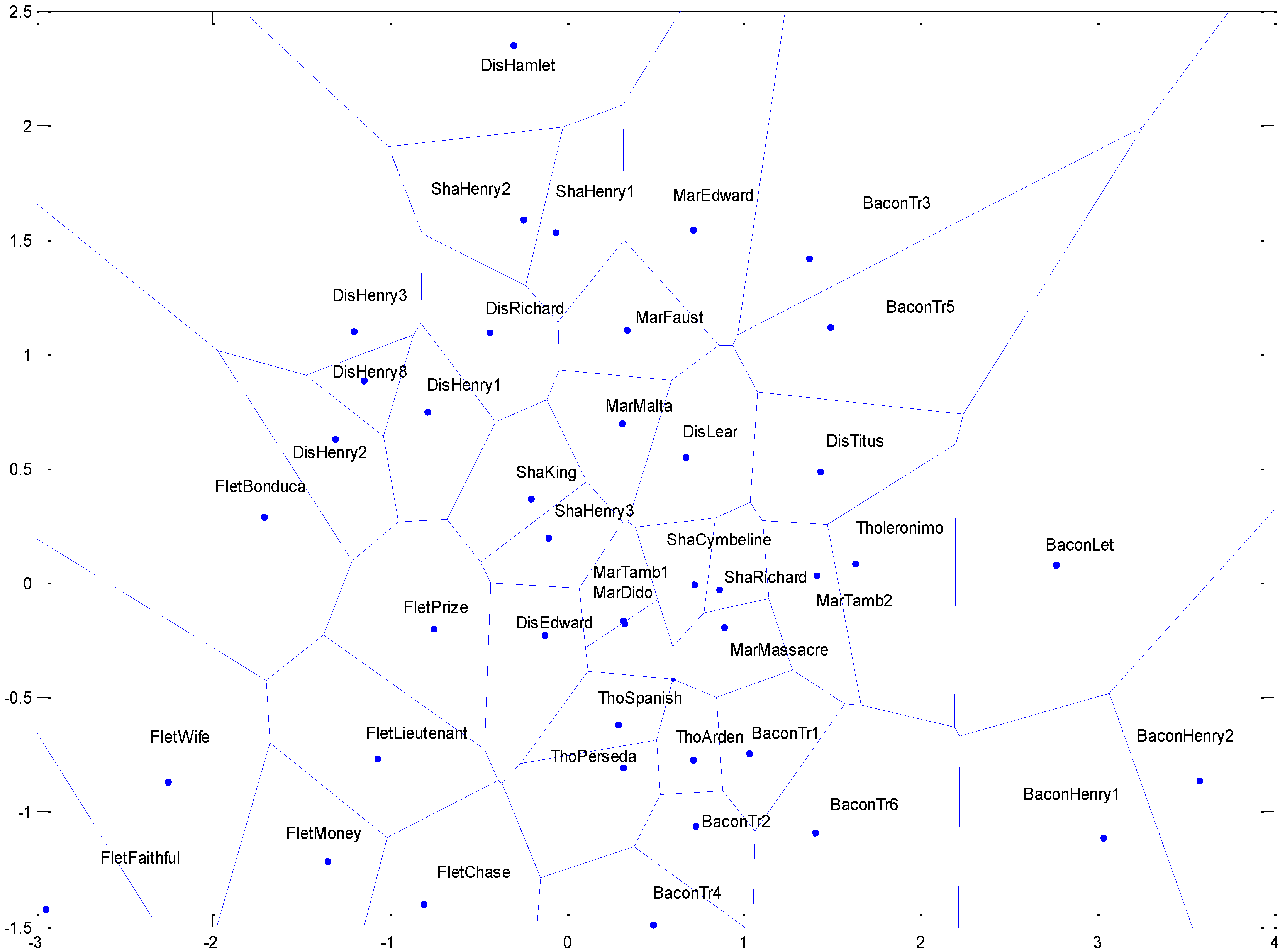

Voronoi Map

4. The Attributional Analyses

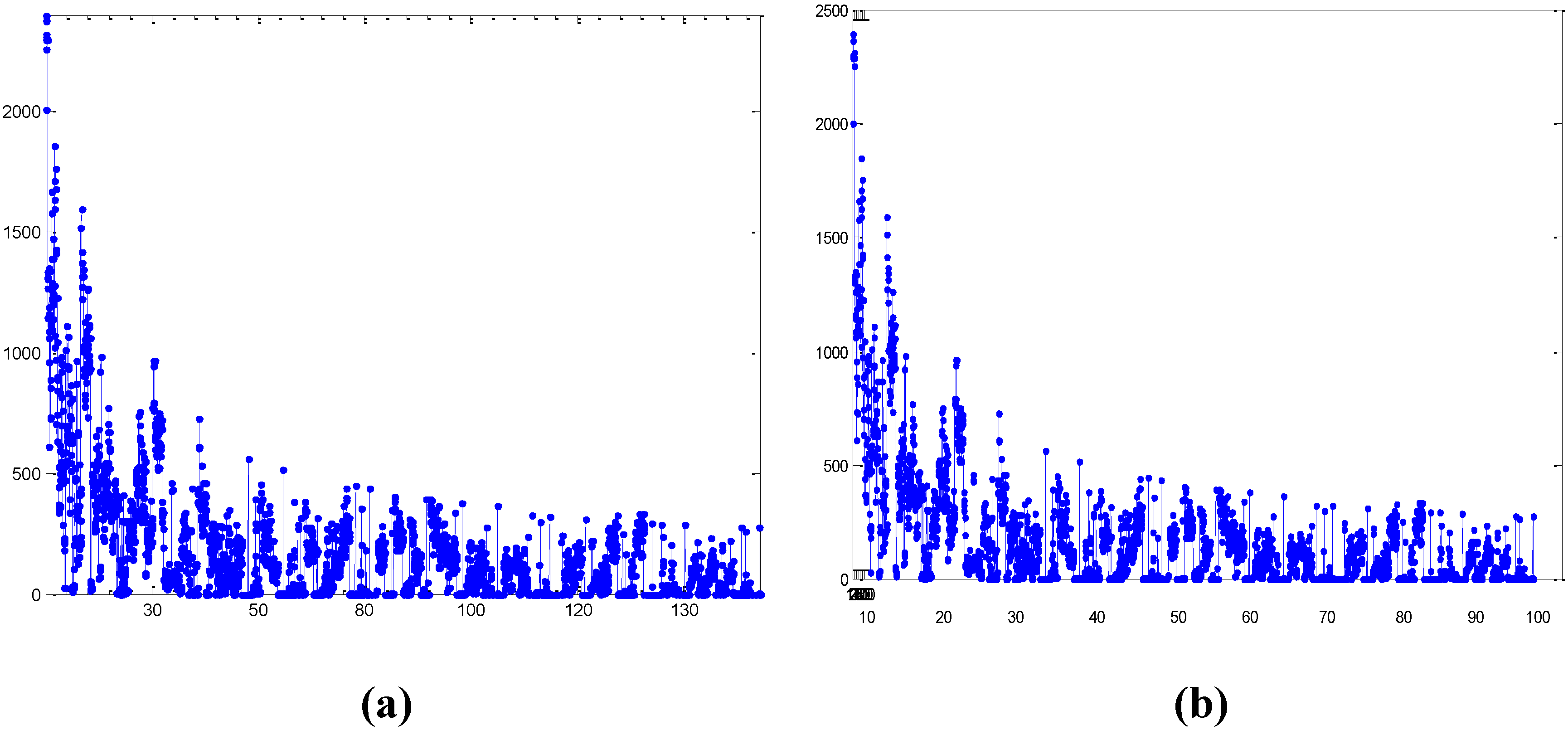

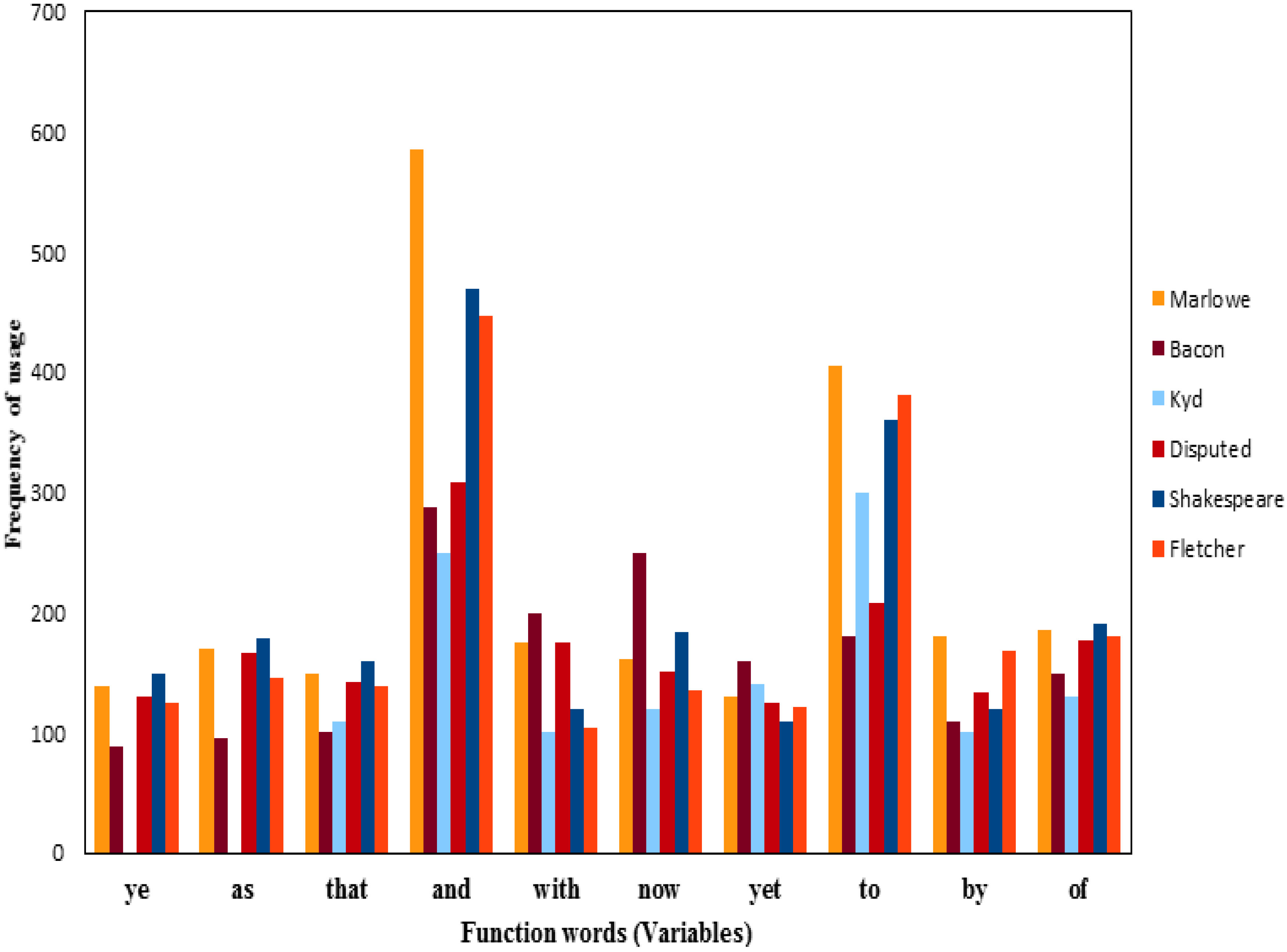

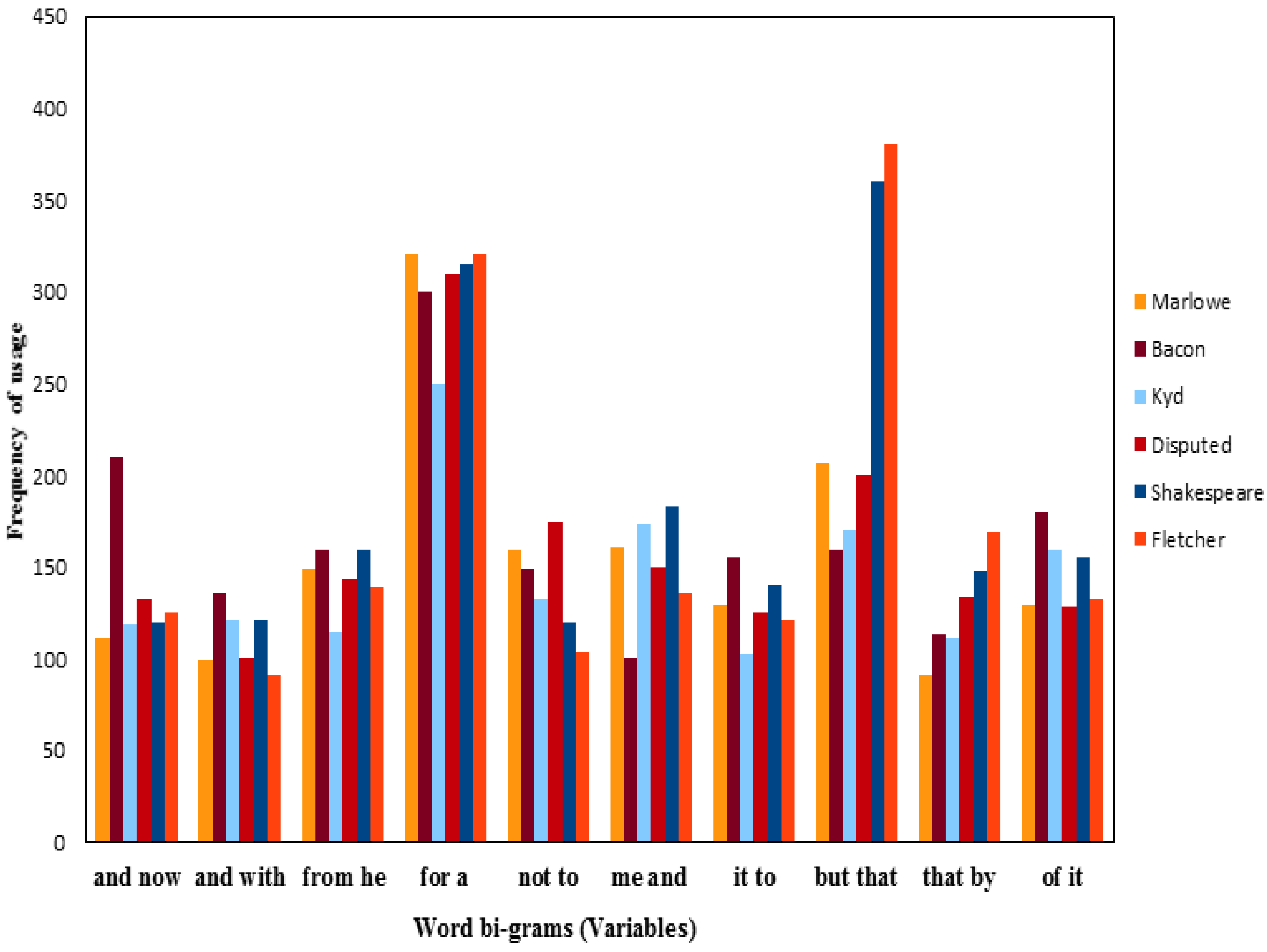

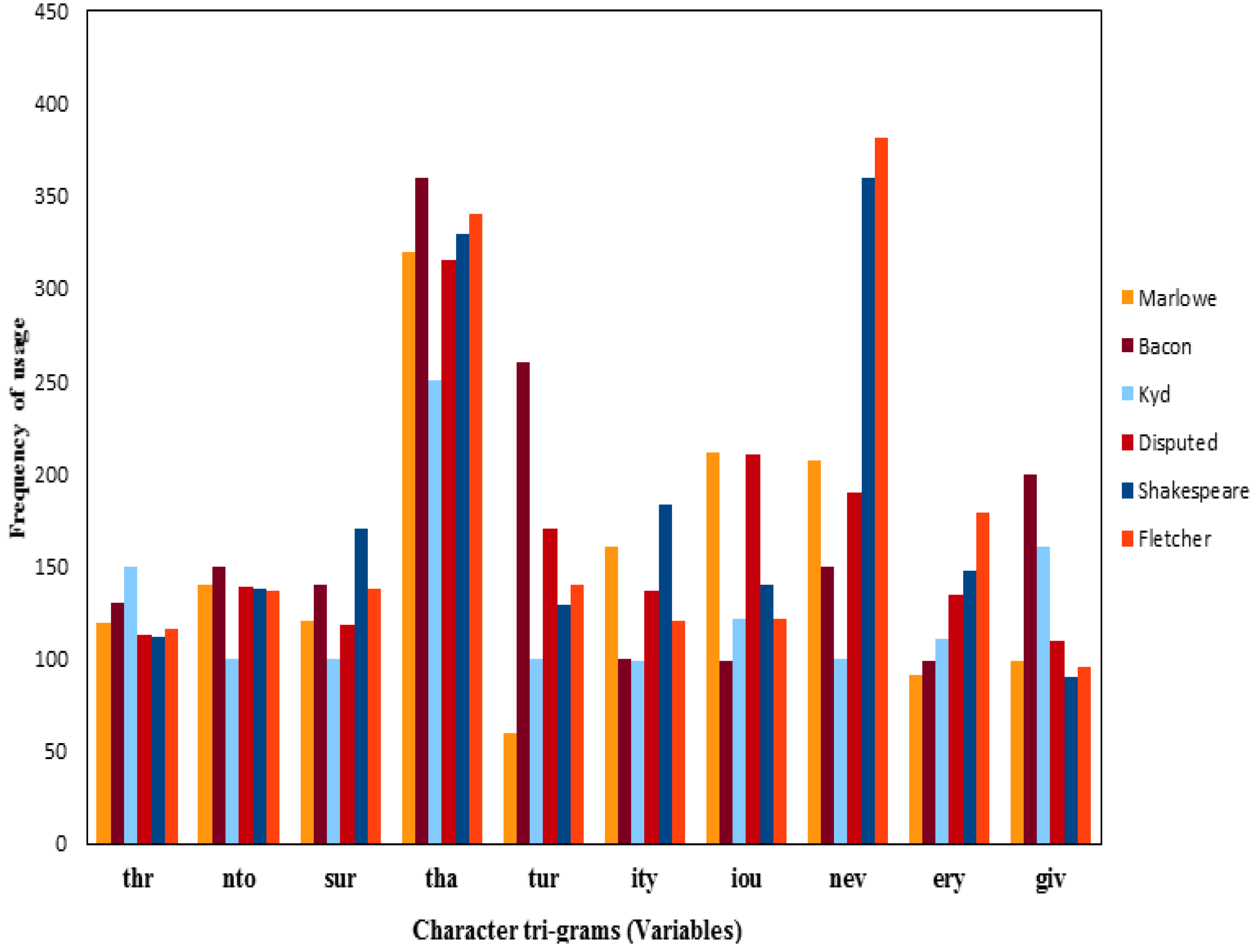

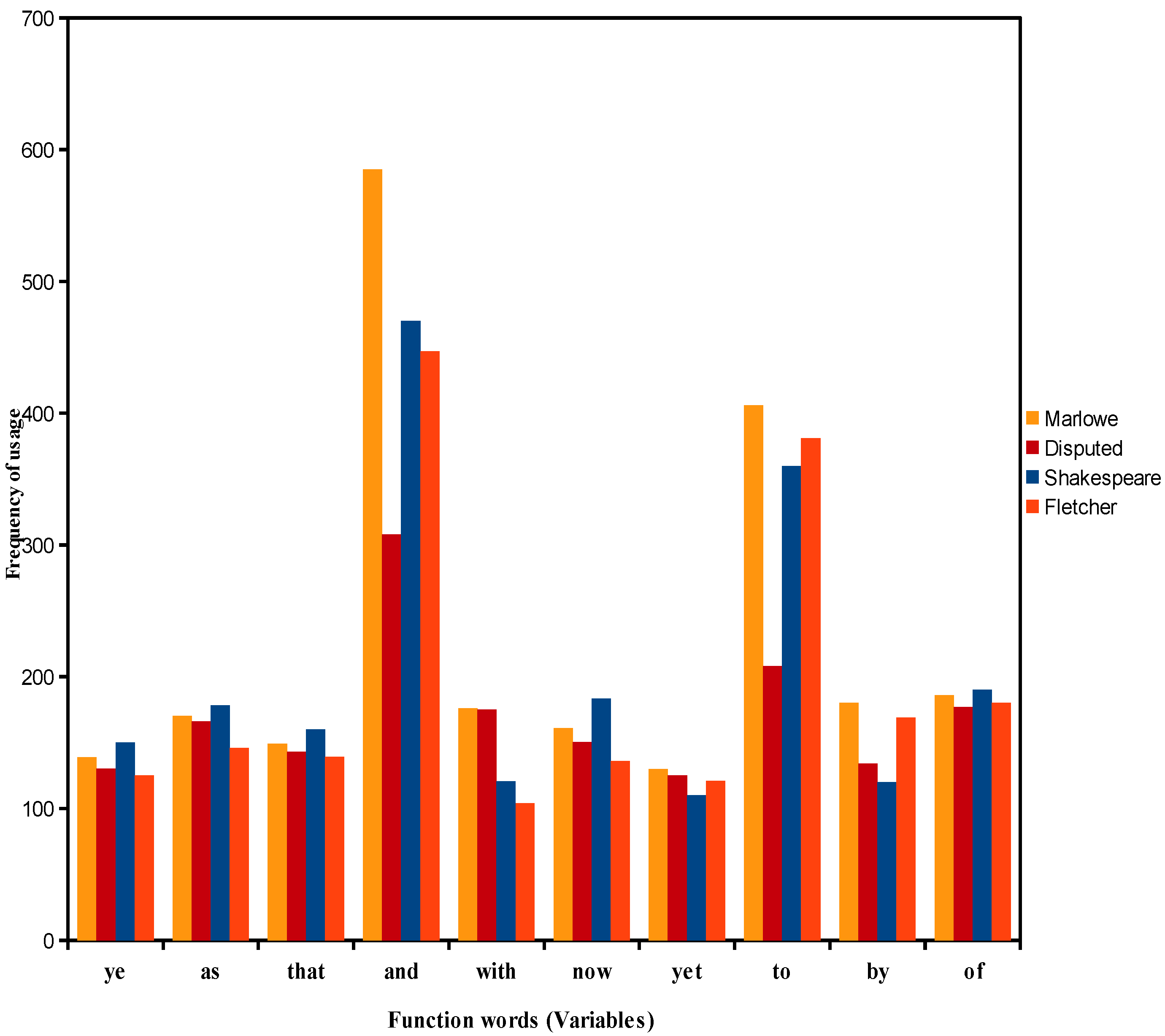

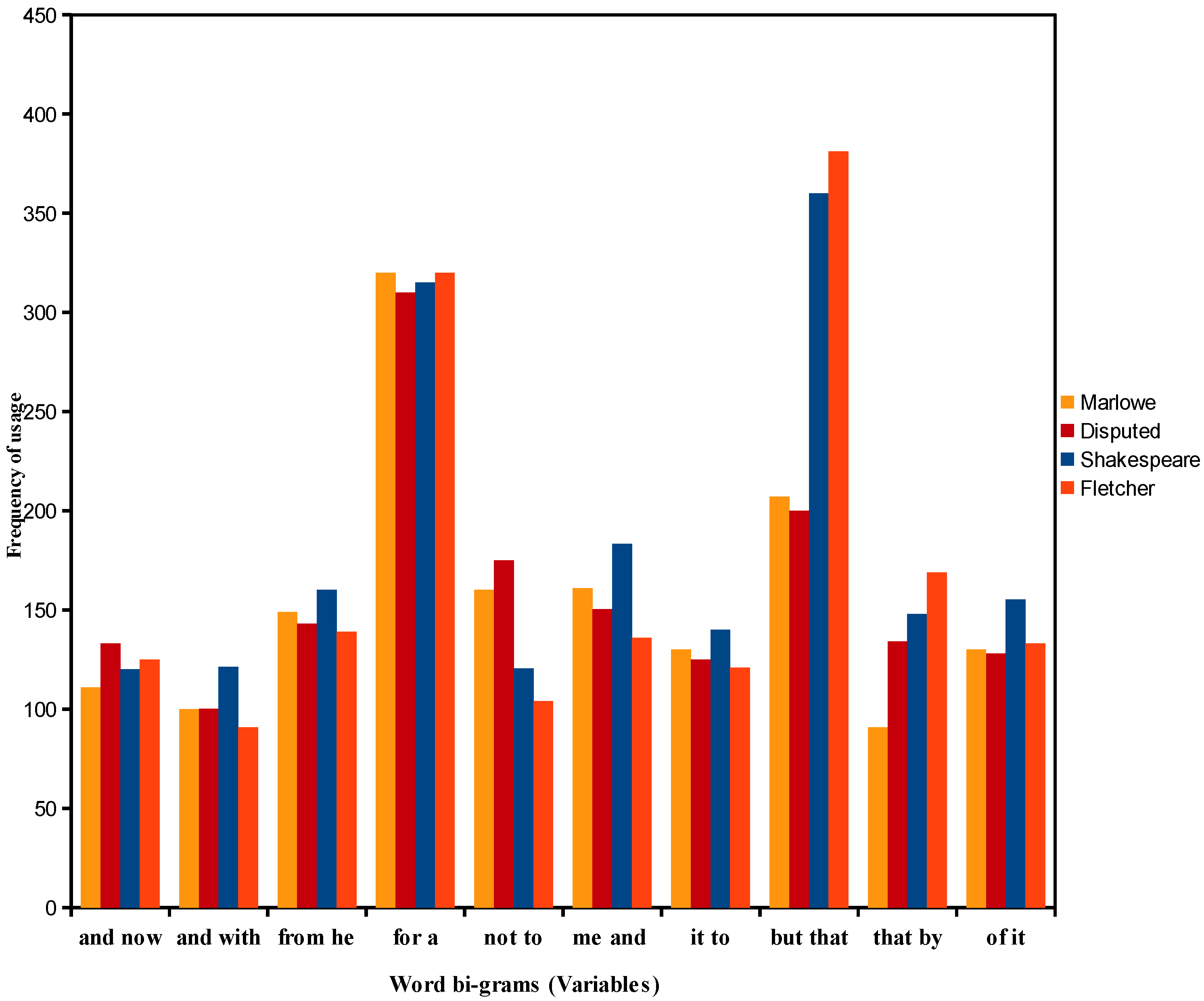

4.1. Analysis of the Frequencies of Usage of Shakespeare’s Function Words, Word Bi-Grams, and Character Triple-Grams

4.2. Analysis of the Frequencies of Usage of Shakespeare and Other Authors’ Function Words

4.3. Analysis of the Frequencies of Usage of Shakespeare and Other Authors’ Word Bi-Grams

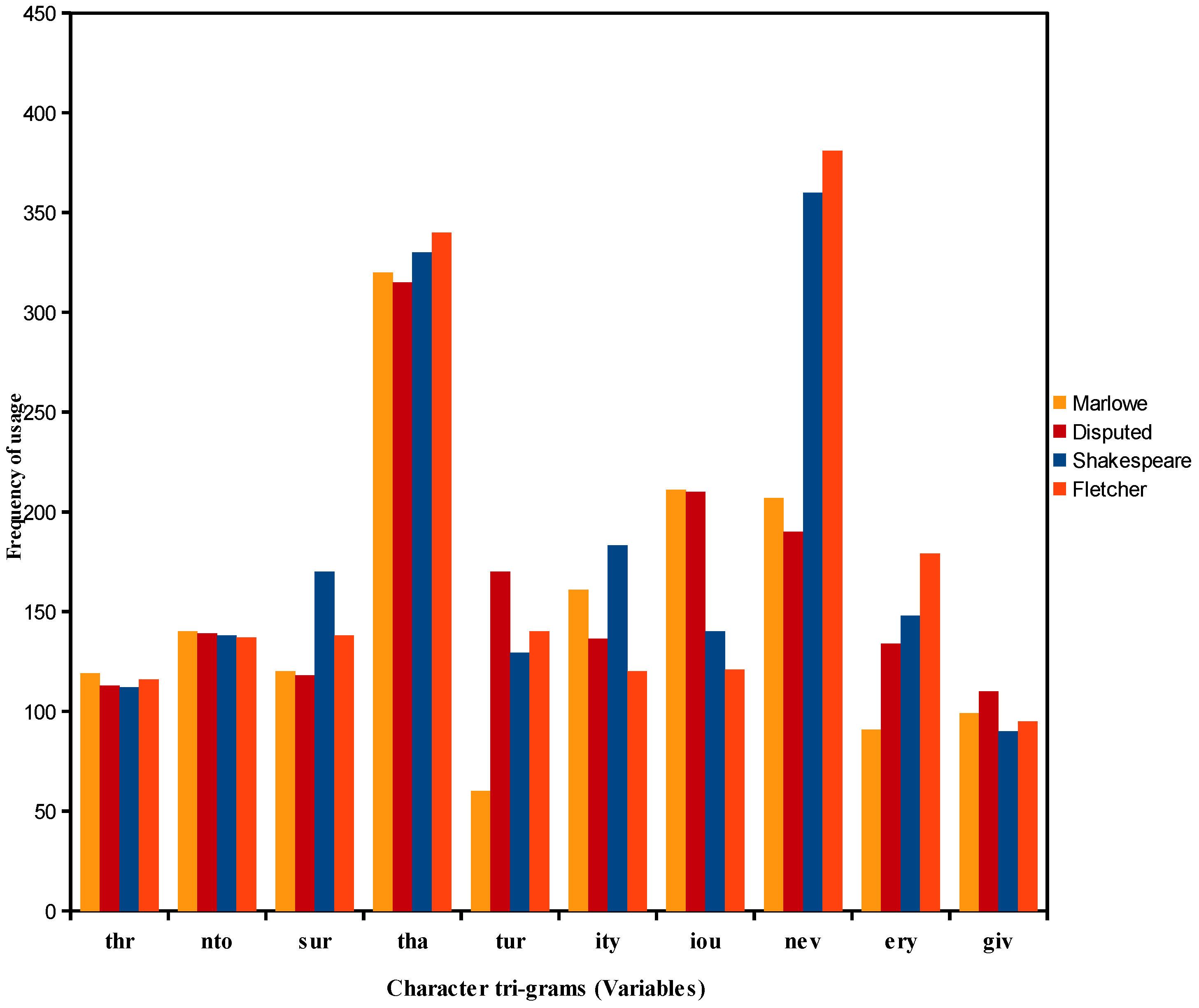

4.4. Analysis of the Frequencies of Usage of Shakespeare and Other Authors’ Character Triple-Grams

4.5. Interpretation

- (1)

- Function words “and” and “to” are most important in determining the dis/similarity relations in the foregoing cluster analyses of DFW.

- (2)

- Word bi-grams “but that” and “that by” are most important in determining the dis/similarity relations in the foregoing cluster analyses of Dbi-gram.

- (3)

- Character tri-grams “tur” and “nev” are most important in determining the dis/similarity relations in the foregoing cluster analyses of Dti-gram.

5. Conclusions and Further Research

- (1)

- The current attributional attempt is by nature exploratory. Cluster analysis is an exploratory tool used to detect and represent graphically non-random structures in the distribution of vectors in an n-dimensional space. The obtained clustering can serve as a basis for hypothesis generation without any attempt to determine whether or not such hypotheses are valid. The hypothesis that can be drawn from this study is thus rather suggestive.

- (2)

- In researching Elizabethan-period literature, the researcher found that Shakespeare is not the only Elizabethan author whose authorship of specific works is controversial. Most Elizabethan plays were published without the playwrights’ names. And this may bring doubt upon the usefulness of the stylistic criteria used here. The implication is that the ongoing dispute over the individual authorship of most Elizabethan plays provides what Craig and Kinney [45] consider “particular difficulties with these plays arise…” and “it may well be more difficult to detect the distinctiveness of individual styles in history plays of this period than elsewhere because the genre itself was just getting established the early 1590s, writers were learning rapidly from each other, and strong influences like Kyd’s, Marlowe’s, and Shakespeare, were felt everywhere”.

- (3)

- Marlowe and Fletcher may have collaborated or helped Shakespeare to write all or some of the disputed plays, but one knows to draw the boundaries between Shakespeare’s style and the styles of his contemporaries or near contemporaries that would greatly influence his dramatic writings during different stages of his career.

- (4)

- Apart from Shakespeare, the study included only four of the authors who have been proposed as alternative authors of the entire Shakespeare canon (Bacon, Marlowe, Fletcher, and Kyd). Yet, the alternative candidate, Edward de Vere, who currently has the most support by Oxfordian scholars, is not among those tested.

- (5)

- The result from this attribution attempt is a plausible result, but it is by far not the only interpretation. It is important not to over interpret this result since it is only based on three textual features, i.e., function words, word-bigrams, and character tri-grams; other stylistic features might give a different result.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harold Bloom. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. London: Riverhead Books, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Margirie Garber. Shakespeare’s Ghost Writers: Literature as Uncanny Causality. New York and London: Methuen, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas Erne. “Shakespeare’s Edward III: An early play restored to the canon.” Archiv fur das Studium der Neueren Sprachen und Literaturen 236 (1999): 425–27. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Proudfoot. The Reign of King Edward the Third (1596) and Shakespeare. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Karl Wentersdorf. “The Date of Edward III.” Shakespeare Quarterly 16 (1965): 227–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott McCrea. The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- David Kathman. “The Question of Authorship.” In Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Edited by Stanley Wells and Lena Cowen Orlin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, pp. 620–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Bate. The Genius of Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gary Taylor. Reinventing Shakespeare: A Cultural History, from the Restoration to the Present. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Warren Hope, and Holston Kim. The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of Authorship Theories, 2nd ed. Jefferson: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alan Nelson. “Stratford Si! Essex No! ” Tennessee Law Review (Tennessee Law Review Association) 72 (2004): 149–69. [Google Scholar]

- Diana Price. Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tom Bethell. “The Case for Oxford (and Reply).” Atlantic Monthly 268 (1991): 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- George L. McMichael, and Edgar M. Glenn. Shakespeare and His Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. Lewis Center: Odyssey Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert Standen. Shakespeare Authorship: A Summary of Evidence, 1st ed. London: Cecil Palmer, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- James Shapiro. Contested Will. Who Wrote Shakespeare? New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Edmondson, and Stanley Wells. Shakespeare beyond Doubt, 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harold Love. Authorship Attribution: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Hamilton Law. The English Familiar Essay in the Early Nineteenth Century. New York: Russell & Russell, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Albert Yang, Chung-Kang Peng, and Ary L. Goldberger. “The Marlowe-Shakespeare Authorship Debate: Approaching an Old Problem with New Methods.” Available online: http://www.psynetresearch.org/uploads/7/5/8/1/7581337/hoffman_essay.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2015).

- Stanley Wells. “Authorship Debate.” The Shakespeare Authorship Coalition. 2015. Available online: https://doubtaboutwill.org/letters_to_sbt_and_rsc/3 (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Moshe Koppel, Jonathan Schler, and Shlomo Argamon. “Computational methods in authorship attribution.” Journal of American Society for Information and Technology 60 (2009): 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathios Stamatatos. “Author identification: Using text sampling to handle the class imbalance problem.” Information Processing and Management 44 (2008): 790–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick Juola. “Authorship attribution.” Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval 1 (2006): 233–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandeis Library & Technology Services. “Digital Humanities: From 1851? ” Available online: https://blogs.brandeis.edu/lts/2013/05/17/digital-humanities-from-1851/ (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Wincenty Lutosławski. Principes de stylométrie. Paris: Ernets Leroux, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- David Holmes. “Authorship attribution.” Computers and the Humanities 28 (1994): 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack Grieve. “Quantitative authorship attribution: A history and an evaluation of techniques.” Master’ Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jack Grieve. “Quantitative authorship attribution: An evaluation of techniques.” Literary and linguistic Computing 22 (2007): 251–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony McEnery, and Michael Oakes. “Authorship identification and computational Stylometry.” In Handbook of Natural Language Processing. Edited by Robert Dale, Harold Somers and Hermann Moisl. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- David Holmes. “The Evolution of Stylometry in humanities scholarship.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 13 (1998): 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David Holmes. “A stylometric analysis of Mormon scripture and related texts.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A (Statistics in Society) 155 (1992): 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann Moisl. Cluster Analysis for Corpus Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brain Everitt, Sabine Landau, and Morven Leese. Cluster Analysis, 4th ed. London: Taylor & Francis, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- David Holmes. “Vocabulary richness and the prophetic voice.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 6 (1991): 259–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Burrows. “Computers and the Study of Literature.” In Computers and Written Text. Edited by Christopher Butler. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992, pp. 167–204. [Google Scholar]

- David Holmes, and Robert Forsyth. “The Federalist Revisited: New directions in Authorship Attribution.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 10 (1995): 111–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harald Baayen, Hans Van Halteren, and Fiona Tweedie. “Outside the cave of shadows: Using syntactic annotation to enhance authorship attribution.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 11 (1996): 121–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Merriam. “Marlowe’s hand in Edward III.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 8 (1996): 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Corwin Mendenhall. “The characteristic curves of composition.” Science 11 (1887): 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas Corwin Mendenhall. “A mechanical solution to a literary problem.” Popular Science 9 (1901): 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Eilot Slater. The Problem of the Reign of King Edward III: A Statistical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Neal Fox. “Statistical Stylometrics and the Marlowe-Shakespeare Authorship Debate.” 2012. Available online: http://cs.brown.edu/research/pubs/theses/masters/2012/ehmoda.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2015).

- Robert Matthews, and Thomas Merriam. “Neural computation in stylometry: An application to the works of Shakespeare and Fletcher.” Literary and Linguistic Computing 8 (1993): 203–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugh Craig, and Arthur Kinney. Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- “The Shakespeare Authorship Page.” Available online: http://shakespeareauthorship.com/whyn-ot.html (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Louise McConnell. Dictionary of Shakespeare. Teddington: Peter Collin Publishing Ltd., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- John Jowett, William MontGomery, Gary Taylor, and Stanley Wells. The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works, 2nd ed. Edited by Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Romany, and Robert Lindsey. Christopher Marlowe: The Complete Plays. Belfast: Penguin Books Ltd., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- David Bevington, and Eric Rasmussen. Doctor Faustus and Other Plays Tamburlaine, Parts I and II; Doctor Faustus, A- and B-Texts; The Jew of Malta; Edward II. Christopher Marlowe. Oxford: Oxford World Classics, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur Henry Bullen. The Works of Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, Vols. II & III. Edited by George Bell and Arthur Henry Bullen. Charleston: Forgotten Books, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick Boas. The Works of Thomas Kyd. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Maciej Eder. “Style-Markers in Authorship Attribution A Cross-Language Study of the Authorial Fingerprint.” Studies in Polish Linguistics 6 (2011): 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Anderberg. Cluster Analysis for Applications. London: Academic Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ragharendra Gadagkar. “Division of Labor and Organization of Work in the Primitively Eusocial Wasp Ropalidia Marginata.” Proceedings of the Indian National Science Academy-Part B: Biological Sciences 67 (2001): 397–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan J. DeGhett. “Hierarchical cluster analysis.” In Quantitative Ethology. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1978, pp. 115–44. [Google Scholar]

- Oscar Miguel Rivera-Borroto, Mónica Rabassa-Gutiérrez, Ricardo del Corazón Grau-Ábalo, Yovani Marrero-Ponce, and José Manuel García-de la Vega. “Dunn’s index for cluster tendency assessment of pharmacological data sets.” Canadian Journal Physiology Pharmacology 90 (2012): 425–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil K. Jain, and Richard C. Dubes. Algorithms for Clustering Data. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Teuvo Kohonen. Self-Organizing Maps, 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljumily, R. Hierarchical and Non-Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Clustering Methods to “Shakespeare Authorship Question”. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 758-799. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030758

Aljumily R. Hierarchical and Non-Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Clustering Methods to “Shakespeare Authorship Question”. Social Sciences. 2015; 4(3):758-799. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030758

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljumily, Refat. 2015. "Hierarchical and Non-Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Clustering Methods to “Shakespeare Authorship Question”" Social Sciences 4, no. 3: 758-799. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030758

APA StyleAljumily, R. (2015). Hierarchical and Non-Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Clustering Methods to “Shakespeare Authorship Question”. Social Sciences, 4(3), 758-799. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4030758